5 minute read

A Moment in Time

After working a life-long career as a professional photographer in medical imaging, retirement has allowed long-serving BIPP member Richard Hildred ABIPP to fully explore his personal photography interests. The recent exploration of his creative passion resulted in displaying his images in The North Sea Observatory Gallery this August, in an exhibition entitled A Moment in Time.

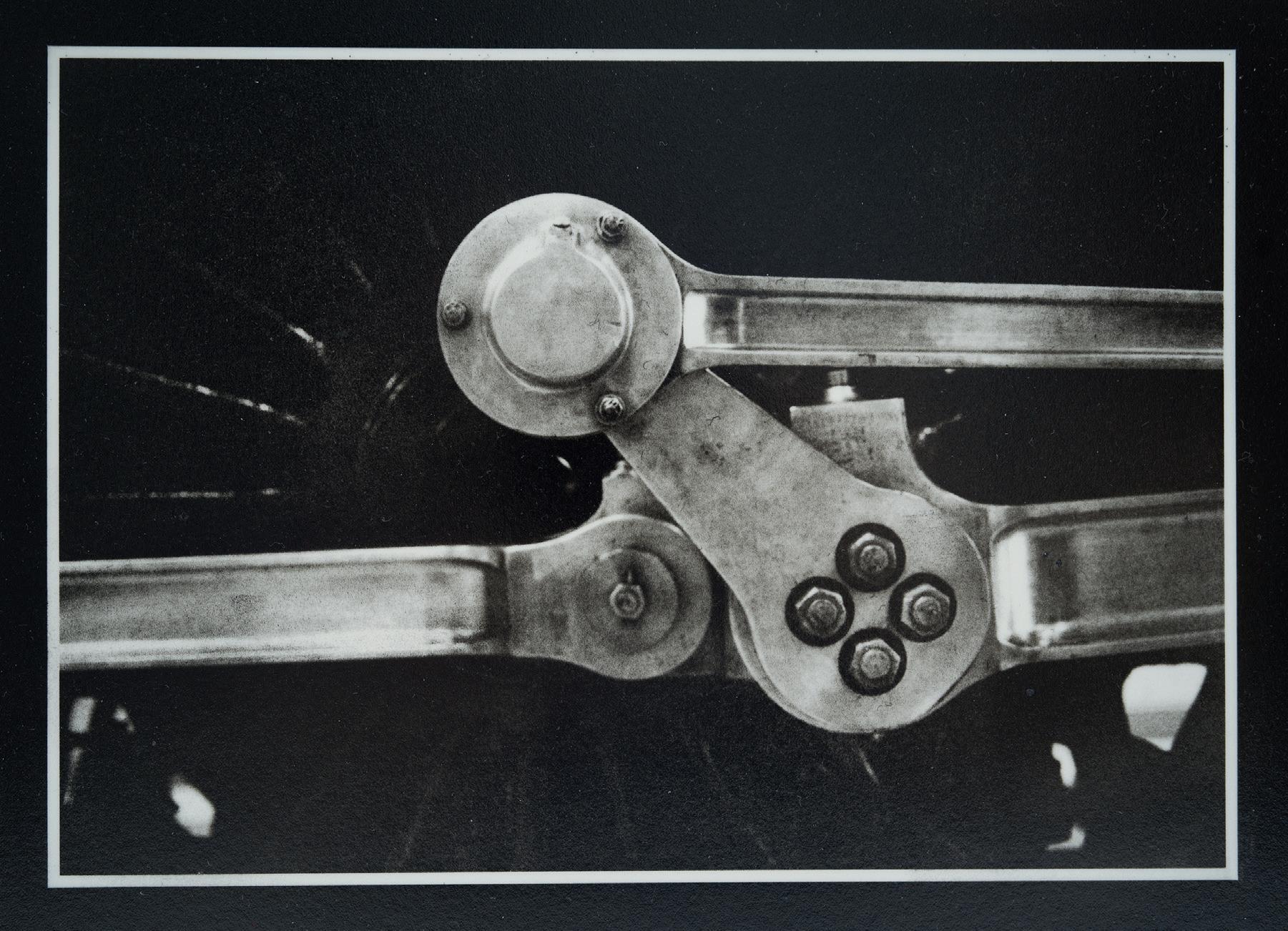

Richard states, “In these days of high-resolution and instant digital imaging, my favourite medium is still black and white, but more importantly, it must be of the highest quality to retain the security of archival permanence. Ironically, this is not the product of most modern technology and mediums, as their images are focused on speed of access and will more than likely fade rapidly in time.”

After researching several older styles of “alternative imaging” techniques, he came across “oil printing”, an early gelatin photographic process described first by a French chemist, photographer and civil engineer Louis Poitevin in 1855. However, it was not seriously practised until 1904 by English photographer G.E.H. Rawlins.

It was the precursor to the classical ‘Bromoil Pigment Process’ and produces some of the highest quality fine art prints this historic technique allows. The carefully inked images are printed with Lithographic Ink onto acid-free archival quality watercolour paper, giving deep rich blacks, pure whites and many subtle tones in-between.

Richard says, “Oil Printing is considered one of the true photographic processes that allows the printing of a conventional photographic ‘negative’ as a positive image onto high-quality sensitized art paper.”

However, what differentiates it from modern-day classical photographic printing is that the paper - having been previously coated with a thick gelatin solution - is sensitized to light by applying a solution of potassium dichromate onto its surface and not the more traditional or conventional silver nitrate solution. The negatives used are “contact printed” under UV light onto the art paper and are always the same size as the resulting picture.

“After exposing the negative to ultraviolet light somewhat magically, this amazingly simple combination of chemistry and material enables the gelatin to be hardened in the dense areas of the image and softened in the lighter areas.”, explains Richard.

“It then allows the harder dense areas to accept thick, greasy printers’ lithography ink, and the lighter areas to repel the ink in proportion to the density and tone of the image. The end result being a unique individual image of amazing quality and great archival permanence. The ink can be applied in many ways - either by brush, sponge or brayer type roller. My preferred method is using a semismooth 2-inch roller and very fine sponges to apply the ink, or a variety of sizes and shapes of dry brushes to remove any excess ink.”

Many of the prints featured in the exhibition are reanimated images from shots Richard has captured throughout a lifetime as a photographer, “Fortunately, I still have quite a comprehensive archive of images going back to the 1960s. Sadly my very early days of photography, prior to this, were on Kodak Brownie equipment and are still in storage, and probably not particularly useable exhibition quality!” “Since then, my personal subjects have covered

all aspects of life from people to landscapes to buildings, animals, boats, planes, trains, etc. The great experimentation I experienced while studying photography at college in the 1970s was of great significance. Retirement is enabling me to catalogue and organize this mass of image data for easy access. However, in the meantime, I can randomly enjoy selecting images that are my personal favourites and ones that I believe will work well in my new medium of oil printing.”

“Given the technique is generally regarded as a ‘bygone process’, I take the view that my images should ideally be almost timeless in consideration, meaning the pictures should be almost undatable.”

“If I was asked what is my favourite type of subject in photography? I would have to say I enjoy texture, geometry, perspective and the subtle differences between light and dark! Given this gives me almost carte-blanche access to a myriad of subjects, then it will almost certainly keep me well occupied for many more years to come!”

AIMING SMALL AT THE DEFENCE SCHOOL OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Located at RAF Cosford since 1965, the DSOP primarily trains tri-service personnel to become career Defence Photographers, taking them from no experience to a high level of expertise with the skills and knowledge to apply their trade within the military environment.

Having learnt the basics in module one, trainees now move on to far more technical and challenging aspects of photography.

Today trainer Mr Paul Smith introduced them to macro photography, he says: “We give them the theory, the basic understanding of how it works and what we expect, then send them off to experiment, utilising many of the skills they have already learnt.”

Tim Robinson, Head of Professional Training, said: “The training is delivered in two modules - the underpinning fundamentals are taught in module one, and module two turns those fundamentals into specific practical applications that makes them a military photographer.”

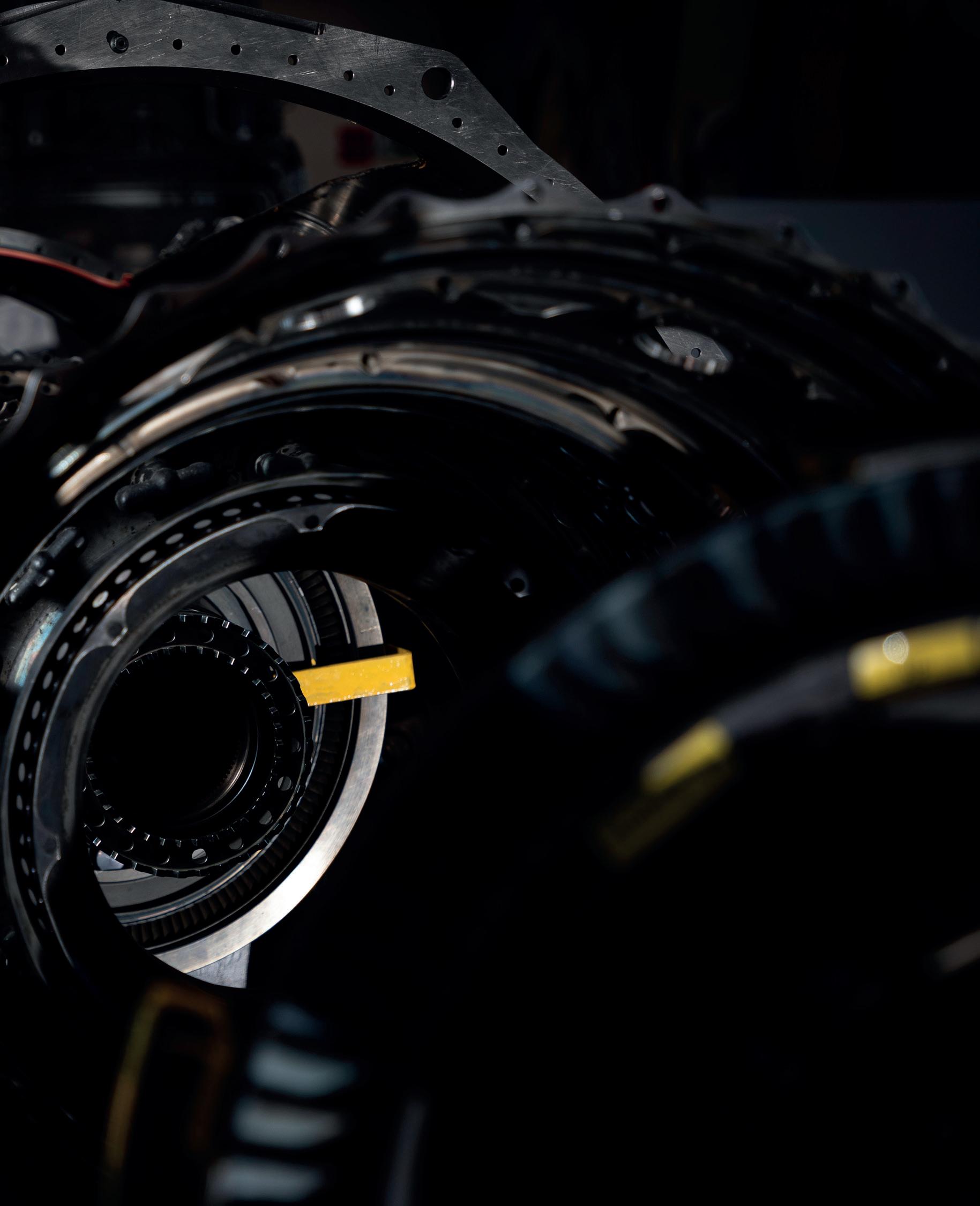

However, the school also receives trainees from across Defence, civil service, police and other government agencies delivering bespoke training tailored to their operational needs. Trainees Cpl Terry and AC Mayall, along with other members of their course, are in the middle of the second module focussing on developing the knowledge and skills taught in module one, putting those skills into realistic scenarios they will experience during their careers.

Currently, the trainees are learning the process of technical photography “In-Situ”. Whether this is on Aircraft, Tanks or Ships, it is a vital part of training for all Defence Photographers. The imagery they produce will be used in engineering technical reports or could be used as evidence for Unit enquires. Therefore the image must be technically correct; there is no room for artistic interpretation! When asked how she was finding the course, AC Mayall said: “There has been a lot to learn, seeing as I knew nothing about photography four and a half months ago, but I’m getting more confident by the day, and I’m looking forward to what’s to come.”