15 minute read

Bits, Bytes & Banding

Bits, Bytes & Banding: Which File Format Is Best?

Ever wondered which is the best file format to use for images and why? Well, I promise that is an entirely unanswerable question! However, always in the pursuit of those pesky details, let’s take a journey through file types, image compression, bit-depth and why you would choose anything other than JPGs.

The Basics - Bits, Bytes And Nibbles!

Firstly, despite the fact it is the analogue world we capture, digital images are stored as a series of 0’s and 1’s - called bits. These ‘bits’ are grouped into ‘bytes’, with each byte having eight bits. So using 8 bits, you can represent any positive number between 0 and 255 (i.e. 256 levels.)

Incidentally, if you thought the boffins who originally designed computers were humourless geeks, think again: a group of 4 bits is called a nibble. I kid you not.

Why is this important?

Well, the bit-depth (I have no idea why we use the word ‘depth’) describes how much detail you can store in your image. For example, 8, 12, 14, 16, or even 32 bits per channel are the most common bit depths, and it defines how many levels of brightness you can store for each pixel in its red, green and blue channels.

Diving The Depths

8-bits per channel allows 256 levels of luminance for each of the red, green and blue channels. So if we multiply this for the three channels, we get 256x256x256 or 16.7 million possible colours at each pixel.

Image 1 - the number of bits per channel defines the tonal range you can capture

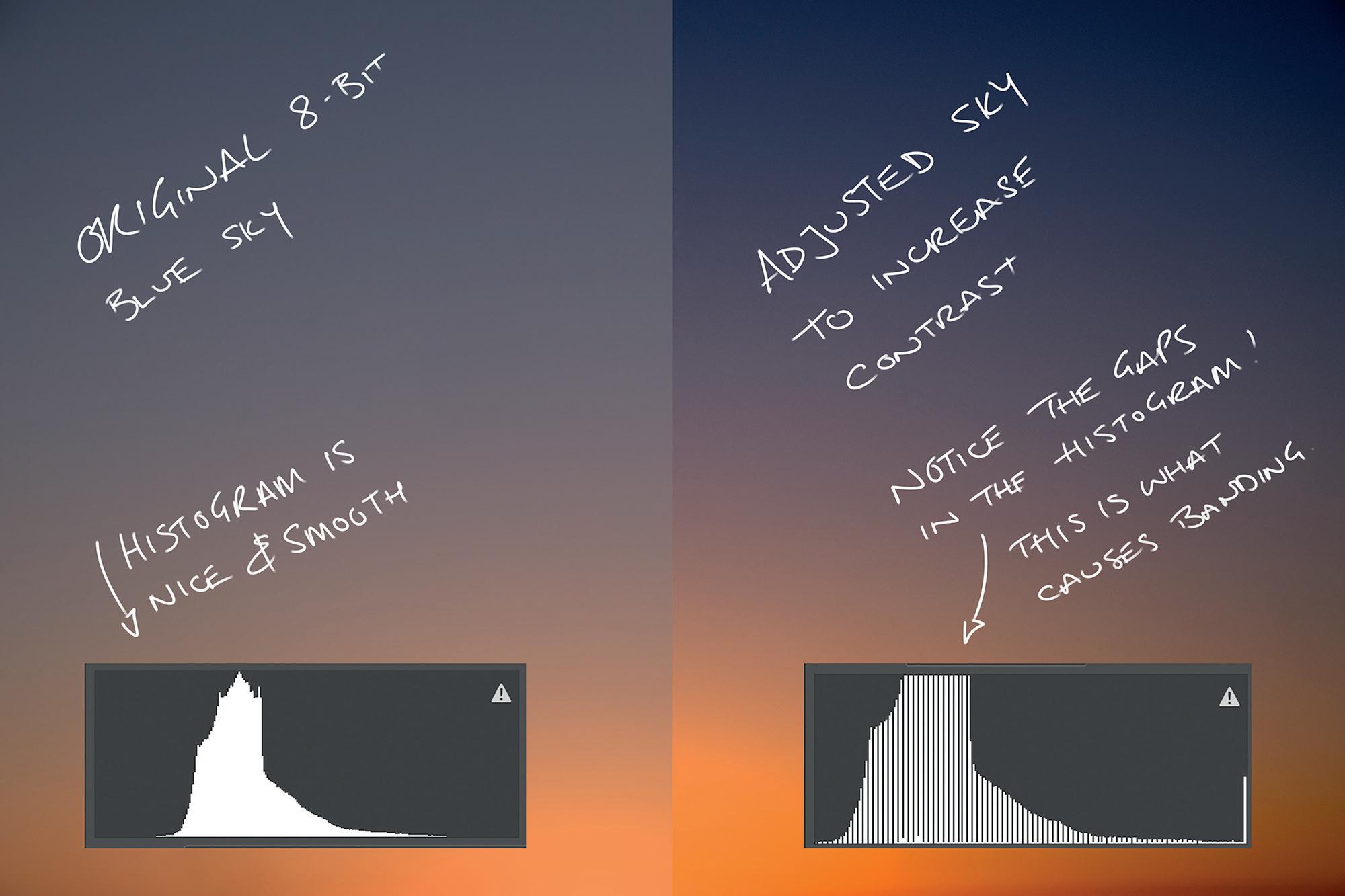

16.7 million colours may sound vast, but imagine an image with nothing but blue sky tones; suddenly, you are limited to something closer to 256 levels because only the blue channel (all 8-bits of it) is being used.

Ever wondered why you get banding in a blue sky when you edit an 8-bit file? Well, there you have 256 reasons - there aren’t enough visible levels in your file to truly represent mother nature. In addition, you may notice that your histogram has gaps in it - these are tell-tale signs that you have lost image detail. 12 and 14 bits per channel are more specific to RAW file formats. Again, a balance between speed and quality; the files aren’t as huge as 16-bit files but give a lot more information than 8-bit. For example, a 12-bit file allows 4096 levels per channel, while a 14-bit file provides 16,384. Just think of those silky-smooth blue skies!

Only a handful of high-end medium-format cameras or backs use 16-bits per channel. With 16-bits, you have 65,536 levels per channel, and the files are, well, large. That said, you may well end up using 16-bits per channel when you convert your file ready for Photoshop (or whatever is your editor of choice).

While RAW files may support 12- and 14-bit formats, standard image formats (JPG, PSD, TIFF etc.) don’t. The standard bit depths for editing are 8-, 16- and 32-bit.

Opening a 12- or 14-bit RAW file in your editor means you have to make another decision: do you downscale to 8-bit (losing some information in the file) or upscale to 16-bit (making the file a lot bigger and slower to process)

PAUL WILKINSON

Image 2 - when you edit an 8-bit file, you may spot gaps in your histogram

Only you can make that decision.

Incidentally, Photoshop technically uses 15-bits when processing 16-bit files. I threw that in there to keep you on your toes. It does this for historical reasons, and no good can come from retaining such useless facts - unless you’re writing plugins or filters, in which case it is critical information.

Feeling The Squeeze: Compression

Nearly all file formats support compression - and with bigger and bigger sensors, that’s a good thing!

Compression is a mathematical means for making a file smaller without losing that beautiful sunset that you’ve just captured. OK, maybe the sunset doesn’t come into it, but we’d never use compression if it completely wrecked your artistry.

Lossless Compression

Lossless compression is your best friend. Smaller files and, as the name suggests, nothing lost. So what’s the catch? Surely there has to be a catch? Well, there is - you can’t squeeze a file very much if you’re not willing to throw something away. But, much like a ZIP file (in fact, some image compression techniques are based on the ZIP technology, so loved when downloading large files), the compression downsize may only be about 25%. Not much to write home about.

Lossy Compression

Lossy compression, on the other hand, well, what information would you like to discard? You can throw away almost as much data as you’d like, and the files will be tiny. Crappy but tiny. How much you want to discard is entirely down to how you intend to use your image and what kind of image you are capturing. For instance, studio images with a white background can effortlessly compress to tiny sizes because the compressor figures out many pixels are identical. A woodland scene, on the other hand, will not squeeze nearly so well (but you might get away with heavier compression unless you zoom into the trees as the errors will get lost in the leaves!)

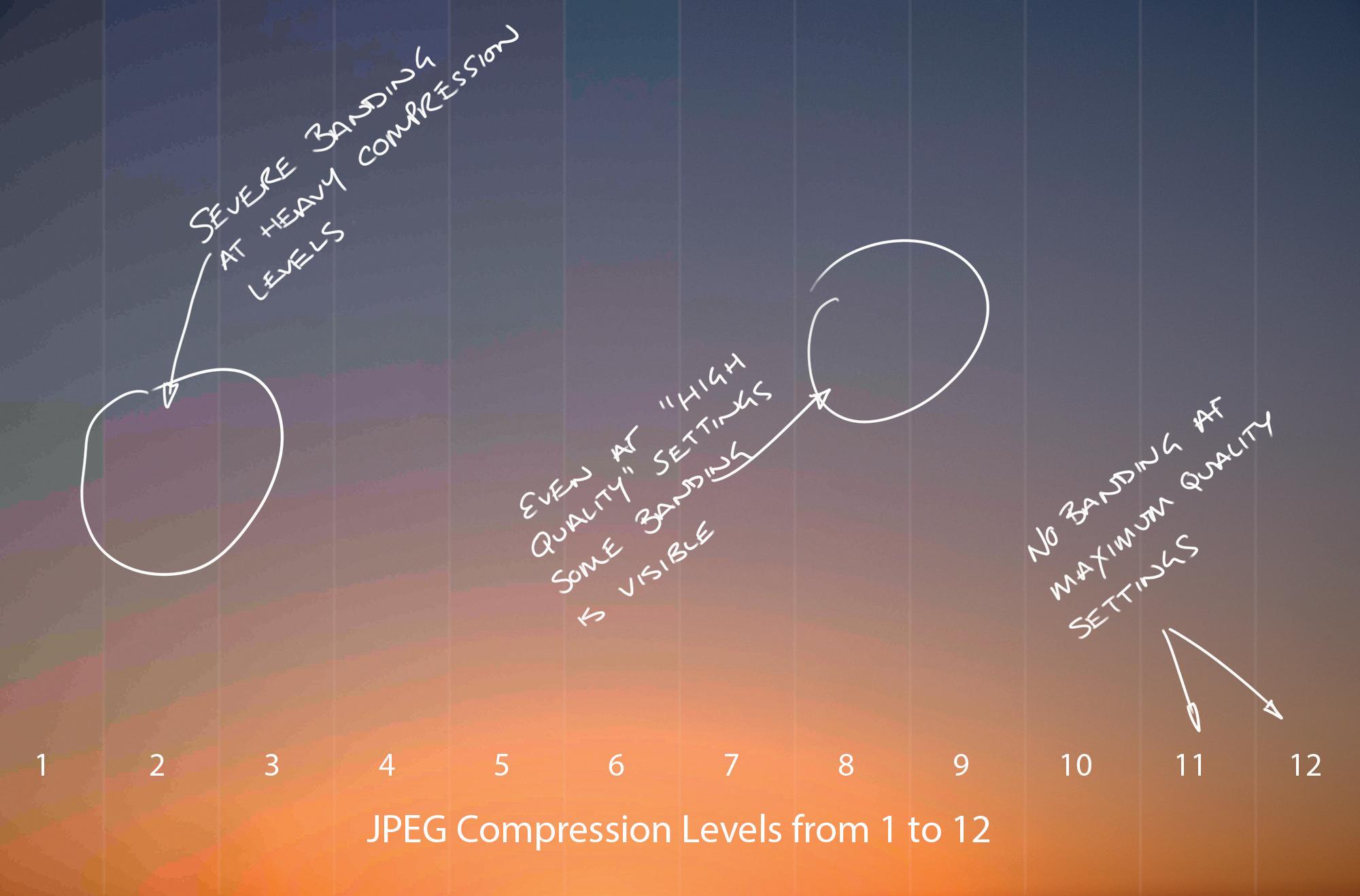

The thing about lossy compression is that you can decide how much detail you’re willing to sacrifice. Sadly there is no ‘compress it until the sky starts to look rubbish’ button, but there is a quality setting running from 0 to 10. Or 12 in Photoshop. I don’t know why it goes to 12. It’s a little Spinal Tap for my liking: “well, it goes to 12 dunnit...”

Every image will compress differently - sadly, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ setting you can use. For example, if you regularly shoot deep blue skies or smooth studio backgrounds, it might be worth keeping the compression set at higher quality. Conversely, if you shoot complex street scenes, you may well get away with lower quality settings.

PAUL WILKINSON

Image 3 - when you compress a file, you instantly risk compression artefacts - in this instance, banding across a blue sky

File Formats There are so many file formats out there we cannot cover them all - you only have to hit that ‘Save As...’ button in Photoshop, and the list goes on forever.

Each of those formats has its place, but we’re only going to talk about the ones we’re interested in as Photographers:

• RAW • JPG • TIFF • PSD

RAW Files

What on earth is a RAW file? Well, if you look through your file system for the extension “.RAW” you’ll be hunting around without a lot of success. This is because RAW files are not a file standard: the term RAW denotes the original, raw data from the camera’s sensor. And it is different for each camera manufacturer.

Most RAW formats (Nikon’s NEF, Canon’s CRW etc.) are based on the TIFF file format (see later), and each camera manufacture uses that format differently.

However, they all have in common that they stuff the data from the sensor (pretty much unprocessed) and a preview or thumbnail into the file. Thus, all of the data is captured, and a preview helps you quickly flick through them later.

By their very nature, RAW files give you a straightforward thing: the absolute maximum data your camera can provide.

RAW files are often nicknamed ‘digital negatives’ (in fact, Adobe defined its very own proprietary RAW format and gave it the extension DNG - denoting ‘digital negative’). Why digital negative? Well, if you cast your mind back to the days of film - yes, I know that some of you have never shot on film while others of you are clinging onto the stuff for dear life - you’ll recall that a negative wasn’t much to look at until it was processed.

And that’s the point.

A RAW file contains all the information you need to drag a great image out of it, but almost none of that work has been done at the point of saving. Instead, the camera saves the data from the sensor and then buries a record of all your settings like white balance and ISO sensitivity. And it creates a JPG preview using those settings so you can quickly see what you’ve done.

Oh, and by the way, even RAW files can be compressed - both lossy and lossless (look in your camera menu for the settings.) So why would you compress a RAW file? As always, saving on memory card usage, but compression will slow your camera and eat into your battery life.

JPEG Files

Well, JPEG files are, in comparison to RAW files, relatively simple and a lot smaller. JPEGs are limited to 8-bits per channel. That’s yer lot. Nothing more. But that still may be more than enough!

PAUL WILKINSON

Also, all JPEG files are compressed to some degree. Most people believe that JPEG files always use lossy compression, but if you keep the quality set maximum, it will default to lossless compression. Not many people know that. But it also somewhat negates the point of a JPEG file.

TIFF Files

The TIFF (or Tagged Image File Format) is the daddy of them all. It is a long-standing format, originally developed by Aldus Corporation in 1994 for desktop publishing (does anyone remember Aldus Pagemaker?!)

And it is very much still here.

It has been around for so long that nearly package supports it - it can hold 8- 16- and 32-bit images and supports a myriad of compression schemes - including JPEG. Huh? What? A TIFF file can use JPEG compression? Yup. In fact, a TIFF file can hold almost any image data in any format - which is why it is the basis of so many RAW file formats: you can store the sensor data, camera information and a preview in the file and just change the extension to NEF. OK, so I’m a little simplistic, but you get the gist.

They can also store layered files (including effects layers), which is the norm for anyone who retouches their images.

TIFF files are a versatile and long-lived format!

Photoshop PSD Files

Well, we can’t talk about files without at least mentioning PSD (Photoshop Document) files. These are the default for many of us and, just like TIFF files, can store anything you care to throw at it in Photoshop.

Just like TIFF files, PSDs can be compressed and will store 8- 16- and 32-bit images.

In-Camera: What Should You Use?

That is not entirely straightforward to answer: the problem is that each file format has its pros and cons and, depending on how you shoot. Most cameras will store RAW or JPEG (and a few will also allow TIFF) images. The problem with RAW and TIFF files is that they can be huge. But given the cost of memory and storage is more cost-effective all the time, saving space may not be your most significant consideration. And think of all that image quality!

If you never edit your files; each image arrives fully formed, has a house, a partner, a high-power career, two kids and a poodle, then JPEGs are for you. It will be hard to tell the difference between a RAW file (which is very big) and a JPEG (which isn’t).

If, on the other hand, you love to process your images - they are like children, needing nurturing to adulthood, absorbing time, stress and no amount of sleepless nights, then RAW files are for you.

I jest, of course, but there is a serious point. JPGs are a perfect end-format file; they’re great for printing and distribution, and even when printing large, you probably won’t notice the effects of mild compression. The 8-bits per channel limit will only really affect areas such as smooth skies, and, as long as you get the exposure spot on in-camera, there is little to be gained by using RAW formats.

RAW files, however, record the original data from the sensor at typically 12 or 14 bits per channel. That is significantly more information in the file (up to 60 times more information!) Underexpose a RAW file? No problem. Overexpose? Just push that slider in Lightroom. You have so much more data to play with that you can retain detail in the shadows and hold onto those highlights no matter your future decisions about the image treatment. But it will eat up storage and processing time.

Me? Well, I am a quality junky - I love single malts, fountain pens, vinyl audio and the best lenses I can afford. So why would I sacrifice even the slightest image quality given a choice? For me, it’s 14-bit RAW all the way and then 16-bit PSD files for editing.

Now pass me that glass; I have some whisky to enjoy as I edit those silky blue 16-bit skies with some eighties progrock in the background.

Photographer’s Insurance – What Cover do I need?

Andy Hearn is Managing Director of AIM Risk Services, insurance partners to the BIPP. Here, he explains what insurance protection BIPP members should consider, as a minimum.

When considering what insurance cover you need as a professional or semi-professional photographer, it is important to consider more than just damage or loss of expensive cameras, lenses and other essential kit – your business and livelihood is far more exposed to other risks than just this.

The financial repercussions from a customer having an accident at your studio or a client suing you for professional negligence could have a grave impact on your business and your livelihood. It is important that you understand these risks and the impact that they can have, should the worst happen.

The minimum level of cover that you should consider is Public Liability and Professional Indemnity. If you have employees, or an assistant that helps at the occasional shoot, you will also need to take out Employers Liability Insurance

Public Liability Insurance Why do you need public liability insurance?

Accidents do happen. When you are working out on location or at a client’s business premises or their home, if someone is injured or their property is damaged, you may be held responsible. A client may trip over your tripod or a cable, you may drop a client’s item that they have asked you to photograph. In these circumstances, it is possible that the client will make a compensation claim against you. Where you operate from a studio – the same risks apply. Even small claims can be expensive. More serious injuries, such as broken bones, with their possible long term effects, can lead to claims for many thousands of pounds plus significant legal fees.

What does it cover?

Public liability insurance covers your legal costs in defending a claim, and any compensation or costs that may subsequently be awarded, following:

1. Injury you cause to a third party during your business activities

WHAT COVER DO I NEED?

2. Damage you cause to third party property during your business activities

3. Personal injury or damage to property arising from any product you have supplied

Professional Indemnity Insurance Why is professional indemnity insurance important?

The fact is that not every shoot will go well. On rare occasions, bad luck or equipment failure will lead to the need for a re-shoot. That is fine if you can simply ask the subject to come back to your studio the next day. However, what happens when this is not possible, such as a wedding? If the shots are unusable, or are perhaps deleted by accident from a memory card, you can easily find yourself being sued for substantial damages.

Whatever the reasons behind a claim of this kind, they can be extremely expensive to defend, making professional indemnity insurance an essential consideration for professional photographers.

Just as importantly, professional indemnity insurance also covers you against civil liability claims such as alleged slander, libel or even breach of confidentiality and/or copyright.

What does it cover?

Professional indemnity insurance covers your legal costs in defending a claim, and any compensation or costs that may subsequently be awarded, following:

1. Professional negligence, such as giving incorrect in struction or poor advice to a client

2. Unintentional breach of confidentiality and/or copyright

3. Defamation and libel

4. Loss of documents or data

5. Loss of money or goods (for which you are responsible)

6. Buildings and Contents Insurance

Are there any other insurances that need to be considered?

The simple answer is – Yes. If you have employees or an assistant that helps out on the occasional shoot, you will need to take out employer’s liability – this is a legal requirement. Other insurances that should be considered are:

• Contents • Equipment whilst at the premises and on location • Business Interruption – loss of income • Cyber Insurance

How much does professional photographers insurance cost?

The cost of insurance will depend on a number of factors including:

1) What level of cover is required?

2) Do you have any employees – if yes, you will need employers liability insurance

3) What is the value of your equipment?

4) How much equipment do you take out of the studio or away from your home on location?

5) What is your annual turnover or income?

Premiums can start from as little as £12.00*per month based on Professional Indemnity Limit of £50,000 and Public Liability of £1m. Employers liability can be added for an extra £3.00* per month. The premium will increase if wider cover or higher limits are required. *premiums include insurance premium tax at 12%