7 minute read

Tony Hutchings

Six months in Peru

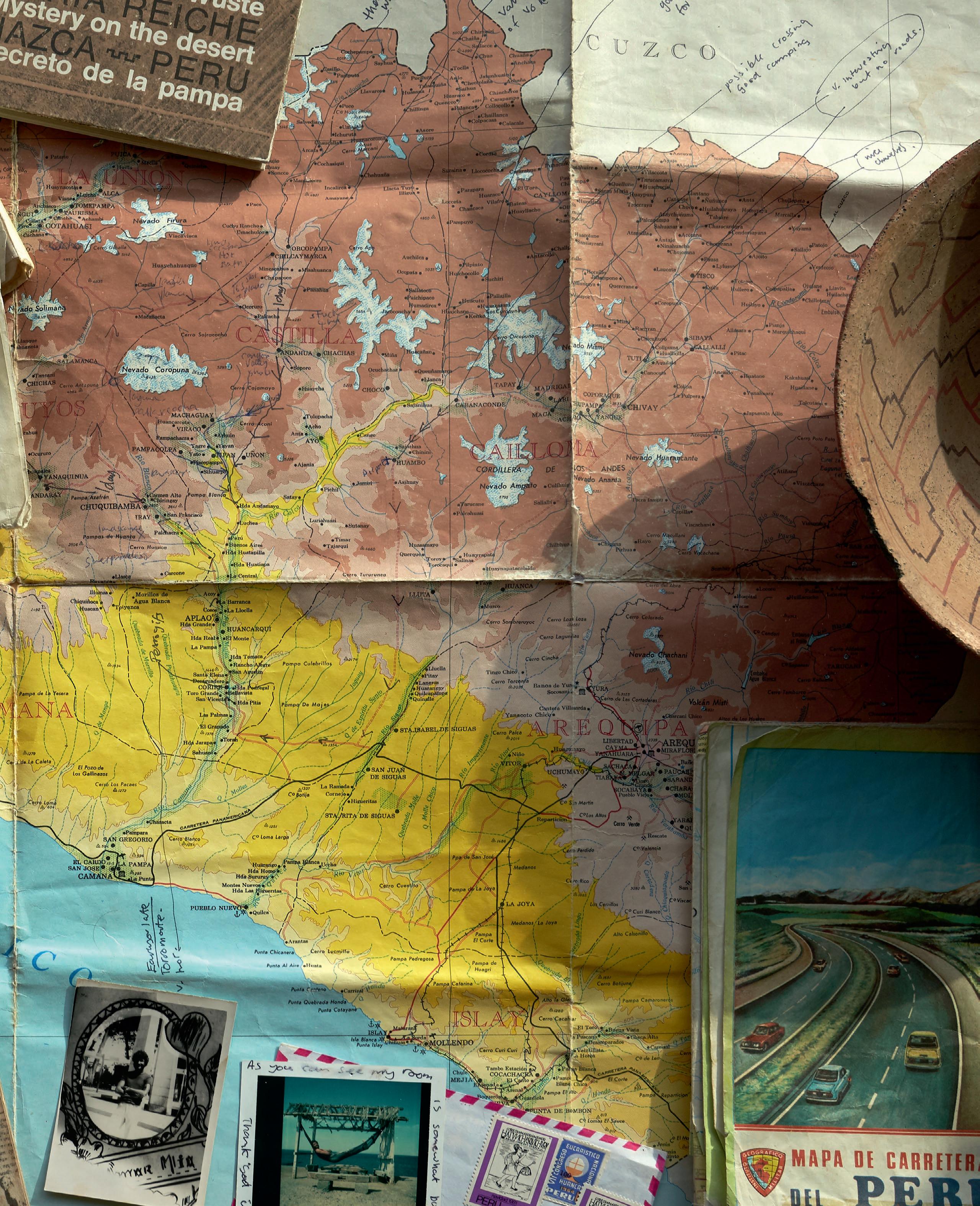

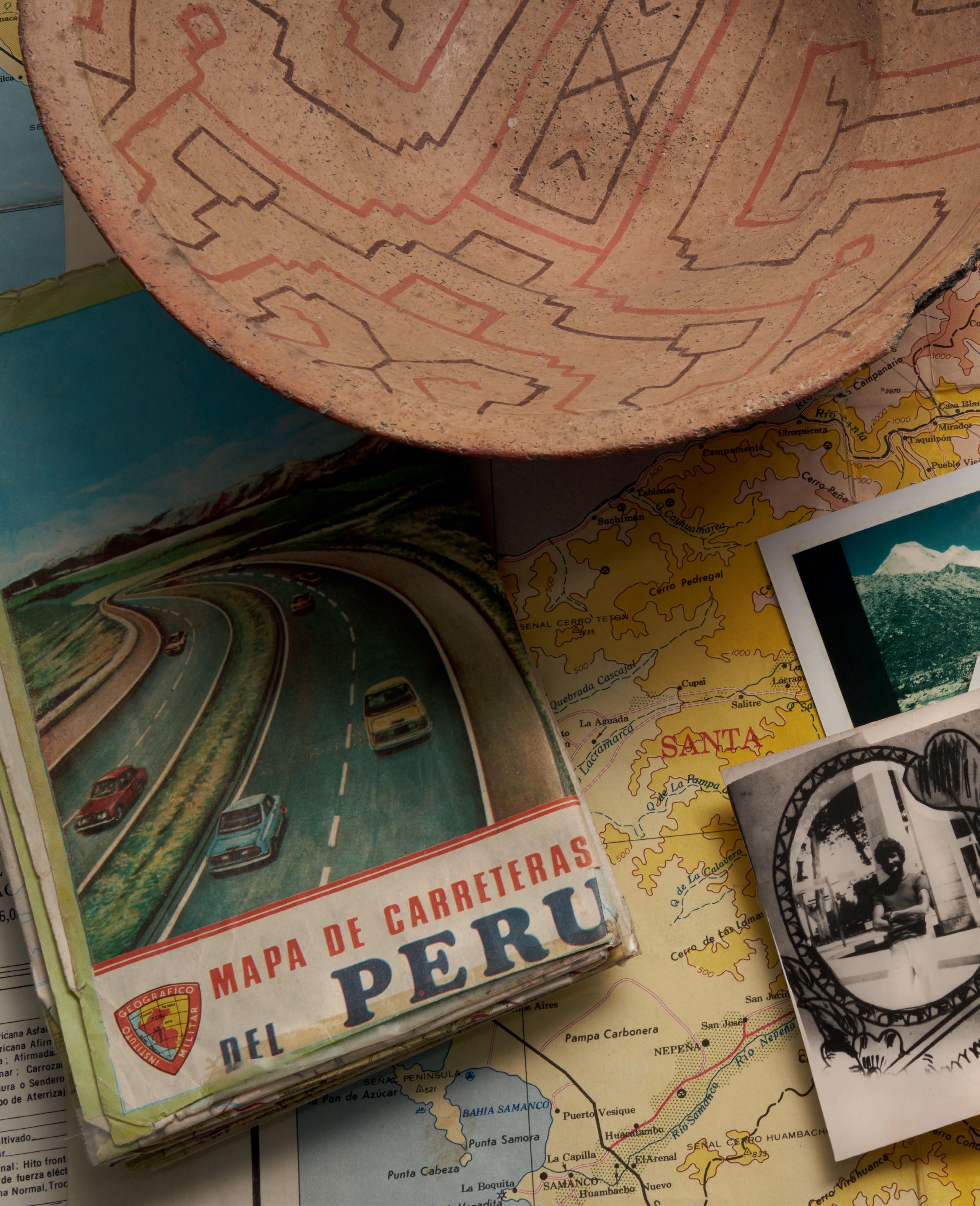

Back in ’82, studio portraiture and still life photographer Tony Hutchings left his Shoreditch, London base to take a cultural sabbatical to Peru, seeking to experience its people and landscapes first hand. Subsequent publication of the work was interrupted by the Sendero Luminoso – until now

Peru was, at the time, emerging from 12 years of military dictatorship, which left a legacy of underlying problems that would make travel to some places in 1982 difficult and hazardous. Tony was travelling pretty light, taking with him all the camping equipment he was likely to need, a copy of the South American Handbook, a couple of Hasselblads and a bunch of Kodak Ektachrome film.

The intention from the outset was to move around by coach but on arrival in Lima it quickly became clear that the plan was impractical, so Tony bought a VW Beetle and gathered department maps, local advice and fuel and set out on his own.

< Canyon del Pato ‘Many of the Andean valleys drop steeply down to the coast and are aligned east-west so as the sun sets, light travels up the valleys from a low angle. I was setting up to shoot this scene when a Toyota Landcruiser appeared –the only vehicle I saw for about 150km.’

mage © Tony Hutchings

I

Up in the mountains there were very few vehicles and very rough roads. According to the South American Handbook, Carmen Alto near Chuquibambwa (above) had some Inca ruins so Tony braved the rocky track to find them, finally arriving at dusk. He recalls, as if it were yesterday: ‘The car was immediately surrounded by about 30 inquisitive villagers, one of whom asked “what are you doing here, where do you intend to sleep?” When I mentioned camping, heads shook all around: the ground, it seemed, was full of rocks. A villager invited me to his house for dinner. There was no electricity and water came from the river – the meal served by his ageing mother consisted of three Andean potatoes and some sauce – people with very little were happy to share.’ Afterwards, Tony headed off to sleep in the Carmen Alto ‘Down to the river to get water for breakfast tea.’

mage © Tony Hutchings

I

Beetle and they told him to come back in the morning and join them for breakfast. But at around 10pm the young lad (above) knocked on the car window: ‘He said I should come to his mother’s house, as it was too dangerous to sleep in the car. I gladly accepted and slept on a bench in the house. The house was made of Inca stones – which is why there are often no ruins to be found. The marvellous thing about photography is that I can look at these pictures and perfectly remember the day accompanying them, almost 40 years on.’

Tony’s travel plans were largely based around the geography and weather conditions found in different parts of the country. Winter on the coast is the rainy season in the mountains – a traveller has to be in the right place at the right time (you can’t be in the Amazon Carmen Alto

mage © Tony Hutchings

I

when it’s raining non-stop). It’s a long country, too – the Carretera Panamericana (the Peru portion of the Pan-American Highway) runs for over 2,500 miles so there’s a great deal of ground to cover. However, before Tony could even leave for the first of two long coastal trips, Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands. As Peru was Argentina’s main ally, anti-British sentiment ran high, although people were generally very friendly and he made his journeys without issue. But it could well have been a problem considering his choice of format: ‘A limiting factor for me certainly was working with two Hasselblad 500Cs – one with a 50mm lens and the other a 120mm,’ says Tony. ‘Other than that, I had a Polaroid back and some film. The implications were interesting Pisac Sunday market ‘People come from surrounding villages, identifiable by their different hat designs. In 1982 they arrived on the back of pick-up trucks and it was very much a market for the indigenous community. Hopefully, mountain travel has become easier now. Fresh flowers on a young woman’s hat signals she is available for marriage.’

mage © Tony Hutchings

I

assuming I wanted to take pictures of people – I would have to approach them and ask permission in my poor Spanish. The people were very shy, but the Polaroids did everything for me, apart from the fact that the whole village would want one. That being said, I didn’t want the portraits to be particularly posed – which wasn’t such a challenge because they were not at all used to being photographed. I wanted the pace of the photography to feel authentic as a traveller passing through, almost unnoticed. Certainly I wanted to capture normal life, undirected.’

Indeed, Tony was embedding himself into the landscape through which he travelled – sometimes going a little bit too far: ‘I was camping most of the time and it was very cold in the mountains, San Jerónimo de Tunán Altitude: 3,274m

down to -15oC at night. Sometimes the Beetle wouldn’t start at high altitude. Once it broke down in the late afternoon on a dirt road and I had to sleep in the car. I ate lots of honey and lit the calor stove. I was awoken in the morning with the car simply full of frost by an indigenous man who certainly thought I was dead.’

Tony was sending film back to London throughout his trip – or trying to – that meant approaching people in the check-in queues at Lima airport to ask them to carry film back to his studio, with processing in Lima very much hit and miss – the emphasis being on miss. Despite getting as far as a book dummy on his return in 1982, Tony had to put the project to one side and get on with the rest of his life thanks to the Shining Path Sendero Luminoso launching a vicious civil war in the country which would continue for two decades, drastically limiting the appeal of the country as subject matter. However now, nearly four decades on and thanks in no small part to lockdown 2020, the work has been reborn in the form of the 220-page hardback book Peru 1982, priced £39 and available from peru1982.com. And – simply put – it’s a gem.

Iglesia Santisima: ‘Mountain Indians prepare for a long return journey to their village after having the head of their cross ‘re-charged’ in church for another year.’ Pan-Amercian Highway > ‘There were plenty of these shrines to be found, usually on bends, in this case by a precipice.’

mage © Tony Hutchings mage © Tony Hutchings

Searching for the sweet spot

This is an unashamedly back-to-basics short discussion of one corner of the ‘exposure triangle’, being aperture – or how big the hole is – and questions whether in our day-to-day photography we tend to assume a smaller aperture (bigger f number) is required to achieve a shot than is actually the case Spot check > Canon EOS 5DS | L 24-105 mm | 35mm | 1/25 sec | f/11 | iso 100

This image takes us back to the snows of early February this year and is particularly appealing because of how it communicates the transformative capacity of the seasons. It’s been years since there’s been lying snow and frozen ground for nearly a week and, coming after a wet spell, the river had recently flooded so causing this somewhat forgotten football pitch to freeze over. But thinking about the technical aspects of the shot, of primary concern is front-to-back depth of field. In this case, from the sledge tracks entering the bottom of the frame all the way to the far trees on the skyline. Of particular importance are the goalposts, naturally enough, which make the picture what it is.

With all of that in mind, and with light fading fast on a winter’s afternoon, you can see from the spot check above that the chosen aperture was f/11. The question posed here is whether that choice was the right one – or whether a sharper image could have been attained with a bigger aperture whilst still achieving the depth of field demands of the composition.

So what is the relationship between image sharpness and aperture? In short, any given lens will have a point of