Region

Platzhaltertext

Material/Konstruktion

Lehm, Holz, und weitere Materialien

Klimazone feucht, warm

Region

Platzhaltertext

Material/Konstruktion

Lehm, Holz, und weitere Materialien

Klimazone feucht, warm

Fujian Tulou

Qinghua Guo

Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze für beide Bilder

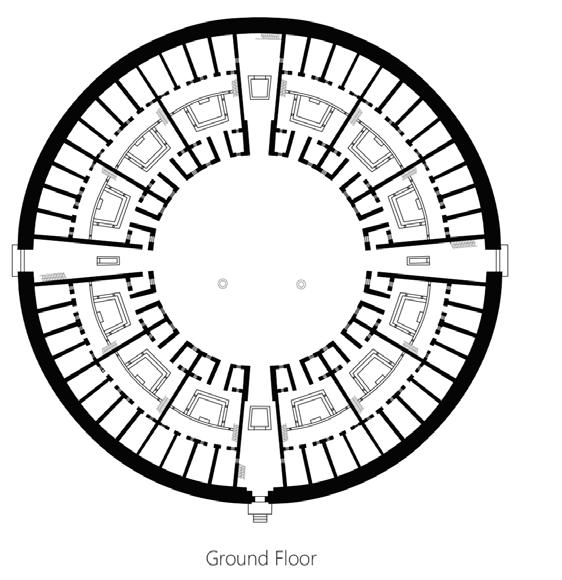

Tulou (lit. ‘earthen tower’) is a type of communal dwelling, originally designed to accommodate a whole clan (a group of families who share the same family name or an extended family) in Fujian province, China (Figure 1). It is a squared (or nearly squared) or circular edifice, made of a fortification wall of rammed earth and a storeyed building of timber frame built against the wall, thereby creating an inward-looking central courtyard. The timber structure formed family units evenly and equally which is consistent with yard. Most of tulou had only one entrance leading to the courtyard. Tulou was chiefly built by Hakka (lit. ‘guest families’) whose ancestral homes were in northern China. In a series of migrations since about the 10th century, the Hakkas moved and settled in the South. In their new homelands, tulou were designed with defense in mind to protect their life from the unfriendly pre-existing populations as well as brigands. The forms of tulou are rich and complex, demonstrating the change and persistence of specific modes of life and cultures. Over 3000 tulou constructed between the 15th and 20th centuries have survived in Fujian; squared and circular tulou are almost equal in number (Figure 2).

The oldest tulou in Fujian is Gufeng Lou, said to date from the 12th century. It is 31.8 x 29.62 m in plan and four storeys in height, containing 22 family units in shared ownership (Figure 3-A). The external and internal walls of Gufeng Lou are all rammed-earth walls. Against the internal walls there is a minor s tructure made of wood. The wooden structure is used a s service or transitional spaces (kitchen or corridor). The courtyard (13.5 x 11.4 m) with a well is the focus and the center of daily activities. There is one entrance which opens onto the courtyard giving access to all family units. Inside the tulou, stair s are shared leading from one level to another. Generally speaking,

Building with Earth and Timber: Fujian Tulou

there are several possible locations for stairs: opposite the entrance (see Figure 3-A), inside the entrance (Figure 3-B), at courtyard corners (Figure 3-C), and in the corridor (see Figure 5-1). The family units are vertical and identical: food preparations are on the ground floor directly onto the courtyard area, a storeroom for grains above, and bedrooms on the upper levels. The rooms are small, about 10 sq. m and 2 – 3 m high. All units are connected through corridors (Figure 4). The corridor is cantilever and open to admit light into the upper rooms and overlook the central courtyard. This arrangement is called ‘corridor type’ by modern scholars. The vertical-unit and central-courtyard design is convenient for both family living and communal life. In the center of a tulou, the courtyard is a sunken area to allow rain water drain off easily (Figure 5-1). For an enclosed compound, good drainage is essential. The building is covered with tiles to reduce the risk of fire and to keep the roof in good condition. The eaves overhang around the corners to protect the walls against rain (Figure 5-2).

The largest round tulou in Fujian is Chengqi Lou (1709, rebuilt 1929), consisting of four concentric annular ring buildings. From the center to the perimeter, they are: ancestral hall (also used as community school), storage/study rooms, guest rooms, and family units. The inner three are all single-storey buildings (the guest house is partially two-storey) and the outermost is four-storey and 62.6 m in diameter. This tulou has three entrances: a main gate and two side gates. For security purposes, very small windows are opened in the upper exterior wall. The openings are angled slightly further apart towards the inside (Figure 6). Fujian has a subtropical monsoon climate with moderate winters. The earthen wall shelters the residents from both heat and cold. Rooms rely light and ventilation from the courtyard. Overhang eaves are wide for drainage (Figure 7). The space under the eaves is for storing household goods (Figure 8).

Eryi Lou (1770, rebuilt 1904) represents a different arrangement – ‘courtyard within courtyard’ – named in this paper. The tulou consists of two concentric annular ring-buildings with a central courtyard. The inner ring building is single-storey and the outer four-storey (71.2 m in diameter). The two rings are connected by a roofed structure at 3-bay intervals. As a result, 12 inner courtyards were formed in between. Eryi Lou is equally divided

into 12 family quarters. Each consists of a front building of three-bay wide, a rear family unit of 4-bay wide and 4-storey high, two flank buildings and a private court yard. The tulou has three entrances which open onto the central courtyard which, in turn, gives access to 12 family quarters (Figure 9-A). The front house accompanies a doorway with a kitchen and storage on each side. One of the flank buildings contains a stair which is used by the family only. Unlike Chengqi Lou discussed above, Eryi Lou has no common ancestral hall, but a private ancestral room on the top floor of each family unit. The perimeter wall of rammed earth is battened and stepped to receive floor joists, 2.5 m at the bottom and 0.8 m at the top, creating a 1 m-wide corridor behind the ancestral rooms, providing access to all families (Figure 9-B).

Jiqing Lou is characterized by vertical family units and horizontal common corridors, plus private stairs. It is a circular tulou of 4-storey high and 66m in diameter, with a big central courtyard. The courtyard serves as an open-air living room for the whole clan, within which is an ancestral hall where the center of all collective activities taking place.

The history of Jiqing Lou can be traced back to 1419. Sometime in the history, many staircases were added. That is, the family units became staircase orientated – with private stairs leading from the courtyard to the top level. The staircases built on the corridors on the upper levels are all different and each is a unique design (Figure 10).

Tulou was constructed with earthen walls and post-beam frames. The preferred timber is China Fir seasoned (air drying) before use. Floor joists span from beam to beam, and the end of the joists rest directly upon the earthen wall. The roof was finally laid. The lower levels of the building were soon occupied, but the upper part remains uncompleted for years. Secondary building works – partitions, doors and windows – will not be resumed until the families grow and more rooms are needed. That is, the tulou was partially exposed in all possible unfavorable condition for years. The timber frame is moved and distorted, thanks to the earth-timber structure, the movement is stabilized,

Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für unterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für unterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder

Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für unterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für unterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder

Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder Kurze Bildunterschrift für beide Bilder

and the tulou is still standing (Figure 11). After typhoons and other disasters, it is necessary to repair the severely damaged parts of tulou, for instance the eaves and tiles, earthen walls, floor joists or verandas. In general, tulou has relatively long life-span. When an extended family grew bigger beyond the existing household, a new tulou would be built in neighboring or available sites.

The perimeter ring was constructed, and the inner ring was added then. Sunyu Lou was built in 1927, the outer ring is a 4-storey building and 74 m in diameter. The inner ring is 4m

apart from the outer one, and completed a quarter (Figure 12). For defensive purposes, the outer ring is necessarily high. It is possible to build an inner ring with limited height within a big courtyard.

The external wall of tulou is massive, consisting of tamping earth, rammed layer by layer in a formwork. Paddling the wall with wooden paddles immediately after the formwork was removed to gain consistency (Figure 13-A). The rammed earth forms a homogenous mass which can be built up to 3- to 5-storey high. There is no scaffolding for wall building. Several teams can work

on the same course, in which case the work is rapidly completed and the moist earth dries homogeneously (Figure 13-B). Lengths of Bamboo strips were built into rammed-earth wall to take tensile stresses. The tiled roof with wide over-hanging eaves (over 2 m) keeps the roof structure in good condition and to protect the wall. No external render was applied (Figure 14). Tulou was constructed with excavated foundation. The width of the foundation is double that of the wall; and the depth, for example, is 30 – 60cm for a 3-storey tulou. The foundation was filled with stone rubbles and the stone substructure extended above the ground level to form a footing of 0.6 – 1 m high. On the top of the footing, a layer of tree barks was laid to protect against rising damp (Figure 15).

The earthen wall is battered from the base to top and stepped from floor to floor. When the level of the floor is reached, a series of parallel wooden logs are placed on the wall. The wall was continually built up, and the next floor joists are laid in the same way. Purlins forming the roof-frame rest directly upon the earthen walls. Tiles are laid on the rafters to complete the roof surface. All the members are visible to the eye (Figure 16).

Conclusion

In Fujian, two forms of tulou are discerned: circular tulou and square tulou. Expect forms they are remarkably similar in spatial arrangement, building materials and construction techniques. What appears to have happened is that in plan the round tulou became square but otherwise little altered, and vice versa. One advantage of the circular plan over the square one seems that the former offers equal units than the latter in terms of orientation. The squared tulou has one main side, thus a prestige facing direction. Identical family units indicate that the architectural design and planning intertwine with the cohesive social fabric of kinship, but the social hierarchy. It is clear that tulou shows cultural continuity and building standardization. Two basic types are distinguished: vertical unit with horizontal corridor, and courtyard within courtyard. In terms of typology, the former was older than the latter. In terms of function, the former is

suitable for an extended family with a direct lineage, and the latter is suitable for a groupof people with kinship-based bonds. In any case, people living in the same tulou cannot marry one another.

In Fujian, squared tulou co-exist with circular tulou. The question as to whether or not circular tulou is older than the squared tulou is unanswerable. Let us extend our consideration from architecture to archaeology. Based on archaeological evidence, circular buildings and squared buildings were both apparent in Neolithic China. Figure 17 shows earthen houses at Erdaojingzi (Lower Xiajiadian culture, ca. 2000 – 1500 BCE), in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China. The building materials and construction techniques used were various, such as coiling reed-mud rolls, mud bricks, rammed earth, etc. There is no reason to assume that tulou and Erdao jingzi are related. However, Erdao Jingzi provides a window to see the history of earth building that illuminates the tradition were practiced two millenniums before the date of tulou.

Reference

Huang Hanmin and Chen Limu zhu, Fujian tulou jianzhu. Fuzhou: Fujian Science and Technology Press, 2012.

Zhen Guozhen (ed.), Fujian Tulou. Beijing: China Encyclopedia Press, 2007.

Lu Binjie (ed.), Measured Drawings: Tulou at Shizhong in Longyan, Fujian. Beijing: China Building Industry Press, 2011.

Qinghua Guo, ‘Types and Techniques of Earthen Architecture in Erdaojingzi and Yanik Tepe (2000 BCE),’ Chinese Architectural History, Vol. 15, 2018. Beijing: China Building Industry Press.