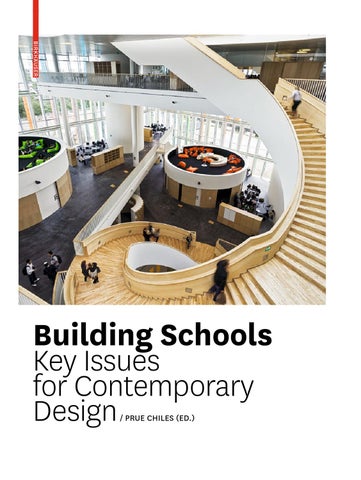

Building Schools Key Issues for Contemporary Design / PRUE CHILES (ED.)

The design of educational environments is a rewarding field in architecture. The planning of schools commands enduring attention. This publication explains in ten chapters the central parameters for this building type: the integration of new pedagogical concepts, environmental design, flexible spaces for learning, the role of schools in the community, participation in the design process, learning outside the classroom, landscaping, opportunities and challenges of special schools, refurbishment solutions and good furniture choices. Each topic is analysed in depth and illustrated with exemplary international projects. These model solutions provide practitioners and researchers with inspiration and ideas for specific design aspects.

www.birkhauser.com

Building Schools Key Issues for Contemporary Design / PRUE CHILES (ED.)