Essays on the Essence of the Garden

Birkhäuser

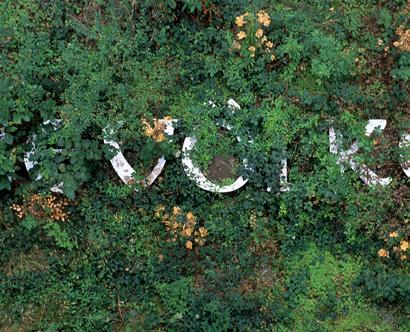

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe 34

The

Catharine

The

The

Heterotopia: The Garden as a Metaphor Martin

175

The Garden as

Aleš

The

The

In the film version of the story Alice in Wonderland,1 Alice does not spot the White Rabbit in a meadow but beside the meticulously trimmed hedge of a garden maze. The creature strikes Alice as somewhat unusual, somewhat adventurous, and her boundless curiosity lures her down the rabbit hole, where she lands in a place called Under Ground. The Under Ground is presented as an enchanted, mysteriously beautiful, but slightly frightening garden, both strange and miraculous, and it eventually leads her to the realm of the absurd.

First, there was the garden. And this is true of both of the garden’s most extreme forms. In the first of these, the images of the carefully cultivated garden in the film present a metaphor of an orderly, socially rigid, refined world, a cosmos in which, despite unanswerable riddles, it is possible to understand this world precisely because of its order. Not only understand it, but master it. In the second of these forms, a wild place is revealed, teeming with unusual, unearthly flora and fauna, not least the strange Cheshire Cat. It is a world of endless possibilities, untameable and unpredictable, intangible and inexplicable, full of surprises: an infinitely attractive world of wonders. Thus, the garden is cultivated and untameable, even both at the same time: anything, to put it simply, can happen in the garden.

The fact that there was a garden from the very beginning is also thematized by the essays in this book, which range from presentations of in-depth studies about the meaning and role of the garden, accompanied by lucid insights born of keen

Rioan-ji, Kyoto, presumably late 15th century; the enclosure is carefully premeditated to help meditation.

Shoden-ji, Kyoto, is an example of an enclosed garden. It adopts the principle of shakkei (borrowed scenery), as Hiei, a mountain in the background, is drawn into its visual composition. First half of the 17th century, renovated by Mirei Shigemori in 1953.

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Gardens can be conceived in many ways, from many angles and through many lenses: as a social space, a place for activities or relaxation, an outdoor room, a catalogue of plants, an ecological safe haven, an exhibit of its owner’s wealth or creativity, an expression of culture, a place of joy, a gardener’s cause for eternal worries, or a representation of the cosmos. Underlying all of these, the garden has always been a reflection of the relationship of man and nature, a relationship that changes over time, and is as much a reflection of its time, and thus a cultural expression.

Over time, the understanding of our relationship to nature developed from that of fragile creatures in a fearsome entity to the heroic story where man is conquering nature, which in Western culture culminated in the Baroque garden. In the Romantic period nature was idealized as the source of all good, the mirror of the human soul. In the 20th century, the concept of nature oscillated between an ancient sense of nature as a cosmic order, full of symbolic potential, and a rather simplistic expanse of undefined greenery, and the idea arose that whereas nature is necessary for the human well-being, mankind can only corrupt nature or, if they tried hard, preserve what remains. So it is

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Parc aux Angéliques, Bordeaux, France: the post-industrial park encompasses phytoremediation areas on the brownfields of the Garonne riverbank, which are gradually transformed into a green public spine, under the auspices of MDP – Michel Desvigne Paysagistes.

Quai des Antilles, Nantes, France: this former quay of an abandoned wharf forms part of the Île de Nantes urban transformation project, where an evolutionary “plan guide” introduced in 2000 by Atelier de l’île and Alexandre Chemetoff ensures the radicantity of the design.

In these turbulent times, the garden sometimes seems an irrelevant issue for landscape designers and design researchers, or at least not worth referring to in their efforts to face the greater environmental problems. Is the garden really so irrelevant? Environment, said French landscape architect Gilles Clément in his inauguration speech at the Collège de France in 2011,1 is just the way of naming nature by those who think they can master it. For him, this means to reduce nature’s biological complexities and sensorial qualities into a scientific system of objective, measurable elements that can be understood by everybody always in the same way. The acidity of a soil can be measured with the same instruments and expressed through the same parameters in Europe, Africa, and Asia; the acoustic value of a site, the radiation emission of a rock, the CO2 charge of the atmosphere, the pollution of a water course are captured the same way all over the globe and communicated in what Clément calls a “scientific Esperanto”, an engineered language that does not touch anybody’s emotions. Landscape, however, says Clément, is equally nature, but grasped another way, through the senses. It is what expands around oneself and what the view embraces, or, for the blind, what all the other senses embrace. Landscape is also what remains in memory when one’s body has left the space in which the senses were actively capturing impressions. Impressions are of course intangible, ephemeral, subjective – hence suspect to those who ask for objectivity to master the world.

For Clément, there is a third category beyond the “environment” and the “landscape” – the garden. It unites and

1 Gilles Clément, “Jardins, paysage et génie naturel”, Paris, Collège de France, coll. “Leçons inaugurales”, 222, 2012, http:// lecons-cdf.revues.org/510,When I first heard about the cherry and apple trees deep in the Kočevsko forest, trees that had once been cultivated and have since been absorbed into the wild, my previously unquestioned ideas about architecture began to waver, perhaps for the first time. There was a time when the Kočevsko region was a considerably less forested and much more populated landscape than it is today. From the 14th century onwards, the region of southern Carniola was populated in clustered settlements by the descendants of Eastern Tyrolian colonists who became known as Gottscheers. Upon their arrival, the colonists cut down the forests, organized the land for agricultural purposes, and created a unique cultural landscape out of what was previously wilderness. They spoke a quaint southern Bavarian dialect and settled in about 180 hamlets and villages. The region around Kočevje was poor, and, except for the churches and the ducal mansion in the town of Kočevje, did not have many old or well-constructed buildings. Most adult men, because of poverty, peddled goods throughout the Holy Roman Empire, returning to their homesteads, their wives and children, their fenced

Landscape in the region of Kočevje in southern Slovenia, which was home to a German-speaking community from c. 1330 until 1941.

Landscape in the region of Kočevje in southern Slovenia, which was home to a German-speaking community from c. 1330 until 1941.

Cherry tree in the forests near Kočevje.

Cherry tree in the forests near Kočevje.

1 John Dixon Hunt, Greater Perfections, The Practice of Garden Theory, London: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

2 The word can be traced to the late 13th century and comes from Old North French gardin, denoting a (kitchen) garden, an orchard, or palace grounds. It is related to Old French jardin, from Vulgar Latin hortus gardinus, in the sense of “enclosed garden”. The Frankish word gardo and Germanic gardan is also the source of Old Frisian garda, Old Saxon gardo, Old High German garto, and German Garten. Old English geard and Gothic gards means “enclosure” which is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root gher-, “to grasp, to enclose”. Italian giardino and Spanish jardin come from French.

3 See, amongst others, Gabriele Uerscheln and Michaela Kalusok, Kleines Wörterbuch der europäischen Gartenkunst, Stuttgart: Reclam, 2001.

The term “garden” has different uses in colloquial speech and professional terminology, but even in the latter is used in a range of different ways; moreover, like all sociocultural expressions, it is subject to constant transformation of meaning. In a general sense, it is futile to assert with any certainty which object is meant by the word garden. “What on earth is a garden?”1 asks John Dixon Hunt in his treatise on garden theory. The sheer scope of the concept makes it impossible to delineate. The meaning in the word stem, pointing to a boundary,2 was lost long ago. “Garden” became synonymous with park, a fact that runs through the cultural history of the art of the garden,3 as well as through the history of professional landscape architecture. What is more, not only public but also private green spaces are called gardens. “Garden” as a term with an obvious or even offensively positive connotation is also used for places (i.e., tourist destinations) or projects (i.e. housing or shopping malls) for the sake of economic exploitation, which is particularly convenient in relation to real estate. In the imageladen language of marketing, real estate also almost always boasts of gardens; but in what is actually built, gardens are no longer as prominent. The observation that the concept of the garden is applied to embellish our imagination allows conclusions about its meaning which seem to lead back to paradisiacal origins. And in the professional context, five decades ago, when landscape architecture began to gain ground beyond

A wide variety of tree species such as oaks (Quercus robur, phellos, palustris, cerris), birch (Betula pendula) and robinia (Robinia pseudoacacia) was used in Nike Campus, Hilversum, Bureau B+B, 2020.

Natural chaos within the order of a constructed space: the atrium garden “Asphalt Jungle”, Paris, Wagon Landscaping, 2022.

Natural chaos within the order of a constructed space: the atrium garden “Asphalt Jungle”, Paris, Wagon Landscaping, 2022.

“The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible.”

Michel Foucault1It is not an exaggeration to say that the cradle of humanity is in the garden. In our collective narratives, God does not create houses – God creates landscapes and gardens. An important founding myth of mankind and human culture hence starts here. The lost paradise nourishes manifold subsequent narratives in which the garden is the metaphor for an intact reality and an existence of ease. Today, the garden is a man-made utopia. While the paradise is the work of God, we become creators ourselves when we make gardens. Yet in doing so, our achievements are doomed to fail: like Camus’ Sisyphus, maintaining a garden means to start over and over again – a mode of being that allegorizes the human condition already quite accurately.

As a metaphor, the garden expresses realities and utopias simultaneously. Gardens symbolize visions – be it individual desires or collective dreams. This is especially true for public gardens that possess imaginative functions for the communities who

Heterotopia: The Garden as a Metaphor

Aerial view of Superkilen park, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Aerial view of Superkilen park, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

In the year 2000, the artist Hans Haacke launched a project entitled DER BEVÖLKERUNG (for the populace, for the folk) in the context of the construction of the parliament building (Bundestag) in Berlin, the capital of united Germany. The purpose of the work commissioned by the German government was to symbolize the politics of the new Germany. One of Haacke’s starting points in terms of his reflections on the theme of the project were the words under the tympanum on the Eastern part of the parliament building. The caption from 1916 was DEM DEUTSCHEN VOLKE (for the German people), suggesting at the time that the focus of political activities in parliament was the care of the Germans, specifically people who were German by blood, or the nation sharing a common history, cultural legacy, and affiliation. The contentiousness of this slogan was the starting point of Haacke’s artistic project. The artwork DER BEVÖLKERUNG is a response to the previous text visible on the façade of the building, using the same font – developed by Peter Behrens – as the 1916 inscription. The words DER BEVÖLKERUNG written with neon letters ninety centimetres high constituted the central part of a garden that Haacke placed in the northern atrium of the parliament building. He conceived of the symbolism of the territory and politics of Germany in the form of a twenty-one metre long and seven metre wide garden surrounded by a thirty centimetre high frame. In contrast to the title on the façade that we see from below, Haacke’s project is visible from the roof of the parliament, which is accessible to all visitors.1

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Photographs by Anne Schwalbe

Never before had the garden to fulfil so many demands as it does today. It is a refuge from digitalised life and acts as a bridge to nature. As a man-made place where plants grow, it is cultivated and untamable at the same time. While for centuries the gardener’s ambition was to control and subjugate nature, today it serves more as a place for retreat, a possible surrogate for wilderness, a habitat for animals or it fulfils the dream of self-sufficiency.

In this book, landscape architects, sociologists, architects, artists, art historians, writers, poets and philosophers illuminate manifold aspects of the garden in the Anthropocene in several chapters: the garden as a place of community, garden as art, garden as a place of enchantment and rapture, opening up questions of what garden as a model could stand for. The beguiling images by the renowned photographer Anne Schwalbe create a narrative in its own right.