Discovering Early Modernism in Switzerland

The Queen Alexandra

Sanatorium

Daniel Korwan

Birkhäuser

Basel

This monograph is based on the doctoral dissertation “The Queen Alexandra Sanatorium. Early Modernism in Davos” (doctoral advisors: Prof. Hermann

THIS IS A STORY

This is a story about a building. It is however not a story about glamour or about the fabulous work of an architect.

This is a story about endless discussions, permanent financial limitations, about personal animosities, about the banalities of construction.

This is a story about how the exhausting negotiation between all these factors lead to the materialisation of an artefact.

This is a story that will help to develop an understanding of a project forgotten by history.

This is a story that will reveal unexpected developments just like irregularities in the process of constructing a building.

This is a story that will help making clear that a building is far more than an entity standing in the countryside.

This is a story about an amalgamation of hopes, fears, decisions, arguments.

This is a story about architecture on the verge of modernism.

New materials and construction methods like steel, glass and reinforced concrete were among the main practices that shaped modern architecture. How were the new construction methods expressed in architectural terms and how did a new architectural paradigm emerge? Intensely discussed in the literature, this has become a classical question. Nevertheless, it is also a topical question as some of the archetypical examples and narratives of the then-historiography have so far not been critically re-enacted. This is the case with the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in Davos (1903–13), which during the transition to modernity, created a new aesthetic by following the logic of reinforced concrete. The architects were Otto Pfleghard and Max Haefeli. The engineer Robert Maillart was significantly involved in the development of the construction. While the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium passed almost unnoticed at the time of construction, in the 1920s it attracted the attention of Richard Döcker and Sigfried Giedion – later most famously in Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture (1941). Both of them saw the building as a precursor of the modernist principles of Licht, Luft, Öffnung, and for an architecturally significant use of reinforced concrete. In a later era, the sanatorium was almost forgotten once again. It is to the great credit of Daniel Korwan that he has critically comprehended the genesis of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium and investigated how the admired features of the building emerged.

In order to critically re-enact the process through which the building was created from conception to realisation, as well as to understand its architectonic features, a method based on sources and evidence is necessary. It was difficult to access the inside of the building. But Korwan was able to unlock a multitude of unexplored archival sources in Zurich, Thurgau, Davos and London, including a completely unknown part of Maillart’s archive concerning the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium. Thanks to these newly found sources, new results in the field of construction history were achieved (among many other outcomes). Maillart had criticised Hennebique’s monolithic skeletal system, which at that time was omni-present, saying that its posts and beams would continue the logic of steel and wooden construction. Maillart instead called for a specific construction language for reinforced concrete and a renewed architectural language in consequence. The present book shows that the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium is a materialised testimony of this quest. Following the sanatorium logic, where the patient’s rooms with balconies in

front necessitated a maximised opening between inside and outside, Maillart freed the ceiling slab from all supporting elements, beams and joists and made an important step towards the ‘flat slab.’ By exploiting the specificities of reinforced concrete as a material, Maillart made way for a structurally honest approach to openings and horizontality in architecture, enabling what Korwan calls the ‘free section.’

As a re-enactment of the genesis of a building in all its complexity and multifaced dynamics, the book benefits from and greatly contributes to an epistemic history of architecture, which investigates the knowledge base of architectural endeavours. Following this approach, a building is seen as the result of the cooperation of all people involved –the architects, engineers, construction workers, construction companies, clients, building authorities, standardisation committees etc. –and the interaction of their respective knowledge inventories. By doing so, innovation mechanisms, decision-making processes, the organisation and distribution of knowledge or the division of labour become visible. Innovations regularly do not just happen in the mind of a single person (i.e. a ‘genius’ architect or engineer) but can only be understood in a wider epistemic setting, which includes all the people involved and their respective creativity. In the case of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium, Maillart did not achieve the reinforced concrete innovations alone, nor did his construction firm as a whole; rather, we have to include the architects who insisted in bringing Maillart’s firm into the project, the client, who wanted a functionally optimised building and favoured pioneering construction methods, as well as the standardisation committee, Schweizerische Kommission für armierten Beton (Swiss Commission for Reinforced Concrete), founded in 1905, where both Pfleghard and Maillart were active. This whole epistemic environment was not the background but the very core of innovation. In order to perceive this network, a ‘democracy of sources’ had to be turned to. The sketches and the plans of architects and engineers were in fact studied by Korwan with the same rigour as the sketches by the client. A multi-perspective view on the processes is necessary in order to come closer to a complex historic reality. The case study of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium significantly adds to the rewriting of the history of architecture as epistemic history. Through this approach the present book challenges once more the idea that reinforced concrete construction was established and the subject of innovation mainly in great monuments such as Maillart’s bridges, Max Berg’s Jahrhunderthalle or later Auguste and Gustave Perret’s church in Le Raincy. Instead, the capillary diffusion of small- and middle-sized applications of reinforced concrete in buildings that are seemingly not outstanding at first glance, is in fact of at least equal importance. The Queen Alexandra Sanatorium is a wonderful and now much more well-known example of this.

40 Their design for the Schatzalp still appears to follow a traditional set of Kurhaus planning principles: pavilion-like projecting façades, the regular arrangement of windows, the division into pedestal, main floors and cornice, as well as the vertical segmentation using balustrades and aediculae – all with origins in neoclassical vocabulary. 10 However, this classicist exterior in essence acted as camouflage for a modern interior layout. The entrance was not located on an axis of symmetry, but rather eccentrically in one of the central pavilions. In contrast to the preliminary design, it did not lead the visitor to a vestibule, but to a narrow foyer where the view directly pointed towards the lift. Interior rooms were designed so that they could accommodate a variety of functions formerly located in separate rooms. Following the idea of the hall in the English country house, the hall in the Schatzalp is both a living room, a room a with a fireplace, a ballroom and a concert hall. The neoclassicist floorplan based on symmetry had been replaced by an order of functional organisation.11

This concept of combining multiple functions under one roof was also considered to be suitable for the organisation of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium. While the light wooden hut type12 that was frequently used in the United Kingdom provided a cheap and easy alternative, in this location the building of small wooden huts scattered across the site in which the patients were to spend the whole day was impracticable, in terms of both the spatial requirements and heating demands. A series of detached but massive buildings was also found to be unsuitable for the mountainous site. By contrast, the free-standing house was a proven model for a cold and alpine region.13

Pfleghard & Haefeli expressed their interest in the task and offered to produce a variety of sketches.14 Nevertheless, it would not be until early September 1904 before they were authorized to draft their first design.15 With the decision on the type having already been made and details regarding the site disposition communicated, the

10 Miller 1988, p. 53. Miller opens a most interesting perspective when he introduces the arts and crafts movements as a possible reference for the design. Rooms were no longer composed based on geometry but were formed based on their designated function and allocated accordingly.

11 Miller 1988, p. 53.

12 An example of this type is the sanatorium at Mundesley built in 1898/1899.

13 QAS 1910, p. 24. This debate is not present in the minutes of the local board which means it was probably only discussed in London.

14 The architects’ positive response was presented to the board at the following meeting, held on 25 August: Pfleghard & Haefeli were willing to undertake the work for a total of CHF 800, a sum that would not be charged if the work was eventually commissioned. SA/NPT/C/2/1, p. 155.

15 The brochure incorrectly states that “several of the best-known Swiss architects were invited to submit plans.” QAS 1910, p. 25. Although the choice for Pfleghard & Haefeli caused discussions and Buol even brought up the idea of a competition, it was decided that Pfleghard & Haefeli should submit a detailed statement on the exact content of their work. After responding to this request on 7 September 1904, they were authorized to draw up these first drafts. SA/NPT/C/2/1, p. 155.

relatively low, which facilitated cross ventilation. Given the number of rooms, the corridor with rooms on one side, and the avoidance of patient rooms on the ground floor,56 it was necessary to build higher than for a normal hospital, resulting in particular requirements for air circulation.57 Turban also specifically mentioned that loggias and verandas should be avoided as they had a negative impact on access to sun and air. In order to maximise the intake of these two environmental amenities, he instead conceived of the entire south-facing façade as a single window: movable glass walls that could be entirely removed58 made it possible to turn the patient’s entire room into a kind of loggia.59 This perception of the boundary between inside and outside that could not be fixed but was subject to permanent negotiation also rendered the balcony obsolete. Since the wings were entirely occupied by the patient rooms and corridors, Turban designated the entire central portion of the building as a servant space that contained the vertical circulation and the small bathrooms.

56 Because of the dangerous humidity caused by the park and the forest, no patient rooms were planned on the ground floor, as this would pose a danger to patients, especially at night when the humidity is at its highest. Turban 1903, p. 326.

57 Turban refers to the Wehrwald Sanatorium in Baden-Württemberg, which came under criticism because the lift shafts and stairwells of this multi-story building were considered to be distributors of bad air. Turban 1903, p. 326.

58 While they move towards the side walls in the patients’ rooms, they were to slide into the floor on the ground floor and disappear in the basement. Turban’s proposal was very detailed and not only gave exact details of the dimension, but also named the companies that would carry out the proposal. Turban 1903, p. 326.

59 Turban stated: “The room itself must be capable of being transformed into a loggia at any time, which is perfectly achieved through the construction indicated here.” Turban 1903, p. 326.

50 These spatial considerations were supplemented at the level of materials and construction; Turban called for solid construction without any gaps or cavities.60 This idea of impermeability was also relevant for all interior surfaces: these were all to be flat and washable.61 Edges and corners were also to be avoided through the use of fillets.

With these requirements three-dimensional ornament disappeared, replaced by a flat surface décor that led to an increased importance of colours.62

What is striking about Turban’s blueprint, apart from the factual and functional description of a building, is the degree of elaboration, where even specific companies are named for the execution of certain details. Not without reason, Quintus Miller argued that this proposal anticipated architectural developments that would occur decades later.63

ADAPTATION TO DAVOS

While Pfleghard & Haefeli were working on their design, they were able to rely heavily on Turban’s blueprint; yet they found themselves in an environment that allowed for much greater rationalisation. Unlike Turban’s ideal sanatorium, the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium was designed to be classless. This meant that the design was based on the repetition of only one type of room. This together with the omission of special rooms dedicated to upper-class patients allowed for circulation within the building to be greatly simplified.

Pfleghard & Haefeli’s initial proposal consisted of a central section that housed the day rooms and the main staircase, with two wings for the patient rooms each housing 40 beds, and a one-storey service annex where the kitchen was located.

DESIGNING AROUND THE HUMAN BEING

To understand Pfleghard & Haefeli’s design proposal it is necessary to recall the direction that these architects had followed with their design of the Schatzalp, where the functional configuration began to liberate itself from the traditional rules of architectural composition. In the

60 Interestingly, Turban did not see how reinforced concrete could have contributed to this approach, but proposed a ceiling of iron girders with gypsum blocks from the Gussbausteinfabrik Zürich, where the gap between the stone and the iron eventually filled with gypsum. Turban 1903, p. 338

61 Turban proposed having walls, ceilings, doors and windows painted with Ripolin, a porcelain-like glossy paint that is resistant to disinfectants and available in a variety of colours. Turban 1903, pp. 339 –340.

62 Turban uses the term Flächendekoration (surface decoration) see: Turban 1903, p. 341.

63 “Fighting the disease with its causes became the determining element and thus the defining factor of the architecture. It anticipated its time by thirty years through its consistency in implementation.” Miller 1988, p. 52.

Floorplan of the Schatzalp’s second floor with patient rooms.

Floorplan of Turban’s ideal Sanatorium with patient rooms.

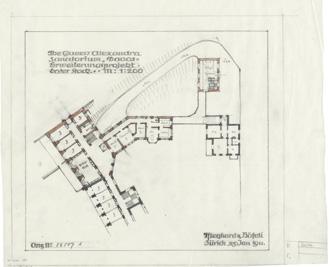

Floorplan of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium 1905 with patient rooms.

52 case of the preliminary design for the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium, they went one step further. This design no longer acts as a volume that was subsequently filled with content. Instead, the entire project was based on the definition of the patient’s room as the nucleus of the design, which would subsequently determine the dimensions and appearance of the whole building.

For each individual, the proposal foresaw a south-facing volume of approximately 3 m in width, 5 m in depth and 3.1 m in height.64 A 1.5 m65 deep balcony across the entire width of the room reached out into the outside world and enabled a connection with the environment, while at the same time maintaining an isolationist approach to this minimal space where one would breathe fresh air but not encounter any other people. The idea of a buffer zone was repeated on the north side: access to the patient rooms was provided via a small private anteroom with two wardrobes.66 The sanatorium had successfully adapted the minimal space of a monk’s cell and transferred it to a medical context. Technically, the patient’s room has to be regarded as one part of a sequence of rooms that penetrates the building mass from south to north, thereby allowing for nearly perfect cross ventilation: air could enter through the balconies, pass through the patient’s room and small anteroom, flow from the private core to the public corridor and finally exit the building through windows in the north façade. Eleven of these patient room nuclei were then lined up next to each other, defining the length of a wing. This type of layout led to identical plans for the first and second floors.67 Long, naturally lit68 corridors facing the north façade were to connect the central portion with a small, naturally lit space at the end of the corridor.

Due to the focus on the patient rooms, the associated corridors and the central pavilion,69 the main volume within this concept lacked space for the necessary service rooms. Therefore, the symmetrical figure was sacrificed through the addition of north-facing service annexes. While these were connected to the building, they followed their own logic and rhythm and had their own circulation system.

64 Coming from the previous situation in the Davos invalid’s room where double rooms were used which was highly disliked by Buol and Vesey the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium was to have only individual rooms. SA/NPT/C/2/1, p. 101.

65 The balconies were larger in the two middle rooms of each wing. The balconies in the pavilion were also different, as they are deep loggias with a completely different daylight situation.

66 In some cases, one closet had to sacrificed for the sake of a shaft. Also, the outermost rooms had a different access.

67 See: #24869 GTA 30-0636.

68 In the wings, the corridor was lit and ventilated through three north-facing windows, one of which was connected to a small seating niche. In the pavilion, the opening to the north façade was sacrificed for an extension of the volume that contains three bedrooms for staff and visitors.

69 In this central joint was a spacious staircase, naturally lit by three windows on the north façade. Visitors used this to reach the respective floors on foot or by lift. The distributive function is performed by a vestibule with rounded corners, which mediates between the two wings and a dayroom.

53 THE LOGGIA AND THE DISSOLUTION OF THE FAÇADE

Following the concept of the nucleus, the width of the patient room not only defined the dimension but also the rhythm of the building. Although the composition was heavily influenced by this new focus, this did not mean that traditional principles were obliterated: the introduction of a central tower and the articulation of two end pavilions established a symmetric rhythm.70

Despite the comparatively traditional aesthetic appearance of the main façade, the sanatorium represents a significant evolution, especially in comparison to the Schatzalp: when Pfleghard & Haefeli designed this earlier sanatorium the private balcony was a mandatory element, unlike at the later Queen Alexandra Sanatorium. Consequently, the aesthetic approach to the Schatzalp design was not focused on this issue and the building was developed with a regularly fenestrated façade, with a balcony or a terrace as secondary structures attached as required.

By contrast, the design of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium exploited the functional requirement for private loggias as an architectural device. The architects negated the concept of the fenestrated façade by setting back the thermal envelope, leaving the slabs of the balcony and the balustrades as the defining elements that introduced a horizontality into the building hitherto unknown. The balcony, and thus the nucleus, had become the defining aesthetic element, visually representing the significance of the patient’s room and human well-being. The relevance of these nuclei was further emphasised by the way the ground floor was designed.71 There, the visual presence of the individual room receded into the background. Instead, on the ground floor façade the rubble stone created a unifying and homogenising textural effect, which ran the entire length of the zone. Differences in the fenestration72 only become visible at second glance. The plinth with its uniform texture dominated the overall impression. Three vertical elements that rise from the base appear to support a cantilevered roof while framing the patient rooms.73

The integration of a central pavilion and two end pavilions may have been the right decision from a compositional point of view. However, this caused the patient rooms in the end pavilions to have significantly inferior daylight exposure. The architects’ roots in neoclassical compositional principles prevailed over fidelity to the new concept.

70 In the roof, this 3-8-2-8-3 rhythm of the building continues in suspended beams. However, the plans are not coherent. While in the perspective only the tower and the pavilions show these elements, the elevation shows them throughout the whole building.

71 The height of this plinth oscillates between 1.5 storeys (west pavilion), 1 storey (wings), 2.5 storeys (tower) and 1 storey (east pavilion). Interestingly, this plinth zone does not extend to the basement.

72 In the plinth zone, the predominant window format is in vertical format with visible arches. Three landscape windows in the east wing are an exception.

73 Here the image competes with reality, as the pavilions also house patient rooms.

55

TAMING THE MOUNTAIN: TOPOGRAPHY AND ARCHITECTURAL FORM

Pfleghard & Haefeli proposed that the sanatorium be located at the northeast edge of the property, in direct proximity to the existing Villa Baltia. Access was provided both via the new serpentine road that led directly to the entrance of the sanatorium and via a smaller road that branched off to the rear of the building. In tandem with the southern orientation of the main façade, this location was intended to guarantee both a maximum of solar exposure and an unobstructed view. At the same time, this meant that the sanatorium design had to deal with the steepest and thus most problematic area of the site. Being positioned almost perpendicular to the slope, the building had to negotiate a height difference of a total of 15 m74, whereby the topography became an essential part of the design.

Pfleghard & Haefeli proposed a system of terraces and retaining walls both underneath the building and in its immediate surroundings. This approach was intended to transform the once subtle natural topography into three main terraces with additional smaller plateaus beyond. This negotiation between different levels of topography was not limited to the long section, but could also be found in the short section, where it allowed the basement to function as a ground floor.

THE INCONGRUENCE OF FORM AND FUNCTION

Repeating a design technique that Pfleghard & Haefeli had already used in the Schatzalp, the main entrance was not located in the central portion of the building, where one would have expected it to be. Instead, one would enter the building in the west wing, where a covered hall with a vaulted ceiling provided access to either the west wing,75 the main building or a courtyard at the rear of the building. The entry level also provided direct access to a large terrace that extended across the entire east wing. Via a vestibule, visitors entered the main hall of the central portion of the building, which primarily housed a monumental staircase, with the lift located on the central axis of the building.

On the ground floor level of the east wing, a drawing room extended over six bays, leading to the dining room at the end of the building. This dining room serves as testimony to the ongoing conflict between function and form that Pfleghard & Haefeli had so clearly resolved in the

74 While the terrain under the western part was very steep (height difference of 10 m), it was flattened under the central part (height difference of 5 m). A possible extension to the west, which was already indicated in the view, would have caused a further difference in height of 12 m.

75 This west wing contained a chapel, two cellars at the end of the building, two smaller undefined rooms and a service staircase to connect the wing with both the basement and the upper floors.

88 30 beds would save £4,000, the later expansion to 58 beds would cost £6,400, which would exceed the budget by far.35

This short ‘co-designer’ episode did not have any direct impact in the end. In contrast to previous debates, this time the proposal was countered with professional facts. Whereas the co-designers had managed to heavily influence the design stage, construction-related matters remained within the hands of the professionals for the time being.

FROM THE WINDOW IN THE WALL TOWARDS THE WALL AS WINDOW

As a complement to the floorplans, three building section drawings were created in February, which continued the previously introduced method of visually distinguishing the materiality.36 The horizontal elements constructed of reinforced concrete were drawn in black. In combination with the colour scheme for the vertical elements of quarry stone (red) and the foundations (yellow), this ensured that the drawings managed to communicate a visual hierarchy emphasising the importance of the horizontal elements. Interestingly, none of these sections conveys the spatial concept of the relatively thin building mass composed of patient rooms and adjoining corridor that allowed for optimal cross-ventilation. Instead, the emphasis was placed on the functional, north-facing spine.

Despite the limitation of the use of reinforced concrete to the horizontal elements, it is reasonable to refer to the building section from the balcony to the corridor as skeleton construction. Horizontal reinforced concrete slabs acting as T-beams rest on the vertical load-bearing columns made from quarried stone. The exact position of the T-beam joists followed the grid of the patient rooms. As a result, these joists merge seamlessly into the non-load-bearing partition walls between the rooms. This in turn created the impression of a completely flat ceiling on the upper floors. The patient rooms appeared as a space between two horizontal planes.

35 SA/NPT/C/2/2, pp. 194–196. The issue of size, which had been recurring for years, was to remain with the project until April. 3.5 years after the question first arose, and at a time when construction was already underway, Vesey addressed it in a letter on 2 April 1907, acknowledging both the size and the need for completion of the building. Nevertheless, he left open the question of whether all the rooms should be furnished immediately. SA/NPT/C/2/3, p. 13.

36 Plan #38010, GTA 30-0636, drawn on 1 February 1907. Compared to the first section drawn in June 1906 (#33473, GTA 30-0636), the room heights remain the same. At the same time, the lintels on both the ground floor and the first floor are now made entirely of concrete (instead of the previous mix of materials) and the concrete materials were given a more articulated form.

Following this construction principle, there is neither a lintel nor a threshold. Hence, the usual structural indication of the separation of inside and outside is absent in the section.37 The room boundaries could theoretically be defined as desired. Yet this flexible boundary arrangement required a fresh approach to the subject of the façade.

After having created copies of the existing elevation drawings,38 Pfleghard & Haefeli shifted their attention away from the overall plans towards the details. Four drawings at a scale of 1:20 showing a large number of exterior windows and doors 39, revealing an increasing preoccupation with architectural details. Here, the solution for the patient rooms is of particular interest. Unlike in traditional brick construction, the window was no longer an element that had to be fitted into a load-bearing wall, where it had to respect the rules of the latter. It had evolved from being an opening in a wall towards being a wall defined by the elements of frame, door and window. This wood-framed element, consisting of casement windows with a wooden sill and a double- leaf

37 In plan, the wide brick column provides an indication of the position of the boundary.

38 These are east view #38298, StATG 9’11, 5.0.0.5/1, north view #39391, StATG 9’11, 5.0.0.5/2 and south view #39392, StATG 9’11, 5.0.0.5/0.

These new plans are date-stamped 16 April 1907 and contain handwritten English translations. They were in the archives of the sanatorium building, so it can be assumed that they were intended for the local board.

39 Plan #39564, GTA 30-0636, from 22 April 1907 shows metalwork for

windows.

114 The planning did not foresee any vertical concrete elements from the second floor onwards. This left the first floor and the ground floor as the only relevant areas, in terms of concrete usage. It is here where we can find two different ways of handling the concrete elements. Locations like the rear wall of the building and the columns in the drawing room required structural reinforcing elements that were formally perceived as traditional walls. In these cases, only parts of the wall were upgraded with reinforced concrete without any visual consequence. The situation was different in those locations where concrete elements filled a gap in the structural system. Both the column in the entrance hall and two columns in the dining room are examples where the new material directly translated into a shape – the round column – that is not found anywhere else. Following this pattern, the columns that allowed for the flexible open space in the kitchen also received an upgrade: while they were originally been planned to be U-shaped steel beams that were then to be filled with concrete, they were now made of reinforced concrete.109

A STORY OF TWO ROOFS

In October, progress on the construction site called for more explicit directions as to how to handle the roof. In a series of detailed 1:10 drawings labelled Schnitte durch das Hauptgesims (sections through the principal cornice), 110 Pfleghard & Haefeli provided two sections and one elevation that serve as yet more evidence of the ongoing and ambivalent search for an application of reinforced concrete as a new material. Due to the higher loads and the larger cantilever, the ceiling above the topmost floor was subjected to greater stress, making it impossible to apply the elegant cantilevered flat slab that had become characteristic of the patient rooms on the floors below. Here, the beams instead penetrated the building envelope and became the visible bearing elements of the flat roof slab. At this point, structural and functional requirements appear to have collided with the interior requirements of the nucleus of the patient room, leading to one of the rare moments in the building where the space-defining quality of concrete as applied so dynamically on the lower floors had to be sacrificed. Pfleghard & Haefeli planned a secondary suspended wooden ceiling that served as the upper boundary of the patient room nuclei. In doing so, a cavity was created above the patient rooms on this floor, which helped to mitigate the heat flow and thus reduce the heating demand of the building, while

109 See: DIAG #761 where they are introduced as elements made in planed shuttering (gehobelter Schalung) and were thus prepared to be exposed.

110 See: #43634, GTA 30-0636, which was produced on 3 October 1907.

115 at the same time preventing the insulating snow on the roof from melting. However, this measure concealed the concrete ceiling, thus negating the unity of structural element and space-creating element. In this way, here the nucleus was conceptually freed from the supporting concrete shelf.

This conventional approach, in which reinforced concrete was only treated as a structural element without a direct and transparent visual representation in the appearance of the building, is also found in the cornice. The massive cantilevered element consisting of beams, slab and attic was entirely hidden behind a stucco cavetto moulding formed from ‘Rabitz’111 metal lathing and undulating wooden ornamental trim with oval elements of galvanised zinc.

While these functionally and conceptually justifiable decisions resulted in this kind of dishonest material and spatial expression, they nevertheless strengthened the overall visual idea conveyed by the façade. Structural honesty would have called for the cantilevered beams to be exposed, which in turn would have disturbed the concept of the façade through the added rhythm of the beams. Instead, the cavetto turned the whole cornice into a continuous massive horizontal element that reads as a more substantial version of the repetitive horizontal lines caused by the slabs of the lower floors. It also appears to be carrying an ultralight, dark roof: the ornamental trim, with its darker colour as well as different material and texture, forms a thin horizontal cap. A roof designed to meet structural requirements was concealed behind a secondary roof, which transformed this engineered product into an element suitable to the overall architectural composition.

156 By the end of January 1911, Pfleghard & Haefeli had worked out two alternative solutions for the extension.22 While both proposals reduced the extension of the main building from ten to only six bays, the location of the new medical area and the facilities for the laundry differed between them.

The first version proposed a new independent volume. Following the angles of the two defining volumes, the sanatorium and the villa, it would have accommodated both functions (washing/drying in the basement, medical section on the upper floor) and would have been connected to both the villa and the sanatorium through a covered walkway.

In contrast, the second version proposed that the medical area (as well as the future chapel) be directly connected to the sanatorium extension. This was to be achieved by having a volume extend perpendicularly from the building extension that was bent in the direction of the villa. Washing and ironing rooms were to be housed in a separate building.

A few days later, this second version was updated and formally simplified:23 the separate volume for washing/ironing had been omitted. Most importantly, the medical area was liberated from the bent section and transformed into a wider and longer, simple rectangular shape. Rather than trying to mediate between the villa and the sanatorium, this volume had its own identity.24 In addition, this proposal swapped the chapel with the medical area so that the chapel was on the first floor and the medical area on the second, thereby allowing for an improved connection to the patient rooms of the existing building.

Pfleghard & Haefeli also produced a section drawing and a rear elevation, illustrating the complexity of the site around of the extension and in particular the medical area. On 4 February, three further floorplans were drawn up for the ground floor and the top floors, three and four; an elevation was also included, thus completing the extension design.25

Compared to the last elevation from June 1910, this latest design was not only much smaller, but also more rational, since it omitted the arches in the upper balconies. In addition, the existing hierarchy was retained, with the central section remaining the main element.

On 11 February 1911, an initial set of plans was sent to Davos, where it was discussed at length in the finance committee. The necessary substantial changes were explained in person by the secretary at a

22 Several plans were drawn on 25 January for both version 1 (#85007a and #85007c ) and version 2 (#85007, #85007b and #85007d). All plans: GTA 30-0636.

23 On 31 January they produced and updated version 2 in section (#83467) and plan (#83465 and 83464). All plans: GTA 30-0636.

24 The covered passageway from the the villa does not seem to fit properly to the volume that now clearly belongs to the sanatorium.

25 See plans #83463, #83466, and #83468. All plans: GTA 30-0636.

Initial proposal for the extension, 25 January 1911.

Alternative proposal for the extension, 25 January 1911.

179 between patient rooms and the corridor. 78 Since this was the modern part of the building, it was only logical that it should also receive a more modern detail.

Pfleghard & Haefeli covered the concrete slab with a layer of plaster screed. Through a modification of the thickness of this layer, it was possible to establish a small height difference of just over 1 cm, which served as a minimal threshold. Not only did this allow for the beds to be easily manoeuvred, it also meant that the room could be mopped without water getting into the corridor.

With the use of a Schoch Anschlagseisen (an iron element normally used as a rabbet)79 they continued with a strategy they had initially used in May 1909,80 which now reached a new level through the appropriation of an industrial element for an architectural detail. Pfleghard & Haefeli selected an industrially manufactured readymade from a catalogue on the basis of its shape, while ignoring its original intended function. ‘Schoch 3517’ was a small streamlined part that could be found in the Fenstereisen (iron parts for windows) section of the Schoch Modellkatalog (model catalogue). However, they saw how it could potentially be used on two different levels,81 while adhering to their overall design philosophy of avoiding edges. Since the thickness of this element corresponded to that of a layer of linoleum, it allowed Pfleghard & Haefeli to create a modern, high-precision detail.

ON THE TRAIL OF MAILLART: FRIEDRICH PULFER

In February 1912, yet another new actor entered the project. The engineer Fritz Pulfer from Bern produced plans for the reinforced concrete work.82 This is remarkable in that in June of the previous year Morel & Cie. had already produced plans for the ceilings. Pulfer is largely forgotten today, which is quite remarkable given his impressive œuvre.83 One outstanding project that demonstrates his expertise in the field of reinforced concrete is his collaboration with Otto Salvisberg for the

78 Plan #89760, GTA 30-0636, from 14 February.

79 Schoch 1899, p. 109.

80 During the construction of the original building Pfleghard & Haefeli had used a Schoch-part for the stairs, see chapter 3.

81 As a matter of fact, the part’s dimensions define the possible height of the threshold.

82 Insa 1982, p. 347 mistakenly attributes the entire ferro-concrete system of the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium to Pulfer, ignoring the fact that Pulfer did not participate during the construction of the original building.

83 Among others, Pulfer worked on a new school building in Rheineck (1905), the buildings of the Settelen company in Basel (1906), the St. Karlibrücke bridge in Lucerne (1907), the new building for the Milchgeschäft des all. Konsumvereins Basel (1909) and a staircase in the Messtation Wiel of the Elektrizitätswerk Kubel (1910). Also mentioned are the roof of the Les Avants-Sonloup Furnicular railway (1911) and ceilings for the Heymann country house in Langenthal (1913), furthermore the municipal hospital in Baden and the Hochgebirgsklinik in Davos Wolfgang (1925)

Copy editing: David Haney

Project management: Freya Mohr, Baharak Tajbakhsh

Production: Anja Haering

Layout, cover design and typesetting: Floyd E. Schulze

Typeface: Trainer Grotesk, Antoine Elsensohn

Paper: Munken Print White 1.5, 90 g/m²

Printing: F&W Druck- und Mediencenter GmbH, Kienberg

Image Editing: Repromayer GmbH, Reutlingen

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023931741

Bibliographic information published by the German National Library

The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in other ways, and storage in databases. For any kind of use, permission of the copyright owner must be obtained.

ISBN 978-3-0356-2671-1

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-0356-2672-8

© 2023 Birkhäuser Verlag GmbH, Basel

P.O. Box 44, 4009 Basel, Switzerland

Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston