6 minute read

MODELLING FOR LEARNERS

HOW MODELLING CAN SUPPORT LEARNERS

Josh Crossman explains the modelling approach: by demonstrating a new concept, teachers can both support their learners and develop their own understanding of the key skills and materials being introduced

Advertisement

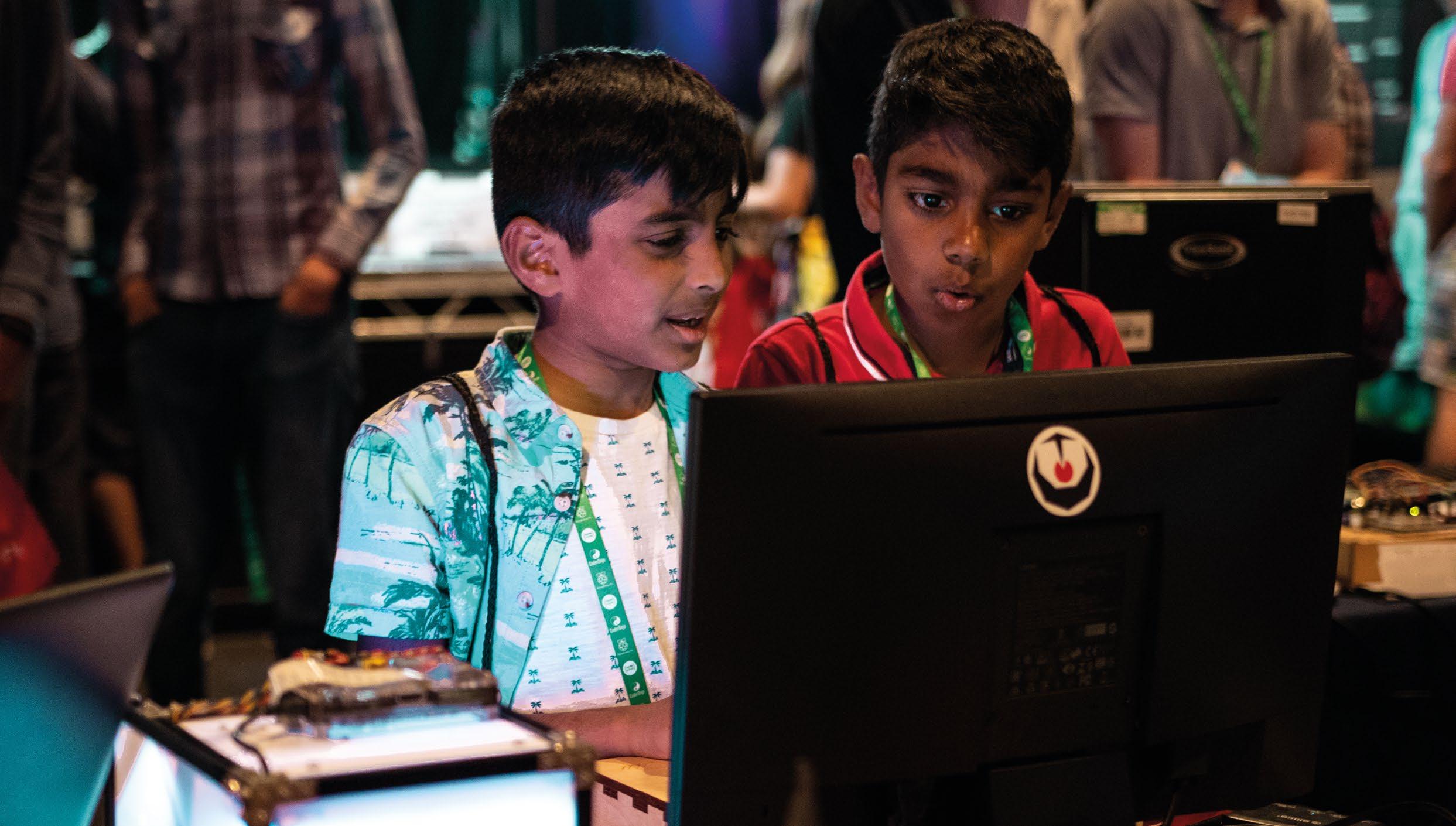

When giving learners the opportunity to use new skills or software, it is important to show them how first. Teachers can demonstrate a new concept by using a recorded video, or by modelling it for the learners. Modelling is an instructional teaching strategy in which a teacher demonstrates a new skill or approach to learning. Teachers first model the task or skill for learners, and then learners begin the task and work through it at their own pace.

Schools use modelling across various disciplines, such as writing, handwriting, mathematical strategies, and science experiments. It’s a powerful strategy that can be used across many different subjects, and computing is no different.

As we have been developing units for the Teach Computing Curriculum (TCC) (helloworld.cc/tcc), we have reflected on the tried and tested techniques that help make computing lessons a success. In this article, I will share some of our top tips for modelling.

Improved confidence

Perhaps the biggest benefit of modelling is the confidence and competence that teachers gain from using the software. In the TCC Year 6 (ages 10 to 11) ‘3D modelling’ unit, learners are shown how to create a 3D shape and change the viewing angle in the 3D modelling software Tinkercad (helloworld.cc/3Dmodelling). Teachers who are new to 3D modelling may not have come across changing the viewing angle before.

Through prelesson preparation, and of course, through using the software when modelling, teachers may encounter misconceptions, errors, and perhaps shortcuts that the learners might make in their own use. For example, in Tinkercad, teachers can click on the viewing cube to jump to different views. As their own confidence improves, supporting the learners with their errors or misconceptions will become easier.

Credit: stock.adobe.com/insta_photos

Thinking aloud

If teachers provide a monologue — or think aloud — as they model, learners get the opportunity to observe expert thinking that they wouldn’t usually have access to. It allows learners to follow more closely what the teacher is doing and why they are doing it. More precisely, it can reduce the extra cognitive load of having to deconstruct each step for themselves (see page 20 for more about cognitive load theory).

As teachers know their own learners best, they can tailor the language they use when modelling, to make it as beneficial as possible for their particular learners. This ensures that teachers can meet their learners’ needs in a more targeted way.

Greater freedom

Questioning is a key part of modelling — this includes both the teacher’s questioning of their learners to draw out understanding, and the learners’ questioning of the skills and processes the teacher is using. Modelling can enable teachers to give context to their answers to the questions, ensuring they are able to show alongside the tell. This will help to make their answers more visual and concrete.

Additionally, the freedom of modelling ensures that teachers are able to meet

n Modelling can improve teachers’ confidence in using unfamiliar software

the needs of all the learners in the room. This could mean revising an area that wasn’t fully understood by some, or perhaps moving at a slower or quicker pace, depending on the learners’ level of understanding. For example, in lesson one of the ‘3D modelling’ unit of the TCC, teachers could break up the content in the video into smaller chunks, perhaps allowing the learners to get to grips with the viewing angle before introducing the zoom buttons.

Impromptu learning

In line with the benefit of greater freedom discussed previously, modelling also allows for more impromptu learning. As students ask questions, teachers may need to explore different areas of the software, or be challenged by questions about a skill they hadn’t previously thought about. Using the freedom provided by modelling can lead to a deeper level of understanding. Equally, it can reinforce the skills used in previous lessons, giving learners the chance to consolidate their learning as they progress to the next stage.

As teachers narrate their modelling, it can also bring to the forefront things they do instinctively. Learners can pick up on these things, such as keyboard shortcuts (copy, paste, and duplicate come to mind) that teachers might use naturally. We do these things all the time when using new software or learning new things, but we might not always use the opportunity to share them. Modelling can also lead to exploration of a skill that might benefit learners, but wasn’t originally planned for the lesson.

Making mistakes

By demonstrating computing experiences live with their learners, teachers can encourage the sharing of mistakes, both intentional and unintentional. Making and demonstrating mistakes is OK — in fact, it should be celebrated! Allowing learners to see that their teachers aren’t immune to making mistakes can be encouraging for less confident learners and help them to build resilience. More importantly, it enables learners to see how to respond to mistakes, particularly when combined with the thinking aloud approach mentioned previously. This can be a powerful tool for encouraging perseverance.

By sharing mistakes and thinking aloud, teachers can guide their learners through strategies to overcome a range of obstacles. Use phrases such as: “When I first looked at this problem, I didn’t know where to start”, or, “It’s OK to feel frustrated at this point; I often do.”

Video demonstrations vs live modelling

As well as live modelling, there is the option of demonstrating software using prerecorded videos. This means that you can show the video to learners and they can follow along and learn the skills you need them to know. However, many of the benefits to modelling, such as impromptu learning and improved confidence, will not be gained in this way.

Recorded video definitely has a place in the classroom — particularly in the context of the pandemic — but modelling these skills yourself, making mistakes, and developing ideas as you go are invaluable ways to share learning experiences. If you do show your learners videos instead of using live modelling, here are some tips for including the modelling approaches:

n Watch the video before the lesson and practise the thinking aloud approach n Share the video with learners and think aloud as the video is shown; allow the learners to attempt the task before asking them to share their own modelling of it n Punctuate the video with your own questions, and don’t be afraid to pause to answer questions posed by the learners

Throughout our work on the TCC, my colleagues and I recorded videos that could be used to model key skills. Our aim was to ensure that the content was as accessible as possible for the full range of teachers who may use it.

Though live modelling may take longer than displaying a prerecorded video, it is a great way to share the learning experience. In my view, it has many benefits over the more passive prerecorded approach. Hopefully, many teachers will watch these videos and gain the confidence to give modelling a try.

Modelling is a journey, and teachers inevitably won’t get it right every time — but sharing that experience with the learners may turn out to be the most powerful part of the exercise.

JOSH CROSSMAN

Josh is a programme coordinator at the Raspberry Pi Foundation, working across programmes such as the Teach Computing Curriculum and Hello World. He is a Raspberry Pi Certified Educator and a former primary teacher.