9 minute read

The next phase of AVoIP

Matrox shows its first AVoIP products at InfoComm 2012

Samuel Recine, sales director at Matrox, discusses interoperability, brand competition and a brave new AV world with open standards

The AV market has been streaming video for many years. The entire video telepresence market, for example, was based entirely on finely tuned, high-quality video in optimised low bitrates.

Even though streaming video and audio-over-IP was in heavy use for large facility and multi-site applications, it wasn’t until around 2010 that first-movers in the AV industry began to speak about replacing core onsite AV infrastructure from baseband analogue and digital audio/video extension and switching with an AV backbone that functioned entirely over IP as well.

As with any disruptive changes, many leading incumbents in the market resisted the notion. Selling proprietary switches was far too lucrative. So, for several more years, the market was treated to public discussions about the resolutions, quality, latency and other performance characteristics that could or could not be achieved over IP.

But customers had eyes and ears and could see for themselves that it was clearly possible to achieve the same level of content quality and performance using IP instead of hardwired baseband technology such as VGA in analogue or HDMI and HDBaseT in digital. Before long, every major AV manufacturer had launched some products that could support AV extension and switching over standard IP.

Corporate, government, military, medical and other end users were also simultaneously experiencing advances from the IT world and using everything from Netflix for entertainment; to YouTube and Facebook for training and marketing; to Skype and Zoom for collaboration and corporate communications; and to video management systems like Panopto, Kaltura and Brightcove to build, maintain and deliver both live and ondemand, user-originated content.

The end users were exposed first-hand to the billions upon billions of dollars that had poured into R&D budgets from the IT world to advance things such as audio and video encoding and decoding and codecs for compression. The amazing progress in both real-time and on-demand video delivery over bandwidth-constrained environments revealed to users the inevitable convergence of their data, communications and performance AV applications over a common communications protocol.

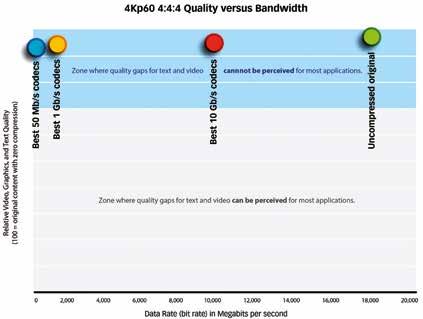

Illustration of quality versus bandwidth

While ‘quality’ has both mathematical and objective measurements as well as subjective elements, one thing the market could clearly benchmark was ‘bandwidth’. The resulting comparison of quality versus bitrate is a matter of fierce debate and can vary by user and by application. But, across a spectrum of users and applications, the graph above shows that for a significant majority of AV applications, the best codecs from all bitrate levels can produce quality levels well above the target zone for text and video quality, and acuity.

Because of the exceedingly low differentiation available over quality versus bit rate, the next argument that surfaced was to slice and dice ‘latency’ again in zones of performance that exceeded customer needs for most applications.

When the source and the destination are in the same field of view, such as a performer onstage standing in front of a jumbo videowall, there is some room for debate about the perceivable threshold such as one frame of latency – ‘glass-to-glass’ – that is, from camera lens transported and displayed on the screen. But, here again, the vast majority of AV applications are not like that. So, what is the acceptable metric for latency?

IP-KVM is a good example. Having the PC several kilometres from the keyboard, monitors, mouse and audio speakers is an application that adequately tests if users can feel the separation when using their favourite applications. This

is an application that demonstrates that some users are comfortable at 100ms. Almost 100% of users do not feel the latency at 50ms. So, the amazing, better, best-latency story over IP also died off sometime in early to mid-2018.

And so by ISE 2019 and InfoComm 2019 in Orlando, you could see that just about every manufacturer had product lines or entirely migrated portfolios of products to support highperformance audio/video extension and switching applications over standard IP. In fact, many companies had granularities of uncompressed-over-IP, lightly-compressed-over-IP and highlycompressed-over-IP products in order to give customers choice for their applications.

Uncompressed and lightly compressed AVoIP products tend to use less processing power (so cheaper chips) and therefore tend to have lower selling prices.

When environments require a high density of endpoints and wireless is in play and data, communications or AV are being mixed and leveraged together, when the distances for AV applications are very large, or when the AV needs to traverse portions of network that have potential bandwidth bottlenecks – which is especially common when leveraging cloud or public internet – the products supporting maximum performance at very reduced bit rates are at the fore.

Regardless of the quality, latency or other performance requirements of an application, the market is already serving AVoIP solutions for every application and the market is unquestionably migrating from baseband to IP. So, what comes next?

As the industry’s knowledge of the impact and usefulness of IP-based AV matures, the second wave will clearly centre on open standards, interoperable ecosystems across competing brands and value pushed away from individual widgets and onto technologies and services that create useful interoperable environments that fully leverage the converged world of data, communications and performance media over IP. This breaks down into two topics: open standards and interoperability.

Open standards

This topic refers to the long-term viability of proprietary technologies, whether that means proprietary uncompressed encoding techniques, proprietary codecs or proprietary transport and communications protocols. As markets such as 2D/3D graphics, live two-way communications and so forth have shown, no proprietary technology controlled by a single vendor has long-term sustainability. There are too many stakeholders that have different technological and commercial dependencies for this to ever be viable.

2019 saw the first major discussions in the AV market about potential long-term open standards that can guide the development of technology and products to assure the needs of the maximum number of products, services and user stakeholders are met.

While the discussion has only really begun amidst shipping products, some of which are based entirely on open standards and others based on proprietary technologies, at least some viable alternatives were laid down for the first time last year.

For example, AIMS started a Pro AV Working Group to engage with the community of end users, manufacturers, systems integrators, application developers and service providers to establish if the open high-performance media standards recently adopted by the live broadcast industry could be enhanced and adapted for open standards and interoperability in AV. The group of standards being presented by AIMS is encapsulated by the larger standard known as SMPTE 2110. This consists of multiple sub-standards to regulate encoding, video parameters, audio parameters, asset discovery on networks and security.

2020 will likely see the lively discussion about what existing, enhanced version of existing or entirely new standards will serve the needs of the industry for the next decade.

SMPTE 2110 already has provisions for low bandwidth environments all the way up to 25Gb/s (widely expected to be the next super node), 40Gb/s, 100Gb/s and beyond. This satisfies the most enhanced use cases for 4K, 8K and onwards. So, again, open standards deal with engaging the long-term requirements of all the stakeholders and is mainly about making investment decisions into things that have a viable future.

Interoperability

Open standards just ensure that the core technology itself is supportable and continues to evolve with the necessary ingredients to meet the requirements of the market over the long term.

Interoperability deals with hardware and software products playing nicely together. Some products in the market work with other brands. Sometimes this even includes competing brands. For example, an IP camera produces a standard H.264 stream. The codec and streaming protocols are based on open standards. But then, if the camera vendor only wants their own decoders to be able to decode and display the camera, this device cannot participate easily in ecosystems of products using third-party decoder software running on PCs, decoder appliances or IP videowalls. Or, if the camera has been developed so that it can be integrated into an ecosystem to maximise its usefulness, then it can work with the aforementioned software and hardware products. Interoperability is ultimately a manufacturer’s choice. Sometimes products are locked down to only work within one brand’s product line. Perhaps the manufacturer is taking responsibility for product interoperability within its family and causes restrictions to reduce its scope of quality assurance testing, technical support and warranty support. But these exclusions come at a price.

When customers want to use the best encoder from vendor A or the top videowall from vendor B, and the leading recording

Matrox’s Samuel Recine

and video management system from vendor C, they are precluded from doing so by products that are locked down and blocked from working with each other intentionally.

Multi-vendor/cross-brand/cross-product interoperability is therefore a step above products based on open standards. You cannot build interoperability without open standards. But you can have products that are based on open standards that are not enabled to be interoperable.

Many customers in AV express their goals in plain terms: ‘I want the kind of performance and interoperability I had with VGA in analogue and HDMI in digital. But I want to take advantage of IP to remove the barriers to the number or types of devices of my ecosystems and barriers to distances of the devices on my ecosystems.’

This level of both open standards and interoperability is what the live broadcast industry is shooting for with SMPTE 2110. This is in part possible because the end customers in broadcast are very large and hold considerable sway over manufacturers. In the long-run, it seems inevitable that the AV world will need to adopt a significant amount of interoperability to engage the maximum usefulness of AVoIP to end users. It’s the customers themselves that will demand this.

But it’s not immediately the case in the AV industry. AVoIP is de-facto accepted as the way to go. But interoperability is still in its starting stages in AV.

Manufacturing resistance is one barrier. Skills in the integration, installation and services channels to create interoperable ecosystems over IP is another. Improving cooperation and collaboration between AV stake owners and IT stake owners is another piece that must evolve in tandem.

In the end, imagine what it would be like to have emails that only work from one brand to itself. The market would simply not stand for that synthetic limitation. But maximum usefulness will not be achieved in AVoIP in one bite. This ecosystem needs to be built by customers, channels and manufacturers.

Ironically, it’s the resistance by some key players to help advance interoperability that has large corporate and government end users looking at alternatives for their workflows and applications. I don’t think AV companies quite realise just how much software and hardware companies rooted in the IT world are coming on strong with useful products for a myriad of AV applications.

Instead of merely competing with each other, I expect AV manufacturers are going to continue to let in other products and schools of thought until they put aside their differences and work towards common goals that help advance the industry and give end users the utility they are paying for.