Aurora Play and Practice: Connecting play and language in our bilingual setting

2024

Our Vision

Aurora School is an inclusive Centre of Excellence in the education of young children, specifically for DEAF, HARD OF HEARING AND DEAFBLIND childrenenabling them to develop competent language and communication skills.

Our Mission

To immerse children and their family in a language-rich bilingual and bicultural community (Auslan and English) where children have the opportunity to thrive, learn and achieve their full potential. Community Curiosity Perseverance Respect

We would like to thank the Wurundjeri People for sharing their land.

We promise to look after it, the animals and people too.

Hello Land, Hello Sky, Hello Me, Hello Friends.

Table of contents SECTION ONE Background 4 8 SECTION TWO Language and communication 22 SECTION THREE Play 72 SECTION FIVE Action research 80 SECTION SIX Working with colleagues 90 SECTION SEVEN Resources 46 SECTION FOUR Supporting a play-based approach: The learning environment

SECTION ONE

1

Background

Teachers deliberating practice: The Aurora school project

This project was a collaboration between Deakin University researchers, Professor Andrea Nolan, Professor Louise Paatsch and Dr Natalie Robertson, and the principal, leaders and staff of the Aurora School. The project aimed to establish a research culture that supports knowledge building through evidence that leads to practicechange relating to play-based pedagogy to support the communication and language development of the children at the Aurora School.

The project explored the impact of the research design and methodology including the Critical Participatory Action Research approach – (CPAR), in supporting change in teachers’, educators’, support staff, and allied health professionals’ practice and empower them to confidently research their own practice, thus creating a self-sustaining model of capacity building. The project focused on supporting teachers and professionals at Aurora School to embed a play-based learning and teaching approach to support young deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) children’s communication and language. Changes to practice and child outcomes were captured as indicators of the effectiveness of the CPAR approach.

5

The outcomes of this project have led to the development of the “Aurora Play and Practice: Connecting play and language in our bilingual setting” document. The aim of this document is to capture the processes and knowledge that were shared and experienced by those staff who were involved in the project. It is hoped that this document will provide valuable support for all staff in embedding a play-based approach to their work to support all children’s communication and language development.

The document is divided into 7 sections to aid navigation - to help you find what you require quickly.

6

SECTION TWO

Language & communication

2

This section outlines the key aspects of communication and language. It presents the main components as well as the subsystems of language.

What is communication?

Communication is part of our everyday lives and involves many complex cognitive and interactive processes that enable us to convey our ideas, desires, thoughts and needs to others. Communication can take on many forms including verbal (spoken), sign, non-verbal (gestures, eye gaze, facial expression, tone), written (drawings and words), music, and art. Typically, communication involves two or more people co-constructing shared meanings and understandings (McLeod & McCormack, 2015; Paatsch & Nolan, 2020; Paatsch et al., 2023).

In most communicative exchanges there is a speaker (the sender of information) and a listener (the receiver of information). The processes of communication are active and involve the speaker formulating their needs and thoughts and encoding them into language (spoken and/or sign) to convey to their conversation partner.

For example, a child who is hungry may communicate this in various ways – through crying, pointing, or verbalising or signing “I’m hungry”. The listener must then interpret the intended meaning and formulate a response. Throughout this exchange the partners will take turns and take on both roles as listener and speaker.

9

What is language?

Language is a set of complex symbols that are used in communication within social contexts. To become an effective language user, we master the rules for combining these symbols in both the expressive and receptive forms.

Receptive language involves watching and/or listening, while expressive language involves the productive form of language including sign, verbal, non-verbal and visual cues. Language also includes paralinguistic and linguistic cues such as duration, intensity, pitch, speed or rate of delivery, pausing, facial expressions, eye contact, gestures, physical distance, and body language. For example, in spoken language rising pitch at the end of an utterance may denote a question, while stress on a particular word that is marked by increased loudness may indicate the mood of a particular person such as anger or distress. Similarly in Auslan (Australian Sign Language), these cues are marked by facial expressions and intensity of signs.

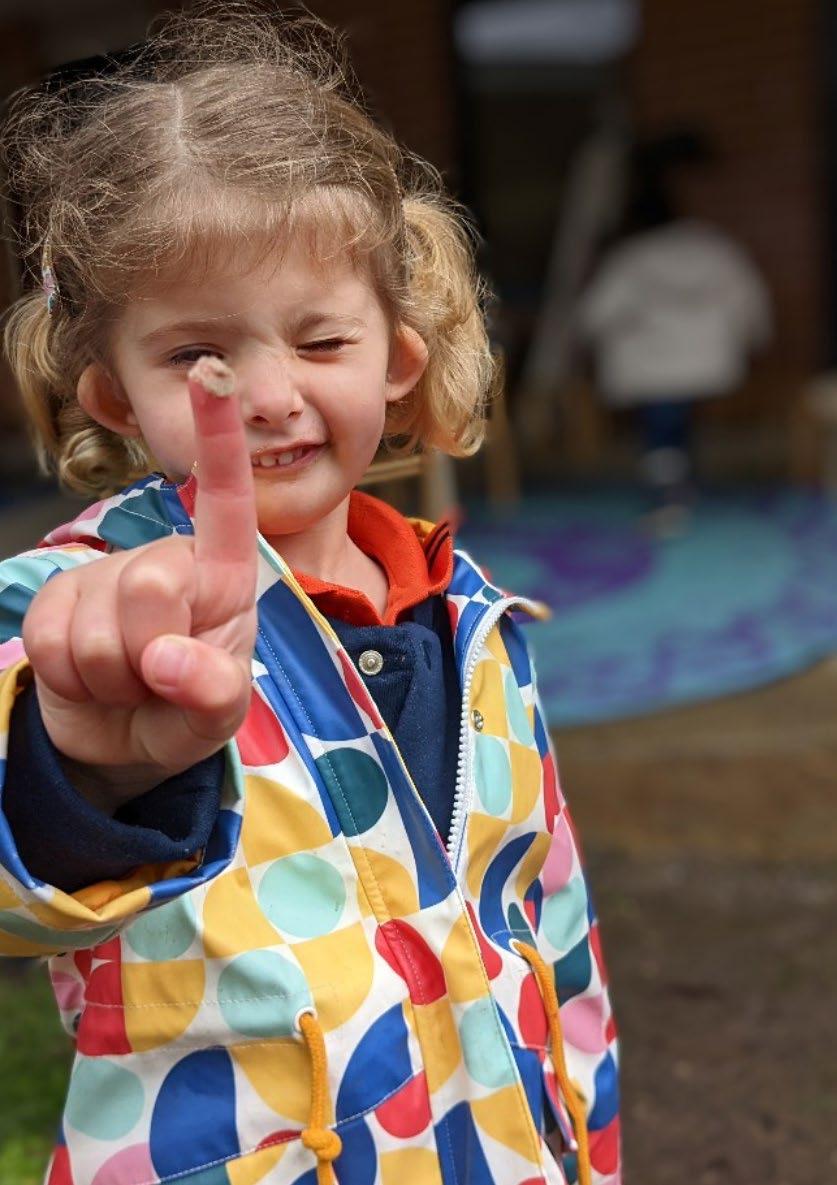

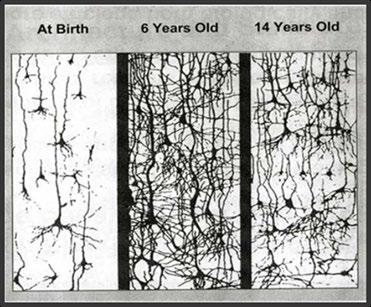

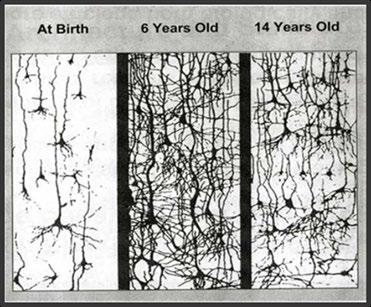

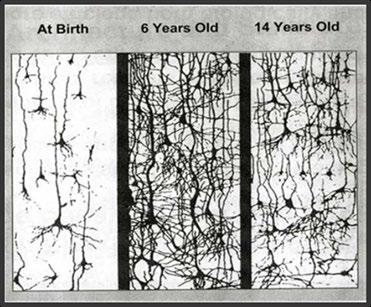

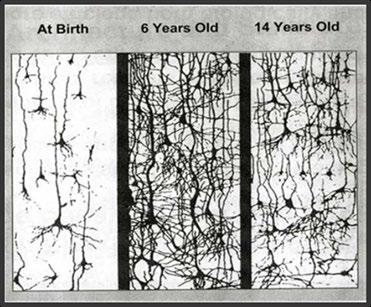

Language acquisition is a cognitive activity that supports the processes of learning. Strong language skills are linked to children’s literacy, learning, social and emotional outcomes. Children learn language through being exposed to opportunities to use language in social situations, where they learn to share attention with others, to direct attention to activities, people and objects in their world, and to understand others’ intentions, views, and perspectives. Rich authentic language experiences and access to language, in spoken or signed form, before the age of 6 years are critical in fostering powerful brain connections used for language and thinking (see diagram below).

10 Section 2 — Language & communication information

In any language, whether spoken or sign, there are three interrelated major components: Form, Content and Use that also include five sub-systems – syntax, morphology, phonology, semantics, and pragmatics. The Figure below shows the interconnectedness between the major components and subsystems of language. A brief explanation of each of the sub-systems are also included in the figure based on the research by McLeod and McCormack (2015), Paatsch and Nolan (2020) and Paatsch et al., (2023).

Language

Form

Form includes three subsystems of language:

Syntax

The structure of phrases and sentences – often referred to as grammar;

Morphology

The organisation and internal structure of words including adding prefixes and suffixes to mark change in meaning (e.g., use, useful, used, disuse); and

Phonology

The sequence and distribution of sounds.

Content Use

Content includes the subsystem of semantics

Semantics

refers to the meaning of words and word combinations – often called vocabulary.

Watch the following video of these twins communicating with each other and identify all the pragmatic skills that these boys are using throughout the interaction.

Use includes the subsystem of pragmatics.

Pragmatics

refers to the social use of language. Pragmatics draws on understanding human interactions in specific contexts and requires engagement with a communicative partner. Pragmatic skills include turn taking, repair, topic initiation, maintenance and closure, joint attention, eye gaze, asking and answering questions, and being contingent on your partner’s contributions as together you co-construct the conversation understandings (McLeod & McCormack, 2015; Paatsch & Nolan, 2020; Paatsch et al., 2023).

11

Auslan

Auslan is a visual-spatial language, using different handshapes, facial expressions and gestures. It has no written or spoken form. Auslan is not based on English, as it has a different set of rules for grammar and syntax. Its’ vocabulary is also different to English. Auslan is a natural language which was developed organically over time. It is also a visual-spatial language where hands, eye gaze, facial expressions and arm, head and body postures are used to convey messages. Precise handshapes, facial expressions and body movements are needed to convey both concrete and abstract information.

Section 2 — Language & communication information 12

Assessment of communication & language

There are many ways of assessing young children’s communication and language. Aurora uses the Cottage Acquisition Scales for Listening, Language and Speech (CASLLS), as well as the Communication Matrix and Auslan checklist to monitor children’s language and communication development.

Another way to assess children’s language is to obtain video samples of their everyday interactions with a variety of conversational partners. These video samples of approximately 5-minutes in duration, should be transcribed to enable analyses of the child’s receptive and expressive language including each of the five subsystems (pragmatics, semantics, syntax, morphology, and phonology). The following example template provides a way to analyse the child’s language using the transcript generated from the video. The first column of the template provides a section to analyse receptive language and the five sub-systems expressive language. The second column invites you to present a description of the child’s language that you observed in video and transcript. For example, in the section on Pragmatics, you may have observed skills such as turn taking, asking questions, making comments, using eye gaze. In the final column, include the specific examples from the transcript that demonstrates these skills.

13

Observation of communication and language: describing & analysing

Child’s Name

DOB:

Date:

Language Description Evidence

RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE

Verbal & Non-Verbal Listening and watching

PRAGMATICS

Social use of language

SEMANTICS

Vocabulary: meaning of words, sentences and phrases

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE

Verbal and Non-Verbal

SAMPLE

SYNTAX

Sentence structures, grammar

MORPHOLOGY

Internal organisation of words eg. Uncomfortable

PHONOLOGY

Structure, distribution and sequencing of sounds

This resource and others can be found in Section 7 (page 90) of this document.

Section

— Language & communication information 14

2

15

Talk patterns: adults and children

The importance of adult-child dialogue in facilitating young children’s language learning is well established in the research literature (Paatsch & Nolan, 2020; Paatsch et al., 2023).

The significance of quality classroom talk interactions not only supports children’s language and communication but also leads to strong literacy, and overall educational success throughout life. It is important for adults, including educators, teachers, allied health professionals, support staff and parents to support young children’s language development by providing rich and authentic learning environments, including play.

In addition, reflecting on your own talk patterns is also critical to identify the aspects of your talk that are most conducive to developing young children’s language. Paatsch, Scull and Nolan (2019) developed a framework that includes some typical teacher talk behaviours and child responses evident in interactions between children and adults. This framework can be used to support you to identify your own adult-child talk patterns.

The framework is presented in the following table. This table provides a summary of each teacher talk behaviour colour-coded by question types (orange), non-verbal or nominating children (dark blue), instructing, modelling, reading and providing personal comments (purple), extending, reformulating, repetition and acknowledgement of children’s communicative attempts (light green), and pausing and oral close (yellow). The children’s responses are divided into three categories according to: (1) whether their response was verbal or non-verbal (light blue); (2) whether their response was about the immediate environment [e.g., a picture from the book] or the non-immediate environment [e.g., talking about something or someone at home] (grey); and (3) the type of response (pink).

Section 2 — Language & communication information 16

The two tables below list each behaviour and response and provides a short description with some examples.

Teacher behaviours

Closed question

Open question

Statement question

Nominating - Name

Teacher Non-verbal

Modelling

Instructing

Personal comment

Pausing wait time

Non-verbal

Verbal

Child question

Reading Explain

Labelling

Child repeating

Predicting

Child responses

Nominating - Non-verbal Non-immediate

Reformulating

Teacher repeating

Acknowledgement

Oral close

Immediate

Initiating

Extension Opinion

Recall

Yes/No

Adding on

17

Code Description

A question to which the answer us known by the teacher and to which there is only one acceptable response. (eg. is the bird flying or running?)

Closed question

Open question

Statement question

A question to which the child holds the answer. The response usually involves a small selection of acceptable possible choices (eg. What’s your favourite colour?)

A question which requires a yes/no response

A question to which the child is encouraged to predict what may be happening in the text/illustration (eg. what do you think will happen?)

A question to which the child is encouraged to infer from the text/illustration (eg. why don’t you think he was happy?)

A question requiring the child to relate to their own experiences and world knowledge

A question to which the child is encouraged to give their opinion (eg. which character did you like the best?)

A question to clarify the child’s response.

A question that acknowledges the child’s response (eg. it looks like a very happy rabbit, doesn’t it?)

A question which provides further information (eg. it also looks like a queen with a crown, doesn’t it?)

Nominating: Name When the teacher specifically directs a task/question to one child.

Nominating: Non-verbal When the teacher reads or paraphrases from the text

Reading When the teacher reads or paraphrases from the text

Modelling

Instructing

Personal comment

Modelling a language pattern structure

Teacher instructs children what to do

Teacher provides own experiences and opinions

Extension Building on what the child says

Teacher repeating Verbatim repeat of what the child says

Acknowledging

Pausing (Wait time)

Affirmation - verbal or non-verbal

Connected to an expectation - Teacher does not fill the response after their prompt that requires an action but waits for the child to respond

Section 2 — Language & communication information 18

Reformulating

Oral close

Teacher responds to the child’s response by reformulating what was said with the correct grammatical structure

Only the last phrase of the teacher’s utterance is the oral close - anticipating the oral close (eg. “and he ate through 5...”)

Child question

Explaining

Labelling

Initiating

Opinion

Recalling

Inquiring - clarifying - asking for more information

Response to why a question - explaining something

Naming something specific that related to the book/activity

Response does not directly relate to the teacher’s question/statement

Give own opinion

Drawing from past experience - Drawing on known knowledge

Child repeating Teacher’s utterance repeated verbatim

Yes/No

Predicting

Adding on

Simple Yes/No response

Suggesting possible actions/events often in a response to a “What...” question from the teacher

Children added further information to the teacher’s talk (eg. Teacher: “:It’s yellow”, Child: “and red”)

Child Responses - Descriptions (Paatsch, Scull & Nolan, 2019)

19

The following two excerpts provide some examples of adult-child interactions and a description of the talk patterns when applying this framework for observing and describing the talk patterns.

Excerpt 1

1. Teacher: [Reading] Here is the blue sheep and here is the [Pause]

2. Child: Green

3. Teacher: And where is he standing?

4. Child: On the grass

In this excerpt, Line 1 shows that the teacher is reading the story of The Green Sheep by Mem Fox and Judy Horacek, where she reads the text (Reading) but leaves a pause for the child to fill in the missing words (Oral Close). In Line 2 the child provides a response. Applying the three categories of child responses from the framework, we can see that the child provides a verbal response (Verbal), that the talk is about the immediate context of the book (Immediate) and that the response type is Labelling as the child is naming something that is related to the book.

Section 2 — Language & communication information

Excerpt 2

1. Teacher: Let’s set up these boxes to be a café. What do you think Alfie?

2. Child: Yeah, put here. I shop person.

3. Teacher: Yes, you can be the shopkeeper and I will be the customer. What do you think I will buy?

4. Child: Buy chocolate cup. Buy cake.

5. Teacher: Oh, I’m going to buy a chocolate milkshake and a cake. Great! I’ll go to the table and order, and you go and make me a chocolate milkshake.

In this excerpt the teacher commences the conversation with instructing the child to build a café with boxes. She then follows this instruction with an open question (Line 1). In Line 2 the child provides a verbal response about the immediate environment that starts with an acknowledgement, followed by two instructions (‘put here’ and ‘I shop person’). In Line 3 the teacher’s response starts with an acknowledgement (‘yes’), followed by a reformulation of the child’s utterance (‘can be the shopkeeper’) and an extension of the child’s contribution (‘I will be the customer’). She concludes her turn by asking the child another open question (‘what do you think I will buy’). The child explains to the teacher what he will buy (Line 5). Lines 6 and 7 show that once again this teacher acknowledged the child’s contribution (‘Oh’), reformulated the child’s response (I’m going to buy a chocolate milkshake and a cake), then concludes with another instruction (‘I’ll go to the table and order, and you go and make me a chocolate milkshake’).

21

Play SECTION THREE

3

In this section the activity of play will be outlined, with a specific focus on pretend play. The skills of pretend play will be introduced and an overview of how and why to assess play is provided. The link between pretend play and language/communication is discussed.

What is play?

Play is a difficult concept to define because it has so many different meanings informed by different theories. However, it is widely agreed that children have an innate curiosity and desire to play. In play, children enlist their imagination, creativity and physical movements in a way that satisfies their own interests and curious mind. Furthermore, play affords children to use their imagination to explore, experiment, discover, collaborate, improvise, and create.

If you would like to read more about play, Lennie Barblet (2016) provides some insight into the general principles that can be used to define the activity.

23

Types of play

There are different types of play experiences that teachers and professionals can use to structure play-based learning. Each type of play has a purposeful role to engage children in meaningful exploration, investigation, and imaginative experiences. Together, all types of play have a collective role in supporting children’s learning and development.

The following section provides a description and visualisation for some of the most common types of play. Please note that this is one way of categorising different types of play.

Constructive play

Building of structures and/or objects using blocks, sticks, logs, recyclable materials or other loose parts.

For example, in the images below children are engaging in constructive play when playing with train tracks (Photo 1) and building with blocks (Photo 2).

Section 3 — Play 24

Physical play

Active exploration of movement using gross and fine motor skills. Gross motor skills are large body movements like crawling or climbing as illustrated in photos 1 and 2 below. Fine motor skills are small muscle movements, like the work that fingers do when moulding playdough as illustrated in photo 3 below.

25

Outdoor play

Imaginative, physical, and social explorations of places, objects and experiences in an outside space. For example in the photos below, children are engaging in gardening, baking cakes in the sandpit, and exploring the natural environment during bush kinder.

Section 3 — Play 26

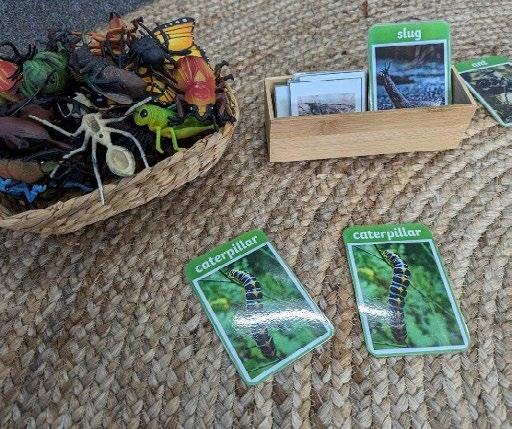

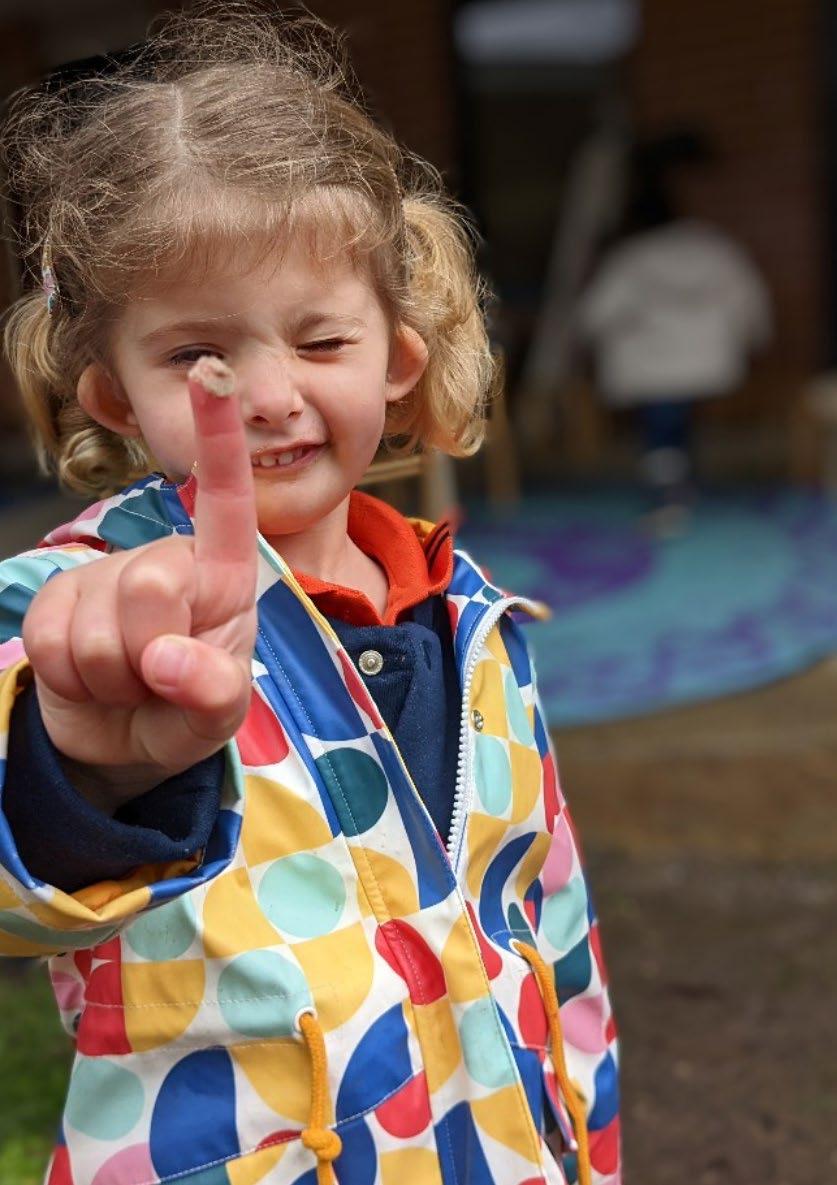

Discovery play

Investigation of the world and the concepts, objects, and experiences within it.

For example in the images below children are engaging in discovery play when exploring the features of fish (Photo 1) and reading a book (Photo 2).

27

Games with rules

Experiences that follow a set of rules to reach a shared objective. For example, in the images below children are playing memory match which requires all children to follow a shared set of rules for the game to be successful. Other structured games may include board games or ‘What’s the time Mr Wolf?’.

Section 3 — Play 28

Digital play

Digital play includes experiences that involve a combination of play types using a range of digital and non-digital resources. For example, children may create and share digital content using different Apps and software to inform their play. In pretend play, children might use objects that represent digital technologies. For example, they may use a piece of cardboard as an iPad or a block as a mobile phone. Children may draw scribbles that represent a QR code or some children may use purpose-designed pretend technologies such as wooden phones, computers etc.

29

Creative play

Self-expressive experiences that engage with the multiple art forms (visual, performing, music and media). For example, children might build rocket shoes out of tissue boxes. In the images below, children are engaging in creative play when they are creating a pretend world with gemstones (Photo 1) and playing music (Photo 2).

Section 3 — Play 30

Pretend play

Exploration of experiences through the creation of an imaginary world where children take on roles and substitute the meaning of objects and actions.

For example in photos 1 and 2 below children are enacting the roles of the doctor and patient using actions, voice and objects. In photo 3, children are enacting the roles of shopkeeper and shopper to play out a pretend scenario in a shop.

All of the different types of play are valuable to support young children’s learning and development. What is even more exciting about play is that often two or more play types are combined to further enhance children’s learning. This is especially the case when pretend play is encouraged in classrooms.

For example in photo 1 below children have engaged in constructive play to build a car. They are also engaging in pretend play to enact driving the car. In photo 2, children are engaging in pretend play to enact a scenario involving doctors and patients. During this play they are also engaging in creative play to write symbols on paper to mimic a doctor writing out a patient’s medical chart.

For further interest...

The following video outlines another perspective drawing upon Parten’s social behavioural theory. Parten categorised children’s social play in stages. However, as we have now learnt more about play, it is widely acknowledged that Parten’s categories of play are not always linear. Sometimes children like to play on their own or watch the play of others.

Watch video on YouTube here or search for the following URL: The 6 Types of Play - Adobe Spark Video Lesson

Section 3 — Play 32

and play-based information

33

Pretend play skills

In pretend play, children explore the world through the creation of an imaginary situation where children become someone else and change the meaning of objects and actions. Pretend play skills are outlined in what follows.

Object substitution

Children change the meaning of objects to become something else. For example, a carrot becomes a toothbrush. As their symbolic representation skills develop, children will begin to use gestures with their hands to represent an imaginary object (e.g., a phone) or words to communicate something is there which isn’t (e.g., “pretend I am calling you on a phone”). This is the most advanced form of object substitution and indicates that the child’s play is internally driven by their desires rather than physical objects.

When children are using an object to represent something else, they are no longer concerned with the visual properties of the objects, but rather the meaning associated with it. That object becomes a pivot which enables them to act in a form of abstract thought where they are separating the object or word from its meaning.

Section 3 — Play 34

Role enactments

Role enactment involves the act of undertaking the persona of a person (or animal) other than themselves and enacting this through physical actions, affective behaviours, and verbalisations. Role enactment begins to emerge when children can de-centre themselves from the situation. This involves the child being able to enact schemes that are representative of others, such as using a phone, reading the paper, and also involve others in the play. These enacted schemes form the situations and events of a play episode.

When children begin enacting the activities of others, it illustrates their knowledge of the relationship between the body as self and bodies of others are becoming established. Enacting the role of someone else requires children to maintain an element of awareness of the non-literal existence and reality. Accordingly, the child is developing their understanding of dramatic play as a symbolic mental representation; an element of meta cognitive development (i.e., thinking about thinking!).

The complexity of a play episode develops according to the amount of knowledge that a child has obtained relating to the consequences of their pretend action. For instance, children may arrive to the shops in a car, undo their seatbelts, open the car door and walk into the supermarket. Alternatively, they may be involved in a car accident on the way. This suggests that in order for the story of a play episode to progress, the child must conceptually understand what can happen when they are driving their car to the shops.

35

Play sequences

To successfully engage in pretend play, children need to sequence their pretend actions with creative imaginative scenarios, sometimes referred to as narratives or scripts. As children mature in their play, these sequences become more complex, logical and reflective of real-life causes, effects and phenomena.

Organising these sequences in play requires communication and planning with play peers. It also draws upon their own knowledge and experiences.

Play scripts

Play scripts involve the stories that the students develop during their play. This play skill is strongly linked to childrens abilities to develop narrative.

Narrative involves the ability to set the scene with characters and setting, present a logical sequence of events, present a problem or several problems, develop resolutions to these problems, and to draw a conclusion.

Children develop scripts where they begin to reflect what they do (e.g., pretending to drink etc.) then move to more complex stories that may include fantasy stories whereby the play may take 2 to 3 days to finish and may have several problems that appear with resolutions.

Section 3 — Play 36

37

Metacognition (play planning)

When children plan their play with peers, they use more complex communication strategies known as metacommunication. This is where children will communicate with each other outside of the play to plan and organise the play, such as using a statement of intent ‘I am going to be the dog’ or pretend talk ‘pretend you are the dog’. Metacommunication of this nature allows the play episode to persist and develop with the incorporation of more complex ideas and object substitutions.

Doll or figurine play

The ability to impose meaning on a character also supports children’s literacy whereby they can understand the role of characters in a story.

Section 3 — Play 38

Assessment of pretend play

It is important for teachers and professionals to assess children’s pretend play skills to know where the child is at in their pretend play development and to inform the planning of future play sessions that address the needs of each child. Results from play assessments can be used to report to parents and other teachers and enable teachers and professionals to determine their own role in supporting children’s play and learning.

There are many assessments that are available to assess children’s play skills. At Aurora, we use the Pretend Play Checklist for Teachers (PPC-T) (Stagnitti & Paatsch, 2018). The PPC-T is a non-standardised criterion-referenced assessment to observe pretend play in the following five pretend play skills: (1) play scripts; (2) sequence of play actions; (3) object substitution; (4) doll/ teddy/figurine play; and (5) role play. The PPC-T assesses children’s these five play skills, each consisting of 9 levels of ability ranging from simple (Level 1) to complex (Level 9). It is important to remember that children develop at their own pace so for many children their pretend play skills may vary across each of the five play skills depending on their communication and play abilities. A copy of the PPC-T manual and score sheets are available at the school and will provide more information about assessment and scoring procedures.

39

Aurora educators will use the Pretend Play Checklist for Teachers to support the development of children’s play skills. Educators will be allocated time to observe children’s play and complete individual checklists for children that may require interventions and a proactive approach in supporting children to continue to develop their play skills.

Supporting children to develop their pretend play skills is important as play fosters higher complexity of cognitive, social and emotional development, as children are encouraged to:

• think more deeply

• make connections between their learning and prior experiences

• engage in higher levels of metacognitive learning processes

• collaborate with peers and teachers.

Pretend play also has a major role in fostering the development of communication and language.

Section 3 — Play 40

The link between pretend play, language and communication

It is well established in the literature that there is a strong link between young children’s play abilities and their language acquisition. Both language and pretend play are symbolic and rely on communication within social contexts. In addition, both activities depend on the support and scaffolding by competent language users and players (Creaghe & Kidd, 2022; Creaghe et al., 2021; Quinn et al., 2018; Paatsch et al., 2023)

Children create narratives in their pretend play which increase in complexity as their play skills develop. In their narratives, children follow joint shared meanings with each other when they:

• Exchange communication to extend on the ideas of others

• Introduce a new idea

• Add in new props

• Show acceptance or rejection of peers’ ideas through verbal and non-verbal communication

41

All of these skills embedded in pretend play promote the type of intentional learning (Whitebread, 2010) which requires children to monitor and control their thinking and behaviour. In addition, children need to understand and regulate co-players’ thinking so that collective pretence can continue – play can be established, sustained and maintained.

A strong relationship exists between pretend play, language and communication. For example, research has also shown in pretend play, children:

• Produce more complex grammatical language than in routine and guided activity (Fekonja et al., 2005)

• Solicit more verbal responses from others, resulting in greater social and linguistic interaction (Fekonja et al., 2005)

• Show an early emergence of narrative in play compared with when they were in non-play contexts (Aksu-Koc, 2005)

• Show significant improvements in both play and narrative with significant greater improvement in vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (Stagnitti et al., 2016)

• Bridge the connection between the development of creative and language skills and abilities (Russ & Fiorelli, 2011)

• The ability to symbolise and use an object as something else, which has been found to be a predictor of a child’s expressive and receptive language ability (Stagnitti, Paatsch, Nolan & Campbell, 2020)

• In pretend play children form imaginary stories that support the development of narrative skills including story comprehension and story production.

Section 3 — Play 42

Link between pretend play and language in children who are deaf and hard of hearing (DHH)

There is very little research that has specifically explored the play behaviours, particularly pretend play, of young DHH children in the preschool years. Furthermore, there is a paucity of recent research that has explored the relationship between DHH preschool children’s pretend play and their language abilities. Findings across the early studies show varying results, particularly when comparing play and language abilities of DHH children with their hearing peers (Andreeva et al. (2017).

For example, a study involving one four-year-old deaf child using American Sign Language (ASL) enrolled in an ASL/English bilingual classroom found that the child’s play behaviours across 22 play episodes, as observed using a Play Observation Scale, varied in relation to the play context and play partners. The results also showed that this child was capable of engaging in play behaviours that were similar to those of her hearing peers (Musyoka, 2015). Similarly, in an earlier study by Gregory and Mogford (1983), they reported no significant differences in the play levels of DHH children compared with their hearing peers, although the DHH children produced fewer sophisticated play behaviours in pretend play. Spencer (1996) investigated the association between pretend (symbolic) play and expressive language in three groups of 2-year-olds: (1) deaf children with hearing parents; (2) deaf children with deaf parents; and (3) hearing children with hearing parents. Results showed a consistent pattern of association between language levels and symbolic play but not between play and hearing status, confirming the strong link between expressive language and play.

43

In contrast to findings that showed similar play abilities between DHH children and their peers, Quitter et al. (2016) compared symbolic (as measured when child used substitution) play and novel noun learning in 108 children with cochlear implants and 96 hearing children aged 5 months to 5 years. Results showed that children who were implanted before 2-years of age performed significantly better. However, the group of hearing children demonstrated higher levels of pretend play and novel noun learning compared with the DHH children. Similarly, Brown, Rickards and Bortoli (2001) had previously reported differences between hearing and DHH toddlers during free play with their caregivers. Results showed that the 10 hearing children showed significantly higher levels of pretend play and word production compared with the 10 DHH children, suggesting a strong association between language and pretend play abilities.

In a recent study that investigated pretend emotions (i.e., understanding that a person is crying as part of a game and not that they are sad) in 173 children (82 DHH and 91 hearing) between 3 and 8 years of age it was found that the DHH children who had experienced reduced access to language and communication had a restricted understanding of the communicative intentions of emotional expressions, which was strongly related to their difficulties with pragmatics and expressive vocabulary (Sidera, Morgan & Serrat, 2020). Further links between play and language abilities have been reported in an earlier study that investigated these abilities in 11 deaf-blind children – five with multiple disabilities (Pizzo & Brice, 2010). Results showed that children with higher levels of communication showed more advanced play skills.

Together, these findings demonstrate the strong link between language and play and suggest that further research is warranted to provide more contemporary understandings of the pretend play and language (oral and sign) abilities of DHH children in the preschool context.

Section 3 — Play 44

45

SECTION FOUR

Supporting a play-based approach: The learning environment

4

The following sections present the four key aspects to consider when thinking about the learning environment when supporting a play-based approach:

1. Physical space- appearance and set up of the learning space;

2. Resources – materials, equipment and resources provided to support learning;

3. Social and emotional aspects - interactions and experiences children have with their peers and adults; and

4. Pedagogy - the method and practice of teaching/educating.

These aspects influence children’s learning in a play-based approach as illustrated in the diagram below.

Each aspect will be described in more detail on the following pages.

PHYSICAL SPACE

LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

PEDAGOGY RESOURCES 47

SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL ASPECTS

1.

Physical space: supporting children’s Learning in a play-based approach

What we know from the research:

• Learning takes place in indoor and outdoor spaces.

• The layout of the environment will affect how children play and learn.

• For children who are deaf or hard of hearing, the acoustics of the space needs specific consideration.

• Young children learn best when they engage in stimulating environments.

• The organisation of the environment is a crucial component in an effective play-based learning approach.

Section 4 — Practice 48

PHYSICAL SPACE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL ASPECTS PEDAGOGY RESOURCES

Good learning environments provide:

• Well defined spaces for quality interactions with educators and children,

• Spaces for relaxation, passive and active play, as well as small group play,

• Opportunities for children to explore, investigate, and be creative.

49

Look at the different ways space can be defined to encourage solitary or small group play

Practical application

A physical space that supports children’s learning in a playbased approach:

• Provides an environment that supports children’s health and safety, which includes thinking about eliminating any potential safety concerns such as trip hazards and cluttered walkways.

• Includes smaller spaces for small group play and individual play, as well as larger, open spaces (clear of furniture and equipment) to encourage gross muscle/motor play.

• Incorporates passive areas where activities such as looking at picture storybooks or completing puzzles can take place without being interrupted by activities that require more movement such as block building or dramatic play.

• Positions spaces so that the furniture creates little pockets of enclosure when this is possible as there is the need for educators to be able to see all areas of the room and for the children to view who is entering the space.

• Considers the lighting so it is easy to see things in the environment. This can be helped by not overcrowding the room with objects or covering all walls and windows with artwork.

• Ensures that the space is acoustically sound.

• Displays resources in ways that make them assessable to the children and not too many as they will be overwhelming. For example, on low shelving, not cluttered together but in ways that make them look inviting to play with.

• Includes photographs, portfolios and displays so children can revisit their experiences and share them with others.

Section 4 — Practice 50

Staff carefully consider when it is time to change the physical set-up as too often can become unsettling while too long between changes can become boring for the children. The children need to feel a sense of comfort and familiarity in the environment so lots of dramatic changes to the space could cause them to feel unsettled. One idea is to make changes to the environment with the children, so they are part of what is happening to their environment.

51

Think of ways you can display the children’s work that will create interest that will lead to conversations/communication.

Considerations when communicating using AUSLAN

• Having an open space

• The position of the windows in relation to the teacher/speaker and the child

• Lighting

• Digital screens

• Mirrors in corners to help visual awareness.

You can think of the learning environment as the “third educator” because children’s engagement and interaction with their environment helps them construct their own learning.

Here are some ideas on how outdoor spaces can be set up to support young childrens’ curiosity, play and learning. Note how the larger outdoor space has been divided into ‘areas’ where specific activities happen.

Section 4 — Practice 52

The following Table highlights the important features to consider relating to the physical space.

Features

Health & safety

Defining spaces - large, small, passive, active

Associated questions

Is the set-up of the learning environment safe?

Is there a variety of safe surfaces provided to encourage motor development and risk?

Is there enough room for all types of play – individual, small group, passive, active?

Lighting Is there enough light in the room so everything is easy to see?

Display of resources Are resources displayed in inviting ways where it is easy to see what is available?

Accessibility of resources Can the children access the materials and resources easily?

Displays of children’s learning experiences

Are the children’s learning experiences displayed around the room so they can share them with others?

You could also use the Pretend Play Checklist for Teachers (Stagnitti & Paatsch, 2018) to ensure the way the physical space is set up provides opportunities for the children to access what is needed to develop their pretend play. For example, the physical space must have places to engage in all kinds of play.

Section 4 — Practice 54

Questions to stimulate reflection

• Consider the size and shape of your room, how can you make the best use of your available space and create a free flowing yet safe and stimulating area for the children (and staff)?

• How does the physical set up of the learning environment promote the child/ren’s learning, development and well-being?

• Is the physical space set up in such a way that it is deaf friendly? For example, no closed spaces without mirrors to enable deaf staff to monitor from other parts of the classroom, children able to see who is coming/entering the space.

• Does the physical set-up of the learning environment support the well-being of staff?

• How do you decide when it is time to change the physical set-up of the learning environment?

Resources

Create the perfect play space: Learning environments for young children.

This pdf is a ‘How to’ booklet produced by PSC National Alliance in 2012. It covers all aspects of designing a learning environment that supports children learning through play including: what children need from their environment, supporting learning outcomes, key considerations, features of a good environment, and managing risk in your environment. You can access this document here:

Planning for play-based and inquiry learning. This is a downloadable booklet that provides insightful thoughts about planning accompanied by visuals. You can access this document here:

55

Resources: supporting children’s Learning in a play-based approach

What we know from the research:

The resources that are provided for the children to use will define how the children play with and use them.

Resources and materials enhance learning when they reflect what is natural and familiar, and also introduce novelty to provoke interest and more complex and increasingly abstract thinking.

Resources need to be chosen to suit the learning aim, the stage of development of the child and their play skills. Some children may need life-like materials to stimulate their play, others may enjoy more open-ended materials. Too many resources can be overwhelming and doesn’t allow the children to focus.

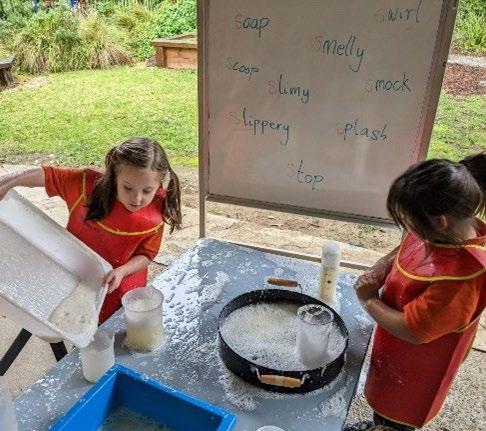

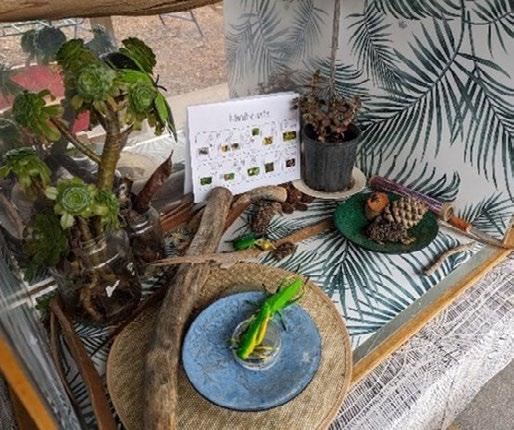

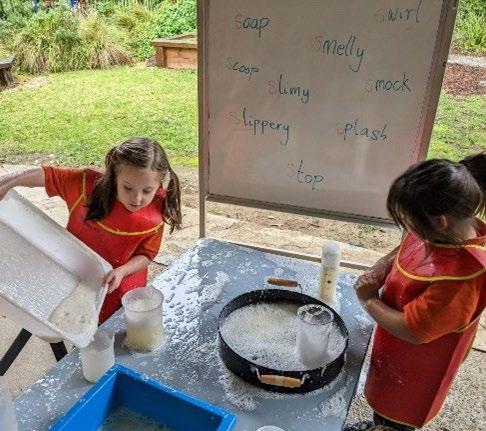

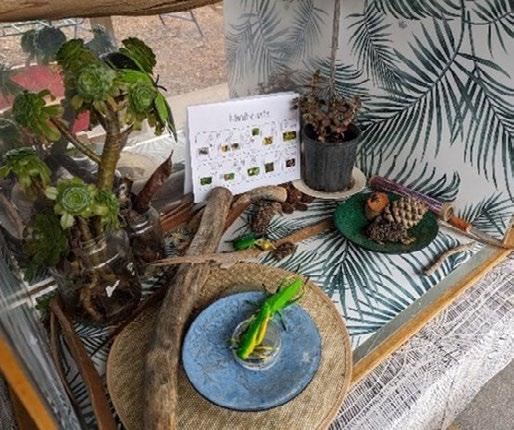

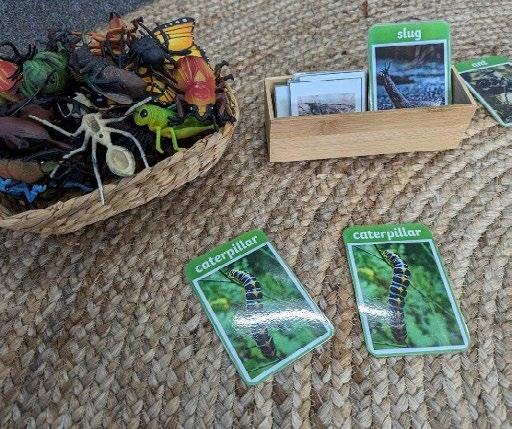

Open-ended materials are objects that can be used in a variety of ways such as natural materials. For example, rocks or gumnuts collected from the outdoors can be used as pretend pieces of food or money. Small blocks could be used as people or a phone. The following photographs provide some examples of open-ended resources used at Aurora that have been set up in ways to attract children’s interest.

Section 4 — Practice 56

PHYSICAL SPACE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL ASPECTS PEDAGOGY RESOURCES

2.

57

natural materials in combination with other objects can provide stimulating play experiences.

Using

Practical application

Choose resources that:

• reflect the interests, needs, lives and identity of the children.

• are flexible and allow open - ended experiences (not just one way of using the materials).

• are safe for the children to use i.e. have no small parts where children could choke, or sharp edges where they could injury themselves, or are not damaged.

• incorporate natural materials (non-toxic) as resources such as leaves, gum nuts, small pebbles.

• include everyday items from around the home as children enjoy real things as they can feel capable and grown up.

• provide a combination of life-like and openended materials to support all children’s play.

• can easily be moved around the space to give you flexibility of where they can be used.

Section 4 — Practice 58

The following Table highlights the important features to consider.

Features

Health & safety

Quantity

Type

Associated questions

Are the materials and resources safe for the children to use?

Do I have sufficient resources for the children to use, especially popular items?

Do I have too may resources out for the children which creates a feeling of being overwhelmed?

Do I have a balance of life-like and open-ended materials to support all children’s learning and engagement in play?

Do I have resources that reflect the children’s life experiences?

Access Are the resources displayed in a way that makes them accessible to the children?

Learning Are the children able to manipulate/engage with the resources/materials?

59

Questions to stimulate reflection

• What resources do I have access to?

• Does my collection of resources contain both life-like and natural, open-ended materials?

• Do I offer a diversity of materials/resources at all times?

• Where could I source more resources from?

• When setting up resources/materials do I consciously think about whether these are visually appealing or overloading the children?

• Do I build the resources up over time (especially for younger groups) so the children do not become overwhelmed?

• What other ways could I use my current resources, materials and equipment to provoke children’s interest and learning?

Resources

The link below will take you to a video where you will hear ideas for open-ended materials that are suitable for young children. These materials such as balls, recycled cardboard or fabric, leaves, petals and shells support children’s development and encourage thinking, imagining and problemsolving. The Raising Children Network is an Australian parenting website.

Play idea suitable for 0-8 years

Section 4 — Practice 60

61

3.

Social and emotional aspects:

Supporting children’s learning in a playBased approach

What we know from the research:

The social and emotional climate (SEC) includes experiences children have with peers and adults that can affect their emotional well-being, development, and behaviour.

The classroom environment needs to support young children’s self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making as these are competencies that they will use throughout their lives.

Young children thrive in a positive social and emotional classroom climate.

Section 4 — Practice 62

SPACE

ENVIRONMENT

& EMOTIONAL ASPECTS PEDAGOGY RESOURCES

PHYSICAL

LEARNING

SOCIAL

The following diagram defines these competencies and shows how they are interrelated areas in social and emotional learning.

Making positive choices about one’s behaviour and social actions

RESPONSIBLE DECISION MAKING

Forming positive relationships with others

RELATIONSHIP SKILLS

SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL LEARNING

SELFAWARENESS

Understanding one’s emotions and associated behaviours

Showing understanding and empathy for others

SOCIAL AWARENESS

SELFMANAGEMENT

Ability to manage one’s emotions and behaviours

63

Practical application

Developing respectful and trusting relationships

Think about all the interactions you have with children throughout your working day. These make up the social environment. To support children to develop respectful and trusting relationships there needs to be opportunities created for them to interact with their peers and adults.

In practice this looks like:

• providing emotional support when the child or children need it

• showing that the adult understands the child/ren’s feelings through demonstrating what empathy looks and feels like

• using encouraging words or sign to help the child/ren feel safe and secure in the environment as this will enable them to learn and develop and try new things

• acknowledging accomplishments or attempts to accomplish something to raise the child/ren’s confidence to explore and work towards overcoming any challenges

Promoting children’s independence

Once a child/ren feel safe and secure in their environment, their confidence in managing their own emotions and decision-making can be best supported. In a play-based approach this is provided through:

• having resources and materials available for the children to access

• actively teaching children when its acceptable for them to select/take/find their own resources within the classroom

• providing choices of play activities, they can decide to participate in and accepting their decisions

Section 4 — Practice 64

Building children’s understanding of the feelings of others

During play children come in contact with other children either intentionally or unintentionally. It is during these encounters that emotional behaviours may be triggered i.e. both children wanting to play with the same toy. This is an opportunity for the adult to step in and model the appropriate way to deal with conflict, or to show emotions that are appropriate for the situation. This also helps the child understand their own responses to situations strengthening their self-management, social-awareness and self-awareness

Questions to stimulate reflection

• Do I allow children opportunities to choose what they want to play with, who they want to play with and how they want to play?

• Do I accept the choices that children make in their learning?

• Do I role model appropriate social behaviour?

• Do I interact in intentional ways to show how situations where emotions are triggered can be handled?

• Have I set up the classroom environment in a way that will support positive interactions between the children and also between staff? (room layout, time for relationships to develop).

This resource from the Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) focuses on supporting children to regulate their own behaviour. It offers practical tips and strategies. Resources

65

4.

Pedagogy (the method and practice of teaching): supporting children’s learning in a play-based approach

Adults can take on many different roles and implement different strategies depending on what is best to maximise the learning potential of the experience. However, getting your role as an adult right can be difficult. To most effectively choose a purposeful role that will support the play and not stifle it, adults should have conducted at least one assessment of a child’s play skills.

Pedagogical practices need to be adapted to the play situation as the adult should be responsive to the needs and abilities of the child. This means an adult may take on several different roles within one play episode. It also means an adult might plan to take on a certain role but need to change it on the spot if a different role is needed. Knowing what different roles entail and when they should be used is therefore important.

Section 4 — Practice 66

PHYSICAL SPACE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT SOCIAL & EMOTIONAL ASPECTS

RESOURCES

PEDAGOGY

In this document we are using Arthur and Beecher’s adult play roles (Arthur et al., 2022), that are represented in the diagram below.

This diagram depicts the adult play roles as a continuum where you would swap back and forth depending on the children’s play and your goal.

Adult role: Continuum of teaching strategies

Each role will now be described in more detail and the accompanying pedagogical strategies.

67

Facilitating Supporting Scaffolding Reflecting Co-constructing

Onlooker Stagemanager Coplayer Play leader Acknowledging Demonstrating Modelling Directing

Onlooker:

This role should be used if you are wanting the children to direct their own play. As an onlooker you are taking the most indirect adult role in children’s play. In adopting this role you are mostly observing what the children are doing in the play and acknowledging their activity if it is requested. This role should be used if you are wanting to children to direct their own play, you want to see how a child or children act in a play episode without an adult present or if the children are skilled players. Examples for practices include:

• Commenting on play without stepping inside the play. For example, ‘I like the costume you are wearing’

• Acknowledging the play through body language. For example, accepting a cup of pretend tea

• Indirect modelling of pretend play behaviour, literacy and language processes while sitting beside the child/ren and without drawing their attention to your behaviour.

Onlooker Stagemanager Coplayer Play leader

Indirect Strategies:

Acknowledging

Modelling

Facilitating

• Comment on play or provide acknowledgement through body language

• Modelling of pretend play behaviour or literacy and language processes

• Facilitating opportunities for play through the physical environment or interactions

Section 4 — Practice 68

Stage manager:

A stage manager facilitates the environment for children’s play from outside the play episode. Just like in real theatre, the stage manager does not have an active role in the play itself. An adult should take on the role of a stage manager if the children request new resources to be added to their play, if the adult wants to provide a prompt for children’s existing play scripts, the adult is setting up a scene for a new pretend-play topic or they are prompting children to engage in more complex object transformations. Examples for practices include:

• Adding a new toy to the construction area

• Adding a book to the pretend play space

• Setting up a vet space in the classroom

Supporting

Scaffolding

Reflecting

Co-constructing

Mediating Strategies:

• Prompt children to talk about and/or reflect on their play narrative

• Guide children’s interactions with peers

• Support children’s use of language/communication

• Engage with children in the play as a cooperative member of the play narrative

69

Onlooker Stagemanager Coplayer Play leader

Co-Player:

A co-player enters the play to engage alongside the children as an equal member to support and extend children’s play skills from inside the episode. An adult should take on the role of coplayer to scaffold children’s play skills while still following the child’s lead if they make suggestions for role enactments, play scripts or actions. Examples for practices include:

• Prompting children to talk about and/or reflect on their play narrative. For example: “Can you tell me what happened in your play? What role did you play? What happened when you went in the car?”

• Guiding children’s interactions with peers

• Supporting children’s use of language by introducing new words or modelling the correct use of words

• Introducing new scenes to the play script. For example, there was a car accident on the way to the shops.

Play leader:

The play leader is the most direct role an adult can take in a child’s play. In this role, the adult will take the full lead for the episode as either a player in the play or as a play leader outside of the play. A play leader role is used when an adult wants to provide more intensive coaching to support children to practice more advanced play skills they wouldn’t normally be able to do on their own. Practices include:

• Assigning children with roles

• Telling children what to say in the play script

• Telling children what to transform an object to

Onlooker Stagemanager

Direct Strategies:

Coplayer Play leader

• Adult guides or leads

Demonstrating

Directing

• Provides direct demonstrations and instructions

• Introduce plot conflicts to structure the play narrative

Section 4 — Practice 70

Questions to stimulate reflection

When planning your role in a child’s play episode, the following questions can help you.

• What can the child do on their own (refer to your play assessment data)?

• What goals do you have for the child’s play skills?

• What physical resources do they need to reach their goals?

• What support do they need from the adult to reach their goals?

71

SECTION FIVE Action research

5

What is action research?

Aurora School promotes an Action Research approach where practitioners from all disciplines research their own practice to ensure positive outcomes for children. Action Research is research in action rather than research about action. Action Research is a cycle that is informed by evidence (data) that is collected and reflected on to set learning and development outcomes for individuals and groups of children. It facilitates change through the process of a systematic inquiry.

You will notice that the Action Research process is depicted as a set of spirals that become narrower and narrower. This illustrates how the goals that are set become more defined as the process continues until the goals are either achieved and a new cycle begins (you develop a new Research Question to guide you), or the goals are modified, and a new cycle is planned to accommodate the modifications (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Kemmis, McTaggart & Nixon, 2014). Action research works through a cyclical step process of conscious and deliberate planning (from

O’Leary’s Cycles of Research

73

Koshy 2009)

Reflect (critical/reflexivity) Reflect Reflect Act (Implementation) Act Act Observe (research/data collection) Observe Observe Plan (strategic action plan) Plan Plan etc

The four-step process for each cycle consists of:

1. Observing the child/ren and collecting data

2. Reflecting on the data to make determinations about the child’s learning and development

3. Setting goals in consideration of what was learnt through the reflections (Research Queston)

4. Implementing the plan

You will see that the beginning cycle then moves into the next cycle (Observe) where you observe the implementation of your plan and collect the data you decided needed to be collected to inform your reflections on the success, or otherwise, of your goals (or in other words, to answer your Research Queston).

By working through the cycles, your planning and goal setting becomes more defined and fully informed by the data you collect and reflect on.

2.

Reflect (critical/reflexivity)

1.

The cycle begins with observations of the child/ren. These observations can be informed by many different data collection methods (eg. taking notes, checklists, etc.) Observe (research/data collection)

4.

The final step is the implementation of the plan. When will this happen (develop a timeframe)? Who needs to be involved? Act (Implementation)

Reflect Etc Observe Plan Act

Next step is reflecting on the data to decide on the child’s learning and development as well as your own practice to consider the best ways to assist the child. The templates outlined in this document may be helpful here:

• Observation of pretend play: Describing & analysing template;

• Observation of Communication and Language: Describing & analysing template;

• Analysis of my Professional Practices template

3.

Plan (strategic action plan)

The third step involves planning to support the child to achieve the goal that has been set by considering the data. This includes the goal for the child as well as the strategies that professionals will use to help the child achieve the goal. This means deciding on the research question, planning the action that will take place to support the child to be successful in achieving the goal, and considering what data will be collected to show the child’s progress towards the goal.

Section 5 — Action Research 74

Methods of collecting data

At Aurora data to inform the program is collected through the following methods:

• Mapping

• CASLLS

• Auslan checklist

• Early ABLES

• Language sample

• Learning stories / portfolios

• Tracking sheets

• Play checklist

• Video/audio recordings

• Photographs

• Children’s work

• Observations (e.g. Observation of pretend play: describing & analysing template; observation of communication and language: describing & analysing template)

• Reflections on own practices (e.g. Analysis of my professional practices template)

These methods are useful in collecting data on each child’s communication and language development and play skills. This data is then used to develop a suitable Research Question and then collect further information as you work through the Action Research cycles.

Things to think about when collecting data:

• What do I need to be able to answer the research question – or see progress towards the goal/s?

• When is the best time to collect the data? Will the child be more alert at certain times of the day? Do I need to collect the data across different times of the day and in different situations (i.e., during transitions from one activity to another) to gain a full picture of the child in relation to what I am focusing on?

• Do I need help (i.e., other colleagues) to collect the data? An extra pair of hands can be one way so you can be released from a task to enable you to collect data.

• What distractions do I need to be aware of when I collect data so I gain a true picture of the child’s development/learning?

75

Developing research questions

One way to think about how we develop research questions is to use the analogy of an onion. Think of all the layers of an onion. All we see from the outside is the onion skin. It is only when we start peeling back the skin that we see the many layers that make up the onion. Use your data to peel back the layers of what you are seeing. You may find it useful to use the following templates to help you do this: Observation of pretend play: Describing & analysing template; Observation of Communication and Language: Describing & analysing template; and Analysis of my Professional Practices template.

Once you have analysed and reflected on the data about a child’s language and communication, and their play skills, you can use the following illustration as a guide to setting a Research Question.

Section 5 — Action Research 76

Professional Practice (PP) Child Communication & Language (CCL) Play (P) RQ CCL + P + PP = Research Question (RQ)

The following can be used to also help guide your development of your research question.

How do my practices (add your practice strategies here) in the pretend play context support (insert child’s name) to (insert your communication and language goal for the child) and (insert your play goal for the child)?

Some of your colleagues have researched the following questions:

• How educators can modify their practices to become more stage managers, progressing to co-players, to support and facilitate varied play scripts and language, through modelling, and open-ended questions?

• How do my practices in the pretend play context support MJ to expand his verbal vocabulary and logically sequence his play?

• How do my practices in the pretend play context as a play leader support MJ to expand his verbal vocabulary of farm animals and logically sequence his play with 3-4 actions?

• How do our practices in the pretend play context support a child to engage in conversational turn taking with a peer and create small play scenes using characters?

• How do my practices in the pretend play support a child to demonstrate advanced object substitution (to use the same object for two or more things) and expand their vocabulary (Auslan and English), developing their nouns and verbs in the area of transport?

• How do my practices in the pretend play context support a child to use 3rd person regular present tense (-s) and use figures to create familiar stories that are reflective of home within their play?

• How might my co player interactions better support a child to respond receptively during one or two step pretend play sequences ?

• How might my play leader interactions better support a child to respond receptively (using nonverbal or Alternative and Augmentative Communication [AAC]) to manipulate and explore objects and repeat single actions?

• How can my co player interactions improve child’s joint attention in order to promote play sequences with real and toy objects?

77

Starting the action research cycle

Section 5 — Action Research 78

Reflect Observe Plan Act Reflect Observe Plan Act Reflect Observe Plan Act

is the first cycle

the second cycle

is the third cycle

This

This is

This

Step 1

Choose a case study child and observe their learning and development in the areas of language and communication, and play. You can use any existing data (checklists, records, notes etc.) that you already have to make an assessment of what to focus on, or you may like to collect additional data to help you make a decision.

Step 2

Reflect on this data to determine the child’s strengths and challenges. Discussing these reflections with colleagues will help clarify your analysis.

Step 3

Using your analysis of the child’s communication and language development and play develop your Research Question using the formula: CCL + P + PP = Research Question. Once you have the Research Question you can plan the strategies and experiences that will assist the child to work towards your goal as stated in the Research Question. At this stage of the Action Research process you also decide on what data you will need to collect when you implement this plan so you can make a judgement about its success or otherwise.

Step 4

Decide when and where you will implement your plan and then go for it, making sure you collect data so you can judge whether the Research Question was achieved completely, partially or not at all. All this will help you decide what to do next…This is the beginning of the next Action Research cycle when you observe what occurs when the plan is implemented…and so the cycle continues.

Action research projects differ in length depending on the goals and contextual factors such as child responsiveness, time to engage in the project etc.

79

SECTION SIX

Working with colleagues

6

Introduction

When working with children individually or as a small group, it is important that you learn all you can about each child including their abilities, background, and history of hearing loss. It is very helpful to work alongside your colleagues as you collectively build a profile of each child. For example, there are things that you will know about a particular child, however your colleagues (especially those from different disciplines) may hold other knowledge. When all information is brought together and discussed, a more comprehensive understanding of the child as a learner can be established.

81

The following diagram is a prompt to use as a starting point in your search to build a comprehensive picture of a child.

Child

• Age

• Personality

• Learning dispositions

• Interests

Family

• Place in family

• Siblings

• Family background

• Language/s used at home (Spoken/Sign/ Language other than English)

Abilities

• Social

• Emotional

• Academics

Audiology

• Onset of hearing loss

• Assistive listening device

• Date of last hearing test

• Communication mode

Section 6 — Working with colleagues 82

Transdisciplinary practice

Working with colleagues from different disciplines is called transdisciplinary practice.

The following diagram highlights what working in a transdisciplinary way looks like and how it differs from working within the boundary of a discipline (disciplinary), or using knowledge and understandings of more than one discipline (multidisciplinary), or using beliefs and methods of one discipline within another (interdisciplinary), or focusing on an issue within and beyond boundaries with the possibility of new perspectives (transdisciplinary).

Disciplinary

Interdisciplinary

Multidisciplinary

Transdisciplinary

Working in a transdisciplinary way means sharing your expertise with others while at the same time listening to, and acknowledging, the knowledge of others. This process is dynamic, where everyone is valued for what they can contribute to the task at hand and opens the way to developing new perspectives or practices that are situated beyond the disciplines. The focus of this process is on inquiry and creates space for the emergence of new data and new interactions as a result of encounters between disciplines. Therefore, working in a transdisciplinary way with colleagues encourages dialogue and discussion and leads to a shared understanding based on an absolute respect for collaborative and collegial approaches that promote both collectiveness and individuality (Nicolescu 1996, np).

83

One of the key aims of transdisciplinary practice is to focus on the issue which goes beyond the discipline boundaries, which requires the collective thinking and input of all professionals involved. No one discipline holds all the knowledge, instead a collective approach means a more informed outcome. At Aurora School, it is about coming together to support children’s communication and language through play.

One way of illustrating everyone working for the benefit of the child is the model by Nolan, Cartmel and Macfarlane (2014). Here the child is at the centre and is the focus of everyone working together in the Space of Inquiry to achieve positive outcomes for this child.

School leadership

Audiologist

Deaf Educators

Physiotherapist

Early childhood teachers

Speech pathologists

Space of Inquiry

Social Worker

Teacher of the Deaf Psychologist

Families

Occupational Therapists

Section 6 — Working with colleagues 84

Community of practice

Working with colleagues from different disciplines is called transdisciplinary practice. Sometimes this way of working is called a Community of Practice.

A community of practice (CoP) is a group of people who share a common concern, a set of problems, or an interest in a topic and who come together to fulfil both individual and group goals. Wenger (1998), one of the founders of the concept of Communities of Practice, identified three important elements of successful CoPs:

1. a shared subject of interest (for example, a goal for a particular child, or group of children)

2. positive and professional interactions and relationships among members (you and your colleagues working together productively and respectfully)

3. the sharing of what each member knows related to the subject of interest such as knowledge, ideas, tools, documents, and stories.

85

The Aurora School community has determined what a positive, collaborative working environment that will enhance the collective impact on children’s learning and development looks like. This is depicted in the following Figure.

OPEN & CONSISTENT COMMUNICATION

WHO

FAMILIES CHILD WHAT

SHARED VALUES: RESPECT COLLABORATION COMMITMENT

HOW TEAMWORK

Section 6 — Working with colleagues 86

This Figure shows the Aurora School Transdisciplinary Practice Model. This model highlights the principles and practices that enhance working in constructive and collegial ways with staff that translate into positive child outcomes.

COMMUNITY

The aurora school transdisciplinary practice model

The figure above shows that the child or children are at the centre encircled by their families.

Surrounding this nucleus is the WHO, WHAT and HOW of working together described as

WHO is involved?: Educators, Educational Support, Early Intervention, Early Education, Occupational Therapist, Physiotherapist, Audiologist, Psychologist, Social workers, Auslan Educators, Leadership, Parents, Grandparents, Siblings and family friends.

WHAT lists some of the practices that support best outcomes for the child:

• Communication & working together

• Sharing information and strategies

• Advocating for child’s best interest

• Supporting families

• Supporting teachers

• Making links between family members & school such as sharing communication skills with extended family / friends to bring learning into the home

• Holistic practices

• Action research

• Engaging in professional learning

HOW relates to the enactment of effective practice and includes:

• The use of visuals

• Explicit teaching

• Speech/Language therapy

• Auslan/English

• Play-based learning

• Thoughtful and well-informed transitions

• Inclusiveness

87

The grey circle encompassing the Who, What and How, represents the Community partners such as: interpreters, services, Alumni, visitors, placement students, and volunteers.

The next section of the Figure highlights the light rays that are emitted from this tight inner circle. Each light ray represents an important aspect of working together. The following represents:

First light ray: teamwork

This ray depicts teamwork which is the combined actions of the group. Strong teamwork translates to effectiveness and efficiency. Harnessing the collective wisdom of all members makes a strong team.

Second light ray: shared values

Shared values are explicit fundamental beliefs and principles that underlie the culture of an organisation. These values guide decisions and behaviours of all involved. These have been named as:

• Respect: Respect for different perspectives, opinions and ways of working and cultural differences. Acknowledgement (through discussion and action) of each other’s knowledge, skills and experiences. Being open-minded about one’s thinking and the thinking of others. Building professional relationships that promote trust between colleagues

• Collaboration: Collaboration with colleagues, families, and children

• Commitment: Commitment to deaf education and ongoing staff learning

Third light ray: open & consistent communication

Open, clear, and consistent communication is important for the model to be successful.

Open communication is when leadership and other staff in an organization express their ideas, issues, and thoughts with one another in an honest, transparent, and professional manner. This way of communicating supports a sense of authenticity and integrity, essential foundations for true collaboration. Open and honest communication leads more quickly to a mutual understanding and respect for a difference in views, interests, and needs.