14 minute read

POST-ACUTE

from Rep April 21

For providers, being ‘age-friendly’ means listening to the patient

“What’s bothering you today?” or “How do you feel?” are common openers for physicians, nurses and other

caregivers when they meet a patient. What often follows are a quick diagnosis and treatment plan. But some providers are rethinking the process. They’re taking a step back and asking their patients a fundamental question: “What matters to you insofar as your health and life are concerned?”

For some patients, it might be gaining enough strength to walk a block, or controlling pain, or living independently as long as possible. For those with an advanced illness, it could be, “I want to live long enough to see my daughter’s baby,” “or “I’ve always wanted to travel, and now is the time to do it.”

The Age-Friendly Health Systems movement is an initiative to align “what matters” to the patient and their family caregivers at every care interaction. Launched in 2017, Age-Friendly is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States. Until now, it has focused primarily on older adults in the ambulatory or acute-care setting, but proponents believe its strength lies in its application across the care continuum, including long-term and post-acute care.

The 4Ms

Close to 2,000 providers are formally recognized as being “Age-Friendly” by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, says Alice Bonner, PhD, RN, senior advisor for aging at the IHI. The number of nursing homes and other congregate care settings is growing.

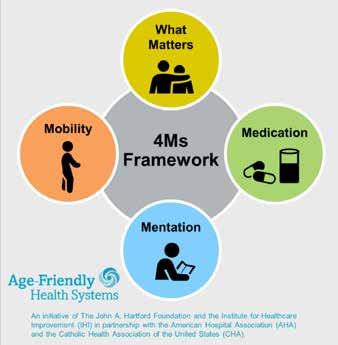

In order to become recognized as age-friendly, the provider must demonstrate a set of four evidence-based elements of high-quality care, known as the 4Ms: What Matters, Medication, Mentation, and Mobility. Some organizations include a fifth – Medical Complexity.

What Matters: Knowing and aligning care with the older adult’s specific health outcome goals and care preferences, including, but not limited to, end-of-life care, and across settings of care.

Medication: Using age-friendly medication that does not interfere with What Matters to the older adult, Mobility or Mentation.

Mentation: Identifying, treating and managing dementia and depression.

Mobility: Ensuring that each older adult moves safely every day to main function and do What Matters to them.

Age-Friendly is effective only if the 4Ms are delivered as a set, according to proponents. Still, “What Matters” is the central tenet from which the others spring. Finding out what matters to the person and developing an integrated system to address it can lower inpatient utilization (54% decrease) and ICU stays (80% decrease), while increasing hospice use (47.2%) and patient satisfaction, according to the Health Resources & Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“4Ms” Framwork of an Age-Friend Health System A framework for care

The 4Ms are a framework to work within, not rigid rules, says Bonner. Healthcare providers have been practicing many of them already, though perhaps not all of them, with all residents, all the time. “But this is about implementing them as a set in hospitals, ambulatory care settings, nursing homes and other settings,” she says.

By implementing the 4Ms across the care continuum, patients can achieve higher functionality and avoid acute care costs, says Donald Jurivich, D.O., chief of geriatrics at the University of North Dakota and program director of Dakota Geriatrics, which partners with skilled nursing facilities and assisted living facilities in North and South Dakota to implement Age-Friendly.

“In ‘What Matters,’ we want to understand the health goals of the older adult,” he says. “We’ve been focused on such things as advanced directives and, in North Dakota, the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, or POLST. But these are end-of-life issues, and we don’t really know the goals of the older adult. Is it to take care of grandchildren? To travel? To do hobbies? We don’t know these things, nor do we document them in the medical record. The point is, once we learn the goals of the patient, it would be well for us to align their care with them.”

An ‘aha’ moment

In September 2020, the Hartford HealthCare Cancer Institute was designated an Age-Friendly Health System. The designation recognized the Cancer Institute’s Comprehensive Oncology and Aging Care at Hartford (COACH) program.

A CLOSER LOOK AT AFINION™ 2 ANALYZER

The Afinion™ 2 Analyzer enables fast and easy quantitative determinations of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR). With its compact size and short test times, the Afinion™ 2 System is ideal for any of your customers that are managing patients with diabetes.

FACTORY CALIBRATED

Each Afinion 2 Analyzer is carefully calibrated during manufacturing and a self-check is automatically performed when the instrument is turned on. No calibration check devices or cumbersome and costly operator calibration is required.

GUIDED TEST PROCEDURE

The analyzer’s simple, 3-step procedure includes a touch display with icons and short messages that guide the operator.

NO MAINTENANCE

The analyzer has no parts requiring periodic replacement.

Recent studies comparing the Afinion™ HbA1c assay to routine and reference laboratory methods have consistently shown a bias close to zero and a coefficient of variation (CV) below 2% (NGSP units).1-5

Test results can be printed or transferred to electronic medical records.

1. Nathan DM, Griffin A, Perez FM, et al. Accuracy of a Point-of-Care Hemoglobin A1c Assay. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;13(6):1149-1153. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1932296819836101. 2. Arnold WD, Kupfer K, Little RR, et al. Accuracy and Precision of a Point-of-Care HbA1c Test. J Diabetes Sci Technol. March 10, 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1932296819831292. 3. Arnold WD, Kupfer K, Swensen MH, et al. Fingerstick Precision and Total Error of a Point-of-Care HbA1c Test. J Diabetes Sci Technol. March 6, 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ pdf/10.1177/1932296819831273. 4. Lenters-Westra E, English E. Evaluation of Four HbA1c Point-of-Care Devices Using International Quality Targets: Are They Fit for the Purpose? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(4):762-770. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1932296818785612. 5. Sobolesky PM, Smith BE, Saenger AK, et al. Multicenter assessment of a hemoglobin A1c point-of-care device for diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Clin Biochem. 2018;61(4):18-22. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/clinical-biochemistry/vol/61/suppl/C. © 2020 Abbott. All rights reserved. All trademarks referenced are trademarks of either the Abbott group of companies or their respective owners. Any photos displayed are for illustrative purposes only. 10005910-01 08/20

“We have been blessed with very active geriatric programs at Hartford HealthCare for many years,” says Christine Waszynski, APRN, coordinator of Hartford’s Inpatient Geriatric Services and NICHE (Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders) program. In fact, Hartford Hospital became a NICHE site in 2003 in order to achieve systematic change to benefit hospitalized older patients. “Age-Friendly isn’t a new concept, but it fits into our mission and core values,” she says. “The 4Ms make it easy to digest, and they are very tangible to our geriatric population.”

“Our goal is for everyone who works at the Cancer Institute to understand the special needs of older adults,” says Mary Kate Eanniello, DN, RN, OCN, director of oncology education and professional development. “AgeFriendly is the perfect tool to help us achieve that.” The key to its implementation has been Rawad Elias, M.D., who came to the Cancer Institute three years ago to serve as its medical director of geriatric oncology, she says.

Elias always had an interest in oncology, but his “aha moment” came about 10 years ago when he read a book on geriatric oncology, he says. His passion for the subject grew through a fellowship and exposure to the late Arti Hurria, M.D., a nationally recognized expert and advocate for elderly patients with cancer, who led the Center for Cancer and Aging at the City of Hope in Los Angeles.

At the Center, Hurria and her team developed a comprehensive assessment of patients to determine a more tailored approach to cancer care, one that could help the patient and provider predict that person’s risk for chemotherapy’s side effects, the impact of treatment on their medications, and their preference regarding treatment, taking into account its impact on the person’s ability to act independently.

Elias looked for a practice setting that would enable him to bring to patients the insights he had gained about geriatric oncology. “I interviewed at Hartford Cancer Institute and found they were just as excited about it as I was,” he says. He joined the Cancer Institute in 2018 and later helped launch COACH. In January 2021, he took on his current position as medical director of geriatric oncology.

COACH features a team of providers who work with each other and the referring oncologist to help older patients achieve what they wish following a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Following the patient’s initial assessment, they might offer psychosocial support, nutritional advice, physical and occupational therapy, guidance from a pharmacist, even help managing household bills.

“We can’t tell the oncologist what to do,” says Elias. But by engaging with oncologists and surgeons, those involved with COACH focus not just on treatment, but on the patient and their quality of life after treatment. “My big message is, ‘Treat the patient, not the cancer,’” he says. “If you focus on the cancer, you link it to the treatment. But when you focus on the patient, you work on what makes sense to them.”

“The most important thing for the Cancer Institute and our patients is that we have a validated tool to use for the initial assessment,” says Eanniello. “If a patient is vulnerable or frail, we tell them. But if they want to live to see their daughter get married, we will be proactive in helping them reach that goal. Nobody wants to do harm to a patient. But without proper tools, like the assessment, it’s difficult to put a workable plan in place.”

Incorporating Age-Friendly

One of the little-known facts about being Age-Friendly is that it actually can save the provider time and money, says Bonner. “It’s not about cutting corners. It’s about redesigning the care processes in a way that eliminates extra steps and unnecessary workflow. That might mean eliminating meds that people don’t need, or parts of the care plan that the person doesn’t want. So it’s not adding work for the staff. It’s redesigning how the staff works.” And in most cases, people are far more satisfied with their treatment.

“We put a lot of passion and energy into this, but passion isn’t enough,” says Elias. A formal structure or framework is needed, such as the COACH assessment tool. “That’s what’s important for sustainability.”

“We have integrated the 4Ms into our standard workflow and with staff who come to us,” says Waszynski. “Our motto is, ‘This isn’t extra work. It’s our work.’”

The Science of Soap Formulation

Prior to publication of the 2002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) hand hygiene guidelines,

soap was the predominant hand hygiene product. While alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) is the primary pillar of hand hygiene today, washing hands with soap and water is recommended primarily when hands are visibly soiled or contaminated with blood or other bodily fluids and when there are outbreaks of Clostridium difficile or norovirus.1 Soap is still a critical part of hand hygiene in healthcare settings and is often not always given as much consideration as it deserves. Soap can have an impact on healthcare workers’ (HCW) skin health. That’s why it’s important to understand how soap works and how choosing a properly formulated soap can make all the difference in helping to maintain proper skin health and giving safer patient care.

Choosing a soap

The general mechanism of action is lifting and suspending oil, dirt, and other organic substances from hands so they can be rinsed down the drain, much like cleaning a dirty dish. Soaps are classified as surfactants (surface active agents) that possess both polar (ionic/hydrophilic) and non-polar (long hydrocarbon/hydrophobic) groups. A soap molecule has a polar head that is water-loving and a non-polar tail that is oil-loving. When water is added, the soap molecules aggregate into tiny formed clusters called micelles. When this happens all the non-polar (oil-loving) tails line up on the inside, excluding the water and attracting the oil and dirt to the inside of the micelle and suspending it there. The polar heads align on the outside of the micelles where the water is and allow the suspended dirt and oil to be washed down the drain. As a result,

soaps are capable of cleaning skin and other substrates by removing both water soluble and water-insoluble dirt from the substrates and suspending them in aqueous, or water-like, solutions.

When choosing between a plain or non-antimicrobial and antimicrobial soap it is important to understand the key differences. With non-antimicrobial soaps, organic substances and some germs are removed by simply using friction from rubbing hands together. This action helps loosen up the bacteria and soils on the hands, allowing them to be rinsed down the drain. With an antimicrobial soap, the same physical mechanism of action for removing germs and soils happens, and any bacteria or germs present are exposed to the antimicrobial active ingredient which attaches to the germs and kills them. The CDC hand hygiene guidelines allow the use of either an antimicrobial or a non-antimicrobial soap. One is not recommended over the other in healthcare.

Key points

It’s important to understand the key differences between a plain or non-antimicrobial and antimicrobial soap: ʯ With non-antimicrobial soaps, organic substances and some germs are removed by simply using friction from rubbing hands together. This action helps loosen up the bacteria and soils on the hands, allowing them to be rinsed down the drain.

ʯWith an antimicrobial soap, the same physical mechanism of action for removing germs and soils happens, and any bacteria or germs present are exposed to the antimicrobial active ingredient which attaches to the germs and kills them.

Understanding the anatomy of skin

To understand how hand hygiene products affect the skin, it is important to understand a little about the anatomy of skin. The top layer of skin, known as the stratum corneum, is made up of mostly dead skin cells, lipids, oils and corneocytes. This paper-thin structure serves as the primary barrier between the body and the environment. Its primary function is to protect the body and to prevent loss of water. The stratum corneum has a brick-andmortar structure that is tightly packed together to form your skin barrier. When washing your hands with soap the micelles attract oils and lipids, as previously mentioned, but they are also attracting and removing the oils and lipids from this top layer of your skin. As these lipids are removed from your skin, they can leave gaps in the brickand-mortar structure through which allergens and germs can to enter. This interruption of the skin’s barrier happens when a HCW over-uses soap and water to clean their hands, and can happen faster if warm or hot water is used when washing. Think of washing butter (similar to the skin’s “mortar”) off of a dinner plate at home. Therefore, it is also important to use cool or lukewarm water when washing hands with soap and water.

Given the impact of soap on the skin, it is critical for healthcare facilities to choose a soap that has been formulated for high in-use settings. Not all soaps are created equal and poorly formulated soaps can be very harsh on the skin, setting up a vicious dry skin cycle that worsens with each soap handwash. In the past, antimicrobial soaps have been less mild to skin than non-antimicrobial soaps; however, the latest generation of antimicrobial soaps can provide both antimicrobial efficacy and improved skin mildness. While there is not specific guidance on the use of either an antimicrobial or a non-anti-microbial soap, it is critical to choose a well-formulated soap with low potential for irritation to help mitigate skin health issues. Selecting the right soap may not be easy, but being wellinformed about the options and key selection factors can help make the process easier.

1. Dubberke ER, Carling P, Carrico R, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Strategies to prevent Clostridium difficile infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(6):628-645.