REDFISH ON DRUGS

The Jose PRO was named in honor of the legendary Waterman and larger-than-life personality Jose Wejebe. This frame builds off the original with six performance additions to help anglers manage sweat, reduce fogging and keep their frames locked in place, even when the water gets rough. This frame celebrates the legacy of our friend and the man who broke barriers in the angling community. He saw the angler in everyone, even those who had never fished before. And he grew the community, making it a more welcoming place. Now we continue in his footsteps and encourage others to do the same when we say: Open Waters with Jose PRO.

Dr. Aaron Adams, Monte Burke, Bill Horn, Jim McDuffie, Carl Navarre, T. Edward Nickens

Publication Team

Publishers: Carl Navarre, Jim McDuffie

Editor: Nick Roberts

Layout and Design: Scott Morrison, Morrison Creative Company

Contributors

Michael Adno

Monte Burke

Mike Conner

Mike Holliday

Chris Hunt

Alexandra Marvar

T. Edward Nickens

Chris Santella

Photography

Tyler Bowman

Marty Dashiell

Dan Diez

Pat Ford

A.J. Gottschalk

Adrian Gray

Dr. Stephen Kajiura

Tom Henshilwood

Jess McGlothlin

Jasiel Morales

Josiah Ness

Robbie Roemer

Nick Shirghio

Carlin Stiehl

JoEllen Wilson

Ian Wilson

Justin Yurkon Cover

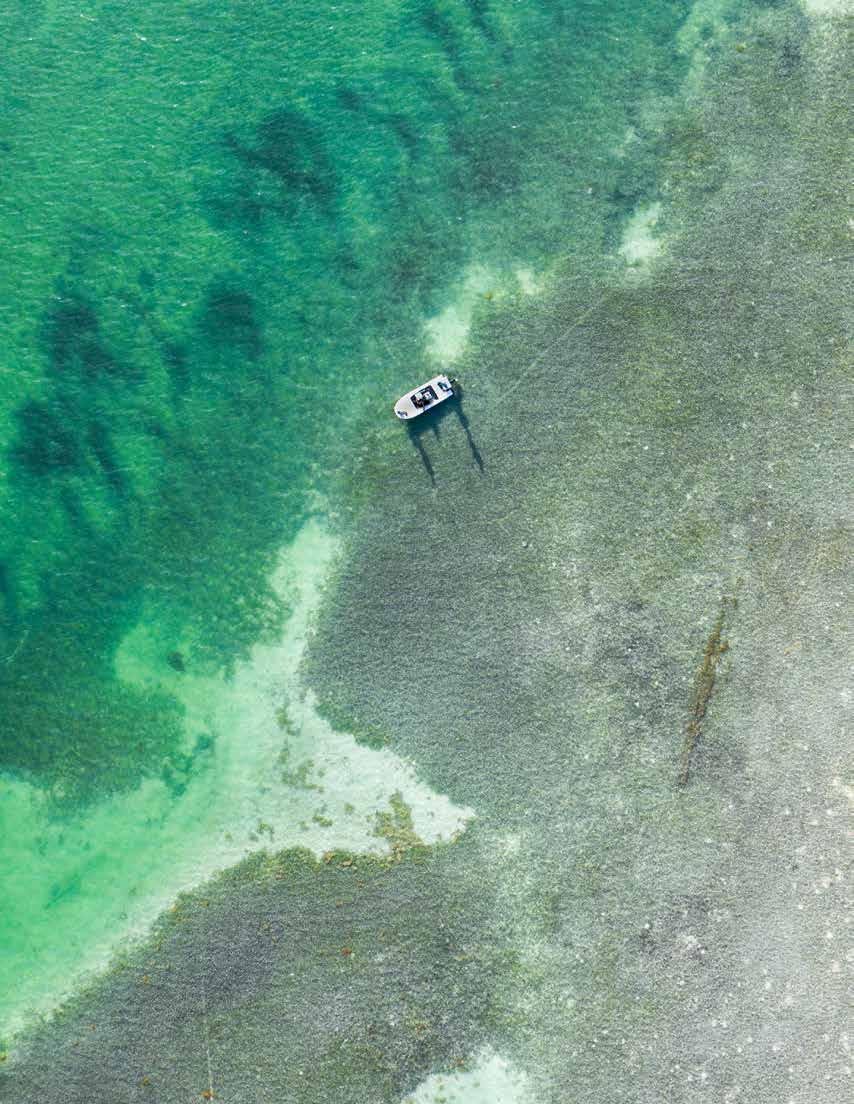

A redfish is released on a seagrass flat in Everglades National Park. Photo: Pat Ford

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal

2937 SW 27th Avenue Suite 203

Miami, FL 33133

(786) 618-9479

Carl Navarre, Chairman of the Board, Islamorada, Florida

Bill Horn, Vice Chairman of the Board, Marathon, Florida

Jim McDuffie, President and CEO, Miami, Florida

Evan Carruthers, Treasurer, Maple Plain, Minnesota

John D. Johns, Secretary, Birmingham, Alabama

Tom Davidson, Founding Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Harold Brewer, Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Russ Fisher, Founding Vice Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Jeff Harkavy, Founding Member and Circle of Honor Chair, Coral Springs, Florida

John Abplanalp Stamford, Connecticut

Rich Andrews

Denver, Colorado

Stu Apte Tavernier, Florida

Rodney Barreto

Coral Gables, Florida

Dan Berger

Alexandria, Virginia

Adolphus A. Busch IV Ofallon, Missouri

John Davidson

Atlanta, Georgia

Greg Fay Bozeman, Montana

Advisory Council

Randolph Bias, Austin, Texas

Charles Causey, Islamorada, Florida

Don Causey, Miami, Florida

Scott Deal, Ft. Pierce, Florida

Paul Dixon, East Hampton, New York

Chris Dorsey, Littleton, Colorado

Chico Fernandez, Miami, Florida

Mike Fitzgerald, Wexford, Pennsylvania

Pat Ford, Miami, Florida

Christopher Jordan, McLean, Virginia

Bill Klyn, Jackson, Wyoming

Clint Packo, Littleton, Colorado

Jack Payne, Gainesville, Florida

To conserve and restore bonefish, tarpon and permit fisheries and habitats through research, stewardship, education and advocacy.

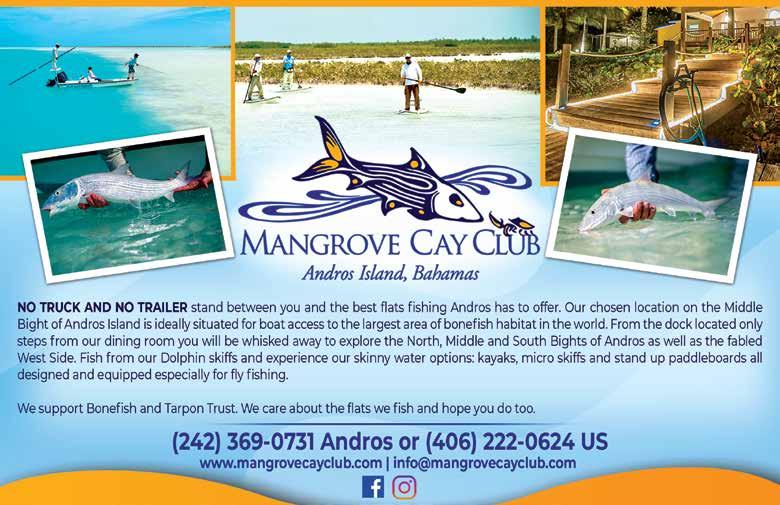

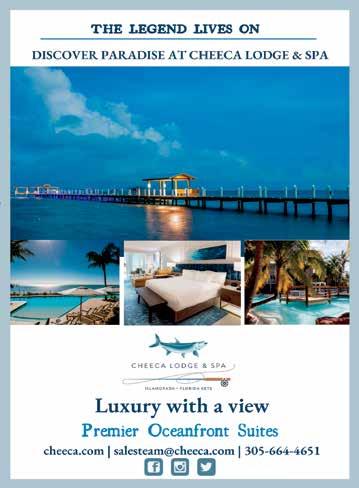

Cheeca Lodge & Spa Islamorada, FL

Dr. Tom Frazer Tampa, Florida

Doug Kilpatrick Summerland, Florida

Jerry Klauer New York, New York

Dr. Michael Larkin St. Petersburg, Florida

Thorpe McKenzie Chattanooga, Tennessee

Wayne Meland Naples, Florida

Ambrose Monell New York, New York

Sandy Moret Islamorada, Florida

Chris Peterson, Titusville, Florida

Steve Reynolds, Memphis, Tennessee

Ken Wright, Winter Park, Florida

Honorary Trustees

Marty Arostegui, Coral Gables, Florida

Bret Boston, Alpharetta, Georgia

Betsy Bullard, Tavernier, Florida

Yvon Chouinard, Ventura, California

Matt Connolly, Hingham, Massachusetts

Marshall Field, Hobe Sound, Florida

Guy Harvey, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Steve Huff, Chokoloskee, Florida

James Jameson, Del Mar, California

John Newman Covington, Louisiana

David Nichols

York Harbor, Maine

Al Perkinson New Smyrna Beach, Florida

Dr. Jennifer Rehage Miami, Florida

Jay Robertson Islamorada, Florida

Rick Ruoff

Willow Creek, Montana

Adelaide Skoglund

Key Largo, Florida

Noah Valenstein Tallahassee, Florida

Michael Keaton, Los Angeles, CA / MT

Rob Kramer, Dania Beach, Florida

Huey Lewis, Stevensville, Montana

Davis Love III, Hilton Head, South Carolina

George Matthews, West Palm Beach, Florida

Tom McGuane, Livingston, Montana

Andy Mill, Aspen, Colorado

John Moritz, Boulder, Colorado

Johnny Morris, Springfield, Missouri

Jack Nicklaus, Columbus, Ohio

Flip Pallot, Titusville, Florida

Paul Tudor Jones, Greenwich, Connecticut

Bill Tyne, London, United Kingdom

Joan Wulff, Lew Beach, New York

The discovery of pharmaceutical contaminants in redfish throughout Florida underscores the urgent need for wastewater treatment reform. Alexandra Marvar

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is collaborating with Florida Keys fishing guides to support a set of science-based recommendations for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary’s Restoration Blueprint. Michael Adno

Unsustainable commercial fishing for menhaden in the Gulf of Mexico and mid-Atlantic poses a major threat to tarpon and other valuable gamefish. T. Edward Nickens

As Florida guides report an increase in shark interactions, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and resource managers seek science-based solutions. Mike Conner

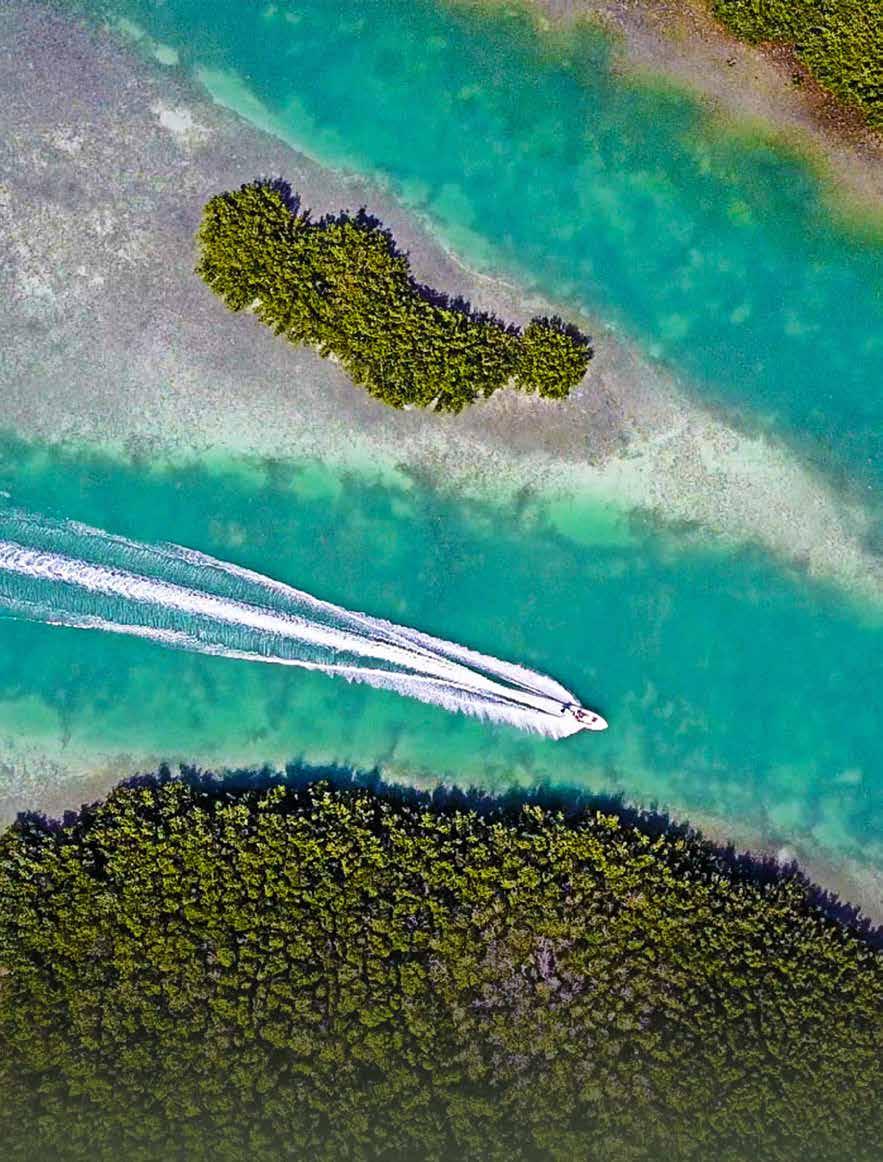

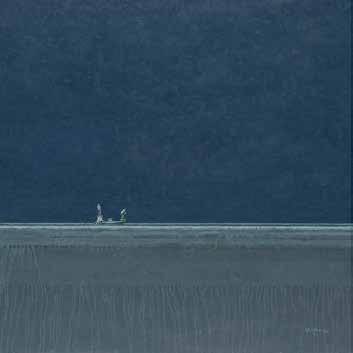

Anglers fish a flat in the Florida Keys. Photo: Tyler Bowman

As the 7th International Science Symposium came to a close, one message was clear. If we care about the flats fishery, and if we want to conserve it, then science has shown us the way—improve water quality, conserve coastal habitats, and ensure effective management.

The answer seems simple enough, but we know the process of change rarely unfolds in a straight line. In this case, the way forward will continue to be challenging as competing interests vie for access to the resource. Similarly, we won’t be given the luxury of time, or the choice to focus on one challenge to the exclusion of all others. Instead, our approach will need to be integrated and comprehensive, working on all of them simultaneously and with everything that science can bring to the fight!

This approach is readily evident in the scope of work across BTT’s research and conservation programs and can be seen again in this issue of Bonefish & Tarpon Journal.

BTT has long supported Everglades restoration, and our commitment is unwavering. It was gratifying to take part recently in the groundbreaking ceremony for the long-awaited EAA Reservoir—a major and hard-fought centerpiece in the restoration plan to send water south to Florida Bay. The occasion reminded us of our past trips to Tallahassee and Washington, DC, to advocate for the project’s authorization and funding, our calls to action, and our collaboration with Now or Neverglades partners to promote the coalition’s petition. Yet, after marking the occasion on a remote corner of ground south of Lake Okeechobee, we returned to unfinished business in the Everglades and, simultaneously, in response to new water quality challenges emerging across Florida.

Case in point, following last year’s alarming report of pharmaceutical contaminants in bonefish, BTT will soon release the results of a similar study on redfish. Our scientists sampled redfish from nine major estuaries statewide looking for traces of 95 common psychoactive and heart medications, antibiotics, pain and allergy relievers, opioids, and other medications. The results? Drugs were found in nearly every sample—94 percent of the 113 fish tested—and at higher and concerning levels in half of the fish tested.

These results make clear that the problem we first documented is not limited to bonefish or to the waters of South Florida and the Keys. Rather, pharmaceutical contamination is widespread across Florida’s marine habitats—a dire consequence of a wastewater infrastructure not up to the task. In her article, “No Time to Waste,” Alex Marvar reports from the 7th International Science Symposium on both the causes and remedies. Scientists and policymakers agree that it isn’t too late to save the state’s fisheries from pharmaceutical contamination—at least, not yet. But action is needed now, especially given the favorable opportunities to capitalize on state and federal funding for infrastructure.

The ever evolving and always complex water quality issues such as these remain our top priority at BTT. If we lose our water, we lose our fishery! But there’s more to the story—another perspective that should be of equal concern to flats anglers. Even if we were able to restore our waters to an earlier pristine state, we could still run the risk of losing our fishery. Yes, even with all of our current water woes addressed, the flats fishery would still face threats at scale stemming from the loss of coastal habitats that are so essential to sustaining the fishery. Likewise, we can’t assume that fishery management approaches from an earlier time will suffice in the face of the dynamic environment of today, from a changing climate to increased pressure on the resource. Our friend Sandy Moret speaks often and eloquently about the “weight of humanity” on the water.

In response, BTT has expanded its habitat restoration and

Carl Navarre, Chairman

Jim McDuffie, President

Jim McDuffie, President

conservation efforts in recent years to include the largest mangrove restoration project in Bahamas history, restoration of a creek system on East Grand Bahama blocked for decades, planning to restore two tracts at Rookery Bay on Florida’s Gulf Coast, and the habitat-related recommendations advanced last year in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS) plan.

Mike Adno reports in “Charting the Way Forward” about how BTT, the Lower Keys Guides Association and the Florida Keys Fishing Guides Association collaborated on their responses to the Sanctuary’s Restoration Blueprint, with a focus on preventing habitat loss and degradation, improving water quality and reversing fishery declines. This represents the first update to the Sanctuary’s management plan in 15 years, and decisions codified in the revised plan will potentially impact the flats fishery for decades to come.

Habitat loss is also evident in Chris Santella’s piece, “BTT Expands Presence in Belize.” Alongside the country’s angling community, BTT has advocated against irresponsible development at Blackadore Caye, Cayo Rosario, and Deadman’s Caye at Turneffe Atoll. The groundswell of opposition by guides, lodges and other stakeholders is enabling BTT and its partners to put a bright spotlight on unwise coastal development and its impacts on the fishery.

As with the unprecedent changes in water quality and habitat over recent decades, we have also witnessed how environmental changes and resource use have necessitated changes in fishery management. BTT’s research helped make the case for a spawning season closure at Western Dry Rocks (WDR) in the spring of 2021. Our work continues today through monitoring at WDR and three other unprotected sites used by spawning permit. The resulting data will enable the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) to make informed decisions when this management action sunsets after seven years.

In this issue, you will also read about two other management issues of growing concern to BTT. In his excellent article, “The Pogy Problem,” T. Edward Nickens explains how menhaden, a critically important forage fish for many species, including tarpon, are being exploited by two foreign corporations—and how BTT is partnering with other conservation leaders to advocate for management changes. And in “The Uninvited Guest,” fishing guide Mike Conner writes about angler interactions with sharks and the subsequent depredation of flats species, which have many anglers calling for a broader discussion on management actions and ethical practices by anglers. As this edition of the Journal goes to press, BTT has just announced a new project to research shark-angler interactions in the Keys at different locations and with different fishing methods.

We hope you will find this issue of Bonefish & Tarpon Journal informative, entertaining, and emblematic of your support and commitment to the cause. And we hope it will renew your own steadfast resolve to help BTT deliver the grand slam of flats conservation—clean water, intact habitats and effective management!

Yonder™ 750 mL Water Bottle

NOAA Fisheries Biologist Dr. Michael Larkin and Dr. Jennifer Rehage, a coastal fish ecologist and associate professor at the Institute of Environment at Florida International University, have been elected to the Board of Directors of Bonefish & Tarpon Trust.

“Drs. Larkin and Rehage know BTT and the flats fishery well,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “Their commitment to our mission and their expertise as scientists will be valued at the board table.”

Dr. Larkin grew up fishing in the Northeast but moved south to pursue a marine science degree at the University of Miami. After receiving the Bachelor of Science, he accepted a job focusing on reef fish surveys with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute in the Florida Keys, where he developed a passion for fishing for bonefish and tarpon. At that time, the University of Miami was seeking graduate students for its newly formed collaboration with Bonefish

and Tarpon Unlimited (which later became Bonefish & Tarpon Trust). Larkin joined the UM-BTT collaboration for graduate school and worked on numerous projects, including satellite tagging of tarpon and bonefish tagging, tracking, and age-and-growth studies.

“I am excited to return to Bonefish & Tarpon Trust,” Dr. Larkin said. “It’s amazing to see how far the organization has grown since I was last involved. I look forward to joining BTT’s Board of Directors and continuing to advance the science.”

After receiving his doctoral degree from the University of Miami in 2010, Dr. Larkin joined NOAA Fisheries, where he works in the management branch, analyzing fisheries data to guide management decisions. Dr. Larkin resides in St. Petersburg, FL with his wife and two children.

Dr. Rehage’s research examines how water decisions and water quality issues

affect coastal fishes and the valuable recreational fisheries they support. Over the past 15 years, she has studied snook, juvenile tarpon, Crevalle jack, Florida largemouth bass, and bonefish throughout the Everglades and coastal Florida, and collaborated with anglers and fishing guides to better understand recreational fisheries and their dependency on water management and healthy habitats.

In partnership with BTT and collaborators, Dr. Rehage’s research team has been examining the causes of bonefish population decline as well as the threat of pharmaceutical contaminants to our coastal fisheries, focusing on bonefish and most recently redfish. Dr. Rehage grew up in Uruguay, where, as a child, she spent time at her grandfather’s fishing club.

“I am honored and delighted to help BTT bring science to the fight,” said Dr. Rehage. “This is super meaningful and I am grateful for the invitation.”

United States veterans from Project Healing Waters recently joined BTT staff, partners, and bonefish guides to plant 1,400 mangroves on Abaco as part of BTT’s Northern Bahamas Mangrove Restoration Project, which will revitalize important bonefish habitat and bolster coastal resilience for local communities. The largest effort of its kind in Bahamas history, the five-year project seeks to plant 100,000 mangroves in areas of Grand Bahama and Abaco hardest hit by Hurricane Dorian, with more than 26,000 mangroves planted to date.

BTT Vice President Kellie Ralston and board member Noah Valenstein joined Governor Ron DeSantis on December 1 in Miami where he announced seven awards totaling $22.7 million to support water quality improvements and protection of Biscayne Bay, which provided vital habitat for bonefish, tarpon, permit, and numerous other species. Projects funded through the Biscayne Bay Grant Program include septic to sewer conversions, stormwater management and wetland restoration in areas surrounding Biscayne Bay, Florida’s largest estuary with a direct connection to Florida’s Coral Reef. BTT advocated for a number of these projects and worked with the DeSantis Administration to secure funding.

Atlanta area friends enjoyed an afternoon of shooting on October 26 followed by a discussion between renowned angler Andy Mill of the Mill House podcast and Monte Burke, the acclaimed author

Since 2016, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust has been working with anglers and guides as citizen scientists to identify tarpon and snook nursery habitats and classify them as natural or degraded. Natural habitats are able to function as productive nurseries for juvenile fish, and require protection. Degraded sites are in need of habitat restoration. To prioritize these sites for protection and restoration, BTT is creating a Vulnerability Index (VI), which uses GIS mapping data layers for nursery habitat sites overlaid with data on current and potential development locations, freshwater flows, and land ownership (public or private) to categorize sites as High, Medium or Low vulnerability.

The current focus is Charlotte County, Florida, near the tarpon fishing capital of the world—Boca Grande. BTT recently partnered on a grant proposal with Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), Coastal and Heartland National Estuary Partnership (CHNEP), and Charlotte County through NOAA’s Actionable Science Program that would fund collection of data layers needed to construct the Vulnerability Index and package it in a way that can be used by Charlotte County’s land use planning department. Once this VI is in place, BTT plans to expand to other regions in the state where sportfish nursery habitat is at risk.

oceanographic models to simulate where bonefish larvae in the Bahamas are transported after spawning, thus linking an important spawning location and places to consider for juvenile habitat protections. The computer simulations are the first to link spawning locations and nursery areas across vast spatial scales that would not be possible using traditional fisheries surveys. This works builds on previous research that linked adult bonefish home ranges and pre-spawning aggregation locations, which informed the creation of new protected areas in The Bahamas. Additional research determined the spawning patterns of bonefish, showing they spawned offshore in deep water at night.

These important new findings suggest that additions are needed to the existing Bahamas’ protected area network to further conserve bonefish populations. The new areas of concern are in the Moores Island area of Abaco, the central-most eastern islands of the Berry Islands, and North Eleuthera. Additionally, existing national parks in the Marls of Abaco, North Shore/The Gap of Grand Bahama, and the Joulter Cays north of Andros should be expanded. The Bahamas’ existing protected areas already protect nearly 86.5 billion acres of sea and land. But the national park expansions suggested by this study would add additional marine habitat that is targeted at the bonefish fishery, and for the first time ever, conservation of bonefish nursery habitats—the foundation of a healthy fishery.

2022 Grand Champions

Swamp Guides Ball

Luke Krenik and Capt. Eli Whidden

March Merkin Permit Tournament

Jose Ucan and Capt. Justin Rea

Golden Fly Tarpon Tournament

Bart Knellinger and Capt. Bear Holeman

Don Hawley Tarpon Tournament

Mark Weeks and Capt. Andy Thompson

Gold Cup Tarpon Tournament

Dave Preston and Capt. Luis Cortes

Del Brown Permit Tournament

Mike Ward and Capt. Brandon Cyr

Herman Lucerne Biscayne Legends Classic

Collin Ross and Rick DePaiva

Herman Lucerne Memorial Backcountry Fishing Championship

Andy Yaffa and Capt. Jared Raskob

Islamorada Invitational Fall Fly Bonefish Tournament

Robbie Binder and Capt. Eli Whidden

Recently published research from Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and Florida Atlantic University used advanced computer

Cheeca Lodge & Spa All-American Backcountry Fishing Tournament

Jim Bokor Jr. and Capt. Richard Black

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s 7th International Science Symposium & Flats Expo was held on November 4-5, 2022, at the PGA National Resort in Palm Beach Gardens, FL. Presented by Costa Sunglasses, the triennial event brought together stakeholders from across the world of flats fishing—marine scientists, resource managers, industry leaders, and the angling community—to share information, collaborate, and learn from one another to advance flats fishery conservation in the Southeastern US, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea. The mix of attendees and diversity of presentations and expert panels exemplified the Symposium’s theme of Conservation Connections, with an emphasis on addressing known fisheries management needs with actionable science. The two-day program featured science presentations and discussion panels by BTT and its collaborating scientists on important research and conservation topics, including the urgent need to improve water quality and wastewater treatment infrastructure in Florida, and to protect and restore threatened habitats throughout the range of bonefish, tarpon, and permit in this hemisphere.

Meanwhile, the fishing panel discussions featured top anglers

and guides, including Steve Huff, Brandon Cyr, Rick Ruoff, and Bahamian bonefishing legend Ansil Saunders, who shared their winning strategies for success on the flats and underscored the need for anglers to support conservation. The well-attended Youth Panel provided the next generation of anglers the opportunity to discuss their plans for the future of the sport and their efforts to ensure the sustainability of the flats fishery. The Symposium also included fishing and fly-tying clinics and the popular Art + Film Festival, which showcased a diverse array of paintings, sculptures, and the latest fishing and conservation short films.

At the Symposium’s expanded Flats Expo, representatives from 60 of the leading boating and fishing brands and lodges were on hand to share information about their latest products and packages and their corporate commitment to conservation with the hundreds of participants in attendance. The Symposium concluded with a special evening celebration to commemorate BTT’s 25th Anniversary and recognize Circle of Honor inductees Matt Connolly, Sandy Moret, Chico Fernandez, Dr. Andy Danylchuk, and Dr. Gordy Hill for their many enduring contributions to the conservation of our shared flats fishery.

On the heels of chilling new research into the health of Florida’s redfish population, an international cohort of researchers says it isn’t too late to save the state’s fisheries from pharmaceutical contaminants—at least, not yet.

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

In back-to-back studies into two of Florida’s most important sportfish, researchers found that behavior-modifying drugs meant for humans are leaching into coastal waters—and messing with aquatic life. At Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s recent International Science Symposium & Flats Expo, experts traveled from as far away as Sweden to present new findings on the presence of chemical substances—from caffeine to acetaminophen, antidepressants to opioids—up and down the food chain, from predators like bonefish and redfish to crabs, shrimp, and barnacles—and even seagrass—all across the state.

In the summer of 2022, researchers from Dr. Jennifer Rehage’s Coastal Fisheries Lab at Florida International University, with the help of expert fishing guides, set out to catch redfish from nine major Florida estuaries in order to test them for 95 common psychoactive and heart medications, antibiotics, pain and allergy relievers, opioids, and other medications.

Catching the individual redfish didn’t always come easy— particularly in the Indian River Lagoon—but the FIU team, including lab manager Andy Distrubell and graduate students Nick Castillo and Shakira Trabelsi, caught their target number in

Redfish are an important part of Florida’s recreational saltwater fisheries, which are worth more than $11 billion annually.

each fishery and sent plasma and muscle tissue across the Atlantic to Umeå, Sweden.

There, their collaborators, including Dr. Tomas Brodin, a professor of behavioral ecotoxicology at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, tested the samples. Rehage’s team in Miami anxiously awaited the results, wondering how they’d measure up to the team’s 2021 BTT study on pharmaceutical contaminants in Florida Keys bonefish.

When the numbers came back, they learned Florida redfish didn’t have as many pharmaceuticals as bonefish. But that’s where

the good news ended, Rehage said. Drugs were found in nearly every sample—94 percent of the 113 fish tested—across all nine fisheries and when found, the levels were high and concerning in half of the fish tested.

What really piqued Distrubell’s interest was that, according to the data, different estuaries seemed to specialize in different contaminants. In the Everglades: caffeine. In Apalachicola: an opioid painkiller often prescribed to patients after a surgery, tramadol. Other drugs, like cholesterol-lowering ezetimibe, were “scattered everywhere,” he said.

Meanwhile in Umeå, Brodin said that while redfish numbers may have been a little less extreme than in the previous bonefish investigation, the samples were still raising eyebrows among his team: “We are actually re-running a few samples now from one redfish that had extremely high levels of caffeine,” Brodin noted. “We want to know if it’s really possible. Have they been drinking Cuban coffee or something? We’ll see.”

The future of these species could lie in these data. Fish have some of the same key receptors in the brain and body as humans do, and drugs affect their behavior in some surprisingly similar ways, Brodin explained. In 2013, he and colleagues published a groundbreaking study on the behavioral changes in perch exposed to drugs such as a benzodiazepine called oxazepam, with an eye to activity, sociality, and boldness. The data showed that when exposed to the anti-anxiety medication, the fish became less social and tended to take more risks.

Since that revelation, human drugs and their associated behavioral changes have been studied in fish, such as European hatchery salmon. The problem of pharmaceutical contamination in marine species is much more widespread than previously believed, Brodin said, and the effects could influence everything from predation to migration to spawning—key behaviors that have

a bearing on entire ecosystems.

Meanwhile, what happens to the substances themselves once they trickle into waterways and oceans? How far can they travel? How long do they last? These are big unknowns, Rehage explained.

“Only a small number of the substances we are testing for have information about half-life,” she said. “What’s their persistence in the marine waters? Nobody knows. That’s really scary.” Meanwhile, the amount of contamination flowing from land to sea is ticking upwards year after year as a growing number of people around the world take pharmaceuticals and new drugs are constantly being added to the mix.

“We have this tremendous amount of production of pharmaceuticals,” she said, “and they’re really important to our quality of life, but we need to start thinking about: ‘How do we make them so they don’t pollute our environment and have side effects on wildlife?’ And if we’re not going to make them better, we need to clean them up.”

Is there more to learn about pharmaceuticals and fish than the studies so far have been able to reveal? Definitely. Why are the otoliths (the calcium ear “stones”) of the redfish Distrubell and Dr. Aaron Adams caught in Indian River estuary different from

all their other redfish samples? What do benzos do to bonefish breeding behavior? Are these pharmaceutical cocktails harmful to the health of reds and bones? Are herons and other marine birds across the Everglades hopped up on caffeine? What about sea turtles? Dolphins? Manatees? Only further study can get to the bottom of these questions, but according to BTT Director of Science and Conservation Dr. Aaron Adams, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and other research entities have already gathered the data they need to see there is a big problem—and to understand what needs to happen to address it: more and better wastewater treatment.

This widespread pharmaceutical contamination across Florida’s marine habitats is just one dire consequence of the state’s current wastewater infrastructure, which is being increasingly challenged by everything from sea level rise and tropical storms to rapid population growth and increasing urban density, Adams said. It’s a challenging situation. At this point, Adams said, “asking for more research is delaying the inevitable.” Right now, Florida needs action.

It’s time to clean up Florida’s water, and Adams says next steps are clear: the state needs to install upgraded water treatment technology in existing water treatment plants that can remove pharmaceuticals and other contaminants (like PFAS), bacteria and viruses, and more from treated water.

“Fixes have already been found,” he said. “These retrofits have already been tested and implemented in Sweden, Switzerland and Germany. It’s not a quick fix, and at this point it will be expensive. But we can’t really afford to not address this problem.”

Within four years of Brodin and team’s 2013 study on contaminants and perch, work was already underway to remediate the problem in Sweden. Wastewater treatment plants across the country, with the help of Sweden’s environmental protection agency, had pulled together plans and funding for pilot studies on processes like ozonation, granular activated

carbon filtration and more. As of 2022, approximately eight fullscale retrofits of wastewater treatment facilities are already in operation, Brodin said, yielding “clear positive effects on certain, more sensitive aquatic species.”

These positive outcomes include an inspiring population bounce-back among some of key food resources for fish like mayflies and caddisflies, which are also among the world’s most threatened insect species.

“The methods are out there,” to clean up Florida’s marine environment, Brodin said, “and I think Florida has a unique opportunity to be at the forefront of North America.”

According to BTT VP for Conservation and Public Policy Kellie Ralston, the state is already laying the groundwork for forwardthinking solutions like these.

“Statewide, we’re at $300 to $400 million in the last four years towards water resources and Everglades restoration projects,”

Ralston said. “It really is kind of unprecedented. With significant federal contributions, there’s a lot of momentum to tackle these challenges.” Measures like a new and expanding wastewater grants program and other investments in modernizing wastewater infrastructure are also underway. And the new redfish study could shed light on a roll-out strategy that will have the biggest water quality impacts.

“The redfish data indicate that some specific locations could be prioritized over others,” Ralston said, citing comparatively higher numbers and higher concentrations in Tampa and Apalachicola, while previous data from the bonefish study pointed to Biscayne Bay as another “hotspot,” she added.

Besides upgraded water treatment facilities, moving more of Florida’s wastewater into treatment facilities, rather than into leaking septic systems, is critical. The Florida Keys made the switch from septic to sewer systems transporting wastewater to treatment plants. The Keys started the conversion 20 years ago, and the major effort was completed just a few years ago. According to available data, this has already brought about lower levels of hazardous nutrient and fecal markers—along with observations by community members and fishing guides on improved water clarity, fish health, biodiversity and more. However, even in the Keys, the wastewater treatment plants do not include technology needed to remove pharmaceuticals and other contaminants.

At a minimum, other communities need to follow the Keys’ lead, retire ancient leaking septic systems, and convert to updated and innovative wastewater treatment systems that address existing pollutants as well as the newly identified pharmaceutical residues. Statewide, one in three households use septic systems, with over 100,000 septic systems in Miami-Dade County alone. “It’s great to see this growing realization of the need to address Florida’s water quality and habitat issues,” Adams said. “We’ve had a great start, but a lot more investment is needed.” Accordingly, BTT will continue to push for increased funding and policy changes

to address these issues. Right now, the organization is actively seeking public and private partners to retrofit one or more waste treatment facilities as a proof of concept.

“We have the knowledge to do it,” Adams said of tackling chemical contamination along Florida’s coast. “We just need the dedication—and the funding—to get it done.”

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and the FIU Coastal Fisheries Lab wish to thank the following guides and anglers for their invaluable assistance with the Redfish Pharmaceutical Contaminants Study.

Danny Allen

Rami Ashouri

James Beers

Jim Brown

Frank Catino

Don Downs

Josh Greer

Chris Hong

Jason Kendall

Tom King

Scott MacCalla

Gary Malstrom

Hayden Malstrom

Andrew Marks

Brandon McGraw

Cristian Minami

Anthony Morgan

Chad Osteen

Dustin Pack

Travis Pack

Joe Tanksley

Troy Weaver

David White

Mike Yankee

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is collaborating with Florida Keys fishing guides to support a set of science-based recommendations for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary’s revised management plan, known as the Restoration Blueprint.

BY MICHAEL ADNO

BY MICHAEL ADNO

For every mile you drive in the Keys, the landscape talks. The ground points back to the Pleistocene when a coral forest rose between the Florida Straits and the Gulf of Mexico. Living coral grows just a stone’s throw offshore. And the water animates the place, drawing people to the Keys in the millions year by year. As Rachel Carson wrote of the Keys in 1955, “There is a tropical lushness and mystery, a throbbing sense of the pressure of life.” Today, that resource falls within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), a tropical archipelago managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—larger than the states of Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

Since 1990, in cooperation with the State of Florida, the Sanctuary has been responsible for managing that vast resource, which includes four national wildlife refuges, six state parks, three aquatic parks, and two of the country’s earliest national marine sanctuaries. Now the Sanctuary management plan is being reworked through a collaborative initiative called the “Restoration Blueprint” to better protect the place.

From the northern edge of Biscayne Bay National Park, the

Sanctuary first forms a thin vein that falls south before enveloping the backcountry of the Upper Keys along the edge of the Everglades National Park. As it moves west, it fans out from the barrier reef running along the southern edge of the Keys to the rim of the Gulf until it reaches the Dry Tortugas along its western boundary. Within the 3,300 square miles, 6,000 different species of flora and fauna live alongside 80,000 human residents and the third largest barrier reef in the world.

The last time the Sanctuary amended the management plan was 15 years ago, and since 2007, the threats to the Keys have only grown more urgent with an exponential increase in tourism and habitat loss, and declines in water quality. Degradation of the island chain’s unique coral reef prompted creation of the State’s Pennekamp Reef preserve in 1960 followed in 1972 by the first federal marine unit: the Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary. Subsequently a series of large vessel groundings on the Keys reef provided the impetus for a broader federal marine unit (with authority to order large vessels away from the reef), which

was established in 1990. Now the problems afflicting the reef, and other Keys’ waters and fish habitat, include water quality and an explosion in boating use.

During the past year, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust worked with the Lower Keys Guides Association (LKGA) and the Florida Keys Fishing Guides Association (FKFGA) to better understand the Sanctuary’s Restoration Blueprint and how it would affect the flats fisheries throughout the Keys. Simply put, the coalition wanted to protect those habitats while retaining responsible access for guides and anglers in a series of recommendations they ultimately made to the Sanctuary.

“We have too many people loving our resource to death,” said Dr. Ross Boucek, BTT’s Florida Keys Initiative Manager. “We need more responsible management in the Keys.” In broad strokes, it’s as straightforward as placing more markers to help users navigate, reshaping boundaries for idle/no motor zones, and including adaptive management in the Blueprint.

Over the last decade, Monroe County has seen exponential tourism growth, increased cruise ship traffic, and an immense

uptick in recreational boat users, especially in the span of the pandemic when every vessel in the island chain seemed to be in use. “We’re long overdue for some management updates,” said Kellie Ralston, BTT’s Vice President for Conservation and Public Policy. As ever, the question for her was: How do you address all the folks’ desires and package that as policy? “The zoning proposals that we have put forward in our recommendations still allow for reasonable and responsible access almost everywhere,” she said. “There were only a few instances where we were supportive of no access areas because of resource concerns.”

When Dr. Boucek sat down with members from the LKGA and FKFGA, they looked over the Keys flat by flat, discerning which flats were eaten up by prop scars and which tarpon lanes were constantly run over by boats, and decided how to prioritize protections. “We listened,” Dr. Boucek said, “wrote it all down.” And that’s what formed the heart of the 74-page document of suggestions that BTT and the guides associations sent to the Sanctuary last fall.

Area by area, they laid out where critical habitats are found

throughout the Keys for permit, bonefish, and tarpon. The LKGA and FKFGA lent BTT the perspective of those absorbed every day in the resource, and BTT coupled that local knowledge with its science-based understanding of spawning behavior, migratory patterns, and feeding activity. What shook out after all that back-and-forth was a set of suggestions that were tailored to conserve crucial habitats for bonefish, permit and tarpon throughout the Keys.

The process began when the guides associations tapped their members’ understanding of the rhythms of the places they fish, discerning where fish swim and when, what obstacles they encounter, and the changes witnessed over time. That deep well of local ecological knowledge was collected and inevitably distilled. From there, in meetings, at marinas, and across the table, members shared that hard-earned knowledge with BTT, who used the accounts alongside its own data from long-term studies to figure out just what was at stake and how the Sanctuary could best address the declining fish populations, water quality, and habitat loss in the next iteration of its management plan.

Precedents for the BTT, LKGA, and FKFGA Restoration Blueprint proposals were the seasonal closure of Western Dry Rocks and the no motor zones in the Everglades National Park—both the product of a close collaboration between users and managers to conserve fisheries and vital habitats. Pointing to those successful management initiatives, Captain Andrew Tipler, President of the LKGA, feels hopeful about the opportunity not only to preserve the resources in the Florida Keys but to see them improve. He likened the reasonable restrictions included in the Blueprint proposal to the regulations in National Parks where some sites are only accessible seasonally, by trail, or rather have a specific means of reaching them to protect them from unfettered access or neglect. The groundswell of conservation efforts bound up in just this process alone bolstered Tipler’s hope as he acknowledged the involvement of the American Sportfishing Association, the Coastal Conservation Association Florida, and the International Game Fish Association among a handful of organizations that have become intimately involved in the Keys community, too.

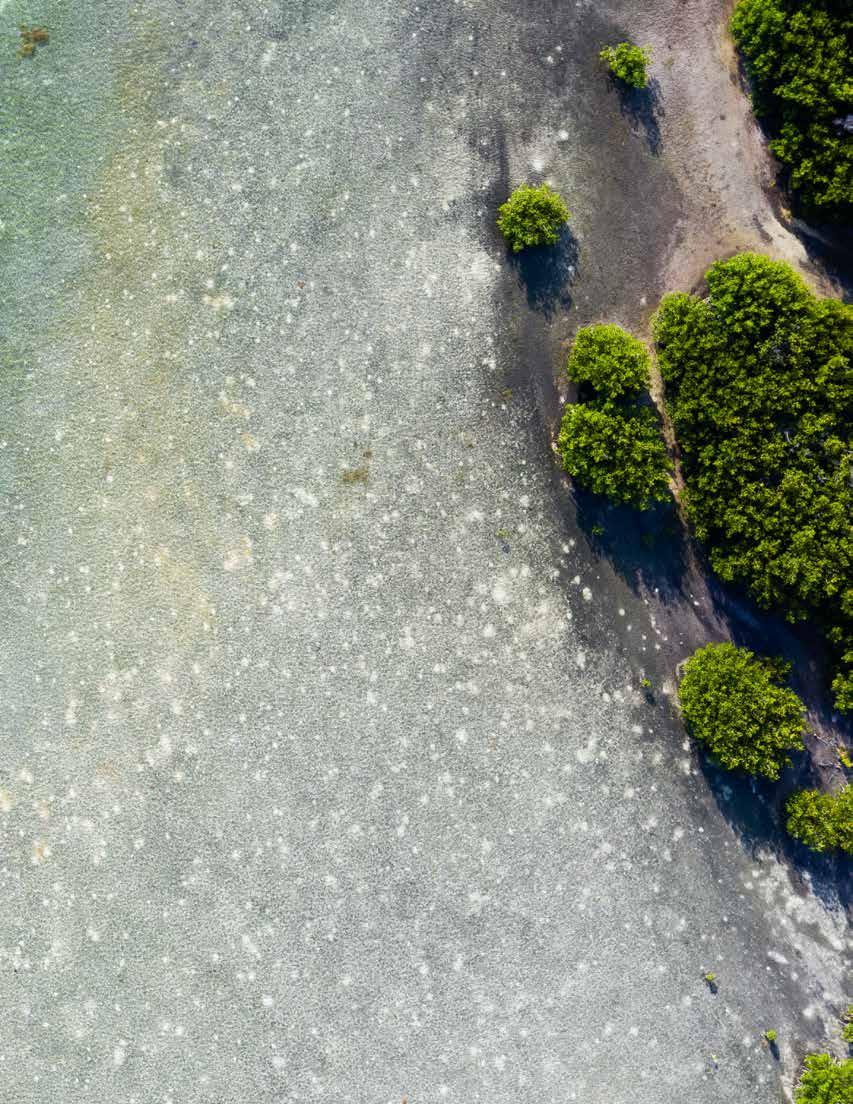

For Captain Eric Herstedt, a member of FKFGA, channel

The Florida Keys are the birthplace of flats fishing. Photo: Ian Wilsonmarkers were the first thing that came to mind in an overhaul of the Sanctuary’s approach to management. “That’ll be huge,” he said. Nearly every day, he sees boats run aground, as do most guides fishing the Keys—not to mention the constant disturbance of fish throughout the year. In the maze of shallow basins and channels that make up the backcountry of the Keys, that’s acutely felt in how scarred flats degrade over time, losing seagrass and in turn becoming less attractive to fish. “People have discovered the water, and that’s a major challenge for NOAA to take on,” said Captain Will Benson, a LKGA member and a BTT representative as well as an advisory council member for the Sanctuary. “I see boats running aground and chewing up the bottom almost every day, and there is no law enforcement.”

“We’re asking for the Sanctuary to put in channel markers to help less-educated boaters, first-time boaters, or frankly people who have run out there a lot but find themselves challenged to navigate safely,” Benson said. Anyone who’s found themselves trying to line up islands in the dark or threading keyholes in low light knows that it’s not just novices who could benefit from more markers in the Keys but everyone. Not only would it condense boat traffic and provide safe passage for those running the backcountry, but as Benson said, it would protect the flats that form the heart of the fishery and, in some ways, codify behavior that the majority of guides already practice. “It comes down to good boater education,” he said.

From Ocean Reef down to Sugarloaf, everyone has watched as a string of tarpon shows up hundreds of yards away. The mind starts making dozens of calculations as the body courses with cortisol, and then in some cruel turn of happenstance, an uneducated boater or jet ski buzzes the string, and the fish change

course. Sometimes that happens over and over, eviscerating any chance at a shot. While it’s a stretch to assume that the decades of etiquette practiced by guides could be commonplace among everyone (Have you ever tried to explain this to a jet skier?), markers along the ocean side of the Keys would help control that––alongside a network of idle zones and no motor zones to protect those important basins and travel lanes.

“The tarpon fishery is definitely the one that seems to be taking the brunt of this,” Dr. Boucek said. And included in the coalition’s suggestions is a series of idle and no motor zones to suit those places where fish tend to congregate, whether to move from channel to channel or rest in a certain basin.

Herstedt remembered the pushback from guides when the Everglades National Park introduced its own no motor zones, referred to as poll/troll zones, which were originally overly expansive and limited access, but were modified with input from a BTT-fishing guides collaboration to incorporate boat running lanes. But after seeing the effect on the fishery, especially in places like Snake Bight, Herstedt feels that guides understand the value. “We weren’t happy,” he said at first, “but now we love them.” For the FKFGA and Herstedt, the priority with the Restoration Blueprint is to protect as much they can while they can—a thread of solidarity among everyone in the Keys.

“It matters to everybody,” Benson said. “The Florida Keys has a coastal economy.” So whether or not this was on their radar, the guides all felt that this was central to the character of the Keys. “We need to protect it,” Tipler added, “Make it better.”

With all of the moving parts and vast stretches of water that fall within the Sanctuary’s borders, not to mention the other federal and state management agencies that work within its

borders, BTT and LKGA pushed hard for measures that would focus on water quality, adequate law enforcement, and prioritizing adaptive management. Just in the last five years alone, the effects of climate change, hurricanes, and boat traffic seem exponentially worse. “The agency needs to be more responsive to those changes,” Benson said. “We’re asking them to include this concept of adaptive management, so we don’t have to wait 20 years to respond to something that needs to be addressed now.” It’s a means to cut through some of the red tape and bureaucracy that comes with coordinating responses among five agencies with different approaches to management. If a boundary needs to move due to a displaced bird population or blocked channel, the Sanctuary can act accordingly rather than sitting on its hands for years.

But as everyone involved will tell you, it’s not the sole responsibility of the Sanctuary to protect the resource—it’s yours and mine too. For everyone who visits the Keys, whether it’s to snorkel, get lost, or fish, there needs to be some engagement beyond your time on the water. Dr. Boucek pointed to how awareness in recent years has spread like wildfire, and he hoped that investment in advocacy on the part of anglers and guides continued. Write policy makers. Push the agencies to take responsibility. Get friends involved. “Stay engaged,” he said.

This back-and-forth among the handful of agencies, BTT, and guides is just one part in a long sequence. Each step will shape what this place looks like in a century.

Bonefish have long been associated with the Florida Keys, the birthplace of flats fishing, but, up until very recently, their spawning activity in Florida waters had remained largely a mystery.

Building on previous work in the Bahamas, where Bonefish & Tarpon Trust has identified numerous bonefish pre-spawning aggregations (PSAs), BTT scientists are now homing in on areas in the Keys important to spawning, and have confirmed what many have suspected for decades: that Keys bonefish do what bonefish do in the Bahamas and other places across the Caribbean. They gather in these PSAs, gulp air to fill their swim bladders and migrate offshore at night during certain moon phases from November through March or April. They then dive hundreds of feet

deep. As they return to the surface, the pressure changes in their swim bladders allow for the release of eggs and sperm, creating a broadcast spawning event.

And now, thanks to ever-evolving technology, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust knows even more about these clandestine romantic gatherings of bonefish schools that can number in the thousands. All it took was one fish to give up its secrets.

Thanks to a new monitoring tool called an archival data storage tag (ADST), Dr. Ross Boucek, BTT’s Florida Keys Initiative Manager, was able to better understand the bonefish mating ritual that, up until 2010, was a virtual mystery (that’s when PSAs were first discovered and documented). Boucek and his team—the first to ever use this technology—implanted four bonefish with

ADSTs, and were able to determine when the fish gathered, when they moved offshore and, within a 12- to 13-minute window, when the bonefish likely spawned.

Only one of the four tagged fish spawned, Boucek believes. Three of the tagged fish, according to data from their ADSTs, never moved offshore to deeper water. But that last fateful bonefish did its thing.

“It gathered at the PSA site and then it just kind of disappeared for 48 hours,” Boucek reported. “When it came back, the data we collected told us what likely happened.”

Here’s the rest of the love story.

When that one tagged fish moved offshore, likely with thousands of others gathered together in a PSA, it dove to a depth

Bonefish are on the rebound in the Keys after a dismal decade that followed a declining trend.

of 304 feet. As it ascended in the water column, it paused below 100 feet for more than 12 minutes. This is likely when it released its eggs (the fish was female). Then it returned to the surface and ventured back to the flats.

“We relocated this fish with a manual tracker nine days after it spawned, when the fish tracker detected it—it was almost in the same spot where I caught it and put the tag in,” Boucek said. How much time passed between when the fish was caught and tagged and when it turned up on its home flat after its romantic jaunt? Just about two months.

Bonefish are on the rebound in the Keys after a dismal decade that followed a declining trend. Now, Boucek said, there’s a growing population of bones around Key West and numbers continue to improve on the flats throughout the Keys. Why? Research into the question is ongoing, but it’s clear the population rebound coincided with a number of different events.

For instance, the state of Florida recently spent about $1 billion removing old and faulty septic systems in the Keys. When that effort concluded, fish numbers started to rise.

“It’s hard to ignore that,” Boucek said. “But there are a number of different mechanisms in play, including planetary-scale ocean phases and other events that could cause conditions to be more

favorable for bonefish.”

Additionally, all the bonefish in Florida aren’t necessarily from Florida—BTT’s research shows that some larvae from spawning events in Mexico, Belize, and even southwest Cuba can drift on ocean currents to the Keys, where they mature and take up residence. The efforts of BTT and others in Belize, Mexico, and Cuba to reduce harvest of bonefish by artisanal and commercial fisheries might be having a positive impact on bonefish populations in Florida.

“We still have so much to learn,” Boucek said, “but we’re making great progress. There are so few opportunities to discover something new, so this recent detection meant a lot.”

What’s next? Well, if Boucek had his way, he’d be on hand for the next gathering of bonefish in a PSA in the Keys, and he’d do whatever he had to do to document the entire spawning process. And that may not be a pie-in-the-sky goal with the assistance of even more new tech—this one, a prototype receiver.

The receiver technology was initially used on surf beaches to warn swimmers and surfers in real-time when sharks were in the area. Boucek and BTT hope to know exactly when the next PSA starts to gather in the Florida Keys by using that same tech. The novel receiver was deployed in December 2022.

If the receiver alerts scientists in real time of a PSA starting to form, Boucek and team could drop everything and go witness this aggregation.

“If it works, we might be able to actually see a PSA in the Keys,” he said. “How cool would that be?”

Even cooler? If Boucek and his team find the PSA, they could use tag tracking gear to follow the bonefish as they move offshore to spawn. Not only would they get to witness a PSA, but they could essentially follow thousands of bonefish offshore to an actual spawning site.

“This project is really pushing the envelope with new technology,” Boucek said. “The goal is to be at the same place at the same time when these fish spawn.”

Chris Hunt is an award-winning journalist and author whose latest work includes The Little Black Book of Fly Fishing (with Kirk Deeter) and Catching Yellowstone’s Wild Trout. His work has appeared in Outdoor Life, Field & Stream, TROUT, The New York Times, Hatch Magazine, The Fly Fish Journal and other publications. He lives and works in Idaho Falls, ID.

The nets are called purse seine nets, and there is nothing inherently nefarious about them. They are simply effective. Astonishingly effective.

The spotter planes go out first: Fixed-winged aircraft that course low across the water, sometimes as low as 500 feet. In the Gulf of Mexico, they probe the coasts of Louisiana and Mississippi, and to a lesser extent, the waters off Texas and Alabama. Along the shores of Virginia, they scour the Chesapeake Bay and the open ocean. No matter the water, the spotters look for dark splotches that signal a school of menhaden, the small, oil-rich fish some call “the most important fish in the sea.” On the radio, the spotters stay in contact with large fishing vessels below, called “steamers.” Many are of World War II vintage, retrofitted for the job. Riding on the steamers are two seine boats, some as long as 40 feet. Each carries half of a purse seine net that can be 1,700 feet long or better, and some 60 feet deep. Top-line corks float the upper edge, while the bottom edge is fitted with metal rings,

through which a cable passes to cinch the net shut.

When the fish are located, the spotter plane directs the action. The seine boats are lowered overboard, and they begin to circle the school, playing out the net. As the seine boats close the circle, the steamer pushes more fish into the net. Soon the bottom of the purse seine is winched tight, and a hydraulic “raise rig” lifts the net to the surface. There, tens of thousands of fish are sucked into the ship’s hold through a vacuum hose more than a foot wide. There is little culling, and little ability to sort the catch. With few exceptions—such as marine mammals and sea turtles—whatever is in the net is disgorged into the ship’s hold. Whatever is in the net dies.

Along the two coastlines, the menhaden fishery is an enormous industry—the second largest continental fishery by weight—even though limited to a relatively few players. Two foreign-owned companies dominate: In the Gulf of Mexico, the enormous Omega Protein company operates fishing fleets and fish processing

Menhaden continue to be mismanaged by legislative bodies, negatively affecting recreational fisheries in both Atlantic and Gulf states.A commercial fishing boat searches for menhaden in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: Healthy Gulf

plants in Abbeville, Louisiana, and Moss Point, Mississippi, while Daybrook operations are sited at Empire, Louisiana. In the Gulf alone, the two companies harvest about 1.2 billion pounds of menhaden each year. Along the Atlantic coast, Omega Protein runs a menhaden processing plant in Reedville, Virginia. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission approved in November a 20 percent increase in the coastwide catch to nearly 515 million pounds. In the Chesapeake Bay alone, the harvest cap is still nearly a staggering 112 million pounds.

Given such numbers, you might think that menhaden harvests would be deeply studied and carefully regulated. Instead, the menhaden fishery has the dubious distinction of being among the most unregulated in the country.

This despite growing concerns over bycatch.

This despite the critical role these diminutive fish play in feeding scores of fish species.

This despite better ways to manage menhaden. **

Pogy, fatback, bunker—depending on where you live, there are a number of nicknames for menhaden. The small filter feeders seine the open water for phytoplankton and zooplankton, and travel in enormous schools. Oily and soft-fleshed, menhaden are ground up, or “reduced,” to provide meal for pet foods and other products, and oil for nutrition supplements.

It’s a fish you likely wouldn’t eat if given the chance, but there are plenty of other willing takers. Menhaden are consumed by at least 32 prey groups. Redfish, speckled trout, and seabirds key in on the juvenile fish. King and Spanish mackerel, sharks, gag grouper, dolphins, tuna, and mahi mahi hunt the adults; one study showed that Gulf menhaden support some 40 percent of the diets

of both Spanish and king mackerel, and 20 percent of the food base for speckled trout. Along the mid-Atlantic and northeastern coasts, menhaden are a primary food source for striped bass, which have been shown to be particularly sensitive to menhaden harvest: not enough menhaden equals reduced striper growth and less successful spawning. And menhaden are a primary food source for tarpon in both the Gulf of Mexico and along the Atlantic coast. A Bonefish & Tarpon Trust-sponsored study of fin clips from angler-caught tarpon was launched to use stable isotope analysis to help determine the importance of menhaden and other prey items to tarpon from Louisiana to Virginia. Many fish spend three to five months per year in more northerly foraging areas such as North Carolina’s Pamlico Sound. “If we can show that this is a very important food source in those northern areas,” says Dr. Lucas Griffin, a BTT collaborating scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, “it really leverages the message not only of menhaden conservation but the conservation of habitat and water quality that supports the freshwater flows menhaden need.” Just like stripers, insufficient menhaden forage for tarpon likely impacts growth rates and spawning.

All of this explains why menhaden are called a “forage fish”: By their legions they feed a significant portion of sea life along both the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts. Unfortunately, current efforts to manage menhaden populations—and both commercial and recreational harvests of the fish for bait—are coming up short. Historically, menhaden have been managed under a single-species stock assessment scenario, in which harvest levels are projected to maximize the number of fish that can be caught in a given year while preventing overfishing. A typical stock assessment is a snapshot of a current species population, but it doesn’t take into account ecological considerations beyond

the target species’ numbers. Stock assessments don’t factor in the ecology of the ecosystems in which the fish live. They don’t incorporate metrics such as water quality or habitat needs. They don’t take into account how critical a fish population might be to other fish and wildlife species as prey items, and they don’t reflect the critical role menhaden play in nutrient cycling—feeding on plankton and transferring those nutrients far up the food chain.

Other concerns about the current management strategy for the menhaden fishery are worries that the close-to-shore fishery—in many instances, the purse seines are deployed within a few hundred yards of the beach—damages shallow-water bottom habitat and can foul the water with a nasty mix of discarded fish and oily effluent.

And then there is bycatch. Many statistics point to the relatively low percentages of bycatch in the menhaden fishery. Estimates range between 1 and 2.5 percent, but when the commercial take is in excess of a billion pounds, the small percentages add up. An average annual haul in the Gulf of Mexico might be in the neighborhood of a billion pounds of menhaden. But 2.35 percent of that is 23 million pounds of bycatch. That’s no small number. NOAA reported in a 2016 study of bycatch in the Gulf menhaden fishery that as many as 1.1 million pounds of redfish fall prey to the purse seines each year. That figure certainly includes untold thousands of healthy breeding fish.

While it is true that recent stock assessments of menhaden—in the Gulf in 2021 and the Atlantic in 2022—concluded that the fisheries were not overfished or experiencing overfishing, it is also

true that using traditional stock assessments alone is an outdated and incomplete way of stewarding fish populations. “Stock assessments are a reactive approach,” explains Dr. Aaron Adams, BTT Director of Science and Conservation. “By the time you notice in a stock assessment that the fishery is declining, it may be too late to correct. If fish populations are declining due to overfishing, theoretically you can correct that. But if the critical habitat is lost, you’re done. For menhaden, issues such as habitat loss and water quality problems are mostly outside the processes that drive management.” And the growth of a market for menhaden as bait—both for recreational anglers and commercial crabbers and lobster potters—is something to keep an eye on. In the Atlantic, nearly a third of menhaden harvest is for bait and recreational landings.

Which is why BTT and a host of partners—among them the American Sportfishing Association, Coastal Conservation Association, Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, National Audubon Society, Founding Fish Network, and fishing groups along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts—are working to change the narrative around menhaden harvests, and push regulators to recognize and codify a new way of thinking about these fish populations. Instead of simply managing by the numbers, disconnected from other ecological factors, a new paradigm would take into consideration the various other factors that affect fish populations.

Imagine, explains Adams, that you were in charge of throwing a luncheon buffet for 50 people. You ordered the food, put the kitchen staff in place, and opened the doors. Unfortunately, the first 10 guests in line were hungry and ate like hogs, loading their plates down as they moved through the buffet line. The next 20 guests might still have ample grub, but at the end of the line, the last 20 folks might find the roast beef picked over, the chicken down to a few scraggly wings, the deviled eggs gone, and the dessert table holding nothing but crumbs.

If you simply walked into the dining room at that moment, Adams explains, all you would know is that a lot of your guests got the short end of the stick. You wouldn’t know if there was a food shortage, or if kitchen staff didn’t show up for work, or if other factors were at play in the dearth of food.

“And that’s where we are with menhaden,” explains Adams. “There’s a black box that holds all these other factors that aren’t accounted for in a stock assessment, but that impact the population size. And we don’t look inside the black box.” We may know how many menhaden there are, he says, but not how many there could be, or should be, and what the limiting factors are that create such a gap. Much less is known about the impact harvest has on the ecosystem and the many species that rely on menhaden as food.

And it’s not only menhaden that are managed under this blinders-on approach, but just about every marine fish. Snook, redfish, permit, flounder, speckled trout—single species stock assessments are the standard methodology for modern marine fisheries management.

This needs to change, and thankfully, there are some steps in the right direction. In 2020, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission voted unanimously to include ecological reference points in its decisions affecting Atlantic menhaden. For the first time, consideration of menhaden’s impacts up the food chain would be required. A study had earlier found that without menhaden reduction fishing, there would be nearly 30 percent more striped bass in the system. For 2023, the ASMFC increased the catch quota for Atlantic menhaden by 20 percent, citing the 2022 stock assessment that found that the fish is in a healthy stock condition. But the commission was considering much higher

increases, so conservationists breathed a sigh of relief.

“We’d still like to see fewer menhaden extracted overall,” says Kellie Ralston, BTT Vice President for Conservation and Public Policy, “but we ended up in a pretty good place as far as the current harvest levels. It’s still a challenge with Atlantic menhaden, because the harvest is not well distributed along the coast, and there are locations in Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay with localized, concentrated menhaden harvest. This concentrated harvest can result in localized fishery depletions and impacts.” In June of 2022, BTT joined with a coalition of other groups and individual anglers that sent a petition to Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin asking him to move menhaden fishing out of Chesapeake Bay, which has resulted in a process to establish harvest buffer areas.

Fisheries conservationists hail these new approaches. “This is a relatively new approach to fisheries management,” explains Chris Macaluso, Director of TRCP’s Center for Marine Fisheries, “and there are lots of questions about how to find the right balance, and what this kind of management is going to look like in both the commercial and recreational fisheries. There are a lot of unanswered question that we are making our way through right now, but the broad scientific concept is fairly simple: Leave enough menhaden in the water to feed other fish.”

At present, Louisiana is at the center of these efforts because Louisiana holds a number of dubious distinctions. It is the only Gulf state that allows nearly unregulated fishing of menhaden. Florida’s blanket net ban keeps menhaden vessels out of its waters. Alabama has banned the practice. Other Gulf states have enacted buffer zones inside of which menhaden netting is disallowed: Texas has a half-mile limit, while Mississippi has buffer zones that extend one mile from the beach.

Louisiana has not followed suit, however. The state’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries nixed a proposed one-mile buffer zone in 2020. And in 2022, Louisiana House Bill 1033 passed the House of Representatives but was stymied in the Senate. The bill would have capped Louisiana’s menhaden haul at 573 million pounds a year.

Part of the challenge in Louisiana and other Gulf States is rooted in the structure of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission (GSMFC). Unlike the ASMFC, whose decisions are legally binding among the states and come with enforcement protocols, the GCMFC doesn’t have the authority to set regional catch limits and enforce them. The GCMFC “lacks the teeth of the Atlantic states’ agreements,” says Ralston. That requires a state-by-state approach, which is both time-consuming and more likely to involve

political pressures from industry and legislators.

For example, Louisiana did accept a quarter-mile buffer in late 2021, but that exclusion zone was originally proposed as a halfmile buffer. A quarter-mile provides very little protection, says Macaluso. “That line isn’t based off the water’s edge, but on the inside-outside shrimp line established in the legislature. It was a token measure by the Louisiana Department of Fish and Wildlife. In places those boats are still right on top of the beach. The peak of the menhaden fishery is during the redfish spawn, from mid-August to November. And that’s when you see the majority of dead redfish floating to the beach, and dramatic decreases in water quality.”

That quarter-mile effort was against the wishes of the conservation community, says David Cresson, Chief Executive Officer of the Coastal Conservation Association Louisiana. “It was just a way for the state to shut everybody up and look like they were doing something meaningful.” And since the original passing, large chunks of the coast have been removed from the regulation, including most of the Louisiana coast from the Mississippi River east to the Mississippi state line. “That was by design,” Cresson figures. “Mississippi has a one-mile buffer statewide, so now the Omega Protein boats stationed in Mississippi come to Louisiana waters to fish.” **

Moving forward on menhaden conservation along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts requires both acknowledgement of improvements in the fishery—most particularly in the Atlantic states—and a steadfast commitment to education about the stakes of not conserving fish populations whose ecological importance is only now being incorporated into management, though the science has been clear for a long time. At the moment, the political deck in Louisiana is stacked against meaningful conservation.

But Louisiana governor John Bel Evans can’t seek re-election, so there will be new legislators and a new governor in 2024. “The path forward is to continue fighting the good fight,” figures Cesson. “There is a strong groundswell of support in Louisiana for reasonable regulations in the menhaden fishery. It’s only politics that has stopped us from making progress, and we intend on making this a campaign issue that candidates will have to take a stand on.”

If nothing else, the challenges in Louisiana have helped build a strong coalition to fight for marine resources, says Ralston. The National Audubon Society is looking at the effects of menhaden harvest on birds, and TRCP’s ecosystem perspective is gaining traction. CCA’s emphasis on bycatch and sea bottom habitat issues is finding resonance among many anglers. And BTT’s expertise in science and research is bolstering arguments for greater conservation measures. From the American Sportfishing Association to the National Wildlife Federation and the National Marine Manufacturers Association, “there is a very diverse set of stakeholders in this fight,” Ralston explains, “and when you look at that many different groups, from so many different perspectives, all saying the same thing, and there is one lobby saying the opposite, that makes a strong case for the need for change.”

These are not mom-and-pop shrimping operations, explains Macaluso. These are not sole proprietor watermen out there running crab traps. “These are massive foreign corporations,” he says, “that employ plenty of hard-working local people. Our mission is not to put them out of business, but for there to be more complete understanding of the impact the industry is having.”

Belize has less than 200 miles of coastline. Yet its modestly sized coastal habitat boasts an outsized abundance of marine life, from a large section of the Meso-American reef (and its many denizens) to immense populations of permit, bonefish and tarpon. The Belizean citizenry and government officials largely recognize the ecological, cultural and economic significance of its marine environs, and have taken an active role in seeking ways to ensure its long-term well-being. This was evidenced in 2009, when Belize established catch-and-release regulations for bonefish, tarpon, and permit. The small west Caribbean nation has also established eight marine reserves, offering enhanced protection for sport fish and other wildlife.

Since 2006, BTT has been working in Belize to provide scientific and policy expertise where required to further conservation efforts. BTT’s first research project focused on juvenile bonefish habitat; a study soon after focused on tagging adult bonefish, tarpon, and permit to identify their home ranges and movement patterns. In 2013, BTT commissioned an economic impact assessment that showed that the catch-and-release flats fishery generates $112 million Belizean Dollars annually, underscoring the need to

conserve it and ensure its sustainability.

In recent years, BTT has stepped up its efforts in Belize. In 2019, Dr. Addiel Perez was hired as Belize-Mexico Program Manager; in 2022, he was joined by Lysandra Chan, who serves as Technical Assistant for the program. Having staff on the ground in Belize has enabled BTT to strengthen key partnerships with Belize’s angling community and resource managers with the goal of developing science-based conservation policies to integrate habitat protection and restoration in fishery management plans.

“There are three components to our work in Belize,” said Kellie Ralston, BTT Vice President for Conservation and Public Policy. “To educate, to engage in active conservation, and to provide information to support sustainable management policies and practices. As Belize gives non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in some regions the ability to co-manage conservation efforts with government agencies, we’ve learned to work closely with such groups.” Like in all the places where it works, BTT is pursuing an inclusive approach, working with all Belizean flats fishing stakeholders in a supportive role to further conservation goals.

BTT is working with resource managers in Belize to conserve essential habitat for bonefish, tarpon, and permit.

Photo: Jess McGlothlin

BTT is working with resource managers in Belize to conserve essential habitat for bonefish, tarpon, and permit.

Photo: Jess McGlothlin

Highlighted below are some of BTT’s current and ongoing initiatives in Belize.

A development group called MML Investment LTD is attempting to build a resort in close proximity to Big Flat, Turneffe Atoll’s largest backreef flat and an important feeding area for bonefish and permit. The development would consist of 22 cabanas—12 of them over the water—plus walkways connecting the three islets resting west of the flat. The project—within 500 feet of the Meso-American Reef—would require considerable dredging and clearance of approximately 20 percent of terrestrial flora to place buildings.

The development flies in the face of many rules and regulations already in place to protect coastal environments. If ultimately approved, it would add fuel to the already problematic fire of development in protected areas, following Blackadore Caye and Cayo Rosario. BTT is working with a number of partners, including Turneffe Atoll Trust and Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association (TASA), which co-manages the Turneffe Atoll Marine Reserve, to mobilize opposition to the development. While not anti-development, TASA believes developers must operate within the regulations. Short-term revenue generation cannot be pursued at the cost of long-term damage to the ecosystem.

Close to the town of San Pedro on Ambergris Caye, local flats fishing guides are battling a development on Cayo Rosario, which is known for exceptional permit fishing. Like the proposed construction at Big Flat, Cayo Rosario’s plan calls for overwater structures and considerable dredging—even though the property falls within the boundaries of the Hol Chan Marine Reserve. Should the project continue, the prolific flats, home to abundant marine and bird life, will be forever changed. “Our guides used to utilize the flats surrounding Cayo Rosario every day,” said Chris Leeman, co-owner of Blue Bonefish Lodge on Ambergris. “But

since development has started the fish are less frequently visiting those flats.”

Working with Leeman and other local stakeholders, BTT has rallied members of the Ambergris guide community and others in the tourism industry to oppose the resort construction on Cayo Rosario. BTT has also released statements to government officials citing the negative impacts of the development, and assisted Hol Chan Marine Reserve managers with their statement of opposition.

In 2010, BTT helped fund groundbreaking research on bonefish spawning habits. During full and new moon cycles from fall through early spring, fish form pre-spawning aggregations (PSAs) at nearshore sites, where they prepare to spawn by porpoising at the surface and gulping air to fill their swim bladders. At night, these large groups of fish—as many as 10,000—swim offshore and dive hundreds of feet before surging back up to the surface. It’s believed that the sudden change in pressure during the ascent

makes their swim bladders expand, helping them release their eggs and sperm. After fertilization, the hatched larvae drift in the ocean’s currents for between 41 and 71 days before settling in shallow sand- or mud-bottom bays, where they develop into juvenile bonefish.

Dr. Perez is conducting ongoing research in northern Belize to identify PSAs, using acoustic tags to track the direction the fish are heading to spawn. “If we can translate this data into management strategies, we’ll be able to protect pre-spawning aggregation areas for much of the bonefish population in northern Belize and the southern Yucatán,” Dr. Perez said. “That will make for a healthy fishery.”

Understanding permit movement patterns allows managers to identify the habitats that are most important for protection, while measuring the effectiveness of protected areas. Since 2021, BTT has worked with anglers and guides in northern Belize to tag 138 permit to monitor movement patterns. Preliminary data shows that permit have complex movement and habitat use patterns that will require a regional conservation strategy. “We know from tagging around Cayo Rosario that permit regularly range six to seven miles,” Dr. Perez added. “If any of the surrounding habitat is negatively impacted, fragmentation will occur, impacting the overall health of the fishery.”

“Heart and Tail” beach traps are common along the Belizean coast. Often, bonefish, permit and tarpon will find their way into the traps. If the traps were checked regularly, this might not be problematic, as the sportfish are returned to open water while commercial species are harvested. But frequently, traps are not checked for four or five days, depending on market demand for fresh fish. Over such a long period of confinement, barracuda in traps might injure or kill bonefish and permit. At the least, confinement is believed to stress the fish. BTT is working with co-managers in Sarteneja, Bacalar Chico and Hol Chan to encourage more sustainable practices, limiting the time traps are left unattended.

There is good reason to think that positive developments for Belizean marine conservation efforts are on the horizon. Two heavyweight conservation groups—The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF)—have committed resources toward the effort. “With the “Blue Bonds for Ocean Conservation,” TNC has agreed to finance a significant portion of Belize’s government debt in exchange for an expansion of marine protections,” said Kellie Ralston, BTT’s Vice President for Conservation and Public Policy. “Belize currently has eight marine reserves. The goal is to expand the area of protected ocean waters to 30 percent.” The Blue Bonds initiative will generate an estimated $180 million USD for marine conservation efforts.