CHANGING

TARPON DYNAMICS

TARPON DYNAMICS

Crush barbs and pick up stream-side trash. Volunteer skills, money and time. Fight for access and vote your conscience. Even our smallest efforts build a future for wild fish, clean water and an inclusive community. It’s not too late. It’s never too early. It’s every day. We are all wild fish activists.

National Park, including bucket-listers such as tarpon, redfi sh and snook.

Nearly 300 species of fi sh depend upon the massive-but-fragile ecosystems unique to Everglades

© 2021 Patagonia, Inc.

© 2021 Patagonia, Inc.

Dr. Aaron Adams, Monte Burke, Sarah Cart, Bill Horn, Jim McDuffie, Carl Navarre, T. Edward Nickens

Publishers: Carl Navarre, Jim McDuffie

Editor: Nick Roberts

Editorial Assistant: Miranda Wolfe

Layout and Design: Scott Morrison, Morrison Creative Company

Contributors

Monte Burke

Grace Casselberry

Dr. Steven Cooke

Dr. Andy Danylchuk

Dr. Luke Griffin

Alexandra Marvar

T. Edward Nickens

Ashleigh Sean Rolle

Chris Santella

Photography

Cover: Paul Dabill

Dr. Aaron Adams

Alphonse Fishing Company

Jenni Bennett

Tyler Bowman

Brian Chakanyuka

Greg Clark

Adam Cohen

Dr. Andy Danylchuk

Dan Diez

Pat Ford

Dr. Luke Griffin

Pierre Joubert

Justin Lewis

Tommy Locke

Miami Waterkeeper

Katherine Mikesell Mill House

T. Edward Nickens

Dr. Addiel Perez

Nick Roberts

Nick Shirghio

Silver Kings

Sport Fishing Television

Patrick Williams

Ian Wilson

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal

2937 SW 27th Avenue Suite 203

Miami, FL 33133

(786) 618-9479

Carl Navarre, Chairman of the Board, Islamorada, Florida

Bill Horn, Vice Chairman of the Board, Marathon, Florida

Jim McDuffie, President & CEO, Miami, Florida

Harold Brewer, Immediate Past Chairman, Key Largo, Florida

Tom Davidson, Founding Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Russ Fisher, Founding Vice Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Bill Stroh, Treasurer, Miami, Florida

Jeff Harkavy, Founding Member and Secretary, Coral Springs, Florida

John Abplanalp

Stamford, Connecticut

Dr. Aaron Adams

Melbourne, Florida

Rich Andrews

Denver, Colorado

Stu Apte

Tavernier, Florida

Rodney Barreto

Coral Gables, Florida

Dan Berger

Alexandria, Virginia

Bob Branham

Plantation, Florida

Mona Brewer

Key Largo, Florida

Adolphus A. Busch IV

Ofallon, Missouri

Evan Carruthers

Maple Plain, Minnesota

Advisory Council

Randolph Bias, Austin, Texas

Charles Causey, Islamorada, Florida

Don Causey, Miami, Florida

Scott Deal, Ft. Pierce, Florida

Paul Dixon, East Hampton, New York

Chris Dorsey, Littleton, Colorado

Chico Fernandez, Miami, Florida

Mike Fitzgerald, Wexford, Pennsylvania

Pat Ford, Miami, Florida

Christopher Jordan, McLean, Virginia

Bill Klyn, Jackson, Wyoming

Andrew McLain, Clancy, Montana

Jack Payne, Gainesville, Florida

10th Annual NYC Dinner & Awards

To conserve and restore bonefish, tarpon and permit fisheries and habitats through research, stewardship, education and advocacy.

October 19, 2021

The University Club New York, NY

Sarah Cart

Key Largo, Florida

John Davidson

Atlanta, Georgia

Greg Fay

Bozeman, Montana

Allen Gant Jr.

Glen Raven, North Carolina

John Johns

Birmingham, Alabama

Doug Kilpatrick

Summerland, Florida

Jerry Klauer

New York, New York

Wayne Meland

Naples, Florida

Ambrose Monell

New York, New York

Sandy Moret

Islamorada, Florida

Steve Reynolds, Memphis, Tennessee

Ken Wright, Winter Park, Florida

Marty Arostegui, Coral Gables, Florida

Bret Boston, Alpharetta, Georgia

Betsy Bullard, Tavernier, Florida

Yvon Chouinard, Ventura, California

Matt Connolly, Hingham, Massachusetts

Marshall Field, Hobe Sound, Florida

Guy Harvey, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Steve Huff, Chokoloskee, Florida

James Jameson, Del Mar, California

Michael Keaton, Los Angeles, CA / MT

BTT at The Burge

October 27, 2021

Burge Plantation

Newton County, GA

John Newman

Covington, Louisiana

David Nichols

York Harbor, Maine

Al Perkinson

Charleston, South Carolina

Chris Peterson

Titusville, Florida

Jay Robertson

Islamorada, Florida

Rick Ruoff

Willow Creek, Montana

Bert Scherb

Chicago, Illinois

Casey Sheahan

Bozeman, Montana

Adelaide Skoglund

Key Largo, Florida

Paul Vahldiek

Houston, Texas

Rob Kramer, Dania Beach, Florida

Huey Lewis, Stevensville, Montana

Davis Love III, Hilton Head, South Carolina

George Matthews, West Palm Beach, Florida

Tom McGuane, Livingston, Montana

Andy Mill, Aspen, Colorado

John Moritz, Boulder, Colorado

Johnny Morris, Springfield, Missouri

Jack Nicklaus, Columbus, Ohio

Flip Pallot, Titusville, Florida

Mark Sosin, Boca Raton, Florida

Paul Tudor Jones, Greenwich, Connecticut

Bill Tyne, London, United Kingdom

Joan Wulff, Lew Beach, New York

BTT 7th International Science Symposium

November 12 – 13, 2021

Bonaventure Resort & Spa

Weston, FL

10 The Perfect Storm

Florida’s crumbling water infrastructure and outdated treatment systems threaten the flats fishery. Alexandra Marvar

New research is shedding light on the movement patterns of tarpon in the Florida Keys, information that will be applied to conservation. Monte Burke

The search for bonefish pre-spawning aggregations in the Florida Keys intensifies. T. Edward Nickens

Inspired by angling and the natural world, acclaimed artist Tim Borski and his family have made their mark in the Florida Keys. Monte Burke

BTT is partnering with resource co-managers in Belize and Mexico to conserve the region’s iconic flats fishery. Chris Santella

New research underscores the threat from sharks that tarpon face, and the importance of being an ethical angler. Grace Casselberry and Dr. Andy Danylchuk

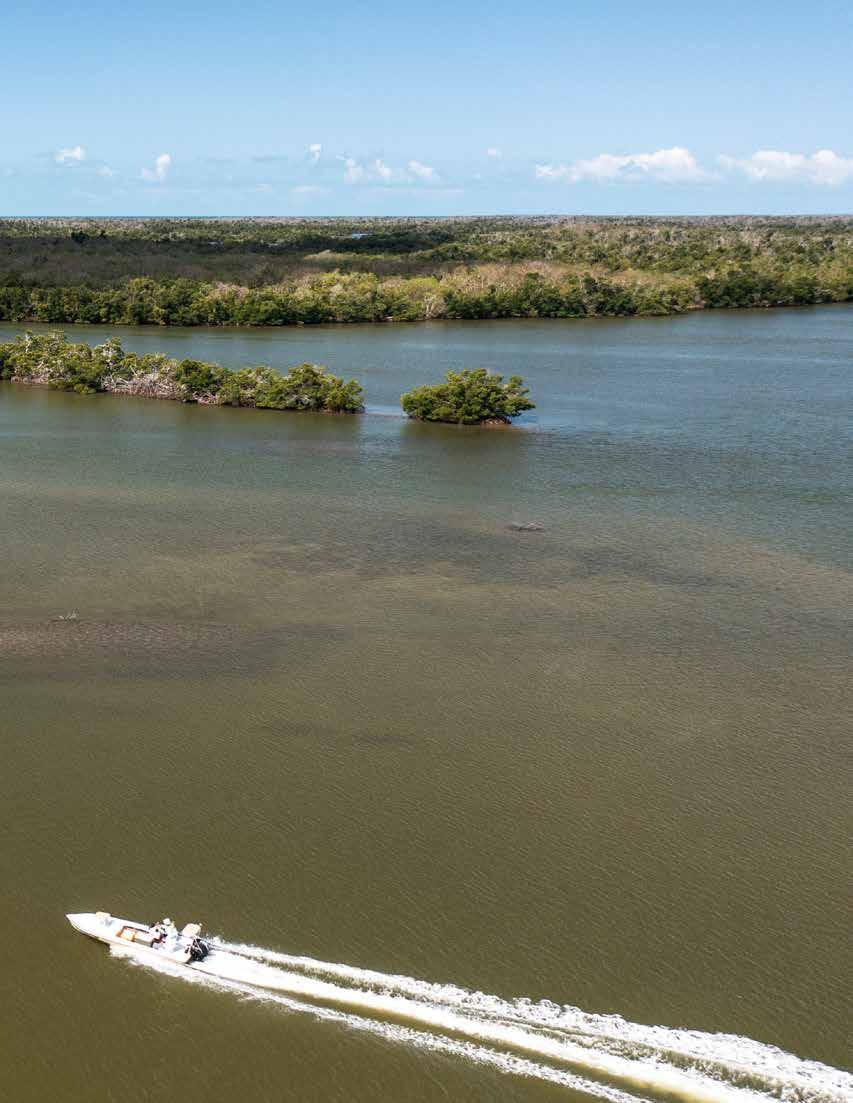

Anglers explore the Everglades. Photo: Nick Shirghio

Every important research project on the flats involves a little oldfashioned sleuthing. We see it when scientists interview stakeholders for new leads, ground-truth habitat conditions observed from satellite imagery, and use tracking devices to monitor fish movements.

A great example of our detectives at work can be found in BTT’s search for bonefish spawning areas in the Florida Keys. Where do Keys bonefish spawn? The answer is a missing link in our understanding of bonefish reproduction in the region, and discovering these locations is a necessary first step in their conservation. By studying the bonefish that use them, we can also begin to answer other important questions. Are local spawners experiencing environmental stresses that are potentially impacting the population? What portion of the Keys fishery originates from local spawns versus the possible recruitment from more distant locations?

In his excellent article that follows, T. Edward Nickens chronicles new efforts that are yielding promising clues. Among them, legendary Keys guides were recently interviewed to glean their historic observations and extensive knowledge of the fishery. These conversations netted several potential sites, three of which will be the focus of intensive research by BTT scientists next season.

In a similar way, BTT’s scientists have begun crunching data from the multi-year Tarpon Acoustic Tagging Project. As Monte Burke explains in his article, “Creatures of Habit,” the movements and habitat uses of Atlantic tarpon are being examined anew with the richest dataset ever compiled on the species. New findings demonstrate the highly repeatable behavior of individual tarpon and refine our understanding of what triggers their migration. Just as angler Tom Evans could recognize familiar tarpon like “Spooner” every season in Homosassa, it’s likely that we’re also fishing the same body of fish on our angling pilgrimages to the same locations and at the same times each year.

Monte also shares the concerns of Keys guides that tarpon movements are changing—and that some tarpon that once arrived like clockwork are now missing, especially in the Lower Keys. What triggers these changes remains a mystery—and a subject for future analysis and research. Reasoned speculation includes degraded habitat, altered flows, increased fishing pressure and boat traffic, among other human-induced impacts. As Monte concludes, it’s clear that “humans and tarpon are in this together. And we need to focus increasingly on ways in which we can hold up our end of the bargain.”

There is no better place to uphold our end of the bargain than by working together to address Florida’s continuing water woes. If we lose the water, we’ll also lose aquatic habitats and all the species that rely on them.

In this issue, Alexandra Marvar’s account of “Florida’s Water Infrastructure in Dire Straits” should be our call to action. Florida has become a sieve leaking nutrient pollution and dangerous contaminants into waterways and coasts statewide. These are

Carl Navarre, Chairman

Jim McDuffie, President

Jim McDuffie, President

problems that pose profound risks to human health, fish and wildlife, and a state economy that runs on water. Florida’s saltwater recreational fisheries provide an annual economic impact exceeding $9 billion and directly support nearly 90,000 jobs. Commercial fisheries add another $3.2 billion in sales and support more than 77,000 jobs. And it all hinges on clean water and healthy, abundant habitats.

According to statistics from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, some 1.6 billion gallons of wastewater have spilled since 2015, feeding toxic bacteria and poisoning habitats and marine life. And this is before taking into account the impacts of failing septic systems statewide. Yes, red tides like the one that gripped Tampa this past summer occur naturally and were first documented centuries ago by Spanish explorers. But there is growing consensus among scientists that nutrient pollution exacerbates the problem, making red tides and other harmful algal blooms more widespread and severe. Addressing these problems will require a significant and sustained commitment by the state to modernize water infrastructure and effectively manage water resources—and it will require our resolve to demand action.

There are hopeful signs on the horizon. Earlier this year, the Florida Legislature, with the encouragement of Governor Ron DeSantis, established a new Wastewater Grant Program with an initial appropriation of $500 million and $116 million in recurring funds, which BTT supported throughout the legislative process. This is a small but important first step in the marathon ahead.

We may have never imagined that water infrastructure would factor into mission success, but it has become a critical part of the calculus to fix our water and conserve Florida’s flats fisheries. As a result, BTT will be on the front lines of what promises to be a years-long slog to support policies and secure funding to enact meaningful change. And, as with other endeavors, we will be led by science. The results of a major, multi-year research study, which will provide sobering new evidence of the scale and likely sources of contaminants in South Florida bonefish, will be presented at the 7th International Science Symposium in November.

Thank you for your continued support of science and conservation programs, which is helping us to identify important spawning habitats of the Gray Ghost, better understand the movements of the Silver King, improve fishery management, and advocate for clean water and healthy habitats.

Business leaders Evan Carruthers and Ambrose Monell have joined the Board of Directors of Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, along with renowned Florida Keys fishing guide Captain Rick Ruoff.

“We are honored to welcome Evan, Ambrose, and Rick to the Board of Directors,” said Jim McDuffie, BTT President and CEO. “We will benefit greatly from their leadership and expertise as we pursue our mission to conserve the flats fishery.”

Carruthers is Chief Investment Officer & Managing Partner at Castlelake, LP, which he co-founded. He serves on the boards of several non-profit organizations and is a member of the national development committee for Pheasants Forever. An avid fly angler, Carruthers regularly participates in Florida Keys fishing tournaments.

“I am thrilled to join the board of Bonefish & Tarpon Trust,” said Carruthers. “I have been a supporter of the organization for a number of years and continue to be impressed by the leadership role they play in preserving the fishery that fly anglers such as myself enjoy each year. The organization’s steadfast commitment to scientific research has proven to be the bedrock in the pursuit of solutions for a more sustainable fishery for future generations to enjoy.”

Monell is President of the Ambrose Monell Foundation and the G. Unger Vetlesen Foundation and serves on the boards of the Peregrine Fund, Wildlife Conservation Society, and the Monell

Chemical Senses Center. He is a former trustee of Atlantic Salmon Federation and the Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, MA), and former Overseer of the Hoover Institute at Stanford University.

“I am delighted to have been asked to join the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Board of Directors,” said Monell. “BTT’s unique efforts in the research of these extraordinary species and their environments should be inspirational to other fishery researchers around the world. I very much look forward to furthering these endeavors and enjoying their continued success in the future.”

Ruoff began guiding in the Florida Keys in 1970 after graduating from the University of Miami with a degree in marine biology. He was elected Commodore of the Islamorada Fishing Guides Association, forerunner of the Florida Keys Fishing Guides Association, in 1976. Ruoff is credited with strengthening the organization and deepening its involvement in conservation issues, including Everglades restoration.

“I have been a bonefish and tarpon guide in Islamorada for the past 51 years,” said Ruoff. “In that time I have witnessed vast changes in Florida Bay and the fisheries. As my background is in marine biology, I realize that these changes are profound and that the solutions may take years or decades. First, we have to identify the problems. BTT has stepped up with a renewed energy and direction to research and resolution. I am proud to lend my experience and support to this organization.”

Partners In Preserving The Fish And The Places They Roam.

The new Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Florida license plate is now available.

Show your support for Bonefish & Tarpon Trust on the road with the new BTT Florida license plate, featuring the art of Derek DeYoung. Orders for the plate are now being accepted, and it will be produced as soon as BTT has sold 3,000 vouchers at a cost of $33 each ($25 will directly benefit BTT). If you hold a valid Florida Driver’s License or Official Florida Identification Card, you are eligible to purchase plate vouchers for your car, truck, trailer and RV! Visit btt.org/license-plate to reserve your BTT plate today.

Don’t miss Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s 7th International Science Symposium and Flats Expo on November 12 - 13, 2021, at the Bonaventure Resort & Spa in Weston, Florida. Presented by Costa, this special two-day event will bring together stakeholders from across the world of flats fishing—anglers, guides, industry leaders, government agencies, scientists, writers and artists. The program includes presentations on major research findings along with spin and fly casting clinics, fly tying clinics, panel discussions with top anglers and guides, art and photography, and a banquet honoring Florida anglers Sandy Moret and Chico Fernandez and BTT Research Fellow Dr. Andy Danylchuk for their contributions to flats fishery conservation. The Symposium will also feature an expanded Flats Fishing Expo, where sponsors will have a bright spotlight to share information about their products and corporate commitment to conservation. Space is limited, so visit BTT.org/Symposium to register today.

The economic value of the flats fishery provides important leverage for conservation. The information empowers anglers to advocate for improved management, and provides justification for resource managers and policymakers to enact new regulations. For this reason, BTT has commissioned economic impact assessments (EIAs) for flats fisheries across the Caribbean Basin. These studies have helped to enact conservation in many locations where BTT works: national parks to protect bonefish habitats in the Bahamas; catch-andrelease regulations for bonefish, tarpon, permit in Belize; a Special Permit Zone and spawning site closure for permit in Florida. To collect important economic information missing from the Caribbean coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, BTT and collaborators recently conducted an EIA in the region, determining that the flats fishery generates $45.2 million (USD) annually and supports 1,674 jobs. With this information comes more leverage for BTT and partners to improve the management of the flats fishery with the goal of ensuring its long-term health and sustainability.

BTT and the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation are pleased to announce a formal partnership to collaborate on state and federal policies that enhance coastal habitats and marine fisheries. Leaders of the two organizations signed an MOU at the spring BTT Board of Directors meeting in Islamorada, Florida.

One of the biggest challenges in conservation is determining which habitats are most important and should be prioritized for protection and restoration. Habitat use and movements by permit in northern Belize are knowledge gaps that BTT is working with guides and anglers to fill by launching a multi-year tagging program in collaboration with guides, fishing lodges, and the co-managers of protected areas in the region.

The William S. Broadbent Family of Vero Beach, Florida, has made a generous $100,000 donation to Bonefish & Tarpon Trust to establish the organization’s first endowment. Bill and Camille Broadbent have chosen to focus their resources on establishing an endowment at BTT because they view the permanency of an endowment structure to be the most efficient in creating funding sustainability and longevity at the organization.

This gift and strategy are in keeping with the Broadbents’ other philanthropic efforts; the family has established the initial endowments for the Montana Land Reliance, American Rivers, the Greenwich Land Trust, and the Williamstown Rural Lands Foundation—all of which have gone on to become significant forces in their conservation communities. Bill and Camille are hopeful that BTT will continue its efforts in being a leading edge science-based organization.

BTT celebrates the life of Joel Shepherd, who passed at the age of 83 on July 28, 2021, surrounded by his loving family. Twenty-five years ago, Joel was part of a small group of visionaries who founded Bonefish & Tarpon Unlimited. The Keys fishery we enjoy today is an important part of his legacy.

“Joel was one of six original founders of BTT, a tireless conservationist, a passionate angler, and one of the most interesting people you could share a skiff with,” said BTT Chairman Emeritus Tom Davidson. “The world and the environment lost a very special one with Joel’s passing. I will miss him desperately.”

Joel graduated from the University of Texas with a bachelor’s degree in Political Science in 1960. He went on to serve in Company C of the 156th Signal Battalion of the Michigan National Guard before beginning successful career as a business entrepreneur. Joel had a lifelong passion for the outdoors and especially enjoyed stalking bonefish, tarpon and permit on the flats of the Florida Keys.

He was a member of the Ocean Reef Rod & Gun Club and served as the President of the Card Sound Golf Club in Key Largo, FL, the Chairman of the Mariners Hospital Foundation Board of Directors in Key Largo, FL, and the Director of the Affiliated Boards of Baptist Health South Florida.

BTT was honored to team up with Gold Sponsor Bass Pro Shops and Operation WetVet to host a group of veterans for a special day of fishing in Tampa through Bass Pro Shops’ Fishing Dreams program. Despite less than ideal conditions, the veterans had a great experience—and even managed to land a permit! We

thank Anna Maria Charters and all the local captains who participated, as well BTT Gold Sponsor SweetWater Brewing Company and MISSION BBQ for catering the event. Most of all, we thank our veterans for their service and sacrifice.

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

BY ALEXANDRA MARVAR

Every four years, the American Society of Civil Engineers assesses the condition of bridges, dams, parks, ports, roads and other fundamental physical systems nationwide, and issues to America’s Infrastructure a letter grade. On this year’s report card, the United States earned a C- — not a score that inspires confidence. States receive individual evaluations too, and while Florida

was still awaiting its grade as of early July, it is expected to earn even lower marks. The Sunshine State ranks among the country’s lowest performers for drinking water—the ASCE estimates repairs and necessary maintenance would rack up nearly $22 billion. Nearly a quarter of its more than 1,100 dams have been deemed high-hazard status by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Outdated and inadequate water systems in communities

throughout the state regularly make their way into national headlines following prohibitive flooding, catastrophic sewage spills, pollution-spurred algae blooms, and the resulting largescale fish kills and manatee deaths.

“As in many other states across the country, Florida’s wastewater infrastructure is old, crumbling, and leaky” said Jim McDuffie, president and CEO of Bonefish & Tarpon Trust. “But the issues here are compounded by the fact that Florida is surrounded by ocean.”

Per data from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), crumbling or overloaded sewage systems have resulted in thousands of reported spills over the past five years, unleashing more than 1.65 billion gallons of sewage since 2015. That’s more than 2,500 Olympic-sized swimming pools of wastewater, and all the excess nutrients and heavy metals, fertilizers and herbicides, and pharmaceutical medications that come with them. These contaminants pour into waterways, and from most places in the state, they don’t have far to travel to the sea, where they feed toxic bacteria, kill seagrass and marine life, and further weaken an already struggling coral reef ecosystem.

“We’ve seen failures resulting in spills after major storms, for sure, but also under more routine, daily operations,” McDuffie said.

“Take, for example, the recent leaks in Fort Lauderdale.” There, overworked, decades-old sewer infrastructure led to six different sewer mane breaks, spilling some 230 million gallons of untreated water into neighborhoods, canals and the Tarpon River over the course of three months.

Florida’s water problems are both intertwined with and compounded by factors beyond control: like the state’s geology, with an ever-rising groundwater table thanks to sea level rise, and an eroding, porous, fissure-ridden limestone foundation that underlies most of the state; its geography, with 825 miles of coastline, regularly walloped by tropical storms; and its high urban density, which continues to swell. Ranked 22nd of the states by area, Florida is the country’s third most populous, more than doubling its population in the past 40 years.

And then, there is climate change: Even if Florida could get its infrastructure in check to meet today’s needs, warmer water temperatures, more frequent and intense hurricanes and more extreme king tides throw a wrench in the gears.

Florida’s water infrastructure issues are bubbling to the surface, particularly in the Florida Keys, where rising sea levels

Golf course ponds suffer from an intense algae bloom likely linked to fertilizers applied to the golf course. Photo: Dr. Aaron Adamsin turn raise the groundwater table, seeping through cracks in streets, inundating sewers, busting open pipes and flooding neighborhoods. Climate scientists say these problems will only worsen. By 2040, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change median prediction on sea level rise for the Florida Keys is 10 inches, while NOAA predicts the Keys will see sea levels rise as much as 17”.

Accordingly, public officials recently committed to a plan to spend $1.8 billion over the next 25 years to elevate streets and install new drains, pump stations and other infrastructure to mitigate flooding. The strategy has a few holes, however, perhaps the most glaring being the absence of funding. Without it, officials say, whole communities may be lost to the water.

“Without a change in strategy, parts of the Keys will become accessible only by boat,” Kristina Hill, an environmental planner at the University of California, Berkeley, told The Guardian, describing a vision of canals and floating buildings, like those not uncommon in villages across the Amazonian floodplain. For boatgoing visitors, this possible eventuality doesn’t sound entirely apocalyptic but Hill warned there are other factors to account for: “The islands will gradually disappear into a higher ocean,” she added, “potentially leaving a ruined landscape of leaky underground storage tanks, old pipes, and flooded road segments behind to pollute the water.”

The local Keys government and the state of Florida put a billion dollars into modernizing the island chain’s wastewater system in the 2010s, but there is still much work to be done to ensure critical water quality in the productive waters surrounding the islands. For example, the Keys are still home to dozens of injection wells where sewage effluent is injected into the porous coral and limestone bedrock that underlies the islands. New studies demonstrate leakage from these old wells, with the fouled waters polluting famous angling locations. In fact, there are indications that sewage water injected into wells on Florida’s mainland travel long distances underground and bubble up by the Keys. These problems demonstrate that the Keys conversion of its old septics to modern wastewater treatment is just one necessary step to maintain water quality in and around the island chain. And water quality is critical to maintaining the Keys’ world class fisheries as well as the adjacent coral reef.

The birthplace of flats fishing, the Keys have hosted more world records for tarpon, bonefish and permit than everywhere else in the world combined. But this complex tangle of human and environmental factors have brought about dramatic population fluctuations—including a bottoming out of Keys bonefish in the 1990s—and scientists are still working to understand how it all comes together.

According to Dr. Aaron Adams, BTT Director of Science and Conservation, some of these factors occur hundreds of miles away, in places where the bonefish migrate or spawn. But this species lives the vast majority of its lifespan in the shallows, and a bonefish’s health—and the health of the fishery at large—is very much tied to what’s happening near the shore, especially in this critical habitat around the Keys.

“No one factor can be isolated,” he said, referencing the series of intensive, BTT-funded studies he has overseen of the environmental factors that might influence bonefish population trends. “Many factors interact, but water quality is certainly high on the list.”

An analysis of water contaminants in the canals leading into Biscayne Bay revealed the presence of heavy metals including arsenic and copper along with banned pesticide DDT—all products of agricultural runoff—leading the organization to make agricultural practices and impact a focus area.

And a later study yielded an even more alarming revelation: Some of the bonefish sampled in a recent study were carrying as many as 16 different pharmaceuticals in their systems, from Aspirin to opioids. It appears that drugs flushed down drains and toilets enter the wastewater stream and treatment facilities do not sufficiently remove these contaminants from waters that are released back into the environment in sewage effluent. Adams said it isn’t yet known just precisely how these over-the-counter and prescription antibiotics, antidepressants, pain relievers and hormones impact marine life, but researchers do know they can cause behavioral changes and cloud natural instincts in ways that could jeopardize survival.

These contaminants can do weirder things, too, he said, referencing studies in which the presence of hormone mimickers in rivers from the Thames to the Potomac were causing male fish to change genders and even develop ovaries.

In countries including Sweden, technologies have been put into play to filter pharmaceuticals out of the water supply, but in the U.S., Adams said, trace amounts of drugs aren’t caught by the standard water treatment systems we have in place, and to date, they are unregulated, flowing into coastal waters unchecked.

This map shows the locations of known septic tanks in Miami-Dade County. Based on water table levels, 56 percent of the County’s septic tanks have less than 2 feet of dry ground at some time during the year, meaning that they are not properly filtering waste. A majority of septic tanks in the County are also on small lots in densely-developed north Biscayne Bay, where they are contributing to water pollution. Map: Miami-Dade County

According to Adams, one key source of these contaminants is dysfunctional septic systems—and in addition to geological, geographic and climate factors, this is an aspect of Florida’s problematic water infrastructure that sets it apart. There are some 21 million septic systems in use in the U.S. today. In Florida, nearly one third of all households have septic—about 2.6 million statewide—making up more than 10 percent of the nationwide total.

Yet, these systems were explicitly not designed for densely populated, low-lying coastal environments like the vast majority of the state. For one thing, in order to function properly, septics need at least two feet of dry ground around their leach field. In Florida, especially on the coast, that dry ground is disappearing fast.

Take Miami-Dade County: According to the Miami Waterkeeper, more than half the county’s 120,000 septic systems are currently compromised. By 2040, as the water table creeps higher, that percentage is expected to increase to about two thirds. When these systems fail, runoff carries toxins into the nearby water supply, begetting the algal blooms, seagrass die-off and fish kills Florida is seeing more and more of.

When BTT was founded 25 years ago, the organization was intensely focused on research to understand a valuable

recreational fishery showing signs of decline. Today, science is still the solid ground in which all the organization’s positions are rooted, but according to Jim McDuffie there is a growing focus on applying that research to rally for tangible change.

This shift is especially necessary when problems so sprawling, convoluted, and politically entangled as Florida’s water infrastructure issues have such a make-or-break impact on its recreational fisheries, McDuffie said.

“We never imagined that BTT would be walking the halls in Tallahassee or in D.C. advocating for wastewater infrastructure, but that’s where we’ve landed,” he said. “Our research has again pointed to a serious concern—a threat to flats species. What does it all mean? How are we going to affect change? It means very little unless we’re able to use our research, in this moment, to influence policy.”

BTT has been successful in recent efforts to tackle conservation issues at a policy level, McDuffie said, moving the dial to protect Florida’s recreational fisheries. The organization successfully advocated for the passage of bonefish and tarpon catch-andrelease regulations. A permit research project, funded by Costa Sunglasses, led to an extension of the closed harvest season to protect spawning permit and the subsequent seasonal no-fishing closure of Western Dry Rocks, the most important spawning site for flats permit in the Lower Keys. BTT’s work on juvenile tarpon habitats has led to changes in habitat restoration strategies by government agencies. And in the ongoing effort to restore the Everglades, BTT advocated aggressively for the authorization and funding of the new southern reservoir and fast-tracking of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Project plan.

McDuffie said what BTT is learning in its research about the impacts of Florida’s failing water infrastructure is framing a new priority for the organization, which includes a call for septic conversion and sweeping modernization of sewage systems. But it won’t be a quick fix. Truly solving the problem will require not only a reconfiguration of priorities by residents and leadership, but the

notable issue of some tens of billions of dollars in expenditures, per an estimate by the American Society for Engineers.

As the anticipated costs mount, the can gets kicked down the road: “Repairs to failing systems, septic conversion, and modernization have been somewhere on the to-do list of state and local governments for years, but there’s always something else higher on the list,” McDuffie said. “Septic tanks are underground. So were those decades-old pipes that burst in Fort Lauderdale—out of sight, out of mind. Competing priorities and a problem largely out of public view explains, in large part, why very little has been done.”

This caliber of change never happens in a straight line, McDuffie said, but today, he feels optimistic. Last spring, the Florida Legislature passed, and Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law, the Wastewater Grant Program, which will allocate $500 million in Federal funds over the next five years as well as $116 million in recurring dollars from documentary stamp revenue. This is in addition to $500 million appropriated at the governor’s request for climate resiliency planning, which McDuffie said offers additional opportunities to address water infrastructure needs.

As if the wastewater treatment challenges aren’t enough in their own right, the effects of longstanding policies in how Florida deals with other types of nutrient-laden water are also coming home to roost. This includes stormwater runoff, which although partly addressed is still a major issue. And runoff of nutrients from fertilizers used in agriculture and residential neighborhoods. But perhaps the notable recent impact of poor past policies is the spill of nutrient-laden water in Tampa Bay.

Just this spring, the waste storage facility at Piney Point, along the shore of Tampa Bay, suffered a failure. To prevent a total collapse of the earthen dam that holds untold millions of gallons of contaminated sludge and water, which would have inundated nearby neighborhoods, upwards of 200 million gallons

of contaminated wastewater was pumped into Tampa Bay at Port Manatee—a discharge sanctioned by the Florida DEP. The director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program compared the impact to that of dumping approximately 100,000 bags of hardware-store fertilizer into the bay over the course of several days.

Not long after the Piney Point discharge—which contained high levels of nutrients—upper Tampa Bay began to experience a red tide that has grown in size and intensity. Although a direct cause and effect between the discharge and this red tide occurrence will be difficult to determine, it’s rare for red tide blooms to begin and remain in upper estuary waters. Ultimately, six Gulf Coast counties would be affected by what has come to be known as a “Florida red tide”—so called for the red color of the bloom’s signature toxic organism Karenia brevis—which makes the water unswimmable, causes respiratory distress in humans on land, and kills fish. After a prolonged red tide event in 2018, state agencies reported cleaning up thousands of pounds of dead marine life. The red tide in Tampa will forever be linked to photos of front-end loaders dumping thousands of pounds of dead fish into dumpsters along Tampa Bay beaches. There is still a long way to go on many fronts, but McDuffie sees a sea change taking place.

“I think there’s greater understanding today that the state’s future across every sector will depend upon how well we deal with these issues,” he said. “There’s also a greater commitment, galvanized by harmful algae blooms, red tides, fish kills, closed beaches, and the increasing recognition that lost juvenile habitats are impacting fish populations. We need to nurture that commitment and help translate it into action in Tallahassee and DC. From our own mission perspective, it’s no over statement that the future of a multi-billion-dollar recreational fishery may be at stake. We can’t afford to lose it.”

Alexandra Marvar is a freelance journalist based in Savannah, Georgia. Her writing can be found in The New York Times, The Guardian, Smithsonian Magazine and elsewhere.

Acoustic telemetry is rewriting the book on what is known about the movements and habitat use of the Silver King, enabling new conservation approaches.

BY MONTE BURKE

BY MONTE BURKE

Tom Evans, the owner of many fly-fishing world records for tarpon, began fishing in Homosassa, Florida, in 1976 and has pretty much fished it every year since, missing only three years during that time. Because he is a seeker of world records, Evans has been a keen observer of tarpon behavior in Homosassa and, in fact, kept a meticulous logbook full of notes detailing every day he spent on the water there for 24 of those years. Among the most striking revelations from his observations and logbook, particularly in the earlier years, is just how predictable the behavior of the tarpon that migrate through Homosassa was. Every year, the tarpon would show up right around the same date, starting with a slow trickle and eventually becoming a fullon downpour. The fish would remain in the area—laying up, rolling, traveling in strings, forming daisy chains, sometimes heading out into the Gulf of Mexico and then coming back in—for roughly the same amount of days. And then they would leave at around the same date. There was even a single fish—nicknamed “Spooner” for a distinctive chrome spot on one of its gills—that Evans and other anglers and

guides saw on the flats of Homosassa Bay for decades. The tarpon that Evans observed seemed to move, from year to year, in a somewhat repeatable fashion, either because of instinct or adaptation.

The other striking revelation of Evans’ observations and logbook is just how precipitous and momentous the collapse of the Homosassa tarpon fishery was, starting sometime around the early 1990s. Though one can certainly still find a decent amount of tarpon there today, the great historical run, when there were thousands and thousands of fish around for much of the month of May, no longer exists, and no one really knows where that body of fish went. Of course, this, too, may suggest some sort of repeatability—that the tarpon, for whatever reason, left Homosassa and then began to “repeat” the new behavior. **

The types of observations that Evans and others made in Homosassa (with the exception of annually spotting an

individual fish, like Spooner) are common throughout the inshore portions of the migratory range of tarpon, from Latin America to the Gulf of Mexico and up the southeastern Atlantic coast of the United States. Though anecdotal in nature, they are solid and useful. Guides base their seasons on them. Clients plan their fishing trips around them.

Soon, though, the evidence for the manner in which tarpon move may not be solely anecdotal, thanks to research funded by Bonefish & Tarpon Trust (BTT) and spearheaded by BTT Research Fellow Dr. Andy Danylchuk and Dr. Lucas Griffin of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Danylchuk and Griffin, along with BTT and a handful of other scientists, have produced a research paper that details a four-year tracking study of 200 adult and juvenile tarpon that demonstrated that, yes, the migratory movement of tarpon is, for the most part, repeatable. The paper has been submitted for scientific review.

Danylchuk and Griffin’s research has some significant implications for tarpon angling—anglers and guides may be able to better understand their quarry. But, more important, it may also help with the conservation of the species and, perhaps, help prevent what happened in Homosassa several decades ago and what, alarmingly, appears to be happening in the Lower Florida Keys right now.

lacking. We know much more about the life cycles, spawning routines and general movement of, for instance, tuna, salmon, cod and orange roughy than we do of tarpon. Research funded by BTT on tarpon movement patterns is a big step in gathering more information about the species.

Danylchuk, Griffin and BTT began the ambitious tarpontagging program in 2016. With the help of fishing guides in places like Apalachicola, Tampa, Charlotte Harbor, Indian River Lagoon, Georgia, South Carolina and the Florida Keys, they were able to place acoustic telemetry transmitters in some 200 adult and juvenile tarpon (the biggest tarpon they tagged was 165 pounds; the smallest was 10 pounds). The acoustic tags allowed scientists to track the tarpon for a much longer period (five years) than a satellite tag (a month or two) would, and allowed for more frequent location “pings,” thanks to the various receivers set up in coastal waters. (Danylchuk, Griffin and BTT were able to get shared information from receivers operated by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, among other entities.) The drawback of the acoustic tags is the range—when the tarpon swim into deeper waters, they are usually unable to be tracked. Still, with the large number of receivers along the coast, a pattern of movement can be ascertained.

Tarpon have never been a commercially viable food fish, and because of that, scientific inquiry into the species is seriously

In the Florida Keys, the study tracked more than 50 fish. Of that group, 10 were juveniles. This collection of fish exhibited some interesting habits. They migrated to the Keys after the winter, arriving from multiple spots—Miami, Cape Canaveral, Tampa and the Everglades among them. Some of the fish would

stay in the Keys for a week or two and then suddenly leave, with the next detection a few days later in Georgia or South Carolina, before heading back to the Keys and migrating north along the coast. One fish they tracked did multiple migrations and then went to the Chesapeake Bay until the early fall before moving south again. “What we found was that these fish traveled incredible distances, more than we ever thought before,” says Griffin.

The tagging data demonstrated that the adult tarpon stayed in the Keys between 40 and 60 days on average, and that none of them stayed there year-round. (Some of the juveniles, did, however, appearing to join in some of the migration and then stopping in the middle of it, as if learning how to migrate in increments). According to Griffin, what this suggests is that the Keys are a hub for tarpon, an important area they use as a staging ground before they spawn in deeper water.

But what prompted the tarpon to arrive in the Keys when they did? To get that answer, Griffin cross-referenced the arrival data with lunar cycles, sea-surface temperatures and what’s known as the “photo period,” which is the amount of sunlight during the day.

The entire population of fish arrived in the Keys when the seasurface temperature was between 78 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit in April and then left when the temperature was between 80 and 84 degrees in June. But when Griffin looked at individual fish, he discovered something interesting. “We wanted to see if an individual fish arrived in the first week of April one year, would it do it again the next year and the year after that?” says Griffin. “The answer was ‘yes.’ We saw that individual fish were incredibly repeatable when it came to their arrival,” he says. While the temperature might influence migratory movements, “the photo period at the individual level, and not temperature, is the likely driver of arrivals.” This makes some sense since temperatures fluctuate dramatically and would be harder to time, of course.

So what does this mean for anglers? For one thing, it means that if you fish for tarpon in the Keys around the same time every year, it’s likely that you are fishing over the same body of fish. And that knowledge—and relationship with the fish, really— comes with some stewardship obligations, especially given the importance of the Keys to the tarpon life cycle. “If anglers aren’t careful, they can have a direct impact on a certain body of fish,” says Griffin. Being careful means playing tarpon as quickly as possible. It means moving if sharks are in the area being fished. It means handling all caught tarpon with care.

It also means that habitat—which is under pressure now from water quality issues, dying seagrass and lack of proper freshwater flow in the Everglades—needs the necessary attention. Given the lack of funding or, really, care from government agencies (which assumes that catch-and-release fisheries are regenerative), most of the responsibility for tarpon is placed in the hands of those of us who target them as a sportfish.

variable in terms of how they move. “They’ll be there even if it’s cold and blowing 30 miles-an-hour,” says Collins. “They’ll just hunker down then in the channels and not swim the shallower water. But there always comes a time when that big push comes and they start to swim.” Says Ponzoa: “The fish definitely come in about the same time, starting to show up on the outer ridges of the Gulf. When we’ve had three to four days of good weather, we start looking.”

All three guides agree that the population of fish from the Middle Keys to Key Largo seems stable. The tail end of the season has appeared to thin a bit in terms of numbers, according to Collins, but, all in all, the fish and their movement have remained fairly predictable.

All three guides, though, also agree that there is something potentially catastrophic going on with the large population of tarpon that used to swim each year from Key West to roughly Big Pine Key. “There’s a big body of fish missing,” says Ponzoa. “They used to come in on the northern reaches of Big Pine, from Sideboard Bank coming west. That area, all of the channels and basins, used to fill with these tarpon. But we can’t find them anymore.” Says Collins: “Something has majorly changed down there. Key West Harbor is not loading up with fish. The tarpon used to lay up in Seaplane Basin, but they don’t anymore. Something has happened. There’s been a mass exodus.”

Because he’s based in Key West, Gable has been a firsthand, almost daily, witness to the change. “We started to see something about six years ago, small changes to the fishery and its patterns,” he says. “There were fewer fish traveling the traditional migratory routes. Some tarpon started coming in perpendicular to the shore as opposed to swimming parallel to it. And now, they seem to be gone for the most part.” Gable says that, for now, he still has a bit of a tarpon-fishing season each year in his area. But he’s scared it might not last for much longer. “If we continue the rate we’re on, I think we’re going to lose this fishery completely,” he says.

Tarpon are an ancient species, dating back, in current form, around 50 million years. During their time on earth, they have survived the extreme heat of the early Eocene Epoch, the extreme cold of the Pleistocene’s ice age and a massive die-off of the earth’s large animals that happened 13,000 years ago. They also, as individuals, can live to an old age—radiometric dating indicates that they can live to up to 70 or 80 years. They have proven to be highly adaptable.

They can certainly become habituated to human behavior— the fish that are fed daily by tourists at Robbie’s Restaurant and the fish who appear to purposely stay in the “no-fishing” zone at Bud & Mary’s Marina in Islamorada certainly illustrate that.

It makes some sense that if tarpon can become conditioned to the food and safety that humans provide them, they can also become conditioned to any human-caused sign of danger or discomfort.

The conclusions from the acoustic telemetry study jibe fairly well with the folks who spend much of their time on the water, in constant contact with these tarpon: the tarpon guides. Scott Collins and Albert Ponzoa, out of Marathon, and Don Gable, out of Key West, all agree that the fish show up in the Keys generally around the same time each year. Weather, though, can be a

Tarpon have also disappeared from certain of their oncefavorite spots in the world. Port Aransas, Texas, was a famous tarpon-fishing destination in the 1930s and 1940s. At the height of its popularity, hundreds of tarpon were caught and killed during every day of the season there. Water quality issues also plagued the area around that same time. By the 1950s, the Port Aransas

fishery was no more.

In Homosassa, though the fishery remains, it’s merely a remnant of what it used to be. Killing fish wasn’t the culprit of the decline. But boat traffic (Homosassa exploded in popularity once word got out about its big fish, and 20 boats on the water per day quickly became 100) and environmental degradation (decreased flow and more pollution in the freshwater springs that drained into Homosassa Bay) are the more likely culprits. This was a population of fish that repeated its behavior, perhaps for centuries, and then suddenly stopped, most likely from humanimposed conditions.

The causes of the missing population of fish in the Lower Keys—which Griffin says were part of the impetus for the tracking study—remain a mystery. But, again, most likely, it has something to do with us. Perhaps it’s the dying seabed in Key West Harbor? Or the pollution? Or oil spills? Or maybe it’s simply too much cruise ship, pleasure boat and jet ski traffic in the area? Tarpon migration has everything to do with maximizing “growth, survival and reproductive success” as Griffin writes in his paper. Human interference can get in the way of any or all of those things.

We may never know for sure why tarpon appear to have left the Lower Keys. But what’s become clear from Griffin and BTT’s new work is that humans and tarpon are in this together. And we need to focus increasingly on ways in which we can hold up our end of the bargain.

Monte Burke is The New York Times bestselling author of Saban, 4th And Goal and Sowbelly. His new book, Lords of the Fly: Madness, Obsession, and the Hunt for the World-Record Tarpon, is available now. He is a contributing editor at Forbes and Garden & Gun.

As rebuilding efforts continue in the aftermath of one of the region’s most deadly hurricanes, East Grand Bahama serves as a gateway to an even slower recovery process: the restoration of red mangrove forests in the Northern Bahamas.

It has been two years since Hurricane Dorian made landfall on Abaco and Grand Bahama, and in that time residents have been trying their best to get back to some form of normalcy. Dorian hit in September 2019, leaving behind billions of dollars’ worth of damage in its wake—and that does not begin to compare to the human lives affected and lost.

As members of the East Grand Bahama community continue to rebuild, just off the coastline lies a dead forest on the flats, a ghost of what was. These flats once housed vibrant mangrove forests that were home to a variety of birds and fish. These mangroves were the cornerstone of a fragile ecosystem and

acted as a refuge and nursery for animals of both the land and sea. Between Abaco and Grand Bahama, Dorian severely damaged or destroyed 69 square miles of this vital ecosystem.

Culturally speaking, Bahamians have lived off of the ocean since our forefathers were brought to the islands. With seafood being such a bedrock to Bahamian culture and mangroves supporting so much marine life, it would only make sense that locals would want to help revive and conserve such a delicate ecosystem. Grand Bahama lost 74 percent of their mangroves while Abaco lost 40 percent. This kind of loss creates longlasting ripple effects within the country, not just these specific communities.

A year ago when the topic of mangrove restoration was raised, it seemed like a daunting task. With so much going on in the world at the time, no one could deny that the project at hand would be a difficult one. But despite the many challenges,

more than 10,000 mangrove seedlings have been planted since December 2020 for Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s Northern Bahamas Mangroves Restoration Project. This crucial work was done in partnership with Bahamas National Trust, Friends of the Environment (FRIENDS), and MANG Gear, a Florida-based apparel company.

Transporting and raising mangrove seedlings requires a great deal of planning and care. Donated by MANG, thousands of seedlings were transported from Florida, delivered to nurseries in the Northern Bahamas and then planted in the devastated flats in the Northern Bahamas. Additionally, many seedlings have been collected and grown here at home in the Bahamas, in three nurseries setup on Grand Bahama and Abaco. This ambitious, multi-year project has many moving parts and relies heavily on community stakeholders to make it happen. One way to mobilize community members is through hosting planting events.

So, how are areas most in need of restoration identified?

“The planting sites were chosen based on what was there before compared to what remains,” explained Justin Lewis, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s Bahamas Initiative Manager. Choosing a specific site partly depends on the pre-Dorian presence of adult red mangroves versus dwarf red mangroves. “Although we have only one species of red mangroves in the Bahamas, we see two different forms; the dwarf mangroves that dominate the flats, grow slowly, usually don’t get taller than chest high, and rarely produce seeds (propagules), and larger, seed-bearing mangroves that tend to grow next to blue holes and along creek edges with consistent water flows to provide more nutrients than found on the flats.”

Mangrove restoration has a higher chance of success when the seedlings are planted in areas that naturally support seedbearing mangroves. This is because mangrove growth rates are

higher in these areas, so the seedlings have a better chance of growing more quickly and becoming large enough to produce propagules. These propagules are then carried by currents to the flats, where they contribute to natural recovery. It’s for this reason that Roemer Creek on East Grand Bahama was chosen as the site for the project’s first community planting event. Roemer Creek contains sediment that promotes growth of seed-bearing mangroves, and the channel that runs through it enhances the dispersal of seeds to surrounding impacted areas.

On May 8, 2021, more than 60 volunteers, students, government officials and bonefish guides met at McLean’s Town in East Grand Bahama at the Government Dock, a gateway to other islands and cays in the Northern Bahamas for many generations. Planting event attendees were then ferried by several boats driven by local guides to the north mouth of Roemer Creek, eager to lend a hand in restoring mangroves that directly support East Grand Bahama’s iconic flats fishery and help buffer McLean’s Town against storms.

“Work like this is important—without mangroves I would basically be without a job,” said Livingston Tate, a bonefish guide from Sweeting’s Cay who helping to engage the angling community in the project. As a resident of East Grand Bahama, Tate has a vested interest in seeing his communities bounce back in every way imaginable. His boat was among the three vessels ferrying participants from the mainland to the planting site.

After breaking off into pairs, the volunteers were sent out into the flats, each armed with a bucket filled with seedlings and a shovel. One member of the pair was instructed to dig the hole into which the other inserts the seedling. Simple enough, right? Not necessarily. For those less familiar with this landscape, moving through the mudflats is like maneuvering through quicksand, and watching the volunteers partner with one another to plant individual mangroves seedlings was both a hilarious sight and yet a heartwarming one when you realized just how much effort and care it takes to move from one spot to another.

“From the initial test planting we’ve done to the first community planting event, everyone has been a volunteer, everyone has been pitching in from the local community,” said Lewis, underscoring the importance of community engagement to the success of the project. “That’s the basis of this project—to have the community involved, trying to give back to their island, trying to get the Northern Bahamas back on track.” As Lewis speaks, one can recognize that this is such a critical aspect of the project: having local residents take ownership of a project in which they have the greatest stake.

It’s impossible to traverse the waters of the flats with any kind of grace, but Jewel Beneby, a science officer with the Bahamas National Trust, definitely moves through them with a determined force. “Everyone should care about what happens to the mangroves and about this entire restoration process,” she said as she planted the final seedling in her bucket. “Mangroves are one of the keys to climate resiliency in Small Island Developing States.”

She’s more than right. Beyond acting as an incubator for new marine life and a vital habitat that support biodiversity, mangroves diminish the power of hurricanes, and as climate change continues to be a threat to Small Island Developing States, storms are becoming more frequent, more powerful, and more deadly. It would be a gross understatement to say that mangroves are merely important: They hold the potential to be lifesaving. “What we’re doing out here is more than just community service,” said Beneby. “It’s helping jumpstart Mother Nature after something so key to our climate resilience was torn away.”

With 10,553 mangroves planted to date, community members have played an integral role in the project’s success. It could be seen in the busload of students that took

the hour-long drive from city center Grand Bahama to East End in order to participate in the inaugural planting event. Rachelle Manchester, an 11th grader at Bishop Michael Eldon School, describes herself as someone who not only loves the environment but wants to see it thrive. Rachelle is a student who is not new to environmental advocacy, and has done volunteer work with movements like Save the Bays, a Bahamian movement dedicated to fighting unregulated development and environmental degradation. “I’ve always been interested in getting out there and dealing with Mother Nature,” Manchester said. “This event was the first time I had seen the mangroves

since the storm and it was honestly just devastating. I’m really happy I can do my part. “

Educational outreach has also been a key component of the project. BTT has been working closely with FRIENDS on Abaco to integrate mangrove planting in their summer activities. During their camp this year, the kids in Abaco are projected to plant more than 1,000 mangroves on their home island.

As eager as we may be to see the mangroves restored to their former glory, the steps that are being taken now are only introductory ones. The Northern Bahamas Mangrove Restoration

Project indeed will be a project that’s playing the long game. As Lewis indicated, it will be years before we begin to see the mangroves as vibrant as they once were, welcoming a plethora of fish, lobster and bird species into their fold and doing their job to fight off the force of powerful waves by acting as a storm break. That is why it is important that we do our job, by planting, educating and volunteering our time to ensure that we help Mother Nature as much as she helps us. By volunteering time and effort to mangrove restoration, Northern Bahamians have decided to bet on themselves and their futures, ensuring that their children are able to reap the benefits of decisions made long before they were born.

The restoration project doesn’t just represent the fight for climate resiliency. It also speaks loudly to the undercurrent of the resiliency of a people who have lost everything other than cultural pride and passion. It speaks volumes to the ways in which they are willing to fight for cultural preservation within their communities through environmental restoration. It’s the fight that most island states are facing, and it’s one that many Northern Bahamians have now been thrust into. The willingness, however, to rebuild in every facet of the word, is the reason why soon enough, green will replace grey and life on the flats will be restored.

Ashleigh Sean Rolle is a Bahamian writer who calls Freeport, Grand Bahama, her home. She writes for the site 10th Year Seniors, where she regularly shares her opinion on everyday Bahamian affairs. She is a contributor for Huff Post. Her work has also appeared at CNN.com.

BY T. EDWARD NICKENS

BY T. EDWARD NICKENS

Captain Rick Ruoff was running late, a not-unusual circumstance when the fish were biting and he was a long way from home. With angler Bill Levy on the bow, he was making the 20-mile trek from Key Largo to Islamorada, deep into an early 1990s November afternoon. It was calm and he was in a hurry, so he ran a bit offshore, in some 15 feet of water. “I took a course straight down the beach,” he recalls, “and I saw these tails zipping out of the water in front of us. I said to Bill, Holy hell, what is that? And it was a ball of bonefish. Thousands of them, tumbling like a bowling ball. The bottom fish would come up, and the top fish would go down.”

Ruoff eased up to the school, and Levy cast and almost instantly had a fish. Then he hooked another. Ruoff backed the boat away to keep from disturbing the school, and said to Levy, “Let’s just sit here and watch.”

He and Levy watched the bonefish boil at the surface for nearly an hour, until the falling sun prompted the men to head for port. Ruoff, who has guided for 52 years, shakes his head at the memory. “It was incredible,” he says. “I had not seen anything like

that before, and I haven’t seen it since. But boy did I get a good look then. And I feel pretty honored to have seen it just once.”

At the time, Ruoff wasn’t certain what he’d witnessed. But now he knows what stopped his skiff cold that late November day. It was a pre-spawning aggregation (PSA) of Florida Keys bonefish, a phenomenon that has been shrouded in mystery for decades.

Ruoff’s story—and a double handful of similar recollections told by other long-time Keys fishing guides—has helped refocus a project essential to Florida Keys bonefish conservation: The search for bonefish pre-spawning aggregations in the Florida Keys. The project will expand in the fall of 2021, combining technology with guide observations in an effort to solve one of the most intriguing mysteries on the Florida flats: Where do Florida Keys bonefish spawn?

The answer is a missing link in the scientific understanding of what is known about Florida Keys bonefish reproduction.

Recent research has provided tantalizing clues, including four probable PSAs reported by fishing guides. Two years ago,

BTT scientists outfitted Keys bonefish with acoustic transmitters to track their initial spawning migrations. “On a full moon they swam as many as 30 miles,” says Dr. Ross Boucek, manager of BTT’s Florida Keys Initiative. “One fish tagged at the Content Keys migrated 45 miles through the backcountry out to the reef. The fish was last detected at depths greater than 110 feet, presumably on its way to spawn offshore. Not only are we narrowing down the areas where to look, but from the tracking information, we’re also getting a clearer picture of when to be out in the water at these sites. This is a great foundation for the work that will unfold over the next three years.”

Based on findings in the Bahamas, scientists know these movements are the opening act in the full drama of the spawning season, and that bonefish gather in huge aggregations that could number in the thousands before heading to deep water to spawn. Over a decade of hard work, BTT scientists interviewed guides to identify possible pre-spawning locations, sampled bonefish hormones and eggs to estimate peak spawning times, and tracked fish from their home ranges to spawning areas.

The results? At least seven PSAs have been identified and three protected by the Bahamas through national park declarations. But despite intense scientific scrutiny—and within the context of their impassioned pursuit by anglers—the locations of these spawning areas in the Florida Keys, if they exist at all, have been an elusive target. While a years-long effort in the Bahamas has identified multiple PSAs in that archipelago, finding these critical sites in the Keys has involved decades of dead ends. Now, thanks in large measure to the support of Keys guides, BTT is taking the Bahamian playbook of oral history, acoustic monitoring, spatial analysis, and hard-boiled detective work to a new level on the southern flats of the Sunshine State. And time is of the essence.

“Discovering these spawning sites is the first step to learning what stresses our bonefish may face when they spawn in the Keys,” says Boucek. “Once we find these sites and identify stresses spawning bonefish face, we can work through advocacy and education channels to fix problems and ensure our bonefish can spawn. This will ensure a sustainable population.”

Pinpointing these locations will also connect other pieces of

the puzzle, beginning with a greater understanding of how much of the Keys bonefish population is a result of local spawning in the Keys versus larvae drifting in from neighboring countries.

“Finding spawning bonefish in the Keys will answer the questions conclusively about where Keys bonefish come from,” says Carl Navarre, chairman of the board of BTT, who believes documenting spawns will fill gaps in our knowledge left by ocean modeling and genetic analysis. “And if we’re able to find spawning bonefish, and track them like we have in the Bahamas, it will give us a tremendous amount of information on how to better protect them and manage the fishery.”

What makes the timing of this project so perfect is a mix of new technology and old-school sleuthing. As Florida Keys bonefish numbers crawled out of the basement over the last few years, acoustic telemetry technology has matured, and the meteoric rise of drone technology and its applications in the science realm have given researchers new ways of looking for fish aggregations. For the cost of a single hour in a helicopter, BTT could purchase a drone and use it whenever needed.

And critically, there’s been a shift in how anglers in general and flats guides in particular view the role of science in informing fisheries management. BTT has worked strategically to deepen relationships with the flats guiding community around the Caribbean. When Navarre was elected a board member in 2017 and then board chair in 2020, he brought to BTT a deep connection to many Florida guides. A former guide and founding director of The Guides Trust Foundation, one of Navarre’s early signature projects began in the fall of 2020 when he reached out to a few dozen Florida Keys guides to engage them in a cellphone app project to report on the population health of bonefish, tarpon, and permit in the Keys. That initiative, Navarre recalls, “gave us plenty of useful information, but it also opened up lines of communication and started building relationships with guides.”

That is fundamental to the search for bonefish PSAs in the Keys. This past spring, Navarre reached out again, and he and Boucek interviewed seven guides with international reputations

to kick off the search for the spawning areas. Between them, Timmy Klein, Harry Spear, Mark Krowka, Rob Fordyce, Bob Branham, Eddie Wightman, and Rick Ruoff have some 200 years of experience on the water. Those guides, as well as others in the Lower Keys, listed 19 different areas where they had seen bonefish PSAs, most occurring in the 1980s and 1990s when Keys bonefish populations were particularly healthy.

Hearing the reports, Boucek was stoked. “In some cases, four or five guides had seen fish at the same place,” he says. As word spread, more guides called in. At two different sites, guides reported seeing bonefish aggregations where there had been similar reports decades earlier. “That was very exciting,” says Boucek. “Those were reports from the same place, during the same time of year, and in the same moon phase where groups of fish had been reported 30 years earlier. Those PSAs were there for a time, and then for years there were no reports at all. Now it seems they are showing up again.”

With the Keys experiencing a significant rebound in fish large enough to spawn, the time for a dragnet approach to discovery seems particularly ripe. In the fall of 2019, BTT tagged 30 bonefish between the Marquesas and Biscayne Bay to begin analyzing possible migration routes to suspected PSAs. Boucek honed his drone-flying skills through dozens of test flights over open water. In the next phase, BTT will be testing a new generation of acoustic tags that will reveal the maximum depth attained by tagged fish, which should help pinpoint the dates when bonefish spawn since they only head for deep water to spawn.

With the excitement comes a renewed sense of purpose. No one knows how long the current bonefish revival will last. “We can’t say if this is a sign of good things to come,” says Boucek, “or if this is an anomaly. We don’t know if they’ll be around in five years. With so much uncertainty, there is an urgency to find them now.”

Here’s how it will work: Pulling together all the available data, BTT has assembled a short list of 11 locations for further scrutiny, and now the cat-and-mouse game begins. Starting this fall, Boucek and a small team will run BTT’s 22-foot Pathfinder to a suspected location during the full and new moons, and fly a drone in a grid search pattern from noon to sunset. “The expectation is that the aggregation should get more organized and be more visible at the surface the closer you get to sunset,” says Boucek. The team will search for two days on both the full and new moons, from November to May. Boucek figures there is still plenty of room for trial and error in the process, but with each passing month the target areas should come into greater focus. “It’s like catching lightning in a bottle,” he explains. “We think we have the bottle. We just need the lightning to show up when we have it in our hands.” Bonefish don’t spawn on every new or full moon, and weather conditions have to be right to run the boats at long distances at night.

Navarre doesn’t discount the difficulty of the undertaking. “This is not an easy thing to do,” he cautions. The process in the Bahamas, he notes, unfolded over many years. The Keys search, he figures, could take five years or more. Or the search team could get lucky. “But one thing that will drive success in the Keys is an outreach program for guides,” he continues. “They need to know exactly what we’re looking for and have ways to contact us immediately so that we can have teams ready to go at the drop of a hat.”

And if the PSAs can be found, and the spawning areas identified, opportunities for conservation can become much more

focused. At this point, any management prognostications are premature. What’s most important is for the science to close the circle on the long search for Florida Keys bonefish PSAs. First, Boucek and his team have to catch lightning in the bottle. Carts and horses can wait.

In 1970s and ‘80s, Keys guide Eddie Wightman knew of more than a half-dozen places on the ocean side of the Keys where bonefish would school in groups of 500 or more fish. It was always during colder weather; he could nearly predict when they would show up. He’d run his boat upwind and pole down to the mass of bones, trying to point his angler in the right direction.

“I would tell my client: You see that giant cloud shadow?” he recalls. And he would wait till their hat bills pointed true.

“The cloud shadow,” he would say, “is the bonefish.”

Those were bonefish PSAs; Wightman and others are sure of it. And somewhere off the Florida Keys, the cloud shadows may still lie on the water. No one knows what draws the bonefish, what ineluctable prompting pulls them towards the deep chasms that drop off the flats. Perhaps it’s a certain sort of ocean floor upwelling, or some subtle ocean current or gyre that spins just offshore. But the fish respond to something: They stream over the flats for hours, in wave after wave. A school of 50. A school of 200. Minutes later, more. The aggregation builds into a mindboggling mass until the school makes its move to deep ocean, and dives hundreds of feet below the surface to spawn.

There could be many somewheres-out-there. Or there could be none. But there is now, for the first time, a strategic means to find them.

“There are very few opportunities for discovery on this scale,” says Boucek. “The thought of finding something that people haven’t observed for over 20 to 30 years is exciting, and even more so when you consider that it could have meaningful conservation implications down the road.”

He’s quiet for a moment, considering the next phase of the search.

“And what’s amazing is that they are hidden in plain sight,” he says. “My office looks out over the water, and for all we know, one could be right there.”

An award-winning author and journalist, T. Edward Nickens is editor-at-large of Field & Stream and a contributing editor for Garden & Gun and Audubon magazine. His latest book, The Last Wild Road, published by Lyons Press, is available now. Follow him on Instagram @enickens.

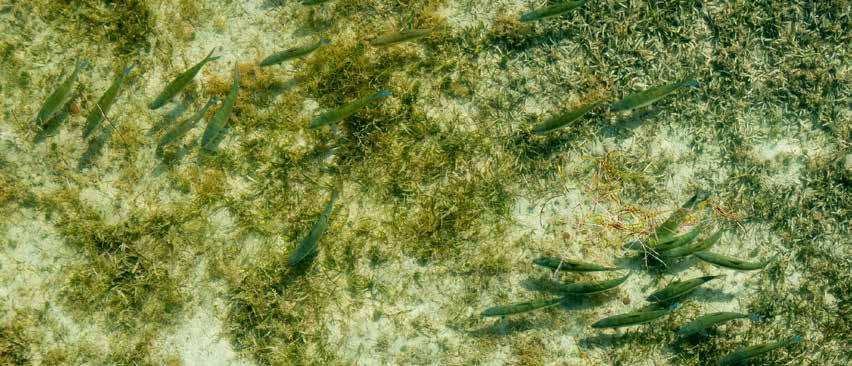

Keys bonefish moving across a seagrass flat. Photo: Tyler BowmanWhether you’re exploring freshwater fly-fishing locations with our on-property helicopters in New Zealand and Patagonia or targeting bull reds and tarpon in Louisiana or South Florida aboard the Outpost Mothership, one thing’s for certain — with Eleven Angling’s collection of owned and operated lodges and motherships, you’ll be on fish, from sunrise to sunset.

There are, by my count, approximately 10,385 stories about Tim Borski, the Islamorada-based artist/fly-tier/naturalist/ homme amusant. My favorite among the select few that are printable in a family publication involves a baseball card.

It goes something like this: When Borski was 16 years old, he lived in a cabin in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, in the central part of the state. Though he was in school, much of his energies were focused elsewhere. Whenever and wherever he could, Borski, along with some of his friends, hunted grouse, woodcock and ducks and fished for smallmouth bass and brook trout, slaking a seemingly insatiable thirst for anything outdoors. On occasion, the boys tried to slake another thirst as well.

One late afternoon, after a day spent tramping through the woods, Borski and his buddies decided to go to a bar in Stevens Point. Borski, however, did not have a fake ID, which would have been his ticket in.

But he did have a plan, one that displayed an early penchant for audacious creativity. At the door of the bar, when asked by the bouncer for ID, Borski first delivered an impish grin. And then he reached into his pocket and handed over a Chili Davis baseball card.

The bouncer looked incredulous as he stared at the picture of the great Jamaican-American baseball player. “Man, this is a baseball card,” the bouncer said. “And, man, you’re not even black!”

Without missing a beat, Borski replied: “Yeah, but ask me how many RBIs I had last season.”

The bouncer shook his head, smiled, handed the card back to Borski and let him in.

From his childhood to his early 20s, the 12,700-acre Buena Vista Marsh, just a few miles from Stevens Point, was Borski’s playground. He hunted its grasslands for birds and fished its spring-fed ditches for brook trout. “I spent so much time there,” he says. “It is such a great place.” It was also, as the name suggests, his first true panorama, something he would realize later in life that was of some great importance to him.

After high school, Borski worked in a couple of factories—one produced pre-made fireplaces and the other produced furniture. “I

was a terrible employee,” he says, a recurring theme in his life. At one of the factories, Borski had a boss who had been there for 27 years. One day Borski asked him about his salary. “The guy was only making $1.65 more an hour than I was,” says Borski. “The next morning I went to the local arts university and applied for a student loan. I had no idea what I wanted to do other than not work in a factory.” He took a class that was “basically Watercolor 101” and thought: “This fits me.”

He would never finish his degree at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. One nice April day, after a long Wisconsin winter, Borski went fishing on a nearby river and caught a boatload of smallmouth bass. “I was so excited to get back out there again the next day,” he says. “I went to bed early that night, woke up and called work and coughed and said I couldn’t make it and grabbed my rods. Then I opened the door and there were nine inches of snow on the ground. I just lost it.”