REPORT SUMMARY

While the UK’s Ivory Act 2018 promises to be an important step towards protecting the world’s wild elephants, large volumes of ivory continue to be sold online both overtly and covertly.

This report examines the scale and scope of the UK’s online ivory market and asks Are Ivory Sellers Lying Through Their Teeth?

KEY FINDINGS

• In one month in late 2021,1,832 overt and covert listings containing ivory were identified across three online sale websites, with a total estimated value of £1,169,356.18.

• Of these listings, 84.9% were overt and 15.1% were covert. The platform which prohibits the selling of ivory (eBay UK) was responsible for 95% of all covert listings.

• The material for the covert ivory items was most often mislabelled as ‘bone’.

• The ivory-bearing animal species for 66.9% of all listings could not be identified. Of the remaining discernible items, 19% were from non-elephant species.

• Although ivory from non-elephant sources forms a minority of the market, there is already an indication that demand for non-elephant ivory is increasing in response to the pending implementation of the Ivory Act 2018.

KEY MESSAGES

Delays in implementing the Ivory Act 2018 have impeded the hoped-for dampening impact on domestic trade and have perpetuated the demand for ivory. In its current form, the Act does not prohibit trade in ivory from non-elephant species, such as hippopotamuses and walruses. Distinguishing the species of origin from online images of ivory items is very difficult in most cases. The legal trade in non-elephant ivory risks enabling elephant ivory to be covertly listed under the guise of a permitted species and may also put pressure on the wild populations of non-elephant species.

Once the Act is implemented, authorities need to ensure any continuing online ivory trade strictly complies with the Act’s limited exemptions and any covert listings are identified and removed.

International wildlife charity Born Free calls on the UK government to ensure the better protection of both elephants and non-elephant species by extending prohibitions to non-elephant ivory.

1. INTRODUCTION

The African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana) and African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) have been recently classified as distinct, endangered and critically endangered species respectively on the IUCN’s Red List (International Union for Conservation of Nature – the world’s largest conservation organisation), with poaching for ivory identified as a major threat to both species (Gobush et al, 2021a; Gobush et al, 2021b). Poaching also threatens the survival of the endangered Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), although there is less data available on the number of these elephants killed for ivory (Williams et al, 2020). Despite the Convention of the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), of which the UK is a prominent signatory, banning the international commercial ivory trade in 1989, elephant populations have continued to decline (eg, Chase et al, 2016; Menon and Tiwari, 2019; Sosnowski et al, 2019; Peez and Zimmermann, 2021) and levels of poaching remain unsustainably high (Lusseau and Lee, 2016; Gobush et al, 2021a; Gobush et al, 2021b).

The most recent seizure report from the Elephant Trade Information System (ETIS) revealed that more than 42 tonnes of ivory were seized globally in 2019, making it the fourth largest annual tally since 1989 (CITES, 2020). The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) reports the UK plays a significant role in the ivory trade (Lau et al, 2016; DEFRA, 2018), with 1.3 tonnes of ivory being seized at UK ports and airports in less than a month in 2020 (Kaile, 2020). While the proportion of illegally traded ivory seized is unknown and doubtless varies between jurisdictions, it is likely that seizures only represent a relatively small proportion of the total amount of ivory in illegal trade. Although large seizures may demonstrate the efficiency of wildlife law enforcement, they also indicate that the ivory trade remains a real threat to elephant populations, and that ivory continues to be in demand in the UK and the rest of the world. Although some have suggested that a regulated legal market for ivory could reduce poaching (Bandow, 2013; Ganesan et al, 2016), this argument has been widely discredited (eg, Harvey, 2016; Hsiang and Sekar, 2016; Lusseau and Lee, 2016; Aryal, Morley and McLean, 2018; Sehmi, 2019; Wilson-Spath, 2019). It is suggested that to resolve the elephant poaching tragedy, consumer demand needs to be reduced through the introduction of domestic trade bans in jurisdictions where ivory trade continues to pose a threat to elephants (CITES, 2019).

The Ivory Act 2018 (hereafter referred to as the Act) promises to be one of the most rigorous pieces of wildlife conservation legislation in the world, by banning the sale of ivory to, from and within the UK with limited exemptions (Cox, 2021). Although the Act gained Royal Assent in December 2018, at the time of writing the Act still has not been enforced due in part to legal challenges, Brexit and the coronavirus pandemic delaying implementation (Cox, 2021). The Chinese government banned domestic trade in elephant ivory in 2017, along with the introduction of associated penalties, and this led to a decline in elephant ivory demand in a country widely regarded as having the largest consumer market (WWF, 2019; WWF, 2021). The general perception in China is that trading elephant ivory is not worth the risk, as the government is taking this crime seriously (Wildlife Justice Commission, 2021a). Therefore, applying the same logic, the Act will likely reduce demand in the UK if it is enforced efficiently, as robust prosecution of violations is likely to encourage compliance among traders (Harris, Gore and Mills, 2019).

Elephants are the most common source of ivory, but teeth from extinct mammoths (Mammuthus species) and from hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius), walruses (Odobenus rosmarus), warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus and Phacochoerus aethiopicus), sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), orcas (Orcinus orca) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros) also feature in the ivory market (IFAW, 2004; Baker et al, 2020; IFAW, 2020; Moneron and Drinkwater, 2021). The population trend for extant ivory-bearing species is either unknown or decreasing according to their most recent IUCN Red List assessment (de Jong, Butynski and d’Huart, 2016; de Jong et al, 2016; Lowry, 2016; Lowry, Laidre and Reeves, 2017; Reeves, Pitman and Ford, 2017; Taylor et al, 2019), with the exception of the hippopotamus, whose population trend is described as ‘stable’ in spite of hunting for ivory being identified as a primary threat (Lewison and Pluháček, 2017). Although the trade in non-elephant ivory is widespread and well-established (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2014; Baker et al, 2020), there has been little research into the prevalence of ivory from non-elephant sources in the UK.

In its current form, only elephant-derived ivory is prohibited by the Act, although DEFRA recently called for more information regarding the trade of non-elephant ivory (DEFRA, 2019). There are concerns that limiting the prohibition on domestic commercial trade to elephant ivory in the UK may lead to other ivory-bearing species being unsustainably exploited as a legal substitute (Andersson and Gibson, 2017; Moneron and Drinkwater, 2021), and elephant ivory being covertly listed under the guise of a permitted species. Recent research has revealed that elephant ivory items are sometimes mislabelled as mammoth ivory on Japanese e-commerce websites which prohibit the sale of elephant ivory (Nishino and Kitade, 2020). Banning the trade in mammoth ivory has been suggested as a necessary supplemental measure to an elephant ivory ban (Harvey, 2016).

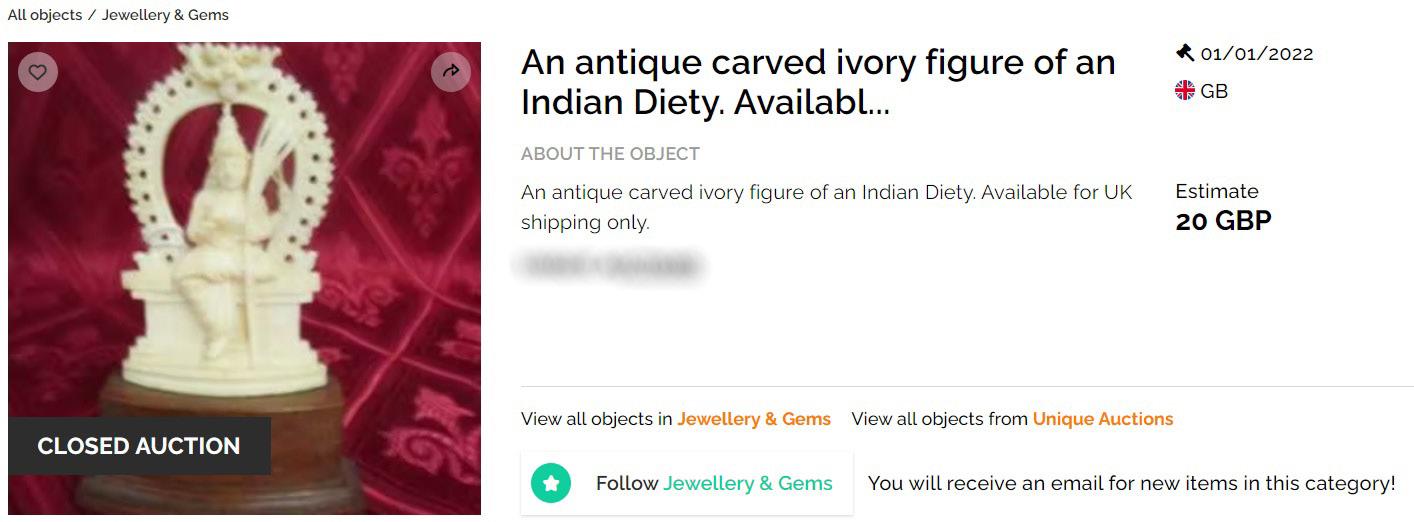

As very little ivory is traded using the dark web (Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro, 2016), it is likely the majority of ivory is available on the surface web. The UK ivory trade is most prevalent online, with many ivory items being offered through antique search services (Two Million Tusks, 2017). A popular search service is Barnebys, a website used by a range of auction houses in the UK (Barnebys, n.d.; Lau et al, 2016). Ivory items are also available directly through antique dealers. For a fee, dealers can feature their stock on websites such as Antiques Atlas, which is the UK‘s biggest antiques directory and online catalogue (Antiques Atlas, 2022).

Sellers may also list their ivory items on general online marketplaces, such as eBay. The trade in ivory on eBay is still ongoing despite the company introducing an ivory ban policy in 2009 and joining the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online in 2017 (IFAW, 2012; Hernandez-Castro and Roberts, 2015; Yeo, McCrea and Roberts, 2017; Alfino and Roberts, 2020; Venturini and Roberts, 2020; Wildlife Justice Commission, 2021a). Ivory items are frequently sold on eBay under different code words, with eBay UK having the highest volume of ivory items for sale under these code words compared to France, Italy and Spain (Alfino and Roberts, 2020). Examples of ivory code words are ‘ox bone’ and ‘faux ivory’ (IFAW, 2012; Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro, 2016). Items which are often made from ivory, such as netsukes (small, carved ornaments) are being covertly sold on this platform using various codenames (Venturini and Roberts, 2020).

Although the majority of ivory available online in the UK appears to have been sourced from elephants, ivory from hippopotamuses, walruses and whales was also identified in a recent study (Parry, 2021). Without physical access to the item, efforts to identify the species the ivory is sourced from are limited to examination of online images for distinctive, species-specific markings. An identification guide for ivory and ivory substitutes was put together by WWF, CITES and TRAFFIC (the wildlife trade monitoring network) which describes the distinctive markings for each ivory-bearing species (Baker et al, 2020).

In short, elephant and mammoth ivory has Schreger lines, which are distinctive cross-hatchings seen in cross sections of the item. Elephant and mammoth ivory can be distinguished as the Schreger lines perpendicular to the cementum on mammoth ivory tend to have angles that are less than 100°, whereas modern elephant Schreger angles, on average, are greater than 100°. Walrus ivory is most easily identified by the presence of secondary dentine. Hippopotamus and warthog ivory can be distinguished in images by the shape of the tusk interstitial zone, if present. Also, both hippopotamus and warthog ivory cross-sections show tightly packed concentric lines, but these are less regular on warthog ivory. Whale ivory cross-sections have prominent concentric rings and species of whales can be distinguished by the shape and size of the tooth.

The aims of this study were to estimate the volume and value of covert and overt ivory available to buy in the UK across three websites over a one-month period. The study also aimed to determine the volume and proportion of ivory from different ivory-bearing species that can be identified from the images.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Data collection

Barnebys (a popular auctioneer and antique dealer search engine), eBay UK (a general online marketplace) and Antiques Atlas (a specialist online marketplace) were chosen as study websites as recent reports have shown that these websites frequently advertise ivory items (eg, Lau et al, 2016; Alfino and Roberts, 2020; Venturini and Roberts, 2020; Parry, 2021).

Searches were conducted using the words ‘ivory’, ‘tusk’, ‘teeth’, ‘scrimshaw’ (an engraved item), ‘okimono’ (a decorative sculpture), ‘netsuke’, ‘faux ivory’, ‘ivorine’ and ‘bone’. The same nine keywords were searched every day on each website. These nine keywords were chosen on the basis that previous studies have shown they produce results for ivory (Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro, 2016; Baker et al, 2020; Venturini and Roberts, 2020) and a preliminary search of each website prior to the start of the investigation produced results relating to all relevant ivory-bearing species.

For Barnebys, the results were refined to the country of ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’. For the purpose of this analysis, the Channel Islands were included in the database as an auction house in Guernsey appeared under this search result. For eBay, the search results were refined to the categories ‘Antiques’ and ‘Collectables’ with the item location set to ‘UK only’. This meant there were two separate searches each day on eBay for each of the nine keywords (totalling 18 unique daily searches). For Antiques Atlas, instead of searching ‘ivory’, the ‘Ivory Antiques’ search was selected and then ordered by ‘date added’.

All keywords were searched every morning at 9:00am (±30 minutes) from 8 November to 8 December 2021 inclusive, and item details for every relevant listing not already on the database was recorded. For each listing, the following information was recorded: date searched, website, keyword searched, product title, seller, seller location, product type, whether the majority of the item was made from ivory, material description, whether the ivory description was overt or covert, ivory-bearing species and the current/estimated price. When an estimated price range was given, the lower figure of the range was recorded. Only eBay provided a date for when each item was uploaded, so this was also recorded for eBay items. The search date was used to estimate the average number of listings per day for Barnebys and Antiques Atlas, and the upload dates were used to calculate the average number of new eBay listings per day.

The products were split into the same four commodity types used by Lau et al (2016), which were jewellery, figures, household goods and personal items. If there was more than one item in the listing, the most numerous category was assigned. If there was the same number present for two or more categories, then the category was assigned based on the estimated cumulative ivory volume of the items. For the purpose of these groupings, all ornamental items were counted as ‘figures’, except for miniature paintings which were allocated as personal items, as per Lau et al’s (2016) study.

If no material related to the ivory element of the product was selected in the item specifics, then the material described in the title or description was recorded. An item was counted as an ‘overt listing’ if the seller described the item as ivory (eg, either directly or indirectly, such as ‘hippo tusk’) and this was confirmed by the images. If a listing failed to provide a description of the material or if it described the ivory as a different material, such as bone, it was counted as a ‘covert listing’. If an item was made from more than one material, but the seller only described the non-ivory material, this was also counted as a covertly described item.

2.2. Visual identification of material

Any listing which may have included ivory from the image(s) and description was investigated, but only items which could be reasonably determined as ivory were recorded. This included items with small amounts of ivory, such as inlaid furniture and teapots with ivory insulators. Listings which included the keyword but where the item was clearly not made from ivory (eg, ivory-coloured carpets) were discounted. The benefit of the doubt was always given to sellers, ie, items were not recorded unless they met the criteria described in the categories below. Duplicate listings were identified and removed.

The categories used by Venturini and Roberts (2020) have been adapted for this investigation. Identified covert ivory listings were assigned to one of four categories which indicated the degree of uncertainty in identifying the material from the images:

Category 1 (C1): Obvious ivory – Animal-identifying features clearly visible in multiple sections, or seller admits it is ivory on their own website or elsewhere in the description.

Category 2 (C2): Highly likely ivory – Animal-identifying features clearly visible in single section and the morphology indicates the ivory originates from this animal.

Category 3 (C3): Likely ivory – Animal-identifying features are not clearly visible, only faintly discernible. Elements such as the colour, texture, price, description and style also suggest it is ivory.

Category 4 (C4): Suspected ivory – Image angles and quality means animal-identifying features not visible, but the colour, texture, price, description, style and brand history (if applicable) suggest it is ivory.

2.3. Visual identification of species of origin

In addition to elephants, identification of the likely source of ivory items was limited to species in the scope of DEFRA’s call for evidence (DEFRA, 2019), namely common hippopotamus, orca, narwhal, sperm whale, walrus, common warthog, desert warthog and mammoth. Listings which included teeth from other mammals were noted but not included in this analysis.

The 4th edition of the Identification Guide for Ivory and Ivory Substitutes (Baker et al, 2020) was the main source used to identify ivory-bearing species. Images present in listings were visually inspected to determine what species the ivory was likely to have been derived from. Items with Schreger lines were presumed to be elephant, unless it could be clearly identified from the angles or evidence of fossilisation that it was likely to be mammoth. The species was allocated as unknown if the listing did not indicate the ivory-bearing species and the species could not be identified with confidence from the image(s).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Initial descriptive statistics were conducted to determine the number of ivory items which belong to each value within the variables. A two-sample t-test assuming equal variances was conducted to identify any significant difference in the value of elephant and non-elephant ivory. A one-way ANOVA analysis was used to determine whether the product type determined the value of the ivory. All statistical analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Volume

From 8 November to 8 December 2021, there were 1,832 identified ivory listings. This included 798 figures, 583 household goods, 396 personal items and 55 jewellery items. A total of 730 listings were identified on the first day. Of all listings, 77.1% (n=1,412) contained an item primarily made from ivory, with the remainder (n = 420, 22.9%) containing items consisting of less than 50% ivory by volume.

Barnebys had a total of 1,399 ivory listings (845 of which were new listings added after the first day of study), eBay had 331 listings (248 new listings) and Antiques Atlas had 102 listings (nine new listings). On average, Barnebys had 28 new listings per day, eBay had eight new listings per day and Antiques Atlas had less than one upload per day. At least one new ivory item listing was found on eBay and Barnebys each day. The three highest daily number of uploads for Barnebys (143, 95 and 90) were all added to the database on a Monday morning.

There were 414 individual sellers (91 auctioneers and 323 private dealers). Of these, 374 were based in England, 23 in Scotland, 13 in Wales, two in Northern Ireland, one in the Channel Islands and the country for one seller was unknown.

Thirty-five entries were omitted as, although Barnebys identified their location as London, 29 were from an auction in the Netherlands, three were from an auction in Ireland and three were from an auction in Hong Kong.

3.2. Value

The total listed value of the listings for this period was £1,169,356.18. The average price was £659.54 and the median price was £100. There was no significant difference between the value of elephant ivory and non-elephant ivory (p = > 0.05).

There was a significant difference between the values of the different item types (p = 0.0158). Household goods were, on average, the most valuable (mean = £1,491), followed by personal items (mean = £725), jewellery (mean = £403) and then figures (mean = £386). Only listings from Barnebys were used, as the inclusion of entries from eBay would have skewed the data due to many listings automatically having a starting bid price of £0.99.

3.3. Species

Individually listed ivory items included 491 elephant, 48 walrus, 26 sperm whale, 15 hippopotamus, 12 warthog, eight mammoth and six narwhal.

There were three occasions where ivory from multiple species could be identified in a single listing: one had one walrus ivory item, two sperm whale teeth and one orca tooth; the second included one walrus ivory item and two sperm whale teeth; and the third had one walrus ivory item and two elephant ivory items. In these instances, for the purpose of the analysis, these listings were allocated to the species from which the most items were identified.

Of the 1,832 listings, the ivory-bearing animal species for 1226 (66.9%) could not be confidently identified. Of the remaining discernible 606 items, 81% were from elephants, with 19% from non-elephant species (Figure 1).

Sperm

Species).

As only the non-elephant species within DEFRA’s call for evidence were analysed, 38 listings containing other mammal teeth were omitted. This included 31 listings containing boar tusk, four containing deer teeth, two containing fox teeth and one containing baboon teeth.

3.4. Overt and covert ivory items

Of the 1,832 listings, 1,555 were overt (84.9%) and 277 were covert (15.1%) (Table 1). The 13 covert Barnebys listings were recorded as covert since they failed to provide any description of the ivory material. The one Antiques Atlas covert listing identified the material as ‘bone’ (despite describing it as a whale’s tooth in the title).

Only 1.0% and 0.9% of listings were identified as covert for Antiques Atlas and Barnebys respectively, but 79.5% of ivory listings on eBay were covert (Figure 2).

Of the 277 identified covert listings, 27.8% (n = 77) were considered ‘obvious’ or ‘highly likely’ to contain ivory (C1 and C2). The remaining 72.2% (n = 200) were identified as ‘likely’ or ‘suspected’ ivory (C3 and C4).

The largest proportion of covert items listed were described as bone (45.8%, n = 127), including ‘bovine bone’, ‘cow bone’ and ‘ox bone’. For 33.9% (n = 94) of covert listings, a description of the material was not provided. The next most frequent category was artificial substitutes (13.0%, n = 36), comprising of ‘ivorine’ (an artificial product resembling ivory), ‘Bakelite’, ‘resin’, ‘acrylic’ and ‘celluloid/simulated ivory’. For 2.5% (n = 7), the material was described as two contradicting materials, such as ‘horn/bone’ and ‘ivorine/bone’ and a further 2.5% (n = 7) of sellers identified another material such as ‘porcelain’ and ‘tagua nut’. Six vendors (2.2%) said the material was made from antlers.

No description

Two contradicting materials

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Value of the online ivory market

Over the 31-day period, 1,832 ivory listings collectively worth over one million pounds were identified. These figures are likely to underestimate the value as eBay items were often recorded when they had just been listed with a low starting bid and the lower estimates from the auctioneers were recorded.

The results showed that 84.2% of the 1,128 items being offered for sale through Barnebys with a known value had a guide price of under £500, whereas Lau et al (2016) found that only 42% of the 420 items on Barnebys had a guide price under £500. This could mean that either auction houses are pricing ivory items at a lower price, or a higher proportion of lower value items are coming to market. However, this difference is more likely explained by Lau et al (2016) recording the uppermost estimate in a price range instead of the lower price, as in the current study. This is supported by Two Million Tusks (2017) finding that 91% of ivory pieces sold at auction for £400 or less shortly after Lau et al (2016)’s study.

The range of prices was higher in the current study. Lau et al (2016) found that the item with the highest guide price was a table cabinet made from a mix of materials being auctioned with a guide price of £20,000–£40,000. The current study found eight items with a guide price exceeding £20,000, five of which exceeded £40,000, the highest being a sword with an ivory grip being advertised by Wick Antiques at a fixed price of £125,000.

4.2. Volume of the online ivory market

Over the 31-day period, 331 listings were identified on eBay, 263 of which were covert. In comparison, during a two-week period in 2011, IFAW (2012) identified 39 listings on eBay UK containing ivory and Alfino and Roberts (2020) found 84 ivory listings on the same website from 18 January to 5 February 2017. Taking into account the varying length of the investigations, the current study found significantly more ivory items on eBay than the previous investigations. Although this could demonstrate an increase in the amount of ivory being sold online in the UK, these differing results may also be explained by the different keywords and search refinements used.

For this study, the word ‘ivory’ was always searched first, with unique results from other keyword searches supplementing these results. Of the 331 eBay listings, 251 (76%) were only found by searching words other than ‘ivory’, such as ‘netsuke’ and ‘bone’. These numbers are still under-representative as more results would have been produced if the searches were not confined to ‘Antiques’ and ‘Collectables’, as it is likely that sellers list ivory under other categories such as ‘jewellery’. Whilst eBay has blocked a number of listings and is attempting to combat the problem (Walker, 2021), the findings suggest they are still failing to effectively tackle the issue.

Lau et al (2016) found 56% of ivory items available at physical markets were figures, 26.8% were household goods, 9.5% were jewellery and the remaining 7.7% were personal items. In comparison, the current study found that items consisted of 43.6% figures, 31.8% household good, 21.6% personal items and 3.0% jewellery. Although ornaments remain the most common type of item available to buy, it appears that a larger proportion of household goods and personal items are available online. These item types, on average, are significantly more valuable than figures and jewellery.

During a survey in April 2016, Lau et al (2016) identified 695 ivory items across both Barnebys and The Saleroom (another auction search service). In the space of a month the current study found approximately double the number of ivory items (n = 1,399) on Barnebys alone. Although Lau et al (2016) excluded items which stated that they were made from non-elephant ivory and did not collect information over a month, there is no indication that the introduction of the Ivory Act in 2018 has deterred any auction houses from selling ivory.

The day of the week chosen to sample data may impact the number of ivory items found in investigations, as a high number of listings were identified on Monday mornings. This suggests that either Sunday daytime or early Monday morning may be the most popular time for auctioneers to advertise their lots.

4.3. Enforcement of regulations

The figures include items which contain any amount of ivory, meaning that trade in some of these items may still be permitted under exemptions once the Ivory Act is implemented. However, this is likely to be a small percentage, as 22.9% of items for sale were deemed to not have ivory as the primary material (less than 50% of ivory) only a proportion of which would contain less than 10% ivory, in which case they may be exempt under the Act (DEFRA, 2021). Musical instruments containing less than 20% ivory by volume and pre-1918 portrait miniatures with a surface area of no more than 320cm2 may also be exempt under the Act. Some items offered for sale might also fall into the exemption under the Act for pre-1918 items of outstandingly high artistic, cultural or historical value (DEFRA, 2021).

These items did not form a significant part of the data as only 106 listings were ‘paintings’ and nine were ‘musical instruments’, some of which may already be exempt for having less than 10% ivory by volume. Not all of these items would be exempt, but assuming they all did meet the type, ivory volume, size and date exemption requirements, this would form 6.3% of all listings. Items which were either musical instruments, paintings or deemed to be less than 50% ivory, make up 498 of the listings, meaning that the maximum possible percentage of listings that would qualify for exemptions is 27.1%. However, as discussed, the actual number of exempt listings is likely to be significantly lower. This leads us to conclude that delays in implementing the Act have allowed continued domestic and international trade in large amounts of ivory which will be illegal to trade once the Act is implemented.

It is likely that some of the ivory would be illegal to sell even under current regulations, as recently-poached ivory continues to be sold across Europe (Avaaz, 2018). The current study supports the view that the banning of post-1947 ivory has not been effective in preventing more recently poached ivory from entering the UK market. There was one fly swish on eBay which was likely to be ivory, despite claiming to be bone (faint Schreger lines, no evidence of the pitting which is seen on bone), and it was inscribed ‘A gift from the people of Tanzania 1967’. Therefore, not only have delays in implementing the Act allowed large quantities of items to be traded but have also continued to enable the trade of illegal ivory.

4.4. Finding ivory items online

The results were limited by the search refinements used. Antiques Atlas had few daily uploads, with an average of one upload every three to four days, but not every item containing ivory would have been put under the ‘Ivory Antiques’ category. A general search for the word ‘ivory’, as with the other two websites, would have produced more results.

Searches for ‘faux ivory’ did not produce unique results on any of the websites, despite previously being identified as a codename for ivory (IFAW, 2012; Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro, 2016) and no listing on the database explicitly used this term to describe the material. This was the only keyword that was not responsible for finding any of the listings on the database. This may show that the use of code words changes over time in order to evade detection.

It may be that the word ‘ivory’ is avoided by sellers altogether, as these listings could be automatically flagged to monitors. It was noted that some listings which were deemed to not be made from ivory still used the spelling ‘iv0ry’ (using the digit zero) when describing the item’s colour or the vegetable ivory material. This presents further challenges in efforts to find ivory listings.

Searching for ‘teeth’ antiques on eBay produced eight teething rings and sticks made of ivory that were covertly listed. Although the purpose was to find items made from teeth, this suggests that covert ivory may be more often found by searching for items that are often made with ivory, such as netsukes.

4.5.Identifyingcovertivory

Although eBay was only responsible for 18.1% of all identified ivory listings, the majority of its ivory items were covert (Figure 2). As a recent study also found (Venturini and Roberts, 2020), ‘bone’ was the most popular material description used for ivory items on eBay (Figure 3). The number of ivory items being sold as bone is likely to be even higher because some ‘bone’ items could have potentially been made from ivory, but this could not be verified from viewing the images provided, either because of the image quality or the way it was carved (such as with “bone” inlaid boxes and knife and fork handles).

Approximately 20% of covert ivory sellers on eBay encouraged the careful examination of or the zooming in on all images, without referencing a particular feature or damaged part of the item. This indication of covert ivory has been previously identified by Baker et al (2020).

Other tactics included photographing the item on scales to demonstrate its weight, photographing the item with light shining through it and describing the material (eg ‘Carved from a hard white/cream material’ and ‘Taps hard like stone but looks a bit varnishy. I have applied heat and it doesn’t melt. Weighs 51 gm’.) IFAW (2012) also found that in 2011, sellers on eBay would imply the material was ivory without explicitly stating that it was, for example by referencing items as ‘being cold to the touch’. This study demonstrates that, a decade later, eBay sellers are still able to sell ivory using this same tactic.

It may be that some sellers were genuinely unable to recognise the items as elephant ivory. However, it can be assumed that the majority of sellers were being purposely deceptive to avoid their listing being removed, as many eBay sellers were linked to a professional antiques shop. There were multiple occasions where the seller described their item as being made from a different material, but their personal website confirmed the item was made from ivory. For example, one seller listed three canes as being made from ivorine, but their own antique cane website described the same three items as being made from ivory. Another example was a Thomas Tuttell sundial priced at £3,750, with the plate being described as bone. The same item on their website had the exact same description except the plate was described as ivory.

Also, although the material was described in the item specifics as being something else, some listings admitted that the item was made from ivory in the description. One wrote ‘Madeofthefinestqualitymaterials,German silver(anickelalloy)theotherwhichIcannotnamehere,isbestleftontheanimalswithtrunkstowhichit belongs,butasitwasmadeoverahundredyearsagocanbeenjoyedforit[sic]wonderfulsilkysmoothtexture’ One eBay seller selected the primary material as ‘Mixed Material’ and wrote in the description ‘Pleasebe understandingthereisnodisrespectofanimalasisover100yearssoisantiques[sic]–Guaranteeelephant teeth’ Two listings were even less subtle, as they selected the primary material as ‘bone’ and ‘acrylic’ but then described the items as ivory in the description. Many eBay listings contradicted themselves, for example, by saying the material is Bakelite in the description, but selecting the material as bone in the item specifics. Some also selected the material as being different materials eg ‘Ivorine/Bone’, ‘Plastic/Bone’ and ‘Horn/Bone’.

Two covert eBay listings put in their description ‘ImportantnotetoeBayteam:Thisitemdoesnotcontainany animalorpartofananimalofaspecieslistedinSchedule5oftheWildlifeandCountrysideAct,ortheSchedules totheWildlifeActs1976-2000.Nordoesthisitemcontainanyanimalorpartofananimalofaspecieslistedon AnnexAoftheEUWildlifeTradeRegulations.ThisitemhasbeencheckedagainsttheAnnexAorBlistoftheEU WildlifeTradeRegulationsandhasbeenconfirmedthatitisabletobeexportedfromtheEUwithoutapermit. Itemiscraftedfrombonederivingfromabostaurus(cattle).’ One of these listings contradicted themselves by describing the ivory netsuke as bone in the description but selected ‘ivorine’ as the primary material.

4.6. Identifying the ivory-bearing species

The findings complement those of recent studies as elephant ivory was the most common species identified (Yeo, McCrea and Roberts, 2017; Parry, 2021). However, numbers of items made from elephant ivory may be much higher because it is the easiest ivory material to identify from online images as Schreger lines are visible from more angles and are more prominent than other markings. There were five listings where the species could not be identified, but the material was described as ‘marine ivory’, suggesting it was made from either hippopotamus, whale, orca or walrus ivory (IFAW, 2004). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that a portion of the listings from an unknown species is ivory from non-elephant sources. The biggest limitation of the study was the lack of clear images from different angles, preventing confident identification of ivory or the ivory species.

Image 2 An example of an overt ivory listing on Barnebys. The poor quality of the image, even when viewed in full on the auctioneer’s website, meant that the species of origin could not be determined.

After the data collection and analysis period, we were made aware that 19 listings which featured in our database were physically inspected by an expert. While the items were described as ‘ivory’ and the species from which they were derived were not disclosed, the expert identified them as being derived from elephant, sperm whale, walrus and hippopotamus. Although the current study determined that nine of the listings featured either elephant or walrus ivory, the species for the remaining 10 were unknown. This supports the assumption that a significant portion of the ivory items from an unknown species are derived from non-elephant sources.

Nearly one fifth of identifiable items were determined to be from non-elephant sources (Figure 1). Although DEFRA’s call for evidence suggested that the UK is not of major importance in the trade or market of nonelephant ivory (DEFRA, 2019), the findings of this study challenge this. One investigation found a total of 899 hippopotamus, mammoth, narwhal, whale, walrus and warthog ivory items were sold by auction houses from 2013 to 2019, with an additional 20 having a mixture of species and a further 630 not being fully identified but labelled ‘marine’ (DEFRA, 2019). The current study suggests that this is a huge underestimation of the scale of the non-elephant ivory market in the UK.

In one month, 120 ivory listings were confidently determined to be from non-elephant species (including five listings that were not fully identified but labelled ‘marine ivory’) using online images. Scaled up, this would equate to 8,640 non-elephant ivory items in roughly six years. Unless the methodology for the previous investigation severely limited the number of ivory items that could be identified, the most plausible explanation for the disparity is that the demand for non-elephant ivory has significantly increased since 2019. It cannot be ruled out that the proposal to ban elephant ivory has already shifted demand towards items made from non-elephant ivory-bearing species, especially as auctioneers have reported an increasing interest in hippopotamus ivory as an alternative to elephant ivory (Horton, 2019).

Although hunting for ivory has not yet been identified as the main conservation concern for all non-elephant ivory-bearing species (IFAW, 2020), banning the sale of ivory from these species should still be considered as a conservation measure and it would also help ensure rigorous and effective enforcement of the legislation designed to protect elephants.

No animal-identifying features were visible in over two thirds of all ivory listings, demonstrating the difficulty in distinguishing the ivory species from online images. There were many items that contained more than 10% ivory, but the style of the item, coupled with the lack of clear images focusing on the ivory components, meant that the animal-identifying features were not visible. Even if the images were viewed by experts, the quality and lack of angles make confident differentiation impossible for some listings.

If only elephants are protected by the Ivory Act 2018, then it is likely that sellers will continue to sell elephant ivory under the guise of it being ivory from a different species that remains legal to trade. Even if Schreger lines are visible in the images, sellers may claim that the item is made from mammoth. The trade in alternative legal ivory, such as mammoth ivory, has the potential to perpetuate demand for elephant ivory (Wildlife Justice Commission, 2021a).

There are also concerns that the legal trade of non-elephant ivory could put strains on the already decreasing populations of other ivory-bearing species (Andersson and Gibson, 2017; BBC, 2021; Moneron and Drinkwater, 2021). Therefore, a precautionary approach involving banning the trade in ivory from all relevant species is important to ensure the protection of both elephant and non-elephant species.

The non-elephant species discussed in this report have already been identified as being at risk of being poached for their ivory, but it is unlikely that all at-risk species can be predicted prior to the enforcement of the Act. Although other ivory-bearing species may provide a more obvious alternative to elephant ivory, other animals may still be at risk of exploitation. For example, helmeted hornbills (Rhinoplax vigil) are being increasingly targeted by hunters as their casque is used as an ivory alternative (BirdLife International, 2020; Ouitavon et al, 2021). Also, it has been recently reported that giant clams (Tridacna species) are being overexploited in response to China’s elephant ivory ban, which is having a devastating impact on their marine habitat (Wildlife Justice Commission, 2021b). Governments need to identify and respond to reports of other species being exploited to provide alternatives to elephant ivory.

4.7. Conclusion

New advertisements for ivory items are being uploaded on online UK trading sites every day, with sellers continuing to find ways to evade detection on platforms where selling ivory products is prohibited. The delays in implementing the Act have meant that thousands of ivory items have continued to be sold, perpetuating the demand for ivory, and further endangering elephant populations.

Identifying ivory products from online listings can be difficult, but determining the ivory-bearing species is particularly challenging due to the limited number of images, poor image quality, inability to view the item from certain angles, and limited or deceitful text descriptions. The Act currently only prohibits trade in ivory from the tusk or tooth of an elephant (DEFRA, 2021). If the regulations are not amended to include other species, then there are two likely outcomes: Elephant ivory will continue to be sold under the guise of it coming from other species, especially mammoth if Schreger lines are visible; and non-elephant species will be more at risk from exploitation due to a shift in demand away from elephant ivory to other, legal alternatives.

Considering the delays that the Act has already faced and the increase in the popularity and trade of nonelephant ivory observed, a preventative approach rather than reactionary changes is of the upmost importance to the conservation of elephant and non-elephant ivory-bearing species and effective wildlife law-enforcement.

REFERENCES

Alfino, S. and Roberts, D. (2020). Code word usage in the online ivory trade across four European Union member states. Oryx, 54 (4), 494-498.

Andersson, A. and Gibson, L. (2017). Missing teeth: Discordances in the trade of hippo ivory between Africa and Hong Kong. African Journal of Ecology, 56.

Antiques Atlas (2022). Welcome to Antiques Atlas. Online at: www.antiques-atlas.com, accessed 19 January 2022.

Aryal, A., Morley, C. and McLean, I. (2018). Conserving elephants depend on a total ban of ivory trade globally. Biodiversity and Conservation, 27 (10), 2767-2775.

Avaaz (2018). Radiocarbon testing illegal ivory in Europe’s domestic antique trade. Online at: https://s3.amazonaws. com/avaazimages.avaaz.org/AVAAZ_EUROPES_DEADLY_IVORY_TRADE.pdf, accessed 19 January 2022.

Baker, B., Jacobs, R., Mann, M., Espinoza, E. and Grein, G. (2020). Identification Guide for Ivory and Ivory Substitutes. Online at: https://files.worldwildlife.org/wwfcmsprod/files/Publication/file/6smyb8xhvw_R8_IvoryGuide_07162020_high_ res.pdf?_ga=2.187242152.1437582083.1635174461-465521041.1635174461, accessed 26 October 2021.

Bandow, D. (2013). When You Ban the Sale Of Ivory, You Ban Elephants. Forbes. Online at: https://www.forbes.com/ sites/dougbandow/2013/01/21/when-you-ban-the-sale-of-ivory-you-ban-elephants/, accessed 20 January 2022.

Barnebys, n.d.Your search for art, design, antiques, and collectables starts here. Barnebys. Online at: https://www. barnebys.co.uk, accessed 25 January 2022.

BBC (2021). UK looks to extend ivory ban to hippos and other animals. BBC News. Online at: https://www.bbc. co.uk/news/uk-politics-57867935#:~:text=Hippos%2C%20walruses%20and%20whales%20could,the%20only%20 animals%20at%20risk, accessed 24 January 2022.

BirdLife International (2020). Rhinoplax vigil. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22682464A184587039. Online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22682464A184587039.en, accessed 1 February 2022.

Chase, M., Schlossberg, S., Griffin, C., Bouché, P., Djene, S., Elkan, P., Ferreira, S., Grossman, F., Kohi, E., Landen, K., Omondi, P., Peltier, A., Selier, S. and Sutcliffe, R. (2016). Continent-wide survey reveals massive decline in African savannah elephants. PeerJ, 4, p.e2354.

CITES (2019). Trade in elephant specimens. In: Conf. 10.10 (Rev. CoP18). Online at: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/ document/E-Res-10-10-R18.pdf, accessed 31 January 2022.

CITES (2020). Elephant Trade Information System (ETIS) Report: Overview of seizure data and progress on requests from the 69th and 70th meetings of the Standing Committee (SC69 andSC70). Geneva. Online at: https://cites.org/ sites/default/files/MIKE/ETIS/E-CITES%20Secretariat_TRAFFIC_ETIS%20report_Sept2020_final_MESubgroup.pdf accessed 7 January 2022.

Cox, C. (2021). The Elephant in the Courtroom: An Analysis of the United Kingdom’s Ivory Act 2018, Its Path to Enactment, and Its Potential Impact on the Illegal Trade in Ivory. Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy, 24 (2), 105-130.

de Jong, Y.A., Butynski, T.M. and d’Huart, J.P. (2016). Phacochoerus aethiopicus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41767A99376685. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41767A44140316.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

de Jong, Y.A., Cumming, D., d’Huart, J. and Butynski, T. (2016). Phacochoerus africanus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41768A109669842. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS. T41768A44140445.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

DEFRA (2018). Ivory Bill: Factsheet – Illegal ivory seizures.

DEFRA (2019). Call for evidence: Non-elephant ivory trade. Online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933922/non-elephant-ivory-trade-summary-of-responses. pdf, accessed 27 October 2021.

DEFRA (2021). Enforcement of the Ivory Act 2018 and guidance on the use of civil sanctions.

Ganesan, R., Gupta, A., Tsiko, S., Smallhorne, M. and Vorster, I. (2016). Should ivory trade be legalised? Down to Earth. Online at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/wildlife-biodiversity/should-ivory-trade-be-legalised—53564, accessed 19 January 2022.

Gobush, K.S., Edwards, C.T.T, Maisels, F., Wittemyer, G., Balfour, D. and Taylor, R.D. (2021). Loxodonta cyclotis (errata version published in 2021). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T181007989A204404464. Online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021- 1.RLTS.T181007989A204404464.en, accessed 7 January 2022.

Gobush, K.S., Edwards, C.T.T, Balfour, D., Wittemyer, G., Maisels, F. and Taylor, R.D. (2021). Loxodonta africana (amended version of 2021 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T181008073A204401095. Online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T181008073A204401095.en, accessed 7 January 2022.

Harris, L., Gore, M. and Mills, M. (2019). Compliance with ivory trade regulations in the United Kingdom among traders. Conservation Biology, 33 (4), 906-916.

Harrison, J., Roberts, D. and Hernandez-Castro, J. (2016). Assessing the extent and nature of wildlife trade on the dark web. Conservation Biology, 30, 900–904.

Harvey, R. (2016). Risks and Fallacies Associated with Promoting a Legalised Trade in Ivory. Politikon, 43 (2), 215-229.

Hernandez-Castro, J. and Roberts, D. (2015). Automatic detection of potentially illegal online sales of elephant ivory via data mining. Peer J Computer Science, 1, p.e10.

Horton, H. (2019). Ivory ban is killing hippos as poachers take advantage of loophole in new law. The Telegraph. Online at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/07/06/ivory-ban-killing-hippos-poachers-take-advantage-loophole-new/, accessed 24 January 2022.

Hsiang, S. and Sekar, N. (2016). Does Legalization Reduce Black Market Activity? Evidence from a Global Ivory Experiment and Elephant Poaching Data. NBER.

IFAW (2004). Elephants on the high street: An investigation into ivory trade in the UK. Online at: https://d1jyxxz9imt9yb. cloudfront.net/resource/679/attachment/original/Elephants_on_the_high_street_an_investigation_into_ivory_trade_in_ the_UK_-_2004.pdf, accessed 10 January 2022.

IFAW (2012). Killing with Keystrokes 2.0: ifaw’s investigation into the European online ivory trade. Online at: https:// d1jyxxz9imt9yb.cloudfront.net/resource/694/attachment/original/FINAL_Killing_with_Keystrokes_2.0_report_2011.pdf, accessed 26 October 2021.

IFAW (2020). Adding hippopotamus to the Ivory Act. Online at: https://d1jyxxz9imt9yb.cloudfront.net/resource/332/ attachment/original/adding-hippopotamus-ivory-act-web.pdf, accessed 7 January 2022.

Kaile, J. (2020). Elephant tusks seizure shows importance of UK wildlife crime police. IFAW. Online at: https://www.ifaw. org/uk/journal/elephant-tusks-seizure-shows-importance-uk-wildlife-crime-police, accessed 19 January 2022.

Lau, W., Crook, V., Musing, L., Guan, J. and Xu, L. (2016). A rapid survey of UK ivory markets. TRAFFIC, Cambridge, UK. Online at: https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/2385/uk-ivory-markets.pdf, accessed 26 October 2021.

Lewison, R. and Pluháček, J. (2017). Hippopotamus amphibius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T10103A18567364. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T10103A18567364.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

Lowry, L. (2016). Odobenus rosmarus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T15106A45228501. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T15106A45228501.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

Lowry, L., Laidre, K. and Reeves, R. (2017). Monodonmonoceros. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T13704A50367651. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T13704A50367651.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

Lusseau, D. and Lee, P. (2016). Can We Sustainably Harvest Ivory? CurrentBiology, 26 (21), 2951-2956.

Menon, V. and Tiwari, S. (2019). Population status of Asian elephants Elephasmaximus and key threats. International ZooYearbook, 53 (1).

Moneron, S. and Drinkwater, E. (2021). The Often Overlooked Ivory Trade. TRAFFIC. Online at: https://www.traffic.org/ site/assets/files/14405/the_often_overlooked_ivory_trade.pdf, accessed 27 October 2021.

Nishino, R. and Kitade, T. (2020). Teetering on the brink: Japan’s online ivory trade. TRAFFIC, Japan Office, Tokyo, Japan.

Ouitavon, K., McEwing, R., Penchart, K., Sri-aksorn, K. and Chimchome, V. (2021). DNA Recovery and Analysis from Helmeted Hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) Casques and its Potential Application in Wildlife Law Enforcement. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Parry, T. (2021). EXCLUSIVE: Sickening online ivory trade still going on in UK despite three-year-old law TheMirror Online at: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/sickening-online-ivory-trade-still-25111233, accessed 26 October 2021.

Peez, A. and Zimmermann, L. (2021). Contestation and norm change in whale and elephant conservation: Non-use or sustainable use? CooperationandConflict.

Reeves, R., Pitman, R.L. and Ford, J.K.B. (2017). Orcinusorca. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T15421A50368125. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15421A50368125.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

Sehmi, H. (2019). Closing legal markets for illicit ivory will save Africa’s elephants. AfricanWildlifeFoundation. Online at: http://Closing legal markets for illicit ivory will save Africa’s elephants, accessed 19 January 2022.

Sosnowski, M., Knowles, T., Takahashi, T. and Rooney, N. (2019). Global ivory market prices since the 1989 CITES ban. BiologicalConservation, 237, 392-399.

Taylor, B.L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S.M., Ford, J., Mead, J.G., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Wade, P. and Pitman, R.L. (2019). Physetermacrocephalus (amended version of 2008 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T41755A160983555. Online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41755A160983555.en, accessed 18 January 2022.

Two Million Tusks (2017). Ivory:TheGreyAreas-AstudyofUKauctionhouseivorysales–The missingevidence. Online at: https://282db987-cb0e-4de2-9062-7e281e52d6bc.filesusr.com/ugd/ e50900_416fd8e2f74443afbf223dc1a6d3f2ea.pdf?index=true, accessed 12 January 2022.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2014). GuidelinesonMethodsandProceduresforIvorySamplingand LaboratoryAnalysis. Vienna: United Nations. Online at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/Wildlife/Guidelines_Ivory.pdf, accessed 10 January 2022.

Venturini, S. and Roberts, D. (2020). Disguising Elephant Ivory as Other Materials in the Online Trade. Tropical ConservationScience. Online at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082920974604, accessed 26 October 2021.

Walker, S. (2021). Wildlife Trafficking Alliance and eBay Join Forces to Combat Wildlife Trafficking. Associationof ZoosandAquariums. Online at: https://www.aza.org/connect-stories/stories/wta-ebay-to-combat-wildlife-trafficking, accessed 12 January 2022.

Wildlife Justice Commission (2021a). Wildlifetradeone-commercesitesinChina,withafocusonmammothivory: ARapidAssessment. Online at: https://wildlifejustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/WJC_wildlife-trade-on-ecommerce-sites-in-china-with-a-focus-on-mammoth-ivory-Spreads.pdf, accessed 11 January 2022.

Wildlife Justice Commission (2021b). Giant clam shells, ivory, and organised crime: Analysis of a potential new nexus. Online at: https://wildlifejustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Giant-Clam-Shells-Ivory-And-Organised-Crime_APotential-New-Nexus_WJC_spreads.pdf, accessed 25 January 2022.

Williams, C., Tiwari, S.K., Goswami, V.R., de Silva, S., Kumar, A., Baskaran, N., Yoganand, K. and Menon, V. (2020). Elephas maximus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T7140A45818198. Online at: https://dx.doi. org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T7140A45818198.en, accessed 17 January 2022.

Wilson-Spath, A. (2019). The Great Elephant Debate: Legalising ivory trade will be a giant mistake. Conservation Action Trust. Online at: https://conservationaction.co.za/media-articles/the-great-elephant-debate-legalising-ivory-trade-willbe-a-giant-mistake/, accessed 19 January 2022.

WWF (2019). Two years after China bans elephant ivory trade, demand for elephant ivory is down. Online at: https:// www.worldwildlife.org/stories/two-years-after-china-bans-elephant-ivory-trade-demand-for-elephant-ivory-is-down, accessed 18 January 2022.

WWF (2021). Demand for Elephant Ivory in China Drops to Lowest Level Since National Ban. Online at: https://www. worldwildlife.org/press-releases/demand-for-elephant-ivory-in-china-drops-to-lowest-level-since-national-ban, accessed 18 January 2022.

Yeo, L., McCrea, R. and Roberts, D. (2017). A novel application of mark-recapture to examine behaviour associated with the online trade in elephant ivory. Peer J, 5, p.e3048. Online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC5346282/#ref-49, accessed 26 October 2021.