Groeten uit!

A journey about being invited into a community

Groeten uit!

A journey about being invited into a community

Ellis Soepenberg

Master of Urbanism

Academy of Architecture Amsterdam

June 25th 2024

Mentor Martin Probst

Commision members

Ania Sosin

Arjen Oosterman

Additional members

Martin Aarts

Andrew Kitching

For the community of Poelenburg. Thank you for sharing your story.

PREFACE

My interest in post-war neighborhoods in the Netherlands started when I moved back to the Netherlands after living in Canada for 10 years. Since my return, I have had the opportunity to participate in Academy projects in several different post-war neighborhoods in the Netherlands. Even when I had projects in other countries (Belgium, Athens, Georgia, and Azerbaijan), my focus was on creating neighborhoods that also solved social issues and helped the people in those neighborhoods. I always wondered if I could do more than just design buildings.

During my work at the Municipality of The Hague, where I’ve been employed since 2017, I have always worked in either the post-war neighborhood Zuidwest or on projects that benefited social housing neighborhoods like Bezuidenhout West. When I got my first apartment in The Hague, I moved to Moerwijk. Moerwijk is considered one of the problem neighborhoods. I never had any problems there; I loved living next to the big Zuiderpark and going on runs there. My neighbors were extremely nice and would often spoil me with food. Yes, you could hear each other. Yes, the neighbors did warn me not to go to certain streets in the area alone at night, so I didn’t. But I wondered why my colleagues couldn’t see what I saw; the people in Moerwijk weren’t the problem, they had problems.

In 2018, I met my now partner. He lived in the Rivierenbuurt in The Hague and was busy stripping and renovating his own apartment. When I went to his apartment for the first time, I realized I had made plans for

his neighborhood. The plans included more than just stripping; his block could possibly be demolished to provide an entrance to the parking garage for the tallest building that was going to be built in The Hague. His reaction to the news surprised me (‘Give me a big bag of money, and I’ll be gone!’). Since then, I have never been able to meet a resident of one of my projects before I start a plan, when there’s still a blank piece of paper.

But what if we could put people first again, what if we got to know the neighbors? What if we could get the neighbors to tell their story, share the richness of their community, and invite us to be part of their community planning? Through this graduation process, I tried to let the people who so rarely get a voice in our design and planning processes tell their stories. I invite you to become part of my journey of being invited into a community, in this case; Poelenburg, Zaandam.

Groeten uit, The postwar neighborhood. Ellis, 35 (the Netherlands & Canada)

Introduction

Preparation

1. The postwar neighborhood

2. Bridging the Gap

Initiation

3. Do it Together Urbanism

4. Case Study Poelenburg, Zaandam

Consolidation

5. Let’s do it together!

Look at your hand, all fingers are different. It’s just like people. All people are different, some are good, some bad. But they’re all part of the same hand and deserve the same love and attention.

-Maria

68, Portugal

May 3rd 2024

This graduation project will detail my process of developing ‘Do It Together Urbanism’. I created this method to empower the people in a postwar neighborhood.

In Chapter 1, I will outline what a postwar neighborhood is and how it has developed since its inception.

Chapter 2 will describe my journey in learning how to bridge the gap between the social and spatial realms. These are two crucial aspects at play in postwar neighborhoods, both of which must be considered when working with these communities.

Chapter 3 will introduce the Do It Together methodology, presenting its three phases: preparation, initiation, and consolidation. You will also notice that this booklet is structured around these three phases.

Then, I will demonstrate how the method was implemented in the Poelenburg neighborhood in Zaandam. In Chapter 4, I will go through all the steps of the process and present the conclusions I have drawn for both the neighborhood and the method.

INTRODUCTION

I will conclude with a set of steps to guide you in conducting your own ‘Do It Together Urbanism’. My hope is to inspire others to empower people in marginalized neighborhoods by sharing the steps I have taken.

PREPARATION

Spatial realm

There are a total of 68 post-war neighborhoods in the 30 largest municipalities in the Netherlands. These neighborhoods were built between 1945 and 1965 and host a total of 710 thousand people. This is 4% of the total population, half of whom live in the Randstad. Forty-seven percent of the houses in these neighborhoods are social housing, whereas the Dutch average is 30% (CBS, 2017).

These neighborhoods were constructed with the modern ideal of a new way of living to address the high housing shortage after the Second World War. They are characterized by largescale plans in which all functions and locations of the neighborhood were predetermined. In true modernist fashion, functions were separated: stores were placed in clusters, and traffic was disconnected from other functions due to the introduction of the personal car in the 60s (BZK, 2024). The neighborhoods had a clear structure of green spaces and water, which were seen as the spatial framework for the design. Unfortunately, this structure

The postwas neighborhood

did not integrate well with the buildings. Most apartment buildings from this period have a ‘blind’ facade on the ground floor, and the sides of buildings often lack windows. A typical urban design feature of these neighborhoods is the stamp building blocks, characterized by its composition of high (5+ stories) and middlehigh (4-5 stories) buildings in geometrically spacious public spaces. These blocks are then repeated throughout the neighborhood to give it a distinct character. Nowadays, these stamp blocks are viewed as spatially unclear and monotonous (PBL, 2008).

The current assignment for the national government is similar to when these neighborhoods were originally built, but the question has become more complex. New housing needs to be constructed within the existing built environment. Deferred maintenance of housing and public spaces in neglected areas also needs to be addressed. Additionally, the Netherlands needs to densify and become more sustainable for the future (BZK, 2024). The national government has

committed to building 1 million houses by 2040 (BZK, 2022). They have identified postwar neighborhoods as promising locations for densification, with the potential to add a total of 708,000 houses (BZK, 2024). This is based on the idea that the existing public space is not used to its full potential, offering a lot of room for development. The housing stock is in poor condition and mostly owned by social housing companies, allowing for whole blocks to be redeveloped comprehensively (BURA, 2023).

Social realm

Most studies about post-war neighborhoods indicate that there were initially no social problems in these areas. People were excited to live in these neighborhoods, as they offered bigger and more modern housing. There was more space compared to prewar neighborhoods (NICIS Institute, 2014). These neighborhoods had a very stable existence, and the population rarely changed until the early 90s. Other housing options became available in the cities, and combined with the growing economy and the influx of immigrants,

this changed the social composition. Some parts of these neighborhoods received upgrades around the same time, resulting in a decline of affordable and social housing. As a result, people who had no choice, because they were part of the social housing system were concentrated in specific areas or neighborhoods. This led to a mix of newcomers who had no choice about their living situation, elderly residents who had been living in their homes since the beginning and people trapped in their relatively cheap house because of rental protection. These groups had such different lifestyles that they did not mix but lived next to each other in the same neighborhood (Van Beckhoven and Van Kempen, 2005).

The Dutch government decided in 2007 to invest in 40 neighborhoods that had a combination of social, physical, and economic problems. Minister Ella Vogelaar announced these neighborhoods on March 22, 2007, which is why they are now known as ‘Vogelaarwijken’ (VROM, 2007).

The Ministry of Economic Affairs published a report in 2009 showing that the investments towards the social housing companies did not result in less nuisance. The report ‘De Baat op Straat’ stated that there was only a positive impact on livability in these neighborhoods when social corporations sold off their property. The report concluded that people feel more involved in their neighborhood when they own their property (Marlet, G. et al, 2009).

The Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau (SCP) measured the impact of the policy of the Vogelaarwijken in 2011. They concluded that the situation in these neighborhoods had barely changed from 1999 until 2008. They noted

a difference in the social structure of these neighborhoods: the Dutch middle class left, and an influx of non-western immigrants began living in these areas (Steenvoorden, E. et al, 2011).

After these reports, the Dutch government decided to stop the investments in 2014. This led to the continuation of degeneration of these neighborhoods, as none of the major parties committed to investments during this time (Kragten, 2022).

In 2022, a similar approach to the Vogelaarwijken was reintroduced by the Dutch government, this time named ‘Focuswijken’. Twenty neighborhoods were selected to receive a total of 1 billion euros for investment over the next 15 to 20 years. The idea is that these investments would help continue the current programs already present in these neighborhoods, which often have a short duration (Kragten, 2022).

Groeten

uit

The policies in both the social and spatial realms over the past 10-15 years have resulted in communities where major developmental decisions are made by large institutions. Because these neighborhoods are identified as ‘a problem’ through big data, I believe that policymakers have robbed the community of their voice by not giving the community a platform. With my master’s thesis, I am trying to find a method to give communities their collective story back.

It’s great that people come to talk to the neighborhood that want to make the neighborhood a better place. Everyone that comes to talk to us is normally here for the poverty.

-Asim 24, Turkey September 1st 2023

Bridging the Gap

“Looking at the map, I expected these people to live next to a very nice park, where ‘Poelenburg Beach’ is located. I’m trying to walk there now. But what I encounter is first a cycle path, then a green strip and then a road that I cannot cross.

-Ellis Soepenberg September 1st 2023

This chapter will outline the different methods I used to learn how to bridge the gap between the social and spatial realm.

Through my research, I found a significant gap between the social and spatial realms. A lot of money and effort goes into addressing these neighborhoods to address the socioeconomic problems of the people. In the Netherlands, an average of 96% of municipal taxes goes towards the social realm (CBS, 2024). On average, 54% of this amount is allocated to social-cultural services to keep social programs running in the neighborhoods (CBS, 2024). In contrast, only an average of 3% of the municipal budget is spent on improving the spatial realm (CBS, 2024). In these neighborhoods, 15.8% of people of working age receive welfare benefits, compared to the Dutch average of 12% (CBS, 2017). This indicates that more people are dependent on institutions in these neighborhoods.

I believe that improving post-war neighborhoods starts by putting the community first. Through my master’s thesis, I have researched the following:

What if a marginalized community could invite designers to empower their community through design?

Part of empowering people involves bridging the gap between the social and spatial realms. I have learned how to bridge this gap through different methods: desk research, interviews with professionals, and location visits. This research resulted in a method I developed called ‘Do It Together Urbanism’, which I will outline in the next chapter.

SELF-ACTUALIZATION

Desire to become the most that one can be

ESTEEM

Respect, self-esteem, status, recognition, strength, freedom

LOVE AND BELONGING

Friendship, intimacy, family, sense of connection

SAFETY NEEDS

Personal security, employment, resources, health, property

PHYSIOLOGICAL NEEDS

Air, water, food, shelter, sleep. clothing, reproduction

Maslov hierarchy of needs

Desk research

Working with people requires me to understand their needs. I wanted to know what people actually need. In my research, I found two theories that seem unrelated but are highly relevant.

One theory is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which is a pyramid showing the different needs a person has. It states that only when a certain need is satisfied can a person move on to the next tier. Most people in post-war neighborhoods only meet the first or second tier of this pyramid.

CITIZEN CONTROL

Create own plans

DELEGATION

Transfer of businesses

PARTNERSHIP

Joint planning i.e. in project group

CONSULTATION

Formal dialogue, i.e. in workshop form

INFORMING & RECORD

Providing or receiving information through newsletter

Arnstein’s participation ladder

The second theory is the ladder of participation. This theory shows how many people can be reached with a certain way of participating in a neighborhood and how much influence they have on the design. With the new environmental law in the Netherlands, the government expects more community involvement in participation sessions.

Combining these two theories shows a link between a person’s ability to participate in community projects and their ability to meet their own needs. If a person does not meet all their needs, how can we expect them to be an active participant? I want to find a way to empower people through design.

You can’t measure a positive atmosphere, but it’s so important for involvement, learning, and developing skills. You can only achieve this through knowing and trusting one another.

In our profession, we think about life and the future. People in these neighborhoods think about surviving the day.

We gotta stop participating and just start making nice spaces!

These people are at home often, more often than you and I. Their living environment should reflect this and be exciting, inviting, and inspiring.

Professional interviews

I realized that I knew very little about working with people, so I conducted six interviews with different professionals who work with people on a daily basis. I spoke to Nancy Boom, a psychologist; Kasper van der Vlies, a kindergarten teacher; Saskia de Vin, a social worker; Guus Frenaij, a participation officer; Kees Schuyt, a sociologist and Marcus Bouma, an ecologist. Each of these six people taught me a valuable lesson that has played an important role in my research.

I have faith in the youth and their capabilities once they get the chance to show them.

You can do it if you get the chance to do it.

Nancy Kasper Saskia Guus

Kees

Marcus

Location visits

Before narrowing my research down to one location to develop my design, I visited 12 different neighborhoods in the Netherlands. I focused my visits on 8 designated focus areas - early post-war neighborhoods that had previously been Vogelaarwijken and still remain on the Focuswijk list from 2023. Additionally, I visited three Vogelaarwijken that were early post-war neighborhoods and had been deemed ‘fixed’. To understand why these neighborhoods had gained such reputations, I also visited an early post-war neighborhood that was never considered problematic (See appendix).

Before interacting with professionals and learning how to engage with people, I rarely spoke with residents in these neighborhoods. I could visit most of them anonymously and had to make an effort to obtain contact information for people working in the neighborhood. I took pictures and recorded my thoughts while walking through these areas. Looking back, I realized I focused primarily on the physical design aspects—like sidewalk width, building height, and entrances—because I rarely encountered residents to observe how they used these spaces.

I wanted to uncover the ‘hidden network’ of each neighborhood. Despite my thorough desk research, most of the big data I collected couldn’t provide a complete picture of community life. The locations felt empty without the stories of the people living there. I was eager to meet these residents, and I knew just where to start: Zaandam Poelenburg.

Focus areas 2023

Amsterdam Nieuw-West

Arnhem Persikhaaf

Dordrecht Crabbehof & Wielwijk

Den Haag Zuidwest

Rotterdam Zuid

Schiedam Nieuwland

Vlaardingen Westwijk

Zaandam Poelenburg

Postwar fixed Vogelaarwijk 2007

Alkmaar Overdie

Deventer Rivierenwijk

Nijmegen Hatert

Post War neighborhood

Leiden Boshuizen & Fortuijnwijk

Amsterdam Zaandam Alkmaar

Leiden Den Haag

Schiedam

Vlaardingen Rotterdam Dordrecht Nijmegen

Arnhem

Deventer

I can’t believe they put speed trap right here at the entrance of the neighborhood! What are they going to do? We don’t have money to pay the fines. It makes me feel like I’m a criminal that needs to be watch by police all the time. It’s not fair!

- Mohammed 29, Turkey

February 11th, 2024

INITIATION

‘Do It Together Urbanism’ (D.I.T. Urbanism) is a method I have developed throughout this research. It is designed to empower people so they can actively participate in the redevelopment of their neighborhood alongside designers.

The method consists of three phasesPreparation, Initiation, and Consolidation - which form a continuous loop throughout the community engagement process. The aim is to create a feedback loop where each phase informs and refines the work done with the community. While each phase has its own specific goals and methods, the overall objective remains empowering the community.

Preparation

The preparation phase includes desktop research, professional interviews, location visits, and observations. Its goal is to gather data on the current state of the location and identify existing opportunities. The outcome is an overview of spatial possibilities that will serve as the foundation for community empowerment initiatives.

Do It Together Urbanism

As part of the preparation phase, connecting with professionals in the social realm is crucial. This involves gathering insights into the neighborhood’s overall context and engaging with people directly affected. It’s also about drawing inspiration from professionals who work closely with community members on a daily basis.

Initiation

The initiation phase focuses on getting acquainted with the neighbors and collecting their stories. The goal is to gather enough stories from different individuals to form a ‘Story Design’. A Story Design illustrates the opportunities identified by the community, which are often part of the social realm. All parties involved should be able to understand the Story Design, particularly the local residents. They are most important, as they will need to validate their own story. Therefore, it should be presented in a format more accessible than an abstract map.

These stories are gathered by actively being present in the neighborhood. This involves

being present on various days and at different times, rather than just inviting people to speak to you. The key is to establish connections with the neighbors. Whether it’s sharing a meal, playing basketball, or joining PlayStation gaming sessions, the aim is to demonstrate an interest in their lives and to integrate into their community. The objective is to build meaningful relationships, learn people’s names and gestures, and ultimately create a partnership to explore opportunities together.

Consolidation

The Consolidation phase involves creating the ‘Bridge of Empowerment’ and analyzing the collected data. The goal of this phase is to identify common opportunities in both the spatial and social realms. By bridging these two realms, the aim is to empower people to take ownership of the process.

The Bridge of Empowerment connects different sides of the process that are typically disconnected. For example, one side could represent the community, while the other could be an institution. The bridge than serves as a

tool for empowering the community to initiate their own projects. It also serves to integrate social and spatial considerations. For instance, the bridge facilitates participation in tackling spatial issues together with the community, thereby empowering them to take charge of their surroundings.

To determine the most effective form of bridge, the data collected in the first two phases must be analyzed. Commonalities among the stories shared by community members can be quantified into meaningful data. By demonstrating that individuals from diverse age groups, backgrounds, or interests share similar stories, it becomes clear where collective action is most relevant and impactful.

Loop

Upon completing the Consolidation phase, the outcome is not the conclusion of the process but rather the initiation of another iteration of the method. By cycling through the process again, next rounds can potentially proceed more efficiently and with greater specificity. I recommend starting the second round of the process based on a specific Story Design. Multiple Story Designs can be addressed simultaneously within the same neighborhood.

During my graduation project, I completed one cycle of these phases in Poelenburg, Zaandam. This allowed me to test and refine my method. Most importantly, I feel integrated into the community. I have been warmly welcomed by the wonderful neighbors with whom I interacted over the months of conducting my research. The next chapter outlines this journey.

Preparation

Research, analysis, observing, mapping

Initiation

Get to know eachother, being present, talk & listen

Plan forming, create partners, create network Consolidation

I was so blown away by your pure intent, and your open way of speaking and listening to us. I want you to never forget us, that is why I want to give you these butterflies. They have a very special meaning for me.

- Jan 82, the Netherlands March 26th, 2024

I was present in Poelenburg from Early February to mid May of 2024. I visited the neighborhood and neighbors on different days, during different times of the day and even with different modes of transportation. An overview of my visits can be found in the appendix. This chapter will show how D.I.T. Urbanism works, and I will showcase the Story Design that I tried to take to the next phase.

Case study: Poelenburg, Zaandam

Preparation

Historical Analysis

• Verkade, Bruynzeel & Albert Heijn make plans to create neighborhood for employees

The plans for the extension of Zaandam with the neighborhoods Poelenburg and Peldersveld started in 1938 by three big local companies that wanted to create housing for their employees. Bruynzeel, Verkade and Albert Heijn started to make plans, but due to the Second World War these did not get implemented (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

The Second World War created a housing shortage, and the mayor of Zaandam at the time, Joris in ‘t Veld, started participation with the adjacent neighborhoods to design the public space and courtyards of the new neighborhoods. Building of this neighborhood known as ‘designed by Zaankanters, for Zaankanters’ commenced from 1955-1961 (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

• Participation for courtyards in design for Poelenburg

By the time building was completed, not Zaankanters, but ‘immigrants’ moved into the neighborhood. These first wave of immigrants were Dutch people from other provinces like Friesland, Drenthe and Groningen. This resulted in Zaankanters not recognizing this neighborhood as part of Zaandam, because people spoke a different dialect. Due to this, the neighborhood got a bad name and there were many empty houses (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

In 1962 through 1973 the Dutch government invited a lot of temporary workers from Italy and Turkey to work in the factories. The initial thought was that these people would leave after 4-5 years, but this was not the case for the Turkish workers. Because of the changing political climate in Turkey, these workers were allowed to stay in the Netherlands indefinitely. The policy for temporary workers at the time was not to provide them with opportunities to integrate into Dutch society, because they were never meant to stay (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

• Plan for Poelenburg from Gemeente Werken

• Building Poelenburg

• ‘Immigrants’ move into Poelenburg

• Friesland, Groningen & Drenthe

• ‘Immigrants’ move into Poelenburg

Italy & Turkey

1962-1973

• Italians & Turkish families move to Poelenburg

In 1973 the municipality of Zaandam conducted a ‘Onderzoek naar Woon satsifaktie’, a survey among citizens about their living satisfaction. This research showed the municipality that people were not satisfied with the high concentration of immigrants in the neighborhood Poelenburg and that they experienced high level of demolished public space and garbage due to hang youth aged 12-18 (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

Due to these issues and the bad name the neighborhood received, Poelenburg became the Dutch’s first problem neighborhood in 1985. This designation created funds from the municipal government to start the ‘Poelenburg Plus Project’. This provided a financial impulse in education and arts programs and created different mobility options for the neighborhood (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

Just five years later, in 1990, Poelenburg was than named an exemplary project for social renewal (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

1985

1990

Onderzoek naar Woon satisfaktie 2007

• Poelenburg became first ‘Problem neighborhood’ of the Netherlands

• ‘Poelenburg Plus Project’ started; education, arts & mobility options

• Poelenburg named examplary project for social renewal

Due to these issues and the bad name the neighborhood received, Poelenburg became the Dutch’s first problem neighborhood in 1985. This designation created funds from the municipal government to start the ‘Poelenburg Plus Project’. This provided a financial impulse in education and arts programs and created different mobility options for the neighborhood (SteenhuisMeurs, 2022).

Poelenburg becomes Vogelaarwijk

In 2007, Poelenburg was named one of the Vogelaarwijken (VROM, 2007).

2016

• ‘Treitervlogger’ Taunt vlogger

• ‘Tu ig van de riggel’ - Mark Rutte

This resulted in the ‘summer of violence’ in 2018, where the police decided to have a stop-and-search policy implemented in the neighborhood to combat the issues with the hang youth. The municipality announced that they were going to build an extra 5400 houses in the area to start mixing the neighborhood with new people (de Orkaan, 2023).

In 2020 the Coronavirus had a big impact on the neighborhood. Poelenburg was once again in the national news, because people would follow the Turkish news and Covid regulations. This resulted in the municipality taking drastic measures by closing all the playgrounds and public spaces. Dutch neighbors took it upon themselves to start a ‘mouthguard police’ where they would tell on those who would not follow the Dutch Covid regulations (Schenkeveld, W., 2020). Pact Poelenburg also started in 2020. This is a cooperation of thirty big parties that are

On the grounds where the municipality projected the 5400 extra houses, Poelenburg Beach was temporarily opened in 2022. This was a location that the Pact offered to the people in combination with the community center. It provided a location for people to come together in the summer and hang out close to the waterfront. The community center put up activities there. It was a successful location, but Poelenburg Beach was closed in the spring of 2024. The municipality stated that they were going to prepare the grounds for construction, even though the plans of the location have not been finalized yet (Kuyt, 2024).

The impact of the corona crisis becomes clear in the neighborhood. Many people have lost their job or have lost a significant amount of income over the past years. Personal financial issues are bigger than ever (van Egmond, J. et al, 2022).

2018

• Anouncement of +5400 houses in area

• Stop-and-search policy

• The summer of violence

With the introduction of YouTube, people could showcase themselves on the Internet. In 2016 Ismail Ilgun started a set of vlogs called ‘Hoodvlogs’ about life in Poelenburg. The neighborhood got blasted nationally about how the youth would conduct themselves. The prime minister at the time, Mark Rutte, spoke out publicly against these youth and how they should be eradicated (Schildkamp et al, 2016).

2019

• ‘Kansrijk Poelenburg’

• Youth is actively taken to community center

2020

• ‘Mouthguard police”

• Covid news from Turkey

• Municipality closes playgrounds

• Pact Poelenburg

In 2019 the municipality took a different approach to tackling the problems with the youth and started the program ‘Kansrijk Poelenburg’ their aim was to invest in the youth by actively taking them of the street and putting them in social programs in the community centers. This is still an active policy today (Kaulingfreks, F., 2019).

2021

• More parkingspaces

• Gardening for everyone

The first results of Pact Poelenburg are shown in 2021. More parking spaces were created by changing parallel parking to perpendicular parking spaces. They also started a ‘gardening for everyone’ project where they provided community gardens to the neighborhood at the inside of the courtyards. Only one of these gardens is still up and running today (de Orkaan, 2021).

2022

• Escaped serval roams the streets

• Poelenburg Beach is opened

• Impact corona crisis becomes apparent; many people lost icome or lost their jobs

2023

• Kids attacked with fireworks during Sint Maarten

• A’dammer with fake gun arrasted

• ME present during NYE

In 2023 unrest starts again in the neighborhood. On national news it is reported that a boy with a fake gun is arrested in Poelenburg. Children get attacked with fireworks on Sint Maarten (November 11th) (NHNieuws, 2023). The municipality decides to prevent further escalation by putting the riot police on patrol during New Years Eve. This escalated into riots between ME and neighbors (Noordhollands Dagblad, 2024).

During New Years eve I was so afraid that something would happen to me, that I locked myself in my house, turned off all the lights and took my cat into the bedroom where I sat in silence until the people on the street were gone and I was sure that they would not try to demolish my house with fireworks

- Reinier 64, the Netherlands February 29th, 2024

Spatial analysis

Zaandam is located in the Metropolitan Region of Amsterdam in Noord Holland. It sits right on the Zaan, a waterway connected to the IJ, offering an important industrial route to the harbors of Zaandam and Amsterdam. Poelenburg is an extension of Zaandam, situated between the industrial harbor, the A8 highway (Amsterdam-Alkmaar), and the city center. The original design of the neighborhood included many connections between Poelenburg and various locations, such as the nature reserve on the other side of the A8 and the city center. However, only one connection was ultimately made between Poelenburg and the nature reserve. Additionally, there is only one major route in and out of the neighborhood. This is causing the neighborhood to be a bastion within the city.

Poelenburg

Badhoevedorp

Monickendam

Poelenburg

Mobility

Poelenburg is located next to the A8 highway, but it takes approximately 15 minutes by car to reach the highway from within the neighborhood. There is one route to the A8 and one car route to the city center. Recently, the main 50 km/h road that runs past the neighborhood was disconnected from through traffic to reduce speeding. There is one bus stop in the neighborhood, connecting it to Zaandam city center, the hospital, and the central station. The train station is located in Zaandam city center, and it takes 20 minutes to travel from Poelenburg to the station by bus.

NS Station Railway Highway 80km/hr road 50km/hr road

Infrastructure Poelenburg

Slow Traffic

There is a major national bike route that runs through the neighborhood, classified as a separate bike path with red asphalt. Unfortunately, this is not the case throughout Poelenburg. The national route is not a separate bike path in red asphalt. There is only one separate bike path toward the roundabouts at the neighborhood entrances. Throughout the neighborhood, there are no separate bike paths, and cyclists must share the roads with cars. Existing bike paths stop at Darwin Park. It takes 15 minutes to bike from Poelenburg to the station.

Bikepath

Bikelane

Slowtraffic Poelenburg

National bikeroute

Green

Poelenburg is next to a large nature reserve, but there is no direct connection between the neighborhood and the green area due to the A8 cutting through. There are few trees in the streets. Trees in Poelenburg are often found in the inner courtyards. There is no main tree structure in the neighborhood. Darwin Park is the large green park in the neighborhood, characterized by grass and tree clusters. Each building block has a green semi-public courtyard.

Natura 2000 area

Citypark

Courtyards

Main tree structure

Green analysis

Zoning

Besides housing, Poelenburg has three other functions. There are two shopping clusters connected by a slow traffic route, Darwin Park, and allotment gardens. Just south of Poelenburg is a large sports facility, but there is no clear connection to this area. Additionally, you need to be a paying member of one of the sports clubs located there to participate. On the other side of Darwin Park is a school cluster. Zaandam’s city center is located on the other side of the Zaan, with only one bridge connecting the two areas.

City Park

Industrial area

Sporting area

Store cluster Community gardens

Zoning

Private ownership, single family homes

Block Level

There are three different building blocks present in Poelenburg, creating a geometric street pattern. Each block can be classified based on density, ownership, height, and orientation. All blocks are approximately the same size: 120x120 meters.

The building blocks next to Darwin Park consist of privately-owned single-family homes with private gardens. The block is intersected by a pathway connecting the inner houses to the street and parking spaces. Front doors face each other, and some sides of houses face the main street. These houses are two stories high.

Social housing, single family homes

Social housing, apartment buildings

The second building block is a set of townhouses owned by the social housing corporation. These houses face inward towards the block and either have a backyard or a side facing the main street. They share an undefined public space between their entrances. This public space, which is well maintained, runs through the middle of these blocks, providing either a path through the block or parking spaces. These townhouses are two stories high, with occasional roof constructions.

The third building block consists of an L-shaped portico apartment building of five levels with a large green courtyard containing a freestanding tower of 13 levels. These buildings have entrances facing the street, but the ground floor of both structures is occupied by storage boxes. The courtyard often has a playground or sports field inside but no pathway leading to it from the street.

Street Level

These three building blocks are all situated alongside each other on the street. Traveling from Darwin Park towards the street Poelenburg, you experience each block in sequence. You start by seeing the side and front gardens of the privately-owned houses, then the back gardens of the social housing townhouses, followed by the parking space of the flats, an open space of the courtyard, and the side of the portico flat, before reaching the parallel road that no longer connects with the main street.

Because the street is located between gardens and the backs of buildings, the sidewalks are often positioned between parked cars and fences. The sidewalks are typically 2.1 meters wide, but neighbors gradually encroach upon them with their gardens.

Streetlights are positioned to illuminate the cars, causing shadows on the sidewalk. At night, the streets feel particularly unsafe because the shadows cast by the fencing and housing obstruct your view ahead.

during the day

Back

Back Side

Clusiusstraat

Clusiusstraat at night

Back Side

Clusiusstraat, bikestreet during the day

Wachterstraat during the day

Clusiusstraat, bikestreet at night

Back Side

Back Side

Jasperstraat during the day

Jasperstraat at night

Back Side

Initiation

There are no set rules for working with a community when you want to collect their stories. You do not know from the beginning what story you will end up telling. I was present from February until May in various situations. I went as an urbanist to talk to professionals, as a person to connect with neighbors and just listen to their stories, and as a mother to bike around with my family. Poelenburg came to live under my skin. A collection of all the stories I gathered is presented in the booklet ‘Groeten uit Poelenburg’and showcased in my mural. My journey had its ups and downs.By being sincere and interested in the daily lives of the people in Poelenburg, I quickly made connections with them and was no longer just a guest. This was evident when I had to start paying 1€ for my cups of coffee. By this time, I thought I had made enough of a connection to tackle one of the issues I had discovered in the neighborhood: the Werewolf.

The Werewolf of Poelenburg I started showing up unannounced during the day at the community center Poelenburcht. Mostly adults were present at the time. It was very busy around 10:00 – 13:00. At 10:00, the ‘Papiermolen’ program started, where people from the community center helped neighbors with their paperwork. Around 12:00, soup was served, and many people came to enjoy a delicious lunch together.

By asking people, “What do you find beautiful in your neighborhood?” I collected many stories about hope and how people saw the neighborhood had changed in recent years. But they warned me about the night; people would not go out at night. All the adults told me

there were youths who committed crimes and did drugs at night. It wasn’t safe.

So, I went outside to see what I could observe during the day that might cause the feeling of unsafety at night. The results are shown in chapter 4.1 street level on page 31-33. Additionally, I noticed that the newly constructed buildings were designed to be very closed off toward the streets; doors and windows were pushed back into the façade. Fences were high, and windows were covered by curtains. While walking on the street, I saw that people were afraid to show their houses to the street. I also saw few spots for the youth to hang out safely; they had no designated area.

At 15:00, the youth were taken off the streets by the youth workers to provide them with activities. I decided to stick around to verify this story with them. I asked them the same question about what they found beautiful. They did not see the changes of recent years. So, I asked them point blank about the feeling of unsafety at night. They were surprised because they also felt unsafe at night and did not go outside. They said drug-dealing criminals from Amsterdam coming into the neighborhood at night were the reason they would not go out. The youth were very aware of their reputation in the neighborhood and said they wanted to behave because they did not want to turn out like the youth in 2016.

I knew what I had to do: I had to go outside at night. My partner drove me around the next night. We saw very few people on the street. There were also few streetlights and many dark shadows. At a certain point, we were followed by a police squad car. As the only car driving through the neighborhood, we stood out.

Just like the werewolf is a mythical creature, there seemed to be a mythical creature on the streets of Poelenburg at night. Because the neighborhood had received such a bad reputation, people did not know their neighbors anymore, and the streets were poorly lit, making it feel like there was a werewolf. I’m sure there used to be a werewolf. But in this situation, you can do two things: continue to tell the story of the werewolf or empower the people by looking the werewolf in the eye.

I knew what I had to do: I wanted to give the neighborhood the opportunity to look each other in the eye again. I wanted to start working with the youth to create a safe hangout spot for them, where they could spend time without causing trouble. It would also be a place where they would need to take ownership and show that they did not want to cause trouble, helping to rebrand the youth’s reputation in the neighborhood.

I had made connections with the youth workers, people from the municipality, and people from the Pact, and I pitched my story (See pg. 55). People recognized my story and thought my solution of working with the youth to create their own spot sounded like a good idea.

The Pact said they had to think about my pitch. They didn’t know me or how many people I had spoken to. They asked if I could get a couple of the youth I spoke to come and pitch their idea to us. Maybe then they would be willing to realize this spot for them, under their conditions. This condition meant that the youth involved would have to be named, photographed, and showcased in the newspapers during these meetings.

I started thinking of 100 different ways to get the idea across that the youth had sketched and thought of this place with me after I pitched the

idea to them. Because I knew that even having one of them come and speak to the director of the Pact was about 10 bridges too far for them, I decided to go back to them and tell them what the Pact pitched to see their reaction.

The youth were upset that the Pact did not believe them. To them, it felt like they would be outed to their community if they hosted that meeting. So they suggested that we write a letter together, and they would have a week to sign it. In the meantime, I would work out our sketch a bit. We set a date for a week later.

I showed up a week later, and they weren’t there. I was upset and didn’t know what to do or how to take this. One of the youth workers told me they were probably at the other location, and we drove there. And yes! That’s where they were. I got excited again; I could continue the project.

We sat down, and they seemed more closed off. I explained again what we were going to do: write a letter to the municipality to start the project of creating a hangout spot together. They asked if they could be dismissed while I wrote the letter for them, and they would sign it. I agreed.

They came back with big bags of chips and other snacks. I showed them the design and asked why they were not as excited anymore. They told me they did not believe in it anymore. Nothing stays nice. What we have drawn up is way too beautiful. People are going to trash it. Nobody feels responsible for these places. It won’t happen.

In the end, I thought I’d left with nothing…

Nine

Tools

Initially I thought that having something realized in the neighborhood would be the proof that my method worked. Now I’ve taken a step back I have learned that the goal of D.I.T. Urbanism is not to realize something quickly. I have personally learned nine valuable lessons through the process. These lessons are tools that I carry with me every day, and will allow me to be reminded that I need to not be stuck in the Initiation phase, but also take the next step to the Consolidation phase, which will allow me to reflect upon all the stories I have gained.

Wear comfortable clothing

I don’t know anything

Not one vision

Be an activist

No unwanted gifts

Be present

Empower people

Be curious

No unwanted gifts

- Check, double check, triple check

- ‘No’ is also an acceptable answer

- Be invited to do the work

- Find ways to work with different parties together, everybody’s got to give

Be present

- Show up on different times

- The length of a project matters, longer projects have more impact and build better relationships

- The goal of working together is not about the big end result, it is about the process and creating meaningful partnerships

Wear comfortable clothing

- Wear clothing that will make you approachable, and inviting. Match the neighborhood, be relatable

- Match the customs of the neighbors, for instance hand gestures

- Let yourself go from guest to part of the interior

Listen

- Hear the personal story

- Don’t make assumptions, check what you hear

- Let yourself be surprised

- Come without a clear agenda

I don’t know anything

- We don’t know all the answers as a designer, but we can find them by working together

- We need other professions to get things done

- The community are the experts of the neighborhood

Not one vision

- There is clear power in collaboration

- Be flexible

- Respond to opportunities, even though they might not look like they match

Be an activist

- Help shape policy

- Create long lasting partnerships within the community

- Teach the system about the research done

- Trial & error approach, not everything works right away, but learn form failure

- Take action, don’t just advise

Empower People

- Create and offer tools to turn social impact into data

- Create and offer tools to let people do things themselves

- Offer tools for people to understand opportunities

- Being aware of something, does not change behavior

Be curious

- Use different methods of observing, drawing, photographic, sounds etc

- Go at different times, during different times of year

- Connect with all different types of people

- Partake in different activities to get to know people

Consolidation

For the consolidation phase in Poelenburg, I have created 7 different posters that show the process for seven different story designs. Those will be shown starting on the next page.

1. LOCAL STOREFRONTS PREPARATION

Current urban opportunities Story Design Designers inspiration

Current situation

Spatial realm

Stores are located at some corners of blocks. All the roads that are directed to these corners are not connected to the bigger network of the city.

Around the bigger shopping areas there are smaller local shop opportunities in the building blocks. These are located at the corner of the big acces road. But because the road recently got transformed, they are now located next to the parallel routes.

Social realm

You can’t look in from the outside, there is no showcasing of the goods. There is no place around the store for people to meet and hang out.

There are two bigger clusters of stores, one where Tanger market is the big grocery store. The other spot is Vomart with a couple other stores. There are no cafés in the neighborhood.

There is one empty storefront in the bigger

It looks desolate with smashed windows. This is opposite the mosque and next to the bus stop.

‘We would like to have more different types of stores.’ ‘We would like cafes to hang out and meet each other, because our houses aren’t big enough.’

The goal is to create a local chapter of commerce with local residents that maintain local property, offer education and guidance on entrepreneurship to other owners and host parties to connect people. This can create a connection between local residents to showcase unique entrepreneurs in Zaandam. While in the end this will create a destination to invite other people in.

COURTYARDS

INITIATION

CONSOLIDATION

Spatial realm

There are two different types of courtyards, both owned by the social housing company. The first are the courtyards between semi detached houses with gardens attached to it. As shown in gray. The second are the courtyards in between the big apartment blocks. Often with a playground or sporting field inside. This is shown in green

Social realm

The zoning of the inner courtyards is not clear, people have taken ownership of some locations, but there is a path and some flowers planted. There are no clear entrances or way to connect to people along the courtyards, only unofficial entrances to back yards. It is not clear if people are allowed to use the space other than a traffic route. Current situation

‘I would used to know my neighbors’ ‘We would share food in the courtyards’ ‘Kids always played in the courtyards’

Create a collective backyard for neighbors, where people feel at ease, get to know each other and can share and participate in activities together. Have a space where people collectively take care, can meet to socialize and build up their collective strength to empower one another in other activities.

CENTRAL SLOW TRAFFIC

PREPARATION

Current urban opportunities

Current situation

Spatial realm

The route is located in the heart of the neighborhood, but has no other slow traffic routes connected to it. It was originally thought of as a promenade to Zaandam city center and the farm field on the other side of the A8. The connections to the other locations has never been realized. This results in a slow traffic street in the heart of the neighborhood.

Social realm

The route connects two stores, the Vomar and the Tanger market. It is not lit well, and there are no entrances along the route. People do not feel safe during the day, because the municipality put in speed bumps to stop bicyclist from speeding, the bicyclists ride on the sidewalk now. People no longer use the route, unless it’s an actual necessity.

People tell stories about how they get attacked in this street, because there is no vision on the street. They point out that people bike too fast on the sidewalk, cause trouble and throw things.

INITIATION

CONSOLIDATION

Create an inviting, meaningful route through the community’s center. This will create an opportunity for people to see on another on a daily basis on their daily commute. This needs to be a safe route where people can meet and be connected to other parts of the community and Zaandam.

# of people spoken to Age

‘People bike on the sidewalk, because there are speed bumps placed inside the bike path’

‘I do not walk here at night, because it is dark and you can’t see anybody’

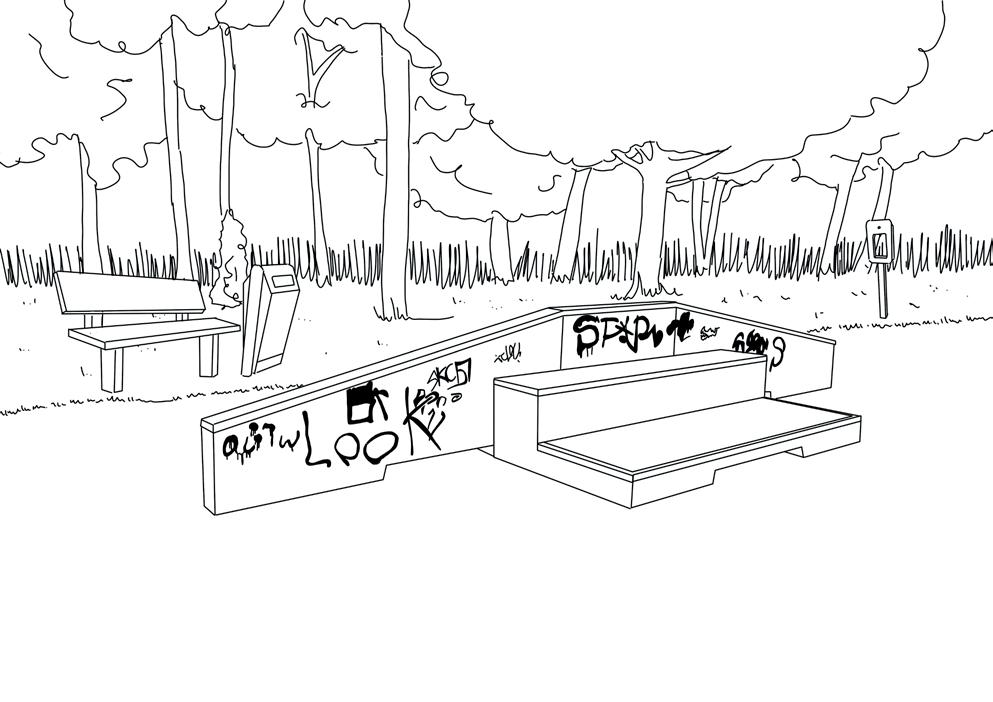

4. YOUTH HANGOUT SPOT

Current urban opportunities Story Design

Current situation

Spatial realm

The spot that is designed to be a skate park, but these youth don’t skate. There are no benches, so kids can’t hang out. There are no paved routes to the benches, so they get dirty feed and have to sit in the mud. There are no inviting spaces for the youth to just sit and hang out.

There are a couple of benches placed in Darwin park where youth sometimes hang out. Behind the mosque is a little bush the youth call ‘Melis’ where they also hang out.

There are no hang out spots specifically designed for the youth, because they have a bad name since the 2016 uproar.

One of the spots youth would hang out in the summer ‘Poelenburg Beach’ has since been closed.

Social realm

Youth get taken off the street by youth workers. They get brought to hang out in the community center ‘the Poelenburcht’ or the newly opened ‘Kleurenrijk’ in the neighboring area Peldersveld.

Youth feel like they have no place to go and hang out with a lot of friends. Their houses are too small to host 12-15 kids. But they don’t always want to hang out in the community centers.

‘I just don’t want to get my shoes dirty anymore.’

‘If we’d have a place like this, you’d never see me in the community center anymore’

Designers

Create a spot where youth can hang out without causing trouble for others. Showcase that the youth aren’t an issues by giving youth a purpose in the community. Have youth be part of the community again, so that they’ll feel like they’re also a worthy part of society. Let them for instance become a neighborhood watch or let them be responsible for the location.

PREPARATION

Current situation

Spatial realm

There are two types of playgrounds in the area. There are corporation playgrounds in the inner blocks of the bigger apartmentbuildings. Not all the bigger blocks have a designed playground. Some have a sports field, others just grass with trees. Than there are a couple of playgrounds in Darwin park, geared towards the older aged children.

In other courtyards you can see that parents have placed trampolines and small slides for the smaller kids.

Social realm

The playgrounds do not inspire the neighbors. They voiced that the natural playground lacks color and the sand underground causes trouble when kids come at home all sandy. They wish to have colorful playgrounds, to inspire kids to play. There are few benches for parents to watch their kids. Playgrounds for little kids are separated from the big kids, and parents often have multiple kids so they do not attend playgrounds together.

There is a need for parents to meet up in a save place, that is not a dealer spot and away from car traffic for kids to play.

Parents feel saver when there is a fench around the playground. They are affraid to leave their children unattended because someone could come in, or they could wander off.

‘The nature theme is wonderful, but all the sand gets dragged into the house and it’s not very colourful’

‘I would like a place to sit somewhere and watch my child play’

CONSOLIDATION

Create a space where children can play and grow without limitations. A space where parents can meet and bond with their children and other parents. This space should be without stress so the parents get time to reflect and grow.

PREPARATION

Current urban opportunities

Current situation

Spatial realm

The sporting fields come in two flavors; basketball court or soccer field. The fields are either located in the bigger building blocks, or in Darwin park. There is no official path or seating around the courts. The Kraijcek field is the only field that has both soccer goals and basketball posts. This is also the only sheltered field.

Social realm

If there is a program put upon one of the courts, it fits within the available fields. Participants don’t have influence on the program or the sports being offered. The Kraijcek foundation hosts sports in their own court offered by interns. The youth workers from the community centers will sometimes take the youth to play in one of the other courts. They do not offer other sports, as they do not have the equipment.

There is an independent sports coach, who is a resident in the neighborhood. Noes tries to involve adults who do not speak the Dutch language into creating a community. Her goal for this is to connect people through sport, not to have them actively engage in sports.

CONSOLIDATION

The aim is to create a healthy community and have people be excited about the current opportunities. Let people see that with creating their own program, other opportunities are possible. Have the community realize they don’t need to wait for programs to be offered to go out and do something, but have them showcase what they’d like to try.

‘I just really want to play padel’ ‘We only have panna fields and a basketball field in the area’

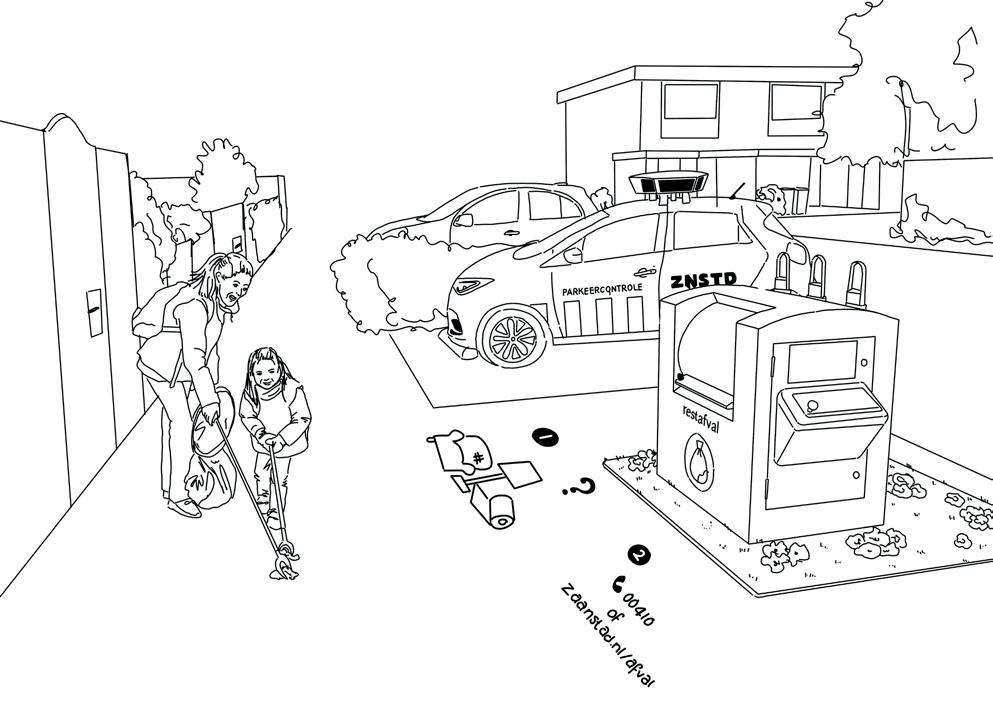

GARBAGE COLLECTION

Current urban opportunities Story Design

Current situation

Spatial realm

There are two different private waste systems in this neighborhood; the underground bins close to the apartments and the personal bins close to the individual houses. The personal bins have a recycling program. The apartments have only residual waste.

Next to some seating in Darwin park, there is also some trash cans.

Because there are three different systems of garbage collection in this neighborhood, there are three different parties to collect the garbage.

Recently, residents have received a pass to open up the underground bins. The municipality tries to combat garbage disposal that way.

Social realm

The people feel punished when the bins are full, the don’t feel like the municipality is taking the neighborhood serious with the lack of cleanliness. The municipality feels people are too lazy to participate in correct waste collection practices.

The municipality lets the collecting party actively go through trash that gets put next to the bins, even when they’re full. The fine for littering is €195. This is too much for a lot of people to pay.

‘Nobody takes responsibility over the trash. It takes 3 months to get a hold of someone who can clear it.’

‘People from the municipality go through your bags, even when bins are full’

CONSOLIDATION

Designers inspiration

The goal is to have no more nuisance from littered waste. This is done by creating a shared responsibility for the garbage problem. Get to know the neighbors so people will feel safe to challenge unwanted behavior. Have people be in charge of the problem, by adopting a bin, rather than let them feel they’re a victim of the system.

I have lots of plans to turn this neighborhood around, and they’re all fun initiatives with the neighbors. But the municipality never wants to listen, or I need to go through months of conversations with different people to get a small thing realized.

- Ingrid

66, the Netherlands April 3rd, 2024

CONSOLIDATION

My research has proofed me that creating an empowered neighborhood is not done alone. That is why I have developed a set of steps to inspire other designers to implement D.I.T. Urbanism in their designs. D.I.T. Urbanism can be a great tool for designers to empower the people in the neighborhood that they are working on, while also starting the conversation about bridging the social and spatial realm. What we do in our profession has impact on the people using the space, and in return the people using the space should have impact in the design. Let’s do it together:

Preparation

1. Desk Research

Create an urban analysis of the neighborhood. Map structures, plans and the current status of the neighborhood. Create a historical analysis. Offer insight in how the neighborhood has developed up until now.

2. Location visit

Visit the neighborhood and observe what is there. Document your observations through pictures, create voice notes and sketching.

Let’s do it together!

3. Analyze data

Let your location visit and desk research lead to current opportunities that you want to tackle. Look at it from the perspective of improving the neighborhood, rather than pointing out what is wrong.

4. Professional interviews

Interview professionals who can teach you about people and the community. Let yourself be inspired. Conduct interviews with a goal of enriching your research through a peopleoriented approach.

Initiation

5. Visit the neighbors for the first time

When you visit the neighbors for the first time, pick a location where people come together and just be present. I suggest a community center. Let yourself be a guest, explain your goal to people. Goal for these first couple of visits is to get to know each other. A good question to ask people is: ‘What do you find beautiful about your neighborhood right now’. This will result in both good and bad stories. Write these stories down. Write characteristics

down of these people.

6. Be present

When you visit for the first time, have an idea of when you plan to be back. And than come back. Talk to people again, sharpen their stories. Sketch a story design, and check with them whether the story is correct.

7. Fact check

When people speak about specific incidents, locations or behaviors of others; do not be afraid to fact check. Go and visit the locations for yourself, visit the incidents and check up on the others. This will result in creating a dialogue between the different parties, but will also start to take down possible walls that are up. This is important, as you want to create an atmosphere where people will work towards a positive attitude towards working together.

8. Story Design

Create your story designs. This can take any form, but the idea is that different parties can understand your design. Work with a medium that works for your neighborhood. This could be a drawing, models, movie or sound.

Consolidation

9. Concepts of Empowerment

Based on your research, you can define concepts of empowerment. These concepts define topics that would empower people in the neighborhood. They are based of things that happen or are being said in different Story Designs. They can be considered the common themes of empowerment. Empowerment can happen in both the spatial and the social realm.

10. Bridges of Empowerment

Identify what the bridges of empowerment are for each of the story designs. The bridges are different for each story design, but should always be a step to empower people. This could be done through creating a tool, a meaningful connection or creating a platform.

11. Quantify your stories

Create data from the stories and the Bridges of Empowerment. This will show two things. First, it shows that the people are not alone and that multiple other people have raised the same concerns. Therefore, it could start connecting people who want to work towards the same goal. Second, it will show to prospective partners that there are a variety of people who are raising the same questions. It will showcase the diversity in the neighborhood, through which all people are connected.

12. Reflect & next steps

Take a step back from the first round of D.I.T. Urbanism. Reflect upon what you have learned about the neighborhood. Draw a conclusion from this, and prepare for the next steps. See who you need to connect with in order to make the next round more specific. Think about the tools that you could offer the community to take the next step.

Succes in looping

Success in this method is not defined by realizing a project in a single iteration of the phases. Instead, success lies in establishing meaningful connections with the neighbors. This is done so that you are continually invited to work towards empowering them to eventually lead projects themselves. The goal of D.I.T. Urbanism is not to create a single plan on the neighborhood, but to foster the energy and enthusiasm necessary for residents to invest in their own community.

Empowering a community is not something that you can do on your own, or is done in one day. My research shows me that connecting both the social and spatial realm is a valuable asset to designing neighborhoods. This is something in my daily practice that I do not practice in, but something I would like to start doing.

Working with the people in Poelenburg has really given me the gift of learning that people are not the ‘complaining neighbors’. We have just not been taught how to participate with people on their level. When you come down to them, listen to them and explain your position, people were willing to think about the future. Creating a level playing field so that all parties could be involved in developing neighborhoods is so important and rewarding.

Through this process I have transformed myself from trying to become an expert to becoming an extension of the community. This has been a meaningful transformation to me, as it will allow me to connect to marginalized communities in the future in a more meaningful way. By

CONCLUSION

inspiring others to pick up a similar approach to redevelopment of these neighborhoods, I hope to stop the degeneration of certain areas were a concentration of marginalized people can happen. Not through the physical removal of these areas, but through giving people a voice to stand up for themselves.

Thank you, community of Poelenburg, for showing me your hidden network and worth. I strongly believe that by continuing to participate in D.I.T. Urbanism, the beauty of the community can be shown to others.

Beckhoven, E. van & Van Kempen, R. (2005) Large Housing Estates in Utrecht, the Netherlands: Opinions of Residents on Recent Developments. Utrecht: Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht.

BURA. Expertmeeting post-war neighborhoods, 1 Nov. 2023, Amsterdam, Van Eesteren Museum.

BZK (14 november 2022). “Miljardeninvesteringen Voor Bereikbaarheid Woonwijken in Heel Nederlands.” Volkshuisvesting Nederland, https:// www.volkshuisvestingnederland.nl/actueel/nieuws/2022/11/14/ miljardeninvesteringen-voor-bereikbaarheid-woonwijken-in-heelnederland. Accessed 25 June 2024.

CBS. (2017) Veel Naoorlogse Stadswijken Sociaaleconomisch Zwak, https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2017/46/veel-naoorlogse-stadswijkensociaaleconomisch-zwak. Accessed 25 June 2024.

CBS. (March 18th 2024), “Gemeentebegrotingen; baten en lasten naar regio en grootteklasse” Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Den Haag

Van Egmond, J., and van der Drift, M. (January 13th 2022), “Poelenburg, Zaandam: Krachtwijk, prachtwijk of achterstandswijk wordt hard getroffen door coronacrisis” 5 Dagen, NTR & PowNed, Hilversum

Kaulingfreks, F. (2019), “Kansrijk Poelenburg/Peldersveld” Hogeschool inHolland, Zaanstad, https://www.inholland.nl/onderzoek/ onderzoeksprojecten/kansrijk-poelenburg-peldersveld/

Kragten, R. (2022) “Van Lelystad Oost tot Breda Noord: Kabinet pompt miljard in kwetsbare wijken” Newspaper, RTL nieuws, Hilversum

Kuyt, T. (April 9th 2024) “Geen ligstoelen, smoothies en speeltoestellen meer: Zaandams stadsstrand Poelenburg Beach wordt gesloopt” Noordhollands Dagblad, Amsterdam

Marlet, G., Poort J. & van Woerkens, C. (February 2009) “De Baat op Straat” Atlas voor Gemeenten, Utrecht.

Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties (BZK). (April 2024) “Handreiking, woonwijken van de toekomst; vormgeven aan de naoorlogse wijken in transitie.” MOOI NL, Den Haag.

Ministerie van VROM (VROM) (July 2007). “Actieplan Krachwijken, van Aandachtswijk naar Krachtwijk”. Ministeriee van VROM, Den Haag

NHNieuws (November 12th 2023), “Kinderen bekogeld met vuurwerk tijdens Sint Maarten in Zaanse wijk Poelenburg”. NHMedia, Hilversum

Nicis Institute (23 juni 2008). “Bloei en verval van vroeg-naoorlogse wijken”. Den Haag

Noordhollands Dagblad (January 2nd 2024) “Dertien arrestaties na gooien vuurwerk naar politie en vernieligen in Poelenburg Zaandam, ME ingezet” Noordhollands Dagblad, Amsterdam

De Orkaan (July 22, 2021) “76 nieuwe parkeerplekken Poelenburg” De Orkaan, Zaandam

De Orkaan (March 31st, 2023). “110 neiuw woningen: Poelenburg-Oost (#ZaanstadBouwt)” De Orkaan, Zaandam

Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving (PBL) (2008), Krachtwijken Met Karakter, NAi Uitgevers, Rotterdam

Schildkamp, V. & van der Wal, C. (September 14th 2016), “Treitervlogger filmt om zijn schulden af te betalen”. Algemeen Dagblad, Amsterdam

Schenkeveld, W. (October 16th 2020), ‘Rob Wit (73) ‘monitort’ mondkapjesgebruik in Zaandam-Poelenburg. Noordhollands Dagblad, Amsterdam

SteenhuisMeurs (2022). Poelenburg en Peldersveld, Zaandam. Cultuurhistorische analyse en waardering. SteenhuisMeurs, Rotterdam

Steenvoorden, E., Dekker, P. & van Houwelingen, P. (2011) “Continu Onderzoek Burgerperspectieven”, Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, Den Haag

Zonneveld, J. (July 6th, 2020) “Gemeente en corporaties maken samen werk van achterstandswijk Poelenburg” Gebiedsontwikkeling.nu https:// www.gebiedsontwikkeling.nu/artikelen/gemeente-en-corporatiesmaken-samen-werk-van-achterstandswijk-poelenburg/ Accessed 25 June 2024

Appendix

Poelenburcht, talking

Poelenburcht, talking to

of Maria & Ellis May 3rd 2024

Hands

Who works in Poelenburg

Stichting Maatschappelijke Diesntverlening

Historical plan Poelenburg 1962

Summary location visists

STREET IS FOR CAR

Amsterdam - de Punt

Amsterdam - de Punt Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Nijmegen - Hatert

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenberg

Amsterdam - Laan van Spartaan Nijmegen - Hatert

Amsterdam - de Punt

Amsterdam - Laan van Spartaan Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Nijmegen - Hatert

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Nijmegen - Hatert

BLIND FACADES

TREES IN GRAS

Amsterdam - de Punt

Amsterdam - de Punt

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Nijmegen - Hatert

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Amsterdam - de Punt

Amsterdam - Laan van Spartaan Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Nijmegen - Hatert

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Zaandam - Poelenburg CLOSED

GAR-

Amsterdam - de Punt

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Nijmegen - Hatert

Vlaardingen Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Amsterdam - Laan van Spartaan

Leiden - Boshuizen & Fortuijnwijk

POOR PLACES TO MEET

Amsterdam - de Punt

Amsterdam - de Punt

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Vlaardingen -West Wijk

ONLY HOUSES

Amsterdam - de Punt

Amsterdam - de Punt

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Nijmegen - Hatert

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Amsterdam - de Punt

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Amsterdam - Laan van Spartaan Nijmegen - Hatert

Amsterdam - Laan van Spartaan

A LOT OF SPACE

Amsterdam - de Punt

Vlaardingen - Westwijk

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Arnhem - Presikhaaf

Nijmegen - Hatert

Vlaardingen Westwijk

Zaandam - Poelenburg

Deventer - Rivierenwijk

Final word of acknowledgment

My graduation has been an amazing process through which I was able to learn and develop myself as an people oriented urbanist. I loved working with all sorts of people, and I would like to say a word of thanks to those who have helped me in this process.

First, thank you Martin Probst, Ania Sosin & Arjen Oosterman for always pushing me when needed, but reeling me back in when it was time to focus.

To all the professionals that let me interview them, it’s been wonderful to learn about your different work, thank you: Nancy Boom, Kasper van der Vlies, Saskia de Vin, Guus Frenaij, Kees Schuyt and Marcus Bouma.

Arthur van der Laaken, Ashwin Karis and Killian Lode, thank you for looking over my shoulder and helping me boost my mood.

To my friend group called ‘the Things & Stuff’, thank you for letting me high jack our BBQ’s to share my stories about the process the last year.

Thank you Lucy Soepenberg for picking up the phone when it was most needed, and always believing in sharing the story of communities.

Last, but certainly not least, I would like to write my thanks to my family: Jorn & Minthe Duwel. Thank you for letting me take this rollercoaster ride, while you were cheering me on from the ground.

Groeten uit| Ellis Soepenberg | 2024