Choreographing resilience

Fig. 1: Picture of a model, Strzyza’s garden number 4: ‘‘The Perforated Pipe’’.

Fig. 1: Picture of a model, Strzyza’s garden number 4: ‘‘The Perforated Pipe’’.

Fig. 1: Picture of a model, Strzyza’s garden number 4: ‘‘The Perforated Pipe’’.

Fig. 1: Picture of a model, Strzyza’s garden number 4: ‘‘The Perforated Pipe’’.

Choreographing community resilience along the flooding and disappearing Strzyza stream

Author: Justyna Kinga Chmielewska

chmielewska.justyna.kinga@gmail.com

Landscape Architecture Master Thesis

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

Committee members: Nikol Dietz (mentor), Jarrik Ouburg, Anna Fink

External committee: Berdie Olthof, Marie-Laure Hoedemakers

Amsterdam, Neteherlands, 2022/2023

Print/Bind: Drukkerij Raddraaier

Presenting seven gardens that restore the Strzyza’s presence, ecology and natural capacity to store rainwater.

By uncovering pieces of the buried underground stream, people who live around it can recognize its presence and learn how to coexist with it.

Through movement and little gestures of care: DIY work (re-arranging found materials, gardening and maintenance) people can reengage with the forgotten stream and acknowledge they are living in the flood zone. All of the choreographed actions improve the preparedness of communities for living in the floodplains of the Strzyza.

These gardens can serve as exemplary spaces, which highlight the buried and forgotten Strzyza: a catalyst for changing habits and controlling mindsets towards nature.

Each year there are fewer of them. Some have disappeared underground, from time to time reappearing in a littered ditch between buildings, to sink again somewhere below ground. This is the fate of the Strzyza and other tributaries of the Vistula river.

Almost all of Vistula’s tributaries have disappeared from the landscape of Polish cities. In Poznan the stream was interrupting city’s development, so it was rerouted. In Krakow all rivers except the Vistula have disappeared. Wrocław’s streams were forgotten. They disappeared and when they reappeared during flooding, 40% of the city was underwater. Each summer the Rawa stream gradually dried up until one day it completely vanished from Katowice. In Gdansk, two kilometres of Strzyza were channelled through underground pipes.

Over the past 30 years I have observed the slow disappearance of the Strzyza from the landscape of my hometown. I still remember the Strzyza from my childhood, when together with my grandfather Leon we visited Strzyza’s lush riparian forest. For us the forest around Strzyza was a collective home that provided shelter during hot summer days. Slowly, shopping malls and highways replaced the forest. As the stream started disappearing right in front of our eyes, my grandfather’s favourite word simply became ‘Strzyza’. The name of the stream became so stuck in my head that I decided to find out why it disappeared and how could I bring it back.

The government buried two kilometres of the Strzyza underground, selling the land to diverse investors. In present days, some stretches of the Strzyza belong to commercial companies, some to privatized neighbourhoods, and the rest is still owned by Gdansk’s municipality. As a result, the creek has no coherent planning, and many parts of it have uncontrollably disappeared underground.

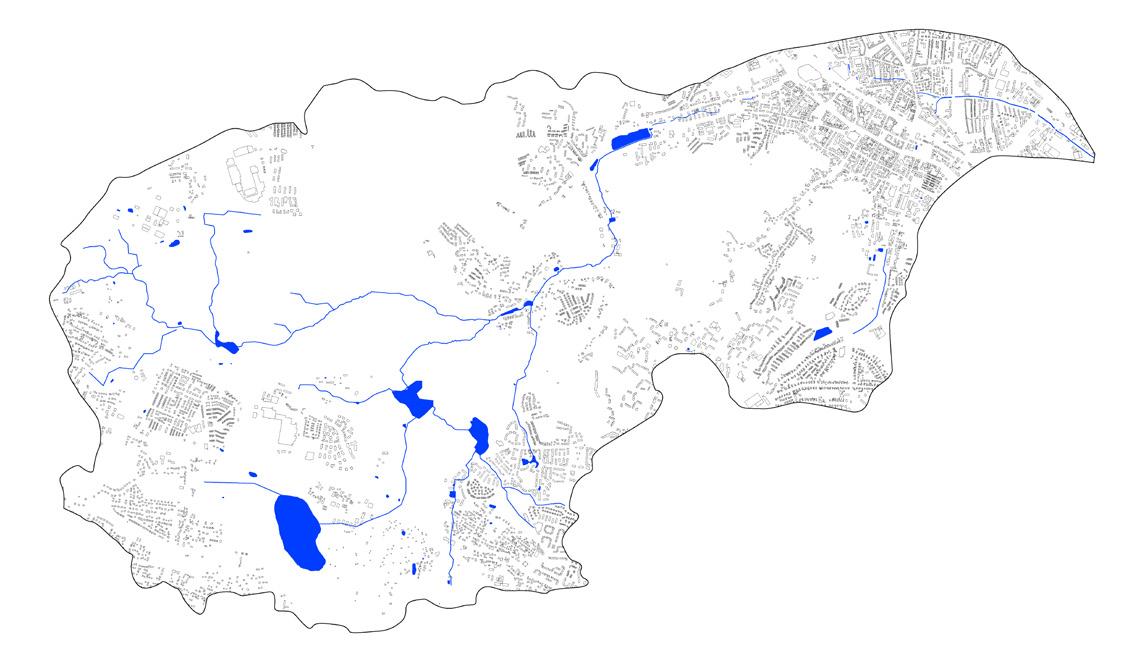

Map of Poland. Vistula river crosses Poland from mountains to Baltic Sea; Fig. 4: Pomorskie province and its regional importance in draining the Moraine Plateau from the rainwater is big; Fig. 5: City of Gdansk with its water system. Strzyza’s watershed (grey) is the last tribuary of Vistula river and a drainage of the moraine plateau; Fig. 6: Strzyza’s watershed. The stream starts in a forest (140 m npm) and streams down through the city of Gdansk (0 m npm).

Strzyza remains invisible for most parts of the year (Fig. 7A, 7B). It reappears only during big city floods (Fig. 8A, 8B). The urbanised part of the creek is canalised or placed underground in concrete pipes. geometrically shaped canal system of the creek leads to dangerous flash floods that citizens have to deal with.

The consequences of burying the Strzyza in underground concrete pipes are catastrophic. The rainwater collected in the concrete channel of the creek has no place to go and floods reappear in the city. The invisible stream doesn’t warn its citizens about the upcoming floods. Besides the dangerous floods, losing the Strzyza led to losing our collective memories. During medieval times monks inhabited the stream, and thanks to its fast-flowing current and the local hops (Humulus lupus) they have produced beer. Nowadays there are only a few watermills left in the city, as memories of the stream’s once-prospering habitats. Not only have we lost touch with the richness of the river landscapes, but we have come to the point where we see our streams only when they flood.

Strzyza dissapearance has led not only to floods, but also to the loss of a rich history, ecology and our collective memory

Along the banks of the Strzyza, back in the 18th century, plenty of breweries started to appear, using the fast-flowing water force of the creek. Created right next to it, ponds were a valuable source of industrial water and ice. Besides the breweries, monks built along the creek water-powered grain mills, sawmills, grinding mills, etc. For Nobel prize-winner Gunter Grass the brewery pond was a playscape of youth, which he describes in his books. The area of the pond was a village enclave in the city centre. In the pond people used to fish and Gdansk’s youth bathed in it. Children played in the thicket between the pond and the creek. The smell of fermenting yeast and processed malt hung in the air, and the brewery buildings dominated the area, like some large, medieval castle.

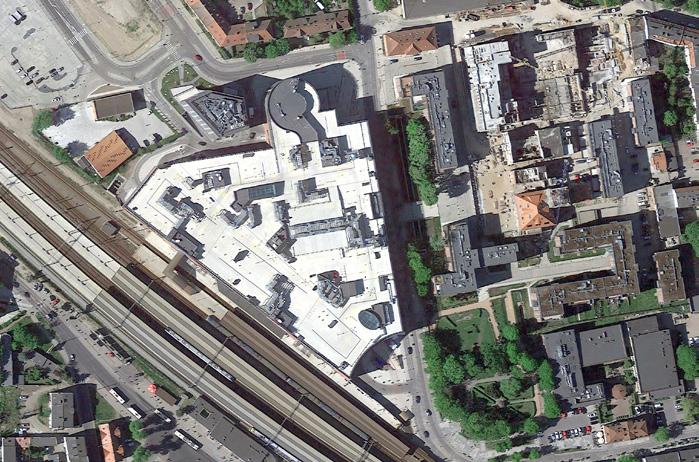

In 1972 the first of the Pepsi-Cola bottling plants began to be erected. Gierek’s vision of opening Poland’s economy to Western Europe meant the imminent destruction of the playscapes of the Strzyza. Gierek was a Polish communist politician who is known for opening communist Poland to Western influence. In a short time, an aluminium hall for Pepsi replaced the icehouse. The pond and its banks became in-accessible. The greater part of the Strzyża disappeared inside a tunnel. When Pepsi started production, the carts disappeared, replaced by the smell of exhaust fumes from Pepsi delivery cars. And so, with capitalism and the idea of opening towards the international economy, the playscapes around the brewery pond disappeared. Today, a huge shopping centre was built on the dried bed of the brewery pond.

16: Strzyza in 1807: Water basins built by monks served the development of the city. They used its fast flowing current to produce goods; Fig. 17: Strzyza in 2022: Most of the surface water has been canalised and placed underground, because of intensive urbanisation of the city. The reminding from 1807 buildings are marked black.

The landscape of the Strzyza was formed during the Ice Age, as a result of melting glaciers. Along the coastline of the Baltic Sea the glaciers created a very specific landscape, resulting in big height differences. The Strzyza starts its course on the Moraine plateau (140 metres above sea level) and flows towards Baltic Sea. It is 13 km long.

The Strzyza flows through the old, post-glacial gully, which was formed by the waters of the melting glacier. The Strzyza is the last tributary of the Vistula river, one of the most important watercourses, which drains the waters of Gdansk’s highland plateau.

On a regional scale, the Strzyza fulfills an important water drainage function for the moraine plateau, which is one of the rainiest areas of Poland, with 800-900 mm of rain annually. Heavy rainfall on the hills of the moraine plateau flows down towards the city causing annual flooding.

The uphill forested part of the creek has eight retention basins that store water during heavy rainfall. This solution offered by the government can store around 200,000 m 3 of rainwater, which is 5 times too little. During heavy rainfall some million m 3 of water per day falls on the whole watershed of the Strzyza. When the retention basins fail to store all the rainwater, the water starts to overflow towards the city.

The urbanized stretch of the creek is canalized or placed underground in concrete pipes. The geometrically shaped canal system of the creek is unable to absorb or slow down the rainwater coming from the moraine hills, which leads to dangerous flash floods.

29: Alnus Glutinosa tree, which is a common species for the riparian forest habitat, Fig. 30, 31: Major Natural areas of Gdansk in the scale of the city and the scale of Strzyza’s watershed. One of major natural areas are located on the edges of Moraine Plateau. The 140 m steep terrein difference made these areas uninhabitable.

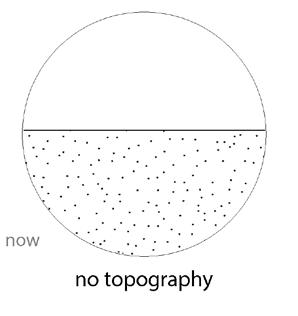

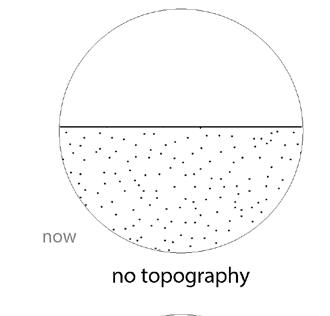

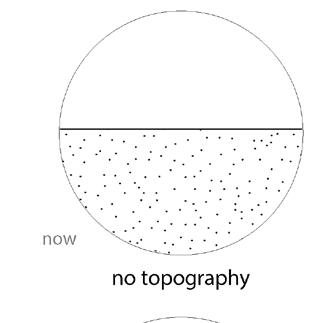

flowing rainwater

porous surfaces, sandy soils enable infiltration of rainwater

Sand

recharged underground water table

Fig. 36, 37: The lower part (floodplain) of the Strzyza creek lays on top of sandy, porous soils. Before urbanization of the Strzyza watershed flowing downstream rainwater was infiltrated into the soil. The rain was re-charging the underground reservoirs of sweet water. Fig. 38, 39: Nowadays, this whole area is mostly urbanised, with little to no porous surfaces. Sealed-off surfaces in the lower part of Strzyza stream lead to floods. Water has little to no space to infiltrate.

lack of porous surfaces in the city leads to floods Baltic Sea

Fig. 40: The biggest rainfall occur in the mountains regions and by the Baltic Sea: 800-900 mm of rain annually, Fig. 41,42: On the regional scale the biggest rainfalls occur on top of Moraine Plateau, making it an important drainage on a regional scale. Fig. 43: The biggest rainfall occurs during hot summer months. The diagram shows the amount of rain falling during floods (x) in just one day in comparasence to waterfall during the entire month.

cloud formation wind towards land

fast run-off through city

evaporation during high temperatures

higher air temperatures due to climate change

Urbanization of the Strzyza floodplain made this area more prone to flash floods. Rain has no place to nflitrate, so it flushes into the city, causing floods. (Fig. 44,45), Vegetation and spongy riparian soil play an important role in the local, regional and global rainwater cycles. It is important to acknowledge that Strzyza is not just a water line, rather it is an interconnected ecosystem. Its water is everywhere; in the air, soil and plants (Fig. 46).

On one hand, I know the Strzyza from its positive side. Together with my grandfather during summer we visited its lush riparian forest and slowly flowing current. On the other hand, my grandmother, as a municipality worker, had to deal with the flooding. She walked from one house to the next, meeting people who had lost their entire possessions. After the catastrophic floods she was involved in calculating the material losses of people whose houses were flooded.

As a result of urbanization and heavy rainfalls during hot summers, the floods keep on reappearing in the Gdansk city. But why are floods happening? We have destroyed the natural riparian ecosystem of the Strzyza, which was able to naturally absorb rainwater. River vegetation is able to absorb and store enormous amounts of water. Healthy soil is able to absorb and store water for long periods of time, and then slowly give it back to the atmosphere. The creek used to flow naturally, but today it has been straightened to fit geometrical shapes. The canalized riverbed speeds up the water flow. On top of that, rainfall will only get stronger in the coming years, due to progressing urbanization and climate change, which brings more weather extremes.

reoccuring in the city flash floods are catastrophic for peopleFig. 47: A man trying to cross the street during a flash flood event in 2016, phot. Adam Warzawa, Fakt.pl.

1. kiepinek 59063 m3

2. jasien 48487 m3

3. nowiec 8336 m3

4. gorne mlyny 2630 m3

5. ogrodowa 1500 m3

6. potokowa-slowackiego 6700 m3

7. srebrniki 65 000 m3

8. kilinskiego 16000 m3

9. wilenska 7070 m3

Fig. 48: Govermnent fights the floods by designing retention basins. The total amount of the retention capacity in all of the basins is 217 686 m3, while the m3 of the most extreme rainfall is about 4 mln m3 during few hours. Fig. 49: When the technical solutions (retention basins) fail to collect all the rainwater, the Strzyza stream floods the lower laying part of the city.

‘‘An estuary demands gradients not walls, fluid occupancies, not defined land uses, negotiated moments not hard edges. In short, it demands the accommodation of the water not a war against it which continues to be fought by engineers and administrators as they carry walls inland to both channel the rain runoff and keep the river out.‘‘

Anuradha Mathur, Dilipda Cunha

Flash floods effected the interiors of the houses, as seen on the images above. This is an apartment of Dorota and Wieslaw Borys, who live in the floodplein of Strzyza stream. The walls were destroyed by the flooding waters. Source: Trojmiasto.Wyborcza.pl

The uncertainty of the flooding river landscape presents itself by the temporary DIY elements people build around the Strzyza. This landscape has been changed so many times that there is no point in fixed solutions. In this chapter I have gathered images of the DIY works surrounding the Strzyza. The pictures were taken by me and my sister in 2021/2022. These temporary elements were the biggest source of inspiration for my project, since they symbolize the emancipation of people and their willingness to shape their environment.

environ

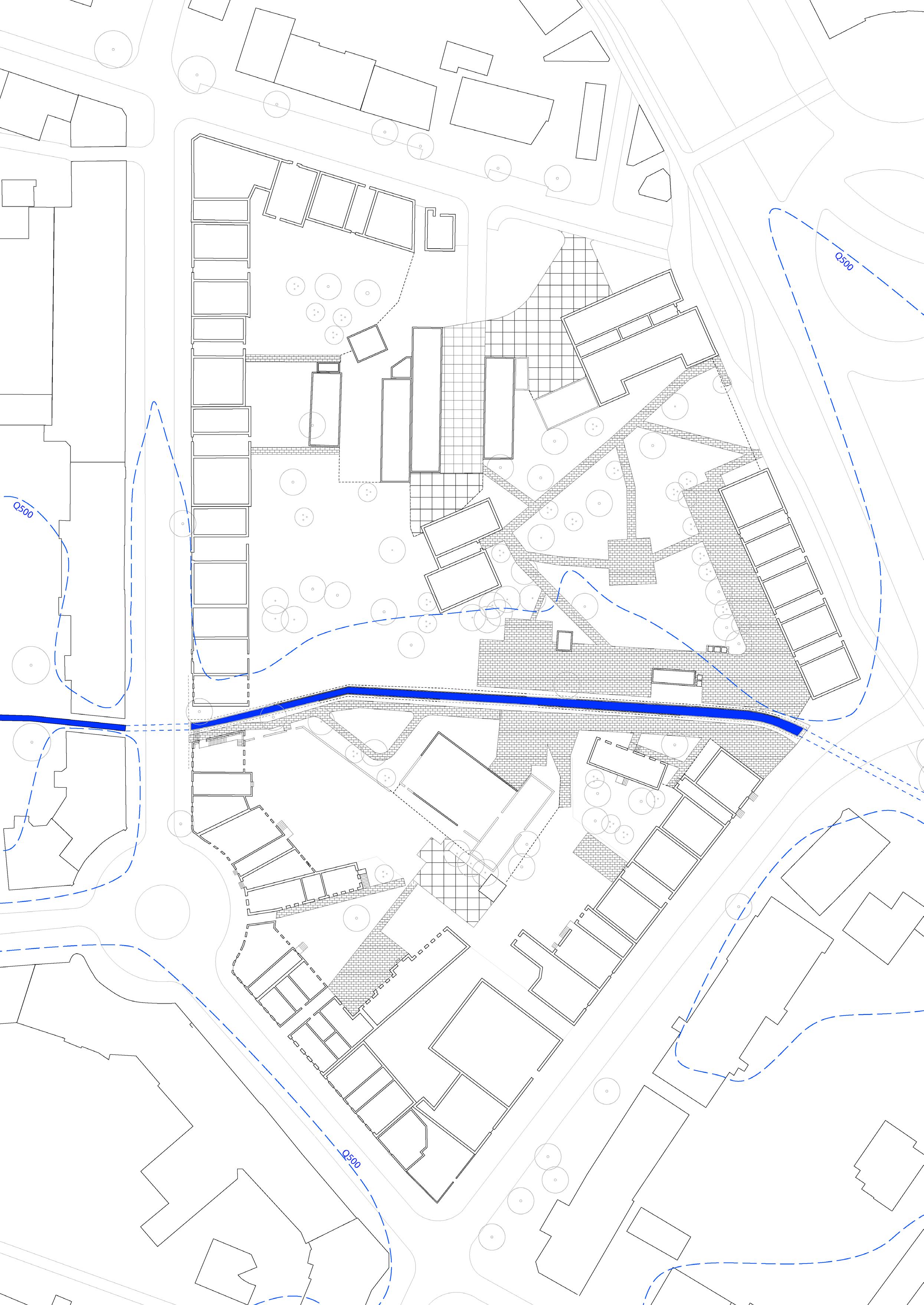

mentFig. 64: Toilet turned into a planter, a private garden at the edge of the Strzyza stream canal.

legenda:

public space

Q500

housing cooperations

private investors

Fig. 65: The map of the ownership illustrates how many areas around the Strzyza stream are privatized (dark grey and grey color). Because of big land privatization around Strzyza it is almost impossible to realize one bigscale top down plan to solve the problem of the flooding and the dissapearance of the river.

Fig. 66: privatized, but belonging to the municipality, self-made garden at the edge of Strzyza.

Fig. 66: privatized, but belonging to the municipality, self-made garden at the edge of Strzyza.

Fig. 67: privatized, but belonging to the municipality, self-made garden at the edge of Strzyza. Re-used car tires serve as pots for plants.

Fig. 67: privatized, but belonging to the municipality, self-made garden at the edge of Strzyza. Re-used car tires serve as pots for plants.

Fig. 67 68: privatized plot of land belonging to the municipality. Here the inhabitants have made an interesting construction out of found on site materials.

Fig. 67 68: privatized plot of land belonging to the municipality. Here the inhabitants have made an interesting construction out of found on site materials.

69: Another act of spontaneous privatization of municipal grounds. Somebody collected the concrete tiles found at the waterbanks of Strzyza. My assumption is that they were washed away by the flood and easy to collect.

Fig.

Fig.

Fig. 70: A pile of bricks and concrete blocks created after the demolition of the old parking garage.

Fig. 70: A pile of bricks and concrete blocks created after the demolition of the old parking garage.

Fig. 71: Self-made house for stray cats.

Fig. 71: Self-made house for stray cats.

Fig. 72: Self-made house for stray, homeless cats.

Fig. 72: Self-made house for stray, homeless cats.

Fig. 73: Frozen water collecting barrel. Found on public grounds in the area of the Courtyard garden (mentioned later in this book); Fig. 74: People decorate the existing, unatractive walls of old parking garages with plants in pots.

Fig. 73: Frozen water collecting barrel. Found on public grounds in the area of the Courtyard garden (mentioned later in this book); Fig. 74: People decorate the existing, unatractive walls of old parking garages with plants in pots.

Fig. 75, 76: Old car tires are perfect flower pots! The inventivness of inhabitants of Gdansk living alongside Strzyza stream has no end.

Fig. 75, 76: Old car tires are perfect flower pots! The inventivness of inhabitants of Gdansk living alongside Strzyza stream has no end.

Fig. 77: Concrete blocks used as temporary sitting elements in the upper floodplains of Strzyza.

Fig. 77: Concrete blocks used as temporary sitting elements in the upper floodplains of Strzyza.

Fig. 78: Pigeon shed at the banks of Strzyza stream.

Fig. 78: Pigeon shed at the banks of Strzyza stream.

During floods the inhabitants of Gdansk create yet another type of temporary element. When heavy rainfall comes the whole flood zone is covered with sandbags. During hot summer months the creek floods and inhabitants protect themselves from the force of nature. People living along the Strzyza are forced to deal with the floods themselves, since many of the sites around the Strzyza are privatized. The government provides tools to deal with the floods - sandbags, which are redistributed all around the city. Citizens living around the creek create protective dikes at the front of their houses. Plastic sandbags are the only protection tool people have to cope with the floods, while the prevention tools are unable to store enough rainwater.

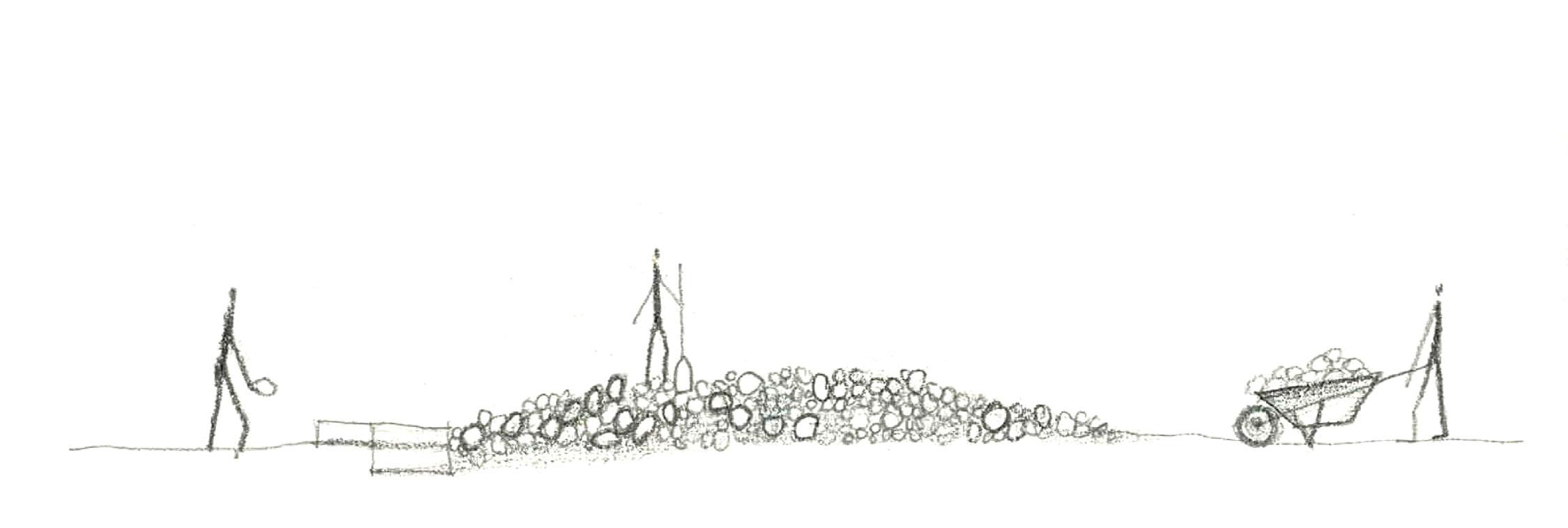

Because of the privatization of the areas around the Strzyza, there is no possibility for solving the problems of floods in a top-down, big-scale way, providing a technical solution for a city. Instead, the government is trying to help citizens the only way they can: with sandbags. During floods the city delivers tons of sandbags and plastic bags and spreads them in diverse parts of the city. People gather around the piles of sand, collect them and move them to the entrances to their houses.

themselves from the flooding streamFig. 79: Sandbags dam built in front of the entrance to the house, phot. Agencja Gazeta, Wyborcza.pl

Fig. 80: Handdrawing of people filling up splastic bags with sand. Fig. 81: First step in the process of building sandbag dams is collection of sand from the nearby beach, This tasks performed by the municipality and skilled workers. Fig. 82: Next step is bringing the sand from seaside to public spaces in the inner city, Fig. 83: Citizens gather around the sand piles brought by the municipality to later re-distribute them (Fig. 84) around the entrances to private houses (Fig. 85). After reoccuring floodings people know exactly how to perform the task of building temporary dams.

To summarize the analysis, the natural conditions of the Strzyza landscape are defined by the rainy conditions of moraine hills on the edge of the Baltic Sea. This landscape is in a constant process of change, destruction and renewal. In natural circumstances, in the area of the riparian forest, these floods brings something positive: they spread seeds in the rich hummus soil, and they provide water for vegetation specific to this area, creating river habitats unique on the scale of Poland. The riparian forest and spongy peat soils store enormous amounts of water. These ecosystems are a crucial component of the global rain cycles.

However, urbanizing, privatizing, canalizing and burying underground the Strzyza stream, sealing off the porous sandy soils, lead to recurring floods. Floods are catastrophic for the inhabitants of Gdansk. Their households and shops get flooded. Fast-flowing water endangers people, who struggle with the chaos and destructive force of the water. Not only are they insufficiently protected, but most of the year they are also unprepared and unaware that they live in the floodplains of the Strzyza. The creek has disappeared from the surface of the city. Out of sight, out of mind.

The government tries to help private owners by providing a protective tool: the sandbag. The sandbag is the only tool people have to fight the enormous force of flooding water. Sandbags are spread around the city along the edges of private entrances, remaining and deteriorating in the cityscape. They are the only physical reminder of the Strzyza’s existence.

Therefore, to create a more symbiotic relationship between people and nature, we need to learn how to live in the flooding zone again. New and temporal ways of living could create a safer cohabitation between the Strzyza and the inhabitants of Gdansk.

In order to restore our rivers, we need to change our way of thinking: instead of fighting the water we need to learn how to live with it, learn its rhythms, let it in and design for the extreme weather conditions, where all living organisms are equally welcome. With this project I want to uncover the hidden potential of the Strzyza’s natural capacity to store rainwater.

Since the areas around the Strzyza have no coherent ownership, it is important to act on all ownership levels. I believe that the way to restore the Strzyza is through various interventions: from engineered city investments on the land belonging to the municipality to simple community actions, which will take place on areas owned by privatized neighbourhoods. Diverse ownerships around the creek make it one top-down plan impossible. The existing conditions require choreographed and precise actions, instead of a fixed big-scale design. At this moment, the only way to fight the consequences of the Strzyza’s disappearance is by local collaborations between diverse owners. Only together will we be able to deal with the consequences of the lost river’s ecosystems. My role in bringing the people and the river together is by choreographing diverse processes and actions.

Tasks of garden creations, which will be performed by the collaboration between municipality and citizens and could be easily repeated by the citizens living in the floodplains, both on municipal oand private grounds:

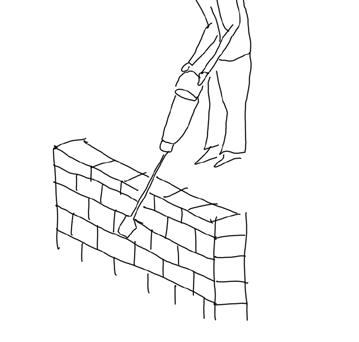

removing pieces of Strzyza stream walls

removing unnecessary pavements and uncovering the soil

re-using and re-purposing pavements creating new garden walls which strenghten the new protective dikes and work with water flow

depending on the collected material size, they are repurposed in diverse ways

re-shaping the topography, creating space around Strzyza

re-using the collected soil to create new floodplain edges, which slow down the flooding waters

bringing more air to flattened by cars topsoil

planting new riparian trees to enhance the infiltration and slow down water flow

planting new riparian vegetation

Tasks of reparation, maintanance and harvesting:

harvesting plants making beer out of harvested plants

harvesting rainwater

re-arranging dead branches taking care of the soil life repairing new garden walls and objects

ecological maintanance: maintaining Strzyza ecology to minimum

building sandbag dams

The goal of the various interventions in this project is to mitigate the flooding by slowing down the water and increasing the porosity and natural storage capacity of the Strzyza’s watershed. The first step in renaturalizing the Strzyza is uncovering it and reconnecting its water with the soil, creating natural conditions for the development of spontaneous, riparian vegetation to reappear.

The engineered interventions of uncovering the Strzyza on municipal land need to be performed under the supervision of water engineers, and with the financial support of the municipality of Gdansk and the guidance of a landscape architect. Uncovering the Strzyza from the underground and renaturalizing the waterbed by demolishing parts of the stream’s walls will lead to its spontaneous renaturalization.

Simpler than the engineered uncovering, the task of renaturalizing the Strzyza’s floodplain, its later reparation and maintenance can be performed by communities or individuals under the guidance of a landscape architect, engineers and the municipality.

Municipal, collective and private interventions around the Strzyza explore new ways of living with the stream. Learning new skills can help prepare for future floods. Repeated tasks will become part of people’s daily habits and can be passed from one generation to another, creating a resilient, collaborative community.

collaborative interventions on municipal grounds that can serve as an example for the inhabitants

We need to invest our public money in urgent matters, such as those connected to our disappearing rivers, which increasingly flood our homes. The city should help its citizens and take responsibility for their wellbeing by minimizing the impact of floods.

The municipality of Gdansk could finance the gardens as part of a participatory budgeting project, realizing them together with inhabitants, engineers, ecologists, landscape architects and city planners. In this way the project can be realized with public money, as a collaboration between citizens and the city. That collaboration is crucial in creating safer communities that are better informed about the flooding.

All of the proposed interventions can be performed with the materials found on site and river vegetation spontaneously appearing. Instead of adding more, this project is about removing and re-arranging.

This project is a showcase of exemplary interventions to uncover or renaturalize the Strzyza in places where it is still possible - on land belonging to the municipality of Gdansk. The first step in achieving the goal of this project will be to create seven showcase gardens around the Strzyza. These small gardens are the first phase in the process of uncovering the creek. The new gardens can stimulate movement and create space for new habits and new ways of interacting with the flooding creek. They reveal small pieces of the creek from the underground, reconnecting the citizens with the chaotic and unpredictable nature of the Strzyza.

These gardens aim to be upscaled in the future. After being realized, they can serve as examples of ecological resiliency for people living in the floodplain of the Strzyza. The DIY actions of maintaining and repairing can be performed by communities and private owners, mitigating the influence of the floods, changing the relation between people and the hidden Strzyza. A catalyst for changing habits. This project is not a fixed design but rather a set of tools for communities affected by the disappearance and flooding of the Strzyza. This design is never finished. It aims to be readjusted and renewed in response to constantly changing conditions and needs.

In the labyrinth of privatized land I searched for leftover sites, still belonging to the municipality, which have the potential to become community gardens around the Strzyza.

The locations of the seven new gardens are chosen based on the typology of the surroundings and the typology of the riverbed. From the Strzyza hidden in the underground pipes, flowing under the asphalt roads, to channeled in the concrete riverbed of the Strzyza, flowing slowly past old parking garages. I singled out seven typologies existing in the floodplain of the Strzyza and selected the most suitable for the intervention locations.

Fig. 87 - 93: Chosen intervention areas. The 7 locations are representative typologies which can be found in the floodplain of Strzyza stream. From heighest laying to lowest and closest to the Vistula estuary locations are as follows: The Old Garages (Fig. 87), The Historical Watermill (Fig. 88), The Dekert Street (Fig. 89), The Perforated Pipe (Fig. 90), The Courtyard (Fig. 91), The Hot Pipe (Fig. 92), The High Pipes (Fig. 93).

Legenda:

existing parks and abandoned construction sites existing private gardens

Q500, flood surface

direction of the water flow during the flood existing surface water (Strzyza stream)

existing, canalized, underground water (Strzyza stream)

new, renaturalised Strzyza stream

new resilient community gardens

new topography, small hills, wadis

1.

2.

3.

1.

2.

3.

First typology, on the highest grounds of the Strzyza floodplain are the ‘Old Garages’. This typology is characterized by the linear basin of the Strzyza stream canalized in concrete. Here, on the banks of the Strzyza one can find many old, one-storey parking garages. As an intervention I propose to demolish one of the parking garages and transform it into a new entrance to the first garden. The green doors of the existing parking garage are re-used to enhance the physical border of the unpredictable, renaturalized stream’s garden. The concrete walls of the old garage (big concrete blocks) are used to create stairs, paths and new islands in the riverbed, which help slow down the flowing water and, at the same time, renaturalize the Strzyza’s waterbed.

Fig. 95: Renaturalized Strzyza’s stream bed. Re-erranged pavements create porosity for riparian vegetation to reappear in the urbanized river bed. By reconnecting water with soil created conditions for re-development of the riparian vegetation. 1. Harvesting plants around renaturalized Strzyza stream; 2. Stairs made of re-used concrete blocks from the demolished old garage; 3. Re-used concrete blocks are placed in the middle of the stream to slow down the water.

Fig. 100: Drawings of garden creation actions: planting new trees, destroying pieces of old garage walls, destroying unnecessary pavements and its fundaments, creating new topography, which slows down water flow, harvesting rainwater; Fig. 101: Drawings of actions of garden maintanance and harvesting: reparing garden walls and objects, harvesting edible plants, re-arranging dead branches; Fig. 102: Section A-A, zoom-in, red line represents the existing, removed elements. Strzyza´s water reconnected with the soil created natural conditions for spontaneous, riparian vegetation to reappear.

The second typology is characterized by the Strzyza flowing in the underground pipe, being completely invisible. The second characteristic for this area is the historical watermill and the granary standing just across the big highway, which together used to create an urban cluster around the previously existing water pond, created by the Cistercian monks, who used to inhabit the areas around the Strzyza. Today these two buildings are disconnected by the highway, and their history of being connected to water is forgotten. My aim is to bring this history back to life and try to connect the two recently separated buildings by creating this garden.

Fig. 107: Garden creation actions: planting new trees, destroying pieces of old garage walls, destroying unnecessary pavements and its fundaments, creating new topography, new wadis and protective dikes, which slow down water flow; Fig. 108: Actions of garden maintanance and harvesting: repurposing and reusing and repurposing existing pavements, reparing garden walls and objects, harvesting rainwater, harvesting edible plants, re-arranging dead branches; Fig. 109: Section B-B, zoom-in, red line represents the existing, removed elements.

The third uncovered piece of the Strzyza lies underneath Dekert Street. There is very little space available for the intervention. Therefore the incision in the ground to uncover the stream is small, enabling one lane of cars to pass next to it. This garden is accessible through the stairs that lead people below. Reconnected with the soil, air and sun, the water of the Strzyza leads to the development of spontaneous, riparian vegetation, which absorbs and stores a lot of rainwater.

Fig. 114: Actions of garden creation: creating new topography, digging out Strzyz from the underground, planting native species of shrubs which will strngten and protect the soil from being washed out; Fig. 115: Actions of garden maintanance and harvesting: collecting and re-using dead branches, harvesting eadible plants, harvesting rain; Fig. 116: Section C-C, zoomin, red line represents the existing, removed elements. Strzyza´s water reconnected with the soil creates natural conditions for spontaneous, riparian vegetation to reappear.

Fig. 117: Model of the Dekert Street, a man carries sandbags in a barrel, because the flood is coming. He found the sand around uncovered Strzyza waterbed, he didnt have to wait for the sea-side sand.

Fig. 117: Model of the Dekert Street, a man carries sandbags in a barrel, because the flood is coming. He found the sand around uncovered Strzyza waterbed, he didnt have to wait for the sea-side sand.

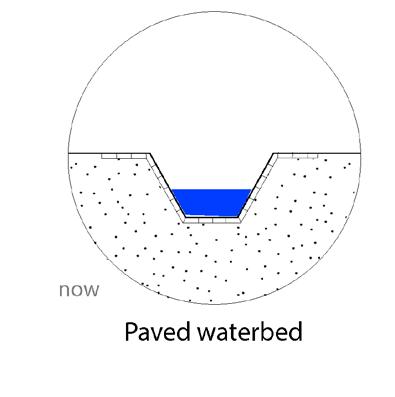

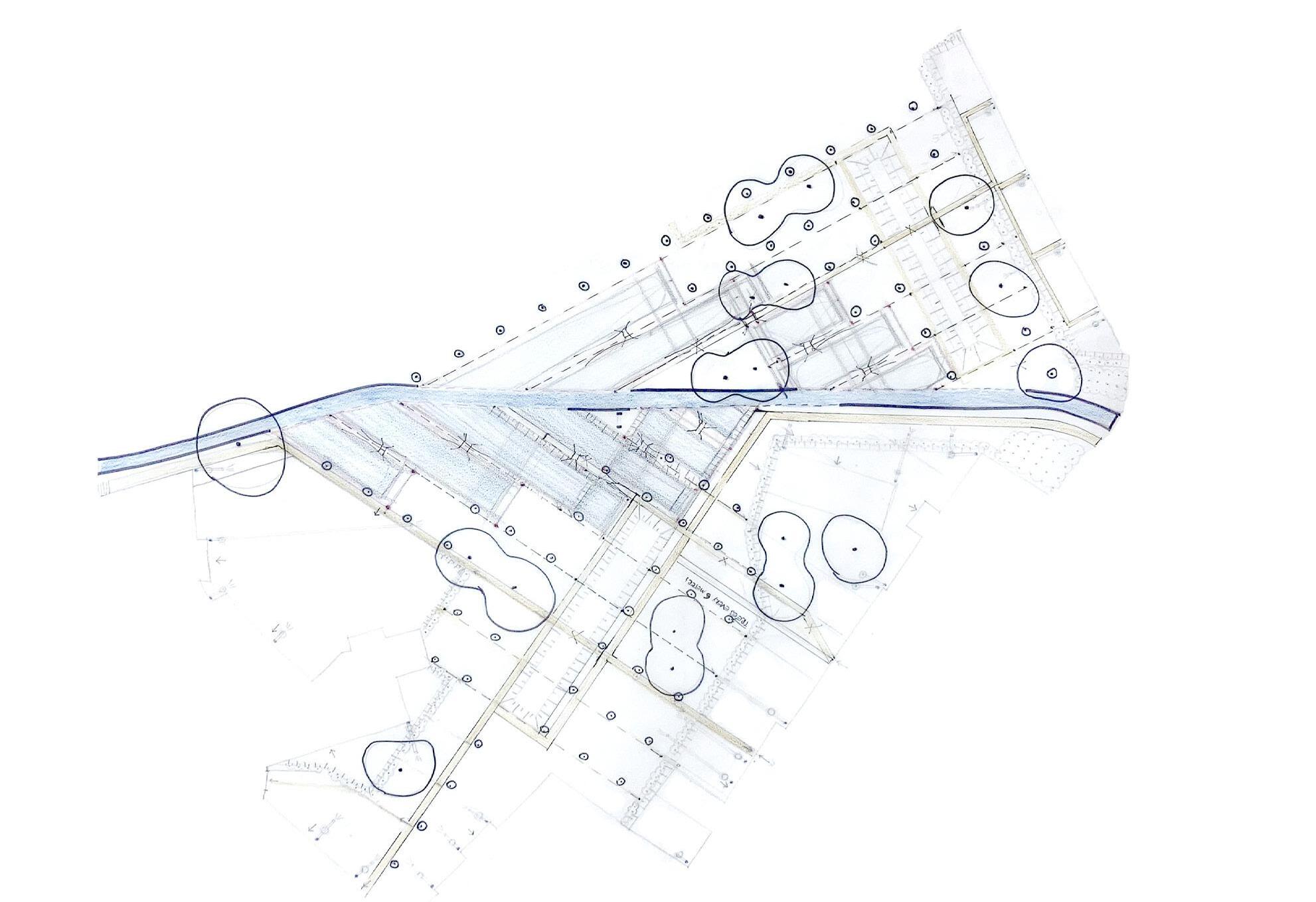

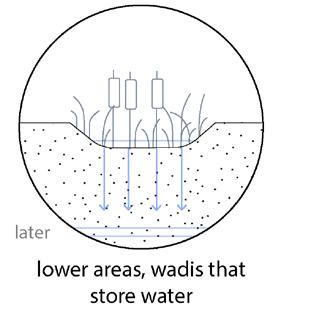

The fourth garden is a big, sandy area with a car park on top of it. Plants don’t grow here and rain doesn’t infiltrate to the ground, because the soil is compressed by the constant movement of cars. The Strzyza flows underground in the concrete pipe and will be revealed to the surface. The pipe will remain in place as a reminder of the creek once hidden underground. The new topography and uncovered stream will create conditions for the development of riparian vegetation, creating a new lush garden in the cityscape.

Fig. 122: Actions of garden creation: digging out Strzyza’s hidden pipe, creating new topography, planting native species of trees and shrubs, which will strengten the soil and absorb rainwater; Fig. 123: Actions of garden maintanance: harvesting plants, harvesting rain, building sandbag dams (made of juta instead of plastic); Fig. 124: Section D-D, zoom-in, red line represents the existing, removed elements. Strzyza´s water reconnected with the soil created natural conditions for spontaneous, riparian vegetation to reappear.

The biggest of the Strzyza gardens is The Courtyard. Here the stream is visible, but fenced off and placed in a geometric canal. The spaces around the Strzyza are mostly paved and the soil is pressed and sealed off by the cars that park here. The courtyard is hidden from the business of the city streets and used by locals in an informal way.

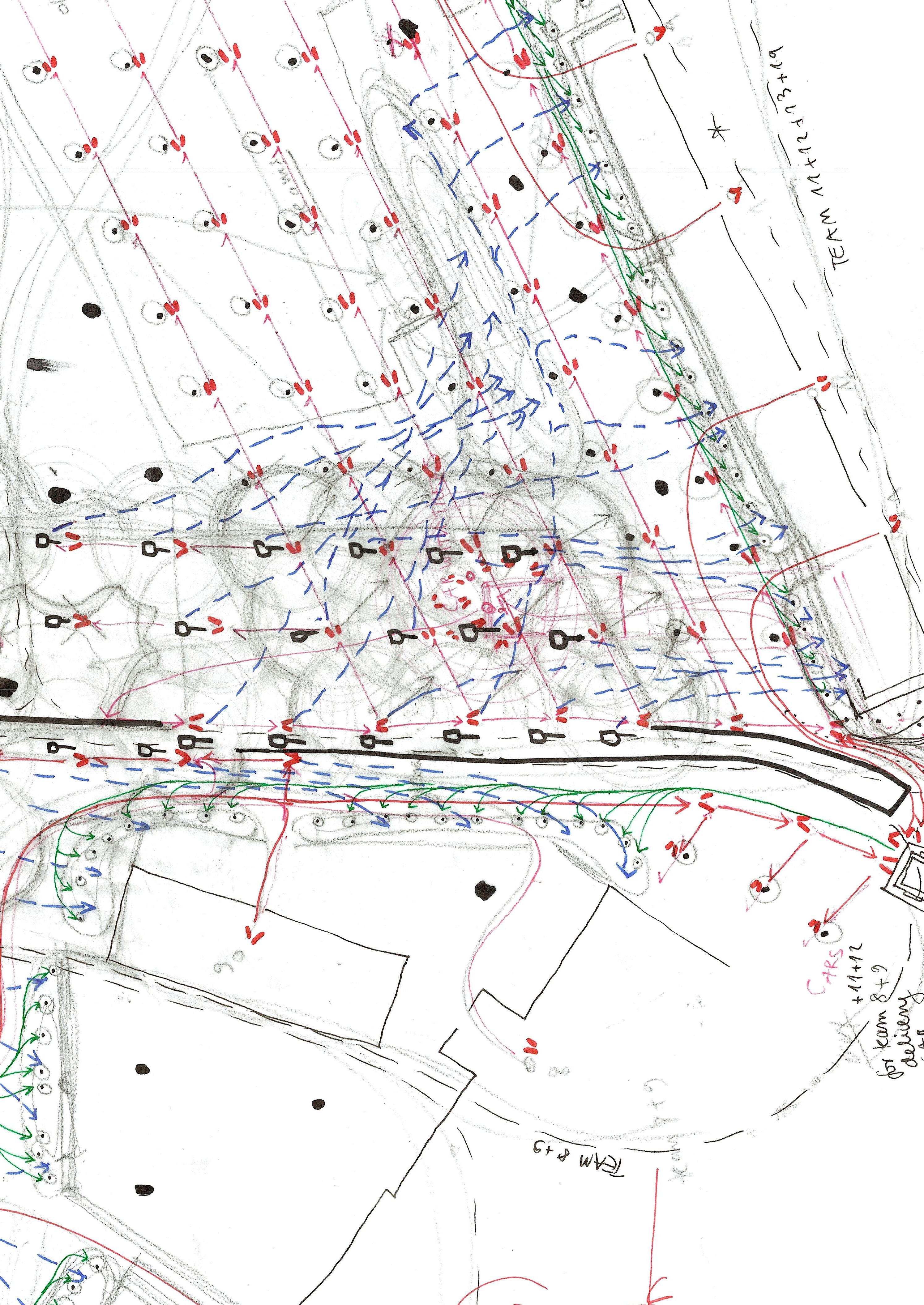

The courtyard could be transformed by the collaboration between the neighbours, municipality, water engineer, ecologist and landscape architect. All of the choreographed actions rearrange the existing materials, creating a new, renaturalized riverbed. In the realization of this garden, not only the flows of people and materials were taken into consideration. Flows of the flooding waters were also a crucial factor in the development of this garden. Slowing down flash-flood flow resulted in several dynamic design elements. Over time, floods will re-shape this garden, which will need repairs and acts of care.

Fig. 131: Actions of garden creation: removing pieces of existing Strzyza’s waterbed, creating new topography around it, creating new wadis and protective dikes, re-using and re-purposing existing pavements and concrete blocks after demolishon of parking garages, planting new shrubs and trees in the most necessary places, to protect the soil from water erosion and slow down the flash flood waters; Fig. 132: Actions of garden maintanance: harvesting rainwater and plants; Fig. 133: Section E-E, zoom-in, red line represents the existing, removed elements.

Fig. 134: Because of heavy cars driving through the courtyard, the top soil was degraded. Its sealed-off surface doesnt allow vegetation to grow and water to inflitrate into its deeper layers; Fig. 135: After reparation of soil, and creation of new slope between Strzyza stream and courtyard surface, spontanous, wet vegetation has a chance to appear around Strzyza.

legenda:

flood reach, having 0.2 % chances of occuring buildings walls fences

pavements (concrete tiles, 1.2 x 0.8 m)

pavements (bricks, 0.1 x 0.2 m)

Fig. 136: Plandrawing of the courtyard, existing situation.

Fig. 136: Plandrawing of the courtyard, existing situation.

creating space around the creek, digging out soil

removing pavement, parking garages and creek’s walls

moving dug-out soil to create protective dikes

moving removed materials

making protective hills

creating new stepping-stone paths and edges of protective hills

Fig. 137: Plandrawing of the courtyard, the movement of materials neccessary to realise the new garden.

Fig. 137: Plandrawing of the courtyard, the movement of materials neccessary to realise the new garden.

Fig. 138: Masterplan of the courtyard garden. First phase after material movement, before the influence of water flows. This drawing focuses only on the new topography around Strzyza.

Fig. 138: Masterplan of the courtyard garden. First phase after material movement, before the influence of water flows. This drawing focuses only on the new topography around Strzyza.

Fig. 139: Masterplan of the courtyard garden. Second phase after material movement, after the influence of water flows. After few months water has reshaped the newly created topography.

Fig. 139: Masterplan of the courtyard garden. Second phase after material movement, after the influence of water flows. After few months water has reshaped the newly created topography.

legenda:

flood reach, having 0.2 % chances of occuring

existing and kept materials:

building walls

trees

re-used and replaced materials:

re-used concrete building blocks

re-used crushed concrete (paths fundaments)

re-used concrete tiles (1.2 x 0.8 m)

re-used bricks (0.1 x 0.2 m)

new topography

rearranged water pipes ending in old bathtubes

new materials:

new trees

new shrubs

Fig. 140: Masterplan of the courtyard garden. Possible last phase. After many years of material movements and the influence of the water forces on the new topography, the garden will take a new, spontaneous form.

Fig. 140: Masterplan of the courtyard garden. Possible last phase. After many years of material movements and the influence of the water forces on the new topography, the garden will take a new, spontaneous form.

washed away part

141: Masterplan, zoom-in: protective, movable islands (dikes), which slow down the flows of flooding waters and re-direct the water; Fig. 142: The movable islands are easy to make, it is just a pile of sand and old bricks harvested from the courtyard; Fig. 143: When island is ready, it can look something like that, Fig. 144: Possible water erosion of the island during flash flood. The islands are not fixed design element, rather they are always reshaped by the flooding water and then repaired by people.

145: Masterplan, zoom-in: rainpipes and bathtubes; Fig. 146: Some people living in the floodzone (inspired by the new seven gardens) decided to use the standard rainpipes as an element to collect rainwater. They pulled the rainpipes from the underground, to collect the water in old bathrubes or buckets; Fig. 147: During rain bathtube fills in with water; Fig. 148: The water can be later re-used, for example for bathing, or watering plants.

re-used crushed paths fundaments

existing brick wall

re-used concrete stones

new wadi

Fig. 149: Masterplan, zoom-in: stepping stone paths are made out of reused and found on site materials; Fig. 150: Depending on the size of material. Big stones are used directly in the flowing Strzyza waterbed and smaller re-used stones create new porous paths on higher grounds; Fig. 151: During flood some bigger stones laying in the waterbed were moved by the force of water.

re-used crushed paths fundaments

existing brick wall

re-used concrete stones

new wadi

Fig. 152: Masterplan, zoom-in, protective sandbag dams, sandbag playfull furniture; The inhabitants are always prepared. After sandbags have reached their purpose, they can be re-used as play elements or furniture. Instead of laying around without a clear purpose, they serve as water ponds or couches (Fig. 153). The new sandbags are made of fabric, a re-cyclable material, which can be made out of a plant grown in the gardens around Strzyza: Humulus lupulus.

Fig. 154: Model of the courtyard with visible, remaining pieces of the walls (light brown color) and new, curvy water flow.

Fig. 154: Model of the courtyard with visible, remaining pieces of the walls (light brown color) and new, curvy water flow.

Fig. 155: Choreoghed material movement in the Courtyard garden. Red colour represent new trees, blue colour represents the movement of soil and green the movement of pavement. Thick black lines are the leftover Strzyza’s creek banks.

Fig. 155: Choreoghed material movement in the Courtyard garden. Red colour represent new trees, blue colour represents the movement of soil and green the movement of pavement. Thick black lines are the leftover Strzyza’s creek banks.

protective islands that work with flash-floods flows

sandy soil able to inflitrate water into the underground water basins

kept existing wall to protect big, existing tree

new, widened creek’s water bed

re-used concrete tiles

Fig. 156: Model of the courtyard, zoom-in on the Strzyza’s waterbanks. On the right hand side the existing Strzyza’s banks were kept, while on the left side the banks were removed and re-used.

new, widened creek’s water bed

re-used concrete tiles

Fig. 156: Model of the courtyard, zoom-in on the Strzyza’s waterbanks. On the right hand side the existing Strzyza’s banks were kept, while on the left side the banks were removed and re-used.

newly planted bushes to strengten new river edges

newly planted bushes to strengten new river edges

re-used stones make paths

Fig. 157: Woman with the umbrella walks on top of the newly made protective, movable island. The island is made of rubble and soil collected while creating more space around Strzyza.

Fig. 157: Woman with the umbrella walks on top of the newly made protective, movable island. The island is made of rubble and soil collected while creating more space around Strzyza.

The hot pipe garden is a place where the cool kids meet during winter days to drink alcohol and hide from the rest of the world, exploring the wilderness. The existing hot water pipe frames this existing enclosure. Here, very small interventions are made. Only a few concrete slabs of the existing Strzyza walls were pushed to the ground, to create more conditions for river vegetation to appear and allow people and animals to approach the stream.

Fig. 159

Fig. 159

Fig. 162: Actions of garden creation: demolishing few walls; Fig. 163: Actions of reparation and maintanance: reparing the existing walls, harvesting plants, rearranging dead branches; Fig. 164: Section F-F, zoom-in, red line represents the existing, removed elements. Strzyza´s water reconnected with the soil creates natural conditions for spontaneous, riparian vegetation to reappear.

Fig. 165: Renaturalised Strzyza’s banks allow for more interaction between paople, animals and the river. Kayaking through Strzyza will finally be possible and safe.

Fig. 165: Renaturalised Strzyza’s banks allow for more interaction between paople, animals and the river. Kayaking through Strzyza will finally be possible and safe.

The last garden lies almost at the end of the Strzyza, where its waters flow into the Vistula river. It is situated under the highly elevated hot water pipes. Here, the demolition of the Strzyza’s concrete banks would create more problems than benefits. Therefore this garden was made without changing its currently canalized riverbed. This garden was created by removing the existing concrete paving and digging out the soil, creating a bioswale connected to the Strzyza by a small pipe. Water can flow through the pipe into the newly created garden, creating conditions for river vegetation to appear here.

Fig. 167

Fig. 167

Fig. 170: Actions of garden creation: digging out soil, creating a wadi, harvesting and re-using existing pavement, planting shrubs at the edges of the garden; Fig. 171: Actions of garden reparation and maintanance: repairing newly made garden edges, harvesting plants; Fig. 172: Section G-G, zoomin, red line represents the existing, removed elements. Strzyza´s water (reconnected with the soil) creates natural conditions for spontaneous, riparian vegetation to reappear.

Fig. 173: Untouched Strzyza’s concrete riverbed. In the background you can notice a small pipe, which connects the new garden with the water coming from the river.

Fig. 173: Untouched Strzyza’s concrete riverbed. In the background you can notice a small pipe, which connects the new garden with the water coming from the river.

I hope my project can be the first step in the long process of accepting and living with the Strzyza . Uncovering the stream restores its physical presence, ecology, history and collective memory. Renaturalizing the Strzyza will mitigate the recurring floods, which in the coming years will only get stronger. Due to climate change, its importance in the city will grow. Therefore my hope is for this project to upscale, from the first seven gardens to a bigger interconnected masterplan. The seven collective gardens will hopefully lead to the upscaling of knowledge among the citizens and the creation of new resourceful private gardens in the floodplain of the Strzyza.

Through collective movement, people will reconnect with their long lost stream. Over time, people will be able to slowly accept the streams they once turned away from. Restoring the presence of the Strzyza stream represents the interests of other tributaries of the Vistula that have disappeared from the landscapes of too many Polish cities.

Fig. 177: Excited about the new gardens around Strzyza inhabitants decided to take shovels in their hands and build more! They have learned new tools in the collective gardens and now they can apply them in their private gardens. Their gardens store and capture rainwater. The life in the soil is well taken care of and riparian vegetation is in full blossom. Just in case the water level goes higher, they always have a bunch of sandbags at hand.

I would like to thank all the people who helped me with this graduation project. Without your advice, inspirational talks and encouragement, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. I consider every project a group work; talking, sharing ideas and influencing each other should be a common practice. As landscape architects we never work alone. Many thanks go to: Clemens Karlhuber, Zuzana Jancovicova, Maike van Stiphout, Fred Booy, Natalia Budnik, Jonas Papenborg, Sylvia Karres, Anna Zan, Magdalena Popinska, Sebastiaan van Heudsen, Małgorzata Chmielewska, Alicja Chmielewska, Daniela Kleiman-Lopez, Carolina Chataigner, Elise Laurent, Jako Hurkmans, Anna Tores, Roel van Loon, Despo Panayidou, Irene Floridou, Robert Younger, Davor Dusanic, Riwi-coll and many others.

I cannot express enough thanks to my committee for their continued support and encouragement: Nikol Dietz Jarrik Ouburg and Anna Fink

Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to my grandmother Maria, who told me stories about the tragedies of people living around the Strzyza, and to my grandfather Leon, who took me on many walks around the Strzyza and taught me how to respect and appreciate nature.

Colophon drawings, collages, models, schemes:

Justyna Chmielewska

photography:

Malgorzata Chmielewska

Justyna Chmielewska

Agencja Gazeta, Wyborcza.pl

Fakt.pl Adam Warzawa, Miroslaw

Pieslak

Dziennik Baltycki

Trojmiasto.Wyborcza.pl

Google Earth

MM Foto, facebook

text:

Justyna Chmielewska

text editing:

Billy Nolan

Amsterdam, Netherlands

2022/2023