GLORY OF THE FOREST

Shahaf

Strickmann

Strickmann

Shahaf Strickmann

shahafst@gmail.com

Master landscape architecture Academy of Architecture, Amsterdam

December 2022

Committee

Jana Crepon (mentor) - Inside Outside Roel Wolters - Smartland

Lodewijk van Nieuwenhuizen - H+N+S

External committee for the exam

Thijs de Zeeuw

Cees van der Veeken - LOLA

Copyright

©Shahaf Strickmann

Glory of the Forest

This graduation project is made with the support of:

“and they dwelt in Gilead, in Bashan, and in its dependencies, and in all the pasturelands of Sharon, to their limits.”

I Chronicles 5:16

In the winter of 2020 cities in Israel were plagued by extreme stormwater floods. Pictures of flooded streets, floating cars and helpless people were all over the Israeli news. As an Israeli who studied landscape architecture in the Netherlands, I was shocked by the lack of expertise to deal with this urgent issue.

Many cities in Israel have been developed in ways that often ignore and damage natural processes. When urban structures were planned and realized, landscape architecture and ecology hardly received attention. This had a negative impact on different landscape systems, such as ecological networks, water systems and biodiversity. In recent years cities are facing the effects of climate change. They suffer from an unusual warm weather in summer as well as urban floods in winter. Every year this phenomenon becomes more extreme. At this pace we may wonder whether people will be able to live in Israeli cities in the future. Therefore we must take action as soon as possible.

I believe I can introduce a new perspective of climate adaptive design approach in the urban environment. In comparison to Israel, the field of landscape architecture receives more attention in the Netherlands and projects have higher standards. In my gradua -

tion project I use the knowledge and expertise I gained in the Netherlands to apply in Israel.

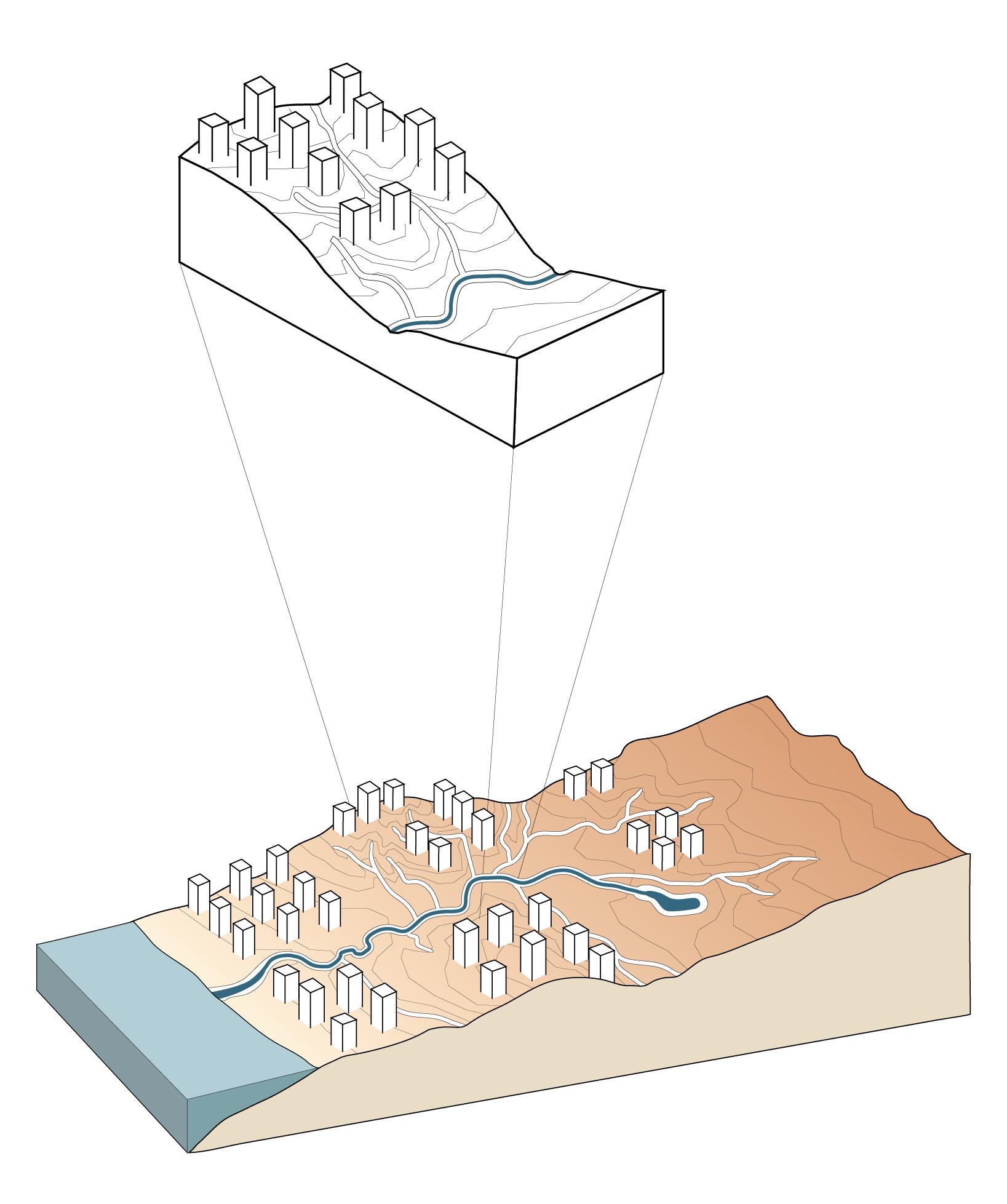

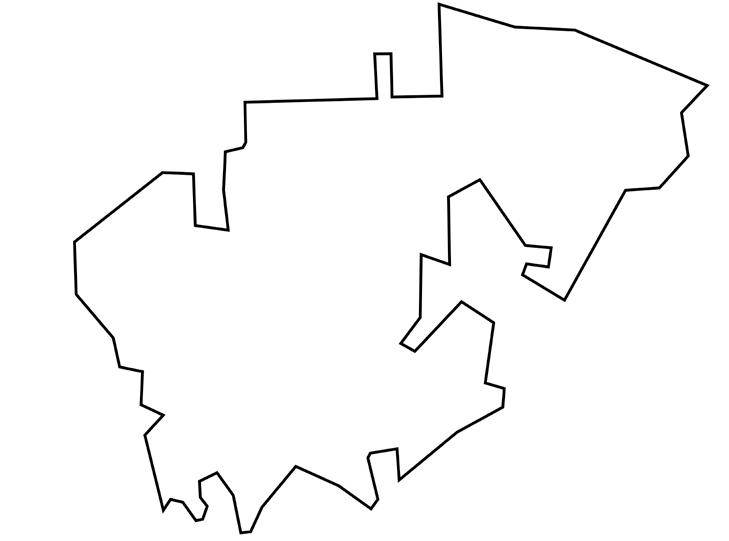

The focus of this project is the city of Hod HaSharon, located in the center of Israel. I chose this city as a case-study because of its interesting landscape and current urban developments. The city of Hod HaSharon has many open spaces that are under pressure of developers who want to build and occupy these grounds with large numbers of houses and buildings. My assignment is to develop an integral and smart strategy for the urban structures that deals with the challenges of the urban landscapes in the city and offers a climate resilient living environment. The main research question is: how can Hod HaSharon become a climate resilient city? My goal is to find the right balance of the various urban layers, while concomitantly creating a sustainable, healthy and attractive city for people and animals.

In this report I first give an overview of the context of the site location. Then I explain several challenges in the area. This will be followed by the strategy, which shows how to answer and deal with the various issues. Finally, I illustrate my design interventions with three zoom-ins of different areas in the city.

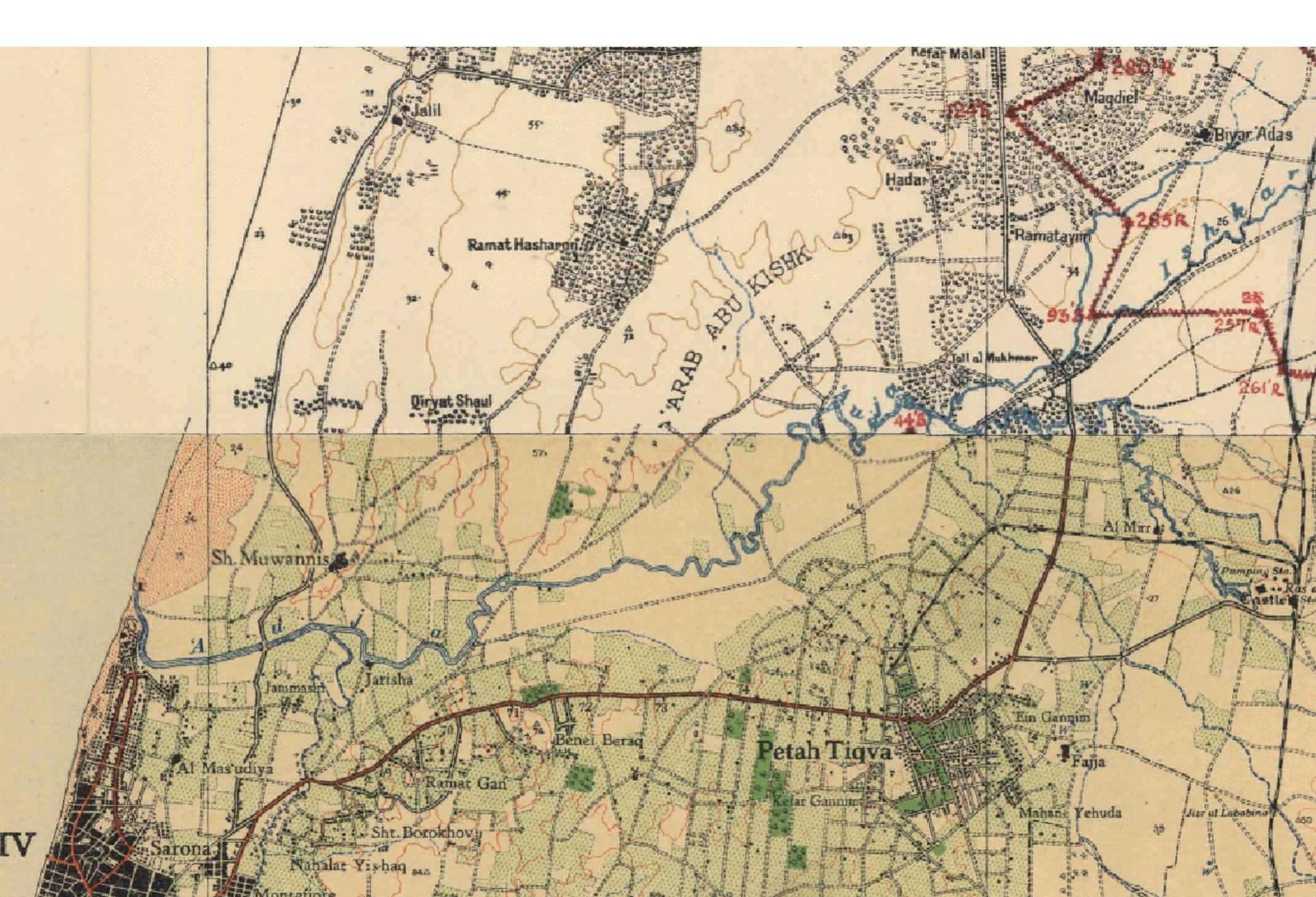

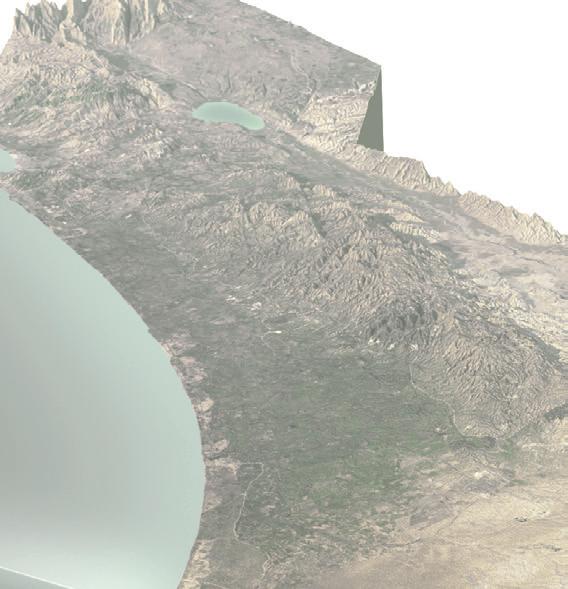

The site I chose for my project is the city of Hod HaSharon, situated in the center of Israel. Hod HaSharon is located in the Sharon region and is part of the metropolitan area of Tel Aviv. This region is situated along the country’s Mediterranean coastline. The cities that are part of Tel Aviv’s metropolitan area are the most populated cities in Israel. Today, 45% of Israel’s population lives there. It is also the main commercial, industrial and touristic center of the country. In 1947, the population of the metropolitan area of Tel Aviv was about half a million residents. Today its population is estimated at about 4 million inhabitants. Tel Aviv being one of the most popular and expensive cities in Israel attracts many people to move to its surrounded cities. Consequently the real estate value increases rapidly. This phenomenon also occurs in Hod HaSharon. In recent years Hod HaSharon’s population has risen increasingly. The ongoing need for houses plays an important role on

the city’s development. Currently, the many open spaces in the urban zone attract wealthy developers whose aim is to make more money by building in this open landscape.

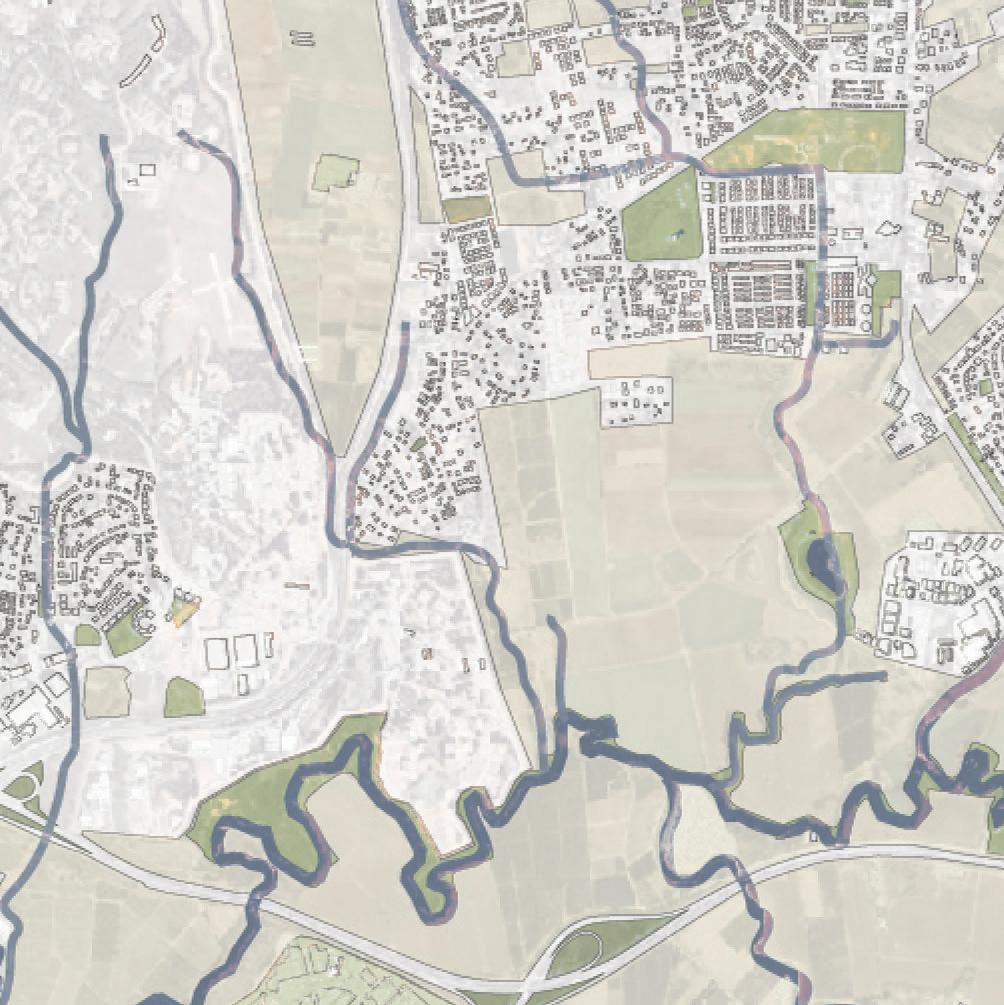

In the southern area under Hod HaSharon the river Yarkon is situated, which is the second largest river in Israel. The Yarkon begins near Rosh HaAyin, flows through Tel Aviv and ends up in the Mediterranean sea. The river forms a wet valley and it is the lowest point in the landscape. Its water basin is 900km2. The Yarkon accommodates a rich ecological system and a unique wet habitat. The river is surrounded by cities and many agricultural fields.

In the next chapter I focus on the area around the Yarkon and specifically show the situation in Hod HaSharon.

Coastal Plain

Tel Aviv, 1935

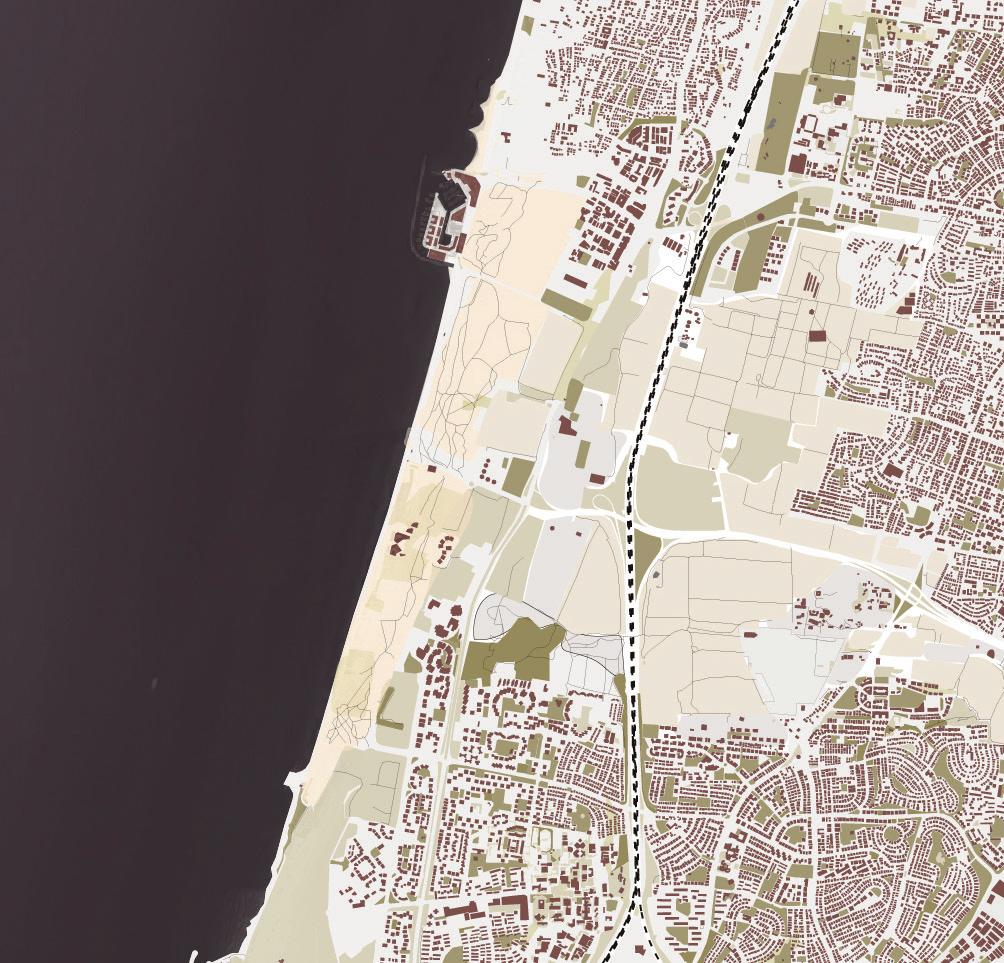

Tel Aviv, 2022

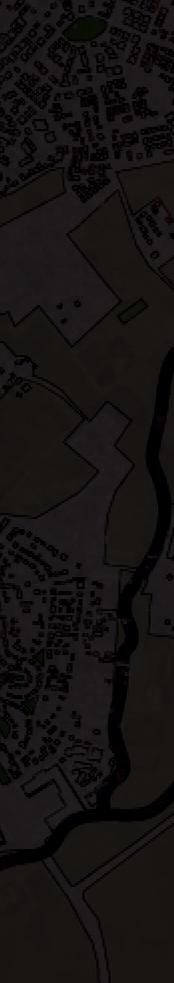

Tel Aviv, 1935

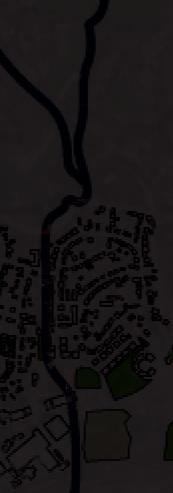

Tel Aviv, 2022

Hard landscapes

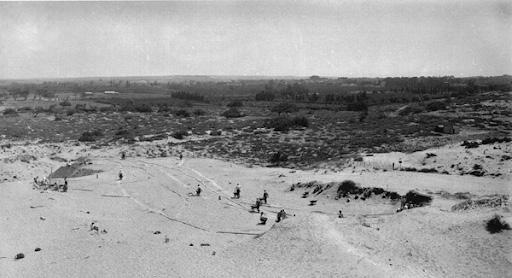

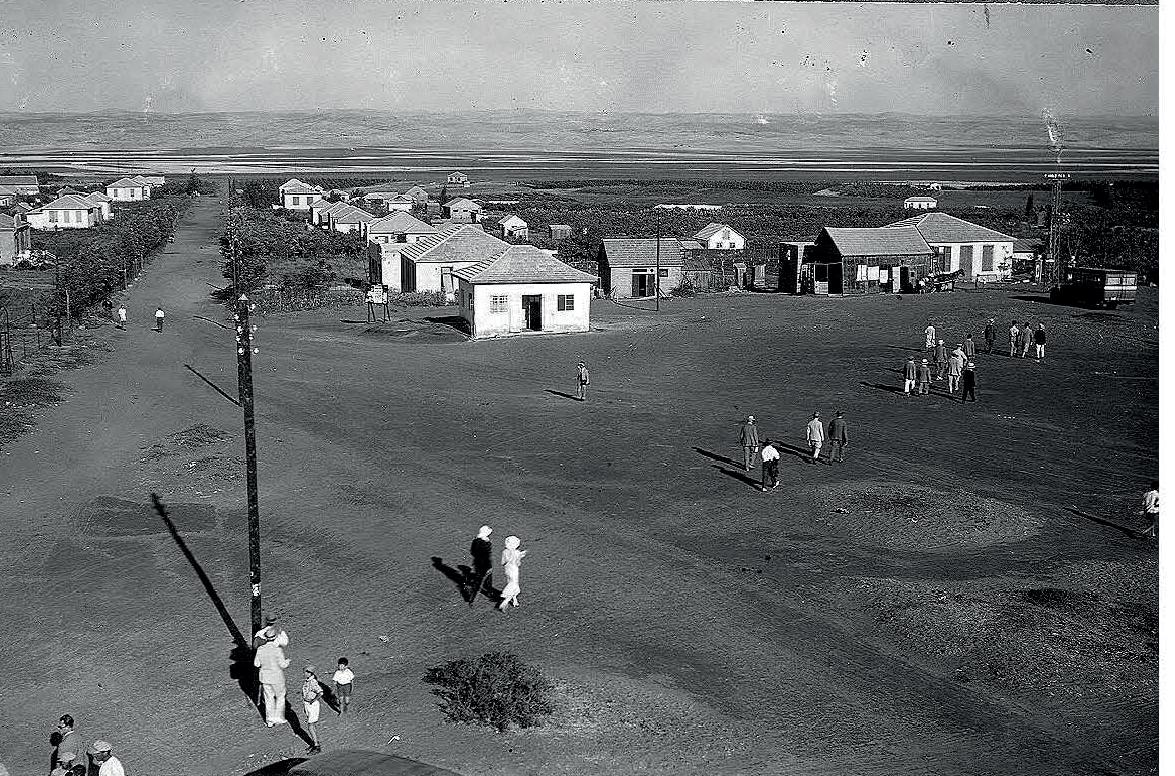

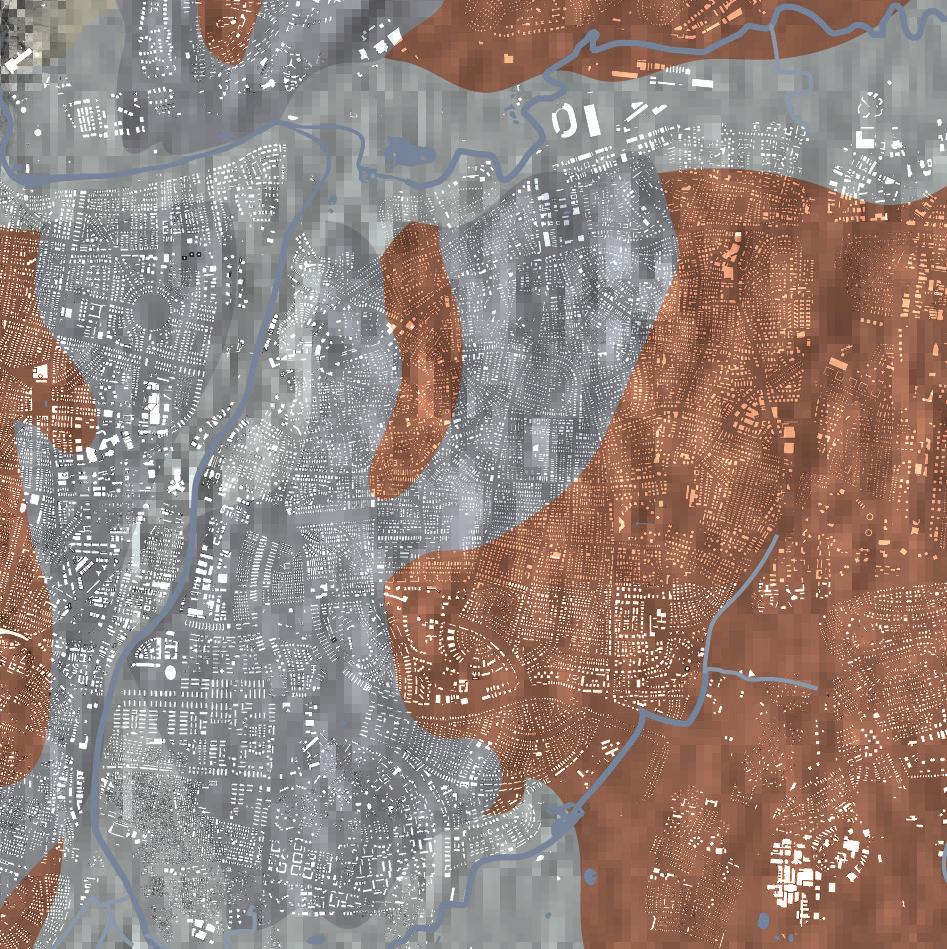

In the beginning of the 20th century, when Jewish people settled in the area of Tel Aviv, they were surprised to see mainly open, bare and uncultivated landscapes. In the first period of Jewish colonialization in the area, agriculture was the main income. Orange groves were especially successful. Throughout the years, agriculture became less profitable and less attractive.

After the Second World War the need for housing was enormous, which stimulated the urbanization processes. Historical maps of the area around Tel Aviv show the presence of many orchards. In later years these have largely disappeared. Instead, houses and streets were built. This led to an increasing number of impervious surfaces and a decreasing number of natural

spaces. These impermeable hard landscapes, mostly coated with concrete and asphalt, cause several issues: they create urban heat islands and they warm the city; they increase the amount of urban runoff which often leads to urban floods; they do not allow rainwater to infiltrate the ground nor replenish the groundwater; and they pollute surface water bodies and harm marine life.

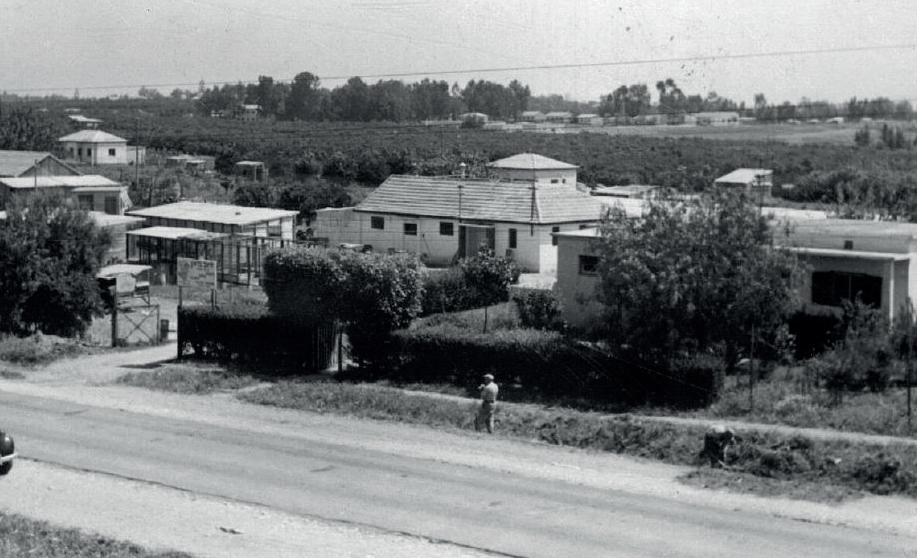

Before massive colonialization, 1935

Low density and orchards, Ramataim, Hod HaSharon

YARKON RIVER

Hod HaSharon

YARKON RIVER

Hod HaSharon

2022

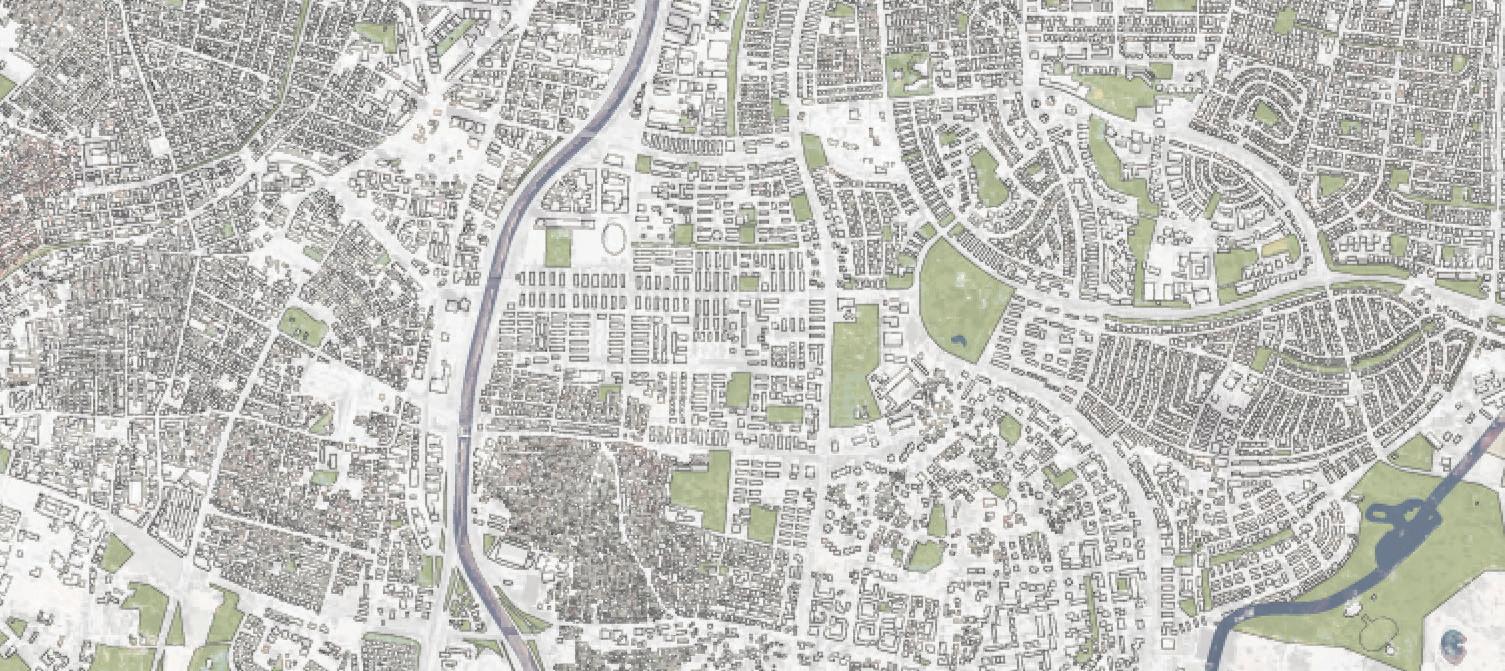

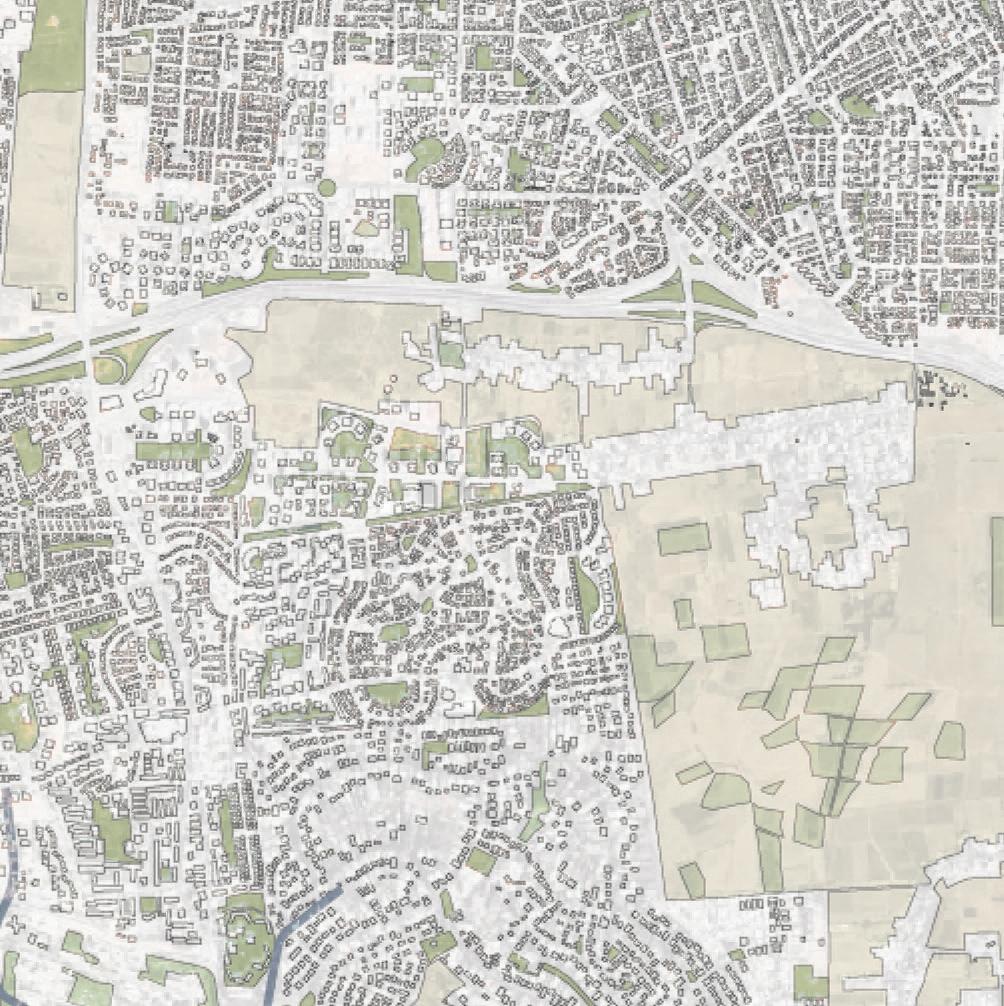

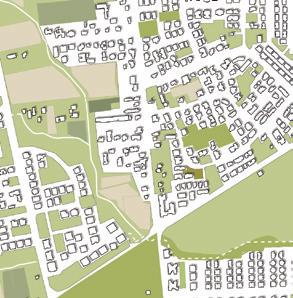

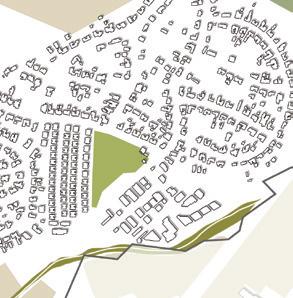

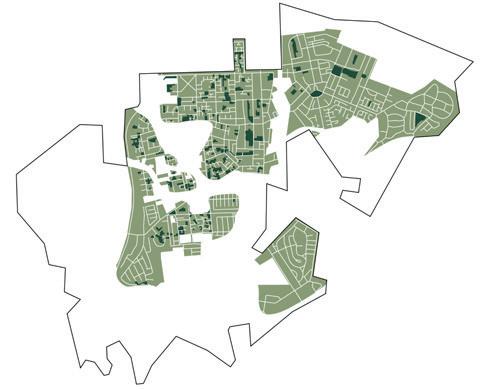

One city open spaces between buildings

Like other cities around Tel Aviv, the urban area of Hod HaSharon has grown significantly with impervious spaces such as roofs, roads, parking lots and paved sidewalks. However, the urban structure of Hod HaSharon has developed differently than other cities. Hod HaSharon is a formation of four villages that grew towards each other and became one city in 1990. As a result, the city has various open spaces in between its urban areas which can play a vital role in climate resilient urban planning. Yet, these open spaces are under pressure of developers who plan to build more houses and buildings. Today, there are 65,000 residents in Hod HaSharon. There are plans to build houses for another 35,000 residents in the coming fifteen years, which means the city will accommodate a total

of 100,000 residents in 2040. The municipality is currently working on these plans. I believe their plans do not leave enough space for green structures in the urban zone. It is precisely these open spaces that have an important role in current urban developments and therefore should be integrally designed. In contrast to the municipality’s plan, my goal is to develop and upgrade the open spaces, to utilize their value, and to create an integral design approach.

Dry landscape in Hod HaSharon (image: Shylee Ingar Berg)

Dry landscape in Hod HaSharon (image: Shylee Ingar Berg)

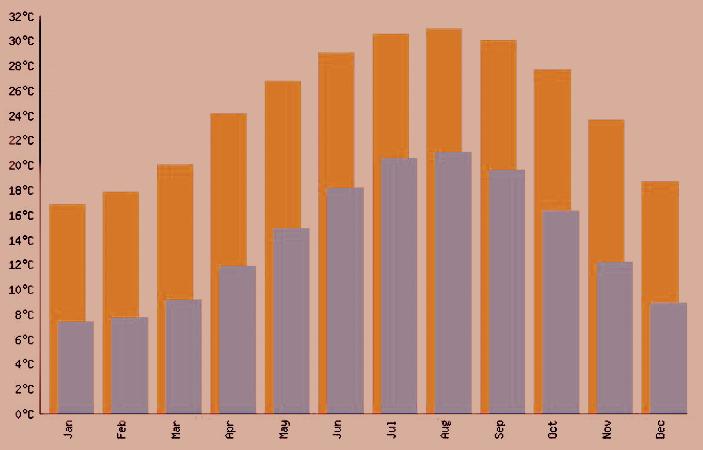

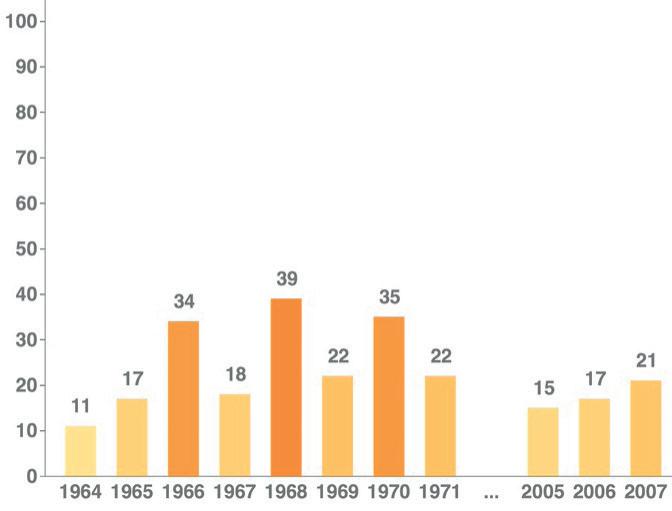

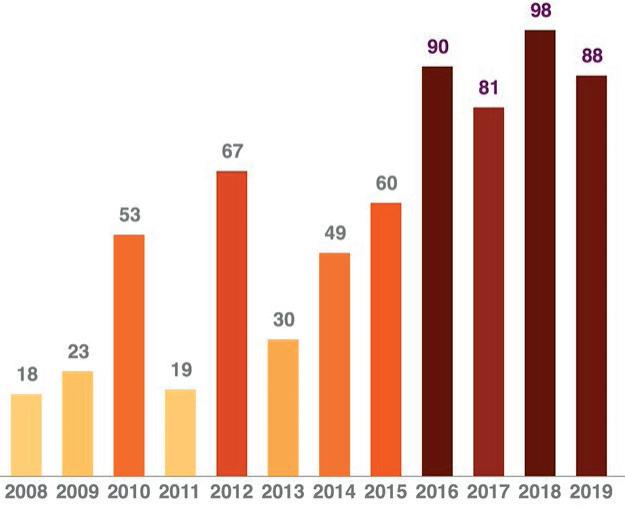

The metropolitan area of Tel Aviv has a Mediterranean climate, characterized by a long dry season, hot summers, and rainy winters. In summer the temperature in Hod HaSharon is more than 30 degrees Celsius, and between 15 and 20 degrees Celsius in the winter. From March until November it is usually very warm and dry. In the cities especially, the temperatures rise because the paved surfaces between the concrete buildings absorb the sun and create heat islands. Because of climate change and global warming it will be even warmer in the future. Not only has the number of warm

days increased immensely, also in the next 40 years researchers expect a temperature rise of 1,5 degrees. While large parts of Israel have already a desert landscape with on average 45 degrees Celsius in summers, researchers estimate that soon also the center of Israel will become a desert landscape. So, how can Hod HaSharon stay a nice and suitable place to live in with these expectations? I believe the urban landscape should be designed in such a way that supports the city in warm and dry days.

Average max/min temperatures in Hod HaSharon

Temperature rise of an average of 1,5 degrees in the future

Amount of days with more than 30° Celsius in a year

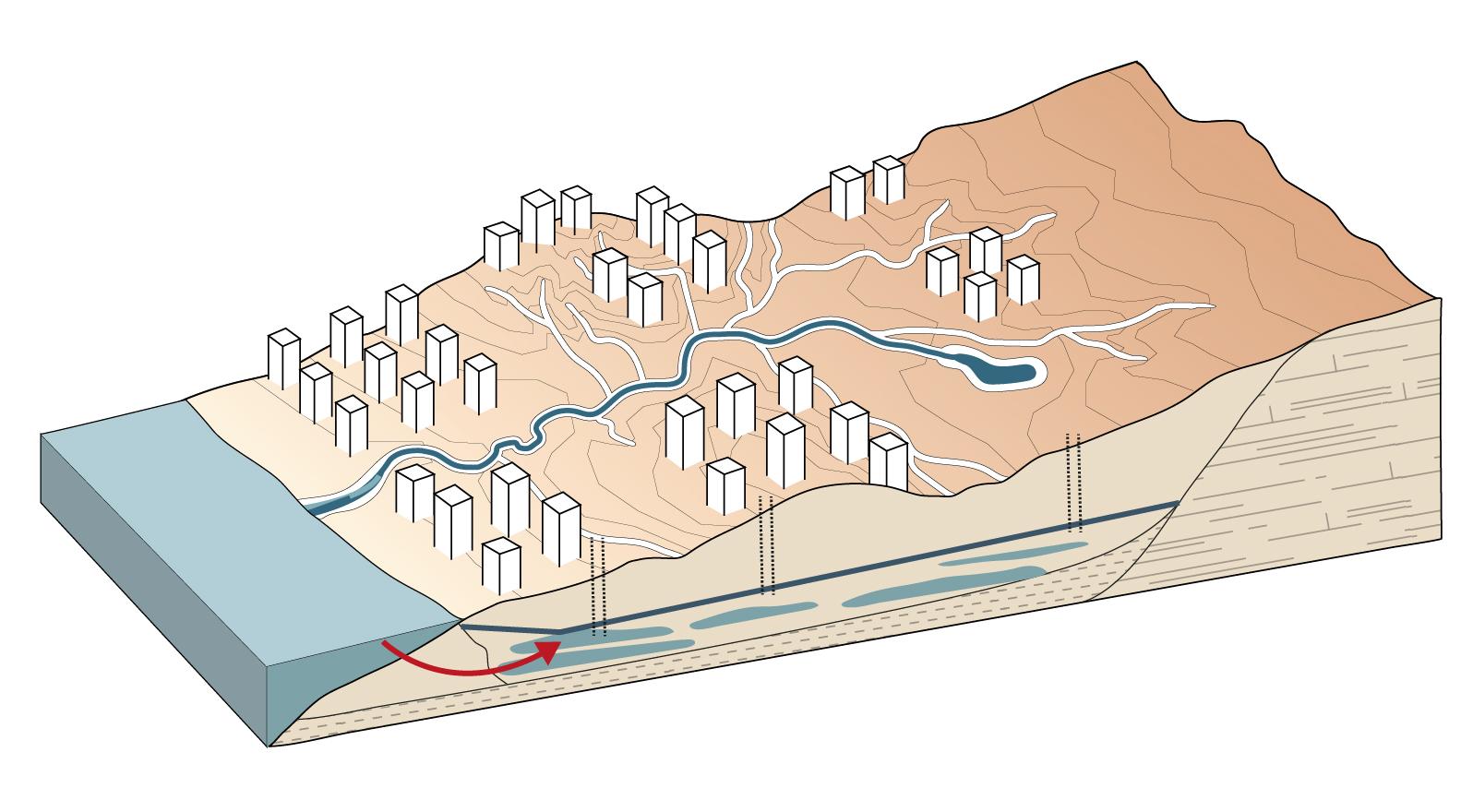

In general, Israel is a well-developed country in regard to irrigation systems and desalination technologies for drinking water. On the other hand, it is less developed in the field of sustainable drainage water systems. For many years, cities use pipe-based conventional drainage systems, which get rid of stormwater runoff very quickly and discharge it in streams, rivers and the sea. Since cities have a large number of impermeable surfaces and use traditional drainage systems, they cause several water issues: they increase the risk of floods; they reduce groundwater infiltration and lower groundwater recharge; and they cause deterioration of water quality in rivers and the sea, which

damages their ecosystem. In my project I address these three water problems.

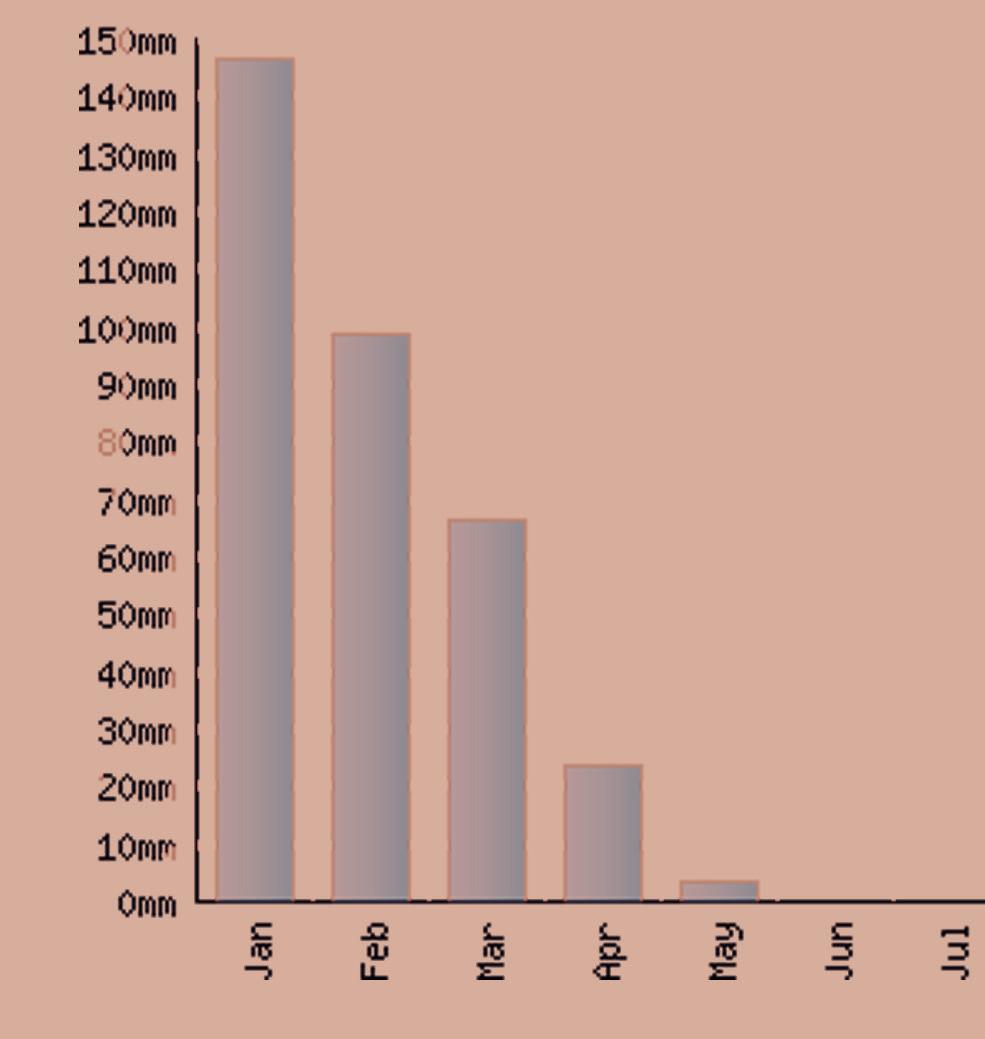

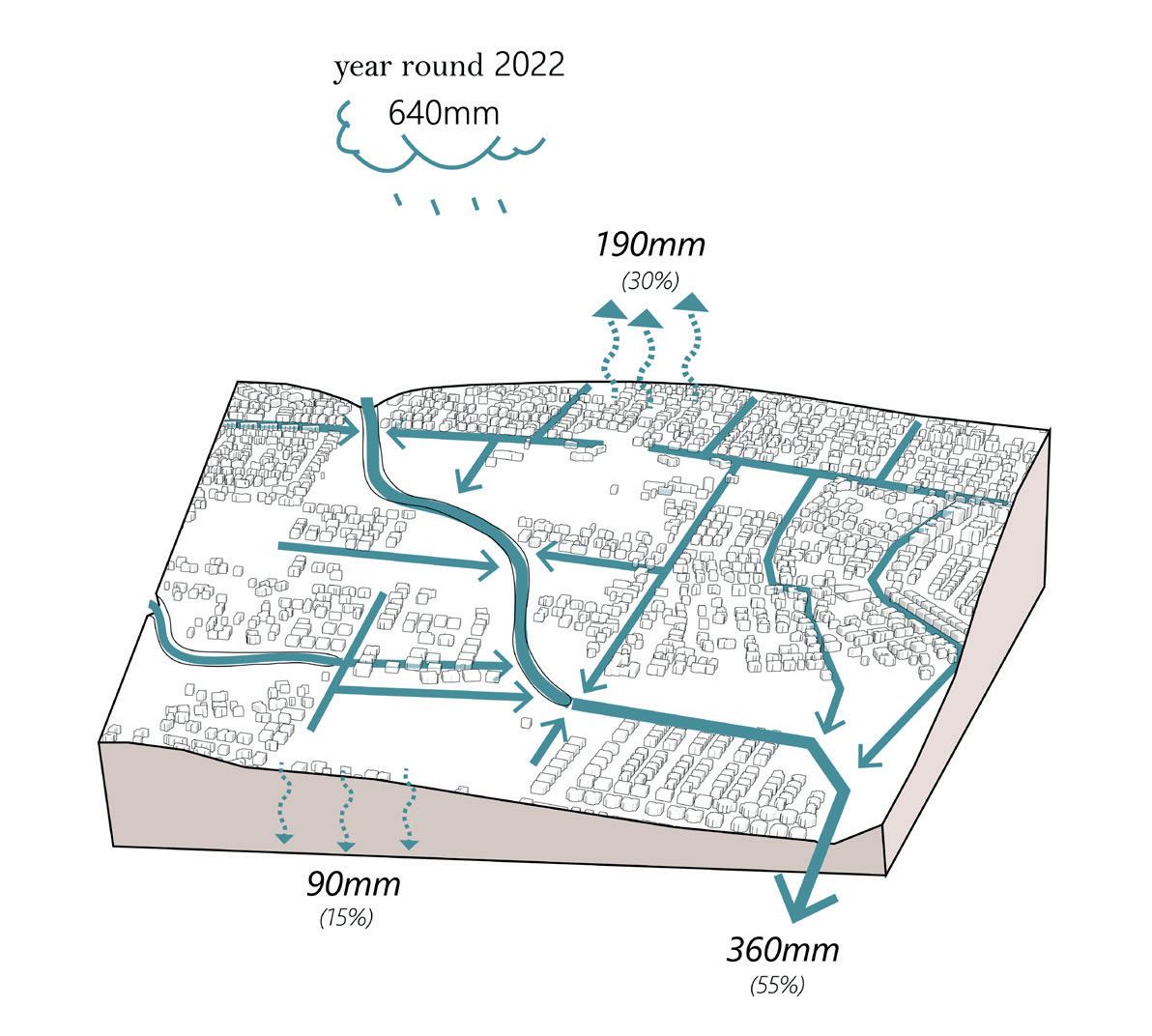

While there are not many rainy days in Hod HaSharon, the few rain day each year are extreme. Most of the rain events occur in the winter between November and March. The annual precipitation on average is 640mm. In recent years, due to dramatic climate changes, we experience more often short events of heavy rainfall and cloud bursts. The predictions for the future are more events of heavy rainfall and less precipitation all-year round.

Floods in the metropolitan area of Tel Aviv around the Yarkon

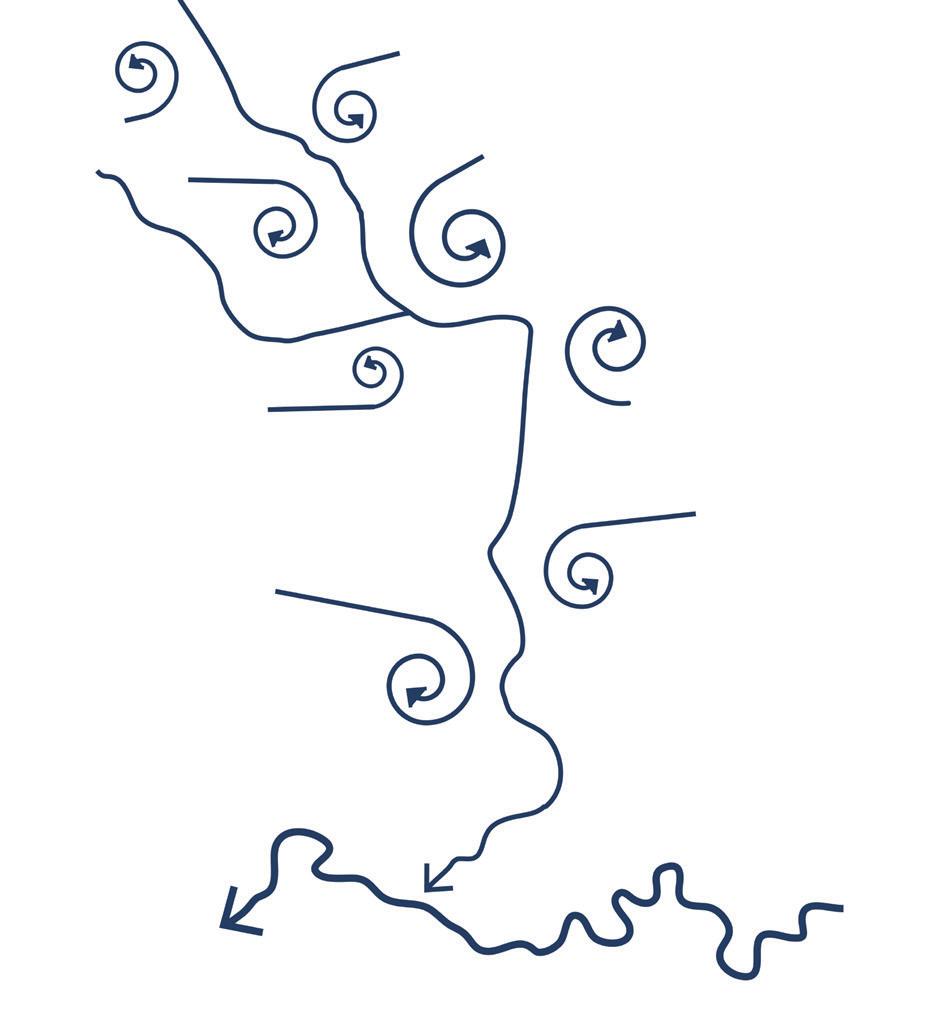

The result of the combination of heavy rainfall together with traditional drainage systems and the large number of hard surfaces is urban floods. In the metropolitan area of Tel Aviv stormwater drainage systems flow naturally into the Yarkon River and the Mediterranean sea. Along the Yarkon are several stream branches that drain rainwater from the cities and the higher landscape to the river. These streams are dry in summers and get wet during rain events in winter. In past winters, during heavy rainfall events, this drainage system was under water pressure and over-

burdens its capacity and the river, the streams and neighborhoods were flooded. These floods paralyze streets and neighborhoods, roads are getting blocked, and houses are flooded. The floods are not only dangerous, they also cause a lot of damage.

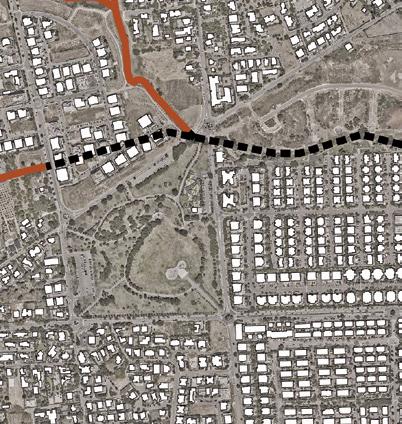

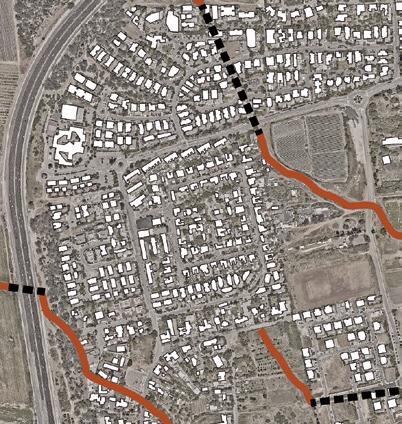

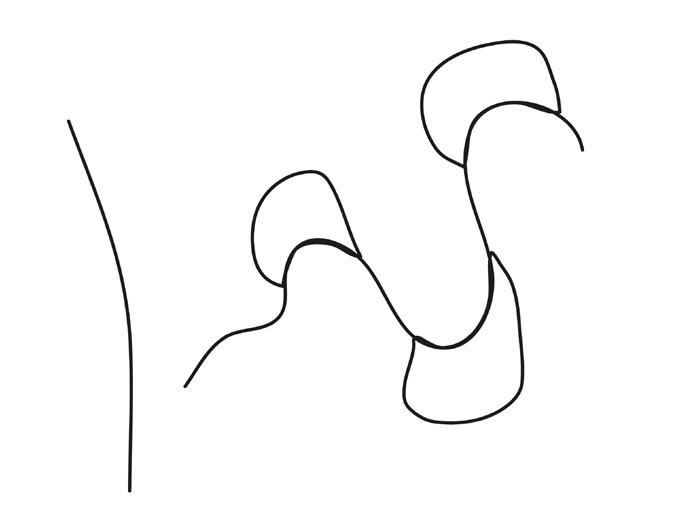

One of the stream branches along Yarkon is called Hadar, which goes through the urban area of Hod HaSharon. Also Hod HaSharon has been managing drainage stormwater by flushing it out. In the city stormwater runoff follows the topography, from the high point

to the lower point. Hadar stream is the lowest point and drains runoff from its water basin. Technologic developments from the twentieth century resulted in the transformation of the ways stormwater management system was maintained. In the past, Hadar used to be a continuously open meander stream. Today, several points are no longer open and have become closed tunnels with underground concrete pipes. Several neighborhoods were built on top of the tunnels that drain Hadar’s water and have interfered with the natural drainage system. These changes, together with the growth of sealed built areas, cause increasing rates of surface runoff. In recent years during heavy rainfalls several neighborhoods in the city, mainly along or above Hadar, have experienced flooding events. People even had

to be rescued from their vehicles. These floods show that the traditional rainwater drainage systems are no longer able to withstand the huge water flow during winter times. Trying to control stormwater runoff in such an unsustainable way apparently fails during intense rainfalls. This water system is not flexible to adapt to the extreme conditions of rain events.

I believe that managing stormwater should be more sustainable. The urban landscape can control the balance of urban runoff. More space for water retention should be given in the urban area. This can delay and hold stormwater runoff and prevent it from flowing at once towards the river.

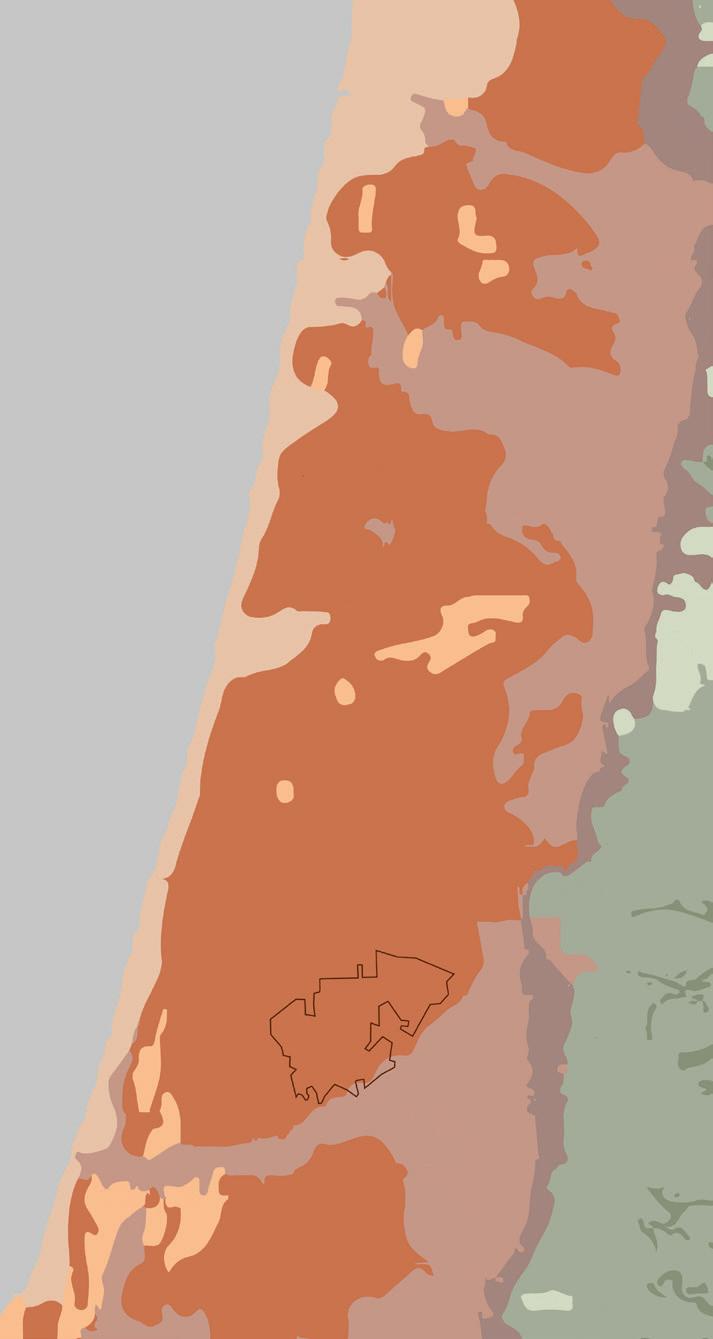

Under the coastal plain zone of Israel exists a large freshwater resource, the Aquifer of the Coastal Plain. This natural reservoir is one of the most important water sources of the country. In recent years its volume and quality have been deteriorated. Changes in the land use and soil quality have reduced the amount of rainwater infiltration and led to a low groundwater level.

Rainwater is the main source of the aquifer. In cities most of the rain falls on impermeable surfaces and is being drained into streams

or directly into the sea through urban drainage systems. This causes the loss of millions of cubic meters of freshwater per year. The coastal aquifer is in constant retreat from anthropogenic pollution and from seawater intrusion. Due to its declining levels, the hydrological balance is disturbed, and seawater manages to penetrate the coastal aquifer irreversibly.

Another reason rainwater cannot easily infiltrate to the groundwater is the changes in the land use in the last decennia. As a result of

Red sand and loam (“Hamra”)

Calcareous sandstone (“ kurkar”)

Alluvium

Sand dunes

Terra-rossa

the massive colonialization in the Sharon region after the Second World War, many areas were transformed into intensive agricultural fields with irrigation systems. Consequently, the soil has changed its formation, was over exploited, and its quality has been deteriorated. The ‘Hamra’ soils in the Sharon region have been affected and in many areas the top layer of the soil became very thick and barely permeable. The name of this layer is ‘Nazaz’. I have tested the soil of Hod HaSharon and concluded that water was not able to infiltrate the ground. When I mixed the soil with water it became thick and sticky.

While Israel develops seawater desalinization technologies to secure drinking water in the future, these systems are unsustainable, they use a lot of energy, and they are expensive. We should therefore find sustainable ways to restore and replenish the aquifer by infiltrating as much rainwater as possible. Thus, one of the goals in my project is to improve and restore the soil in order to be more permeable and fertile. Moreover, I aim to give more space for natural rainwater infiltration. The current urban drainage water system is wasting rainwater by discharging it into the sea. I suggest to hold rainwater runoff, to let it infiltrate naturally, and to store it in the aquifer.

Water of Hadar stream is black in December

Water of Hadar stream is clean in April

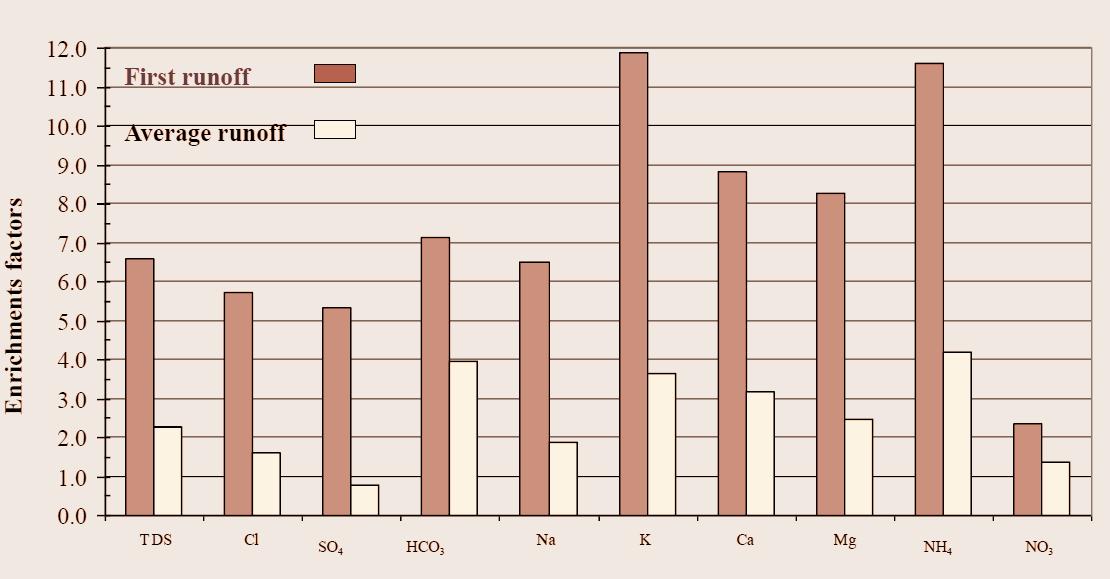

Stormwater runoff in urban areas is at a high risk of contamination. Human activities in urban areas create oil and fuel deposits, heavy metals, organic toxins and bacteria. In cities, roads are the main contributors to water pollution and are usually the lowest point in the urban structure. The contaminated runoff is drained into natural bodies of water, such as rivers and the sea, and harms their ecosystems. During the dry season, the city streets and the drainage systems accumulate large amounts of dust, oils, fuels, animal excrement and garbage. When

the very first stormwater runoff (‘First Flash’) reaches the sea it paints the water black. This First Flash brings many pollutants from the city to the sea, which endangers public health and disturbs the sustainability of the marine environment. The polluted water also flows into the Yarkon river and harms its unique ecological system. This causes the death and disappearance of sensitive animals and vegetation, and damages the diversity of species. One of my goals is to clean this polluted runoff before it reaches natural bodies of water.

Polluted runoff harms sensitive and unique ecosystem and lowers diversity of species along the Yarkon

First runoff with high concentration of pollutants

Sea is colored black

Roads are the lowest point in the urban structure and during the first rain events they become polluted streams

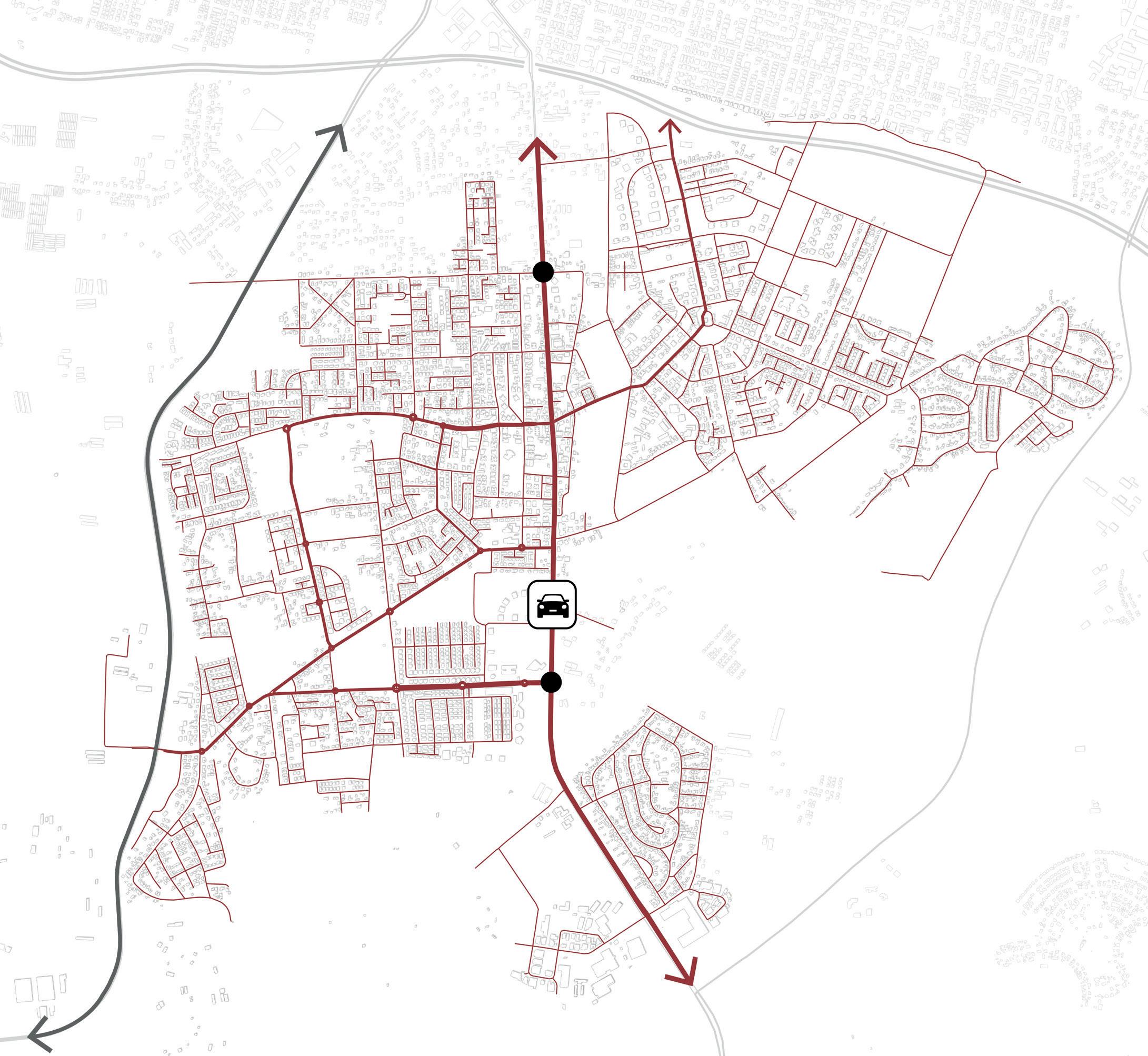

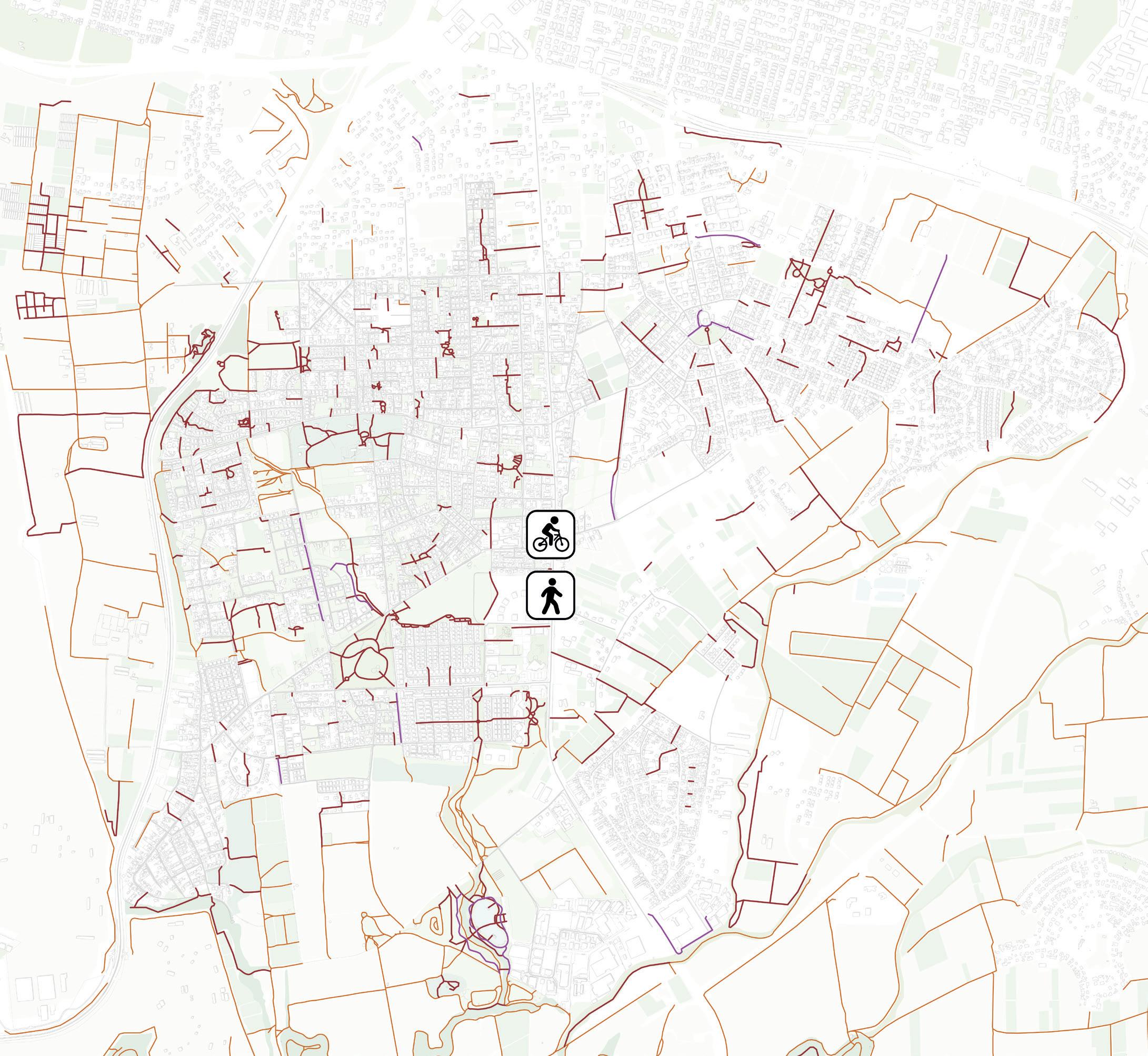

The mentality of Hod HaSharon’s residents is to commute by car. The main city infrastructure is based on roads. These asphalt surfaces take a lot of space in the streets, they make the city warmer, they pollute, and they are unattractive. Public transportation is limited and slow routes are scarce. There are few bicycle paths and the network is fragmented. When I visited Hod HaSharon I had to bike most of the time on the pedestrian sidewalks or on roads. Both are inconvenient and dangerous. While people barely bike, there is a trend amongst young people who cycle on electric bikes.

During the winter, when I visited the landscape around the Yarkon I got stuck in the dirt paths that became muddy. Later I understood that people either avoid to visit this area by bike after it rained or they arrive by car.

I believe the city should provide more alternatives for mobility, including slow routes network for bicycles and pedestrians. An interconnected network of slow routes should not only be functional but it could provide recreational uses too. Moreover, the existing dirt paths should be improved.

Bike paths

Walking paths

Dirt paths

Slow routes are scarce and fragmented

In order to give an answer to the research question how can Hod HaSharon become a climate resilient city and to the challenges I addressed in the last chapter, I developed a strategy. In this strategy I illustrate how to deal with the challenges using a landscape approach.

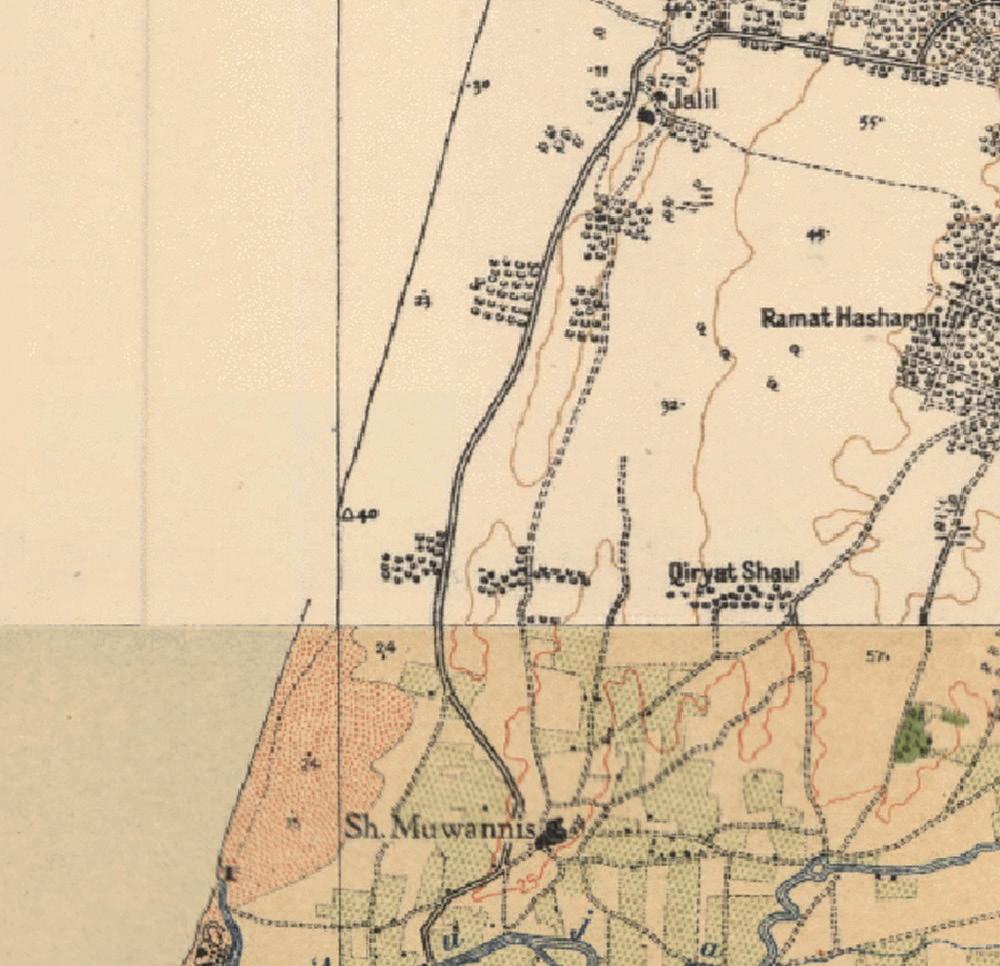

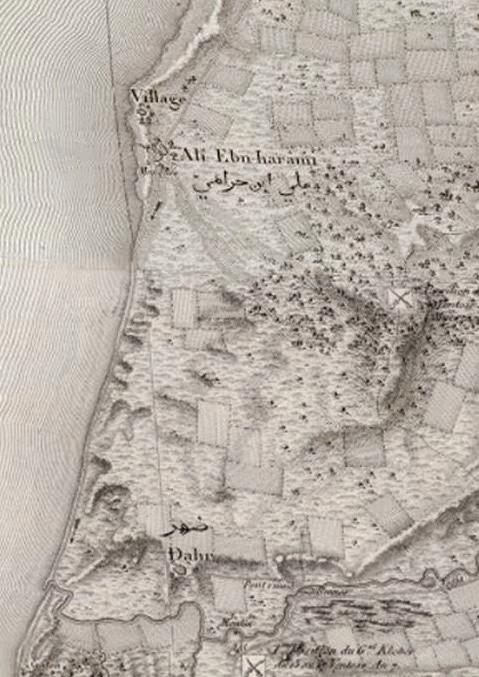

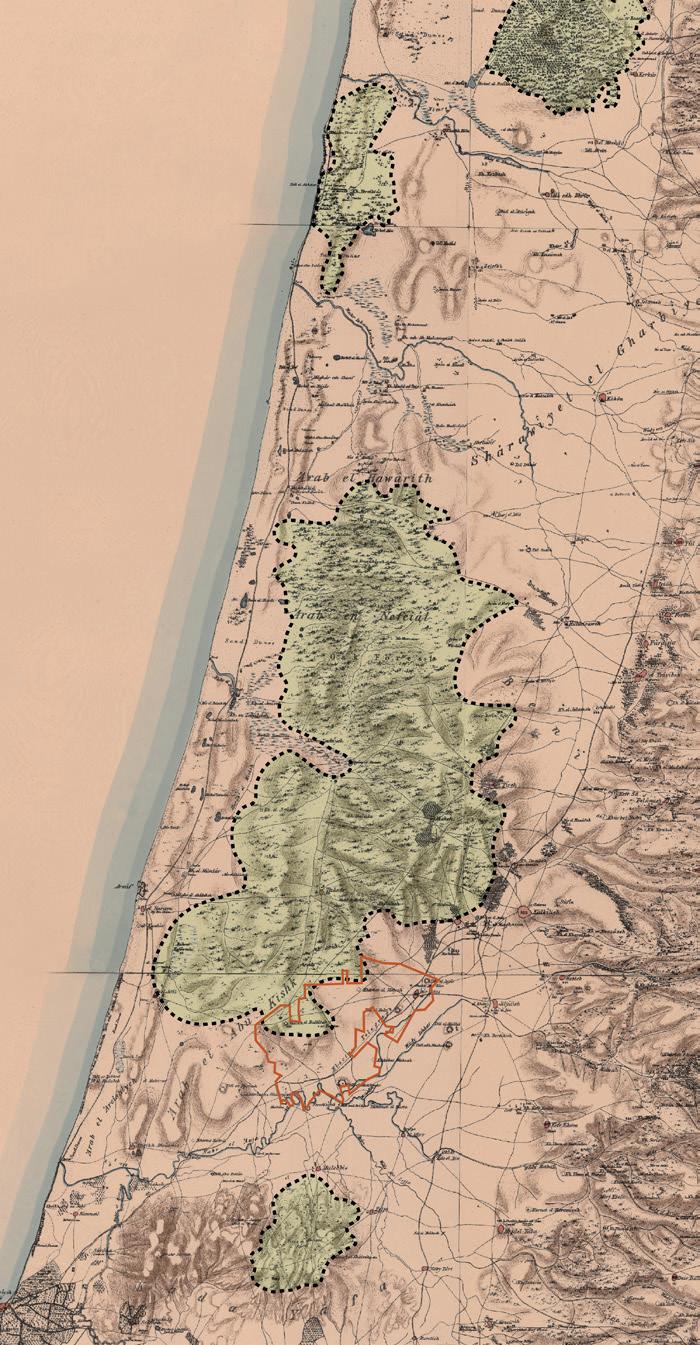

During my research, I discovered that in the past a large part of the Sharon region was a dense forest. This native forest grew in the Mediterranean climate and mainly on the ‘Hamra’ soils. Over time the forest was damaged by human activity, but was able to recover itself. When the Ottoman Empire ruled Israel in the nineteenth century many trees were taken down for wood production. During the first World War the need for wood for transportation was so immense that the forest was almost completely destroyed. This led to a massive ecological disaster. When the first Jewish people came to settle in Hod HaSharon they encountered a bare landscape.

Dendroarchaeological evidences indicate that the ancient forest in the Sharon region was dominated by the Quercus calliprinos and the Pistacia terebinthus subsp. Palaestina. After the early Arab period the population of both tree species was damaged to such an extent that is was taken over by the Quercus ithaburensis forest. Today you can barely see any of this forest in the Sharon region, and in the city of Hod HaSharon only four Quercus ithaburensis trees have survived.

The meaning of the city Hod HaSharon is ‘glory of the forest’, the name I gave to my project. The region’s name – Sharon – refers to the ancient forest, and the word ‘hod’ means glory in Hebrew.

Historical map, 1798

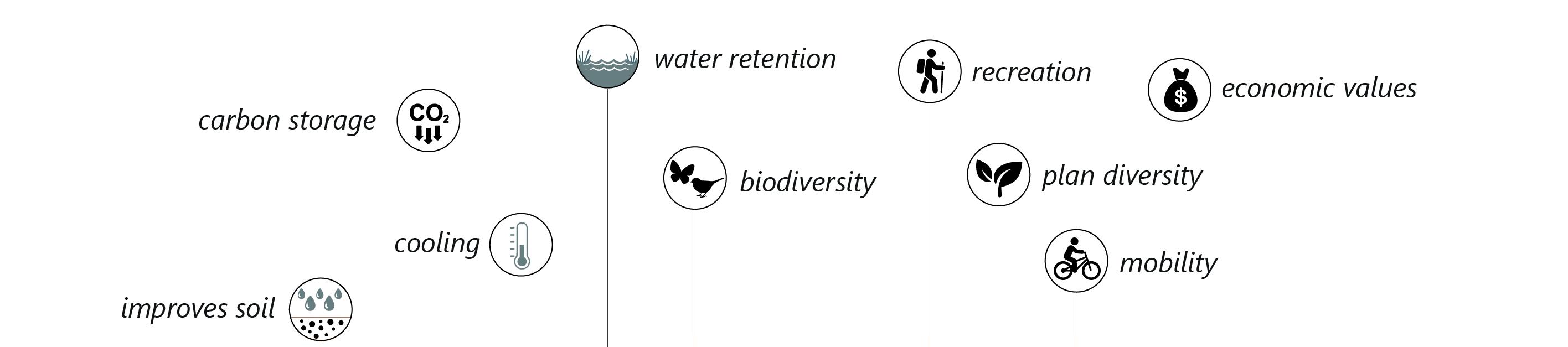

My idea is to bring the native forest back into the city. I believe that having a forest in Hod HaSharon is the only way to deal with the challenges from the previous chapters and to make the city climate resilient. The forest will not only protect the urban landscape from being built, but also offers numerous values and benefits to the city. The forest:

∙ cools the city in warm and dry days

∙ provides shadow and places to hide in warm days

∙ creates micro climate

∙ improves the soil fertility and permeability

∙ stores carbon emissions

∙ improves air quality

∙ improves urban ecology and increases plant diversity and biodiversity

∙ acts as a ‘sponge’ for water retention

∙ improves mental and physical health of residents

∙ provides attractive spaces for recreational use

∙ increases economic value of real estate

∙ attracts tourism

∙ improves the imago of the city

Hod HaSharon = Glory of the forest

Urban forest = climate resilient city

Values and benefits

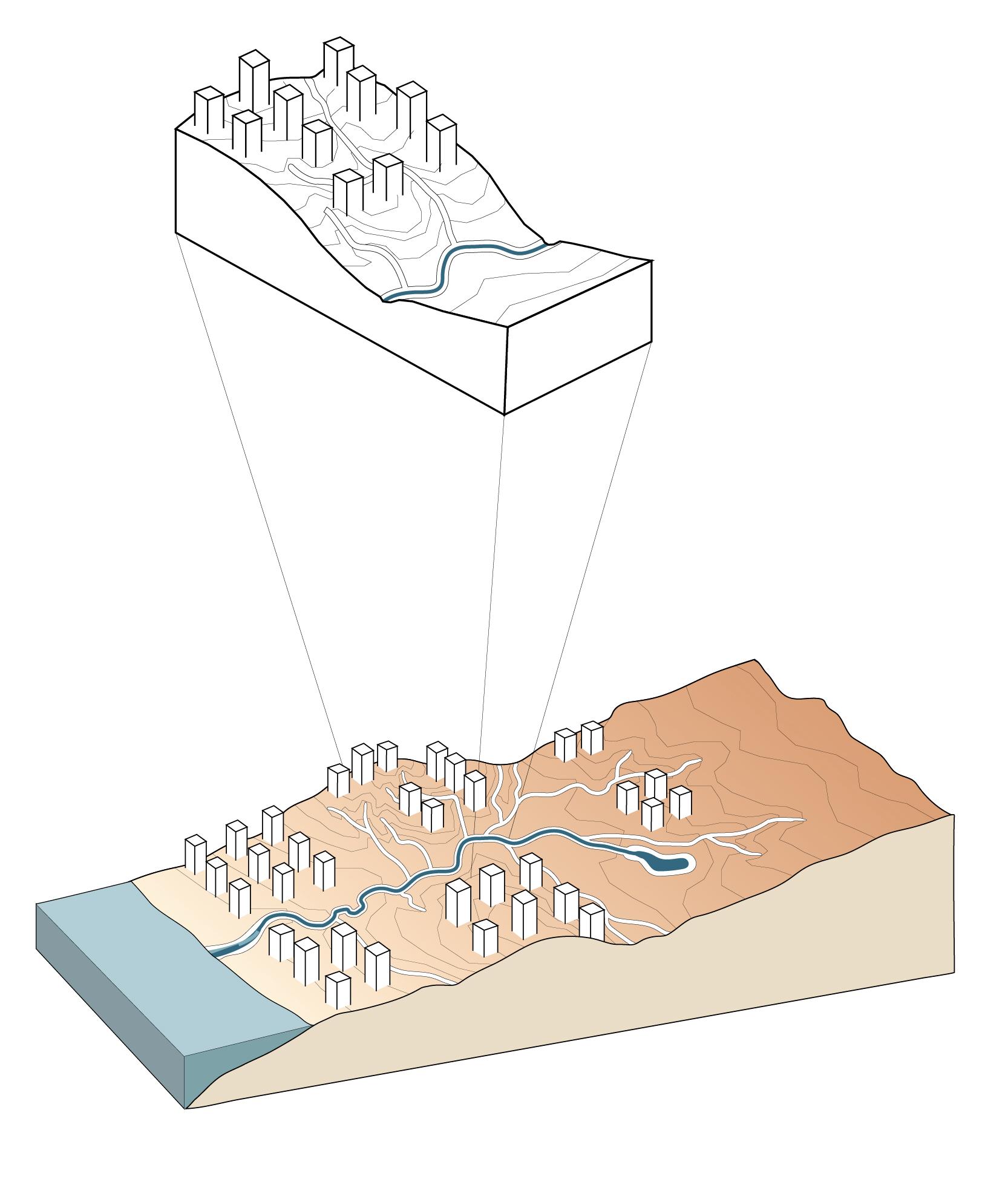

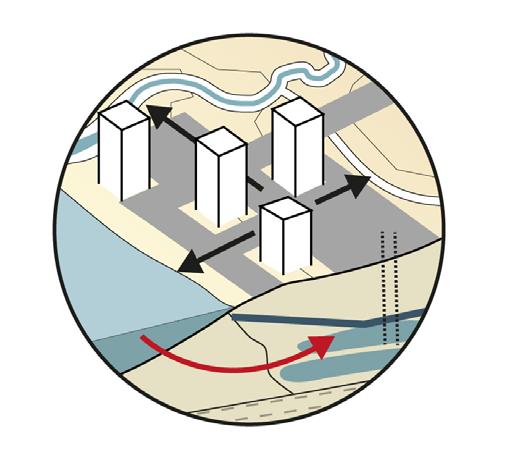

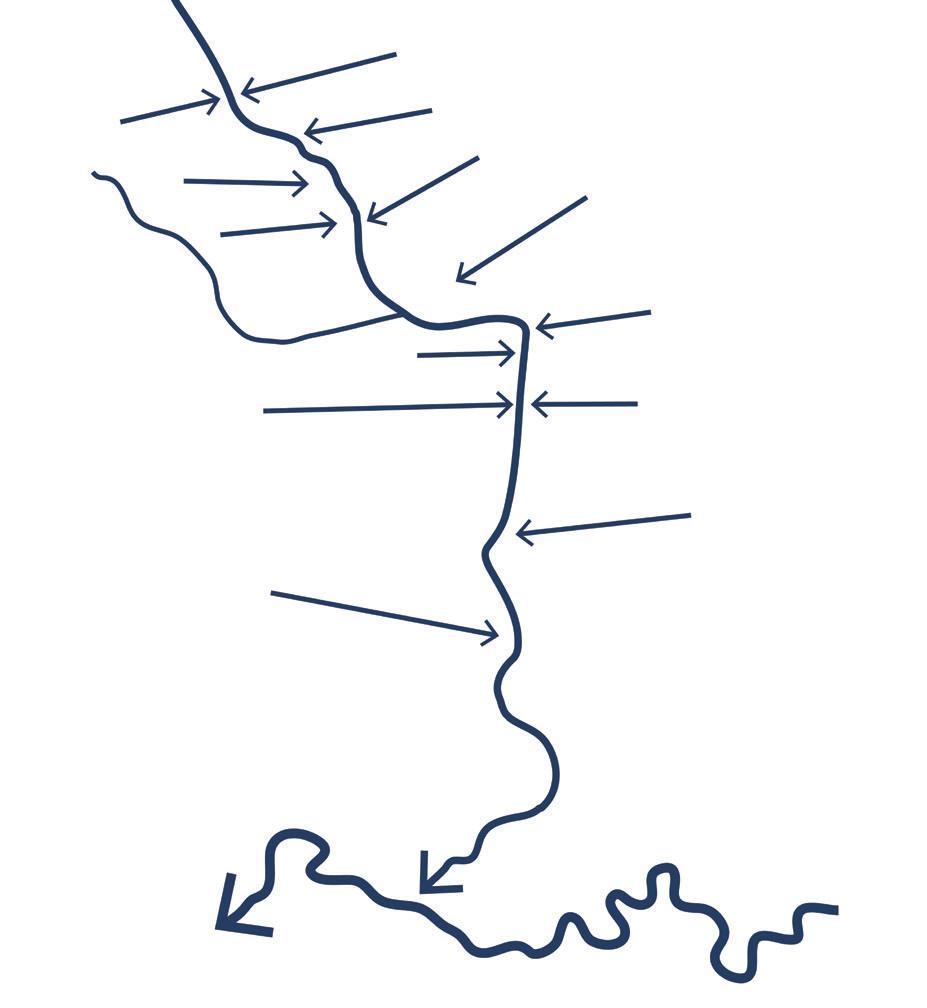

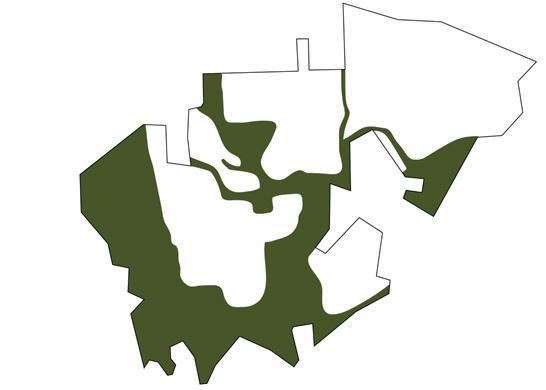

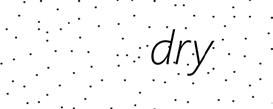

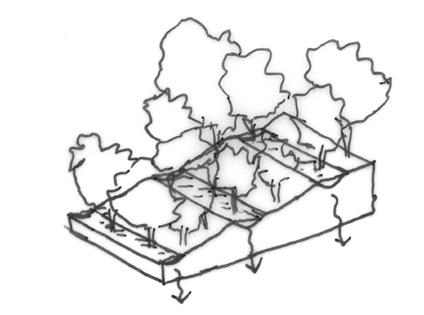

To deal with the drainage water issues I believe that the system should be climate adaptive and sustainable. We should approach it differently. Instead of draining runoff and trying to get rid of it as soon as possible, we should collect it, hold it, retain it, and infiltrate it (store it) in the ground. We should look at stormwater as asset and not hazard. The water system can create life. The idea is to capture the runoff in the higher grounds, in the city, before it arrives to the river.

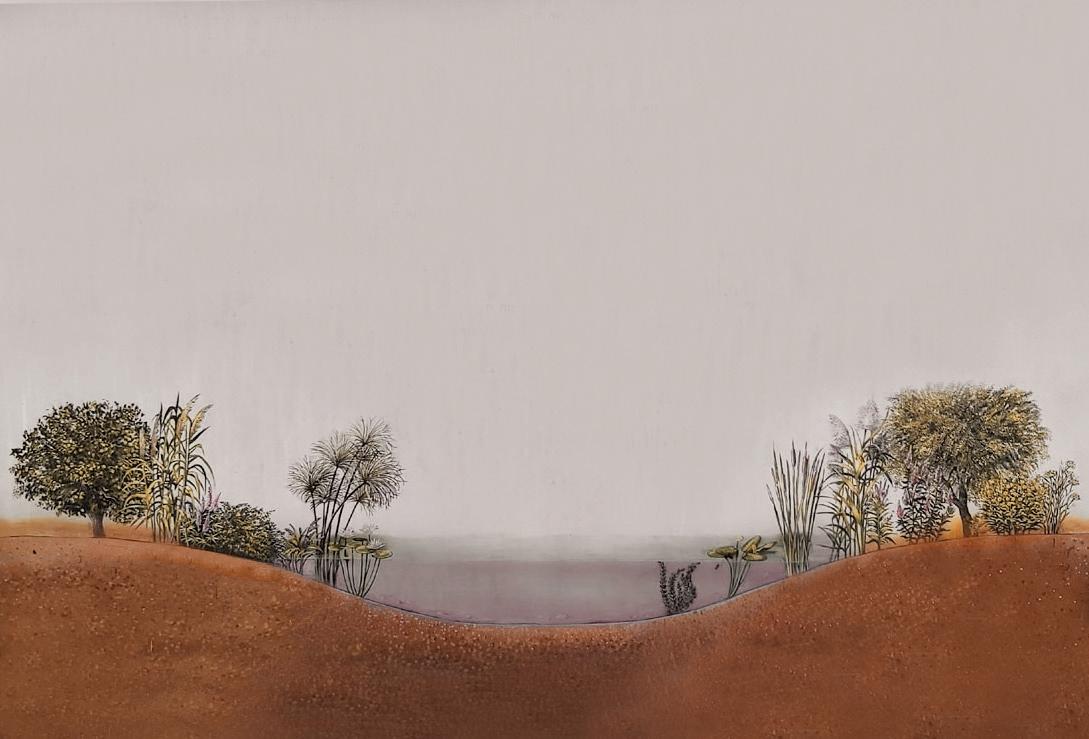

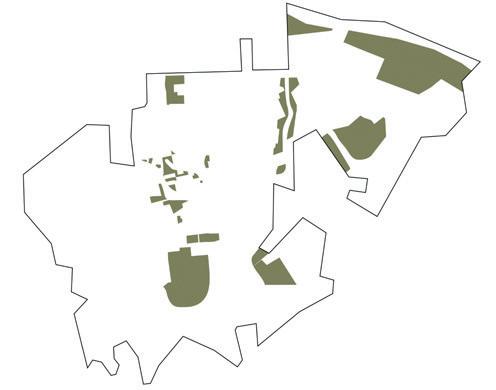

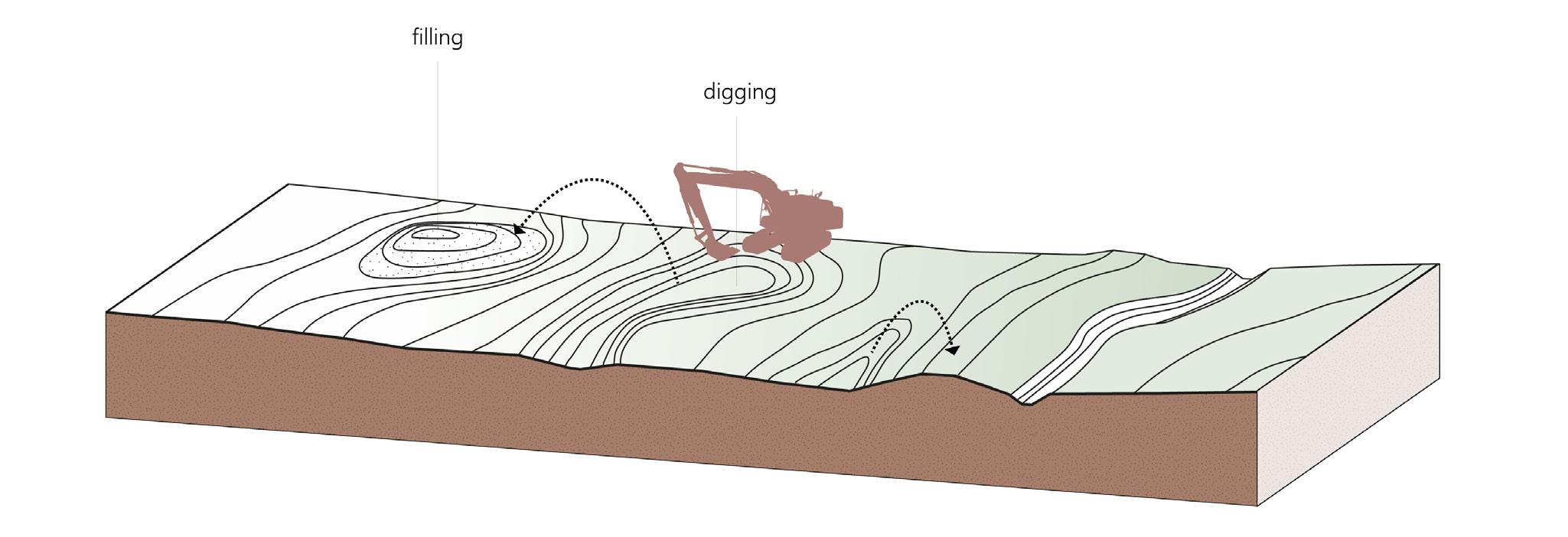

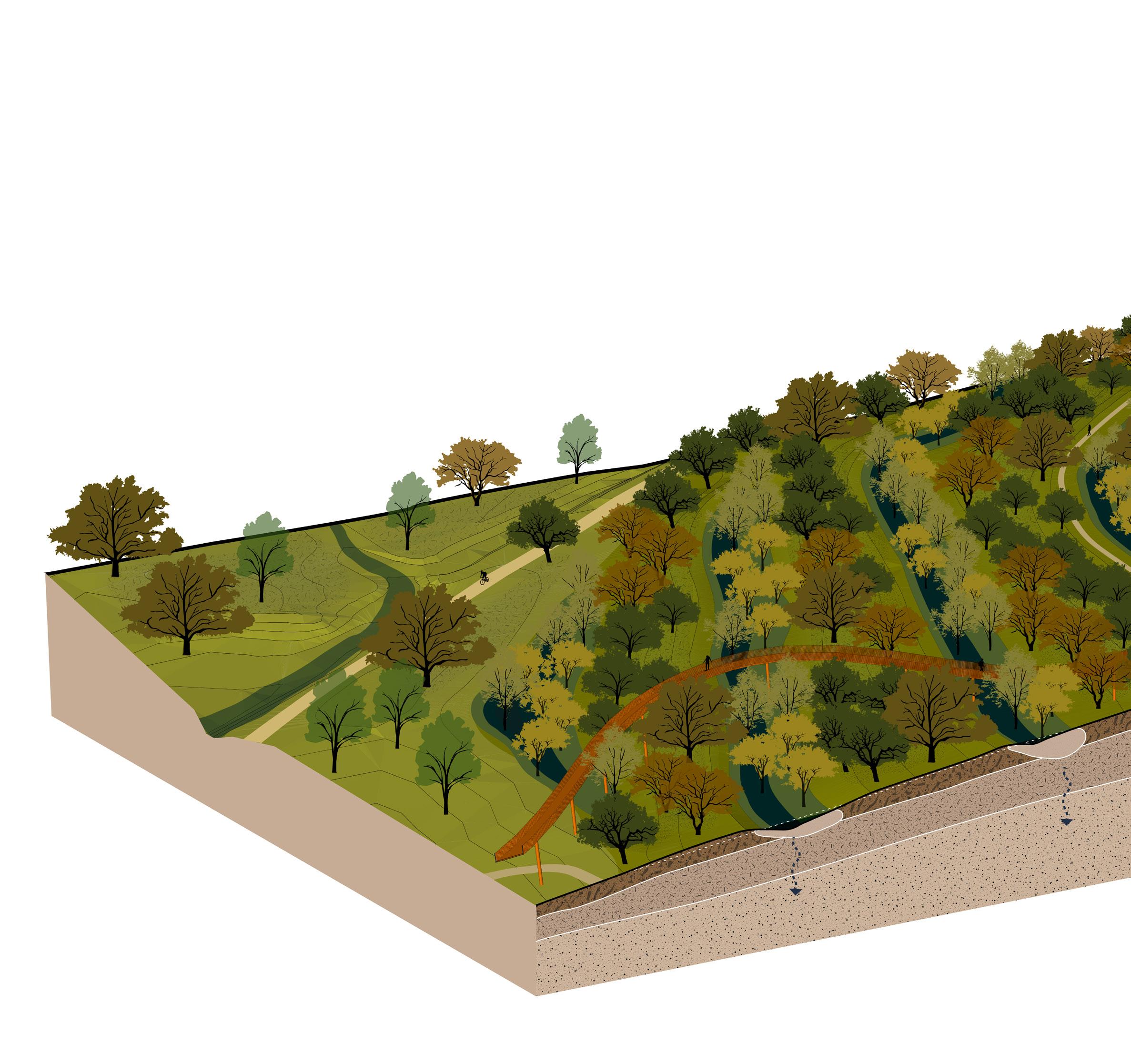

In my design the water system and the restoration of the forest are two integrated systems. In order to achieve the goals of a sustainable water system in the city, I make more space for water retention by creating gradients in the landscape. Digging in the soil and making barriers for the water holds the runoff. Removing and improving the top soil layer at these points allows rainwater to naturally infiltrate the ground. With the excavated soil, I create water barriers, dykes and hills for more plant diversity and a good soil balance. In the areas that become wet in winter, moderately wet forests can grow. In the dry areas, dry forest can grow.

agricultural field

orchard

abandoned agricultural field

wet habitat

forest

bushes and shrubs

forest area (army base)

park

non-native forest agricultural fields

former agricultural fields

uncultivated spaces

uncultivated spaces

orchards

park

non-native forest agricultural fields

former agricultural fields

uncultivated spaces

uncultivated spaces

orchards

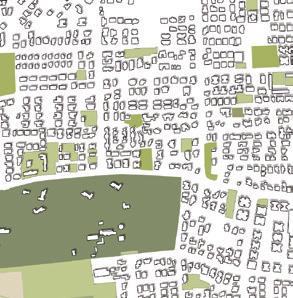

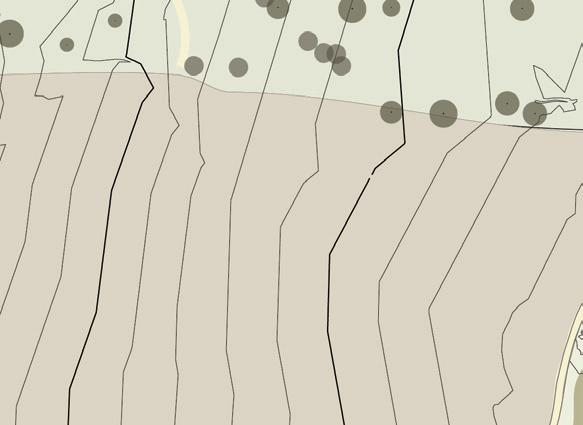

The current green structure of the city is like a fragmented mosaic. There are many different green types, including agriculture fields, uncultivated fields, invasive forests, parks. All these open spaces have no clear structure. My vision is to turn these open spaces into a forest with a clear structure. In this way Hod HaSharon will be turned into an oasis in a desert landscape. In

the master plan I distinguish four layers of the forest with different characters:

∙ Forest park

∙ Existing neighborhoods

∙ Streets

∙ New neighborhoods

Water and forest are integrated systems

New trees in the existing forest

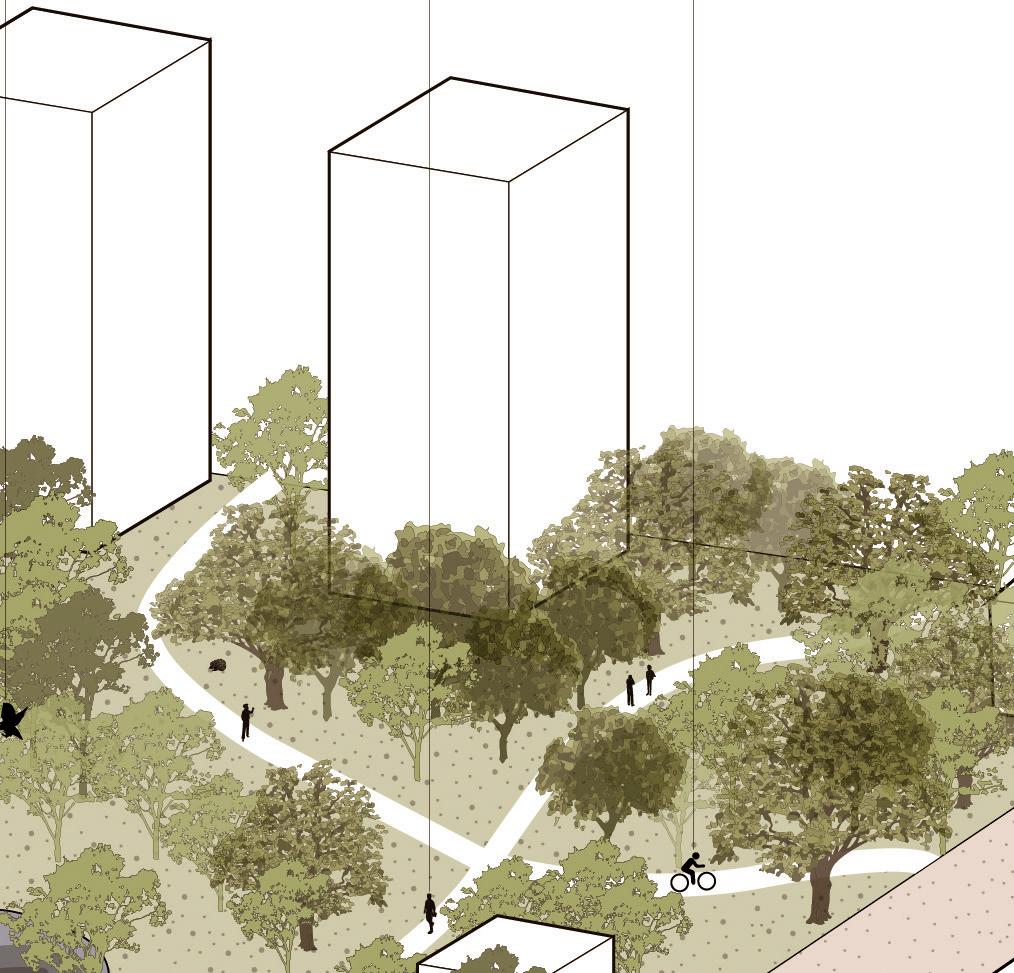

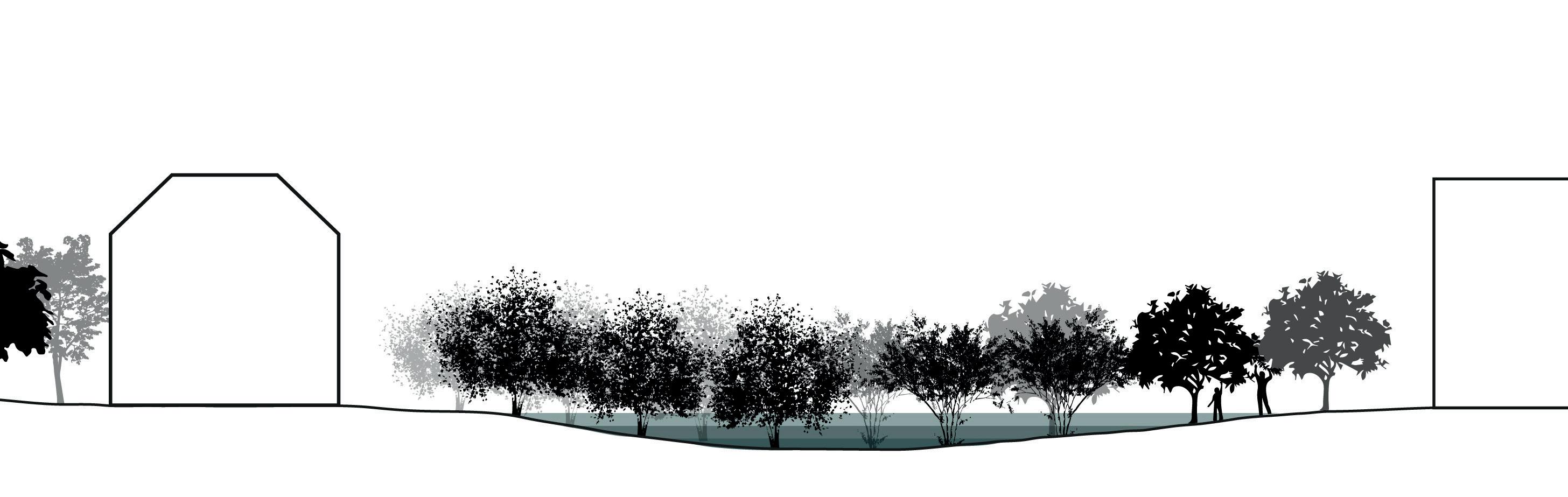

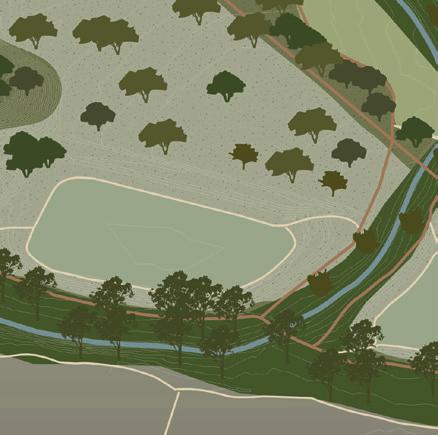

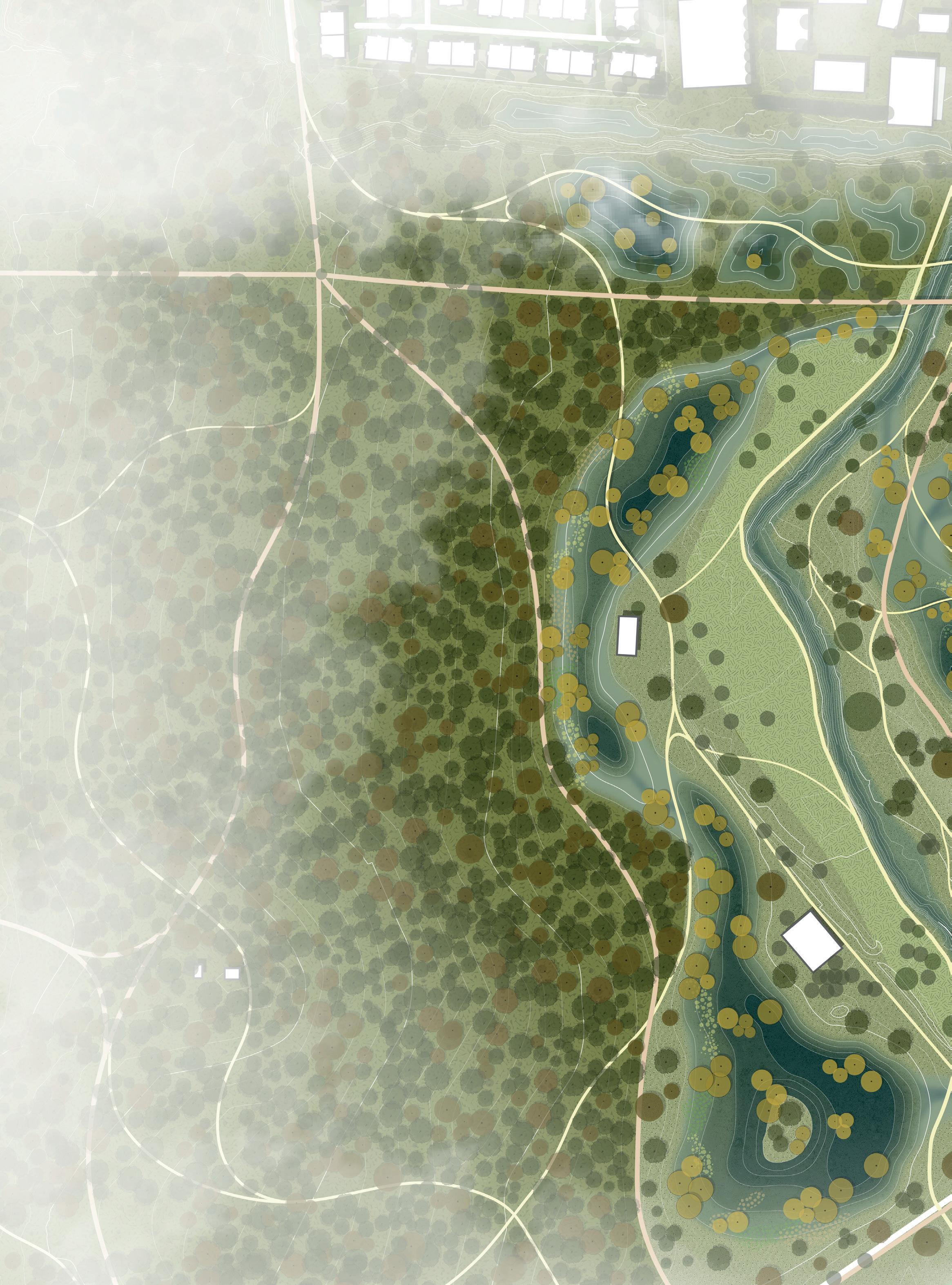

The forest park is a wild forest along Hadar stream with dry and moderately wet habitat. The forest park creates a continuous strong gesture with one identity that connects the open spaces along Hadar. Moreover, as an ecological corridor the forest park connects the city with its surrounding landscape. Along the forest park are three types of water systems that follow the natural topography: the upper stream area, where water flows in a series of ditches and dykes; a middle stream zone in the existing urban area, where water flows in a

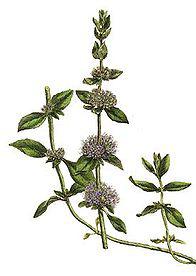

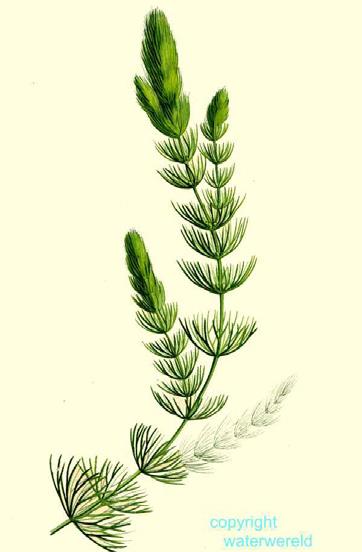

series of wadies and pools; and a down stream area in the landscape, where water flows in a big flood plain zone. Along Hadar stream the forest is open to preserve its current open character, while the forest is dense in the skirts. The tree types and vegetation species are diverse and native. They can survive a warm climate and long periods of drought. In the retention pools and wadies are moderately wet forests with trees and plants that can survive droughts and also withstand long periods of wet conditions.

1 . upper stream

2 . middle stream

1 . upper stream

2 . middle stream

1 . upper stream

2 . middle stream

3. down stream

terebinthus subsp. palaestina

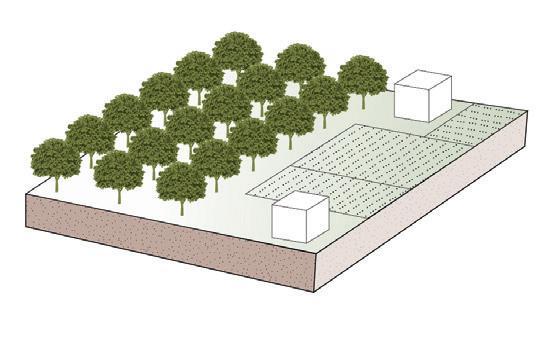

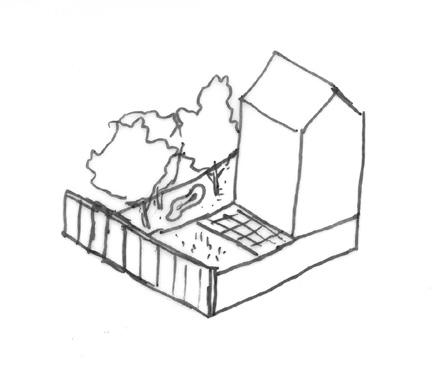

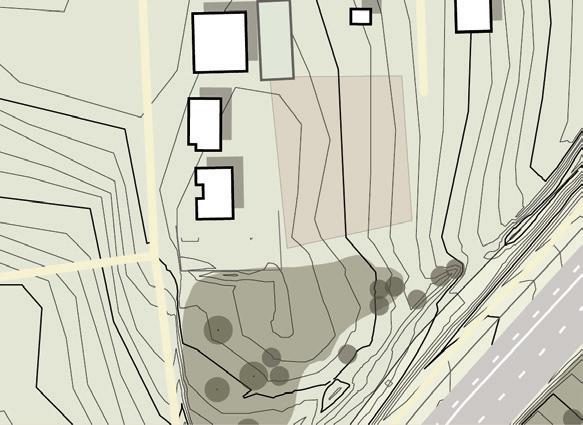

The existing neighborhoods form a cultural forest with private gardens and pocket gardens. By including private gardens residents take part in the forestation of their city. In addition, the empty and uncultivated spaces between the buildings are transformed into pocket rain gardens. Some gardens are play-

grounds that act like water squares for water retention. Their elements show the differences between summer and winter by emphasizing the water level. Other gardens are orchards or food forest that act like infiltration wadies. The orchards are an important part of the cultural history of Hod HaSharon. The new forest orchards include fruit trees that can survive warm climate, drought as well as wet periods.

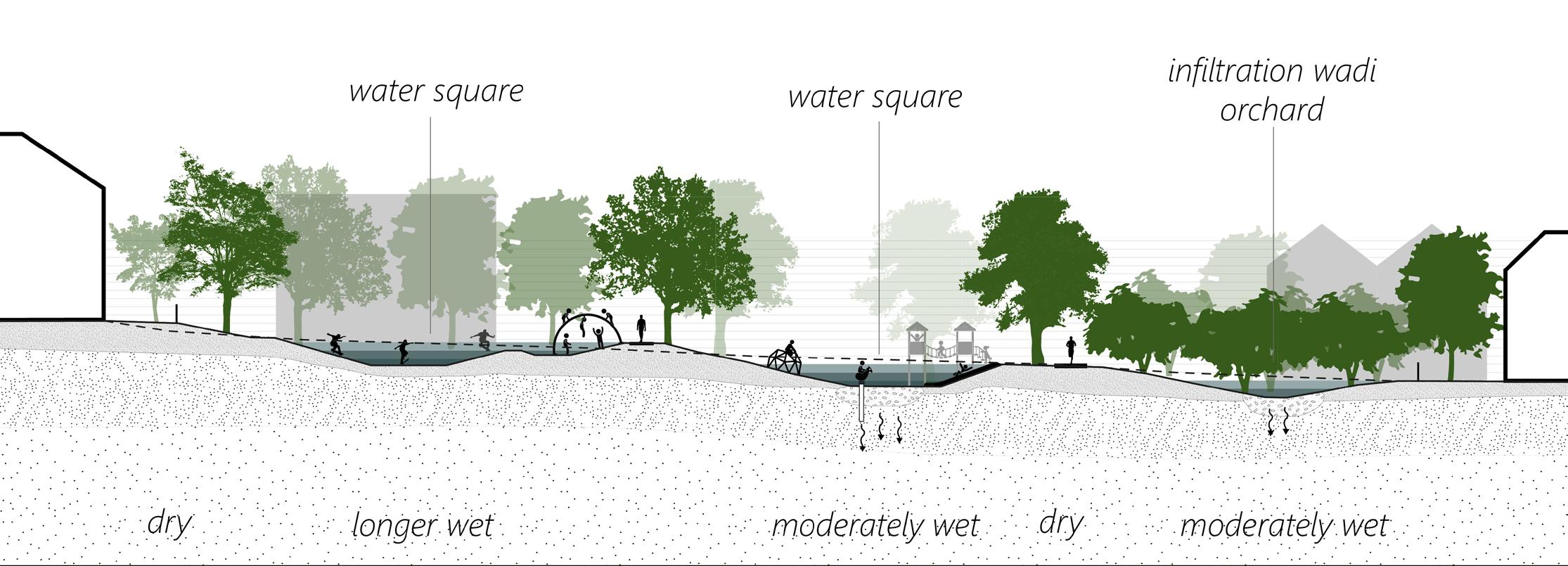

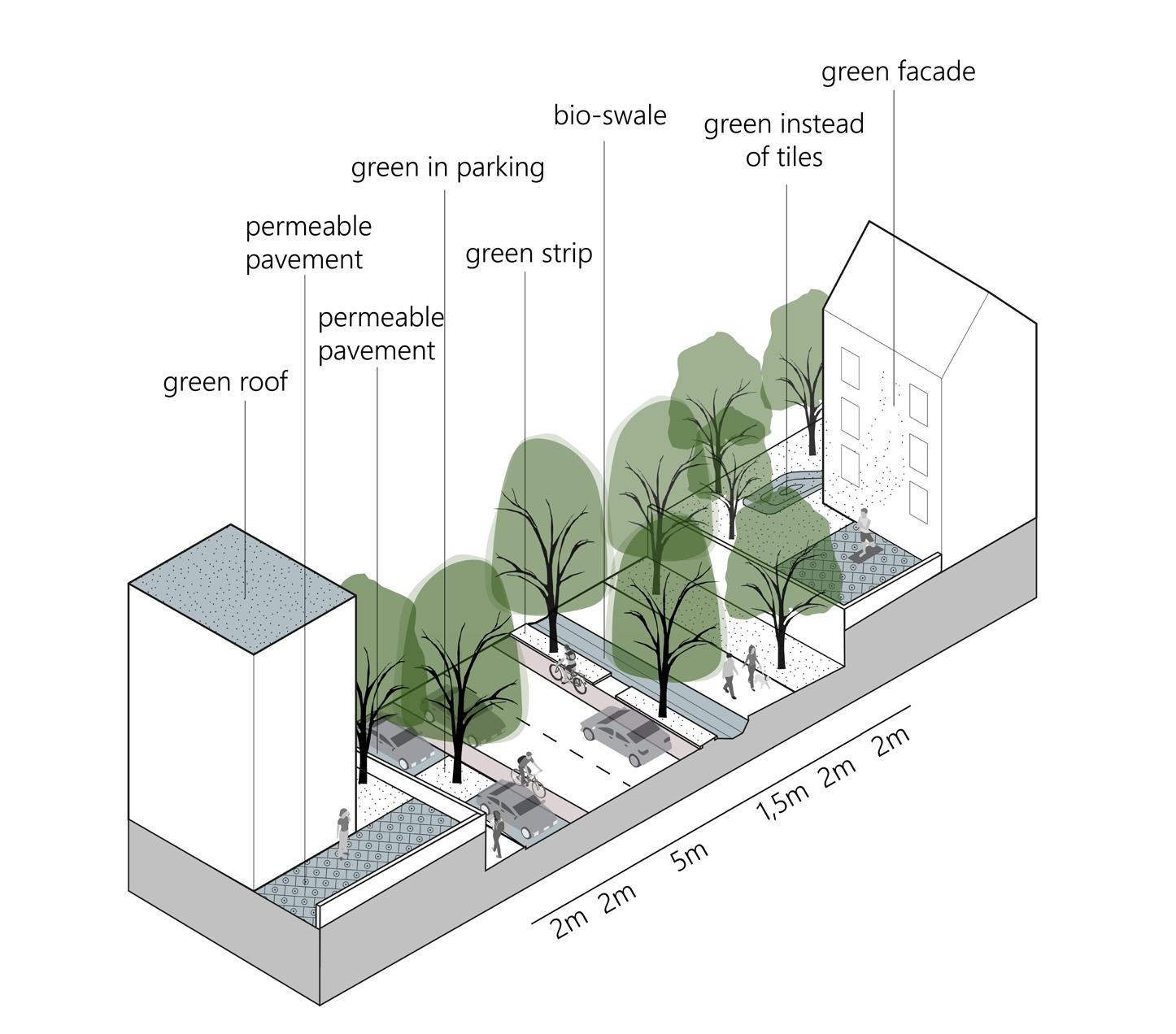

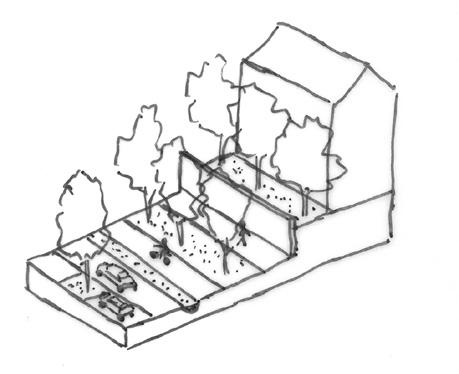

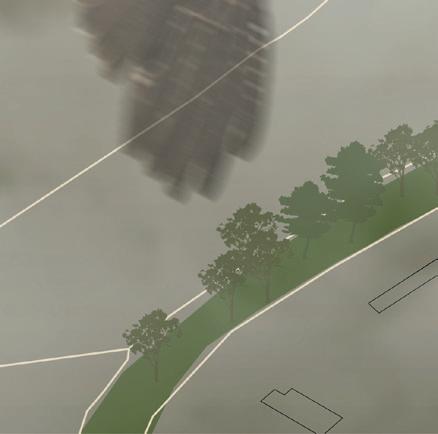

Streets occupy large numbers of surfaces in the city. Currently most streets are paved and have barely trees. Cars take a central position, while there are hardly bike paths. In my design I change the street profiles and make them smart and sustainable. The road is smaller and has spaces for bicycles. Along the

road is a bio-swale for pre-treatment of polluted runoff. The new street profile has more space for trees and vegetations that are relatively high in maintenance. They can survive a warm climate and long periods of drought. The street has a ‘cultural’ atmosphere.

Hadar stream

Dense wild forest

Open wild forest

Pocket (rain) garden

Street forest

Existing private gardens

New neighborhood

New houses in forest park

New water retention

Existing water body

Slow routes

Existing gras field

Existing sport field

Bike path

Walking path

The master plan provides an interconnected path network for slow-route mobility and recreational use

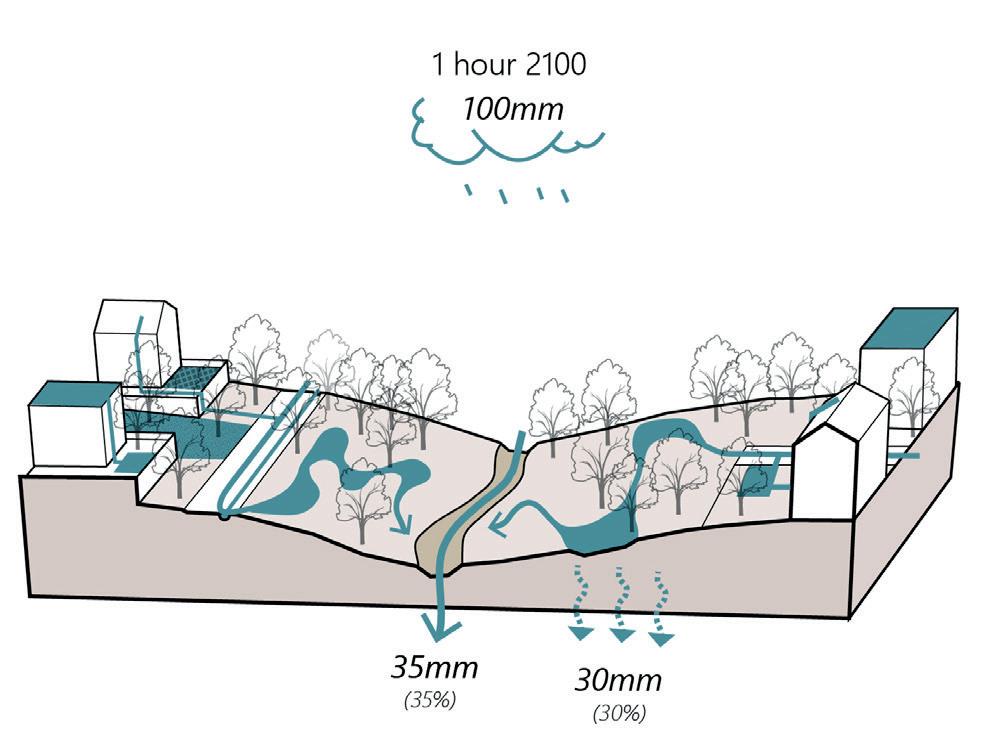

In order to solve the urban floods I create more spaces for water retention in the city. Capturing and holding the runoff in the forest park only, takes too much space and is not enough. Therefore, runoff retained in the existing and new neighborhoods. To achieve the maximum buffer capacity during heavy

rainfalls include as much space as possible. I calculated that 20% of the surface of the Hadar water-basin is enough to prevent urban floods during a rain event of 100mm per hour. I created a tool box with different principles that make sure the water system is balanced.

‘Sponge’ city

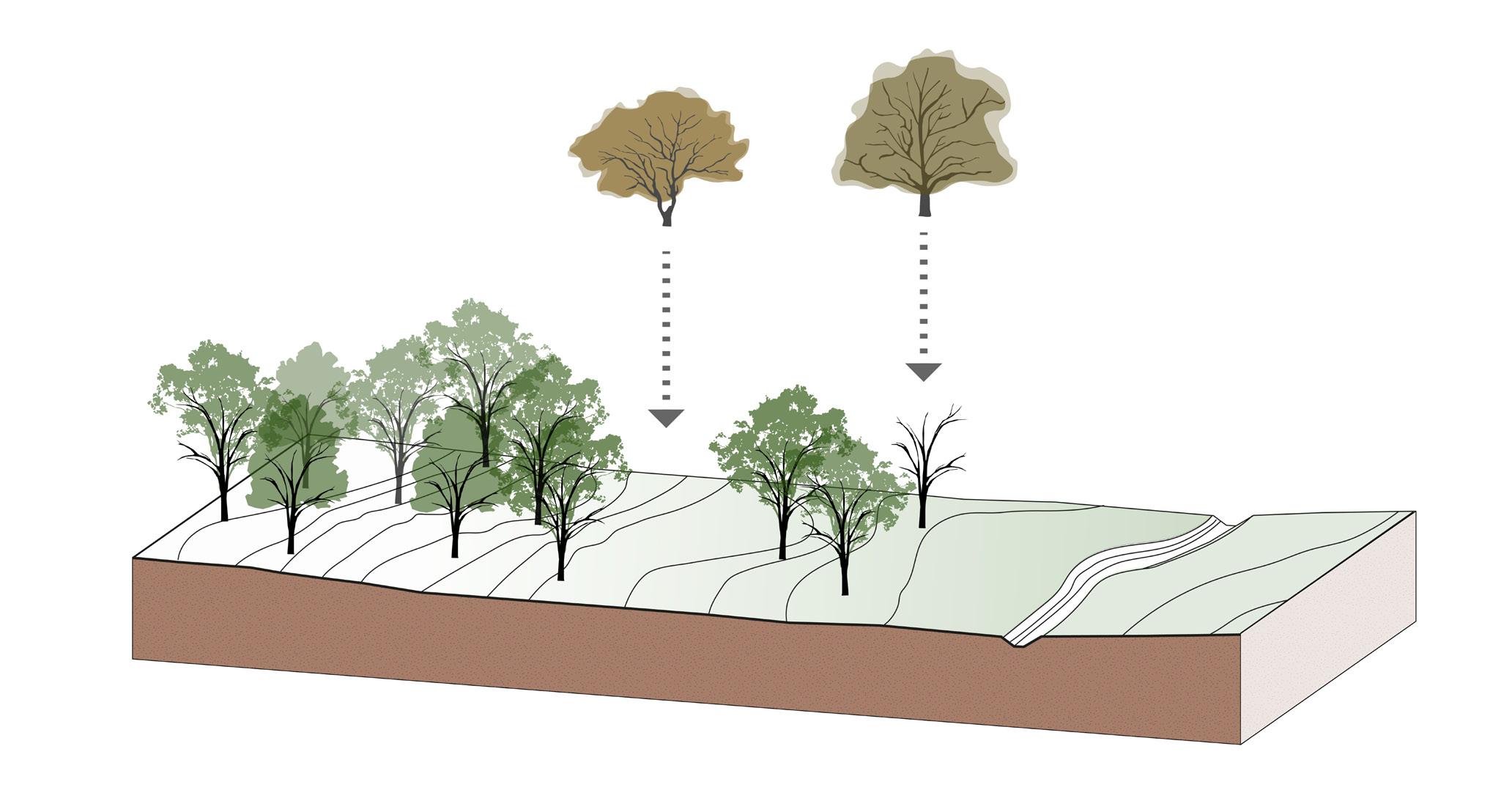

Time factor

Realizing a forest is a long process that demands patience. My strategy for the first years is to establish in future neighborhoods a tree nursery bank by seeding trees. In this period weeds will restore and improve the fertility of the soil. The next step, after 10-20 years, is to harvest part of the trees and to replant

them in the forest. This can be done together with residents. In the first 20-40 years there will exist a young forest. In the following 40-70 years there will exist an abundant fullgrown forest.

The last chapter of this report shows the design of the master plan. I elaborate on the forest park area and show three zoom-ins along Hadar stream: the upper stream, the middle stream, and the down stream. Each part explains a different system and shows my interventions.

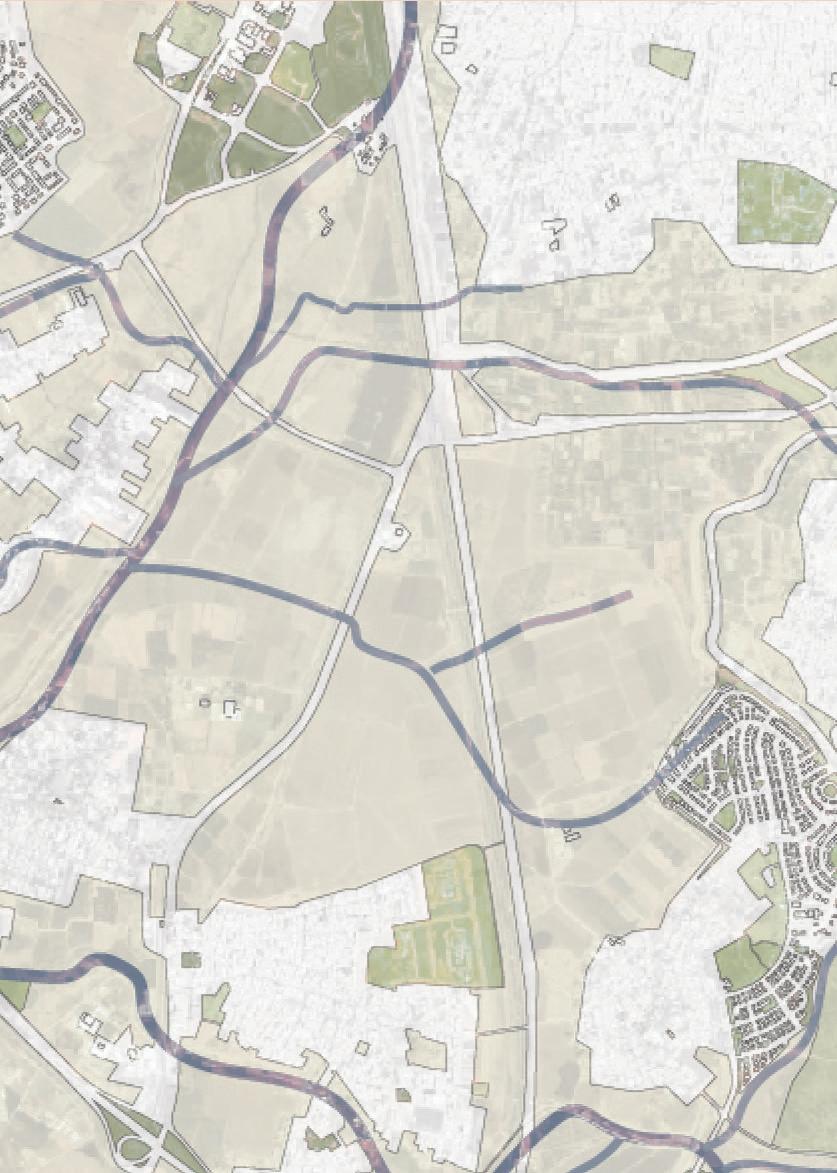

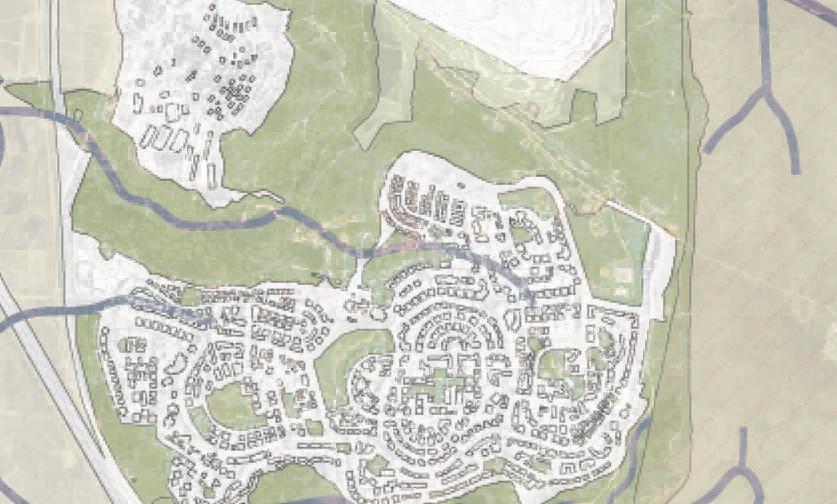

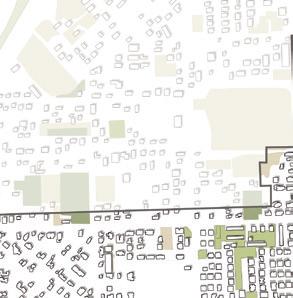

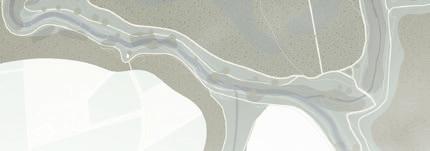

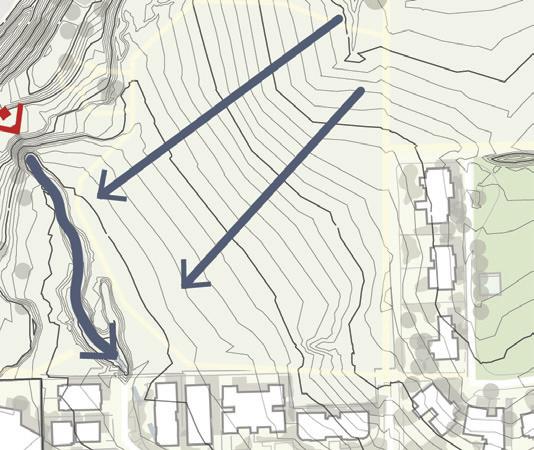

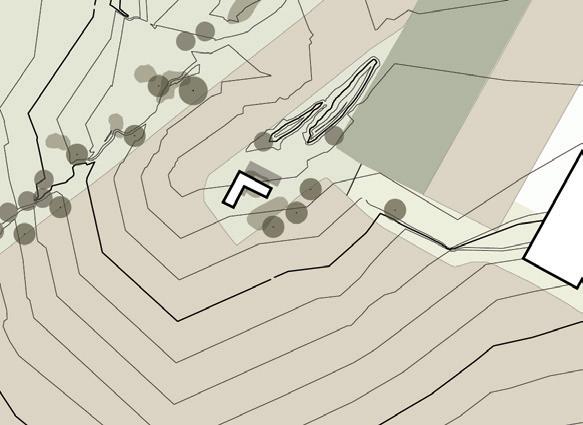

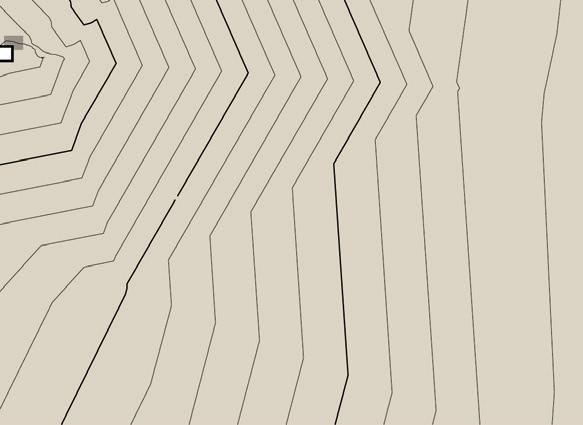

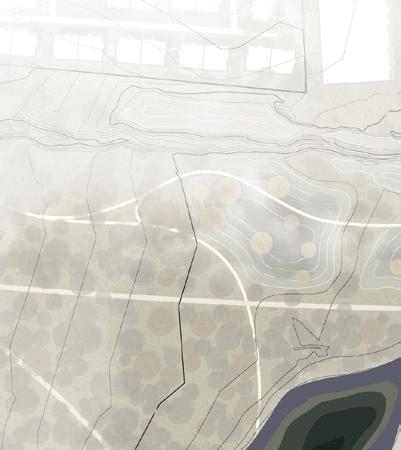

The upper stream area is one of the highest points of the city of Hod HaSharon and the Hadar water-basin. Hadar stream begins here. Highway no. 4 crosses this area and forms a hard barrier in the landscape. For this reason Hadar stream goes below the road in a closed pipe. Agricultural fields and non-native dense forests characterize this area. The topography is relatively steep. During my field visit I saw people walking in the fields and enjoying the landscape.

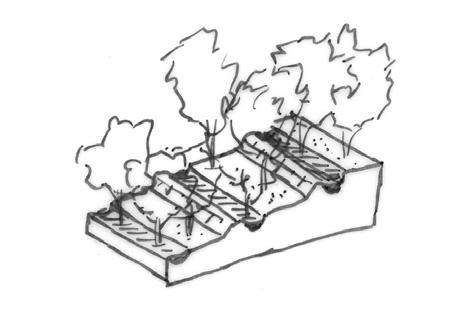

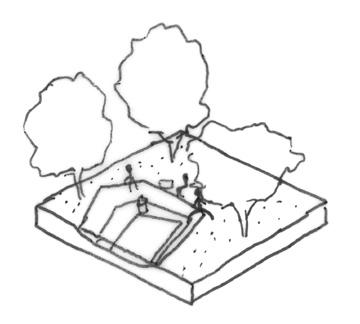

In my design I create a series of ditches and dykes that follow the existing topography lines. The function of these ditches is to hold rainwater before it reaches Hadar stream and to allow the water to naturally infiltrate into the soil. Moderately wet forests grow in the ditches, and dry forests grow in between the ditches. Moreover, I connect the two parts of this area that the highway separates: a bridge for cyclists and pedestrians, an eco-duct for animals, and a tunnel with a large opening for Hadar stream. I aim to attract people to this landscape and let them experience the water system. Therefore, I designed a walk-

ing bridge that hovers above the ditches and passes high between the trees. From the bridge the water system is visible and visitors can see various perspectives of the forest. At the highest point of my design the walking bridge ends. Here a watching tower is built that is reminiscent of the water towers that once existed in the area. Furthermore, in the upper stream area I provide spaces for new urban development that is characterized by a low density with tiny houses that are spread across the forest.

Existing water system

New water system

Existing water system

New water system

Hadar stream

Infiltration ditch

Moderately wet forest

Dry wild forest

Open wild forest

Cultural forest

Bike path

Walking path

Walking bridge

Watching tower

New neighborhood

Walking bridge

Watching tower

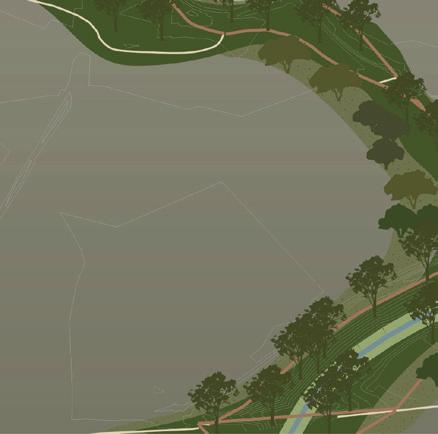

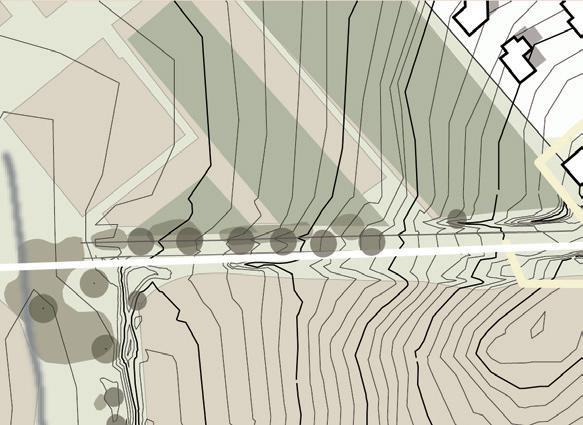

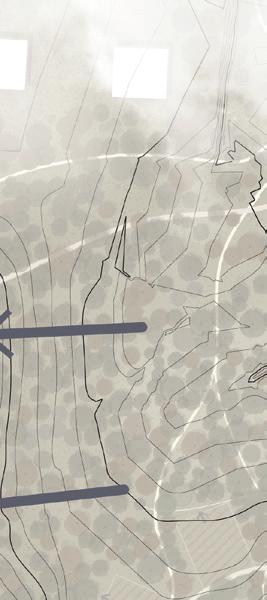

The middle stream is located in the middle of the existing city. Currently there are in this area agricultural fields, uncultivated grounds and a forest park. In the past the forest park ‘Beit Haneara’ was a boarding school. Nowadays the ground is owned by the municipality of Tel Aviv and there is still a school as well as abandoned historical buildings. A beautiful Ficus tree boulevard crosses ‘Beit Haneara’.

In the top left corner Hadar appears from a closed tunnel. The current water system drains stormwater runoff from the roads at three different points with underground pipes and discharges the water in Hadar. During the first rain events these roads are a polluted source.

During my field visit I saw the area’s potential. Several people ran and walked along Hadar, and kids had a lesson in the forest. I also experienced the heath in the agriculture fields in comparison to the forest where it was much cooler.

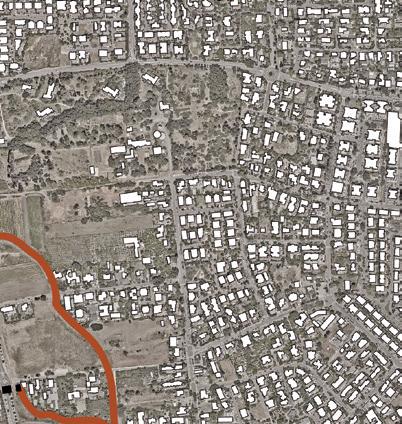

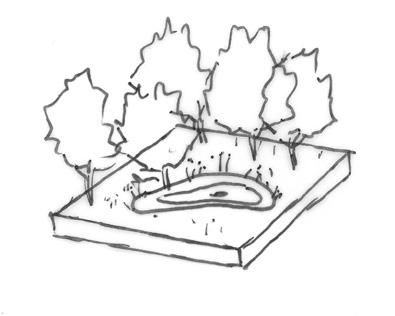

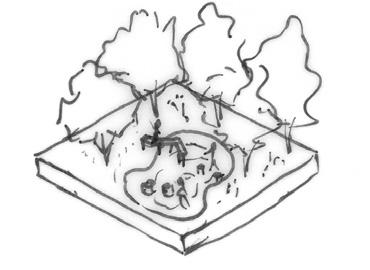

In this part I created a new water system that is characterized by several curvy side streams of Hadar. Stormwater runoff from the roads flows first into sedimentation pools to filter and clean polluted water. Along to the sedimentation pools are maintenance paths to clean them once a year. From these sedimentation pools the rainwater flows through a series of infiltration wadies and pools before

it arrives in Hadar. Between the wadies are two ecological (seasonal) pools. Here water infiltrates very slowly, so the pools remain wet longer than the wadies. In the past there were many of these kind of pools in the Sharon region, but most have disappeared from the landscape. This ecological pools are seasonal water bodies, since their water evaporates and in the summer they are dry. The ecological system in such seasonal pools is very unique, because while fishes cannot survive here numerous small creatures thrive. This attracts unique birds and insects. In addition, these ecological pools are interesting and attractive spots for people. I designed a birdwatching cabin so visitors can enjoy the animals while not disturbing them. I used the shapes of historical cow sheds that once existed in Hod HaSharon as inspiration for the design of the observation elements. In the infiltration wadies and the ecological pools moderately wet forests grow.

New urban developments are placed on the edges of the forest next to the existing urban area. Their orientation towards the forest turns the forest park into a new center for the existing neighborhoods. The housing typology is villas and apartment/houses blocks. The abandoned historical buildings of Beit Haneara are restored and get new function. In this area I give space for new developments with low density. The houses typology is tiny houses which are spread in the forest.

Existing water system

New water system

Existing water system

New water system

Hadar stream

Infiltration wadi

Infiltration wadi

Sedimentation pool

Ecological (seasonal) pool

temporarily wet dry

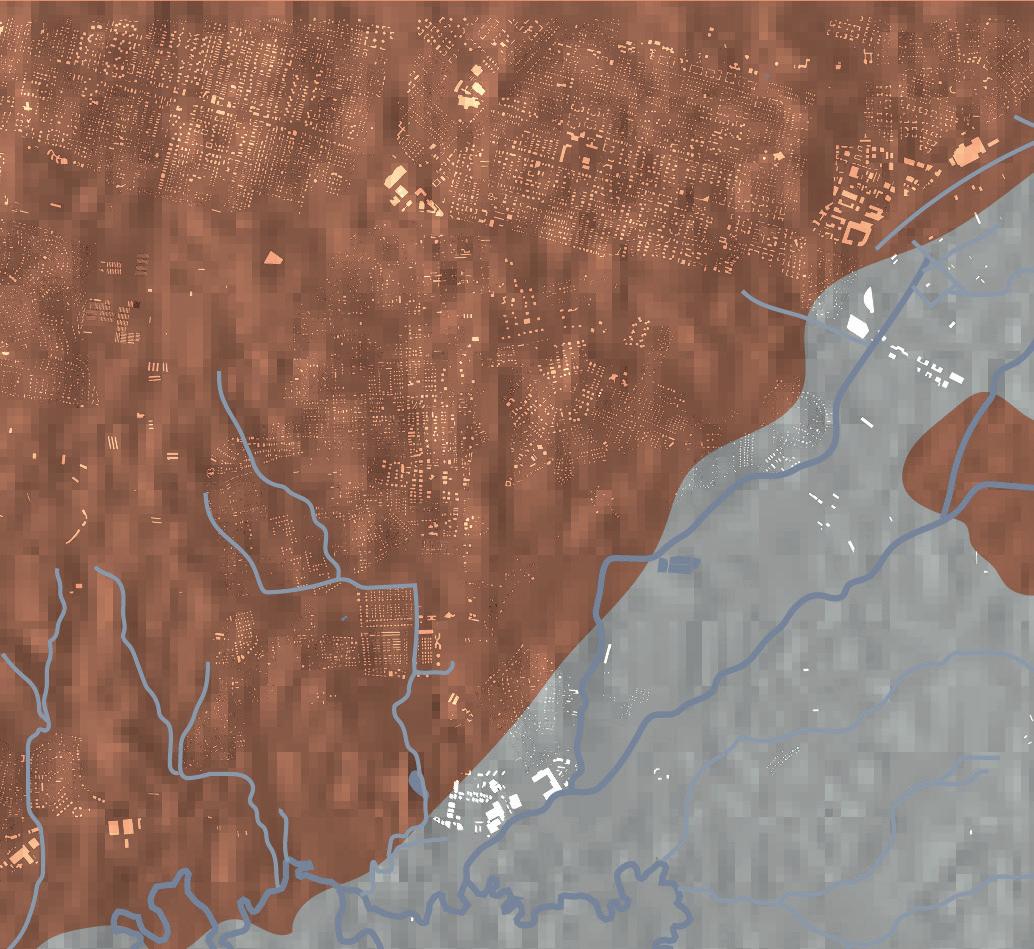

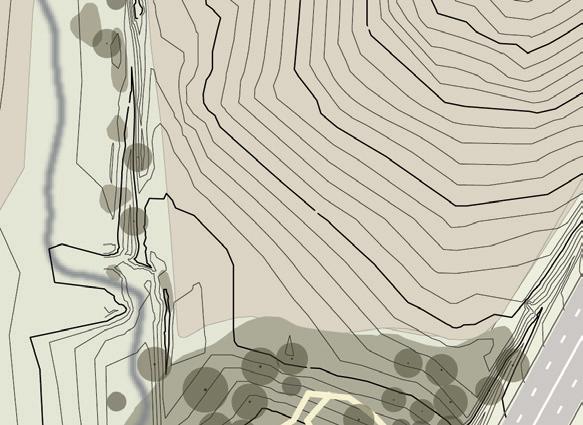

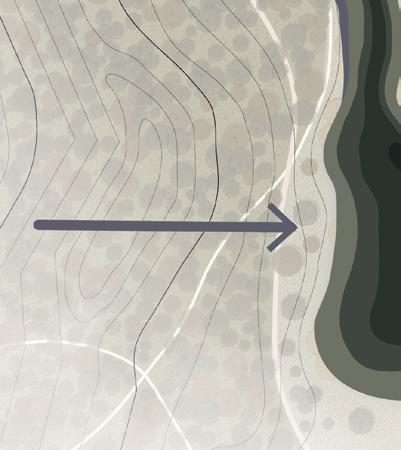

The southern part of Hod HaSharon is characterized by a gentle topography and an open landscape with primarily agricultural fields. This area is located between the Yarkon and the urban zone of the city. On the left side of Hadar there is an area with wet vegetation. Above Hadar exists an abandoned orchard field which slowly becomes wild. In the southern part of this area an ecological artificial lake has been created that accommodates wet habitat and attracts many visitors. In this down stream part the water of Hadar water-basin eventually arrives. It is in this area in particular that Hadar is overflooded during heavy winter storms, which also leads to flooded agricultural fields.

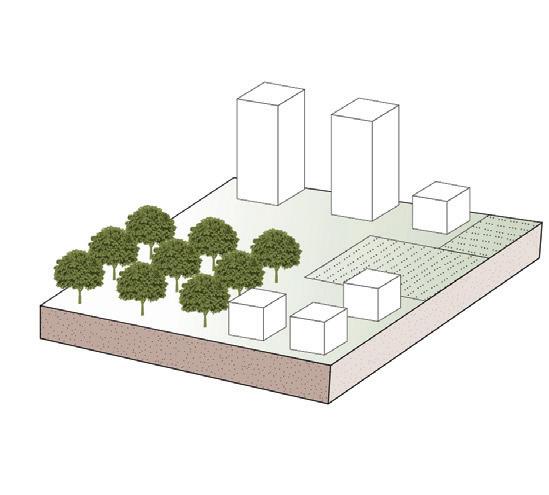

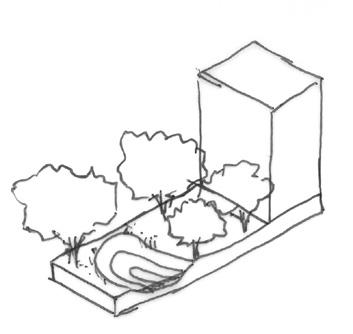

In my design the down stream area becomes a floodplain zone. It absorbs stormwater from Hadar to mitigate urban floods and to infiltrate water to the ground. In the floodplain zone Hadar is connected to two large side branches that capture and infiltrate rainwater. In these floodplains moderately wet forests can grow. In one of the water bodies I designed a ‘Moses’ bridge. When the floodplain

is underwater due to winter rains people can cross the water and experience the flood up close. For the design of the bridge I was inspired by the historical open tunnels that were once used as a drainage system. In this area new houses are placed in clusters on the higher grounds next to the floodplain zone. The housing are towers with a diversity of heights that are oriented towards the forest.

Existing water system

Existing water system

Hadar stream

Flood plain

Dry wild forest

Moderately wet forest

Open wild forest

Cultural forest

Existing wet vegetation

Bike path

Walking path

‘Moses’ bridge

Spaces for new houses

0 10 50 100m N

existing

Flood plain - dry situation

This project offers a new perspective of an integral climate adaptive design approach in the Israeli urban environment. As a case study, I have shown how the city of Hod HaSharon can be a climate resilient city. The plan can be an example for other Israeli cities that deal with urban developments and climate change issues.

Restoring the vanished forests in urban environments is a vital element in my approach. Combining this with a sustainable water management system proves to be the key to achieve a climate resilient city. It not only contributes to hydrological and ecological solutions, but is also has social and economic benefits. First, this integral approach reduces the risk of urban floods and recharges the aquifer, an important drinking water resource. Furthermore, enhancing the forest in the city supports and protects bio- and plant diversity, creates a microclimate, and cools the city in warm days. It also

restores the soil and improves its fertility and permeability. My approach also contributes to socio-economic benefits. It not only stimulates education and raises awareness of sustainability, but it also provides an interconnected slowroutes network and spaces for leisure, recreation and tourism. In addition, my design interventions reduce the costs of damages of urban floods, enhance the aesthetics of the urban image, and increase the value of real estate.

In conclusion, my idea is to accommodate nature in the city and connect people to their landscape. I hope this project will raise awareness, change peoples’ perspective, and convince stakeholders that a climate adaptive design approach is essential for a sustainable future.

Upper stream

Middle stream

Down stream

Upper stream

Articles and reports

(p.22) Alpert, Pinhas (2013, 18 November). Climate Changes over Israel & Mediterranean; Recent Observations and Future Predictions p. 41.

Alon-Mozes, Tal Naomi Carmon, Micheele Portman, Shula Goulden and Nadav Shapira (May 2018) Creating Water-Sensitive Cities in Israel. Project 4.1: Water-sensitive Urban Design: Best Practices and Beyond.

Asaf, Lior (2018, June 19). A course in sustainable management of urban runoff and drainage and its integration with urban planning [Hebrew].

Firestone, Michal (May 2015). Hod HaSharon, historical research [Hebrew].

Goulden, Shula, Michelle E. Portman, Naomi Carmon and Tal Alon-Mozes (2018). From conventional drainage to sustainable stormwater management: Beyond the technical challenges. Journal of Environmental Management 219.4 37-45.

Israel Meteorological Service (March 2021). Historical trends and trends predicted in the precipitation patterns in Israel until the end of the century p. 24 [Hebrew].

The Center for Water Sensitive Cities in Israel. (2018) Creating water sensitive cities in Israel. An inter-disciplinary science practice program delivering sustainable and liveable urban environment through innovative urban water management [Hebrew].

Nature Protection Society (October 2014). Urban nature infrastructure survey [Hebrew].

(p.48) Carte Topographique de la Palestine dressée d’après la carte topographique levée par le savant Jacotin et autres Géographes de l’Armée d’Orient, pendant l’Expédition Syrienne par les Généraux Buonaparte, Murat et Kléber l’an 1799 (Paris, 1818)

Map of Western Palestine in 26 sheets from surveys conducted for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund during the years 1872-1877 (Southampton: Stanfords, 1880).

(p.9,30) Exaggerated Relief Map of Israel 4096 x 2304 (2020, 18 May). https://i. redd.it/w8yibm2jzhz41.png

(p.21,25) Hod HaSharon Weather averages & monthly Temperatures (2022, 18 September) https://www.weather2visit.com/middle-east/israel/hod-hasharon.htm

(p.22) ‘Relentlessly hotter: Sizzling heat increasingly the norm in Israel, data shows’, The Times of Israel (2021, August 3). https://www.timesofisrael.com/sizzling-heat-increasingly-becoming-the-norm-data-shows/

(p.38) Tel Aviv - Hayarkon Park - Variety of vegetation in the Yarkon Reservoir (2020). https://www.streetsigns.co.il/signDetails.asp?s=2335