WHAT WATER TEACHES

FALL 2022 VOL. 94 NO. 1

20 The Responsibility Is Personal

Dean Claudia Marroquin ’06 talks about the challenges of her work, the importance of kindness, and the role her personal story plays in assembling a Bowdoin class.

26 Finding the Pieces

Ed Burton ’91 pieces together information in painstaking searches to make good on a pledge to leave no soldier behind.

44 Q&A

Eric Ebeling ’98 steers a shipping company through geopolitics and other heavy weather.

FALL 2022 VOL. 94 NO. 1

Contents

32 Larger Than Everything Water is all around us in the landscape at Bowdoin, but it’s also ubiquitous in a place you might not expect—the classroom.

Open to Possibilities: Denise Shannon balances work with music, acting, and more.

Dine: Salted pumpkin caramels from food writer and editor Christine Burns Rudalevige.

A Tiny Island: Professor Brian Purnell tells the story of New York City in a Bowdoin class.

Remembered: With help from Arctic museum scholars, a group of Inughuit explorers are recognized.

In Beauty, a Benefit: Abelardo Morell ’71 donates two special prints to raise funds for financial aid.

Honoring the Animals: In caring for a world of creatures, veterinarian Carl Spielvogel ’13 has learned a few things.

Webb ’68 on using a different lens.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 1 Column Forward Connect In Every Issue 47

51

56

4 Respond 46 Whispering Pines 64 Here 5

7

Golden Owens ’15 explores the world of digital assistants.

Drew

Gabriele Caroti ’97 is the founder of movie and music label Seventy-Seven.

8

11

17

18

For three nights before the start of their first semester, an Orientation trip from the Class of 2026 camped in the foothills of the White Mountains. Located in the northwest corner of Maine, the campsite is a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Bowdoin in the remote Aziscohos Valley. They hiked, went paddleboarding, kayaked, and canoed, and then cooked and camped together—on this night under a sky full of stars.

Photo by Fred Field

Photo by Fred Field

Formative Days

Dan Covell’s piece in the spring/ summer edition brought back some terrific football memories. I graduated in 1965. I went to Bowdoin largely because of Sid Watson, then head hockey coach at the College. I was a hockey player at St. Paul’s School (SPS) in Concord, New Hampshire, when Sid saw me play and encouraged me to apply. Largely also because of him, I decided to play football at Bowdoin as well. I had been the captain of the soccer team at SPS and did not feel that I could change to football at St. Paul’s. I waited until I got to Bowdoin. Playing for Nels Corey and Sid in football was a great honor. As many know, Sid played professional football, and he was an outstanding teacher of the game. We were a pretty good team and went 6-1, beating Maine in the last game 7-0 in Orono my junior year. He was the backfield coach, and had he asked me to go barefoot up Mt. Everest, I would have gladly done it. Again, thanks to the editor and to Dan for bringing back fond memories of a meaningful and formative friendship for me.

MAGAZINE STAFF

Executive Editor and Interim Editor

Alison Bennie

Associate Editor

Leanne Dech

Designer and Art Director

Melissa Wells Design Consultant 2Communiqué Editorial Consultant Laura J. Cole

Contributors

Mary Baumgartner Ed Beem P’13 Adam Bovie Jim Caton Doug Cook

Cheryl Della Pietra Chelsea Doyle Rebecca Goldfine Scott Hood Micki Manheimer Janie Porche Tom Porter

On the Cover: Photographs by Bob Handelman

FROM FLEDGLING TO FLOURISHING

I was delighted to see the last page of your Spring/Summer 2022 issue devoted to the Maine Island Trail Association (MITA). I was recruited by Dave Getchell in 1991 to help the fledgling MITA, then part of the Island Institute, with its start-up fundraising program. In this capacity, I was present at the meeting a few years later when Horace “Hoddy” Hildreth ’54, who was then president of the institute, agreed to allow MITA to become independent. It has been a pleasure since then to see the organization flourish and, more selfishly, for me to enjoy the unique experience of visiting scores of the MITA-protected Maine islands. It should not be forgotten that MITA founder Dave Getchell had a bit of Bowdoin in him, having spent a year or two there before finishing at the University of Maine, Orono.

Charlie Graham ’55

SEND

US YOUR NEWS!

We want to hear from you, and so do your classmates! Email classnews@bowdoin.edu or fill out a class news form on our website, bowdoin.edu/magazine.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE (ISSN: 0895-2604) is published three times a year by Bowdoin College, 4104 College Station, Brunswick, Maine, 04011. Printed by Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine. Sent free of charge to all Bowdoin alumni, parents of current and recent undergraduates, members of the senior class, faculty and staff, and members of the Association of Bowdoin Friends.

Opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors.

Please send address changes, ideas, or letters to the editor to the address above or by email to bowdoineditor@bowdoin.edu. Send class news to classnews@bowdoin.edu or to the address above.

4 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Respond

Bill Mathews ’65

Sid Watson, circa 1959

PHOTO: GEORGE J. MITCHELL DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS & ARCHIVES

DENISE SHANNON DIRECTOR OF PROJECTS AND PLANNING FOR STUDENT AFFAIRS

OPEN TO POSSIBILITIES

Music has always been part of my life. I started piano lessons at eight, and violin lessons when I was twelve. I have been playing with the Midcoast Symphony Orchestra for twenty years, and I feel fortunate to play with a group that continually challenges itself with different types of music. In a “small world” coincidence, my first boss at Bowdoin is also a violinist, and we played together in the symphony for a few years.

I’m currently in my fifth job at the College— supporting the dean for student affairs—which says a lot about opportunity at Bowdoin. I value the many friendships I’ve made here and the com munity. And I love the variety of events available on campus, having access to a great gym, and being able to eat at wonderful dining facilities.

I grew up in Overland Park, Kansas, where most of my family still lives. Being so far from home, it’s very important to me to keep in touch with family and friends. And while I am pretty busy, I always try to stay open to new possibilities.

Doing so led me to take a chance on voice acting. For the past four years, I’ve been playing the character of Rhonda Roupp on the Restless Shores podcast. We’ve recorded two hundred episodes so far for the show, which is about intrigue surrounding the billion-dollar Roupp Pharmaceuticals located in Gamote Point. That led to doing radio interviews before each concert with the orchestra—and narrating a piece with the orchestra this winter.

I love the challenge of voice acting and playing the violin because there is always room to grow. And when I’m not thinking up my next personal project, I love taking advantage of the gifts of nature that Maine provides, such as hiking, explor ing nature preserves, and relaxing by the ocean.

Denise Shannon has worked at Bowdoin in four different areas: human resources, career planning, alumni career programs, and the dean for student affairs office. Outside of work, her pursuits are just as varied. She’s a violinist and board member for the Midcoast Symphony Orchestra, an actor, and a voice actor.

Forward

FROM BOWDOIN AND BEYOND

PHOTO: HEATHER PERRY

Alumni Life

MUTUALLY REVEALING

A new Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA) exhibition juxtaposes the work of two artists, Helen Frankenthaler and Jo Sandman, who built on the legacy of the abstract expressionism in which they were rooted. “Growing out of a close study of Frankenthaler’s intimate engagement with printmaking over five decades, and enriched by careful attention to the allied artmaking strategies developed by Sandman, Helen Frankenthaler and Jo Sandman: Without Limits sheds light,” says museum codirector Anne Collins Goodyear, “on the new creative pathways pioneered by these remarkable artists from the 1960s forward.”

Although not personally acquainted, Frankenthaler and Sandman expressed interest in the question of artistic influence and the intercon nectedness of artistic vision among contemporaries across generations. In this exhibition, the BCMA places Sandman and Frankenthaler— through their works—in dialogue with one another and allows them to, as Goodyear writes, “mutually reveal the radicality of the experimen tation in which each was embarked.”

The exhibition, she goes on to say, can open up new questions for its viewers “about the creative potential available in any given moment, about the intersection and transformation of artistic paradigms, and about the push and pull of the ever-shifting background and foreground of history itself.”

Below: Deep Sun, 1983, Artist Proof 7/16. Color etching, soft-ground etching, aquatint, spitbite aquatint, drypoint, engraving, and mezzotint on paper, 30 x 40 1/8 in. (76.2 x 101.92 cm), by Helen Frankenthaler, American, 1928–2011. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Gift of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, 2019.28.6. © 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Tyler Graphics Ltd., Bedford Village, New York.

A Troubling Truth

AS A SPECIALIST in the history of Nazi Germany, the Holocaust, and genocide, Peter Hayes ’68 was among the historians tapped by acclaimed documentary maker Ken Burns H’91 in his latest three-part series for PBS. The US and the Holocaust examines the response of the US to one of the greatest human itarian crises of the last century and exposes the viewer to some uncomfortable truths about the extent of global anti-Semitism in the years leading up to the war. America experienced a xenophobic backlash, explained Hayes, who is a professor emeritus of history at Northwestern University, as large waves of immigrants started arriving in the late nineteenth century— many of them Jews from Central and Eastern Europe.

“People tended to increasingly view nationalities as if they were breeds or species,” he observed. “To liken nationalities to breeds was a fundamental categorical mistake. The biological pool of human beings between Germans and French, Dutch and English, is nothing like the biological or genetic pool between poodles and German Shepherds.”

Another disturbing fact highlighted by Hayes was the admi ration shown by a young Adolf Hitler for the way America treated its indigenous populations: “Hitler saw the expansion of Germany into Eastern Europe as foreshadowed by what we had done in North America—the expansion of the white people of the United States across the continent from east to west, brushing aside the people who were already here and confining them to reservations.”

6 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU PHOTOS: ( DEEP SUN ) LUC DEMERS; (HAYES) COURTESY UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM Forward

On View

Peter Hayes ’68 was featured in Ken Burns’s new documentary about the Holocaust.

Peter Hayes ’68

Dine

Salted Pumpkin Caramels

Recipe by Christine Burns Rudalevige

Recipe by Christine Burns Rudalevige

It's a good thing this recipe yields over five dozen caramels, because you can't eat just one. The spice is subtle, the sweetness countered by a shot of lemon juice, and the soft center enveloped by the crunch of pepitas on one side and the crackle of salt on the other.

Place the pepitas in a skillet over medium heat and toast them until they start to pop.

Line the bottom and sides of an eight-inch square glass pan with parchment. Butter the parchment just on the sides of the pan. Evenly spread the toasted pepitas on the bottom of the pan, on top of the parchment.

In a saucepan, combine the heavy cream, pumpkin puree, and spices. Get the mixture quite warm but do not boil. Set aside.

⅔ cup unsalted pepitas 1 ½ cups heavy cream

⅔ cup pumpkin puree

1 teaspoon pumpkin pie spice 2 cups white sugar

½ cup light corn syrup ⅓ cup good maple syrup ¼ cup of water

4 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut in chunks

1 teaspoon lemon juice ¾ teaspoon flaky sea salt

DID YOU KNOW?

The current record for the world’s heaviest pumpkin is 2,624 lbs. That’s the weight of a 1971 Ford Maverick! This gigantic gourd was grown by Belgian Mathias Willemijns in 2016. The heaviest pumpkin ever grown in the United States weighed 2,528 lbs. It was grown by Steve Geddes of New Hampshire in 2018.

In a second pan, one with a heavy bottom and with sides at least four inches high, combine the sugar, both syrups, and water. Stir over medium-high heat until the sugars are melted, then let it boil until it reaches 244 degrees (the soft ball point on a candy thermometer). Then very carefully add the cream and pumpkin mixture, reduce the heat, and slowly bring this mixture back up to 240 degrees as registered on a candy thermometer. This can take some time—maybe 30 minutes—but don’t leave the kitchen. Watch the pot carefully and stir the mixture more frequently once it hits 230 degrees to keep it from burning at the bottom of the pan.

As soon as it reaches 240 degrees, pull it off the heat and stir in the butter and lemon juice, stirring vigorously so that the butter is fully incorporated.

Pour the mixture into the prepared pan. Let cool thirty minutes and then sprinkle the flaky sea salt over the top. Let the caramels fully set (at least two hours) before using a hot knife (dip it in hot water and wipe it dry before each cut) to cut them into one-inch squares. Wrap them individually in waxed paper if not serving immediately.

Christine Burns Rudalevige is a food writer who currently serves as the editor of edible MAINE magazine. She moved to Maine ten years ago with her husband, Andrew Rudalevige, Bowdoin’s Thomas Brackett Reed Professor of Government.

ANDREW ESTEY BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 7

PHOTO:

NYC was the first city in the world to structure itself into the future. Starting in 1808, a group of cartographers, geographers, surveyors, real estate speculators, and bankers laid out a grid that reached into areas where almost no one lived, planning out a grid for a city that did not exist.

Did You Know?

A Tiny Island

Telling the story of New York City in a Bowdoin classroom.

Illustration by Jakob Hinrichs

Illustration by Jakob Hinrichs

Associate Professor of Africana Studies Brian Purnell is teaching a class this semester on his hometown, New York City. Born and raised in Coney Island, Brooklyn, Purnell centers much of his scholarship on the legacy of racial activism in New York City, but Gotham: The History of a Modern City takes a broad look at what forces and moments made “the city so nice they named it twice” the global metropolis it is today. The class looks at the ways the city developed over four hundred years, exploring New York’s history from the time period when Algonquian-speaking people hunted, fished, and farmed throughout the region up to the present, when New York City stands as one of the premier metropolises in the world. Its nickname, Gotham, and the mythical legacy that evokes has become as much an alter ego as an actual reflection of the city at hand, and students in the class confront opposing narratives and realities that exist in New York’s history. We talked to Professor Purnell about what makes this tiny island such an outsized force in the nation, the culture, and the world.

Controversial urban planner Robert Moses redesigned how cities worked. He knew the law so well he was able to consolidate multiple commissionerships in one person him. Every bridge, beach, or park, every highway, tunnel, or playground is where it is in the city because Moses said so. Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, every highway in NYC and Long Island, the Throggs Neck and the Whitestone Bridge, Jones Beach, Orchard Beach all him.

Nineteenth-century writer Washington Irving referred to the city as “Gotham”—a term that dates back to medieval England folklore and means “Goat’s Town,” a mythical place filled with gullible, simple people.

New York City 1990s streetball style influenced the world of basketball—“Every point guard in the NBA now plays like a New York City point guard,” says God Shammgod, talking about NYC Point Gods, a 2022 documentary. Ballhandling, charisma, and swag all made their way from NYC streets to NBA courts.

8 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Forward

In 1643, the Dutch West India Company gave Lady Deborah Moody, an English immigrant who had been branded “a dangerous woman” and excommunicated from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the southwestern tip of Long Island, and she planned out Gravesend in what became Brooklyn. The settlement, the first to be run by a woman, was planned around a town square with estates extending from it like flower petals.

The indigenous Lenape people taught new settlers how to fish, hunt, and live. They enfolded them into their politically consolidated ways of interacting from the 1620s until wars broke out between the Indigenous and the Dutch/English in the 1640s. One was The Pig War, which started in Staten Island over a murdered pig.

Religious freedom was born in New York City. The Dutch settlements were the most tolerant in the New World, and when Peter Stuyvesant wanted to ban anyone who wasn’t Dutch Reform in the 1660s, he was overruled by the Dutch West India Company, which deemed such practices not just in violation of the freedom of conscience enshrined in the Netherlands but also bad for business.

NYC is a birthplace and important cultural hub for art and music: hip-hop, reggaeton, salsa, poetry, art.

Before New York, every major city had spread out to grow. When the grid ran out of room, a fortunate combination of electricity, the invention of steel, and— critically—the discovery that the city sat on granite led to New York growing by conquering the sky.

We know about the Battle of Gettysburg, but New York had its own skirmishes in the Civil War, with July 1863 draft riots, lynching, and violence against Black New Yorkers.

On the Shelf

Mental Health

Angel of the Garbage Dump: How Hanley Denning Changed the World, One Child at a Time Jacob Wheeler (Mission Point Press, 2022)

Jacob Wheeler has lived in and written about Guatemala, where HANLEY DENNING ’92 founded Safe Passage, and he and Hanley interacted a few times when he was there. Inspired by her story before she was killed in a car accident in Guatemala in 2007, he decided to write a book about her as he saw how her legacy continued to grow years after her death. “This is a story about the lives she changes, and the people she inspires to walk alongside her and carry on her mission, even after she’s gone,” he writes in the prologue.

Healthier Futures

The Unwanted PETER CLENOTT ’73 (Level Best Books, 2022)

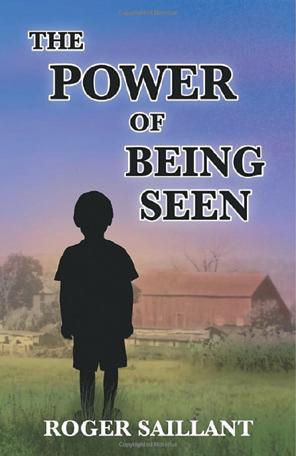

The Power of Being Seen ROGER SAILLANT ’65 (Saratoga Springs Publishing, 2022)

Mental health is widely reported to be among the biggest issues facing college students today. Bowdoin is working to better understand the issues in an effort to help students successfully transition from high school to college to careers. As part of that effort, Bowdoin partnered with Bank of America in 2019 to launch an annual forum that brings together leaders to address a range of topics surrounding mental health, including this year’s event featuring US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy. On-campus actions include:

Awareness: During this year’s Convocation, President Clayton Rose urged students “to not deal with the challenges, issues, self-doubts, or anxieties all by yourself. We are a community, we have each other, and we have among the best resources of any college to help you.” Those resources include a series called the “Elephant in the Room.” During the pandemic, Roland Mendiola, director of counseling services, started recording interviews with Bowdoin employees about ways culture, upbringing, and experiences may have influenced their mental and emotional well-being and their willingness to seek help and care. What started on Zoom out of necessity has now found its footing in the online format, and the series has grown to over twenty episodes. Watch the videos at bowdo.in/vi6.

Managing Psychosocial Hazards and Work-Related Stress in Today’s Work Environment: International Insights for US Organizations ELLEN PINKOS COBB ’80 (Routledge, 2022)

Laying Roots: Poems on Grief and Healing AMANDA SPILLER ’17 (Amanda Spiller, 2022)

Access: In addition to its counseling and wellness center, Bowdoin offers telehealth options, and students can leverage a network of providers. This year, for World Mental Health Day, the College introduced Togetherall, an online platform with modules, self-assessments, and an online forum where users can post questions and comments anonymously.

Prevention: Wellness classes and one-on-one coaching are available to teach students how to take better care of themselves mentally, emotionally, physically, socially, spiritually, and financially.

10 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Forward

ILLUSTRATION: DAVIDE BONAZZI

Remembered

One hundred and thirteen years after their journey, a group of intrepid Inughuit explorers are having their stories told.

IN HIS ACCOUNT of the 1908–1909 expedition to the North Pole, Robert Peary writes of the “quartet of young [Inughuit] who formed a portion of the sledge party that finally reached the long-courted ‘ninety North.’” Along with Black explorer Matthew Henson, that quartet would be among the first to reach the North Pole. Their names—Ootah, Egingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah—are not as well known in Western culture as Peary’s or even Henson’s. But without their involvement, the journey would have been nearly impossible.

“Peary and Henson had learned from Inughuit, and they were both accomplished dog sledge drivers,” says Genevieve LeMoine, curator at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, which in 2023 will relocate and expand to the new John and Lile Gibbons Center for Arctic Studies. “But by that point, Peary was kind of old. He’d lost most of his toes. He didn’t walk all that well. He personally could not have driven a dog sledge to the Pole by himself.”

Earlier this year, LeMoine and museum director Susan Kaplan participated in an effort sponsored by the Explorers’ Club to admit the four men into the Society of Forgotten Explorers. The goal of the society is “to honor unknown, lesser-known, or unsung explorers from underrepresented communities and ethnicities, and tell their stories.”

“It’s a wonderful effort for the Explorers’ Club to realize that they have overlooked a community of people that need and deserve recognition,” says Kaplan. “But I am always reminding myself that within those communities the individuals are often very well known. Ootah, for example, was this incredibly famous, revered man among the Inughuit people.”

According to LeMoine, Ootah led a long life as an accomplished hunter and was viewed as a leader in the community. “He was, for instance, one of the only people to voice opposition to the forced relocation of the community in the 1950s when the Thule Air Base was constructed and the Inughuit were forced off the land,” says LeMoine. “It didn’t do any good, unfortunately. They were still forcibly relocated. But he was a very well-respected member of the community.”

Kaplan and LeMoine are working to bring more recognition as well to the women and children who were also involved: seventeen Inughuit women and ten children journeyed as far north as the winter quarters.

“If Peary had left all those women behind, they wouldn’t have had anybody hunting for them, so they would’ve starved,” says LeMoine. “He had to bring them from that perspective. But even if they would’ve been perfectly fine left behind, he needed the work that they did for him—making clothes and boots, and processing the hunt.”

“Their participation was really the difference between life and death for Peary’s crews,” says Kaplan. “Whenever I look at a photograph of Peary’s crew, all you see are men in their fur garments. But if you’re in the know, you can see the women behind all of that. And that just has not been really recognized by Arctic historians.”

FOOD TRUCK FEVER

Above: In his book, The North Pole, Robert Peary included photos of Egingwah (left) and Ootah (right)—ages twenty-six and thirty-four, respectively—taken immediately after they returned from their 1909 trip to the North Pole.

Food trucks have been rising steadily in popularity across the United States in the last decade or so, and more and more have been seen in recent years throughout Maine. Many alumni will remember Danny’s on the Mall, which started selling hot dogs there in 1982, and other food vendors—including, for a time, some hot dog competition— have come and gone in that location. But food trucks can now often also be seen on Bowdoin’s campus. In the early days of the return to campus during the pandemic, when eating inside together was still unwise, food trucks allowed students to celebrate as a community in the time-honored way—by eating. They still offer a welcome way to eat outside, but they have also become beloved just because of the variety they offer: tacos, donuts, gelato, dumplings, pizza, cheese and charcuterie, falafel, meatballs, Nigerian and Colombian food, famous-in-Maine poutine, and (of course!) hot dogs.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 11

Archives

Campus Life

(EGINGWAH

PHOTOS:

AND OOTAH) PEARY-MACMILLAN ARCTIC MUSEUM; (FOOD TRUCK) ANDREW ESTEY

Inclusion

Welcome Here

On the second day of the fall semester, the Office of Inclusion and Diversity hosted an Ice Cream Social on Coe Quad. The event was open to the entire community, and offices from across campus set up tables and held informal conversations about how they are furthering the work of inclusion and belonging. Hundreds of new and returning students, staff, and faculty turned out on a picture-perfect day for numerous giveaways, including T-shirts printed on site and on demand and ice cream (and frozen whoopie pie!) from five different ice cream trucks.

Benje Douglas, senior vice president for inclusion and diversity, has more in store—he’s also holding lunches and conversation with staff and faculty and planning a series of videos. Topics will range from feeling welcome in Maine to feeling confused about the work of inclusion—and all are welcome.

“We’ll only make progress as a community if we’re all invested in the idea that ‘diversity work’ is every one’s responsibility,” says Douglas. “It would be great to have some people who are all in on this work, and some who might be a bit more skeptical. I’ll leave it to you to decide what camp you might fall in, though in truth many of us may be in both camps depending on the day or the topic.”

In December, the Office of Inclusion and Diversity will take over Smitty’s Cinema to host a family-friendly movie night for all employees.

Game On Tennis Triumph

TRISTAN BRADLEY ’23 became just the second Polar Bear in program history (joining Luke Trinka ’16) to claim the Intercollegiate Tennis Association New England Regional Championship, which he did on October 2 in Brunswick. With the win, Bradley qualified for the ITA Cup in Rome, Georgia, on the weekend of October 15–16, where he advanced all the way to the title match before finishing as the men’s singles runner-up.

12 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Forward

PHOTOS: (T-SHIRTS) JANIE PORCHE; (BRADLEY) BRIAN BEARD

Tristan Bradley ’23

Silk-screening T-shirts on demand.

TIM SOWA ’14

“All around the world, technology access and digital competency are markers of equity, working as either a tool to level the playing field or to further oppression,” says the economics major, who is working on a master’s in sustainable digital life at Tampere University in Finland and partnering with Gofore, a digital consultancy group, to enhance their ethical and sustainable practices. “I am very excited to apply what I am learning back into the world in a meaningful way.”

HANNAH SCOTCH ’22

The neuroscience major is conducting research on neuroplasticity at the Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Seville, Spain. “During development, there are crucial periods of synaptic growth and synaptic pruning, and if these do not occur correctly, major developmental problems may arise. Understanding what causes this plasticity to occur normally can help us understand why and how it goes wrong, providing potential avenues for treatment,” says Scotch, who became interested in the topic during her first neuroscience course at Bowdoin.

MAX

FREEMAN

’22

“I am fascinated by Israel’s traditions of remembrance,” says the English major, who conducted undergraduate research at Bowdoin investigating how digital technology has influenced our memory. The Illinois native is spending the year teaching English at Tel-Hai Academic College in Israel. “By listening to the stories of individual Jewish and Arab Israelis, I hope to learn more about the collective memories that connect us to our histories.”

SUSTAINABLE STYLE

Every year, Americans alone throw away 11.3 million tons of clothing—equaling around 2,150 garments each second, according to a recent report in Bloomberg. The fashion glut is leading to an environmental crisis, and a complementary ensemble of students— comprising the College House Cocurricular Committee, Bowdoin Fashion Club, and Bowdoin Sustainability—is working to do their part to reduce the global impact.

A recent clothing swap held in front of Quinby House allowed students to donate unwanted clothing in exchange for three items. The event combined a need to purge items that no longer spark joy and a desire to refresh one’s tired wardrobe with the goal of thwarting—or at least slowing down—the fast-fashion trend.

“A lot of people overconsume clothing and end up not using a lot of the items in their closet,” says Zerimar Ramirez ’25, one of the event’s organizers. “The swap produces a completely free and accessible way for people to be sustainable and intentional in the way that they engage with fashion and consumption instead of purchasing from fast-fashion brands or buying new clothes every other week.”

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 13

Campus Life

Academics

ILLUSTRATION:

For the past two years, students at Bowdoin received more Fulbright grants than at any other baccalaureate institution. Here, three of this year’s nineteen recipients share how they’re using the competitive award to find solutions to shared global concerns.

PHOTO

PETER CROWTHER

The Meddiebempsters are often described as the third-oldest all-male collegiate a cappella group in America, after the Whiffenpoofs at Yale and a second-place finisher to…some other group. As with many things Meddie, no one quite seems to know for sure what group that is. It’s a sure thing, however, that Miscellania, also known as “Missy,” is the oldest all-women a cappella group at Bowdoin. And, as it happens, both groups celebrated major anniversaries at Homecoming this fall. Congratulations, Meddies and Missy!

1st 10 to 12

Meddies and Missy Milestones 3,000 139 4 85 23 ILLUSTRATION: JON KRAUSE and Laurence Smith ’41. La Mer, This , , , Songs of Love , Meddielenium, Have Yourself a Meddie Little Christmas , , No Sleep in a Quiet , Little Black Dress, On a , Back in Black, No Boys Aloud, and Miss Us?

Common Good Campus Life

Harvest

THROUGHOUT THE YEAR, the Bowdoin Organic Garden offers various ways for students to taste the crops, learn preservation techniques, and get their hands dirty.

“College, especially at a place like Bowdoin, is so cerebral,” says Lisa Beneman, garden supervisor. “I think sometimes students come to the garden to breathe in the fresh air and the smell of the dirt and the smell of the leaves and have their feet and their hands on solid ground. It’s an exercise in mindfulness in some ways and meditation in some ways— and a way to get grounded in reality.”

As they—and any gardeners in the northeast— get ready to put all the plants to bed for the winter, we asked Beneman and Bowdoin head baker Joanne Adams to share a few ways to stretch out the fall harvest.

DRIED FLOWERS

Throughout the summer, the garden grows statice, lavender, globe amaranth, strawflowers, hydrangeas, poppy pods, and ornamental grasses, and the gardeners offer workshops to teach students how to properly dry flowers and to create wreaths to hang

in their dorms, bring home for the holidays, or give away as gifts. The trick, according to Beneman, is to clip the flowers when they’re at their optimum color, strip off the leaves, bundle the stems, hang them upside down until they’ve dried, then wrap them in paper and store them in a cardboard box until you’re ready for a cheer of color.

PICKLED VEGGIES

Students are invited to try their hands at refrigerator pickling, including harvesting cucumbers, carrots, green beans, radishes, and peppers from the garden and bringing them back to the kitchen for washing, chopping, and jarring in their choice of brine. “Vinegar is a powerful preserving agent, and the cold temperature of the fridge means you don’t have to worry about canning,” says Beneman. “It typically takes about a week or two for them to develop their flavor, and they’ll last for at least up to six months.”

PUMPKIN PIE FILLING

This year, the garden produced 200 pounds of sugar pumpkins, yielding sixty-three pounds of puree and thirty-five cups of seeds. The key to a good pumpkin puree, according to Adams, who has been cooking at Bowdoin for nearly twenty years, is to be sure to remove all the water. Adams typically steams the sliced pumpkins on a sheet pan with water for an hour and a half, refrigerates them overnight, scoops out the pulp, lets them sit overnight again, and then creates a puree, which she strains at least two more times. “If you don’t remove all that water, it ends up in the batter or pie filling and won’t thicken when it bakes,” she says.

FROZEN BASIL CUBES

“Pesto is an ever-popular menu item here at Bowdoin,” says Beneman. “We grow tons of basil all summer, and as we’re bringing in big basil harvests [fifty pounds at a time], dining services blends and freezes the basil with oil.” Olive oil is the classic choice, but any oil will work depending on the flavor you’re after. The combination allows for that fresh basil flavor year-round, and Beneman does the same thing at home, preferring half-pint jars to the more popular ice cube trays, and more of a paste than a liquid. “I have a heavy hand with pesto, so I like a thicker, larger quantity.”

GETTING OUT THE VOTE

“Bowdoin College had among the highest undergraduate voting rates in 2020, thanks to the way student leaders promote the tradition of civic engagement,” says Wendy Van Damme, associate director for public service at the McKeen Center for the Common Good, which administers the program.

Continuing that energy this year, Bowdoin Votes fellows Samira Iqbal ’23 and Lucas Johnson ’23 trained a dynamic team of more than twenty student volunteers. “Those volunteers have popped up all over campus this fall to encourage students to vote,” says Van Damme.

As Iqbal and Johnson pointed out to students in an email, the electoral stakes were high this year, with some 435 US House seats up for grabs, along with thirty-five senate seats and many governorships and other key state offices.

Bowdoin Votes provided students with information about registration, voting locations, deadlines, and absentee voting. The program also helps students learn more about what’s on the ballot and how to be involved in civic action during and between elections.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 15

PHOTO: MICHELE STAPLETON; ILLUSTRATION: JING JING TSONG

Flowers drying in the Bowdoin Organic Garden barn.

On Stage

Our Town, Any Town

Theater department embraces universal themes in its adaptation of a Thornton Wilder classic.

OUR TOWN is a “simple but profound” play that explores universal themes that speak to all of us, says Professor of Theater Davis Robinson. Written in 1938, Our Town is set in the fictional New Hampshire town of Grover’s Corners in the early years of the twentieth century, following the lives, loves—and sometimes the deaths—of a number of characters as time passes.

“When I first encountered the play, I saw it as a quaint New England tone poem about life at the turn of the last century,” says Robinson. This impression changed, however, when he went to a lecture by the playwright Edward Albee.

“Albee described Our Town as the best American play ever written, which shocked and surprised me. So, I went and reread it in a new light, and it really struck me how simple yet profound the play is.” Wilder explores universal human themes by checking in with the same group of characters over a twelve-year period, said Robinson—themes like love, loss, and the ephemeral nature of our existence. “The play prompts us to consider our everyday lives against the universal indifference of the stars and asks how much of our world will be here a thousand years from now,” he adds.

Robinson says one of the aims of his production was to reflect the diversity of the Bowdoin campus and disrupt the idea that Grover’s Corners is seen as just a white space or a New England space. “It’s about ‘something way down deep that’s eternal about every human being,’ as Wilder says.”

College Life

SEASON TWO

The second season of the Bowdoin Presents podcast launched in October. After a first season that explored issues of democracy, the second season takes listeners back to the classroom, through a series of episodes featuring faculty and others talking about the work they do inspiring, teaching, and sharing knowledge with the Bowdoin community. Guests join journalist Lisa Bartfai in conversations ranging from art and oral tradition in central Africa to the volume of information and how it travels—and much more. The series, along with an archive of last season’s episodes, can be found on Google Play, Apple Podcast, Stitcher, Spotify, Amazon Music, and Simplecast. Or go to bowdo.in/presents to listen.

16 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Forward ILLUSTRATION: BRIAN STAUFFER

Sound Bite

“The environment is not a passive backdrop for human lives. It’s not someplace over there. It’s all around us, an active force that has profoundly shaped us all, past and present—whether we realize it or not.”

—PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES CONNIE CHIANG, IN HER CONVOCATION 2022 ADDRESS “CULTIVATING OUR COMMON NATURES”

Student Life

CLOSE TO HOME

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion in February, more than a million Ukrainians have landed in Germany after fleeing their homes. Lionel Welz ’24 felt compelled to help alleviate some of the despair and displacement and spent his summer vacation volunteering for Münchner Freiwillige, a nonprofit organization that helps refugees find housing in his hometown of Munich.

As part of his assignment, the neuroscience major spent ten-hour shifts calling German families asking if they would take in Ukrainian refugees for a few days, weeks, or even months. While he could not always understand the Ukrainian refugees he was working with, he did eventually pick up some important phrases, such as: “Do you have a passport?” and “What’s your ID number?”

He also picked up several stories of violence and mourning. The most memorable involves a newly orphaned ten-year-old boy who fled his war-torn country with his uncle. Welz spoke with the boy, who had begun learning German on the language app Duolingo upon arriving in Deutschland and managed to enroll himself in school.

“It was very difficult for me to see this boy who had just lost everything,” Welz said. “He had to mature within two weeks. He had to figure out life for himself and his uncle, while simultaneously coping with [the fact that] both of his parents had been killed a couple of days apart.”

Now back at Bowdoin, Welz is grateful for the three years he has spent studying Russian, which he was able to put to the test, and for the Russian department at Bowdoin, for openly talking about the war and promoting the study of Ukrainian cities and cultures in the classroom.

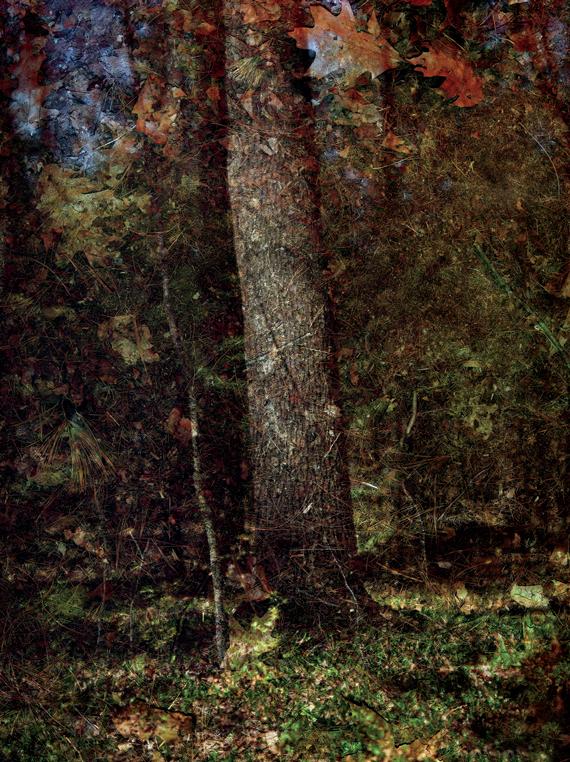

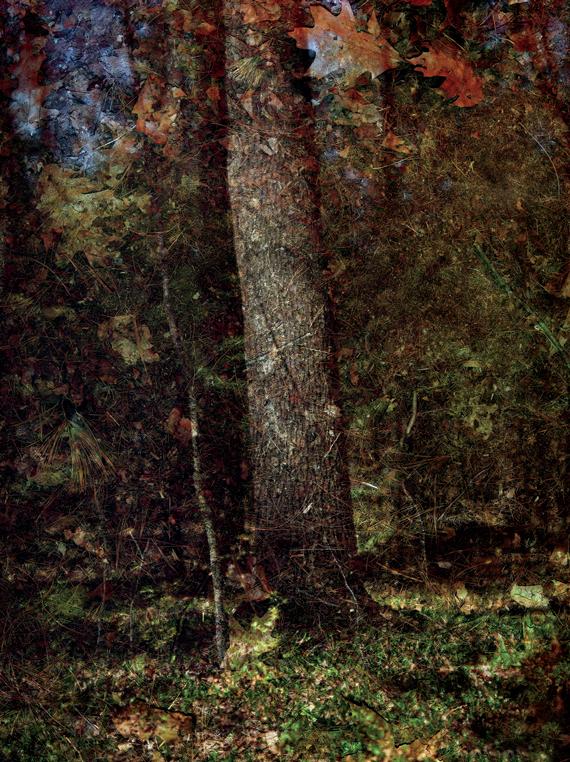

In Beauty, a Benefit

To celebrate his 50th Reunion and help raise money for a Bowdoin scholarship, renowned artist Abelardo Morell ’71, H’97 has donated two works that depict ordinary campus scenes—a tree and a vase of flowers—in unique and arresting ways.

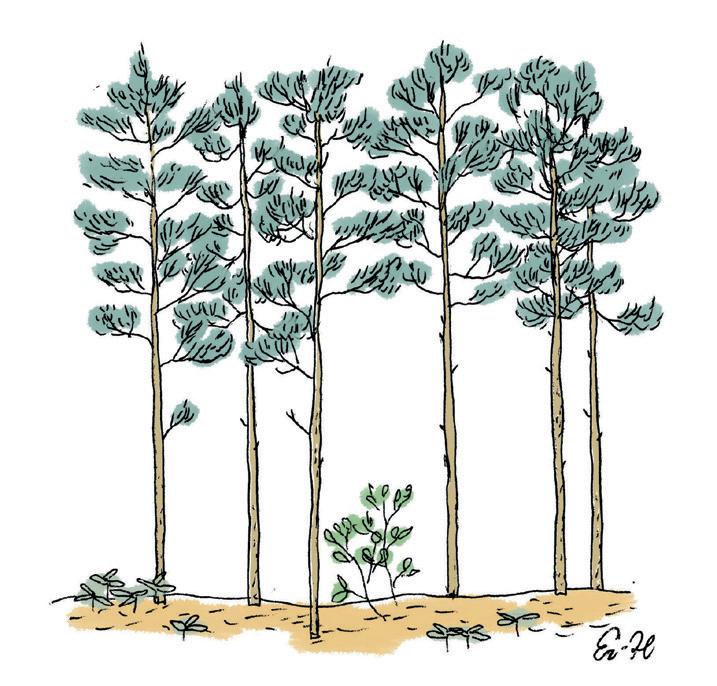

The prints are being limited to an edition size of 150, ensuring their value in years to come, and can be purchased at the Bookstore or at bowdo.in/morellprints. Last April, Morell and his wife, Lisa McElaney ’77, visited Bowdoin seeking inspiration for the artworks. They explored familiar places like Hubbard and Massachusetts Halls and the College archives. But when they returned for a second time in May, Morell settled on a subject not on their original itinerary. He was drawn to the Bowdoin Pines, a preserved old-growth forest behind Federal Street. To make his striking image of a pine tree, Morell used a “tent/camera,” a device he invented that can project nearby scenes via a periscope onto the ground of a light-proof tent.

Morell’s other new work for sale, “Flowers for Bowdoin,” is reminiscent of his well-received series Flowers for Lisa. For this piece, he made several exposures of shifting flower arrangements. “When put together, these disparate views form wonderful explosions of color, texture, and painterly abstraction. I think that this photograph contains feelings of celebration and exuberance—not unlike the sort of joy surrounding many reunions,” Morell said.

Morell was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1948. He and his family left the country in 1962 and settled in New York City.

Above: “Tent Camera: Tree Trunk in the Bowdoin Pines” (left) and “Flowers for Bowdoin” (right) by Abelardo Morell ’71, H’97.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 17

(WELZ)

PHOTOS:

COURTESY LIONEL WELZ ’24; (PRINTS) COURTESY HOUK GALLERY, COPYRIGHT ABELARDO MORELL

Common Good

Lionel Welz ’24

Honoring the Animals

In caring for a world of creatures— from exotic pets to penguins, from snowy owls to sea lions— veterinarian Carl Spielvogel ’13 has learned a few things.

I KNEW I wanted to become a wildlife and aquatic veterinarian in high school. I spent summers volunteering for the New England Aquarium animal rescue team and interning at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and was inspired by veterinarians who used their talents to help animals.

I loved my time at Bowdoin. I was a bio chemistry major but took classes in the history of the Civil War and music classes in audio pro duction. Through a connection in the Bowdoin network, I spent a summer in China studying an invasive tree species on the Wolong Giant Panda Reserve—one of the most eye-opening experiences of my life.

I remember a biology class where Professor Bruce Kohorn used his nondominant hand to draw cellular structures because he had acciden tally shot the other one with a nail gun. He taught me and so many Bowdoin students so much.

My friends included students from all back grounds, ethnicities, and sexual orientations— people with a variety of interests, opinions, and career aspirations. During an average meal, I would sit at a minimum of three tables, chat about classes and social life, talk curling with my team I helped found, and do some pepper flipping (if you know, you know).

After graduating, I took a year off before applying to veterinary school, and then moved to Montana to work the night shift at a cattle ranch called the IX, where I helped manage a group of pregnant two-year-old Angus heifers and assisted in their deliveries in temperatures as cold as twenty below. At IX I learned that good ranching involves a significant amount of data collection and analysis. The ranchers monitored soil nutrient levels and considered

the genetics of cows and bulls used to rear new cattle. They monitored birthing outcomes and complications, and they graded the mothering abilities of cows to help guide the genetics of the fathering bulls. We even did our own cesarean sections because the nearest veterinarian was a multiple-hour drive away.

The cowboys I worked with followed a strict moral code and taught me the importance of maintaining appropriate welfare for their

cattle and working horses. Despite being one of the largest ranches in the Americas, they did not use motorized vehicles like ATVs to herd cattle, saying that ranching with horses is more honorable and less stressful for the cattle. The wildlife appreciated that too; during cattle drives through the mountains, elk and deer would travel with the herd and sometimes seem close enough for me to touch. The ranchers taught me to shoot high-caliber rifles, and I

18 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU ILLUSTRATION: KEN ORVIDAS Column

learned the necessity of staying on your horse, especially when you are crossing a river in freezing weather.

Near the end of calving season, I woke up in the machine shop where I slept and checked my email, finding a congratulatory message from the dean of admissions at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. I finished up at the ranch and started veterinary school in 2014.

Vet school was unlike anything I had ever experienced—even at Bowdoin. There were so many species and biological systems to learn, and we had to know the exact mechanisms by which medications are absorbed and metabolized differently between species or even differently between breeds. We had to learn which medica tions are safe for different animals, breeds, and age groups, and anatomic differences detected on X-rays or differences in laboratory test results between animals.

I was awarded a scholarship to perform research at the New England Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Hospital on the use of ventilators in cold-stunned sea turtles and delivered a presen tation on my research, which I later finished and published, at an International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine conference.

That conference was the first I ever attended, and at the opening dinner, I sat next to Juli, the woman who would much later become my wife. Juli remembers me talking a lot about shrimp farming.

I left vet school with a degree and a license to practice veterinary medicine, a cat my classmate found on the street named Snoopy, and a kitten from a Philadelphia dumpster that another friend had rescued, named Woodstock. Together, we moved to Massachusetts, and I started work at

a one-year internship in a specialty and emer gency animal hospital outside of Boston.

As part of my internship, I spent a month at the New England Wildlife Clinic and the Aquarium of the Pacific. At the clinic, I performed my first-ever surgery on a wild bird and got my first experience as a doctor treating a variety of exotic and wild animals. At the aquarium, where Juli and I had the opportunity to work together, I gained experience caring for animals ranging from penguins and sharks to seals and sea otters.

After my internship, I was accepted to a residency in Buffalo, New York, where I worked in a private practice specializing in the care of birds and exotic species. There I learned to treat parrots, snakes, turtles, frogs, rabbits, guinea pigs, emus, falcons—you name it. I also worked for a wildlife hospital, where one of my favorite patients was a wild female snowy owl whose wing I repaired after she was hit by a car.

I also worked part-time, on my days off, for the Aquarium of Niagara, initially helping care for their penguin colony. By the end of my residency, I was providing care for their entire collection, and I’m now also in charge of their animal welfare and research. I also work as an emergency vet for dogs and cats at the Greater Buffalo Veterinary Emergency Clinic.

I now know a great deal about animals and birds. But I’ve learned that my work is not just about their care—it is as much about their humans. I have treated eighty-plus-year-old parrots that have been with their now-elderly owners since they were children. I have worked with police dogs and their canine handlers, who rely on each other to safely execute their duties, and I know an army medic who owes his life to a dog that shielded his unit from incoming bullets in Afghanistan.

As an emergency veterinarian, I am regularly confronted with difficult, sometimes combative owners. Many don’t understand that an easy and cheap fix is not always possible. Some animals don’t get the care that they need, whether their owners can afford it or not. I also see owners who struggle to make ends meet and yet take out thousands of dollars in loans to prolong the lives of their animals. I face moral dilemmas on a daily basis, and it can be difficult for me to distance myself.

Extreme staffing shortages amid an unprec edented increase in animal ownership means that I regularly work twelve- to fifteen-hour shifts as the only doctor at the emergency room. I perform critical care and surgeries on very sick animals while dealing with an ER often bogged down by noncritical conditions or diseases that could have been prevented by routine care and vaccinations. I also have to euthanize animals on a regular basis. There is a cumulative toll to the sorrow and difficulties that we encounter.

But the positive aspects far outweigh the neg ative, and writing this column reminded me of people who helped me choose my path and pur sue my dreams. I am grateful for my friends and family, and the many professors, scientists, and animal care professionals I have learned from.

First table-mates and then colleagues, Juli and I got engaged on a beach in California, and I managed to convince her to move to Buffalo. We were married in September 2021 at her parents’ home in Durango, Colorado, in what was my first reunion with many of my Bowdoin friends. We now work together at the aquarium. We bought a house this year and are expecting our first child (a boy) in March. I am so excited to be a father, and I have been spending every minute of my free time scraping, hammering, or painting, making the house perfect for our new baby. We love western New York and enjoy camping, kayaking, fly-fishing, and hiking along the many rivers, gorges, and waterfalls in the area. I can’t wait to introduce my son to the many creatures who share this world with us.

Carl Spielvogel ’13 works at the Greater Buffalo Emergency Veterinarian Clinic and the Aquarium of Niagara. At Bowdoin he majored in biochemistry and founded the curling team.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 19

I now know a great deal about animals and birds. But I’ve learned that my work is not just about their care—it is as much about their humans.

Claudia Marroquin ’06 is a Bowdoin success story. A first-generation student who came to the US from Guatemala with her mother and sister when she was young and grew up in the Koreatown section of Los Angeles, she joined the Office of Admissions in the fall of 2010, became dean in 2021, and along the way has worked to reduce the barriers that exist around access to higher education. We spoke with Marroquin—the first Bowdoin graduate to lead the office of admissions in more than thirty years— about the challenges of her work, the importance of kindness, and the role her personal story plays in assembling each Bowdoin class.

INTERVIEW BY DOUG COOK PHOTOGRAPHS BY SÉAN ALONZO HARRIS

BOWDOIN: Why is it important to convey your personal story when you interact with prospec tive students?

MARROQUIN: It’s been important to share my own experiences, my background, my upbringing— partially because students may not envision someone in leadership to have had the same experience. It’s easy for students to be afraid, and they might feel like they’re the first ones going through this. For me, there’s an ability to connect with students around that, but it’s also important for those who may not share any of my experience to know that they will end up interacting with folks who have a very different lived experience.

BOWDOIN: What would be the most surprising thing readers might learn about the admissions process here at Bowdoin?

MARROQUIN: Counselors often ask if we actually spend time getting to know these young people. I think there are assumptions about the work, that there are formulas, that it’s mechanical, that we go through so much so quickly. Yes, we do a lot of work in a finite amount of time, but we all care not only about the College, but also about these young students and about getting to know them as best as we can. I think the thing that surprises people the most is that I’ll remember things about them, especially when I welcome them at the beginning of the academic year. Over the years, the admissions office has prided itself on the fact that it’s not just a process for us. We take it personally. We treat everyone with respect, and we try to learn about their lives. We feel a responsibility to

connect with students and also to see them for who they are.

BOWDOIN: What informs the process for assem bling a class? What is the College looking for in a student and in a class as a whole?

MARROQUIN: Part of our review process is looking for students who are prepared for the academic experience. We know that college is going to be hard, and they will experience moments of failure. But at the end of the day, we really want them to grow and be successful during their time at Bowdoin. So we are looking to make sure we have students who are prepared for the rigors here, and who also want to be in this type of environment—who know that when you’re in a class, you can’t hide and you’re going to be expected to share your ideas. And that’s not every student we’re reviewing. I also think a formula for success at Bowdoin has a lot to do with the intangible qualities that a student brings. You can be incredibly smart and still struggle at Bowdoin if you’re not motivated, if you’re not willing to take risks, if you’re not willing to be in a really engaged community. We also often have conversations about upholding the values of Bowdoin, while giving ourselves the space to really create a new Bowdoin—to help the College move in the direction that it’s looking to go in the next few years. This can be both in terms of diversity at the College, and also the “intellectual fearlessness” and ability to embrace uncomfort able ideas and concepts that Clayton [President Rose] talks about. Yes, academics are always really important, but so are the character pieces around how a student is actually going to take advantage of everything here and what they will put into the experience. Those matter quite a bit for us.

BOWDOIN: What is the most important advice you have for young people as they think about applying to the College? When should that process begin?

MARROQUIN: I always tell students they’re going to get asked tons of questions from people they know about where they’re applying, what they want to major in, what they want to have as a career, and so on. As they’re thinking about

22 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

W

“We treat everyone with respect, and we try to learn about their lives. We feel a responsibility to connect with students and also to see them for who they are.”

those questions, they should really be thinking about what brings them joy and fun and plea sure, because they’re going to end up spending a lot of time pursuing their goals. If they want to become a doctor, they’re going to spend a lot of time in a lab. They’re going to be spending a lot of time studying, and they have to actually really love not only the chemistry and the biology pieces of it, but also the human interactions. I always tell students to not just think about the title, but also about the activities that are actually bringing them joy. Because when you start to mix those two together, that’s where you end up being successful not only in your academic space, but also hopefully as an adult in day-to-day life, when things can be really hard.

BOWDOIN: Bowdoin talks a lot about character and kindness as among the important qualities it looks for in an applicant. How do you measure these?

MARROQUIN: There aren’t necessarily rubrics to measure kindness. The way we seek it out and evaluate it in the applications is really in the empathy and awareness students have—they can see beyond themselves and recognize that whatever they might be struggling with or facing in their current life, their viewpoint isn’t the only one. I keep coming back to these same pieces that demonstrate a student who has kindness, that they can see the failings and weaknesses, but also the strengths of others. And they can have these poignant moments of recognizing that someone who they had preconceived notions about is actually a human being. That is at the core of kindness—having empathy and seeing beyond yourself.

BOWDOIN: You’ve become a champion of removing barriers for students who might not otherwise consider Bowdoin an option—things like dropping the application fee for first-gen and aided students, in addition to need-blind, no-loan admissions. This is personal for you.

MARROQUIN: It is, and I think it’s been not only a mission of mine, but for everyone who works at Bowdoin. We see ourselves as being able to provide opportunity, even when a student may not have considered an experience like this for

themselves. I think about my own experiences growing up when I read applications and recruit students. Without financial support, I would never have been able to even dream about college. I remember when I was seventeen working with an organization in L.A. and being encouraged to apply to ten schools that were outside of California, along with the California schools. The cost of each of those applications easily added up to $700, if not more, and my mom made about $28,000 a year. There was no way I would’ve been able to apply to the schools that I did, had I not been provided fee waivers or had someone tell me I could actually get a fee waiver. For me, it always does go back to thinking about how I navigated this process and some of the assumptions that I made, and thankfully having advisors at that point who told me, “Actually, no, there are other ways.” To change a process or a policy to make it more inclusive and to allow students to dream a little bit is definitely a personal thing for me.

BOWDOIN: The College announced this summer that it was expanding need-blind admissions to international students. Why is this important?

MARROQUIN: At the College, we are constantly talking about equity and making sure that we are looking closely at longstanding policies and really questioning them. Extending need-blind admission to international students was one policy that several of us in the office had wondered about over the years, and it became even more of a top priority for admissions as we looked at how interconnected the world is, the challenges international students faced during the pandemic, and how college can truly be an international experience. Trying to ensure that we treat all of our students the same in the admissions process really became a focus for me this past year.

BOWDOIN: Access and equity are priorities of From Here, the College’s ongoing comprehen sive campaign. That’s got to be a big boost for admissions.

MARROQUIN: There are so many conversations and articles around the cost of college and how

unaffordable it is for so many families, and how it’s becoming more and more unaffordable. We’ve always prided ourselves on having tremendous financial aid for students and their families who need it. Whether they’re very low-income or middle-income families trying to make things work, the work of the campaign allows us to continue to educate students from all walks of life. The promise of a Bowdoin education has long been that if you have the motivation and the willingness to put in the effort and have earned your place at Bowdoin that we’ll be able to support you. I think the other big piece around equity is that the experience students have on our campus should not be limited by their own personal backgrounds. One way we’ve tackled that is to remove the summer earnings requirement for students under a certain income level. We know that they’re already working incredible amounts, often to support their families, and we don’t want to burden them with an extra responsibility. Support from the campaign helps us expand what we are able to do.

BOWDOIN: Comprehensive aid is another part of the campaign. How does that help?

MARROQUIN: When students and families think about the cost of college, it’s usually tuition, room, and board. The things that they’re going to be billed for. But we know that college is about so much more than that, and compre hensive aid can help with things like allowing our students to take unfunded or underfunded internships, to pursue fellowships, to have the ability to study abroad and know that the cost is not going to limit and prohibit them from pursuing an important academic interest. It also extends to emergency situations where a student may need to go back home because of a family member’s unexpected surgery. Comprehensive aid means they don’t have to choose—they can actually do that. It is about the opportunities that prepare them for success beyond Bowdoin, but also for life experiences.

BOWDOIN: You mentioned earlier that the pan demic was especially difficult for international students, but of course, it impacted students

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 23

everywhere. Are you at all concerned about students’ preparedness for college, given the challenges they faced in high school during the pandemic?

MARROQUIN: Yes, absolutely. I think there are a couple of concerns. There’s the inequality in different school systems. There are some students who spent two years completely in a virtual space where they may not have been able to interact with their teachers and peers very much, and where the curriculum just had to be truncated to get them through and meet the requirements. But there’s also the personal loss students may have experienced, the insecurity, the anxieties, and the ability to be a kid and to have fun. Every year something happens in

the world that forces students to grow up a lot faster. I think this generation of high school students had their entire high school experience upended, and that’s going to continue for years as elementary and middle school students enter high school. Students who were transitioning into middle school, missed out on some social interactions that might really be valuable, or may have lost a parent early on in life. Preparation for college isn’t just about the academic piece. It’s really more about the amount of risk-taking a student is willing to take, given all that they’ve had to take on in the last few years.

BOWDOIN: On an institutional note, another result of the pandemic has been that many col leges and universities that previously required

24 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

Marroquin talks with biology major, education minor, and admissions office student worker Rory Kliewer ’24.

standardized tests have suspended or elimi nated that requirement, something Bowdoin did fifty years ago. How has that changed the admissions landscape?

MARROQUIN: In some ways it’s made things more complicated, but I also think it has made people realize that who you are as a person matters way more than the numbers. This past year in particular, we saw—even in our pool—students actually being more open and more vulnerable in their applications. There was a lot more expression of curiosity and thinking about larger issues that were taking place both in the world and in their own lives. I think there’s this tide that has finally changed, or is changing, where students recognize that who they are matters way more than a number, and that there’s only so much a test score can do for you.

BOWDOIN: Traditionally, Bowdoin and other New England colleges have drawn most of their students from the Northeast, a region where demographers expect a decline in young people. How is Bowdoin adapting to that reality?

MARROQUIN: Thankfully, we adapted to that reality years ago. We travel across the country and the world to recruit students, never forget ting, though, that we are an institution in Maine. We have two admissions officers who cover the state of Maine and encourage incredible, bril liant young people to stay within the state. We need them, but we also realize that, as a liberal arts college, we are designed to recruit students from all over. Most of our admissions officers have had a little bit of New England territory, but everyone has territory beyond New England. That makes us really flexible and adaptable and

truly versatile in the ways we can talk about the experiences that students are having at Bowdoin and understand what students are experiencing in their own communities.

BOWDOIN: What is Bowdoin doing about the trend of young women outpacing men in appli cations to college?

MARROQUIN: When we’re going out and recruit ing at different schools, we try to target places that we know have more male enrollments. Part of that is that young men sometimes aren’t, in some communities, given the opportunity to really think about education because they are focused on supporting their families and going into the workforce. But there’s the other piece too of the tables having turned. Bowdoin was an all-male institution until the ’70s, and there was intentional work to recruit women at that point. At the end of the day, we are looking to have the best students for Bowdoin here, and the amazing talent within our female applicants cannot be ignored. College-going trends are something we constantly think about, and it is worrisome that there are far fewer males applying to college. And it’s not just to Bowdoin, obviously. It’s a higher-ed issue, and it’s something to keep an eye on.

BOWDOIN: What is the most rewarding part of the work?

MARROQUIN: Getting to meet the students—by far. This year, I’m super excited because I’m going to be a Cub Connector. It’s a new program that residential life has introduced. So I will have that opportunity to get to meet with a floor of students more regularly and get to know them. Students are what make this work so rewarding

and bring me so much joy. There are many alumni now who have become friends as well. They were students I recruited, and I know so much about their lives and their families now. Being a part of their lives has become something that’s just really important to me.

BOWDOIN: What are your near- and long-term goals for admissions at Bowdoin?

MARROQUIN: Last year, I would have said to steady the ship coming out of the pandemic, and there’s still a piece of that happening. A lot continues to change in the world. This upcoming year, there are changes with financial aid and debt forgiveness that was just passed. We’re all waiting to see what happens with the Supreme Court decision with Harvard and UNC. So there will be the things that are out of our control that we are shifting and adapting to and trying to uphold Bowdoin values in the way we do our work in a new reality. As an alumna, I am fiercely proud of this place and so proud of the things Bowdoin has done for students. I want Bowdoin to be known even more across the country, across the world. People should know about institutions that are striving to make education more accessible, so there’s the aspirational goal of wanting Bowdoin to be a household name. Then there’s the fine-tuning of things. Every year we learn from our students about the world they’re going into and how their needs are changing. So we look at how we can continue to best meet those needs while continuing to grow and evolve as a leading college in the twenty-first century.

Doug Cook, director of communications, manages media relations and oversees content on the Bowdoin website and the College’s official social media channels.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 25

“To change a process or a policy to make it more inclusive and to allow students to dream a little bit is a personal thing for me.”

Ed Burton ’91 pieces together information in painstaking, promise-fulfilling searches for the soldiers who never came home from war.

BY DAN CARLINSKY ILLUSTRATIONS BY GREG BETZA

BY DAN CARLINSKY ILLUSTRATIONS BY GREG BETZA

GROWING UP with parents who were longtime faculty at the University of New Hampshire, Ed Burton ’91 knew he’d go to college and then to graduate school, because what else would he do? He figured his field would be history, but that’s about as detailed a plan as he could have pre dicted, since, as it turned out, there were a few zigs and zags along the way. Happy zigs and zags.

True to his very rough forecast, Burton grew up to become a historian, the kind who extols the joys of spending days burrowing into boxes of long-dormant, sometimes fragile files in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland— which some call “the nation’s memory,” but which he calls “a Disneyland for historians.” Still, his unplanned road to the work he vari ously describes as “cool,” “incredibly fun,” and “the most amazing job anyone can ever have” was anything but direct.

“My parents were mathematicians,” he begins, “but in our house, history books always outnum bered math books. I knew I wanted to major in history or government in college. I remember, in my senior year of high school, sitting on the living room floor with pages from The Fiske Guide to Colleges ripped out and sorted into piles: highly ranked history departments and highly ranked government departments. Bowdoin turned up in the categories I wanted most.”

He focused on Latin American history, then ancient history; he wrote an honors thesis on the First Crusade. When his Bowdoin classmates were spending a semester or two abroad, Burton stayed in Brunswick. Today, he mock-gripes about missing out: “My roommate, my friends—everyone was doing something exciting but me.”

To make up for that, he enrolled in a mas ter’s program at Lund University in Sweden. (One selling point was the cost of tuition: $12 a term.) He had a Swedish-American grandfa ther, so, he says, “when my household watched the Olympics, once the American team was knocked off, we rooted for the Swedish team.” But he had never been to the country and didn’t know the language.

“I copied an entire Swedish-English dictio nary onto flash cards with an inkjet printer: nine shoeboxes of four-by-six index cards, each holding 1,250 cards,” he recalls. “For four

months after graduation, I spent between four and ten hours a day in the front yard, listening to Radio Sweden on the shortwave and flipping flash cards. I always think anything worth doing is worth overdoing.” As it turned out, the over doing came in handy.

Burton explains: “Lund was thinking of start ing an English language history master’s pro gram—I was their guinea pig. But by the end of my time there, most of what I had to read for courses was in Swedish. Plus, I could manage in the grocery store. I think the time I put in with all those index cards was well spent.”

AS THE ONLY AMERICAN in the department, Burton says, “I was others’ exotic foreign exchange student.” By default, he became the resident expert on American history, but he studied Scandinavian history and wrote a master’s thesis on neutral Sweden’s relationship with NATO during the Cold War (“closer than anyone cared to admit at the time”). When he was done, he stayed in Sweden and entered a doctoral pro gram at the University of Gothenburg. There, he again switched his academic focus, thanks to a chance event.

“One day I was in the hallway, opening my mail,” he recalls. “I heard the chairman: ‘Burton! We have a problem!’ It seems a lecturer had gone to Jerusalem, had a religious conversion, and decided not to come back. They needed some one who could talk about nineteenth-century US history for a few hours. I had never studied American history at Bowdoin, but I did the lecture, it went over well, and the department’s leadership decided to use me again.

“A lot of the faculty were students in the 1960s, pretty far to the left—some raised money for the Viet Cong—so the chairman insisted that I teach a class on the Vietnam War. I was nominated for a university-wide prize for best lecture. Nobody in the department had been nominated before, so the department leader ship was happy. I was nominated again. And again. And again. I gave that class something like seven times.”

So, having become something of an acciden tal expert on the Vietnam War, Burton chose as his dissertation topic how Swedish-language immigrant newspapers in America reported and

28 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE FALL 2022 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

commented on that war. As part of his research, he visited an archive at the Swedish Foreign Ministry and read letters sent to the Swedish gov ernment by Americans during the Vietnam era.

“I sat down in one of those little carrels,” he remembers, “and they brought me three large carts packed with file after file of letters from worried moms and dads from across the US. Each one was a variation of ‘Dear Mr. Prime Minister, We understand your country is opposed to what our country is doing’—Sweden had just opened relations with Hanoi—‘Can you tell us what happened to our son?’ Hundreds, if not thousands, of letters. I became really interested in prisoners of war and the missing in action. I think it’s impossible to read letters like those and not be terribly moved.”

Swedish academics, according to Burton, take their time with PhD programs (he spent eight years on his) and take the dissertation very seriously. “In Sweden,” says Burton, “if you’re ABD—all but dissertation—you’re at the starting gate. You’re nowhere. The dissertation is everything. At my defense, there were three hundred people in the audience. And after you’re approved, you’re expected to put on a banquet for everybody. I was an American, so I served hot dogs.”

After earning his degree, Burton did what most PhD recipients do: He scouted around for teaching jobs. He first lectured in American his tory at the University of Aberdeen, in Scotland, then came home to teach at UNH, Franklin Pierce, and the University of New England. In 2009, he saw a listing for a historian position with an office in the Department of Defense (DoD), a forerunner of his current employer, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), which is the US government bureau that searches the world for military personnel who didn’t return from war.

THE DPAA COUNTS more than 81,500 Americans still missing from conflicts stretching back more than eight decades, including nearly 1,600 from the Vietnam War, some 7,500 from Korea, and a sobering 72,000 from World War II. More than half are thought to be lost in deep water and thus nonrecoverable, leaving about 38,000 for possible pursuit. They may have died in a plane crash, their remains now hidden or scattered. They may have been killed in a ground battle or POW camp and simply left in a makeshift grave, now overgrown, whether in a Vietnamese jungle or in a German forest. They may have been buried in an American military cemetery as “unknown.”

The goal is to locate and identify them all— for their families, for the country—to make good on a pledge to leave no soldier behind. Thus the DPAA’s motto: “Fulfilling Our Nation’s Promise.”

The agency is headquartered in Virginia, near the Pentagon, with a large forensic identi fication lab in Hawaii. It has satellite operations at Air Force bases in Nebraska and Ohio and calls on other DoD facilities, including the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Delaware. With a staff of 725—half civilian, half military—the DPAA sends teams around the globe to methodically sweep sites with metal detectors and to sift soil, first for a piece of a plane wing or a parachute buckle, then possibly for human remains to be returned home and analyzed in hopes of identification.

The work relies on a wide variety of special ists, among them forensic anthropologists and odontologists, archaeologists, mountaineers, divers, explosive ordnance technicians, combat medics, translators, genealogists, and—to set each case in motion—historians, who search out every record, every clue, every bit of data findable, in the hope of leading to recovery and identification of those who never came home.

DPAA historians scour unit records, mission reports, individual deceased personnel files, missing air crew reports, witness statements, cemetery records, and other archival docu ments. They search the internet and read old newspaper stories, memoirs, and oral histories. They communicate with families of the missing and with amateur researchers and local officials in battle and crash zones around the world.

Over time—often years—as information is painstakingly gathered, the historians con stantly churn through everything again and again, looking for the piece of new information that will make a dossier that can warrant the exhuming of a war casualty buried without identification or, in cases of the missing, an overseas investigative mission and a possible all-out recovery effort. Cases once considered beyond hope are revisited repeatedly in light of improvements in DNA technology, isotope analysis of bones, and other lab processes.