WHAT IS A CLOUD?

Artist James Michalopoulos ’74 has been influenced by the colorful, confounding streets of New Orleans, and in turn has influenced them.

Coeducation reflected change in our wider society, but it also sparked it, making Bowdoin better in the process.

Metaphors serve as shortcuts to understanding—but they’re not always benign. A conversation with professors Eric Chown and Fernando Nascimento.

The senior vice president for development and alumni relations talks about creating a welcome space for all alumni.

5 Space for Everyone: Bridget O’Carroll ’13 creates— and represents—community.

6 Job Search to Soul Search: Bowdoin’s Sophomore Bootcamp grows bigger and more ambitious.

7 Dine: A tuna poke recipe by chef Ian Hockenberger ’89.

8 A Look at the Lions: A 3D scan inspires this “Did You Know?”

17 NESCAC Express: Jake Adicoff ’18 heads to his third Paralympic Games.

20 The Courage to Fall in Love: Mai Libman ’00 had a rocky relationship with Bowdoin, and it wasn’t until many years after graduation that she reconnected and found her community here.

49 Sam Chapple-Sokol ’07 talks cultural diplomacy.

52 Meredith Maren Verdone ’85 on slowing down to take a breath.

55 Amy Steel Vanden-Eykel ’99 on being a good leader—and teammate.

56 Sherrone Torres ’12 talks about connecting with the world.

4

The Bowdoin Nordic ski team—including Elliot Ketchel ’21, center front, bib number 4—opened the 2022 season with a 20k freestyle mass start at the Colby Carnival on January 14. Predicted weather conditions for the second day of racing at Quarry Road in Waterville necessitated kicking the season off with a 20k distance, which is unusual. It was also the first time that the women raced the same distance as the men in EISA competition— the previous women’s standard was 15k. The Bowdoin women finished third overall, led by an outstanding performance from Renae Anderson ’21, and the men ended the day in seventh place, led by Ketchel.

Photo by Brian Beard

Photo by Brian Beard

I read your cover article most intently—in particular, your milestone dates. I think one was missing—1962. In that year, my mother, Bernice Spring Engler, was the first woman to receive an earned degree from Bowdoin. The National Science Foundation established a four-year summer program at Bowdoin, among others, to upgrade teaching in STEM. In 1959, my mother, a math teacher at Brooklyn Technical High School, enrolled and [later] received a master’s degree in [1962], along with [one] other woman (she is the first woman because her name was earlier in the alphabet).

Stephen EnglerEditor’s note: A version of the above photo of Bernice Engler G’62 and Carolyn Mann G’62, the first two women to receive Bowdoin degrees that were not honorary, appeared on page 15 of the Fall 2021 issue. Stephen is right that we should have included 1962 in the timeline that accompanied “The Women Before” story in that issue.

“The Women Before” was of special interest to me, as my mother, Marion C. Holmes, was one of those faculty wives who taught mathematics when some professors were drafted into military service during World War II. The only proof my mother had of having taught at Bowdoin was a tiny article in a Boston newspaper.

Like Susan Jacobsen ’71, I was determined to go to Bowdoin. But when I was ready for college in the fall of 1953, Bowdoin was

not ready for me. My three older brothers graduated from Bowdoin: Julian C. Holmes ’52 and twins Peter K. Holmes ’56 and David W. Holmes ’56. I headed off to Oberlin’s class of 1957.

Janet Holmes CarperThank you for the article by Tom Putnam ’84 reflecting on the enduring influence professor Paul Hazelton ’42 and Dory Vladimiroff H’94 had on him and, in turn, the influence he

facebook.com/bowdoin

passed along to Leroy Gaines ’02. I share Mr. Putnam’s gratitude for all that Paul Hazelton was able to provide me during my years at Bowdoin. Paul still speaks to me today, just when I need to hear from him… his voice is so gentle and warmly human and subtly invigorating, it is scarcely recognizable as advice. There are not many who are able to access my consciousness so directly these many years after their passing. My father is one. There is a dairy farmer who was my

@BowdoinCollege

neighbor many years ago. Most certainly, there is [emeritus professor] Bill Geoghegan, and… [emeritus professor] Bill Whiteside steps in from time to time. Bowdoin seems particularly skilled at hiring professors who serve also as mentors. Mentors who just never seem to quit.

Geoff Herman ’86In our last issue we mistakenly listed Sarah Orne Jewett’s honorary degree as 1900 instead of 1901.

MAGAZINE STAFF

Editor

Matt O’Donnell P’24

Consulting Editor

Scott Schaiberger ’95

Executive Editor

Alison Bennie Associate Editor

Leanne Dech

Designer and Art Director

Melissa Wells

Design Consultant

2COMMUNIQUÉ

Contributors

Jim Caton

Doug Cook

Cheryl Della Pietra

Rebecca Goldfine

Scott Hood

Micki Manheimer

Tom Porter

On the Cover: Photographs by Aaron Tilley. Set design by Sandy Suffield.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE (ISSN: 0895-2604) is published three times a year by Bowdoin College, 4104 College Station, Brunswick, Maine, 04011. Printed by Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine. Sent free of charge to all Bowdoin alumni, parents of current and recent undergraduates, members of the senior class, faculty and staff, and members of the Association of Bowdoin Friends.

Opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors.

@bowdoincollege

Please send address changes, ideas, or letters to the editor to the address above or by email to bowdoineditor@bowdoin.edu. Send class news to classnews@bowdoin.edu or to the address above.

When I was young, I spent a lot of time in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), where there was a strong indigenous community. I would go to the Intertribal Intergenerational Women’s and Girl’s Camp every summer and learn traditions like basket weaving and moccasin making, as well as values like respect for elders, the collective, and the earth. Once I left the PNW, I no longer saw people like me anywhere. Even in my US history classes in high school, we would skip the Native American history chapter because it wasn’t on the test. I realized some people didn’t even know Native Americans are still here.

Representing myself as a Native woman, and Studio Qila as an indigenous-owned business, is incredibly important to me. There is such a lack of diversity in the wellness space, an industry where there is already so much cultural appropriation.

Studio Qila is about connecting mind to muscle, developing body awareness, and truly staying present. My goal is to help students develop confidence in their abilities and in their bodies, and to show each of them how strong they are.

I started my career in consulting. I worked my way up to become a chief of staff at Uber, while also becoming a master Pilates instructor. I was halfway through an MBA when the pandemic hit, and I began teaching Pilates online to friends. When 500-plus people started attending, I founded what became Studio Qila. I built the company through my second year at Wharton and continue to grow it (with the help of creative director Louisa Cannell ’13) while also working full time now as a product strategist at Google.

For more of our interview with Bridget, visit bowdoin.edu/magazine.

The College’s small, tight-knit community is one of the reasons Bridget says she was so happy at Bowdoin, where her sister, Fiona O’Carroll, is now a senior. And community impact is a central tenet of Bridget’s mission with Studio Qila, especially “supporting underresourced communities, and amplifying Native and Black voices,” she says. “We believe wellness should be accessible to everyone.”

FROM BOWDOIN AND BEYOND PHOTO: JESSICA EBELHAR BRIDGET O’CARROLL ’13A program focused on career exploration and development grows bigger and more ambitious.

SOPHOMORE BOOTCAMP, an intensive winter break program run by Bowdoin’s Career Exploration and Development (CXD) office, touches on almost every aspect of finding a job, launching a career, and forging a meaningful life—from résumé writing and networking to soul-searching for ideas about what work will bring joy and satisfaction.

The program, piloted in 2019 with just twenty sophomores, grew to 200 students in its second year, and to 320 last year. This January, the program was expanded to accommodate every member of the sophomore class and became a mandatory element of the curriculum, in part to give classmates a shared experience.

“We knew we had something valuable on our hands and didn’t want any sophomores to miss a critical experience because they just hadn’t heard about it or thought to sign up,” CXD executive director Kristin Brennan said. “We started planning a year ago for a universal

sophomore experience,” one made possible by seed funds from an anonymous alumni gift of more than $150,000.

Eighty instructors—faculty, staff, alumni, and upperclass students—provided more than forty hours of career education over the twoweek program. Alumni and other volunteers fielded nearly a thousand networking calls from sophomores.

Kevin Robinson ’05, who started a successful property-management company, spoke on topics related to financial literacy, including investing, borrowing, and building a monetary safety net. A panel of alumni engaged in a candid conversation about juggling family expectations, financial demands, and idealism, and how their ideas about career priorities have evolved. New York Times Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter and Bowdoin trustee Katie Benner ’99 moderated the panel, which included National Board Certified County Teacher of the Year Bree Candland ’01, IT executive and Bowdoin trustee Joe Adu ’07, and Alumni Council members Mai Libman ’00, a technology entrepreneur, and Chris Omachi ’12, an executive with Audible.

Alumni Life

“The creation of the Bowdoin College Black Alumni Association (BCBAA) is a historic achievement for the College, as it is the first of its kind to support a specific racial identity group within the alumni community,” said Bowdoin’s inaugural director of multicultural alumni engagement, Joycelyn Blizzard. “As the College progresses, we look forward to learning how we can support other alumni communities of color,” she added.

The group’s constitution explains that it “was founded in recognition of the impact that Bowdoin College [has] had upon our personal lives and that of our children, nation and world.” In its mission the BCBAA “will strive to correct the historic wrongs against and obviate the inequities experienced by the Black community of Bowdoin College.” More widely, the BCBAA aims to promote the greater common good of the African diaspora through social justice, cultural preservation, economic empowerment, and other initiatives.

A coordinating council guides the BCBAA, led by president Michael Owens ’73, P’15, trustee emeritus; vice president Sherrone Torres ’12; and secretary Praise Hall ’20. As an early order of business, the council has begun to set up committees to carry out work in community service, mentorship, and financial aid.

Poke (pronounced “POH-kay”) is a staple Hawaiian dish that originated when fishermen would season cut-offs from their catch to snack on—“poke” is a Hawaiian word that means “to slice or cut crosswise into pieces.” Traditionally eaten as a snack or served as an appetizer, poke is on the menu at everything from simple events like family gatherings and luaus to special occasions such as weddings, and it has grown in popularity outside of Hawaii in recent years as a main dish in the rest of the United States.

“I love poke because it is intensely flavorful and satisfying, but also relatively light,” says chef Ian Hockenberger ’89. “You can tailor it to your tastes, spicy and bold or milder. It is a good dish in both hot and cold weather and especially fun at parties.” For a vegetarian option, tofu is a fine substitute for tuna, but “nice tomatoes when they’re in season” are even better, Ian explains. “The consistency and color are more like tuna. A purple Cherokee, Abe Lincoln, or even a yellow heirloom have good firmness and flavor.”

Serves six to eight

12 oz. ahi tuna (AAA yellowfin saku)— frozen is what you will be using unless you live in Hawaii.

½ cup diced mango, ¼- to ½-inch dice

½ cup shelled edamame

¼ cup green onion, minced

1 tablespoon Kewpie or other mayonnaise

2 tablespoons soy sauce or tamari (for a gluten-free version)

1 teaspoon sesame oil

1 teaspoon lemon juice

1 teaspoon seasoned rice vinegar

1 tablespoon sriracha or chili paste (Momofuku crispy chili paste is great)

½ sheet nori, shredded

Dice the ahi in pieces no larger than ½ inch. Place in a large mixing bowl. (If using frozen tuna, dice the tuna when it is still partially frozen, then let it thaw on a paper towel.)

Add the mango, edamame, and green onion.

In a separate, smaller bowl, whisk together the mayonnaise, soy sauce, sesame oil, lemon juice, vinegar, and chili paste.

Add the liquid mixture to the larger bowl and fold gently to coat the other ingredients.

Fold in the nori last.

Let the poke chill for an hour or so before serving.

It can be served over sushi rice, with crackers, or with fried wontons.

Ian Hockenberger ’89 graduated from Bowdoin with a degree in American history, then worked in the financial sector until 1994, when he moved to San Francisco to attend culinary school. He met his wife in Kansas City in 2003 and together they opened the Mango Room. Since 2019 he has been culinary director for Sushi Kabar, which has more than 190 locations in grocery stores, hospitals, and universities across the country.

Did You Know?

A staff member scans every detail of the lions to make a virtual 3D version, inspiring us to take a close look at the beloved guardians of the Quad.

Illustration by Nicole MedinaLions can be found guarding public buildings, flanking bridges and gates, and standing in for royalty, power, and might throughout the world. At Bowdoin, the lions on the loggia, or terrace, of the Walker Art Building fill more of a kindly role. They quietly watch students gather on the steps to study or eat or talk with friends; they forebear generations of students and children climbing on their backs for fun and photographs; they celebrate every graduate at Commencement. Earlier this semester, David Israel P’25, who is trained as an art historian and artist, and who works in Bowdoin’s academic technology and consulting group, embarked on a project to scan the lions using a portable scanner to capture thousands of images and textures. As Israel describes it: “There is some serious ‘magic’ in the software that interprets it all and lets us build up the final models.”

There are copies of the Medici lions throughout the world. In the US, the most famous are the New York Public Library’s Patience and Fortitude. When they were unveiled in 1911, some thought they should have been beavers or bison. Bowdoin’s lions are copies of marble sculptures known as the Medici lions— one of which is secondcentury Roman and the other a sixteenth-century pendant to the first, carved by Flaminio Vacca and commissioned by Ferdinando de’Medici. Travelers to Florence, Italy, can visit the Medici lions at the Loggia dei Lanzi in the Piazza della Signoria, where they have been since 1789.Bowdoin’s lions are carved not from marble but from travertine, a light-colored calcareous rock that is a type of limestone deposited around mineral springs.

Bowdoin’s lions were removed and housed in a safe place during the 2005–2007 renovation of the Walker Art Building.

David Israel P’25 has been using an Artec LEO scanner to create a 3D scan of the lions. Using the device, which Israel says “looks a little like the Pixar character WALL-E,” it took an hour or two to scan the lions and “a good day” to get the model rendered.

In designing the façade of the Walker Art Building, architect Charles McKim likely suggested the lions for the loggia, but the lions’ actual sculptor is unknown.

Both of Bowdoin’s lions place a paw on a sphere, but the lions are not identical, and their faces are quite different.

During COVID, Israel and others scanned more than 100 objects in the BCMA collections and made them available for professors to share with students who were studying remotely.

THE ASSOCIATION OF BOWDOIN FRIENDS, a group founded in 1984, has more than a thousand members. As campus readied for a return to “normal” at the start of the fall 2021 semester, the Friends received an email from the College seeking volunteers. Campus would be bustling with the return of students who took the previous year off and a large first-year class, with few studying away and a busy COVID-19 testing center in Farley Field House. Friends with a range of experience responded, including several retired physicians, technology professionals, an event planner, and a priest.

Several of the volunteers returned for the spring semester to continue in the testing center. “Janice Collins ’78 works regular eight-hour shifts,” said Sara Smith, a Bowdoin communications staff member who administers the Friends program. Arthur Pierce, a retiree in his eighties, also works regular shifts and handles check-in at the center, and controls foot traffic. “Friends like Janice and Arthur have really made a difference,” Smith continued. “It’s their commitment and enthusiasm that make the Bowdoin community so special.”

Dejie Zhen ’23 initially wondered if he should try to spend as much time as possible soaking up campus life over his four years of college, but the prospect of traveling was too tempting. He studied in South Korea in the fall before moving on to Denmark for the spring 2022 semester.

“I realized that this opportunity for a low-income student was a once-in-a-lifetime experience that I could not pass up,” Zhen said, explaining that he chose two “completely different cultures and continents” to explore.

This spring, 125 Bowdoin students are taking part in the College’s study away program, up from thirty-three in the fall. Many more are looking forward to a time when going abroad—or even across the country—is simpler: 384 students have expressed interest in the off-campus study program for the 2022–2023 academic year.

Zhen chose programs that would likely not terminate if the pandemic worsened. Hayden Weatherall ’22 did the same. “I figured that, as long as I could manage to get on the plane, I would be able to stay in France for the semester,” he said. “COVID is a fact of life here [in France], as it is everywhere. For me it’s a balance between living the semester to the fullest and making sure I’m covering all the bases for both my personal and host family’s health. From there it’s up to the COVID gods.”

When an appeal went out for volunteers to help the College cope with the demands of the pandemic, the Bowdoin “Friends” stepped up.

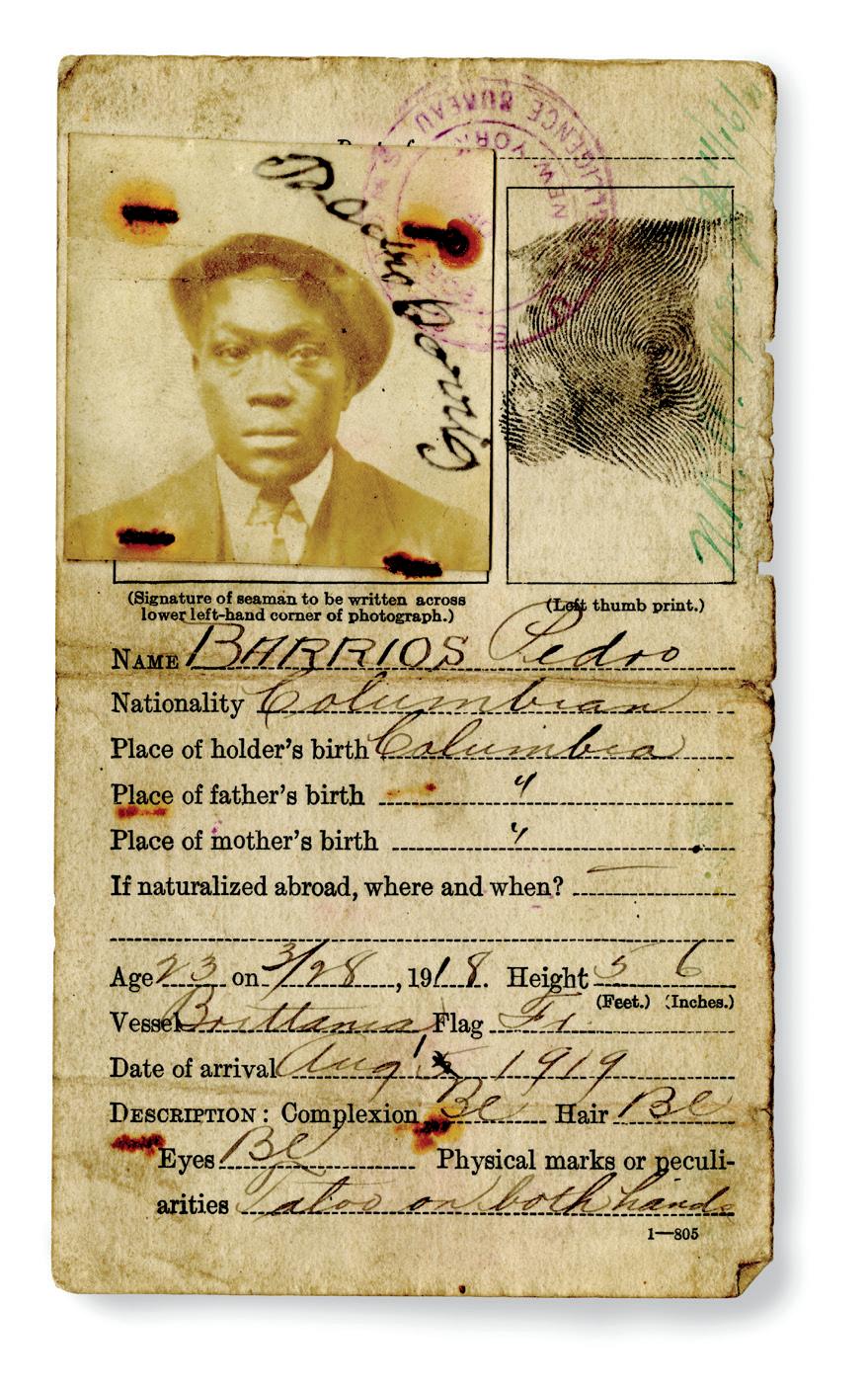

Students in Tess Chakkalakal’s Africana studies class and Maine Maritime Museum work together to tell the full story of a long-lost bill of lading.

“HISTORY IS NOT ABOUT having all the answers but telling a more complete story of the past,” said Kelly Stevenson ’24 at the opening of the student-curated show Cotton Town at the Maine Maritime Museum (MMM) in Bath, Maine.

Cotton Town was sparked by the discovery last year of 171-year-old shipping documents— and an untold story they revealed. The papers were likely tied into bundles long ago and lost from view, until Kelly Page, MMM’s collections manager, took a closer look when outside researchers asked for information on a nineteenth-century Bath ship, the John C. Calhoun. During her research, Page found that captain John Lowell of Bath had taken a secret journey in 1850.

In a letter dated October 11, 1850, Lowell asked permission from the owners of the Calhoun to transport ninety-three slaves, ages eleven to thirty-five, from Baltimore to New Orleans. “The captain was desperately trying to make the voyage profitable,” Page explained. He was to be paid twelve dollars per person over eleven years old; half that for those younger. Lowell later wrote to the ship owners about the voyage, asking for discretion:

When MMM educational staffers Sarah Timm and Luke Milardo-Gates ’14 saw Lowell’s papers, they reached out to Bowdoin Associate Professor of Africana Studies and English Tess Chakkalakal for advice. Chakkalakal suggested that her fall-semester Africana studies students collaborate with the museum to conduct further research and to curate an exhibition.

As students dove deeper into the murky water of Maine’s relationship to slavery, they curated the antique photos, letters, and artifacts through which Cotton Town explores

connections between historical industries in the state, like shipping and manufacturing, and the slave trade. “Although Maine entered the Union as a ‘free state’ in 1820, slave labor remained a pillar of Maine’s economic success until Emancipation, forty-one years later,” they note in the exhibit, which opened in December and is on view through May 8, 2022.

Professor of Religion Emerita Jorunn

Buckley is one of a tiny number of scholars who study one of the world’s smallest religious communities, the Mandaeans. As Buckley put it in a 2016 essay, “I can’t think of any colleagues in Mandaean studies who are in my own generation.” She is arguably the world’s foremost expert on the little-known religious sect, which originated around two thousand years ago in the Jordan Valley and whose members moved eastward due to persecution.

Her reputation as an expert is such that the Library of Congress recently agreed to acquire her entire academic archive, preserving it as a publicly available resource. “It’s an enormous honor to have my life’s work recognized in this way,” says Buckley.

Buckley moved to the US from her native Norway in the early 1970s to pursue a PhD at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School. Her academic achievements include six books (another is in progress), around forty articles, and a similar number of book reviews. Her focus has largely been on Mandaean mythologies and rituals, as well as the philosophical underpinnings of the religion. Her books include: The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People, which explores the lives and religious practices of contemporary Mandaeans, both in Iran and Iraq and in diaspora communities throughout the world; and The Great Stem of Souls: Reconstructing Mandaean History, a study of Mandaean priestly lineages from the third century to the present day.

“Please say nothing about my taking negroes.”Above: Pedro Barrios Seaman ID, Chase, Leavitt Co. Records, Maine Maritime Museum Archive, MS49.386.29

“I wanted to try something new and saw myself in a mentorship role,” said Sara Morcos ’24, who worked as an adult education tutor in Maine during winter break. It was “a truly rewarding process.” The prospective neuroscience major helped a student prepare for the HiSET exam—Maine’s equivalent of a GED—by volunteering fifty hours of math tutoring and preparation work.

The McKeen Center for the Common Good launched the Winter Break Community Engagement Fund in response to the pandemic last year, when the Alternative Winter Break and Alternative Spring Break programs were not possible. The new initiative continued this year to give more students meaningful experiences over break. So far, the Community Engagement Fund has provided more than eighty students with the opportunity to design their own service projects in the communities of their choice. Morcos, who has participated twice, partnered most recently with Freeport Adult Education, a connection made through their director of community programs, Peter Wagner, former associate director of alumni relations at Bowdoin.

Bowdoin’s Sexuality, Women, and Gender Center (SWAG) hosted a skating event in Watson Arena on February 6 that drew more than fifty people for ice skating and community building. “Many students had never had the chance to skate before,” said Kate Stern, associate dean of students for inclusion and diversity and director of SWAG. “It was so great to be able to be together and have fun at the start of this new semester.”

DExC will create digital equity for every Bowdoin student regardless of family means and will fully equip them with the tools and opportunities to learn and lead in a digital world.

ON FEBRUARY 22, 2022, Bowdoin announced a groundbreaking Digital Excellence Commitment (DExC) that will provide every current student and all future students with a suite of the latest Apple technology and access to a full range of course-specific software designed to advance learning, inspire innovative teaching, and create digital equity across the student body in the use of tools essential for success in the twenty-first century. DExC will build on the success of Bowdoin’s iPad Initiative by equipping all students with a 13-inch MacBook Pro powered by M1, an iPad mini, and an Apple Pencil, along with access to software used across the range of courses at the College, beginning in fall 2022.

“During the pandemic we witnessed firsthand the power of a common technology platform for teaching and learning, along with the substantial and differential benefits that come with the combination of a MacBook Pro and an iPad with an Apple Pencil,” said President Clayton Rose. “DExC allows us to level the playing field so that every student has the opportunity to fully benefit from technology that plays an essential and growing role in learning.”

Entering first-year students will receive all new equipment and software; returning students will use the iPad Pro and Apple Pencil they have already received, supplemented by a new 13-inch MacBook Pro powered by M1, with a full software suite.

Among the newest offerings from MasterClass—the streaming platform said by CBS News to be “in a class of its own,” where anyone can learn from the world’s best across a wide range of subjects—is a class on the runner’s mindset by Joan Benoit Samuelson ’79, P’12. Other newcomers joining Samuelson as expert instructors for MasterClass—which The New York Times has described as sitting “neatly at the intersection of pedagogy and entertainment”—include activist Malala Yousafzai, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, chef Roy Choi, Bill Nye (the Science Guy), and musicians Ringo Starr and Nas. With decades of experience in long-distance running and an Olympic gold medal among her many honors, Samuelson shares tips on technique, preparation, goal setting, and navigating injuries along with a philosophy and approach to running that, the company says, “allows her to discover new things about herself and rediscover the joys of running every time she laces her shoes.”

Shot and produced in MasterClass’s signature cinematic style at Bowdoin’s Farley Field House—and at a spot dear to many a Bowdoin runner, Wolfe’s Neck Farm—among other locales, the class is available to subscribers now.

Residential Life proctors and advisors (RAs) have seen how first-years and sophomores living on campus have been impacted—both positively and negatively—by the pandemic.

“Building community has been harder because people are less inclined to get together due to COVID restrictions or worries about getting COVID,” said Thomas Trundy ’23, an RA in Maine Hall. Yet, at the same time, he observed that “the first-years got really close” in the fall of 2021, sharing all meals and activities for the first few weeks under extraordinary circumstances.

With campus life opening up in the spring semester, students have become busier, spending less time in their residence halls, which, while confining, also forged tight connections with floormates.

As a proctor for Helmreich House, Michy Martinez ’23 says she felt her main job in the fall was to coax people out of their rooms. She organized house dinners and frequently invited housemates to study with her in the living room. “It’s been interesting to see how the sophomores have opened up and adjusted” after a more restricted first year, she said.

Harley Scott ’23, an RA for first-years in Osher Hall, has also appreciated the enthusiasm of students—despite the circumstances. “It is an exciting time to be an RA because all these students are coming out of two years of quarantining and into college during the craziest transition of all time,” he said. “It is awesome to see all the excitement they have for college.”

“This is a tough, weird time to be a student. But Bowdoin is SO much bigger than four years of classes. You’re a Polar Bear for life. Enjoy every second!”—A MESSAGE FROM ASHER STAMELL ’13 TO CURRENT STUDENTS, ONE OF 1,268 DELIVERED ALONG WITH A GIFT MADE ON BOWDOINONE DAY ON FEBRUARY 17, 2022.

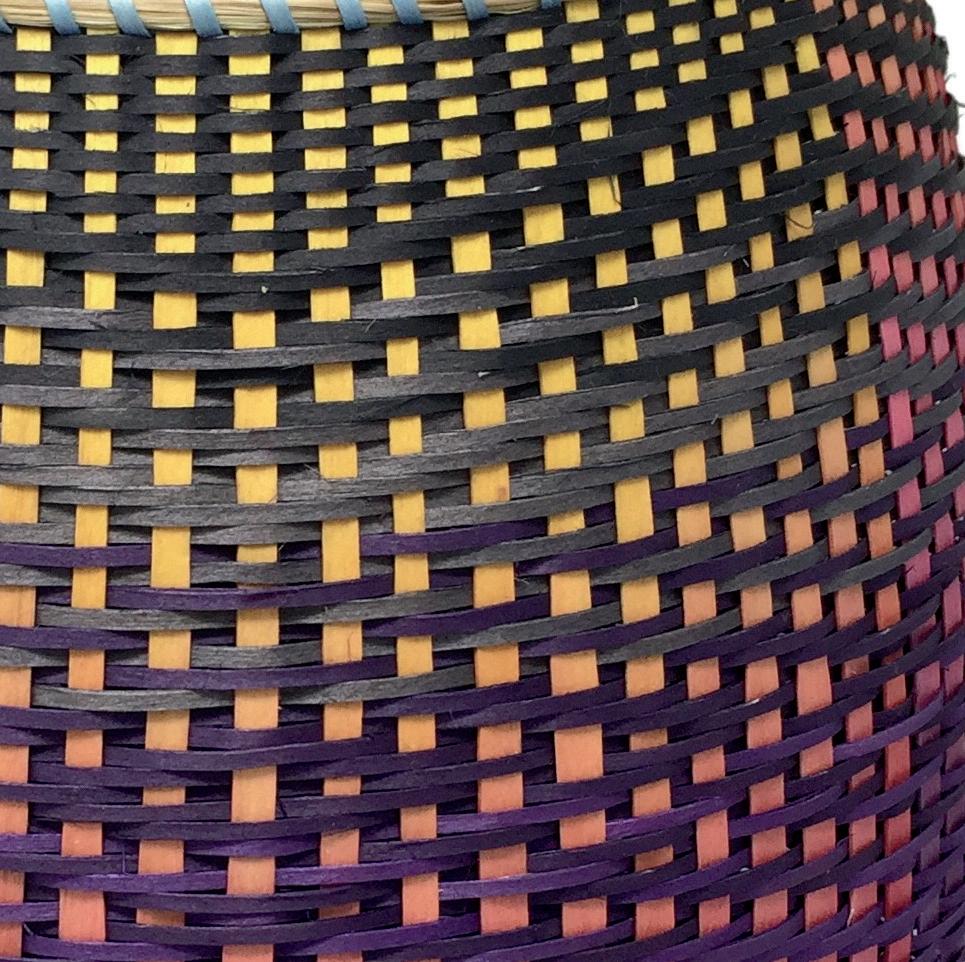

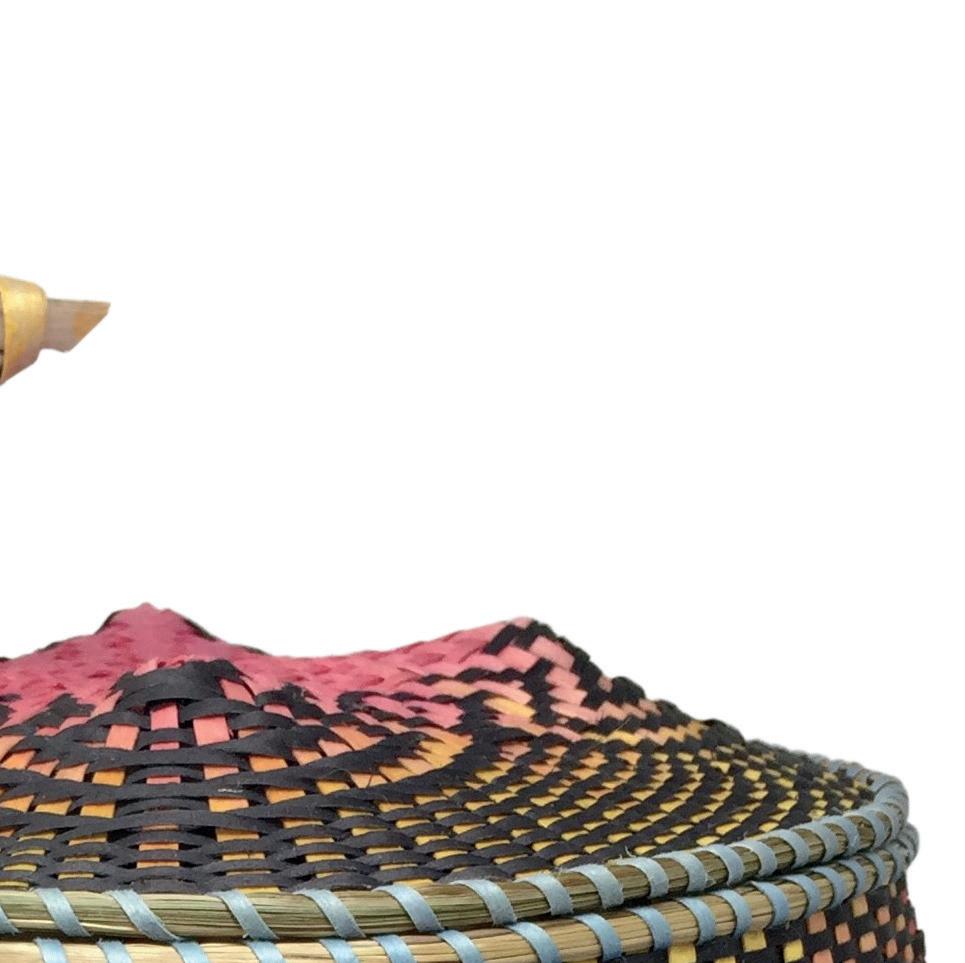

An exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art highlights the dynamic tradition of Wabanaki basketmaking.

INNOVATION AND RESILIENCE Across Three Generations of Wabanaki Basket-Making features Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Micmac artists bringing historical baskets together with some of the finest examples of contemporary Wabanaki artistry. The Wabanaki have woven baskets for all of their history, but it was when they were forced off their land by European colonization that basketmaking became a means of economic independence and resistance to assimilation. Since the nineteenth century, Wabanaki artists have innovated traditional utilitarian forms to meet collectors’ tastes, leading to a new style of basketmaking— “fancy baskets,” like the one pictured here by artist Geo Neptune, Apikcilu Binds the Sun

Neptune is a master basketweaver, educator, and activist who is the grandchild of legendary basketweaver Molly Neptune Parker H’15. In a virtual conversation with the Bowdoin community, Neptune, who is nonbinary, explained that they are what is known as “two-spirit” by the Wabanaki people and talked about growing up without elders. (“I had to be my own elder,” they said.) Neptune started weaving baskets with their grandmother at the age of four. After graduating from Dartmouth College in 2010, Neptune has worked to foster cultural preservation within Wabanaki communities and advocated for contemporary issues faced by Indigenous people. Though known mainly for their ash and sweetgrass basketry, Neptune is also a drag queen and model for print and runway, and is featured in the “Can We Say Bye-Bye to the Binary?” episode of the Netflix series Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness

Curated by Amanda Cassano ’22, Sunshine Eaton ’22, and Shandiin Largo ’23—all members of the Native American Student Association—the exhibition runs through May 1, 2022. A recording of the conversation with Neptune can be found at bowdo.in/neptune.

The Loneliest Americans

JAY CASPIAN KANG ’02 (Crown, 2021)

This memoir from New York Times writer Jay Caspian Kang ’02 has been lauded as one of the best books of the year. A child of Korean immigrants, Kang blends family history and original reportage to explore Asian American identity in a Black and white world amid a wave of anti-Asian violence and critically examines his place within his communities and in America.

“OTHER ALUMS WERE THINKING ABOUT where they would go after college and when they would come back to Maine,” said Kristina M. J. Powell ’06. “I went to career services to figure out how I could stay.” Powell wrote her own story to live and work in Maine, and as the new executive director of the nonprofit Telling Room in Portland, she’ll help empower young people to share their experiences and express themselves through writing and storytelling.

Powell researched The Telling Room during her MBA studies at Purdue, and just a short time later landed what she calls her “dream job.” In a December 19, 2021, Portland Press Herald article, she said, “I’ve always admired their work so much and been drawn to the mission of the organization—because of the stories that are told here, because of the voices, and also because of diversity and equity and being a woman of color.”

Accusation: A Thriller

PAUL BATISTA ’71 (Oceanview Publishing, 2022)

Homesteading and Ranching in the Upper Green River Valley

ANN CHAMBERS NOBLE ’82 and Jonita Sommers (Laguna Wilderness Press, 2020)

Powell credits her major in anthropology and minor in sociology for helping her to hone her skills in listening to people. “I have always been fascinated by understanding people’s journeys of identity formation and how that changes as well, and how painful and also joyful it can be.... Creating space for that is part of what we do here at The Telling Room, as students put pen to paper to find their voice.”

Dear Maine: The Trials and Triumphs of Maine’s 21st Century Immigrants

MORGAN RIELLY ’18 and Reza Jalali (Islandport Press, 2021)

Beyond the Tides: Classic Tales of Richard M. Hallet

FREDERIC B. HILL ’62 (Down East Books, 2022)

Through intent listening and a deep respect for identity, Kristina M. J. Powell ’06 reveals new possibilities for Maine’s children.Kristina M. J. Powell ’06 is executive director of The Telling Room, an organization dedicated to helping kids aged six to eighteen build confidence and ensure success. PHOTO: RYLAN HYNES

Hawthorne-Longfellow Library launched “Bowdoin Reads, Watches, Listens” in 2008 to bring the campus community together around books, video, and audio sparking inspiration. H-L has recapped the most-viewed recommendations of the past year and invites you to engage in the campus conversation by sharing your favorite in the comments section of “2021 in Review” at bowdo.in/reads, or submit a photo and recommendation to Marieke Van Der Steenhoven at mvanders@bowdoin.edu.

Alumni Life

Two skiers who raced against each other in college now race at the Paralympics as one.

The Office of Alumni Relations worked with Portland, Maine, artist Abe Tensia ’14 to illustrate three Bowdoin-themed Valentines that were shared with alumni online and via social media. The assignment fit cozily with Tensia’s style of pen and ink drawings that celebrate creative play and the natural wonder and whimsy of the great outdoors, both things, she said, “near and dear” to her heart. Tensia grew up in Wyoming but said that she didn’t really appreciate the outdoors and nature until her time at Bowdoin.

For more of Abe’s work, visit abetensia.com.

ONE WAY OR ANOTHER, Jake Adicoff ’18, a medal favorite in several events, will have skied his way into history at the 2022 Beijing Paralympics—no other Bowdoin athlete has competed in three Olympic or Paralympic Games. Adicoff raced in the Sochi Paralympics in 2014 and won silver in the 10k classic at the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea. Adicoff retired from professional racing in 2018 but was called back to the sport during the pandemic and set a goal to reach the Games again. His guide is fellow NESCAC Nordic racer Sam Wood, a 2019 Middlebury graduate and Adicoff’s friend and teammate on the Sun Valley Ski Educational Foundation XC Gold Team. With Wood leading the way, Adicoff won a gold medal in the 10k classic, took silver in the 1.5k classic sprint, and wrapped the trifecta with bronze in the 15k skate at the 2022 World Championship in January, just before Beijing.

For a full list of Bowdoin Olympic and Paralympic athletes, visit athletics.bowdoin.edu.

Investing in Our Community

StrongArm fuses technology with the common good.

STRONGARM CALLS THE WORKERS who wear their products “industrial athletes.” “They put their bodies on the line every day,” explains Alex Weaver ’07, marketing director for StrongArm Technologies. “People have a right to return home from work in the condition they arrive,” says Cofounder and Chief Operating Officer Matt Norcia ’03. “I get excited every day about what we’re doing—we have an opportunity to help people.” Jackie LoVerme ’03, executive director of sales, completes the Bowdoin triumvirate in StrongArm’s front office.

The three alumni have helped StrongArm quickly become a leader in workplace safety technology. After Sean Petterson’s father died onsite during one of his construction company’s projects, Petterson dedicated himself to a single-minded mission—to prevent an accident like that from happening to anybody else—and he founded StrongArm in 2013. The company was originally founded with a product called ErgoSkeleton, a high-tech back brace. But the game changer for StrongArm and its industrial athletes is the SafeWork System, a real-time wearable safety sensor that utilizes haptic technology—providing alerts by experiential feedback, in this case, vibrations. SafeWork led to a 60 percent injury reduction over three years of use by Walmart associates, and a year-over-year average of 52 percent injury reduction for all of StrongArm’s customers and the 35,000 workers who currently use the system every day. Companies that use StrongArm’s safety systems have seen a 250 percent return on investment based on worker injury reduction and prevention, leading to a 150 percent yearly growth for StrongArm and a recent Series B funding release.

Considering that, according to Norcia, an average of 38,812 occupational injuries occur worldwide every hour, StrongArm and its Bowdoin leaders are making a big impact. “These industrial athletes are real people with families and livelihoods to protect,” Norcia says. “The vast majority of their injuries could have been prevented. This is why StrongArm exists.”

The scope and influence of Latin American literature is often neglected by the English-speaking academic world, says Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Gustavo Faverón Patriau, who is himself an acclaimed Peruvian writer.

To help address this imbalance, Faverón Patriau is teaching a new course this semester looking at the work of one of the region’s most influential writers. Borges and the Borgesian focuses on the pivotal role played by the twentieth-century Argentinian author and poet Jorge Luis Borges in reimagining Latin American literature from a postcolonial perspective.

“Borges understood that literature written in the so-called Third World had the power to transform Western literary traditions forever,” explains Faverón Patriau. “The way in which his work marked the beginning of poststructuralism and postmodernism in European philosophy is studied in the class as a radical example of decolonial thought.”

For students in the class, the timing couldn’t be better. Faverón Patriau is steeped in Borges’s work, having recently published El orden del Aleph, a collection of essays that explores Borges’s short story “El Aleph,” which Faverón Patriau describes as one of the most influential short stories in contemporary world literature.

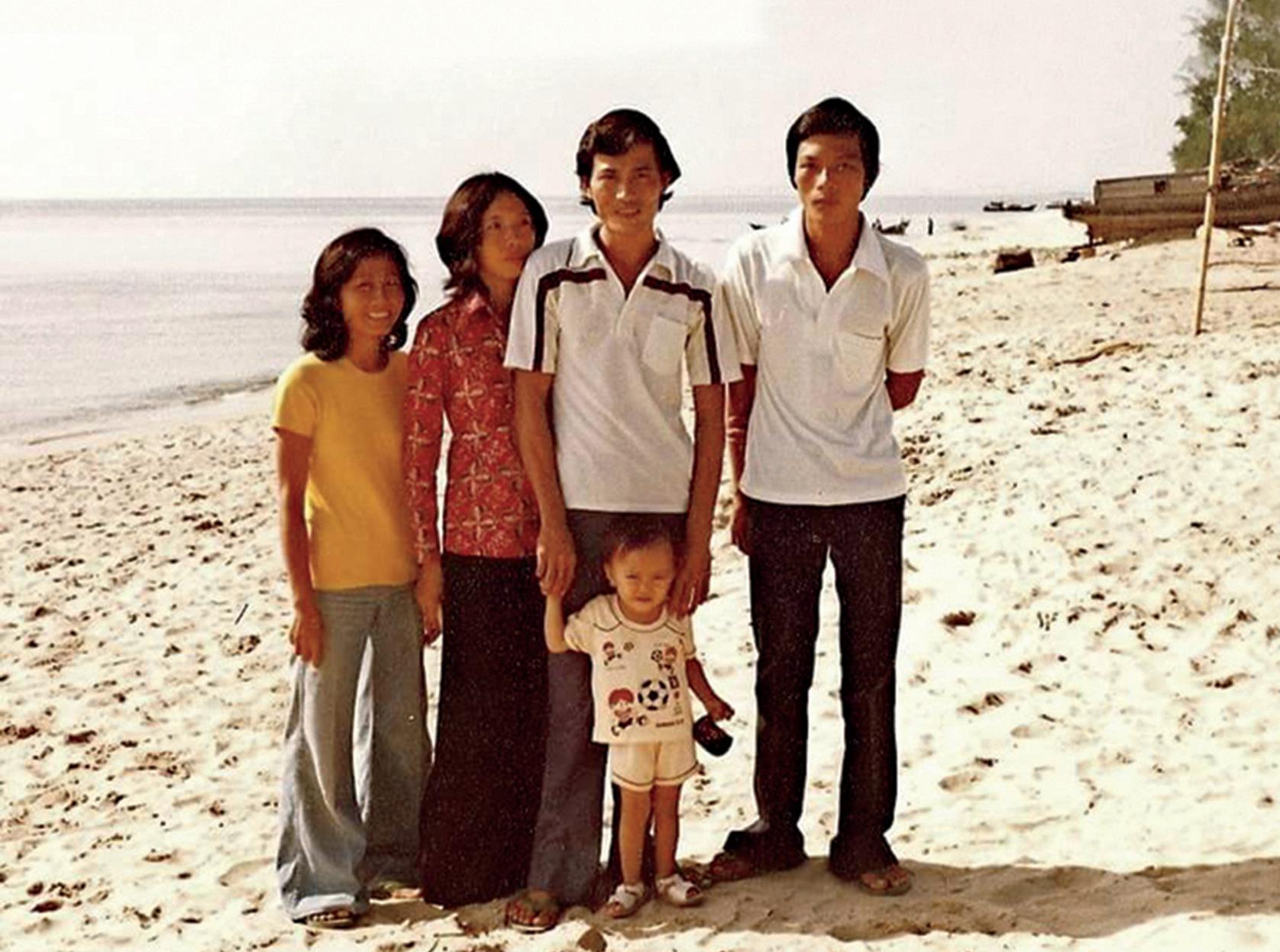

Mai Libman ’00 had a rocky relationship with Bowdoin, and it wasn’t until many years after graduation that she reconnected and found her community here.

MAY 27, 2000 , felt like the happiest day of my life. When I was handed my diploma, it was like I was escaping from four years at Bowdoin—four years of difficult suffering and painful isolation. As a woman of color from a refugee family, it seemed to me that no one even noticed how traumatic it was to suddenly be dropped into Bowdoin from a radically different culture and socioeconomic class. In so many ways, my college experience was demoralizing, humiliating, confusing, and depressing. When I got my diploma and left Maine, swearing never to come back, I felt like a refugee again, escaping from a place where I didn’t belong and wasn’t accepted.

My Bowdoin years were difficult, there’s no denying it. But I’m pleased to say that, in retrospect, my inner suffering in college has, step by step, led to quite a wonderful unfolding. The education I gained at Bowdoin prepared me well for grad school and a diverse public service and business career. But for nearly twenty years after getting my diploma and separating from Bowdoin, I couldn’t look back at those lonely, confused years without tears. The pain of feeling left out, stuck on the periphery of campus life—this phase of my life was the hardest experience I ever encountered, even harder than living in abject poverty as a child refugee trying to assimilate into a foreign land. When I was a child, my mom held me, begging for a bowl of rice on the streets of Bangkok, or waited in line on Seattle’s Rainier Avenue for a block of cheese. I went through high school wearing no more than two pairs of jeans that I rotated with different tops. At least back in my “’hood,” I’d had my family and friends in a rough-but-cohesive subculture where I felt I fit in. Bowdoin simply had no place for me.

But I now know that, ever since I left campus, Bowdoin has been doing its very best to evolve into a more inclusive community. I now even see myself as the ungrateful one in the relationship.

I was given everything Bowdoin had to offer back then. I received the opportunity to break free from my unlucky social order, having been born into a war-torn country. And I was given the chance to mingle with a network of the world’s brightest. I had the opening to build everlasting relationships—and of course there was the golden intellectual opportunity to grasp new knowledge of facts, life, and self. Looking back, I can see that Bowdoin made every effort, with the right intentions, to help me learn and grow in ways that have forever altered my personal and professional path.

But back then, nothing quite made sense or seemed to have any value to me. Even seventeen years later, as I stood on a mountain in Asia with two lifelong Bowdoin friends—one of whom is my husband, Arkady Libman ’00, and the other like a brother, Naeem Ahmed ’00— I didn’t have the courage to accept and be thankful for everything positive that Bowdoin gave me. My painful memories still clouded my heart with darkness. So many nonspecific unravelings of events culminated in a mountain of hate—being told on my first day by a classmate that I got into Bowdoin because of affirmative action; struggling to fit in among whispers from fellow students; or my all-nighters to be able to achieve what most could do in a few hours. From the beginning, I approached Bowdoin with the idea that I didn’t want to be there. Coming from the not-so-glamorous neighborhoods outside of Boston, I wanted to be in a vibrant city atmosphere, not out in the proverbial sticks. I made the decision to attend Bowdoin because the College accepted me and gave me a generous financial aid package. But even back then Bowdoin was taking steps to move toward creating diversity, bringing in someone like me—a first-gen refugee, a woman of color coming from a socioeconomically depressed community.

I didn’t have attributes that would signal the perfect Bowdoin student. My schooling had not been up to par; I had the bare minimum SAT score—I definitely didn’t look like someone who would give back in the future. Bowdoin was giving me the chance of a lifetime to break through barriers and rise up. I now know that it’s really very difficult for someone like me to be assimilated into a small homogenous college like Bowdoin. I came to the school with an ingrained negative attitude of being an unwanted outsider. And I projected that attitude onto everything that happened to me for the next four years. Even though I learned to do well in my studies, I didn’t learn how to transcend my defensive attitudes and feel like I was part of a larger community, and I mostly related to a few other immigrant and low-income students who felt like I did. After I left, I really didn’t want to have anything to do with the College.

Until Molly Carr reached out from Bowdoin’s annual giving office, asking to meet for coffee.

I was perplexed. I was, after all, an ungrateful alum. Why did Bowdoin want to reach out to me? But one cup of coffee with Molly at Café Fixe forever transformed my attitude. I needed that hand reaching out to give me the courage for introspection, helping me see the light. What came after was unimaginable—my feeling of genuine inclusion. Soon thereafter I was invited to a gathering in Boston, where I met Sarah Cameron ’05 from the alumni relations office. Then Kristin Brennan, director of CXD, reached out about my speaking to students during Bowdoin’s Sophomore Career Bootcamp just before COVID. Through that experience I met an old friend, Adam Greene ’01, and a new friend/mentor, David Brown ’79. A definite inner healing was taking place.

I was then nominated and invited to join the Alumni Council, where I met Rodie Lloyd ’80, Matt Roberts ’93, Awa Diaw ’11, Michel Bamani ’08, Tim Brooks ’67, and many others who have welcomed me with open arms and listened to me even when my views differed from theirs. I was, after all this time, falling in love with Bowdoin. I felt included and respected as an equal despite my differing experience and perspective. I was shocked that Bowdoin even

wanted someone with my negative experience to represent alumni and to share my perspective so that we all can learn together. My voice was heard, and it wants to be heard. I am finally feeling accepted into a community that I wanted to be a part of so much. My glee to jump on calls and visit Bowdoin is the feeling I wish I had had when I was in college. I am given an opportunity, in a way, to relive college. I am making friends who will not just greet me at our Council meetings, but to whom I can always reach out to talk, grab dinner, or simply connect for the sake of friendship. My budding love for my college has shocked my close family and friends who knew about my difficult undergrad years at Bowdoin. Step by step, a new level of reflection has allowed me to see that Bowdoin was steadily trying to effect change, even when I was there— they were already looking to detect potential talent in applicants, beyond their test scores,

during a time when most other schools were overly focused on tangibles, with little regard for a candidate’s intangibles. In turn, Bowdoin was also self-reflecting to change.

My involvement with the Alumni Council has allowed me to witness firsthand Bowdoin’s mission to effect real change at all levels. Every Alumni Council committee has spent hours thinking through processes, programs, and mission statements to create a culture of belonging for all students and alumni, regardless of their race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, political views, and more. As a woman of color, I believe strongly that this is the right direction, and I am pleasantly surprised at how much progress Bowdoin has made through honestly learning from its past. At the same time, I hope the College doesn’t ignore the ongoing challenges of student groups like white men, who also have their struggles and contributions

and who have helped me advance personally and professionally.

Coming to recognize that no person or organization, including Bowdoin, is perfect has helped me realize that the most important thing is to continue trying to make change, create a positive impact, and elevate everyone together. It’s essential for the College to continually look forward, without forgetting those who have been pivotal in creating the past. We must all regularly reflect, listen, and share new visions of an ever-brighter and more-inclusive future. To paraphrase Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, only then can real dialogue and desired change take place.

Mai Libman ’00 is CEO and cofounder of Haystack Dx and author of the recent memoir Worlds Apart: My Personal Life Journey through Transcultural Poverty, Privilege, and Passion. She chairs the diversity committee of Bowdoin’s Alumni Council.

BY

Artist James Michalopoulos ’74 has been influenced by the colorful, confounding streets of New Orleans, and in turn has influenced them.

BY

Artist James Michalopoulos ’74 has been influenced by the colorful, confounding streets of New Orleans, and in turn has influenced them.

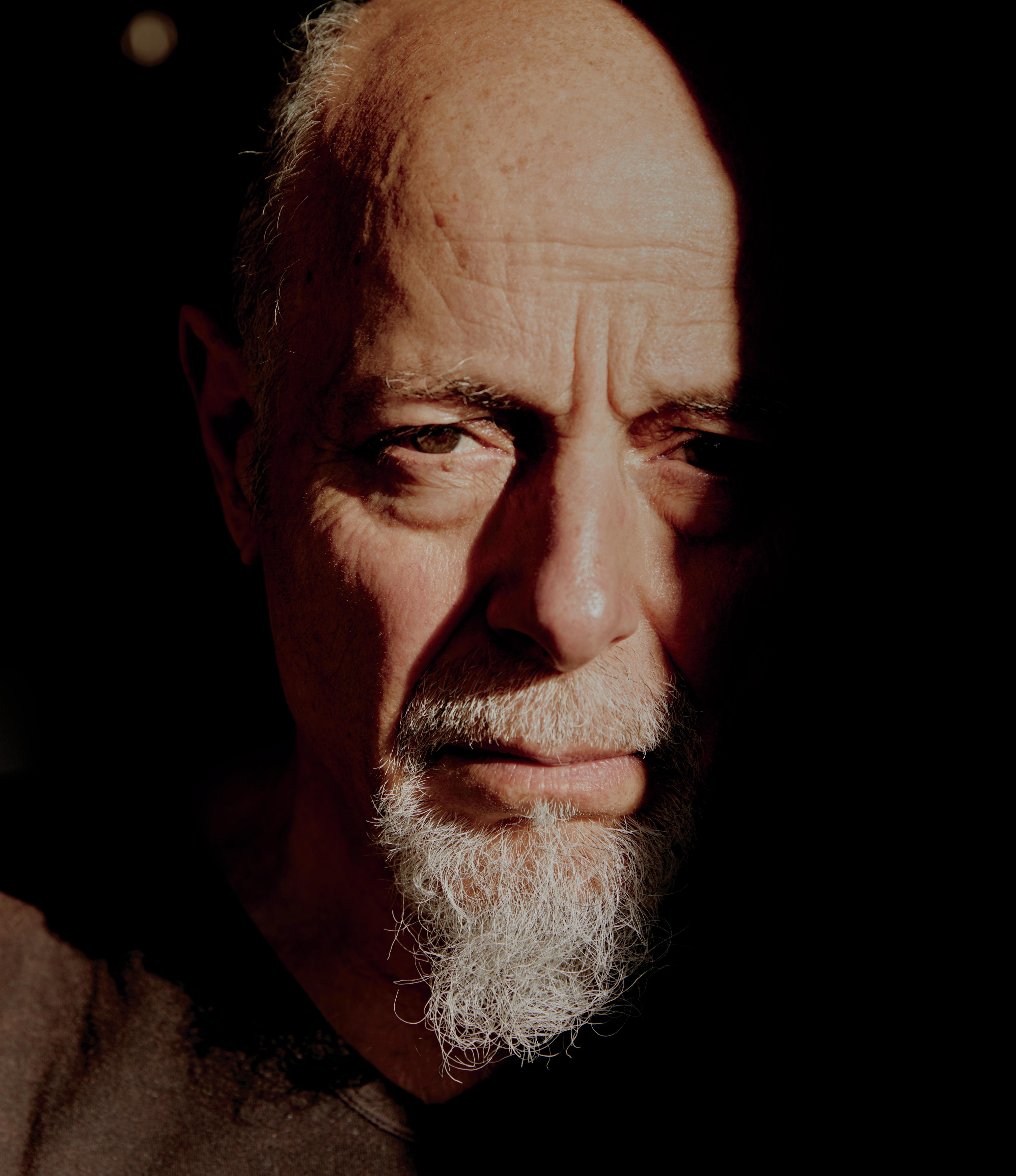

“FOR ME, this was all about that guy in the background,” says James Michalopoulos ’74. He’s paused in front of one of his own paintings, hung amid a sprawling and colorful retrospective of his work. The show occupies a large gallery on the second floor of the New Orleans Jazz Museum, which is set in an imposing former US Mint building constructed in the nineteenth century at the edge of the city’s French Quarter.

The painting in front of him is uncharacteristically quiet and serene. All around him, his other works depict New Orleans musical royalty, a lineup of larger-than-life luminaries who all but burst of out their frames—Fats Domino, Mahalia Jackson, Louis Armstrong, Allen Toussaint. With his trademark style, which has been described as “rubbery” and “almost psychedelically distorted,” he makes the streets dance and the hidden lives of musicians pulse with energy.

But this one painting is quiet. It depicts three musicians playing their instruments: a sousaphone, a trombone, and a trumpet. They’re in what appears to be a dusky club with a wellvarnished wooden floor. They wear the traditional brass band outfits of dark pants, white shirts, black tie, and white marching band caps with peaked crowns.

The trumpet player stands far back, at the edge of shadows, looking downward. “I just made up a story about him,” Michalopoulos says. “He’s in his early forties, and he’s sort of stuck and lost in his life.”

Michalopoulos has for decades been capturing the people, streets, and scenes that animate this city on the Gulf of Mexico. In the four decades that New Orleans has been

his home, he’s emerged as the artist arguably most closely associated with it. His paintings are regularly featured at well-attended shows in city museums and galleries; he receives important commissions, both public and private; he has contributed six posters for the city’s high-profile Jazz and Heritage Festival; and he has spawned a raft of imitators who have copied his dynamic, vaguely surrealistic style. His work tends to be frenzied and expressionist, thick ridges of paint atop eskers of more paint. But his vivid tableaux are realistic in another way: they offer a clear lens into the city’s high-spirited life and high-stepping energy.

Yet spend some time with him and you’ll come to understand that it’s not just the people out front leading the nation’s longest and loudest party who capture his attention. He’s equally intrigued by those in the shadows.

“This reminds me of Edward Hopper,” Michalopoulos says, referencing an American artist who had an important influence early in his career. “In his paintings, if you scratched the surface, there’s this yawning despair.”

Michalopoulos is keenly attuned to those on the outskirts of the bright lights, those at risk of being lost amid the music and the dance, especially in a city changing as swiftly and dramatically as New Orleans. The neighborhoods have been gentrifying and are much more expensive. “The class composition has changed, and it’s not as hospitable for artists,” he says. “And I measure everything in that world by that yardstick.”

JAMES MICHALOPOULOS was born in Pittsburgh but largely raised in Connecticut, where his family moved when he was seven. His father was a noted architect and urban designer who happened to be an art collector, and Michalopoulos grew up in a household filled with the work of such artists as Braque, Picasso, and his uncle William Baziotes, the abstract expressionist.

Still, art was at the periphery rather than the center of his life. At Bowdoin, new interests steered him toward economics and politics— “You know, that was, like, a tumultuous period socially”—although art lingered at the margins. He recalled a series of paintings of farm animals on exhibition at the Museum of Art by Bowdoin professor Tom Cornell. “It was a series of

drawings of pigs, and they were exquisite,” he says. “They were elegant. They were beautiful. And I was just totally taken by it.”

The museum also offered him occasional refuge. This was the early ’70s, and of course he spent a fair amount of time on the Quad, often with Frisbee in hand. The museum was right there, and so he would slip into the quiet of its muffled galleries. “It was a place for me to repair to on occasion,” he says. “It was a good influence, and you know, so much [of life] wasn’t back then.”

He also worked off campus in Brunswick in a food co-op, and took that experience to the Boston area, where he helped launch what would become one of the largest food co-ops in the region, located midway between MIT and Harvard. “We had 4,500 members. I used to cut cheddar cheese for Noam Chomsky,” he says. “Actually, I made that up. But I might have. I hope I did.”

It was on a vacation to Niagara Falls when art caught up with him. It turned out you could only admire the falls for so long, but in wandering around, an intriguing old house caught his attention. He began to sketch it and spent about four days doing so. At one point the owner came out, inquired as to what he was doing, and offered to buy his sketch. He made “about twenty-five dollars.”

He stepped up his sketching and painting after he moved to Washington, DC. On a whim in the winter of 1978, he decided to flee the snow and cold, and he hitchhiked to New Orleans with a backpack and some painting gear. “It was south and warm and exotic—so that was it,” he says.

He arrived at night and walked from the highway where he’d been let off toward the French Quarter, enchanted by the gnarled live oaks that created a canopy over the streets and the vibrant life that spilled off porches and onto the streets. “I was fascinated by all the vitality and the unique richness of it,” he says.

He returned to Washington and, the next winter, had a dalliance with Key West. “It was nowhere near as complex or rich as New Orleans.” So the following year he returned once again to the city on the Mississippi River. This time he remained for good.

IN THE MORE THAN FOUR DECADES since he arrived in New Orleans, Michalopoulos has been both influenced by the colorful, confounding streets of the city, and in turn has influenced them.

He began by sketching what he saw on the city’s byways, capturing random scenes and selling his work for a few dollars to get by. Outside a grocery store, he sketched people waiting at a bus stop and hustled to sell them the picture before their bus arrived. He worked for a stint as a courtroom artist for the local paper. He crashed in abandoned houses and lived in a truck for a time.

He sought out a permit to sell at Jackson Square in the heart of the tourist district, but

all 200 permits had been issued and he was met with a waiting list. So he moved around, painting and selling here and there, and for a time set up in front of a Bourbon Street restaurant at the invitation of its general manager, pushing a cart with his supplies and clipping his fresh paintings onto a gate for display. He rigged up a Vespa scooter with an easel on the back, a mobile plein air studio and gallery. He painted street scenes he sold to tourists and passersby. When they asked how much the paintings cost, he asked how much money they had.

He is primarily a self-taught painter, although he leveraged his skill by taking two classes on figure drawing at the University of New Orleans

and the New Orleans Academy of Fine Art. As his skills improved and his vision sharpened, so did his situation. His work started to sell in places other than on street corners—his first show was at a pizza parlor—and a few galleries asked to feature his work. New Orleans began to take notice. Along the way, Michalopoulos started to develop a distinct style: a sense of place that captured New Orleans in a way that hadn’t been seen before. In a city that’s long been famed for its unique, idiosyncratic architecture, Michalopoulos added another layer, animating the antiquated houses and spalling buildings. In his renditions, some structures seem at first to be sinking into swampy soils—a not uncommon occurrence

around the city, where lintels and cornices often skew at odd angles. But that’s just a springboard to a more ebullient quality, with some buildings seemingly controlled like marionettes enlivened by an outside force, some coming to life on their own in a way that’s both charming and alarming. Upper floors sway one way while bottom floors move another. Perspectives change, violating every canon of classical art.

And then there’s the color—vibrant hues of rich cobalt and crimson, and night skies streaked with indigo and magenta and dotted with luminous crescent moons, all conspiring to create a sense of motion and dance, a vivification of an inanimate world.

“I think there is a quality of movement in most of it,” Michalopoulos wrote in his notes for the show at the Jazz Museum. “I love the lyric that life can be: off-kilter, chaotic, and colorful, a kaleidoscopic unfolding. I try not to interpret too much because I believe it stifles the work.”

With his growing artistic success came financial stability, and then some. He acquired several properties. He bought and lived in an old beer warehouse just off Frenchmen Street, using a dozen paintings for a down payment. Inside, he experimented with perspective and materials in full scale, and created a whimsical space of chain link and tin and improbable balconies.

He ventured into other businesses, opening a well-regarded restaurant in the nearby town of Covington (since closed). He spent time in France at the encouragement of a patron and eventually bought a home in Burgundy, where he created a studio in an old barn. He also purchased a 700-year-old defunct tile factory along a river, with the idea of making tiles there once again (pending).

While in France, he came to appreciate the nuances of local wines and wanted to bring that locally grounded approach to adult beverages to New Orleans. The Gulf South is inhospitable to grapes, but sugar cane grows in abundance. He opened a rum distillery in 1995, making it the first craft rum distillery in the nation in over a century. (There are now well over 200 American distilleries making rum.)

In the early 2000s, he acquired a cluster of old buildings on Elysian Fields, where he set

IN A CITY THAT’S LONG BEEN FAMED FOR ITS UNIQUE, IDIOSYNCRATIC ARCHITECTURE, MICHALOPOULOS ADDED ANOTHER LAYER.Michalopoulos in his studio, with a new painting, Water Ways to Go, in progress on the easel.

up his studio. The main building is sprawling and drafty, with soaring ceilings and ponderous beams and gaps that offer glimpses of the open sky above. In the middle of this interior acreage is an easel and a large, partially completed canvas, surrounded by great piles of empty boxes and spent paint tubes, as high as snow after a plow moves through a street in Maine. Some dusty caskets sit along one side, a reminder that these buildings were once a funeral home. Paintings in various stages of completion lean against the walls here and there.

Even with the demands of keeping track of his expanding businesses, Michalopoulos spends much of his day in this sanctuary, at

his easel. Sometimes he listens to music as he paints, sometimes he doesn’t. His multicolored oils are layered on thickly, chiefly with a palette knife. When he picks up a brush, it’s often to use ends opposite the brushes to make ridged stripes and striations in the oils. The paintings have a dense, tactile feel, as if capturing movement unawares.

He’s best known for his architectural paintings, but his eye wanders. He’ll paint musicians for a while, and then “go the other way,” as he puts it, and return to painting houses. “Or sunflowers,” he says. “I couldn’t get away from sunflowers for a whole summer two years ago.” For a time, he went through a cow phase.

With his paintings of musicians, he says he often does several studies—for a portrait of Louis Armstrong, for instance, he says he might do a dozen different versions of his face and expressions in order to get it right. Once he feels he’s getting close, he takes off, with his palette knife moving in rhythmic strokes to fill its broad outlines. When the painting feels right—maybe in a day, maybe in a couple of days—he signs it, marking that it’s ready for the gallery. If not, it remains against a wall, unsigned. He may come back to it the next day, or the next month. Or not at all— abandonment happens, he says. He shrugs.

Michalopoulos at the keys of Fats Domino’s piano on display at the New Orleans Jazz Museum as part of the retrospective From the Fat Man to Mahalia: James Michalopoulos’ Music Paintings

Writ Large and Blunder Busker hang on the wall behind him.

Writ Large and Blunder Busker hang on the wall behind him.

THROUGHOUT ITS THREE-CENTURY HISTORY, New Orleans has suffered tremendous peaks and valleys—frequent floods, yellow fever, fires, devastating hurricanes. That’s no less true of the past half century. New Orleans suffered vast population loss as the integration of schools and public facilities caused white families to flee to the suburbs. Widespread destruction followed Hurricane Katrina in 2005. But New Orleans soon rebounded, as empty-nesters and creativeclass types were drawn by an urbanity that lies less on a heroic scale and more on the intimacy of the streets, the wanderings of which lead to aromas from a relentless culinary scene and sounds emanating from a vibrant cultural life.

Change implies loss—as one group gains, another loses. That might be the natural evolution of cities, but lately it’s resulted in a rapid gentrification, as one group moves in another is displaced. Michalopoulos is pleased that many of the century-old homes once destined for termites and slow rot are being restored and preserved. But he acknowledges that this comes with unwelcome results—as longtime residents are pushed out of the city, the personality of the city alters. There’s a sense that the old spirit of the city is starting to erode.

“It’s a city where people were encouraged to take risks,” he says. But as rents rise and new residents complain of loud musicians parading through the streets, something becomes lost.

“The base of our culture is celebration,” he says. “Our fundamental engagement in this city is finally religious, even though it looks depraved. It’s a kind of indulgence in service of liberation.”

He notes that Mardi Gras in recent years has become less a joyous celebration of personal creativity and has edged toward a generic, could-be-anywhere party scene. “We treat very casually the wealth that we have,” he says. “And you don’t really appreciate the beauty until it’s not there and it’s all just Bud hats. And you go, ‘What happened?’ It’s a wake-up call.”

When Michalopoulos arrived in the late 1970s, New Orleans was a place where an artist with little means could find a place to land and to grow personally and artistically while just getting by. “The city was always an inexpensive place to live, and it’s turned into an expensive place to live.”

He’s quietly set about doing a small part to reverse that. Among his acquisitions was a compound of old semi-industrial buildings occupying a full city block, with parts dating back to the nineteenth century. It was once home to a beer distributor, whose horses to pull the beer wagons were stabled across the street, and then a paper and box warehouse. “This was a chute for hay,” he says, pointing out a recess in the wall as we walked through one afternoon. “Well, that’s what they say. I think it was probably a chute for paper. Either one, though, it makes sense.”

The 110,000-square-foot complex is in an unlovely but relatively central part of the city, next to a road overpass and a train yard. Michalopoulos and his crew have been gradually converting it into a warren of more than a hundred artists’ studios, which he’s leasing out at reasonable rents. Painters, sculptors, and musicians occupy studios that range from compact to spacious.

“It’s about creating a safe harbor for expression,” he says. “Mostly what we’ve done is artists’ studio space, but we’re looking at a shift into actual housing. We’ll see how we do with it.”

Across the street he’s bought up several ramshackle homes, which he’s in the process of converting into affordable living quarters loosely following a cohousing model, with spaces both private and public for residents. “For me it’s an experiment in a novel idea,” he says. “Here we can live in an environment that will protect us and let us do our thing.”

HIS NEW WORK SUGGESTS he is boldly exploring new realms—beyond cottages, sunflowers, and cows. In a large alcove of his studio, next to two very dusty caskets, were his newest canvases, still drying. They were to be patched into one long canvas when installed, extending twenty

feet and depicting vast, swirling scenes of the galaxies and cosmos. Like most everything else that he produces, this painting is the antithesis of static and still. The stars pulse, the galaxies swirl, the cosmic gases seem to quiver with expectation.

The work was commissioned by a health sciences school and was to be installed atop a wide set of stairs. It would create the impression that students are ascending toward the stars. In other hallways, some of his other paintings are hung, including some large semi-abstract canvases inspired by microbes and other microscopic miniatures. “This is a hematological thing,” he noted of one. “At a certain point they become much more like an artistic expression rather than an illustration,” he says.

The space between a pensive horn player lost in thought at a club—a study in incertitude, someone at once the center of and on the margins of that painting featured at the Jazz Museum—to his cosmic new work exemplifies how far Michalopoulos has traveled in his mind, venturing to the far edges of the universe, capturing everything in between in a gyre of unseen motion and swirling colors.

“It’s a fair amount of anarchy, and then correction,” he said once of his creative process. “There’s a tendency among a lot of people toward refinement. I’m about to funkify that.”

Wayne Curtis’s writing can be found in publications such as The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Bon Appétit, American Scholar, The Atlantic, and Yankee, among many others. He’s contributed to the radio show This American Life and is currently a contributing editor at The Daily Beast and Garden & Gun

Daymon Gardner is a photographer based in New Orleans. See more of his work at daymongardner.com.

“THERE’S A TENDENCY AMONG A LOT OF PEOPLE TOWARD REFINEMENT. I’M ABOUT TO FUNKIFY THAT.”

BY MARY POLS ILLUSTRATION BY FRANZISKA BARCZYK

BY MARY POLS ILLUSTRATION BY FRANZISKA BARCZYK

Alumnae from across five decades convened in September to share stories of their Bowdoin experiences, both joyful and difficult. They celebrated female leadership and fortitude in the early days of coeducation, in the present, and into the future. When Bowdoin opened its doors to women, the College wasn’t prepared for the actuality of female students. Things had to change. Bowdoin women asked for that change, took the lead in creating it, and continue to embody transformative power as cultural and societal perspectives shift.

DORA ANNE MILLS ’82, P’24 remembers a key moment during her tour of the Bowdoin campus as a high school senior. Like many women of her era, she’d been encouraged to apply by male relatives who were alumni from the days before women could earn a Bowdoin degree— in her case, two uncles.

As the tour circled the Quad and reached the Visual Arts Center, the guide segued into the topic of Bowdoin’s shift to coeducation. In the fall of 1977, coeducation was still relatively new.

Mills listened, thinking that, for the guide at least, there seemed to be a correlation between coeducation and the new art building, which had opened in 1975. This sent a message that Bowdoin expected women students would need and appreciate arty things—soft humanities— and had delivered. “I don’t know how explicit it was,” said Mills, who was planning to major in biology and would go on to earn a medical degree. Today she is the chief health improvement officer of MaineHealth, the state’s largest integrated health care system. “But it definitely made an impression.”

In all likelihood, that was intentional. By the time the Governing Boards voted in favor of coeducation in September 1970, arguably the most monumental moment in Bowdoin’s history since its founding, there had been several years of discussion about what women would want and need from Bowdoin. There was consultation with peer institutions that had already started the process of coeducation—this was a trend nationally—and sharing of findings. An ad hoc committee studying coeducation had said expansion of the College’s art instruction facilities was already advisable, “even without the introduction of women.” With them, it said, “it becomes imperative.”

Women didn’t “necessarily bunch up” in the humanities, the committee said, but the College still might need “to give wider offerings in music, art, and languages.”

From the hindsight of fifty years, it might seem as though Bowdoin’s leaders initially approached coeducation the way a group of Jane Austen’s better bachelors might plan a dinner party.

Women were to be welcomed—there was hope they’d elevate the discourse, smooth out some of Bowdoin’s rowdier edges, and help the College

grow—but what women would want and how they would fit in was a puzzle.

Incorporating women fully into Bowdoin’s culture, both as students and as faculty and staff, would ultimately take a full generation and lots of campus leaders, many of whom honed their skills by pushing back against tradition. This past September, alumnae from across those years, including Mills, gathered virtually for a two-day celebration titled “Leaders in All Walks of Life: Fifty Years of Women at Bowdoin.” They shared stories of both joyful and hard times, and considered the meaning of a fiftieth anniversary and coeducation becoming what some might describe as “officially middle-aged.” “It seems a real corner turned,” said Marilyn Reizbaum, Harrison King McCann Professor of English and the director of the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program.

As tends to happen whenever a vital corner is turned, Bowdoin’s women are looking back at the progress forward. Even for women who loved their Bowdoin experience, who have sent their daughters to the College, or who work there today, not every memory of being a student in those early days is sweet. As they look back, they’re doing so with more awareness than ever of the complexities of gender and sexuality and the essential need for equity and inclusion.

They’re also highly conscious of how impossible it is to separate the time spent at Bowdoin from the eras themselves. In the tumultuous ’70s, Bowdoin was part of a wave of coeducation happening at colleges in the Northeast, including Princeton in 1969, Wesleyan in 1970, Dartmouth in 1972, and Amherst in 1975. The national conservatism of the ’80s was reflected on campus and so too was the shift to a more technology-connected and -driven world in the ’90s and ’00s, as well as the social justice movement of the past decade.

“I think it was no different from any other school that coeducated at that time,” said Melanie May ’82. She never felt excluded or discouraged. She worried more about socioeconomic differences with her classmates than the issue of gender. She had strong friendships with men.

But May and other alumnae also describe some blurred lines. Or, for some, there was

a sense of not fully belonging. And, in some cases, that feeling lingered until the final markers of patriarchal history specific to Bowdoin fell away, including changing the college alma mater from “Rise Sons of Bowdoin” to “Raise Songs to Bowdoin” in 1994; the number of women in the student body edging out men for the first time in 1992; the decision in 1997 to end fraternities; and, finally, the first gender parity of the faculty in 2009.

“I hear more stories as an alum than I ever knew as an undergraduate,” said Bridget Spaeth ’86, who has worked at the College since 2002 and is currently academic department coordinator for earth and oceanographic science. That was one of the reasons she and other organizers of the September events wanted to focus on both the impact of women on the College and the impact of the College on women. The #MeToo movement has changed how many women look at their pasts, Spaeth said. “I think all of us have more language now and some perspective for unpacking all the dynamics in the classroom with faculty, with peers, in social life, leadership, and just student opportunities.” She, like May, points out that in the ways it may have struggled to be truly inclusive of women, Bowdoin was far from unique. “A lot of institutions were dealing with this.”

Coeducation began in earnest with the admission of the Class of ’75, but for several decades, women arrived at Bowdoin without understanding that the process of coeducation might still be ongoing. “I had no perspective,” Kate Dempsey ’88 remembers of her eighteen-year-old self. “Twelve years is actually a really short amount of time in the history of any organization.”

The first woman to serve on Bowdoin’s Board of Overseers, and later a trustee, the late Rosalyne (Roz) S. Bernstein P’77, H’97 described the early women at Bowdoin as “tough” and “gutsy” in an interview before her death. That description fit Bernstein herself. When she joined the board in 1973 she vowed to be a positive presence, never a token. She would not be, as she told then-president Roger Howell when he asked if he could nominate her, a shrinking violet. “When I went to my first meeting, you know, everyone was most cordial,” Bernstein said. “But one guy said to me, ‘I’m very glad to meet you, but, you know, I still think women don’t belong at Bowdoin.’” Fine, she said, then politely reminded him he was in the minority.

And he was. But all the way through the ’70s and ’80s, men like him popped up, often in the pages of the Orient, to express similar views, as if coeducation might still be dropped, like a curricular requirement or an unpopular club, if enough people complained.

In those early years, there were many battles to be fought, from asking for better gynecological care (and birth control) and for resources in athletics to getting protections from sexual harassment to making sure women were treated with respect. Sometimes it was language (referring to a “girls’” team when its counterpart was the “men’s” team) and resolved relatively easily. Cultural issues went deeper, and in many cases, the passage of time was the crowbar that ultimately led to their removal. In those early days, particularly, there were no ground rules around relationships between faculty and students. One woman remembers the awkwardness of receiving an unexpected and undesired marriage proposal from her professor upon her graduation. Another recalls sitting across from her professor at the Chuck Wagon restaurant as he complained about another student who had just broken

up with him. Then there were rumors about a powerful professor who drove more than one woman out of his department, either through snide criticism or outright sexual trespass.

“We knew we had trouble with some professors,” Roger Howell said in an interview about coeducation in 1980, two years after he stepped down from the presidency. Howell was frank about what still needed work (security, facilities, and equal access for women on the faculty) as well as the College’s lack of preparedness for coeducation. “We stumbled through it,” Howell said. “I think with the help of an awful lot of good grace from the first couple of years of students that came through the program.”

Those classes were mighty in spirit but small out of necessity; the College simply didn’t have

“Women were gaining more leadership roles. I feel like we kind of bridged the old and the new.”

—JEN GOLDSMITH ADAMS ’90, P’21

“STUDENT PASSION REALLY IS WHAT GETS THINGS GOING AT BOWDOIN.”

—BRIDGET SPAETH ’86

the facilities for women, including enough dormitory space or places for them to eat. Most students relied on fraternity kitchens for their meals. (In that era, Moulton Union had capacity to serve about 280 students, and Wentworth, in what is now Thorne Dining Hall, could feed about 300.) Generally speaking, Bowdoin’s first women students could eat in the fraternities, but policies varied, with some fraternities drawing the line at full membership or allowing women to live in the buildings. Others fully embraced them; Psi Upsilon elected Patricia “Barney” Geller ’75, P’08, P’12 its president the spring of her first year.

Yet despite such markers of acceptance, the early women at Bowdoin faced some hostility from their male classmates. The Orient polled students about coeducation and published the results in February 1972, along with some choice misogynistic comments. One commenter described “co-eds” as “a bunch of Helens” breaking down the walls of Troy. Another accused them of being wallflowers.

They were never bystanders, though. They took to the classrooms, and they took to the playing fields. A field hockey program began in 1971 and was officially named a team by 1972. It was coached by Sally LaPointe, who was married to men’s coach Mort LaPointe and who initially began coaching as a volunteer. Her first field hockey teams wore cast-off men’s soccer uniforms.

By the time Kate Dempsey arrived in the fall of 1984, planning to play field hockey, the team finally had uniforms, but they were shared with lacrosse, Dempsey’s other sport. Dempsey had formulated social justice instincts during her youth in Philadelphia, and so when she stood in line to get her BCAD gray shirts and shorts from the athletic department, she took note that the men were getting an extra piece of equipment. “Jockstraps,” Dempsey said. “There barely was such a thing as a sports bra then, but I just kept pestering people, like, ‘If the guys get jockstraps, can’t we get sports bras?’”

It was a little thing, she said, but “it was an emblem to me, of just everything. The difference between what the men were getting and what we were getting.” Around her junior year, the man behind the counter finally offered her

“ONE GUY SAID TO ME, ‘I’M VERY GLAD TO MEET YOU, BUT, YOU KNOW, I STILL THINK WOMEN DON’T BELONG AT BOWDOIN.’”

—ROSALYNE(ROZ) S. BERNSTEIN P’77, H’97