PUSHING THE WORK FORWARD

Challenges and rewards in the Rose presidency

WINTER 2023 VOL. 94 NO. 2

28 Hard, Wonderful Life

At Buckwheat Blossom Farm, Amy McDougal Burchstead ’98 and her husband, Jeff, nourish animals, forest, soil, and family in every season.

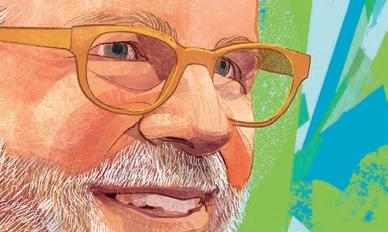

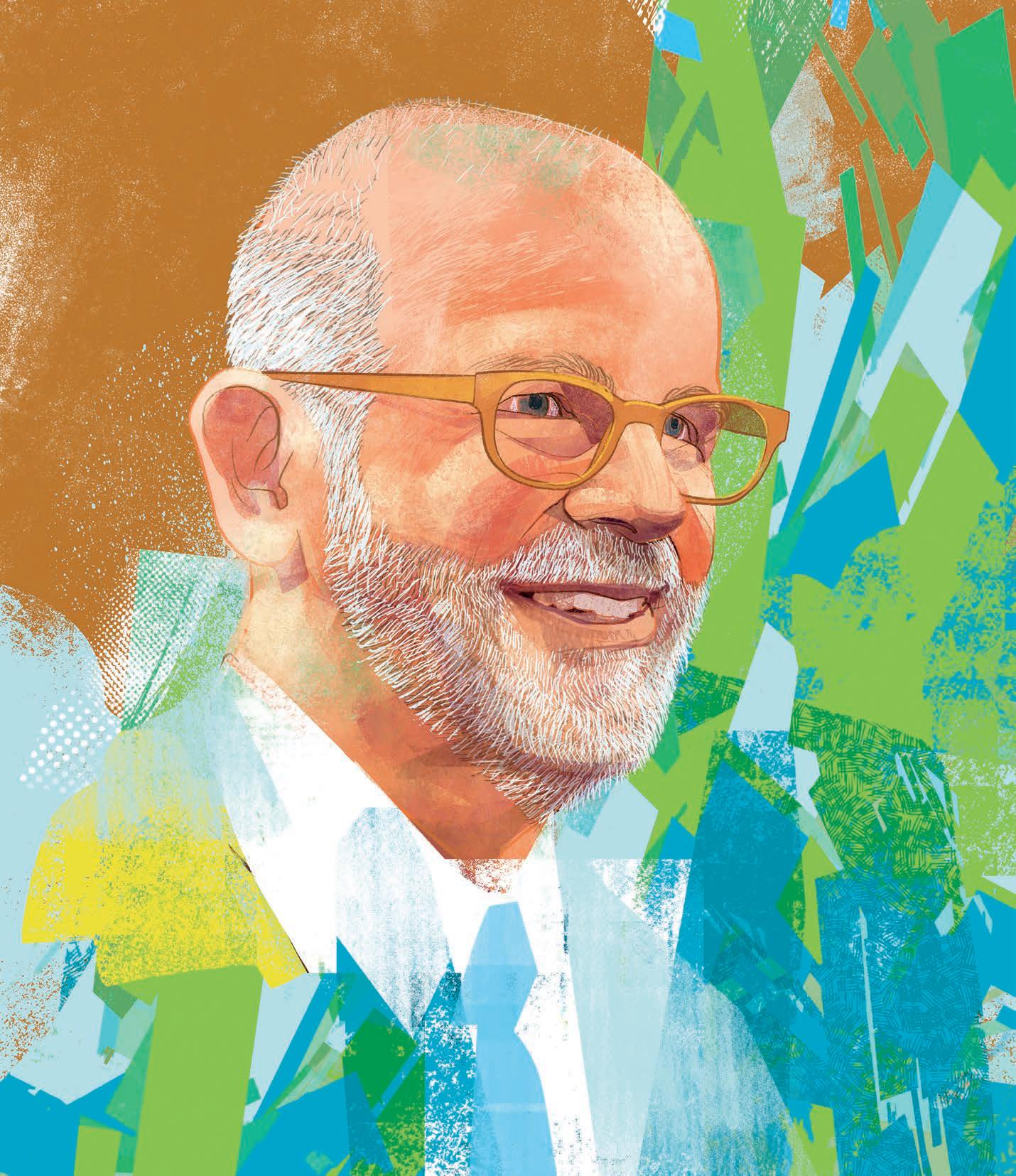

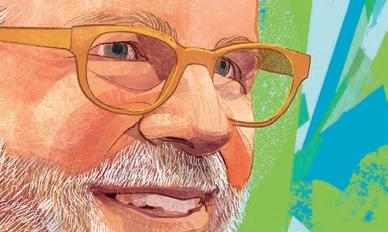

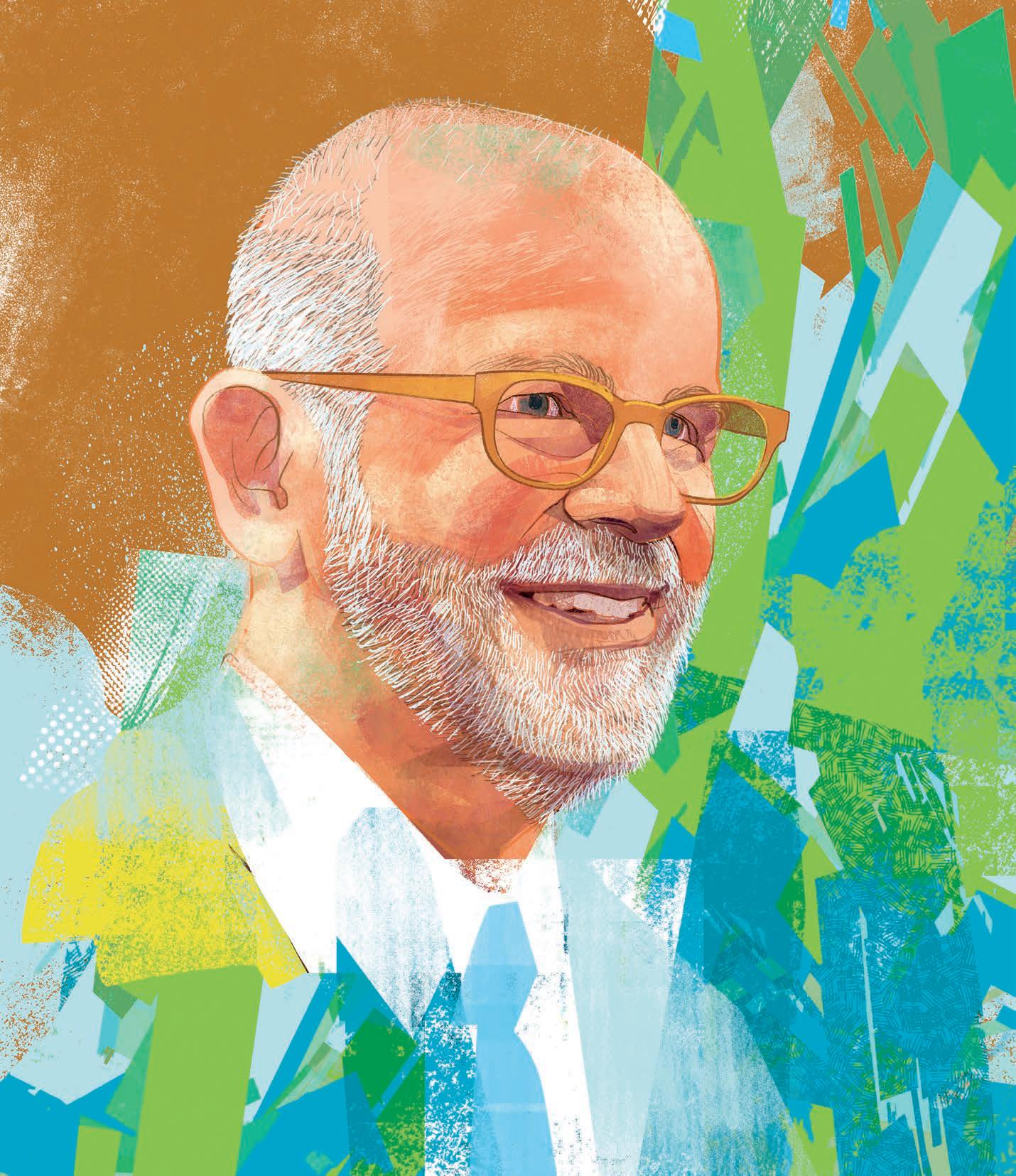

20 Portrait of a Presidency

Clayton Rose reflects on eight years of growth and progress at the College, the challenges and joys of leadership in times of tumult, and why now is the time to step aside.

38 Under Orion

Erica Berry ’14 writes about discovering that she, a nineteenth-century recluse and Bowdoin alum, and the wolves she was studying and writing about were all connected.

44 Q&A

Dean Eduardo Pazos Palma evaluates and adjusts Bowdoin’s social pendulum with the cadence of tradition.

WINTER 2023 VOL. 94 NO. 2

Contents

5 Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity: Debra Sanders ’77 reflects on a career with the FBI.

7 Dine: Bowdoin Dining shares a warming poblano soup from the Just Like Home files.

8 Universal Language: From tiny wind instruments to the pipe organ in the Chapel, Bowdoin offers students hundreds of ways to play and learn music.

10 Searched and Seen: Art from Lyne Lucien ’13 was a featured Google Doodle during Black History Month.

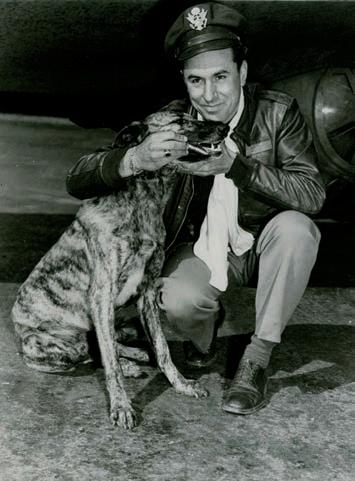

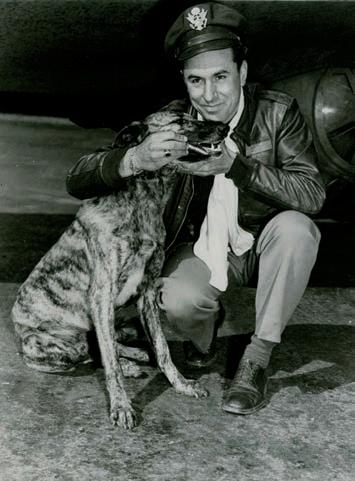

17 A True Shaggy Dog Story: Ian Morrison ’24 helps tell the tale of a man and his dog.

18 Moments with Dad: Doug Stenberg ’79 reminisces on life with Terry Stenberg ’56—his memorable, musical father.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 1 Column Forward Connect In Every Issue 49 Emily Tong ’11 explores—and photographs— the road less traveled. 55 Antwan Phillips ’06 is changing narratives in his home state of Arkansas. 56 Caleb Pershan ’12 took his love for writing and food and mixed up a career. 4 Respond 48 Whispering Pines 64 Here

Winter scene of the campus, taken in 1894, looking southeast from a vantage point in the brand new Mary Frances Searles Science Building. The image is an albumen print, which uses egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the photo paper.

Photo courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

Winter scene of the campus, taken in 1894, looking southeast from a vantage point in the brand new Mary Frances Searles Science Building. The image is an albumen print, which uses egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the photo paper.

Photo courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

Name That Island

I love the cover shot on the Fall 2022 issue! What island is that? I looked around inside the magazine and didn’t see any identification.

Kirk Petersen ’83

Ed. That’s Seguin Island, about two and a half miles from Popham Beach and the mouth of the Kennebec River. A close look reveals Seguin Light, the second-oldest coastal lighthouse in Maine.

REMEMBERING PAT

I just read in Bowdoin Magazine [Fall 2022] that Patricia Grover passed away in June. I worked at the switchboard with Pat while I was a student at Bowdoin. I served on student government, was a campus tour guide, took classes across varied departments, and made a point of regularly eating lunch with people I didn’t know, but Pat still knew more people than I did and always seemed to know what projects they were working on. She had a positive effect on generations of Bowdoin students, and I lament for future generations of Bowdoin students who won’t know her. [To read the rest of the tribute to Pat Grover, see Jared’s comment on her obituary at bowdo.in/grover-obituary.]

Jared Liu ’99

BEAUTIFUL IMPERFECT

I read the article in Whispering Pines of Spring/ Summer [Vol. 93, No. 3] about Earl Gene Ramsey and was surprised and enlightened. I graduated in 1985. At the time it seemed to me that I was one of a tiny number of Bowdoin

students who had a disability. I have cerebral palsy, so I do not walk well. It’s funny how I would never think of asking for any accommodations. I did get a few, like being able to be late to classes, but there were no ramps and there was no accessible housing. I never even thought about accessibility. I remember kind of crawling up steps to class in the snow. When I came to Bowdoin, I did not feel as if I was anywhere near perfect, and most of the people I saw seemed rather perfect to me. I have grown so much in my view of disabled bodies and realizing that we are all imperfect and it is the “flaws” that often make us beautiful. Thank you for publishing that piece. It made me happy.

Liza Polakov-Colby ’85

SEND US YOUR NEWS!

If there isn’t a class news entry for a class year, it’s because we didn’t receive any submissions for that year. We want to hear from you, and so do your classmates! Email classnews@bowdoin.edu or fill out a class news form on our website, bowdoin.edu/magazine.

MAGAZINE STAFF

Executive Editor and Interim Editor

Alison Bennie

Associate Editor

Leanne Dech

Designer and Art Director

Melissa Wells

Design Consultant

2Communiqué Editorial Consultant

Laura J. Cole

Contributors

Mary Baumgartner

Adam Bovie

Jim Caton

Doug Cook

John Cross

Cheryl Della Pietra

Chelsea Doyle

Rebecca Goldfine

Scott Hood

Micki Manheimer

Janie Porche

Tom Porter

On the Cover: Illustration by John Jay Cabuay

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE (ISSN: 0895-2604) is published three times a year by Bowdoin College, 4104 College Station, Brunswick, Maine, 04011. Printed by Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine. Sent free of charge to all Bowdoin alumni, parents of current and recent undergraduates, members of the senior class, faculty and staff, and members of the Association of Bowdoin Friends.

Opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors.

Please send address changes, ideas, or letters to the editor to the address above or by email to bowdoineditor@bowdoin.edu. Send class news to classnews@bowdoin.edu or to the address above.

4 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

Respond

DEBRA SANDERS ’77

FIDELITY, BRAVERY, INTEGRITY

I’ve always loved challenges. From being part of the second class of women to attend Bowdoin and helping establish the women’s sports program (I played field hockey, basketball, and lacrosse) to becoming a special agent with the FBI, I like going outside of my comfort zone and rising to the occasion.

The FBI had always intrigued me, but initially, I was set on the business world, and I started my career in commercial insurance. That changed when a friend read in the Boston Globe that the FBI was looking for candidates. He planned to go to the local FBI office to ask questions and, as a die-hard police-detective, murder-mystery, espionage book junkie, I told him I was going with him.

A couple of years later, I had passed all the rigorous testing requirements and was sworn in. During my twenty-eight years with the agency, I worked in offices in Boston, Tampa, New York City, Honolulu, and Houston, as well as assignments in Iraq, at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, and as part of the Technical Branch working the 9/11 investigation. My favorite assignments were the Joint Terrorism Task Force and working as a technically trained agent. I loved to call my friends from the top of buildings, bridges, and stadiums, where the wind whipped so strongly it could send you over the edge if you got too close, to see if they could guess where I was.

I retired over a decade ago, and my friends are disappointed that I still can’t tell them about all the cool things I did. Today, I am a background investigations contractor, but I still believe strongly in the FBI motto—Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity—and have always tried to live by it. I am proud to have been part of the dedicated, compassionate, ambitious, brave men and women who aspire every day to make a difference.

For more from this interview, visit bowdoin.edu/magazine.

Forward

FROM BOWDOIN AND BEYOND

PHOTO: TODD SPOTH

As part of her role as a special agent with the FBI, Debra Sanders ’77 attended the New England Telephone School, bucket truck training, and classes in carpentry, plastering, and lock picking.

Student Life

A Haven in Crisis

Bowdoin has become one of eight colleges and universities providing a pathway to higher education for students affected by worldwide crises. Launched in response to the war in Ukraine and the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan, the Global Student Haven Initiative helps these students apply to US-based colleges and universities and find support when they arrive.

Bowdoin and other member institutions have committed to providing financial aid for all students with demonstrated need, and access to campus services ranging from housing assistance to mental health support, depending on individual needs. The aim is to help clear a path to higher education for qualified students who are displaced, refugees, or otherwise impacted by war, natural disasters, and other global crises. The goal is to help students overcome these barriers, continue their education, and prepare for eventual return to their home nations.

Maine

A Welcomed Visitor

ON AN UNTYPICALLY warm Saturday in February, ornithologist Nat Wheelwright experienced what most birders only dream of. While at a friend’s private camp along the Black River—far from a throng of avian enthusiasts—he watched a Steller’s sea-eagle fly his way.

“All of a sudden someone in our group gasped, and this bird appeared from out of the pine forest and soared right over our head. It was magical,” says Wheelwright, Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Natural Sciences Emeritus.

With bald eagles on the bird’s tail, the first thing Wheelwright noticed was its sheer size.

“Normally in Maine, bald eagles rule the skies, but in the context of this gigantic Asian sea-eagle, they looked like little crows divebombing a predator,” Wheelwright continues.

Steller’s sea-eagles are about a foot longer and taller—and five pounds heavier—than bald eagles, which are among the largest flying birds in North America. They are also not typical in Maine, to say the least. Native to eastern Russia, some have flown as far east as western Alaska, but none had ever appeared near the Atlantic Ocean. None, until 2021.

Birders enthusiastically followed the seaeagle’s journey, from Alaska in 2020 to Texas, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Massachusetts, and then to Georgetown, Maine, where it first appeared on December 30, 2021.

“As a surprise to no Mainers, its stay in Mass. was short,” wrote Doug Hitchcox, a staff naturalist with Maine Audubon, on the organization’s blog.

This marks the second year the bird—whose sex has not been determined, though male raptors are smaller than females—has returned to Maine. Wheelwright and others find its return promising. It is normal for birds to travel

outside their typical range, an act known as vagrancy. Individual vagrant birds can survive in new territories, though not all do. For example, a red-billed tropicbird, which is normally found only in tropical oceans, has returned to the Gulf of Maine for over fifteen years, but Portland’s famous great black hawk, a native of Central America, lived in Maine for just a year before it got frostbite in its feet and lower legs and had to be euthanized.

“Generally, larger birds have higher survival rates than smaller songbirds, which can be approaching 90 percent mortality during that tough first year,” Hitchcox wrote in the same post.

Wheelwright, a trustee of Maine Audubon, joins many others rooting for the Steller’s seaeagle to thrive in the Pine Tree State.

“Now that it’s returned here, it could easily come back again next winter and do this for the rest of its life,” he says. “And we’re thrilled that it’s kindled an interest in the beauty of wild birds. At a time when we’re all distracted by the worries of the world, what a joy to have this bird come into our lives.”

6 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

Forward

ILLUSTRATION: MICHAEL AUSTIN; PHOTO: ZACHARY HOLDERBY, COURTESY MAINE AUDUBON

A Steller’s sea-eagle seen off Georgetown, Maine.

More than 5,000 miles from home, a Steller’s sea-eagle returned to Maine for the second time.

DID YOU KNOW?

If you asked a person from Mexico what color a poblano pepper is, chances are they would answer “green,” because poblano peppers are often used before they are ripe. As they ripen, poblanos turn bright red. A ripe, dried poblano pepper is called “chili ancho,” which means “broad pepper.”

Creamy Poblano Pepper Soup

Recipe by Bowdoin Dining

Food at Bowdoin is a big deal, and the cooks and bakers who work in Bowdoin Dining Services know how much food matters to students here. In years past, students would submit favorite home recipes to dining, and winning recipes were added to the menu rotations—this soup was one of them.

2 tablespoons olive oil

5 medium-size poblano peppers, diced

¾ cup onion, diced

¾ cup carrots, diced

1 to 2 cups potatoes, peeled and chopped

1 quart vegetable stock

¼ cup half and half or light cream

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon ground black pepper

¼ cup parsley or cilantro, chopped (optional)

Add the olive oil to a large saucepan. Add the poblano peppers, onion, and carrots and sauté over medium heat, stirring, until the vegetables are softened and the onions are translucent.

Add the potatoes and vegetable stock. Simmer until the potatoes are tender, reducing heat as needed. When the potatoes are fully cooked, use an immersion blender to purée until smooth. Alternatively, you can purée the soup in batches in a regular blender, using caution to blend the hot liquid. Add the half and half or cream to the soup in the saucepan. Season with the salt and pepper and heat gently (do not boil). Garnish each serving with parsley or cilantro.

Bowdoin Dining is committed to tradition, local sourcing, and scratch cooking. You can find more than fifty recipes from dining services to cook at home at bowdo.in/diningrecipes.

Dine

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 7

In the fall semester, four students were studying organ, and four were studying harp, both record numbers in the past twenty years.

Did You Know?

Universal Language

The College offers courses in many kinds of music and backs that up with the instruments to play all of it.

Illustration by Rose Wong

In a world of AirPods and ear buds and headphones of all types, Bowdoin’s campus is probably filled, at any given moment, with people traveling through their days to the music of their own personal soundtracks— Beyoncé playing in one carrel in the library and Beethoven in the next, or Harry Styles crossing paths with Kendrick Lamar on the Quad. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called music “the universal language of mankind” in Outré-Mer, his first published literary work, but surely he did not imagine such a multitude of dialects available all at once. Bowdoin’s music program gives students opportunities to learn and play through lessons offered to everyone from total beginners to accomplished performers. Instruments of every type are stashed in 125 storage lockers and just about every corner and closet of Studzinski Recital Hall and Gibson Hall, as well as throughout the office of concert, budget, and equipment master (and keyboardist and composer) Delmar Small.

About 150 students are taking lessons at any given time, and many more are waiting to get an opportunity.

Students can major or minor in music, take lessons, or participate in one of eight ensembles—Chorus, Chamber Choir, Concert Band, Orchestra, Chamber Ensembles, Jazz Ensembles, the Middle Eastern Ensemble, or the West African Music Ensemble—and more than a quarter of all Bowdoin students participate in at least one.

Students taking lessons in voice, guitar, or piano can choose from classical, jazz, and pop.

Forward 8 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

At least five Bowdoin faculty play the saxophone. And many perform—with professional chamber ensembles, the Bangor Symphony Orchestra, the Midcoast Symphony Orchestra, and the Portland Symphony Orchestra.

Lessons are open to all Bowdoin students and include bassoon, cello, clarinet, flute, French horn, guitar (acoustic and jazz), harp, jazz bass, oboe, oud, percussion, piano (classical and jazz), saxophone, trombone, trumpet, viola, violin, and voice (classical and pop/jazz).

The department has many specialty collections like ewe drums, handbells, a Chinese zither, and other international instruments, and Renaissance and Baroque reproductions, including a lute and a consort of krummhorns.

The oldest instrument is a clarinet built by Aston & Co., London, around 1796, and the College owns a recorder built by alumnus and music major Friedrich von Huene ’53.

Among the 596 instruments that Bowdoin owns are 123 drums, 49 pianos, 6 cellos, 4 drum sets, and 3 pipe organs.

The biggest, loudest, and most valuable Bowdoin instrument is the pipe organ in the Chapel, built by the Austin Organ Company in 1927. Two of the smallest are a siren whistle and a sopraninino recorder.

The oldest instrument is a clarinet built by Aston & Co., London, around 1796, and the College owns a recorder built by alumnus and music major Friedrich von Huene ’53.

Among the 596 instruments that Bowdoin owns are 123 drums, 49 pianos, 6 cellos, 4 drum sets, and 3 pipe organs.

The biggest, loudest, and most valuable Bowdoin instrument is the pipe organ in the Chapel, built by the Austin Organ Company in 1927. Two of the smallest are a siren whistle and a sopraninino recorder.

Bowdoin Goes West?

TRAVEL NEARLY 2,000 miles west from campus, and you’ll find yourself at another Bowdoin—Bowdoin National Wildlife Refuge—in Montana. The similarity, though, ends at the spelling.

This Bowdoin is pronounced bow-doyne, and according to Lori Taylor, a curator at the nearby Phillips County Museum, is named after Louis Beaudoin, a surveyor for the Great Northern Railway, who suggested they call the lake the park is named for after himself.

“When it was recorded, they changed the spelling to ‘Bowdoin,’” she says.

The location was originally planned to be one of the stops on the famous rail line, on the same section that included other names inspired by places around the world and the Northeast, including Oswego and Nashua. It never came to fruition, though, which is good news for the more than 260 species of birds that have been documented on the 15,550-acre refuge, including piping plovers, willow flycatchers, and arctic terns.

Though merely speculation, we like to believe the spelling may be due in part to Bowdoin grad Paris Gibson, class of 1851, who was founder, first mayor, and namer of nearby Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was friends with Great Northern Railway founder James J. Hill and introduced Hill to the region—even convincing him to extend the northern line to his city.

Sound Bite

—TOSHI REAGON, BOWDOIN’S 2022–2023 JOSEPH MCKEEN VISITING FELLOW, IN A CONVERSATION ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES FACING THE PLANET DURING THE EVENT “MOTHER VOICES: TRANSFORMATIVE INTERGENERATIONAL JOURNEY.”

Alumni Life

SEARCHED AND SEEN

Google featured artwork by Lyne Lucien ’13 as its home page doodle on February 8, 2023. Lucien’s artwork celebrated Mama Ca-x, a Haitian American model and advocate for people with disabilities who challenged the fashion industry’s standard of beauty by proudly showcasing her prosthetic leg on the runway and was part of Google’s observance of Black History Month. Alumni also saw Lucien’s artwork closer to home recently in the spring/summer 2022 issue of Bowdoin Magazine.

10 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Forward PHOTO: US FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE; ILLUSTRATION: LYNE LUCIEN ’13

“If there was ever a time to run out of your house flying toward the light, this is it.”

Other Bowdoins

President Franklin D. Roosevelt established Bowdoin National Wildlife Refuge in 1936, originally as a migratory waterfowl refuge.

Orienting a Career

THE BOWDOIN ORIENT has a reputation for pursuing thorny topics that can put administrators on edge. Over its 150 years of operation, it has honed the skills of many cub reporters who have gone on to impressive journalism careers. An informal survey revealed that more than 120 Orient alumni who graduated between 1979 and 2020 are working as reporters for outlets like The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and the Boston Globe. (Scott Allen ’83, for one, oversees the Globe ’s famous investigative Spotlight Team.) Jane Godiner ’23, an aspiring journalist herself, recently interviewed a few of these alumni to ask how their time at the Orient influenced them.

ESPN sports analytics writer Seth Walder ’11, a former Orient sports editor and editor-in-chief, credited the student newspaper for helping to launch his career. “The Orient was a really foundational way for me to build skills. The fact that we were doing this paper every week, very much independently, forced me to learn,” he said. “When I left Bowdoin, there was plenty more to learn in the ‘real world,’ but I had built up skills from the Orient that were certainly helpful right away.”

Evan Gershkovich ’14, a former Orient contributor and current Russia-based reporter at The Wall Street Journal, said his time at the Orient was not only characterized by camaraderie, but by professional development. “I remember a friend of mine basically sitting me down and teaching me the mechanics of a news story, from the lede to the nut graf,” he said. “My friends at the Orient were very serious, driven people. They took what they did seriously, and they helped me learn more about what journalism truly is.”

Student Life Talk Therapy

In a recent episode of “Blooming Daily,” a wellness podcast that Ruth Olujobi ’25 started last year, she turns her attention to relationships. “We think about how our diet affects our health and how exercise affects our health, but how do relationships affect our health?” she asks—before conceding that, as a sophomore, she’s not quite an expert in this department yet. Olujobi, a pre-med student, launched the podcast to channel her passion and energy around health and wellness, particularly for young people and underserved communities.

“Blooming Daily” is one of two prominent student podcasts that focus on “what it means to be well, and not well, too,” said Bowdoin’s wellness director Kate Nicholson. Connor Lloyd ’23 began his show, “The Things I Haven’t Even Told My Therapist,” in 2021 to offer “semi-comedic and all-too-honest firsthand examination of what it means to navigate society, college, social life, and athletics when struggling with mental health.”

Kimberly Launier ’98, a producer at CNN who has also worked on documentary film and television productions with ABC News and HBO, said she appreciated the chance to work with fellow students who were “smart, empathetic, kind, and diligent.” She added, “I’ve been so lucky, and also worked incredibly hard, to have one of the most truly fun careers I ever could have imagined. I’ve had the time of my life having adventures with unforgettable people and creatures. And it all started at Bowdoin.”

Nicholson shared the two podcasts with the Bowdoin community during the fall semester, urging students to tune in. “I hope these voices and resources offer reassurance and good company in your remaining weeks,” she said.

For Lloyd, speaking into the microphone has been a healing exercise. “Making this show has been as therapeutic for me as I hope it has been for you,” he said.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 11 PHOTO: (WALDER) COURTESY ESPN; ILLUSTRATION: ANNA &

BALBUSSO

ELENA

Alumni Life

Listen to “Blooming Daily” on Spotify and “The Things I Haven’t Even Told My Therapist” on Podbean.

Faculty

Nod from a Nobel

A FULL-CIRCLE MOMENT brought Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Danielle Dube to Sweden in December to witness the Nobel Prize ceremony. Dube was a PhD student of chemist Carolyn Bertozzi in the early 2000s at the University of California–Berkeley, where both worked on research into bioorthogonal chemistry (which refers to any chemical reaction that can occur inside of living systems without interfering with native biochemical processes) that later caught the attention of the Nobel Committee. Now at Stanford University, Bertozzi, one of three 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureates, invited Dube to Stockholm for the award ceremony, during which she thanked Dube for her direct contributions. “Celebrating Carolyn’s Nobel Prize was a highlight of my career and a once-in-alifetime experience,” said Dube.

Game On

THREE-PEAT

Bowdoin’s women’s rugby team outmatched the University of New England, 29-0, to win the 2022 NIRA Division III championship on November 19, 2022, at Dartmouth College. This is the third straight championship title for the Polar Bears, who also took the top spot in 2019 and 2021 (there was no championship in 2020 due to the pandemic). The women’s rugby team ended its season with eight wins and only one loss.

12 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU Forward ILLUSTRATION:

SANDRA DIONISI; PHOTO: COURTESY NIRA/MARK WASHBURN

Connections

CULTURED LOAVES

Every Wednesday, Bowdoin bakers use a 125-year-old starter to make forty loaves of sourdough bread. The starter was a gift from Matthew Booker, an associate professor of history at North Carolina State University, during a 2019 visit to campus to talk about the Global Sourdough Project, which traces the genetic sequence of microbial organisms found in hundreds of starters—also known as cultures.

“Feeding sourdough that feeds us binds together and pairs human and microbial cultures in a multi-species community,” he wrote in a blog post.

The particular culture baked into the loaves served at Thorne and Moulton Union can be traced back to a culture Booker’s ancestors received from a prospector in Kodiak Island, Alaska, in 1898, and has since traveled to Oregon, Washington, California, North Carolina, and now Maine.

“It’s actually amazing when you think that generations of people have baked bread with this same starter,” says Adeena Fisher, associate director of dining. “Baking a loaf of bread is a labor of love, and we are honored to be part of this tradition.”

Campus Life

ArtChopped

Senior Class Dean Roosevelt Boone joined forces with Assistant Director of Student Activities Eunice Shin ’22 to develop a program that was fun and competitive, and that provided “an opportunity for student-athletes and nonathletes to come together in fellowship,” Boone said.

Inspired by the Food Network reality television show Chopped, the event featured four Bowdoin artists— two athletes and two nonathletes—competing to produce a winning piece of art from the same set of art materials and in a time frame of thirty minutes. Shin and Boone chose “glass ceiling” as the theme, hoping, as Shin says, “that students would take the theme and run with whatever creative force against barriers they were working to break through.” When time was up, each artist had a few minutes to explain their piece to a packed house, Thursday night audience in Magee’s Pub and to a panel of student judges. All four of the artists—Alfonso Garcia ’25, Katherine Page ’23, Shumaim Rashid ’26, and Carl Williams ’23—chose to paint, even though they brought strengths in different media to the event. Garcia came away the night’s winner, taking home a $50 gift certificate to Portland Pie.

ArtChopped was such a success that Boone and Shin are planning another iteration soon, possibly even before the semester is out. “The students were really enthusiastic about an opportunity like this that brought them [athletes and nonathletes] together,” Boone said. “They want more of that.”

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 13 PHOTOS: (BREAD) OKSANA MIZINA; (GARCIA) COURTESY BOWDOIN DIVISION OF STUDENT AFFAIRS

Alfonso Garcia ’25

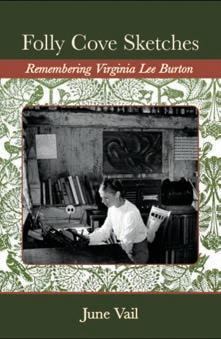

On the Shelf

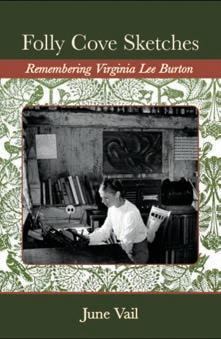

Folly Cove Sketches: Remembering Virginia Lee Burton

JUNE VAIL

(Custom Museum Publishing, 2022)

In her new memoir, Professor of Dance Emerita June Vail paints a warm, honest portrait of her great aunt Virginia Lee Burton, the author and illustrator of the beloved midcentury children’s book Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel.

On Stage

Enduring Racial Challenges

Guest director presents A Raisin in the Sun.

The Path to Successful Community School Policy Adoption

EMILY LUBINS WOODS ’95 (Routledge, 2022)

When the House Burns PRISCILLA PATON ’74 (Epicenter Press, 2023)

RENOWNED New York–based theater artist Craig Anthony Bannister was invited to direct the recent production of the groundbreaking 1950s play, A Raisin in the Sun, at the Wish Theater.

This is the first time Bowdoin has featured a Black-authored play with a Black director and a majority Black cast, says theater professor and department chair Abigail Killeen. “We’re so grateful Anthony chose to accept the offer to work with us. Bringing in regular guest directors and choreographers of color is a key component to fostering strong and inclusive learning in theater and dance,” she explains.

The first Broadway play written by a Black woman, A Raisin in the Sun, by Lorraine Hansberry, made an impact with audiences and critics when it premiered in 1959, dealing as it did with issues like racism and housing discrimination. The story revolves around the fortunes of an impoverished Black family in Chicago and their efforts to seek a better life.

Driving the Green Book: A Road Trip through the Living History of Black Resistance

ALVIN HALL ’74 (HarperOne, 2023)

In Search of Justice in Thailand’s Deep South

Edited by William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of the

Edited by William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of the

Humanities

Emeritus JOHN HOLT

(University of Virginia Press, 2022)

“Even in 2023 this play is still very relevant,” says Bannister. “As African Americans, we continue to grapple with questions like ‘Where do we belong?’ and ‘How do we achieve our dream?’”—questions, he says, that are central to the theme of the play.

Many of the cast members are new to the stage, explains Bannister, which is fine because this play is a “good entry point” for novices wanting to get into acting. “You don’t really need to have an incredible amount of acting technique to tell the story, because it’s so easy to relate to.”

14 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS/FRIEDMAN-ABELES

Forward PHOTO:

Stage debut of A Raisin in the Sun, featuring Sidney Poitier, in 1959.

Faculty

PIECE OF MIND

Clinical and philosophical psychologist Barbara Held has opinions, and thanks to op-ed pages near and far, readers across the country are privy to her professional insights—no couch or copay required.

Held, Bowdoin’s Barry N. Wish Professor of Psychology and Social Studies Emerita, has opined about confirmation bias—that is, the tendency to accept dubious information if it supports preexisting beliefs—about morality and the cost of doing what is right, and about her own defensive pessimism, repressed Nutcracker memories, and lessons learned from Gus, her parakeet.

She has published nearly thirty pieces since the beginning of the pandemic in spring 2020, when isolation, an endless supply of cable news, and a love of writing converged to give rise to a series of 800-word platforms for her scholarship, experience, and direct, in-your-face approach.

“With all that time on my hands I became a bigger news junkie than I already was,” she said. “As soon as I heard a story that interested me and about which I had something to say, I would run to the computer to start typing.”

Held says truth and its exposition have been themes throughout her life and work, so it’s no surprise that, no matter what an op-ed’s topic, truth always finds a way into it.

“The more you’re scared to tell the truth, the more you need to tell it,” Held wrote in one of her op-eds. “If you don’t, you just might create a monster even scarier than the truth.”

From Oceania to Maine

An exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art highlights an 8,000mile artistic journey.

MADE LARGELY from natural fibers, shell fragments, and wood, these masks are fragile, says curator Casey Braun. She’s talking about the objects on display in the exhibition “Masks of Memories: Art and Ceremony in NineteenthCentury Oceania.” It highlights a number of masks collected in Oceania in the 1890s by Harold Sewall, of Bath, Maine. He then brought them back to the US—a journey of more than 8,000 miles—and donated them to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Sewall was US Consul General to Samoa at the time, and the artifacts were purchased in New Ireland, today part of Papua, New Guinea.

These masks, Braun explains, were each commissioned by family members of a deceased person to be worn at the funeral. “They were not designed to be kept and were

usually discarded or burned after the ceremony, which makes it all the more extraordinary that they found their way here.”

This also means Bowdoin has one of the few collections of such artifacts obtained in the nineteenth century, says Braun. As well as examining the cultural significance of the masks and their associated practices, she adds, the exhibition, which runs until July 16, explores the circulation of such objects beyond Oceania through the activities of overseas art collectors.

“This has led to some lively conversations about the way artifacts can be used to create myths about the non-Western world, and the place such objects have in American and European museums.”

Above: Mask, nineteenth century, wood, pigment, fiber, and shell, by unidentified artist, New Ireland. Gift of Harold M. Sewall, Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 15

ILLUSTRATION: JAMES STEINBERG; PHOTO: COURTESY BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART

For a compilation of Held’s published op-eds, visit bowdo.in/held.

On View

5th 475

100 20 5 7 45

6 500

LACING UP THEIR BOOTS

Finding a job—especially that first one—requires specific skills. For three days in January, the sophomore class returned to campus to take part in Career Exploration and Development’s (CXD) Sophomore Bootcamp, a program designed to equip students to land the kind of internships and first-job experiences that will catapult them into successful careers of meaningful work. Bootcamp, as the name suggests, is intense. From nine to five each day, students learn, workshop, and drill the skills they’ll need to enter the work force. They also learn to leverage the power of the Bowdoin network. CXD matches each sophomore with two alumni to start connections, if only in practice, toward networking conversations. Bootcamp’s mission is to impart both practical know-how and to convince students their dreams are in reach. “We hope every student leaves more confident about what they can pursue,” says Bethany Walsh, CXD’s senior associate director and advisor. “It’s really important to us that every student knows how to leverage this amazing Bowdoin education they’re getting in the way they want to.”

like networking, writing cover letters, and searching for jobs and internships. sophomore class, now participates.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU ILLUSTRATION: DAN BEJAR

Internships

A True Shaggy Dog Story

WHEN HE BEGAN his internship at the Massachusetts Historical Society last summer, Ian Morrison ’24 wanted to produce a podcast about some aspect of World War II, but had no intention of focusing on a dog. In fact, he had never heard of Thunderbolt. “Initially, I was drawn to the story of his master, Lieutenant Robert Payne, whose papers are in the MHS collections,” explains the history and Francophone studies double major.

Payne was a US bomber pilot flying out of England in 1943. “I am very interested in the Second World War,” says Morrison, “so I wanted to work with Payne’s papers to learn more about the war through his personal experiences.” As Morrison combed through the archives, he encountered the story of Payne’s dog, Thunderbolt, mentioned in letters, newspaper clippings, and other materials—it was a story that really captured the public imagination at the time, he says.

During the thirty-five-minute podcast, we learn how Lt. Payne befriends this scruffy, eighty-two-pound mongrel that had started hanging around the airbase. Payne names the dog Thunderbolt, in honor of the P-47 Thunderbolt fighter escorts that would accompany bomber crews like Payne’s on their raids over occupied Europe. Thunderbolt and Payne become constant companions, says Morrison. The dog even occasionally joins the crew on practice flights.

In November 1943, when Payne’s aircraft fails to return from his nineteenth mission, Thunderbolt is grief-stricken, waiting for days for his master’s plane to show up and sleeping on Payne’s bed surrounded by his possessions. Thunderbolt’s war is not over yet, however. The animal is eventually adopted by one of Payne’s fellow officers, following him to mainland Europe in 1944, where the dog was reportedly wounded in action.

There is a happy ending, at least for a while, says Morrison. Thunderbolt survived the war, as did Payne, who ended up in a German POW camp after being shot down. The two reunited in 1946, and Thunderbolt lived with Payne and his family in the US for five years, until the dog was hit by a dump truck and died.

“I now have a greater appreciation for the level of work that goes into making a podcast,” says Morrison. As well as poring through material in the MHS archives, he interviewed two historians about the role of dogs in human history. Morrison also had to learn audio recording techniques.

During his internship, which was funded by Bowdoin’s Office of Career Exploration and Development, Morrison came under the guidance of Bowdoin history graduate Kanisorn Wongsrichanalai ’03, director of research at the MHS. “It was great to connect with a fellow Polar Bear,” says Morrison, who intends to pursue a master’s in library science after Bowdoin.

Athletics

PASS IT ON

In a happy coincidence, all three head coaches of the women’s basketball teams on hand at Morrell Gym the weekend of National Girls and Women in Sports Day were former Bowdoin players—a testament to both the inspiration and the powerful network of former Bowdoin women’s basketball coaches Adrienne Shibles and Stefanie Pemper. All three are also Maine natives. Bowdoin’s head coach, Megan Phelps ’15, is from Southwest Harbor; Alison (Smith) Montgomery ’05, head coach of the Bates women, grew up in Stockton Springs; and Jill (Henrickson) Pace ’12, head coach for Tufts, is from Bath.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 17 PHOTOS: (PAYNE AND THUNDERBOLT) COPYRIGHT MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY; (BASKETBALL) HEATHER PERRY

Payne and Thunderbolt

Meet Thunderbolt, a WW2 bomber pilot’s canine companion.

Moments with Dad

Doug Stenberg ’79 reminisces on life with his memorable, musical father.

AN OBITUARY can list the accomplishments of a man but rarely gets to the soul of his story, especially for the loved ones and friends he leaves behind.

My father, Terry Douglas Stenberg ’56, was profoundly driven, and his accomplishments are formidable. His 2,000-word obituary listed so many of them: His perfect pitch. Attending Bowdoin, where he was a Meddiebempster. Joining the military and rising to the rank of captain. A career in education, including twenty-four years as a headmaster—fifteen of them at Hawken School. A stint as director of the American Collegiate Institute in Izmir, Turkey, where he was diagnosed with colon cancer. Holding volunteer positions with various boards. Writing five major pieces for two different instrumental ensembles, including “Remembering Tilly.”

These accomplishments are in black and white compared to the technicolor memories I have of him—and of us, together. Reading a draft of the obituary the year before he died, I was reminded of how much time had been lost over the years, how many moments slipped through those lines. How many school evaluations, for example, did it take to make a life?

I wasn’t there for those, my memories hovering just around the periphery: The way he used to call out “Hi-o” when he came home from work, and my sisters and I would run to greet him. His returning home from active duty, and how I cried in his bedroom when I thought he might have to go to Vietnam. The faculty parties he and Mom hosted, where downstairs was full of upbeat cacophony, and I could make visits to the kitchen for chips and chocolate chip cookies.

The more vivid moments are the ones we shared together: Our unbridled joy when he taught me to ride a bike at Pine Manor. How

happy we were when I got into Bowdoin, and how he consoled me when, having lost a wrestling match at sectionals, I was at the end of my tether physically and emotionally. The times a few years before he died, when we would drive down to get lobsters in Cushing or when we would watch a Red Sox game together. Or toward the end, sleeping on the floor of my parents’ living room and waking to the sound of a cowbell, which Dad rang to call for help. We held onto each other as we inched our way across the rug, Mom still asleep in their bed.

The most vivid, though, are our conversations. Over the years, we had many about our shared alma mater. In talking about Bowdoin, in some ways, Dad and I were talking about something very close to our hearts. Even when talking about what was currently happening at the College, we were simultaneously reaching back into the past and toward a future.

Bowdoin was a liberating time for him. His family of origin were Christian Scientists, and Bowdoin was the place where he chose a different path. The most definitive experience for him

18 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU PHOTO: COURTESY DOUG STENBERG ’79 Column

Terry Stenberg ’56 and his son, Doug Stenberg ’79, with their dog, Thor, circa 1975.

in many ways was touring US military bases in Europe with the Meddies. It allowed him to see the world in a brand new way.

I rarely saw him happier than when he got together with fellow alums. I grew up listening to recordings of fellow Meddie George Wheeler Graham’s solo of “Ding Dong Daddy from Dumas” and Norm Nicholson’s sublime rendition of “The Lord Is Good to Me.” Other members—and aspiring members—visited us while I was growing up. One year, Bob Keay ’56— one of the aspiring members—regaled us with “Nature Boy,” as we sat around our large antique dinner table. We all broke out into applause— my dad the most enthusiastic of all.

When he and Mom spent three years in Turkey, we communicated mostly by letters, except for when he was diagnosed with cancer. I was teaching in Seattle at the time, and I called him from a pay phone in a quiet café not far from the Northwest School. I told him that I loved him and that he would get through this, and the family would too. Mildly earnest patrons respectfully ignored me blubbering into the phone.

Life is all about mysteries and ironies. In the ’90s, we actually ran into each other at an airport somewhere in Germany—maybe Frankfurt or Hamburg. I was waiting for a connecting flight to St. Petersburg. Dad was running a school in Izmir or doing a school evaluation in Germany.

know I mentioned John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, but I did not dwell on July 4th, fifty years after the Declaration of Independence was signed, when they both passed away. He died the next day. It’s very strange to think about that being a conversation, but it was still a form of communication. Of love.

I think sometimes that simple act of trying to have a conversation is the point. The Constitution was written to be a living, breathing document that evolves with us. Just like our relationships—if we make the effort for them to be ongoing and evolutionary. It’s worth it to find the stories we didn’t know, such as a photo found over sixty years later of a father reading to a son, when his memories are essentially of his mom doing that. Or the recollection of a particularly difficult meeting with a board member, who, when informed that my dad had to meet with me at a certain time, said “Sons can wait,” and my dad responded, “Mine doesn’t.”

Growing up, I picked up on what Bowdoin had meant to him. I originally was following his paradigm. I, too, joined Beta. I became a Meddiebempster. He was always proud of me for being involved in sports, and I joined the football team.

As the son of a headmaster, I was always very conscious of trying to toe the line. Oddly, failing a British history course while studying abroad in England was a crucial experience for me and allowed me to break away from his paradigm a bit. I failed history, but I took a course on a Shakespeare program in London. When I returned, I eventually did a two-man performance of Macbeth with Peter Honchaurk ’80 in the basement of Pickard Theater. Herb Coursen praised the production in Shakespeare Quarterly. I also focused on Russia to study the language and literature and then pursue grad school before becoming a teacher, in some way returning to the paradigm.

My memory is fuzzy on those details. What I remember clearly is seeing him sitting in a secluded gate that was mostly empty. I couldn’t believe it. I wasn’t allowed to sit with him, but we were able to be close enough to talk, and we had a good conversation.

I wonder sometimes if he had been wired differently or if I had been wired differently, if we could have had more moments like that, of natural, spontaneous closeness. I think he tried through his music. I tried through sharing movies. It wasn’t always easy, and communication wasn’t always consistent.

I called him for the last time on July 4, 2020. He was in hospice, and Nurse Diane held the phone to his ear. Apparently, he moved his hand at the sound of my voice. He couldn’t talk. I don’t remember much because I was just so conscious of knowing he was about to die and focused on the sound of his labored breathing. I’m certain I expressed my love for him. I

Reflecting back on our life together, there are plenty of things I wish we had both done differently. Now, I am able to more clearly see the outline of his life, and how for so much of his life he may have been trying to prove something to his biological father, Charlie McClain, who had been cut out of his life since he was four. He broke that paradigm for both of us. Though he had so much professional drive, I can’t say that I ever felt pressure from him. I felt more approval when I did certain things, but never pressure to achieve. Certainly, I was not like one of my classmates, who went on to be very successful but whom I found weeping in a dorm because his grades were average and his dad had said, “If you get four H’s, don’t come home.”

It’s all those moments—both remembered and discovered along the way—that get left out of the obituaries, no matter how detailed and impressive. They also happen to be the ones most worth remembering.

For roughly thirty years, Doug Stenberg ’79 taught in schools, colleges, and universities from Seattle to St. Petersburg, Russia. His favorite acting roles have been Macbeth, Caliban, Jaques, Feste, Bottom, and Scrooge. To read his father’s obituary, go to obituaries.bowdoin.edu/terry-d-stenberg-56.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 19

I wonder sometimes if he had been wired differently or if I had been wired differently, if we could have had more moments like that, of natural, spontaneous closeness.

With just a few months to go as Bowdoin’s fifteenth president, Clayton Rose reflects on eight years of growth and progress at the College, the challenges and joys of leadership in times of tumult, and why now is the time to step aside.

PORTRAIT OF A PRESIDENCY

BOWDOIN: In your time as president, what’s changed at Bowdoin, what’s the same, and what are you most proud of?

ROSE: I’ll start with what’s the same. We deliver an outstanding liberal arts education. We prepare our students to be leaders in a changing world. Our faculty and staff are devoted to our students and dedicated to the mission of the College. Our alumni are fantastic in the way they support the College and one another. And the values of treating one another with respect, of kindness, of collaboration, of the notion that there is an obligation that extends beyond ourselves because we’re privileged to be here— all of that is the same.

INTERVIEW BY SCOTT HOOD

ILLUSTRATION BY JOHN JAY CABUAY

For change, I think the broad Bowdoin community—alumni, parents, faculty, staff, students—has a better collective sense of the big social and cultural issues that affect the College and the world. That’s probably the biggest change. A better understanding. Not that everybody agrees. In fact, it stirs the waters more, but a more transparent understanding of the cultural and social issues as they play out on campus.

What am I most proud of? There’s a lot—it’s not about me, though, because so many people are involved. We’ve improved and expanded

financial aid, strengthened the academic and curricular programs, and we’ve made real progress—with a lot more to do—on building a community where everyone has the opportunity to belong, to know they belong, and to pursue the same successes, outcomes, and lived experiences. And we’ve worked hard to advocate for and to create the opportunities for respectful engagement with ideas that challenge our own, and to have a variety of viewpoints represented on campus.

Applications are at a record high, career services for students are much stronger, and we’ve put amazing pieces together that position Bowdoin as a national leader in the teaching and study of the interconnected issues of the environment, oceans, climate, and the Arctic— something truly unique and relevant.

I’m also proud of the work we did to improve governance and restructure the board, of the work of our senior team, and the way the larger community has come together to make our campaign such a success and to support the College every year in a way that we see at few other schools. And then there’s COVID—not something any of us could have predicted, but the way the College pulled through the pandemic ought to be a point of pride for everyone.

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 21

BOWDOIN: Seems like a great time to be president of Bowdoin College. Why leave now?

ROSE: It is a great time. The College is stronger than it’s ever been across virtually every dimension. We’ve moved back into the regular rhythms of campus life, and there’s a real foundation in place from the work we’ve done over the last seven and a half years to build upon. It will take time to craft the next steps and then make them real. And that’s what makes now the time for me to step aside.

BOWDOIN: Does COVID have anything to do with it? Would you still be leaving if COVID hadn’t happened?

ROSE: It’s an impossible question to answer. Am I burnt out because of having to manage through COVID? No. It was hard, but it was hard for everybody around the world.

BOWDOIN: But the pandemic also caused a lot of people to step back and take stock of their lives and to think about where they want to be; how they want to spend their time.

ROSE: Sure, but there’s nuance to that. I do want to spend more time with my grandchildren. I have very close friends I haven’t seen for two and a half years. And this is a 24-7 job. So the recognition that the clock is ticking and that we’re not totally in control of our destiny, that’s a real part of the pandemic—a healthy part of reflecting on it.

The bigger thing for me is that there’s a great deal of work that we’re doing around the “K Report” [Report of the President’s Working Group on Knowledge, Skills, and Creative Dispositions], diversity, equity, and inclusion, the development of facilities around the oceans, Arctic, climate, and the environment, among others, that set the table for even bigger programmatic efforts. We’re at a place where we need to establish the next phase of work to take the College to the next level, and that requires another eight, ten, twelve years to really move the needle forward. So either I have to commit to be here for that time to see this work through, or I’ve got to get out of the

way and let somebody else come in and do the work, but not hang around the net for another couple years just to hang around the net. That makes no sense.

COVID created a natural break point. If COVID hadn’t happened, some of this work would have been pushed to the next level naturally and it would have been a different time frame. Maybe it would have been another three or four years.

I think a president has a responsibility to know when the moment comes. This is a hard one for Julianne and me personally. We love being here and being a part of the life of the College every day, but from an institutional perspective, it’s the right time.

BOWDOIN: When people look back at your time as president, the pandemic is going to be one of the “big things.” Earlier in your career, you managed people and organizations through emergencies or crises. Good preparation for leading the College through COVID?

ROSE: Sure, but I also think we ought to acknowledge that there are lots of leaders in higher ed who didn’t have that background but who did just fine.

BOWDOIN: But you were making decisions before most of the others. Bowdoin was one of the first colleges to move to remote learning.

ROSE: The level of uncertainty is similar to what I experienced earlier in my career. There’s a lot you don’t know, but potential bad outcomes could be really bad. And so, if you have an expected outcome or the probability of a bad outcome that’s higher than you would like and a lot of uncertainty, that’s when you want to err seriously on the side of caution and not assume too much, because you just don’t know. That was also true in some of the things I did before with serious financial and economic problems that weren’t about life and death.

You just gather as much information as you can from as many people as you can. You try to listen way more than you talk. And, ultimately, you have to use judgment. You’re not going to stumble on “the answer.” And there is no

perfect or optimal answer. There’s just the best path you can take at that moment.

BOWDOIN: You’re not a scientist or a physician. How did you synthesize everything?

ROSE: Lots of listening—the more the better. The more ideas, the better. It’s taking as much in as you can from people who are experienced and smart—recognizing that no one has the answer—and then making judgments.

The thing that I can do—that I have responsibility to do—is to decide how all of that matters in the context of our community and the goals we’ve set for ourselves in our community. Ultimately you make judgments. And you’re making some decisions about what you think is going to happen with the virus and where it’s going to go. The best example of that was [the] Delta [variant of SARS CoV-2]. I mean, in the summer of ’21 we had that magic three weeks where we thought everything was going to be great, and it’s all gone. And then we got whacked upside the head, and in very short order realized that we are back in it. You have to be prepared to change your mind and not let your ego get in the way.

BOWDOIN: And everybody’s looking at you for reassurance.

ROSE: Sure.

BOWDOIN: So you can’t freak out.

ROSE: No. You don’t have the luxury for that. And it doesn’t do any good anyway. You have to recognize that every time you’re on a Zoom call with a group or sitting in a meeting, whether it’s with the board or the senior team or the staff, they’re looking at you and looking for leadership, looking for honesty and transparency, and looking for hope. People want to know what the truth is, and they want to know there’s a way home, and even if you don’t exactly know the way home—that somehow you’ll get home. So, those are things to always keep in mind.

BOWDOIN: Did you ever feel that you were way out on a limb with some of the decisions?

22 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

ROSE: I felt comfortable with the decisions we were making. Having an anchor is really important. Why are you doing what you’re doing? What are you aspiring to? We were anchored on two things. One was the health and safety of the community. And the second was delivering the best Bowdoin education we could.

Those kept us focused. So, with those in mind, and given the uncertainties and the risks and so forth, I was comfortable.

BOWDOIN: How did the board react when you decided the College should move to remote learning?

ROSE: They gave me full support. I’m certain that individual trustees didn’t agree with every decision I made along the way because they’re human beings with different views, but they never flagged in supporting what I was doing or in giving me the latitude to make the decisions I needed to make. Part of the bargain was that I tried to keep them as informed as I could along the way.

Mostly they would question why this way and not that way and so forth. In those moments I’m sure there were times when I thought that was irritating because I was trying to juggle forty-three things. But it was perfectly fair, perfectly appropriate, and the job that they should do, which is to ask questions and make sure I’m thinking about things in the right way and then ultimately support the president. So, they were great.

And they were also a great resource to me. There was a lot of intelligence, insight, and data-gathering that came from the board that was really helpful. That’s equally true of our faculty and staff across the College—remarkable people and truly outstanding at what they do. And, just to say it, the senior staff at Bowdoin is the best group of leaders I’ve worked with, and I’ve worked with some really good ones.

BOWDOIN: Did the College succeed on the second anchor—delivering a great Bowdoin education?

ROSE: We did. Our faculty—and the staff who work with them, particularly in IT [information technology]—did an amazing job. It doesn’t mean it was the same education students would

have gotten, but it was a great Bowdoin education and it pushed them forward. Now, they didn’t have the same set of experiences that they would have otherwise had. It was brutal being in your mom’s basement or whatever version of that they were doing. And so, it had a lot of costs.

But the ability of students to come together in a class to work the knowledge and the insights and the material and achieve, that’s very real. And the feedback we got on the BCQs [Bowdoin Course Questionnaires] from students at the end of each of the semesters was very strong. The two semesters where we had students doing virtual stuff—very strong. It blew me away, actually. It wouldn’t have surprised me if we had just gotten trashed, like “Thank you for trying, but this was a horrible experience.” There was none of that.

BOWDOIN: It’s not unique to Bowdoin, but the Class of 2020, and in particular the Class of 2021, had the rug pulled out from under them by COVID. They had worked so hard to get here but were never able to have a full Bowdoin experience. Do you worry about those classes disconnecting from the College?

ROSE: A little bit. And that would be completely natural. Now, in some ways you could argue maybe they’ll bond more over time. But their experience was different. It was less fun by a long shot. Scary. Uncertain. They didn’t spend nearly as much time on campus as they wanted to or expected to. So, yeah. I think we’ll have to work harder with those classes to make sure they feel really connected to the College. That said, we were able to hold Commencement exercises for both classes—the Class of 2021 in May as usual, on what was a cool rainy day,

and the Class of 2020 later that summer on a hot afternoon—and the joy and pride were amazing and palpable at both. They are great and historic Bowdoin classes.

BOWDOIN: What did you miss the most at Bowdoin during COVID?

ROSE: Oh, being in community with the students, for sure. Just being able to talk to students in a casual way or have lunch or whatever. And attend events that students created, whether it’s the art show or music or theater or sports. All of that. It all went silent. There were some creative ways to do some of it. But not most of it.

BOWDOIN: Any bright spots that came out of the pandemic?

ROSE: For one, we recognized you can get your work done from a lot of places. The whole flexible work thing has kicked in in a way that nobody anticipated. There’s the phone, there’s the meeting in person, there’s Teams, Zoom. They each have different things, but they’re all a powerful part of the toolkit, both internally and externally.

And our faculty discovered that there are some powerful lessons about how to incorporate technology into the way they teach. Many of them were just amazing in how they figured out how to adapt. I don’t think we’re ever going back on that. And that’s good.

BOWDOIN: So, COVID advanced the use of technology in the academy?

ROSE: Pushed it ahead in a way that would have taken far longer. That’s great, and I think we

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 23

“You’re not going to stumble on ‘the answer.’ And there is no perfect or optimal answer. There’s just the best path you can take at that moment.”

really have to embrace it, because if we’re going to ever get college costs down, we have to figure out how to get scale into what we do. I don’t know if technology is the only way, but it may be the only way. And if it’s not, it’s one of a handful of ways to scale a place like ours. Otherwise, we’re going to be charging $100,000 and more a year in the not-too-distant future.

BOWDOIN: Let’s talk about those costs. During your presidency, the number of students on financial aid has expanded. The College has increased its aid per student, expanded needblind admission to international students, and is working with ATI [the American Talent Initiative] to increase the number of low-income students. We recently replaced summer work obligations with additional grants

reasonable growth, not like the last twenty-five years, but something more historically normal, and we continue to get support from our alumni and parents, then yes, it’s sustainable. Not only can we do it—we should do it. We should do it because I think we have an obligation, a societal obligation that’s core to our mission, but also because we need socioeconomic diversity as part of the educational experience.

BOWDOIN: One of the constants of your presidency, beginning with your inauguration address in 2015, has been the need for open discourse, and your charge to every class of first-year students that they embrace what you call “intellectual fearlessness.” Discourse is important, of course, especially these days, but why has that been such a big deal for you?

driven by the real concern on the part of a large swath of people that their rights to power and privilege and resource were being deeply threatened by those who are different. That’s not something we’ve had to deal with in a long time. Then COVID came along.

That was a whole huge set of issues for any community to have to come to terms with, particularly a college community. And it created divisions within our various constituencies— faculty, staff, students, alumni, parents—that were true before, but had become even more unreconcilable. One of the things I came to terms with is that whatever decision you were going to make, it was impossible to find a place where everyone would agree. That actually became very clear to me at the end of my first year. So I had to be comfortable with the decision and learned to anticipate heat from every direction.

BOWDOIN: Some of that heat came after you spoke out on behalf of the College. Seems like a no-win proposition. You’ve got those who criticize the president for not speaking out enough on tougher controversial issues or after some tragic or alarming event. And then you’ve got people who firmly believe that it isn’t your job to weigh in on these topics. How have you navigated those competing views?

ROSE: It’s very much driven by values, at least for me. Are the issues I’m speaking about issues that are consistent with the values of the College and do they in some way matter significantly in what the College stands for, or do they have some direct impact on part of our community?

for low-income students and launched the Digital Excellence Commitment to provide equitable technology to all students. Meanwhile, the THRIVE program was established to support low-income and first-generation college students with their transition to college, and the number of first-gen students is up by 115 percent since you became president. All great but all expensive. Is this sustainable?

ROSE: It depends. If the markets have serial years of negative returns, then it will get trickier. But assuming that we have some stability and

ROSE: I’m a true believer in the notion that the critical mission of a great college or university is being a place where we really engage with ideas, all kinds of ideas. But in particular, ideas with which we disagree or don’t understand.

BOWDOIN: It didn’t help that partisan division in society seemed to explode early in your presidency. What did you make of that, and how did it impact the College and your job?

ROSE: We found ourselves as a society having to confront this beast of hate and division

You are seen as the leader of that community. And as the leader and someone who speaks not just for the community but to them, you have a responsibility to voice the values of the College at very difficult and challenging moments. There are always going to be questions about when you do it and when you don’t, and there’s no right answer to that. You do the best you can in figuring it out.

I think, to a large extent, we’ve gotten it mostly right, but not all the time. I can think of a couple examples of that—with the Tree of Life [shooting]. I didn’t name anti-Semitism,

24 BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 | CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU

“It wouldn’t have surprised me if we had just gotten trashed, like ‘Thank you for trying, but this was a horrible experience.’ There was none of that.”

specifically. I should have done that. In my comments on the George Floyd murder, I was not fine-grained enough in how I described the police. So you learn as you go along.

Then there’s the bigger question of when you speak up on issues of values. The one that always comes to mind for me is voting rights and the work that [former American Express CEO and chairman] Ken Chenault (Class of 1973, H’96) and [former Merck CEO] Ken Frazier did around the law that was passed in Georgia.

I wrote about that for two reasons. I felt that very little is more fundamental to democracy than the ability to vote. And we’re a quintessentially American institution that supports, defends, and teaches about democracy. We ought to stand up for that.

We also had a significant number of community members—Black members of our community, not just Ken [Chenault]—who were signatories to the [March 31, 2021] letter [to corporate America urging opposition to the voting legislation in Georgia]. And I thought, this is something that is really us, and we’ve got a valued group of our people [who are involved], let’s get behind them. That view wasn’t shared by everybody in our community, and I understand that.

BOWDOIN: But how do you set aside what might be a personal view and take on the voice of Bowdoin College?

ROSE: I agree that you have to set aside your personal views. But actually, you shouldn’t be in this job if your values don’t align with the values of the College. You can’t have a job like this if your own values are not tightly aligned.

BOWDOIN: Bowdoin hasn’t seen the kind of incidents over speech or “cancel culture” that have taken place at some of our peers. Is that just luck, or is the message about “intellectual fearlessness” getting through?

ROSE: I think we are lucky, and I’ll take that every day and twice on Sundays. But I think it’s more than that. There are a couple of things going on. First, I do think, interestingly, that the message is getting through. It has become

an idea that people talk about. Sometimes they joke about the phrase “intellectual fearlessness,” and that means the idea is being discussed and is resonating. That’s a gigantic win. I could never have imagined that.

Second, the work we do here has also been really good. It’s the work that goes on in student affairs. It’s the work our student groups are doing—Republicans, Democrats, the Eisenhower Forum, and others. And it’s faculty bringing folks to campus for thoughtful engagement.

But it’s a difficult issue here, as it is all over the country, and there are no guarantees that things won’t boil over somewhere. I’ve invited conservative speakers to campus and certainly had pushback. That’s why we need to stay on it. I’ve been clear about that, and we’ve worked it in a whole bunch of different ways to good effect, but we’ve still got a lot of work to do.

BOWDOIN: Let’s talk about another big part of your presidency—the efforts at Bowdoin around diversity, equity, and inclusion. You’ve worked on diversity in the business world and you earned a master’s degree and doctorate in sociology studying issues of race in America. But even with those credentials, someone might ask what a person of your background could possibly know about any of this or add to it.

ROSE: I guess I would say a couple things. The power structures in this country are dominated by older white men. So an older white man who understands the issues, both from a practical and intellectual perspective, has the opportunity to move the needle and to call out and call upon peers in a way that might be seen or experienced differently if done by a person of color. And I think there’s a unique ability and an obligation for those of us who are white, straight, older men to do this work.

Now, a critical necessity is that we don’t confuse that with understanding the lived experience. We don’t.

BOWDOIN: What do you hope the College can achieve with this work?

ROSE: That we can create for everyone a sense of belonging. Instead of this idea that you’re

being invited into somebody else’s house, it’s that this is our collective house, and we have to adjust that house to account for everybody— their backgrounds and their identities and their experiences.

We’re also trying to provide equity of opportunity—to have a great Bowdoin experience, whether you’re a student or an employee. It isn’t to provide an equality of outcome, that’s another trope that’s out there. But rather to have the equity of opportunity, to be able to participate in a way that gives you the opportunity to have as great an outcome as the person sitting next to you.

BOWDOIN: Of course, building a more inclusive community can be slow, difficult, and sometimes discouraging work. How can others stay optimistic and motivated to keep at it?

ROSE: First of all, I think there’s been enormous progress in this country and at Bowdoin over whatever measure of time you want. But let’s just take fifty years as one mark. For women, those of color, those in the LGBTQ+ community, among others, in both the numbers and in the experience, the influence, the engagement, and so forth, it’s better. It doesn’t mean we’re there because we’re not. But is it better? Yes.

We’re in a period of incredible tension and divisiveness in our country. And many people are unwilling to give anybody else grace or extend the notion of gratitude or separate intent from whatever actions are being taken. They assume the intent is either malicious or self-serving. Some of that’s true. But in many ways, good people are trying to get this work done, but they find themselves being challenged and denigrated from many sides, and that makes it hard. It also puts the work at risk—stopping it until the next tragic catalyst comes along. We have to be committed to pushing this work forward in a sustained way.

BOWDOIN: You recently asked the faculty to consider credit-bearing courses for low-income and first-generation students in so-called skillbuilding areas. Is that because a liberal arts education isn’t preparing students as well as it once did for what comes next?

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE WINTER 2023 CLASSNEWS@BOWDOIN.EDU 25

ROSE: No. We require students to have thirty-two credits to graduate. Let’s say thirty of them are for whatever it is you want to do that may have no specific relationship to a job. Let’s say you want to go into business and you also want to be a religion major. Now, majoring in religion and thirty classes that form the core of our liberal arts education are incredibly powerful tools for success in business or anything else. And we talk about them all the time: critical thinking, the ability to write, to communicate, to reason well, to collaborate, to be “intellectually fearless”— those are powerful. But what we know about the way employers are making hiring decisions, the competition that our graduates will face from their peers who are doing those jobs and the expectations of those employers mean that students must have a certain core set of skills and tools for the workplace in order to land the jobs and do well in those jobs.

And so—and I’m making this example up— using two of those courses over the four years here to give our students those workplace tools doesn’t dilute the idea or power of a liberal arts education. It recognizes that we have to find a way to get those tools and those skills into the hands of our students. And if we leave it outside of the curriculum as extra work, as we do now, it seriously disadvantages our first-gen and low-income students, who already have to deal with enough extra stuff.

BOWDOIN: Speaking of jobs, one of your responsibilities as president is to raise money for the College. Do you enjoy that?

ROSE: I do enjoy it. You’re not just walking in and grabbing somebody by the scruff of the neck off the street and saying, “Give me some money!” You’re moving along a conversation about how to help the College, and in a way that matters to somebody. They’re great conversations. It doesn’t mean that it’s the right moment in life for somebody or that they can do this or that. Not every conversation results in either the thing that we’re asking people to do—which is fine, because sometimes it leads to another conversation—or the right moment in life for somebody to provide that kind of a gift. But sometimes you get surprised on the upside

as well. I’ve had a few people say, “It’s time to ask me for something.”

BOWDOIN: The ongoing From Here campaign is built on three core promises: that family income will never be a barrier to attending the College, that Bowdoin will continue to provide an enduring and transformative liberal arts education, and that we will give students the opportunities and resources to land their first great job. That last one seems like it’s long been assumed or taken for granted. You would think that if you graduate from a place like Bowdoin, you’ll get a great first job. Why so explicit on that?

ROSE: Two things have happened. The market for jobs hasn’t necessarily gotten tougher— there are moments when there are more open jobs and other moments when fewer jobs are open, depending on the economy. But over the last decade or more, the requirements for entry into those jobs have changed, and not in an insignificant way.

The second is that we have more and more students who come from family backgrounds where an understanding of the variety of employment opportunities out there and the path to those jobs are less well understood than before.

So it requires a very sophisticated career development effort, and very explicit work to be able to ensure that you can take all the great skills of a liberal arts education and the credential that comes from being at a place like Bowdoin and be able to translate that into a job.

I have to say that this is another area where we’ve made enormous progress. Where we are with that effort today is night and day from where we were before. That doesn’t mean we don’t have more work to do—because we do.

BOWDOIN: Like what?

ROSE: How we engage with employers, how we deal with the curricular skill-building issues that we’ve talked about, how we take the incredible enthusiasm and desire of our alumni to work with our students and maximize opportunities for our students. We do really strong work now, and really well-organized work, around all this.

BOWDOIN: Returning to your earlier comment about raising money for the College, just before you started as president, Dave Roux [trustee emeritus, P’14] told you that he and Barb Roux wanted to make a gift of $10 million to the College to support a priority of yours, and you suggested building a new home for environmental studies.

ROSE: Yeah. It’s a beautiful building in a prominent location with teaching spaces designed to be incredibly flexible. It’s also a physical manifestation of our commitment to environmental studies. It’s a huge winner because it makes a substantial statement to our community, to those interested in the College, and to the broader world that this is something really important to us.

BOWDOIN: The Schiller Coastal Studies Center came next.