GO INSIDE OSU’S WRESTLING AND BASKETBALL COACHING SEARCHES

GO INSIDE OSU’S WRESTLING AND BASKETBALL COACHING SEARCHES

BY K E VI N K LI NT WO R TH

The beginning of a new school year is a time to look ahead with anticipation, but one event coming up this semester gives us the opportunity to also look back.

In December, former Cowboy receiver Justin Blackmon will be inducted into the National Football Foundation College Football Hall of Fame. The awards banquet is Dec. 10 in Las Vegas. Membership in the NFF Hall of Fame is the pinnacle for a college football player. And Blackmon’s swift entry into the exclusive club further illustrates just how much of a phenomenon the Plainview High School product was for Oklahoma State.

This year’s Hall of Fame class includes the likes of receivers Larry Fitzgerald and Randy Moss, quarterbacks Alex Smith and Tim Couch, running back Toby Gerhart and defensive linemen Julius Peppers and Dewey Selmon . Overall, the class, including coaches, is 21 strong.

And the youngest inductee is Justin Blackmon.

Already a member of the OSU Athletics Hall of Honor, Blackmon’s career included just two seasons as a starter, 2010 and 2011 (his sophomore and junior years of eligibility). But those two seasons were good enough to solidify him as college football royalty. In 26 games over those two campaigns, Blackmon caught 38 touchdown passes. He led the nation in that category as a sophomore and was second as a junior. He caught 233 passes during that time, and he averaged 148 receiving yards per game in 2010 and 117 per game in 2011. His 1,782 receiving yards in 2010 set an NCAA record for sophomores.

Blackmon’s statistical accomplishments are endless. But as much as the statistics tell the story, they also can’t tell the entire story. Blackmon’s biggest moments came in the biggest games, making his career truly one of the best in OSU history.

With just a couple of games as a starter under his belt in 2010, Blackmon and quarterback Brandon Weeden teamed up for a 45-yard touchdown midway through the fourth quarter for the game-deciding points in a tight home win over Troy.

At Texas Tech, the Cowboys were trying to end one of those “OSU hasn’t won there since” streaks when Blackmon got loose for a 62-yard touchdown to break the back of the Raiders while giving a hint of what was to come, including more wins in Lubbock.

In one of those “OSU should never beat this team” games, Blackmon’s 67-yard TD reception on a pass from Weeden gave OSU complete control at Texas and launched a new era of fun times for the Cowboys in Austin.

He was the MVP of the 2010 Valero Alamo Bowl against Arizona when he had nine catches for 117 yards with two scores to clinch the first 11-win season in Oklahoma State history.

The following year Blackmon was target No. 1 for opposing defenses. It was the right idea, but not one opponent was able to execute it. When the dust had settled, Blackmon had his second consecutive Biletniko Award as America’s best receiver. He was once again a unanimous All-America selection . And he was also a Big 12 champion as Blackmon, Weeden, running back Joseph Randle and an opportunistic defense led the Cowboys to the league title and a final ranking of No. 3 in the Associated Press and BCS polls, the highest in school history.

The first marquee game of that 2011 season saw Blackmon grab 11 passes for 121 yards and a touchdown in OSU’s monster road comeback at No. 8 Texas A&M. He even scored two points for the Aggies — on purpose.

In a terribly tense back-and-forth a air with Kansas State, Blackmon had a

gigantic score on a 54-yard TD reception in the final five minutes of OSU’s 52-45 win over the Wildcats. It was the night that an earthquake famously rocked the stadium just minutes after the final whistle.

In the Fiesta Bowl victory over No. 4 Stanford, Blackmon was once again the game MVP. He didn’t get going in the desert until the Cowboys had spotted the Cardinal a 14-point lead. Consecutive scoring plays by Blackmon, covering 43 and 67 yards, signaled the arrival of OSU and the beginning of the end for the Cardinal.

On Oklahoma State’s final scoring drive of regulation, Weeden hit Blackmon for 21 yards and a first down on a fourth-andmust-have-or-game-over conversion.

The final statistics in OSU’s 41-38 overtime victory saw Blackmon with nine catches for 186 yards and a Fiesta Bowl record three touchdowns as an exclamation point on the first 12-win season in school history.

Blackmon is the eighth OSU player inducted in the College Football Hall of Fame. He joins coaches Lynn “Pappy” Waldorf and Jimmy Johnson, and former student-athletes Bob Fenimore, Terry Miller, Leslie O’Neal, Barry Sanders and Thurman Thomas. Each man not only earned individual accolades, but they helped lead their teams to historic accomplishments.

Waldorf coached the A&M Aggies to a 34-10-7 record. He was 3-0-2 in Bedlam and is the last coach to lead the University of California to a Rose Bowl.

Jimmy Johnson’s rebuild of the program would have included three bowl games in five years if not for lingering NCAA sanctions he inherited in year one. Not only did he flip the script in Stillwater,

column.

Heisman Trophy runner-up Terry Miller helped lead the Cowboys to the 1976 Big Eight title. He and his teammates lifted OSU Football to its highwater mark between the Fenimore era and Pat Jones’ string of 10-win teams in the 1980s.

Thurman Thomas played on the first two of Jones’ 10-win teams. At Tailback U., his 5,001-career rushing yards still top the charts.

Barry Sanders remains as OSU’s only Heisman Trophy winner after his historic 1988 season. He also played on a pair of 10-win teams. Sanders and Thomas are also members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame for the rare Hall of Fame double.

Leslie O’Neal, who will join OSU’s Ring of Honor in 2024, anchored perhaps the best defenses in school history, allowing just 34 touchdowns over two seasons. He still holds the OSU record for career quarterback sacks with 34, a full 40 seasons after his last game as a Poke.

Justin Blackmon is up next in the college hall, but he won’t be the last . At some point in the not-too-distant future, the group of eight Cowboys immortalized by the National Football Foundation will be joined by another OSU alum who made program-defining moments and impacted the direction and success of Cowboy Football. Someone who defined their era. Somone who became a household name in college football circles.

Someone like Justin Blackmon.

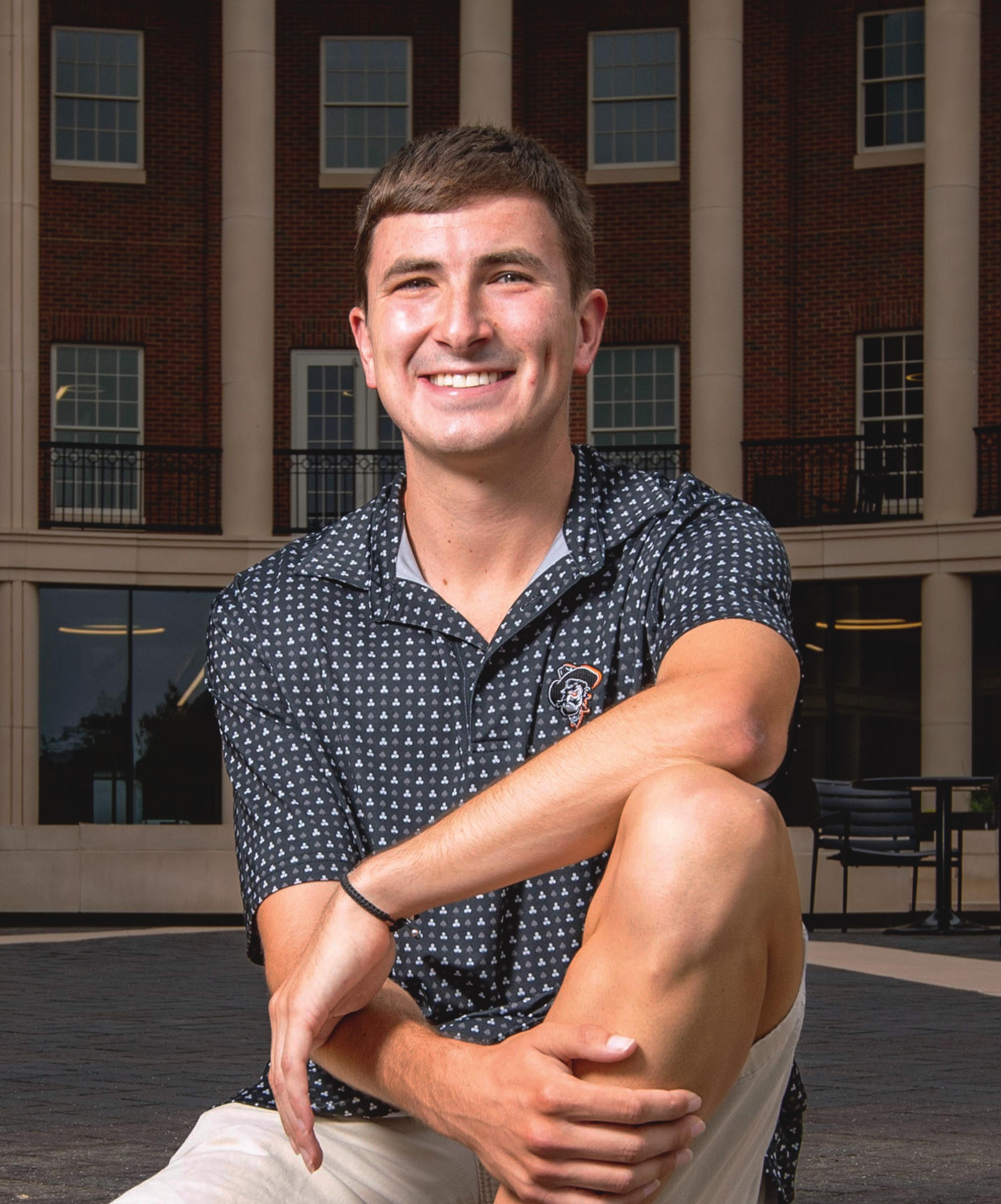

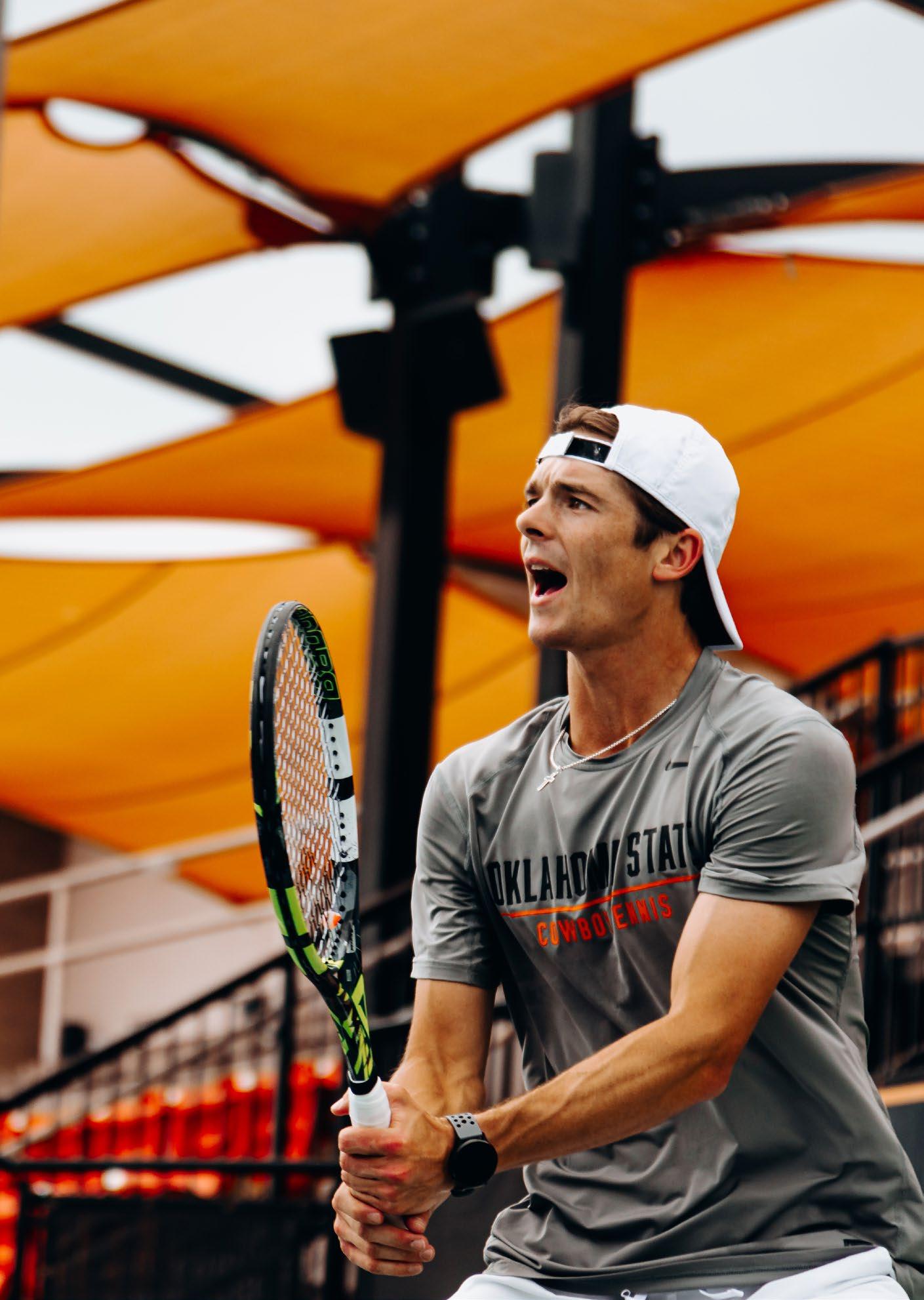

RYAN SCHOPPE BECOMES A LEADER FOR COWBOY CROSS COUNTRY AND TRACK

CHAD WEIBERG’S TWIN COACHING SEARCHES LEAD TO STEVE LUTZ AND DAVID TAYLOR

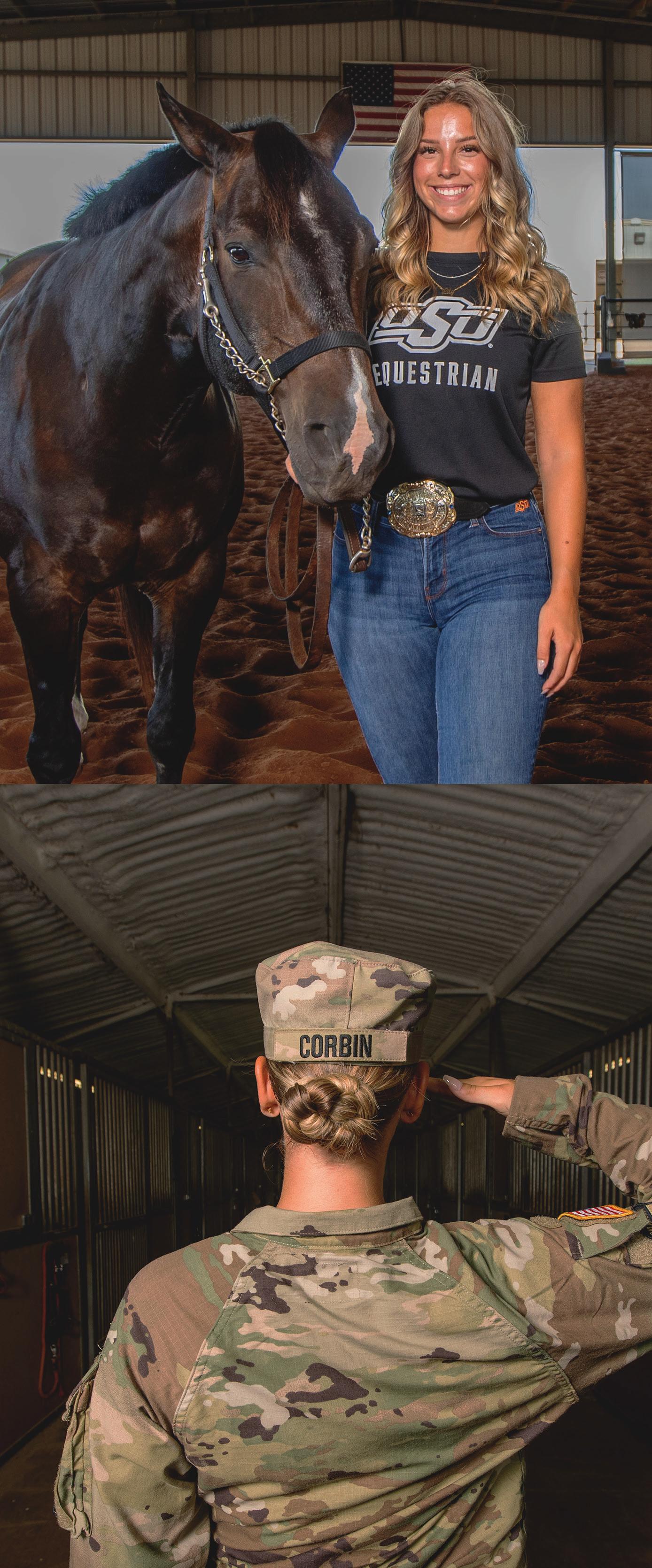

LILY CORBIN SPLITS HER DUTIES BETWEEN EQUESTRIAN AND ROTC 30

HOW MAKING THE RIGHT CHOICE LED STEVE LUTZ TO STILLWATER 40

CALVIN AND LINDA ANTHONY’S PRESCRIPTION FOR A WONDERFUL LIFE 50

THE “MAGIC MAN” DAVID TAYLOR TAKES OVER COWBOY WRESTLING

POSSE Magazine Sta

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF / SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR KEVIN KLINTWORTH

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR JESSE MARTIN

ART DIRECTOR / DESIGNER JORDAN SMITH

PHOTOGRAPHER / PRODUCTION ASSISTANT BRUCE WATERFIELD

ASSISTANT EDITOR CLAY BILLMAN

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS CLAY BILLMAN, LANDRY BLEDSOE, LEAH BWOLF, JAIDEN DAUGHTY, MASON HARBOUR, JEROD HILL, GARY LAWSON, DANNY PHILLIPS, TONY ROTUNDO, PHIL SHOCKLEY, ADDISON SKAGGS

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS CLAY BILLMAN, JENNI CARLSON, HALLIE HART, KEVIN KLINTWORTH

ASSOCIATE AD / ANNUAL GIVING ELLEN AYRES

PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR CLAY BILLMAN

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT BRAKSTON BROCK

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ANNUAL GIVING STETSON DEHAAS

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT MATT GRANTHAM

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT DANIEL HEFLIN

SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD / EXTERNAL AFFAIRS JESSE MARTIN

SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT LARRY REECE

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT SHAWN TAYLOR

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ANNUAL GIVING ADDISON UFKES

ATHLETICS PROJECT MANAGER JEANA WALLER

102 ATHLETICS CENTER STILLWATER, OK 74078-5070

405.744.7301 P 405.744.9084 F OKSTATE.COM/POSSE POSSE@OKSTATE.EDU

ADVERTISING 405.744.7301

EDITORIAL 405.744.1706

At Oklahoma State University, compliance with NCAA, Big 12 and institutional rules is of the utmost importance. As a supporter of OSU, please remember that maintaining the integrity of the University and the Athletic Department is your fi rst responsibility. As a donor, and therefore booster of OSU, NCAA rules apply to you. If you have any questions, feel free to call the OSU O ce of Athletic Compliance at 405-744-7862 Additional information can also be found by clicking on the Compliance tab of the Athletic Department web-site at okstate.com

Remember to always “Ask Before You Act.”

Respectfully,

BEN DYSON

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR FOR COMPLIANCE

Football fans will notice some significant upgrades to gameday comfort and convenience at Boone Pickens Stadium this fall. Focusing on the south side seating areas, the final phase of a multi-year, $55 million upgrade includes AirFlow mesh chairbacks in midfield sections. These state-of-the-art seats are designed to stay cooler in the Oklahoma sun and dry quickly after rains. The remaining south stands feature comfortable, contoured bleachers to match the west endzone and north stands (completed prior to the 2023 season). Additional aisles with handrails have been added for easier ingress and egress. New wheelchair and companion seating areas are also included. Underneath the stands, bright LED lights, video screens and two grab-and-go concession areas will liven up the plaza level.

New defensive line coach Paul Randolph instructs freshman defensive end Armstrong Nnodim (94) and his teammates during drills in fall camp. With 26 years of collegiate experience under his belt, the veteran coach arrived in Stillwater in January after most recently serving as Indiana's d-line mentor. Despite losing several key contributors to graduation, the position group has reloaded with a combination of experienced returning players and talented newcomers.

RYAN SCHOPPE GROWS INTO “ROCK SOLID” LEADER FOR COWBOYS

Ryan Schoppe inherited either a blessing or a curse at the NCAA Indoor Track & Field Championships in March. Only he could determine which it was.

With a swift baton exchange from Mehdi Yanouri, Schoppe carried a narrow lead into the anchor leg of the men’s DMR. From Oklahoma State coach Dave Smith’s perspective, Schoppe faced the most daunting task of anyone running those final eight laps in Boston.

The easygoing distance runner from LaPorte, Texas, had no one to pursue, which meant everyone was pursuing him His coach compared the precarious situation to swimming in the ocean with unseen sharks.

But Smith, often a bundle of nerves and energy during track meets, didn’t have to fret about the feeding frenzy. The Cowboys knew what to expect from Schoppe, their anchor man.

“He is a competitor,” Smith said. “He does not want to let anybody down. He wants to be there for his teammates. His whole facial expression and his posture, everything changes. You can just see this heroic look come across him when he gets that baton.”

Entering his fifth year at OSU, Schoppe has proven himself through versatility. During the 2023 outdoor season,

he clocked a 13:37.06 in the 5,000-meter race at the Bryan Clay Invitational, setting a personal best to rank seventh in the Cowboy record books. One year earlier at the same meet, he shattered German Fernandez’s program record in the 1,500, finishing in 3:37.43. With a collection of All-Big 12 honors, Schoppe is poised to also play a major role this fall for a Cowboy cross country team defending a national title.

Amid his many talents, the DMR stands out as Schoppe’s tour de force, the event that elevates him from a solid athlete to an awe-inspiring champion. Schoppe, an aspiring coach, keeps the Cowboys grounded as a veteran leader with youthful positivity, someone who takes care of business in the classroom but doesn’t let thoughts bog him down on the track.

It’s only fitting that he thrives as OSU’s metaphorical and literal anchor.

“It was just up to me to claim that position my sophomore year, and then I just kept it ever since,” Schoppe said. “I love that role, and I don’t want to lose it. I feel comfortable in it.”

With his outstanding performances on the biggest stage, Schoppe has ensured the spot belongs to him. He’s a back-to-back national champion in the DMR, including this year’s race in Boston, when he fended o Georgetown runner Camden Gilmore’s bell-lap surge for an exhilarating finish.

“When I’m free and not thinking about it, that’s when I’m at my best.”

— RYAN SCHOPPE

Schoppe runs with a paradoxically calm sense of urgency. He understands the immensely high stakes but doesn’t let them rattle him. Schoppe knows in a matter of minutes, he could secure gold for his teammates or destroy the lead they cohesively worked to build.

He simply refuses to let the latter happen.

Dave Smith realized he had no choice.

As he assembled his DMR team for the 2022 indoor season, he knew the Cowboys were low on depth. With the rest of the team set, they had no anchor. A bit reluctantly, Smith turned to a lanky sophomore named Ryan Schoppe, who hadn’t developed the strength or speed of his seasoned teammates.

“He’s young,” Smith recalled. “He’s inexperienced. He’s not the best guy we’ve got, but this is the way it’s gonna have to go.”

Despite those doubts, Smith saw tremendous potential. The coach had recruited Schoppe because of his achievements at La Porte High School, where he twice won state in the 3,200

and, during cross country season, logged a 5K time of 14:14.02 for a Texas high school record. Still, could Smith count on a sophomore to handle the longest leg of the DMR, a 1,600-meter push?

He was about to find out.

At nationals, the Cowboys struggled through the DMR, so Schoppe had slim chances of winning by the time he secured the baton. Although the sophomore couldn’t create a miracle, he made a valiant burst toward the front, bringing OSU back to finish fifth. Briefly, he held the lead, showing Smith a thrilling vision of his team’s future.

The Cowboys had identified their anchor.

“I don’t know if Ryan’s the best guy in the NCAA,” Smith said. “He probably isn’t, but when you get a baton in his hand, when someone’s relying on him, when he’s got other people that are depending on him — he is phenomenal. He finds something deep down inside him where he can be really, really good.”

Although Schoppe appeared at ease in the race, he had never competed in the DMR until that year at OSU. The event wasn’t part of Texas high school meets, but in college, it served as an outlet for the competitiveness that had driven him since childhood.

As an active kid in the Lone Star State, Schoppe dabbled in a variety of sports: basketball, tennis, swimming and baseball.

With a knack for memorizing plays, he also tried his hand at quarterback. Schoppe sheepishly grinned at the memory.

“I shouldn’t have done football,” Schoppe said. “As a little scrawny kid, I was never built to be a football player.”

Instead of starring under the Friday night lights, Schoppe gravitated toward the oval surrounding the gridiron. His unmistakable talent caught the attention of Smith, who took a recruiting visit to LaPorte before Schoppe’s senior year of high school.

Quickly, Schoppe endeared himself to Smith.

“Having a guy like that around is just a benefit to everybody,” Smith said. “I think of him as like a puppy that when you walk up, and he starts wagging his tail, he pees on the floor because he’s so excited to see you. He’s just this very happy-go-lucky, charming, positive kid.”

Schoppe carries himself with boundless enthusiasm, but it doesn’t mean he’s nervous. The Texan has the free-spirited vibes of a California surfer dude, content with venturing o the beaten path and finding solace in nature. For Schoppe, who also enjoys golf and pickleball, running on a quiet dirt road is almost a form of meditation.

“When I’m free and not thinking about it, that’s when I’m at my best,” Schoppe said.

Schoppe realized he could channel that clear mindset in Stillwater, where the college-town setting o ers a relaxed contrast to the hustle-bustle of the Houston suburb where he grew up. Add in Smith’s leadership, and OSU o ered the ideal environment for Schoppe to build his career in cross country and track.

After nearly five years in Stillwater, Schoppe continues to radiate the “puppy dog” personality Smith noticed on the initial recruiting trip, but the distance runner has also shown his serious side on several occasions.

Is his laid-back persona a clever disguise for his fierce competitiveness, or is the heroic competitor an alter ego that surfaces only when he’s racing toward a finish line? Perhaps the true Schoppe is a combination of both, fueling success on and o the track.

Schoppe maintained his upright posture as Camden Gilmore rapidly gained on him.

The OSU distance runner’s legs kept churning. His head never swiveled. Catching a glimpse on the big screen of the approaching Georgetown senior, Schoppe simply bolted

toward the finish line, clasping the baton in his right hand as if it were the source of a superpower.

A last-minute scare only provided more motivation.

“I don’t like giving people a free opportunity, slowing it down and making it a tactical race,” Schoppe said. “I want people to work for it. I was pretty confident when I got the stick in the lead, and I knew that we had a really good shot at winning if I just ran my race.”

With a time of 9:25.24, the Cowboys secured their second straight national title in the DMR, repeating as relay champions for the first time since 1965 and ’66. Brian Musau gave OSU a flying start with a time of 2:54.86 in the 1,200-meter leg. DJ McArthur kept up the momentum, covering 400 meters in 45.60. Yanouri followed with a time of 1:49.20 in the 800, propelling the Cowboys to a lead Schoppe wouldn’t surrender.

OSU’s depth had increased since Schoppe’s sophomore year, so Smith wavered in his DMR order ahead of the race, tinkering with combinations as if he were solving a logic puzzle in math class.

He didn’t have to wonder where Schoppe would fit.

After his breakout in 2022, Schoppe won his first NCAA title in the DMR as a junior, helping the Cowboys surge to a three-second victory.

In February of 2023, OSU made world history. Fouad Messaoudi, Hafez Mahadi, McArthur and Schoppe won the DMR at the Arkansas Qualifier in 9:16.40, shattering Oregon’s previous mark by three seconds to set an unofficial indoor world record. Schoppe blazed through the anchor leg in 3:52.84 to finish the job.

He carried that momentum into this past indoor season, securing OSU’s fourth straight Big 12 title in the DMR. Musau, Ben Currence, Laban Kipkemboi and Schoppe finished in 9:29.41 before Schoppe scorched through the mile in 4:02.73 to add an individual conference title.

Given this recent history, Smith had no doubt Schoppe would handle the anchor leg at nationals.

“He’s just rock solid in those situations,” Smith said.

“Rock solid” could also describe Schoppe in the classroom. In March of 2022, he won the Elite 90, the NCAA award given to an individual who has excelled in academics and advanced to the national championship level in athletics.

“It was pretty special,” Schoppe said. “I try to balance it perfectly between free time, athletics and academics. It’s something I’ve learned, how to budget my time over the years.”

A sports management and marketing student in OSU’s Spears School of Business, Schoppe wants to stay close to sports after graduation. He aspires to run professionally, and he has also considered marketing for an athletic company.

Smith provides inspiration for Schoppe’s other dream: being a coach.

This past cross country season, as the Cowboys secured their first national title since 2012, Schoppe served as a coach-like motivator within the team. With Smith’s guidance, he made the mature decision to redshirt, recognizing OSU’s depth and choosing to preserve his eligibility.

That didn’t mean Schoppe could sit back and relax. In the hours leading up to any race, Smith could have burned the redshirt, though it didn’t end up happening.

“His role was, ‘Be ready to go,’ and he was, up until that final deadline at 20 minutes to go,” Smith said.

With enough eligibility for two more cross country seasons, Schoppe must continue to stay ready and build confidence. Smith said the only time he has seen Schoppe’s self-belief waver is when it comes to cross country. Schoppe will say the sport isn’t his forte, but his coach disputes that opinion. The distance runner just needs the same level of determination he has when he seizes the baton and closes out the DMR for his teammates.

“Maybe we should just make him run with a baton,” Smith joked.

He has a point. The baton turns the Cowboys’ beloved goo all into a heroic figure, a focused leader who will not accept failure.

With a reliable anchor, Smith doesn’t tell Schoppe’s DMR teammates they need to win. Instead, this is their motivational line: “You just have to keep Ryan Schoppe close.”

Schoppe can surge from behind, or if the Cowboys give him the lead, he won’t sweat the pressure.

An early advantage might doom some runners. Schoppe chooses to treat it as a blessing.

Senior Jilyen Poullard celebrates with Oklahoma State softball head coach Kenny Gajewski as she rounds third base on a home run trot. Poullard's power helped No. 4 OSU knock o the second-ranked Sooners 6-2 in Norman on Saturday, May 4. The victory clinched the final Big 12 Bedlam series for the Cowgirls, who took two out of three games at the newly-minted Love's Field. Poullard hit the go-ahead homer in Friday night's opener to lead the Pokes to a 6-3 victory that set the tone for the weekend.

On April 4, 2024, Oklahoma State athletic director Chad Weiberg was enjoying some quiet time in his Gallagher-Iba Arena o ce. He had recently completed the 17-day search process for a new head men’s basketball coach and was preparing for the afternoon news conference in which he would introduce Steve Lutz to the Cowboy family.

Mission accomplished. But only temporarily as it turned out.

Enter John Smith into Weiberg’s sanctuary.

On the same day that Lutz was launching his OSU career, the legendary Cowboy wrestling coach broke the news to Weiberg that Smith’s just completed 33rd season in charge of the program was his last. For the first time in more than 100 years, Cowboy Basketball and Cowboy Wrestling would change head coaches in the same school year.

And Weiberg, after a very brief pause, would once again be shopping for a head coach.

Any search for a Division I head basketball coach is high profile and heavily scrutinized on a local, state and national level. And any time Cowboy Wrestling goes looking for a head coach, every corner of the wrestling universe stops and takes notice. Worlds were colliding. OSU Athletics was about to experience the bright lights of both spotlights within days of each other.

It was on March 14th that Weiberg made the announcement that Mike Boynton would not return to lead the OSU basketball program, o cially opening Search Number One. On May 7th, David Taylor was announced as the successor to Smith, o cially closing Search Number Two.

In between, there were numerous phone calls, multiple flights, partnerships with two search firms, stacks and stacks of unsolicited feedback and input and some wise counsel.

The result was two hirings that have been virtually universally applauded

“I thought they would both be very good fits for OSU in their own ways,” Weiberg said of Lutz and Taylor. “They are obviously di erent people in di erent sports from di erent backgrounds, but they are very relatable. They have families that are important to them, and I think they are both good fits for their programs, for our university and our community.”

Lutz comes to Stillwater having already turned around programs in his two previous stops as head coach at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi and Western Kentucky. Taylor is a first-time head coach and just 34 years old. But his hiring sent shockwaves throughout the wrestling world, and by all indications, reignited the OSU fan base.

Two men with two di erent backgrounds for two di erent programs from two di erent and not-quite-butalmost synchronized searches.

“In a basketball search, there is a lot of tra c because a lot of searches are being run simultaneously,” Weiberg said. “In wrestling, everyone was watching what we did.”

Chad Weiberg is the son of a coach, and it would be fair to describe him as a coach’s athletic director. If he had had his druthers, there would not have been any searches during the spring of 2024, and certainly not two of them. Boynton was a popular campus figure and had endeared himself to the OSU community with his support of anything and everything orange. He had lots of people rooting for him and his young team, including Weiberg.

“I was hoping that we would show some signs of momentum,” Weiberg said of the Oklahoma State hoops program. “I was looking for something that indicated we were heading in the right direction, something that indicated we

should let things play out another year. But it just didn’t happen. There wasn’t just one clinching thing, but it became clear to me that we needed a fresh start.”

At the conclusion of the 12-20 season, which ended in the first round of the Big 12 Tournament, Weiberg made the move, initiating his first search of the spring.

Seventeen days later, when John Smith brought his decision into the athletic director’s o ce, Weiberg took a boxer’s approach of stick and move.

“I really just wanted to buy some time,” he said. “The NCAA championships had basically just ended, and I know there is always a lot of emotion involved when a season concludes. I thought maybe if he could just get away from it for a while, it might get his competitive juices flowing again — if he got some rest, some energy. I asked him to take a bit of time.

“And by the way, I am introducing our new basketball coach later today, and I need some time,” Weiberg laughed.

John Smith, considered by many to be the LeBron James or Tom Brady of his sport, acquiesced to the AD in the short term, but his decision had been made. The rest was a formality.

There is a public perception, or maybe misconception, about the role search firms play in the hiring process for head coaches. Those firms do not do the hiring or even the recommending of a hire, but they help with due diligence by handling the road work and paving the way for dialogue. They are a resource for potential candidates, and they help universities determine who has serious interest as opposed to those using an opening to garner a raise at their current school. And perhaps most of all, they keep athletic directors from spending time chasing down rumors, gossip and false reports.

For the men’s basketball search, Oklahoma State chose to work with Turnkey ZRG

“I’ve pretty much been around all of them at some point,” Weiberg said. “I chose this one for several reasons. Our point person, Katie Young Staudt, was in Tulsa. Her dad was a big OSU fan. She was from Enid, and she’s very familiar with basketball and our program. Her husband works for the NBA. She had great knowledge of our institution and our situation. All of those factors appealed to me for that particular search.”

In the early going of any search, phones are the instrument of choice. So Weiberg and Deputy Athletic Director Reid Sigmon (and their cell phones) made the trip to Kansas City for the early stages of the NCAA Division I Wrestling Championships. As it turned out, they stayed for just one session before relocating to Dallas for the bulk of their manhunt.

“A significant part of the search was conducted in Dallas,” Sigmon said. “It is an easy place for candidates to reach with direct flights everywhere. Coaching searches can have lots of changes and the location gave us flexibility.”

The OSU program drew plenty of attention. Along with the history of Cowboy Basketball, from Iba to Sutton to Gallagher-Iba Arena, there was also the lure and challenge of competing in the Big 12 Conference, long considered the nation’s best basketball league.

And every coach wants to work for an athletic director who can appreciate the challenges a new sta will face, someone who truly understands the inner workings of his or her sport. Weiberg is the son of a long-time basketball coach (Mick, a former OSU assistant) and the brother of another coach, Brett, who is the men’s head coach at Southwestern Oklahoma State in Weatherford. Another sibling, Jared, was one of the 10 members of the OSU basketball family who was lost on Jan. 27, 2001.

Chad Weiberg is also about to become the first OSU athletic director to sit on the prestigious NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Committee. On Selection Sunday, he will

be in Indianapolis helping seed March Madness — another bonus for a basketball coach who is shopping for just the right boss.

Despite the rumors, false media reports and insinuations to the contrary, which seem to surface in every search since the invention of electricity, Weiberg, Sigmon, and the folks at Turnkey ZRG kept the buttoned-down coach hunt running in an orderly and quiet fashion. In fact, the lack of leaks regarding the search likely led to the information vacuum being filled by those with little or no information or confirmation.

“I never felt rushed to make a decision for fear we were going to lose out on someone,” Weiberg said of the process and a timeline that saw several power conference schools looking for coaches simultaneously. “There were some really good candidates in this cycle and a lot of them wound up with really good jobs. And I think they all wound up at places that fit them.

“I think we ended up with a guy that really fits us the best,” he added, “which is one of the things I liked about Steve Lutz from the very beginning.”

“NO EXPECTATION IS TOO HIGH FOR OUR PROGRAM. WE ARE NOT INTERESTED IN TALKING ABOUT FINISHING SECOND.”

— Chad Weiberg

Lutz was born in San Antonio, grew up in Texas, played basketball at Texas Lutheran, earned an advanced degree at Incarnate Word in San Antonio and cut his coaching teeth at the likes of Stephen F. Austin and SMU, along with his assistant stints at Garden City Community College, Creighton and Purdue. His first head coaching job was at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi

“Certainly, his familiarity with the region was important,” Sigmon said. “But he is also straightforward and a hard worker. His success of three-straight NCAA Tournament trips at two di erent schools without a lot of history is impressive.”

Media, social and otherwise, began reporting that Oklahoma State had zeroed in on Lutz, although the announcement was not made o cial for several days after those reports.

“The truth is we were not finished with our process,” according to Weiberg. “The minute we visited with Steve Lutz, he was very, very high on our list, but we still had a process to finish. And by doing that, it a rmed our initial impressions of Coach Lutz. When you find someone that you think might be your person, you do not stop in the middle of the process. It’s another way of a rming your choice.”

John Smith was one of the longest tenured coaches in Oklahoma State history, along with men’s tennis coach James Wadley and Mr. Henry Iba. Despite his years of service, Smith’s departure was still a jaw dropper, and it launched a search process that took an unexpected turn.

“Our wrestling job had not been open in 33 years,” Weiberg said. “You realized when it was happening that it was historic. Oklahoma State is the capital of wrestling. I felt that we needed to turn over every rock and see where it led and trust that it gets you to the right place.”

In Weiberg’s own words, he suspected the search process would take him eventually to internal candidate and Cowboy alum Coleman Scott. “But I also knew it was Oklahoma State and there would be tremendous interest. I told Coleman I had a responsibility to run a search. I mean, this is Oklahoma State wrestling,” Weiberg said.

For the second search, Weiberg went with Bowlsby Sports Consultants, led by Kyle Bowlsby, the son of former Big 12 commissioner Bob Bowlsby.

“I’ve known the family for a long time, and they are huge wrestling people,” Weiberg said. “Bob was a wrestler and a former athletic director at Northern Iowa, Iowa and Stanford before becoming the Big 12 commissioner. Kyle has been around it his entire life. I don’t think there is anyone who understands the wrestling landscape any better. He was someone I could bounce questions o and who could run interference for us.”

During the process, certain trends became evident. The name of David Taylor continued to surface. At the same time, OSU was having conversations with multiple candidates, including some sitting head coaches.

“David was getting ready for the Olympics, and I think everyone in the world thought he would be wrestling late into the summer, so it didn’t appear the timing would work out,” Weiberg said. “Our search was basically on hold during the Olympic trials. When the competition was over, the question was how much interest he had in being a college coach and leaving Pennsylvania for Oklahoma.”

Taylor was serving as the owner and operator of the M2 Training Center in State College, Penn., while still competing on the world stage. He created the center to help wrestlers achieve their goals on and o the mat while competing at the world level. As a competitor, his résumé included an Olympic gold, three world championships and two NCAA titles at Penn State.

Phone conversations revealed that Taylor was interested, especially in a situation with a high ceiling like OSU. Soon after, a Cowboy contingent, including Weiberg,

Sigmon, sport administrator Tony Petro and wrestling donor Chad Richison, headed to State College to meet with Taylor and his family in person. Taylor had spent his entire adult life in State College, a liated with or adjacent to Penn State wrestling.

“It was clear David had given the job a lot of thought and consideration,” according to Sigmon. “He had lots of questions. Our expected two-hour interview turned into five hours. It was a great opportunity to spend time with David and his wife, Kendra, and get a look at the life they had built there.

“That was a highlight for me. But if you ask Tony or Kendra, they will probably say it was the goat that kept trying to eat my sportscoat.”

For each of the searches, Weiberg was also focused on keeping his tight circle small, but well informed.

“It was important to keep the Board of Regents and the president informed during both searches,” he said. “That goes without saying, but there are certain stakeholders as well as donors that need to be in the loop as well.”

Regent Joe Hall played a role in both searches. OSU alum Ross McKnight was a resource on the men’s basketball side, and Richison was an important member of the wrestling search process.

“I don’t know if saying they were part of the process is even a fair way of putting it,” Weiberg said. “They were part of the solution.”

There were other constituents as well.

“I met with both teams and told them that it would take a little bit of time, but I would keep them as informed as I possibly could,” he said. “I told them to come and see me at any time, and some of them did. But it’s important to keep searches confidential. You have some candidates that are putting a lot on the line when they express an interest in your job, and you don’t want to betray them or put them in bad position.”

There was also the John Smith factor for Weiberg to consider.

“I wanted to keep him informed, but also not put him in an awkward position with respect to the sta that we already had in place,” Weiberg said. When you have someone with as much expertise and experience as Coach Smith, you want to use that as much as you can. As we began to zero in on David, I let Coach know the direction I thought we were going to go. He gave me his thoughts, which were fair.”

When the dust had settled on both searches, Weiberg, Sigmon and their search partners could look back with some satisfaction, not just at the outcome, but also on the winding road to the finish line.

Oklahoma State basketball is considered a program of great historical significance. But with recent struggles and the emergence of the Big 12 Conference as the country’s best for several years running, the climb back up the hill may not be easy — as Weiberg is fully aware.

“We have had some hard times lately, and things haven’t gone the way we wanted,” he said. “But it’s not like we are trying to sell something that is unprecedented. We have Final Fours and Sweet 16s in our not-too-distant past. We have two Hall of Fame coaches. We know it’s possible here, and the coaches we talked to knew it was possible. The first step is returning to the NCAA Tournament and then going from there. That is our expectation.”

“As for wrestling, as we have said publicly, no expectation is too high for our program. We are not interested in talking about finishing second.”

Since March, the only consistency for the men’s basketball and wrestling programs has been changes. The result of the turnover, from the rosters to the coaches, might be hard to evaluate for the OSU faithful. But early indications are that they are ready to ride with the Cowboys.

“The new energy brought to the wrestling program with the hiring of Coach Taylor has already been reflected in ticket sales, even in the heat of the summer,” said OSU’s assistant athletic director of ticketing Alec Proctor. “And I like where the numbers are for men’s basketball. We are seeing renewed interest from some of our most generous supporters. Many of them are former basketball season holders who had migrated to football only. Now they are ticket shopping for both programs.”

“There is great, untapped potential for Cowboy Basketball,” Weiberg said. “We’ve seen it before. The packed GIA with electricity in the air you can cut with a knife. The epic battles with Kansas, Iowa State and others. The tournament runs. And we need to get it back to that place. Coach Lutz understands the importance of the opportunity and, together with the support of the Cowboy Family, I’m confident he can get us where we all want to be.”

The searches are now behind both the candidates and the OSU administration. Sta s have been completed, rosters have been built, and the schedules are nearly finalized. Soon Steve Lutz and David Taylor will begin their maiden voyages in Stillwater.

And the athletic director can go back to one of his favorite things: not searching for head coaches.

Quarterback Alan Bowman, along with Eddie Sutton Foundation co-presidents Dave Hunziker and Larry Reece and volunteer Kelly Allen, present the "Superwoman Award" to ESF treasurer Katie Schofield at the 2024 Cowboys vs. Cancer Classic Golf Tournament. The annual service award is named in memory of Matt Allen, an OSU graduate who died in 2013 at age 46 from brain cancer. Held May 20 at Stillwater Country Club, the event helped raise a record $195,000 to impact the fight against cancer, support families and provide meaningful experiences for those a ected. For more info, visit theeddiesuttonfoundation.com

Some of Victoria and Todd Corbin’s favorite memories of their four kids growing up were when they played dress-up together.

Often the kids' costumes were the Corbins’ old Army fatigues.

“Some of our cutest pictures of them are in our uniforms,” Todd said. “They probably did that until I’d say maybe 10 or 11.”

Victoria interjected.

“Oh, make no mistake,” she said, “Lily was still princesses and stu like that.”

Lily Corbin was the oldest of Victoria and Todd’s children. The only girl, too. Even though she joined her brothers dressing up in their parents’ old military gear — a beloved family photo shows the kids posed by the pool, her three brothers in fatigues and Lily in a button-up dress shirt with the CORBIN nameplate still attached — she didn’t grow up as enamored with the military as her parents or her brothers.

Yes, she heard stories from her parents of their service, Victoria who was a captain in the Nurse Corps and Todd who was a captain in the Medical Service Corps. (They actually met at Fort Bragg when he went to the emergency room to investigate a patient complaint, asked for the nurse in charge, and the rest was history.) Sure, Lily was proud of her family’s service stretching back many generations.

But following in their footsteps?

“I wanted nothing to do with the military,” Corbin said. “Nothing.”

My, how things change.

Corbin, a junior on the Oklahoma State equestrian team, is a contracted cadet in the Army Reserve O cers’ Training Corps (ROTC) at OSU. That means she has already entered into a contract with the United States Army, agreeing to complete the ROTC program, become a commissioned second lieutenant upon graduation, and serve at least eight years of either active or reserve duty.

Her goal: become an aviator.

She wants to fly helicopters.

“Being an Army aviator is hard,” said Lt. Col. Bo Reynolds, who led OSU’s Department of Military Science for the past three years. “Our Army needs good pilots.

“But people like Lily, they’re fighters, they’re resilient, and those people to me are going to be successful.”

So, how did Lily Corbin go from wanting nothing to do with the military to wanting nothing more than to fly Army helicopters?

“It’s so hard for me to wrap my head around it,” she admitted.

But at the heart of it is something she has known since

she was little — she loves chasing goals, putting in the work needed to achieve something and doing everything in her power to be the best.

Lily Corbin was in kindergarten the first time she laid eyes on a horse.

“And it was love at first sight,” her mom said.

Victoria had ridden horses throughout her life and had told stories to the kids about her experiences. But when Lily saw that horse, something in her clicked: she wanted to ride Immediately.

So, she did what any 5-year-old would do — she begged.

“Please let me ride,” she would say to her parents. “Will you let me take riding lessons?”

The answer was always the same.

“No,” they would say.

Lily didn’t understand why not, so again, she did what any kid would do — she kept begging

“Please let me ride,” she would say.

“No, no, you’re not,” they would reply.

“Pleeeease.”

“No.”

The truth is, Victoria knew how amazing horse riding could be. It’s why she had done it for so many years. She loved it.

“But having grown up in that environment, I know what that involves,” she said.

The cost can be high. The time commitment can be intense. And for a young rider like Lily, safety can be a concern, too.

“You just don’t want to go head-down into this without really seeing if that’s what you want,” Victoria said. “So I purposely put her o .”

Victoria and Todd told Lily that she wasn’t allowed to ride for nearly two years. It wasn’t easy either, because every time she read about a horse or saw a horse on TV “or God forbid … saw one in person,” her mom said, Lily went gaga.

As Christmas rolled around during Lily’s second-grade year, Victoria and Todd realized her interest in riding wasn’t a passing fancy. They found a place where Lily could take riding lessons, and to let her know that she was going to be allowed to ride, they got her riding pants and boots for Christmas.

“When she opened those up,” Victoria remembered, “she went crazy.”

Her parents soon realized Lily wasn’t just a little girl fascinated with horses. She truly loved riding.

“WHAT I LOVE ABOUT LILY IS THAT SHE GIVES EVERYTHING. SHE’S ALL IN ON EVERYTHING SHE DOES.”

— LT. COL. BO REYNOLDS

When Victoria would take Lily to her lessons, there was a gate that had to be opened for the car, then closed. Lily would get out to take care of the gate, and by the time her mom pulled through and parked at the barn, Lily would be running toward her.

“Seeing her run and the smile on her face running towards me, towards the barn,” Victoria said, “it was that way every single time we did a lesson.

“It’s her happy space.”

Lily loved riding, even when it was di cult. When she started, she rode English style, which meant she rode English horses. Many of the breeds used are big.

Gigantic, Lily remembers them being.

Her first horse was an Oldenburg that stood 17.1 hands tall, a measurement for horses from the ground to the withers, the ridge between a horse’s shoulder blades just behind the neck. A measure of 17.1 hands is roughly 68 or 70 inches from the ground to the withers, tall enough for a rider to be able to look down on the heads of riders on most other breeds.

Lily was aware of that horse’s size constantly. Even walking with him, a skill that would be used in competition, was a struggle.

“We’re going too fast,” she would say.

“It’s just walking,” her trainer would say. “You’re really OK.”

“I’m not OK.”

But nothing kept Lily from riding. Not the size of her horse. Not the fear she sometimes felt when she climbed into the saddle and realized how high she was o the ground. That’s because she enjoyed way more things about it than she feared.

Still, her passion went to a di erent level after she attended an American Quarter Horse Association show in Oklahoma City with her mom. It was the first time Lily, then 7 or 8 years old, had seen Western-style riding.

Or more succinctly, the first time she’d seen the Western-style outfits

“They were all wearing these sparkly jackets with cowboy hats,” she said, her smile wide, her eyes dancing. “I was like, ‘That is it. That’s what I want to do.’”

She laughed.

“So I switched.”

Even though she was initially enamored by the bling, she quickly realized the Western style fit her better. She got to ride smaller horses, Quarter Horses mostly, and being younger, she was physically able to handle the horses better and grasp the skills quicker.

Plus, Western-style riding was more about the show, the performance.

“That’s what I like to do,” Corbin said.

And the more she rode, the more she relished going into the arena and competing. Sure, she enjoyed practicing, being in the barn and caring for the horses, but the competitor in her loved nothing more than working to be the best.

Competing was her favorite.

“I love that it’s just me and my horse,” she said. “There’s no one else I can blame. If I mess up, it’s on me. If I win, it’s also because of me and my horse.

“The waiting in the arena, standing in the center line while they’re calling out placings at the very end of the class and you’re the last one standing in the arena, that’s the feeling that I am always chasing.”

And over the years, Corbin had that feeling several times. She won enough that by the time she was in high school, she was thinking about riding in college. Still, she knew she’d have to trumpet herself because even though she’d been successful, she’d never won a world title. Do that in the equestrian world, and the college programs call on you.

She didn’t assume coaches would be seeking her out.

She sent résumés and videos to nearly every college program in the country, and several wanted her to visit, including Georgia and Texas A&M, which have both won National Collegiate Equestrian Association (NCEA) championships in the past decade.

But all along, Corbin had a top option.

“OSU had always been on the top of my list,” she said. “I live in Oklahoma. I gotta be loyal and true.”

Still, Corbin had no way of knowing if the Cowgirls, also national champs in recent years, would want her.

Lily Corbin attended a riding camp at OSU the summer before her senior year of high school.

She got to ride several of the team’s horses and be around the coaches, though she had known Cowgirl head coach Larry Sanchez for a decade. He often judges shows and had seen Corbin ride many times over the years.

Still, when Corbin left the camp, she didn't expect OSU would o er a scholarship.

“Not even a little bit,” she said.

But a couple of days later — Corbin just happened to be back in Stillwater for a cheer camp with the Jones High School cheer team — she got a phone call from Laura Brainard. Brainard coaches OSU’s Western riders.

“Do you have a minute?” Corbin remembers Brainard asking.

“Actually, not right now,” Corbin said. “Can I call you in a little bit?”

Corbin laughs now, not believing that she put o Brainard.

When Corbin called back later, the coach had news.

OSU wanted Corbin.

She broke down, crying tears of joy and disbelief. The equestrian program wanted her to be a Cowgirl. It was like a dream. A wonderful, unexpected dream.

Lily called her parents, and her dad answered. She asked if her mom was around, and when he said that she was sleeping after working a night shift, Lily asked him to wake her up.

That set o alarm bells for both Todd and Victoria.

“He wakes me up … and I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my gosh, what’s wrong with Lily?’” Victoria said.

Once everyone was on the phone, Lily didn’t exactly assuage her parents’ fears. She was crying so hysterically that they could barely understand her.

“What happened?” they asked.

“It’s really OK,” she said through sobs. “OSU just o ered me.”

That prompted tears to flow on the other end of the phone, too.

“I really did think, deep down, she wanted to be a Cowgirl,” Todd said. “But … they weren’t as aggressive as some of the other schools. So it just caught us completely o guard.”

Lily didn’t commit to OSU right away; her parents encouraged her to wait a couple of days just to make sure it was what she wanted to do.

She followed their advice, but she only felt more sure as time passed.

“I already knew that I was gonna go there,” she said.

“Going to OSU, regardless of being on the team or not, I’d be set up for success. So when they o ered me, I was like, ‘This is perfect. This is exactly what I need.’ So it was a no-brainer when I accepted it.”

A few months later, she had another o er that wasn’t so clear-cut.

The summer before Lily’s senior year of high school, her twin brother, Jack, began the process of applying for a national ROTC scholarship.

Their dad thought she should apply, too.

“Just to see,” he said.

She agreed to apply, but she felt pretty certain nothing would come of it. After all, she’d seen all the things that her brother had been doing that would make his application stand out.

“My résumé is cheerleading for four years,” Lily thought of her only extracurricular at Jones.

Still, she sent o the application and even completed a mandatory physical test. But then, she put the whole thing out of her mind — because she just didn’t see any way she’d get recognized.

But in March, only a couple of months before high school graduation, she received a letter.

“You been awarded a three-year national scholarship,” it read. Her reaction?

“I have a meltdown,” she said. “I am crying — ‘I don’t want to do this.’”

Corbin had always shunned the notion of military service because she feared the worst outcomes of armed conflict and war. Injury. Pain. Death.

“I don’t want to die,” she thought. She was set on not accepting the scholarship.

But then, her dad reminded her of a few things. The national ROTC scholarship wouldn’t kick in until her second year at OSU. She could take the beginning military science class without needing to sign a contract with the Army or make any long-term commitments. That would allow her to take military service for a test drive.

If she liked it, she could sign up for more.

If not, she could walk away.

Turns out, she didn’t like it.

“I loved it,” she said.

ROTC at OSU felt familiar to Corbin.

“I think it reminded me a lot of home,” she said.

The structure was similar to what her parents demanded of Lily and her brothers — Victoria and Todd preached respect and modeled organization, keeping color-coordinated calendars to track all of the kids’ activities — but so was being a female in a male-dominated group. It’s what she’d grown up around, her dad being a stay-at-home parent and her siblings all being boys.

Sure, the male cadets sometimes made her roll her eyes, but they were supportive, too.

“These guys will push you to your limits,” Corbin said, “but they’re gonna get you there.”

Never was that more evident than the first time she attempted the Army Combat Fitness Test, or ACFT.

It wasn’t.

About halfway through the battery of tests came the sprint-drag-carry.

“Which is arguably the worst part of the whole thing,” Corbin said. “You have to sprint 25 yards down, back. You have to drag this 90-pound weight down, back. You have to carry these kettlebells down, back. Shu e down, back. Sprint down, back.”

Plus, there’s a time limit.

“I mean, it’s awful,” Corbin said. “You can’t feel your legs. You’re shaking. You’re throwing up.”

But at one point, she heard an upperclassman holler at her.

“Come on, Corbin!” he shouted. “Give it everything you got!”

It surprised her.

“I was shocked that anyone knew my name,” she said.

It pushed her to dig down and keep going, and before she knew it, it felt like all the other cadets there were cheering her on.

She had one of her best times ever on the sprintdrag-carry.

Remembering that moment still gives her chills.

“Even though it sucked and I was really regretting all my life choices in that very moment, I was like, ‘This is my family. They care about me. They want me to do well. No one’s gonna let me fail here,’” she said.

They were there for her, so Corbin decided she wanted to be there for them.

She signed her contract with the Army after the first semester of her freshman year, a semester earlier than she needed to. But she felt certain about what she wanted.

ROTC now. Army later.

But that also meant that she was a major-college athlete on the equestrian team as well as an ROTC cadet. That would be like having two nearly full-time jobs in addition to being a full-time student.

“I said, ‘You know it’s not gonna be easy,’” said Coach Sanchez. “I said, ‘As long as the ROTC understands and can be flexible on some things that we have, I will be as flexible as I can be with things that they have.’

“And she’s made it work.”

When the equestrian team’s morning conditioning conflicts with ROTC’s physical training, for instance, Sanchez is fine with Corbin doing ROTC’s workout. He knows she is likely doing something more strenuous with ROTC.

“She’s not losing anything,” he said.

Other times, ROTC has allowed equestrian to take precedence.

Last September, the equestrian team had its Orange and Black Scrimmage scheduled for a Friday night. The intrasquad meet is the first competition on the team’s calendar, so the riders spend weeks getting ready for it.

But Corbin realized ROTC had Field Training Exercises that weekend. Because of her equestrian commitment, she could’ve asked to be excused, but she figured the scrimmage was only on Friday. Maybe she couldn’t travel to FTX with the other cadets, but she could still make most of the weekend.

So, she figured out a compromise.

She was the first rider up at the scrimmage, and as soon as she finished, she ran into the barn and changed into her fatigues. Her parents then drove her to FTX south of Tulsa.

“I try to split up my time evenly,” Corbin said, “but also give 110 percent e ort to both.”

Her attitude has made it easy for the equestrian coaches and the ROTC o cers to work with her. Both believe her involvement in the other activity is beneficial.

“I knew bringing her in that we’d have limited time with her,” said Reynolds, who was himself a Division I athlete having been a wrestler and football player for Army at West Point. “We knew that NCAA sports was gonna be taking up a lot of time.

“But I see value in her having that experience and then using that as part of her shaping and building and leadership and experiences to be a great Army o cer, too.”

Sanchez said, “I always say my busiest kids are my best kids, and she’s definitely proven that to be the case.”

Lily Corbin marvels sometimes at how her outlook on the future has changed.

Two years ago, she wanted nothing to do with the military.

Now, she is excited about doing at least four years of active duty once she graduates from OSU.

While she isn’t sure what her specialty will be — the Army determines that based on numerous variables, including test scores, grade point averages and extracurriculars — her goal is aviation

Her dad had a chance to fly helicopters while he was in the Army, and while he talked about some of his experiences, a lot of what he told Lily and her brothers wasn’t exactly rosy.

“Flying is cool, right?” Todd Corbin said. “It sounds cool to everybody, but it’s serious when you’re doing it … When you’re flying a helicopter and you have four people in there and you’ve got to set that thing down right beside a fuel truck and you can’t make any mistakes, it’s scary.

“People think of Top Gun, they think of the flight suit, they think if you’re going into a bar you can pick up guys if you’re a girl … That’s a bunch of bull. I’ve tried to give her the reality of having the responsibility of flying.

“It’s not for the faint-hearted, and it’s not for the cavalier.”

So it is with riding a half-ton horse.

And being a Division I athlete and an ROTC cadet.

Lily Corbin knows a thing or two about staying focused and being responsible. She doesn’t just show up on time; she’s always at least 15 minutes early. She doesn’t just show up either; she’s engaged in anything she does.

“She’s one of our best as far as her attitude,” said Sanchez. “Her attitude never wavered. She seems to always have a smile on her face.”

Reynolds, the former head of military science, said, “What I love about Lily is that she gives everything. She’s all in on everything she does.”

Today, her focus is on equestrian and ROTC at OSU.

Eventually, she will turn all her attention to military service, the one thing she didn’t want to do as a kid that has become the next thing she can’t wait to do in her life.

Big 12 Conference Football Media Days were held July 9-10 at Allegiant Stadium (home of the NFL's Raiders) in Las Vegas. Head coach Mike Gundy and Cowboy players Alan Bowman, Ollie Gordon II, Nick Martin and Collin Oliver met with the media ahead of the 2024 campaign. Commissioner Brett Yormark was among those mingling with the attendees, which included the four new members of the now 16-team conference.

Steve Lutz was a high school freshman the first time he chose basketball.

Growing up on the east side of San Antonio, the youngest of six kids in a Catholic family, he had played every sport. Track. Baseball. Basketball. Competition was his favorite thing, so he kept doing it all.

But one spring day while playing baseball for San Antonio East Central High School, he hit a shot to left field. He was going to leg it out for at least a double, but as he rounded first, his cleat got stuck.

He was wearing interchangeable cleats — metal one day, plastic the next — that screwed in and out

“Well, like any other 15-year-old kid,” Lutz said, “I probably didn’t do it correctly.”

His cleat stuck, but his foot kept moving.

His ankle broke.

Several months later, after missing the summer AAU basketball season and falling behind his teammates, Lutz realized he didn’t want any other sport to get in the way of basketball. He was done with baseball.

Never mind that he was better at baseball. Or that his dad had played some summer pro baseball and had a heart for the sport.

“My dad was so mad at me,” Lutz said, “he didn’t talk to me for like two weeks.”

The new Oklahoma State men’s basketball coach chuckled as he sat, arm slung across the back of a couch, in his Gallagher-Iba Arena o ce talking with me one afternoon this summer.

“Baseball’s so slow, right?” Lutz said. “I was a pitcher, I was third base, I was a catcher, but what do you get on third base? You get three balls a game?”

“Maybe,” I responded.

(Something you learn quickly about Lutz is that when he asks questions, they often aren’t rhetorical.)

“It was just too slow for me,” Lutz continued. “I just got bored.”

That broken ankle caused an epiphany: Lutz didn’t want to spend any more time on something he didn’t love nearly as much as basketball.

It wouldn’t be the last time he chose the sport.

As Lutz prepares for his first season as the Cowboys head coach — and his first as a Power Four head coach — he faces a daunting task. Rebuild a once-proud program that has just one NCAA Tournament win in nine years. Retool a roster that returns only three players. Reengage a fan base that has largely deserted Gallagher-Iba Arena, leaving it more reserved than rowdy. And do it all in a conference widely regarded as college basketball’s toughest.

No pressure.

Lutz is undaunted.

“First thing is, it’s happened in the past,” he said. “The best predictor of the future is the past, right? So you’ve just got to figure out a way to emulate a little bit of what Coach (Eddie) Sutton did, right?”

“Sure,” I agree.

“And how did Coach Sutton do it?” Lutz said. “He had some really good players, but he also had some guys that were tough and would fight you and they played really good defense, and they played the right way.”

That’s how Lutz plans to do it, too, though his philosophies for how to play really good defense and really good o ense are di erent than Eddie Sutton’s. But the toughness and the teamwork that Sutton’s squads had? Those are non-negotiable for Lutz.

He wants guys who want to succeed above all else, and they’ll give the e ort it takes to get there. That, after all, is what Steve Lutz has always done.

The second time Steve Lutz chose basketball he was majoring in business at Texas Lutheran, a small private university in Seguin, just outside San Antonio.

He’d had a solid career at San Antonio East Central High School, but recruiters weren’t all that interested.

Lutz couldn’t understand why.

“I think that I’ve been overlooked, right?” he remembered with a wry smile.

He decided to show all those recruiters how wrong they’d been by going to Ranger Junior College. Instead, he quickly realized he was the one who’d been wrong.

He couldn’t keep up athletically or physically.

“I was lucky Texas Lutheran still had a scholarship,” he said.

Lutz joined the team and enrolled in the business school, thinking he’d eventually go into sales. You needed to be competitive and able to build relationships, two things he leaned into.

But after his first accounting class, his adviser called Lutz to his o ce.

“Hey, Steve, I know you worked at this pretty hard,” Lutz remembers the adviser saying.

It was true: Lutz had studied and worked and gotten tutoring.

But he only managed a C.

“HE’S

—

“And you understand that there’s managerial, there’s strategic …” the adviser said, rattling o a long list of more advanced accounting classes that Lutz would have to take. “There’s like five more that are twice as hard.

“Do you want to spend that much time of your college career doing this?”

Hard pass.

As Lutz started thinking about what he wanted to spend time studying in college, then doing after college, some of the same faces kept popping into his mind. His coaches at Texas Lutheran. His coaches from high school. Even his coaches from some of his Catholic Youth Organization teams.

Lutz decided he wanted to be a coach, too.

The truth is, he was already doing some of the things that a young coach might. Not that he was doing them on purpose. It was just his personality.

“When it was time to have pick-up, I made the pick-up teams,” Lutz said. “When it was time on the weekend to have open gym, I told the guys when we’re going to have open gym.

“Friday and Saturday nights when things maybe in college get awry, I made sure everybody got out of there and I kept the peace, so to speak.”

His senior year, he was a team captain.

Still, he wasn’t a standout, much less a star. He didn’t make headlines, and truthfully, those were rare anyway for Texas Lutheran. He knew he wouldn’t get his first coaching job after college because of clout or even name recognition.

So did the man who gave Lutz his first job.

“Hey, Steve,” Danny Kaspar once joked with him, “you played three years at Texas Lutheran, and when you came to apply for my grad assistant, I didn’t know who the hell you were.”

Kaspar was coaching at Incarnate Word in San Antonio, but Lutz, who had spent all but a few months of his life in the San Antonio area, was unknown to Kaspar. Worse, when Lutz reached out about that graduate assistant job, Kaspar had already filled it

Guy by the name of Chris Beard, who’s been the head coach at Texas Tech and Texas and is now at Ole Miss.

“I already got somebody,” Kaspar remembers telling Lutz, “and they only give me money for one GA spot.”

But a week or two later, Lutz returned to Kaspar’s o ce.

Lutz had talked to a few other schools in and around San Antonio — he planned to live at home while he worked as a GA and took classes for his master’s degree — but he kept coming back to the feeling he got from Kaspar about how he ran his program.

“It was business,” Lutz said.

He knew working for other programs and coaches might be more fun than working for Kaspar at Incarnate Word.

“Man, you had a lot of fun in college,” he thought to himself. “You either need to figure this out or not.”

Lutz had a proposal for Kaspar.

“Coach, what if I just volunteer?” Lutz said.

“I can let you do that,” Kaspar told him. “But Steve, understand that if you’re going to do that, you’re going to be like a walk-on. A walk-on gets no scholarship money, but has to do everything the scholarship guys do.

“If you’re going to take this job, I don’t want to hear, ‘Well, Coach, I came in late and you’re on me, but I don’t get any money.’ I’m not going to hear that.”

The first day Lutz came to work, he didn’t call recruits or watch video or help with practice. Instead, he and Beard were given paint and brushes and told to go paint the locker room.

“Both Beard and Lutz looked at me like I’m crazy,” Kaspar said.

But they did it.

Beard, of course, was getting paid. Lutz wasn’t.

But he just kept working.

“There’s a lot of young men that think they want to coach college,” Kaspar said. “They don’t understand the time, the work, the e ort that goes into it.”

Kaspar could see that Lutz understood. He proved it by always showing up, always working hard.

After a month, Kaspar rewarded Lutz with a $200 monthly stipend, though Lutz remembers it being a $2,000 yearly stipend with a slightly di erent monthly paycheck.

“$186.13,” he said, rattling o the exact number nearly 30 years later.

The pay was minimal. Glitz? Glamour? Nonexistent. Lutz loved it.

As much as Steve Lutz embraced being a volunteerturned-grad-assistant at Incarnate Word, he knew he couldn’t stay in the position forever.

Not if he ever wanted to move out of his parents’ house. And slowly but surely, Lutz started moving up.

Beard left for Abilene Christian the next year, and Lutz took over the vacated grad assistant spot.

Then the next year, Kaspar’s lead assistant coach moved to Texas A&M-Kingsville, and Lutz became a full assistant.

Salary: $20,000.

“I’m lovin’ life,” Lutz said. He even had enough money to buy a car, a Ford Explorer.

“And the payments are $406.84 a month,” he said with a smile.

While the salary increase was no small thing, Lutz knew he needed to continue to climb to expand his knowledge. Kaspar had taught him all about planning and strategy, but what about recruiting and competing and budgeting and all the other things that had to be done at the highest levels of college basketball?

Lutz decided to move to Garden City Community College in Kansas. At the junior college level, coaches are always recruiting, and players are always being recruited.

“So I expanded my network 10 times in 10 months,” Lutz said.

Jeremy Cox, who had met Lutz a few years earlier when they were assistants in the San Antonio area, wanted Lutz on his sta when he took over as head coach at Garden City. That’s because Cox knew he’d never be able to find anyone in college coaching who worked harder than Lutz.

“He’s a relentless, ferocious worker,” Cox said.

Cox rewinds to a night Garden City played a game three hours away in Co eyville. The team got back from Co eyville late, but early the next morning, Lutz was on his way to North Carolina.

“Drove out there that day,” Cox recalled, “and two days later, he was back in Garden City with a kid.”

A recruit, actually. Because Garden City’s recruiting budget was small, flying in recruits wasn’t an option. Someone often had to go get them, and Lutz never shied away from the duty.

The same went for recruiting.

Cox remembers going after a recruit from Manhattan, Kansas, about four hours from Garden City. Whenever he played a game, Lutz would be there to watch.

Often the recruit’s games were on Tuesdays and Fridays.

“He’d be back that night or early the next morning,” Cox said of Lutz.

That was because Garden City played on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

“The entire season, he never rented a hotel room, never stayed in a hotel room, just lived in a car, worked in a car, didn’t have a cell phone, stopped on the side of the road and talked on the pay phone and kept moving and never complained,” Cox said. “That was just the way it was, and that’s just the way he has been his entire career.” Today Cox has a new title, assistant coach at Oklahoma State.

Lutz kept grinding as an assistant for the next two decades. He went to Stephen F. Austin for six seasons — reuniting with Kaspar — then SMU for four, Creighton for seven and Purdue for four.

Lutz learned lots at all those stops, but more than anything, he refined his basketball vision.

In other words: “When you get to choose how you’re going to play,” Lutz said, “that’s my druthers.”

And his druthers are aggressive defense and up-tempo o ense. His defensive philosophy will be familiar to Cowboy fans with heartstrings attached to Henry Iba and Eddie Sutton, but Lutz’s o ense will be something di erent.

Lutz’s first three seasons as a head coach — two at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, one at Western Kentucky — those three teams averaged 78.0 points.

Two of them scored over 80 points a game.

In the past 20 years, OSU has had only four teams average more than 78.0 points a game. And the Cowboys had way more teams during that stretch average in the ’60s (nine) than in the ’80s (two).

Lutz’s style preference has nothing to do with his personality (baseball was too slow, remember?) or even his background. His high school coach, Stan Bonewitz, loved up-tempo o ense and averaged over 100 points a game many seasons. Creighton under Greg McDermott plays fast, too.

Rather, Lutz believes in playing fast because of the math.

“If you can get a 75-possession game versus a 63possession game, you’ve got 12 more opportunities to survive mistakes and 12 more opportunities to make a three,” he said. “You’re just giving yourself more opportunity.”

Maybe better opportunities, too.

“When you really look at basketball, your best opportunity to score is before the defense gets set, right?” Lutz said. “And let’s just be honest: in this league, there’s some really, really good coaches. So if you’re going to play in a chess match with them in the halfcourt, and you don’t have better talent or equal talent, you’re gonna have a hard time. So the more you can play in transition, the more you can play before things get set, you should have a better success rate.

“To me, that’s kind of the premise of it all.”

Steve Lutz has always chosen basketball even though it hasn’t always been easy.

Sure, his love for the game and his passion for coaching have never waned, but still, there have been di culties. Last year, for example, Lutz and his wife, Shannon, decided he would move to Western Kentucky when he got the job there while she and their two youngest kids stayed behind in Corpus Christi.

Their middle child, daughter McKenna, was soon to be a senior in high school, and they didn’t want to uproot her before that year, which would’ve been her third high school in four years.

Lutz believes it was absolutely the right decision, but man, was it di cult.

Lutz’s dream job, after all, is stay-at-home dad.

“Heck, yeah,” he said. “I love to tell my wife that all the time: ‘You can make all the money in the world; I’ll stay at home, have dinner every night, get the yard mowed, go pick up the kids.’

“I would have been fine with it.”

He still finds ways to be there as much as possible when his kids have big events, games or assemblies. He involves them as much as he can, too; oldest daughter, Caroline, used to pick out his ties before games, for instance, while son, Jackson, was there for a bunch of morning workouts this last summer.

It isn’t perfect.

“He’s made a lot of sacrifices just like anyone does in their career,” Lutz’s older brother, Mike, said.

“You have that dream and you just pursue it.”

Steve Lutz did just that. He chose basketball, then worked to make it the right choice.

Third baseman Aidan Meola hoists the Phillips 66 Big 12 Baseball trophy aloft as Oklahoma State celebrates the tournament championship at Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas. The Cowboys captured the 2024 conference crown with a 9-3 win over Oklahoma. Carson Benge (an eventual first round draft pick by the Mets) was named the Most Outstanding Player of the tournament. The victory gave OSU its 35th conference championship in program history, with six of those coming in the Big 12. OSU finished 4-1 against the Sooners this past season, and head coach Josh Holliday owns a career 37-14 record against the Pokes' Bedlam rival.

STORY BY

PHOTOS BY CLAY BILLMAN

BRUCE WATERFIELD

GARY LAWSON AND ANTHONY FAMILY

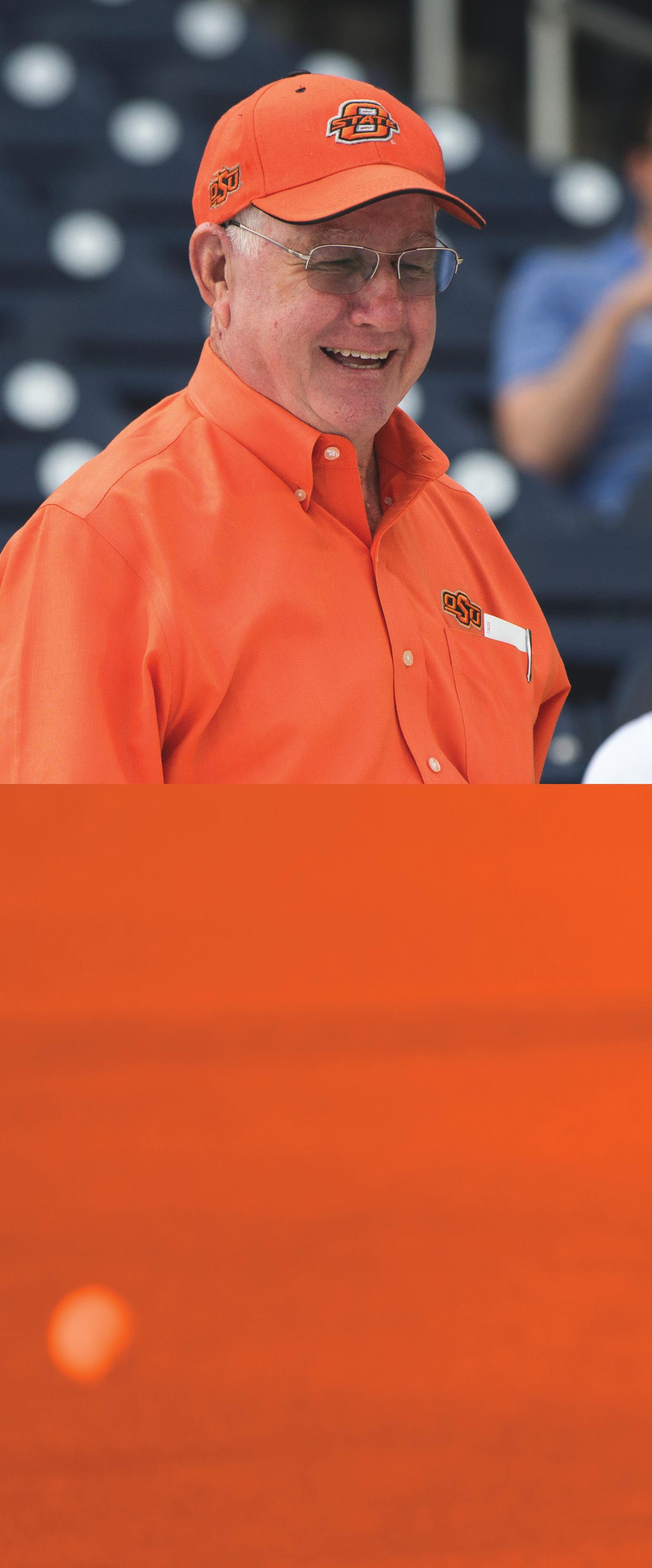

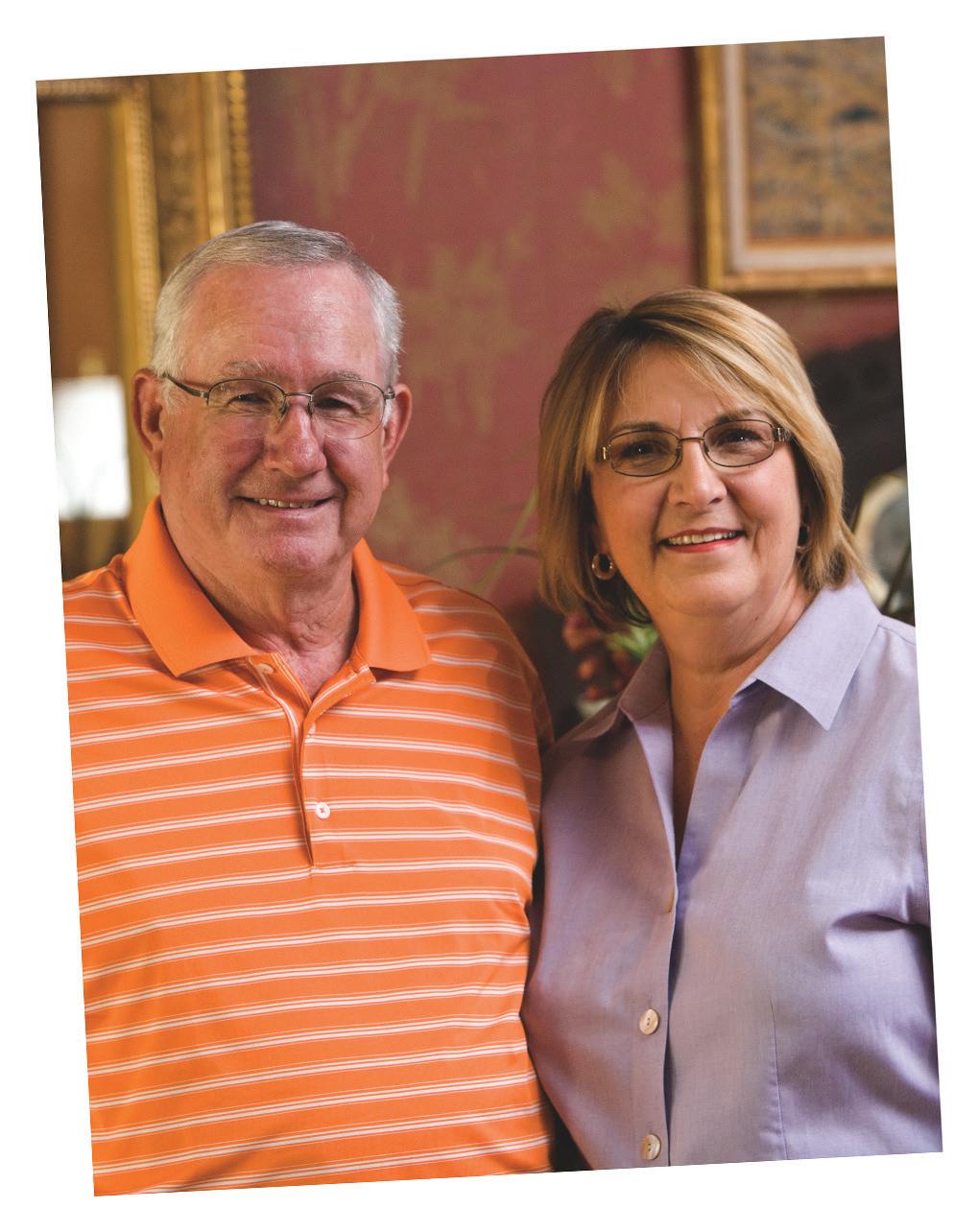

Everybody knows Calvin Anthony. (At least everyone who’s spent time in Stillwater over the last half-century does.)

- Perhaps the long-time pharmacist filled their prescription. If not, surely they recognize the familiar voice from decades of Tiger Drug commercials on local radio.

- Maybe he was their elected o cial. The soft-spoken statesman served in the Oklahoma House of Representatives and had a stint as Stillwater’s mayor in the 1980s.

- As a member of the Oklahoma A&M Board of Regents for two terms, Calvin may have overseen their time on campus as an Oklahoma State student, faculty or sta member.

- It’s likely they encountered Calvin at any number of OSU athletic events, home and away. Whether it’s the welcoming smiles tailgating outside Boone Pickens Stadium, encouragement coming from the box seats at O’Brate, or cheering courtside at Gallagher-Iba Arena, Calvin and his wife Linda rarely miss a game.

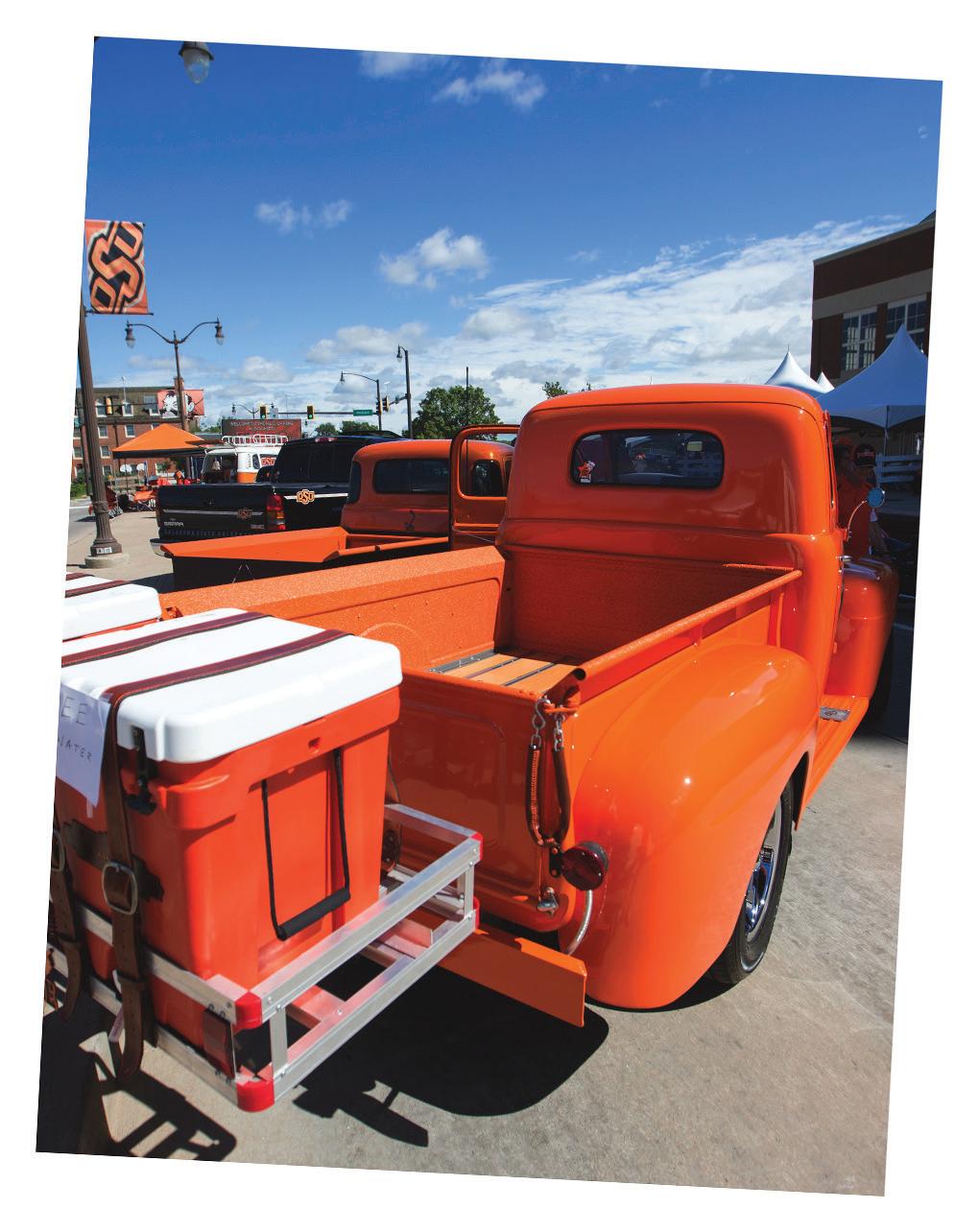

- Surely, they’ve seen the head-turning, orange ’48 Ford pickup in the Homecoming parade or tooling around town.

Ellen Ayres, OSU’s associate AD for annual giving (a lifelong Stillwater resident herself), knows Calvin in all of the above roles.

“As a pharmacist, as a Regent — my boss — as an OSU donor and ticket holder … Calvin is just a constant,” she says. “He and Linda are always here. Always smiling. Always supportive.

“There’s probably no ballgame, tailgate, postseason, away game or event that you wouldn’t see Calvin and Linda Anthony there. Every trip that I’ve been on, they were there. They’re always supporting, whether it’s through season ticket purchases or generous gifts that they have given. They always buy a table for the POSSE Auction. They’re everywhere.”

As Top 150 all-time donors to OSU Athletics, the Anthonys have left an indelible mark on the program, not to mention to the entire university.

Celebrating a lifetime of service to the state, Anthony was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 2020. In February, he joined the Class of 2024 in the OSU Hall of Fame, presented by the OSU Alumni Association.

“Calvin and Linda are genuine, kind and incredibly passionate when it comes to Oklahoma State University,” Ayres says. “They are the definition of Loyal and True.

“I’ve known Calvin my entire life as the pharmacist in town, part of the community,” she adds. “Growing up in a place like Stillwater, you had the grocer, the insurance agent, the barber, the pharmacist … For me, it was Dwight McCormick, Kent Houck, (Whisperin’) Richard Danel and Calvin Anthony. They were all very successful businessmen, but also just so incredibly kind.”

Calvin grew up about 20 miles south of Stillwater in Carney, “where the pavement ends and the West begins,” he likes to say.

The local population around that time was 225.

“There were 12 in my high school graduating class in 1963. When I was speaking publicly a lot, to pharmacists or other groups, I’d tell them I graduated in the top six!”

Truth be told, Calvin was valedictorian. School was important to the Anthony family, he says, despite his parents’ lack of formal education.