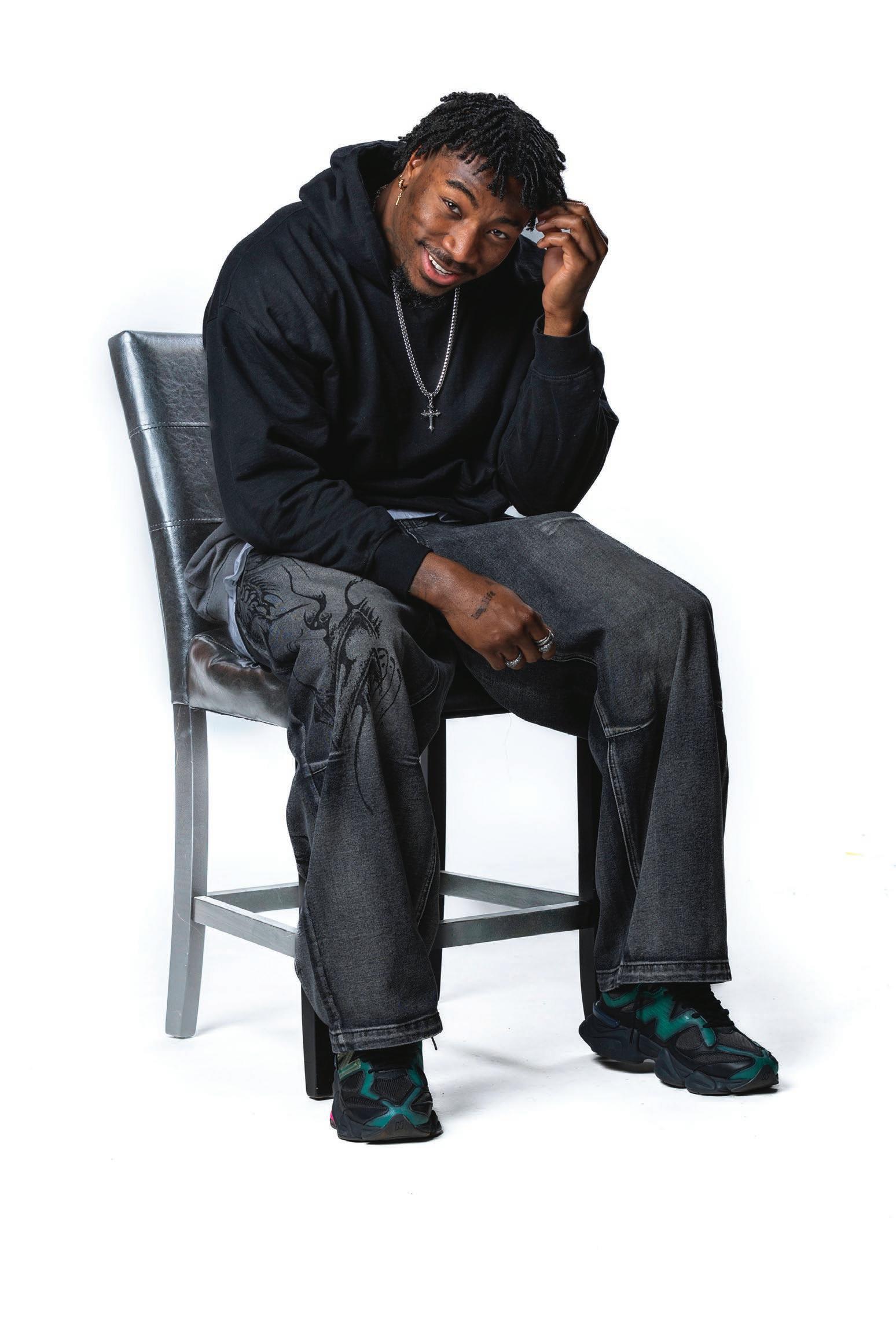

NICK MARTIN

PLAYING OLD SCHOOL IN A NEW AGE OF COWBOY FOOTBALL

BY KEVIN KLINT WORTH

BY KEVIN KLINT WORTH

PLAYING OLD SCHOOL IN A NEW AGE OF COWBOY FOOTBALL

BY KEVIN KLINT WORTH

BY KEVIN KLINT WORTH

The next time you bump into one of the ticket o ce sta ers from OSU Athletics, maybe give them a hug. Or at the very least, please don’t take a swing at them That’s happened a lot lately.

It has been a long couple of years for those folks due to some things that are completely out of their control.

Here’s what happened: In the not-too-distant past, 2018 to be exact, OSU tugged a loose thread on a sweater and things began to unravel. And the next thing you know, the ticketing sta started looking like Rocky Balboa in Round 15.

Innocently enough, OSU underwent an assessment of Boone Pickens Stadium six years ago.

“Instead of just blasting o coating that was 10 to 12 years old and recoating, we discovered that the concrete through the north and south sides of the stadium was beginning to reach the end of life,” according to OSU’s senior associate athletic director for facilities Kyle Waters

Immediately the project was bigger, and more expensive. And the more hoods that were looked under, the bigger the project became. Building codes had changed, as had fire codes, which would result in a smaller capacity for the stadium. And the administration had to consider the future, not just the past, or even the present.

“We knew we needed to do something for the next 50 years,” Waters said. "We didn’t really have an option. We could not go back to the original design.”

On the heels of the discovery phase of the stadium status, OSU announced a two-year, $55 million renovation of the seating bowl. Although maybe not as publicized as some of OSU’s other capital projects over the last 15 years, only the west end zone of Boone Pickens Stadium has been more expensive.

And thus, the ticketing folks entered the era known as the “reseat” although they probably have more graphic terms for it. It simply means that due to the changing configuration of the stadium, see the completed north side for example, roughly 70 percent of Oklahoma State’s season ticket holders would experience some sort of change to their football seats.

“For many fans, the changes are nothing but positive,” said Alec Proctor, OSU’s associate athletic director for ticket operations. “There were changes on the 200 level of the north side that people were ecstatic about. We’ve gotten a lot of positive feedback.”

Some of those changes included permanent chairback seats in eight sections, providing more legroom on the 200 and 300 levels, an extremely popular grab-and-go concessions option on the plaza and elevated first rows of the 300 sections, which allow seated fans to see over those passing through the cross aisle.

“But there are some folks who viewed it as a negative for very understandable reasons,” said Proctor.

Experience has taught us that the negatively a ected are usually the loudest segment. Again, understandably so. No one signed up for the changes, including no one in the ticket o ce.

There is currently no one in OSU Athletics who can recall the last time that Lewis Field or Boone Pickens Stadium seating has undergone such an overhaul in seating. In fact, it’s darn likely that it had never happened before the 2023 north side renovation.

“People like their neighborhoods,” Proctor said. “They’ve been sitting with the same group of people for years. It’s their game-day family. There are fans that sit in the same seats they had has a child with their grandparents. It’s tradition.”

OSU Athletics has always been aware that no one cares more about Cowboy Football than those season ticket holders who come back, year after year. There is also no one more invested, emotionally, or financially. Thus, OSU Athletics was caught between a rock (or decaying concrete) and a hard place. The upgrades to the stadium simply had to be made, resulting in all sides being caught in the crossfire.

And even the ticket o ce personnel, who live and breathe tickets and seating 365 days a year, were surprised by some developments during the north side renovation as the 2023 season drew near.

“It was a major project so there were a few twists and turns,” according to Proctor. “We ended up with an additional 85 seats in one section that we didn’t know were going to be available. So maybe you thought, and we thought, you were going to be on an aisle. Suddenly there are five seats between you and the end of the row. Imagine that in every row of a section.”

Time to call the ticket o ce.

“The top row of the 300 level was missing three weeks before the Central Arkansas game,” Proctor said. “Three hundred people suddenly didn’t have a seat for the opener. That was a 5:30 p.m. phone call on a Friday. I remember that specifically. It turned out to be a pretty easy fix, construction-wise, but we didn’t know that at the time.”

A narrow miss. Could have been 300 people thinking the same thing. Time to call the ticket o ce.

This all brings us to the spring and summer of 2024 and the renovation and musical chairs on the south side of Boone Pickens Stadium.

“The north side was actually the smaller project of the two,” Waters said. “That’s why we started over there. The 300 level of the north was in great shape and didn’t need to be part of the project. By starting on the north, we were able to learn best practices and implement those into the south side project.”

On the south side, the 300 level is included in the project. More people will be a ected. More people will have the ticket o ce on speed dial.

With large numbers of season ticket holders displaced over the two years, donation levels became the only system that could be fair to everyone. Or as some might say, equally unfair to everyone.

POSSE Priority Points is the only system in place to guide the re-seat process. That school of thought exists on every campus in the country.

“A ticket holder’s entire history is taken into consideration,” said Emma Kelley, OSU’s associate athletic director for marketing and fan engagement.”

Everything from years as a POSSE

member, years as a season ticket holder, number of programs a fan supports through donations, and university a liations, including alumni, the O-Club and faculty and sta status. The Priority Point system has been used for many years for the season ticket seat upgrade process, seat selections for our new stadiums and more recently the re-seat of the 100 level of Gallagher-Iba Arena.”

Logan Ho erber serves as Oklahoma State’s director of ticket sales and fan relations. He and his sta are on the front lines with Cowboy and Cowgirl fans on good days and bad days.

“I was a student at OSU,” he said. “I worked in the ticket o ce as an undergraduate, and then was fortunate to come on full-time as a coordinator. OSU means a lot to me as it does to our fans. I understand the frustration. The process of picking new seats is daunting. But from my experience, you only get a handful of fans that are very upset.”

In a few months, Oklahoma State embarks on a new era. An evolution of the

Big 12 will be underway. Boone Pickens Stadium will be visited by the likes of Arkansas and Utah this fall. And Ho erber, for one, is looking forward to it.

“OSU is a family and when we come together with 50,000 other family members to celebrate, the passion we all share makes it worth it.”

Rocky recovered from his bruises and made a sequel or seven. And when kicko arrives for the 2024 season, the ticket o ce folks will still be there, doing their best to accommodate every request they possibly can.

“We have a large number of season ticket holders,” Proctor said. “But over time it is amazing how many of them you get to know on a personal level. We know we can’t make everyone happy all of the time. But we will darn sure do our best.”

MORGYN WYNNE’S LEADERSHIP ON AND OFF THE SOFTBALL DIAMOND

COWBOY FOOTBALL’S NEXT ERA IS DEFINED BY NICK MARTIN’S OLD SCHOOL MENTALITY

BRUCE AND SHERYL BENBROOK’S LOYALTY THAT OSU CAN BANK ON

CHAD WEIBERG LOOKS AT THE BIG 12’S FUTURE IN OUR EXCLUSIVE Q&A

KAREN HANCOCK’S COMMITMENT TO OSU TAKES HER INTO A NEW LEADERSHIP ROLE

A bird's eye view of Bedlam baseball, as Carson Benge crosses home plate at O'Brate Stadium on Sunday, April 7. The Cowboys won the rubber match 9-5, taking the series for the 9th time in 11 seasons under head coach Josh Holliday

POSSE MAGAZINE SPRING 2024

POSSE Magazine Sta

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF / SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR KEVIN KLINTWORTH

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR JESSE MARTIN

ART DIRECTOR / DESIGNER JORDAN SMITH

PHOTOGRAPHER / PRODUCTION ASSISTANT BRUCE WATERFIELD

ASSISTANT EDITOR CLAY BILLMAN

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS COURTNEY BAY, HABBIE COLEN, CHASE DAVIS, JEROD HILL, MASON HARBOUR, GRAYSON JONES, GARY LAWSON, SEBASTIAN MANZANARES, ADDISON SKAGGS, ABBY SMITH

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS CLAY BILLMAN, ANDREA HANCOCK, HALLIE HART, KEVIN KLINTWORTH, JACOB UNRUH

Development (POSSE) Sta

ASSOCIATE AD / ANNUAL GIVING ELLEN AYRES

PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR CLAY BILLMAN

ASSISTANT AD / ANNUAL GIVING BRAKSTON BROCK

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ANNUAL GIVING STETSON DEHAAS

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT MATT GRANTHAM

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT DANIEL HEFLIN

SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD / EXTERNAL AFFAIRS JESSE MARTIN

SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT LARRY REECE

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT SHAWN TAYLOR

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ANNUAL GIVING ADDISON UFKES

ATHLETICS PROJECT MANAGER JEANA WALLER

OSU POSSE

102 ATHLETICS CENTER STILLWATER, OK 74078-5070

405.744.7301 P 405.744.9084 F OKSTATE.COM/POSSE POSSE@OKSTATE.EDU

ADVERTISING 405.744.7301

EDITORIAL 405.744.1706

At Oklahoma State University, compliance with NCAA, Big 12 and institutional rules is of the utmost importance. As a supporter of OSU, please remember that maintaining the integrity of the University and the Athletic Department is your fi rst responsibility. As a donor, and therefore booster of OSU, NCAA rules apply to you. If you have any questions, feel free to call the OSU O ce of Athletic Compliance at 405-744-7862 Additional information can also be found by clicking on the Compliance tab of the Athletic Department web-site at okstate.com

Remember to always “Ask Before You Act.”

Respectfully,

BEN DYSON

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR FOR COMPLIANCE

Encourage the future Cowboy you know to experience the beauty and innovation of OSU’s campus by checking out our virtual tour or scheduling an official visit.

With virtual tours, daily walking tours, weekend tours and special events, there is a right fit for the student you know!

Oklahoma State benefactor and Cowboy Baseball stadium namesake Cecil O'Brate passed away Jan. 20 at the age of 95. "Cecil was a remarkable person," said OSU Director of Athletics Chad Weiberg. "He was a fearless entrepreneur, a pioneer in business, a di erence maker in his community and an extremely generous philanthropist ... Cecil was the ultimate game changer for the Cowboy Baseball program, our players, and fans alike, for generations to come. He lived by his creed of 'Make It Happen,' and that is exactly what he did every single day."

Cowboy Baseball players watch a postgame fireworks display over the O'Brate Stadium outfield wall on Saturday, April 13. Throughout the day, OSU celebrated the life and legacy of Cecil O'Brate, whose generosity made the state-of-the-art stadium a reality. Showing some fireworks of their own, the Cowboys notched a 12-5 victory over Cincinnati. With the win, Josh Holliday's squad clinched its fourth-straight Big 12 series and went on to sweep the Bearcats.

st y by

photos by Andrea Hancock

st y by

photos by Andrea Hancock

Morgyn Wynne knew it was a moonshot as soon as the ball hit her bat.

“I didn’t even have to watch it. I knew it was going 300 feet,” Wynne says.

It was the top of the sixth inning in a College World Series elimination game against Tennessee. The Lady Vols’ starting pitcher had been tough as nails all day, and the Cowgirls were down by three runs. Wynne was at the end of her last year of eligibility. When she walked up to the plate, she knew there was a good chance it was the last at-bat of her career

She took the first three pitches — strike one, strike two, ball one. Then, on that fourth pitch, she swung with all her might.

“At the time, I was very in tune with my swing, and I knew what part of my bat that [the ball] had to come o of, and how my swing had to feel — when everything goes right, I know exactly what it feels like. And in that moment, the second I hit it, I knew it,” Wynne says.

The contact made her hands feel like they were ringing. She threw her arms in the air, and she was halfway home before the ball landed.

The Cowgirls’ rally e orts fell short, though, and they went on to lose 3-1, ending the team’s postseason run and Wynne’s softball career. But now, looking back, Wynne says

she thinks something special happened that game last June — her home run was a perfect farewell, a love letter to the sport she had played since she was nine years old.

“It was like a cherry on top,” Wynne says. “I was okay walking away from the game knowing that I gave it all I had left.”

She attributes part of that post-softball serenity to the way the sport set her up for the rest of her life. That’s the thing about Wynne — she could show you her power when she was hitting tanks on the field, but she wields a very di erent kind of power o it. Since 2021, Wynne has served as the Big 12’s representative on the NCAA Student-Athlete Advisory Committee, making her one of 32 individuals tasked with representing over 190,000 student-athletes competing in Division I sports. Since 2023, she has served as one of two student-athlete representatives on the Division I Council, a group of athletic directors, conference commissioners and other administrators responsible for the day-to-day operations of Division I athletics.

Wynne was tossed into a whirlwind, taking the drama of new NIL and transfer portal rules in stride. Making her voice heard in a male-dominated space didn’t faze her, either — she grew up with five brothers, and that taught her how to stand her ground.

“It’s a very hard feeling to describe, when you’re in a room full of athletic directors and conference commissioners, and you’re talking about the hottest topics, and they’re like, ‘Morgyn, what do you think?’ It still blows my mind to this day,” Wynne says.

Wynne’s responsibility is to represent student-athlete perspectives, often in rooms full of people who never participated in college sports as athletes. She says it’s been a long fight to get student-athletes into the spaces where decisions are made — Wynne is only the third student representative to sit on the Council — but there’s been a lot of progress in the three years she’s been part of the NCAA SAAC.

“We’re very new in the governance structure, and so when I look back on three years ago, when we didn’t have anybody on the Board of Directors, or the Board of Governors, I’m like, ‘Wow, we used to not be heard at all.’ And then now, three years down the road, they look at me to answer every question they have and provide every perspective on certain topics, and I think that’s huge,” Wynne says.

Wynne first got involved in the world of student-athlete governance at the University of Kansas, where she spent her first three years of college. KU’s SAAC had much higher participation rates than OSU, and the softball team in particular was deeply involved.

“My teammates were like, ‘Come to SAAC, it’s basically like high school leadership,” Wynne says. “I was in leadership throughout my high school career, and so when my teammates were like, ‘Come to SAAC, we plan the community service, the social activities and all that stu ,’ I was like, ‘Oh, sign me up, I want to do that.’”

Wynne served as SAAC vice president her junior year, and was elected to serve as president her senior year. But while she loved how involved KU’s student-athletes were in athletic administration, her experience playing softball there left her restless. She thought about nine-year-old Morgyn and the dreams she had when she first fell in love with the sport.

“I wanted more for myself, athletically,” Wynne says. “That little softball girl, that little softball Morgyn, always had a dream to win and to make it to a World Series and go to the postseason. And I knew KU was never going to do that for me.”

Morgyn entered the transfer portal ahead of her senior year. Her decision ultimately came down to the University of Washington — a little closer to her hometown of Pittsburg, Calif. — and Oklahoma State. Wynne had a full ride scholarship at KU, and she knew she wouldn’t have such a setup at her new school, but she had the vision to start

her own eyelash extension business to help pay for school, and the prospect of working her way through college was well worth the reward of joining a program with a winning culture.

“I needed to go to a program that shared those same beliefs and held that same standard,” Wynne says, “and so I was willing to walk away from KU for that.”

Cowgirl softball head coach Kenny Gajewski remembers his first conversation with Wynne vividly. He was sitting in his truck in a parking lot on campus. They talked about softball, and then he asked what she wanted to do after her playing career was over — a question Gajewski says he’s asked a thousand di erent recruits. Wynne gave him an answer he’d never heard before.

She told him she wanted to be an athletic director

Gajewski was surprised, but he rolled with it. In fact, he told Wynne she should shoot even higher and strive to become the president of a university, promising to connect her with OSU President Kayse Shrum as a mentor.

“I can remember telling her, ‘Look, I want you to come here to change the culture of what we have inside our athletic department. And that’s kids that want to be involved in SAAC and the NCAA, and everything that you want to do. You can do that here, and as a matter of fact, you can not only do it here, but we’re going to help you make it happen,’” Gajewski said.

Then, Gajewski got o the phone with Wynne, walked into the o ce and told his sta , “I’m going to get this kid. This is more than softball. This kid is going to change so many things here at OSU.”

Wynne ultimately decided OSU would give her the best opportunities, both on the field and o . Gajewski made a call to Jawauna Harding, OSU’s associate athletic director in charge of student-athlete leadership and development.

“He said, ‘I have this girl, she was at KU. Jawauna, she’s amazing. I think you need to just sit down and talk with her and just see what her goals and motivations are,’” Harding says.

Harding called Wynne into her o ce, and after hearing about Wynne’s involvement in SAAC at KU and her vision for improving the student-athlete experience, Harding knew she would be a great candidate not only to revitalize OSU’s SAAC, but to represent the entire Big 12 at the NCAA level.

“She was right o the bat like, ‘What are your goals, what do you want to do? I heard that you were involved in SAAC at your last school. SAAC doesn’t really exist here right now, but if you’re interested in helping me rebuild it, let’s do it,’” Wynne says.

Wynne set out to get more student-athletes involved in SAAC and make sure their voices were heard by the athletic department. Wynne, Harding and Gajewski all listed improving parking availability as one of her biggest accomplishments with OSU’s SAAC, a feat all three acknowledged may sound trivial, but had a major impact on the day-to-day lives of student-athletes.

“Athletics sits away from campus, if they have on-campus classes, or training or physical therapy, or doctor’s appointments, their life is here, right? And so when they’re trying to get between classes, or get to the academic center, or get to their scheduled appointments, parking can be a stressor,” Harding says. “For Morgyn, even though it doesn’t seem like that big-picture, large, strategic plan, she’s willing to take on even the small things.”

Gajewski says Wynne’s leadership inspired her teammates, and during her time as an athlete, the softball team had the highest participation rate in SAAC.

“I think as athletes, they just get so focused on a couple things — school and playing, a lot of times — that they just feel like their voice isn’t heard, or doesn’t really matter,” Gajewski says. “But she was able to convince them, ‘Look, the more people that show up at this, the faster we can get things done.’”

While Wynne got to work improving SAAC, Harding pushed her to apply to represent the Big 12 at the NCAA level. Wynne was hesitant, worried about the prospect of rejection. But Harding told her the only way to be certain of failure was by not trying in the first place, and Wynne submitted an application.

“And then, maybe a few weeks later, I got that call, ‘Well, we chose you.’ And I was like, ‘Wait, what?’” Wynne says.

While she was moving up in the ranks in the world of student-athlete governance, Wynne struggled that year on the field. It was a di cult time as she sought to untangle her challenges on the field from her overall sense of self. She doubted every decision she made, asking herself, “Was I supposed to be here? Did I make the wrong choice? Should I have gone to Washington? Should I have just stayed at KU?”

“But the one thing I didn't question was what I was doing o the field,” Wynne says. “I think the biggest thing it taught me was that I’m more than just an athlete.”

Gajewski says that even though Wynne was going through inner turmoil, she showed no quit. The resilience she exhibited reminded him why he chose to coach in the first place.

“You coach to be able to see the growth in young people, and her growth from a kid who walked into our program and was coming o a really, really good year at KU, and to watch her struggle for a period, it never deterred her. She just kept coming, and kept showing up, and doing whatever it takes,” Gajewski says.

Wynne bounced back the next season, significantly improving her batting average and playing in nearly twice as many games, a testament to her work ethic.

“That solidifies for me why she’s going to be so successful in what she wants, because she’s willing to go do whatever it takes to make it happen,” Gajewski says. “She did that here. She did that here as an athlete, and she did it o our field.”

Last year, Harding and Wynne had a conversation that gave Harding flashbacks to the first time she tried to convince Wynne to apply to the NCAA SAAC. Harding was trying to encourage her to apply to be recognized as a Senior of Significance, a designation given to about 50 graduating seniors each year. Once again, Wynne was hesitant. She was busy in the middle of her last softball season and didn’t think she would be selected, so why should she even try?

But Harding wouldn’t hear any excuses.

“I was like, ‘No, you’re applying for this. I’ve already written your recommendation letter. I sent you the link, I need this done by tonight at midnight, send me a text when it’s done,’” Harding says, laughing a little. “Not to say I was hard on her, but I knew that accomplishment and achievement was something she strives for, and this was another way to recognize her for the work that she had done.”

When the 2023 class of Seniors of Significance was announced, Wynne was not only one of the 52 students named — she was also named an Outstanding Senior, an honor bestowed on only a dozen students every year.

Like her home run against Tennessee, it was a “cherry on top,” a moment to recognize all the work she had put in.

Now, Wynne is seeking a master’s degree in educational leadership from OSU. She’s working as a graduate assistant in the athletic department, assisting with Student-Athlete Development and fundraising with the POSSE. She also still serves on the NCAA SAAC, a term expiring in May. After that, Wynne’s not sure — maybe law school, or maybe seeking a job in university fundraising. Long term, though, she’s taken Gajewski’s advice and decided to strive for something a little loftier than being an athletic director.

She’s thinking more along the lines of becoming the commissioner of a power conference. While the Pac-12 Conference has a recently-named female commissioner for its final months of existence, there is ground to be broken.

“I’m okay with being ‘the first,’” Wynne says. “The first woman to be the commissioner of a power conference, or I would be fine with being the first Black female commissioner. Because if not somebody before me, who better than me?”

New Cowboy Basketball Head

Coach Steve Lutz was introduced April 4th by Director of Athletics

Chad Weiberg and OSU System

President Kayse Shrum. A rising star under Creighton's Greg McDermott and Purdue's Matt Painter, Lutz is o to a successful start to his own head coaching career with NCAA tournament appearances in each of his first three seasons. In rapid rebuilds at Western Kentucky (2023-24) and Texas A&M Corpus Christi (2021-23), the 51-year-old has posted a combined 69-35 record, including a perfect 8-0 mark in conference tournament play.

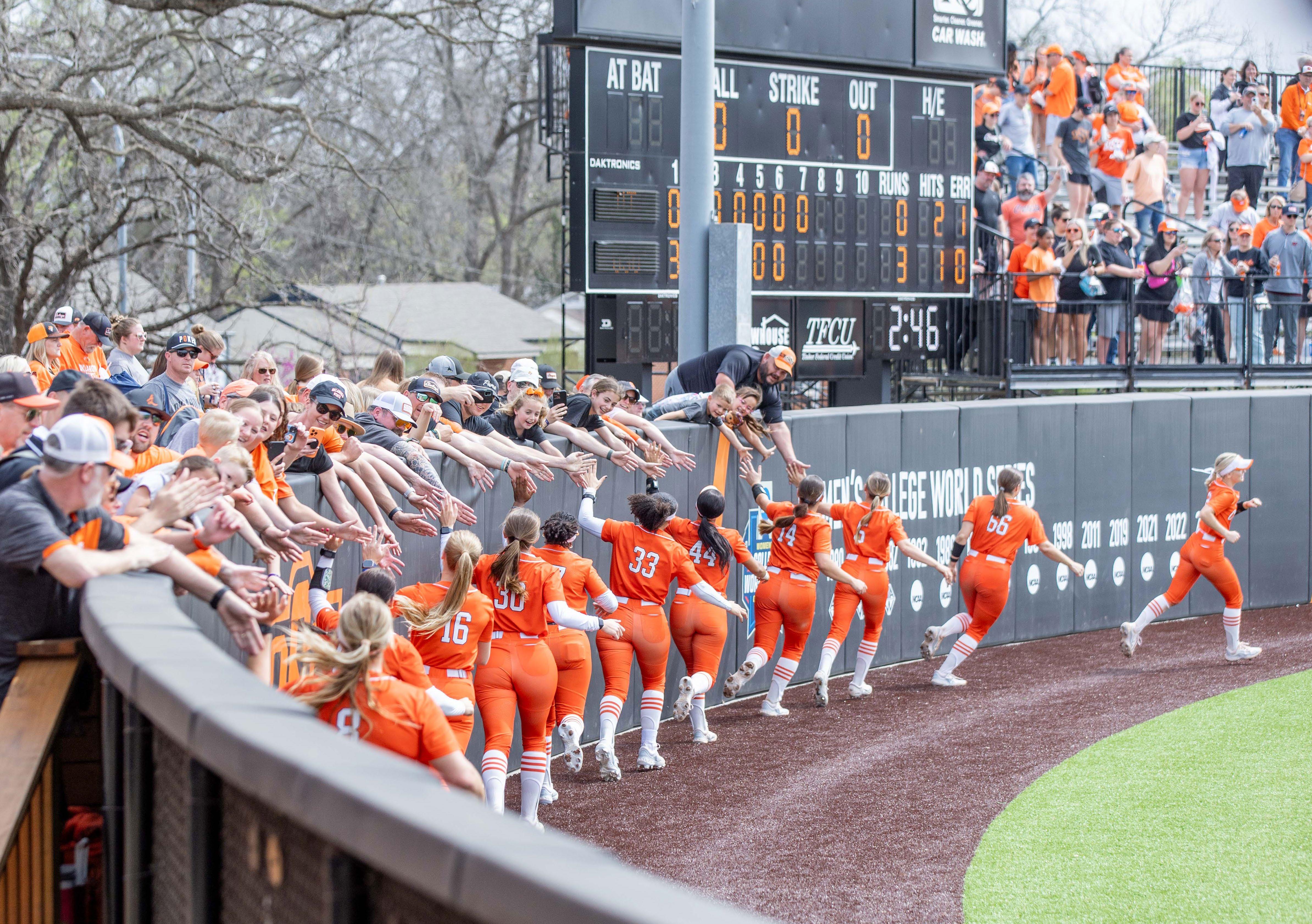

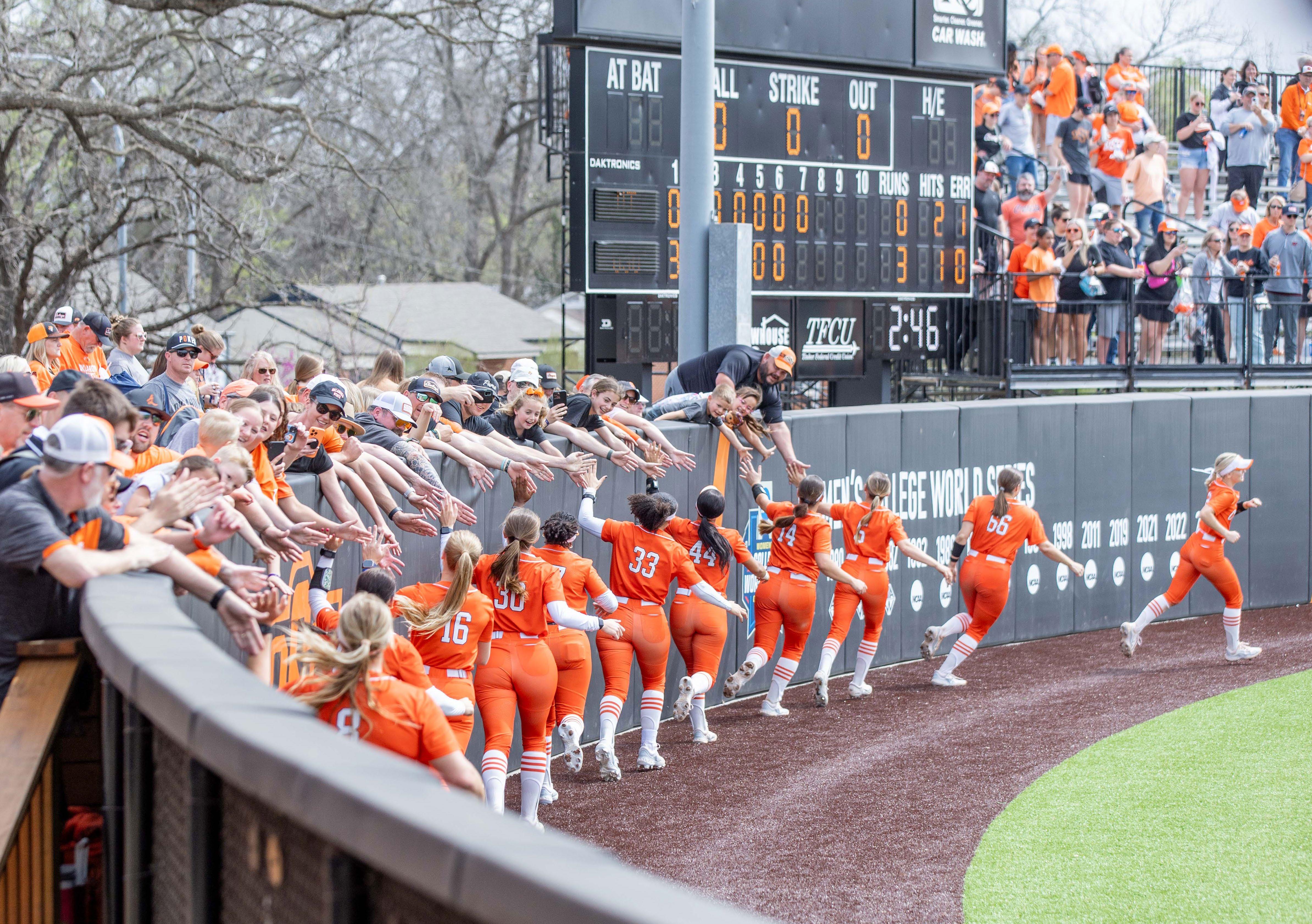

OSU softball players take a lap around the warning track to thank a record-number of Cowgirl fans and celebrate a 2-1 series victory over No. 2 Texas. O cial attendance for the game on Sunday, March 30, was 1,757, marking the largest crowd in Cowgirl Stadium history. Coach Kenny Gajewski's top-5 squad used a combination of outstanding pitching, solid defense and timely hitting to knock o the Longhorns in a crucial Big 12 Conference battle.

story by photos by Jacob Unruh

story by photos by Jacob Unruh

Tosha Martin could not come up with a di erent solution.

As the mom of four boys, she was often more referee than parent. Wrestling matches and fights broke out. Constant one-upmanship.

So, she bought four pairs of boxing gloves, a set for each Martin brother. She hung a punching bag in the garage.

“She got tired of us fighting so much, and she couldn’t stop us from fighting,” said Nickolas (Nick) Martin, the youngest of the four.

Still, the punching bag often hung undisturbed.

Instead, the front yard of their Texarkana, Texas, home became a boxing ring. So did the backyard. Really, anywhere boys could be boys

And the neighborhood kids joined in. Boxing tournaments ensued.

Tosha had ground rules to prevent injuries. But there were punches to the face. Even the youngest brother refused to shy from the fights despite being just 7 or 8.

“That definitely instilled some things in me,” Nick said.

Toughness. Brotherhood. Competitiveness. Composure.

Each a specific strand of DNA required to become a dominant football player

“It molded me,” Nick said. “When somebody hits you in the face, you ain’t bowing down. You hit ’em back. I think the area where we grew up in and how we all had that tough-minded, lay-it-all-on-the-line type of mindset, I think that really shows up in football, definitely, because it’s such a violent sport.”

The hard-knock upbringing in East Texas put Martin on a path to college football stardom. After a breakout season for OSU, there is not a more productive linebacker in the country entering the 2024 season.

Martin’s 140 tackles led the Big 12 and ranked seventh nationally. The redshirt sophomore’s total was the sixth most by an OSU player in a single season. It was the most tackles in a season by a Cowboy in nearly four decades.

Martin also had six sacks, 16 tackles for loss, a forced fumble, a fumble recovery and two interceptions, earning All-Big 12 first team honors.

“He’s an old-school player,” OSU head coach Mike Gundy said. “He’s an East Texas guy. He likes to play football. He doesn’t care about all of the notoriety, and he’s tough and he’s reckless with his body. That’s a rare combination in today’s players. You don’t see that much.

“He doesn’t worry about protecting his body, and he’s humble and he loves to play football.”

But to understand Martin’s rapid ascension to stardom, discovering what makes him tick is crucial.

“We’re all just amateur players playing the game we love trying to get to the highest level and play football for as long as we can,” Martin said. “Humble yourself so God ain’t gotta humble you. I think that’s the main objective.”

Nick Martin initially feared being tackled on a football field.

He was timid but fast, even for a 5-year-old. Catching him was rare. That certainly helped the apprehension of being hit.

“He was always wild, like buck wild,” said Chauncey Martin, the third of the four brothers. “He had a motor.”

Then a running back, Nick gradually found comfort on the football field. Two of his older brothers played — with one, Ryan, focusing on basketball — including Chauncey. Nick wanted to be like them. He started to love the sport.

By the time his mom o ered an opt-out after the season, he was completely hooked.

Aspirations of more than just pee-wee and backyard football quickly developed in the youngster’s mind.

“That’s when I realized this is something that I want to pursue forever,” Nick said. “I had Hall of Fame dreams back then. I’ve still got the same dreams. I fell in love with the game, and I wanted to do it at the highest level, so I started planning and blossoming.”

That meant no more hesitation.

The trio of brothers still playing football began training together. They developed sheets of plans for the summer workouts. They set goals. And they bonded.

“Those were moments that were priceless,” Nick said.

Still, he picked up more away from the organized practices and games. The streets of Texarkana provided the real lessons.

The Martin house was the epicenter of a lively neighborhood.

Nick and his brothers always had friends over. Tosha Martin bought extra snacks to provide to kids in the neighborhood, even if her sons were not around.

“It was a good neighborhood,” Nick said. “Just all of us were troublemakers. We were all into the same thing — just doing things we weren’t supposed to be doing. Kids being kids.”

Nick recalled being brought home by law enforcement after doing something he wasn’t supposed to do.

“Just stupid stu ,” Nick said. “Too much time on our hands, I would say.”

Tosha worked to divert that boredom.

The boxing gloves helped. Fight after fight. Punch after punch. Hard-knock lessons all around.

“It was a great asset to us as a family and me raising boys,” Tosha said. “So it was great.”

Nick was the youngest kid in the neighborhood, but he held his own.

“You definitely did get your beatings,” he said, “but you definitely celebrated the wins, though, for sure.”

And when there wasn’t boxing, Nick had baseball and karate. But nothing compared to football.

Nick and his neighborhood buddies constantly played.

Twenty-five to 30 kids often filled the Martins’ yard for a game. Windows were broken. Bushes were destroyed.

And even when it got too dark to see, the games moved to the concrete under the yellow glow of streetlights.

“It was the only place we had enough light to see,” Nick said. “It would be nighttime in the summer, and we’d be out there playing tackle, full-on live football in the middle of the streets.

“You definitely get your battle scars.”

Though it sounds dangerous, there were rules.

No tackling on the concrete. If that happened — and it did — a fight often broke out. But if a player got too close to the edge of the street, it was a free-for-all scenario.

“We just kept playing after that just like it was nothing,” Chauncey said. “It was sideline killing in the streets, and in the grass, everybody gets killed.”

Chauncey, though, had a soft spot for his little brother. He and his friends often let a young Nick — three years younger — free for a touchdown or big play. A missed tackle on purpose was common.

“I feel like it gave him that courage to believe,” Chauncey said. “Just involve him and build that courage. If you have courage and belief in yourself, I feel like you’re capable of anything.”

By the time Nick arrived at Pleasant Grove High School, it would not be long until he proved his brother’s feelings.

The words dug into the soul of Nick Martin as he entered high school.

“You’re Chauncey’s little brother.” Ouch.

“You had just taken his eye lashes o ,” Tosha said. “That’s the kind of pain you inflicted upon him. He did not like that at all.”

Chauncey was a senior running back at Pleasant Grove High School, well on his way to a college football career. He was a star.

Nick was a freshman stuck on the junior varsity roster as his older brother and teammates won a state championship.

That was only motivation.

Nick wanted his own ring. He was determined to make people know his own name. They would know who he was before too long.

There was no chance he would be just “Chauncey’s little brother” forever.

Nick changed his diet and hit the weight room. As he got faster and stronger, he exploded on the field as a running back and linebacker. As a sophomore, he totaled 128 tackles and 6.5 sacks as Pleasant Grove returned to the state title game. After the season, he ran a 4.5-second 40-yard dash at the University of Memphis’ mega camp. Later, Texas-San Antonio o ered him a scholarship.

That was the first step.

“That was the moment I realized this is really happening,” Nick said. “I knew what type of skills I had and abilities I had. But it was just all what I believed, and seeing that somebody else believed in me, that really gave me a lot of confidence.”

The next step was harder.

Nick missed most of his junior season with a knee injury. And recruiters struggled with his height. He wasn’t quite fast enough to be a running back. At 6-feet, questions mounted if he was even big enough to be a linebacker.

But Nick could hit with a devastating force.

“People are so stuck in what the standard was,” said Chauncey, who is 5-10. “Standards have to change if people want to grow and be better and experience new opportunities.

“If Nick knows people are talking about his height, that just makes him go harder. With that mindset, that’s why he’s unstoppable.”

Even with the questions, Nick still had the attention of several Power Five schools. With Pleasant Grove being a recruiting hotbed, Kansas, Arkansas, Texas Tech and Kansas State along with others o ered over the next year, even with the COVID-19 pandemic pausing recruiting.

By the time his senior season started, he was a di erent player.

Purely a linebacker, he was unleashing blow after blow to opponents. A local media member dubbed him “The Hit Stick,” a reference to a popular control in “Madden NFL” video games.

Nick’s hits were so powerful and frequent that he injured at least two opponents, sending one to the hospital in an ambulance.

“He was just laying the hat, man,” Nick’ father, Michael, said. “They were legal hits. He was just knocking them out. I mean, folks dreaded getting hit by Nick in high school.”

Pleasant Grove coach Josh Gibson would not allow Nick to hit his teammates during practices.

It was understandable. But it still bothered Nick.

“I was coming with vicious intent,” he said. “I had no other speed. It was always full tilt. I didn’t know how to not hit people. I couldn’t really hit much in practice.

“It was annoying because I was just trying to get some work in. But I get it. I’m over here hurting people. I gotta chill.”

That viciousness is what caught the attention of Gundy and OSU defensive coordinator Jim Knowles

They loved the old-school style. Harness the recklessness, and there’s something unique there.

So, the Cowboys o ered in September 2020. By the next month, they were in the final three alongside Texas Tech and Kansas State. Then they were the winners, even though Nick had never stepped foot on campus in Stillwater due to NCAA recruiting restrictions during the pandemic. Everything was through video. That, and talking with people he knew familiar with Stillwater, was enough to win him over.

“They were telling me that it was like that feel of Texarkana, where it’s nothing but football,” Nick said. “You ain’t got many distractions. Right then I knew I wanted to come here

“It’s small-town vibe where there’s nothing but football to do. And that’s what I’m all about, and that’s what I really like.”

Ollie Gordon II held his hand to his face like he was holding a microphone. He had questions for Nick Martin.

“How do you feel about the nickname ‘Missile?’” Gordon asked Martin.

Martin, fresh o a 12-tackle, one-sack performance in a 45-13 rout of Cincinnati last season, sat in the chair and smiled.

Then he answered.

“I like it,” he said before he tried to ask Gordon a question. But Gordon was not having it.

“Why do they call you ‘The Missile,’ sir?” Gordon said.

Martin hesitated.

“Because I run fast and hit,” he said.

Correct. But still not a satisfactory answer for the Cowboys’ o ensive superstar. Gordon had a better reason.

“You blink, and he’s at a di erent spot in the field in about 0.1 seconds,” Gordon said before cutting from the interview room.

Just like that, Martin had arrived after waiting his turn for two seasons with the Cowboys.

He redshirted as a freshman while he watched and studied Malcolm Rodriguez and Devin Harper in 2021. OSU made the Big 12 championship game and won the Fiesta Bowl. Martin was primarily a special teams contributor in 2022.

In the o season, Martin dedicated himself even more to the game.

First-year defensive coordinator Bryan Nardo often spent late nights at the o ce since his family had yet to move to Stillwater. It was common to see Martin in the linebacker room studying film of Nardo’s 3-3-5 defense at Division II Gannon. Before long, they were studying together throughout spring and fall workouts.

And Martin was quickly adapting to the new defense. By the end of spring, he was correcting his own mistakes.

“That’s a pretty special quality to have in a player,” Nardo said. “That was my first impression of him. He’s got something about him that’s di erent in a good way.”

Still, Martin wasn’t even expected to be a starter last season. Tulsa transfer Justin Wright was brought in for that purpose. But Wright su ered an injury and the door opened.

Martin never slowed down.

“He’s everywhere on the field,” defensive tackle Collin Clay said. “I’ve never seen many linebackers fly around like that in my life.”

Martin put his name in OSU’s record book. His 140 total tackles were the most since 1984. He led the Big 12 in four categories — solo tackles (83), total tackles, total tackles per game (10.0) and sacks among linebackers (6.0). He was top 10 nationally in solo tackles, total tackles and solo tackles per game (5.9).

Early in the season, Gundy shot down any comparison to Rodriguez. By the end, Gundy was talking about both in the same breath.

“We talked about Malcolm Rodriguez and nobody ever being able to do anything like it again, but he’s got Malcolm Rodriguez numbers,” Gundy said in December. “He was just a guy, and then he’s thrust into that role, and he’s taken o . We felt like he was going to be that kind of player. Well, I didn’t think he could do it this year. I didn’t think he was ready, but obviously he was.”

And not long into the season, Nardo saw Martin in a vital role for the defense, not just the face of the unit, either.

Martin became the defense’s sniper, a position Nardo found success with at Gannon. Martin’s lightning closing speed and ferociousness were keys.

“He’s not rushing (the quarterback) until he’s rushing,” Nardo said. “Having a guy like that, whoa, it makes life pretty fun.

“The last player I had run this position and this technique, he had seven sacks. I remember watching and

saying Nick was our Power Five-level version. Nick just got better and better and better.”

Now, Martin is no longer a secret, at least to those around the Big 12.

Naturally, most of the national attention will go to Gordon, a Heisman Trophy contender and the reigning Doak Walker Award winner as the nation’s top running back. But there should be no overlooking Martin.

He’s the face of the Cowboys’ defense. There are few players more productive around the country.

He’s proven that his size is not a hindrance. He’s added weight this o season. He’s checked in at 225 pounds, nearly 10 pounds above his playing weight.

“People have this big idea that all linebackers gotta be 6-2 and 250 and big burly guys,” Martin said. “But, in all reality if you can play football, you can play ball. If you understand leverage and if you understand how to use your frame and speed and acceleration, then you can really dominate at any level

“My weight was never really something that I worried about. I knew that it was going to come eventually, that no matter what weight I was at, I was going to play my game. I just honed in and allowed God to work. I think it’s paid o .”

From afar, Martin’s family watches with a rare giddiness. Tosha Martin says she’s way past cloud nine. Michael Martin is just amazed at his youngest son.

And Chauncey has had to adjust to a new world.

He recently helped Harding University win the Division II national championship as a running back. But he’s got a new nickname of his own.

In 2022, people started to recognize Chauncey for other reasons.

“Oh, you’re Nick’s brother,” people often say.

That caught Chauncey o guard.

Then he realized times had changed for the better.

“He’s doing big things,” Chauncey said, “so he deserves to be the athlete of the family. He’s put in the work. He’s shown that he’s the one.

“When I first started seeing (him play), it was sort of shocking because that’s your little brother. He’s out there making plays on the biggest level in college. The belief is crazy from the fam. We love to see him make plays. The joy he gets from it creates joy in us.”

Cowboys DeJuana McArthur, Brian Musau, Mehdi Yanouri and Ryan Schoppe won the Distance Medley Relay at the 2024 NCAA Indoor Track & Field Championships held March 8 in Boston. It was the secondstraight NCAA title for head coach Dave Smith's DMR squad, with Schoppe running the anchor leg of both. The Cowboy quartet crossed the line with a time of 9:25.24 in the event that features relay legs of 1200, 400, 800 and 1600 meters. The OSU men finished the national meet in a tie for 7th place, while the Cowgirls also earned a top-10 place, finishing tied for 8th as a team.

Cowgirl Track and Field's Sara Byers converses with Cowboy Football's Alan Bowman and wide receiver Leon Johnson IlI at the student-athlete Etiquette Dinner. The event is hosted by OSU's Student-Athlete Leadership and Professional Development department to impart basic dinner and networking etiquette that will be beneficial once they leave Oklahoma State. Attendees (including athletic administration, professors, deans, donors and community partners, such as Simmons Bank) enjoy interacting and learning about studentathletes outside their sport.

STORY BY

PHOTOS BY CLAY BILLMAN

STORY BY

PHOTOS BY CLAY BILLMAN

Banking, Bruce Benbrook says, is in his blood.

“My whole adult life, basically — except for the four years I was in school at OSU — I worked at a bank.”

As chairman and CEO of The Stock Exchange Bank in Woodward, Benbrook is a third-generation banker. He was born into the business.

In 1912, shortly after Arkansas natives Asa Monroe “A.M.” Benbrook and Mayme Garner (Bruce’s paternal grandparents) were married, the newlyweds packed up and moved to northwest Oklahoma for a fresh start.

A.M. landed a job as a cashier at The Stock Exchange Bank of Fargo. Known as Oleta Township before statehood, the small farming and ranching community in eastern Ellis County had a little over 300 residents at the time — thanks in part to military roads connecting Fort Supply and Fort Elliott, along with a stop on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, the country town also boasted three churches, a public school, local newspaper, three general stores, two milling companies and even a telephone connection.

Within a decade, A.M. Benbrook had become president of The Stock Exchange Bank and shepherded the bank through the Roaring Twenties — and the subsequent Great Depression and Dust Bowl of the ’30s. In 1939, the bank merged with Sharon State Bank and moved 15 miles up State Highway 15 to the “big town” of Woodward (pop. 5,400 at the time).

Meanwhile, the couple’s two sons (Temple and Douglas) both attended Oklahoma A&M and studied business, returning home to work for their father. Temple took the reins of The Stock Exchange Bank from his father in 1959 and built the financial institution into a staple of the community.

Along with banking, orange also runs in the Benbrook bloodline. The brothers’ fondness for their alma mater forged a family link between Stillwater and Woodward that spans 140 miles of blacktop and three generations.

“When I was three years old, my dad (Temple Benbrook) brought me to my first football game at Lewis Field, and after that I was hooked!”

Temple (OAMC class of ’36) served on the Alumni Association board of directors when Bruce was a young boy.

“They had the board meetings on game days, and they would meet at the Student Union in the morning with the game in the afternoon,” Bruce recalls. “My dad would bring me to the meetings. I wasn’t allowed to run around, so I would sit in the corner for two hours and be quiet and behave, because I knew I got to go to the football game later. After the meeting,

we’d have lunch downstairs in the old cafeteria, and then he’d take me to the football game.”

He says his mother, Mary, would often recount the story of Bruce’s verbal commitment to become a Cowboy.

“My mother picked me up from kindergarten one day, and the teacher told my mother that I wanted to take a vote among the other five-year-olds: ‘Where was everybody going to college?’ … I announced that I was going to Oklahoma State. My mom swore that’s a true story.

“So I’ve been on board for quite a few years.”

In 1972, Benbrook graduated from Woodward High School (home of the Boomers, as well as the legendary “Blond Bomber” Bob Fenimore). As promised, he packed his bags for OSU that fall.

By all accounts, Bruce thrived on campus, active in the Sigma Nu fraternity and serving as SGA president his senior year. Earning a bachelor’s degree in finance from the College of Business, he was named the Outstanding Male Graduate in 1976.

At the same time, Bruce’s former high school sweetheart (Sheryl Stevens) was also in Stillwater.

“I think we went to our first dance together in the eighth grade,” Sheryl recalls. “We dated o and on through high school, and early-on in college, and then kind of went our separate ways for a time.”

(More on that later.)

Stevens was an accomplished student-athlete, and somewhat of a pioneer in her hometown and at OSU.

“From the time I was a kid in the 7th grade, we actually gathered up our courage and petitioned the administration to have girls’ basketball in Woodward, because we didn’t have any girls’ sports,” Sheryl recalls. “They kind of laughed at us. I remember being crushed by that.”

Eventually, the Woodward school board was compelled to add girls’ sports by Stevens’ junior year. The blonde Boomer was finally able to compete.

“My older sister didn’t have an opportunity to play,” she says. “Finally, when Title IX was on the horizon, I got to run two years of track and play one year of basketball in high school — but even then we had to play 6-on-6.”

In 1972, Title IX of the Civil Rights Act was signed into law, requiring equal opportunities for women in federally funded institutions.

“We were Title IX beneficiaries, so we were really grateful,” she says. “It was the first of baby steps for women’s programs.”

At Oklahoma State, Sheryl joined the Cowgirl track and field team and played basketball for one year. She also relished intramural competition, whether it was badminton, gymnastics or flag football.

“I just had a really good time doing those kind of things, and OSU o ered those opportunities. I was really grateful to have them.”

To call Stevens and her Cowgirl teammates trailblazers is no stretch.

“I think that group of women feel like they were knocking down the doors,” she says proudly. “We weren’t scholarship athletes, but we were representing the school. I’m grateful for OSU giving us that opportunity. It was an opportunity that the people before us didn’t have.”

Bruce and Sheryl are five-star Cowboy VIPs, and are familiar faces to many at Boone Pickens Stadium, Gallagher-Iba Arena and now O’Brate Stadium.

“OSU is my happy place,” Bruce says.

Often, the Benbrooks will find themselves part of caravan of Cowboys making the round trip to Stillwater on gamedays.

“We’re really out there in rural Oklahoma,” Bruce says. “Over and back it’s a 300-mile deal. I always admire the number of people who come to an OSU football game and drive back to Woodward and Shattuck and Bu alo, and some even go to Spearman or Perryton (Texas) … There’ll be a line of cars heading northwest and getting in at 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning — but they’ll do it. Because, just like my family, they love this university.”

Sheryl competed for coach Bernie O’Connell in the 880-yard dash, and qualified for the 1975 Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) national championships, along with teammates Suzy (Phelan) Rojas and Suzie (Winingham) Byrd. The trio piled in a car to drive from Stillwater to Corvallis, Ore., for the meet, where Winingham became OSU’s first female All-American.

“It was a lot of fun and good memories … I ran with some really good people there,” Sheryl adds, also mentioning Stillwater native Marilyn (Linsenmeyer) Wynia, who finished fourth in the Olympic Trials in the pentathlon.

“Sheryl was a very good athlete,” Bruce says. “For two consecutive years, she was voted the outstanding female on the OSU track team. She has all the athletic ability in the family. I was the 10th player on any real basketball team.”

While Sheryl was running in counter-clockwise circles, Bruce says attending OSU sporting events were a big part of his college days.

“I grew up in a community that didn’t have wrestling, and it was a lot of fun to come to those sold-out wrestling matches. To this day, I still don’t understand all the rules, but I love it.”

Benbrook recalls basketball games at Gallagher Hall under coaches Sam Aubrey and Guy Strong; baseball with Chet Bryan; football at Lewis Field in the Jim Stanley era.

“You know, almost every time there was an athletic event, I tried to be there. I didn’t miss.”

That’s true today, as well, despite living two-and-a-half hours away.

After earning a degree in Health, Physical Education and Recreation (HPER), Stevens attended law school at the University of Oklahoma. Upon passing the bar, she worked first with an insurance defense firm and later for an oil and gas firm (both in OKC) before returning to Woodward.

Despite his DNA, Bruce says he didn’t set out to make a career in banking.

“I had never even worked in the bank — ever,” he says. “Not growing up, not as a teller, not working a summer job. Never. Not until August 1st of 1977.”

A few months after graduation, Bruce took a job at First National Bank and Trust Company in downtown Oklahoma City, still unsure of where it might take him.

Back in Woodward, however, his father’s health began to decline.

“I told my dad I was ready to come home if he needed me.”

After a year in OKC, it was time.

Bruce joined The Stock Exchange Bank as an assistant cashier. He spent three years learning the ropes before his father passed away in 1981. At age 27, Bruce found himself behind the president’s desk.

“The opportunity to spend time and learn from my dad was priceless,” Bruce says. “Certainly, the first five years of running the bank — my goodness, did I make mistakes! I had to kind of grow up in a hurry, but I got through it somehow. My dad was probably looking down and guiding me.”

Bruce says a number of industry colleagues were there for him during those early days.

“When my father died, I had numerous bankers reach out and ask, ‘What can I do to help? If you need anything call me’ — without hesitation. People were so gracious to step up and o er their assistance. You never forget that.”

Around the same time, Sheryl and Bruce reconnected and rekindled the old flame. The 18-year, on-again, o -again courtship finally culminated in marriage in 1984. They will celebrate their 40th anniversary this December.

“We literally had our first date at 13 and got married at 31,” Bruce says.

“We kind of grew up a little bit,” Sheryl adds, recalling their relationship as well as professional responsibilities at the time. “We lost his dad a little earlier than anybody would have liked. It threw him into the banking industry in a pretty big position with an awful lot of people counting on him a little earlier than he would have liked, but he did a great job.”

For the banking industry, the decade of the 1980s was challenging to say the least.

“It was a crazy time,” Bruce says. “When Penn Square Bank failed, things were di cult. But you go through economic cycles. That’s just inevitable. Ups and downs are going to happen. To be a successful, long-term banker, you’ve

got to be able to ride through those. It’s part of the business.”

“I’m real proud of him for what he has done, because he took the bank from where it was and grew it,” Sheryl says. “He won’t brag on himself, but he was the youngest president of the OBA (Oklahoma Bankers Association) at age 37.”

A daughter, Rachel, came along in 1990. Julia joined the family four years later. The sisters were raised to be Cowgirls from day one.

“Our kids grew up just being packed in the car and going over to Stillwater for OSU events and family gatherings,” Sheryl says. “I don’t know that they even knew they had a choice when it came to school.”

“I definitely remember going to OSU games all the time growing up,” Rachel Benbrook says. “It was so much fun! And you know, every Bedlam my dad would put out a special ‘BEAT OU’ sign at the house. So I just grew up constantly involved with OSU and being in Stillwater and going to so many di erent sporting events. One of my earliest memories is going to the Final Four in Seattle when I was about four years old. I still remember how much fun that was.

Bruce recalls the time when he and Sheryl helped the group collect trash after Bedlam at BPS.

“Every game they would pick up all the trash and the bottles,” Bruce says. “Rachel was in charge of that, so I always wanted to be involved. Those kids would work ’til 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning. It was amazing. They put out these green sacks at the tailgates, and they’d go around and sort the recyclables. My job was to empty all the liquor bottles.

“I’ll never forget this,” he adds. “I think I made it to about 1:30 a.m. — I don’t know what time they got done — but we get in the car, and my wife says, ‘You better drive very carefully.’ I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Your shoes reek of alcohol!’ Apparently, I had been pouring booze all over my feet.”

(Bruce punctuates the story with hearty laughter, as he often does.)

Soon after Rachel graduated, Julia came to campus as a freshman. The dedicated dancer made the OSU Pom squad, which provided numerous spectator opportunities for her proud parents. She also was named Miss OSU Outstanding Senior in the class of 2017.

Julia graduated with a bachelor’s in multimedia journalism and attended Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, earning a master’s specializing in politics, policy and foreign a airs.

These days, Julia Baden (she married fellow OSU alum Zach Baden last year) can be seen covering the White House, Congress and the 2024 presidential election as a CNN Newsource national correspondent Washington, D.C.

“OSU has always been a part of the Benbrook family identity,” Julia says. “From pretty early on, we were wearing a lot of orange, that’s for sure. My very first pair of little Nike shoes with the Swoosh on them were a baby gift from Eddie Sutton. We still have those.”

With Julia performing with the poms, the Benbrooks rarely missed a game.

“That meant my dad got to go do his favorite thing in the world and support his daughter at the same time,” Julia says. “I can’t really remember a time that they weren’t sitting in the audience. We had a lot of sporting events back-to-back — football, basketball, wrestling — and they would be there.”

“Both of my parents have always been the lead-by-example type,” Julia says. “They’ve always tried to put others before themselves. My sister and I have had the chance to watch them do that at OSU and in the Woodward community.”

“My mom has been a role model for me and so many other young women in our community,” Rachel says. “And my dad is just the happiest, most supportive person. He’s always showing up for di erent community groups, looking to see who needs help and trying to fill that void for an organization that needs it.”

“The bank in a small town has a larger responsibility than just taking deposits and making loans,” her father says. “I think you need to be a leader in the community. You have to invest back. My number one investment objective outside the bank is education.”

The Benbrooks are Top 150 all-time donors to OSU Athletics, but their history of giving spans a myriad of philanthropic endeavors, including the Spears School of Business, “Women for OSU” symposium, McKnight Center, Ferguson College of Agriculture, Alumni Association, President’s Leadership Council, OSU Spirit group and many more.

“My dad really loves being a part of the OSU family and has tried to give back in every way he can,” Julia says. “When you hear the phrase ‘Loyal and True,’ that perfectly describes how he sees being an OSU fan.”

“We love the opportunity to support this university in any way possible,” Bruce says, “whether it be athletics, academics or the arts. We’re making investments in the future, and we really are investing in our young people.”

It’s an investment that has paid countless dividends.

“We enjoy going to games together, seeing friends that we’ve developed over the years … plus our daughters both attended school here. The Benbrook family just has a great relationship with OSU. We love this place.”

You can take that to the bank.

Cowboy Daton Fix salutes the crowd after winning an unprecedented fifth conference title at the Big 12 Wrestling Championships, held in Tulsa March 9-10. Competing at 133 pounds, the native of Sand Springs, Okla., capped o his final season in an orange singlet as a five-time All-American and fourtime NCAA runner-up. His 123-7 mark ranks 10th in school history, and Fix never lost a match while competing at home in GallagherIba Arena.

Cowgirl Basketball's Stailee Heard donned her traditional Seneca-Cayuga fancy shawl for Nike N7 Youth Movement Day, hosted by OSU's Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC).

The annual event brings Native American students (3rd-8th grade) from across the state of Oklahoma to participate in various activities, including traditional games, with the goal of promoting healthy, active lifestyles within the Native American community.

STORY BY

STORY BY

When athletic director Chad Weiberg assumed his duties, it was July 1, 2021. About 48 hours later, realignment hit the Big 12 with breaking news that Texas and Oklahoma would be departing for the Southeastern Conference. Since that time, the fate of the Big 12 Conference, and realignment in general, has dominated much of the time of the league’s presidents and athletic directors. On July 1, 2024, the once-endangered league will swell to an all-time high of 16 teams and is on solid footing with the addition of four Pac-12 Conference expatriates in Arizona, Arizona State, Colorado and Utah. Weiberg recently discussed with POSSE Magazine the challenges and triumphs of the Big 12 sprinting from 10 to 16 teams in three years.

POSSE: Talk about the assimilation process of joining ranks with the new members from the Pac-12. How is the tone and attitude of the group as a whole?

Weiberg: “It has been very positive. Obviously, we had the four new members in BYU, Cincinnati, Houston and UCF come into the conference this year. Although they won’t o cially be full voting members until July 1, Arizona, Arizona State, Colorado and Utah have been attending our meetings to discuss the future of the conference. The devil is always in the details, and there are a lot of details to work out, but they are a good fit and great addition to add to the strength of the conference.”

POSSE: What are the biggest challenges facing the new Big 12 in regard to operations?

Weiberg: “Scheduling has probably been the largest logistical or operational issue. Obviously, we have gone from a 10-team league where we were able to play a complete round-robin format in every sport to a 16-team league where there will be an unbalanced schedule in every sport. The geographic footprint of the conference has also grown significantly, so how do we manage that in our scheduling across the various sports? The larger number of teams also impacts how conference championship events will be scheduled in most sports, including the number of teams that qualify and the number of days it takes to complete the tournament or championship.”

POSSE: Moreso than just about any other conference, or any previous iteration of the Big 12, this seems to be a conference of peers, regarding budget, success, championships, etc. Good thing or bad thing?

Weiberg: “The Big 12 will be the most exciting conference to watch because just about anything can happen on any given

day, almost regardless of the sport. It will also continue to drive home the importance of our fans and supporters. Because there will be so much parity, the importance of home field or home court advantages that are created by our student section and our fans will be vitally important Likewise, our alumni and fans continuing to support our student-athletes through donations to the POSSE and supporting NIL will start to define the di erence.”

POSSE: With the consolidation into a Power 4, and the expansion of the College Football Playo , what does the “bowl season” look like going forward.

Weiberg: “For the teams that make the new 12-team playo , it will look very di erent. If you’re playing in the first round, you’ll either host or go to another campus. If you are eliminated, your season ends then. Each year several schools will have great seasons that end before the holidays. Quarterfinals and beyond will be at traditional bowl locations and will be good experiences but will be in condensed time frames because the winners will be moving on to another game. For teams that don’t make the 12-team CFP, there will continue to be great bowl experiences. Bowl a liations could evolve over time with conference changes

and consolidation, and I know Commissioner (Brett) Yormark and the Big 12 sta is working hard to continue to have strong bowl partnerships for our league.”

POSSE: You now have a future with the very real possibility of a CFP game in Stillwater in December. What are the potential ramifications?

Weiberg: “I’ve had the opportunity to serve on the College Football Playo sub-committee that has been tasked with helping prepare for on-campus playo games. The things we have been working through are identifying and holding room blocks and meeting rooms at potential hotels for visiting teams during the holiday season, practice facilities for visiting teams, number of tickets allotted to visiting fans, accommodating the families of the visiting team’s student-athletes, visiting bands and the like. Much of it is similar to what we already do for visiting teams, but this will happen in a very tight time frame between the announcement of the 12 playo teams, including announcing hosts, and the actual kicko . So, there are a lot of logistics that have to be worked out ahead of time at every school in case you are one of the hosts in the first round or one of the four that are traveling.”

The Big 12 will be the most exciting conference to watch because just about anything can happen.

— CHAD WEIBERG

POSSE: What have the discussions been like regarding future football schedules?

Weiberg: “As a conference, we’ve had conversations regarding football scheduling to make sure we are giving multiple teams in the Big 12 the best possible chance to get into the 12-team CFP. Some of that includes the nine-game conference schedule, but it also includes how you schedule for the non-conference games. We have a very competitive non-conference schedule for several years into the future, but we’ll continue to monitor any changes that might dictate adjustments that need to be made.”

POSSE: For the first time ever, Oklahoma State has two Friday night games in a season, at BYU and at Colorado on Thanksgiving weekend. Is this a glimpse into the future when the new conference television contract kicks in for 2025?

Weiberg: “In essence, it is. As a league, we will have obligations with our television partners to help fill their non-Saturday game windows. I look at it as a tremendous exposure opportunity. The college football audience is

pulled in multiple directions on weekends. Marquee games on a Thursday or a Friday will generate very good ratings and lots of eyeballs for the Big 12 . Having said that, we all know what Saturdays on our campuses mean to our fans and alumni and to our campus partners. There is also a recruiting element to Saturday games that cannot be duplicated on a weeknight. As a university and a league, we will be very diligent in assuring no one program is disadvantaged when it comes to weeknight contests.”

POSSE: What does the geographical expansion of the Big 12 mean for the postseason conference championships?

Weiberg: “As I mentioned earlier, we are aware and sensitive to the geographical footprint and that will be a consideration for conference championships. But there are other important components to consider, as well, including support of the host community. We won’t move championships or anchor championships just for the sake of moving or because we’ve always been there. We will continue to be strategic in placing our championships in the best possible locations for the conference, the student-athletes and the fans.”

POSSE: Beginning July 1, the Big 12 will stretch from the Arizona desert to the coal mining hills of West Virginia and from Florida to Utah. But the heart of the league is still I-35 with Iowa State, the Kansas schools, OSU, TCU and Baylor (along with Tech). Talk about marrying the di erent entities.

Weiberg: “Well, the conference really has already grown past the historical I-35 corridor with the additions of UCF, BYU and Cincinnati this year. Adding the so-called Four Corner schools in Arizona, Arizona State, Colorado and Utah will fill in some of the geographic spread, which in some ways for some sports, will help us take advantage of scheduling multiple schools in the region during a single road trip. Other than logistical things like that, I think it will be exciting for the fans to visit new places or revisit places , like Colorado, where we haven’t been in a long time. I know I’ve already heard from a lot of our fans that are looking forward to road trips with football this fall to Provo and Boulder. And I’ve also heard, for example, that a lot of Utah fans are looking forward to traveling to Stillwater.”

POSSE: What are your impressions of the new Big 12 schools that are concluding their first season in the league?

Weiberg: “We were one of two schools this year, with West Virginia being the other, that got to play all four of the new schools this football season. What we saw in each of those is they are very excited about being part of the Big 12 Conference. They are taking advantage of the additional resources and capitalizing on the excitement the jump to a power conference is generating with their fans and donors. They are all good academic institutions, each of them have a larger enrollment than OSU, and they are building. Those of us who are legacy members of the Big 12, including Oklahoma State, have a head start on them in many ways, but we can’t be comfortable with that and certainly can’t rest. The saying that “if you are standing still, you’re falling behind” is as true now as it has ever been. We have to keep advancing and pushing forward , and I’m confident we will continue to do so.”

When OSU announced its scholarship endowment initiative, the athletic program was last in the Big 12. Now, more than halfway through the 10-year program, OSU leads the conference.

OSU awards 229 full scholarships to student-athletes each year at a cost of $4.5 million. Each dollar freed up through endowed scholarships goes back into our programs. Better equipment. Better facilities. Better support. Each dollar has a direct impact on the lives of our student-athletes.

This is the list of all the generous supporters who have helped to provide a bright Orange future.

They are our Honor Roll.

Baseball 10.25

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

Dennis and Karen Wing (2) | Hal Tompkins

Sandy Lee | Jennifer and Steven Grigsby

Mike Bode and Preston Carrier (2)

David and Julie Ronck

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Sally Graham Skaggs

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Bryant and Carla Co man

David and Grace Helmer | Jill Rooker

Martha Seabolt | Dr. Scott Anthony

John and Beverly Williams

Richard and Lawana Kunze

Equestrian 1.25

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

Baloo and Maribeth Subramaniam

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

David and Gina Dabney

Football 33.0

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

Bob and Kay Norris

Bryant and Carla Co man /

The Merkel Foundation

David LeNorman | Dennis and Karen Wing (2)

Dr. Mark and Beth Brewer

Ike and Marybeth Glass

Jack and Carol Corgan

Jim Click | John and Gail Shaw

Ken and Jimi Davidson | Leslie Dunavant

Mike and Kristen Gundy

Mike and Robbie Holder

Ron Stewart | Ross and Billie McKnight

Sandy Lee | Tom and Sandra Wilson

Wray and Julie Valentine

James and Mary Barnes

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Cindy Hughes | Donald Coplin

Doug Thompson | Ed and Helen Wallace

R. Kirk Whitman | Greg Casillas

Jim and Lynne Williams / John and Patti Brett

Mike and Judy Johnson | Sally Graham Skaggs

State Rangers | Tom Naugle | Nate Watson

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Al and Martha Strecker

Arthur “Andy” Johnson, Jr.

Arthur Couch | Barry and Roxanne Pollard

Bill and Ruth Starr | Brad and Leah Gungoll

Brian K. Pauling

Bridgecreek Investment Management LLC

Bryan Close | David and Cindy Waits

David and Gina Dabney | Dr. Berno Ebbesson

Cowgirl catcher Caroline Wang crushes a home run in the first-inning against Texas on March 30. Wang's three-run blast was the di erence in the game, as OSU blanked the Longhorns 3-0 to take the series.

PHOTO BRUCE WATERFIELDDr. Ron and Marilynn McAfee

Eddy and Deniece Ditzler | Flintco

Fred and Janice Gibson | Fred and Karen Hall

Howard Thill | James and LaVerna Cobb

Jerry and Lynda Baker | John P. Melot

Jerry and Rae Winchester

John S. Clark | Ken and Leitner Greiner

Kent and Margo Dunbar | Paul and Mona Pitts

Randall and Carol White | Shelli Osborn

Roger and Laura Demaree

Steve and Diane Tuttle

Tony and Finetta Banfield

General 1.25

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Terry and Martha Barker

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

David and Judy Powell

Kenneth and Susan Crouch

Sally Graham Skaggs

Graduate Athlete

0.75

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Bob and Joan Hert | Neal Seidle

Tom and Cheryl Hamilton

Men's Basketball

23.5

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

Baloo and Maribeth Subramaniam

A.J. and Susan Jacques

Bill and Marsha Barnes

Brett and Amy Jameson

Calvin and Linda Anthony

Chuck and Kim Watson

David and Julie Ronck (1.25)

Dennis and Karen Wing (2)

Douglas and Nickie Burns

Gri and Mindi Jones

James and Mary Barnes | Jim Vallion

Ken and Jimi Davidson

Kent and Margo Dunbar | KimRay Inc.

Sandy Lee | Mitch Jones Memorial

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

David and Julie Ronck

Dr. Mark and Susan Morrow

Jay and Connie Wiese | Sally Graham Skaggs

Stan Clark | Billy Wayne Travis

Holloman Family

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Dr. Scott and Lynne Anthony

Gary and Sue Homsey

Michael and Heather Grismore

Rick and Suzanne Maxwell

Robert and Sharon Keating

Steve and Suzie Crowder

Terry and Donna Tippens

Men's Golf 6.25

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

David and Julie Ronck

Dennis and Karen Wing

Jack and Carol Corgan

Genevieve A. Robinson

Baloo and Maribeth Subramaniam

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Simmons Bank

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Bob and Elizabeth Nickles

Garland and Penny Cupp

Richard and Joan Welborn

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Tom and Cheryl Hamilton

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Jim McDowell Men's

Men's Track 0.75

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Dr. Mark and Susan Morrow

Susan Anderson | Ken and Leitner Greiner

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Mary Jane and Brent Wooten

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

James and Mary Barnes

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Tom and Cheryl Hamilton

Richard Melot

Ann Dyer

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

Brad and Margie Schultz

Ken and Jimi Davidson

Mike Bode and Preston Carrier

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Baloo and Maribeth Subramaniam

Don and Mary McCall

John and Caroline Linehan

Calvin and Linda Anthony

Mike Bode and Preston Carrier

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Bill and Roberta Armstrong

Bill and Sally Cunningham

Donald Coplin | Jill Rooker

Richard and Linda Rodgers

Jo Hughes and Deborah J. Ernst

Richard Melot

Women’s Golf 3.0

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

Baloo and Maribeth Subramaniam

Genevieve A. Robinson

Louise Solheim

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

David and Julie Ronck | Dena Dills Nowotny

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Amy Weeks | Kent and Margo Dunbar

Women’s Tennis 0.5

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Jamie Maher

Richard Melot Wrestling 11.25

FULL SCHOLARSHIP

A.J. and Susan Jacques

Bruce and Nancy Smith

Chuck and Kim Watson

Lon and Jane Winton

OSU Wrestling – White Jacket Club / Gallagher Endowed Wrestling Scholarship

OSU Wrestling – White Jacket Club / Myron Roderick Endowed Wrestling Scholarship

OSU Wrestling – White Jacket Club / Ray Murphy Endowed Wrestling Scholarship

OSU Wrestling – White Jacket Club / Tommy Chesbro Endowed Wrestling Scholarship

The Cobb Family

HALF SCHOLARSHIP

Mike and Glynda Pollard

Mark and Lisa Snell

Bobby and Michelle Marandi

QUARTER SCHOLARSHIP

Danny and Dana Baze / Cory and Mindy Baze

Kyle and Debbie Hadwiger

John and Beverly Williams | R.K. Winters

To learn more about scholarship opportunities and how you may contribute, please contact:

Larry Reece (405-744-2824)

Matt Grantham (405-744-5938)

Daniel Hefl in (405-744-7301)

Shawn Taylor (405-744-3002)

The Cowgirl Equestrian team hoists the Big 12 trophy after defeating TCU, 10-9, to earn a fourth consecutive conference championship. The victory marks the 10th conference crown in program history for head coach Larry Sanchez Riley Hogan and Sydney North led the way for the Cowgirls, earning tournament Most Outstanding Performer honors in Fences and Flat, respectively, after going undefeated on the weekend in their events.

STORY BY

STORY BY

For the past eight years, Karen Hancock split time between distinct but overlapping worlds . She hopped from rowdy soccer sidelines to orderly administrative meetings, immersing herself in both environments.

Oklahoma State athletes learned valuable skills from her, and colleagues in athletic leadership — particularly fellow women — taught her new lessons. Hancock, 55, served as OSU’s Senior Woman Administrator while continuing as an assistant coach for the thriving soccer program she built. Skillfully handling this rare balancing act, Hancock didn’t want to step away from coaching until she had certainty about a career move. With the 2023 soccer season winding down, she knew.

“The timing felt right to just go ahead and say, ‘I’ve got a foot in both waters,’” Hancock said. “‘ It’s time to get into one pool or the other ,’ and I made the jump.”

In early February, OSU Athletics announced Hancock’s transition to full-time athletic administration, which brings a new title. She has stepped into the role of Senior Associate Athletic Director while retaining the SWA position. All around her, signs of change led to this personal shift. In the big picture, the ongoing metamorphosis of college sports intrigued her. Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) deals intersect with the transfer portal to create an environment where, more than ever before, athletic administrators need a clever combination of business savvy and sports knowledge.