Celebrating the 150 th

of universities land grant anniversary

1862

The Morrill Ac T

1890

okl AhoMA STATe UniverSiT y foUnded

1890s

oSU beginS AgricUlTUr Al reSeArch

ENGINEERING ENTREPRENEURSHIP

FOOD SAFETY

1900s

oSU’S bAcTeriology depArTMenT idenTifieS T yphoid gerM in locAl drinking wATer

NANOTECHNOLOGY VETERINARY MEDICINE MUSIC

AGRICULTURE

CHEMISTRY

HUMAN HEALTH

ZOOLOGY

ENERGY ART

Research, scholarship and creative activity at Oklahoma State University 2012

Burns Hargis, President

Stephen W.S. McKeever, Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer Vanguard is published annually by Oklahoma State University. It is produced by the Office of Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer.

Editor/Writer: Kelly Green, Art Director/Designer: Ross Maute, Photographers: Mandy Gross, Todd Johnson, Gary Lawson, Kevin McCroskey, Phil Shockley, Kylee Willard

Contributing Writers: Derinda Blakeney, Wravenna Bloomberg, Jamie Marie Edford, Matt Elliot, Mandy Gross, Christy Lang, Jim Mitchell, Stacy Pettit, Lorene Roberson, Marla Schaefer, Donald Stotts, Lindy Wiggins, Kylee Willard.

For details about research work highlighted in this magazine or reproduction permission, contact the editor.

Kelly Green, Editor, Vanguard 405.744.5827; vpr@okstate.edu research.okstate.edu

Greetings friends and colleagues,

As I’m sure you noticed from the cover of this magazine, Oklahoma State University — along with many others across the nation — celebrates a milestone this year: the 150th anniversary of land-grant universities. The Morrill Act of 1862 was indeed a turning point in the history of our nation. Through the provision of land, the act made a way for these new universities to support themselves. The act also defined the universities as ones that would benefit their communities, states, nation and the world through effective instruction, research and service.

At OSU, we hold that land-grant mission at the core of all we do. As you read through the stories in this edition of Vanguard, you’ll see example after example of the way our faculty and student researchers fulfill that mission every day. You’ll also find brief highlights from some of our historical research programs — some of which continue today. (Historical information on OSU’s research programs is provided by the Research volume of the Centennial Histories Series by Craig Chappell.) What we research and how we research has changed since the late 1800s, but what’s held true is our commitment to solve problems, find solutions and meet needs.

Please join us in celebrating this anniversary and enjoy these stories.

Cheers,

1910s

oSU AgricUlTUr AliSTS Speed Up reSe Arch efforTS To incre ASe food prodUc Tion And AlleviATe ShorTAgeS dUring world wAr i

1920s

oSU enToMologiSTS develop peSTicideS To coMbAT boll weevil S , which were devASTATing coTTon cropS in okl AhoMA And neighboring STATeS

1930s

oSU Schol ArS STUdy Soil eroSion ThAT led To The dUST bowl

1940s 1950s

wiTh The onSeT of world wAr ii , The oSU elec Tronic S lAbor ATory pArTnerS wiTh The feder Al governMenT in rockeT-bUilding efforTS

oSU biologiSTS ASSiST wiTh e Arly-dAy cAncer reSe Arch

EDUCATION

HOMELAND SECURITY BIOFUELS PLANT VARIETIES TEXTILES STEM BOTANY

scholarship and creative activity at Oklahoma State University

2 Setting the pace Dr. William Barrow leads veterinary pathobiology team toward a safer, healthier world.

6 OSU Space Cowboys: Living the dream with NASA

9 Student spotlight: Daniel Ede

10 The magnificent mango Nutritional sciences researcher finds mangoes reduce body fat and control blood sugar.

12 Microalgae: A versatile feedstock for biofuel and biobased products

14 The big top show goes on Oral history project examines culture of circuses with ties to Oklahoma.

18 Making the best crop varieties better

20 A hopeful heart

2012

22 Energy 101

New OSU institute will help America achieve energy independence.

26 Predicting bankruptcy Finance professors develop model to measure bankruptcy risk.

29 A center for STEM research

32 Up to the task OSU-CHS flight research now part of Oklahoma aviation history.

34 Rat research could save lives Zoologist Alex Ophir seeks to understand rats’ potential for bomb detection

36 OSU takes lead to help the wheat industry

38 From the landfill to the future OSU-Tulsa researcher finds use for discarded carpet

1960s

OSU pOlitical ScientiStS StUdy the SUcceSS and failUre Of prOhibitiOn lawS in OklahOma

1970s reSearcherS frOm OSU and Other inStitUtiOnS examine the qUality, qUantity and availability Of water reSOU rceS in OklahOma

1980s

1990s 2000s SenSOrS becOme an area Of fOcUS fOr OSU aS reSearcherS create detectOrS fOr everything frOm radiatiOn tO cOrrOSiOn

fOllOwing 9/11, OSU expandS itS reSearch in hOmeland SecUrity and develOpS Several defenSe-related technOlOgieS DISASTER RECOVERY SENSORS

PHYSICS UNMANNED AERIAL SYSTEMS

WHAT’S NEXT? COMPUTER SCIENCE NUTRITION

Oklahoma State University, in compliance with Title VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive Order 11246 as amended, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and other federal laws and regulations, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, disability, or status as a veteran in any of its policies, practices or procedures. This includes but is not limited to admissions, employment, financial aid, and educational services. Title IX of the Education Amendments and Oklahoma State University policy prohibit discrimination in the provision of services or benefits offered by the University based on gender. Any person (student, faculty or staff) who believes that discriminatory practices have been engaged in based upon gender may discuss their concerns and file informal or formal complaints of possible violations of Title IX with the OSU Director of Affirmative Action, 408 Whitehurst, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078, (405)744-5371 or (405) 744-5576 (fax). This publication, issued by Oklahoma State University as authorized by the Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer, was printed by Southwestern Stationery and Bank Supply at a cost of $6,308. (5M) 1/12. #3880

OSU pUrSUeS develOpment Of advanced material S thrOUgh laSer reSearch

1 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

40 Student spotlight: Kelsie Brooks

Research,

PACE SETTING THE

Dr. William Barrow leads veterinary pathobiology team toward a safer, healthier world

When asked what he does for fun, Principal Investigator William Barrow laughs and says, “Work.” The disciplined scientist has had 27 consecutive years of National Institutes of Health funding. Receiving a NIH award is difficult and keeping it is a constant challenge.

Barrow’s infectious disease and organizational background positioned him as a scientist willing, qualified and competent to take on the task of administering a multi-year, multimillion dollar NIH contract such as one he was awarded in 2003. The management and performance of that

contract, positioned him and his team well for their newest NIH award.

Currently executing a seven-year IDIQ (Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity) contract with a maximum potential value of $25 million, Barrow’s team at the Oklahoma State University Center for Veterinary Health Sciences is working on making the world a safer, healthier place. Barrow manages the contract and guides the overall performance of the team. The contract continues until May 31, 2018.

The purpose of this contract, Barrow says, is to provide the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious

Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu 2

Diseases (NIAID) with a broad range of in vitro assay capabilities that can be used to screen potential drugs for human infectious diseases or diseases of human importance caused by infectious agents.

In other words, in a controlled environment, like a test tube, they examine the effects of various compounds to see if they are effective against a panel of bacterial pathogens that are available now or will be available in the future.

“The services provided under this and other similar contracts will assist NIAID in accomplishing its goal of developing medical products to counter emerging, re-emerging and

other infectious diseases, as well as agents of bioterrorism,” Barrow says.

His team—all within the Department of Veterinary Pathobiology—includes co-investigators, Philip Bourne, Christina Bourne and Kenneth Clinkenbeard. Also involved in this contract are staff members Esther Barrow, Patricia Clinkenbeard, Mary Henry and Nancy Wakeham.

Back to the Beginning

Barrow, who has family roots in Oklahoma, has been interested in science since his youth.

“I wanted to know what made things tick,” he says.

As a young boy, Barrow wanted to become an M.D. He admired family doctors, some of which actually made house calls. He had a favorite uncle, Dr. Llewellyn Barrow, who graduated from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine in 1931 and played a major role in the discovery and development of the anti-nausea medication, Dramamine. This uncle, an M.D. in the U.S. Army during World War II, received a citation from a U.S. general for one of the first uses of the drug for the D-Day invasion and the fact that it had saved many lives by preventing sea sickness.

Later Barrow became interested in research. He completed his bachelor’s degree at Midwestern State University, and his master’s degree at the University of Houston focusing on how insecticides affected bacteria in the environment. After earning his master’s degree in microbiology, Barrow became the assistant lab director for the regional health department in Tyler, Texas. It was here that he learned more about bacteriology, mycology, parasitology and serology.

“Every quarter the state tested the lab,” explains Barrow. “We received a group of unmarked samples and we had to correctly identify each bacte -

rial pathogen or parasite, as the case may be. I learned a lot about diseases, what causes them, and how drugs work or don’t work to combat them.”

Barrow returned to graduate school at Colorado State University, where he earned his doctorate in microbiology in 1978 followed by a Heiser Postdoctoral Fellowship at the National Jewish Hospital and Research Center in Denver, Colo. That fellowship was sponsored by the Heiser Fellowship Program for Research in Leprosy. Additional training through an NIH Fogarty Senior International Fellowship was later conducted in the Tuberculosis Unit at the L’Institut Pasteur in Paris, France.

Raising the Ba R

Today Barrow’s research team uses in vitro assay capabilities accomplished with high-throughput screening and electronic database management to test potential drugs —techniques that were established during their first NIAID IDIQ drug screening contract.

“When we received the first NIAID contract, we purchased necessary equipment and developed programs to study the effects of a drug on our inventory of bacteria,” Barrow says. “We can use that same technology to do similar work for this contract.”

Barrow and the team use cultures and some reagents from BEI Resources— the main repository for cultures and reagents for microbiology and infectious diseases research. Their services are also supported by a contract through NIAID.

Barrow credits the good track record his team has and the expertise they have developed by working through the first contract as the reasons the team was awarded this new contract. His wife, Esther, also a microbiologist, has played an important part in

STORY CONTINUES > 3 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

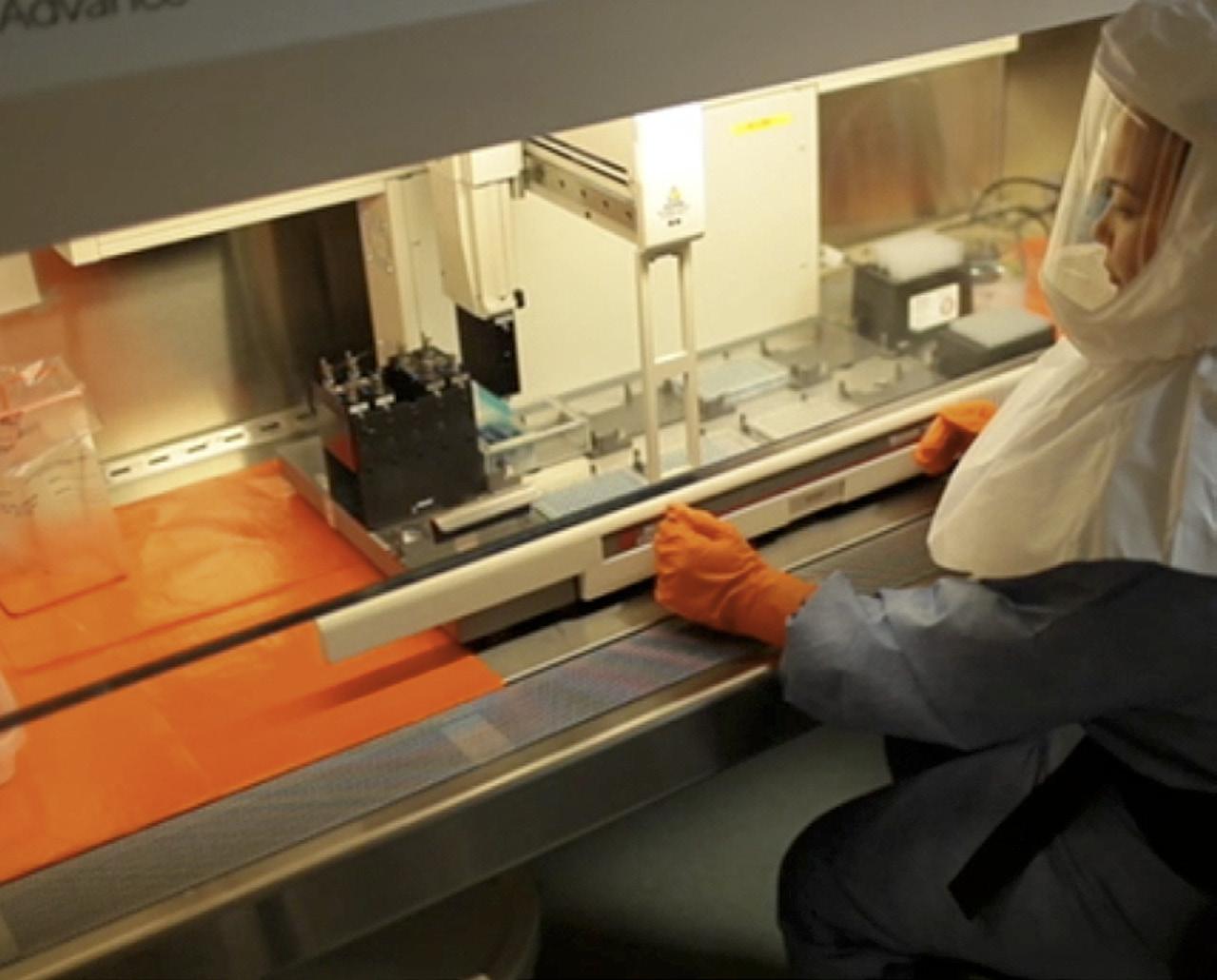

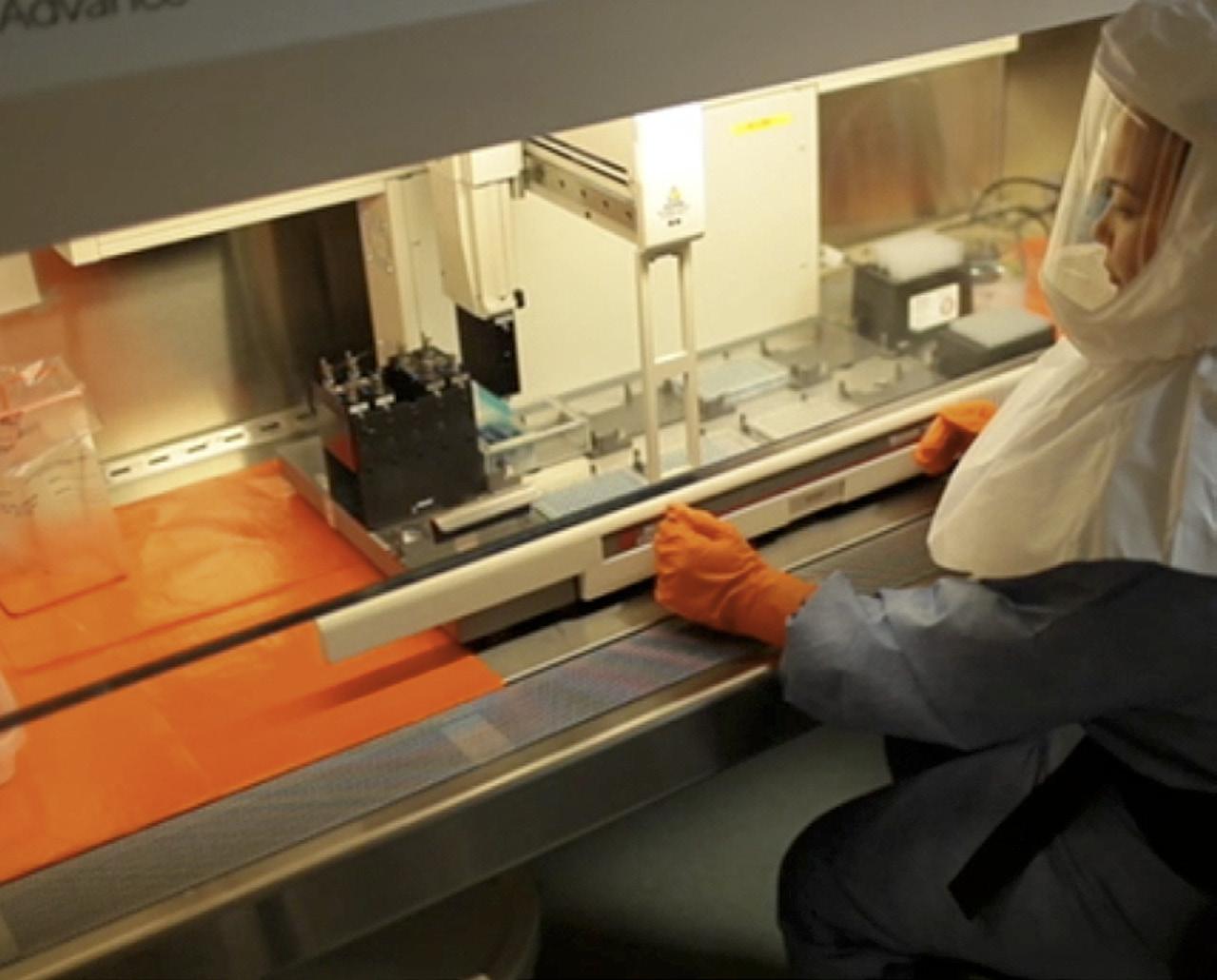

a laboratory technician works in a biosafety cabinet with proper personal protective equipment. research in b iosafety level 3 (b S l-3) biocontainment requires specialized training and advanced education. this high-level work is the norm for a team of veterinary pathobiologists at OSU’s center for veterinary h ealth Sciences.

the endeavor. Her efforts were instrumental in helping Barrow establish the research program that they brought to OSU, which eventually led to this contract and other NIAID awards.

“Bill is a really nice guy with a good sense of humor and an infectious laugh,” smiles Esther. “Sometimes people don’t see this side of him because he is so serious about his work. He is dedicated and always looking to the next step, the next logical research endeavor and preparing the proposal to compete for funding to make the research a reality.”

They aren’t the only husband/ wife duo on the team.

Phillip Bourne’s background is biochemistry. He manages the drugs to be tested as they are received. He also manages the electronic database, develops the robot programs and various drug screening programs and trains individuals on how to run the samples through each system.

His wife, Christina, brings molecular biology and crystallography to the team.

“She focuses on the mechanism of action studies as well as quality control,” Barrow says. “We routinely check our inventory of bacteria to make sure the genotype of the organism remains constant. This allows us to verify to NIAID that the test organisms have not changed and that we tested a particular drug against the strain of bacteria listed in our inventory.”

Ken Clinkenbeard is a co-investigator like the Bournes. He earned his doctorate in biological chemistry and has more than 35 years of experience working with infectious diseases.

“Esther, Patricia (Ken’s wife), Mary and Nancy are the worker bees,” smiles Barrow. “They make sure the tasks get completed and projects keep moving forward. They help train new employees and ensure our high standards of quality work.”

A total of 17 contracts were awarded under this program. Those contracts involve Part A (Bacteria and Fungi), Part B (Viruses), Part C (Parasites and Vectors), Part D (Toxins), and an additional Part E, which provides for a Central Data Management Center that will support the receipt, storage, quality control and analysis of all data generated under Parts A, B, C and D. The contract awarded to OSU’s veterinary center was one of six awarded for Part A.

“We have capabilities that a lot of groups do not have,” smiles Barrow. “You can’t screen certain organisms just anywhere. We have the appropriate laboratories, equipment, protocols and training in place to screen organisms that most institutions aren’t capable of handling. We can use the knowledge and training we have established to work with other groups and bring in more research funding to the veterinary center and to OSU.”

t he need foR answeRs

The scope of the work encompasses any type of in vitro assay work needed for infectious disease research, including routine screening of products and development of new in vitro assays and database management of work. According to the NIAID, providing different viable options will allow the NIAID to respond to changing priorities as scientific and public health needs shift, including rapid responses to public health emergencies.

“The importance of this research can best be explained by noting the increasing consequences of emerging infectious diseases and the development of drug resistance in various microbial communities,” Barrow says. “Microbial drug resistance generally develops in human beings as the result of improper use of antimicrobials. As observed in recent years, drug resistance can also develop in animal communities and be transmitted to humans. Look at the case of MRSA infection being transmitted from pigs to humans and the salmonella-related egg recall.”

Antimicrobial drug resistance can develop in all major groups of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), antibiotic resistance has been called one of the world’s most pressing public health problems. On April 7, 2011, the World

VETERINARY MEDICINE

After spending years trying to develop the world’s first successful vaccine for anapla S m OS i S, a fatal tick-borne disease in cattle, Oklahoma State veterinary researchers finally accomplished their goal in 1965. Glenn C. Holm, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine, announced that the first doses of the vaccine would be made available to veterinarians that fall. Manufactured and distributed by the Iowa-based Fort Dodge Laboratories, the vaccine, called Anaplaz© , was developed by a team of researchers headed by William E. Brock. Brock’s associates were Andrew W. Monlux, head of veterinary pathology, and Charles C. Pearson and Ira O. Kliewer (pictured) of the Oklahoma Veterinary Research Station near Pawhuska. The project was underwritten by a two-year grant of $60,889 from the National Institutes of Health.

Kathy Kocan, a Regent’s Professor and the Walter R. Sitlington Endowed Chair in Food Animal Research, has spent her 37-year career at OSU studying tick-borne diseases, like anaplasmosis, and working toward solutions. She and her team have identified the developmental cycle and transmission pattern of several tick pathogens – key first steps in the development of new vaccines. “Overall, I would like to see our research result in a vaccine that would contribute to a solution for tick and tick-borne pathogen problems,” Kocan says. “The ticks aren’t going away and ticks are changing as the world we live in changes. We need to keep the research moving forward to get closer to the answers we need. Preventative measures are needed to control ticks and tick-borne diseases and for the welfare of pets, production animals and people.”

LegacyLAND GRANT

Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu 4

phOtO / Special cOllectiOnS, OSU library

Health Organization made antimicrobial resistance an organization-wide priority and the focus of World Health Day; they consider drug resistance to be one of the top three threats to human health today.

Since 2001, the NIAID has been establishing a “…comprehensive infrastructure with extensive resources that support all levels of biodefense research.” Having accomplished this solid framework of research and product development over the last several years, the NIAID is “…now transitioning this infrastructure to provide the flexibility required to meet the challenges of emerging, re-emerging and other infectious diseases in addition to biodefense.”

Through the NIAID Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (DMID), a more integrated approach is now being created to perform in vitro assessments of antimicrobial activity for a broad spectrum of pathogens.

According to the NIAID, this strategy is being employed to “…advance science by promoting cross-fertilization across and within disciplines and approaches; serve the research community more conveniently; achieve effi-

cient use of resources through economy of scale and avoidance of duplication; and provide the flexibility needed to respond to changing priorities.”

“This is the reason for the multiple Parts A-E that were established by the new contracts recently awarded,” explains Barrow. “With these new contracts, the DMID is replacing the original in vitro programs with one broad IDIQ solicitation of multiple contracts to provide access to a larger number of qualified contractors, provide increased flexibility for services and thus more effectively cover all areas of current and potential future interests.

“It is the intent of the DMID that the procedures developed through this program will be shared among contractors within the program as well as with the wider research community. This in turn will assist the NIAID in its role in developing medical products to counter various emerging infectious diseases as well as agents of bioterrorism.”

Barrow is confident he and his team’s work will produce tangible results.

“I know that our work has a good chance of leading to the creation of

new products to address the issues of emerging infectious diseases and drug resistant strains and that will help make the world a better place for humans and animals alike,” he says.

In addition to benefitting NIAID, Barrow’s team’s research brings tangible benefits to the state of Oklahoma. As a result of the first drug screening contract, the veterinary center was awarded about $8 million. Of that amount, the college received almost $221,000 for renovations, about $500,000 worth of new equipment, about $2 million in indirect costs, and just over $546,000 for a fixed fee. The work generated almost $2.5 million for personnel labor, including fringe benefits. Under the contract, 2.5 percent of the total expenditures were designated to small businesses; some of which are located in Stillwater and other cities in Oklahoma. With the new contract, the OSU Center for Veterinary Health Sciences will be able to continue these research services and maintain its role in the Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Program that is currently evolving at the NIAID and throughout the country. Derin Da Blakeney

ph O t O / phil S h O ckley 5 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Members of Barrow’s Veterinary Pathobiology Team. (Front row) Dr. Bill Barrow and Esther Barrow (Middle row) Patricia Clinkenbeard, Dr. Christina Bourne, Mary Henry and Nancy Wakeham (Back row) Drs. Ken Clinkenbeard and Phillip Bourne.

OSU Space Cowboys

Living the dream with NASA

“ floating in zero gravity is the most exciting thing i ’ve ever done. it was like being in a dream.” Oklahoma State University student Shea fehrenbach from piedmont described just one of the many exciting moments that he and his teammates have experienced as part of naSa’s educational outreach efforts.

Fehrenbach started working toward that “dream” about a year ago when the OSU team— dubbed the “space cowboys” –became one of only ten chosen among the 75 universities that submitted proposals to participate in NASA’s Microgravity University. “It was a terrific opportunity and a testament to our students’ ability to put together a proposal to show NASA they had the ‘right stuff,’” said Dr. Jamey Jacob, professor of aerospace engineering at OSU and the team’s official adviser.

Shea fehrenbach floats in zero gravity aboard the weightless

PHOTOS COURTESY JAMEY JACOB 6 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

“When we shook hands with the astronaut commanding the last shuttle mission—I think my mind exploded a bit!”— Zack Deck

The students’ proposal addressed NASA’s request to supply an astronaut living environment with artificial gravity for long duration space missions. “Our idea was to use a rotating inflatable system to generate artificial gravity for the astronauts so they won’t experience the side effects that usually happen when working in a weightless environment, such as muscle and bone loss,” said Kristin Nevels from Claremore, who served as one of the team leaders.

For Kristin, Shea and a few others, the microgravity work represented only a portion of their involvement with space projects. They were also members of another OSU team of space cowboys that qualified as one of three national finalists for NASA’s first ever Academic Innovation Challenge. Also known as X-Hab, the challenge was to design an inflatable space habitat or “loft,” for astronauts on long duration flights. The team included members from mechanical and aerospace engineering in the College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology, like Kristin and Shea, as well as interior design students from the College of Human Sciences at OSU.

“With all our projects in mind, I thought it would be good to give the students a chance to look at some of NASA’s hardware and consider how best to integrate the designs they were developing,” said Dr. Jacob, who worked out the details in November of 2010 for a valuable road trip to Houston, home of NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

While there, the students were allowed to discuss research applications with scientists and also visit labs, including the Neutral Buoyancy Lab, where astronauts spend much of their time underwater training for spacewalks. It includes a full scale mockup of the International Space Station immersed in a giant swimming pool.

After meeting with some of the astronauts, Zack Deck of Midland, Texas, put into words the enthusiasm the space cowboys were feeling on that initial visit. “When we shook hands with the astronaut commanding the last shuttle mission—I think my mind exploded a bit!”

Memories of the trip mingled with the serious design plans as both teams returned to OSU to bring their concepts to life and offer NASA working prototypes. Six months later, in June of 2011, they were headed back to Houston, anxious to see their life-sized, inflatable loft put to the test and do some testing with a small-scale model of their rotating system in zero gravity.

After a few days of required NASA training, Fehrenbach was

“living the dream” as he rode in a specialized aircraft that flew dizzying maneuvers over the Gulf of Mexico so he and his colleagues could perform experiments in a microgravity environment. “Floating around and conducting an experiment was like being an astronaut for two hours. The experience of zero gravity was like nothing I’ve ever felt before and the experiment itself essentially proved that our rotational concept was feasible for deployment,” said Fehrenbach.

Once back on earth, the space cowboys watched as NASA technicians lifted their life-sized X-Hab loft design into place atop the habitat demonstration unit—a totally new place to proudly display an image of Pistol Pete.

Though the team’s design for X-Hab didn’t move on to field testing, the space cowboys realized they’d won a place in NASA’s history for their alma mater. “I’m really proud of the work we did for NASA during the 2011 X-Hab competition, it was a oncein-a-lifetime opportunity,” said Cory Sudduth from Allen, Texas.

STORY CONTINUES >

7 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

kristin nevels, alyssa avery, Shea fehrenbach, Zach barbeau and ben loh with naSa’s robonaut.

The team also managed to impress some professionals along the way. “The astronauts who helped judge our concept were very impressed with the unique design our students came up with, including its robustness, flexibility and safety, and NASA has stated that it wants to explore our design elements for use in their manned space exploration program,” said Dr. Jacob, who traveled with the team to the Johnson Space Center in June.

This is where the story is supposed to end, but it doesn’t. Instead, at NASA’s

invitation, the OSU Space Cowboys traveled to the Arizona desert in September to witness for themselves all phases of the X-Hab program— every new and exciting gadget.

“One of the greatest features of our Arizona trip was getting to see NASA demonstrate its new space exploration vehicles, such as the Robonaut and Chariot over rough terrain and observe how they’ll be used to collect and transport geological samples on Mars,” said Sudduth.

In addition, NASA announced in August that OSU is one of two universities that will participate in a new phase of the X-Hab project with a new goal—a deployable habitat that would give astronauts more living space during their eight-month trip to Mars.

“I’m very excited about this year’s X-Hab project since we will have much more design freedom, which will allow us to explore a wide realm of space habitats,” added Sudduth.

In other words, the dream continues.

Jim m itchell

8 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Jamey Jacob, k ristin n evels, cory Sudduth, Zach b arbeau, Shea fehrenbach, b en loh and alyssa avery with na Sa’s deep Space h abitat demonstrator at d - ratS, where they test the hardware in the arizona for evaluation for the moon and m ars.

Exploring solutions for Haiti

The 2010 Haiti earthquake impacted Daniel Ede, stirring him to seek a future solution to help minimize similar future disasters in developing countries.

The civil engineering senior from Tulsa had gone on several short-term missions trips in high school. In places like Mexico and Guatemala, he did construction work on homes, churches and schools. “I noticed right away that their building practices were different than here in the U.S.,” Ede said.

As in many developing countries, homes and other structures in Haiti are built with under-reinforced concrete masonry. Under the pressure of that 7.0 M earthquake, those structures failed and collapsed like decks of cards, trapping and killing thousands. Natural disasters cause this sort of damage in many other developing countries too.

“Around the world, people live each day at the mercy of their surroundings,” Ede said. “As they sleep, they trust their shelter won’t collapse. As they go to work, they trust the bridge will hold or the watersheds will control the floodwaters of the rain. Too often, when uncontrollable disasters occur in developing countries, the blame is placed on merely nature and not the man-made surroundings.”

As he watched the turmoil play out in Haiti, Ede wondered if actions taken beforehand could have allowed for much less loss.

He decided to pursue a solution.

As the first of his two Wentz Research Scholarships, he explored the effects of bamboo as a reinforcing material for buildings in developing countries. Known for its strength and durability, bamboo is one of the fastest growing plants in the world and can be found in diverse climates. It is also inexpensive and more readily available in those countries than steel rebar, the primary reinforcement material used in the U.S.

To test his hypothesis, Ede compared two walls made of cinder blocks and concrete mix – one reinforced with bamboo and one not – at increasing loads to determine the efficiency of bamboo as a reinforcing

Daniel Ede

material. He found his bamboo-reinforced wall withstood more than three times the amount of lateral load than did the under-reinforced concrete wall. Although additional research is necessary, Ede says his results suggest bamboo is extremely beneficial in providing added protection against wind and seismic loads.

“The research process was a great experience,” Ede said. “I knew I wanted to do engineering when I came to OSU, but I didn’t know anything about research. I thought it was something professors did.”

Ede received a presentation award for his work at OSU’s annual Wentz Research Day, an event that brings together all of the current undergraduate researchers at OSU funded by the Wentz Foundation to present their results. He is also now embarking on his second Wentz project: a comparison of insulating concrete forms (ICFs) and wood-framed walls.

Following completion of his bachelor’s degree, Ede plans to get a civil engineering job. He said his experience in research has already set him apart in several interviews. He also plans to continue taking short-term missions trips, bringing what he’s learned in the lab to the doorsteps of the people who could benefit the most from it.

STUDENT SPOTLIGHT

9 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

phOtO / kevin mccrOSkey

Magnificent Mango The

Nutritional sciences researcher finds mangos reduce body fat and control blood sugar.

phOtOS by phil ShOckley 10 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

While it may not get the publicity of say the blueberry, or even the acai berry, the addition of mango to a diet may combat obesity and diabetes, according to research conducted by a nutritional sciences associate professor in OSU’s College of Human Sciences.

According to a group led by Edralin Lucas, incorporating mango in the diet could help cut body fat and control blood sugar.

“Our findings demonstrate that mango flesh is a promising alternative that can be useful in reducing body fat and blood glucose,” Lucas says.

Plus, Lucas says, mango is not associated with serious side effects of some drugs used for the same purpose.

Obesity and consumption of high fat diet are associated with the development of many chronic diseases including type 2 diabetes and heart disease. Drugs, such as rosiglitazone and fenofibrate, used to treat the diseases can increase the risk of bone fractures, liver enlargement, fluid retention and heart failure.

Lucas and co-investigators

Penelope Perkins-Veazie, Brenda Smith, Stephen Clarke and Stanley Lightfoot conducted the study funded by the National Mango Board.

Lucas and her colleagues chose the Tommy Atkins mangos because they are one of the most common varieties in the U.S. The mango flesh was freezedried, ground into a powder and added to mice diets.

The team formulated six diets, one with 4 percent of calories from fat and

LegacyLAND GRANT

five with 35 percent of calories from fat. One of the high-fat diets did not include mango powder, while the other four high fat diets contained 1 percent mango powder, 10 percent mango powder, fenofibrate or rosiglitazone.

The team assigned eight mice to each of the six diets and allowed them to eat and drink at will for two months.

After two months, Lucas and her team found no statistically significant differences in body weight among the mice, but the amount of body fat was varied according to the diets. The mice consuming diets with mango or the two drugs had body fat levels similar to those mice eating the lower-fat diet.

The mango-containing diets also exhibited glucose and cholesterol lowering properties. In fact, the 1-percent mango diet had a similar or even a more pronounced effect in reducing blood glucose than the diet containing rosiglitazone. The team further observed mango affected several factors involved in fat metabolism.

Lucas says human studies should be done to confirm the team’s findings and further investigation should focus on understanding how and what components of mango are responsible for its effects on body fat, blood glucose and lipids.

The findings, she says, do demonstrate the addition of mango to the diet may help prevent metabolic syndrome — a cluster of conditions like obesity, insulin resistance, high cholesterol and high blood pressure that can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

HUMAN SCIENCES

“We will soon be conducting a human study to investigate whether the addition of mango to the diets of pre-diabetics will help them control their blood sugar and whether incorporation of mango into the diet of overweight people will help them reduce body fat,” Lucas says. “We are also investigating how mango reduces body fat and blood glucose.”

Lucas hopes the findings will encourage people to make better food selections.

“We would like to see people try to make healthy food choices such as including many fruits and vegetables like mango in their diets,” she says. “It would help prevent many chronic diseases including obesity and diabetes.”

lin Dy Wiggins

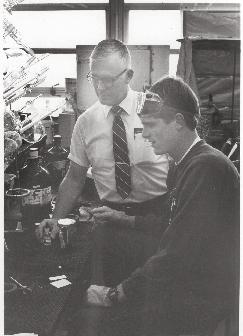

In the 1980s, scientists from OSU’s home economics college searched for new food sources, especially as solutions for shortages in underdeveloped countries. Christa Hanson and Sue Knight (pictured) experimented with dried yeast protein as a food additive. As a result of this work, Knight was able to develop “Meal on the Go,” a complete meal in a bar.

Today, Barbara Stoecker, a Fulbright Fellow and Regents professor in OSU’s College of Human Sciences, conducts research on malnutrition in Ethiopia with an international team of scientists. She has assisted Hawassa University in Ethiopia in developing a curriculum for a master’s degree in nutrition and is credited with making a difference in building the academic capacity of the university and Ethiopia. She has worked with impoverished women and children in Africa, Iraq and Jordan to determine how best to prevent mineral deficiencies.

ph O t O / phil S h O ckley phOtO / Special cOllectiOnS, OSU library 11 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Nutritional Sciences Associate Professor Edralin Lucas leads a group in OSU’s College of Human Sciences studying the effects of mango on lowering blood glucose and reducing body fat.

Microalgae

A versatile feedstock for biofuel and biobased products

Uncertainties in supply and price of non-renewable energy sources and the environmental concerns over the adverse effects of fossil fuels have led researchers at Oklahoma State University’s Robert M. Kerr Food & Agricultural Products Center to explore alternative fuel sources.

“Currently, biofuels such as bioethanol and biodiesel are mainly produced from corn and vegetable oils in the U.S.,” said Nurhan Dunford, FAPC oil/ oilseed specialist and OSU department of biosystems and agricultural engineering professor. “Today, there is no bioethanol production facility in Oklahoma because the amount of corn grown in the state cannot meet the needs of a bioethanol production facility. At this point, these operations have to rely mostly on feedstock coming from outside the state.”

With the local alternative feedstock need in mind, Dunford and her group of student and faculty researchers have been examining non-food crops such as microalgae as potential biofuel and bioproduct feedstocks.

“Microalgae are microscopic organisms found in both marine and freshwater environments,” Dunford said. “Various types of algae are among the most efficient plants to convert solar energy to chemical energy, and microalgae can accumulate a wide range of commercially important products like oil, sugar, protein, cellulose and highvalue functional bioactive compounds.”

Microalgae, the non-food feedstock, offer diverse uses.

“With microalgae, we can clean waste water while generating biomass,” Dunford said. “Microalgae are capable of absorbing excess plant nutrients

Faculty

sources. phOtOS by kylee willard 12 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

and student researchers are studying microalgae as potential biofuel and bioproduct feedstocks because of the need for local alternative

from waste water and using CO2 to produce oil, biomass and even useful high-value compounds.”

As an alternative to land planted crops, microalgae can grow and thrive in water sources such as ponds or animal waste streams.

“Microalgae systems use far less water than traditional oilseed crops,” Dunford said. “By use of microalgae, it would take only 1 to 3 percent of the existing U.S. crop area to replace half of the petroleum-based transportation fuel with biodiesel. More importantly, microalgae do not compete with cropland.”

Research shows many microalgae strains can accumulate as much or more oil than oilseeds.

“Microalgae may have 30 to 70 percent oil, based on dry algal biomass, while soybeans contain about 20 percent oil,” Dunford said. “The high oil content and rapid biomass production make microalgae a very attractive renewable source for bioproduct manufacturing.”

The project

The scope of the research project includes developing a semi-continuous microalgae system that maximizes production of algal biomass with high oil content, captures carbon dioxide produced by power plants and ethanol production facilities, and reduces the adverse impact of agricultural waste water on environment.

“Successful completion of this project will take researchers a step closer to a non-food feedstock source that can be produced on non-agricultural land with less space requirement than today’s feedstocks used for biofuel production,” Dunford said.

Initially, research stemmed from purchasing six microalgae strains from a culture bank.

“Three of the strains are native to Oklahoma, while the other three have high oil content and possess traits of adaptability to the Oklahoma environment and are an interest to many startup companies,” Dunford said.

Testing began in 10-milliliter test tubes and has advanced to 10-liter bioreactors.

“From 10-milliliter to 1-liter to 5-liter and now to 10-liter bioreactors,

testing has been successful in the lab in a controlled environment,” Dunford said. “Today, we can effectively grow and harvest these microalgae strains.”

From the lab to the OSU Swine Farm Procedures from the microalgae laboratory testing were mirrored in a study that involved growing microalgae in waste water obtained from a lagoon at OSU’s Swine Farm.

Flint Holbrook, a biosystems and agricultural engineering junior, commenced work on the microalgae project three years ago as a freshman. Holbrook focused on inhabitation of microalgae in animal waste streams. Holbrook and his team followed the labtested protocols to perform the animal waste water experiments.

“We found that the microalgae grew in the wastewater and absorbed nutrients floating in the lagoon,” Holbrook said. “In theory, microalgae could remove pollution and absorb CO2 and other greenhouse gases.”

algae,” Holbrook said. “How do you make it profitable? How do you get out of it more than you put in? The goal is to help commercialize microalgae and introduce these practices into the market.”

Future work

Next phases of the project include establishing protocols and mimicking real-life growing conditions. Recent research funding from the Department of Transportation through the South Central Sun Grant program will be used to design and install larger microalgae bioreactors in OSU’s biosystems and agricultural engineering greenhouse. The long-term goal is to put microalgae strains in an outdoor pond or directly integrate into animal waste water ponds.

“From the liter tests, we can develop processes to recover highvalue compounds from algal biomass,” Dunford said. “The next step would be the evaluation of economic viability of a commercial scale microalgae growth and processing facility and conversion

According to Dunford, Holbrook’s research demonstrated that one of the Oklahoma native microalgae strains can grow in swine lagoon water with no additional nutrients and removes a significant portion of the excess nitrogen present in the waste water.

“We worked to find the market and determine if we are able to grow micro -

of algal oil and biomass to biofuels and other high-value products.

Our ultimate goal is that results of this ongoing study could lead to establishment of an algal biomass-based industry that could produce biofuels and high value-added products in Oklahoma.”

k ylee Willar D

13 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Yan Zhu, OSU graduate student, and Nurhan Dunford, FAPC oil/oilseed specialist, examine microalgae strains in the FAPC laboratory.

“…I miss a lot of things about show business. When you’re sitting there on the sidelines and somebody rides into the center ring on a horse and does these tricks and is just fantastic and the audience just loves it and the band’s playing, you just can’t help but say, ‘I want to be a part of this.’ I still feel that, even today.”

—Robert Rawls, former circus performer

14 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

THE BIG TOP SHOW GOES ON

Ever thought of running away and joining the circus? If you live in Oklahoma, you only have to go as far as Hugo to do so.

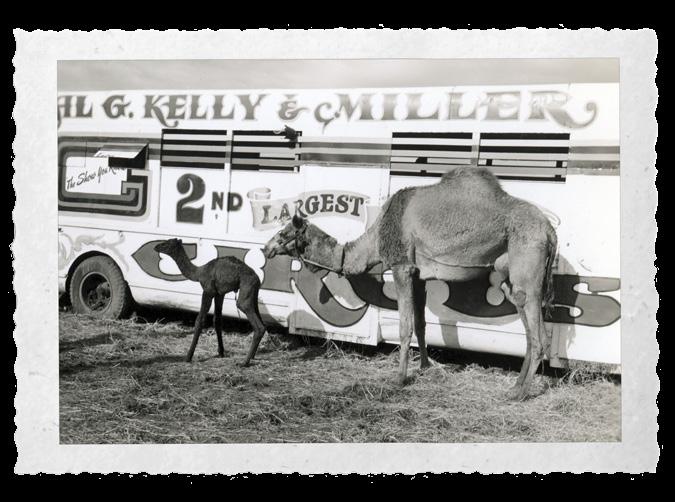

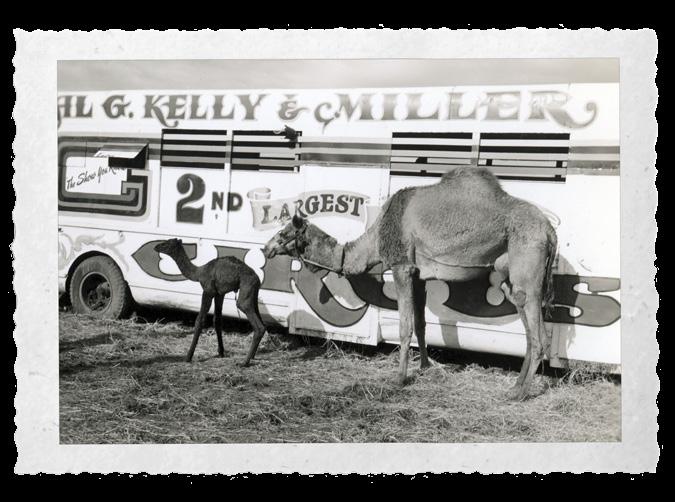

With a population of approximately 6,000, Hugo, Okla. has a long history of circus culture dating back over 70 years. More than 20 circuses have had winter quarters there. Currently three active circuses headquarter in Hugo: Carson and Barnes, Kelly Miller, and Culpepper & Merriweather. Traveling by road, these tent circuses entertain in towns of various sizes and in small rural communities throughout the country. The owners of Carson and Barnes also own and operate the Endangered Ark Foundation, the second largest Asian elephant sanctuary in the United States.

Led by librarians Tanya Finchum and Juliana Nykolaiszyn, Hugo and its circus legacy are the focus of an oral history research project at Oklahoma State University. The “Big Top” Show Goes On: An Oral History of Occupations Inside and Outside the Circus Tent is comprised of interviews with current and former circus performers living in Hugo. The effort is funded by an Archie story continues >

phOtO cOU rte Sy mike fU ltOn 15 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Green Fellowship from the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center. Named for the American folklorist interested in occupations and their cultures, especially those that are disappearing, the fellowships support new documentation and research into the culture and traditions of American workers that will create significant digital archival collections (audio recordings, photographs, motion pictures, field notes) that will be preserved in the American Folklife Center archive and made available to researchers and the public.

“This research is intended to fill a gap in our knowledge about day-to-day work involved with putting on a tent circus,” Nykolaiszyn said. “Preliminary research found very little documented information on this aspect of Oklahoma or on specific people or occupations within the circuses that have had their winter quarters in Hugo. An occasional article in the Daily Oklahoman would mention a Hugo circus with a personal name or two and would refer to Hugo as the Sarasota of the Southwest or the unofficial Circus City, USA.”

Oral history was established as a modern technique for historical documentation in the late 1940s, about the time the first circus wintered in Hugo. Qualitative interviews emphasize the

participants’ perspectives and give them a significant hand in shaping the content of the interview. The Oklahoma Oral History Research Program at the OSU Library was established in 2007.

“The circus is not just family entertainment. It is families doing the entertaining and all that that entails.”

— tanya Finchum

“Circus employees have historically been marginalized and their voices are missing from much of the documented record of occupations,” Finchum said. “As researchers we guide the interview as each participant narrates his or her story. We are seeking to learn and document circus life in relation to circus work.

“What is involved in the typical day of a tight wire walker during the circus season? How does a performer learn the trade? How does a family life coordinate with work in a circus? These are just a few of the questions this project hopes to answer as participants share their firsthand accounts.”

Finchum and Nykolaiszyn traveled to Hugo and met with the Circus City Showmen’s Club, a group of retired and semiretired circus showmen, to explain the project and recruit potential participants.

Twenty people — nine males and 11 females — shared their experiences and memories of circus work and life. The group represents three families with circus roots at least four generations deep. The majority of those interviewed were trained for the circus by either parents or grandparents. Four of the 20 are first-generation circus workers with an additional one marrying into the business and bringing a parent along. “The circus is not just family entertainment,” Finchum said. “It is families doing the entertaining and all that that entails.” Occupations of participants include: boss canvasman, manager, owner, tight wire walker, aerialist, bareback rider and cook.

As the interviews were transcribed, read and re-read, the researchers say commonalities and differences began to appear. “With each interview it became more evident that over the course of a career in the circus, a single employee may have many job assignments,” Nykolaiszyn said. “For example, as an aerialist ages and can no longer perform in the air,

(Left) Bareback rider Lucy Loyal performs as part of a Carson & Barnes circus, circa 1975. (Below) Animals, like these camels, traveled by road along with the rest of the circus performers.

(Left) Bareback rider Lucy Loyal performs as part of a Carson & Barnes circus, circa 1975. (Below) Animals, like these camels, traveled by road along with the rest of the circus performers.

ph O t O c OU rte S y l U cy l O yal phOtO cOU rte Sy mike fU ltOn 16 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

he or she may work the cookhouse and then later the concession stand.”

During one interview, Robert Rawls shared:

“I’ve done just about every job there is to do on a circus, much like the rest of my family. That’s nothing special in my family. If you’re on a circus, you might be a performer, but you also know how to set up a tent, to drive a stake, to operate a truck or a vehicle, or you know how well everything is laid out. You can do the 24-hour man job. You can do it all. We were trained to do everything. So, whenever you’re on a circus, you were always called to do something outside your so-called job description.”

Many of the participants also equated the circus to a small town that moves every day and requires people to live and work in small spaces and in very close proximity.

As shared by Mary Rawls:

“Most of the shows we were on were small and if they weren’t small, then you had a clique of small and they were all friendly. You just felt part of a small town. It was very homey. Everybody knew everybody else and it was just like you lived in a little town that picked up and moved every day. It was very cozy and of course, if you came out with

circus slang or something, somebody knew what you were talking about. If you’re talking to a ‘towner’ well, then you’ve got to explain what you’re talking about.”

Statements like Mary’s reflect that although there is very little privacy there is a tight bond among members of the circus community. During the season, the circus may relocate over two hundred times, which means long days and a definite routine. With each “jump” there is order as to which truck arrives first, what each person does at each phase of the set up and take down, and what goes where and when. The researchers found this aspect of the circus has changed very little historically.

One of the unexpected realizations noted by the researchers is the impact regulations have on circuses. Day after day as the circus moves through different jurisdictions, circus management deals with numerous officials. From health inspectors to fire marshals, each town has ordinances for which the circus must comply. In addition to having skills to interact with the paying public, the circus manager needs skills in negotiation, diplomacy, time management and legalese.

The researchers also found that the participants’ identities are closely tied to their work. Circus performers identify themselves as show people, as entertainers. They take great pride in their circus heritage and no matter their age, they can

close their eyes and mentally perform.

“With the steady decline of traveling tent circuses, there are fewer and fewer people with first- hand experiences of working in them,” Finchum said. “An end goal of this project is to preserve these narratives for future researchers and to fill in the gap of documented information about this group of the working class.”

This project will also serve to document part of the cultural heritage of southeast Oklahoma and Oklahoma in general. “Circuses that have wintered in Hugo have brought economic benefits to the area as well as entertainment to citizens in the state,” Nykolaiszyn said. “Historically these tent circuses followed the agricultural seasons and set-up on cotton gin lots or ice plant lots. Finding a vacant lot large enough to accommodate a tent circus is becoming more challenging and add the increasing regulations and immigration issues to that, the life of the tent circus is teetering on the edge of an uncertain future.

“Their continued existence is evidence that the circus is still magical for people of all ages and is truly one of the last great family entertainments.”

Original recordings and transcripts from this project will be deposited into the American Folklife Center were they will be archived. Copies will also be deposited into the OSU Library where the transcripts will be made accessible online at www.library.okstate.edu/ oralhistory/circus

k elly g reen

17 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

in the h ugo cemetery a special section marked “Showmen’s rest” honors the lives and careers of elephant trainers, tight wire walkers and other circus performers.

Drought resistance, disease resistance, producing both quality and quantity: all are desired traits of new wheat varieties developed on behalf of producers and related agribusiness operators by the Oklahoma State University Wheat Improvement Team.

“Access to genetically improved cultivars with marketable grain quality that stand the best chance of weathering Oklahoma’s often-harsh growing conditions is the lifeblood of the state’s wheat industry,” said Brett Carver, WIT leader and holder

of OSU’s wheat genetics chair. “It’s no small challenge.”

Wheat and other “general crops” such as soybeans, cotton and hay accounted for approximately $905 million in lost agricultural production from Oklahoma’s excessive and historic 2011 drought. Wheat harvested in Oklahoma totaled 166.5 million bushels in 2008, 77 million bushels in 2009, 120.9 million bushels in 2010 and 74.8 million bushels in 2011.

“It’s been quite a roller coaster ride for our state wheat producers, and not the fun kind; they need to

plant the best adapted crop for their area, which underscores the importance of the work being conducted by our WIT researchers,” said Clarence Watson, Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station associate director.

Watson pointed out that the continued improvement of wheat cultivars is more heavily dependent than other crops on public research like that done at the nation’s landgrant universities.

Three of the top four wheat varieties planted in Oklahoma for the 2011 crop year were developed

Making the best crop varieties better

OSU Wheat Improvement Team

phOtOS by tOdd JOhnSOn Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu 18

“We can do better. That is the landgrant university mission. It’s who we are and what we do.” — Brett c arver

by scientists with OSU’s Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources: Endurance, the most popular variety with 18.9 percent of total wheat acres planted; Duster, the second-most popular variety with 16.6 percent; and OK-Bullet, the fourth-most planted variety accounting for 7.2 percent of total acres.

In 2011, two new OSU-developed wheat varieties were made available: Garrison and Ruby Lee.

Garrison has statewide adaptability and produced consistently good yields over a five-year test period. It has excellent tolerance to acidic soils and matures relatively late and thus misses early spring freezes. Garrison has good tolerance to fusarium head blight, a disease that can hurt grain yields grown in a wheat-corn crop rotation. The variety is considered to be a replacement for Endurance with better disease resistance, test weight and good protein.

LegacyLAND GRANT

Ruby Lee also has statewide adaptability plus superior yield potential and outstanding milling and baking characteristics. It produces a high test weight and very large kernel size, is earlier to mature than Endurance and is an excellent fall forage-producing variety.

In a normal year, Oklahoma producers plant about 2.5 million acres of “dual-purpose wheat,” which are used for livestock grazing during the fall and winter months and then are harvested for grain by early summer.

“Ruby Lee is an alternative to the high-production levels of our Billings variety, where soils have a pH level more

than 5.5, with better cold tolerance and dual-purpose yields,” Carver said.

Carver and his fellow OSU wheat breeders were concerned that drought conditions would make data scarce this year for many varieties. Instead, the team members’ thoughts about many varieties’ drought tolerance were confirmed.

“Many of the varieties that have Duster in their parentage continued to shine, combining relatively good drought tolerance with strong disease resistance,” he said. “But as great as these varieties are, we can do better. That is the landgrant university mission. It’s who we are and what we do.”

DonalD s totts

AGRICULTURE

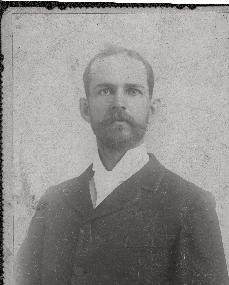

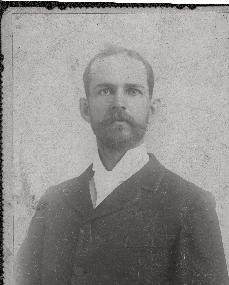

Although James C. Neal served as the first director of the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station – the university’s first engine of research – most of the work fell on Alexander C. Magruder, who served as the first professor of agriculture as well as supervisor of the college farm. Magruder was responsible for planting the famed Magruder Plots (pictured left) for research on wheat. In continuous wheat cultivation since 1892, the plots are the oldest agricultural research project west of the Mississippi River.

Magruder (pictured right) was a man of many “firsts” at the college. He was the first agriculturalist. He was the first instructor at the college. He took the first steps toward developing a school library by either buying books or talking publishers out of samples. He established the first livestock feeding trials. He organized Oklahoma’s first agricultural support organization, the Oklahoma Agricultural Society. He established the first student awards – using his own money – by commissioning gold medals to be given for best oration by a student, presented from 1893-1895.

library ph O t O / Special cO llecti O n S , OSU l ibrary 19 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Wheat grows in greenhouses at the Stillwater Experiment Station, where researchers from OSU’s Wheat Improvement Team are breeding new varieties of wheat with greater drought tolerance and disease resistance. phOtO

/ Special cOllectiOnS, OSU

Hopeful A

Cardiovascular disease. Coronary artery disease. Congestive heart failure. These heart centralized issues have affected millions of people over the years with limited answers in disease treatment. However, a breakthrough in the area of gene therapy is less than two years from research completion.

The department of chemical engineering within the College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology at Oklahoma State University has been working on vector manipulation, funded by the American Heart Association.

Currently, the use of gene therapy to cure diseases is hindered by its inability to provide a safe and effective delivery to a specific location in the body. A virus provides the ability to target specific cells, but can be dangerous. Because of

20 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

this, a vector offers the most promise as it serves as a nano-scale transportation device to deliver the gene to the targeted location, while remaining much safer than using a virus.

Dr. Joshua Ramsey, assistant professor of chemical engineering, leads a group of researchers focusing on developing synthetic vectors that are engineered to imitate a virus. By altering viral genes and using synthetic components, this process would trick the body into accepting the vector instead of viewing it as an infectious virus.

“The intent is to develop nanoparticles capable of delivering therapeutic genes to vascular tissue for the treatment of cardiovascular disease,” said Ramsey. “The impact, however, will be much broader. The vector we are working to develop will be modified in the future to target a variety of diseases.”

The long-term goal of this research is to replace the knob and fiber proteins of adenovirus with a synthetic cellpenetrating peptide. This combination of peptide and genetically modified virus would result in a nanoparticle that presents the same efficiency of a virus, but offers flexible targeting and immu nity resistance.

The fiberless adenovirus nanopar ticle presents significant advantages over the native adenovirus being used. Specif ically as it offers flexible targeting to vascular endothelial cells, said Ramsey.

In the past, a patient needing gene therapy treatment had two choices: viral or synthetic vectors. The viral approach presents safety concerns, but is still more effective than synthetic vectors. This research is focused on creating

a marriage of these approaches by isolating the functions of the virus and using synthetic materials, such as cellpenetrating peptides, to target and enter diseased cells while avoiding the drawbacks associated with a virus.

Mechanical revascularization is currently common for heart related diseases, but is not always an option for all patients. Thus, this therapeutic approach, through targeted gene delivery, offers hope. There has long been potential in this area, but unfortunately the viral vectors, considered the most efficient and stable approach, has been associated with extreme setbacks including severe immune responses and resistance over time.

Because of this, synthetic vectors have been deemed safer. Yet, the poor efficiency of synthetic vectors has prevented advancement of gene therapy beyond the clinical trial stages. The need for a combination of the effectiveness of viral vectors with the safety of synthetic vectors is what laid the foundation for this research.

By replacing existing knob and fiber proteins with these peptides and targeting ligands, it will allow attachment of the vector to a specific target cell

overall approach to design a novel vector,” said Ramsey. “The vector will need to be validated in animal trials and eventually transitioned into human clinical trials.”

Ramsey mentions with the long process from lab research to clinical trials, there is significant investment in both time and money. “As long as our approach continues to show promise, however, there is incentive to quickly advance the treatment so patients can benefit from it.”

The impact of this research is expected to enhance the general field of gene delivery by leading to discovery of principles that would enable better design of vectors and increase gene delivery use through effective synthetic nanoparticles.

The College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology at OSU is focused on its core mission of advancing the quality of human life, specifically through instruction, outreach and research.

“There is a growing group of CEAT faculty doing cutting edge research in the biomedical fields and having a real impact on the future of medicine,” said Ramsey. “Gene therapy truly has the potential to change the way we treat disease.

phOtO

21 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

Dr. Joshua Ramsey, assistant professor in chemical engineering, engages in research for engineering novel gene delivery vectors.

/ phil ShOckley

Energy Solutions

the National Energy Solutions Institute will provide knowledge and resources to help america achieve energy independence

Anew collaborative group of researchers at Oklahoma State University all say the same thing: we need a diverse profile of clean, efficient energy sources to solve the world’s energy problems. The solution, they say, isn’t in one area, such as wind or solar, but in using the correct combination of all the sources of energy available today, including oil and gas.

Under the direction of Dr. Stephen McKeever, OSU’s vice president for research and technology transfer, the group has come together to form the National Energy Solutions Institute, an effort that, according to McKeever, will fuse the needs

of private industry in energy production, distribution and conservation with practical and impactful academic research.

“The emphasis of the research will be on providing practical energy solutions for the current and future needs of the nation,” McKeever says. “Researchers will work in collaboration with private, state and federal sectors to enable the nation’s transition to a sustainable energy future.”

To do so, the institute will include several centers that build on the ongoing work of OSU’s key energy research programs. The institute’s researchers represent three colleges and five departments on the OSU-Stillwater campus.

22 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

OIL AND GAS

Led by OSU Geology Associate Professor Dr. Jim Puckette, the Unconventional Hydrocarbon Fuel Research Center focuses on finding elusive conventional petroleum reservoirs and improving recovery of oil and gas from unconventional reservoirs.

“Barring a fantastic breakthrough, renewable energy will provide just 20 to 30 percent of our energy demand over the next two to three decades,” Puckette says. “I’m completely in favor of renewables, but there’s just more work to be done to make them feasible.”

Puckette says in the meantime improvements in the exploration and recovery of oil and gas provide excellent opportunities to lessen dependence on foreign reserves. Currently, the most successful unconventional fossil fuel development is in shale gas. Although shales typically have insufficient permeability for commercial natural gas extraction, new drilling techniques have significantly increased their feasibility as a source of energy.

“New horizontal drilling and completion techniques, including multistage hydraulic fracturing, have allowed the development of this energy resource to the extent that it, along with coalbed methane, has reversed the decline in U.S. gas production with a more than 3000 percent increase in gas production being

recorded over the past decade,” Puckette says.

The strategic technical goals of the center are to conduct research and education programs on unconventional hydrocarbon resources and to integrate geology, geophysics and engineering to better understand and develop these resources in the future.

Once these sources of fuel have been discovered and extracted, researchers at The Center for Clean Fuel Production will focus on limiting their effects on the environment. “The energy security of the U.S. is predicated on a reliable supply of domestic energy and the efficient use of all energy resources,” says Dr. Khaled Gasem, OSU professor of engineering. “This translates to the need for technologies to utilize fuels of reduced carbon content, improve efficiencies in energy use, and capture and sequester carbon.”

Led by Dr. Khaled Gasem, the CCFP will investigate ways to capture carbon using molecular design of chemicals along with ways to use it to enhance oil and coalbed methane recovery. The center will also help create viable technologies to address global climate change and integrate multiple technology platforms and engineering models to optimize production and utilization of energy resources.

BIOFUELS

Biofuels made a name for themselves at OSU and throughout Oklahoma several years ago. However, Dr. Ray Huhnke, OSU professor of biosystems and agricultural engineering and head of the OSU Biofuels Team, says there’s plenty of research still to be done. Through the Center for Integrated Bio Energy Systems, Huhnke and an interdisciplinary team at OSU and cooperating institutions will create new advanced biofuel production practices that will enhance and strengthen the state’s multi-billion-dollar energy industry.

“This center provides a multi-disciplinary approach to address bioenergy issues such as cellulosic ethanol, production, distribution networks and economics to train personnel from around the world on the possibilities and benefits of harnessing renewable energy resources,” Huhnke says. “The approach is a holistic one in which biofuels production is considered alongside food production, land use and water resources.”

The OSU Biofuels Team is a multi-college, multi-institutional effort, encompassing scientists and engineers within the OSU Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources; the OSU College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology; the University of Oklahoma; The Noble Foundation and Brigham Young University. Research being conducted by the team involves the study of several promising biomass-toadvanced biofuel pathways, including feedstock development (such as switchgrass, sorghum, woody materials and crop residues) and both chemical and microbial conversion processes (such as the gasification-fermentation technology). Huhnke says applications will include primarily road transportation fuels and also jet fuels for the air transportation industry, which are of ever-increasing importance.

STORY CONTINUES >

23 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

WIND

In Oklahoma it may be sweeping down the plains, but how can wind energy be efficiently harnessed and distributed? The Oklahoma Wind Power Initiative, a collaborative research and outreach project between OSU and the University of Oklahoma, will also be a part of the National Energy Solutions Institute. OWPI investigates and promotes wind energy resources and provides economic information to policy makers, land owners, wind farm developers, potential investors and interested citizens. OWPI has accomplished a wide range of tasks since its inception in 2000 that leave it poised now to tackle problems even outside of Oklahoma.

“This work has included modeling the wind resources of Oklahoma, installing instrumentation to confirm those resources and statistically analyzing data obtained,” says Dr. Steve Stadler, OSU professor of geography. “Since 2004, Oklahoma has seen the installation of 1.5 gigwatts of installed wind capacity with much more under development. It is a multi-billion dollar industry in Oklahoma alone.”

OWPI’s efforts have used spatial analyses within geographic information systems to determine optimal turbine placement in the context of multiple environmental and social factors. There are areas in which OWPI’s unique expertise can be readily extended, Stadler says, including wind resource modeling, educating future wind industry professionals and assisting in the formation of locally owned wind cooperatives.

POWER G ENERATION , TRANSMISSION AND DISTRIBUTION

To realize the full benefits of new energy sources, the nation needs to upgrade its existing electric power grid into a “smart” system, says Dr. Rama Ramakumar, an OSU Regent’s Professor from the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. Led by Ramakumar, the Center for Power Generation, Transmission and Distribution will develop concepts, components, subsystems, software and interfaces needed to achieve this goal. R&D efforts will include: development of sensors for monitoring electrical parameters and

their temporal variations; innovative architectures and models for the smart grid; data collection and handling (from smart meters, smart appliances, etc.); integration of distributed renewable energy sources with existing/modified grids; exploring the potential of microgrids; and cyber and physical security. Ramakumar and his team will conduct synchronized activities involving model formulation, simulations and laboratory experiments to advance and sustain the necessary technology.

IMPACTING POLICY

NESI researchers will also study energy policy. The Energy Policy Center is devoted to developing and establishing policy recommendations and advising legislators and decisionmakers on energy policy, economics and future trends for local and state governments and corporate sectors.

“Progress toward energy sustainability is gradual such that a different mix of energy supply alternatives will evolve with time,” says Gasem, who will play a key role in this center as well. “The strategy will be to ensure that we meet our energy supply targets in quantity, quality and reliability during the periods of transition between energy

sources. It is imperative that we rise to the challenge of meeting energy demand while preserving the environment.”

EPC researchers will conduct analyses to support their specific forecasts and recommendations relating to the energy supply agenda. The group will produce an annual report assessing sustainable energy progress, policy responses, environmental impacts, conservation efforts, and economic costs and benefits. The report will include an annual forecast of needed policy changes, likely technological advances, and environmental and economic impacts.

24 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

PROMOTING CONSERVATION

Expert analyses have identified energy conservation – achieved by decreasing energy consumption and then efficiently managing energy usage – as the most immediate practical measure for reducing the nation’s energy footprint. Practical energy solutions in conservation will have a direct impact on the environment, energy economics and security. Researchers in the institute’s Energy Conservation and Management Center will help develop effective energy management strategies, products and technologies, and computer simulation capabilities to enhance energy conservation and management through a variety of programs. Their scientific and engineering efforts will complement comparable efforts in the field aiming to move the U.S. toward more energy-efficient buildings, industrial platforms and transportation systems.

LegacyLAND GRANT

COMMERCIALIZING DEVELOPMENTS BEYOND RESEARCH

The Energy Technology Center is the commercialization arm of the National Energy Solutions Institute. Owned and operated by OSU’s University Multispectral Laboratory, the ETC will not own intellectual property but will conduct collaborative research and development and facilitate the rapid commercialization of new energy technologies created in the institute and elsewhere through affiliated corporate entities using proven methodologies to drive integration and optimization initiatives. The ETC’s current focus is on electromechanical battery systems for energy storage, says Dr. Web Keogh, director of the UML, and on biomass conversion technologies for renewable, sustainable and green energy sources.

Each of institute’s centers will include significant education and training components in order to provide the industry with the future workforce in these new energy sectors, as well as providing continuing education for the existing energy workforce, McKeever says. Education activities will include classroom and field work, research and laboratory opportunities, and industry internships and collaborations.

“The goal is to produce the required educated workforce armed with the latest knowledge of renewable, sustainable and clean energy systems and their integration with fossil fuels for the energy future of the state, nation and world,” McKeever says.

The researchers will collaborate with workforce training programs at OSU-OKC for wind and at OSU-IT in Okmulgee for compressed natural gas. McKeever believes the comprehensiveness of the institute will position OSU as a leader in modern, cuttingedge energy research and education.

kelly green

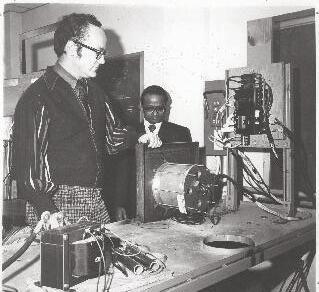

ENGINEERING

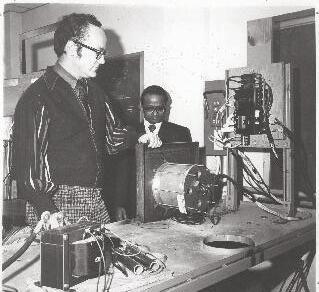

In the 1970s, H. Jack Allison of electrical engineering studied the energy needs and potential in Sri Lanka, an island off the tip of India. Supported by a grant from the United Nations, he tried out windgeneration techniques there developed at the OSU Engineering Energy Laboratory (EEL). “The energy systems we build there,” Allison said, “will not be based on fossil fuels. The U.N. people feel alternatives are going to have to be used by everybody someday, so why not set the example while you can.”

In 1975, National Geographic reported on the work of the EEL and highlighted the efforts of William L. Hughes (pictured right), Allison and Ramachandra G. Ramakumar (left and right in left photo). That same year Hughes was named chairman of an ad hoc committee appointed by the National Academy of Science to develop a comprehensive report on alternate sources of energy for developing nations. There was a pressing need by Allison, Hughes and others at the EEL to research not only wind but other alternate forms of energy as well. Hughes’ research on wind energy attracted national and international attention. He had worked on energy conversion and storage problems for about 15 years, long before the energy crisis became a burning national issue.

Energy remains a focus of research in OSU’s College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology, and Dr. Ramakumar is still very involved in the efforts serving as director of the EEL. The energy program has attracted over $3 million in external funds during the past 50 years, including support from electric utilities, the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, United Nations and the U.S. Air Force. Areas of focus include: hydrogen production, utilization and storage; fuel cells; wind and solar resources; and the impact of distributed photovoltaic systems on the utility grid.

ph O t O / Special cO llecti O n S , OSU l ibrary 25 Research at Oklahoma State University • research.okstate.edu

phOtO / Special cOllectiOnS, OSU library

Finance professors Betty Simkins and Antonio Camara develop a model to measure bankruptcy risk.

Markets don’t lie. Probably. That’s part of the Efficient-Market

No matter what manner of shenanigans, skullduggery or tomfoolery corporations engage in, the market knows and sees all. Prices reflect that knowledge. Stock prices. Option prices. Et cetera. Theoretically.

Realizing that, two OSU finance professors, Betty Simkins and Antonio Camara, have taken a popular way to price options – the positions people take when they buy stocks – and tweaked it to measure bankruptcy risk.

They compared their results against cases of big bankruptcies during 2007 and 2008 financial crises and found their system was as accurate as Moody’s KMV, the biggest Wall Street credit rating system, and sometimes beat the popular rating method, Simkins says.

Also, in every case it was more accurate than methods used by credit rating agencies. They published their results in a 2011 issue of the Journal of Banking and Finance.

Hypothesis.