Breck School Advanced Science Research Journal

The Breck Advanced Science Research Program is the capstone course of the Breck science curriculum. This program gives students who are passionate about science and engineering the opportunity for an authentic, high-level summer research experience in collaboration with research professionals in universities, colleges or businesses.

Following the summer research component of the program, students participate in a year-long science research seminar class where they write and submit formal research papers and project presentations to the Twin Cities Regional Science Fair, Regional Junior Sciences and Humanities Symposium and the Minnesota State Science and Engineering Fair, with some students continuing on to the National Junior Sciences and Humanities Symposium or the International Science and Engineering Fair. In addition, Advanced Science Research students participate in a formal seminar at Breck where they present their work to family members, research advisors, and peers.

More information about the Breck School Advanced Science Research Program is available on our website: breckschool.org/asr

Dr. Kati Kragtorp, Director Advanced Science Research Program

Music and the Mind (Year Two)

the Intersection of Musical Proficiency and Reading Readiness

Noah DeMichaelis

Find Your Way

Design and construction of a multiple T-maze to assess spatial memory

Abigail Endres and Vivian Kinney

Problematic Packaging

Optimizing a method for dissolving alginate sheaths from cell fibers for 3D bioprinting

Anna Iordanoglou

Collision-Free Commutes

Designing a Blind Spot Detection System for Cyclists Using an Ultrasonic Sensor and Computer Vision

Noah Getnick and Evan Johnstone

Catching the Culprit

Western Blot Analysis of the Relationship Between Alzheimer’s Related Proteins

Aβ*56 and ΔTau303 in APP Transgenic Mice

Matthew Manacek and Samantha Dvorak

Deciphering DUX4

Is transient expression of the DUX4 gene sufficient to cause muscular dystrophy?

Corinne Moran

Refining the Ring Engineering nanobodies for a faster path to CSAN cancer immunotherapy

Charlotte Vasicek and Michael Setterberg

The Microplastic Butterfly Effect

Effects of dietary microplastic on survival and fitness of Cabbage White Butterflies (Pieris rapae)

Elin Wellmann

Use your mobile phone to scan the QR code included in each article to watch videos of our students’ presentations.

Noah DeMichaelis

Introduction

Reading is an essential skill for a successful future, and falling behind is catastrophic. The social ills of illiteracy emerge in a variety of ways, some seemingly unintuitive For instance, crime is significantly associated with illiteracy: 85 percent of juvenile delinquents are functionally illiterate (The Economic & Social Cost of Illiteracy, 2018). Additionally, illiteracy can impact health, since illiteracy limits a person’s ability to understand health information and increases the likelihood of high-risk sexual behaviors (The Economic & Social Cost of Illiteracy, 2018) Furthermore, the negative consequences of illiteracy are not strictly personal but can have large cumulative effects on society According to a 2018 report from The World Literacy Foundation Illiteracy costs the global economy 800 billion pounds (965 billion dollars) a year (The Economic & Social Cost of Illiteracy, 2018).

Research indicates a powerful association between rhythmic skills and pre-literacy in young children. In one study, preschoolers who were capable of mimicking a presented beat also exhibited greater proficiency in various preliteracy skills. These ‘synchronizers’, had greater phonological awareness (the ability to perceive and utilize spoken language), auditory short-term memory, and were quicker at naming presented colors or objects (Bonacina et al., 2018) These are all vital pre-literacy characteristics, and this data points towards an association between rhythmic ability and literacy skills The ability to keep a beat has also been shown to predict neural speech encoding in preschoolers. Beat synchronization reflects greater neural precision to temporal cues in speech (Woodruff Carr et al., 2014), which is associated with language acquisition and early

literacy Both adults and children who struggle to synchronize have deficits in neural encoding of sound and consequently reading ability (Kraus & Chandrasekaran, 2010)

Akin to the relationship between synchronization and reading, some research has also established a relationship between pitch and similar reading skills However, there is generally less research into this relationship, and often the research that exists presents a nuanced relationship Within the same study, among the two groups measured (third graders and daycare participants), pitch perception only correlated with phonemic awareness in the younger group, while rhythmic skills remained the strongest predictor of phonological and phonemic awareness (the ability to use and manipulate sounds in spoken language) among both groups (Steinbrink et al , 2019) Another study observed that children with learning disabilities (third through fifth graders) had poor pitch and rhythm proficiency as compared to children without learning disabilities (Lu et al , 2020) Indeed, many studies have seen a relationship between pitch-related musical skills and reading performance in children with dyslexia in particular (Fernández-Prieto et al., 2016; Foxton et al , 2003; Lu et al , 2020; Santos et al , 2007) It is likely that associations, if present, might only emerge in certain age ranges. Most studies demonstrating an association between pitch skills and reading skills tend to focus on younger children (Galicia Moyeda, 2017; Lamb & Gregory, 1993) However, Foxton et al (2003), observed a similar relationship between specific pitch-related skills and reading performance among an older age range (19-24 years old)

Whether or not pitch is a factor, research suggests that musical training could improve reading performance, while musical education

represents a potential remedy (Bonacina et al., 2021) Contrary to popular conception, musicality is not immutable Synchronization ability is shown to improve with practice. Musical training enhances auditory-motor development and is associated with superior reading ability (Steinbrink et al., 2019). Similarly, in one study, training in tonal-based musical training improved reading performance (Galicia Moyeda, 2017).

Rock ‘n’ Read is a Minnesota-based nonprofit founded to use music as a tool to strengthen reading. On the understanding that musical ability can be taught and that it presents benefits in other academic areas, Rock ‘n’ Read retrofitted city buses to include computers with ‘Tune Into Reading’ (a music-based educational software) to teach children to read through musical intervention. Through working with the program, participants saw significant gains in reading ability (Rock “ n ” Read Project, n d ) Motivated by such notable results, the organization decided to take their work even further and launched the “Zap the Gap'' campaign. Through their campaign, the Rock ‘n’ Read is emphasizing musical ability at very young ages (prenatal to 5 years old), arguing that addressing current shortfalls in reading ability through musical training can prevent deficits from becoming more pronounced over time To aid in this effort, Rock 'n’ Read produced a free musical fitness assessment (Musical Fitness Assessment, n d ) The musical fitness assessment measures proficiency in beat synchronization, and singing in tune, among other musical skills This assessment provides a simple, consistent measure of musical ability to help identify musical deficits in young children.

In the first year of this study (2022), I analyzed three sets of data collected from first-grade participants at Breck School, a suburban, independent school near Minneapolis, Minnesota: a parent/guardian survey on each participant’s past musical training, an assessment of their musical skills, and their most recent phonemic ability scores. Phonemic ability was determined through the Heggerty Guide-

lines for Scoring the 1st Grade Baseline Phonemic Awareness Assessment (The National Reading Panel Report, 2000) This phonemic awareness assessment tests rhyme production, onset fluency, blending phonemes, isolating final sounds, segmenting words into phonemes, isolating medial sounds, adding additional phonemes, deleting additional phonemes, and substituting initial phonemes The Musical Fitness Assessment covered skills including synchronization to a beat, syllable perception with a song, and singing in tune I found that pitch perception, along with syllable perception, had the highest correlation with phonemic awareness Early exposure to music education was linked with improved musical fitness, however, this was due to the association between increased early musical education and synchronization, while no such association was seen with pitch-related skills This was likely why there was no association between musical exposure and phonemic awareness. Exposure to music education was only linked with synchronization, not pitch, while only pitch, and not synchronization, was linked with phonemic awareness

These results were intriguing, but they also posed some new questions. The associations I noted between student scores on the Heggerty Phonemic Awareness Assessment and their pitch skills might have been an artifact of the specific type of reading-readiness assessment I looked at and not representative of a broader association between reading and pitch skills. The Heggerty Phonemic awareness assessment explicitly focuses on speech sounds, as opposed to written text, which may lead to it developing a stronger relationship with pitch, where no such relationship exists with reading as a whole It was also possible that the results observed in the 2022/2023 study may be a product of a small sample size (29) Given a larger sample size, previous trends could disappear, or new trends could develop.

In this second year of research, I investigated whether the Musical Fitness Assessment data collected in 2022 (year 1 of this study) correlates

with other reading-related measurements. Specifically, I investigated whether musical proficiency correlates with other reading metrics Additionally, I looked at what aspects of musical proficiency (pitch skills, rhythm skills, musical experience) drove this correlation and if this correlation was different than the relationship previously observed with the Heggerty Phonemic Awareness Assessment I repeated the assessment with a second cohort of first-grade participants to determine whether the relationship between pitch-related skills and reading proficiency remained consistent. I also developed and included additional measures of pitch-related skills in the Musical Fitness Assessment to determine whether these also correlated with reading readiness measures

2022/2023

In the spring of 2023, I obtained additional reading-related data from the children who participated in the first year of this study. An additional consent form was sent out to each parent or guardian of a first-grade student who had participated in the initial study. In total, 25 parents permitted us to access their children’s additional testing data A reading specialist collected data using four different assessments from the Formative Assessment System for Teachers (FAST): sight words, nonsense words, word segmentation, and Curriculum-Based Measurement (CBM). The sight word assessment tests the ability of first graders to read the 150 most prominent English words. The word segmenting portion of the test asks participants to separate spoken words into individual sounds In the nonsense word test, participants are asked to read as many phonetically regular nonsense words as possible in one minute The CBM asks participants to read as many words as possible from three texts without pictures in one minute. Sight words, nonsense words, and word segmentation were measured in the fall of 2023, while all four scores were collected in the spring of 2023

Using the online software, DataClassroom (Temple & Reedy, Aaron, n d ), I used linear regression to compare each new reading assessment score (sight words, word segmenting, nonsense words, and CBM) with last year’s data on the level of musical exposure and musical fitness assessment scores. I used the Mann-Whitney U Test to compare individual musical fitness skills with the new reading assessment scores.

The research participants in the 2023/2024 cohort were first-grade participants (ages 6-7) from Breck School in Golden Valley, MN Breck School is a suburban, independent, pre-K through grade 12 college preparatory school. This study represents an age, gender, and racial/ethnic composition representative of the first-grade student body at this institution. This study did not include any otherwise listed vulnerable populations An introductory email containing a link to an online Google Form survey was sent to all parents/guardians of 2023/24 first-grade participants at Breck School in the fall of 2023, inviting them to participate in the study Parents were recruited using printed flyers, email invitations, and tabling at school events. Consent and assent were collected through a Google form sent to the parents and guardians of the 2023 first-grade class

A link to an online Google Form survey was sent to all parents/guardians of incoming 2023/24 first-grade participants at Breck School in Golden Valley, MN Beginning with the consent and assent forms, the survey asked for information about their child, including years at Breck School, current age, amount, and type(s) of musical education before and after kindergarten. After parents/guardians concluded the survey, the data was anonymized by my mentor before being provided to me

Each participant was administered the Rock ‘n’ Read Basic Musical Fitness Assessment (Musical Fitness Assessment, n d ) with additional tone-discrimination questions. Participants were tested individually at their school during scheduled music class time or during scheduled morning meeting time by a member of the school faculty The musical assessment asked children to perform specific tasks including synchronization to a metronome, patting syllables of words with a song, vocally matching pitch, and singing in tune For the rhythm portion of the assessment, participants patted any relevant beats on their lap to provide more tactile stimuli statistically shown to improve rhythmic ability in children (Kuhlman & Schweinhart, 1999)

For this second year of data collection, I designed a tone-discrimination task, based on a previously published tone-discrimination task (Lu et al , 2020) and the Primary Measure of Music Audiation by Edwin E. Gordon (Primary Measures of Music Audiation, n.d.). Participants listened to a series of tone pairs and were asked to determine whether the pitch increased, decreased, or remained the same. The tone discrimination portion of the assessment had three sections that progressed in difficulty. Each section featured a question where the pitch increases, one question where the pitch decreases, and one question where the pitch remains the same. Pitches in the first section began on a middle C and increased or decreased by two whole steps. Pitches in the second section began with an E and only increased and decreased by one step Pitches in the third section began on a G and changed by only a half step. To protect anonymity, scores were de-identified before being provided to me

In the fall of 2024, the Breck school reading specialist collected reading assessment scores from the first-grade class. These reading scores included some of the same reading metrics collected in the 2022/2023 first-grade class: word segmenting, sight words, and nonsense

words. Notably, the Curriculum-Based Measurement (CBM) and the Heggerty Phonemic Awareness assessments were not administered in the fall of 2023.

Using the online software, DataClassroom, I assessed the relationship between the level of musical exposure, reading performance, and musical proficiency of the 2023/2024 first-grade class. I used linear regression to compare each new reading assessment score (sight words, word segmenting, and nonsense words) with scores and combinations of scores from the Musical Fitness Assessment These included Musical Fitness Assessment total, Pitch, Pitch + Syllables, and Synchronization + Syllables. I used the Mann-Whitney U Test to compare individual musical fitness categories with new reading assessment scores.

Additional fall testing data - 2022/2023 (Year I) cohort

In the additional testing data collected in the Fall of 2022, syllable scores had a significant, positive correlation with nonsense words score (p < 0.05; Table 1), but no other significant correlations were observed between fall FAST scores and musical fitness assessment scores Total Heggerty score had a significant positive correlation with nonsense words scores (p < 0 05; Table 1) but did not correlate with the other two reading assessments.

Additional spring testing data - 2022/2023 (Year I) cohort

In the additional testing data collected in the Spring of 2023, Musical Fitness Assessment total score did have a significant positive correlation with each FAST metric collected in 2023 (p < 0.05). Similarly, combined pitch matching and syllable scores had a significant correlation with Total Heggerty Score There was a significant positive correlation between Musical Fitness Assessment total score and all FAST assessment scores (p < 0 05; Table 2)

Table 1. Summary of Mann-Whitney, or (*) linear regression statistical analysis, of additional FAST fall testing data from 2022/2023 (Year I) cohort. Relationships with p < 0.05 are highlighted in yellow.

Table 2. Summary of Mann-Whitney, or (*) linear regression statistical analysis, of additional FAST spring testing data from 2022/2023 (Year 1) cohort. Relationships with p < 0.05 are highlighted in yellow.

Combined pitch score was significantly, positively related to the score on the sight words assessment (p < 0 05; Table 2) This was the only type of reading-related score collected in the spring of 2023 with a significant positive correlation with pitch performance in isolation (p < 0.05; Table 2). Similarly, beat- keeping scores in isolation only had a significant positive correlation with word segmenting

Sight word scores collected in the Fall of 2022 correlated significantly with sight word scores collected that Spring in 2023 (p < 0 01) Similarly, nonsense word scores collected in the Fall of 2022 correlated significantly with nonsense words collected in the Spring of 2023 However, word segmenting scores collected in the Fall of 2022 did not correlate significantly with word segmenting scores (p = 0 98)

2023/2024 (Year II) cohort comparison to 2022/2023 (Year 1) cohort

Compared to year one of this study, the number of participants in year two increased from 29 to 34 (Table 3) The percentage of students who received in-school pre-K musical education was 72% in year one compared to 38% in year two

This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Similarly, the average level of musical exposure was 1 6 in year one (2022/2023) and 1.2 in year two (2023/2024); a statistically significant difference (p < 0.04; Table 3). There were no significant correlations between performance in any musical skill metric or level of musical exposure with scores on assessments of sight words, word segmenting, or nonsense words in the fall data from the 2022/2023 (Year I) cohort (data not shown).

Performance on the tone discrimination task ranged from a minimum of 11 to a maxi- mum of 18 out of 18 total possible points, with 47% of students earning full points on the task (Table 4). There was a significant correlation between performance on the second-tone-high question of the tone discrimination assessment and total musical fitness assessment score (p < 0.01). However, this significance was due to an individual participant who did not correctly identify any of the second-tone-same questions. When this outlier was removed, the relationship was no longer significant.

Additionally, there was a significant correlation between total musical fitness assessment score and performance on the one-step change portion of the tone discrimination activity (p < 0.03). However, this significance was due to the same individual outlier When the outlier was removed, the relationship was no longer significant There were no other significant correlations between performance on the tone discrimination task and any section of the musical fitness assessment There was no significant relationship between the tone discrimination task score and any of the FAST scores

Table 4. Summary of Performance on Tone Discrimination Activity

Mean Score +/- s.d (max score) % of subjects answering correctly

Total 15 9 +/- 2 7 (18) 47

Second tone Low 5.1 +/- 1.3 (6) 53

Second tone High 5.1 +/- 1.4 (6) 58

Second tone Same 5.6 +/- 1.2 (6) 88

Two-step change 5.5 +/- 0.9 (6) 74

One-step change 5.3 +/- 1.0 (6) 56

Half-step change 5.1 +/- 1.3 (6) 62

In the first year of this study, I found a significant, positive correlation between musical fitness and performance on the Heggerty Phonemic Awareness Assessment, with a highly significant positive correlation between combined scores for pitch perception and syllable awareness and the Heggerty score In this second year, I obtained and analyzed additional data from this cohort, which revealed that sight words, word segmenting, and nonsense

Noah DeMichaelis

word scores collected in the fall from this cohort did not significantly correlate with musical fitness assessment scores (except for syllable perception) or level of musical exposure. In addition, sight words, word segmenting, and nonsense word scores collected in the fall of 2022 did not correlate with Heggerty Phonemic Awareness scores collected in the fall However, FAST scores collected in the spring of 2023 had a significant, positive correlation with musical fitness scores, fall Hegg erty scores, and level of musical exposure Of the specific skills assessed in the musical fitness assessment, combined pitch and syllable scores had the strongest relationship with each aforementioned reading metric. Similar to the results for FAST reading scores collected in the fall semester for the year one cohort, in the year two cohort there was no association between musical proficiency and any of the fall FAST scores For the year two first-grade cohort, the Heggerty Phonemic Awareness assessment had been phased out by first-grade faculty in favor of the FAST assessment For this reason, it was not possible to compare the year one and year two cohorts regarding this metric This leaves a piece of potential data missing for this year’s study Similarly, it is too early to collect spring scores using the FAST assessment for the year two (2023/2024) cohort So, it remains to be seen whether the relationship observed between fall musical fitness assessment scores and spring FAST scores in the year one cohort repeats with the year two cohort.

This difference in the relationship between musical fitness assessment scores and FAST scores collected in the fall versus the spring semesters may stem from insufficient differentiation of FAST scores collected in the fall. Students learn to read at different rates, so over the school year, a greater range of FAST scores will develop The relationship between musical proficiency and reading readiness may develop over a school year because children themselves are developing

Performance on the new pitch discrimination questions was very high for the year two

(2023/2024) cohort, indicating the task itself was likely too easy for first-grade students This led to insufficient differentiation between first-grade participants to yield statistically significant results when compared with FAST assessment scores, or the musical fitness assessment scores, once a single outlier was removed. For this reason, in future assessments, it would be necessary to increase the challenge of this activity to gather more highly differentiated data.

In future investigations, it will be especially interesting to investigate how associations with different musical areas (pitch versus synchronization) and reading proficiency evolve as our tested population matures or as new participants are added. It may also be worthwhile to investigate whether musical intervention could improve reading proficiency, especially among the participants with the lowest scores on the FAST reading assessments. This investigation provides deeper insights into the dynamic between music and reading which may be useful in informing educational practices to help students best develop reading skills

Bonacina, S , Krizman, J , White-Schwoch, T , & Kraus, N (2018) Clapping in time parallels literacy and calls upon overlapping neural mechanisms in early readers: Clapping in time parallels literacy Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1423(1), 338–348 https://doi org/10 1111/nyas 13704

Bonacina, S , Krizman, J , White-Schwoch, T , Nicol, T , & Kraus, N (2021) Clapping in Time With Feedback Relates Pervasively With Other Rhythmic Skills of Adolescents and Young Adults Perceptual and Motor Skills, 128(3), 952–968. https://doi org/10 1177/00315125211000867

Fernández-Prieto, I , Caprile, C , Tinoco-González, D , Ristol-Orriols, B , López-Sala, A , Póo-Argüelles, P , Pons, F , & Navarra, J (2016) Pitch perception deficits in nonverbal learning disability Research in Developmental Disabilities, 59, 378–386 https://doi org/10 1016/j ridd 2016 09 011

Foxton, J. M., Talcott, J. B., Witton, C., Brace, H., McIntyre, F., & Griffiths, T D (2003) Reading skills are related to global, but not local, acoustic pattern perception Nature Neuroscience, 6(4), 343–344 https://doi org/10 1038/nn1035

Galicia Moyeda, I X (2017) Influencia de un entrenamiento en discriminación de estímulos tonales en la conciencia fonológica de niños preescolares Estudio piloto / Influence of tonal stimuli discrimination in the phonologic awareness of preschool children. Pilot study RIDE Revista Iberoamericana Para La Investigación y El Desarrollo Educativo, 8(15), 529–547 https://doi org/10 23913/ride v8i15 309

Kraus, N , & Chandrasekaran, B (2010) Music training for the development of auditory skills. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(8), 599–605 https://doi org/10 1038/nrn2882

Kuhlman, K , & Schweinhart, L J (1999) Timing in Child Development High/Scope Educational Research Foundation

Lamb, S J , & Gregory, A H (1993) The Relationship between Music and Reading in Beginning Readers Educational Psychology, 13(1), 19–27 https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341930130103

Lu, H , Zhang, K , & Liu, Q (2020) Reading fluency and pitch discrimination abilities in children with learning disabilities Technology and Health Care, 28, 361–370 https://doi org/10 3233/THC-209037

Musical Fitness Assessment (n d ) Rock “n” Read Project Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www rocknreadproject org/musical-fitness-assessment

Primary Measures of Music Audiation (n d ) https://www giamusic com/store/resource/primary-measures-of-mu sic-audiation-kgrade-3-complete-kit-pmma-instrumentaccessory-g 2242k

Rock “n” Read Project (n d ) Rock “n” Read Project https://www.rocknreadproject.org/new-programs

Santos, A , Joly-Pottuz, B , Moreno, S , Habib, M , & Besson, M (2007) Behavioural and event-related potentials evidence for pitch discrimination deficits in dyslexic children: Improvement after intensive phonic intervention Neuropsychologia, 45(5), 1080–1090 https://doi org/10 1016/j neuropsychologia 2006 09 010

Steinbrink, C , Knigge, J , Mannhaupt, G , Sallat, S , & Werkle, A (2019) Are Temporal and Tonal Musical Skills Related to Phonological Awareness and Literacy Skills? – Evidence From Two Cross-Sectional Studies With Children From Different Age Groups Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 805 https://doi org/10 3389/fpsyg 2019 00805

Temple, D , & Reedy, Aaron (n d ) DataClassroom DataClassroom. Retrieved November 20, 2023, from https://about dataclassroom com

The Economic & Social Cost of Illiteracy (2018) World Literacy Foundation https://worldliteracyfoundation org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/T heEconomicSocialCostofIlliteracy-2 pdf

The National Reading Panel Report. (2000). https://heggerty org/Phonemic-awareness-research/

Woodruff Carr, K , White-Schwoch, T , Tierney, A T , Strait, D L , & Kraus, N (2014) Beat synchronization predicts neural speech encoding and reading readiness in preschoolers Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(40), 14559–14564 https://doi org/10 1073/pnas 1406219111

Endres and Vivian Kinney

Abigail Endres and Vivian Kinney

Introduction

Spatial memory refers to the ability to store and manipulate spatial information and it allows one to create a mental representation of one’s surroundings (Johnson & Redish, 2007; Morellini, 2013) This representation of space is what allows individuals to navigate through space. Spatial memory is used for everyday tasks such as navigating home through a familiar city Spatial memory is also impacted by neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) The initial stages of AD include many spatial memory deficits, such as spatial disorientation. In fact, over 60% of AD patients suffer from spatial memory deficits (Silva & Martínez, 2023). Understanding spatial memory is integral to comprehending the fundamental mechanisms underlying human cognition

Much research has been conducted on the role of the hippocampus in spatial memory in binding together distributed sites in the neocortex to represent a whole memory (Eichenbaum et al , 1999). It is understood that the sequential firing of the hippocampus plays an important role in encoding spatial information Place cells, located within the hippocampus, associate a landmark or location with a cell to create a representation of space (Silva & Martínez, 2023) Still, there is much that is not known about how different brain regions interact and coordinate their activity during the process of spatial memory, due to the sheer complexity of the brain (Robin et al , 2015)

One way that researchers study spatial memory in mice is through a behavioral paradigm called the T-maze The T-maze requires the mouse to navigate its surroundings, testing the mouse’s ability to retain spatial information (Deacon & Rawlins, 2006) A basic T-maze consists of a

stem that guides the mouse forward to the decision point where the mouse is forced to choose between a left or right turn The mice are trained to learn that one choice is programmed with a reward After a sufficient amount of training, the mice are then given full, free choice between the two sides. The choice the mice make is then recorded In each trial, the mouse loops through the T-maze multiple times so that an adequate amount of data is collected. However, since this maze is not continuous, the mouse has to be physically removed from the maze, which causes the mouse to become stressed The single decision point in a standard T-maze limits the complexity of the maze and fails to properly challenge the mouse.

Most work in understanding brain region connectivity is limited to head-fixed mice, which does not adequately model what is happening in the brain of a mouse freely moving around in its environment A recent advancement in brain imaging technology is the development of cortical-wide imaging devices for mice, called the “Mini-MScope” (Donaldson et al , 2022; Rynes et al., 2021). These devices are miniaturized head-mounted imaging microscopes that allow for the recording of cortical-wide activity in freely behaving mice that have been genetically modified to possess the Thy1-GCaMP6f gene (GCaMP) The GCaMP gene activates a green fluorescent light when neurons fire, allowing for the recording of neural activity

We developed a modified T-maze to analyze cortical-wide activity, using Mini-MScope technology, as mice completed a task that challenged their spatial memory. We included two T decision points in our maze to observe differences in brain activity and connectivity during spatial memory tasks. The maze was

made to be continuous to allow for multiple, sequential trials This maze can be used as a tool to gain a deeper understanding of spatial working memory.

Materials and Methods

Maze design and prototyping

The initial maze design was developed using the Solidworks (Dassault Systemes) computer-aided design (CAD) The first three prototypes were constructed with cardboard and duct tape. 12 in. by 24 in. acrylic sheets were cut using a laser cutter to construct the maze and a hand file was used to file down any sharp edges. To create longer pieces, holes were drilled into the acrylic sheets and 3D-printed pieces were used to bolt sheets of acrylic together to create the desired length. Other 3D-printed pieces were created to act as the joints in the maze The doors were designed on Solidworks and were then 3D-printed. Servo motors were mounted on the walls of the maze using 3D-printed mounts 3D-printed doors were then attached to the servo motors. Infrared beam break sensors were also used in the construction of the final maze A combination of a syringe, tubing, and a DC motor were used to create a water dispenser. The motors and infrared beam break sensors were connected, controlled, and powered by an Arduino Due and an Arduino Mega system. The maze’s electronic system was created through the use of soldering equipment to connect the electronic components to power.

Mouse husbandry and handling

All mice used in this study we re housed in and handled by the Biosensing Biorobotics Lab in the University of Minnesota’s Mechanical Engineering Program according to an approved IACUC procedure. The authors were not in direct contact with the mice at any time Five male, Thy1-GCaMP6f, mice were used for their genetically modified calcium indicators that are expressed in layers 2, 3, and 5 of the cortex The mice had been fitted with a clear ‘cap’ (the e-SeeShell) that allowed for the observation of brain activity using the Mini-MScope Mice

were surgerized for previous research that had since finished and were not prepared specifically for our research

To increase motivation during the behavioral task, the mice were water-restricted using a procedure already in place for other research being performed in the lab. All water restrictions performed complied with IACUC guidelines. Mice were housed in a 14-hour light /10-hour dark cycle. For this project, the effects of water restriction on a navigation task were studied in mice by looking at brain activity and animal behavior. RAR staff were notified of mice under water restriction and daily body weight was taken for each mouse under water restriction protocols. Trained researchers closely monitored water restriction effects, which was conducted over a 10-day period, by examining mouse locomotion and posture during daily interaction sessions.

The dimensions of maze design I were 40 in. by 34 in and consisted of two basic T decision points that led to an outer path that contained a reward on the lateral sides (Figure 1). A door was placed on the left side of the first T to force a right turn The initial plan was to have cues to signal what direction the mice should turn at the second T The second T held the central choice zone, which was the point where the mice made the turn that would lead them to the reward. Doors at either end of the secon d T would close after the mice had made their final choice When the mice move along the outer path, they would be led back to the starting point and continue to cycle through the maze

Abigail Endres and Vivian Kinney

Figure 1. Annotated image of design I. The Solidworks design of the initial prototype, including annotations of electronic elements of the maze. Figure by authors.

A prototype of the first maze design was constructed out of cardboard (Figure 2) After consultation with researchers, it appeared that the maze was too short. An increase in the length of the maze was recommended because if the mice exert more energy completing the trials, they are more likely to pause at the central choice zone

2. Cardboard prototype of maze design I. An image of the maze prototype I which was constructed out of cardboard. Figure by authors.

The dimensions of maze design II were 36 in. by 36 in and consisted of two basic T decision points that led to a winding outer path that

contained a reward on the lateral sides (Figure 3) The door by the first T decision point in maze design I was replaced by a wall After consultation with researchers, it appeared that this maze design was too complex The winding outer path would lead the mice to become disoriented and unable to complete the maze.

Figure 3. Annotated image of maze design II. The Solidworks design of the second prototype, including annotations regarding the start point Figure by authors

The dimensions of maze design III were 72 in by 72 in and consisted of two basic T decision points that led to a curved outer path that extended through the length of the entire maze and contained a reward on the lateral sides (Figure 4). After consultation with researchers, it was concluded that this maze design would likely work My partner and I then determined that we should first scale the maze down before prototyping to be mindful of the space and material that would be used

Figure 4. Image of maze design III. The Solidworks design of the third prototype. Figure by authors.

Maze Design IV

The dimensions of design IV were 48 in. by 48 in and consisted of two basic T decision points that led to an outer path that extended through the length of the entire maze and contained a reward on the lateral sides (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Image of maze design IV. The Solidworks design of the fourth prototype Figure by authors

Maze Prototype IV

A prototype using the dimensions of the fourth maze design and the curved element of the third maze design was constructed out of cardboard (Figure 6). After consultation with researchers, it was recommended that we increase the length of the first T’s choice paths to ensure that the mice would be sufficiently challenged at that decision point

Figure 6. Cardboard prototype of maze design IV. An image of the maze prototype IV which was constructed out of cardboard Figure by authors

Maze Design V

The dimensions of maze design V were 48 in by 60 in. and consisted of two basic T decision points that led to a winding outer path that contained a reward on the lateral sides (Figure 7). After consultation with researchers, it was recommended that we make the maze more symmetrical to ensure that the distance traveled wouldn’t influence the direction the mice would choose

Abigail Endres and Vivian Kinney

Figure 7. Image of maze design V. The Solidworks design of the fifth prototype. Figure by authors.

Maze Design VI

The dimensions of maze design VI were 48 in. by 60 in and consisted of two basic T decision points, with a sharp turn in between, that led to a winding outer path that contained a reward on the lateral sides (Figure 8)

Figure 8. Image of maze design VI. The Solidworks design of the sixth prototype Figure by authors

Maze Prototype VI

A prototype of the sixth maze design was constructed out of cardboard (Figure 9). Researchers directed untrained and unmotivated mice through the cardboard maze and determined that the maze was effective. It was recommended that unnecessary gaps in the maze be removed to limit the material used in the final design.

Figure 9. Cardboard prototype of maze design VI. An image of the maze prototype six which was constructed out of cardboard. Figure by authors.

Final Maze Construction

The final maze was constructed using ¼ inch white acrylic The maze dimensions were 39 in by 56 5 in and the walls were 6 in high (Figure 10). The acrylic pieces were connected with 3D-printed joints and some boards were elongated with the use of 3D-printed pieces and bolts. The maze contained five servo motor-controlled doors that were activated through the use of infrared (IR) beam break sensors, and one water-reward station.

Figure 10. Final maze. An image of the final maze Figure by authors

Maze Route

At the start of each trial, a mouse was placed at the first T and then directed to complete the maze (Figure 11) The first T decision point the mice encountered required them to make a right turn to continue through the maze. Once the mice had made the right turn, they entered the stem of the second T At the second T, the mice

reached the central choice zone where they were required to make a left or right turn To ensure brain data could be measured as the mice made that choice, the IR beam break sensors closed servo motor-controlled doors This enclosed the mice in the central choice zone to force a pause During that pause, an auditory cue was played to inform the mouse whether to turn left or right After a delay, the doors opened and the mouse was free to move forward. Once the mice had made a choice, t he door would close behind them to help direct them If the mice made the correct choice, they received a water reward from a dispenser Once the mouse had completed their trial, they were returned to their cage.

After an initial behavioral trial, a few issues were identified. First, the mice were not tall enough to trigger the sensors so ramps were 3D-printed. The addition of these ramps led to the placement of the doors to shift to ensure that the doors would not trigger the sensors. To minimize the risk of our electronics burning out, an additional Arduino system was added. To close the doors near the starting point sooner, another sensor was added through the use of a drill and double-sided tape. The auditory cue was removed from the maze due to the observations of researchers who were currently

attempting a similar training process on a different project. Instead, the mice were trained to associate one side of the maze with the water reward The mice were then tested on their ability to identify which turn would lead to a reward

Five transgenic mice were used during an eight-day training and experimentation period. For the first five days, the mice were introduced to half of the maze This time was to help the mice acclimate to the maze and have them associate the right-hand turn with the water reward On days 6 and 7, the mice were introduced to the other half of the maze. The mice were forced to do alternating left and right turns while getting rewarded with water on the right side only. After only a few laps, the mice stopped checking for water on the left side of the maze On the final day, the mice were given full free choice to go left or right. Data was collected regarding whether the mice correctly identified which direction they should turn, as well as the time stamp. On average, the mice made both correct choices 71% of the time, which is close to the ~75% accuracy previously reported for mice running a simple T-maze (Pioli et al., 2014). Overall, this data demonstrates that the maze performed as expected

Abigail Endres and Vivian Kinney

Table 1. Percentage and number of correct decisions made by mice during final trials.

Mouse % of correct choices on T1 (# correct/total trials) % of correct choices on T2 (# correct/total trials) % of both correct

1 86% (6/7) 83% (5/6) 83% (5/6)

2 83% (10/12) 75% (9/12) 67% (8/12)

3 100% (7/7) 86% (6/7) 86% (6/7)

4 86% (6/7) 86% (6/7) 86% (6/7)

5 56% (5/9) 78% (7/9) 33% (3/9)

Limitations and Future Work

The number of mice that participated in the experiment was quite small. A larger sample would allow for more confidence in the results of the experiment Despite rounding the 3D-printed joints, the wires attached to the Mini-MScope still often got caught on the joints In the future, the creation of a joint design that is more flush with the maze could help prevent this problem In addition to the behavioral data collected, the Mini-MScope technology allowed for the collection of brain imaging data. This data is still in the process of being analyzed, but we hope that it will provide significant insight into brain activity. Further iterations of this maze will allow for a better understanding of spatial memory and could eventually lead to earlier diagnosis, disease prevention, and even treatments for memory-altering diseases

We would like to thank Dr Kati Kragtorp for her support throughout the project. We would also like to thank Dr Suhasa Kodandaramaiah, from the Biosensing and Biorobtics Lab at the University of Minnesota, for granting us the opportunity to perform this research Finally, we

would like to thank Daniel Surinach for overseeing us and helping us out throughout our research.

Deacon, R , & Rawlins, J (2006) T-maze alternation in the rodent Nature Protocols, 1, 7–12 https://doi org/10 1038/nprot 2006 2

Donaldson, P D , Navabi, Z S , Carter, R E , Fausner, S M L , Ghanbari, L., Ebner, T. J., Swisher, S. L., & Kodandaramaiah, S. B. (2022) Polymer Skulls With Integrated Transparent Electrode Arrays for Cortex‐ Wide Opto‐ Electrophysiological Recordings Advanced Healthcare Materials, 11(18), 2200626

https://doi org/10 1002/adhm 202200626

Eichenbaum, H , Dudchenko, P , Wood, E , Shapiro, M , & Tanila, H (1999) The Hippocampus, Memory, and Place Cells: Is It Spatial Memory or a Memory Space? Neuron, 23(2), 209–226. https://doi org/10 1016/S0896-6273(00)80773-4

Johnson, A , & Redish, A D (2007) Neural Ensembles in CA3 Transiently Encode Paths Forward of the Animal at a Decision Point Journal of Neuroscience, 27(45), 12176–12189 https://doi org/10 1523/JNEUROSCI 3761-07 2007

Morellini, F. (2013). Spatial memory tasks in rodents: What do they model? Cell and Tissue Research, 354(1), 273–286 https://doi org/10 1007/s00441-013-1668-9

Pioli, E Y , Gaskill, B N , Gilmour, G , Tricklebank, M D , Dix, S L , Bannerman, D , & Garner, J P (2014) An automated maze task for assessing hippocampus-sensitive memory in mice Behavioural Brain Research, 261, 249–257 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2013.12.009

Robin, J , Hirshhorn, M , Rosenbaum, R S , Winocur, G , Moscovitch, M , & Grady, C L (2015) Functional connectivity of hippocampal and prefrontal networks during episodic and spatial memory based on real-world environments: HPC and PFC Connectivity During Episodic and Spatial Memory Hippocampus, 25(1), 81–93 https://doi org/10 1002/hipo 22352

Rynes, M. L., Surinach, D., Linn, S., Laroque, M., Rajendran, V., Dominguez, J , Hadjistamolou, O , Navabi, Z S , Ghanbari, L , Johnson, G W , Nazari, M , Mohajerani, M , & Kodandaramaiah, S B (2021) Miniaturized head-mounted microscope for whole cortex mesoscale imaging in freely behaving mice Nature Methods, 18(4), 417–425 https://doi org/10 1038/s41592-021-01104-8

Silva, A., & Martínez, M. C. (2023). Spatial memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease and their connection to cognitive maps’ formation by place cells and grid cells Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 16, 1082158 https://doi org/10 3389/fnbeh 2022 1082158

Optimizing a method for dissolving alginate sheaths from cell fibers for

Anna Iordanoglou

Introduction

As many as 17 people die per day in the US while waiting for an organ transplant (6 Quick Facts About Organ Donation, n.d.). A lack of donors is only part of the issue. Organs for a transplant must be removed from a recently deceased person and given to the patient awaiting a donor within a certain increment of time 36 hours is the longest the kidney can be preserved before being transplanted, and a heart can only remain outside a human body for around 6 hours (Learn How Organ Allocation Works - OPTN, n.d.). A further issue is that the organs must be undamaged for them to work. Compatibility is another issue, as only one specific tissue type or blood type will work for a given person. If humans could print organs for patients using their tissue, many lives would be saved.

3D bioprinting is a way to artificially create tissue from living cells that can function as natural tissues (Pushparaj et al , 2023) Eventually, these tissues could be used to create organs for transplants In standard 3D printing, layers of filament are stacked on top of each other to create a three-dimensional object. 3D bioprinting works similarly, except it utilizes ‘bioink’ to create the designs and models Bioink is made up of living cells within a matrix of synthetic or natural biomaterials, or a combination of the two (Gungor-Ozkerim et al , 2018). Theoretically, bioink should be able to exactly replicate human tissue (Pushparaj et al , 2023) A 3D bioprinter then uses software to follow a predetermined design, like regular 3D printers, and extrudes the bioink in a pattern that will emulate the structure and function of tissue

Anna Iordanoglou

The 3D Bioprinting Facility at the University of Minnesota is currently developing a protocol to print the Gastroesophageal Junction (Gej). The Gej is the valve between the stomach and esophagus, made up of smooth muscle cells Its role is to stop acid from the stomach from entering the esophagus. If not functioning properly, it can result in inflammation, known as Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD; Kahrilas, 1997). In severe cases, GERD also progresses to esophageal cancer (Vogt & Panoskaltsis-Mortari, 2020). While there are treatments for the symptoms that stem from acid reflux, there is no way to actively repair a damaged Gej and address the root of the problem.

3D bioprinting a Gej is challenging due to the different directionality of the muscle cells in the Gej tissue. There are two main components to the Gej: the muscles that make up the esophagus and the muscles that make up the stomach. These two muscle types in the Gej, also referred to as the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), allow it to serve as a guard ring of muscle, protecting the lower opening of the esophagus (Vogt & Panoskaltsis-Mortari, 2020) Both the lower esophagus and the stomach are made up of smooth muscle cells (Hafen & Burns, 2023; Mittal, 2011) If these smooth muscle cells are not aligned properly, they are unable to create force.

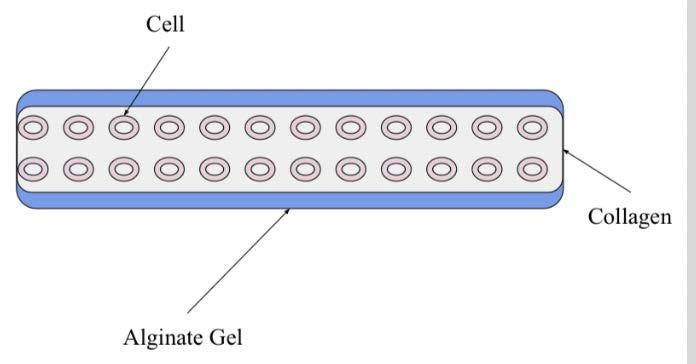

The Panoskaltsis-Mortari lab is developing an aligned smooth muscle cell fiber (ASMSF) that could allow 3D bioprinting of Gej smooth muscle tissue (Panoskaltsis-Mortari, unpublished data) The fiber keeps smooth muscle cells aligned inside of the bioink. The ASMCF is made out of three parts: a sheath of calcium

chloride, a shell of alginate (a polysaccharide derived from brown algae), and a core consisting of collagen and smooth muscle cells (Figure 1) The alginate surrounding the core protects the collagen and cells from shear stress forces while the fiber is being made However, the alginate must be dissolved away from the ASMCF before being put into bioink, as it is not a natural component of human organs The gel around the fiber also needs to be dissolved as quickly as possible, because cells would be harmed in prolonged exposure to non-sterile environments

Figure 1. ASMCF diagram depicting the smooth muscle cells embedded in collagen and surrounded by the alginate gel. Figure by author.

Alginate is a polysaccharide extracted from brown algae. Sodium alginate in particular is made up of two acids, d-mannuronic (M units) and l-guluronic (G units), and it has a linear structure. One of the useful properties of alginate is its ability to interact with cations, mainly calcium, to form a strong gel (Abka-khajouei et al., 2022). This gel can be reverted to a liquid by two methods. One method involves using a calcium chelator a chemical that binds to the calcium in the gel to pull out calcium from the alginate’s structure (New Technique Turns Alginate Solution Into Micron-Scale Gel Patterns Using Light, n.d.). The second method involves an enzyme that degrades alginate by cleaving the glycosidic bonds and produces oligosaccharides (Zhu & Yin, 2015).

The procedure currently used by the Panoskaltsis-Mortari lab to dissolve the alginate in an ASMCF entails exposing the fiber to a 0.4 μg/ml alginate lyase enzyme solution However, full dissolution of the alginate takes an hour,

which is not fast enough to maintain cell viability Alginate lyase degrades alginate by cleaving glycosidic bonds via a beta elimination mechanism (Zhu & Yin, 2015), breaking the alginate down into oligosaccharides Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is a chemical that can also be used to dissolve alginate, because it pulls out the calcium that is used to crosslink alginate and turn it into a gel (Kiviranta et al., 1980). Like alginate lyase, EDTA is nontoxic to cells, and, thus, could be potentially useful in this application (Schubert et al., 2020).

My engineering goal was to determine the most efficient way to dissolve alginate from the ASMCF fiber without harming the cells. I tested the speed and effectiveness of alginate lyase, EDTA, and the combination of the two, in various concentrations, on the dissolution of alginate. Fluorescent dye was incorporated into crosslinked alginate beads to measure the diameter of the beads as the dissolution experiments were in progress. Once the most efficient method of dissolving alginate was determined, a replica of the fiber containing just the alginate on the outside and collagen in the core without cells present was used to gauge a more accurate time frame of when this method would dissolve the actual fiber. Although 0.1 M EDTA was the most efficient way to dissolve the alginate around the mock aligned fiber, EDTA in higher molar concentrations degraded the collagen inside the fiber Encouragingly, even this high level of EDTA was not toxic to the cells. Thus, the combination of alginate lyase and EDTA in a smaller concentration is a superior option.

Initial preparation of alginate beads

A concentration of 1 5% sodium alginate was used for creating the beads. This solution was created by dissolving 15 mg/ml of sodium alginate powder (Sigma Aldrich) into a sterile saline solution (11.237g of NaCl per liter of DI H2O). To ensure the alginate powder was equally distributed among the saline, it was put into a

Initial EDTA and Alginate lyase comparison tests

Alginate lyase was dissolved in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) to create a stock solution of 100x alginate lyase. To ensure a homogenous mixture of DBPS and alginate lyase, the mixture was placed in a centrifuge This solution’s 100x concentration was 0.04 mg/ml of alginate lyase, and it was further diluted in DPBS to make 1x, 2x, and 5x solutions.

EDTA solutions were created at concentrations of 0 1 M, 0 15 M, and 0 2 M This was done by dissolving EDTA (Sigma Aldrich) into saline solution and heating slightly in a glass beaker with a stir bar functioning at medium speed until the EDTA was fully dissolved and the solution appeared clear. EDTA solutions were titrated using 10 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) to achieve a pH range of 7.2-7.4, using a digital pH meter.

combination of alginate lyase and EDTA, also own as Emboclear, was created using blished procedures (Barnett & Gailloud, 11). 5 mg/ml of EDTA in saline was titrated ing sodium hydroxide 10 M (NaOH) and drochloric acid 10M (HCL) to a pH of 7 24. Then, alginate lyase powder was added to e solution at a concentration of 2 mg/ml

r the dissolution tests, 2-3 alginate beads were ded to each well of a 12-well plate, and melapse images were captured of each bead set ery five minutes for two hours for alginate ase tests and Emboclear tests, every two nutes for EDTA tests, until the beads were ssolved This imaging was done using the API setting of the EVOS-fl-auto-2 microscope. e Image stitching setting on the VOS-fl-auto-2 microscope was used in order to t the full view of each individual 12-well ate.

fining the imaging scan/bead preparation system was designed and assembled to create iform alginate beads small enough for microscopic analysis First, a 3D-printed structure was designed to hold a 5 ml syringe in place at an angle of exactly 55 degrees This angle was determined by taking a photo of the original bead-making process and using the ruler function on the iPhone photo software to determine the angle at which the ruler was being held to create beads with the smallest diameter possible

Solidworks was used to configure the design of the structure Slic3r was the software used to convert the design to instructions for the 3D printer to make the print The instructions were put into the Ultimaker 2 extended plus and the structure was printed.

A syringe pump was set to a rate of 1 5 ml/min, and a 32 gauge tip was attached to tubing between the opening of the syringe and the tip Once the syringe was placed inside the syringe pump, the tubing in between the syringe and the 32 gauge tip was woven through the structure 3D printed, in order to achieve the optimum droplet-making angle at 55 degrees. The syringe

pump was turned on and allowed to run for a time window of 3 to 5 minutes A 50 ml beaker of calcium chloride solution was placed under the syringe tip so the alginate would fall in and become crosslinked by the calcium

20 μl of 0 1 μm fluorescent microbeads (FluoSpheres™ Size Kit #2, Carboxylate- modified Microspheres, yellow-green fluorescent [505/515], 2% solids, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added per one ml of 1.5% sodium alginate solution to facilitate measurement of the diameter of the alginate beads Beads were covered to reduce light exposure after being added to the alginate in a biosafety cabinet. The solution was vortexed after the microbead addition to ensure even dispersion of the microbeads.

Agarose gel molds were created to hold beads in place for the imaging scan, to ensure maximum accuracy of diameter measurements postimaging Using the software Solidworks, stamps in the shape of a circle with a diameter of 1 cm, with nine 3 mm deep rectangles that were 1.5 mm wide and 2 mm long protruding from the circular base, were created using a resin 3D printer. Once the design was configured on Solidworks, it was transferred to the software called Slic3r and converted to a stereolithography (STL) file and sent to the resin printer Once the design was printed, the stamps were cleaned with isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and then allowed to cure for an hour (Figure 3).

To create the agarose gel for the bead holders, saline (11 237g/L of NaCl/50ml) was placed into a 100ml beaker and set to warm up on a hot plate. Once the saline was warmed up, 2 g of agarose was added in slowly The heat was turned to a higher setting and the mixture was left on the hot plate until the particles of agarose dissolved Once the liquid was clear, the heat and stir settings were turned off, and 1 ml of agarose so lution was added to each well in a 12-well plate The stamps were placed into the warm agarose mixture and the well plate was placed at 23 ℃ until the agarose solidified into a gel The stamps were removed once the agarose was solid

Bead imaging procedure

Beads were imaged using an EVOS-fl-auto-2 microscope (ThermoFisher Scientific) Imaging areas were created for the scan procedure using the EVOS software. This was done by turning on the grid function and moving the position of t he microscope so that one of the wells created by the agarose mold was fully visible in the imaging window screen Then, aided by the grid function, the center of the imaging window screen was selected Once this center was selected, the button marked select image location was pressed to save that location. This was done for the top three of the nine well plates in each of the bigger twelve well plates The scan procedure was saved automatically before each experiment The GFP fe ature of the microscope was turned on during testing to visualize the fluorescence of the microbeads.

To calculate the rate of dissolution of alginate, the images of the beads were uploaded to Image J, and the straight line feature was used to measure the diameter of each bead for every time window when pictures were taken

EDTA and Alginate lyase refined comparison test

For the dissolution tests, three alginate beads were placed into every well of a 12-well plate with the bead holders. Timelapse images were captured of each bead set every five minutes for two hours for alginate lyase tests, and every two

minutes for EDTA tests, until the beads were dissolved The EDTA and alginate lyase combination was not used during this round of testing. GFP lighting in combination with DAPI lighting was used to capture the best possible images of the beads

Fiber tests were conducted using 0.1 M, 0.05 M, and 0 025 M EDTA alone Initial testing was done on the fibers surrounded in alginate, with no cells inside. The spun fibers were cut with a razor blade into 2 mm sections The fibers were placed into a 96-well plate, with no more than 12 fiber pieces in each of the well plates in order to not overcrowd the imaging scan Images were captured until the fibers had appeared to dissolve The Image stitching setting on the EVOS-fl-auto-2 microscope was used in order to get the full view of each individual 96 well plate.

The alginate lyase test ran for 121 5 minutes Data on the diameter could not be reported after 101.5 minutes because the beads were starting to dissolve, and the diameters could no longer be measured The diameter of the control, with saline, slightly increased over the course of the experiment, likely due to saline intake (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Diameter of beads at 20-minute increments in the presence of 0, 1x, 2x, and 5x the standard concentration of alginate lyase. Box and whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) for three replicants at each concentration Image by author.

All beads exposed to 1x, 2x, and 5x alginate lyase were measured to have a slightly increasing diameter as well, with 1x alginate lyase increasing the least. Again, the increase was also likely due to saline intake After an hour, the beads in every solution looked relatively the same (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Images of beads under EVOS-Auto-fl-2 microscope imaging screen with GFP detection Top left: alginate bead exposed to 1x alginate lyase; top right: alginate bead exposed to 2x alginate lyase; bottom left: alginate bead exposed to 5x alginate lyase; bottom right alginate bead exposed to the control, saline. All images taken 61.5 minutes after the addition of the solution Image by author

The EDTA test ran for 17.5 minutes. Data on the diameter could no longer be measured after 17.5 minutes because the beads were fully dissolved, with no masses of microbeads seen in the images. The diameter of the control with saline remained relatively constant, only fluctuating slightly, likely due to saline intake (Figure 6). All beads exposed to 0.1 M, 0.15 M, and 0.2 M EDTA were fully dissolved by 17 5 minutes, with only a diffuse spread of microbeads remaining where the alginate beads were originally placed Beads exposed to 0 2 M had the smallest area of bright green, which is where the highest concentration of microbeads was. 0.1 M had the largest area of bright green for all of the microbeads pictured (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Diameter of beads at 2-minute intervals in the presence of 0 1, 0 15, and 0 2 M concentrations of EDTA The box and whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) for three replicants at each concentration. Image by author.

Figure 7. Images of beads under EVOS-Auto-fl-2 microscope imaging screen with GFP detection Top left: alginate bead exposed to 0 2 M EDTA; top right: alginate bead exposed to 0.15 M EDTA; bottom left: alginate bead exposed to 0.1 M EDTA; bottom right: alginate bead exposed to the control, saline All images were taken 17 5 minutes after the addition of the solution Image by author

The Emboclear (a combination of alginate lyase and EDTA) test ran for 46 5 minutes Data on the diameter could no longer be measured after 31 5 minutes because the beads were fully dissolved (Figure 8) The images of the Emboclear test were taken under the DAPI setting of the EVOS-fl-auto-2 Since no microbeads were present and the GFP setting was not used.

Figure 8. Diameter of beads at 5-minute intervals in the presence of Emboclear created using published procedures (Barnett & Gailloud, 2011). The box and whiskers plot show the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) for three replicants at each concentration Image by author

The cell-free fiber test was performed using 0.1 M, 0 05 M, and 0 025 M EDTA The fibers were placed into a 96-well plate and imaged under the DAPI setting of the EVOS-fl-auto-2. All fibers exposed to 0 1 M were no longer visible within 1.5 minutes of the test initiation, which was before the first imaging scan had time to capture images Fiber exposed to 0 05 M EDTA and 0.025 M EDTA were no longer visible within 3.5 minutes of the test initiation (Figure 9).

The goal of this project was to determine the most effective way to dissolve alginate from around ASMCFs. Varying concentrations of alginate lyase and EDTA, both individually and in combination (Emboclear), were tested on alginate gel beads to determine which would dissolve the alginate the fastest without damaging the cells. EDTA at all concentrations tested was faster at dissolving alginate than the currently used concentration of alginate lyase 1x, 2x, and 5x the standard alginate lyase concentration used in the current ASMCF synthesis protocol had not fully dissolved the beads of alginate after 80 minutes, whereas 0.1 M EDTA fully dissolved the beads after five minutes

Figure 9. Images of beads under EVOS-Auto-fl-2 microscope imaging screen under the DAPI setting The top row depicts 12-well plates containing fibers exposed to (from left to right) 0 1 M, 0 05 M, 0 025 M, and the control, saline, at 1 5 minutes The bottom row depicts the same well plates at 3 5 minutes Image by author

More testing was done on fibers without cells using 0 1 M, 0 05 M, and 0 025 M EDTA The testing confirmed that EDTA dissolved the ASMCF faster than alginate lyase, with the 0.1 M concentration dissolving the fiber before 1 5 minutes, and the 0 05 M and 0 025 M dissolving the fiber in under 3.5 minutes. Based on the data reported here, a trial was run by another researcher on an ASMCF with live cells While the cells within the ASMCF remained alive when placed in EDTA at 0 05 M, the collagen inside the fiber was degraded, rendering this option unacceptable.

Emboclear, a commercial product that includes 0 5% w/v EDTA, and 0 2% w/v alginate lyase has been shown to work to dissolve alginate gel (Barnett & Gailloud, 2011). Emboclear is FDA-approved under a different name called “liquid embolic systems”. This is suitable for direct application to the human body and aids in the embolization of aneurysms If Emboclear is able to be used in the human body without harming it, this combination of EDTA and alginate lyase should likely be a safe option for the cells inside an environment created to emulate human muscle tissue, which is what the ASMCF does Concentrations of less than 1% w/v EDTA have been used in other situations

and shown to not degrade collagen (Gandolfi et al , 2018), so it is reasonable to expect that it would not dissolve the collagen inside the ASMCF. When Emboclear was recreated for these alginate bead experiments, it took 31 5 minutes for the beads to fully dissolve This was still faster than any level of alginate lyase tested on its own The next steps will be to test alginate lyase and EDTA on the fiber, and then try using it during the 3D printing process. These experiments will be pursued in the future

Determining the fastest method of dissolving the alginate while also keeping the smooth muscle cells inside the fiber alive is imperative to making sure the fiber works as well as possible while it is being used in 3D printers to make human tissue. This research represents an important step toward turning the possibility of 3D printing human organs into a reality.

This research project would not have been possible without the help of Dr Angela Panoskaltsis-Mortari, a Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, and Kyleigh Pacello and Joe Broomhead, who are researchers at the 3D Bioprinting Facility at the University of Minnesota I am thankful for the help they

provided me in developing this project and carrying out experiments occurring in their facility With their assistance, I have learned skills in the realm of 3D bioprinting and biomedical engineering Also, I would like to thank Dr Kati Kragtorp for her support throughout my research, and for allowing me the opportunity to conduct laboratory research through Breck’s Advanced Science Research Program.

6 Quick Facts About Organ Donation (n d )

Abka-khajouei, R , Tounsi, L , Shahabi, N , Patel, A K , Abdelkafi, S , & Michaud, P (2022) Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates Marine Drugs, 20(6), 364 https://doi.org/10.3390/md20060364

Barnett, B P , & Gailloud, P (2011) Assessment of EmboGel A Selectively Dissolvable Radiopaque Hydrogel for Embolic Applications Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, 22(2), 203–211 https://doi org/10 1016/j jvir 2010 10 010

Gandolfi, M , Taddei, P , Pondrelli, A , Zamparini, F , Prati, C , & Spagnuolo, G. (2018). Demineralization, Collagen Modification and Remineralization Degree of Human Dentin after EDTA and Citric Acid Treatments Materials, 12(1), 25 https://doi org/10 3390/ma12010025

Gungor-Ozkerim, P S , Inci, I , Zhang, Y S , Khademhosseini, A , & Dokmeci, M R (2018) Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: An overview Biomaterials Science, 6(5), 915–946 https://doi org/10 1039/C7BM00765E

Hafen, B B , & Burns, B (2023) Physiology, Smooth Muscle In StatPearls StatPearls Publishing http://www ncbi nlm nih gov/books/NBK526125/

Kahrilas, P J (1997) ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROESOPHAGEAL JUNCTION Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 26(3), 467–486 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8553(05)70307-1

Learn how organ allocation works OPTN (n d ) Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://optn transplant hrsa gov/patients/about-transplantation/howorgan-allocation-works/

Mittal, R K (2011) Neuromuscular Anatomy of Esophagus and Lower Esophageal Sphincter In Motor Function of the Pharynx, Esophagus, and its Sphincters. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences. https://www ncbi nlm nih gov/books/NBK54272/

New Technique Turns Alginate Solution Into Micron-Scale Gel Patterns Using Light (n d ) Retrieved January 11, 2024, from https://chbe umd edu/news/story/new-technique-turns-alginate-solu tion-into-micronscale-gel-patterns-using-light

Pushparaj, K., Balasubramanian, B., Pappuswamy, M., Anand Arumugam, V , Durairaj, K , Liu, W -C , Meyyazhagan, A , & Park, S (2023) Out of Box Thinking to Tangible Science: A Benchmark History of 3D Bio-Printing in Regenerative Medicine

and Tissues Engineering Life, 13(4), 954 https://doi.org/10.3390/life13040954

Schubert, J , Khosrawipour, T , Pigazzi, A , Kulas, J , Bania, J , Migdal, P , Arafkas, M , & Khosrawipour, V (2020) Evaluation of Cell-detaching Effect of EDTA in Combination with Oxaliplatin for a Possible Application in HIPEC After Cytoreductive Surgery: A Preliminary in-vitro Study Current Pharmaceutical Design, 25(45), 4813–4819 https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612825666191106153623

Vogt, C D , & Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A (2020) Tissue Engineering of the Gastroesophageal Junction Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 14(6), 855–868 https://doi org/10 1002/term 3045

Zhu, B , & Yin, H (2015) Alginate lyase: Review of major sources and classification, properties, structure-function analysis and applications. Bioengineered, 6(3), 125–131. https://doi org/10 1080/21655979 2015 1030543

Noah Getnick and Evan Johnstone

Noah Getnick and Evan Johnstone

Introduction

Riding a bike is both a carbon-efficient mode of transportation and a great way to maintain fitness (Eisenman et al., 2010). However, the inherent difference in speed and size between cars and bikes makes it dangerous for cyclists to share the roads with cars, discouraging people from engaging in this beneficial activity (Reynolds et al , 2009) In the United States, there are approximately 49,000 automobilecyclist collisions a year, over 700 of which are fatal Riding a bike along busy streets can be an extremely difficult task. Cyclists must maintain visual awareness along the path of travel, while simultaneously glancing backwards at potential threats from the rear. Unsurprisingly, about 40% of car-bicycle collisions involve crashes where the car approaches the cyclist from the rear (Woongsun Jeon & Rajamani, 2016).

Technology dedicated to warning cyclists of approaching cars is still in its infancy The most common method of detection is through small radar systems attached to the rear of a bicycle. These systems include the Garmin Varia (Garmin, n d ), the Bryton Gardia (Bryton Gardia R300L, n.d.), and the Magene L508 (L508 Radar Tail Light, n d ) These systems have detection ranges of over 100 meters (Garmin, n.d.). However, in urban environments and crowded spaces, they often give false warnings, as the radar has no way to determine if a target is a motor vehicle or a harmless object (Garmin Varia Bike Radar - Worth It?, n d ) This shortcoming significantly limits the efficacy of these systems, since after several false alarms, cyclists may simply ignore subsequent warnings

Experimental solutions to warn bikers of approaching cars have been proposed using various sensing technologies Woongsun Jeon &

Rajamani designed a custom built sonar sensor system with a unique one-transmitter/tworeceiver design, paired with a single beam laser sensor for detection behind the bicycle. This system is effective at detecting vehicle position and orientation, but due to its single-beam sensor design, it has no way of visually confirming the identity of the detected object (Woongsun Jeon & Rajamani, 2016) Smaldone et al created an attached camera system to track oncoming vehicles This system uses a simple camera with a computer vision system to paint a “danger zone” within the camera frame, warning the cyclist when a car is detected in the zone However, the use of camera tracking puts a heavy workload on the processor, requiring an expensive PC mounted to the bike (Smaldone et al , 2011) Furthermore, neither of these examples are currently commercially available.

We designed a system that will detect a dangerous approach by an automobile from the rear and left side of a bicycle and provide an early warning to the cyclist. We used a sensor fusion system, consisting of a distance sensor coupled with a camera that uses computer vision to track oncoming vehicles. A TFLite object detection model (TensorFlow Lite, n d ) was trained and used to detect cars with the camera. The whole system was programmed with the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B single board computer (Raspberry Pi, n.d.-b, p. 4). The system is mounted on a rear bike rack.

The central unit and processor for our system is a Raspberry Pi 4B (2GB of RAM; Raspberry Pi, n d -c), a small computer designed for a variety of applications. We installed the Raspberry Pi

into a commercially available case (Raspberry Pi, n d -a) The Raspberry Pi has 40 GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) pins for powering and communicating with sensors, servos, and lights, as well as a ribbon cable port for a camera

To program the Raspberry Pi, we plugged the computer into a monitor, mouse, and keyboard, allowing us to use the Raspbian operating system to run multiple applications. The Raspberry Pi is powered by a UPSPack power supply (Raspberry Pi UPSPack, n d ), which converts 3.7V from a 10000 mAh battery to 5V. The battery can supply power to the Raspberry Pi for at least two hours During preliminary testing, the Raspberry Pi ’s central processing unit (CPU) overheated frequently, causing temporary shutdowns, so we installed a Raspberry Pi case fan (Raspberry Pi, n.d.-d), designed to fit into the case. We used the Raspberry Pi configuration menu to run the fan automatically when the central processing unit temperature reached 60°C.

A Raspberry Pi Camera Model 2 (Raspberry Pi, n.d.-c) was used to capture video to be analyzed by an object detection model It attaches to the Raspberry Pi with a proprietary ribbon cable.

We used a distance sensor to detect nearby objects to complement the camera. Initially, we used a TFMini-S Micro LiDAR sensor (TFMini-S, n d ), which communicated with the Raspberry Pi through the UART serial port. However, this range decreased in outdoor conditions, since the sunlight interfered with the infrared waves it was transmitting. As a result, we switched to an ultrasonic sensor, which is unaffected by lighting conditions, since it uses sound waves to determine its distance from an object. We used a MaxBotix MB1010 sensor (MB1010 LV-MaxSonar-EZ1, n d ) It sends out sound waves to determine the range of an object by recording the time it takes for the wave to return to the receiver The sensor then sends out a digital pulse to the Raspberry Pi. Using code

from a Github repository (LV-EZ1 for Raspberry Pi, n d ), we wrote a script to convert the length of the pulse to distance measurements

To create a mount for the sensors, a 0.5 inch thick piece of Delrin plastic was cut, using a vertical bandsaw, to create a 3in x 3.5in rectangle with a rectangular (0.5in x 0.5in) cutout on the bottom right corner, to leave room for other components. The cut piece was secured to a servo motor (SunFounder Digital Servo, n d ) using the motor’s included plastic rotor mounts and bolts. Both sensors were mounted using 4-40 bolts

Initially, both sensors were mounted on the same face and plane, but to improve sensor accuracy, the ultrasonic sensor was later mounted at an angle This made it easier for the bicycle to detect cars passing to the side of the bicycle. A vertical bandsaw was used to cut a corner of the Delrin block to create a 45 degree slanted mount surface for the ultrasonic sensor.