46 minute read

Regulars

Time to level up – south of the Thames

Planning in London has been published and edited by Brian Waters, Lee Mallett and Paul Finch since 1992

Not surprisingly, the idea of ‘fairness’ is being discussed widely in the context of the new world envisaged once we have all been vaccinated. Changed priorities are assumed to be a matter of course following a reassessment of what really matters in life when health is a greater priority than economic success, and fighting inequality (however defined) becomes a political consensus which will, inevitably, have consequences for planning.

One of the characteristics of current discussion about the future is the proposition that unique inequalities attached themselves to specific sectors of society, and therefor required targeted assistance. This is in direct contradiction of the long-standing mantra that public policy should be about the ‘greatest good for the greatest number’.

The latter proposition is colour- and class-blind, up to a point. Facilities such as parks, libraries and swimming pools, quite apart from schools and hospitals, are available to all. They are public spaces par excellence. Any robust public planning policy should be based on the provision of community assets which are available to all – and spending should be geared to that end.

Similarly, investment in transport should surely be aimed at the creation of additional facilities for all, irrespective of sociological factors which, in any event, are never static. By the time Crossrail 2 is completed, which may be decades later than originally intended, London will be a very different city to the one we know today – in the same way that it is fundamentally different to what was envisaged when the Elizabeth Line (or Crossrail 1, even the names change) was first envisaged.

Transport infrastructure is impeccable in its neutral attitude to race, gender and class. However, decision-makers about where and what is built are, of course, subject to all the political pressures inevitable in the running of a world city.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that mayoral policies in relation to transport linking London across the Thames are based on a profound belief that the less connection, the better it is. The recent ongoing shambles over the closure of Hammersmith Bridge is only part of the story. The closure of London Bridge to ordinary road traffic and the increasing restrictions on road access to bridges generally is part of a weird policy, never explicitly stated, to make it increasingly difficult to cross the river in a convenient way unless you happen to have access to the Undeground, which is massively disproportionately geared to Londoners who live north of the river.

Unsurprisingly, the anti-bridgebuilding attitude established when Sadiq Khan reversed his support for the garden bridge project has continued to blight other cross-river initiatives: not just a rational replacement for Hammersmith bridge, but also the abandonment of the Rotherhithe Park/Canary Wharf pedestrian and cycle bridge, and the recent announcement that plans for a similar bridge from Nine Elms to Pimlico are ‘under review’. For which read ‘scrapped’.

Curiously, since he hails from Tooting, Mayor Khan seems happy to make life increasingly difficult for anyone who wants to cross the river. What is his problem? n >>>

Planning after the pandemic

Now's the time in the darkest hours before a vaccinated dawn for some re-thinking amid the 'creative destruction' Covid-19 has unleashed, accelerating pre-existing trends brought on by the tech-driven 'Fourth industrial revolution'.

Nowhere more so than in urbanism and planning, with enforced localism, High Streets and big box retailing in intensive care, city cores depopulated and all bets off on whether working practices will revive or condemn them. A series of 20 podcasts launched by architects Metropolitan Workshop called Reshaped contains pointers for rethinking aspects of urbanism and planning.

Planning's primary function has evolved to arbitrate competing interests for land use. Yet its origins lay in envisioning better places. Our new big idea for that is ironically a suspiciously succinct French import that has slipped past customs from fog-bound Continental friends in Paris. The 15-minute neighbourhood is a lovely idea to which we can all subscribe. But as Professor Paul Chatterton of Leeds University points out in his Reshaped episode, it might turn out to be a supercarrier of the gentrification virus, as privileged vocal communities reap advantage while poorer communities get left behind.

And what use are self-contained 15-minute arrondissements if the transport arteries of a city like London remain fossilised in centuries-old sediments of a hub and spoke format? Without improved lateral connectivity to spread economic, social and cultural sustainability between these new neighbourhoods, will London's jaded suburbs remain fixed in aspic while the centre rots? You can't just look at a neighbourhood, you need to think about the city-wide eco-system in which it exists. But the 15-minute neighbourhood is nevertheless an opportunity to rethink planning and its primary objects in a way people can engage with.

Then there is the lip-service paid to community engagement – a term that at least has evolved from the fait accompli of 'consultation'. Several London-based speakers in the series expound the virtues of new ways to make participation meaningful. But Newham's elected mayor, Rokhsana Fiaz, has taken the idea a stage further. She describes in her episode how she is using community engagement, driven by experiences with estate residents, to shape broader policy and delivery of services.

Engagement specialist Daisy Froud also talks about the need for 'bigger public conversations' about the issues we fear most - climate change, housing, economic opportunity – to drive headline policy. Our planning system is democratic. To make it meaningful, democracy must be alive and kicking if there is to be trust in it.

And what of tech's impact on planning and urbanism? Professor Abel Maciel of the Bartlett's Faculty of the Built Environment tells the most revolutionary story. Blockchain encryption, AI and machine learning will shortly enable a world of ubiquitous digital truths that cannot be tampered with. Good news for American and democratic elections everywhere. But also transformational evidence-based tools with which to plan London and the UK. That is if it remains united. n Reshaped: new thinking in planning and urbanism podcasts can be found at: https://metwork.co.uk/prospects/reshaped. The series is directed by Lee Mallett

Hammersmith & Fulham Council and Foster and Partners unveil new plans for Hammersmith Bridge

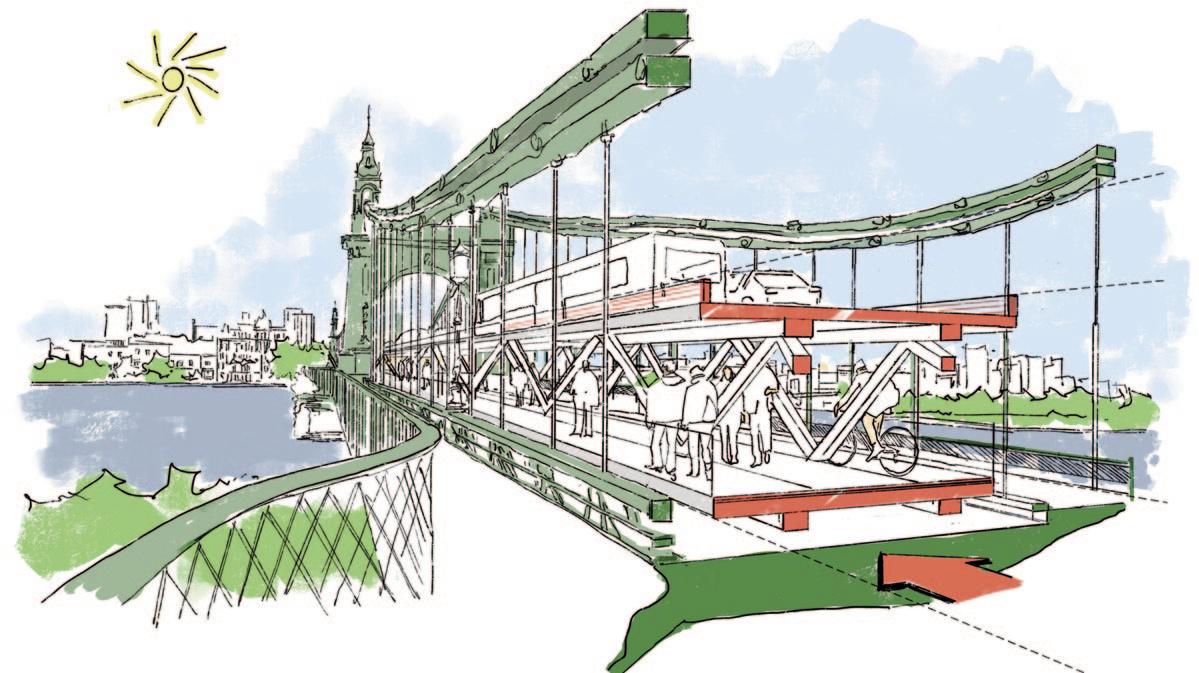

Hammersmith & Fulham Council, Sir John Ritblat from Delancey, and architects and engineers Foster + Partners have unveiled a radical new plan to build a temporary double-decker crossing within the existing structure of Hammersmith Bridge that has been closed fully on safety grounds since 13th August.

Under the proposal, pedestrians, cyclists and, potentially, motor vehicles could be using the bridge, with river traffic passing underneath, within a year of a contractor being appointed. A new raised truss structure would be built above the existing road deck featuring a lower level for pedestrians and cyclists and an upper level for cars and buses.

H&F Leader Cllr Stephen Cowan has outlined details of the proposed plan to Transport Secretary Grant Shapps and urged the government to give it full consideration.

Sir John Ritblat approached Foster + Partners to develop an alternative plan for the bridge after Stephen Cowan asked for Sir John’s assistance following the bridge’s closure in August. The concept plan designed by Foster + Partners and further developed with specialist bridge engineers COWI, has been presented to Department of Transport officials.

Initial estimates suggest the temporary crossing would allow the strengthening and stabilisation works to the 133-year-old heritage bridge to be completed at a cost lower than the current £141million estimate. The raised deck would enable existing approach routes for traffic to be used, causing minimum disruption for residents on both banks of the river. The structure will also provide support for the bridge as well as a safe platform for restoration work to be carried out. >>>

>>> There would be no load added to the existing bridge deck which would be removed in stages for repair. Contractors would use the new lower pedestrian deck to access the works. When completed, the temporary raised deck would be removed. Elements of the Grade II* listed bridge that need repair, including pedestals, anchors and chains, would be lifted away using the temporary bridge and transported by barges to an off-site facility for safe repair and restoration. By repairing the bridge off-site, the huge task of restoration can be done at greater speed, to a higher level and at significantly reduced cost. It would also minimise noise, environmental impact and onsite activity, as well as reducing the all-important carbon footprint of the works. Historic England approval would need to be sought for this scheme which enables the bridge to be restored to its original Victorian splendour with fewer constraints. Cllr Cowan said: “I am extremely grateful to Sir

John Ritblat for responding to our call for help so comprehensively. The Foster + Partners and the

COWI design team have developed an exciting and imaginative initiative which has the very strong possibility of providing a quicker and better value solu• Raised deck envisages temporary crossing for vehicles, pedestrians and cyclists • Faster and cheaper than previous plans • Transport Secretary given outline brief by Council Leader

tion than any of the other proposals.

“Our engineers have held positive and constructive talks with Foster + Partners and COWI. I am optimistic that we now have a viable option within our grasp that is a win for all. I commend it to the Government in the hope that it will be the catalyst for real progress in funding all the necessary works to the bridge.

“We have been exploring a variety of options since the initial closure to motor traffic in 2019 and now have a proposal which potentially meets our objectives of a fast track, lower cost, lower noise, lower emission solution that would lead to an earlier reopening of the bridge.

“I was pleased to be able to deliver the news of the project to the Secretary of State and look forward to working with his Taskforce to find a solution that works for everyone impacted by the bridge’s closure.”

Luke Fox, Senior Executive Partner at Foster + Partners, said: “We are excited to propose this simple and sustainable solution to this important missing piece of London’s infrastructure that also gives the opportunity to bring back to life a beautiful and iconic bridge by Sir Joseph Bazalgette.”

Roger Ridsdill Smith, head of Structural Engineering at Foster + Partners, said: “We believe that our concept resolves the two challenges for Hammersmith Bridge economically and efficiently: delivering a temporary crossing quickly, whilst providing a safe support to access and refurbish the existing bridge. We appreciate the engagement and contribution from the technical experts in charge of the bridge and look forward to further studies to develop the scheme.”

David MacKenzie, Executive Director at COWI, said: “We consider that this approach is practical and viable. Our experience is that offsite refurbishment of bridge structures is safer and more controlled, and results in a higher quality final outcome when the structure is re-installed.” n

STAY AT HOME... with updated Monopoly!

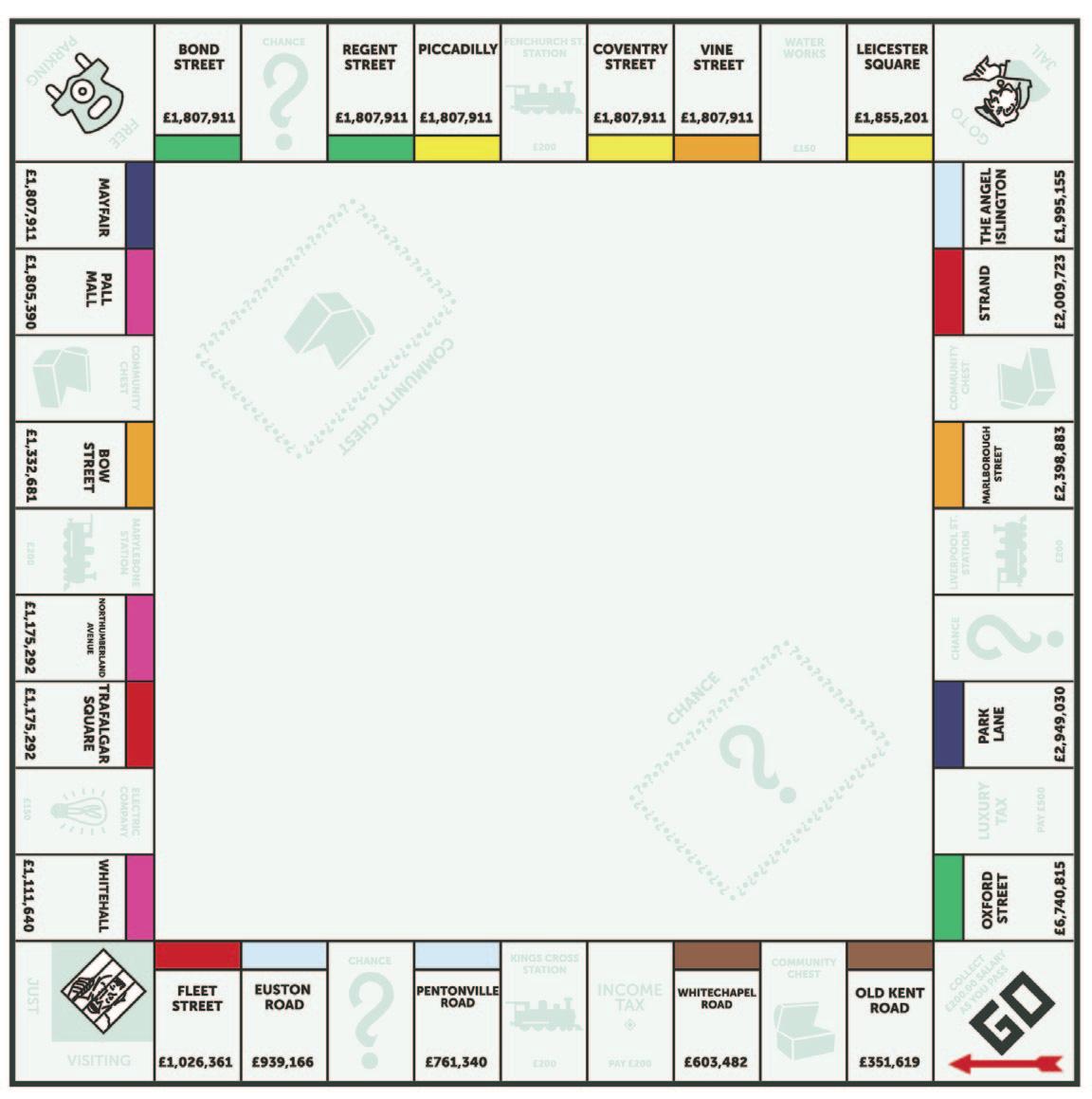

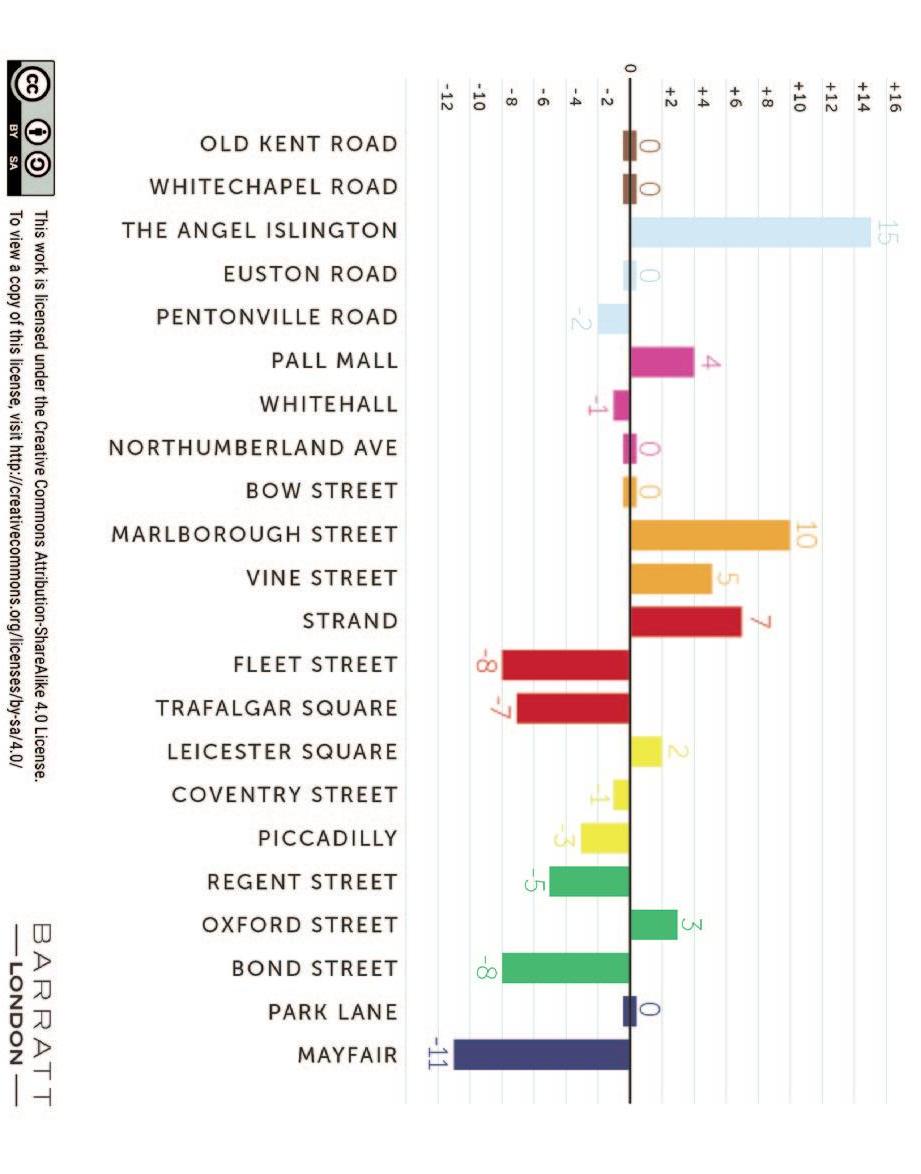

A new study has found the board would be significantly different if the 1936 London board was updated to reflect modern-day prices in the capital.

RIGHT: How the Monopoly board would look in 2020 The number of places each property would move on the board if they were to be ordered based on modern day average house prices as calculated by Barratt London An Around The Board Tour, from Barratt London, has found that only six of the 22 locations on the board would remain in the same place, with The Angel Islington climbing the most positions from the light blue squares to the greens, a 15 space jump.

• The Angel Islington would be joined in the green positions by Marlborough Street, which enjoys a 10 space jump, the second-largest climb, and The Strand which completed the top three in terms of climbing in value, welcoming a seven space jump. • Oxford Street, green on the original board, leapfrogs Mayfair to occupy the most expensive place on the board, with Park Lane maintaining its position as the second most expensive square on the board. • Similarly, Old Kent Road and Whitechapel Road remain as the two cheapest locations on the Monopoly board, with Fleet Street making one of the biggest drops (eight) from the red spaces to the light blues, joining Pentonville Road and Euston Road, which remain in the same colour bracket. • Bond Street would also drop by eight spaces into the red spaces, while Mayfair makes the biggest drop, joining Bow Street and Pall Mall in the orange positions, a drop of 11.

You can explore the full board at www.barratthomes.co.uk/

new-homes/london/around-the-board-tour. n

Creative ways to build a property portfolio

When starting in the property market I had almost no money to invest so I needed strategies to allow me to build my property businesses without a large lump sum of capital.

Many people in London are in the same position currently. Deposits are high yet mortgages are at some of their lowest rates. And there are many properties for sale due to the coronavirus backlog and stamp duty changes. So how do you get started?

Here are the three strategies I used to go from almost nothing to building a million-pound property portfolio in just three years.

Rent to Rent

The first strategy I used to get my property portfolio off the ground was by becoming a property manager for house shares. I’d rent a property, take on the bills, work to make it a comfortable home, and then rent to someone else. Adding value allowed me to charge a higher rent than I was paying. This cashflow enabled me to save for deposits to buy my own property.

It’s not really an investment strategy but an ethical way to make money from properties without buying them. Of course, you need to find landlords who are willing to allow you to sublet the property and properties that could use some TLC so that you are adding value. It’s all about creating beautiful affordable homes Londoners will love to live in. Working ethically to add value for both tenants and landlords is the foundation of rent to rent.

Lease Options

Lease options are actually a combination of two agreements: the lease and the option.

The lease is the agreement with the owner to rent out the property to tenants in return for a monthly payment. The option is the price agreed to buy the property at a later date, if you choose to.

A lease option typically involves the following • an option fee, also known as a ‘consideration’, that you pay upfront • your monthly payment (the lease) • an agreed purchase price (the option) • an agreed purchase-by date (you can purchase before this date)

Now, you may be asking: Why would a seller agree to sell their property and then wait five years or more to be fully paid for it?

The most common reason is that a seller is in negative equity; the property has reduced in value, yet they still have a mortgage to pay off. By agreeing a lease option, they get their mortgage covered which can help them return to positive equity.

Another common reason is that sometimes the seller wants to move more quickly than the standard property sale process allows, such as for work relocation. A lease option gives them the opportunity to move now without losing money on their property.

We go into a more detailed explanation of lease options in our podcast: https:// rent2rentsuccess.com/r2rspodcast/3

Let’s take a worked example of a lease option:

David bought a property at the height of the market in 2007 for £300,000.

By 2016, the value had dropped to £250,000, leaving David in negative equity and set to lose around £50,000 if he’d sold it. Also, the property was costing him £800-£1,000 per month.

David first used Rent 2 Rent Success to cover his mortgage and we made the property look incredible, moving in some more tenants. After a few months, the property had regained some value and David was keen to sell.

A lease option then made perfect sense. David got his mortgage assured for a few more years and then got a hassle-free sale for a price he was happy four elements:

with. We got to buy the property without needing a big mortgage or deposit.

Lease options can be ideal if the conditions are right for buyer and seller. Unfortunately, this can make them hard to find and settle on an agreement. Look for anyone wanting to move quickly and/or who may be in negative equity as they’re most likely to benefit from a lease option.

Exchange with Delayed Completion

An exchange with delayed completion is similar to a lease option. You contract with a seller to buy their property, on or before, a specified date at a specified purchase price. Unlike lease options, how-

Stephanie Taylor is cofounder of Rent 2 Rent Success

ever, you have an obligation rather than an option to buy it by the agreed date.

Let’s take another worked example:

A couple decided to start selling off their small portfolio as they approached retirement, while avoiding the usual hassle of selling.

We, the buyer, agreed on a purchase price, in this case £160,000, and a five-year completion date. We paid an option fee of £16,000 up front (although this can be as little as £1) with monthly payments of £320, leaving a balance of £124,800 after five years.

The couple got a lump sum, a predictable monthly income, and a definite sale price/date. We, the buyer, benefitted from renting out a property, generating income, and eventually purchasing the property without a 30% deposit or any of the usual hassle.

Using these strategies, you could start your own property portfolio with less money than you might expect. n

Stephanie Taylor is co-founder of HMO Heaven and Rent 2 Rent Success. She launched Rent 2 Rent Success to help professionals who want to get involved in property, but feel stuck as they’re worried they don’t have enough time, money or knowledge to get started. Through her Rent 2 Rent Success YouTube channel, podcast and website, Stephanie debunks the myth that you need large sums of money to get started in property. Her book ‘Rent to Rent Success – Our ethical 6-step system to get started in property without buying it’ will be published in this month.

Find out more 1 Learn about Rent to Rent from the government’s property ombudsman The Property Redress Scheme 2 Find out how to do rent to rent ethically with the Free Rent 2 Rent Success Guide and Masterclass 3 Join our supportive community at Rent 2 Rent Success Secrets on Facebook.

https://rent2rentsuccess.com https://www.facebook.com/rent2rentsuccess https://www.instagram.com/stephanietproperty https://www.linkedin.com/in/missstephanietaylor https://www.youtube.com/rent2rentsuccess https://rent2rentsuccess.com/podcast

Planning reforms: a London perspective

The White Paper is quite right in trying to draw planning back to its core principles and objectives, say Stuart Andrews and Matt Nixon, but it must face up to the politics

The White Paper Planning for the Future proposes significant changes to the planning system in London. One such change is that local areas will develop streamlined plans for land to be designated into three categories: • Growth areas “will back development”. • Renewal areas “will be suitable for some development - where it is high-quality”. • Protected areas “will be just that”.

From a London perspective, this could be business as usual as the existing plan system already allocates land for different developments and the proposed ‘zoning system’ is not a massive departure. What is not clear, is what role the London Plan or other spatial development strategies outside the capital will have in this new world. Also, as development management policies will now be found in a revised national policy framework it is not yet clear how this would operate alongside the policies currently in the London Plan.

The novel twist is the suggestion that in areas of ‘growth’, land will be allocated for development and the opportunity will then exist for the designated land to have ‘permission in principle’ (PiP) with no further controls save for complying with a masterplan and design codes. This could be a tidy proposition, if at the time the site is allocated, you know the full extent of its impact and the measures needed to regulate, mitigate and control development. Not an impossible task, but one that will require substantial upfront investment, resource and commitment. So far, from a public service perspective there are no promises being made and in all prospect the burden and risk will rest entirely with the development industry.

Local authorities will also be directed as to ‘policy on’ binding housing requirements for their areas, which we are told will take account of land constraints. This will on current analysis substantially increase the numbers in London and the South East and such is the politics of planning that it has already been mistakenly badged as an ‘algorithm’.

Whilst, the details of the methodology is not yet known, it is clear that those making the calculation will have to take great care in areas that have, in the past, proven difficult to calibrate localised constraints. You only need to look at the Inspectors’ comments to the draft New London Plan in respect of brownfield land to see the pitfalls of trying to robustly provide estimates on capacity.

Whilst it is not an impossible task for London boroughs to find the ‘growth’ land to satisfy the central government housing figures, constrained environments needs careful planning, meaningful consultation and a balanced judgement in delivery of urbanised and inevitably compacted growth. Inevitably, there is clearly a great deal of work to be done.

Add the PiP dimension and planning in London moves from being an administrative process to an art form. It is akin to comparing cooking, with the production of a banquet in a Michelin star restaurant.

The ‘duty to cooperate’ is removed in the White Paper, but adjoining authorities can still prepare joint plans and thereby agree alternative housing distributions. This is welcomed, but it does mean that the

wider distribution of numbers will become an exercise of goodwill rather than prescription. You can reach your own judgement on the prospects of surrounding authorities accepting the overflow of numbers from London, but the current track record doesn’t make for a compelling argument.

The process of developer contributions is also under review. The current process involves complex discussions in establishing the legal commitments to deliver roads, schools etc. on-site or through off-site contributions. The White Paper quite rightly describes this as a system of cost, delay and uncertainty.

Stuart Andrews [ABOVE], National Head of Planning and Infrastructure Consenting, and Matt Nixon [RIGHT], Principal Associate, Planning and Infrastructure Consenting, Eversheds Sutherland

The suggested answer is a “new Levy to raise more revenue”. The proposition being a tax on new development that is collected by the local authority and then applied to secure the necessary infrastructure and facilities.

It’s so simple you can only wonder why no one thought of it before? But hold on, they did, and it has been in existence since 2010 in the form of the Community Infrastructure Levy Regulations. Here too any London borough can abandon S.106 Agreements and can put it all into CIL and then collect and apply those funds as a tax on development. Not one Council has picked up that bat and ball in 8 years. The reason is simple, it requires cash strapped Councils to guess at the delivery of development, fund in anticipation of receipts and then sit and wait for the funds to roll in to meet their advanced spending. Just imagine your career prospects if you unknowingly invited your Councillors to pursue that policy just before a global pandemic.

The short point is that London planning is completely entwined with the politics of London. It is complex, messy and sometimes it needs to be too. The White Paper is quite right in trying to draw planning back to its core principles and objectives, but it can only combat the politics in planning by facing up to the fact that is what it is really all about. n

Architecture: why evolution needs to be about fire safety

Innovation should always be applauded but it’s the health and safety of high-rise occupants that needs to be the priority, says Thomas Bradley

It’s easy to think that architecture as we know it today was created by the ancient Greeks or Romans. But you only have to look at pre-historic structures, such as Stonehenge or the Nuragic monuments in Sardinia, to see how far back it goes.

The premise of architecture is to create timeless spaces for life’s activities. At its core, these structures can help to improve human life.

As time has moved on, so too has the evolution of architectural style. Every generation sees a wave of new ideas and innovations that create exciting homes and workplaces. But while fire safety isn’t everyone’s first thought when they think of architecture, it’s something that needs to be just that in the current climate.

Today’s topic of discussion is around the evolution of architecture, the fire safety factor that is influencing change, and what the future may look like for high-rise buildings with the industry still under the spotlight following the Grenfell Tower fire back in 2017.

History of the high-rise structure

The first high-rise buildings were constructed in the United States back in the 1880s. They were positioned in urban areas where high-cost land prices and greater population density created a demand for buildings that rose vertically rather than horizontally.

The use of steel structural frames and glass exterior sheathing made them practical. By the 20th century, they became a standard feature as an architectural landscape in countries across the world.

In the UK, high-rise buildings were primarily used to address the housing shortage following World War II. The rate of population outgrew the supply of housing, so the ‘streets in the sky’ approach was favoured by architects and planners.

Between the end of the war and the early 90s, over 6,500 multi-storey blocks of six floors or more were built in the UK. Commercial high-rise developments have followed a similar trend and pattern to residential property, with densely-populated cities relying on tall buildings to create office space big enough to get value for money when securing sparsely available land.

Some of the most expensive building developments in the modern day are high-rise and multi-functional, like the Shard in London, with the 306-metre tall structure even featuring a hotel.

Fire safety influencing design

The planning, design, and construction phases of an architectural project are not as straightforward as coming up with an idea and seeing it become a reality through bricks and mortar. Many factors impact how an architect comes up with the design and practicality of a structure that will have longevity.

Some of the most common factors include climate, culture, environment, technology, imagination and the materials available to complete a project. But with the introduction of new fire safety legislation comes the importance of factoring in fire safety into the architectural process.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) recently introduced a new educational framework focused on fire safety that would be “the biggest shake-up of the profession since the 1950s”. With government pressure in wake of the Grenfell Tower fire and growing concern around climate change, the framework signifies a different approach for architectural education that will have a greater emphasis on life safety, with fire safety playing a big part of the focus.

The first mandatory competence of the course –health and life safety, including fire safety – will be introduced in 2021. Architects will be expected to pass a test to prove their competence. It’s a sign that the future won’t just be about technology, innovation, and buildings that will look beyond their years. It will predominately be focused on the correct use of architectural cladding, the following of safety regulations, and the overall consideration for human wellbeing when designing and delivering projects.

The need for evolution to continue

Innovation should always be applauded. But it’s the health and safety of high-rise occupants that always needs to be priority number one.

Back in March, Bruce Sounes, an associate architect at Studio E – who had a role in managing the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower in 2015 and 2016 – told

Thomas Bradley is a copywriter working with Sotech

the enquiry into the fire that he had not read sections of Approved Document B – the fire safety advice found in the UK government's Building Regulations 2010.

Sounes also hadn’t read the document's specific fire safety guidance for buildings over 18-metres tall and was unaware that aluminium cladding panels were combustible – despite their regular use as a way to create more energy-efficient buildings.

The fire has brought the conversation around cladding into the forefront of people’s minds, as the media – and those left living in buildings where cladding has been found to be unsafe – are left to question what happens next. To put it into context, the government admitted in June that they didn’t know how many of the 85,000 buildings between 11 and 18 feet still had unsafe cladding. And while this doesn’t take into account commercial properties that sit above 18 feet tall, it does give an overview of the current problem faced in the world of architecture and construction – with high-rise buildings in London alone set to cost £4 billion to rectify.

The price to pay for not putting fire safety first is not only financial but one that can have a devastating impact on the lives of many. While modern design and innovation should never be sacrificed, neither should the health and safety of those occupying commercial and residential property. n

Sources http://www.highrisefirefighting.co.uk/history.html http://www.magtheweekly.com/detail/10170-shangri-la-hotel-atthe-shard-london-uk http://www.sotech-optima.co.uk/ https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/government-has-nodata-on-how-many-buildings-under-18m-have-dangerouscladding https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-51851900

A better option for affordable homes

Provision of affordable homes in London should be the remit of housing associations and local authorities says Anthony Ratcliffe

In May 2018, Sadiq Khan’s office published The Mayor of London’s London Housing Strategy, stating that, under his administration, affordable homes planning consents had increased from 13 per cent to over 30 per cent and that from 2017, more than 12,500 affordable homes were being built.

He confirmed that he had secured over £4.8 billion from central government for affordable housing investment, with a target of delivering 116,000 affordable homes by 2022. His strategy would “take appropriate action to unblock stalled housing sites and increase the speed of building,” whilst also continuing to protect the Green Belt and open spaces, “with a long-term strategic target that half of London’s new homes would be genuinely affordable,” by some unstated date in the future. In May 2019, City Hall reported that 14,544 affordable homes were started in 2018/2019, which was more than in any year since it had taken control of London’s housing investment. Nevertheless, this falls well short of the 65,000 annual new homes requirement the Report targets.

Why do we have a housing crisis in the UK, and in London in particular? It is because for years we have built fewer and fewer homes. From 1951 for 31 consecutive years, more than 200,000 houses were built in the UK every single year. Since 1990, that 200,000 mark has only been exceeded in five years.

What happened to create such a shortfall, whereby over the last 30 years, less than half of the new homes requirements has actually been built? In the writer’s opinion, the single major contributing factor has been the introduction by the Blair Administration of the Affordable Housing Requirement, which has reduced supply, increased costs, and delayed delivery.

A developer, having acquired or optioned a site, then wastes two or more years negotiating the Local Authority’s unviable 50 per cent Affordable Housing demand, down to a viable 15 per cent to 20 per cent, before a brick is laid. Interest charges and professional fees increase in this tortuous process, swelling the development cost and the required home sale price as a consequence. The Affordable Housing Requirement should be abolished and replaced by a levy per consented housing unit, at a level set by the Local Authority, having regard to local house values, with the monies ringfenced, and then applied to the development of social housing on more suitable sites. Also, the developer should pay an additional escalating levy if its development has not started within two years of consent being granted.

In the real world, the rich do not want to live next to the poor, and the poor do not want to live next to the rich. A levy per consented unit scheme will more effectively make the rich pay for the privilege of funding housing for the poor to live elsewhere, and ideally just a short bus ride away, so that the jobs created on the ‘rich’ estate can be conveniently reached.

The provision of affordable homes should be the remit of the housing associations and the local authorities, and not the responsibility of the private sector housing developers, whose contribution should just be tax-based. Developers should be permitted to build what the market requires; whether that is flats, starter or family homes, should be determined by their expertise and market demand.

The pledge to always protect the Green Belt is an error. It contains significant areas of unattractive land which should be developed and replaced by more attractive land that is presently outside the Green Belt designation and therefore inadequately protected.

In addition to the abolition of the Affordable

Anthony Ratcliffe is the founding Partner of Ratcliffes Chartered Surveyors which is in its 50th Year

Housing Requirement, the following steps should be taken: 1 Appoint a leading figure from the housing industry as National Housing Tsar, with sweeping powers to override local Planning Officers and Councillors, as well as Government Planning Inspectors, and with a remit to deliver 250,000 new homes a year. Fire him/her after three years, if they are not on track. 2 Allow all pension schemes to again invest in residential property, without restriction. 3 Improve the tax breaks to encourage commercial Landlords to convert their properties to residential use. 4 Amend height restrictions in urban areas adjoining strong infrastructure and transport links, permitting two storey properties to be redeveloped as 4/6 storeys, whilst requiring an increased green footprint as public benefit. This would significantly increase London’s housing supply. 5 Phase in Stamp Duty reductions back to a half per cent level, thereby restoring mobility to the market and discouraging disruptive basement extensions and inappropriate loft conversions. Replace the lost revenue by introducing a long overdue higher Council Tax banding. It is indefensible that in England these have been unchanged since their introduction in 1991, whilst house prices have trebled.

A top band householder pays less than an average £50 per week in Council Tax, whether his house is worth £320,000, £3.2 million, or £32 million.

These measures applied over a five-year period, without political interference, would deliver the one million plus additional homes needed Nationally, including the 300,000 plus required for London, as well as a much needed correction in rampant rent and house price inflation. n

Planning reforms: it’s time to think ‘big’

I confess to initially feeling a little daunted, deep into the challenging summer of 2020, by the arrival of the Government’s plans to reform the planning system in England – “Planning for the Future”. The Prime Minister’s foreword promises “Radical reform unlike anything we have seen since the Second World War”, nothing less than “a whole new planning system for England” to be built “from the ground up”. For once the hyperbole might be justified – if carried through, the changes would leave almost no aspect of the current system untouched.

But as the weeks have passed, I’ve warmed to the idea of a complete overhaul. Certainly, as a day-today participant, it’s clear that the current system isn’t working for anyone. It’s overly complex and sometimes opaque, delivering outcomes that are unpredictable and too often disappointing. Communities find themselves excluded and short-changed, council planners are overwhelmed and under-appreciated, and developers frequently frustrated and uncertain.

So, in a spirit of optimism, here’s a brief look at a few of the key proposals which have the potential to lead to positive change in London and elsewhere.

Simple, spatial, accessible plans

The Government wants plans to be shorter, simpler and more visual. They are to identify land under just three categories: “Growth” areas suitable for “substantial development” where outline approval would be automatically secured for certain forms and types of development; “Renewal” areas suitable for some development such as “gentle densification”; and “Protected” areas where development is generally restricted.

It’s clearly impossible to reduce the glorious complexity of a city like London into three “zones”, but a simpler and more explicit spatial vision for the capital would be a welcome successor to the New London Plan, which weighs in at 527 almost entirely textbased pages. This should positively shape and direct growth to the city’s activity nodes and transportation corridors, and establish clear, succinct policies on the most pressing issues - climate change, affordability, and economic resilience.

Creating such a plan would also be a great opportunity to employ the full potential of new technology to capture the imagination and priorities of young people, minority and low-income communities who can so easily be left out of the critical conversations about city building.

Design codes with bite

Much is made in the White Paper of the need to cut red tape, deliver quicker decisions and enable more homes to be built. This is balanced by a desire for a much greater focus on building “beautifully” and sustainably. The quantity-versus-quality tension is to be resolved through locally prepared design codes, produced with “genuine community consultation” and made binding on planning decisions.

Given that broad development rights are to be conferred in principle by the adoption of development plans, the new system will place enormous reliance on design codes to deliver good places. This is both a great opportunity and a huge challenge.

The opportunity lies in the potential for a renewed focus on the power of thoughtfully designed, engaging and attractive places to lift the spirits now and engender pride for generations to come. The challenge will be to discern and communicate what constitutes good design across all the London’s diverse localities, get the buy-in of local people and then give the codes real “bite” in the

Matt Shillito is a Director at Tibbalds Planning and Urban Design

detailed application process. This will require Boroughs to deploy highly-skilled design professionals and great tenacity in the face of competing priorities. A significant programme of training and investment will surely be needed.

A single levy to deliver public goods

The White Paper promises to replace both the current system of planning obligations (secured through S106 Agreements) and the Community Infrastructure Levy with a nationally set, valuebased flat rate charge payable on the occupation of development. The stated aim is to raise more revenue than under the current system and deliver at least as much – if not more – on-site affordable housing as at present. In London, the Mayoral CIL could be retained to fund strategic infrastructure.

For anyone charged with navigating a course through the complexity and uncertainty of the existing regulations, this is perhaps one of the most superficially attractive proposals. The greater clarity and certainty of a set rate would be beneficial to all parties once it factors into land values. Ending the protracted rounds of negotiation and re-negotiation would speed up decision-making. However, calibrating the rate to capture enough value to fund the public goods that are so vital to creating complete communities without discouraging development will be a delicate art.

Realistically, the breadth and depth of the proposed reforms is the work of a decade. They need to be treated as such – thought through in detail, properly funded, and broadly based enough to survive short-term political cycles. But maybe this is the time to think big – a proactive, design-led planning system led by a confident public sector, communities in all their diversity given a real voice and a clear set of rules giving the development industry the certainty it needs. n

BRIEFING BRIEFING

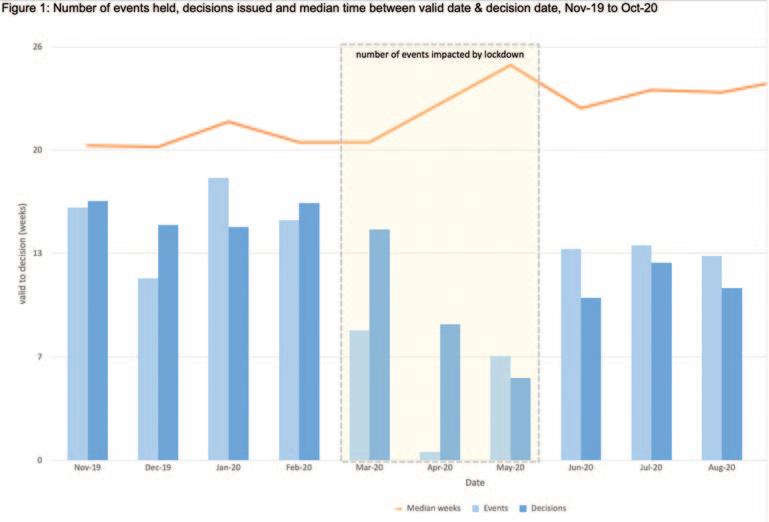

Appeals and timeliness

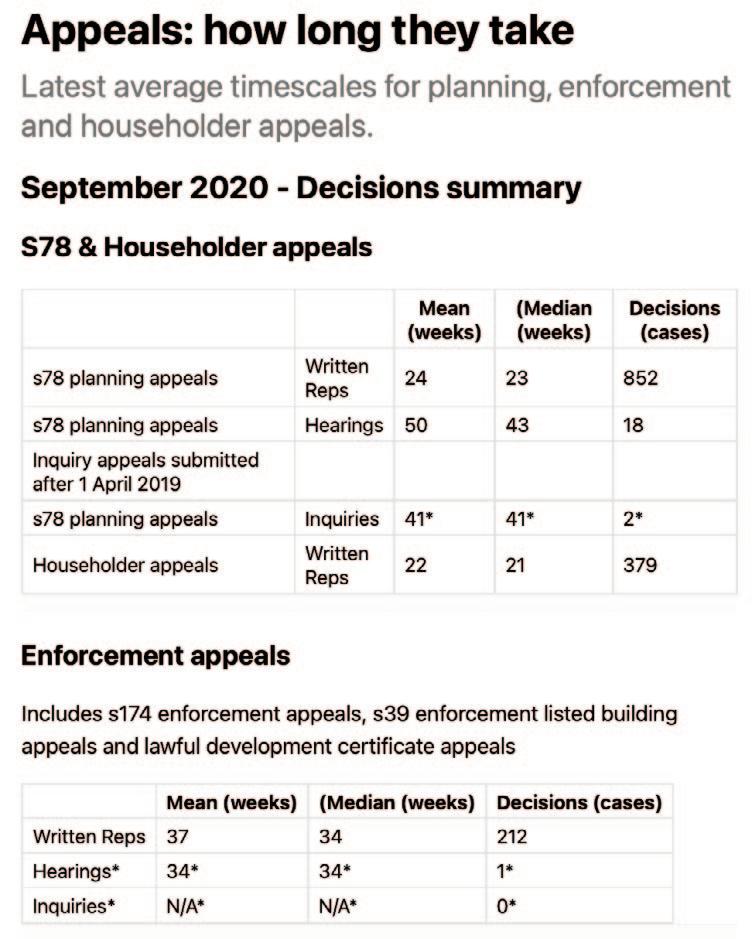

A new statistical release from PINS (the Planninig Inspectorate) provides summary information on appeals, which represent the highest volume (in terms of number of cases) of the work of the Planning Inspectorate. Released at the end of November, it also provides a general overview of the impact of the Covid pandemic on the work of the Planning Inspectorate to enable everyone to see the effect of the restrictions on performance. These statistics will be produced each month to allow anyone to see how the Inspectorate is performing. The focus is on timeliness as that is an area in which stakeholders have an interest. Information on the decisions that we have made is also included; and on the number of Inspectors available to make those decisions. They have been published to ensure everyone has equal access to the information and to support the Planning Inspectorate’s commitment to release information where possible. The statistical bulletin provides: • An overview of the impact of Covid on the work of the Inspectorate • Appeals decisions from November 2019 to October 2020 • The time taken to reach those decisions • Number of open cases • Number of Inspectors • Number of virtual events. The data is only applicable to England.

The Planning Inspectorate

The Planning Inspectorate’s job is to make decisions and provide recommendations and advice on a range of land use planning-related issues across England and Wales. We do this in a fair, open and timely way. It deals with planning appeals, national infrastructure planning applications, examinations of local plans and other planning-related and specialist casework in England and Wales. The Planning Inspectorate is an executive agency, sponsored by the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government and the Welsh Government.

LEFT: Mean Average - The total time taken divided by the number of cases. Also referred to as the ‘average’. A measure of how long each case would take, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/appeals-averagetimescales-for-arranging-inquiries-and-hearings if the total time taken was spread evenly across all cases. Median - The middle value, if the times are sorted. This means that half the cases take less then this time; and half the cases take more. Decisions – number of decisions made. Please note that the times given here are measured from the time an appeal which we are able to progress (‘valid’) to the time a decision is issued. The smaller the number of decisions, the less helpful the mean and median are as measures for summarising performance. Particular care should be taken when there are fewer than twenty decisions. These are represented with an * in the table, but have been provided for completeness and transparency. Each of the measures give a slightly different view of the average time taken to make a decision, both are provided because neither gives a perfect indication of the average. The mean is potentially affected by a small number of cases taking a long time – and this gives an over- estimate. The median is less affected by these few longer cases so may give a more helpful indication of the average. The mean was published previously so we are publishing it to allow users to compare current with previous data. In making use of the data provided, users are reminded that some decisions made in the latest month were on cases submitted a years or more before – as such, while they are the most recent snapshot available, they should not be relied on to give a reliable indication of what will happen to a case submitted recently or in the future. We are reviewing our published information in order to make it more useful and accessible to users – please get in touch with us at https://www.gov.uk/guidance/appeals-averagetimescales-for-arranging-inquiries-and-hearings statistics@planninginspectorate.gov.uk if you have suggestions on how we could improve the information we provide to you. Summary

The impact of COVID can be seen in the Planning Inspectorate data in three ways: 1 The Inspectorate suspended all events during the Spring lockdown, but have since resumed activities, including holding events virtually. The number of events held in September 20 were the highest recorded in the last 12 months at 2,112. 2 In deciding cases that were impacted by the Spring lockdown, and aftereffects of the lockdown, the timeliness measure is starting to increase as the Inspectorate work through the backlog that was created. The median timeliness from April 20 onwards is consistently above 22 weeks, contrasting with the months of November 19 to March 20 where it is never above 21.3 weeks, and usually around 20 weeks. 3 The number of open cases (cases received but not yet closed) increased to a high of around 11,000 in August 20 but is now decreasing, as the Inspectorate are now closing more cases than we receive on a monthly basis.

The Planning Inspectorate has made 17,802 appeal decisions in the last 12 months, an average of almost 1,500 per month. The 1,965 decisions in October are higher than the pre-pandemic levels and the highest in the last 12 months.

Written representations decisions have recovered to, and above, pre-pandemic levels. In contrast there remain fewer decisions from hearings and inquiries. Both planning and enforcement decisions have recovered to pre-pandemic levels; but there remain fewer specialist decisions.

The mean average time to make a decision, across all cases in the last 12 months (Nov 19 to Oct 20), was 26 weeks. The median time is 22 weeks.

The median timeliness from April 20 onwards is consistently above 22 weeks, contrasting with the months of November 19 to March 20 where it is never above 21.3 weeks, and usually around 20 weeks. Hearings and inquires take longer than written representations – with Hearings taking more than twice as long as written representations.

The median time for written representations over the 12 months to October 20 is 22 weeks. The median time for inquiries over the 12 months to October 20 is over a year - 59 weeks. The median time for hearings is slightly less at 42 weeks.

The median time to decision for planning cases is lower than for other casework categories, apart from in May 2020. Across the whole year, the median time to decision for planning cases is 20 weeks. Enforcement decisions made in the last 12 months had a median decision time of 35 weeks. The median time to decision for specialist decisions is broadly the same as for enforcement decisions, and longer (almost double) that for planning decisions.

The median time for Inquiries under the Rosewell Process over the 12 months to October 20 is 26 weeks. Since the COIVD outbreak there have been fewer such decisions and generally longer durations – noting that these inquiries began many weeks before the pandemic had its impact.

At the end of October, the Planning Inspectorate had ten thousand five hundred cases open. This is a reduction of about 400 from the previous month.

There were 347 Planning Inspectors employed by the Inspectorate in October 2020 – with a fulltime equivalent of 310.

The Inspectorate are continuing to increase the number of events carried out ‘virtually’. There were 114 Virtual Events during October 2020, with 102 estimated for November. n

The tortuous process will soon come to an end...

but battles with the government over London’s housing targets in particular look sure to continue says CHARLES WRIGHT writing in OnLondon.co.uk

Sadiq Khan’s London Plan finally looks set for sign-off, more than a year after the Mayor’s “intend to publish” version of his planning blueprint for the capital was submitted to communities secretary Robert Jenrick for approval.

“We expect to agree the London Plan with the Mayor early in the new year,” Jenrick told the Commons last week, after a flurry of December activity which saw Khan set a deadline for publication and the minister, just a day later, adding further new “directions” for changes.

The likely agreement means Khan’s Plan, which began its tortuous journey back in 2017, will be approved just before the next year mayoral election, >>>

BRIEFING

>>> but only by virtue of the 12-month extension of his term due to the pandemic. It will emerge from the process with its targets for new house-building falling far short of current

Whitehall expectations – 52,000 annually compared to the newly-announced government figure of 93,579 a year.

Khan’s original aspiration for 65,000 homes a year had already been pared down by the planning inspectors who scrutinised the draft Plan last year, finding the mayor’s proposed 250% uplift for development in

Outer London, predominately on small sites, unrealistic, and any more than 52,000 new homes a year not credible without encroaching on the Green Belt and/or asking the wider South East to help out.

So what is the basis for the government target, now not only almost twice the draft London Plan figure, but getting on for three times more than the average number of new homes actually built in the capital over the past three years?

It’s all down to Jenrick’s predictable U-turn last week on plans to boost house-building across England via a standard formula for calculating local authority targets across the country – the “mutant algorithm” which ended up allocating the bulk of new construction to the (Tory) shires and suburbs, predominately in the south-east – the opposite of “levelling up”.

Cue backbench outrage, and last week’s rapid reversal, with the government now calling on

England’s cities, and London in particular, to do the heavy lifting in a bid to reach its overall target of 300,000 new homes a year.

The new approach simply adds 35% to the 2017 targets for England’s 20 largest urban centres, producing for London the “heroic figure” of 93,579 homes a year, according to insightful analysis from planning and development consultants Lichfields.

Will these homes ever actually get built? For the capital there’s the now familiar conundrum – where to put more homes while continuing to assert that

London’s housing needs must be met within its own borders and keeping off the Green Belt.

Enter our old friend, “brownfield” land, now coupled with the prospect of a pandemic-induced “profound structural change” for the retail and commercial sector, freeing up sites for residential use, according to the government.

Lichfields are politely sceptical: “It does seem that the structural change sketchily envisaged would at best take time to achieve, whereas the new…figures will need to inform plan making now”.

Furthermore, according to planning lawyer Simon Ricketts expert Simonicity blog, it’s an overall approach which can “no longer be said to be a proper methodological assessment of local need based on demographics and household formation rates.”

And there are political considerations at play in the capital too. With London Tories already criticising Khan’s previous draft Plan as a “war on the suburbs”, and the mayoral election coming up, doubling the Mayor’s target by Whitehall diktat clearly didn’t look to Jenrick like such a good move.

So the new targets come with a crucial fudge, to the effect that Khan’s current Plan gets the go-ahead now, with the uplift applying only to the next London Plan, pushing the application of the new targets back by five years.

Along with Jenrick’s further directions to amend the current draft, giving boroughs the power to restrict tall buildings and spelling out even further that the Green Belt remains sacrosanct on top of previous directions removing Khan’s commitment to preserve current levels of “strategic industrial land”, it seems to have been enough, for now, to placate critics such as Chipping Barnet’s Theresa Villiers.

The five-year delay in implementing the target hike, coupled with the further protections, is a “major victory for all those who are concerned about protecting the character of suburban locations like Barnet,” she said.

Nevertheless, as Jenrick himself told the House, his new formula did mean that in London “there will need to be a much more ambitious approach to delivering the homes the capital needs.” The minister therefore announced he would send in his Homes England national agency, particularly to help kickstart large “brownfield” sites including Old Oak Common, currently administered by a mayoral development corporation.

With Khan effectively instructed to start planning for the new targets as soon as his current draft is approved, the involvement of Homes England, whose powers over the capital were devolved to City Hall in 2011, looks like a further provocation in the Whitehall/City Hall standoff over who really runs London.

The overall settlement too, as Villiers recognises, suggests that the war over strategic planning and new homes targets in the capital is far from over: “There are still battles to be fought over future housing numbers in London after the London Plan expires.”

The evidence, meanwhile, according to expert commentators, suggests that house-building policies must now be taken with a large pinch of salt. “There have to be very significant doubts over the prospect of London hitting that figure given past rates of delivery,” says Lichfields.

And LSE housing specialist Kath Scanlon, writing in the Centre for London’s recent “London’s Mayor at 20” compendium, puts it even more succinctly: “Some time ago the targets crossed the line from aspirational and achievable to hopelessly unrealistic”.

OnLondon.co.uk exists to provide fair and thorough coverage of the UK capital’s politics, development and culture. It depends greatly on donations from readers. Give Ј5 a month or Ј50 a year and you will receive the On London Extra Thursday email, which rounds up London news, views and information from a wide range of sources. Please contact davehillonlondon@gmail.com for payment details.

Schedule_of_modifications_Dec2020_to_'Intendto-Publish'_new_London_Plan may be downloaded here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/tof7xmtm186g8h8/schedule_of_m odifications_dec2020_to_%27intend-to-publish%27_new_london_plan.pdf?dl=0