ISSUE 2

American Essence

Tales of the Founders Drama between prominent friends, and how they finally paid each other the ultimate compliment

Wormslow Plantation in Savannah, Georgia. Chris Moore - Exploring Light Photography/Moment/Getty Images

Wormslow Plantation in Savannah, Georgia. Chris Moore - Exploring Light Photography/Moment/Getty Images

“Where liberty dwells, there is my country.”

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

Contents

12

06

Features

12 Colby Homestead Farms

In 1630, the Winthrop Fleet brought some of the earliest settlers to America. Among them was a man named Anthony Colby. Today, the Colby family farm is going strong, still an active part of its community in upstate New York.

18 Gemstone Dreams

A Romanian massage therapist took a leap of faith and moved to America to explore the glittery world of high-end jewelry.

20 Crafting Custom Furniture: New York’s Classic Sofa Company

At a factory in the Bronx, craftsmen and interior designers customize clients’ hand-crafted furniture every step of the way.

22 Believing in America

The stars aligned for an appreciative group of artists and artisans to pay proper homage to the Declaration of Independence.

26 Escaping Communism

A 30-year-old Tiberiu Czentye risked his life to escape communist Romania, hoping to find a brighter future for his children. Decades later, with his grandchildren in mind, he's telling his story and hoping it will help stem the tide of socialism.

30 Why I Love America

Our country was, in many ways, born in crisis and war while believing in a better way of life.

32 George Washington’s Armor

The forgotten story of a young Washington who saw God’s hand in the course of his life—straight from his own journals and letters.

34 America Opposing Global Communism

At one time in the 20th century, more than 60 countries were ruled by communists. The United States, as the leader of the Free World, took action to stop communism’s spread.

36 History

38 Founding Friends

On July 4, 1776, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams presented to the world one of the most important and enduring statements of human rights and liberty ever written.

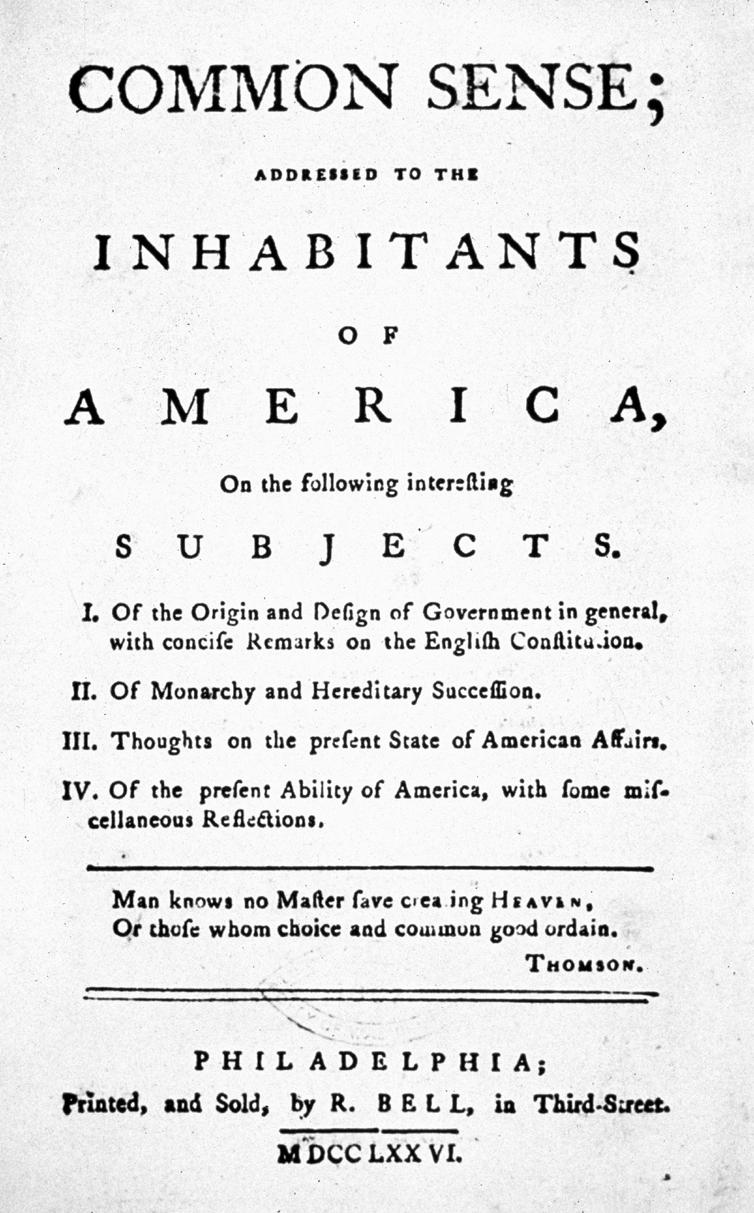

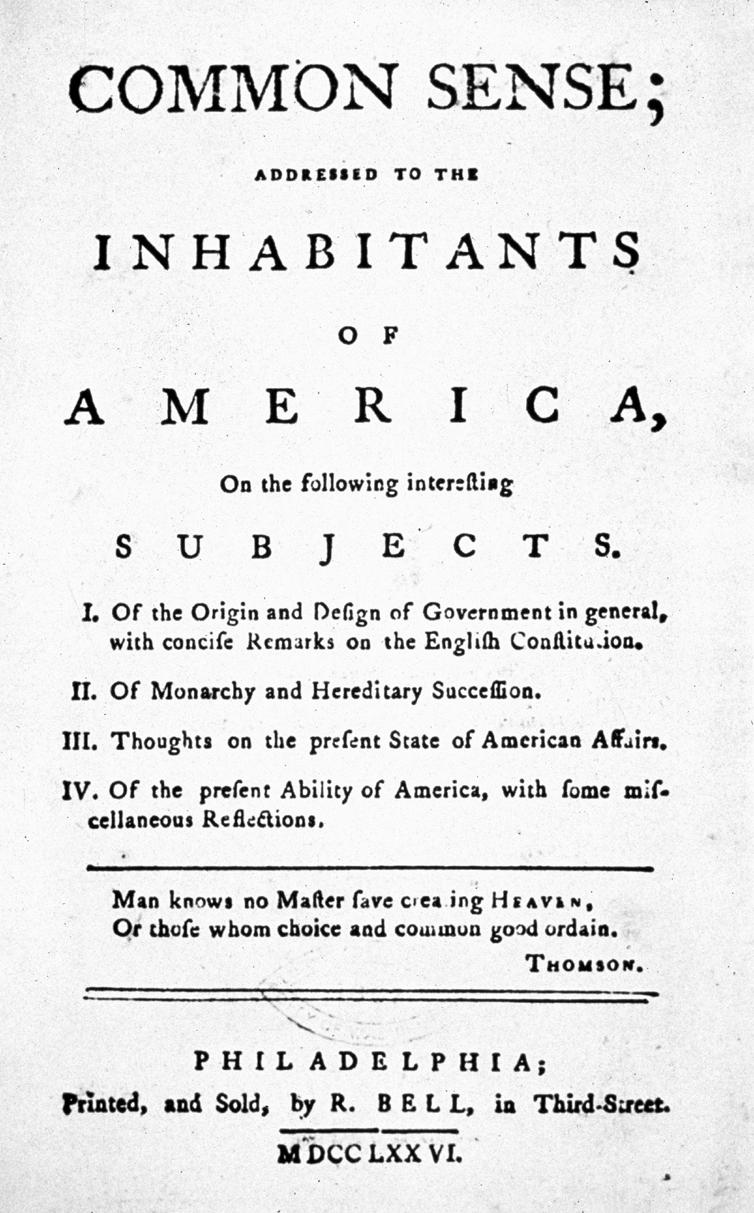

40 Independence and ‘Common Sense’ Thomas Paine, the man who wrote the famous words, “These are the times that try men’s souls,” won the battle for American hearts and minds during the Revolution—twice.

42 A Founder Twice Over George Clymer helped set in motion the chain of events that would ultimately explode into armed revolution. He was one of the few men to sign both the Declaration of Independence and, 11 years later, the Constitution.

44

Arts & Architecture

46 The Capitol’s Statuary Hall

A Colorado congressman gives us a tour of the grand chamber where John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln had desks.

50 Poetry, Almanacks, and Spelling Bees

The cannons of the Revolution barely ceased firing before American texts began replacing their British counterparts in schools and home libraries.

52 The ‘Academical Village’ Ten pavilions, connected by colonnades extending from a great building resembling the Roman Pantheon, rose impressively above the rolling fields of Albemarle County, where Thomas Jefferson built the university he had long dreamed of.

56 House of Beauty Master woodworker Brent Hull introduces us to different American architectural styles, starting with Colonial Revival— popularized at a time when we reflected more deeply on the country’s history.

60 Painter of the Revolution John Trumbull (1756–1843), venerated artist and soldier of the Revolutionary War, depicted pivotal moments from early chapters of American history, immortalizing our origin story in perpetuity.

68 Flickering Flames

Mankind’s need for storytelling is timeless and universal. Stories connect us with myths and legends, tradition and history, telling us truths about ourselves and where we come from, and giving us common ground with our fellow man.

Illustrations by ElenaMedvedeva/iStock/Getty Images

Illustrations by ElenaMedvedeva/iStock/Getty Images

Plus

• Background patterns by jcrosemann/E+/Getty Images

Plus

• Cover image by BackyardProduction/iStock/Getty Images

52

70 The Musical Salesman of Americanism

Take a bright blend of woodwinds and brass at 120 beats per minute, topped with melodies that could have—and in some cases actually did—come from a tuneful operetta, and you have the essential Sousa march.

72

A Love of Learning

74 Homeschooling, a Generation Later

One mother’s realization that she wasn’t as patient, kind, melodious, or natural as Julie Andrews was in “The Sound of Music,” and that her children weren’t engaging, prompted her to take a sobering look at her mission.

76 No Crying in Debate

Debate is the very means by which this country discovered itself, offering freedom and an accompanying explosion of prosperity the world had never before seen

78 Tears and Triumph Over Long Division

How our children feel about success, failure, and learning, depends greatly on us as parents and teachers. We must never forget that what we do and how we react will set the tone.

80 A Rise in Roadschooling

Just because it's called homeschooling, doesn't mean the schooling must always take place in your home—children can learn from anyone and everything, all the time.

82 The Gateway to Empathy

More than watching movies or television shows, more than listening to audiobooks or playing games, reading serves as a magic doorway to empathy.

84 A Homeschooling Journey

Every homeschooling family faces different challenges. Tough decisions are often required when balancing the demands of work and school, finding which methods and materials work best in a domestic classroom, and dealing with each student’s learning style, talents, and needs.

86 The Magnificent South Bay Choir

Through the experience of singing together in this highquality musical collaboration, children come to see and celebrate what is traditionally called “the pure, the bright, the beautiful.”

88 Shakespeare’s ‘Taming of the Shrew’ and Today’s Sensibilities

The story of a man’s choosing a loud and troublesome, but rich and beautiful, girl for his wife, and “taming” her destructive misbehavior, has been for centuries a favorite of audiences. It still has something to say to us even today.

90 Food

92 Legendary Loaves

What holds together New Orleans’s iconic po-boy sandwich? Leidenheimer’s bread, of course. The 125-year-old family-run bakery guards a culinary tradition that is part and parcel of the city’s culture.

96 Recipes: White BBQ Sauce

Chicken

Big Bob Gibson’s Barbecue, in Decatur, Alabama, has popularized a type of white sauce that goes great with barbecued meats. Radio host and foodie Erick Erickson captures its essence for a home-cooked version.

98 Recipes: Smoked Chicken Wings

Piedmont Brewery, a pub in downtown Macon, Georgia, has mastered the crispy-skinned smoked wing. Erick Erickson successfully recreates it.

100 Colonial Cooking

To keep America’s culinary history alive, Colonial Williamsburg maintains two operating kitchens. Resident food historian Frank Clark said, “Learning how people eat tells about their religion, society, and quirks of life.”

104

The Great Outdoors

106 Climbing Lost Arrow Spire

74

When a casual rock climber brought his 10-year-old son on an expedition to Yosemite’s Lost Arrow Spire—which stands 2,700 feet above the valley floor—he learned a few things about what it means to persevere.

110 The Wilds Return

Eastern Kentucky used to be devoid of wildlife, but deer, coyotes, mountain lions, bald eagles, elk, and more are flourishing once again.

Editor’s Note

Dear Readers,

We’re grateful, humbled, and excited by the tremendous response to our new publication—which poured in even before the first issue was printed. My colleagues agree that this magazine has been a long time coming; American Essence was born from readers everywhere asking for the true story of America, for good news featuring their fellow good-hearted Americans, and thus the magazine became a reality as quickly as the idea had formed. On the eve of the anniversary of the country’s beginnings, we’re reminded of our founding documents and the formative power of putting pen to paper.

In our History section, George Wentz explores the friendship between the two founders originally tasked with writing the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were friends before they were fierce political rivals, and later became friends again. They died just hours apart on our 50th Independence Day, each rumored to have referred to the other with his last breath (p38).

America’s ideals are those that move people from all around the world. Spanish artist José-María Cundín’s father often joked about how his birthday coincided with America’s. Cundín himself had lived under a dictatorship in Spain, so he was moved when he read the words of the Declaration of Independence, and spent three years engraving a facsimile (p22).

The founding of the nation was captured in more than words. John Trumbull was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, and a skilled painter—his rendering of Congress receiving the Declaration of Independence is well known. The prolific artist’s works capture the birth of a free and independent country, and a new chapter in world history (p60).

We hope you will join us on this journey.

Catherine Yang

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 4 / ISSUE 2

Illustrations by Michelle Xu and rustemgurler/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

American Essence

PUBLISHER

Dana Cheng

EDITORIAL

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ARTS EDITORS

HISTORY & LITERATURE EDITOR

FAMILY & EDUCATION EDITOR

FOOD & WINE EDITOR

ARCHITECTURE & INTERIORS EDITOR

SMALL FARMS EDITOR

TRAVEL EDITOR

ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR

EDITOR-AT-LARGE STAFF WRITER

Catherine Yang

Sharon Kilarski

Johanna Schwaiger

Jennifer Schneider

Robert Mackey

Channaly Philipp

Crystal Shi

Annie Wu

José Rivera

Cary Dunst

Ben Zgodny

Tynan Beatty

Skylar Parker

CREATIVE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR DESIGNERS

ILLUSTRATOR

PHOTO EDITORS

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Justin Morgan

Ingrid Phillips

Tianzhen Xiong

Kathy Sow

Fiarbei Yauheni

Putu Prawira Adi Duta

Daniel Ulrich

Chantelle Doucette

Tal Atzom

CONTRIBUTORS

Erin Tallman, Vance Hawk, George Wentz, W. Kesler Jackson, Ken Buck, Bob Kirchman, Brent Hull, Kara Blakley, Cary Solomon, Chuck Konzelman, Kenneth LaFave, Evelyn Glover, Sam Sorbo, Charles Mickles, Juliette Fairley, Gina Prosch, Jeff Minick, Raymond Beegle, Gideon Rappaport, Melanie Young, Erick Erickson, Alexandra Greeley, Benton Crane, Chris Musgrave 229 W 28th St, 7th

OFFICE & CONTACT

Floor, New York, NY 10001

Features

“America is another name for opportunity. Our whole history appears like a last effort of divine providence on behalf of the human race.”

RALPH WALDO EMERSON, ESSAYIST AND PHILOSOPHER

All cover page illustrations by bauhaus1000/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

Train Conductor Returns Rings Worth $107,000 to Passenger

Upon receiving the returned rings, Eleasian gave a heartfelt hug to the assistant conductor in appreciation.

Jonathan Yellowday, assistant conductor, was working the 6:11 p.m. Long Island Railroad (LIRR) train from Penn Station, New York, to Port Washington, when he discovered a tray of engagement rings, valued at $107,000, in a plastic bag. The rings belonged to Ed Eleasian, a jeweler who runs his trade in an office in Midtown Manhattan. Eleasian had left the rings on his way home on April 22. The LIRR conductor turned in the package to the Metropolitan Transport Authority (MTA) police as soon as possible. “I got on the next train going back to Penn, turned it in, and the rest is history,” said Yellowday in a press release.

Eleasian and his wife took the LIRR to Penn Station on the Friday after-

noon of April 23 to retrieve the lost items. There, they were met there by Yellowday and LIRR president Phil Eng. “Not only did you find and return these 36 rings, but just think about the happiness of 36 couples down the road that will be joined together in happiness, and they will have a story to tell,” said Eng. “You treated this as you should have, and it is another proud day for us at the railroad.” Upon receiving the returned rings, Eleasian gave a heartfelt hug to the assistant conductor in appreciation.

“I could only imagine what you were going through yesterday when you realized that you didn’t have your jewelry,” Yellowday told him. “You know when you get on the 6:11 you are in good hands.”

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 8 / ISSUE 2 FEATURES KINDNESS IN ACTION

(L-R) Chantelle Doucette, Noppadon Daodas/EyeEm/Getty Images, NoSystem images/E+/Getty Images

Identical Twins

Reunited After 36 Years

Identical twin sisters, who were separated at birth, recently met each other for the first time on their 36th birthday, after decades of living separate lives.Molly Sinert and Emily Bushnell, born in South Korea, were adopted by two different families. Sinert was adopted in Florida, while Bushnell lived in Pennsylvania. Until recently, each sister had no idea that the other even existed. The curiosity of Bushnell’s 11-year-old daughter Isabel led to the discovery. Isabel “wanted to do the DNA test because [her mother] was adopted," she told Good Morning America. "I wanted to find out if I had more family on her side.," she added.

Sinert also decided to have a DNA test, and she was stumped by the results. “I clicked on the close relative and didn’t understand it,” she said. “‘You share 49.96 percent DNA with this person. We predict that she is your daughter.’ This wais obviously not right, because I have never gone into labor, I don’t have children,” she said. She reached out via email, and learned it was her twin sister’s daughter. The twins then agreed to meet on their 36th birthday. “Although I have family who love me and adore me and haves been absolutely wonderful, there was always a feeling of disconnection," said Bushnell. "Finding out that I had an identical twin sister just made everything so clear. It all makes sense.”

The twins' reunion was witnessed by ABC, during which the sisters said, “It is like looking in a mirror.” “My life changed,” Sinert told ABC. Bushnell couldn't hide her joy: “A hole was immediately filled in my heart.”

Ohio Couple Opens Home to 100 Foster Children

On Ann and Al Hill’s home hangs a sign: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers.” Ann is 78 and Al is 79; they were both born in Georgia, but only met when they moved to Cincinnati and attended the same high school. She wrote to him after he was drafted into the military, and sent him baked goods when he was overseas; they’ve been married now for 53 years. When their two daughters went to college, the home felt empty. To open their home to children who needed it was a simple matter for the Hills. “You know what you learn?” Al told The Enquirer. “There are so many people with nowhere to go.” The Hills were strict, but they governed with love, fostering nearly 100 girls for about three decades—and only stopping last year. The girls still call, and some even visit for Thanksgiving.

Thanking the Pandemic Volunteers

During the peak of the pandemic, schools were closed and many of their fields were neglected, but Fort Hood’s Lori Harrison took it upon herself to mow, weed, and clear an overgrown softball complex so children could have a place to play. Harrison was recently awarded for her volunteerism, to her great surprise. “I just see a need and I fill it,” she told Fort Hood Sentinel. Harrison volunteered 800 hours of her time over the past year—she's been an Army Volunteer for more than 24 years. Like Harrison, many across the country saw new needs during the pandemic, and unconditionally stepped up to fill them.

In Gunnison County, Colorado, Arden Anderson immediately lent his decades of emergency-response expertise when the County needed to respond to the pandemic, volunteering to manage hundreds of volunteers across all the departments that would need help. “We knew that we were going to need some volunteer help from the beginning,” he told Crested Butte News. “Typically in an emergency, if we have a need, we will reach out to an adjacent area for mutual aid. And that works for a wildfire or a chemical spill that is just localized. But in a worldwide pandemic, everyone was in the same boat. We

really weren’t sure how many people would answer the call for volunteers.” Quite a few, as it turned out: since March 2020, 758 people together gave more than 25,000 hours of their time. Anderson himself volunteered for 460 days, and was recently honored by the county for his tireless work. “I don’t think that volunteerism is something new in the Gunnison Valley. But I think that we benefit here from people who have more of a sense of community, and know that we don’t have the big bucks of a larger city ... so over the years, more and more people have gotten in the habit of helping out, and that culminated with the pandemic. But when you look at the number of people who show up for clean-up days, for the Center for the Arts, for trail building, for the Wildflower Festival—you see that.”

As states continue to open up, many organizations across the country are putting out calls for volunteers to make up for lost time and meet new needs. Young volunteers have done their part too. Delaware recently awarded 10 individuals, four groups, and five leaders for youth volunteer service, noting that 3,544 young people together contributed 643,863 hours last year: “in economic terms, these volunteers contributed $29 million in service to Delaware [over the past year].” These young people collected and delivered food and necessities, sanitized and landscaped public facilities, found creative ways to enable birthday and other celebrations during social distancing, and raised money for various programs. “Their commitment is helping us to build a stronger community through volunteerism, as well as to develop the next generation of leaders,” said Kanani Hines Munford, Executive Director of the Governor’s Commission on Community and Volunteer Service.

(L-R)

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 10 / ISSUE 2 FEATURES KINDNESS IN ACTION

South_agency/E+/Getty Images, Jose Luis Pelaez Inc/DigitalVision/Getty Images, photopeak/Moment/Getty Images, Catherine Ledner/DigitalVision/Getty Images

Jessica Hicks, a California woman, grew up with very little knowledge of where she came from, until a search for answers proved fruitful. Recently she met the man who found her 30 years ago, when she was a newborn with her umbilical cord still attached, abandoned in the bushes. Now a mother of six from Moreno Valley, Hicks took the kindhearted Isaac Oliva by surprise when she called him in late April to confirm his identity.

Woman Reunites With Good Samaritan Who Saved Her Life Surfer Saves Man From Rip Current

AUpon learning that Hicks was the baby he found wrapped in blankets behind an Irwindale building back in 1990, Oliva was overwhelmed, reported KABC-TV. "I was just full of emotions, and my jaw just dropped," Oliva told the news outlet. Meeting on April 28, Hicks and Oliva embraced, and swapped impressions of the amazing story that brought them together.

Glenn Purbaugh, the now-retired Irwindale police detective who investigated Hicks's case, also attended the reunion. The Irwindale Police Department shared photos in a social media statement, of the trio standing at the exact spot where Hicks was found. "We have to admit that we love a happy ending," the police department wrote.

While overwhelmed, Hicks said the reunion helped complete the mystery of how her life began. Weighing 9 pounds, 4 ounces when she was found, sunburned but healthy, Hicks was dubbed "Jane Doe" by the media and the hospital that took her into its care. Never reunited with her birth parents, at 15 months of age she was adopted by a woman named Julie Swallow, reported KABC-TV. "She was a blessing from God and L.A. County," Swallow told the news outlet. "I love her very much, like she was my very own."

n ash-spreading ceremony almost turned tragic on May 21 in Corolla, North Carolina, when one of the deceased's family members became caught in a rip current at the beach, surviving thanks to a local surfer. Dennis Kane, 71, his daughter Shannon Kane Smith, and another 40 family members had gathered to spread the ashes of Dennis's deceased daughter, Kerry Kane, into the sea. Kerry, who had died a year earlier at age 41, was fond of the Outer Banks beach, so the family chose it as her final resting place.

Kerry's ashes were contained in a biodegradable urn, which was to be dropped to the ocean floor. “That is when my dad, my sister Kelsey, my sister Lauren, and I walked into the ocean with the urn,” Shannon told ABC. After several minutes at the beach, though, the tide started getting rough and moving in fast, and the family decided to get out of the water.

Upon moving inland, Dennis noticed that the urn had not sunk properly, as it should have, so he went back to push it down. “You can imagine how emotional, upsetting that might have been for anybody, it certainly was for him,” said Michael Kane, his younger brother. “I think he was distressed that the urn was still floating in the ocean, and he did not want it to wash up in the shore.”

At that point, the tides became quite rough, and the farther out Dennis waded, the more dangerous it became. Soon realizing that he was caught up in a rip current, the family began calling out for help. Luckily, a nearby stranger was stowing some beach rentals at the business where he works. “I turned around, I knew I had a board close by, went and got that,” said the rescuer, Adam Zboyovski.

In a rescue mission that lasted around 40 minutes, Zboyovski managed to reach the flagging older man, who was near drowning, and pull him to safety. “I don’t know, I am glad they could still have their father, brother, and grandfather,” Zboyovski said. “It sometimes brings a tear to my eye.”

After the rescue, Shannon praised the courageous man for saving her father’s life. “Not all heroes wear capes, sometimes they have surfboards,” she wrote in a Facebook post. “He is an angel. Please help me make this go viral.”

Colby

Farms

The American Spirit, Alive and Well

Colby Homestead Farms in upstate New York will be passed on to the eighth generation of a family that can trace its American roots to 1630, from some of the earliest settlers of the Winthrop Fleet

WRITTEN BY JOSÉ RIVERA / PHOTOGRAPHED BY DANIEL ULRICH

Imagine a company that has been around for as long as the United States Capitol, is as old as West Point Academy, and is still family-owned and -operated today. There’s such a farm in Spencerport, New York, conducting business 219 years after its founding. In the beginning, it was a small family farm started by several brothers who bravely traveled from Salisbury, Massachusetts, to Western New York, where they purchased land and began clearing that land for a farm.

For 219 years, Colby Homestead Farms has continued farming while living and participating in their community. They cultivated the land decades before the town was founded, and they’ve been contributing to local community, business, government, and faith-based activities for the past two centuries. Addressing the challenges and opportunities of each generation hasn’t always been easy, but from the American Civil War to World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the present day, the Colby family has remained active in their community in many ways.

1600s to 1800s: Earliest Beginnings

The Colby family can trace their lineage back to a man named Anthony Colby who came to America among the earliest settlers with the Winthrop Fleet in 1630. Sometime later, around 1640, Anthony settled in Salisbury, where he planted his family’s roots. The Colbys remained there for approximately 150 years until they made a difficult and dangerous

decision to move west, to what was then an undeveloped part of America. The original family home was donated to the Bartlett Cemetery Association, in 1899, as a memorial to the Colby and Macy families.

Several brothers made the trek to Western New York in the early summer of 1802. While clearing the land they bought, they used the fresh lumber to build a new family home. There was little time for them to rest though, because as soon as they finished building they rushed back to Salisbury—just in time for Thanksgiving—and had their families pack all their belongings and load up wagons for a perilous journey. The Colbys took off just after the new year. It should be noted that, at the time, there were neither heated interiors nor snow tires—they traveled by horse-drawn carriage.

They raced to Mount Morris, New York, trying to beat the spring so they could cross the Genesee River while it was iced over. Since the route had no bridges back then, had the ice melted, the Colbys would have been stuck until the following winter. They made it across the river and arrived at their new home ahead of the spring planting season. In the early years of the farm, the Colbys focused on increasing the arable land area and building more houses for the brothers and their families. Up until the 1800s, the brothers and their children farmed and did their best to slowly improve the land and grow enough food for their own needs. At this time, the area was also gaining other farmers, and the community started developing into the towns seen today.

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 12 / ISSUE 2

FEATURES SMALL FARMS

Seventh-generation head of Colby Homestead Farms, Robert Colby, in the building-sized refrigerator where cabbage is stored until ready for market.

Seventh-generation head of Colby Homestead Farms, Robert Colby, in the building-sized refrigerator where cabbage is stored until ready for market.

RIGHT The dairy farm portion of the business has some of the strictest protocols for ensuring and maintaining quality when getting milk products to market. They’ve incorporated a robotic milking station that uses lasers and state-of-the-art robotics to locate, sanitize, and milk the cows.

1800s to 2000s

In the early 1860s, one brother’s grandson, Oscar Colby, was serving in the Union Army during the American Civil War. While performing his duties, Oscar was wounded—shot in the leg during a battle—but a fellow soldier dragged him from the field, saving his life. Oscar asked the man his name and promised he would name his first son after him. Oscar returned to the farm after the war, with shrapnel remaining in his leg because he hadn’t sought medical attention for the wound. That decision may also have helped him survive; at the time, many soldiers didn’t die from their wounds directly, but rather from infections that took hold after receiving medical treatment.

The Colby family has had its morals and values centered on their faith, family and community from the very beginning. From being involved in the development of governance at the local, county, and state levels, as towns sprung up around them, they served as Justices of the peace and postmasters, among other posts. Through the decades and every generation, the Colby family has volunteered, served, and worked with the community at all levels to improve the lives of those living around them.

The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl of the early 1930s had a massive impact on the family. At that time, the entire American economy was faltering, employment was almost nonexistent, and basic necessities like food were hard to come by. The Dust Bowl was a phenomenon during which a major drought struck the Great Plains. High winds compounded the situation, causing massive dust storms to sweep across American cities, including Chicago, New York, and St. Louis. Everything was left covered in dust—some of which originated from as far away as Oklahoma, Texas, and even Colorado. During those hard times, the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the Colby family farm helped them grow, as they took their products directly to customers, selling on street corners in nearby larger cities. This method saw the farm prosper during a time when many farmers were los-

ing their livelihoods and moving to cities in hopes of finding work in factories.

Hard times never last but hardworking people do. It was due to the family’s industrious nature that their farm grew and diversified. They grew new crops, took up dairy farming, added chicken coops, modernized certain aspects of their thenover-100-year-old farm, and laid the groundwork for a brighter future.

By the 1970s, the seventh and current head of the farm, Robert Colby, had further expanded and modernized the farm with animal husbandry, new equipment, technologies to improve land management and utilization, more efficient methods of managing the growing dairy operations, and even storage and refrigeration to help preserve certain types of crops.

2000s and Beyond

The Colby’s have continued to develop the farm with innovations and improvements, and the future looks bright. Today, a visitor to Colby Homestead Farms might find Fitbit-sporting cows navigating a maze as they make their rounds to the milking robots they’ve been trained to comply with or any number of other new farming techniques aimed at efficiency and higher yields.

Some things are in the experimental phase— while the milking robots complete their tasks on a regular basis, they’re responsible for only a small part of the farm’s entire dairy business for the time being. To begin with, the robotic dairy program monitors cows in the test facility. The cows wear devices similar to Fitbits that monitor certain health vitals and count each cow’s daily number of steps, as sometimes this can be an important indicator of an animal’s health. This data is all fed into a computer and tracked. The cows are taught to run through a series of one-way gates to get to the milking station. The course is more like a maze, and the cows are guided along until they learn the way through—and like any good maze, there’s a prize at the end. Cows earn a slightly sweeter feed for making it through

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 14 / ISSUE 2 FEATURES SMALL FARMS

A visitor to Colby Homestead Farms might find Fitbit-sporting cows navigating a maze as they make their rounds to the milking robots they’ve been trained to comply with.

15 FEATURES SMALL FARMS

TOP & FAR RIGHT

The farm also uses technology to improve productivity and yields.

BOTTOM LEFT & RIGHT

The family logo was designed by Robert Colby’s mother and is still in use today; Sarah, an eighth-generation Colby, manages the dairy farm, marketing, and most administrative duties.

the maze and getting milked. The treat provides an incentive for cows in the program to come and have their milk collected, motivating them to run the course and stay healthy.

One robot is responsible for cleaning, sanitizing, and actually milking the cows. It uses state-of-theart technology to locate a cow’s udder, sanitize it, position the milking tools, collect milk, and mea-

sure the volume gathered from each cow. Afterward, the robot rewards the cow with a sweet treat.

Another robot is similar to a carpet-cleaning machine, except this one pushes cow manure into troughs along the floor; several times a day the troughs get cleaned, after which the manure is transformed into fertilizer to be used in the fields at a later date. This is a pilot program being evaluated for future use.

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 16 / ISSUE 2 FEATURES

Robert is now getting ready to hand the torch to the next generation. In this case, one of the people who’ll be taking over the farm is his daughter Sarah. She has been managing the dairy farm for the last few years while developing her skills in human resources, management, and marketing. Day-to-day, she runs the entire dairy part of the business. She handles most of the hiring and training of employees and is

handling more of the paperwork side of things as well. She’s not alone, as there are also other family members working on the farm. But even as Sarah prepares to take over the farm, she’s also a mother. And while her children are young now, there’s no doubt that the Colby family farm will celebrate its third century as a working farm and business, still being run by the same family eight generations later.

FEATURES

Gemstone Dreams

How a Romanian immigrant discovered a new path in America

WRITTEN BY ANNIE WU

Dorian Filip was a massage therapist in 2009, working aboard the Seabourn Odyssey on its maiden voyage around the Mediterranean. After some years in the industry, he had developed aches in his neck, shoulder, and hands that were increasingly painful, and thoughts of quitting were on his mind.

“I said, ‘If nothing works, I’ll go to the army—I’ll go spend five years there, and they’ll give me a pension after.’”

One fateful day, Filip was assigned to take care of one of the cruise passengers, Brian Albert, who had booked a spa appointment. The two struck up a conversation about life plans. Albert is a wholesale jewelry dealer, with an eye for spotting beautiful things from a young age; when he was 16, he started buying up trinkets at junk shops and selling them to family and friends.

Albert invited Filip to come to New York and learn the trade. Filip was unsure if this was his path, but Albert encouraged him.

“He asked me, ‘What do you like in life?’ And I said a few things that I liked,” such as cars and watches, Filip said. “He said, ‘If you like and understand those things, you’ll understand jewelry too.’”

American Dream

Filip took a leap of faith; about three months after that cruise, he flew to New York from his home country of Romania.

“In the beginning, I couldn’t really tell what was costume jewelry or what was really fine jewelry,” he said, referring to jewelry made with imitation gems or inexpensive materials, versus pieces crafted with precious metals and gemstones. “It was a little confusing.” Albert brought Filip to trade shows, antique shows, and estate sales, showing him the ropes of how to procure exquisite pieces for a bevy of Madison Avenue fine jewelers.

Albert tends to buy from estates and other dealers, so as to procure for his clients one-of-a-kind items they haven’t seen before. He also taught Filip the importance of maintaining long-term relationships with clients—Albert is the kind of person who would throw cocktail parties for cruise staff, or meet a maitre d’, become fast friends, and sometime later end up on a vacation in Hungary together.

“We have been dealing with the same people ... for 30, 40 years, and even longer,” Albert said.

There are plenty of fascinating stories from traveling around the world in search of beautiful jewelry. Albert recounted a time when he was visiting Turkey while on a cruise trip. He walked into a local shop and began chatting with the store operator.

“He pulled the box out of the safe and in the safe were some of the prettiest things you ever saw. There was a sautoir necklace with pearl and diamond tassels,” Albert said, getting excited as he recalled spotting the rare find. At the time, Albert didn’t have any money with him and had to return to the cruise ship soon, but the shop operator let Albert take the piece, telling him to send a check to his sister in the United States.

Sometimes “there’s this feeling you get when you do business with people, there’s a certain comfort level,” Albert said. Filip and Albert both deeply believe it was destiny that led to these seemingly happenstance discoveries—and also brought them together.

“When I met Brian the very first time, I had the feeling I knew Brian a long time already. ... I guess people connect at the right time,” Filip said.

A New Venture

In 2010, Filip experienced his next life-changing event. While having dinner at a restaurant with Albert, he met the hostess, Alexandrina, who was

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 18 / ISSUE 2

FEATURES

As believers in traditional craftsmanship, they hope that more ordinary consumers will make wise investments and buy old.

working part-time there while pursuing a career in fashion. The two immediately connected, having both come from former Soviet countries— Alexandrina is from Moldova. Although they were good friends from the start, it was a business trip to Australia that made Filip realize how much he missed Alexandrina. The couple grew closer, and in 2015, they were married.

Around 2013, Filip and Albert opened a retail shop for the first time, DSF Antique Jewelry. With Alexandrina on board, the shop expanded its offerings to vintage designer handbags, costume jewelry, and other accessories. Albert does much of the sourcing, while the couple handles day-to-day operations. Amid the pandemic, they had to close the physical store, but have kept their online shop going.

As believers in traditional craftsmanship, they hope that more ordinary consumers will make

wise investments and buy old. Antique pieces don’t have the costs of manufacturing or advertising in their price tags, and thus represent greater value for the money. Alexandrina said that among their clients, “the younger generation are more responsive to this ... because they want a part of history, they want something that nobody else has. And it’s fashionable.”

Albert said that from his experience, antique pieces tend to exhibit finer workmanship: “They’re made by hand, they’re one of a kind.” People also cared for and maintained their valuables back in the day.

“Years ago, people bought things and they took care of them. That’s why so many of the old pieces that we buy, that come from the original families, are so well-preserved and loved—because they appreciated that.”

19

ABOVE Dorian and Alexandrina Filip, the couple behind DSF Antique Jewelry, at their apartment in New York City. Alexandrina is wearing vintage Chanel earrings. Chantelle Doucette

Crafting Custom Furniture

New York’s Classic Sofa Company

Classic Sofa’s in-house craftsmen and interior designers—including the company’s own president— customize the furniture-making process every step of the way

WRITTEN BY ERIN TALLMAN

The design company Classic Sofa was a family business with over 20 years of experience producing handcrafted bespoke furniture by the time it was handed down to a second generation in 2007. The timing couldn’t have been worse. The United States suffered a subprime mortgage crisis in 2007 that would lead to a global financial crisis the following year. The challenge of a major recession proved too difficult to overcome, and Classic Sofa’s owners had to put the business up for sale in 2012.

One person’s misfortune can become another’s gain. Blake Anding didn’t set out to become a furniture designer. In fact, he studied biomedical engineering and worked in finance for many years—until he decided he needed to make a life change. In 2012, he saw Classic Sofa for sale and, despite having no experience in design, bought it. He had a lot to learn, but he knew what he had to do to revive the company’s roots as a leader in the custom upholstery industry.

“When I took ownership, I called people who worked with Classic Sofa in the past and picked the best upholsterers and the two best framers to come back to work with us,” Anding told American Essence in a phone interview. Besides sofas, the firm also customizes upholstered chairs, pillows, and draperies.

Many of the craftsmen started young and learned from family members in the trade. The worker with the least experience at Classic Sofa still has more than ten years’ experience, while the staff with the most has worked for 50 years, with an average of 30 years. “Some of them started very young in a for-

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 20 / ISSUE 2

eign country and migrated to the United States,” he said. There was a Jamaican Jewish artisan, William Jobson, who mentored Anding in how to do framing and tufting, as well as Denise Ramirez, who taught him how to do upholstery. “She first came for a job at this factory when she was 12 years old. She put tons of makeup on to look older, but the owner at the time came up to her and, with just the tip of his finger, swiped it off her cheek and told her to come in a few years when she was older.”

Anding has grown the business over the last ten years and has had the pleasure of watching it flourish. The firm has worked with renowned interior designers on high-profile projects—providing upholstery to the Trump SoHo hotel (now The Dominick hotel); sofas and cushions for the rooms in The London NYC hotel (which has since been rebranded a Conrad hotel); and a sofa and loveseat for talk show host Andy Cohen’s Manhattan apartment.

But what the company is most proud of is its quick lead times. After receiving the fabric, it can produce and deliver completed projects in three to four weeks, compared to the average 12 to 16 weeks for competitors. “It’s unheard of in our industry. It’s a very fine-tuned machine because we have the right people working on the projects: getting materials in, for example, so projects get delivered quickly.”

He mostly works with clients in the tri-state area as well as Florida and California, as the vast majority of his clients have homes in the United States, but he has also shipped furniture to Paris and London. The firm only does 100 percent custom bespoke, from fabric to wooden pieces, for residential and commercial projects. The furniture is bench-made, meaning produced to requested design specifications, and manufactured locally in the Bronx by master craftsmen. “I work in the factory with them to ensure the quality of our products every step of the way,” Anding said.

Before going to the showroom, clients can submit ideas to the company via its website, so when they arrive at the firm’s Manhattan design center, they’ll only need to work with interior designers to determine specific details such as seating dimensions, cushion densities, and fabric selection. Another major selling point is that the company offers a lifetime guarantee on frames and springing.

Clients can request an in-home consultation with a member of Classic Sofa’s design team and get assistance on style, cushion fill, and fabric choice for a new piece or reupholstery for an existing piece. The company also has a whole host of fabric partners, including Brunschwig & Fils, Coraggio, Designtex, Ralph Lauren, and many more. These brands have

their own custom furniture collection with Classic Sofa—for the clients who aren’t looking for a fully unique product.

Uniqueness, though, is Classic Sofa’s specialty. The more challenging the project, the more fun Anding has when transforming clients’ ideas into products. According to Anding, that’s the best part of the job.

“One of my favorite projects was for actress Mary-Louise Parker’s new Brooklyn residence. She wanted a [Vladimir] Kagan-inspired piece but with loose seat cushions for comfort. Most importantly, the piece was oversized, stretching across her entire living room.” Anding needed to trace out a sectional design with the perfect curvature and proportional size to fit the aesthetic and size of the room. The sofa had to be designed and produced in pieces and upholstered onsite.

“Designing bespoke furniture is about understanding your client so you can distill what they see as beautiful into each piece that you make. Most importantly, this is a labor of love, from drafting the initial design, through framing and upholstery, to seeing smiles on client’s faces on delivery,” he said.

Erin Tallman is the editor-in-chief of ArchiExpo e-Magazine, an online news source for architecture and design professionals. She is based in Marseille, France, and enjoys cycling around Europe as a way to soak up the culture, discovering hotel gems along the way.

21

LEFT An elegant velvet sofa by Classic Sofa. Courtesy of Classic Sofa

FEATURES

RIGHT Craftspeople working at Classic Sofa's Bronx factory in New York City. Chantelle Doucette

Believing in America

The stars aligned for a group of artists and artisans to pay proper homage to the Declaration of Independence

WRITTEN BY ANNIE WU

Back in 1992, artist José-María Cundín, originally from the Basque Country, Spain, released a hand-engraved facsimile of the United States Declaration of Independence, after three years of hard work and collaboration with craftsmen from his homeland—a papermaker and a renowned metal engraver. But the project didn’t draw broader interest from the American public.

Sara Fattori, who owned a fine art gallery in Palm Beach, Florida, before starting her interior design business, knew of Cundín’s work, but it wasn’t until her father’s passing, around 2007, that she pondered more deeply the meaning of the country’s founding document and the possibility of promoting Cundín’s hand-engraved version. Her father had fought in World War II and was part of an aviation force in the Normandy invasion. “The reality of war,” she said, and the sac -

rifices made by previous generations to preserve freedom, moved her.

The Perfect Frame

Around 2014, when an opportunity arose to donate a Cundín engraving for an auction event benefiting the Carson Scholars Fund’s initiative to promote literacy in low-income neighborhoods, Fattori began searching for a frame worthy of encasing the document. While researching online, she discovered Marcelo Bavaro, a fourth-generation historical frame maker based in New York, whose Italian family inherited a century of craftsmanship in carpentry and gilding. Fattori instinctively knew he was the right fit.

When they met, Bavaro said the Declaration should be encased in a Federal-style frame befitting the time period when the original document was drafted—the

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 22 / ISSUE 2

FEATURES

newly formed country wanted to distinguish itself from its former ruler, so a style emphasizing simple, clean lines was popularized, contrasting sharply with ornate British detailing. “I knew I was with the right person when Marcelo said, ‘Oh, it should be in a Federal-style frame,’” Fattori said during a recent interview at Bavaro’s Brooklyn firm Quebracho Inc., which restores and makes frames for top museums, art galleries, and auction houses.

Bavaro was intrigued by the project: “I always wondered how this country was guided by this piece of paper for centuries. And everybody respects it. I come from a country where nobody respects anything.” He was referring to Argentina—his family emigrated there in the early 20th century. In the early 1980s, when Argentina was under military rule, Bavaro himself was caught in the political turmoil and jailed for writing articles that criticized the government. Due to his family’s influence, he managed to escape and was on the run for five days before crossing the Brazilian border and taking a plane to the United States, where he met up with his father, the first of his family to settle here. Federal-style frames require incredible carpentry skills; an artisan must shape the wood into a narrow concave shape. There are few workshops left in the world that are still engaged in this artwork. “Craftsmanship is something that is dying out,” Bavaro said. “It’s so simple to make money sitting in front of a computer; why are you going to break your hands doing what we do?”

While working on the Declaration project in 2014, Bavaro, together with Fattori and her husband, Paul, joined forces to launch a new company, Fattori Fine Frames, that would provide custom-made, handcrafted frames for people looking to frame artwork and mirrors in their homes.

The auction event that took place the following year was a success, with a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution buying the framed document.

History

Cundín’s facsimile is a copy of William J. Stone’s engraving—the latter was commissioned by then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams during the 1820s as an official government copy, because Adams had grown concerned over the fragile condition of the original Declaration. In Stone’s tradition, Cundín set out to make a hand-engraved brass plate—it would be the first such engraving since Stone’s time.

Cundín always had a personal connection to America, even before becoming a citizen in 1971. His father was born on July 4 and frequently joked about how his birthday coincided with that of

America’s. Cundín was moved by the content of the Declaration upon reading it in its entirety. “The demand for freedom—that is the connection that I found most touching in my heart,” he said in a recent phone interview.

When he began the engraving project in 1989, out of curiosity he started researching the founding fathers who signed the document. Cundín found out that John Adams had visited the Basque Country in 1780, and had been so inspired by the local governance system that he kept it in mind while drafting the United States Constitution years later. Adams also wrote about the “Biscay” government in his treatise, “A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America,” stating, “While their neighbors have long since resigned all their pretensions into the hands of kings and priests, this extraordinary people have preserved their ancient language, genius, laws, government, and manners ... their love of liberty, and unconquerable aversion to a foreign servitude.”

The connection with Cundín’s homeland convinced him to look for artisans there for the engraving project. Pedro Aspiazu, who was born into a multi-generational family of engravers, hand-chiseled the plate, while a Basque company handmade the paper from pure cotton, and a Madrid company did the printing.

Cundín retained the same paper size as the original, but reduced the text size so there would be empty space—“a visual environment, to make it ... a document that everybody could receive in the mail, but in a magnificent size,” he said. The framed engraving resembles a painting, yet is humble in its quiet dignity. Cundín’s team made 1,200 copies— the first few were gifted to George H.W. Bush during his presidency, the king of Spain, and the United States Congress. Today, there are about 1,000 copies still available for purchase.

Independence Day

Paul Fattori hopes that younger generations can truly appreciate what this document means and the extent to which the signees risked their lives to publicly protest the British monarchy. “It symbolizes all that freedom, that liberty—and it’s about the people, ... consent of the people,” he said.

Sara Fattori hopes Americans neither take their freedoms for granted nor forget about the balance of powers in government. “I’m looking at a country like a family unit; like, if someone is too powerful and controlling, then the other people are not going to thrive ... and be able to flourish as a human being,” she said.

23 FEATURES

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT The brass plate etched with the Declaration; engraver Pedro Aspiazu; and artist José-María Cundín with the printed Declaration. Courtesy of José-María Cundín & Fattori Fine Frames

Fourth of July

The first $2 note...

was issued on June 25, 1776, making it nine days older than America. The Continental Congress authorized these “bills of credit” for the defense of America. Today’s version—launched on the United States Bicentennial in 1976, after a decade-long hiatus of the bill’s printing— depicts on the reverse an engraving of John Trumbull's "Declaration of Independence" (only 42 men appear in the $2 version, rather than the original painting’s 47).

Bristol, Rhode Island...

is home to the nation’s longest-running tradition of celebrating Independence Day—the city celebrated the very first anniversary in 1785 with the firing of 13 cannons in the morning and 13 guns in the evening—founded by Reverend Henry Wight, a veteran of the Revolutionary War. Festivities in Bristol each year typically kick off long before the Fourth, starting on Flag Day, June 14, with outdoor concerts and races, block parties, a vintage baseball game, a carnival, and a Fourth of July Ball, leading up to the main event—the Fourth of July Parade (officially the Military, Civic, and Firemen’s Parade). It’s no wonder the town calls itself “America’s most patriotic town.”

Cody, Wyoming...

holds its annual Cody Stampede celebration for the Fourth of July over several days as well, this year beginning on July 1 with the rodeo it’s known for, followed by concerts and parades, and culminating in fireworks at dusk on the Fourth.

Cody is 52 miles from Yellowstone National Park, and prides itself on capturing the spirit and heritage of the Wild West—after all, it was founded by Colonel William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in 1896.

FEATURES

LOCAL TRADITIONS

Chicago...

Gatlinburg, Tennessee...

has a full day of Independence Day celebration, beginning one minute after midnight with a parade, making it the “earliest” celebration in the nation each year. The day’s events include the Gatlinburg River Raft Regatta, where contestants enter one of two categories, either “Trash” (rafts not handmade) or “Treasure” (with handmade rafts)—anything goes, and you can even send a rubber ducky down the river. Festivities are capped off with a Fireworks Finale downtown. This mountain resort town lies right outside the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and for centuries saw Cherokee, European, and early American hunters and fur trappers along the hunting trail before officially becoming a town.

is not unique in putting on a fireworks show, but the city boasts miles of lakefront high-rise windows, rooftops, balconies, beaches, and boats from which to view the fireworks. Navy Pier is an attraction unto itself, jutting 3,040 feet into lake Michigan—the fireworks displays launched from it create stunning reflections upon the nighttime waters below. It also boasts an innovative and unique, $22.5-million, 196-foot-tall Ferris wheel featuring 42 climate-controlled gondolas. Navy Pier hosts fireworks shows on Wednesday and Saturday nights throughout the summer from Memorial Day through Labor Day, but they save the biggest and best for Independence Day.

—JUDITH M C CONNELL

Why fireworks?

The first Fourth of July anniversary celebrated was in 1777 in Philadelphia. Founding Father John Adams’s wish that Independence Day be celebrated with pomp and circumstance— “with shews, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other from this time forward, forevermore”—came to pass. He was referring to July 2, the date when delegates from 12 colonies voted for independence, but July 4 is when the Declaration of Independence was officially adopted, and what would become Independence Day.

FEATURES LOCAL TRADITIONS Public Domain, Bradley Olson/EyeEm/Getty

Henryk Sadura/Getty

David Hogan/Moment/Getty

NSA Digital Archive/iStock/Getty Images Plus, barbaraaaa/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Images,

Images,

Images,

For Family and Freedom

A 30-year-old Tiberiu Czentye risked his life to escape communist Romania, hoping to find a brighter future for his children. Decades later, with his grandchildren in mind, he’s telling his story and hoping it will help stem the tide of socialism

WRITTEN BY CATHERINE YANG / PHOTOGRAPHED BY CHANTELLE DOUCETTE

Parting from his wife and two sons was the hardest thing Tiberiu Czentye had ever done—harder than the upcoming 40-mile trek that would end with him crawling on the ground as he tried to evade armed guards near the Romanian–Yugoslavian border, harder than what would be months of hard labor in a Yugoslavian prison after he was captured anyway, and harder than the two years he would spend as either prisoner or refugee while crossing five countries before he finally won his freedom. “Family—that is why I left; I escaped Romania for the future of my kids,” Czentye said. “The biggest, toughest, most painful moment of my life was when I turned off the lights and kissed my kids and my wife goodbye, because I did not know if I would ever see them again.”

Even now, from the safety of his own home in a free country, when he speaks of it—when he remembers those goodbyes—he’s moved to tears. Czentye and his family lived in communist Romania, during the regime of Nicolae Ceausescu. From the beginning of this plan, he was clear about his goal: America. There, his family would have freedom and the opportunity for a better life and future for generations to come. “I studied. Many people leave and they don’t know what they’re doing or why,” he said. “If I make this sacrifice, at least I want to leave my family in one safe place for many generations. So I studied: the population of the US, the economy, the

states, the two parties, the political power, the military power, the power of the dollar and how strong is the economy, and all these things put together.”

America’s history as a country built by immigrants was crucial for Czentye. He was migrating for his sons’ futures, and he didn’t want to bring them all the way to a new country where they would be looked down upon—and that didn’t happen in America. “I bring them here for their futures, and to feel good, not to be hurt,” he said. “I had a very strong reason to risk my life.”

He knew he was risking his family’s future as well, but he had a strong feeling that he would make it— throughout his journey, he said he must have been blessed. Man alone can only do so much, he said, but perhaps God played a part too.

The Value of Human Dignity Circumstances were bleak under Communist Party rule in 1989 socialist Romania, when Czentye set out on his mission to escape: schools were brainwashing centers, hard work was penalized, and his sons’ futures were almost certainly shaping up to be worse than his own. But Romanians didn’t always equate socialism with dictatorship—many people in the world still don’t. First, came the promises of free stuff, allowing socialism to take hold, Czentye said.

However, once the Communist Party had power, it quickly became clear that it couldn’t keep its prom-

27 FEATURES

ises. Then, the regime closed the borders, morphed into a dictatorship, and its unrealistic goals ended up impoverishing the nation. “Under these restrictions and these political things, there started to be a shortage of food, shortage of gas—shortage of almost everything,” Czentye said. “People were dying.”

That hit too close to home when his younger son got sick and ended up severely dehydrated. At the hospital, Czentye learned of a treatment for the virus, three daily doses of which could help his son to recover. But the medicine was produced outside of Romanian borders, and the regime refused to buy foreign pharmaceuticals. Upset, Czentye checked his son out of the hospital, despite widespread accusations that he was sentencing his boy to death. Instead, he hired a nurse and purchased the medicine on the black market—and his son got better. His enterprising spirit was clearly at odds with socialist culture.

People in Romania had three options, he said: they could work hard and do their best while remaining unable to distinguish themselves or see the fruits of their labors, they could become lazy and collect the same pay as everyone else, or they could get out. The material side of things was only one concern.

Communist schooling, from kindergarten through college, focuses on brainwashing students while glorifying the Communist Party, Czentye explained. History is rewritten, all the media is state-run, private property disappears, and your movements are monitored and restricted. “Once they have power, they tell you what to do and how to do it,” he said. But there are always people like him, Czentye noted—people who want to make their own way and show their own worth.

In order for the regime to keep up its ruse, it doesn’t stop with lies and brainwashing. The secret police turn neighbors into informants, in a country where no one is allowed to criticize the party. “If somebody, just one neighbor, tells them, ‘Well, Tibi

said that ...’ in the morning they break down the door, take you from there, and you just disappear forever,” he said. That’s the worst part, he said: first, people turn on each other, society loses trust and faith in fellow humans, and people lose their dignity.

“People start to give you up. It starts to lose the quality and the value of the human being. I don’t want to say it because it’s not so fair, but they start to be more [like] animals, and just bend to the power.”

In contrast, family values were deeply ingrained for Czentye—growing up, he witnessed commitment between his grandparents and between his parents. As such, he didn’t just want a nicer life for himself: He wanted a future where his sons could flourish. Like his parents and grandparents had done before him, he wanted to lead by example and live out values worth imitating.

“That is why I left home, and left by myself. They have guns on the border and they used to shoot people—they don’t allow you to leave. I thought, ‘Please, they kill me, but they don’t kill my family,’” he said. From Czentye’s home in Timisoara, Romania, he crossed the border into Yugoslavia, where he was caught and sentenced to what amounted to slave labor, digging holes for electrical cables. After three months, he made his escape, traveling through Austria, through West Germany, and to the Netherlands, where he was placed in a refugee camp.

While in the Netherlands, Czentye sought political asylum in the United States and petitioned Romania to let his family visit him. The timing was fortunate—the regime had been overthrown and a new government was working to establish its legitimacy—and Czentye’s petition was granted. Being reunited with his family was unforgettable. He still remembers his trip to the airport, the suspense, and the first moment when he saw his family’s faces. With tears of joy streaming down his cheeks, Czentye was finally able to hug his loved ones again. It took a total of two years for Czentye to gain asy-

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 28 / ISSUE 2

PREVIOUS PAGE

Tiberiu Czentye and his wife Sandra at their home in South Carolina. Czentye is CEO of Allpro, a digital archiving company he built that stores and secures anything from family albums to confidential state files.

TOP LEFT & RIGHT

Czentye escaped socialist Romania so his family could live in freedom for generations; now he is continuing to fight for freedom for his grandchildren.

lum, and in 1991, he moved to the United States.

“I had two luggages, two kids, my wife, and God,” Czentye said. He landed in Portland, Maine, where his family was entitled to a year of government assistance. After three weeks, he turned it down, and the family packed up and hopped on a Greyhound headed across the country. They had their eyes set on San Francisco, a hub of opportunity and industry.

His Grandchildren’s Future

In San Francisco, Czentye worked three jobs at once, taking neither vacation nor sick leave for five full years before starting his own business. But things in California—and many parts of America— have changed since then, he said. From 2007 to 2009, Czentye would spend time traveling up and down the Southeast, looking for a new place for his family. He found it in South Carolina, and after his youngest son graduated from college— both sons studied in California, one at UCLA and the other at Menlo College—they made the move cross-country. Still, even after seeing changes firsthand in California, Czentye was appalled when socialism became a popular movement in the United States.

“I was shocked. Shocked! And very upset,” said Czentye, who today is CEO of a digital archiving company and a happy grandfather of five. “I really believe it is my duty to share my story and tell these crazy guys who like socialism that it’s not like that.” Inspired to do more, he got involved in local politics and was recently elected executive committeeman for his county, and is looking for more opportunities to share the truth still.

However, Czentye acknowledges that it’s not all these young people’s faults that they’re endorsing socialism; rather, their parents may have failed them by not teaching them to mind their character. The schools may have also failed them by pushing them toward expensive degrees in oversaturated

industries, racking up loans they now struggle to pay off. Even before Czentye set foot in America, he studied the culture, and from day one his wife and he were clear with their sons: Parents are the foremost teachers in life. Police and schoolteachers have roles to play as well, but those should never supersede parental guidance. He spoke openly about socialism, communism, what happened in Romania, and the follies of human nature.

Czentye and his wife wanted to give their boys good lives, and they made clear their expectations: that the boys should use the good manners they were taught and strive for excellence—and they did, doing well in school and sports. Their sons are now raising their own families with these same traditional values. But Czentye saw that many of his sons’ friends in grade school weren’t brought up this way; without good values, a person’s character can slip, laziness creeps in, and the mentality of blaming others provides an easy out. These resentful souls take readily to socialism and its promise of free things, he warned.

A second warning sign, a tactic reminiscent of what Czentye experienced in Romania, is the divisive culture attempting to take hold in America. “The socialists, they work very hard to divide us: to divide us by nationalities, to divide us by blue-collar workers [versus] white-collar workers, if you are a member of a political party—all of these things,” he said. But Czentye believes that truth will prevail, and if people can recognize socialism for what it is, America can stay free.

“I’ve had the chance to go [traveling] in many countries since I’m here, and since I had my company, I went back to Europe, I was in South America, I was in China, I was in Africa, [and] Japan. I can tell you, America is not perfect, but it is the best,” he said. “And from here, I’m not going to run anymore. I’m going to fight and do what I can against socialism and for a free society.”

29 HISTORY

Leading With Compassion, Strength, Courage, and Dignity

WRITTEN BY VANCE HAWK

Iam an American, and proud to be one. In an age when our history is under attack and our values called into question, I am here to say that the American way of life is valuable and worth defending.

I am willing to stake my life on that claim, and I am not alone. I work in the special operations community, and men in my line of work like to think of themselves as Spartans, but whenever someone says that, I reject it. We’re not Spartans, we’re Americans, and that is something to be proud of.

As a member of the United States Air Force, I have had the opportunity to serve alongside some of the finest airmen, soldiers, sailors, and Marines in our military. During my deployments to Afghanistan, I have grown to appreciate the history of this ancient and beautiful country. When I look across the Hindu Kush, I can see Alexander the Great’s army marching through the landscape, as well as the Persian Armies, Genghis Khan and his horsemen, Winston Churchill and the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and finally the United States. Though my experience is recent, there is a heavy history and memory here.

The men I work with have provided medical and rescue support for the U.S. Army. As such, I hear many stories of their heroism. I am proud to work with these men and see the sacrifices they make for one another.

One example is a man who recently risked his life under heavy fire from the enemy to defend and protect his brothers in arms. The enemy ambushed his team, firing shots down an alley, taking out three of his team members. He and one other man ran through a hail of bullets to their wounded teammates.

Getting ambushed immediately puts you on your heels; the enemy has the luxury of choosing the time and place. My friend was the underdog, but the love he felt for his fellow countrymen pushed him to risk his own life to save theirs. Bombs were impacting mere feet away, Afghan mud bricks being the only barrier against the explosions; get-

ting his fellow Americans medical treatment was his priority.

But they were trapped. With no way out except the way he came, he decided to reach out to his commander to coordinate their extraction. Once their position was pinpointed, the soldiers began blowing holes in walls of buildings until they created a path out to where the patients could be transferred to the legendary Army medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) helicopters.

Refusing to abandon his patients, my friend boarded the helicopter and administered treatment all the way back to their base. In spite of this man’s courage and skill, only one of the three men survived his injuries.

My friend’s perceived failure hung heavy around him, and he prepared for the rest of the team to add their own anger and disappointment to his shoulders. But he was mistaken. The other soldiers met him with gratitude; they had been surprised by his courage and could not believe his willingness to risk his life for them. The Scriptures say “Greater love has no man than this, that someone would lay down his life for his friends,” and I cannot think of a more dramatic example of what it means to be an American. While he mourns the loss of even one American life, the men he has saved honor him as a hero.

We are a country in crisis, but this is nothing new. We were, in many ways, born in crisis and war while believing in a better way of life. Great men have led us every step of the way, and there are great men alive today, making sacrifices and living as examples of why our way of life is worth defending, by leading with compassion, strength, courage, and dignity: the characteristics that set true Americans apart from the rest.

Americans are people who stand for what is right, and what is honorable. I have seen these men, and I have known them, and I have been lucky enough to call them my friends and colleagues. There is a legacy that we all look up to and do our best to emulate, that we should understand, respect, and continue to pay homage to.

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 30 / ISSUE 2 FEATURES WHY I LOVE AMERICA

We are a country in crisis, but this is nothing new. We were, in many ways, born in crisis and war while believing in a better way of life

The memorials to these great men are wrongly under attack, but their deeds and the lessons we learn from them live on within us. That cannot be taken away. In many ways, this is what it means to be an American—to live as they lived and to strive every day to be the very best that we can be. Many Americans may not be able to find Afghanistan on a map, but I surely know where to find the finest of Americans.

Vance Hawk serves in the U.S. Air Force as a combat rescue officer and lives in Yelm, Washington; his views are his own and do not reflect any official views of the USAF. Tessa Weber assisted Mr. Hawk with this article as his editor. She is an accountant in the Denver area who loves the outdoors and volunteering with the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation in her free time.

FEATURES WHY I LOVE AMERICA

BELOW Soldiers at twilight during a military mission in Turkey.

Guvendemir/E+/ Getty Images

Washington’s First Battle

The year is 1754—more than two decades before George Washington will become Commanderin-Chief of the Continental Army and more than three decades before he’ll serve as the first United States President—and the 22-year-old Washington has recently received his first military commission. The young Lt. Col. of Virginia’s colonial militia is preparing his troops to head into events that will spark the Seven Years’ War between the French and British. Reading the situation as best he can, Washington plans an ambush—while the French do the same. “It’s all about the land, and who’s going to get the land,” said Tammy Lane, who has

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 32 / ISSUE 2 FEATURES

PHOTOGRAPHED BY TAL ATZMON

embarked on a three-film project to tell the forgotten story of a young Washington who saw God’s hand in the course of his life. Here in this moment, Washington faces his first battle and has to defend himself. “He probably shot somebody. He probably killed somebody. I figure it would be impactful.”

Lane, head of Capernaum Studios, is currently directing the first volume of the “Washington’s Armor” trilogy, with an unflappable perseverance that some of her crew have likened to Washington’s own steadfast faith. “This is real history. It’s all true. It came straight from Washington’s journals and letters—and most people don’t even know about it,” Lane said. Artistic license is taken where there are gaps in the written record, but Lane took on the project with the intention of telling true history. It’s a portrait of a flawed, yet heroic, human being. “He wasn’t perfect. He made mistakes, as all human beings do. But he had a very high, high level of integrity and duty,” Lane said.

‟This is real history. It’s all true. It came straight from Washington’s journals and letters—and most people don’t even know about it.”

TAMMY LANE, PRESIDENT OF CAPERNAUM VILLAGE STUDIOS

FEATURES

LEFT Tammy Lane, president of Capernaum Village Studios, with Willie Mellina, who plays George Washington. Tammy Lane Studios

America Opposing Global Communism

At one time in the 20th century, more than 60 countries were ruled by communists. “The Free World,” led by the United States, took action to stop communism from spreading. Whether they succeeded or not, whether they were popular or not, several conflicts were fought by American soldiers, with the stated purpose of opposing communist rule and ideology, and the nation opposed communism in other ways as well.

Following are some highlights.

1918–1919 The Polar Bear Expedition

At the end of World War I, more than 5,000 American soldiers fought the communist Bolsheviks in Russia during the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. In this little-remembered conflict, some 235 Americans gave their lives.

ABOVE Polar bear memorial in Troy, Michigan. Bolandera/license

CC BY-SA 3.0

TOP RIGHT Medical corpsmen assist in helping wounded infantrymen after the fight for Hill 598 in Kumhwa, Korea, on Oct. 14, 1952. Sylvester/U.S. Army

MIDDLE RIGHT In Operation

"MacArthur,” soldiers assemble on top of Hill 742, near Dak To, South Vietnam, prior to moving out in November 1967. A purple smoke bomb is ignited in the background to guide in a helicopter. U.S. Army

BOTTOM RIGHT The fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989. GNU Free Documentation License

FEATURES

AMERICAN ESSENCE / 34 / ISSUE 2

1950–1953 Korean War

North Korea, backed by the USSR and China, attacked South Korea, which was supported by UN forces (mainly the United States). After some back and forth, Korea remains divided to this day. Out of the roughly 1.8 million Americans who served, about 54,000 gave their lives.

1955–1973 Vietnam War

Similar to the war in Korea, North Vietnam was backed by the USSR and China, while South Vietnam was backed by the United States and other non-communist countries. Unlike the more decisive Korean war, this war dragged on, and ultimately South Vietnam was absorbed into the communist north, while neighboring Laos and Cambodia also turned communist. About 2.7 million American soldiers served in this conflict, which lasted nearly two decades, and about 58,000 of them perished (of which about 1,600 are still listed as missing in action).

1947–1991 The Cold War

American “containment” policy was to stop the spread of communism and counter the USSR. Nuclear arms buildups on both sides made the prospect of a “hot war” unthinkable, so the two sides faced off in proxy wars, propaganda, the space race (essentially won by the United States when men walked on the moon in 1969), and other shows of prowess.

• 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

American leaders contended with the Soviets, resulting in the USSR removing nuclear missiles from Cuba.

• 1983 Invasion of Grenada

American soldiers landed in response to a formal appeal for help, and in the interest of protecting over 600 American nationals on the Caribbean island, leading to the overthrow of a Marxist regime.

• 1989 Berlin Wall Falls

The symbolic zenith of the falling of communist regimes in Europe was perhaps foreshadowed by President Reagan’s 1987 Berlin Wall Speech, in which he said, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” European nations ending communism at that time were Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Romania.

The Cold War effectively ended when the USSR formally dissolved on Dec. 26, 1991. By the early 90s, all other communist and Marxist regimes worldwide also dissolved, leaving only five communist countries in the world: Cuba, North Korea, Laos, Vietnam, and China.

35

History

‟Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong, as silly and as wise, as bad and as good. Let us therefore study the incidents in this as philosophy to learn wisdom from and none of them as wrongs to be avenged.”

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, STATESMAN

Founding Friends Bound Together by the Fourth of July

WRITTEN BY GEORGE WENTZ

The United States has been blessed with many distinguished leaders. But the generation that founded our nation has a special place in the hearts of many Americans. Even among that very special generation, two of our Founders stand out not only because of their many accomplishments and their lasting mark on the country, but because their friendship helped shape its early years—a friendship that both started and stopped on the Fourth of July.