University Road, Bristol, BS8 1SR

Bristol Grammar School, University Road, Bristol, BS8 1SR

Tel: +44 (0)117 933 9648

email: betweenfourjunctions@bgs.bristol.sch.uk

Editor: David Briggs

Assistant Editors: Francesca Moses and Olivia Alexander

Art Editor: Ed Hume-Smith

Design and Production: David Briggs and Ruth Bennett

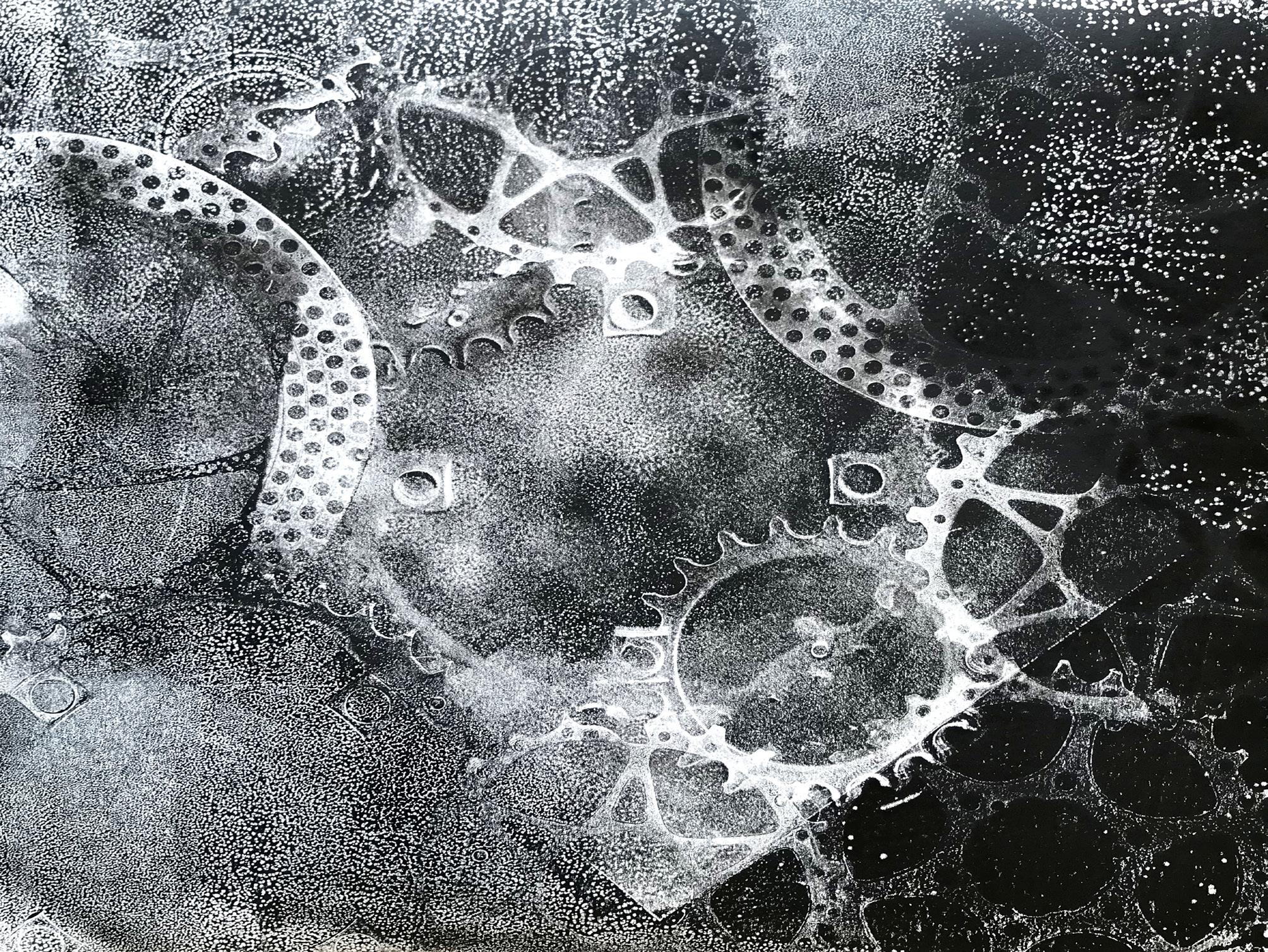

Cover artwork: Will Lindsay-Perez

© remains with the individual authors herein published January 2019

All rights reserved

BETWEEN FOUR JUNCTIONS is published twice yearly in association with the Creative Writing Department at Bristol Grammar School. We accept submissions by email attachment for poetry, prose fiction/ non-fiction, script, and visual arts from everyone in the BGS community: pupils, students, staff, support staff, parents, governors, OBs. Views expressed in BETWEEN FOUR JUNCTIONS are not necessarily those of Bristol Grammar School; those of individual contributors are not necessarily those of the editors. While careful consideration of readers’ sensibilities has been a part of the editorial process, there are as many sensibilities as there are readers, and it is not entirely possible to avoid the inclusion of material that some readers may find challenging. We hope you share our view that the arts provide a suitable space in which to meet and negotiate challenging language and ideas.

Writers’ Examination BoardTo be between four junctions is to be in a very specific geographical location in Bristol, a site haunted by pedagogues and pupils during the day, by dog-foxes and late-shift porters at night. A place marked by nearly a thousand desirelines each day as the worn soles of its temporary tenants are blown about by the motions of their brains, by the pitiless efficiency of clocks and watches, bells and timetables. And yet it’s also very clearly a place, like Derek Mahon’s disused shed in County Wexford, “where even now a thought might grow”. So here they are, thoughts that have sprung to life, taken shape and moved beyond the inchoate in this particular aggregation of time and place.

Fittingly enough, in this first issue, these thoughts have taken their final forms in any one of four media: poetry, prose-fiction, prose non-fiction, and the visual arts. So, to turn the pages of this magazine, to be immersed in its language and forms, is to be between four junctions in another way.

There’s a pleasing variety of work here, from across the school community. Teachers, support staff, pupils and students made submissions, and we were pleased to be able to make our selections from such a thoughtful and well-formed body of work.

It is noteworthy that the dominant subjects for poetry derived from concerns about climate change and the effects of war. Luke Dorman and Jooles Whitehead show a concern for the natural world in their visually precise poems, and Sophie Thomas brings a ludic poignancy to the same subject in her tour de force tribute ‘The Last Blue Whale’. Writers concerned with war include younger poets such as Charlie Groombridge and Naomi Parsons, but also Jasleen Singh, whose tribute ‘The Indian Soldier’ appears here in the wake of having been broadcast on national television as part of the Armistice Day centennial service. The psychology of servicemen and women also finds plangent expression in a forensic and striking short story by Arthur Hales.

Some aspects of the IB English couse are also beginning to find their way into the collective consciousness, and Asha Chatterjee’s splendid non-fiction piece ‘In Search of My Great-Grandfathers’ blends the historical and the personal with such skill it richly derserves its epigraphical nod to Edmund de Waal. Similarly vibrant and enjoyable work in creative non-fiction comes in the form of James Ormiston’s Transylvanian travelogue.

The prose fiction submissions showed writers from across the Senior School age range engaging imaginatively with the notoriously difficult short story form. We were pleased to be able to include brief but highly accomplished and fully-realised pieces from younger writers Theo Cameron and Lauren Dickie, and we were all dazzled by Rosa Thorne’s dystopian vision replete with the marvellously-named Foucher Illusocoins.

Returning to poetry, which was by far the most dominant form among the submissions, and therefore runs to two sections, this editor’s particular highlights include Taraneh Peryie’s Christopher Tower Prize winning ‘Richard’, Jennifer Benn’s calmly observed ‘Footage’, Can Pehlivanoglu’s fantastically ambitious Ovidian narrative ‘Sakura’, and Belnice Helena-Nzinga’s haunting and inventing poem ‘The Silences’.

This magazine also serves as a complement to At the Junctions, a new reading series at BGS featuring visiting writers from across the UK. During the 2018 Autumn term we were entertained by readings from poet and creative non-fiction writer Katy Evans-Bush, poet and Professor of English and Creative Writing, Andy Brown, and world-building prose fiction writer (and OB) Jeremy Levett. We also learned about issues concerning race and ethnicity in publishing from Heather Marks. Each writer delivers a thirty-minute set, followed by questions, during the extended lunch-hour. They follow this by chairing a workshop with the AFA Creative Writing students during the subsequent afternoon lesson. Visiting writers are also invited to submit to the magazine, and we are therefore pleased to be able to include Andy Brown’s elegiac evocation of the end of summer as well as Jeremy Levett’s archly-comic sci-fi vignette about the end of worlds.

This is a rich and diverse first issue, and it bodes well for the future of writing at BGS. We are grateful for all our contributors, and also for Ruth Bennett’s support with production and design, and Ed Hume-Smith, Head of Art at BGS, for selecting and photographing the visual art represented in the magazine, including the sourcing of our stunning cover image from Will Lindsay-Perez. Between Four Junctions will be a bi-annual magazine, and so the window for submissions for the second issue will re-open during the coming summer term, with a view to publication in September 2019. We hope you will be sufficiently moved, cajoled, and inspired by what you find here to pick up your pen/brush/camera/what you will, and contribute.

David Briggsa magazine for the written and visual arts

number 1

winter 2018/19

The neighbour carts his wheelie bin, the green one, this alternate Tuesday, out of the alley and into the street where herring gulls fanfare his ritual.

School kids laugh and traipse to class with feet in the shoes of their forebears. In the port the workmen swing their heaving loads of ballast to the dock,

where foetid fishing creels and lobster pots sit drying in the sun. Lost sailors’ ghosts evaporate into the air until the moon invites them through the halyards once again.

Down on the tideline, where plastic bottles, seaweed, wood and clumps of net wash up at paddling toddlers’ feet, an ancient couple set up station: tartan rug, a windbreak, flask of tea; the woman floral’d-up in polyester, her husband in his vest and handkerchief, though the pier is nothing but a memory.

Over the grind of waves and dredger’s engine out there at the mouth of the channel, a barrel organ spills unearthly echoes –except it doesn’t – beside the indifferent sea.

I used to think all men were slaves to me, but with the keen flick of your eye, faster than a serpent’s tongue, you swept through Jerusalem and called me to the foot of your bed. You smirk; some strong aphorism has played on your lips. Sweet, cool ablution; confessions to men in red; hermits fasting. All answer to you. The smooth lines of your neck, the arch of your back. I wake sweated over, filthy with want, full of threat and fallacy.

I want to scream, to sing about the whiteness of your throat, your cool nakedness. Ungodly red infection of the mind. Like the black-faced eremite on his pilgrimage from Edessa to the Holy Land, my feet will blister on stone.

You know me by an unspoken name. Like the hailing chorus of Gabriel’s wings, sounds that roll off your tongue, prickle against my skin. I’ll never see fire or hear the sea again. From fertile sin, out shall spring an apple tree, share its fruit with me. I will stand by you. King of England – dead, a sexless bedfellow.

I gave you my soul. I damned the sweet rivers of wine and the protection of the archangel’s wing – seized hell as my home. And you gave me your sister. A marriage of starched sheets. Her sweet eyes aping your own, a reflection so dear it made me weep. And is this how you’ll keep me? A dog on a chain? A mocking ghost of the memory I kept of you?

The faint likeness of blue irises? I will not ask. Two crowns cannot kiss.

I want to rip out your tongue with my teeth. I want to ask why your face is so calm, as if you don’t remember the embrace we shared, heat that passed between our bodies like ghosts. I could tear the hair from my head, watch it scatter like leaves, the hours burning on their own funeral pyre. If only God had reached down from Elysium and scorched my tongue to blistered snakeskin. You will forget, and history will never know, like water slipping through cracks in the sky into the ocean petrified into pillars of salt useless to a parched beggar’s throat. We will disappear, but even now I will collect each moment, each sound, each soft sighing whisper like precious stones. I will etch into rock Once, I loved the king of France and keep it as a pebble in my palm, quietly turning its smooth sides around in my hands.

Offish waters give their colour to you. The Seine. Now, we can say nothing at all.

I can hear the silences breaking through the night, gently whispering through cracks in the walls, as one greets another.

The room is dark but I can see them floating around each other, twirling through still air, quietly bouncing off the ceiling.

Their muted laughter echoes through the house. They glide delicately across the room. Some lie idly on the carpet, giggling childishly as the smell of alcohol dances on their breath.

Others sit perched on bookshelves, flicking quickly through pages with cigarette in hand.

Clouds of white vapour drift towards my face, travelling up my nostrils and stinging my eyes.

I cough violently, my lungs erupting from the smoke. I can feel their eyes on me now. They stare in shock, as if only just noticing my presence. Their glares are pure hatred.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper, and they all flee.

Purring people roll on their backs like social-climbing cats, waiting for you to tickle behind their ears, and behind their girlfriends’ backs, inject their immunity and their egos, whisper in their ear Aren’t you a good boy? And aren’t they? Throw them a treat, or maybe an introduction or two, scratch under their chins and scratch each others’ backs. Treat their fleas as you treat their pleas for assistance, de-worm their reputations and their arseholes, and feed them dry food that’s good for their teeth and gossip

that’s good for their teething problems because it sharpens their molars and their manipulative leverage, helps them catch birds and competitors alike in their claws and in their professional jaws. Stroke the backs of their necks

as they eat them alive and crush their spines, then watch as they lick the blood and the bitterness from their lips. Watch as they lap up the milk and the glory. After all, they truly are the cats who got the cream.

a moment’s meditation on a poem received

Words slip, flip, slide, ride; make their meaning; find their niche. Truth sits parallel; truth shits paradigms; truth slits wrists, gives life, bleeds truth, para-truth, parallel parapsychotic paralympics. Bladed truth, bladed-runner, finds a joint, rubs it ready, ready to light, to fire. Joint inhaled.

Hale! Hail! Heil!

Your health!

Hope for something better, a salvation wishing-well –tossing coins; throwing hope. Down she goes, dropping, falling, slipping, tripping on that dope, on that smoke inhaled. A truth absorbed. A truth diluted. An incarnational whim within. Heilsgeschichte!

My dear, the rise of the feminine is here. Paint cracked in streaks through gritty ink-blood. Fingers smeared across like war cries to the cosmos.

She will no longer be silent. She will no longer hide in fear, my dear.

A red face. The moon phases. The stars are smeared yet effulged through her eyes.

She will march to the beat of her own drum. She will protect and defend the womb of her nature.

The earth roots its leaves up her ankles, knees, trees; grips the hips. Soil ground in her bones, the force to give life in this life, for petals of yellow to bloom between rocks.

My dear, the rise of the feminine is awakened. She will stand with the world shouting “My body is my instrument!”

Lightning down her legs. She will remain unshaken.

The shivering greys of early autumn morning slide in rectangles to grow houses and flats, cool windows slipping through the icy air. Rivers of tarmac seeping through the city. The sludge of cement between bricks. The pavement slots together beneath my feet – the adult’s jigsaw; rough grain, coarse and harsh; the soles of my feet unprotected, unhindered, uninhibited.

a blade of grass slicing through the squares. A stroke of emerald on a clean slate, crushed between concrete, suffocated by asphalt, tormented by darkness, bound in chains of roads –agony in the abyss of enclosure, foundations raking at my flesh, the crust of cities drowning me. My forest! The shaved head of a prisoner, captive of my own child.

Unlike the whooper swans, our arrival under the waning light of an autumn moon was stealthy. Glassy lochs wavered midnight blue and surreal signs - ‘Feral Goats’ - and fragile deer encaged in red triangles punctuated our route. Morning brought vistas enshrouded in seal grey, tantalising shifts of predatory clouds revealed their prize. Only to withdraw the promise.

The sea, the only constant the mist can’t veil, unveiling the nuances of current and reflecting the winds. You too have your autumn colours of cormorant black, heron grey. Whiskey water rivers race across the landscape, feeding the peat from the stones’ muzzle. Trailing tails of spume lighten the umber until the canvas is painted, the view revealed –a raw impression of Skye.

Prehistoric forms, no vulnerable manatees here. These swim across the Sound of Sleat, their lives in their hooves, gauging the vagaries of currents, bovine breaststroke as opposed to doggy paddle. The sea, a patchwork of hairy russet seaweed, fills with cowkelp ribboning across briny water, umber braids of pasta,

and horns like fishbones at the prow.

Tides misjudged would see them swept out to sea, pickled in salt, found many years hence, a confusion for naturalists. Truly primordial. Seasalt herbivores speeding their way over the sea to Skye.

“Out of the belly of Sheol I cried, And You heard my voice.”

The last blue whale is swimming in the thin stud wall of your hotel room. On the phone to a loved one, you pick at the label on the wall that tells you the whale’s name, its taxonomic classification, its date of approximate birth –

the last blue whale moves like Judy Garland in slow motion caught in the thin ridges of holographic plastic and its song echoes up towards you, between joists, booming emerging out of the wall somewhere behind a shelf in the corner on which someone has placed a stack of neatly folded towels and an aloe vera plant.

The last blue whale swims closer until its dark and lidded eye fills the space between the sofa and the door to the en-suite and (returning the phone to its receiver) you walk up to the wall, push the sofa to one side and stand inside the eye of the last blue whale – run the thin edge of your fingernail along the peak and valley, crest and trough of the blue-black

(bible-black)

hydrocarbonated sea.

As you move your head from left to right, your eye catches first one side then the other of each holographic ridge, inviting the eyelid of the last blue whale to (open) – close – (open) –close – (open)

you are locked into a staring contest with the last blue whale and, keeping your head perfectly still, you place your outstretched hand against the wall (the whale’s grey and solemn face fills the wall and the water is dark and cold). You curl your toes into the pile of the hotel room carpet, feel its synthetic fibres against the thin skin of your foot’s arch.

The voice of the last blue whale lifts and breaches like a crack in the celluloid of an old film and you are reminded suddenly of Celia Johnson’s face at the end of Brief Encounter. Those eyes. The leaves of the aloe vera shudder a little

but the last blue whale is bored of you and your daydream about Celia Johnson and it blinks once, twice

please, use my handkerchief

pin-pricked light tying you in ribbons of wavy murk into which you (frail skin-boat) sink.

I walk down the road from the Salt Lake house past the Punjab National Bank, dismissing the rickshaw-wallas who persistently tout for business on the corner of Broadway. I wait at the GD bus stop with two women planning their shopping trip at New Market, bags on shoulders, ready for action. The VS14A arrives and I get on it, quickly re-occupying a seat that has just been vacated by someone leaving at my stop.

On the thirty-minute drive I am subjected to an assault of all my senses: the constant honking of battered, yellow taxis; the jolts from relentless braking and sudden swerving throwing me into seemingly unperturbed fellow passengers; tiny women in dusty saris carrying unfeasibly large and heavily-laden fruit baskets at the roadside.

When the bus reaches the Esplanade terminus I board an electric tram towards Bagbazar, knowing that this line has operated for over a century but suspecting that the trams probably have a little more glass, angles and pace now. We pass the Writers Building with its Greco-Roman features, striking white pillars against red brick. As we travel through BBD Bagh Square I am returned to an earlier time, when this place was known as Dalhousie Square. It was renamed to celebrate three young fighters for Indian independence who assassinated a notoriously cruel and oppressive Inspector General of Police in 1930.

We hastily depart from the architectural legacies of the British Raj but not before passing the high-domed roof and Ionic-Corinthian pillars of the General Post Office. The next landmark, the Mughal-influenced Nakhoda Mosque, is equally impressive. As we head into a part of the city characterised by its smaller temples, public buildings and residential blocks, the tram gets busier.

Soon I’m riding down College Street, nearing the beginning of the story. As I gaze out of the window, I transport myself back to the last years of British rule in India. The streets are almost as busy, but instead of suited businessmen, tee-shirted tourists and women in kaleidoscopic saris crowding the pavements, men clad in white dhotis try and over-take each other by side-stepping on to the tramtracks with little regard for their personal safety. Students are late for lectures, cycling erratically to avoid stray dogs and begging children.

Back in the 1940s, my father’s grandfather would have been giving those lectures. As a Professor of Philosophy in the Government’s education service, Charusasi Chatterjee moved between colleges, but spent much of the latter part of his career at Presidency College, which is now clearly visible from

the tram. This college, where my grandfather would later study engineering, was founded in 1817 by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, a revered Bengali Hindu reformist who died a long way from home, in Stapleton, Bristol, where I previously went to school. This further deepens my sense of connection to this place. I disembark from the tram to become a part of the crowd.

I cross the street and walk to the entrance of the college. I enter unchallenged, despite not moving with the same sense of purpose as the students nor dressing like them. I step out of the throng into a shaded colonnade bordered on one side by clean white, horizontally-ridged columns, and on the other by a wall with a series of tall, slatted wooden doors. I pause by one door to look at a noticeboard. This is where Charusasi would have published the exam results of his students, where they would have crowded round in anticipatory excitement.

After breathing his air for a while, I return to the entrance and head back onto College Street. What would he have done at lunch time, when he needed some space to regenerate after a challenging tutorial? I look around.

In this part of the city the stalls that line the roads are now predominantly occupied by secondhand booksellers, but they were more varied in the 1940s. There were more streetfood vendors feeding the locals and the influx of American and British troops with any number of deep-fried, golden snacks – singaras (known outside of Bengal as samosas), pakoras and kochuri.

As I think about men in uniform arriving in rickshaws, laughing and eating together in those moments away from the atrocities of war, my mind shifts and I look up into another part of my family tree. I wonder if my mother’s grandfather, Corporal Thomas Chellew, came here in search of food and distraction when, in the summers of 1942 and 1943, 607 Squadron was stationed not six miles away at Alipore airfield. He may have seen this part of the city from the sky, given the RAF’s role defending Howrah Bridge from Japanese Mitsubishi Ki-21 bombers just two miles east.

I had come here in search of one great grandfather, but found two. And before I know it, I am entertaining the possibility that they may have met, that their paths had crossed here over fifty years before their lines became entwined with the meeting of my parents on a different continent. What had started as a casual stroll into the previous century suddenly feels more urgent and compelling. I become aware that I might appear agitated, like I’m looking for someone I’ve lost in the crowds. My pulse is certainly raised, but only in excitement at the prospect of tuning in to their conversation. My eyes alight on a street sign for a side road off College Street. Bankim Chatterjee Street. That’s my grandfather’s name. My connection with this place deepens further and Bankim Chatterjee Street becomes my true north, the magnetic field around it drawing me in. At its epicentre is a coffee house. The Indian Coffee House has two large signs compensating for a small entrance below them nestled between two book stalls.

It transpires that it was established in 1942 and immediately became the “go to” place for staff and students of Presidency College. It was an adda – the Bengali word for a renowned meeting place where intellectuals debated the issues of the day and cultural history was made. Exactly the sort of

place a Professor of Philosophy might go. But also the sort of place that welcomed a diversity of viewpoints and backgrounds, unlike the Indian Nationalist-only eateries of the time, which would have been far less welcoming to a British airman.

I take a deep breath, inhaling Charusasi’s persona, and enter. The Coffee House opens up into a wide hall full of small square tables, most of them occupied. The walls carry down-lit pictures of Bengali icons and cultural scenes. At one end two windows open out onto a small backstreet, allowing natural light to blend with the white haze around closed cubic lightshades. The shades hang from horizontal metal pipes that run across the hall, and also hold slowly-rotating ceiling fans. I look up and see that there are more seats upstairs on a balcony area that looks over the main atrium.

The spirit of debate is clearly alive, as the background noise drowns out my request for a table. A bespectacled waiter in a white uniform and turban, both with black sashes, leads me to a table for two in the corner nearest one of the windows, and I sit in a dark wood chair, with a woven wicker back, facing into the hall. The waiter takes my order and conveys it to a busy accounts desk and from there to the kitchen. Minutes later I have a black Darjeeling chai, a bowl of ghugni and a plate of parathas in front of me, all reassuringly steaming. As I close my eyes and wait for them to cool, I allow my imagination to cast back to 1942.

“Do you mind if I join you?” A nearby English accent penetrates the background Bengali murmur. Charusasi looks up over his reading glasses to see a man, probably in his early thirties, dressed in sharp-seamed khaki shorts, with shirt cuffs neatly folded above the elbow and a beret in his hands. He closes his book, pushes it to one side of the table and smiles as he gestures invitingly towards the chair opposite.

If there’s one thing I haven’t done much of in my life, it’s travelling abroad. I can count on one hand the number of countries I’ve been to outside of the UK, and two of those (Switzerland and Germany) don’t count as I saw little more than their airports whilst waiting to go elsewhere. This leaves three countries I can say I have visited properly. France (for a wedding), Sardinia (for a music festival), and Romania. France and Sardinia were wonderful; whether I was wandering the streets of Paris, admiring the majesty of Mont Blanc from the edge of Lake Annecy, or dancing to drum & bass on a sunny beach in San Teodoro. But my time in Romania was special for an entirely different reason.

I was there ‘on business’. Those who know me are probably aware of my background in palaeontology, which I studied at the university over the road for four years. We had many opportunities to work in the field during this time, but these were always UK-based (Arran, the Peak District, the Isle of Wight and so on). When one imagines a palaeontologist digging up fossils, it’s usually in a scene of remote badlands somewhere in Midwestern America. As geologically varied and fascinating as our nation undoubtedly is, the allure of fossil hunting abroad is hard to resist when given the opportunity. In my case, I was able to join an expedition to Hunedoara County in Western Romania. I remember almost jumping in my seat upon receiving the email advertising the trip.

Although maybe not the best known country for fossils, Romania has a rich and intriguing palaeontological history. When discussing this history there is one name that pops up over and over again. That name is Baron Franz Nopcsa. Nopcsa (born in 1877) was a palaeontologist, adventurer, soldier, spy, and at one point had his eye on the throne of Albania after helping win its independence from the Turks by smuggling weapons. His story is an extraordinary one, and his contributions to the study of fossils were in large part thanks to his prolific writing, innovative theories, lavish illustrations and immense collection of specimens. Shortly before his death aged 55, growing debts forced him to sell this collection to London’s Natural History Museum.

The dinosaurs he studied were unusual. In the area surrounding the city of Hațeg, the Carpathian Basin, he named a number of new species which were much smaller than expected. The rocks of this area indicate that during the Cretaceous period it was a large island in the (long extinct) Tethys Sea, and it was suggested that living on an island caused the dinosaurs there to evolve to smaller sizes. This is now called the “island rule”, which states that the sizes of animals change depending on the resources available. But Hațeg Island wasn’t just home to tiny dinosaurs, it was also a place ruled by some of the largest pterosaurs to ever exist. Pterosaurs, flying reptiles like the famous Pteranodon (the term

“Pterodactyl” is a misnomer), had wingspans of up to six or seven metres. These were large animals, but one group of them (called the azhdarchids) were so large that scientists are still trying to figure out how they got off the ground with wingspans exceeding ten metres. Hatzegopteryx thambema was one of these giants, and it lived alongside the dwarf dinosaurs of Cretaceous Transylvania, perhaps even preying on them.

So, for someone studying palaeontology, a trip to Transylvania is much more than a chance to see some spooky castles. Not only did the rocks of Hațeg chronicle one of the most interesting ecosystems ever discovered, but they also recorded the dinosaurs’ demise. A number of locations in the area straddle the boundary between the Cretaceous and the Paleogene, marked with an invisible signpost in the form of high amounts of iridium. Iridium is seldom found on Earth, it mostly comes from space rocks. This layer records the moment the dinosaurs were wiped out by a cosmic impactor so large that when one end of it contacted the ocean, the other was still at the altitude at which most airliners fly.

I arrived in the historic city of Cluj Napoca at about 2am after flying via Munich from London Heathrow (hence Germany doesn’t count). After leaving the airport we approached the nearest taxi and, completely failing to correctly say the Romanian for “Can you take us here please,” showed the driver the address of our hostel. He replied simply with “No problem” and loaded us up. What followed was a 65mph rollercoaster through the mostly empty streets with loud rock music playing on the radio and a phone in each of the driver’s hands; one with the GPS, and one for arguing with someone back at the garage.

After some much-needed sleep and an early start we set off on the long journey to our field site, where we would spend the next week or so. Cluj Napoca had a strange juxtaposition that became apparent as we left it in daylight. On one hand were the grand old buildings and churches representing a vibrant cultural history, but here and there were also monuments to the Iron Curtain in the form of imposing, grey, utilitarian blocks of flats. Both were soon behind us as we snaked through the rolling hills and rural towns on the way to Hațeg. Romania is a bit like Italy in that it is often very hot in the summer, there is an abundance of orange-roofed houses, and the language shares some similarities too. Two differences are that you’re more likely to be eating a soup of some kind than a pizza, and there are Dacia cars all over the roads.

Digging up fossil bones is somewhat romanticised by Hollywood. If you’ve seen the first Jurassic Park film you probably remember seeing Dr. Grant and his team nonchalantly whisking sand off a complete raptor skeleton, as if they’re uncovering a lost toy in an attic. In reality it can be extremely difficult and time-consuming work, even without taking the outdoor conditions into account. I have friends who have been to Svalbard to dig up marine reptiles and had tents snowed under, toilets blown over, the occasional polar bear encounter, and so on. But the rewards for this toil can be great indeed, and we knew there were some amazing things to be found, so we jumped into our walking boots immediately and got to work.

The first step is to just walk around and look. Once you are familiar with the local geology you will start to recognise when something looks a little different. The late Cretaceous deposits around Hațeg are often a bright brown-orange or a blue-grey, with the bones inside preserved in white or brown. Combine that with the bones’ distinctly organic form and a good eye will find them with ease. Once a bone has been spotted the general approach is to assume there are more around it, so you carefully hammer chisels in a rough circle around the bone to lever a chunk out.You can then wrap it up in plaster or tissue to take back for preparation. This usually involves breaking the rock into smaller bits and isolating any other bones within for bagging up and sending to a museum collection. Sadly I cannot describe what we actually found due to research regulations.

Remember that I said it was hot? Very hot! About 35 Celsius – dry, continental heat, while smashing rocks open for hours on end. Some of our time was spent doing this in water, and the temptation to go for a swim to cool off was strong. At first we resisted the urge, as we had seen the rivers were home to lampreys and enormous leeches which occasionally had a go at nipping our wellies. But after a while we found a more isolated, empty, slow-moving section of river and were instantly refreshed by a dip in the cool pool.

Although we were there primarily for our expedition, we had time to visit some of the non-geological attractions the area has to offer. First we went to Corvin Castle in Hunedoara. The castle dates back to the fifteenth century and comes with battlements, a moat, a dungeon full of gruesome torture devices – the whole shebang. The theme of vampires comes up a lot at tourist centres in Transylvania, and Corvin Castle’s surrounding gift shops were no exception. Although urban myths claiming the castle partly inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula are just that, the castle did host Vlad the Impaler when he was imprisoned by Hungarian military leader John Hunyadi. It has also been used as a film set a number of times, including for the recent horror flick The Nun. But Romania’s history stretches much further back than this.

Peppered around the countryside are the scattered remains of settlements built as part of the Dacia Province of the Roman Empire. Two sites were on our to-visit list: the first and second capital cities of Dacia. Built in the second century and eventually destroyed by the Goths, the metropolis Ulpia Traiana preserves many building foundations and fragmented examples of beautiful Roman architecture. An amphitheatre, gladiator school and many temples are found at the site. A long, winding drive of 40 kilometres through the steep Carpathians brought us to the original capital of Dacia, before it was taken over by the Romans, Sarmizegetusa Regia. A mysterious concentric ring arrangement of rectangular pillars accompanies the many temples built at the site, along with what some believe to be a type of sundial (possibly inspired by the Greeks).

This latter visit also exposed us to a more natural spectacle of the region: thunderstorms.Thunderstorms in Transylvania are small, fast and dense. We had only just arrived at the site and got out of our car when we heard the thunder rolling in through the tall trees. We were making our way through the forest to the ancient site when lightning struck the ground close enough for us to see the

exact spot it made contact with. We were in a forest on top of a mountain, 1200 metres up –not the best place to be when lightning is around. So we hightailed it back to the cars, creating a scene not unlike the climax of Jurassic Park when the T. rex escapes from its enclosure. Instead of a giant reptile roaring behind the streaming car windows, a lightning bolt threw itself down a radio mast about 20 metres away. Perhaps the Dacian gods had decided we should leave.

Later we visited the mining town of Petroșani, home to a wonderfully curated mining museum, which we were given an extensive and enthusiastic tour of (in Romanian, though our native colleagues translated for us). We also took a diversion to a cave called Pestera Bolii (‘The Cave of Disease’), which contains cave paintings and a wide subterranean stream – a welcome refuge from the punishing outdoor heat.

Until then we had been preoccupied with animals which had been extinct for millions of years, but on the outskirts of Hațeg we visited some animals which had been extinct for much fewer. Down a long meandering forest road, coming off the National Route 66, is a house. You pay six Romanian lei (about £1.15) and walk down a trackway to a clearing. At the end of the clearing is a gated field containing a herd of huge brown animals not seen in Romania since 1852. Bison look fittingly ancient with their fuzzy pelts, curved horns and hulking shoulders, as if they have walked straight out of a thawing glacier. It certainly served as a suitable bookend to my time in the country.

The process is not, in truth, all that complicated. The rock is surveyed, its mass and density ascertained. Stays are drilled into its core and motors attached; sometimes, an abort mechanism is added, though usually not. The most sophisticated aspect is navigation. The calculations are logical enough, but the raw data must be perfect. Once the course has been determined and the relative positions of the rock and the target ascertained – once the planets have aligned, if you will - the motors fire, and the rock accelerates. It passes for a time through the depthless vacuum; once its fuel has burnt away, it is acted on only by the gravitic tug of distant stars and the faint drift of the galaxy a-whirl all about it. Then, if the aiming solution is good, it makes contact with the target and, through a brief but intense series of interactions that can be explained to you by any schoolboy caught doodling explosions in his Physics class, introduces that target to all the pent-up hate and frustration of the rock’s engineers.

I can see the rock now, through the Blantyre’s one real window. I’ve been seeing images of it almost constantly for a year, from mission-briefing models six months and three systems away to crass, blurred “action footage” from a few hours ago as the Longstreet’s gunners shot off the booster engines at unnecessarily close range. As it lies before me now it’s a tiny glint, only visible by the reflected sunlight. But say what you like, there’s something special about seeing things with your own eyes.

Starbreakers, Inc., say the patches on my suit and the livery on the hull of the Blantyre. It’s an ugly, stupid name thought up by people who believe in brand management, men and women in suits I’m glad I’ll never meet. We are not the biggest or the oldest of the rock-stopping operations around – both of those titles are for Spiros & Harker – but our oh-so-understated ads, placed in the pages of people who pray they’ll never need us, say we’re the best. Response times matter in this business, and we’re faster than S&H; less institutional inertia, less of the stultifying regulation that comes from trying to standardise something too big over too wide a space. S&H have fossilised as a corporation; we might overtake them in a few years, and have our own turn at the top of the slippery pole, underdogs snapping at our vulnerable nethers. The only other serious contender on the interstellar stage are Weltabwehr, who kicked off fif-

teen years ago and are so good it’s downright scary, but they fouled up the Leo job – admittedly through no fault of their own. The bets are still open as to whether the company’s rep died in that impact, but four million people certainly did, and counting.

So: here we are, a few hundred kilometres from this nameless lump of inertial murder, and coming in quick, with very large quantities of currency and, potentially, human life, at stake.

“It’s a military op,” I remember saying with some surprise to Artem, two months ago, when the Blantyre set off from the company station above New Ambleside.

“Well, of course it is,” he said. Then, with some suspicion, “Do you make a habit of clocking on without even looking at the mission?”

“I looked at the fee. Easy decision to make after that.”

Of course, I was breaking the company line by even calling it a military op; we are meant to be neutral here, acting only as civilian contractors, Apolitical Averters of Impact Events. But you can work most of the situation out from context; people don’t pay Starbreakers’ fee unless their existence is at stake, and people don’t weaponise asteroids unless they wish their fellow man considerable discomfort. There are at least two players involved beside us: one of them has attached the drivers to set this rock on its way, and the other, who presumably lives on the planet in the way, objects to being annihilated by a giant inertial kill vehicle, and is willing to pay a staggering amount of money to avoid this happening.

You can draw further conclusions – that these are two rather undeveloped players, nascent colonies without spaceflight and possibly without even serious industry, from inferring that the victim nation doesn’t have the launch capacity to attempt an intercept themselves and the aggressor can’t afford anything more subtle or sophisticated than a pebble from God’s own sling – but here you enter the realms of speculation.

As this is a contentious mission rather than a random rock, we’ve got some shooters to look after us; a warship named the Longstreet, run by an outfit called Brisk Security, which will be shadowing the Blantyre for the duration. I personally haven’t heard a single good thing about their character; the one who was constantly trying to chat me up over the link for the last six weeks was certainly no paragon. But rep matters, even out here at the ends of the stars. And their rep for competent violence is solid as a million tonnes of craggy nickel-iron.

Speaking of which. The rock ahead doesn’t have a name; optics have picked up PANDAEMONIUM scrawled on some of the engine housings, but nobody wants to write that in a report. We just call it ‘the rock’, which goes to show they really don’t pay us for creativity.

I’ve been on two rock-stopping jobs for Starbreakers before, the first of which paid off my training, the second of which gave me savings enough to live comfortably for the rest of my days. Neither was contentious; there are plenty of pieces of stellar debris threatening to rub out underdeveloped colonies, and plenty of governments who will pay us to avoid that. But there are only so many people insane enough to attempt to weaponise an asteroid. Rocks flung at planets are objectively bad weapons.They’re extremely difficult to shoot down, but they cost more than a ballistic missile programme, and if the calculations are even slightly off they miss entirely or, worse, flatten the wrong continent. Even when they work perfectly, they cause the sort of collateral damage that makes them a crime against good business practice.

Like everything, it comes down to money. Doing anything in the void costs. Motors are cheap and ubiquitous enough in space terms, and rocks are a budget option compared to genuine spaceborne weapons, but cheap in space terms is still ruinous, and the budget in question is that of a well-off planet. And as a countermeasure, the cost of a Starbreakers callout... well, we’re the best, and we charge accordingly. You get what you pay for; you pay for what you get.

I’ve done my reading: there have only been twenty-one contentious rock-stopping runs in all of human history. Spiros & Harker have done six, one of which saw two of their teams killed and a warship dragooned in at the eleventh hour; a considerable expense in both blood and treasure. Starbreakers have done one, which went off without a hitch.

I don’t know what was in the minds of the people who planned this particular rock. They may even be mad enough to believe it will actually hit. But it will be a year before the rock hits, long enough for the suits to try again and again. A second mission would turn profit to loss, a third would put the entire company in financial jeopardy; but their rep rests on it, and that is worth everything.

Compared to all those trillions, the expense of a few sophisticated booby-traps and deterrents is negligible, and we have no doubt the rock is riddled with them. I’m fighting the craftsmen who worked this rock, not the planners or the paymasters. If they are better at their jobs than me, I’ll never be close enough to my killers to even see them. It’s oddly difficult to take personally.

“Belt up,” says Artem, terse as he always is, and we go below to prepare.

We are pawns in the most detached method of fighting ever devised. This is war without slaughter, war without hate; war reduced to a puzzle, played down a one-way wire five years old and fifty billion kilometres long. The only person really likely to die is me.

The band starts to play: the guitar first, a few striking reverberating notes out into the breathing, thrashing throng of people. The focus on the player’s face is intense but the enthusiastic energy infectious too. The lead singer strides one high-heeled boot towards you with a click and firmly wraps a hand around the mic. Her other hand is fiercely holding a simple power chord on a white and gold Gibson guitar, which hangs in line with her leather miniskirt. Her voice is a soft screeching, pure power in few words. The drummer never misses a beat. The guitars ring out perfectly timed; the bass growls, every syllable the lifeline of the song. The connection between them all is obvious and for a moment you too feel like one of them. ‘This one’s for you Chicago,’ she shouts. Her lipstick is a rich purple which glows in the warm night.

The riff is still resounding inside your head when the picture fades away. There is a living, breathing moment of silence and complete blackness. The machine whirrs, once, twice, thrice. ‘Thank you for choosing Dreamify.’

A man of unknown age stands at the front of the hall, sharply dressed in a timeless, three-piece black suit that complements his cautiously practical watch. An oval badge reads ‘Mr Foucher’, and underneath, in a smaller uppercase font, ‘HEAD OF DREAMIFY™ CORP’ is clipped onto his jacket.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, today I am here to revolutionize technology once and for all. A statement which, I assure you, you will not consider too bold once you see the technological marvel that is my greatest achievement …

‘Unfortunately, you have run out of Foucher Illusocoins™ for the night.’

His largely black moustache quivers when he talks, intertwined with the same paler, greying hair strands which find their way on top of his head. You don’t know if it’s deliberate, a fashion statement to match the suit, or the first sign of his age creeping into his appearance, but in this lighting the latter feels more likely. He stops talking momentarily.

The auditorium lights dim and a screen drops, displaying a series of grainy black-andwhite photos featuring glamorous people smiling, celebrating, living seemingly perfect lives. The grey hairs seem more deliberate against this backdrop.

‘Welcome back 150 years to glamorous 1930s Hollywood, amid the beginning of cinema, the start and inspiration of technology as we know it. A world where streets are soaked with neon and shivering silk, laced with gold threads, and held together with reels of video tape. It is my very greatest pleasure, after lifetimes of research, to finally present you with the opportunity to meet the stars who defined that world, despite their early deaths.’

‘As per Government Article 3.4 Clause 6 [Priority: Alpha] you must continue to sleep for a minimum of 8 hours, or 5 dreams.’

Mr Foucher laughs. ‘However, this is not what I have spent years perfecting. For, as great an era as that may be, there is so much more of existence to explore. I’m sure you’ve all seen VR, its rise, its fall. And even from the brief, several of you dismissed this as an ill-fated, pointless revival. That is not what this is. This is saving you from yourselves, making every second count, giving you the chance to experience everything, take over the world, save it, rebuild it, outlive it and not only meet your idols but be them as well. And all before your 7 o’clock morning alarm. I am proposing a world where dreams are purely synthetic and all the more beautiful for it.’

‘As you know, quality of subconscious and conscious living are strongly correlated, and so for one night and one night only we would like to offer you a premium subscription for only 80% of the original price. Happy Black Friday.’

‘Not only does this present great possibilities for enhancing the quality of life for every individual, it creates jobs, it creates business, it creates potential. More than all this, it does not just create the future, it is the future. We can now prevent crimes before they occur, end discrimination through subconscious conditioning. Everyone benefits.’ He pauses momentarily, smugly. ‘I challenge any one of you here to name a person whose life is not infinitely improved by my worthy invention’

You want to accept it. You dream of the past sliding into the slot, throwing aside dust, letting you breathe freely. Knowing you can escape. That a few hours are completely and utterly yours. Dopamine, oxytocin and serotonin, pure and simple. C8H11NO2, C43H66N12O12S2 and C10H12N2O. If it were reduced even slightly more you could, you would. But you don’t have the interesting well-paid job of a premium pass holder, and the machine not only knows it, it controls it. The offer fades away.’

‘Sleek, efficient, environmentally beneficial, rigorously and robotically effective based on micro-tech, precise to a subatomic level, perfectly and immaculately designed and programmed to ensure it is indistinguishable from real life. Night after night, a glorious nostalgic journey through the highlights of humanity, handpicked by our editors. Nightmares, sleep disorders all will be cured forever more. This is the future. More than that, this is your future, our future.’ He finishes his speech with a hungry smile, eyes still glinting with passion at the thought of his hobby and obsession, scanning the applauding crowd of businessmen, scientists and cameramen in front of you. A slightly queasy-looking stockbroker scratches something on a thin, grey paper notebook and you hear his neighbour tut and mutter something at him. The applause continues, unknowingly, rigorously robotic.

*

We are disappointed to see you have not decided to increase your dream count.You still have

six hours of sleep remaining.

There is a living, breathing moment of silence and complete blackness. The machine whirrs, once, twice. ‘Your next nightmare will begin in 5…4…3...2...1 *

You sigh and raise your hand, slowly getting to your feet. Squeaky and indignant your voice shakes as you query his words. ‘Indistinguishable from real life? How will we know what’s real? Surely that’s incredibly dangerous? And besides, it’s completely impossible – you won’t have that technology out in either of our lifetimes…’ *

The auditorium blooms into existence in front of you, like a darkly saturated paintbrush dipped into a pot of icy water.

Mr Foucher’s voice rings out, echoing inside your skull. ‘My dear, how do you know I haven’t already succeeded.

William Harris was walking with his squadron back to camp. He’d been walking like this for hours, either as point man, or in the middle of the line of eight men. One of his unit, Scott, suddenly crouched and held up a fist – all the men dropped low and brought up their assault rifles.The click of safety catches being flicked off cut through the heavy, oppressive silence.Then he spotted the target: a man walking along the wide open field. Just another farmer. They brought their firearms down and stood up. A crack filled the air. Scott dropped, like a rag doll who’d suddenly outlasted its interest. He lay with blood pooling in his helmet. William stared desperately through his scope, willing the sniper to magically appear. Another crack, and he saw movement to his right. The shooter had been identified and taken out. They all slowly got up and, with Scott’s limp corpse being held between two men, continued their way back.

He sees his father peering through the iron sight of his old hunting rifle. Old, but no less lethal. The stock was varnished and polished wood, the metal cleaned and oiled. He also sees what is standing unaware, at the end of the barrel. A tall deer, gently munching away at the thick luscious grass beneath its feet. But it unexpectedly glances up, as if so in tune with everything around it that it could sense the threat. It turns and spots his father, who is lying in the bracken, and the gun resting in his experienced hands. It stares hard, as an amateur writer stares at his first critic, and then leaps away.With a quietly murmured expletive, his father moves, adjusting himself slightly. He breathes out calmly and, holding in his next breath, squeezes the trigger.

He woke with a jerk. Back in the barracks, he suddenly felt calmer. The thoughts of the previous day rushed back. Scott falling, confusion, the sharp spike of fear that lodged itself in everyone. The crack of noise that split through the silence.

‘You win some, you lose more,’ he used to joke. ‘But as long as you catch all your winnings, and drop all your losses, then life’s pretty damn perfect!’

But one thing that William had understood for a long time was that Scott played his

own game, and had been willing to lose as long as he made a difference on the way out. Despite his recognition of this, it was still a shock. He exhaled another shaky breath before getting up.

He was safe, and now that his six month tour in Iraq was over, he could finally go home.

The bullet pierces the deer’s thigh. It squeals and hops onwards with its three working legs. For fifty painful yards it staggers onwards, desperate to escape. Suddenly it stumbles and drops onto its side before rising with hidden strength and carrying on.

Twenty yards later, it stops. It stands there, trembling, and sits down. It makes no effort to lick its wound; it does not even look at it. It just sits there. It knows what is about to happen, and it can’t resist the inevitable any longer.

He sees his father rise carefully and walk over to the deer. He runs a hand gently down the antlers and onto the deer’s neck. He raises the rifle and rests it on the side of the deer’s skull. A gentle squeeze of the trigger ends the deer’s pain. It is free now, free from fear.

William forced his eyes open. A splitting headache cut through the idea of snoozing. He got up and had a much-needed cup of coffee before shutting the front door with his house key clutched in his palm.

He was breathing heavily as he jogged around the park. He was running off the hangover from last night’s celebration with his squadron. Luckily, almost everyone had returned safely. Almost everyone. He always found that running cleared his head, made him calmer. He was glad he had no pockets as it gave him the opportunity to hold his house key. It gave him a little piece of pain that took his mind off everything. The key dug deeper into his hand as he pushed himself up the next hill. He grated his palm along the divots on the underside of the key and felt his clammy hand grow slick with blood. He didn’t want to damage himself, but he needed something to completely consume the essence of his being. Something that wasn’t fear. He ran harder and passed the blood-slicked key across to his other hand. His throat was tightening, and he jabbed the key – point down – into his palm. He felt the sharp pain and almost stopped, growing faint for a few seconds. He pushed on regardless, his pace increasing and his key cutting deeper. His mind drifted away from everything, and he was free. He woke on the cold, emotionless concrete. He had passed out again. Luckily, no one

had seen him, not like last time. He got up quickly and inspected his palms. The blood had congealed and stuck like treacle to his hands. He spread them open quickly, savouring the feeling of the skin re-breaking. His mind wallowed in the sea of pain. He embraced it.

He gathered up his key and began to run home. On his way, his mind drifted back to Iraq. He pulled his thoughts in the opposite direction but it was like playing tug of war with a lorry. He didn’t think that he could go back there. He didn’t think that he could take the strain – both mental and physical. He hated it, constantly having to be in tune with everything around him. Constantly having to spot threats hidden in the undergrowth. Constantly on edge, constantly scared.

Except what he truly feared wasn’t death. It was the feeling of being hunted, and being unable to escape. The fear was ingrained in him as he knew he was being stared at down a scope and no matter how fast he moved, how much cover he found, the bullet would find its way.

He opened his front door and wiped the keyhole with his top to remove the blood. He didn’t want the postman noticing again. He walked inside and headed to his bathroom cupboard, where he kept the antiseptic and bandages. Then he began to open the lid of the antiseptic, deliberately grinding the cut against the grooves that were meant to help him grip the lid. He took a sharp intake of breath as he poured a little of the antiseptic onto his cuts. He got a frying pan out the cupboard, struggling slightly with his newly-bandaged hands, and started cooking his lunch. As usual, he cooked an omelette. It had been his signature lunch ever since he’d moved into this house two years before. He’d cooked it seven days a week, except when he hadn’t been at home. Two tours to Iraq, and nothing dramatic had ever happened. Until the last day of his second tour, when Scott had died.

Thoughts clawed at his mind like hungry wolves. But when he let them in, they ran wild like they were no longer predators but prey. The thought of Scott filled his mind once again. Then thoughts about his next tour, in three months. The feeling of being chased, of not escaping, of not coming home again. The building of dread deep in his stomach slowly overwhelming him. The ambush of anticipation, the sharp feel of bullets burrowing their way home into his legs. Suddenly he calmed down. He carefully got up and turned to the door. He walked up to his bedroom and reached into a drawer. There it was, carefully hidden under a pile of neon striped socks (a birthday present from his friends to ‘put some damn colour in his life’). He held it reverently, like a priest picks up a bible, and took a long look at his salvation. He took a deep sigh of relief and stood up, before walking over to the window. The house opposite was a perfect

point to fix his gaze on. So he stared and rested his chin on the barrel – a comforting feeling. He breathed a deep sigh of relief and squeezed his hand closed.

In Iraq, he had seen the hunter. He’d seen the muzzle of the gun. He was the deer and he was about to be shot. He didn’t want to be the one to give up, to just sit down. He could escape. He could find a way out of the woodland and a place to hide where the hunter would never find him. He would never have to feel the fear of someone else placing a gun to his head and pulling the trigger.

He could do that himself.

I sprint through the deserted alleys and backstreets, grateful of the power this crystal has given me. I can hear the gang’s thudding feet and cruel voices. I screech round the corner and stop dead. They’re there. I spin around. Another gang. How could I be so stupid! Oh well, what’s done is done. I run up the wall.

I suppose I should tell you how I got into that predicament. And how I could run up the wall. Well, it’s hard to explain. My name is Grace Evangeline Ambrose. The year is 2463. We use steam for power. It started in the Black Swan Tavern. The Black Swan is in the borough of Arcport, Kinostorm. Kinostorm is the only city in Astroguard which has a cargo airport. It’s used to transport cogs and metal all over the world. It works, but there’s only room for one person per plane.

Anyway, the Black Swan Tavern. It’s run by Hugh Redmond Eli-Bronze. He’s a nice old guy with a monocle. He’s getting a bit old to run it now, so I help out when I get some free time. Outside of my job, that is. My job is sorting parts at the factory. Not the most exciting job, sure, but it pays well. Well enough to be a regular here. In fact, I come here enough to hear rumours. And one rumour is the reason I got into that quite dangerous situation. Specifically, it’s a rumour about a crystal which can give the holder dramatically increased speed, stamina, strength and reflexes. So, obviously, I went looking for it. Actually it was for a bet. Fifty Blue Yxrunas. In old money, that’s about seventy-five pounds. So, I didn’t want to lose that much. Understandably. So, off I went.

It wasn’t long before I found the warehouse I’d heard about. It wasn’t a particularly well-known one, but it wasn’t shrouded in mystery. I’d made a delivery there once, actually. It looked locked up, but I pushed to see. By luck, it creaked open with a small puff of steam. On the other side, there were lots and lots of crates. I snuck in. After a while of being stealthy and peeping around corners, I started doubting my chances. I started getting suspicious and worried. I couldn’t lift any of the crates, and they would usually be light. I opened one of them. Cogs. Part 1223C. Those were only used in – Oh heck! Type F bombs. I had to get out. If these cogs were in there then type F bombs probably were too. I ran. Even in my panic I tested something.

Left, left, left, left. I should have been back to where I was. But no open crates! I’d left the lid off. That meant

A) that this was a moving maze, and

B) someone now knew that I was here.

Desperate, I sprinted around. I couldn’t find my way back. And now I was even more lost. I sank down next to a crate. Suddenly, a glow from around the corner. Cautiously, I peered around the crate. A pedestal, bright as day in the dimness of the warehouse and on top. I stifled a gasp – a black crystal.

“Hey!”

I whipped around, almost cracking my head on a crate marked ‘This Way Up’.

“What are you doing?”

I zipped around the corner like lightning, grabbed the crystal and, well, time seemed to stop. The voice was no longer shouting and, for the first time, I heard that the ambient noise had stopped. I felt like I instantaneously knew the way out. Then, just as suddenly, I was brought back to reality.

“Boys! Demetrius! Joseph! Martin! Alonzo! Someone’s here! And stealing the Black Glyph!”

And that is how I got into that predicament I described at the start. Next time, I’ll tell you how I got out.

I saw my chance. A parked cart piled high with juicy oranges. It would be easy to jump in the back and hide between them. I didn’t have time to stand there lingering. I had made my decision and now I had to do it. Carefully creeping over a pile of stray squished apples, I fingered my tunic and pretended to look innocent. When I thought no-one was looking, I scrambled into the cart and positioned myself between the oranges. I thought no-one had seen me, but a soldier of six foot was glaring right at me. I sucked in my breath and froze. Thoughts were circling round in my head. “Please, please, don’t notice me. What happens if he does?’ I could be killed, I realised that, but the driver had climbed back into his seat and was flicking the reins to make the horses start up. I breathed again. I was safe, for now. You must be wondering what I was doing, hiding in the back of an orange cart. My mistress would be wondering where I was. I was supposed to be buying cheese and wine, but now, I was on my way home. My mistress, Clara, is a spoilt, stubborn child with piles of sandy hair and great big blue eyes. I am a slave, sold from Thebes to Athens, poked and prodded regularly as if I was a small beetle crawling around on the floor. No-one would care if I died. I’m a nobody. But now I was going home to Thebes, where I could wake up and sniff the olive-scented air and sigh with happiness. Yes, I was going home, but I still had this long journey to make. By now, we were out of the city, rumbling along the filthy track, olive groves either side of us. I longed to go and pick one but I had to focus. The driver’s name was Ajax I had discovered, due to the carving on the side of the cart. Ajax was humming to himself, occasionally giving a short flick of the reins to increase the horse’s speed. The sun was blazing down angrily on us and the back of my tunic was sticking to my sweating back. I was going to boil soon, but I pushed oranges over my head and I was cool again. Cramp climbed my legs and I had the sudden urge to stand up. Ajax would see me though, and I’d soon be a humble loser, sitting by the side of the road. Wishing I had let Clara shave my head, my fingers touched my tousled black hair and I sighed as it was so hot. I hoped we were nearly there. We’d been travelling for what felt like hours. Ajax slowed the cart to a halt and it groaned. I peeped out and realised we were at the entrance to Thebes. ‘Why not jump out

now?’ I thought.

I sprang from my hiding spot and landed neatly on the gravel. I was home and my heart lifted. Strolling casually along, I gazed at this spectacular sight. A group of my old friends ran past and I sprinted to catch up with them. They were squealing and giggling about something and I joined in, like nothing had happened. But of course it had.

My poor, dear, little boy is leaving his home, fleeing from the bombs unaccompanied. Alone. The train pulls up to the platform in a cloud of smoke.

“You’ll be home in a week!” I lie, only to provoke more sad emotions, bubbling up and pouring out.

“I love you, Mummy!” I hear him softly shout. The wardens hold me back from the train; I only hear his words, again and again.

“My son,” I plead. “He’s only four. Give him back.” I try to push through the crowd, but it’s strength I lack, and now it’s my turn to weep, my turn to be alone. My poor, dear, little boy is leaving home.

This poem commemorates the 1.3 million Indian soldiers who came to an unknown country to fight for the British during The Great War.

Home is where the heart is. I heard a British soldier say that here. If that is true, my love, my home is a long, long way from here.

My heart is under the mango tree where its sweet blossoms smile almost as wide as me. Instead shells are pouring like rains in the monsoon, only we don’t know for certain that these will ever stop.

My heart is wandering somewhere far away from this Godforsaken land where night is never silent and stars are never seen. Our richly-spiced food is traded for a cold, hard bread that impales my teeth like the bullets struck in the walls back home.

My heart longs to fly away from here and join the flock of migrating birds escaping the smoke that plumes like wispy ghosts for a brighter land with silks of red, yellow and orange and a sun that beams just as vividly.

My heart longs for freedom, freedom and peace. I have a wish that my children can live in a world with more justice than mine. I do this for a promise, my love. A promise to own the soil beneath our feet.

My heart belongs to the corn fields

and a warm breeze running free. Instead the corpses cover the fields like sheaves of harvested corn.

My heart belongs to the children – hold them tight, my dear. Tell them whatever happens, Papa will always be near. Tell them funny stories, make them laugh from ear to ear; I shall be able to hear their laughter, even from a place as far as here.

Our hearts long to sing; instead they are silenced, hidden among the millions of white crosses surrounding our graves. Why?

We too gave our all when it came to the cry of the fight.

An old Kodak cine film, dated 1938: well-dressed Americans, made good, visiting the old country, recording impressions of shabby streets, people. Long-forgotten, chemically unstable, unwatchable. Unearthed by chance sixty-odd years later. Archive material? Possibly. The Institute pays for restoration and preservation: painstaking, scrupulous work.

Inexpert cameraman, he never guessed his amateurish footage would capture, fleetingly, flickeringly, a life on the brink.

The camera pans along the street, watching children do what children always did, always do, in front of a camera. People jostle out of a doorway, emerge down steps. Banal background trivia: semi-opaque, patterned curtains, potted plants in windows, cobblestones in the market place.

A series of coincidences, fateful accidents, near-misses, internet connections and the film enters our lives. Someone recognises his fourteen-year-old self. The photographer’s grandson arrives –

scholarly, quietly watchful, a skilful interviewer; knowing when to remain silent, when to proffer a tentative name; seeking corroboration but reticent, fearful of planting leading questions. He hopes these fragments of film may bear witness –but they may not. Memories are failing or faulty.

We are bystanders watching the retrieval of memories – the delightful sifted from those too painfully raw to touch upon. My father’s prior stipulation: nothing post-1939. But he talks anyway, in a darkened room, urgently.

Last week I stood asleep on settled dust before your walls raised over anguished earth, with each stone set to vanquish death, yet crushed to ruin. I raised you to my hollow breath and tasted all you were. The livid dust lives for the Galilean’s virgin birth. Placenta accreta, transfusions, stars. All bare to the blasphemer their timeless scars.

I pitied you your centuries, you shell of heaven’s throne. Even the graveyard yews are gone. A yawning chasm halfway to hell devoured the garden and vanished tombs. All here’s as silent as a rusted bell.

The only life the writhing ivy, which pursues the figures of saint and seraphim to claim for nature what of heaven’s ruins remain.

And yet – what grace! A single face adorns the ruin of fragment glass, and still prevails. Aglow as flames within the tomb, born as morning star upon the mourning veil of dawn, the face of life-in-death reborn.

The Word, salvation, wine in the grail. Another face upon the myriad I mourn, and yet within there is that which is glad

of what is not. Of Rome behold the mounds

of bright eternal stone – her famed antiquities; while on volcanic ground, alone, unbound, the Citadel of Sigiriya speaks in shades not sound. From Tripoli, gaze round from writhing sea to rising snow-capped peaks. Marvels amid the vanities of Man. His world a glorious etching, but in sand.

When stone is stone once more, and all design upon the form forgot, return therefore the mineral to the mine; and any sign of our paeans to the gods will be poured out to the clay of nature’s orphaned shrine. I tread upon this tomb, each step assured that all the histories’ vain enmities and amities are ash. O Humility –the majesty of ruin!

The morning mist hangs in the sky, and yet more people come to die. I ask you now, what have they done to set themselves against the gun?

They fight because they’re forced by law, till leaders find a better cause. Taken from their country homes to go and face the great unknown.

After the war, where men fell dead came the poppies, so bright, so red. In the memory of where man’s been. In the memory of what he’s seen.

The trenches now are scars on the land, the ditches and holes grassy and bland, where just a hundred years ago men were running to and fro.

As it comes to this time of year, we’re so lucky. We have no fear. But then, what is remembering those who died serving their king?

For your tomorrow, their final say: they gave to you their final day.

Two indistinct tendrils of vegetable smoke rise and twist in the still air.

Weeds: dock, tares, woodbine; scent of burning like your pipe tobacco, like your frequent bonfires, Grandad.

You stand in the foreground, a spare and compact figure. Hands in trouser pockets, Trilby tilted on your head, watching your handiwork smoulder.

Gone since 1977, you come wavering through the smoke of every autumn bonfire.

From my father, the red sight in the morning mist, the urge out of bed, pull of the sun, at one with the run, dissipating as we move, hidden till dusk, only to return each dull dawn.

From my mother, shyness, a drive for life, permanent appreciation and a tattooed moral code. Stubborn. The immovable object against an apparently stoppable force.

Both offer hope, the warmth I hug to myself, something to help you cope against life’s often-drawn black curtains; that lends you the hands to part them and see through clearly.

Not that smattering of freckles or the tired sullen eyes, the smile lines (not from smiling) on the face I despise.

Maybe the fact that I’m cold, distant, afraid –dread in my throat from unknown rules unsaid.

It’s the snap, the rise, the pulse of anger behind my eyes; the raised voice, the screams, the cries. Inherited or learnt, I know in whose hands the blame lies.

But hey –

‘You and your sister look so alike.’

Her beauty was the envy of the land; the poise and grace with which she carried herself, enthralling. Many were her admirers, obsessed with her deific beauty rivalling that of Amaterasu.

She knew of these affections, but did not care for someone else to dictate every step she took, every move she made. Her life was forced on her by the gods, but she would not let another choose it for her.

She despised the advances of those hopeless romantics who believed they were in love with her, but struggled to turn away the relentless pattern of desperate suitors and narcissistic heirs bursting through the door with expensive gifts.

It did not help that she dared to use the makeup of an empress, would use a delicate kabuki powder on light, rosy cheeks that would pale the softest rose in comparison. No-one could possibly approach this vision of beauty, but one tried.

He was known and revered by many titles –Prince of Paupers, Champion of the Gods, but he firmly stood by one name, his own, Corinth Lowe, Prince of Caucus. He was renowned for his victories in battle, leading his Order of Vagrants, weaving the web of reality with his gift of enchantment.

His fame preceded him from his home in the Temple of Hecate in Greece to the legendary Empire of Hanamura, Japan, to which he had journeyed to broker a peace treaty between his Order and the Emperor.

In spite of this parlay, he heard a persistent whisper eating at him that this calm court might prove to be his downfall.

On his official tour through the capital Corinth sensed a shift in the air, a silence that permeated all, an atmosphere of anticipation. On asking about this silence, the guide provided no answer; only the faeries of the winds gasped, “She’s here! She’s here!” and, “Look at her! Just look at her!”

His confusion had reached its limit. Corinth weaved through the horde of spectators, and saw her. His eyes locked with hers. Who was this muse of perfection, her gaze soft as a breeze, her hair a fountain of dark? She looked back. Who was this most peculiar stranger, his robes white as silver, his windswept locks a shade of lustrous gold? Behind her eyes he saw a trapped beauty, her prison love, her bars the stares and gasps of her sundry admirers. Behind his eyes she saw deep wisdom, a purpose to his every movement and action.

Eventually Corinth mustered courage to speak, a skill those surrounding him had completely lost. “What is her name?”

Completely taken aback by such a clear voice when none else could speak,

the girl herself replied, “Sakura. Shimada Sakura.”

“Sakura. Such a precious name for a woman of the same token.” All those witness to the event could see as clearly as they could the streets they stood on that it was a true love for the ages.

The star-crossed lovers would never be seen apart, cherishing a bond that would never break. The young prince asked for Sakura’s hand in marriage, and, of course, she accepted.

The esteemed Emperor resented these events, as to allow a jewel of his kingdom to be stolen by a foreigner was to surrender all respect from his allies. War was declared.

After the wedding, after the celebrations and the congratulations, the couple heard an uproar in the streets. On gazing outside from the marble palace in which they lay, Corinth saw his beloved city of Caecus in flames. Blood poured in rivers down the streets. Screams filled the city. Soldiers marched on, slashing their blades without mercy. The prince defended his legacy, but one final life had yet to be claimed by that savage night. Sakura lay on the ground beside Corinth as though sleeping, as though undisturbed by the blood in the streets on which she lay. But the blood on the ground told all.

In a fit of sadness, rage, and vengeance, Corinth cursed the Emperor sleeping in bliss with an unending guilt, that the murderer would never forget what he had committed.

The prince’s wife’s blood seeped into the ground, flowed to her home, and it fed the earth, growing trees from which grew blossom the same colour as her makeup, with her same fragrant aroma, flowers many as her admirers –a peaceful memory of a stolen soul.

CARA ADDLEMAN is a Lower Sixth student and an English Scholar.

KITTY ALEXANDER is a Year 11 pupil.

MAX BEAUMONT is a Year 9 pupil.

JENNIFER BENN is a specialist teacher of English in the Learning Support Department.

ANDY BROWN is the author of ten collections of poetry and Director of the Creative Writing programme at the University of Exeter.

TASHA BURNELL is an Upper Sixth student, and lead singer of Frieda People

THEO CAMERON is a Year 8 pupil.

ASHA CHATTERJEE is an IB student in the Lower Sixth.

JEMIMA DENNIS is an Upper Sixth student.

A S M DENNY is a specialist teacher assessor in the Learning Support Department.

LAUREN DICKIE is a Year 7 pupil.

LUKE DORMAN is a Year 11 Scholar and a finalist in the 2018 Senior Debating Competition.

CHARLIE GOODGAME is a Year 7 pupil.

ARTHUR HALES is a Year 11 Scholar.

IMOGEN HALES is a Lower Sixth student.

BELNICE HELENA-NZINGA is a Year 11 Scholar, and the winner of this year’s Senior Verse-speaking Competition. She also holds a BGS record for reciting Pi from memory to 500 decimal places.

AMARA JENKINS is an Upper Sixth student.

FERDIE KEELING is a Year 9 pupil.

NADIA KULIGOWSKI is a Lower Sixth student.

JEREMY LEVETT (OB) is the co-author with Philip Reeve of The Illustrated World of Mortal Engines (Scholastic, 2018)

JAMES ORMISTON is a technician in the Chemistry Department.

NAOMI PARSONS is a Year 8 pupil.

TARANEH PERYIE is an Upper Sixth student and an English Scholar. ‘Richard’ won first prize in last year’s Christopher Tower Poetry Competition.

CAN PEHLIVANOGLU is a Year 8 pupil.

LILLY RUDDLESDIN is aYear 11 pupil.

NADIN SADEK is a Lower Sixth student.

JASLEEN SINGH is aYear 10 pupil. She read ‘The Indian Soldier’ live on television at Westminster Abbey as part of this year’s national Remembrance Day Service.

SOPHIE THOMAS teaches English at BGS and is currently studying for an MA in Environmental Humanities.

ROSA THORNE is aYear 11 pupil.

COLIN WADEY teaches Philosophy, Religion and Ethics at BGS.