8 minute read

The posterior malleolar fracture – is the rule of a third or use of percentages an orthopaedic myth?

Lyndon Mason, Andrew Molloy and Gavin Heyes

Lyndon Mason is a Consultant Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgeon in the Liverpool University Hospitals Foundation Trust. Lyndon is the foot and ankle trauma lead in the Liverpool Orthopaedic Trauma Service and has published widely on foot and ankle trauma management. He is the chairperson elect this year for the outcomes committee in the British Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society.

Advertisement

Andrew Molloy is a Foot and Ankle Consultant in Liverpool University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. His work has been highly regarded internationally. He was one of the founding outcome committee members in the British Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society.

Gavin Heyes is a Consultant Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgeon in the Liverpool University Hospitals Foundation Trust. Gavin specialises in trauma and foot and ankle surgery including the management of diabetic foot disease. His research interests include trauma and foot and ankle surgery.

The Hunterian Professorship is one of the proudest traditional honours of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and is bestowed to surgeons of eminence who have richly contributed to the field of surgery by original research or innovation. It is named after the pioneering surgeon, John Hunter, and has been awarded annually by the college since 1810. Professor Lyndon Mason delivered his Hunterian Lecture on his ground-breaking work on ankles fractures at the BOA Virtual Congress in 2020.

The posterior malleolar fracture of the ankle has come under major scrutiny over recent years with a marked increase in the published literature on the subject. Significant variations in morphology have been described which reflect differing mechanisms of injury1,2. Despite this there are still some that consider fracture fragment size in their decision making3,4. The purpose of this paper is to outline the evidence that formed the basis for the traditional mantra that, “minimal posterior malleolar fractures involve less than one-third of the articular surface” or as some authors quote 25%5. Is there any clinical or biomechanical evidence to substantiate this claim? Can size of posterior malleolus fracture be accurately assessed by radiograph? What evidence is there to support the link with size of posterior malleolus fracture and method of management of the fracture.

The rule of a third

The rule of a third (or 25% by some authors) was first described in the historic paper by Nelson and Jenson in 19405. They described involvement of at least a third of the posterior tibial articular surface as a, “classical trimalleolar fracture” requiring early open reduction. They reported lesser involvement of the posterior articular surface as “minimal trimalleolar fractures” that could be managed by closed reduction and casting and reported good results even in the presence of residual posterior fracture fragment displacement. However, due to its historic nature, the paper would not hold up to today’s level of scrutiny and does not use methods of treatment that would be recognised as standard in modern times. Regardless, the rule of a third became orthopaedic dogma.

Measuring fracture fragment size on a radiograph

The rule of a third or percentage is an approximation of the distal tibial articular surface involved in a posterior malleolar fracture, as gauged from a lateral radiograph. Nevertheless, as early as 1971, Mandell observed that superimposition between tibia and fibula could mask posterior malleolar fractures6. Since the increase in use of CT, the accuracy of the lateral radiograph in determining the degree of articular involvement of the posterior malleolar fracture has truly been called into question. There have been eight publications showing the estimation of posterior malleolar fracture size to be very poor on a lateral radiograph7-14 . As illustrated in figure 1, the position of the X-ray source and its orientation to the sagittal fracture line determines the percentage you can measure. In addition, any posteromedial involvement has a high chance of not being seen as the fracture line is not orientated correctly. Meijer et al. (2015) found that the accuracy of measurement of posterior malleolar fracture size on lateral radiograph was only 22%12. Considering the current literature, basing the treatment of a posterior malleolar fracture on its size on the lateral radiograph is not logical and could be argued, below standard.

Figure 1: Examples of different type of posterior malleolar fractures, with similar lateral radiograph appearance but with very different articular involvement. The blue X and dotted line indicate the X-ray source for the lateral radiograph to show its relation to the fracture line.

Classification

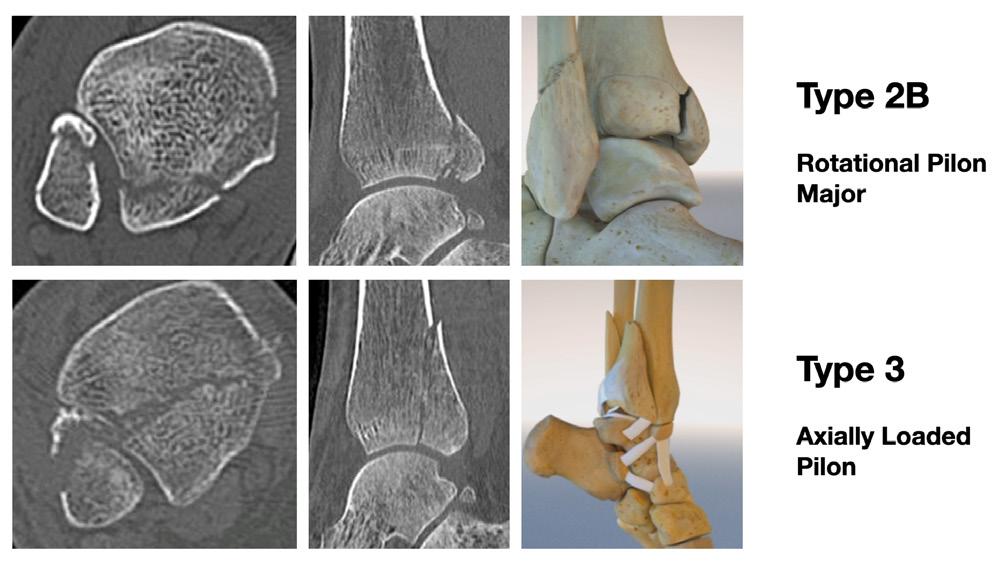

The PMF has long been known to be heterogenous, however percentage articular surface is still discussed as the defining factor. The original classification of the PMF was by Haraguchi et al.15, but this has since been superseded by classifications by Bartonicek Our work on the pathoanatomy of the et al. and by ourselves2,16. Our fracture classification had value in its knowledge of the injury mechanism and its associated injury patterns providing guidance for treatment. The classification can be seen in figure 2. None of the recent classification systems use percentage as their defining factor.

Figure 2: Mason and Molloy classification using CT axial and sagittal slices. Drawing illustrates the differing mechanism for each PM type.

Biomechanics

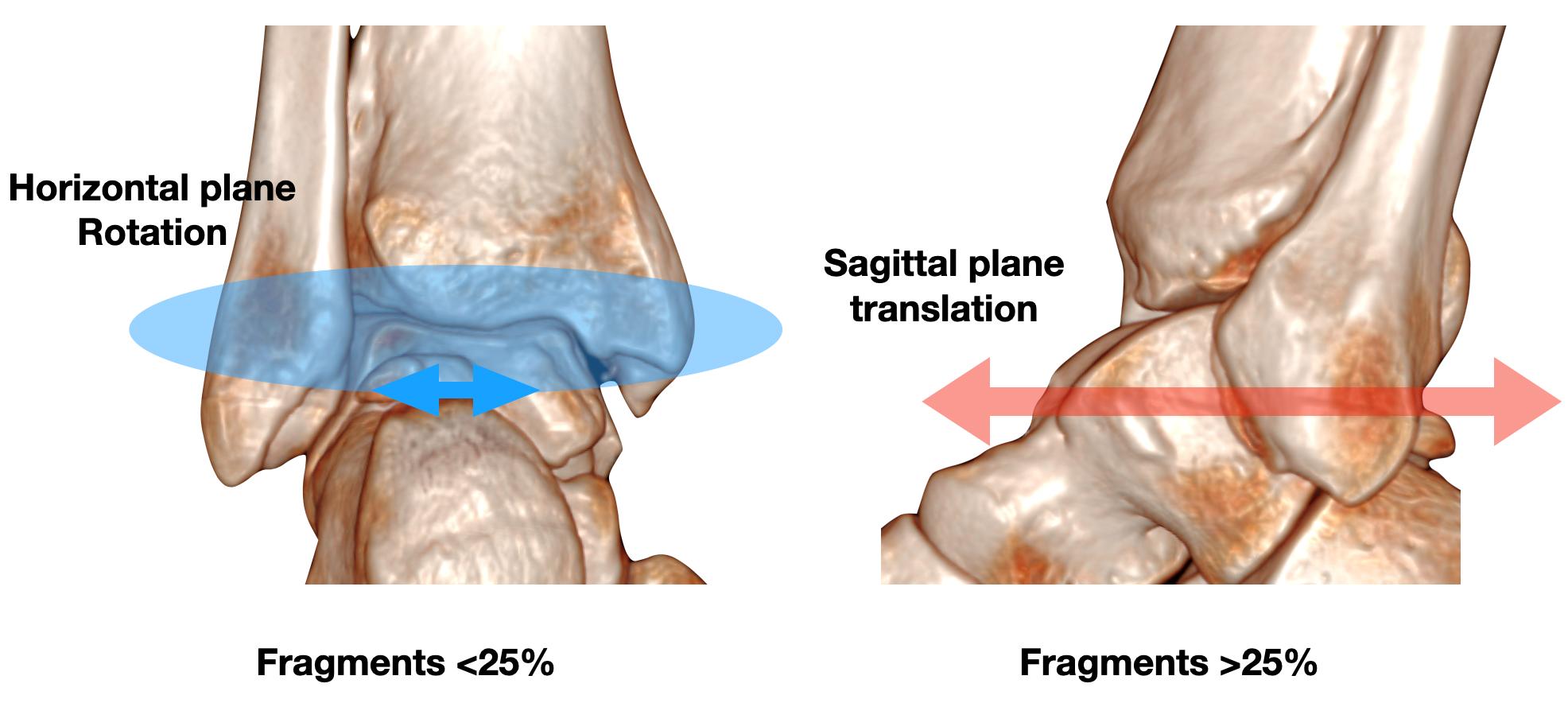

The posterior malleolus has two main functions in the stability of the ankle; preventing sagittal plane translation and horizontal plane rotation (figure 3)17. Unfortunately, apart from the study by Haraguchi and Armiger, all the biomechanical studies in the literature only tested the posterior malleolar fracture in sagittal plane translation18.

Our work on the pathoanatomy of the posterior malleolar fractures identified that the smaller fractures were the consequence of rotation and thus the less than 25-33% fractures were simply not tested1. The assertions made that over a third of articular surface was required to give instability, is really akin to a posterolateral corner injury of the knee being determined as stable by only being tested using a Lachman’s test. More work is needed on the rotation Pilon fracture variant as the paper by Haraguchi and Armiger only tested in pronation with the ankle in dorsiflexion which showed avulsion type injuries18.

Syndesmosis

There are both clinical and anatomical studies looking at the PMF and syndesmosis. Gardner et al.19 found that fixation of the PMF rather than using a syndesmotic screw provided better rotational stability. Whilst they also saw that the rate of stiffness post operatively was higher in those with syndesmotic screw fixation (70% of intact stiffness restored vs 40%). Baumbach et al.20 used three different methods in order to assess syndesmotic activity: no fixation (48.3%), ORIF (33.1%) or CRIF (18.6%). They found that the size of the fragment had no bearing on the rate of syndesmosis injury. They found that ORIF significantly reduced the frequency of trans-syndesmotic fixation compared to the other two groups.

Figure 3: Illustration of the different movements the posterior malleolus is involved in regarding stability.

In addition they found that the quality of fixation was also better in ORIF compared to the other two groups and concluded that all PMF irrespective of size should be treated via ORIF. Miller et al.21 looked at syndesmotic stability when patients are lied supine vs prone. They saw that positioning a patient prone to undertake ORIF of the PMF restored 97.9% of patient’s syndesmotic stability. In comparison 48.3% of patients treated in the supine positioning required some form of additional syndesmotic stabilisation. They also found that a further 29.1% required PMF stabilisation for posterior instability. Fitzpatrick et al.22 even found that the smaller fracture fragments had a greater determination on syndesmotic position than the larger fragments.

Therefore, the PMF is clearly pivotal to the posterior syndesmosis. However, not all PMF have injured syndesmoses. The injury of the syndesmosis is dependent on the mechanism of injury. Although we found that 100% of avulsion type injuries had a syndesmosis injury on testing, only 49% of rotational Pilon’s and 20% of axially loaded Pilon’s had syndesmosis instability1. Further anatomical work by our group concluded this was due to the extensive expansion across the posterior tibia of the superficial component of the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament23. We also found that the more extensive the bone injury, the lower the risk of syndesmosis injury. Thus, if the syndesmosis is injured PMF fixation will improve its stability, however in the rotational and axially loaded Pilon it is not always injured. Percentage joint involvement has no relevance to the PMF and syndesmosis injury.

Outcomes

In 2016 and 2018, two systematic reviews were undertaken looking at the outcomes of posterior malleolar fractures treated by traditional means (fixation only occurred if greater than a third of the articular surface)3,24. Both concluded that there was generally poor functional outcomes throughout the studies reviewed and that articular step-off was the major significant factor in the outcome. They also noted that articular percentage involved had no relevance to outcome. Since 2018, there has been a vogue in fixation of the PMF. Although there has been no level 1 study directly comparing the old dogma and the new vogue, there has been many publications over the last few years showing a marked improvement in outcomes. Blom et al’s25 prospective study showed on multi-regression analysis that in rotational Pilon’s and axial Pilon’s articular step off was key and in avulsion type PMF syndesmotic reduction was key.

Our own work using a treatment algorithm based on the pathomechanic classification was published in 2017, and resulted in a significant improvement in functional outcomes of all fracture types. Our aims were similar to Blom et al., with avulsion type fractures undergoing syndesmotic fixation and Pilon fractures (rotational and axial loaded) undergoing ORIF1,26. The recent paper from the Royal London hospital showed very similar results to ours, using the same treatment theories as ours27. Many other papers over the last two years have also shown very good functional results using similar methods. There has been a big shift away from the rule of third, with apparent improvement in results.

Conclusion

Although numerous historic studies have mentioned that posterior malleolar fractures only need fixing if it is greater than a third or 25%, there is increasing evidence both radiological, anatomical and clinical to show that the rule of third or any percentage should now be discarded and dismissed as orthopaedic dogmatic myth. It is essential that the morphology of the ankle fracture is witnessed as this is one of the only predictors of outcome and will guide treatment. There is general consensus towards the use of CT scanning in the pre-operative management to help determine fragment morphology.

References

References can be found online at www.boa.ac.uk/publications/JTO.