10 minute read

Standing on the shoulders of giants - Reflections on eight years in Malawi

John Cashman

John Cashman was an undergraduate at Southampton University Medical School and trained in Wessex deanery as a registrar. He worked as a Consultant in Bath Royal United Hospital and as a paediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon at Bristol Royal Hospital for Children prior to spending eight years in Malawi with CURE International. John now works in Sheffield Children’s Hospital, is an Examiner for JCIE and Board member of BSCOS.

Advertisement

“Are you serious? Have you really thought about this? Is this fair on your family?”

These were some of the encouraging comments shared with me by well-meaning friends when I first mooted the thought of leaving the UK to work as a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon with a charity in one of the poorest countries of the world.

I was about to complete my first five years as a consultant in Bristol Children’s Hospital and everything was going well; a young family, excellent work colleagues whom I counted fortunate to also be my good friends, a job I enjoyed and even a fun cycle to work each day. Then an email arrived. A charitable children’s hospital in Malawi were looking for a fellowship trained children’s orthopaedic surgeon to help run the only hospital of its type in that region of Africa.

It was a difficult decision. I had visited Malawi as registrar mid-training when I had travelled to see Professor Chris Lavy, who was then one of two orthopaedic surgeons in a country of 13 million people. I had arrived a young man who was struggling with the thought of a life spent doing adult arthroplasty in the UK. I left after nearly three months, having trod in the footsteps of David Livingstone with the naive enthusiasm modelled on Indiana Jones and impassioned with the thought of specialising in children’s orthopaedics. I then determined to become a consultant in the UK in paediatric orthopaedics, but to always be open to returning to a low income country if there was ever a specific need and I was invited. Now, out the blue, these preconditions had been met in one short email.

My wife and I deliberated, I made a hasty visit and we thought and talked. We fought with the fears of bringing small children to a country with endemic malaria with a thin safety net regarding personal health, work acquired HIV and family security. We wondered if we could financially afford it. The costs seemed high and the risks seemed considerable. But there was no peace in saying no. It seemed like an excellent fit and a once in a lifetime opportunity. It appeared the right thing to do. The UK would hardly miss my modest skills, but I reasoned I might really be able to make a helpful contribution in Malawi.

Many reading this will also have at some stage considered working or volunteering in a low income country and I suspect there are many common denominators in this interest. Many will attest to a sense of stewardship. The BOA rightly and frequently reveres the life of our famous surgical predecessors. Their sense of vocation and innovation continue to inspire and challenge us not only to safeguard the baton they have handed us, but to hand it on in turn, not just to the next generation, but to other needful nations. Furthermore many will recognise that at some level we are immensely privileged educationally, financially and professionally and wish to share this privilege with those who materially have very little. Our motivation was no different and as is so often the way, as it turned out there was no sacrifice, only uncountable amazing experiences and memories for which we will always be grateful.

Leaving the UK was helped immeasurably by the kindness and support of my colleagues at work which paved the way to me being granted a two year sabbatical by the NHS Trust, with the proviso I would commit after one year to returning or to resign and stay in Africa. I would commend this as a very worthwhile strategy for anyone considering similar ventures.

We thus left the UK at the end of the summer of 2007 and set up home again in Malawi. The next eight years flew by.

Geographical position of Malawi.

The team

I worked in the Beit Cure International Hospital in Malawi. This is a Children’s Orthopaedic Hospital built in 2002 with aid from The Beit Foundation and run by CURE international – a Christian charity, originating in the US, but with a UK division. The hospital was the product of the vision and hard work of UK orthopaedic surgeons Chris Lavy and Jim Harrison, both of whom are now back in the UK and will be known by many reading this. The hospital provides free care for children with paediatric orthopaedic problems in the country of Geographical position of Malawi. Malawi and extending to surrounding Mozambique and even Zimbabwe. It is set in a pivotal position between the medical school and the main Government teaching hospital called the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital. It has one large open paediatric ward which accommodates up to 52 beds. There is also a small private wing which offers adult private Burns contractures are common, often requiring release and simple local rotational flaps surgery including hip and and skin drafting. knee arthroplasty. This helps raise a significant proportion of the running costs of the hospital as well facilitating private practice for national surgeons, without which it would be practically impossible to live and continue to work.

We all know that a surgeon without a team is completely ineffectual. I was honoured to walk into a team of wonderful anaesthetists, clinical officers, nurses and physiotherapists, all of whom had been assembled and trained by others and on whom I was completely reliant. There were also fantastic colleagues and friends in national surgeons from Kenya and Uganda who helped train me in a new way of working, as well as Jim Harrison to help orientate me.

Burns contractures are common, often requiring release and simple local rotational flaps and skin drafting.

Training

The majority of trauma care in the 25 District General Hospitals and several smaller mission hospitals around the country is delivered by Clinical Officers. They are the equivalent of ANPs. Helping support training of these clinical officers, medical students, and orthopaedic registrars was a great privilege and good fun. The real credit must go to the local Malawian surgeons, Professor Nyengo Mkandawire who was then the orthopaedic lead and to Jes Bates who organised the registrar training programmes, to whom we simply lent support.

We also hosted at least one UK trainee every year on our Fellowship programme. It was enormous fun to share the excitement of the work with a UK trainee and see in turn them flourish from merely competent surgeons, to confident surgeons with a rounded experience and an often reignited passion for orthopaedics.

The pivotal geographical location of the hospital meant it was easy to run training courses. Our proximity to the medical school cadaveric dissection room, to the adjacent Central Hospital and to our own lecture theatres and seminar rooms meant that we were able to run courses for orthopaedic trainees both nationally and internationally. Instructional courses undertaken included those relating to paediatric orthopaedics, trauma management, limb reconstruction, knee surgery, foot and ankle surgery, plastic surgical reconstruction and Ponseti clubfoot treatment. These were often supported by visiting UK surgeons and charities and societies such as the Furlong Foundation, THET (Tropical Health and Education Trust) and BOFAS. The legacy of these still bear fruit today as I hear of past trainees around Africa still using and perfecting techniques first learnt at one of these events.

Smiling and happy patients at CURE.

Ponseti programme

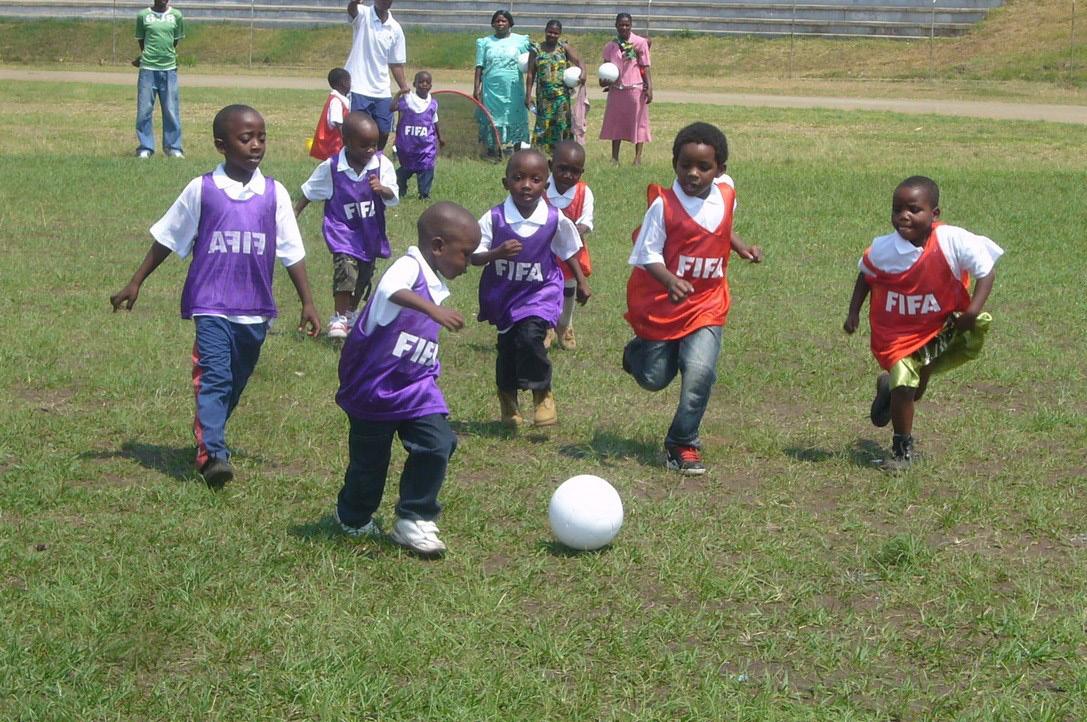

CURE Clubfoot Worldwide (CCW) helped finance the formal establishment of a national clubfoot programme, following on from some foundational training by Chris Lavy and Steve Mannion some years earlier. With the help of a national programme coordinator, I was given the job of setting up 28 treatment centres in hospitals around the country and furthering the training of clinical officers and rehabilitation assistants (physiotherapy assistants) with regular training courses. CCW financed the provision of foot abduction braces and we organised their local manufacture and distribution. The resultant drop-off in numbers of children needing major surgery was notable and gratifying: seeing just some of the thousands of kids successfully treated happily playing netball and football at a FIFA sponsored event at our five year anniversary was incredibly moving.

The children

Falling in love with the country was easy. Malawi is beautiful and whilst its people are often grindingly poor, their friendly welcome and resilience are inspiring. I was rarely able to show visitors around without being rendered speechless by the sense of privilege of being part of such an amazing team offering world class surgery to the poorest and needy of children and their families. The pathology presenting was exciting and challenging and included chronic osteomyelitis, severe burn contractures, sequelae of neglected trauma, angular limb deformities, neglected clubfoot and many rarer congenital limb deformities that would be plentiful as there was no other source of help nationally or even regionally in that part of Africa. Fortunately with a fine array of UK donated Ilizarov and TSF instrumentation, there was not much that our unit was unable to cope with. Being asked to preside over nine lists per week with only one outpatient clinic brimming with pathology, is perhaps a surgeons dream.

Chronic Osteomyelitis is a very common and challenging condition treated.

Clubfoot football – a prerequisite to play was that you had to have been born with clubfeet and treated by the national Ponseti clubfoot programme.

The lows

There were few low moments and these were eclipsed by the many happy memories, but challenges included nearly losing our nine month old daughter to severe croup as there was no paediatric ventilator available in the entire country. There were also times that we lost friends to road traffic accidents and tropical illness which were also hard, but such problems are not exclusive to Malawi. Taking two different courses of antiretroviral therapy for needle stick injuries or eye splashes in HIV positive cases was also irritating, but the knowledge that seroconversion is almost unheard of was very reassuring.

Conclusion

The only contributions I was able to make in my eight years in Malawi were entirely contingent on others, including the dedicated surgeons, both Malawian and from the UK that continue to live and work there and have invested their lives in training and improving the lot of their countrymen. We were also reliant on the committed hospital team that made the work possible and the financial support we had from CURE and from supporters in the UK. As Sir Isaac Newton now famously attested: “If I have seen further, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.” I cannot claim to have seen further, but can affirm that any contribution we made was built on the hard work of others.

Faculty and delegates from instructional course on knee surgery.

I have listed one or two personal recommendations for those considering giving time to working in a low income country, (Box 2). I have never met anyone who regretted doing so. Personally it was most rewarding and is a continual reminder to me to be grateful for our NHS and all that we have professionally in the UK. But those considering similar would do well to ponder the words of Mark Twain: “Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did do.” There is rarely a convenient time to leave the securities of what is known as home and invest oneself elsewhere, but I am so thankful we were able to.

Box 2: Recommendations in supporting orthopaedics in Low Income Countries

• Find a colleague or contact working in a country that you can support. Ask them what they need, not offer what you might have spare.

• Consider joining a teaching course (e.g. basic surgical skill / basic trauma course / other surgical instructional course) and visit the country. See if there are ways you can support existing surgeons or training schemes.

• Consider linking hospitals in UK with those overseas to promote and support education / research etc.

• Consider volunteering to provide skills as an external examiner or help running logistics of an exam or course.

• Consider taking a longer period of leave for 4-6 weeks to cover leave of a surgeon working in a hospital overseas.

• Consider taking a two year sabbatical / early retirement to support training overseas.

• Be humble and non-judgmental. You will invariably learn and gain more than you can give.