SPECIAL FEATURE CORRUPTION

FALL 2022 ISSUE 02

FALL 2022 ISSUE 02

SPECIAL FEATURE CORRUPTION

FALL 2022 ISSUE 02

FALL 2022 ISSUE 02

There is a written record of corruption dating back to before 3,000 BCE in Ancient Egypt, according to some archaeologists. But corruption—most generally defined as the abuse of entrusted power for personal gain—has probably existed for as long as there has been power to exploit. Fast-forward 5,000 years, and corruption still pervades. The World Bank estimates that internationally, $1.5 trillion are paid in bribes every year, accounting for roughly two percent of world GDP. By the World Bank’s own admission, this figure probably underestimates the actual extent of corruption: While a common stereotype of corruption involves largescale quid pro quos—think Providence’s own Buddy Cianci, who used the mayor’s office to solicit large bribes—countless dollars go toward small bribes to low-level bureaucrats. These types of bribes, because they are illegal, furtive, and often quite small, are near-impossible to measure.

The overwhelming majority of people believe that corruption is harmful regardless of its scale. By distorting competition, preventing efficient use of public funds, and discouraging investment, corruption is bad for economic growth. Corruption can also kill people;. It is not uncommon for politicians and bureaucrats to extract money intended for public investment, resulting in accident-prone infrastructure and under-equipped health care facilities.

The authors in this issue explore these dimensions of corruption, but also some of the less noticeable consequences. In her article, Antara Singh-Ghai describes how Russia’s state-sponsored doping and abuse of teenage figure skaters in the Olympics has degraded the sport internationally, harming competitors and the purity of the sport.

Corruption can also contribute to environmental degradation and displacement of indigenous peoples. Charles Alaimo shows how the Tanzanian government’s desire to profit from the sale of land to international tourism businesses has left many Masaai—the land’s native occupants—without homes.

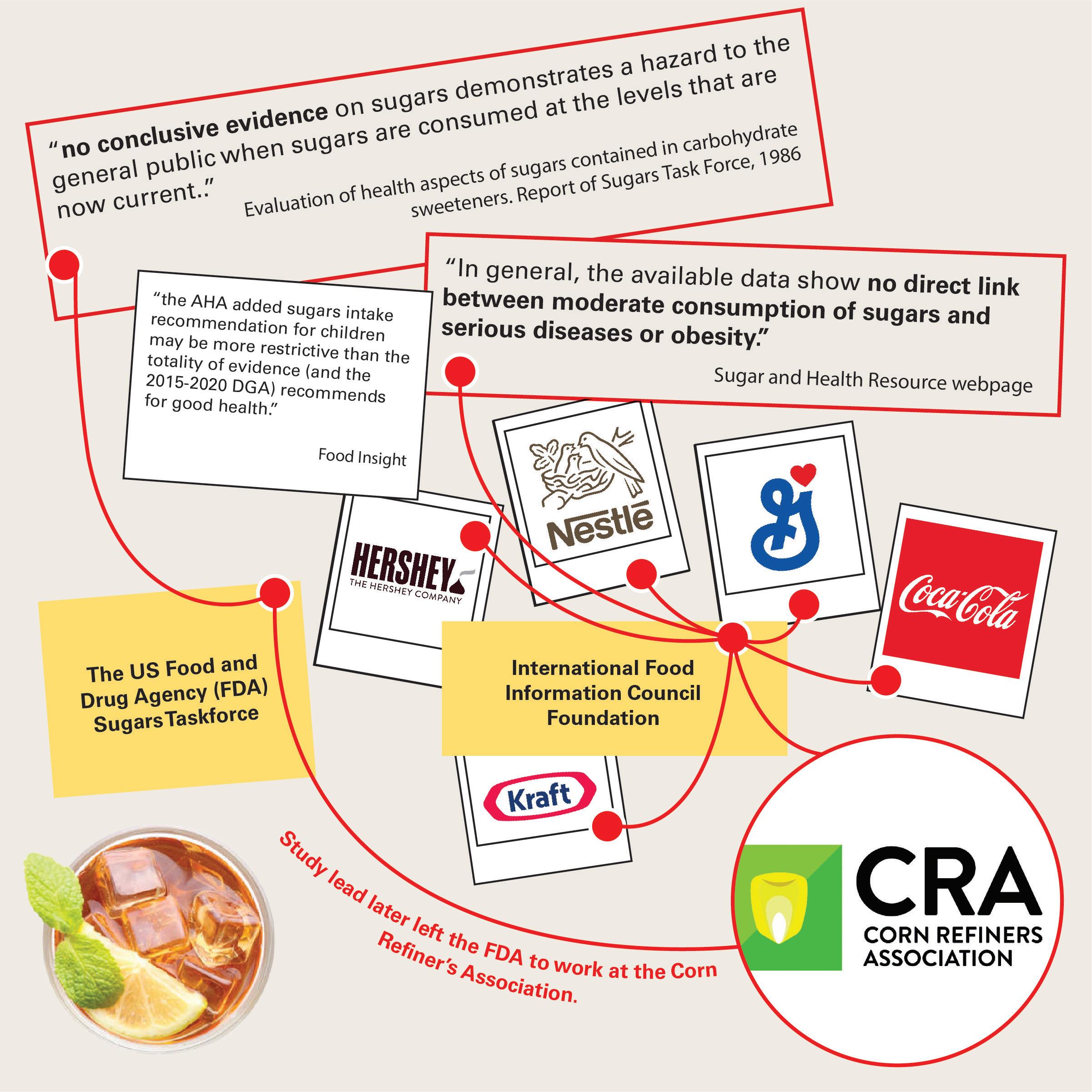

Annika Reff explains that corruption even influences what we eat. By funding scientific studies that underplay the negative health effects of sugar and spending millions on lobbying Congress, the sugar industry—together with legislators and regulators prone to the industry’s influence—has made a high-sugar diet the norm in much of the United States.

While corruption is a serious political issue, Roni Wine shows how allegations of corruption can be misused, a problem perhaps most salient in Brazil. Former President Jair Bolsonaro rose to power in the wake of the imprisonment of his predecessor (and now current President) Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. It turned out that the corruption charges were poorly substantiated and distorted by a Bolsonaro-aligned judge.

Lastly, Bryce Vist sounds the alarm about corruption in Ukraine. Regardless of the outcome of the war, the rebuilding effort will take hundreds of billions of dollars. Ukraine and its international donors must confront the country’s history of graft, ensuring that funds for rebuilding do not simply line the pockets of oligarchs and well-connected politicians.

We hope this Special Feature shows you some unique harms corruption can cause, and perhaps motivate you to think about how corruption affects your community, your country, or even your daily life.

Gabe and MattEDITORS IN CHIEF

Gabe Merkel

Matt Walsh

CHIEFS OF STAFF

Casey Chan

Sarah Roberts

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICERS

Daniel Halpert

Gidget Rosen

SENIOR MANAGING

MAGAZINE EDITOR

Nathan Swidler

MANAGING

WEB EDITORS

Chaelin Jung

Morgan McCordick

Mathilda Silbiger

CHIEF COPY EDITORS

Robert Daly

William Lake

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Alex Fasseas

Miles Munkacy

DATA DIRECTORS

Zoey Katzive

Arthi Ranganathan

BUSINESS DIRECTORS

Daniel Halpert

Gidget Rosen

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Daniel Navratil

Christine Wang

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Elijah Dahunsi

LEAD WEB DEVELOPER

Sarah Roberts

SENIOR MANAGING

MAGAZINE EDITOR

Nathan Swidler

MANAGING EDITORS

Alexandra Mork

Joseph Safer-Bakal

Ye Chan Song

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Grace Chaikin

Harry Flores

Isabel Greider

Lauren Griffiths

Justen Joffe

Caroline Parente

David Pinto

Cole Powell

Bianca Rosen

Antara Singh-Ghai

Bryce Vist

Archer Zureich

MANAGING

WEB EDITORS

Chaelin Jung

Morgan McCordick

Mathilda Silbiger

SE NIOR EDITORS

Natalia Ibarra

Sarah McGrath

Isabella Yepes

EDITORS

Ben Ackerman

William Forys

Jillian Lederman

Alex Lee

Matthew Lichtblau

Kara McAndrew

Francisca Saldivar

Isaac Slevin

Jack Tajmajer

ACTIVISM SECTION EDITORS

Sofia Barnett

Amanda Page

Gabby Smith

STAFF WRITERS

Ilektra Bampicha-Ninou

Anna Brent Levenstein

STAFF WRITERS CONT.

McConnell Bristol

Morgan Dethlefsen

Neve Diaz Carr

Henry Ding

Juliet Fang

Amina Fayaz

Michael Farrell-Rosen

Sophie Forstner

Isabella Garo

Oamiya Haque

Ashton Higgins

Katie Jain

Elsa Lehrer

William Loughridge

Bruna Melo

Christina Miles

Alexandra Mork

Kayla Morrison

Rohan Pankaj

Annika Reff

Andreas Rivera Young

Jodi Robinson

Bianca Rosen

Mira Rudensky

Ellie Silverman

Elliot Smith

Ian Stettner

Peter Swope

Maddock Thomas

Man Hei Christopher Wai

Jesse Ward

Ben Youngwood

Sofie Zeruto

Suzie Zhang

CHIEF COPY EDITOR

Robert Daly

William Lake

MANAGING COPY EDITORS

Andrew Berzolla

Isabel Greider

COPY EDITORS

Emily Colon

James Dallape

Khalil Desai

Mira Echambadi

Juri Kang

Connor Kraska

Caleb Lazar

Dorothea Omerovic

Jimena Rascon

Lilly Roth-Shapiro

Roza Spencer

Audrey Taylor

Sabina Topol

Hao Wen

Logan Wojcik

Ivy Zhuang

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Daniel Navratil

Christine Wang

DESIGN DIRECTORS

Erin Isla Roman

Hope Wisor

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Muhaddisa Ali

Patrick Farrell

Youjin (Amy) Lim

Kara Park

Alina Spatz

Ivy (Airu) Zhang

Tina Zhou

ART DIRECTORS

Rosie Dinsmore

Jacob Gong

Lucia Li

Anahis Luna

Lana Wang

Kelly Zhou

DATA DIRECTOR

Zoey Katzive

Arthi Ranganathan

DATA DESIGN DIRECTOR

Lucia Li

DATA ASSOCIATES

Veer Arora

Carson Bauer

Ashley Cai

Allie Chandler

Elsa Choi-Hausman

Khalil Desai

Ryan Doherty

Raima Islam

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Alex Fasseas

Miles Munkacy

DEPUTY INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Mira Mehta

Samuel Trachtenberg

Alexandra Vitkin

INTERVIEWS ASSOCIATES

Ahad Bashir

Carson Bauer

Omri Bergner-Phillips

Allie Chandler

Léo Corzo-Clark

Elise Curtin

Elijah Dahunsi

Alexander Delaney

Mira Echambadi

Ava Eisendrath

John Fullerton

James Hardy

Alice Jo

John Kelley

Stella Kleinman

Sam Kolitch

Seungje (Felix) Lee

Alexandra Lehman

Alyssa Merritt

Lauren Muhs

Hai Ning Ng

Matteo Papadopoulos

Maya Rackoff

Anushka Srivastava

Emma Stroupe

Anik Willig

Hiram Valladares Castro-Lopez

Yuliya Velhan

Tucker Wilke

Asher Labovich

Nicole Lugo

Javier Niño-Sears

Colby Porter

Logan Rabe

Francisca Saldivar

Jakob Siden

Giang Thai

Zhou (Harry) Yang

Yifan (Titi) Zhang

DATA DESIGNERS

Icy Liang

Hannah Jeong

Mahnoor Rafi

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Elijah Dahunsi

MULTIMEDIA ASSOCIATES

Ilektra Bampicha-Ninou

Garv Gaur

Ashton Higgins

Julia Kostin

Haotian Luo

Daniel Ma

Ruairi Mullin

Taha Siddiqui

Michael Seoane

Jonathan Zhang

COVER ARTIST

Iris Xie

ILLUSTRATORS

Jason Aragon

Ashley Castaneda

Naya Chang

Jocelyn Chu

Kyla Dang

Thomas Dimayuga

Nicholas Edwards

Pauline Han

Maria Hahne

Grace Li

Elizabeth Long

Wenqing (Ash) Ma

Temilola Matanmi

Rosalia Mejia

Kennice Pan

Ji Hu Park

Shreya Patel

Kira Saks

Evelyn Tan

Ayca Tuzer

Madison Tom

Rachel Zhu

BUSINESS DIRECTOR

Meghan Murphy

ASSOCIATE BUSINESS DIRECTORS

Charlie Key

Gidget Rosen

BUSINESS ASSOCIATES

Charles Adams

Rachel Blumenstein

Cannon Caspar

Stefanie Del Rosario

Carys Douglas

Peter Edelstein

Jake Garfinkle

Ellyse Givens

Nadeen Kablawi

Stella Kleinman

Matias Meier

Michael Obiomah

Nicolas Pereira-Arias

Martin Pohlen

Arthi Ranganathan

Alexandra Rubinstein

Last year, 16-year-old James Bascoe-Smith was stabbed near his home in south London. From his wheelchair, Bascoe-Smith testified at the Old Bailey court about his life-altering injuries. The jury was told his attack may have been provoked by an online drill video, making him an “innocent bystander” in a raging gang war. Fortunately, he did not join the list of 30 teen homicide victims in London in 2021—a record figure. The story of Bascoe-Smith is a tragic but all too common one. Every week opens a new wound in the hot-button issue of knife crime and drill music in the capital of the UK. Like all ‘chicken or the egg’ questions, the presence of a causal connection between drill and crime is debated. Regardless of the answer, music censorship is a misguided solution to London’s knife crime epidemic.

Music has always sparked moral outrage. In the 1960s, rock was denounced as a radical, unchristian influence on America’s youth. The War on Rock reignited in 1999 when the Columbine High School massacre spurred a conservative reaction against metal and goth music. Over the years, similar accusations of glamorizing drugs, sex, and violence were echoed against gangsta rap and hip-hop. In 2017, Fox News reporter Geraldo Rivera famously claimed, “Hip-hop has

done more damage to young African Americans than racism.” And just last summer, lyrics written by rappers Young Thug and Gunna were used to indict them on racketeering charges. Meanwhile, House representatives debated proposals to render song lyrics inadmissible in court. In Britain today, a similar debate is being played out.

The new target of outrage is drill music, a subgenre of hip-hop originating in Chicago that has crossed the pond over the last decade. UK drill is defined by its ominous beats and raw portrayal of street life, which sometimes veers into graphic accounts of violence. The genre has been politicized in debates over knife crime—an “epidemic” that kills almost two Londoners a week. Unlike many topics of media coverage in the United Kingdom, both the conservative-leaning tabloid press (e.g. Daily Mail) and broadsheet “quality press” have engaged in fearmongering; in 2018, a widely-circulated Sunday Times article labelled drill “the ‘demonic’ music linked to rise in youth murders.” A controversial Policy Exchange report argued that over 25 percent of London gang murders are linked to drill, which the report alleges is a cause of revenge killing—a common theme in the style’s violent lyrics and the sometimes direct threats they communicate. In response, prominent criminologists signed an open letter dismissing the report as baseless and racially insensitive.

The debate has sent shockwaves across the fashion, music, and entertainment worlds. Brands like Adidas have come under fire for spon-

Censoring rap is no fix to London’s knife crime epidemic

soring convicted artists, as the sportswear giant launched an ad campaign with rapper Headie

One just months before his imprisonment for knife possession. Despite his major commercial success, Headie One remains entangled in an explosive north London gang war. While he maintains that drill is not the root cause of gang violence, other rappers have acknowledged the connection. Speaking on crime, drill rapper Incognito confessed, “You’ve got to put your hands up and say drill music does influence it.” Shortly after making these remarks, Incognito himself was stabbed to death. With the instant and viral reach of music videos, drill is a plausible accelerant to gang violence and may provide a commercial incentive for knife possession as a means of demonstrating authenticity to an online audience.

The potential connection between drill and knife crime does not make censorship the solution. The close partnership between London’s Metropolitan Police (Met) and YouTube is particularly troublesome. Since 2018, hundreds of drill videos have been removed at the request of the Met, which aims to “carry out ‘profiling on a large scale’” on males aged 15 to 21. This government intervention not only infringes on free speech and artistic license but also verges on racial profiling. Drill aside, when law enforcement agencies censor art to influence public discourse, they wade into dangerous territory. While drill has influenced some past acts of violence, the Met is ill-equipped to differentiate between

songs making genuine threats and those merely chronicling or dramatizing personal experience. Contemporary drill is a largely theatrical display that fabricates and plays into existing stereotypes to appeal to a substantially white audience. Most drill rappers have no connection to organized crime and merely leverage this image for commercial purposes. For a 92 percent white police force, the risks of “street illiteracy” and racial bias are especially salient when exercising sweeping powers of censorship.

Unlike gun crime in the United States, knife crime in the United Kingdom is a subject of bipartisan consensus; most agree it is a problem that needs addressing. Berated on soaring crime rates in the capital, Sadiq Khan has become the one of the most unpopular recent mayors of London. Unwise stopgap solutions include censoring drill music and expanding police stop-and-search authority. A better, more sensible approach treats knife crime as a public health problem. It would establish youth clubs in underserved areas, improve economic opportunity for London’s poorest, and implement prison reform to end the cycle of incarceration. Though drill has played some role in gang conflict, it is far from the root cause of the knife epidemic. A sensationalist press has dragged this problem to the forefront of a national culture war, distracting policymakers and the public from realistic solutions to knife crime. For this reason, we must drop the War on Drill.

“Like all ‘chicken or the egg’ questions, the presence of a causal connection between drill and crime is debated. Regardless of teh answer, music censorship is a misguided solution to London’s knife crime epidemic.”by

Ezra Klein is a New York Times opinion columnist and host of the podcast The Ezra Klein Show. Before moving to The Times, Klein co-founded the news site Vox, where he served as editor-in-chief. He is also the author of the book Why We’re Polarized, which examines the rise of political polarization in the United States.

Tucker Wilke (TW): I’ve seen a lot of people say, “All of this polarization we have now is because of Trump, and once he’s gone, we’ll go back to normal.” In your book Why We’re Polarized, you push back against this idea. How would you respond to the idea that polarization is gone in a post-Trump America?

Ezra Klein (EK): There’s an old Larry Summers paper that is sort of famous in the economics profession because it questions the idea of the rational economic agent. Its first line, famously, is “there are idiots. Look around,” and I would say, “there is polarization, look around.” Look at Covid-19, look how that is split.

I think that if anything, I underestimated the power of polarization. When I was writing my book, I would have said that a virus that kills at this point nearly a million

Americans would be the kind of thing that is so directly relevant to people’s lives that political polarization is not going to have much of an impact. It’s one thing to be polarized about abstract questions of policy that you don’t really understand: What’s gonna happen with climate change, or should China be branded a currency manipulator? But an illness that could get you sick and kill you, or your family members, or your neighbors, or your friends?

I would have thought that the incentive to get good information and act on it would’ve been pretty high, and I have been surprised by that.

TW: How did the pre-existing polarization in the United States impact people’s perceptions of the pandemic?

EK: I think a lot about a counterfactual Covid-19. Imagine that in 2012, Mitt Romney won the election. And in 2016, he won re-election. So when Covid-19 comes, we are toward the end of his second term with a Republican president who is an empirical, conscientious, mask-wearing type of guy, no matter what you think of his positions on taxes and entitlements. Does Covid-19 polarize the way it did? Does it polarize equally but differently than it did? Do you have more of a liberal reaction against things like vaccines?

Go back a couple of years in the vaccine debate, and the view is that it’s weirdos in California who won’t get their kids vaccinated for measles who are putting everybody at risk. I remember covering that for a bit. That obviously isn’t what the central driver turns out to be during Covid-19 over vaccine skepticism. So it’s very hard for me to know how much of what we’ve seen reflects idiosyncratic dimensions of Donald Trump’s response and public persona and personal tendencies, as opposed to some kind of inevitable interplay of political coalitions and psychologies.

TW: On the topic of Trump, how do you think his rather extreme brand of polarization affected the response to the pandemic?

EK: So one fun, constant question about Trump is, “is he a symptom or a cause?” And he’s obviously both. But one trend behind polarization that he reflects and accelerates is the clustering of conspiratorial, low-trust people in the Republican Party, and Donald Trump himself is one of these people. He is a guy who, way before his political career, was constantly trafficking in conspiracy theories and all sorts of weird stuff. He is clearly not a person who trusts institutions or believes in their value. He is authentic to the Republican Party that is emerging, so when he runs, he resonates with so many Republican voters. And when he becomes the nominee, more low-trust people join the Republican Party.

And I bring that up to say that a Republican Party that has become structurally mistrustful of institutions—full of people who will disbelieve something the media says because it is the media that said it—is a party that is not well set up for Covid-19 and similar situations. At certain, critical moments, you do need to believe things that you take on faith from people who’ve run experiments in labs. And the fact that the United States polarized

around conspiratorial thinking did not set us up well for a Covid-19 response.

Omri Bergner-Phillips (OBP): A lot of that conspiratorial thinking seems to be spreading over social media. How do you think social media intersects with polarization? If you had the power to do so, how would you adjust social media platforms to help decrease polarization?

EK: It’s worth saying the enormous bulk of the rise in polarization long predates social media. Polarization is not a social media phenomenon, though I think social media is making it worse. But social media, too, is responding to a long structural change in American political life.

I would re-tune the algorithms to have a circuit breaklike tendency as things begin to go viral. One of the ways social media is changing politics is by ratcheting up the emotional tenor. It supplies you with content to feel strongly about. In some areas, that means the content is funny. In politics, it means the content makes you very angry.

And we get a lot of it. Instead of social media hungrily searching out things that will go viral, I would like it to not do that. I don’t think it’s good to live our lives with this level of hyperstimulation. I think this is true in areas outside of politics, too. But within politics, it would be better if the algorithms preferred things that were getting a modest response from the people who read them. Rather than preferring everything that was getting a super strong response.

OBP: Given how social media exploits the personal side of politics, what spaces do you prefer for talking about issues that are important to you, such as veganism or reproductive rights?

EK: I primarily talk about both of the things you’re mentioning in podcasting. I almost never talk about those issues on social media.

I don’t think abortion is something to debate. I personally don’t think I’m likely to make the world better by talking about abortion, or the death penalty, or veganism on Twitter. I don’t think I’m going to create a constructive space of reconsideration. On my podcast, I think I’m able to build a relationship with the audience over long periods of time. When I say something that’s a little unusual or that’s outside the way they naturally view the world, they might be willing to venture with me there.

I value places where you can be a more whole person— podcasting being one of them, but not the only one—or places that lend themselves to a healthier form of politics. I think if you can see me in my deeper humanity, you might be more willing to listen to what I’m saying. And if you feel that I’m seeing you, you might be more willing to tell me what you’re truly thinking. That’s a precondition for any kind of persuasion in either direction.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

“Polarization is not a social media phenomenon, though I think social media is making it worse.”

to deceitfully obtain property deeds that deprive indigenous communities of their ancestral lands. But by working with non-governmental organizations and increasing oversight, South American governments can curb this continued land theft.

Although digital registries are relatively new, the ethos underlying their exploitative use is not. During the colonial period, debates over land registration and ownership in South America were often at the forefront of violent conflicts between European colonizers and the indigenous groups they displaced. Since then, land-grabbers have capitalized on the general lack of centralized land registration systems and regulatory policies to claim ownership of community-owned lands without legal deeds.

Brazil’s Cerrado region, the most biodiverse savannah in the world, is home to the geraizeiros, a population of mixed Afro-Indigenous and European descent. Since their arrival in western Bahia over 200 years ago, the geraizeiros have lived in small villages in the savannah lowlands (baixões) and the plateaus (chapadas), cultivating the land with care and respect.

However, because many geraizeiros lack official deeds to the lands they live and work on, companies have recently been able to expand into the region and kick them off of the land they have occupied for decades. These companies laid claim to vast swaths of uncultivated

land in the Cerrado before converting the native vegetation to soy, corn, and cotton monocultures. The Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America alone has acquired at least 800,000 acres of farmland in Brazil, primarily in the Cerrado region. These aggressive business practices have severely impacted the geraizeiros, leaving most of them displaced and disconnected from their ancestral lands.

Sadly, the story of the geraizeiros is not unique: Native communities across South America have faced similar fates. In recent years, many countries in South America have digitized their land registries and established online databases that serve as birth certificates for rural properties. While land registries are not inherently harmful, mega-agribusiness corporations such as Cargill and Archer-Daniels-Midland use these registries as well as georeferencing technologies

In 2020, GRAIN, a small international non-profit supporting small farmers and community-controlled food systems, launched an investigation into how these new digital systems function. In its report, GRAIN argues that in several areas of rapid agribusiness expansion in South America, the digital system is “validating the historic process of land grabs.” Rather than recognizing the long-standing land claims of traditional communities, the report alleges, the system is expelling native communities from ancestral lands that they have occupied for decades, or in some cases centuries. Affected communities live in regions including the Llanos Orientales of Colombia, four states in the Brazilian Cerrado ecoregion, and three areas along the Paraná River.

Within each of these regions, landowners are required to register their land in what is formally known as a georeferenced cadastre—a supposedly exhaustive record of a given country’s property—if they wish to acquire the legal land deed, bank credits, and loans. Since the World Bank partially funds the cadastre process in many South American countries, georeferencing tools allow the international financial sector to play a decisive and expanding role in converting community-held rainforests and savannahs into agribusiness land. In Brazil, for

How georeferencing technology has been used to steal indigenous territory

example, the World Bank shelled out $45.5 million for the digital registration of private rural properties in the country’s rural environmental cadastre, allowing it to generate income from investments in agroforestry systems.

Unsurprisingly, this outsourcing of power and authority has had dire consequences for many indigenous communities. The cadastre system caters to the needs of large companies and private actors who want to register individually owned allotments of land. The bureaucracy of cadastral documentation, coupled with the rigidity of the cadastre system’s definition of land ownership, makes it difficult for some native communities—many of whom collectively occupy their land—to register their plots. Cadastres’ early iterations fail to record land occupation by these communities, making them “illegal trespassers” on the property they work and live on. The new landowners can then use the official cadastre and georeferencing records to go to court and evict traditional communal owners. Condoned by the rampant corruption in rural municipalities and courts, this sequence is disturbingly common.

Although much of this problem stems from misuse of georeferencing technology, the issue calls for a political solution. Local and national governments must put agrarian reform and collective land ownership issues on their political agendas. Governmental land use groups and agencies—the South American equivalents to the United States Bureau of Land Management—should allocate public lands to rural peoples in order to guarantee their collective territorial rights. Digital georeferencing

techniques for land demarcation can and must be backed up by traditional ground truthing surveys. And rather than taking prospective landowners’ claims at face value, governments must independently verify them via a centralized land registration system organized to resolve conflicts.

Even if the government does not act, there are still a number of ways to guarantee land rights for indigenous communities and other rural peoples.

In 2019, the International Land Coalition (ILC) published “ILC Toolkit #9: Effective Actions Against Land Grabbing,” describing several strategies that landowners and activists alike can use to combat the global land-grabbing phenomenon. One of the primary ways the ILC encourages local groups to resist land-grabbing is through the development of community land registries, which allow landowners to register their customary land rights into a government cadastre and obtain formal land titles or certificates. This process helps integrate many indigenous peoples’ customary rights into the legal system and establishes proper land rights that help communities protect their lands.

The Higaonon, an indigenous tribe in the Mindanao region of the Philippines, has successfully implemented this practice and holds

much of its land under customary tenure systems. Still, the lack of clear boundaries between neighboring groups has led to many disputes. In response, the Higaonon applied for a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT), a formal land ownership title. However, despite their efforts, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples has only formally registered 50 CADTs, limiting their effectiveness in protecting indigenous land.

Traditional knowledge and production systems—existing sustainably on communally held land—protect natural resources and are vital for human survival. But the longevity and viability of these systems are being put at risk by the “digital land grab.” We must do everything in our power to stop it.

“The bureaucracy of cadastral documentation, coupled with the rigidity of the cadastre system’s definition of land ownership, makes it difficult for some native communities—many of whom collectively occupy their land—to register their plots.”

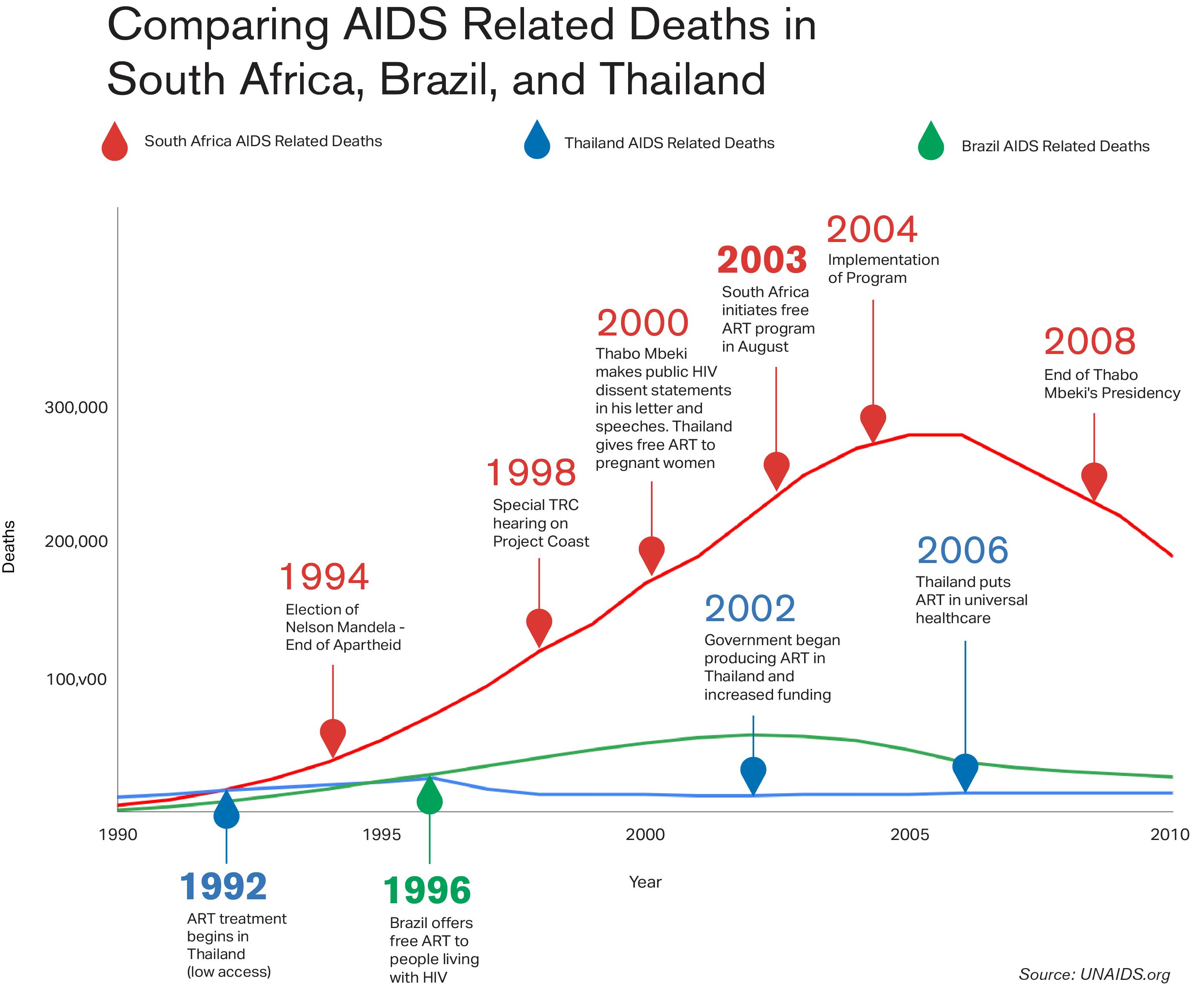

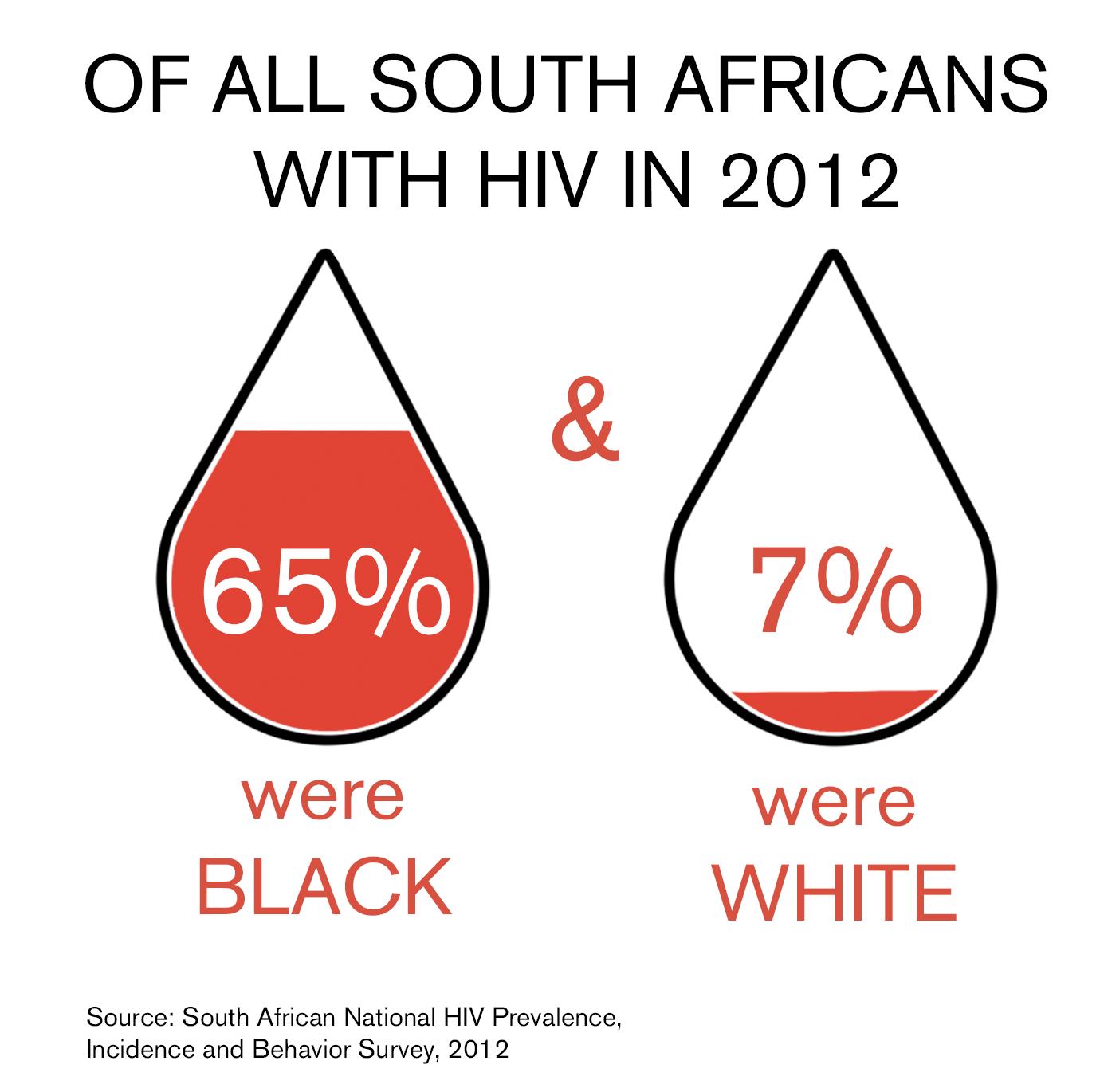

The South African government has a longstanding history of HIV denialism. Throughout his presidency from 1999 to 2008, Thabo Mbeki continually questioned the validity of HIV research. Infamously, he presented his dissenting positions in a letter to world leaders in 2000. In speeches that same year, he stated, “A virus cannot cause a syndrome. A virus can cause a disease, and AIDS is not a disease, it is a syndrome.” In addition to this rhetoric, Mbeki sponsored panels that highlighted dissenters from current HIV research, furthering his pseudoscientific views. As a result, HIV conspiracy theories became rampant in South African political life. Mbeki’s claims were met with immediate backlash from media outlets, AIDS activists, and healthcare organizations. However, these responses disregard the South African historical context. The legacies of apartheid, corruption, and colonialism that linger in the South African collective consciousness provided the perfect climate for conspiracy theories around HIV/ AIDS to proliferate.

In South Africa, public health and systemic oppression have been intertwined for over a century, with the racial segregation of healthcare codified by the 1883 Public Health Act. Under this act’s emergency provisions, Black South Africans were removed from urban centers during flare-ups of the Bubonic Plague. Between 1900 and 1910, this policy surrounding Plague epidemics resulted in the sweeping loss of property for Black South Africans. This period of racial segregation became impressed upon the national consciousness of South Africans. It was a time when racism was thinly veiled as public health policy.

In later years, fearful of anti-apartheid movements, the South African government

began investing in Project Coast, an operation within its chemical and biological warfare (CBW) department. Former military doctor Wouter Basson headed this project, modeling it on programs in other countries. Allegedly, this bolstering of the CBW department was originally intended to combat chemical weapons threats during the South African conflict in Angola. Testimonies from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings, however, uncovered it to be an effort to possibly commit genocide against the Black population.

Researchers attempted to create a bacterium to target Black individuals. Additionally, Basson’s team investigated how CBW such as cholera and micro-organisms could be deployed for population control. One of the most terrifying projects included a vaccine to covertly sterilize the Black population. This effort became extremely explicit during the TRC hearings, in which one doctor stated that their “final brief, [...] was to develop a product to curtail the birth rate of the Black population in the country.”

These genocidal plans coincided with the faulty AIDS response by the apartheid government throughout the 1980s and 1990s. As soon as AIDS began afflicting the Black population, the government response reflected the enduring racism in South Africa. The voices of rightwing parliament members offered an alarming prophecy of the destruction to come. Dr. F.H. Pauw claimed that the Black majority would no longer be a threat due to many dying of AIDS. Conservative Party MP Clive Derby-Lewis stated, “If AIDS stops black population growth, it would be like Father Christmas.” While the government eventually attempted to advocate for contraceptives, this only aggravated anti-apartheid groups and was seen as another method of reducing the Black population.

When Nelson Mandela was elected in 1994, his post-apartheid government inherited a public health system riddled with mistrust and an increasing number of people living with HIV. In fact, in 1994, 7.6 percent of South Africans were

The legacy of apartheid South Africa in addressing the HIV pandemic

“The legacies of apartheid, corruption, and colonialism that linger in the South African collective consciousness provided the perfect climate for conspiracy theories around HIV/AIDS to proliferate.”

HIV positive (compared to 0.7 percent in 1990). This figure would only keep growing, hitting 22.4 percent in 1999. South Africa’s crippled healthcare system needed to address this growing crisis, yet officials refused to acknowledge the results of HIV studies, slowing government interventions.

One of the biggest failures of Mandela’s new government was its refusal to properly use the antiretroviral drug azidothymidine (AZT), the primary treatment given to people living with HIV at the time. In other countries, AZT helped

address mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy. Scientific evidence highlighted that proper use of AZT—when taken in tandem with cesarean sections and formula feedings— results in a near-zero mother-to-child transmission rate. Still, Health Minister Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma claimed otherwise, espousing the view that AZT was too expensive and ineffectively addressed the pandemic. Her successor echoed similar sentiments, arguing the drug’s benefits did not outweigh its toxicity. Dissenting from scientific evidence on antiretroviral drugs, the South African government failed to respond to the HIV crisis: A study from the Harvard School of Public Health estimated that more than 330,000 people died prematurely and 35,000 babies were born with preventable HIV infections. An antiretroviral treatment program was not implemented until 2003, three years after Mbeki’s troubling letter was presented.

Despite these obvious failures, they must be considered in the context of apartheid’s oppression. The legacies of a racist, morally bankrupt colonial government lent themselves to a poor response to the growing HIV crisis. This legacy helps explain why the government withheld the authorization of AZT. With the discovery of genocidal planning and anti-fertility research, the post-apartheid government was sensibly wary of drugs specifically marketed toward mothers. Coupled with the fact that Western pharmaceutical corporations were heavily pushing and profiting off of the drug, the government was extremely cautious of AZT in the post-apartheid era.

Mbeki was extremely hesitant to blindly accept wisdom from countries that participated in the oppression of his people. In his letter, he emphasized that prohibiting HIV dissent is “precisely the same thing that the racist apart-

heid tyranny we opposed did.” He also highlighted the unique nature of the African HIV crisis, a claim which some have misconstrued as stating that there existed a new African source of AIDS. Yet, the HIV crisis itself in South Africa— and other countries affected by colonialism—is unique. Many challenges come from grappling with the legacy of apartheid, which undoubtedly fractured the response from the onset. This begs the question: Can we really judge a leader for not trusting their oppressors?

Today, the legacy of apartheid continues to influence public health in South Africa. In 2020, South Africa had approximately 7.8 million people living with HIV, and around 19.1 percent of people ages 15 to 49 had tested positive for HIV.

South Africa has the fourth highest HIV prevalence rate and the greatest number of people living with HIV in the world, making it a pressing matter of consideration for global health.

This consideration became especially apparent once the Covid-19 pandemic struck, since HIV has left many South Africans immunocompromised. Coupled with low vaccination rates, South Africa and other sub-Saharan African countries were at high risk for Covid-19. This had a global impact: Some scholars believe that the Omicron variant originated in South Africa in part due to its sizable immunocompromised population, which put it at greater risk of mutations appearing.

While one cannot trace back every public health failure to apartheid governments, it is important to note the lasting legacies of oppression left by them. It forever changed the consciousness of South Africa, as the memories and trauma of apartheid have not been erased with transitions of power. This sentiment is not confined to South Africa, but rather, it is the case in every country with a deep oppressive history. Medical mistrust is especially pervasive among Black Americans due to systemically racist medical malpractice and a centuries-long legacy of chattel slavery. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, while perhaps the most infamous, is only one example of a racist weaponization of science against the Black community. Similarly, many

indigenous populations also continue to distrust post-colonial medical establishments.

Every colonizing power must reflect on its weaponization of health, as they have colored the modern-day responses to public health crises. How can we expect people to “trust the science” if the source has an untrustworthy track record? While it is easier said than done, governments must invest time and resources into mending the wounds that they inflicted. Without addressing past atrocities, conspiracies will continue to run rampant, frustrating the global response to future health emergencies. As the world is hopefully on the tail end of the Covid19 pandemic, the present moment stresses the urgency of reconciling prior wrongdoings for the sake of the health of all eight billion people on the planet.

“Dissenting from scientific evidence on antiretroviral drugs, the South African government failed to respond to the HIV crisis: A study from the Harvard School of Public Health estimated that more than 330,000 people died prematurely and 35,000 babies were born with preventable HIV infections.”

Anik Willig (AW): What got you into the field of immigration law, and what did you witness as both an immigrant yourself and a lawyer that made you start Touching Land?

Carolina Rubio-MacWright (CRM): Growing up in a place that wasn’t safe, I felt like my body was always threatened. Since moving to the States, having freedom is a feeling that I carry with me. As a law student, I went down to the border with the Texas Civil Rights Project, and got to see and hear stories of other immigrants.

After law school, I started working at the public defender’s office and witnessed a lack of proper representation for immigrants. I was determined to practice immigration law and make sure that I could teach people what their rights were. Touching Land came about later in my career. I was already a resident in this country, and I started doing a lot of public ‘Know Your Rights’ workshops. I wanted to figure out how I could make these workshops less threatening and more of a relaxing environment. I wanted to do more somatic practice. Art became a form of documenting stories we cannot understand with words.

AW: What kinds of injustices did you witness while working at the public defender’s office and inside detention centers?

CRM: In the public defender’s office, a client was incarcerated for two years and had no access to sunlight. People told me, “This is a ridiculous right that you’re fighting for.” I think honoring people’s humanity, whether they’re in prison or not, is important.

In detention centers, we saw a lot of really horrible things that were severe violations of human rights. I think that it’s really hard to see a child unable to get a hug when they’re crying, or listen to a mom that is telling you about her sexual abuse experience. Why are we incarcer-

Carolina Rubio-MacWright is an artist, immigration lawyer, and activist fighting for immigration justice. An immigrant herself, Rubio-MacWright moved to the United States from Bogotá, Colombia at 20 years-old to escape violence. She graduated from Florida International University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts and moved to Oklahoma City where she received her J.D. She has served as an attorney in Miami, Oklahoma, and New York City and currently works in Brooklyn. Through her organization, Touching Land, she has developed ‘Know Your Rights’ workshops that empower immigrants with legal knowledge, and she continues to use experimental mediums, like clay and cooking, to stimulate conversation.

ating humans that are seeking help? That to me is unfathomable, and that’s why I organize groups to go down to these centers and be true agents of change.

AW: Could you talk a bit more about Touching Land and how it has brought a community of immigrants together?

CRM: Touching Land is a non-profit which includes the Empowerment and the Building Bridges programs. The Empowerment program brings together immigrants, both undocumented and documented. Immigrants come to a beautiful art studio in Brooklyn, which would otherwise be very expensive and inaccessible. For four weeks, we have classes on what to do if Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) shows up at your door, what type of resources your children have at schools, and so on. The average salary of those that come to my classes is $8 per hour. We teach them they should be making $15 and how to negotiate. We assess what the needs of the group are, and then along with every class, they also build sculptures with their hands. It’s a very kinesthetic and beautiful way of learning.

The Building Bridges program is a mixed space where we bring together empowered immigrants and people of privilege from a neighboring community. We sit them together and they share their humanity while creating an art piece together. They share stories and take a little piece of each other with them. We are trying to give immigrants visibility, and trying to create not just allies, but co-conspirators.

AW: You’ve been very outspoken about ending policies like Title 42, a pandemic-era emergency health order that allows the president to turn away migrants at the -

southern border. What other policies would you like to see either dismantled or enacted?

CRM: I would do away completely with detention centers, and create welcoming centers that would allow people to have resources. Many people, if they don’t have the right resources and drop their cases, become part of the estimated 12 million undocumented people in the country. Then they don’t get any financial help from the government. I would create a stipend. I would also do away with the three- and 10-year bar, which is the rule where if you cross the border and stay here for more than six months or a year, then you have to go back to your country and can’t come back to the United States for three or 10 years, respectively. When that rule was created, we prevented migrants from working here and being able to go back home. We screwed Central Americans who depended on money made from farm work in this country and would then invest it in their homelands. We prevented them from having mobility.

AW: What do you think is the best way for people to get involved and make change in their communities?

CRM: I always say, “don’t be discouraged.” Joy is an act of resistance. All it takes to make change is to become active in your local organizations. If immigration is your thing, reach out to the Hispanic organization in your town and see how you can advocate. The system is really screwed, but we are so lucky to live in this country. Just being able to drive with my window down is a joy I can’t explain, because I couldn’t do that for my entire life in Colombia. In moments of despair, I go to my community. I go to joy. I go to the beauty and the magic of our impact, and I don’t stay in despair.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Greece is undeniably beautiful: a Mediterranean haven that promises a rich, historic culture and a gorgeously cerulean sea. Or so argues the Greek summer advertisement released two years ago to promote tourism after Covid-19 devastated the industry. The video asks: “What makes Greece so precious? It’s not the sea. It’s not the sun. It’s more than that.”

It is certainly much more than that. It is also a state rife with corruption that has historically turned a blind eye to racist micro-aggressions, racial slurs, beatings, and even murders, all perpetuating oppression.

Afro-Greeks—African immigrants and Greeks of African origin—are often victims of racist attacks, carried out primarily by members of the Golden Dawn, a far-right, neo-fascist, and ultranationalist political party that rose to prominence during Greece’s 2009 financial crisis. It became the third most popular party in the Greek parliament during the January 2015 election. The party’s infiltration of the Hellenic Police, and its surging popularity among sup-

porters of Greece’s former military junta, have led to six dark and unsettling years for AfroGreeks and immigrants.

Nonetheless, blaming the financial crisis as the sole factor driving racist phenomena in Greece is as easy as deeming the Golden Dawn the single culprit of discrimination. Racism existed in Greece far before 2009—people were just too ignorant to name it. Neo-Nazis, alt-right supporters, and neutral spectators of racist incidents are just as responsible for the xenophobic ordeal Afro-Greeks and immigrants are going through. Although the rise of the Golden Dawn was the fuse that lit wildfires of anti-Afro-Greek hate, accountability equally lands on the shoulders of a predominantly white electorate that chooses to either remain apathetic to injustice and fear or not vote at all in the parliamentary elections.

In October 2020, a Greek court finally labeled the Golden Dawn as a criminal organization—only after a white Greek man was murdered—but the racism and corruption that the group perpetuates are far from over. Racism makes it difficult to stand against corruption, and corruption discourages victims of discrimination from demanding justice.

Corruption is undeniably a prevalent theme in Greek history. In April 1967, police officers led by Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos launched a

coup d’état, establishing the 1967–1974 military junta. Thereafter, Greek politics were characterized by single-party majority governments that alternated between the socialist and conservative parties. Coalitions, in other words, were rare. And even if coalitions are more common nowadays, the remnants of these sharp, bitter pendulum swings of the past are still present: Most Greek parties still identify as “Right,” “Centre,” and “Left.” Today, New Democracy is the leading center-right political party and SYRIZA its major leftist opposition. The two have continued a long tradition of political dualism and childish tantrums thrown by opposing ministers of Parliament.

With the collapse of the Warsaw Pact states in 1989, immigration to Greece was transformed, becoming a massive and uncontrollable phenomenon. Immigration from Africa followed soon after. The main wave of African immigrants started in 1997 and continued throughout the 2000s. Most came from Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nige-

ria, Ghana, Cameroon, and Somalia. Today, the majority of Afro-Greeks live in central neighborhoods of Athens, like Patisia and Kipseli.

Until 2010, no legislation recognized the citizenship of people who had been born and raised in Greece and whose parents had immigrated to the country. The right to Greek citizenship was granted to children of immigrants born or raised in Greece in 2015, though the examination questions are so highly specific that not even a typical Greek citizen can know all the answers. Thus, obtaining Greek citizenship has come to replace a previously absent legal framework with an absurd exam process as well as the usual slowness of the public sector, meaning that an Afro-Greek might remain legally stateless for up to five years until their Greek citizenship is granted.

To gain Greek citizenship as a second generation resident, there are three pathways: firstly, having been born and currently living in Greece with parents who have permanently and legally lived in the country for at least five years; secondly, having successfully completed at least six years of Greek education, while permanently and legally residing in the country; and thirdly, applying for Greek citizenship at a public service center in the three years after turning 18—a process that costs 100 euros.

Would the process of gaining citizenship be as complicated and time-consuming if the Greek Parliament were more ethnically diverse? Would it take years to sentence the Golden Dawn as a criminal organization if Afro-Greeks were represented in the government?

The life of an Afro-Greek is one of of duality and contradiction. On the one hand, an AfroGreek is refused a job at a store because they threaten its prestige. An Afro-Greek athlete is not Greek enough to represent the country in international tournaments or even to play for the local sports team. An Afro-Greek woman is catcalled or considered a sex worker because all Afro-Greeks must be poor, desperate, and turning to sex work for income.

On the other hand, Greeks recognize that a minority can be extremely beneficial for advertisement purposes. An Afro-Greek suddenly becomes the perfect fit for a Greek yogurt commercial. Afro-Greek actors are now beginning to play roles in theater and television other than the caricature of an uneducated, kind-hearted,

“There are two ways an Afro-Greek can be presented by the media: either as a criminal, with the ethnicity of the accused strongly highlighted in the headlines, or as an exceptional immigrant.”

and hardworking Black comic relief with an exaggerated African accent. The token Black employee in a Greek Nike store signifies that the company is diverse, its mindset international.

Observing this reality, it is easy to note that there are two ways an Afro-Greek can be presented by the media: either as a criminal, with the ethnicity of the accused strongly highlighted in the headlines, or as an exceptional immigrant. Take Giannis Antetokounmpo, an Afro-Greek born and raised in Sepolia but not a legal Greek citizen until 2013. Although some who challenged his nationality were very eager to view him as Greek once he became an NBA superstar, he still is not fully socially accepted, as evidenced by the racist reactions on social media after his recruitment by the Greek National Basketball Team for Eurobasket 2022.

Not all Afro-Greeks are internationally ranked athletes. Does that mean they should not be accepted as Greeks? Excellence being the only way to gain respect and overcome racism is a manifestation of larger inequality and corruption in Greece. Equality and representation

should never depend upon exceptionalism; it is a basic human right to be acknowledged and treated with respect.

Action must be taken to compensate for the unfair treatment of the Afro-Greeks: realistic representation of Afro-Greeks in the Greek Parliament, not just as tokens, but in numbers representative of the vast diversity of Greek society. Reform within the legal system and the public sector is necessary to make the process of obtaining legal documents, including Greek citizenship, less convoluted.

Greek identity must be reinvented to account for Afro-Greeks because we exist and are here to stay.

“Although the rise of the Golden Dawn was the fuse that lit wildfires of anti-AfroGreek hate, accountability equally lands on the shoulders of a predominantly white electorate that chooses to either remain apathetic to injustice and fear or not vote at all in the parliament elections.”

by Miles Munkacy ‘24, an International and Public Affairs major portraits by Erin Isla Roman ‘23, a Graphic Design major at RISD

Editors’ Note: This interview was conducted before the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2022.

Eunice Yoon ’95 is a correspondent and bureau chief with CNBC based in Beijing. She is known for her coverage of the pandemic, from the initial outbreak in China to her insights on the tense US-China relationship. Prior to CNBC, she worked as an anchor and correspondent with CNN International, among other networks. At CNN, she was among the first journalists to reach the Sichuan earthquake zone in 2008, and together with her team, she received the prestigious DuPont Award for coverage of the Asian tsunami in 2004. Yoon holds a Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Political Science from Brown University.

Miles Munkacy (MM): There’s a lot of talk about the upcoming National Congress this fall. Do you expect there to be any major changes to the Communist Party’s agenda, or any major political wrangling or surprises?

Eunice Yoon (EY): Right now the baseline assumption is that President Xi is going to get an unprecedented third term. Up until now, we’ve generally seen a regular transition of power at the top, and, for years, there’s been collective leadership. However, it now looks as if China is increasingly moving toward one-man rule. That has a lot of implications for China as well as the rest of the world.

You mentioned some possible political wrangling. Some factions of the party may try to change a thing or two; that’s always the case. However, all of that goes on behind closed doors and most people, except for probably

a very small number of people, really don’t know what’s going on at the top. There has been some rumbling that President Xi may not get a third term or that he won’t be able to have all the deputies that he wants because of some of the criticism that his administration has now faced from the zero-Covid policy. You could argue that if China was a democratic society, then he could potentially be in for a very rough election, but that obviously doesn’t happen here. So, while there may be rumors, most people still believe that there will be few surprises, if any, and that he is going to be getting his unprecedented third term.

MM: How has China’s zero-Covid policy changed its domestic political situation? Is it as dramatic as most Western news media have reported, or is the situation on the ground less severe?

EY: There’s definitely been pushback against zero-Covid. There are a lot of people who’ve been very disgruntled by the way it has been implemented. From the Chinese government’s perspective, zero-Covid has been wildly successful because it has generally achieved its goal of containing the pandemic. The country has not seen the hundreds of thousands of deaths that you’ve seen in the United States and other parts of the world. So, you have to give them credit; they are saving lives. The question now, though, is whether or not you can actually achieve those successes without what has been seen outside of China (but also within the public here) as excessive and sometimes abusive behavior on the part of different officials in order to achieve zero-Covid. There are a lot of arguments being made that it can be done in a way that would make it more tolerable for the population. For example, making sure that people locked down have enough food, or perhaps not splitting children who test positive from their parents.

MM: Another major political headache for China has been the problems with Evergrande, as well as the Chinese property sector in general. There’s been a lot of analysis on what the Chinese government and public think about that issue, but what about the private sector and the business community? How are they experiencing the property sector crisis?

EY: The property sector has been such a huge driver of the economy for so long and most companies just thought that would always be the case. China is a huge country with massive cities, so there are a lot of people who need housing. For the most part, property was seen as a good investment from both a company and individual perspective, especially considering that China’s stock market still isn’t very developed. However, the government recently saw that there was a lot of money in debt that was pumping up the prices, and so they decided that it was better to try to get rid of some of that debt because they were worried about what that could potentially mean for China down the road. However, I think some private companies saw the methods that they used to do that as quite harsh, especially some of the measures that led to Evergrande, and eventually other real estate companies, starting to become much more unstable. It has now led to a situation where regular people are wary to invest in homes because it’s no longer seen as a safe and stable investment, even if

at some point in their lives they definitely want to own a home. So, right now I don’t think that many private real estate developers are too happy about the situation.

MM: There’s been a lot of hope in the West in recent decades that China will become a more open economy. However, it seems as if China has moved further away from that goal in the last few years. As someone who reports on the Chinese economy every day, what do you think about its trajectory toward or away from market economy status?

EY: Well, China is becoming, or at least wants to become, a more self-sufficient economy. At the same time, you’re seeing a lot of talk within the United States about making sure supply chains are secure, which is a polite way of saying that Biden doesn’t want the United States to rely as much on China. Because of those two forces at play, it makes it much more difficult for businesses, especially American businesses, to decide whether they’re going to invest more in China even if it maintains that it will remain welcoming to foreign investment.

Covid-19 restrictions are also a huge concern for businesses. There are a lot of companies who are now trying to figure out if they want to have their production based in China because they’re worried about their factories suddenly being shut down for a month.

However, I think something that doesn’t get as much attention as bilateral trade and investment relationships is the fact that so many American companies and companies from around the world are looking at China as a place to invest in to sell their products locally. Companies such as GM or Starbucks are looking to expand within China. That adds to this very complex moment in the very important US-China relationship. While both countries definitely want to be more self-sufficient, that’s a much harder thing to do in practice given that there are just so many economic links between the two that have been cultivated for decades.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

“It now looks as if China is increasingly moving toward one-man rule. That has a lot of implications for China as well as the rest of the world.”

Rohingya Muslims, long denied Burmese citizenship and identity, are no closer to seeing a new age of justice. Having been targeted by Myanmar’s military juntas and Rakhine State’s Buddhists for years in a brutal genocide, the group’s prospects seem to have scant hope for improvement. Now living in the state of Rakhine in devastating poverty, Myanmar’s remaining Rohingya population has endured even more suffering since the military coup in 2021, which has restricted their access to basic health care, food, education, and travel.

In the face of such oppression, Rohingyas are once again fleeing to neighboring countries, where they are greeted less than warmly. Bangladesh reports that it is currently sheltering one million Rohingya refugees and argues that the rest of the world has done “absolutely nothing” to ease this burden. But this global apathy and discrimination toward Rohingyas is nothing new. Examining Myanmar’s complex history shows a deep-seated hatred for the group, catalyzed by post-colonial tensions, Islamophobia in Asia, and Burmese militarism. The intersection of these factors has led to the present-day situation in which the Rohingyas have no nation to call their own.

The term “Rohingya” is itself controversial. Most citizens of Myanmar do not acknowledge the existence of a separate Rohingya community, instead describing the Rohingya as direct descendants of Bengali immigrants who illegally settled in Burma during the British colonial reign. In reality, the exact origin of the Rohingya ethnicity is difficult to discern, with the earliest documented use of the term occur-

ring in 1799. Historians do confirm, against popular belief amongst the Burmese, that Muslims were present in the region long before the British took over Burma. For instance, there is evidence from the 15th century of a hybrid Buddhist-Islamic court presided over by the Arakan kings of old.

The Muslim population of Arakan climbed throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, eventually reaching a high of 179,000 people in 1911, compared to a mere 58,000 in 1871. Many use the population increase as evidence to argue that the present-day Rohingya are descendants of these immigrants and consequently do not have proof of Burmese ancestry preceding the British Raj. As a result, they cannot claim Burmese nationality under Burmese law. Indeed, the 1982 law that formally codified the ethnicities of Myanmar conspicuously failed to include the Rohingya, rendering them illegal migrants in the eyes of the law.

But the systematic discrimination by the Burmese state with respect to the Rohingya cannot be explained just by concerns over illegal migration. The darker ramifications of colonialism are also partially responsible.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Britain’s “divide and rule” strategy had already intensified ethnic hostility throughout the

Raj. In Burma, this took the form of policies encouraging the migration of “loyal” Indians to counter the influence of “less reliable” Burmese. During World War II, India, Burma, and other British colonies came under threat of Japanese conquest, further straining ethnic tensions between groups. The Burmese National Army— commanded by the future “Father of Burma” Aung Sang—sided with the Japanese, while the Rohingya Muslims sided with the British, aiding their Allied Burma Campaign and receiving a (later to be broken) promise of independence in return. Fighting on opposing sides of a war perceived by many as a struggle for liberation only aggravated existing tensions between the government-backed Rakhine Buddhists and the Rohingya Muslims.

After a little over a decade of democratic rule following the end of World War II, the government of Burma was replaced by a military junta, worsening Rohingya Muslims’ conditions. The Burmese army-turned-government then initiated a series of crackdowns against the Rohingyas in an attempt to drive them out of the country. In 1977, the government initiated a program called Naga Min with the aim of bringing every resident’s citizenship under scrutiny as a guise to discriminate against the Rohingya. Killings, mass arrests, and torture as a result of the program drove over 200,000 Rohingyas to flee to Bangladesh. This state violence against the Rohingyas has continued to the present day. In 2017 alone, more than 310,000 Rohingyas fled the country, and 6,700 were killed in what has been described as a pure massacre, an ethnic cleansing, and a genocide.

Such brutality cannot be explained away as merely a product of colonial history. To this day, Muslims in southeast Asia are generally regarded with suspicion unless they live in a Muslim-majority nation—a result of the anti-Muslim sentiment that has been brewing in the region for decades. Many Rohingya Muslims are forced to seek refuge in nations like Pakistan or Bangladesh—places where they are not welcome due to

their being perceived as Burmese. In Myanmar, the Rohingya’s supposed homeland, the group’s Islamic traditions and practices cause them to be viewed with even more mistrust, as demonstrated by the use of the slur “Kala”—a word that suggests that Rohingya are dark-skinned aliens of Indian origin living in Myanmar. But the Rohingya don’t seem to be welcome in India either. The pro-Hindu, anti-Muslim Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that governs India calls the Rohingya “terrorists” or “infiltrators” and refuses them proper shelter. It is not a stretch to reason that the general Islamophobia that has taken root globally since the 9/11 attacks has especially hurt the Rohingya in Hindu-majority or Buddhist-majority Asian countries, where Islam and terrorism are often considered synonymous.

This underlying prejudice, in addition to historical enmity, may account for Myanmar’s failure to end the persecution of Rohingya Muslims, even during a time of democracy. When Aung San Suu Kyi became state counselor in

2015, the West nurtured the false hope that military action against Rohingya would end. But Aung San Suu Kyi not only turned a blind eye to the 2017 massacre of the Rohingya but also defended the military in the International Court of Justice, claiming that their actions were in reaction to attacks by a Rohingya militant organization. Her response clearly suggests that she is not the human rights icon the West wanted her to be. Not only has she bowed to the military’s pressure regarding the Rohingya crisis, but her word choice suggests that she, too, believes that Rohingya Muslims are “militant” instigators of terrorism.

For a while, Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian government was still, to a limited extent, answerable to the West. But even that small spark of hope for the Rohingyas has been extinguished since the 2021 coup. The current anti-Muslim, militaristic junta, like those before it, judges the Rohingyas’ ambiguous origins harshly and is perfectly happy to use violence to drive the ethnic group into extinction.

“The current anti-Muslim, militaristic junta, like those before it, judges the Rohingyas’ ambiguous origins harshly, and is perfectly happy to use violence to drive the ethnic group into extinction.”

Sanctions on Ice

Antara Singh-Ghai

Fighting Corruption with Corruption

Roni Wine

The Bittersweet Truth

Annika Reff

Bryce Vist

Tanzanian Tourist Trap

Charles Alaimo

A girl of just 15 sobbed on live television while her coach questioned why she hadn’t kept fighting. The silver medalist broke down, repeatedly insisting she would never compete again, while the gold medalist looked despondent on the podium, later describing a feeling of “emptiness inside.” For most Americans, the Olympics are the only time they glimpse the world of international figure skating—and the scene from Beijing this past February did not paint a pretty picture.

Three weeks later, all Russian skaters were banned from international competition due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Although the ban had little to do with figure skating, it has nonetheless proven beneficial to the skating community. It has encouraged a re-evaluation of the sport’s ethics, which had deteriorated under Russia’s control.

she was not able to make up for lost time and ultimately did not make the team. Hat Valieva was able to compete while Calalang was not illustrates the extent of Russian corruption in the skating world: Russians do not seem to be subject to the same set of rules as everyone else.

Beyond the use of banned performance-enhancing substances, several commentators and experts have raised questions about Tutberidze’s training methods. They note the extremely short careers of her skaters and the fact that she often has another star lined up for replacement the moment one begins to falter. “In Moscow, it’s more like a factory of production,” said Rafael Arutyunyan, coach of 2022 Olympic gold medalist Nathan Chen. The teenagers in Tutberidze’s camp, commonly known as “Eteri girls,” have repeatedly spoken out about the club’s mandated public weighins and policy of feeding skaters powdered shakes as opposed to solid food. Russia has implicitly endorsed these exploitative practices for years, warranting disciplinary action from the International Skating Union (ISU), if not an outright ban. Yes, “Eteri girls” win medals, but at what cost?

February’s podium meltdown was the culmination of years of corruption within the world of international figure skating. Leading up to the games, Russia’s Kamila Valieva, the latest teenage prodigy coming out of star coach Eteri Tutberidze’s Sambo 70 skating club in Moscow, was the favorite to win the gold medal in women’s singles. Even after testing positive for banned heart medication shortly before the competition, she was ultimately still allowed to compete, provoking international outrage. Meanwhile, pairs skater Jessica Calalang of the United States was watching from home. Calalang had been suspended for eight months after testing positive for a banned substance, but was cleared to compete prior to the Olympics when it turned out that the positive test was due to a cosmetic product. However,

Tutberidze is not alone among her compatriots in resorting to unethical practices to win. At the 2002 Olympics, Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov, a man considered a key figure in the Russian mafia, fixed the outcome of some figure skating events by coercing judges to favorably score Russian competitors.

“Although the ban had little to do with figure skating, it has nonetheless proven beneficial to the skating community.”

sian government—the government spends millions every year to support its figure skaters. Multiple skaters, including Sotnikova, even organized and attended Putin’s rally in support of the war against Ukraine. But the ban is more than a symbol of opposition to Russia’s invasion—it is also an overdue response to more than 20 years of corruption in judging, doping scandals, and horrific abuse of child athletes by the Russian Federation.

This was neither the first nor the last instance of Russian corruption in judging: In 2014, Russian Adelina Sotnikova, who never won another major title, received the gold medal over skating legend Yuna Kim of Korea in a scandal widely described as one of the most clear cases of biased judging ever seen. The outrage over Sotnikova’s win was so great that the Italian commentator Silva Fontana repeatedly asked why Russia “had to ruin our sport.”

Despite these controversies, it was not until Russia invaded Ukraine that the ISU moved to ban the country from participating in international figure skating competitions. To many, this response was appropriate given the ties between Russian figure skaters and the Rus-

By purging Russia from the sport, even if only temporarily, the ban has transformed women’s skating into a sport for grown and healthy women, not teenagers under immense pressure. The most recent winners of the first four competitions in the Grand Prix series have all been over 20, compared to just one in 2021 and none in 2019. In demonstrating what a healthy and fair vision of skating can look like, the ban also provides an opportunity for the Russian Federation to internally reevaluate whether to continue to allow actors like Tutberidze to dominate the upper echelons of the sport. Ultimately, the ban may serve to protect the sport’s future—both inside and outside of Russia.

“By purging Russia from the sport, even if only temporarily, the ban has transformed women’s skating into a sport for grown and healthy women, not teenagers under immense pressure.”by Roni Wine ‘24, an Economics and International

Public Affairs concentrator

Public Affairs concentrator

“I have only three possible fates: arrest, death or victory. And tell the bastards I’ll never be arrested. Only God can take me from the presidency,” declared former President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro on Independence Day. Dubbed the “Trump of the Tropics” by international media outlets, Bolsonaro uses Messiah as his middle name, openly praises torture, and has proudly expressed his preference for a dead son over a gay one. Despite preaching the importance of “traditional family and moral decency,” he is deeply entangled with political corruption. In 2020, Bolsonaro fired the Director of the Federal Police Maurício Valeixo

for investigating graft accusations against his family. Years later, and the Bolsonaro clan has suffered no consequences for decades of misappropriating public funds for their personal benefit—enough to buy 51 properties in cash.

Bolsonaro’s rise to power can be compared to how a donkey might find itself on top of a tree. In Portuguese, “donkey” translates to “burro,” which also means dumb, stupid, and unintelligent—much like Bolsonaro. His success in climbing Brazil’s political ranks does not reflect his intelligence or tact: As his vice president General Hamilton Mourão once said, Bolsonaro “finished his [military] career at the rank of Captain, the last in which you still use your body more than your brain.” Just as the donkey could not possibly have climbed the tree by himself, Bolsonaro would not be sitting on top of Brazil’s political tree if Brazilian society had not waged a coordinated attack against corruption, wrongly imprisoning Bolsonaro’s primary political opponent. To fight the corruption of the then-ruling Workers’ Party, the country’s judiciary system employed tools that resulted in the erosion of its own democracy.

With Workers’ Party candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s (Lula) victory in the October runoffs of the 2022 Brazilian presidential election, Bolsonaro won’t be sitting on top of the tree for much longer. Lula, a former union leader and two-term (2002-2010) President of Brazil, was once “one of the most popular politicians on Earth” according to Barack Obama. There was good reason for his high favorability: During Lula’s presidency, economic growth rose from 1.9 percent to 5.2 percent and child malnutrition decreased by 46 percent. By the end of his tenure, two massive welfare programs, Fome Zero and Bolsa Família, had taken Brazil off the United Nations’ Hunger Map. The country also made considerable progress in reducing poverty while increasing human capital and facilitating upward social mobility. In addition, Lula greatly expanded Brazil’s commitments to human rights and the environment.

How Brazil’s fight against corruption led to the election of farright Jair Bolsonaro

try’s democracy. It also marked the beginning of the end for the largest anti-corruption operation in the history of Latin America.

Operation Car Wash, or Lava Jato, began four years earlier in 2014 under the command of federal judge Sergio Moro. It investigated the Petrolão bribery network, which included famous politicians and political parties, the construction company Odebrecht, and executives from Petrobras—the country’s stateowned oil company. In 2015, a branch of the Brazilian Federal Police estimated that the Petrolão network paid $2–13 billion in bribes. In Lava Jato’s extensive investigation, officials issued more than 1,000 warrants, spanning across 12 countries. They arrested figures such as Eike Batista (then the richest man in Brazil), President of the National Chamber of Deputies Eduardo Cunha, and, of course, Lula.

Lula’s tenure as president, however, was not corruption-free. During the years it was in power, Lula’s Workers’ Party engaged in what is now called the Mensalão scandal, using public funds to buy legislative support and make monthly payments to congressional legislators. The Mensalão scandal set the stage for the creation of a broader anti-corruption coalition targeting the Workers’ Party and, by extension, Lula. A few months prior to the 2018 election, Lula was charged with corruption, sentenced to nine and a half years in prison, and barred from running for office.

In the years leading up to Lula’s arrest, police officers raided his house and detained him for questioning. Their sole allegation was that Lula and his wife were guilty of “receiving about $1.1 million in improvements and expenses for a beachfront apartment paid for by a large construction company [Odebrecht] seeking public contracts.” Yet, there is no evidence that Lula either owned or lived in the apartment. His arrest represents a gross violation of Brazil’s rule of law and severely weakened the coun-

Judge Moro and lead prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol became celebrities for their work, gracing the covers of newspapers and magazines across the region. In 2018, Moro was the commencement speaker at Notre Dame University and the next year, the Financial Times named him one of the 50 most influential people of the decade. Moro and Dallagnol used their clout to embark on their own political journeys, feeding and being fed by anti-Workers’ Party sentiment. In fact, soon after the 2018 elections, President-elect Bolsonaro—who surfed the massive anti-corruption wave in Brazilian society to win the presidency, or, better, climb the tree—appointed none other than Moro to be his Minister of Justice. No, you did not read that wrong: The judge who put the leading candidate for president behind bars was appointed Minister of Justice by the winner of that election.