THE BSAK ART

By Lucy Gould

Welcome to the fourth edition of our art journal! It is with immense excitement that we present this special issue, centred around one of the most captivating and revolutionary art movements in history: Surrealism.

Surrealism, with its dreamlike imagery and daring subversion of norms, reshaped not only the art world but also how we perceive reality itself. Born from the ashes of war and deeply intertwined with psychological exploration, it challenged conventional thinking, inviting us to delve into the unconscious and question the very fabric of existence. This edition celebrates that bold, boundary-breaking spirit, exploring the many ways Surrealism continues to inspire, provoke, and transform.

Within these pages, you will nd a wealth of diverse and thought-provoking content. We begin with two exclusive interviews with talented BSAK A-Level Art students. For our younger readers and educators, the GCSE student guide o ers practical insights into analysing Surrealist works, perfect for anyone looking to deepen their understanding of this imaginative realm. Meanwhile, the academic essay on Surrealism takes a closer look at the movement’s evolution and its profound cultural in uence, bridging the past and present in a way that is both scholarly and accessible.

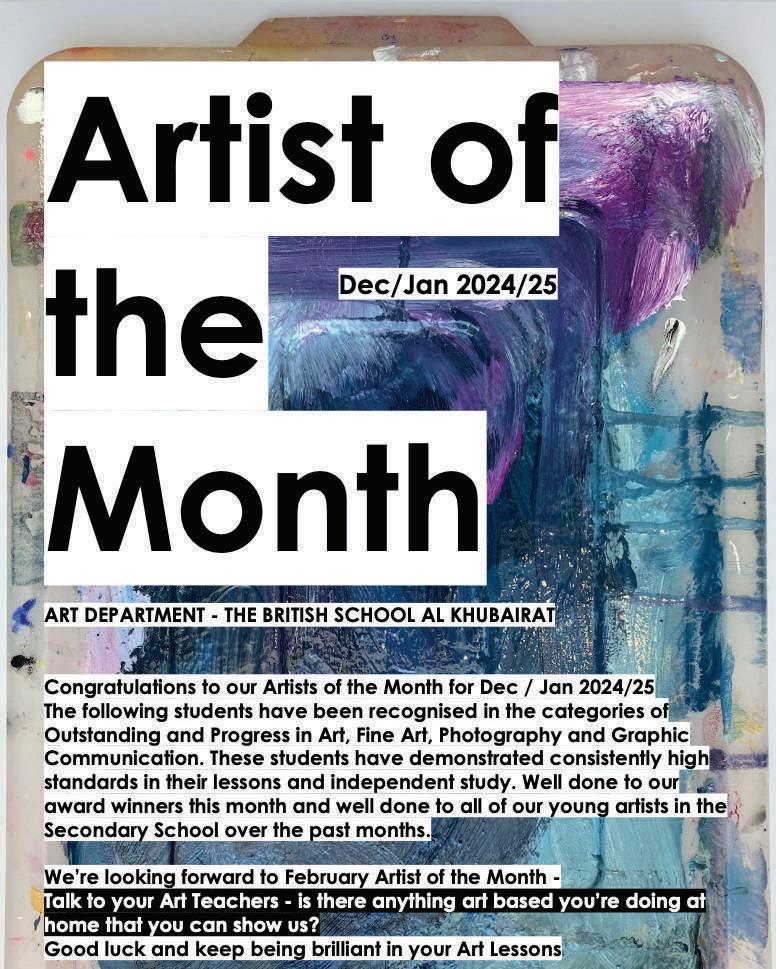

Finally, our "Artist of the Month" initiative shines a spotlight on visionaries whose work echoes Surrealism's daring approach, proving that this movement’s heartbeat is still very much alive.

We hope this edition serves as an invitation to journey into the surreal, where the impossible becomes possible and the ordinary transforms into the extraordinary. Whether you are a seasoned art enthusiast, a curious student, or someone simply drawn to the mystery of Surrealism, there is something here for you to discover and enjoy.

Thank you for joining us in this exploration. As you turn the pages, let your imagination take ight and your sense of reality be deliciously disrupted.

Virtual Dreamscapes: Mariam Basha’s Odyssey of Creation / 3

The Language of the Unconscious: Decoding Surrealism / 5

Surreal Pathways: A-Level Interviews / 7

GCSE Handbook / 9

Artist(s) of the Month / 14

By Bel & Nandana

This interview with Mariam Basha, an A-Level Fine Art student, explores her progression from Graphic Communications at GCSE to a deeper engagement with the broader artistic practices o ered by Fine Art. Mariam re ects on her interest in digital art forms, such as animation and comic art, while expressing a determination to expand her practice beyond digital media. She o ers insights into the challenges and rewards of the A-Level curriculum, shares her sources of inspiration, including contemporary visual culture and narrative art forms, and discusses her ongoing project exploring the relationship between color, emotion, and perception through the medium of interactive storytelling.

What do you like about FA/GC/PH?

I like Fine Art because although I do mostly digital art, I found that Graphic Communication focused more on somewhat commercial-based projects, such as posters, book covers, etc, and I wanted to do something di erent. I originally chose Fine Art instead as I wanted to experiment with more materials and processes. I think I have achieved this, but I still would like to break out of my comfort zone (digital processes) and experiment more as the course continues.

To keep with the theme of this term's journal, what are your thoughts on Surrealism?

I think Surrealism is incredibly interesting. I've always thought that art was far more interesting when depicting something other than realism, because in my personal opinion, as beautiful as realism can be, why depict something we can already see? I like art because of the potential it has. Art has so much opportunity to create something that can't possibly exist in real life, and I think surrealism does that by mixing the idea of irrationality with the real world. And I think that's fantastic. It's not the same, but it reminds me of postmodernism, which doesn't have a set de nition, but is often characterised by hyperreality (a ctionalised/idealised version of reality) and the inclusion of ideas that can't possibly exist in the real world (anti-realism). I think both of these are super interesting to see in art. Art itself is a form of expression, and I love when people use it to express something new, unique, or di erent. Although surrealism isn't something that particularly interests me personally, I do think it's a wonderful movement, and I think surrealist art is so intriguing to witness and explore.

What do you dislike?

I wouldn't say I particularly dislike anything about the subject, but the workload can get stressful, especially since I also take Media Studies, which is similarly coursework/practical work heavy. That being said, I guess I would say tting the mark scheme is what I nd most di cult about the subject, since I sometimes forget to look back and refer to it.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to do this A Level?

Despite me just mentioning tting the mark scheme, my biggest piece of advice would be to not base your project around marks. Do something you are genuinely interested in and actually enjoy. It doesn't matter if you don't think your project really ' ts' the mark scheme, or the start point. Our teachers are super useful in helping us expand our project to get as many marks as we can, and your project doesn't need to link back to the start word/ phrase. I think the best part about FA/GC/PH is that you have almost total freedom with how you move forward with your work. Take advantage of that. If you don't like your project, you're far less likely to want to put in the e ort, anyways. While it is important to think about the mark scheme,I think it's far more important to genuinely like what you're doing.

Where do you go to get inspired?

If I need inspiration from other artists, I tend to look at sites like Pinterest or Behance to see what other artists are doing. Otherwise, I like to listen to music a lot, and I nd that helps me get inspired. I also like to try and get a chance of scenery or perspective, like taking a walk, or trying to think about what I'm doing in a di erent way, or from a di erent person's point of view. I nd taking a break and just relaxing or getting some fresh air tends to help me when I'm feeling stuck or uninspired.

Lorem

ipsum dolor sit

amet, consec-

What are you currently working on?

My current project is about how the saturation/ value of colour can a ect our perception of it, and the emotions we associate with it. I'm doing this through a visual novel. The most well-known example would be Doki Doki Literature Club) that I'm making. In my game, called POLYCHROME, there are four main characters. Val/Valerio (low value), Yue (high value), Sat/Saturn (low saturation), and Ray (high saturation). In POLYCHROME, all four characters, get sucked into a corrupted version of HUEGROUND, an old ash-player game that Sat downloaded on her computer. In HUEGROUND, the world is split into di erent regions that are each made up of only one colour. When travelling through these regions, all four characters take on the colour of the region around them, and their behaviour changes based on the associated emotions with their value/saturation of that respective colour. Some regions allow the player to make choices about how they think the characters are behaving.

How are you nding using the open studios? Is it di erent from using classrooms and the mezzanine?

tetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam n

What’s your favourite theme you've worked on and your favourite outcome from that theme?

I would say that the current project I'm working on is probably my favourite. I like that I'm making a visual novel, as I always found it fun to code visual novels on the software I'm using, but I've just never gotten around to nishing a game, so this one will probably be my rst! I also really like our start point, which was the word 'colour'. It may sound a little juvenile to say, but I've always thought that colour is wonderful, and there's so much you can do with it, especially with how it can be linked to emotion. I've always really liked colour, and had pretty strong associations with colour, so having a project with it as the start point was basically a dream come true for me.

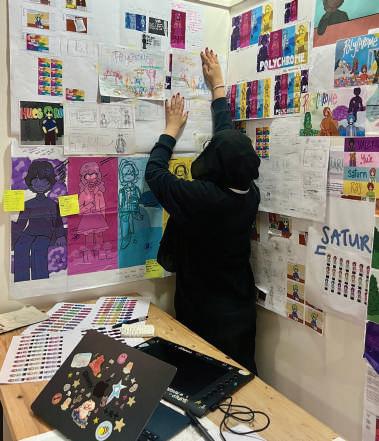

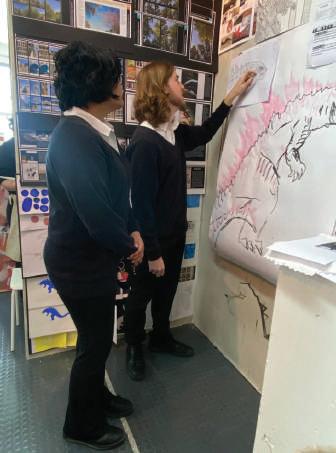

I really like the open studios! They're de nitely di erent from the classrooms and the mezz, but I really like how we get to work with our work around us. It's really helpful for me when I feel the need to check my previous work and I can just turn around and check the walls instead of trying to shu e through my sheets. I do have a metal stool, though, so I will say that it's... far less comfortable than thechairs in the mezz. But I like the open studios, and it de nitely helps me feel proud of my work when I get to see it displayed around me like that. I nd it also helps me feel more inspired, and it's a lot easier to 'get in the zone' this way.

While I don't have a particular favourite artist, fanart and fan artists inspire me a lot. I originally started getting into art through fan art, and I think it's really awesome to see people's own interpretations and takes on a character. I'm also greatly inspired by the Spider-Verse movie series . I just love how they use colour, texture, character design, and just the entire art style. I also love how they link art to the characters. I think it's a really fantastic movie series, and I think it's what really made me consider art as a career path. I'm also quite inspired by music, and I'm a big fan of comics and manga. The Fullmetal Alchemist manga is also a huge inspiration for me, as I really love how Arakawa wrote the characters and world of Fullmetal Alchemist. I think her worldbuilding was fantastic, and all the characters felt so incredibly real. I'm also a big fan of the Cyberpunk Edgerunners show.

Lorem ipsum dol or sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit,

By Lucy Gould

What is reality, and why do we cling so tightly to the idea of it? The 20th century art movement of Surrealism, founded after World War I in France, emerged as a challenge to everything people believed to be “real”. This idea of nding magic in peculiar things seems so fascinating to the human mind and creates this endless world of imagination. Surrealism sought not only to dismantle societal norms and values, but the very concept of existence. Rooted in André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), the movement began as a literary exploration, but quickly extended its in uence into painting, photography and lm, driven by a desire for utopia, rebellion and escapism. The surrealists wanted to go beyond the multiple layers of rationality, logic, and the truth. This made art go where it has never gone before; into the subconscious mind. But was surrealism truly a form of escapism, an act of rebellion, or perhaps a utopic vision of the world? Surrealism delves into the unconscious, exploring how the elements we unknowingly interpret in life in uence our perceptions and experiences. It highlights the ways our dreams and eeting impressions—those moments of déjà vu or inexplicable familiarity—shape our understanding of reality. Are these phenomena mere coincidences, or do they reveal deeper truths about the human mind? This rabbit hole of questioning what reality truly is can seem endless.

One of the most renowned surrealist paintings is Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory [ g. 1]. It re ects the artist’s fascination with time and retains the same themes of the subconscious, fragility and illusion of reality. It is the most iconic surrealist piece, notably since it blurs the boundaries between the tangible and the surreal. Its dreamlike quality invites viewers to question their perception of time, memory and reality. The cool, muted tones of the background juxtapose the surreal forms, lending the composition an eerie tranquillity. Dalí’s precise, almost photographic rendering contrasts with the impossibility of the subject matter, therefore blurring the lines between the tangible and the dreamlike. The melting clocks symbolise the uidity and fragility of time, at large. The distorted self-portrait in the centre—an amorphous, sleeping gure—represents the subconscious, lying dormant but omnipresent. Through this work, Dalí invites viewers to question their perceptions of time, reality, and the boundaries between them.

One example of this was Joan Miró’s Harlequin’s Carnival [ g. 2].

André Breton, heavily in uenced by Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, perceived art as a bridge to the hidden parts of the mind. Surrealism involved the human spirit and he argued for the primacy of dream. Conceived in this manner, surrealism creates a chance for hope and optimism between artists, lmmakers, and writers and the opportunity to remake the world– guratively speaking. Automatism was the surrealist practice of creating without conscious control. It allowed works that were raw and unpredictable to be materialised. Automatism was the surrealist practice of creating without conscious control. It allowed works that were raw and unpredictable to be materialised.

2.

It o ers a vivacious, but nonetheless chaotic window into the surrealist imagination. However, despite its apparent disorder, the painting possesses a rhythmic harmony, with each element seemingly connected in a dreamlike dance.Miró was able to achieve this through an intricate composition that is teeming with fantastical creatures and abstract forms, rendered in a bright, playful palette. Indeed, the harlequin gure, identi able by its diamond-patterned costume, anchors the scene, while the surrounding elements—an anthropomorphic ladder, oating musical notes, and organic shapes—hint at a world governed by the subconscious. This work exempli es surrealism's use of automatism, with Miró allowing his hand to ow freely, unconstrained by conscious thought. The result is a canvas that feels alive, brimming with possibility and inviting viewers to interpret its myriad symbols in their own way. Most surrealist images seem otherworldly, which is exactly the point they are trying to portray. However, pieces like this stand for what the movement is and can be justi ed as true surrealism.

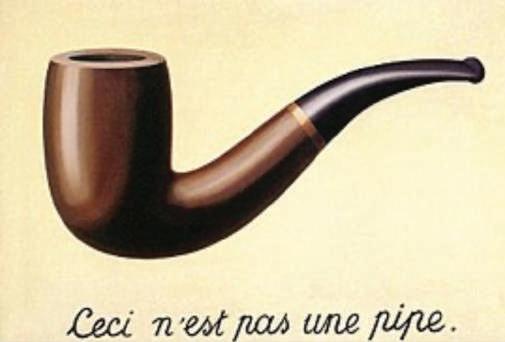

René Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe [ g. 3] is another iconic example of Surrealism’s exploration of reality, language and perception. It purports to display a pipe. And yet, if it was really a pipe, then one would be able to hold it, smoke it, feel its physicality between their ngers. It is therefore merely an image or a representation of a pipe that forces us to confront the gap between objects and their denominations, between reality and our perception of it. René Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe exempli es how surrealism pushes boundaries, urging us to reconsider the assumptions we make about the world around us. By questioning the relationship between language and reality, Magritte challenges us to think critically about how we interpret symbols and the layers of meaning embedded within them. This seemingly simple artwork holds a profound philosophical question: if we cannot trust our senses, what can we trust?

Surrealism did not stop at visual art; its in uence seeped into literature, lm, and theatre. Filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí collaborated on the surrealist short lm Un Chien Andalou [ g. 4], a groundbreaking work that shattered conventional storytelling. Its infamous opening scene—a razor slicing through an eyeball—was deliberately shocking, a visceral attack on the viewer’s expectations. Through disjointed, dreamlike sequences, the lm mirrored the fragmented nature of dreams and the unconscious mind. It rejected linear logic, much like the broader movement itself, which sought to unearth truths hidden beneath surface realities.

In literature, surrealism equally encouraged writers to abandon traditional narrative structures in favour of free association and stream-of-consciousness techniques. This allowed authors such as Breton, Paul Éluard, and Louis Aragon to create works that tapped directly into the subconscious, o ering readers an experience closer to dreaming than to waking life. The surrealist manifesto urged creatives to embrace imagination without constraint, to rediscover a sense of wonder in the bizarre and the unexpected. Ultimately, surrealism’s enduring appeal lies in its power to unsettle, inspire, and liberate. It invites us to question the rigidity of the world we live in, to imagine alternative realities, and to embrace the irrational as a legitimate form of expression. In a world often bound by rules and expectations, surrealism serves as a reminder of the boundless possibilities of human creativity and the profound depths of the human mind. So, what is reality, after all? Perhaps it is nothing more than a collective agreement, a fragile construct waiting to be reimagined. And it is in this reimagination that surrealism nds its truest form—a celebration of the strange, the magical, and the utterly boundless.

By Bel & Nandana

This interview o ers a unique opportunity to delve into the experiences of three Y12 A-Level students pursuing di erent specializations within the Art and Design curriculum—Fine Art, Graphics, and Photography. Leo, who transitioned from Fine Art at GCSE to A-Level, has embraced the greater freedom the subject o ers, allowing him to explore his creativity more independently. Nans, on the other hand, shifted from Fine Art at GCSE to Graphics at A-Level, delving into the commercial and practical aspects of design, while continuing to develop her artistic background. And nally, Easa, who ventured into Photography at A-Level without any prior experience in Art and Design, uncovering innovative ways to express his distinctive vision and explore his creative interests.

The conversation also highlights the pivotal role of the mezzanine space, an exclusive area dedicated to fostering creativity and collaboration among students. More than just a physical environment, the mezzanine serves as a hub for artistic exploration, providing resources and a sense of community that supports students in their creative endeavors. The students’ insights shed light on the signi cance of tailored spaces like the mezzanine, and the varied paths students take in their artistic development.

What do you like about Fine Art/Graphics /Photography as an A-Level student?

Leo: I like that we have more freedom than we do in GCSE, and we get to do what we like, while still being supported by the teachers.

Nans: It’s useful how Graphics can be more business oriented in a way? It’s easier to nd jobs in the future, as there is more demand for graphic designers compared to artists in general.

Easa: Photography helps me explore my interests and daydreams, including weird concepts and peculiar things I like. The subject acts as a catalyst that fuels that energy, aka my interests.

What advice would you give someone who wants to do this A-Level?

Leo: If you like art, do it, but if you struggle with motivation or see it as an infrequent hobby, it might be quite hard as there is lots of work given.

Nans: If you didn’t do Graphics at GCSE, it might be worthwhile to do a few courses or invest in some graphics books, which helped me a lot to get the fundamentals down.

Easa: Understand how cameras work beforehand. Just developing a basic understanding and working on those skills is incredibly important and useful, as you can spend more time working practically. When working, do something you enjoy, focusing on themes that interest you.

Who or what are your biggest inspirations?

Leo: Godzilla, Jurassic Park, sci- things like Avatar, specevo projects, wildlife documentaries, zoos, animal keeping and nature, the internet, lms, series, games, music/soundtracks.

Nans: Seeing other people being passionate about things/their art, my friends/ people around me, various Japanese artists, games, nature, my obscure music taste.

Easa: Artists I nd on Instagram, especially those who create stylised photoshoots where they really amplify the features of their models.

How are you nding using the mezzanine space? Is it any di erent from the classrooms?

Leo: The mezz is much better than the classrooms, it's smaller and more compact, which kind of reduces the echo, and it's a place away from everyone else. It's better than the library, because I can have all my stu spread out and do not have to worry about spilling paint or something like that. You can also see where everyone is sitting and have better interactions with each other.

Nans: I really like coming up here whenever I have the time, it’s quiet but not too quiet, and the fact that no one else can come up here is really comforting as I know I have a room to myself where i can spread all my supplies and ideas out, creating a visual representation of my artistic process while working.

Easa: Although it’s a bit isolating, I prefer it to the classrooms. I know everyone who’s in here and can ask them questions whenever needed.

Where do you go to get inspired?

Leo: Around my house, as I keep a lot of animals, and if I have the money, zoos and aquariums. Nans: Libraries, museums and anywhere near nature. I get inspiration at random times and always keep a mini sketchbook with me. I like Pinterest as well.

Easa: My own room, in the middle of a shower, right before bed, any time I’m not supposed to be inspired.

By Bel & Lucy

Passion plays a primordial role in the art subjects. Without it, one may not enjoy the course and essentially lack the motivation to engage with the work. This principle does not merely apply to photogra- phy, but extends to all subjects. However, there will always be subjects you may not enjoy but feel particularly compelled to pursue. For me personally, GCSE photography was never one of those. On the contrary, it was one of the few subjects I genuinely enjoyed and eagerly looked forward to, devoting my time to willingly. Ultimately, if you have a love for taking photos and a keen interest in annotating and analysing photography, then you’re well set for success in the subject.

If you have always found the subject and its processes intriguing, such as being fascinated by taking photos or understanding how cameras work, then this course will likely resonate deeply with you. As a child, if you often played the role of a photographer or found joy in capturing moments, GCSE Pho- tography will feel like a natural extension of your interests. Personally, I have loved cinema and pho- tography from a young age, captivated by how movies are made and the intricate details that go into creating impactful photographs. If you share a similar passion and curiosity, you are bound to enjoy and excel in this subject.

I think Photography is slightly more subjective than Fine art or Graphics. And yet, I found that if you stayed on top of the workload and took one shoot or research one artist at a time, then it really helps then to look at a whole theme and think “I’ve got to do this, this and this” by the end of the week. This is, of course, easier said than done because at A-level, I usually feel really overwhelmed by the course workload. However, what I have discovered recently that has helped is following a routine and making lists. While this approach might not work for everyone, it has been bene cial for me. By organizing tasks from most to least important, I can set realistic deadlines and stay on track. Over time, I've learned the importance of nding a working method that suits me, much like discovering the study techniques that work best for you.

Looking at the success criterias is essential, or at least I feel they are as they help me create guidelines for myself and see where I want to be and where I am. At GCSE, words like innovative, unique, under- standing, imaginative and experimental. Going outside your comfort zone and pushing yourself is what makes your photography di erent to everyone else's. This does not mean you cannot explore things you love and are interested in, because that means you are passionate about it and will likely spend more time on it.

The main principles of photography are concepts like lighting, focus points, composition rules and also interpreting and understanding the visual art elements. If this and using a camera in general fascinate you, then I think you’ll be set for photography and remember you’re always learning along the way, it’s a project, not a test, and you can go back and re ne things.

Remember, photography is not just about taking pictures; it is about telling a story, creating themes in your perspective and sharing your own personal meaning of things. At GCSE level, you will gradually start to develop your own creative style. This of course does not happen overnight, so do not worry if your early shoots feel a bit uninspired or uncertain. Experimentation is key and documenting this is even more important. You have to document the good and the bad, to show your journey and your progress through the course. Instead of looking at a bad shoot and xating on it, constructively criticise your own work and look beyond that shoot. Think “what can I do better?”, “What went wrong?” and “how can I change that?”

One thing that really helped me was keeping a visual diary. This does not have to be perfect—it is merely a space to jot down ideas, sketch layouts, or even paste in inspiration like magazine cutouts or quotes. Over time, you will start to see patterns and themes emerging that re ect your own unique perspective. This is your creative ngerprint, and it is something you will keep developing throughout the course.

Always remember that your teachers will always be there for you, they are the experts and have taught many students through this course over the course of their careers. Do not, therefore, be afraid to ask for help and use other sources. Also do not be afraid to try di erent things - use unusual angles, play with lighting and make mistakes. Sometimes the most unexpected results can lead to your best work.

When I started to do GCSE Fine Art, I initially found the workload particularly overwhelming. As soon as I got into GCSE coursework I found the expectation of having to ll in 3 A3 sketchbook pages that all needed to be completed at the end of the week daunting and I often found myself swamped with tasks.

To manage my workload e ectively, I developed a routine. After school, I prioritised working on my art projects during the best natural light of the day, completing as much as possible before evening. This strategy not only improved my e ciency but also helped me achieve better results.

Sustaining focus for extended periods was another challenge. To overcome this, I adopted a system of alternating between work and breaks. Tackling tasks in smaller intervals allowed me to stay motivated, feel less burnt out, and maintain the quality of my work. I was much happier with the outcomes when adopting this method.

I also remember how I used to be given a substantial amount of homework assignments to be completed in my sketchbooks. I managed to overcome this dilemma by making it a point to start the work on the same day it was assigned. This approach kept my focus sharp and my thought process more relaxed. It also prevented the buildup of un nished tasks, which I observed caused signi cant stress for some of my classmates as deadlines approached. Leaving many having to spend more time later in the year having to catch up with work instead of trying to complete their current work ready for the exam. I felt this was very stressful and it spilled into our lessons and was detrimental to those of us who had done the required work. By keeping up with the workload, I avoided the pressure of last-minute catch-up and was able to concentrate fully on my nal project.

One of the key foundations of Fine Art, both at GCSE and A-Level, is the understanding and application of the following seven formal elements; Shape, Line, Space, Form, Texture, Value and colour. These elements serve as essential guidelines, helping students re ne their skills and deepen their understanding of the creative process.

The thing I always love about Fine art is its limitless potential for artistic expression. Otherwise said, the fact that you can create many masterpieces visually in di erent ways and forms. Fine art does not simply encompass drawing but also painting, sculpting, digital art and even some photography. Each medium o ers unique opportunities to explore and innovate, and GCSE Fine Art provides an excellent foundation for honing these skills.

For those embarking on their GCSE Fine Art journey, generating ideas can be a deeply rewarding pro- cess if approached with the right mindset. Begin to brainstorm ideas and think of it more as creative play instead of work, and try to eliminate distractions, such as phones, by nding a quiet place where a clear desk creates a clear mind. Create your own rules, build on your mistakes, and always experiment; then revise, rework, and rethink your approach. Additionally, try to make a creative atmosphere that challenges your learning and exploration, while experimenting with di erent mediums to nd your innovation process. It is also important to celebrate your failures as much as your successes, as this will challenge your learning and foster growth. Most importantly, keep all your work that you create and do not be tempted to throw anything away, as sometimes you can use it as a reference or later incorporate it into your coursework to show your evolution and journey. Finally, feedback from friends and teachers may also prove helpful, as it sometimes brings a di erent perspective, which can be invaluable.

Fine Art has always meant a great deal to me even from a small age, stemming from an instinctive urge to create. Despite the workload and the countless hours invested, the process of making and designing has always brought me immense pleasure. If you are feeling on the fence about whether Fine Art is a good choice, then just remember that if you enjoy spending time making something new or unusual then this may be your journey. Share your work regularly with your teachers to make sure you are staying on track for the work you must complete.

Awarded for progress in Art and continued commitment to personal creative development.

Year 10 Year 10 Year 11

Year 11

Year 12

Awarded for consistent outstanding artwork, creative practice and continued commitment to personal creative development.

Year 7 Year 9 Year 8

Year 10 Year 10 Year 11 Year 12

A very special thanks to all those who made this publication feasible

Art Ambassadors:

Bel Cebisli

Lucy Gould

Nadine Helal

Nandana Krishnakumar

Zoe Van Dyk

Art Department:

Dan Emery

Monica Zakka

Thomas Smith

Jayne Newsam