Nikhil Rich Playing Out: Harmonic Freedom in Jazz Fusion Improvisation

Senior Thesis | 2024

Nikhil Rich

Table of Contents

Preface

1. The Theoretic-Historical Background of Jazz Fusion

2. Theoretical Preliminaries

3. Chick Corea on “Return to Forever”

4. Chick Corea on “Raju”

5. Herbie Hancock on “Sansho Shima”

6. Brad Mehldau on “Vou Correndo Te Encontrar / Racecar”

7. Conclusions for Practice

Analyzing improvisation is a unique challenge because unlike analyzing a score, it is not always obvious how to explain what happens, and whether or not the explanation is sound. Improvisation could mean arbitrary decision making, in which case analysis of these improvisations would not be particularly fruitful. What would be the purpose of analyzing a piece of improvisation if the musician herself was unaware of what she was doing? The truth is, however, that this is not typically the case in jazz. In a 1985 talk at Berklee College of Music, Chick Corea gave out a sheet of paper dictating his advice for young musicians. In the list, he reminds the musicians repeatedly to always play with a purpose: “Play only what you hear. If you don’t hear anything, don’t play anything. Don’t let your fingers and limbs wander – place them intentionally.”1 While it is certainly always possible that an

1 James Travis Spartz, “Chick Corea’s Cheap but Good Advice for Playing Music in a Group,” Medium, December 17, 2019,

improviser acts randomly, it is not accepted or encouraged within jazz for her to do so. It is for this reason that a piece of jazz improvisation must be given the same amount of credit as a piece of composed music.

The next difficulty in analyzing jazz improvisation is in applying theoretical concepts to improvisations which could have been made without any intentional use of these notions. If a skilled jazz improviser plays only by ear, then they would certainly not be considering what scale they are using, what arpeggios they are playing, and so on. This is where it becomes important to note that all music theory is necessarily descriptive rather than prescriptive – meaning that it exists only to describe what is, rather than explain how things should be. Consider a musician who plays a C, E♭, G, and B♭ in quick succession. Regardless of whether she made an intentional effort to arpeggiate a C-7 chord, it is https://jtspartz.medium.com/chick-coreas-cheap-but-good-advice-for-playingmusic-in-a-group-b9b52b49a96e.

nonetheless what she has done. The theoretical notion of a C-7 exists simply because we have defined its existence ourselves, and thus to say that the musician arpeggiated a C-7 is an analytic. We do not know why she did so, nor do we need to. It is sufficient for analysis simply to state what she has done. This paper will attempt not only to explain what a given musician played while improvising, but why what they played works. In attempting to do so, I notice many of these aforementioned analytics. It is impossible to know with certainty whether or not these interpretations are in line with what the improviser was hearing, but it does not matter. The following analysis is entirely based upon observations about what is. By finding patterns in what is, perhaps we can better understand why it appeals to us and learn how to replicate it ourselves.

Since its inception in the late 1960s, jazz fusion has always been a point of controversy amongst musicians and critics. Some

musicians from the bebop tradition found it to be a capitulation to the demands of the market, seeing it as a break from the essence of jazz. Notorious jazz aristocrat Wynton Marsalis claimed that fusion originated because “jazz musicians saw it as their duty to try to embrace amateur musicianship to be a part of the popular trend.”2 To those who are familiar with the style, this claim is completely absurd. The contents of this paper will include numerous examples of technically intricate improvisations which prove this claim false. However, one element of his claim is correct, viz., that jazz fusion was commercially successful. Herbie Hancock’s seminal fusion album Headhunters, for example, spent 47 weeks on the Billboard top 200, peaking at 13.3 Albums like Romantic Warrior and Heavy Weather, by Return to Forever and Weather Report respectively, soared to the top of the jazz charts

2 Joy2Learn, “Wynton Marsalis | History of Jazz - Fusion,” YouTube Video, 0:51, July 8th, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TA0KrHDy4L4.

3 “Herbie Hancock: Biography, Music & News,” Billboard, accessed April 11, 2024, https://www.billboard.com/artist/herbie-hancock/chart-history/tlp/.

whilst maintaining relative success in the mainstream.4 What is so impressive about fusion is that it was able to garner great commercial success despite the musicians having such a different skill set than those who they were competing with. Corea, Hancock, McLaughlin, Shorter, and countless others were able to sell large amounts of records whilst subliminally imbuing their music with sounds from free jazz, post-bop, and the avant-garde.

For the purposes of this paper, jazz fusion refers to the style which emerged when jazz musicians from the 1960s electrified their sound, beginning to incorporate funk, rock, soul, and electronics in their music. While fusion was commercially successful, the style finds its origins in much less accessible music. Many of the most significant jazz fusion musicians of the 1970s came to prominence while working with Miles Davis, and many of them began experimenting with fusion on albums of his such as

4 “Romantic Warrior - Return to Forever: Album,” AllMusic, accessed April 11, 2024, https://www.allmusic.com/album/romantic-warriormw0000188588#awards.

B**ches Brew. This is difficult music, with song lengths north of 20 minutes and influence from Ornette Coleman’s free jazz methodology.5 However, it contained many of the same musicians who would later enjoy the aforementioned commercial success of fusion, such as Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul, and John McLaughlin.

This paper will use two books to gain an understanding of jazz theory. The first is Postbop Jazz in the 1960s by Keith Waters, a book which examines many of the earlier compositions of notable fusion musicians from before their fusion eras. By understanding where these musicians came from, it becomes clear what they would grow into, as Waters says, “undoubtedly some postbop strategies were retained by Shorter, Hancock, and Corea in their jazz-rock [...] fusion work of the 1970s.”6 The next book is A Chromatic Approach to Jazz Harmony and Melody by jazz

5 “Bitches Brew,” Miles Davis Official Site, June 23, 2023, https://www.milesdavis.com/albums/bitches-brew/. 6 Keith Waters, Postbop Jazz in the 1960s,

saxophonist Dave Liebman. Liebman has worked in many different styles of jazz, focusing most particularly on avant-garde jazz. However, early in his career he was at the forefront of the fusion movement during his time with Miles Davis. His earliest albums, such as Lookout Farm, Drum Ode, and Sweet Hands, are also composed within the fusion idiom. In A Chromatic Approach, Liebman explains how to expand, confound, or even abandon tonality in composition or improvisation. This is particularly useful because of its applications to improvisations which stray far from the original tonal center.

When analyzing the harmonic content of a given line it is sometimes useful to describe certain passages with “tonal anchors.” While the performer may be improvising in one key, a tonal anchor can be a temporary moment away from this center. Liebman describes the tonal anchor, saying, “tonality is flexible and in continuous flux as a line evolves… [tonal anchors] may

result from several musical developments: the emphasis of one pitch or pitch cluster, leading tone activity (half or whole step pull), rhythmical stress on a pitch, or how the intervallic shape seems to lead to a tonal center.”7 Liebman explains that using tonal anchors allows the improviser to mystify the original key center, thus allowing them to return to the original key with more clarity.

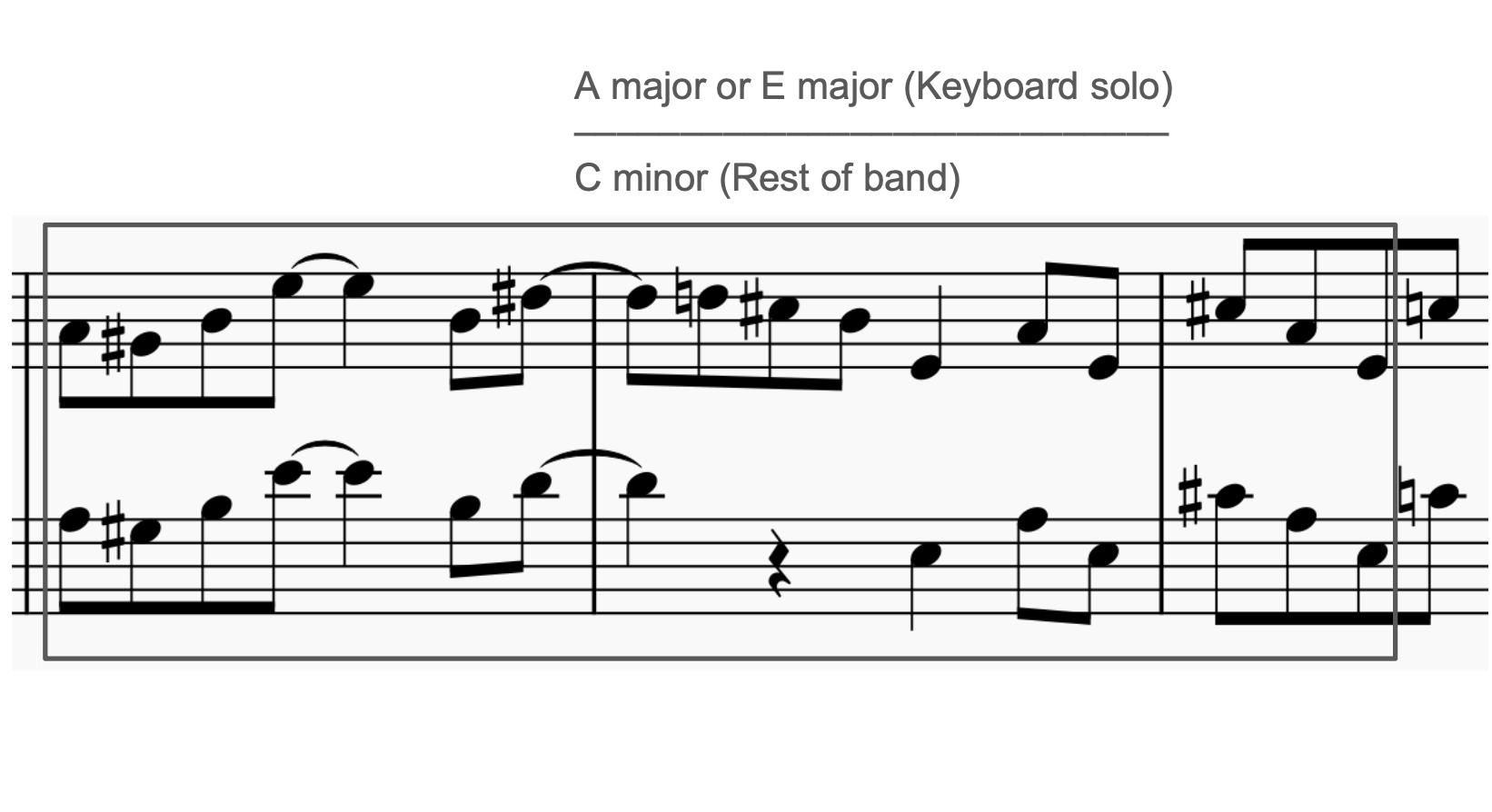

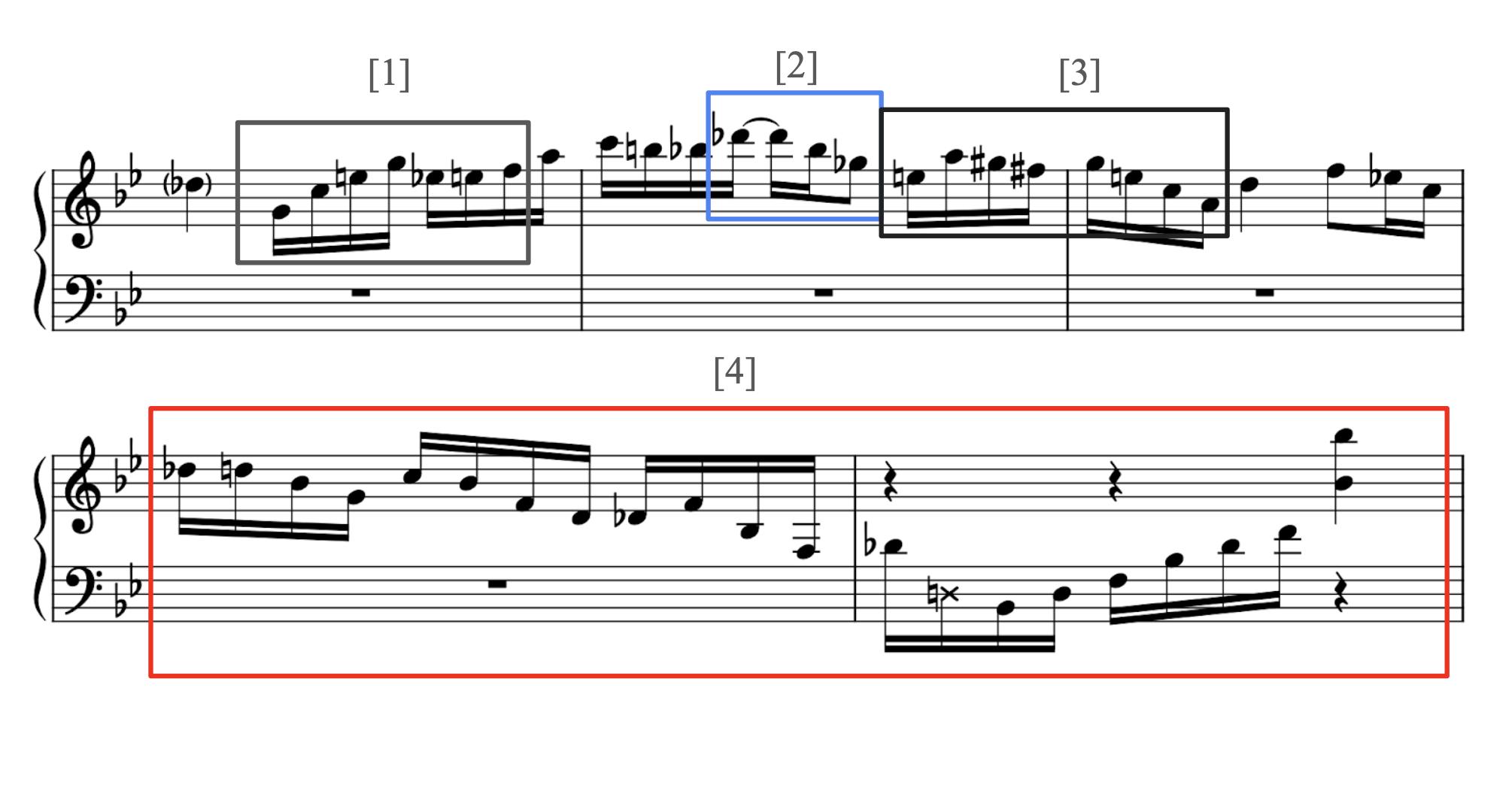

By analyzing the improvisations always in relation to the primary tonal center, there arises an “error” factor which can even be numerically quantified using the circle of fifths. For example, while tonal anchors in a vacuum show how an improviser moves between key centers, by comparing the harmony to the basis, we can quantify how far “out” this tonal anchor is from the expected tonal center. Take, for instance, the passage from Chick Corea’s “Return to Forever” that shall be analyzed later (Figure 2.1).

7 Liebman, A Chromatic Approach, 55.

Figure 2.1: A passage of Chick Corea on “Return to Forever.” This analysis yields polytonal textures that heavily clash with each other and are typically compositionally used in much more tense situations. While writing on polytonality, Vincent Persichetti says, “The resonance of polytonality depends upon the resonance of the over-all tonic formation as determined by its intervallic tension. The passing secondary textures are maneuvered around the most

resonant polychords that form the structural pillars of the particular key combination.”8 Perischetti emphasizes in the text that some examples of polytonality are more dissonant than others. However, by considering “resonance,” composers can mitigate some of the difficulties which might arise from this dissonance. In this case, the most notable and clear case of polytonality is the A major segment which Corea plays, contrasting heavily with the standard harmony in C minor. However, just as a composer can take advantage of the resonance properties of the scales they are combining, Corea can also manipulate the listener into not hearing the polytonality as exclusively dissonant by using strategies that shall be discussed later.

Polytonality is perhaps the most obvious form of chromaticism found in jazz fusion. In figure 1.1, for instance, Corea’s melodic figure, while non-diatonic, is clearly in either A 8 Persichetti, “20th Century Harmony,” 258.

major or E major. However, other instances occur where a pitchclass set does not fall within any diatonic set. In these cases, polytonality is an insufficient means of understanding the harmonic content of the phrase. This is why another approach is required – an approach which assumes that a given pitch-class set is not diatonic to any key. Another issue arises when discussing how this new method will capture the effect which a given pitchclass set has on the music. Naturally, there are many such nondiatonic pc-sets. While an instance of polytonality can be understood on a continuum ranging from the least to greatest dissonance, we must formulate a new way to describe these new pc-sets.

The following exposition serves to rigorously and abstractly define the concept of an upper bound in association with a chord with any number of distinct pitches and will explain how this concept is applicable to our analysis. First, the upper bound must be defined: “A set S of real numbers is bounded above if

there is a real number b such that x ≤ b whenever x ∈ S. In this case, b is an upper bound of S.”9 To apply this in a musical context, consider the chromatic scale starting on C3 and ending on B3. In this case, B3 is an upper bound, but it is also the least upper bound, which is called the supremum. In the twelve-tone equal temperament system, a minimal upper bound shall be defined to be any upper bound less than 11. The reason for this is that any pitchclass (pc) set, ", with an upper bound less than 11 will be a subset of the chromatic pc-set, C, such that card(") < card(C). The term chord simply refers to the simultaneous occurrence of more than one distinct pitch-class, and so an n-chord is used simply for an abstract representation of a chord with n distinct pitch-classes. Our study will concern itself mostly with trichords with an upper bound of 4. To put this statement formally, we will observe the following pitch-class sets: {0, & , ' | 1 ≤ & < ' ≤ 4}.

9 Trench, “Introduction to Real Analysis,” 3.

It immediately becomes necessary to consider how many of these such sets truly exist. The answer to this is clearly 4 /ℎ1123 2 = 6.

The six pc-sets in question are as follows:

1. [012]

2. [013]

3. [014]

4. [023]

5. [024]

6. [034]

The pc-sets which occur in the diatonic scale are not presently of relevance, therefore, they should be deleted. This leads to a new set:

(1) [012] → “Chromatic” (2) [014] → “Modal” (3) [034] → “Blues”

This is the complete set of non-diatonic trichords with upper bound of 4 (ND3C-UB4).10 The adjectives associated with each are meant to convey some of their sonic essence; (1) is called chromatic because it forms the first three pitches of the chromatic scale, but

10 Abstractly, a non-diatonic n-chord with upper bound m is called ND(n)CUB(m)

(2) and (3) require more explanation. (2) is called “modal” because of its appearance in non-diatonic modes throughout the world. In the west, it is found in the Phrygian dominant scale, which is a mode of the harmonic minor scale. In Hindustani classical music, it is found in Raag Bhairav, amongst others. The leap from pc 1 to pc 4 is characteristically non-diatonic, for there is no augmented second in the diatonic scale. The third and final element is a common occurrence in blues-influenced music; in order to simulate voice or guitar, which can bend between the major and minor thirds, a musician may accentuate both the major and minor thirds in relation to the tonic. In the case of the minor blues, this often manifests in the simultaneity of perfect and diminished fifths (pc-set = [0367] = [0]⋃T3[034]). It is important to note that (2) and (3) need not be used to evoke these musical traditions. The reason they are applicable here is that both musical traditions were influential to jazz in the 1970s.

At first, the decision to consider only ND3C-UB4 may seem arbitrary. It is not obvious why this particular set of chords is more pertinent than a set with a different upper bound or chord size. However, after some inspection, it becomes clear that this is the best choice given the circumstances. An upper bound of less than four implies each n-chord would have at most three elements, and because ND(i)C-UB(i) is at most singleton for all i, it is useless to consider ND3C-UB3. Therefore, consider the set ND2CUB3. This set is not singleton, but rather an empty set, for it is impossible for a dyad to be non-diatonic.11 Therefore, a trichord is the chord with the least notes which can be non-diatonic.

Additionally, it is useless to consider ND3C-UB(5∨6), for this adds no new elements to consider compared to ND3C-UB4. Using an upper bound greater than 6 would often lead to transpositional equivalencies which make the set more difficult to narrow down.

11 The interval vector for the diatonic pc-set is <254361>. A dyad is equivalent to an interval of any kind. Because there is no 0 in the interval vector, there is no non-diatonic interval.

There now arises the question of why to use trichords rather than tetrachords, pentachords, etc. Trichords are the logical choice because every non-diatonic chord with more than three pitchclasses contains a non-diatonic trichord. This is evident by the fact that a tetrachord is equivalent to the union of every possible subtrichord and is diatonic if and only if every sub-trichord is diatonic. Therefore, a tetrachord being non-diatonic necessitates that it has a non-diatonic sub-trichord. The same process applies for larger and larger chords.

With this in mind, small non-diatonic pc-sets can be described with much greater ease than before. Going forward, (2) and (3) shall be abbreviated to C2 and C3. Their union, [0134], shall be called C2-3. Note that C2-3⋃T6(C2-3) forms the halfwhole octatonic scale, a musical concept which shall become of utmost importance later on in the analyses. C2⋃T1(C3) is another useful set to consider, but instead of the octatonic scale, this set

plays an important role in the harmonic minor scale. It shall be denoted C2-31.

Chick Corea was born in 1941 and grew up in Chelsea Massachusetts. Being the son of a Dixieland trumpet player, he grew up around music from birth. Before he was at the forefront of the jazz fusion movement, he was gigging with Mongo Santamaria and Stan Getz. This certainly helps explain his interest in AfroCuban and Brazilian music, both of which were heavily influential in his later work. He began working with Miles Davis in the late 1960s, which would be the environment in which he began experimenting with the electric piano. One of the most important albums in the early history of jazz fusion was undoubtedly In a Silent Way. The album featured a lineup of Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, John McLaughlin, Dave Holland, Tony Williams, Joe Zawinul, Herbie Hancock, and Chick Corea. All these musicians are essential figures in the history of fusion. Besides Davis, Shorter

and Zawinul would work together on Weather Report, while Williams and McLaughlin collaborated in the group Lifetime before the guitarist left to form Mahavishnu Orchestra. Holland recorded with fusion greats such as Miles Davis and Joe Henderson for quite some time, but he found his sound in his free jazz work with artists such as Chick Corea and Anthony Braxton.

After leaving Davis’ band, Corea began his solo career to great success. In 1972, he recorded the eponymous first album with his new band Return to Forever. The album includes Airto Moreira on drums, Flora Purim on vocals, Joe Farrell on soprano saxophone and flute, and Stanley Clarke on bass. Corea plays a Fender Rhodes electric piano throughout the whole record. Moreira and Purim are both Brazilian musicians who grew up playing Bossa Nova. The album features a mix of Latin music with the already established electric jazz style, but it wasn’t until his later work with Return to Forever that Corea expanded into rock.

From the beginning of his work as a fusion bandleader, Corea was already displaying the refined abandon that would define his later work. From the album Return to Forever, “Return to Forever” features a long electric piano solo which stays mostly diatonic or modal, but ventures outside of expected parameters at a few notable points. One prominent passage begins at 8:06 in the recording and features numerous different strategies for playing outside of the tonality (Figure 3.1).

This portion of the recording is a C minor vamp, and Corea sets up this out phrase with a lengthy series of “in” phrases. In segment 1, he plays a C minor arpeggio in second inversion, but immediately abandons diatonic harmony with the following E and F♯. While the C minor arpeggio leading into the E♮ (C3) implies blues harmony, the following F♯ and G indicates that this run could be an octatonic collection, as described by Keith Waters. This is evident by the fact that the E♭, E, F♯, and G form a transposition of C2-3.

Segment 2, however, differs slightly in that it begins with a B♮. B♮ is not within the octatonic scale in question, meaning that this segment is a departure from the prior pitch set (if it is accepted that the end of segment 1 implies an octatonic collection). Instead, he plays T6(C2-31) followed by T4(C2-31). Thus, Corea takes the same non-diatonic pc-set and transposes it down a major second in order to create some familiarity amidst the harmonic dissonance.

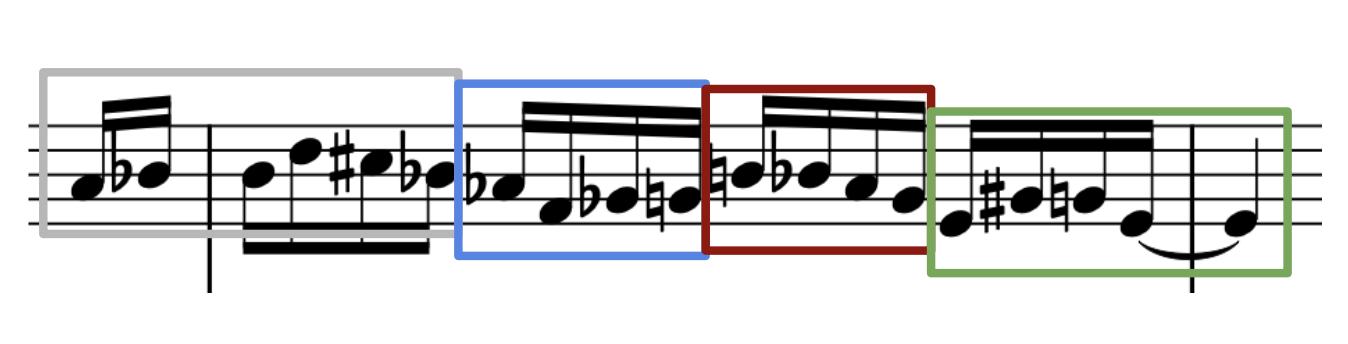

Segment 3 moves thoroughly into the vocabulary of the blues, as

shown by the presence of the diminished fifth used in conjunction with the minor third, as well as the mixture between the major and minor thirds (C3). Segment 4 is a descending A major scale leading into a first inversion E major arpeggio, implying some form of diatonic A major or E mixolydian harmony. In segment 5, for the first time in the passage, Corea’s hands are in polyphony rather than monophony, as he plays the dissonance of D to D♯. It is hard to tell whether or not this is a mistake, as the whole passage leading up to it is in monophony and there was little precedent before this point for a prime dissonance. If it was a mistake, then Corea likely intended to play a D♮ in the right hand to continue the A major tonal slipstream. He continues by playing an excerpt from an A major scale, followed by an A major arpeggio in second inversion. In segment 8, he plays from C minor and is back to the original tonal center.

Throughout this passage, Corea uses a variety of techniques to approach chromaticism. Foremost, he transposes a given pc-set

such that it implies harmony from a distant key center. The A major diatonic harmony in the latter half of the phrase is clearly an instance of polytonality. However, perhaps most distinctive is how he uses blues vocabulary to enter these phrases. In segment 1, he takes advantage of the simultaneity of the major and minor third in the blues and uses that as a way of drawing a comparison between the blues and the octatonic scale. The half-whole diminished scale has this same ambiguity. Therefore, by beginning with a blues phrase, it is easy for him to transition into an octatonic phrase. In a similar manner, he uses a three-note chromatic run to transition from C2-31 to C blues. This time, however, he utilizes both minor blues and major blues harmony, as he plays on the duality between the perfect and diminished fifths before returning to the majorminor third duality.

Raju is a composition by guitarist John McLaughlin written originally for his 2008 album Floating Point. The form is a

modified E blues with a secondary section that involves a shift in the tonal color, as the harmony moves from E blues to C♯ minor. It was not until the 2009 album Five Peace Band Live that Corea would take the solo that shall be analyzed. The album features Corea, McLaughlin, Kenny Garret, Christian McBride, and Vinnie Colaiuta. It also brings Herbie Hancock on for a rendition of “In a Silent Way.” For Corea, Hancock, and McLaughlin, this is a reunion from the original 1968 recording. Because of this, the live album almost acts as a time-capsule for early jazz fusion.

Corea begins his solo with a simple transition from the harmony of the tonic, E blues, to the temporary tonal center of C♯ minor. After playing a simple descending figure in E minor, he gives the listener the first harmonic surprise. After three beats of rest, Corea plays the following line (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1: A passage from Corea’s solo on Five Peace Band (in treble clef).

In the key of E minor, this line contains only two notes which are non-diatonic. These notes are A♯ and D♯. The D♯ is the leading tone of E, borrowed from E major to form the harmonic minor scale. By using the C♮, as well as following the D♯ with an E-7 arpeggio, Corea implies that the D♯ is meant to be a leading tone into E♮. There are multiple potential interpretations of the significance of A♯. In the harmonic setting of the blues, the augmented fourth or diminished fifth carries a great deal of significance as an essential color, or blue note. However, it could also represent a similar phenomenon to what occurs with the D♯, where it could be chromatically connected to the B. Also note the

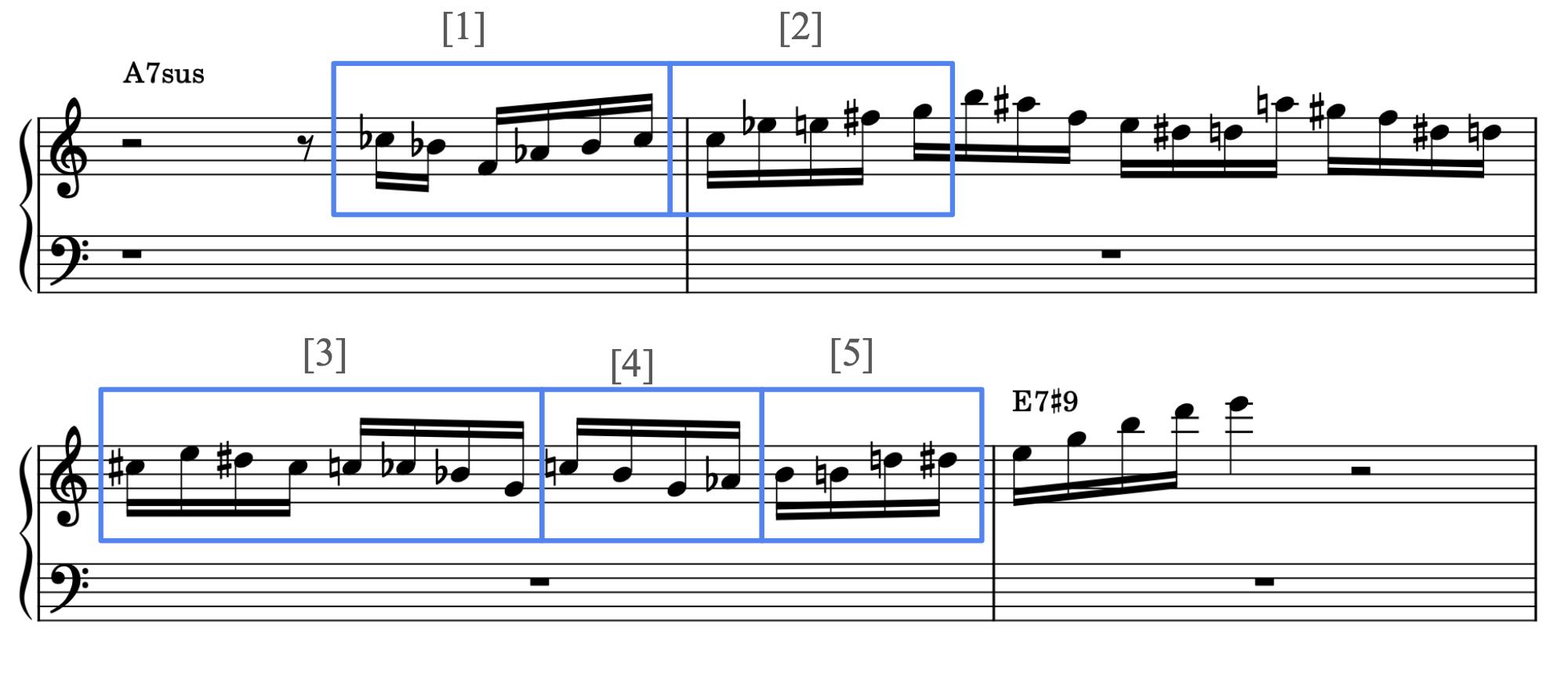

presence of T11(C2-31), as well as T7(C3). Corea then creates a chromatic color using both hands to form a long, flowing sea of sound, spanning almost 5 measures with continuous 16th notes. After this, the groove becomes more pronounced as Corea starts to play with more conviction. The first four measures represent typical E blues harmony, with usage of both the major third and flat seventh to indicate a mixolydian sound. Corea follows this phrase with his first truly chromatic line (Figure 4.2).

Breaking the phrase up into four parts, each can be understood as using a slightly different strategy. Segment 1 employs harmony reminiscent of B harmonic minor. Understood in the context of the tonic E, this implies an E dorian ♯4 modality. The A♮ at the beginning of the phrase could also imply that the A♯ is simply a chromatic note meant to point to B. The second segment is a purely chromatic scale. The third segment implies a minor blues harmony while the fourth segment implies major blues. This is due to the use of the diminished fifth in combination with the minor third in segment 3, while segment 4 contains the duality between the major and minor third.

Figure 4.3: A passage from Corea’s solo on Five Peace Band (in treble clef).

In this passage, Corea employs a much more standard and predictable strategy for playing outside of the key. He starts by simply playing a fragment of the melody starting on B♮, then repeating it down a half step on B♭. In the third measure, he plays a slightly modified version of the phrase starting on F. While the first and second repetitions have a forte number of 4-26, the final iteration is 4-23; while a D♭ is expected, an E♭ is present instead. This difference could have been a mistake; however, it is more likely that Corea intentionally modified the pc-set for the sake of variation.

Figure 4.4: A passage from Corea’s solo on Five Peace Band (in treble clef).

Segment 1 is a clear instance of F minor blues vocabulary while the tonality is E blues, and the chord is an A7sus4. Segment 2 is an octatonic collection from the C half-whole diminished scale. [3] is almost entirely an octatonic collection, viz., G whole-half diminished; however, the C♭is the one pitch which does not belong in the set. [4] is T7(C2-31) and [5] is T11(C2-31). All these small fragments of the phrase make sense as instances of non-diatonic improvisation on their own, but the impressiveness also lies in how

Corea fluidly moves from one dissonant moment to the next, all while making it sound smooth.

Figure 4.5: A passage from Corea’s solo on Five Peace Band (in treble clef).

Corea returns to the previously discussed theme in 4.5.1 by utilizing the Dorian ♯4 modality as heard at the beginning of the solo. Observe how 4.5.2 observes a binary form in terms of its harmonic content: the orange highlighted passages are T11(C2-3), whereas the gray-boxed passages combine to form a B♭ minor pentatonic scale. This one measure might give a good model for

how a musician would practice this type of phrase, for when alternating between two different pc-sets or scales, repetitive patterns naturally emerge. The usage of C2-3 continues in 4.5.3, as Corea fills an entire measure with the A♭ whole-half diminished collection. Notice how, again, Corea’s phrase is broken up into a new section each beat, where he leaps to a slightly lower register each time. The result is that the line descends with velocity towards a low point, but it never feels as if it is traveling linearly.

Corea’s solo on Raju is extremely dense with information on how to play outside of the tonal center in jazz fusion. While his harmonic approach was very similar to his solo on “Return to Forever,” the phrases in this particular solo are often so long that they become even more difficult to understand. He rarely, if ever, utilizes polytonality, instead opting for a mix of pc-set transposition and octatonicism. There are still moments of characteristically blues-influenced vocabulary, but for the most

part, the blues play a less active role in this solo than in “Return to Forever.”

“Sansho Shima” is a composition by multi-reedist Bennie Maupin which was featured on Herbie Hancock’s 1976 album

Secrets. By this point, Herbie Hancock had made numerous fusion recordings both as a sideman and as a leader, most notably Head Hunters and Thrust. When Hancock formed his Head Hunters band, he wanted to embrace funk to its fullest extent. As such, Sansho Shima contains many qualities which define funk compositions; some of these qualities include a repetitive bass riff and drums playing straight eighth notes with an emphasis on beat one. The piece is composed primarily in G Dorian, and Hancock's solo is played entirely over a vamp on G minor. Hancock plays two solos on the recording; first he plays clavinet, then he plays “piano.” The following serves as an analysis of his piano solo, which follows directly after the clavinet solo.

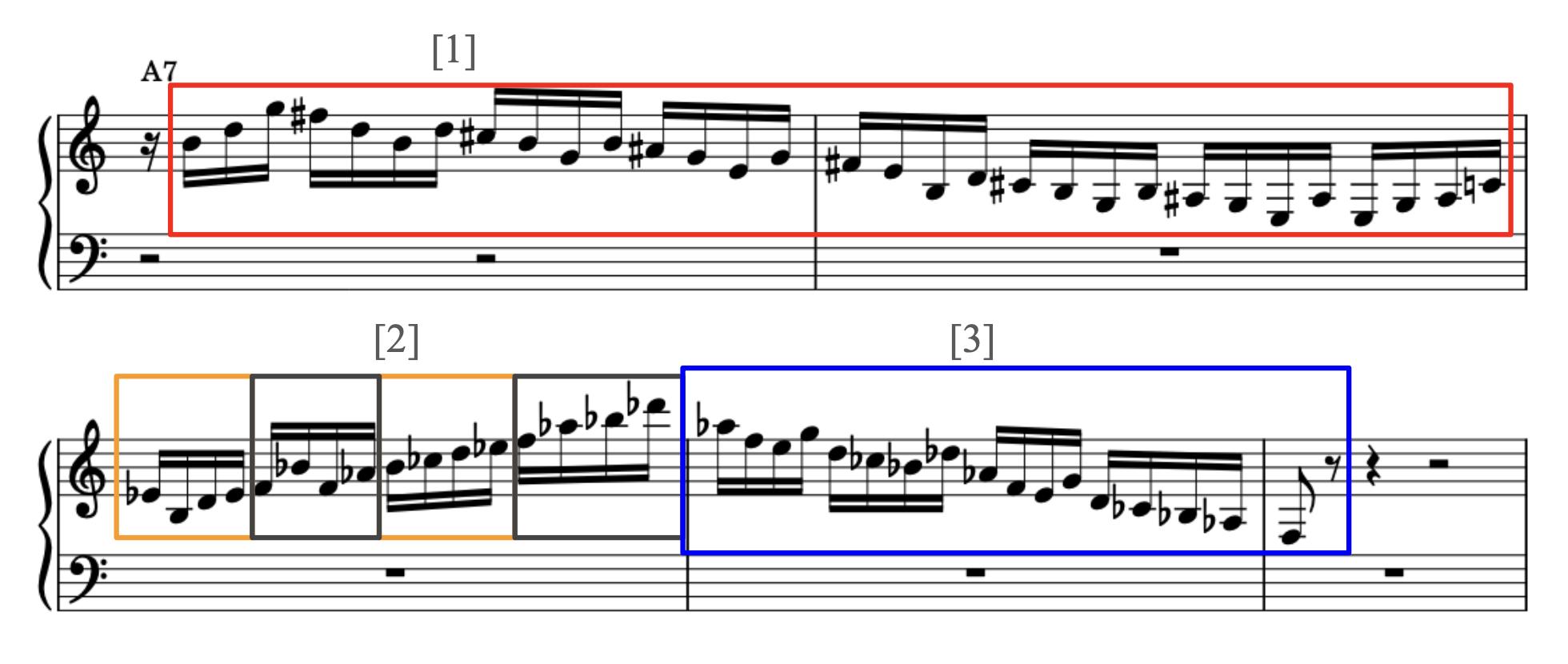

Hancock establishes the tonality throughout the solo in many ways. In the second measure, he arpeggiates a D-7, and starts the next phrase with a piece of the G minor pentatonic scale. D-7 is one of the diatonic 7th chords of G Dorian but is harmonically rich due to the presence of the 9th (A) and 11th (C). Note, however, how Hancock leads into the long chromatic phrase in bar 3 (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1: A passage from Hancock’s solo on Sanhso Shima (in treble clef).

While F♯ is non-diatonic, it here serves to provide a chromatic enclosure, where the F♯ and the B♭ together are meant to chromatically lead into the notes that follow, which occur between them. This is an integral part of bebop vocabulary, so it is

interesting that Hancock would apply it in this setting. After a long run featuring a mix of pentatonic and Dorian elements, Hancock returns to the harmonically rich arpeggios, this time using D- and A- triads respectively (Figure 5.2). The A- in particular contains an E, which is the characteristic note of G Dorian. Note that again, Hancock uses the leading tone.

Figure 5.2: A passage from Hancock’s solo on Sanhso Shima (in treble clef).

After the chromatic run in the second measure of this passage, however, Hancock subverts expectations in a new way by playing an E♭. This is out of line with our expectation due to the constant use of E♮ throughout the recording up until this point.

Figure 5.3: A passage from Hancock’s solo on Sanhso Shima (in treble clef).

In 5.3.1, Hancock plays to the B♭, first with the pentatonic fragment pc-set T5[035], then replacing the F with a G♭ before simply going down the chromatic scale. Hancock utilizes C2-31 in 5.3.2 before using a fragment of B major in 5.3.3, a tonal center which he escapes using, again, the chromatic scale. He returns to G minor in 5.3.4, where he plays a piece of what could be the D

minor or A minor pentatonic scale. Similar to the conclusion of 5.2, however, he incorporates E♭, which is a surprise in the context of G Dorian, especially when he follows the E♭ with the G minor pentatonic scale. 5.3.5 shows Hancock ascending a C minor scale which ascends to a D♭, which is the characteristic note in the G minor blues scale. 5.3.6 begins with T8(C2-3) and is followed by a chromatic run leading to D. Here, Hancock plays what may be a fragment of G minor or D minor pentatonic. 5.3.7 shows Hancock ending this passage in the fashion which has been most common so far, viz., a chromatic scale.

While both Hancock and Corea use chromaticism heavily in these solos, their approaches clearly differ in many ways. In these contexts, Corea is more prone to using diatonic scales or other non-diatonic scales. He creates interest by transposing them to unexpected keys and often uses blues vocabulary as a means of transitioning from one tonal anchor to the next. Hancock, however,

uses more pentatonic vocabulary and uses raw chromaticism to move towards distant tonal anchors. He rarely establishes a moment of true stability in a tonal anchor, instead preferring to stay in constant chromatic motion. His approach feels much more dense than Hancock’s, and that is because it is: by using the chromatic scale, he uses NDTC-UB2, whereas Corea favors NDTC-UB3; the former is inherently more dense than the latter.12 The use of chromaticism, and specifically the concept of the enclosure, is also reminiscent of bebop, an influence which was not quite as obvious in Corea’s solos.

The purpose of this is not necessarily to compare the styles of Hancock and Corea, but more so to compare their approaches to improvisation in these settings. The discrepancies between them can perhaps be explained by the style in which they were

12 By density, I mean the amount of notes in an octave when a pc-set is transposed and repeated ad infinitum. Clearly, the chromatic scale is necessarily the most dense scale.

improvising. Hancock’s approach to “Sansho Shima” could be described as heavy and severe, while Corea’s approaches to “Raju” and “Return to Forever” are more light and rapid. Their diverse approaches to chromaticism are likely the reason for the difference in tone: the aforementioned “density” could perhaps lead to a heavier sound, while NDTC-UB3 appears relatively thin.

6. Mehldau on “Vou Correndo Te Encontrar / Racecar”

Brad Mehldau is a jazz pianist who began his career in the early 1990s. Some notable collaborations include Joshua Redman, Pat Metheny, and Charlie Haden. He was particularly influenced by rock music, saying that progressive rock was “his gateway to the fusion that eventually led to his discovery of jazz.”13 That influence certainly plays a major role in his 2022 album, Jacob’s Ladder. One of the tracks from the album, “Vou Correndo Te

13 “Jacob's Ladder,” Brad Mehldau, accessed April 12, 2024, https://www.bradmehldaumusic.com/jacobsladder#:~:text=Brad%20album%20Jacob’s%20Ladder%20features,to%20his%2 0discovery%20of%20jazz.

Encontrar / Racecar” is a cover of a song by the metal band

Periphery, and the harmony has strong elements of modal mixture.

Mehldau reimagines the track with electronic textures, setting the stage for him to take an acoustic piano solo at a climax of the song. The solo, played primarily in the key of B♭, involves a similar level of chromaticism to the improvisations previously discussed, but Mehldau’s methodology differs slightly.

Figure 6.1, above: A passage from Mehldau’s solo on Jacob’s Ladder.

Figure 6.2, below: A passage from Mehldau’s solo on Jacob’s Ladder.

In 6.1, Mehldau starts his solo with standard blues vocabulary, thus ensuring that B♭ major will be the tonal center, while modal mixture can be expected due to the presence of D♭.

6.2 shows Mehldau playing a sequence of diatonic arpeggios, moving from B♭Δ to Bb-7 to A♭Δ to E♭-. Observe, however, that while D♭Δ and E♭ -are both diatonic triads within B♭ minor, they are not within B♭Δ; thus, this is an instance of modal mixture, with

an emphasis on triadic arpeggios as the basis of the melodic structure.

Figure 6.3: A passage from Mehldau’s solo on Jacob’s Ladder. Having developed the harmonic content using modal mixture, Mehldau plays a D♭ major seventh arpeggio followed by a G major seventh arpeggio, as shown in 6.3. This is the first instance of more radical chromaticism, as his decision can no longer be explained with the help of blues vocabulary or modal mixture. Instead, he takes an arpeggio diatonic to B♭ minor, viz., DbΔ7, and transposes it up a tritone to GΔ7. While he does not remain in G major long enough for this to be an example of polytonality, this method of transposition is certainly similar to it. Unlike the solos of Corea and Hancock, whose chromaticism is often non-diatonic at every

step, Mehldau incorporates more diatonic trichords and tetrachords, thus transposing familiar textures.

Shortly after the aforementioned passage, Mehldau plays down the chromatic scale. Also appearing in Herbie Hancock’s solo on “Sansho Shima,” this is a common method for moving from one idea to the next, particularly when the latter is in a key distant from the former. In this case, it eventually leads back to the tonic, as Mehldau plays a B♭7 arpeggio. Note how the figure starts with a D♭Δ7 arpeggio, but ends with a B♭7 arpeggio. This is indicative of the aforementioned duality between major and minor found in blues-influenced music.

Figure 6.4: A passage from Mehldau’s solo on Jacob’s Ladder. In 6.4, Mehldau again uses diatonic arpeggios in non-diatonic contexts, as well as blues vocabulary to return to the tonic. In 6.4.1, he plays a CΔ arpeggio before borrowing fragments from the chromatic scale. 6.4.2 shows Mehldau playing a G♭Δ arpeggio, which is as distant as possible from C major. In 6.4.3, he outlines a tetrachord which could be from A major, after which he plays an A-7 arpeggio. This is significant because both A-7 and CΔ are diatonic to C major, and they only differ in one note (removing the A from A-7 yields CΔ). Thus, Mehldau begins the phrase with a

diatonic arpeggio (which is not diatonic to the tonality) and moves away from said arpeggio, but eventually returns to it. After this moment of closure, he returns to the B♭blues tonality which defines the solo. Every pitch he plays in 6.4.4 is part of the major blues scale. Just as the solo begins with conventional blues vocabulary, it ends that way; he establishes the blues as the norm, and any phrase which does not involve blues vocabulary is external to the tonality.

Corea and Hancock both make frequent use of the octatonic scale in their improvisations, so it is relevant to investigate what the octatonic scale is and why it might be applicable in this context. The octatonic pitch set can be imagined in numerous different ways, with each one providing a different explanation of its practical significance. The most common explanation is that it is the scale which arises upon alternating between half steps and whole steps. This also involves the set having many symmetric

properties: transposing an octatonic scale up by a minor third will result in nothing more than the same set of pitches. Because it is reflective about the minor third, the octatonic scale also carries a great association with the diminished chords, which is why it is sometimes called the diminished scale. Within the octatonic scale there are two full diminished chords, while there are only three full diminished chords in total. This means that any octatonic scale is some combination of two out of the three possible diminished chords, and that the complement to the octatonic set will also be a diminished chord. The diminished scale, however, is also symmetrical about the tritone, which leads to a new understanding of its nature. The four notes of the whole-half diminished scale will be equivalent to the first four notes of a minor scale [0235], and the next four, because the octatonic collection is symmetrical in this way, will be T6[0235]. For example, the C whole-half diminished scale can be alternatively thought of as C minor for four notes followed by G♭ minor for four notes. This is similar to the strategy

used by Mehldau in his solo on “Racecar,” where he transposes a major 7th arpeggio by a tritone. While the actual harmonic content is different, the concept is the same: transposing a simple set of pitches by a tritone invokes a feeling of distance.

Perhaps the most telling observation was about the reliance on extant musical traditions throughout improvisations. Regardless of whether a passage was deeply chromatic, concepts from the blues, bebop, and rock found their way into these fusion improvisations. This offers perhaps the best possible explanation for why fusion was able to succeed commercially: by making constant reference to harmonic colors that the listener is already familiar with, an improviser can make even the most arduous passages sound like they belong. The result is a confounding of pre-existing musical traditions rather than an abandonment; fusion takes influence from the blues, bebop, rock, and free jazz to create a style which is at once both alien and familiar.

Corea, Chick. “Raju.” Five Peace Band Live, Concord, 2009, track 1. “Bitches Brew.” Miles Davis Official Site, June 23, 2023. https://www.milesdavis.com/albums/bitches-brew/.

Corea, Chick. “Return to Forever.” Return to Forever, ECM, 1972, track 1. Hancock, Herbie. “Sansho Shima.” Secrets, Columbia, 1976, track 7.

“Herbie Hancock: Biography, Music & News.” Billboard. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.billboard.com/artist/herbie-hancock/charthistory/tlp/.

“Jacob’s Ladder.” Brad Mehldau. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.bradmehldaumusic.com/jacobsladder#:~:text=Brad%20album%20Jacob’s%20Ladder%20 features,to%20his%20discovery%20of%20jazz.

Joy2Learn. “Wynton Marsalis | History of Jazz - Fusion.”

YouTube Video, 0:51. July 8th, 2013.

Liebman, David. A Chromatic Approach to Jazz Harmony and Melody. Advance Music, 1991.

Mehldau, Brad. “Vou Correndo Encontrar / Racecar.” Jacob’s Ladder, 2022, track 8.

Persichetti, Vincent. Twentieth-Century Harmony. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961.

“Romantic Warrior - Return to Forever: Album.” AllMusic. Accessed April 11, 2024.

https://www.allmusic.com/album/romantic-warriormw0000188588#awards.

Spartz, James Travis. “Chick Corea’s Cheap but Good Advice for Playing Music in a Group.” Medium, December 17, 2019. https://jtspartz.medium.com/chick-coreas-cheap-but-goodadvice-for-playing-music-in-a-group-b9b52b49a96e.

Trench, William F. Introduction to Real Analysis. Minneapolis: Open Textbook Library, 2013.

Waters, Keith. Postbop Jazz in the 1960s. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.