25

INTERSIGHT 25 2023

INTERSIGHT 25 2023 25

paying attention to the fine detail and craft of physical models | planning and dedicating time | doing my part in volunteering | empathizing, listening, sharing | being nice, period | staying passionate even when it's hard | spreading positivity when I can | staying kind when others aren’t | allowing it not to be perfect | being an ear for someone | taking time to listen | interacting | enjoying the process | writing about what we see, hear, and do | studying | taking a breather | making dinner for a friend | picking each other up when we’re down | showing integrity

| showing pride | being loyal | putting in time and patience | thinking about my actions influences | lending a hand | taking risks and trying to push myself

| designing for inclusivity | growing a community and being there | trying new methods of design and drawing | trying to be what the world needs | bringing each other up, I would not be where I am today without all my support networks | showing respect for the environment and the places I go | sticking to my standards | recycling? | sleeping the night before review | sending our notes in the group chat | putting my all into it | keeping my carbon footprint low | spending time to polish it | educating myself | being mindful about my decisions for the environment | scrapping off my roommates car | holding the door | taking time to talk | eating tasty food | making sure it is saved online before it goes missing | respecting each other’s ideas and opinions | paying attention to the details | being thorough | keeping up with current events | researching | using my voice | communicating | drawing with rigor | being proud of my effort | being a good neighbor | making my work something I enjoy | staying informed | being thoughtful about how the work will be received | being a positive person | making other people’s lives a bit better | taking time for my models | maintaining | creating spaces to make people feel comfortable | reviewing each other’s work | devoting copious amount of time to it | wearing a smile | listening to them | pulling all-nighters | designing for handicapped people | offering food | making every design decision with conscious intention | putting in the hours | empathizing | reminding my classmates to save their work

25 INTERSIGHT | 2022

The School of Architecture and Planning University at Buffalo

The State University of New York

125 Hayes Hall

Buffalo, NY 14214-8030

www.ap.buffalo.edu

www.ap.buffalo.edu/publications

Intersight is an annual publication that highlights the work of the students at the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo. The intent of this journal is to record and discuss current academic and cultural activities of the school. This issue includes coursework completed throughout the calendar year of 2022.

All photographs and drawings are courtesy of the Visual Resources Center, contributors, and students unless otherwise noted. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent volumes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except for copying permitted by section 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press. Every effort has been made to see that no inaccurate or misleading data, opinions, or statements appear in this journal. The data and opinions appearing in the articles herein are the responsibility of the contributor concerned.

Editor: Charlie Stevens

Assistant Editor: Madeleine Sophie Sutton

Committee Chair: Stephanie Cramer

Committee: Miguel Guitart, Jordana Maisel, Erkin Özay

Editorial Assistance: Rachel Teaman, Caryn Sobieski-Vandelinder, Tara Taylor

Printed by Beyond Print Solutions

Typeset in Europa, Twentieth Century

© 2023 School of Architecture and Planning

University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

All rights reserved

25 | First Edition

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Intersight Volume 25

ISBN: 978-0-9973650-0-9

PREFACE

Why do we care about the things we do? Our motivations often derive from the standards we hold ourselves accountable to or from a desire to create change in the organizations we represent.

Intersight 25 originates from a personal interest to answer this question by reflecting on the work produced by the University at Buffalo’s School of Architecture and Planning students. I have always admired the time and effort students commit to their work, so documenting this, using the lens of care, made sense to me.

During my undergraduate and graduate experience, I became as involved in the School as much as I could. Serving as a student representative for my cohort allowed me to highlight my classmates' concerns and work with a team of administrators to address them. Doing so put me at the forefront of discussion and resolution between students and faculty. Through this process, I learned how we as a School address each other's needs and wants.

I first learned about the annual Intersight publication when I was a first-year student. I was asked to comment on the 21st edition of Intersight given the prompt, “What is architecture to you?” I responded with, “Architecture is taking an idea and finding a million different ways to bring it to life.” Returning to this question and answer four years later, I still find it to be true. The diverse ways

students reflect on their work over the course of a semester demonstrates this, and this is what most fascinates me.

In gathering perspectives from students and faculty to understand how themes of care are progressing at the School, I was met with a response from one student, “I didn’t think that as a freshman, anyone would care what I have to say.” Quotes like this have provided the context for Intersight 25 to live in, unearthing the motivations to answer why and how we care for our work, our world, and each other.

As someone who hopes to be an educator at the university level one day, I found this process enlightening. The process of gathering work, contextualizing it, and building a meaningful verbal and visual narrative gave me greater appreciation of how our School environment connects students and faculty.

I owe a tremendous thank you to the editorial staff for their collective guidance, my assistant editor and next Brunkow Fellow, Madeleine Sophie Sutton, and my faculty committee for their time and many notes in putting this book together. Intersight 25 is a reflection of how I have seen this School grow, and as a platform for students to communicate a passion for design and inquiry in their field.

8

CARE:

A feeling of serious interest or concern to provide what is necessary for the welfare of someone or something important to us.

9

LETTER FROM THE DEAN

Robert Shibley, FAIA, FAICP, SUNY Distinguished Professor and Dean of the School

In focusing our view of student work through the lens of “care,” Intersight 25 reveals the essence of the School of Architecture and Planning - the core of who we are, what we do, and why we are here.

Care is the wellspring for our aspirations in world-making and the creation of equitable, sustainable and resilient places for all. It is the sense of purpose and dedication to craft we bring to our work. It is the generosity of our support for each other that nurtures and sustains our community. And it is the vector of impact that draws our students ever outward in their pursuits, to new contexts, cultures and places, to new intellectual frontiers, and to new challenges requiring radical acts of care.

According to Charles Stevens, 2022-23 Brunkow Fellow and Intersight 25 editor, care is an uplifting force acting continuously upon our work – from the origins of an idea to the depth of its impact, and the “messy struggle” in between.

“This year’s book celebrates the inceptive processes and potential impacts of student work just as much as the finished product,” says Stevens. “Positioning care as a framework for our design and planning process creates links to larger-scale social and cultural effects."

An active member of the student body since joining UB in 2018 as a BS Arch student, Stevens says he has always

admired the time and effort his peers put into their work. “Documenting this, using the lens of care, made sense to me. Intersight 25 is a reflection of how I have seen this School grow.”

The ripple effects of the pandemic on our community dynamic brought new urgency to his curiosity. “We were compelled to adopt a new culture of care; a culture prioritizing our social environment,” adds Stevens, now a student in the Master of Architecture program.

Bringing a great deal of care to his curatorial endeavor, Stevens weaves this theme through 36 student works and five conversations with the School community, giving shape to the motivations, innovations and possibilities of our investigations in architecture, urban planning, real estate development and environmental design.

Indeed, the book joins a rich tradition at the School that dates back more than 30 years. Supported by the generous endowment of Kathryn Brunkow Sample and former UB President Steven Sample, Intersight chronicles the creative and scholarly outputs of our students and reflects on the pedagogy of our programs.

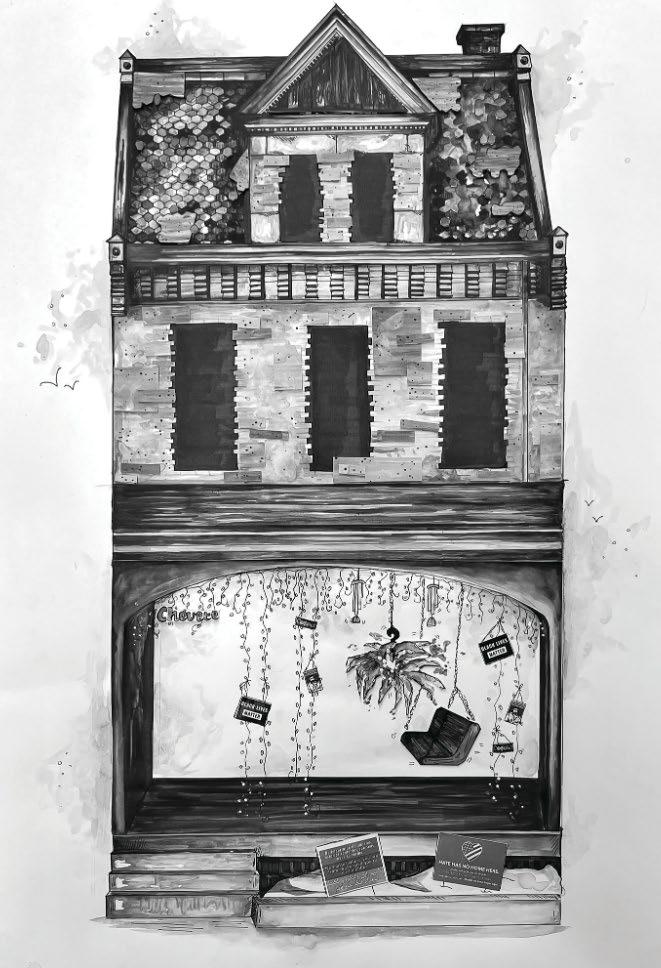

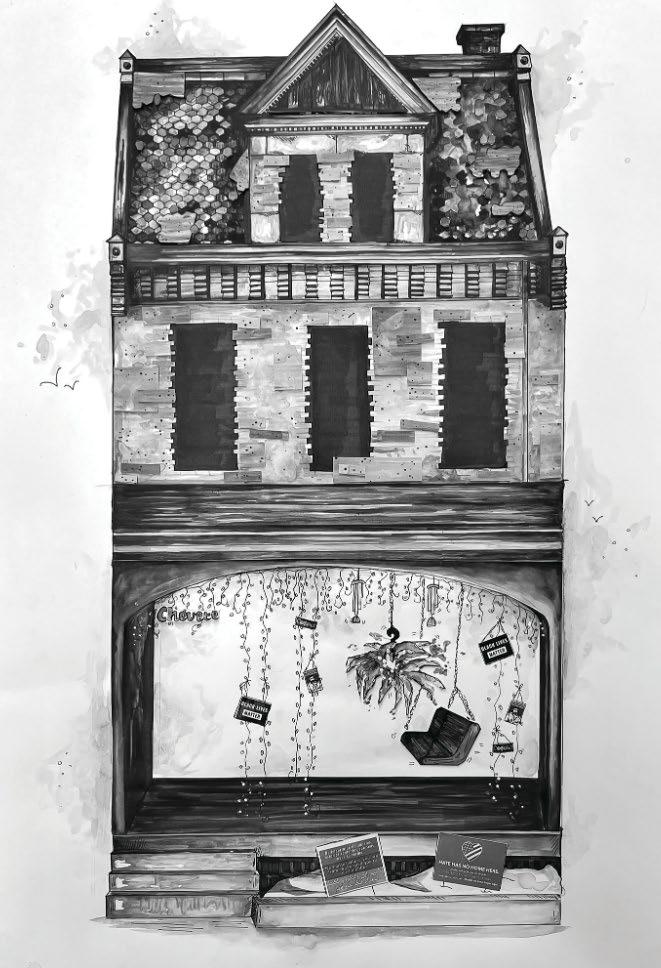

In the following pages, care for our work can be seen in the imagination and magnanimity of our ideas, from a thesis project exploring fungus-based architecture to a voluntary student effort that helped a business owner on

10

of Architecture and Planning

Buffalo’s East Side win a storefront revitalization grant, to prison cell design proposals that humanize spaces of mass incarceration.

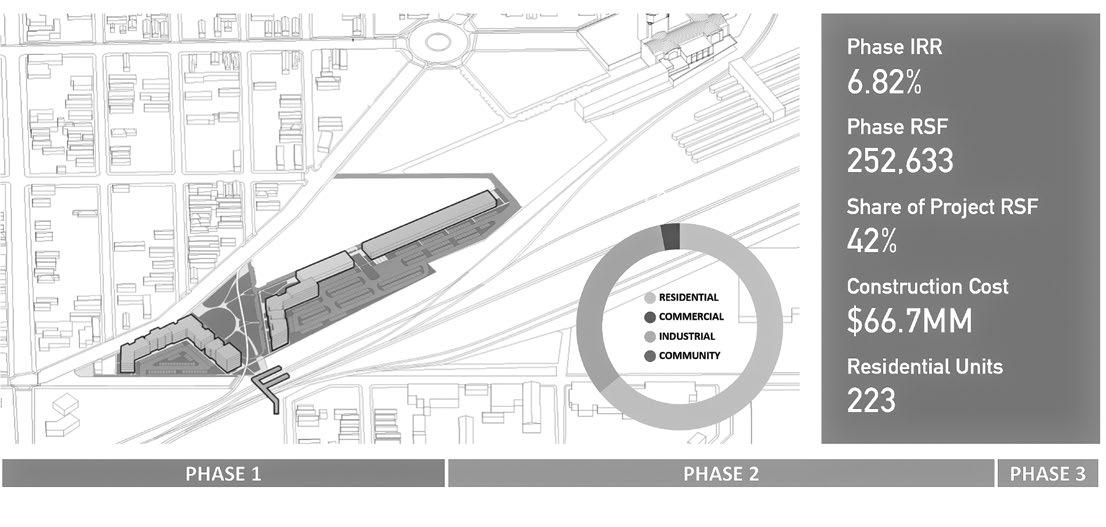

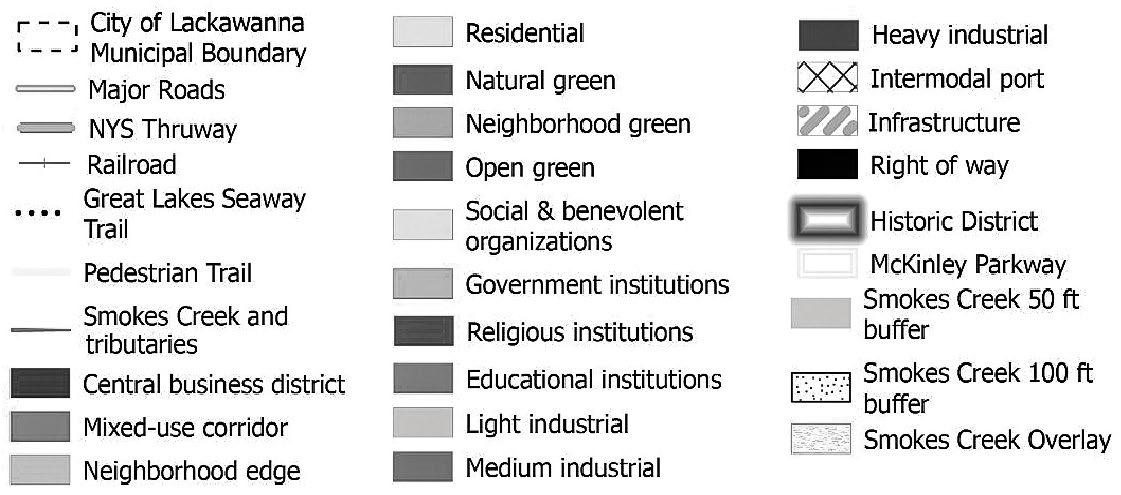

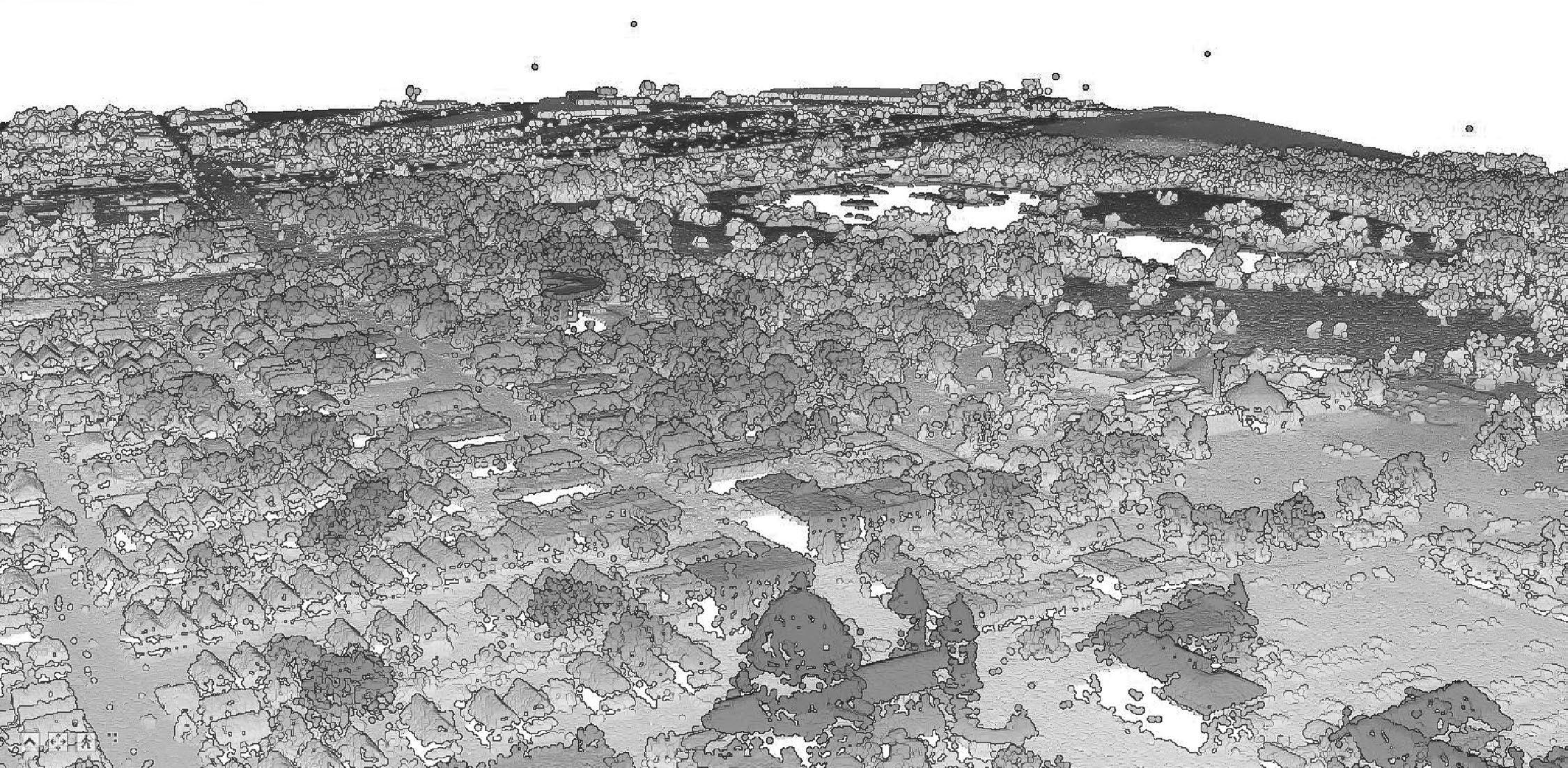

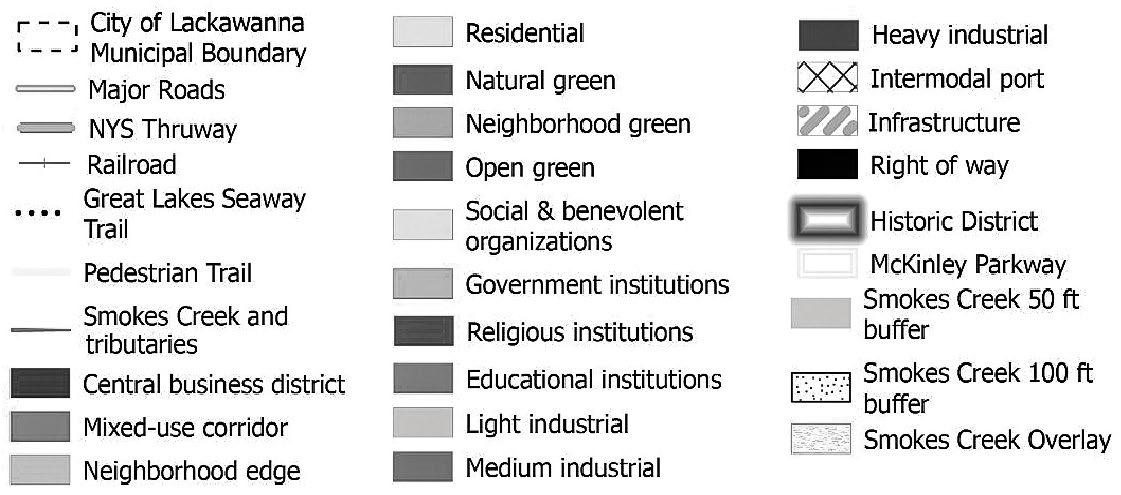

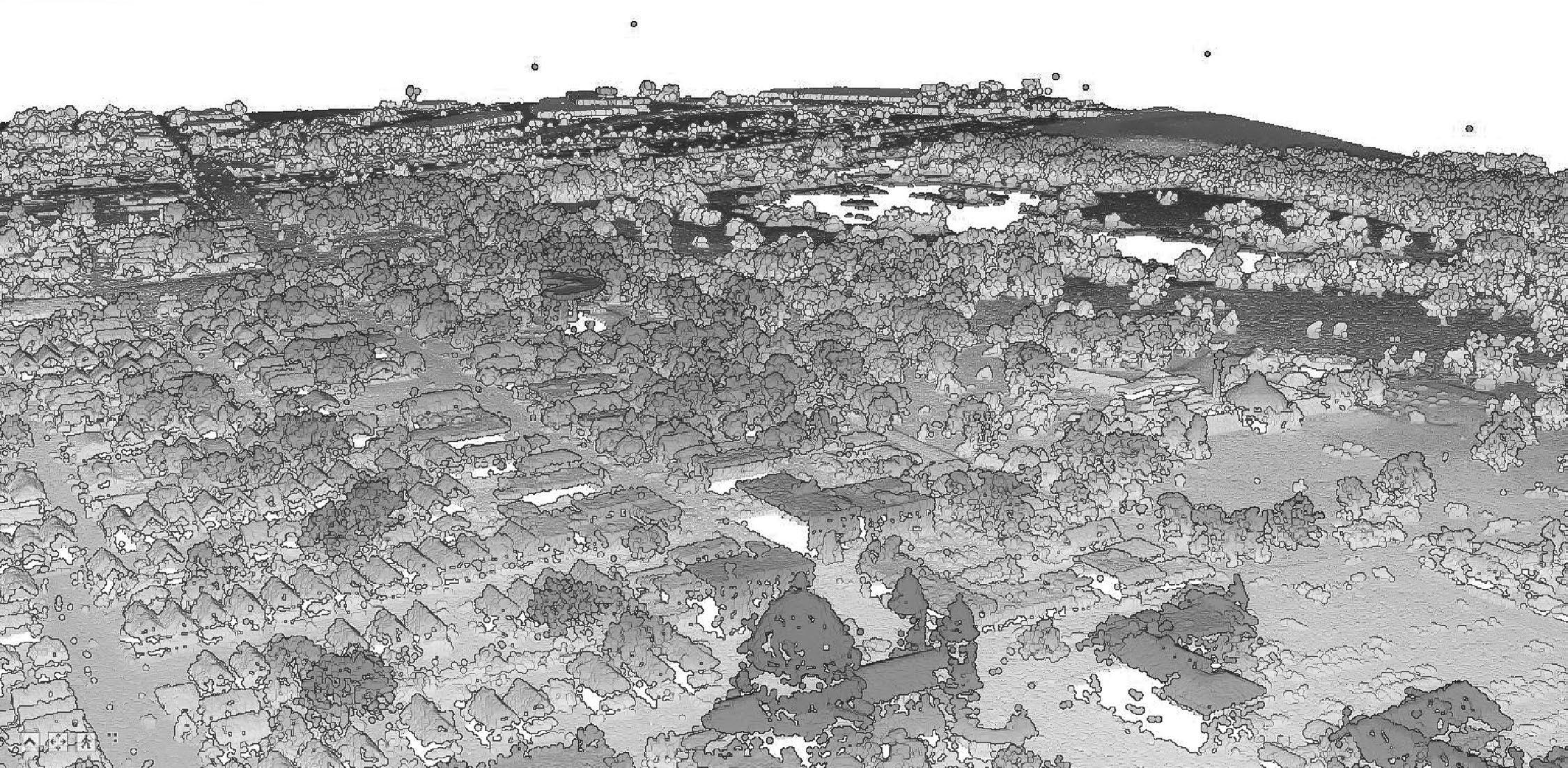

Care for each other is cultivated in first-year architecture studio, where students make the journey into new ways of seeing by learning from and relying upon their peers. It is exchanged between architecture and real estate development students co-designing a 16-acre development on Buffalo’s East Side. And it is rooted in the community input urban planning students incorporated into their smart growth plan for Lackawanna, a city still reeling from its postindustrial decline.

Care for our world is realized through the potential of our work as it comes to life in our communities and evolves into the next question, with new possibilities for design and planning to make life better for all.

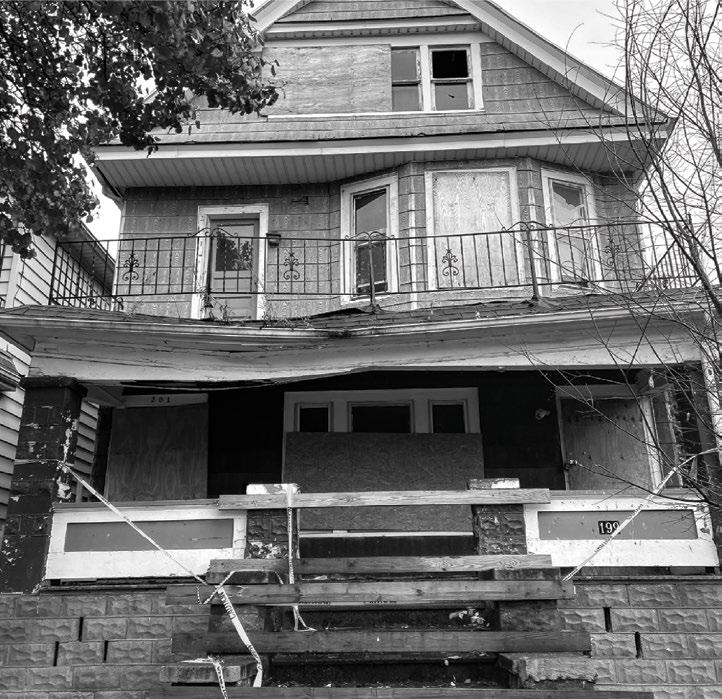

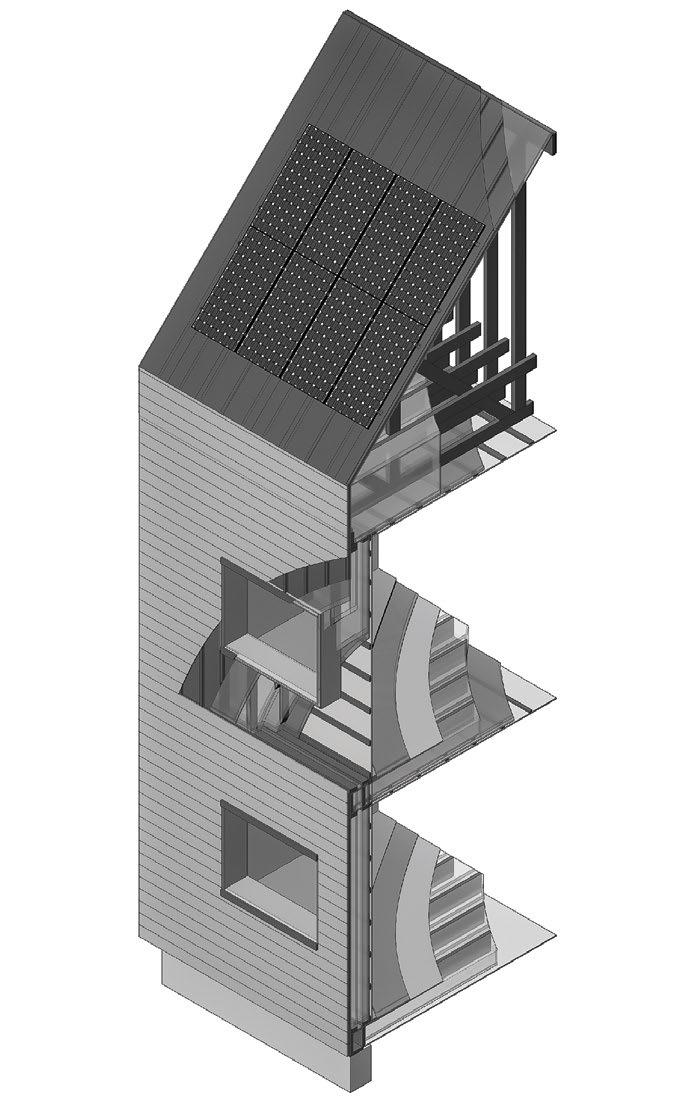

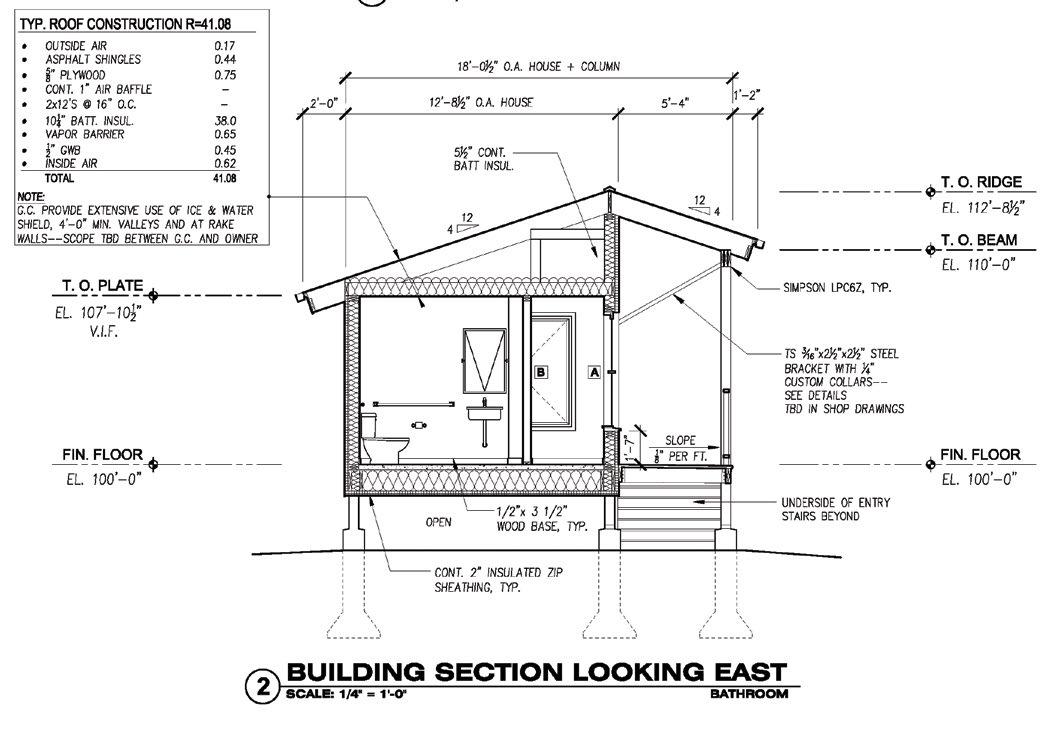

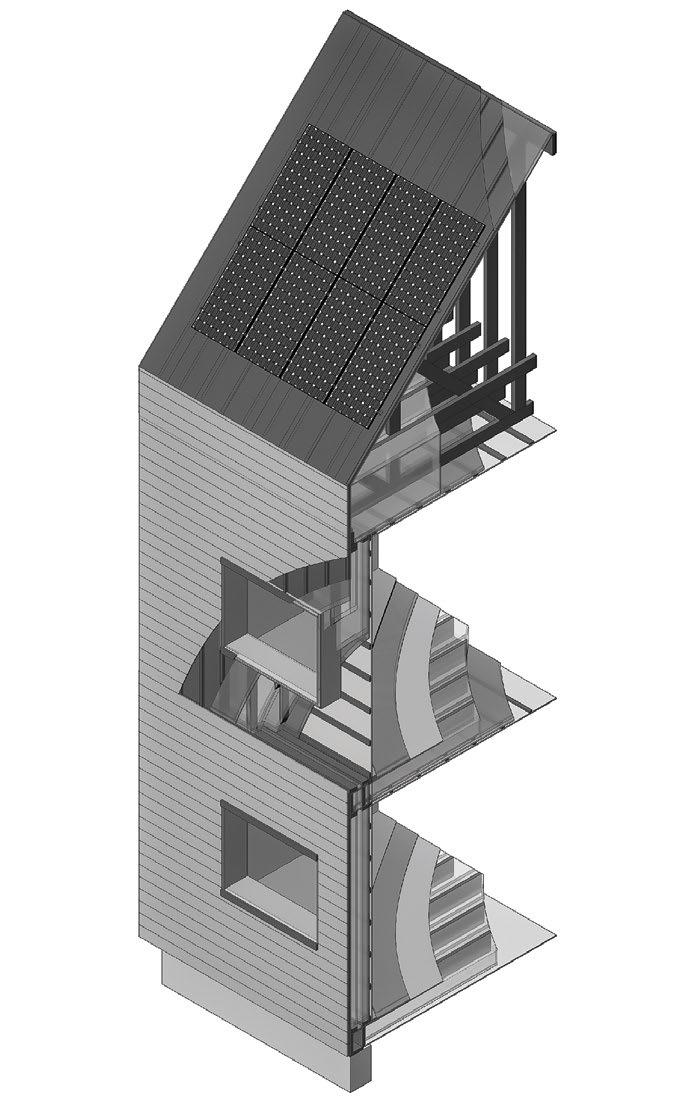

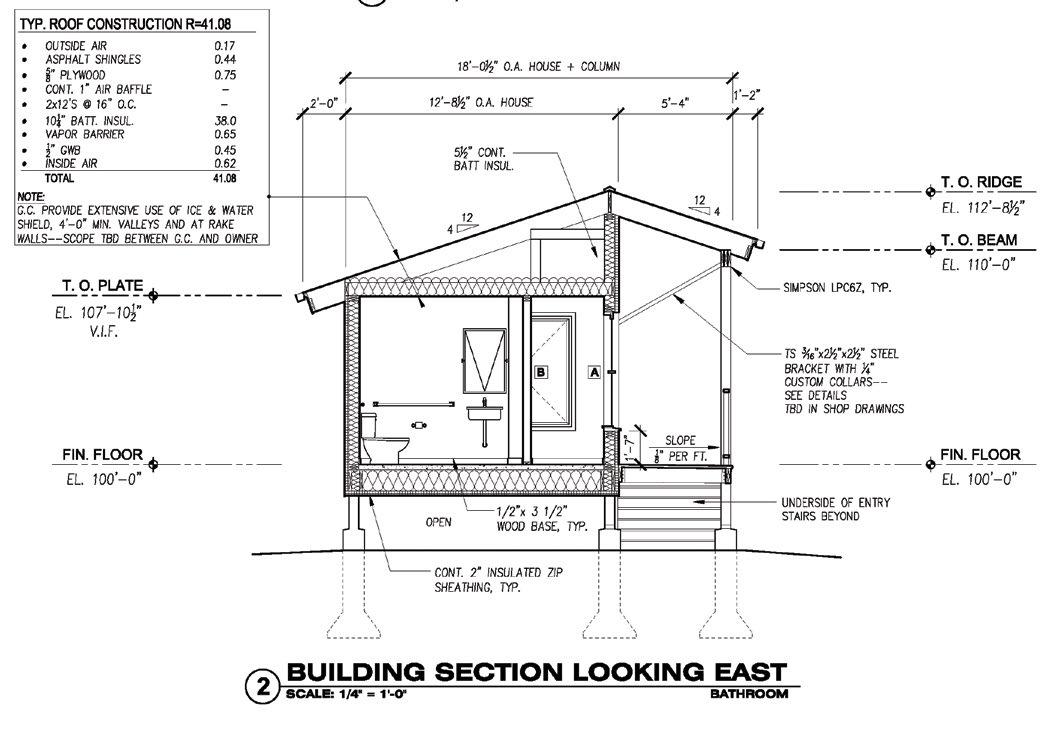

Consider some of the results: A series of tiny home prototypes now being constructed for people experiencing homelessness in Syracuse, NY. A training program in passive house design to support Buffalo’s climate resiliency and green workforce development. And a new wayfinding system that will help students at Buffalo’s St. Mary’s School for the Deaf navigate the building and connect as a community.

As we look ahead to the complex challenges facing cities today, care is our source for hope. As such, we must be

its custodians. Nurturing its origin source – our hearts and minds - through inspiration and curiosity. Tending it in our community through humility and respect. And carrying it into our world through our lifelong ambitions as architects, planners and developers.

I invite you now to explore Intersight 25, immerse yourself in our culture of care and rediscover your spaces of purpose, connection and impact.

11

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Intersight is an annual collection of student work from the School of Architecture and Planning. The journal bridges and contextualizes the work with conversations and stories that have emerged in the studios, classrooms, and numerous sites out in the world that have come into the focus of our intellectual and creative curiosities. This edition highlights our collective work from the 2022 calendar year through the conceptual lens of care. Moreover, just as the previous 24, this milestone 25th edition of Intersight aims not only to reflect on our past conversations, but also foster new dialogue.

CARE

Intersight 25 examines and documents the various ways we care for our work, each other, and the world. This year’s book celebrates the inceptive processes and potential impacts of student work just as much as the finished product: bringing to light the messy struggle of design, planning, and collaboration; emphasizing all that remains concealed along the pathways of process; framing how our work relates to and shapes our world. Dissecting the concepts that push us to take specific approaches uncovers the passion students have for their work. Positioning care as a framework for our design process reveals linkages to large-scale social and cultural effects.

Much of this perspective derives from our shared experience of a debilitating pandemic. As a School and larger community, we were compelled to adopt a new culture

of care, prioritizing our social relationships and collective environment. Re-evaluating ourselves required asking tough questions. Did students still care about learning as they did before the pandemic? Did faculty members lose their will to teach in a Zoom room, staring at blank screens? Were we ready to return to our communities, or did we prefer to remain isolated?

Intersight 25 addresses these questions by investigating student work from 2022 and recording first-hand accounts of student and faculty experiences. Understanding how projects progress from ideas to reality illustrates how the unseen work can impact the communities the School of Architecture and Planning serves.

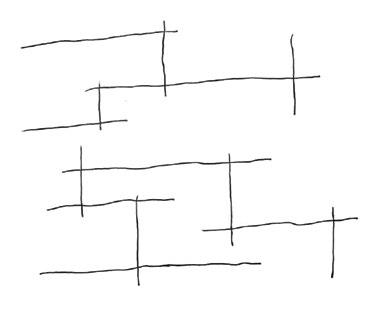

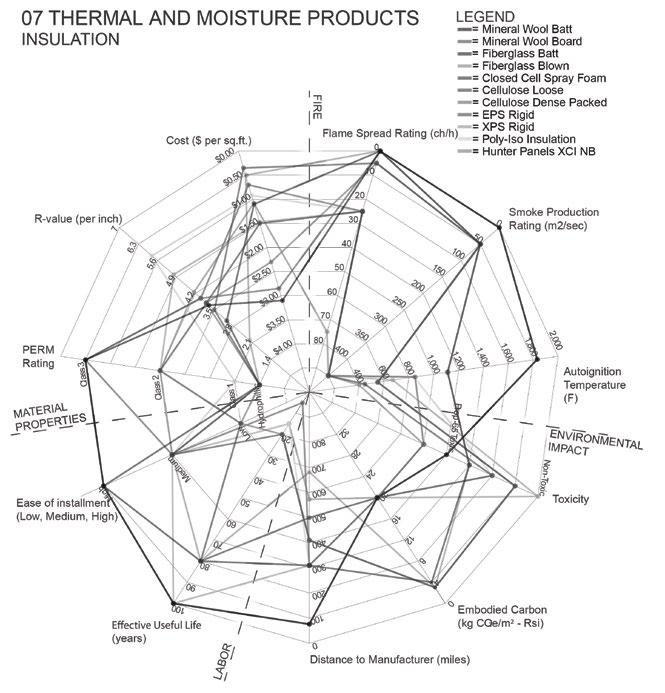

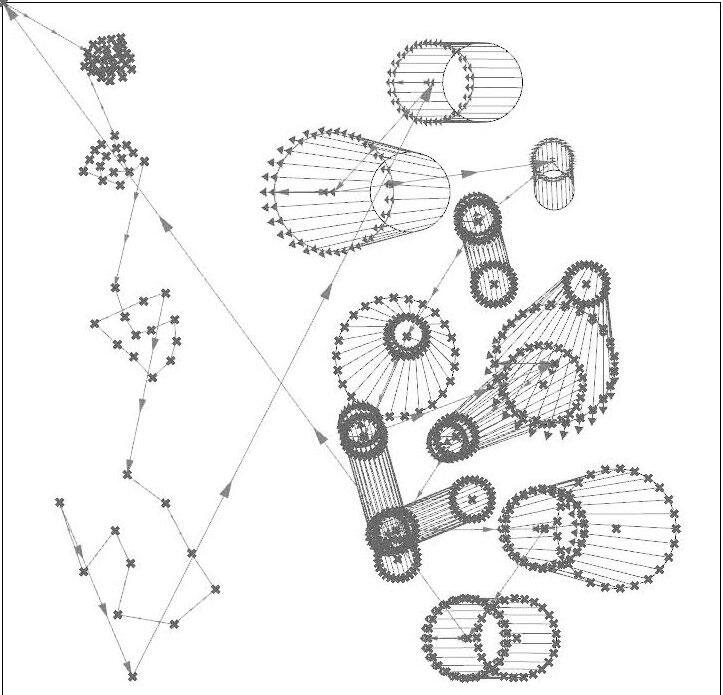

Each featured project or course is accompanied by a matrix diagram that further explains how this project addresses an aspect of “care” through the eyes of the editor. Each body of work represents multiple aspects of care. Ultimately, Intersight 25 reveals 36 unique combinations of care, providing insight into the concepts explored within the work.

CARE FOR OUR WORK

The projects included in this book attest to the fervor students have for the work we create. Dissecting the care we show for our work through rigor and exploration exposes how we define the why. Rigor points to the conceptual and methodological clarity, ingrained in first-year students and

12

Charlie Stevens, MArch ‘24, Fred Wallace Brunkow Fellow (2022-2023), Editor

carried through to the graduate level. Exploration speaks to curiosities developed through experimentation and debate, investigated through iterative work and new technologies— forming evolving bonds between author and product.

The by-products of our thinking—as students of architecture, urban planning, real estate development, and environmental design—are captured in the study models, tracing paper, and questions we have raised and kept to ourselves—often changing our collective understanding of an issue or prompt. From this ideation and internal debate, we convey a message. Looking beyond our devotion to our work, Intersight 25 wants to acknowledge the invisible - the part we do not pin to the wall.

CARE FOR OUR WORLD

The ability to care effectively for our world lays the foundations for the meaningful impacts we aim to achieve. Caring for our world requires us to learn with and from the communities we work in. As such, care is about culture and relationships. Culture frames our outlook on human lifestyles and conditions our design decisions. Relationships speak to our engagement with communities and contexts, embracing their complexities.

We have embraced working with communities and along existing local initiatives rather than for or despite them as the norm for developing more meaningful projects. In this sense, how we, as designers, planners, and thinkers, engage

in active methods of care within our School correlates with our collective perspective on how to position our efforts in the world.

CARE FOR EACH OTHER

The relationships among students, faculty, and staff profoundly affect with whom and how we engage. We recognize the crucial bonds and support networks that characterize our social environment, and how they serve as a significant ingredient in students' journey through the School of Architecture and Planning. We often witness how much time and attention go into creating spaces where students feel safe and comfortable. These spaces are intended to encourage discussions and collective efforts to develop and reflect on our work. Collaboration over competition is the norm. Building on principles of mutuality has fostered cohorts committed to sustaining the health and well-being of those most important to us.

The conversations in Intersight 25 explore this space and the mutual support systems on display. The conversation prompts and groupings were deliberately constructed to reveal students' and faculty members' insights on elements of care exercised at the School of Architecture and Planning, both at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

13

OUR WORK

RIGOR

The conceptual and methodological clarity behind student projects, ingrained in first-year students and carried to the graduate level.

EXPLORATION

An investigation of new technologies and student perspectives, creating a bond between author and product.

CULTURE

Outlooks analyzing human lifestyle and the impacts our design decisions have on the natural or built environment.

OUR WORLD EACH OTHER

RELATIONS

Engaging with our communities and contexts, further embracing their complexities and municipalities.

CONVERSATIONS

Student groups discuss on UB's School of Architecture and Planning culture of care.

Freshmen + TA

Seniors + Professor Planning Students

3.5 yr. + International Students

Student Organizations

14

15 16 40 60 82 104 122 20 42 62 86 106 126 22 46 66 88 110 134 26 48 70 92 114 138 30 50 72 94 118 136 38 58 74 98 120 142

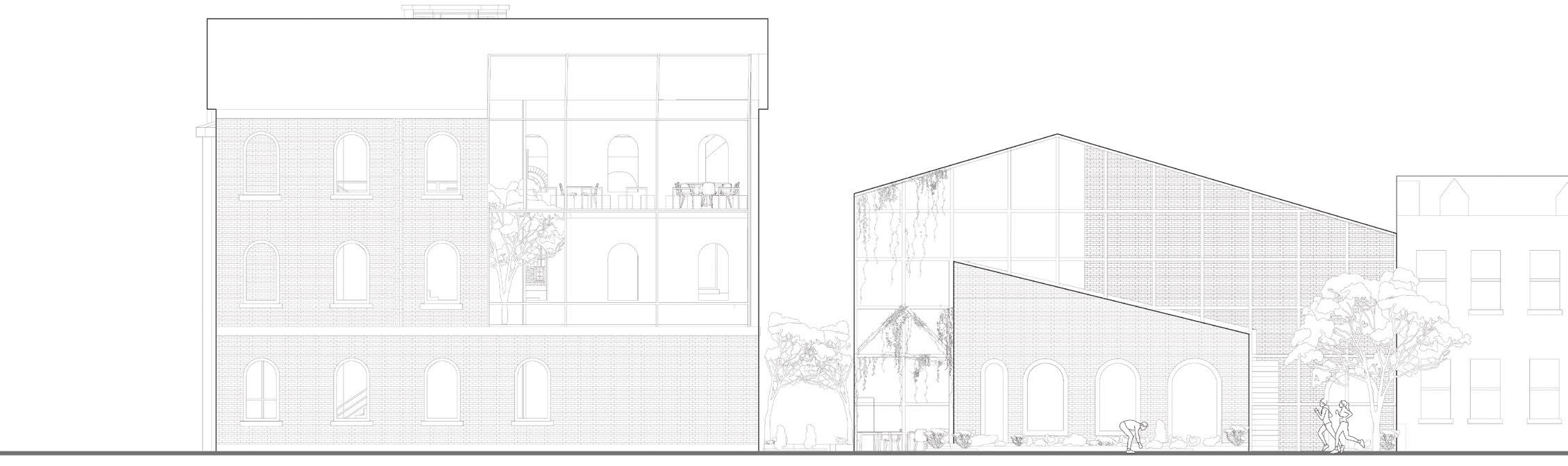

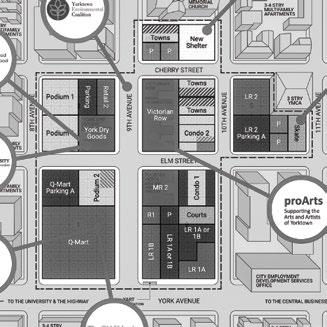

GOOD NEIGHBORS

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Lei Wang, Bobby Zhao (Inhabiting Mass); Bryan Hensen, James Metzger (Core Yards); Rebecca Liu, Mahrukh Mubarak (Shifting Edges)

Miguel Guitart, Michael Hoover

Fall 2022

ARC501

3.5-YR MArch

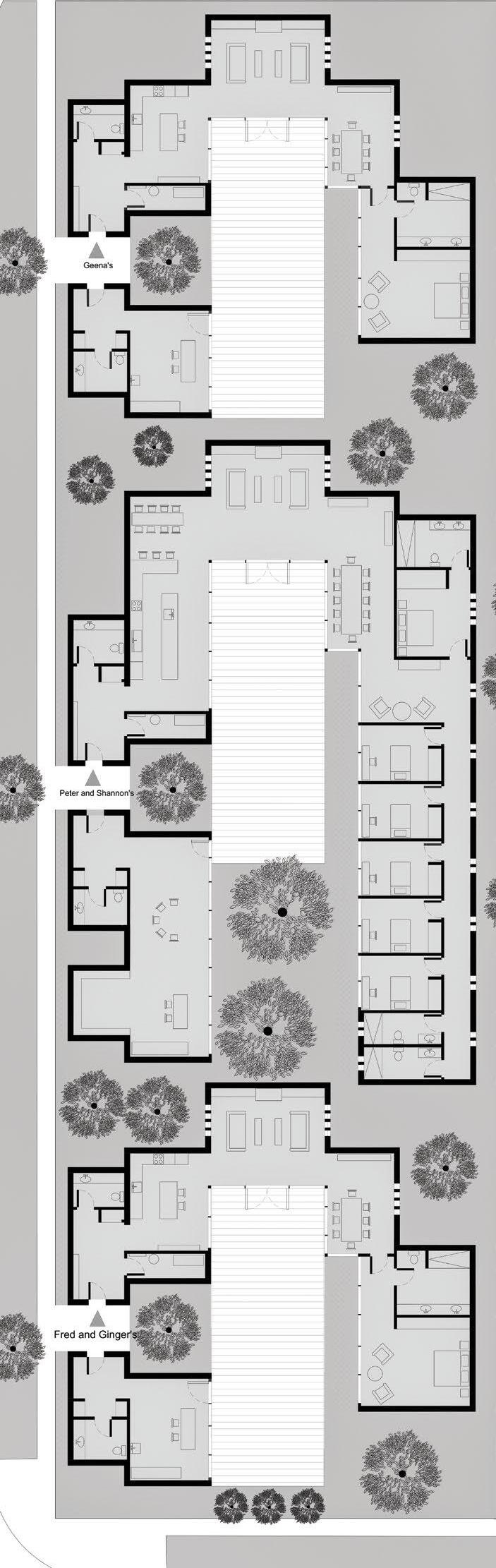

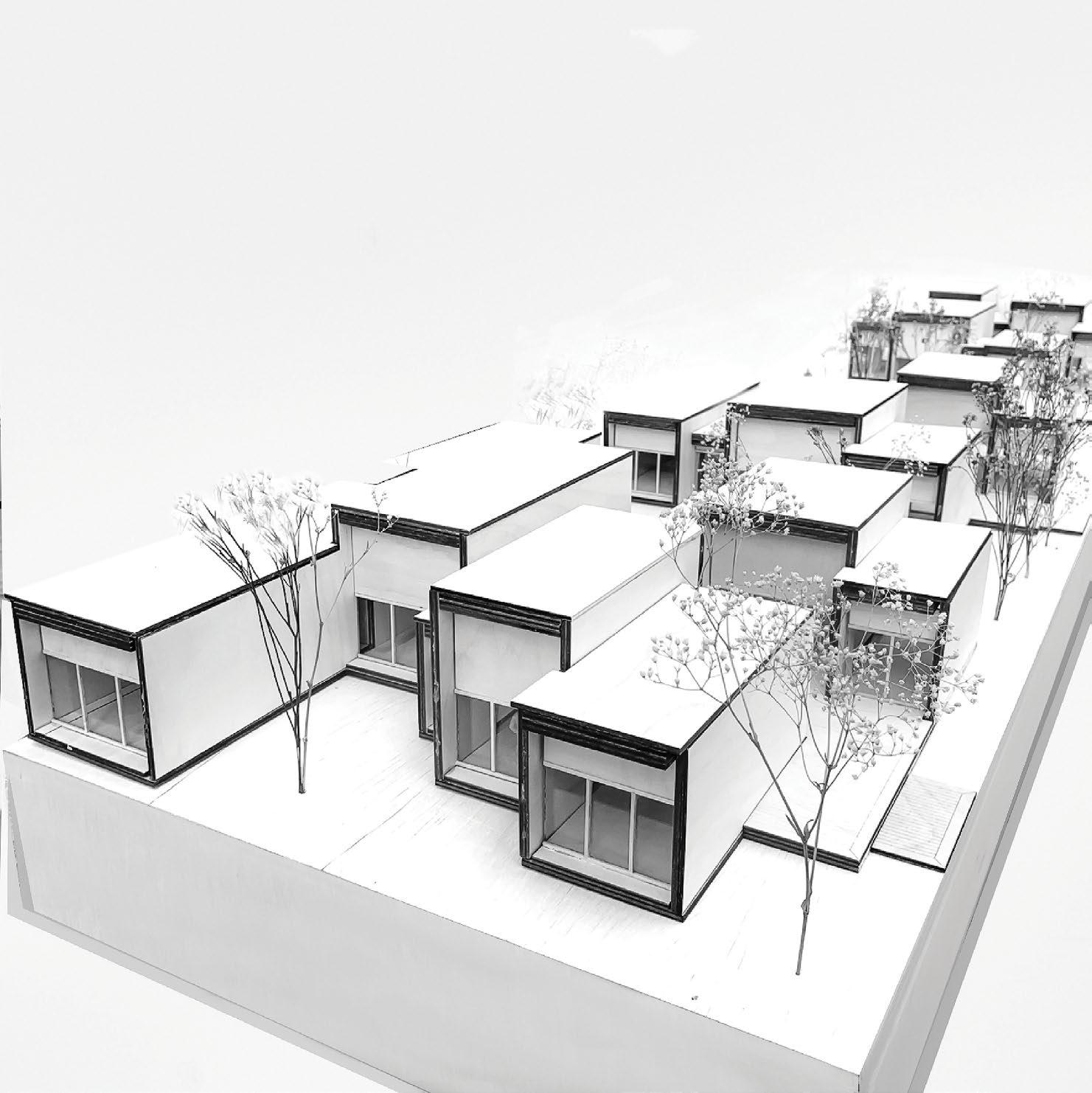

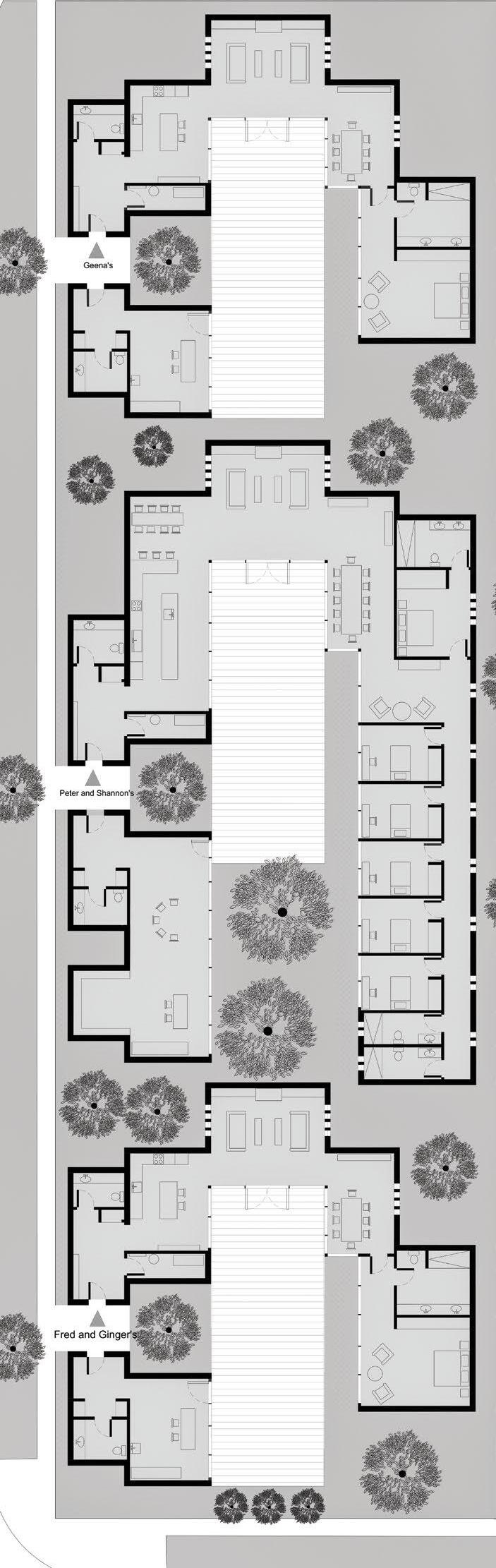

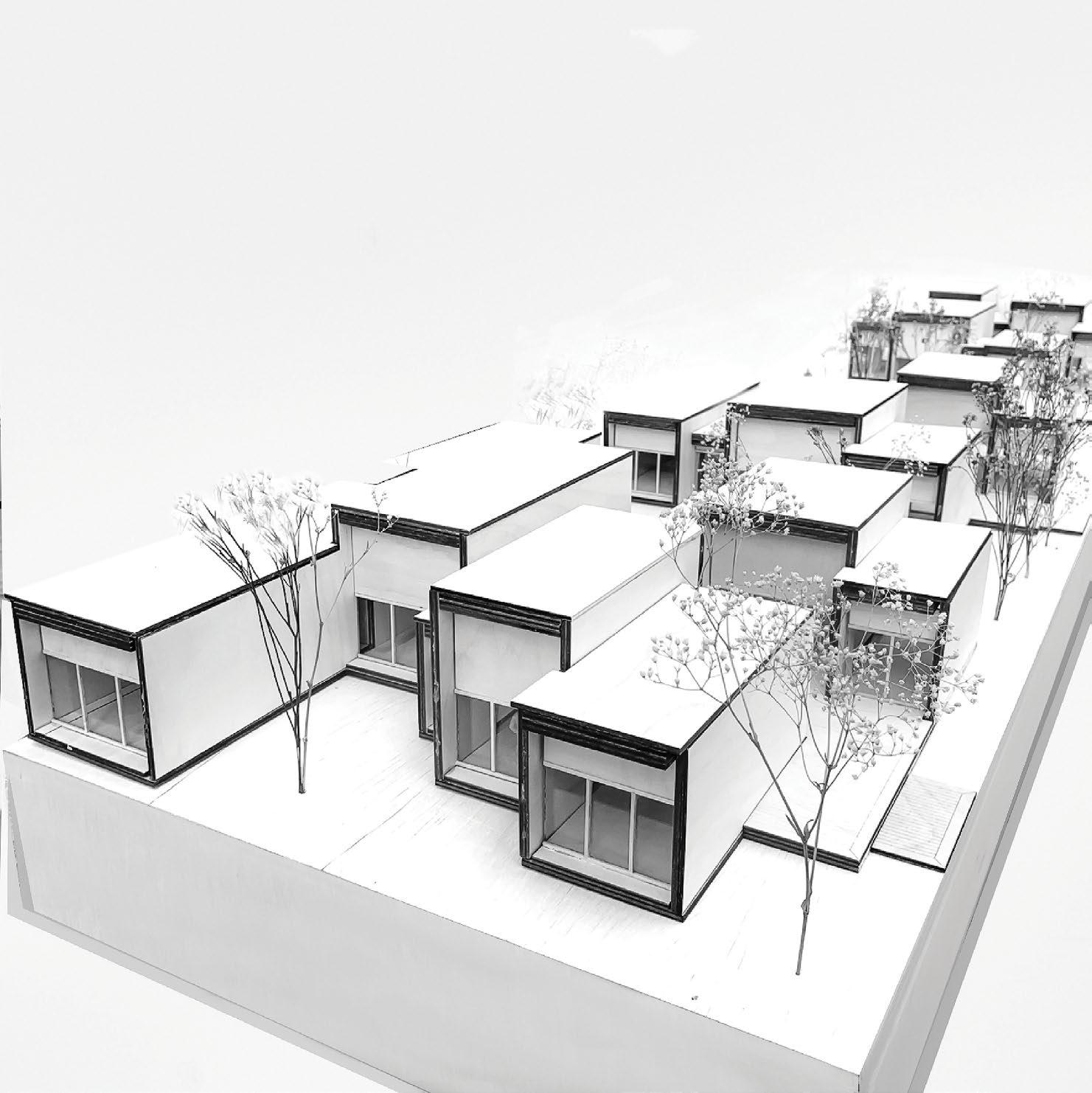

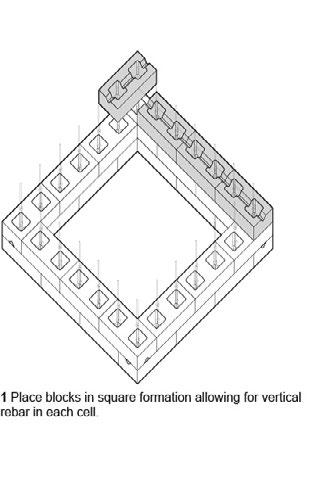

Can architecture foster neighborliness? Buffalo is commonly known as the City of Good Neighbors, thanks to its tightknit communities and neighborhoods. This graduate design studio, the first of the 3.5-year Master of Architecture track, asks students to engage in a formal exploration of individuality and collectivity in a neighborhood setting. Working at a domestic scale that links the unit with the complex, students reflect on the social implications of the built environment through an iterative design process. For most students, this studio is the first approach to architectural design.

In this framework, “Good Neighbors,” introduces students to critical thinking on fundamental architectural issues through the design of three houses for three specific families. The studio brief indicates that these families share an undivided lot in Buffalo’s East Side. Student proposals also include three workspaces for painting, writing, and music composition for one member of each family. These workspaces are to be independent of the houses.

Connections can be spatial but not physical. The studio focused on the exploration of space, place, program, light, material, and function, among others.

In order to develop design skills, the studio prioritizes model and graphic content. Each student is given the ability to find the elements of the discipline that resonate with them and carry those with them to subsequent semesters. Through production and discussion, studying architecture becomes a way to understand and uncover spatial sequences.

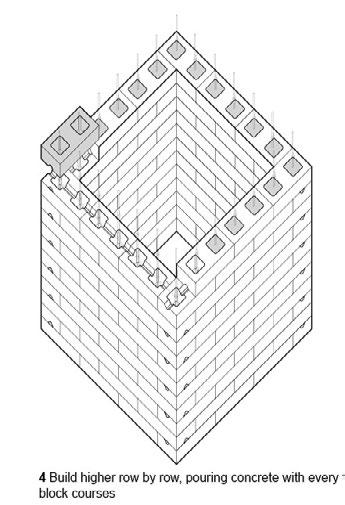

INHABITING MASS

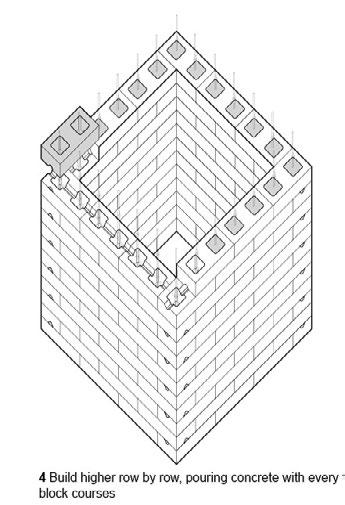

Excavating soil is frequently a byproduct of building construction, often resulting in serious environmental consequences. This project seeks to eliminate waste by incorporating excavated soil into the construction of rammed earth walls, standing four-feet wide to increase passive insulation and a net-zero

approach. Inhabiting mass in these houses promotes a more responsible way of life, reflecting a greater sense of care for the environment and minimizing energy consumption.

Window openings are carved out in the mass to direct views and natural light, while interior walls are carved out to allocate storage, bathrooms, and kitchens. Inward sloping roofs help collect rainwater into the atrium following the impluvium tradition.

16

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

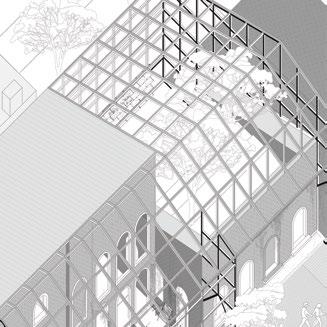

17 Axonometric, Inhabiting Mass

Ground floor plan, Inhabiting Mass

CORE YARDS

Core Yards reflects on the need for privacy in residential backyards, considering them as extensions of the home. Studying the prevalent domestic architecture in the area, the design identified a pattern emerging from the procession of back-to-back houses. While an efficient use of space, the traditional location of the backyard means neighbors are sharing the space, separated only by a figurative lot line, and lacking privacy.

In contrast, this project positions building volumes in a U shape to embrace a central core-yard, staggering a series of smaller volumes around with different domestic programs. The outer shell becomes a barrier that protects the privacy of the core-yard space, which remains intimately related to the house it serves. The workspaces that complete the program interact with core-yards and houses, the deck serving as a plane of relations with the surrounding living spaces.

“The whole studio revolved around being part of a community. For my partner and me, a large part of the process was having an open dialogue about the direction of the project. This process allowed us to distill what being a community member meant to both of us.

- James Metzger

18

Ground floor plan, Core Yards

Model photo, Core Yards

Model photo, Core Yards

SHIFTING EDGES

The design of physical transitions from room to room within the domestic space accentuates the home living experience. Looking to promote this transition, Shifting Edges scales volumes and locates openings strategically to guide residents by the shifting walls.

The flow of functionality in daily activities determines the allocation of the rectilinear volumes. With floor-toceiling North-South facing windows,

interior lighting shifts constantly throughout the day. The different geometric forms deliver a functional and unique architectural experience. As the project reaches its site boundaries, the shifting edges of human lives start and continue to the story of shifting in another realm.

19

Ground floor plan, Shifting Edges

Model photo, Shifting Edges

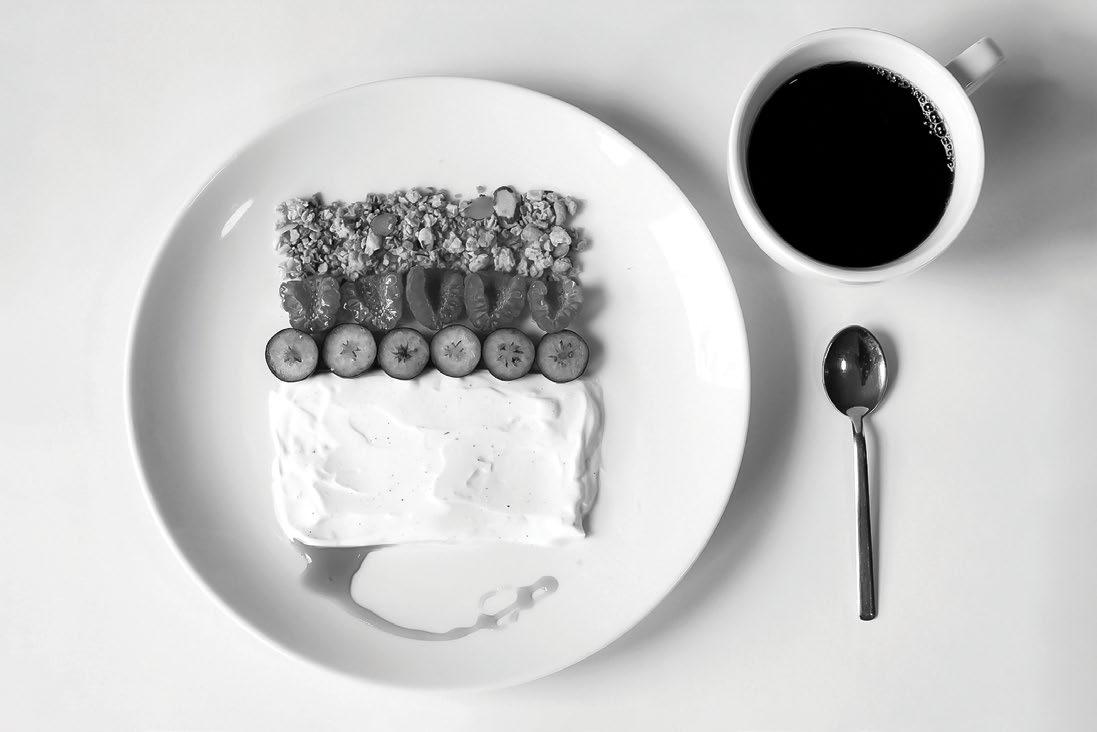

ARCHITECTURE, CITIES, & FOOD

Student:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Andrew Griffin Daniela Sandler

Fall 2022

ARC489/589

BS Arch, BAED, MArch, MUP

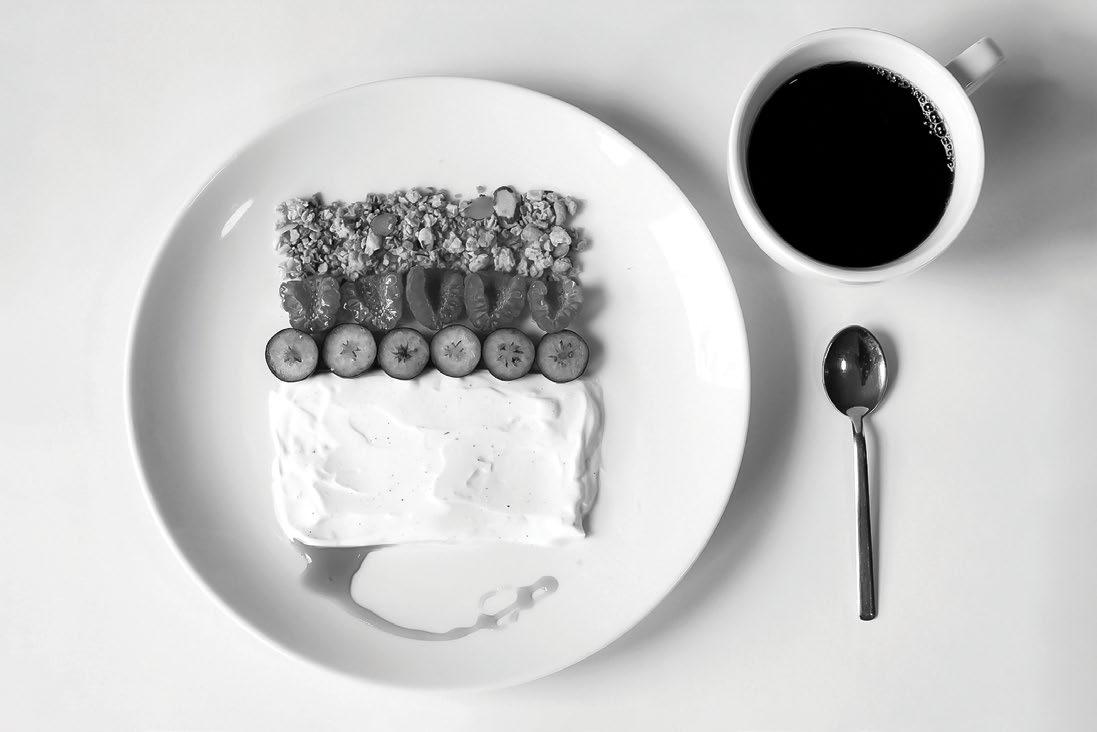

How does an architect build a sandwich? This seminar course investigated the relationships between food and design, and the logistical infrastructures that condition them, such as the mechanisms of presentation, distribution, and consumption. Focusing on the historical and contemporary architectures of food, both as spatial artifacts and processes, students explored how food has impacted the organization of buildings, public spaces, and cities. This knowledge set up how students engaged in contested forms of artistic expression and sociopolitical provocation.

Students relied on Buffalo as the primary research site, seeking compelling intersections between food and the urban environment. The city’s food inequalities became a primary topic of critical discussion, centered around themes of access, quality, and “food gentrification.” Students then reflected on how these disparities could be addressed at different scales.

The first assignment of the course was to provide an architectural take on food. Students were encouraged to draw on any previous studio experience or references from their field. Andrew Griffin’s work was inspired by, Cooking in Progress, a documentary about the world-famous chef Ferran Adria, and the use of molecular gastronomy. Inspired by the dishes served in the documentary, Griffin curated a series of images expressing the relationship between plating and presentation, comparing the mind of a chef and the mind of an architect.

“In any course, presenting any kind of work, being very specific and clear in the layout and arrangement of your work can be so critical in getting your ideas across. The care you take in displaying the work, whether the subject is food or a building, is almost of equal importance to the content itself."

- Andrew Griffin

Through pairs of images, Griffin compared his ordinary dishes, as he would prepare them daily, with the same dishes prepared in a more artful manner, exploring the aesthetics of everyday life through food.

20

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

21

Building (left) vs Architecture (right)

Sustenance (left) vs. Gourmet (right)

Mundane (left) vs. Fascinating (right)

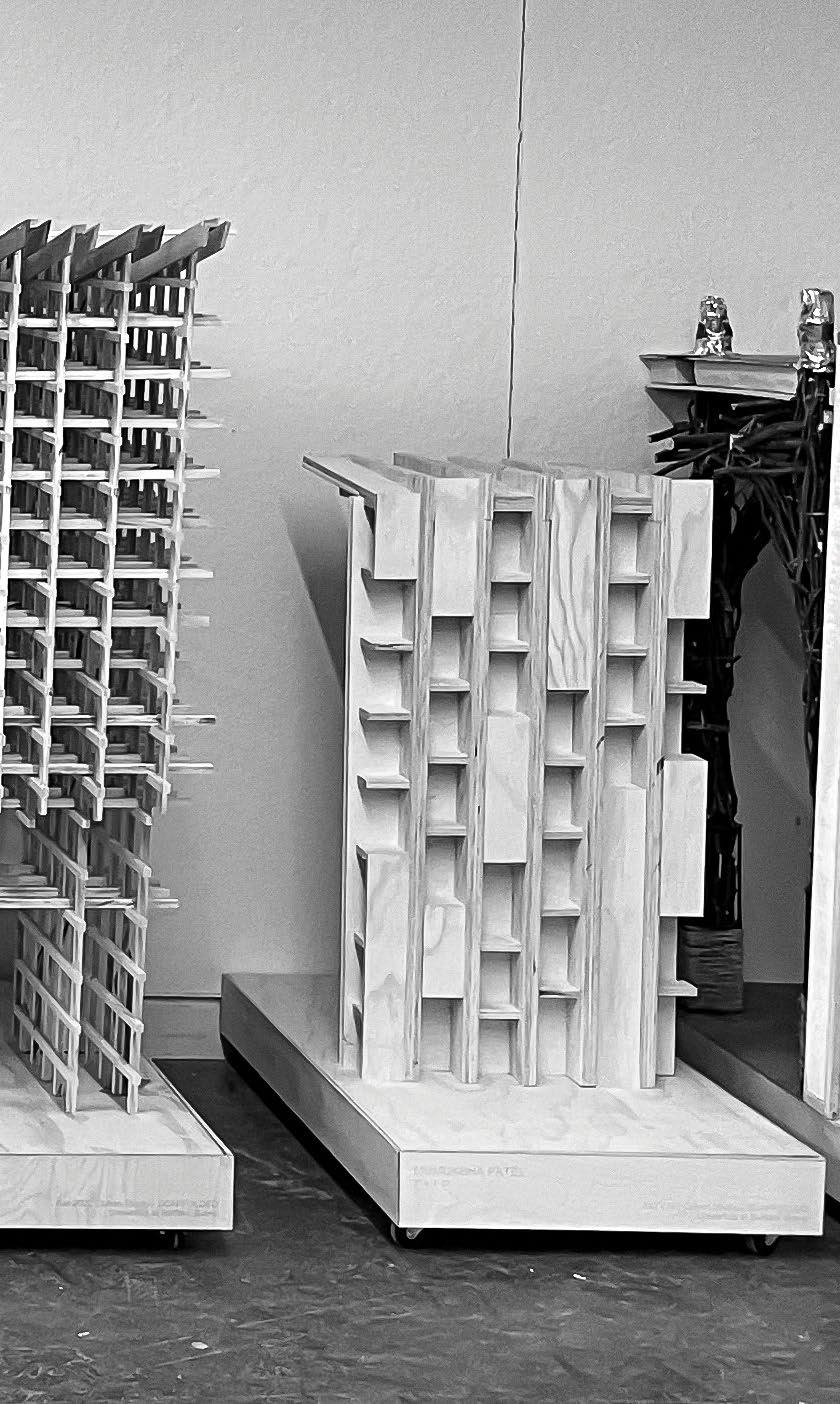

DECARCERAL ARCHITECTURE

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Katelyn Broat, James Dam, Diana Genao

Charles Davis II

Spring 2022

ARC606, Inclusive Design Graduate Research Group

MArch

How can architects help shed light on the structures and processes of mass incarceration? This Inclusive Design Graduate Research Group studio addressed this question by investigating historic and contemporary forms of mass incarceration in the United States. Prisons are ultimately material articulations of power and surveillance. Dissecting these formations through case studies, students learned how the logic of power and surveillance extends well beyond the prison. Without the counterforce of rehabilitation, there is little room for connections necessary to link the incarcerated to the outside world—a significant handicap exacerbated by how society views its inmates.

Based on precedent research, students worked in groups to break down how each case study represents a common typology of prison design: Eastern State Penitentiary, Poston, Arizona Japanese Internment Camp, and the Chicago House of Corrections (The Bridewell). The studio asked students

to reflect on ways to replace the programmatic functions of modern prisons—spaces of containment and punishment to—spaces of containment and punishment—with a network of social services. Through open forms of student-led discussion and design exercises, they identified strategies to alleviate the need to imprison people due to non-violent criminal behavior in low-income and underserved communities.

The Chicago House of Corrections (Bridewell), known for its cell house organization and inmate labor practices, was the focus of study for one group. This correctional facility was sectioned off by quarters, with women segregated to the west wing and men in the north and south wings. The men's cells are placed in the center of the room with mezzanines wrapping the cell block. With such a configuration, inmates are restricted from seeing one another, leading to highly problematic social consequences.

Students began by questioning the role of a single cell – could it be designed or reconfigured for healing instead of punishment? For protection rather than separation? Students produced architectural proposals from these perspectives, generating new cell blocks and configurations, and discussed their potential for transforming how they might affect the lives of the incarcerated.

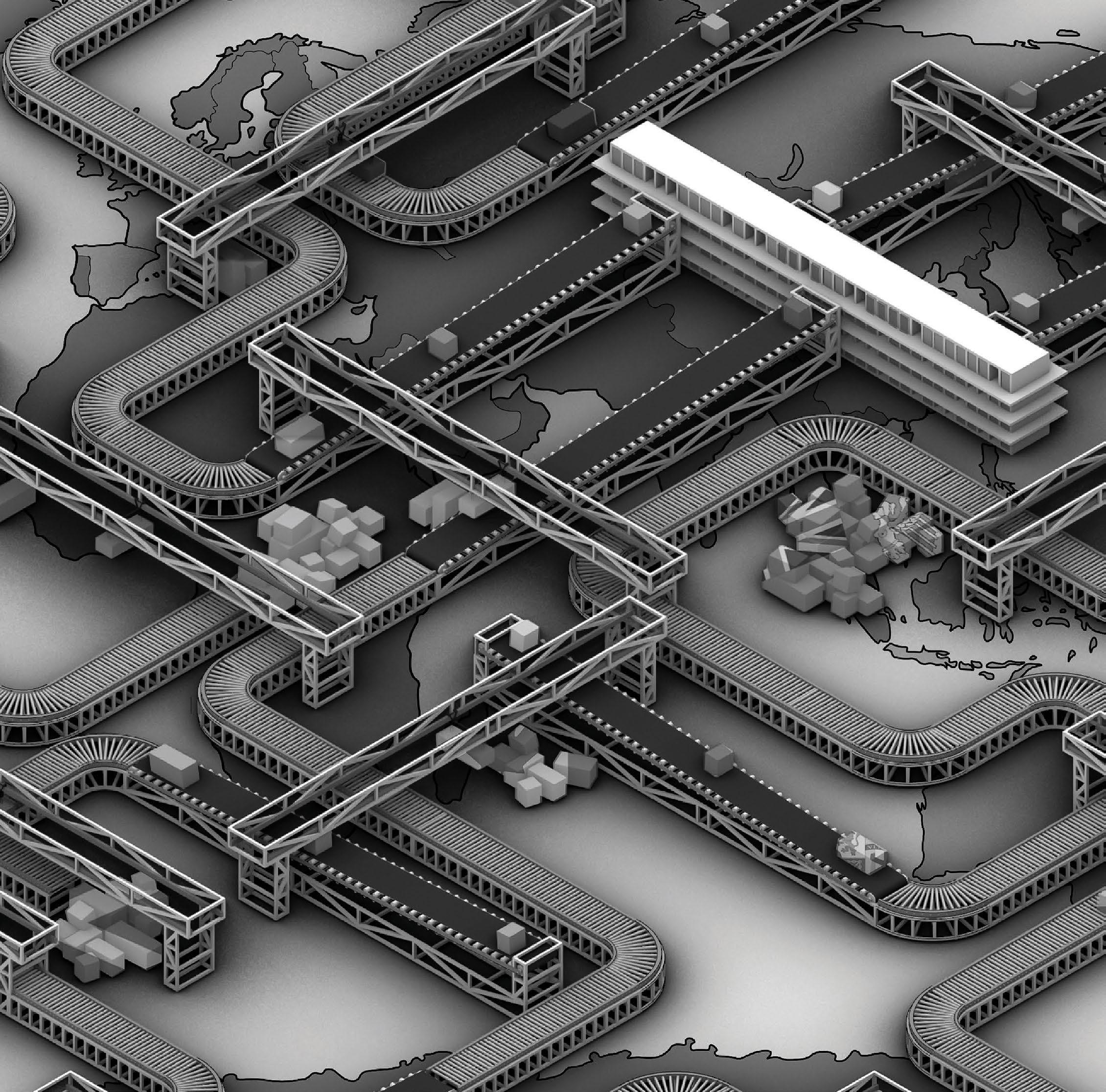

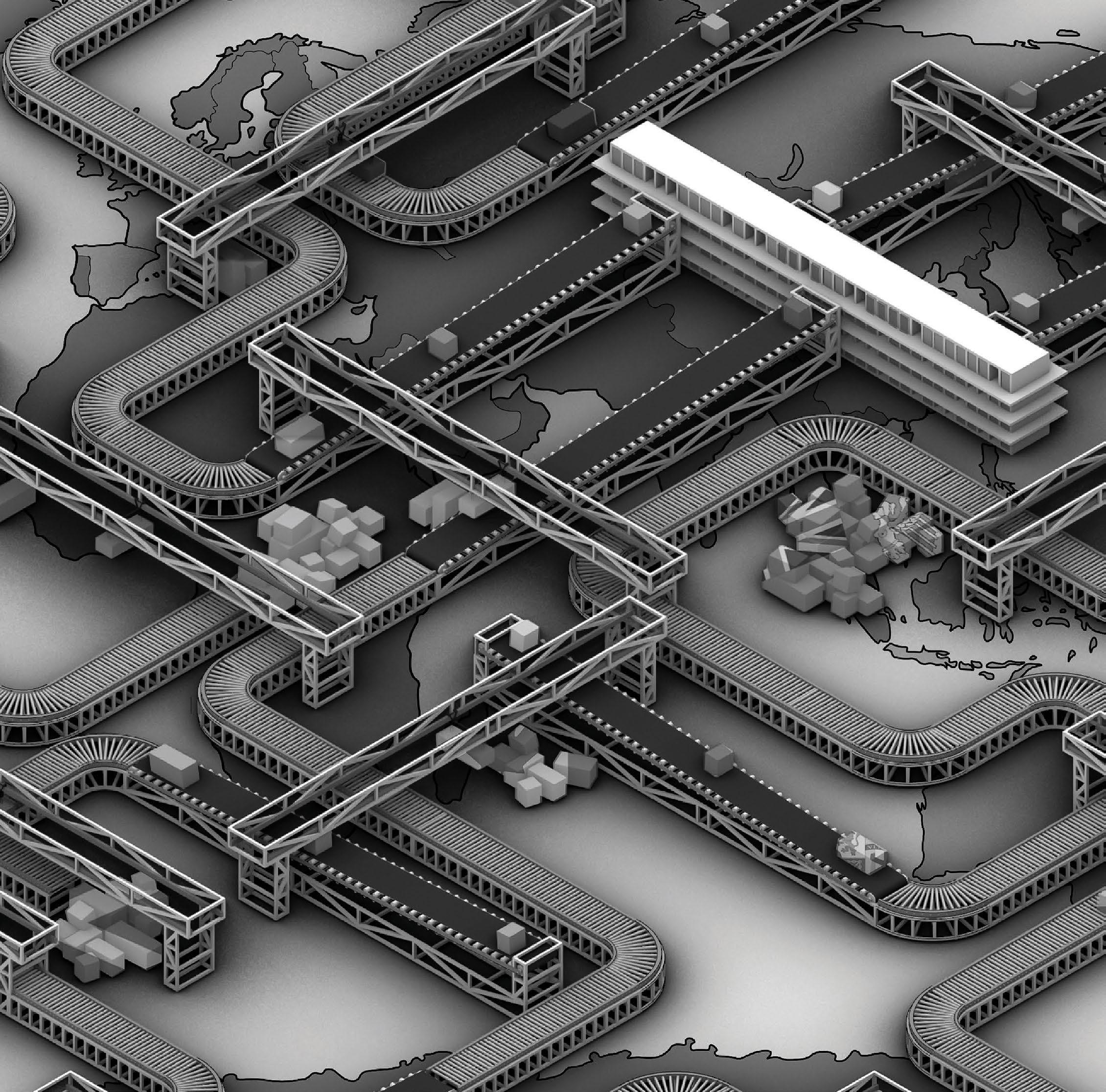

Based on the precedent study, Broat asked how forms of incarceration impact the cultures and identities of prisoners. Broat then transformed the cell block's architecture into a conveyor system that could transport inmates, abstracted as boxes within their cells.

This idea forces one to think about how the industrial prison system displaces people and their families and how it strips away individuality through exploitation. The scheme posits how an architect can do plenty within a space or with a set of constraints while raising questions about the need for greater social involvement in creating healing correctional environments.

22

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

23

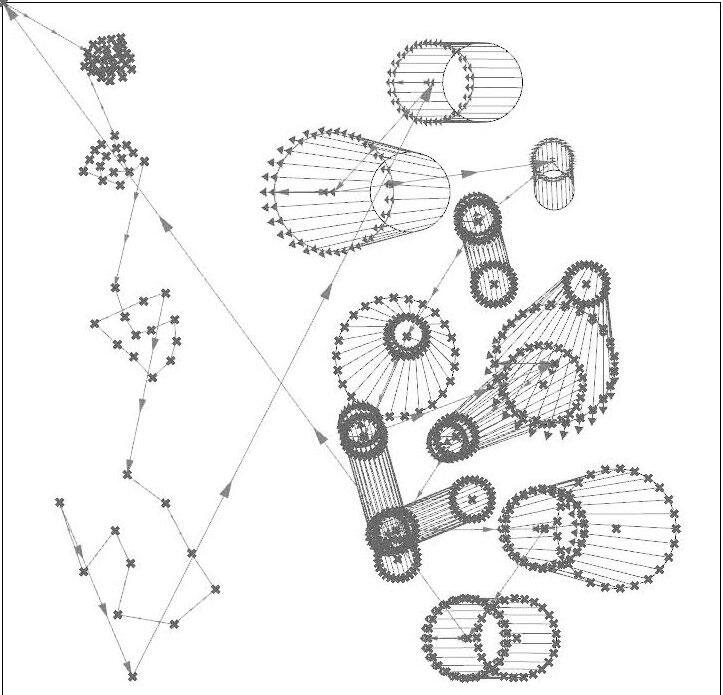

Field condition of conveyor belts, Broat

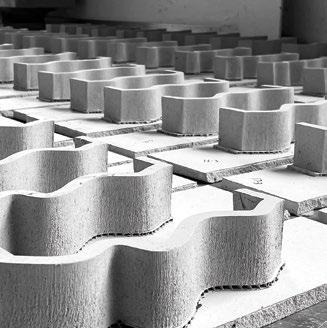

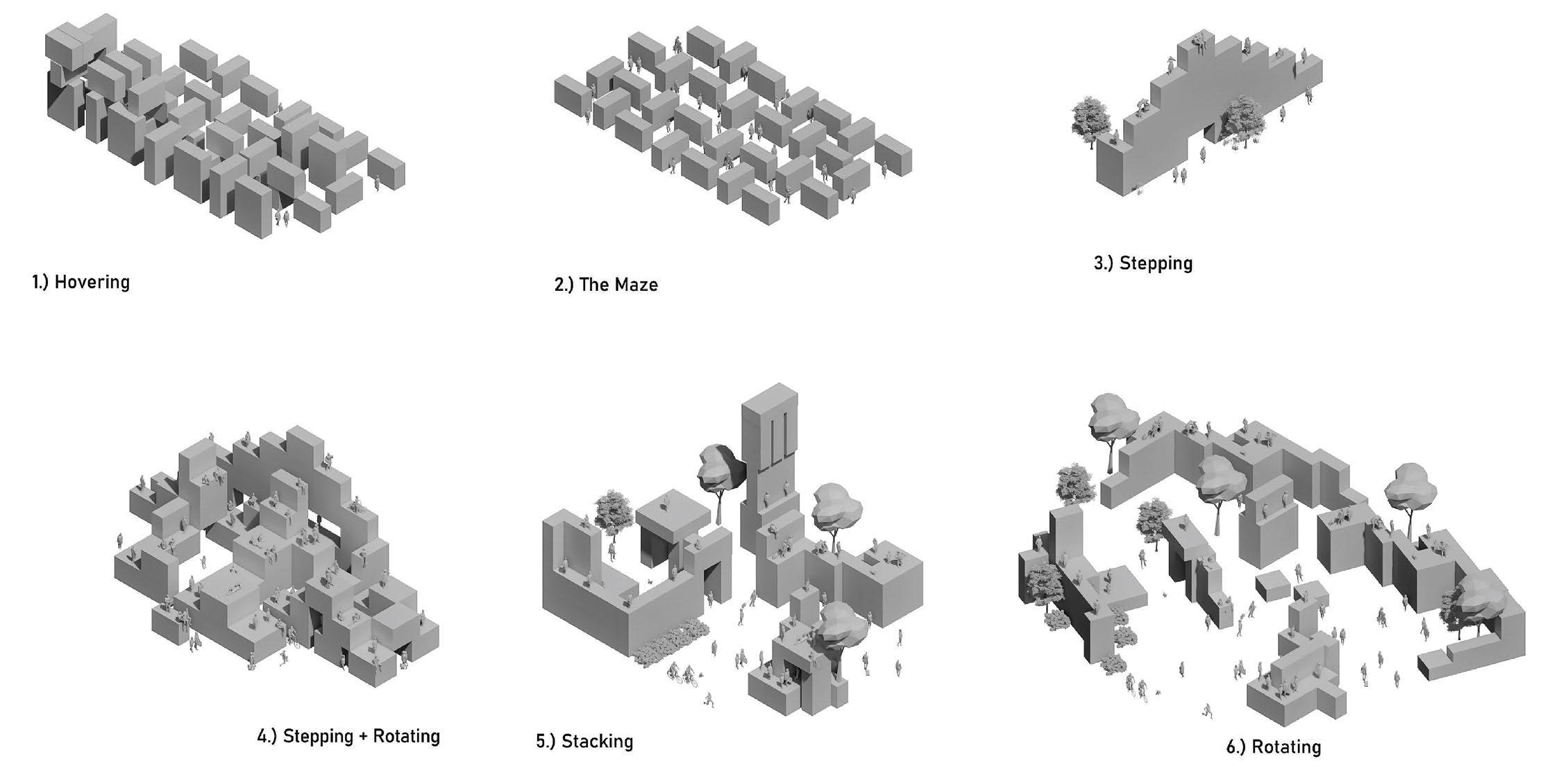

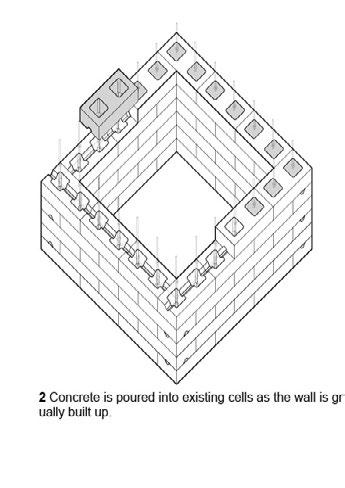

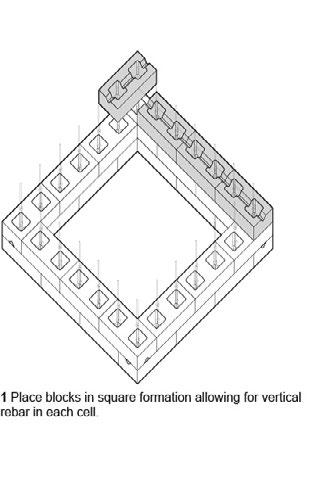

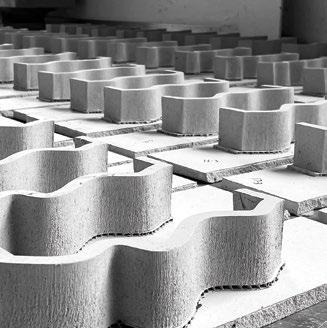

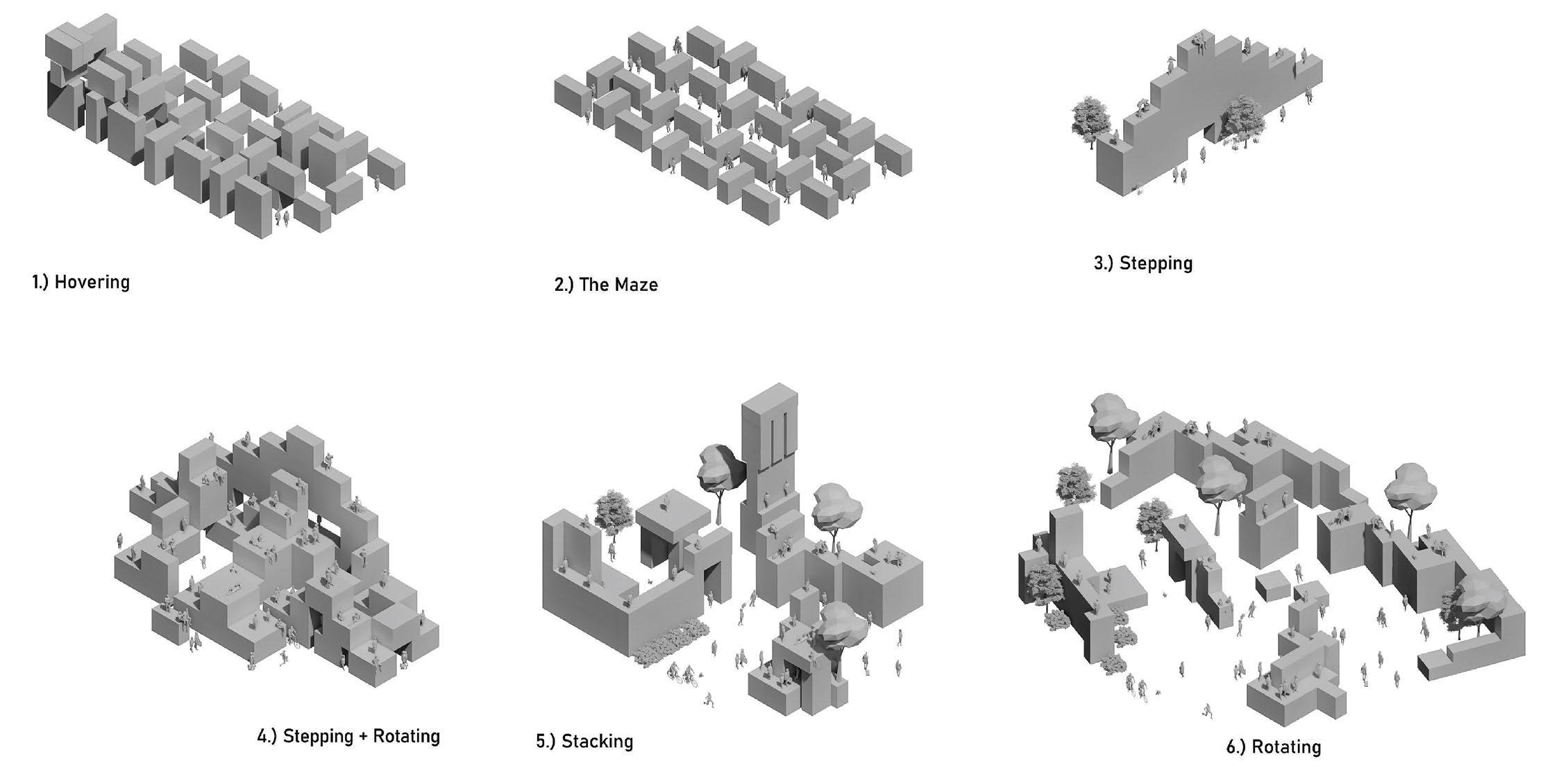

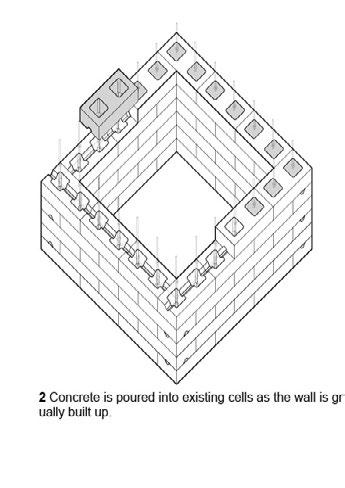

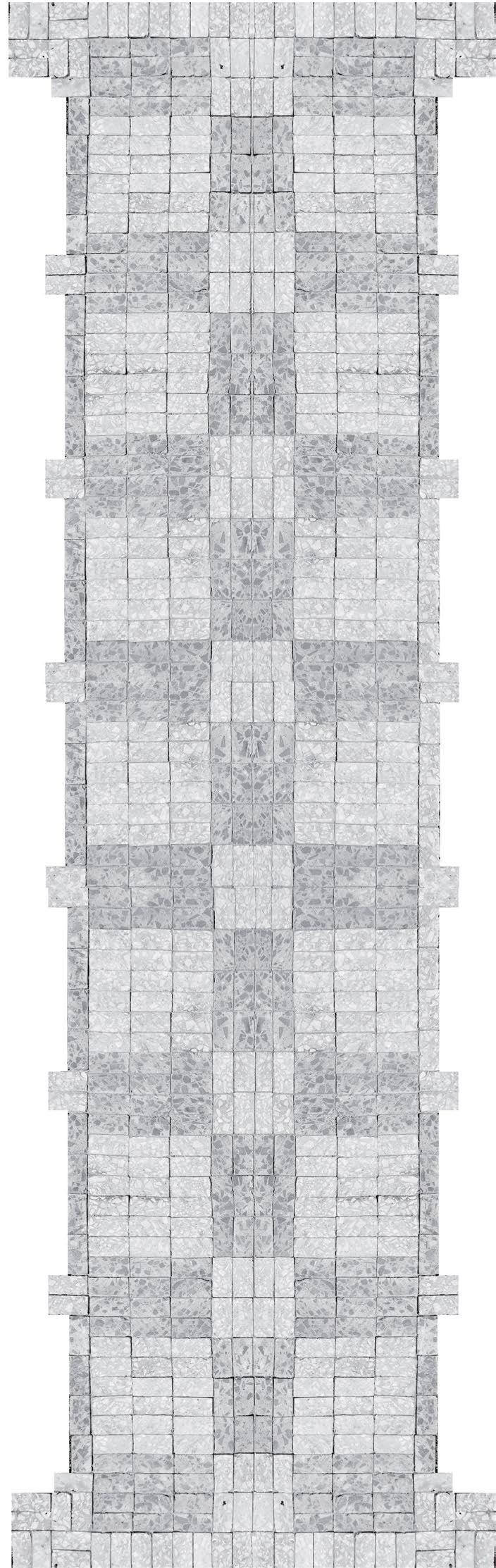

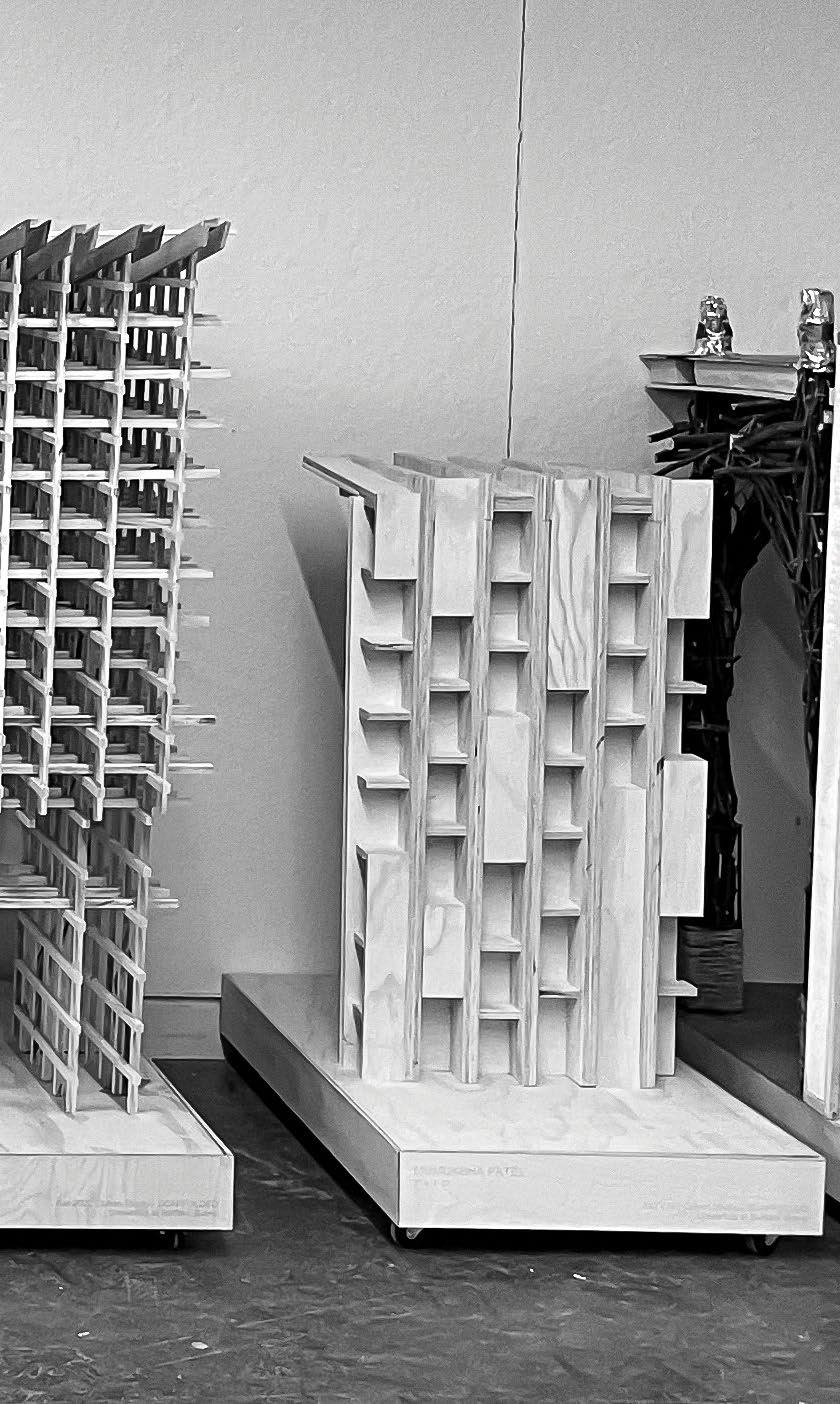

Dam explored the architectural configuration of a cell through a set of physical models that he transformed with iterative interventions. Combining the standard dimensions of a singular cell created new conditions to be aggregated. The assemblages speak to how a cell block can be constructed and then deconstructed to form a base module, creating an ever-expanding condition that can replicate and fulfill any need.

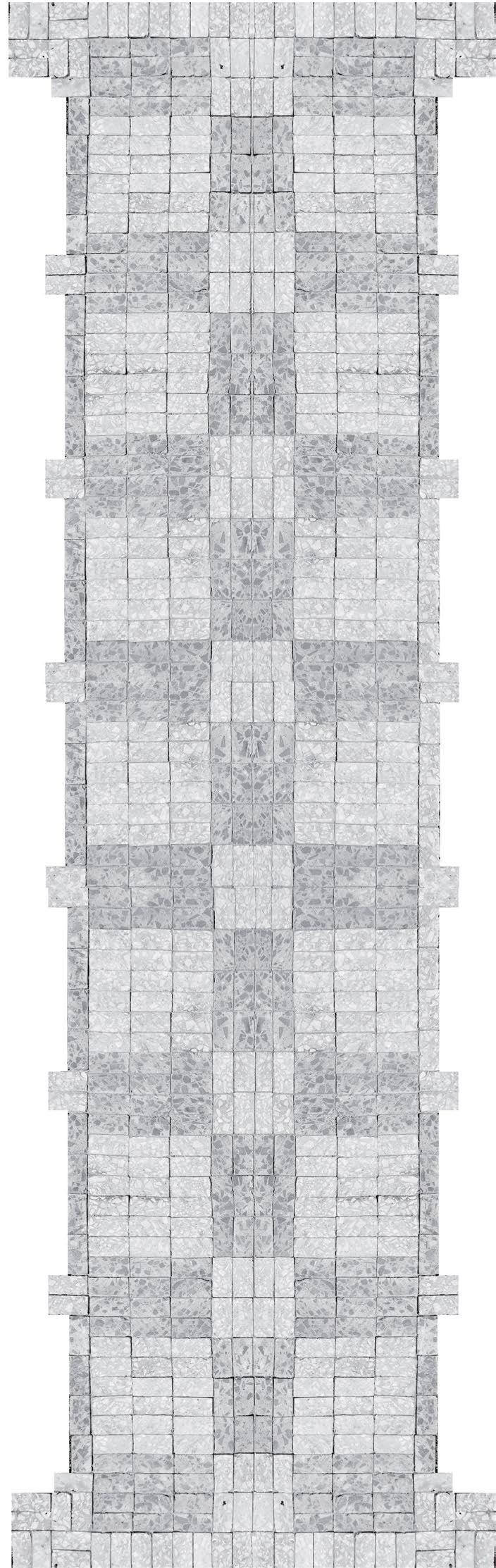

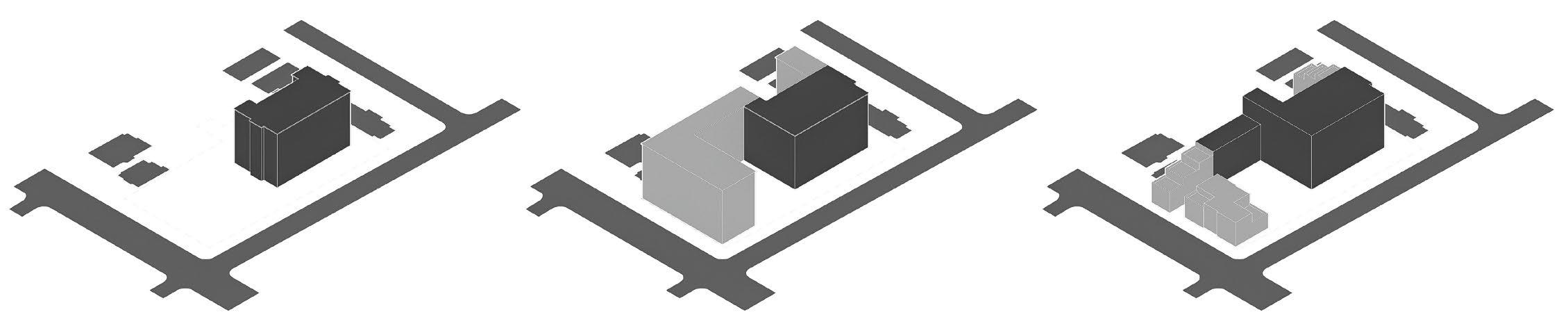

Also starting with the existing carceral typology, Genao focused on the movement of spaces created by cell blocks. Her idea conveys how cell blocks can be manipulated, rotated, stacked, and arranged to serve distinct purposes. In this case, separation is replaced with a collective community.

Each approach changes the orientation and placement of a cell, resulting in a series of unique conditions. The final illustration shows the endless arrangements that can be made with the same blocks to foster a different culture than the one currently in effect.

As students gained a deeper understanding of the course material, they constantly questioned their

opinions and positions on the prison system. While designing their scheme, they were pushed to interrogate whether they wanted to maintain, reform, or abolish it. What is an architect's role within the system? Why should an architect care?

24

“As a designer, I have limitations and cannot independently create a solution... Rather, I can bring attention to what is existing and explore distinct alternatives.”

- Diana Genao

Model photo of cell base modules, Dam

An ever expanding condition of cell blocks, Dam

25

Cell evolution, Genao

Cell block arrangements, Genao

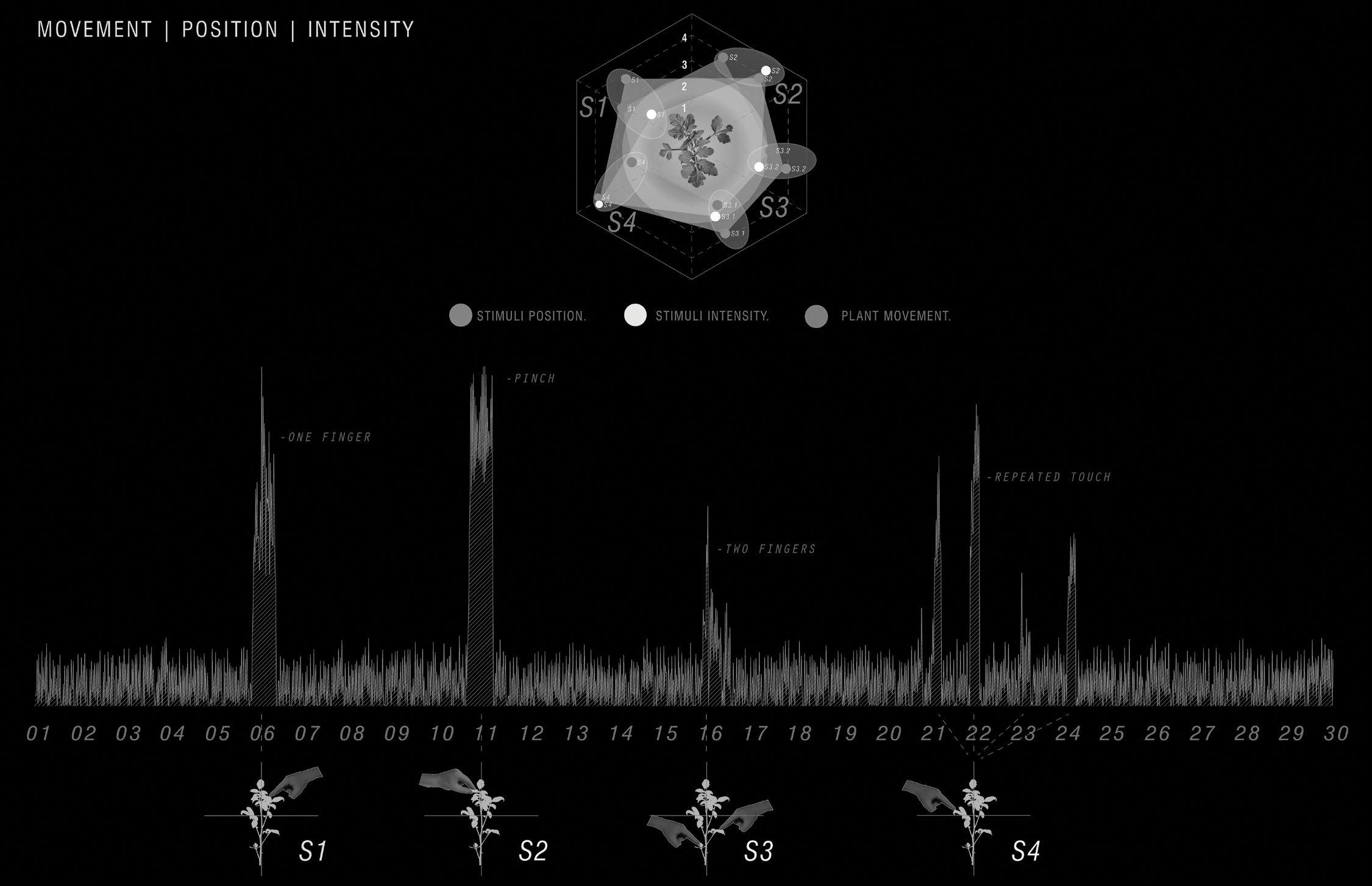

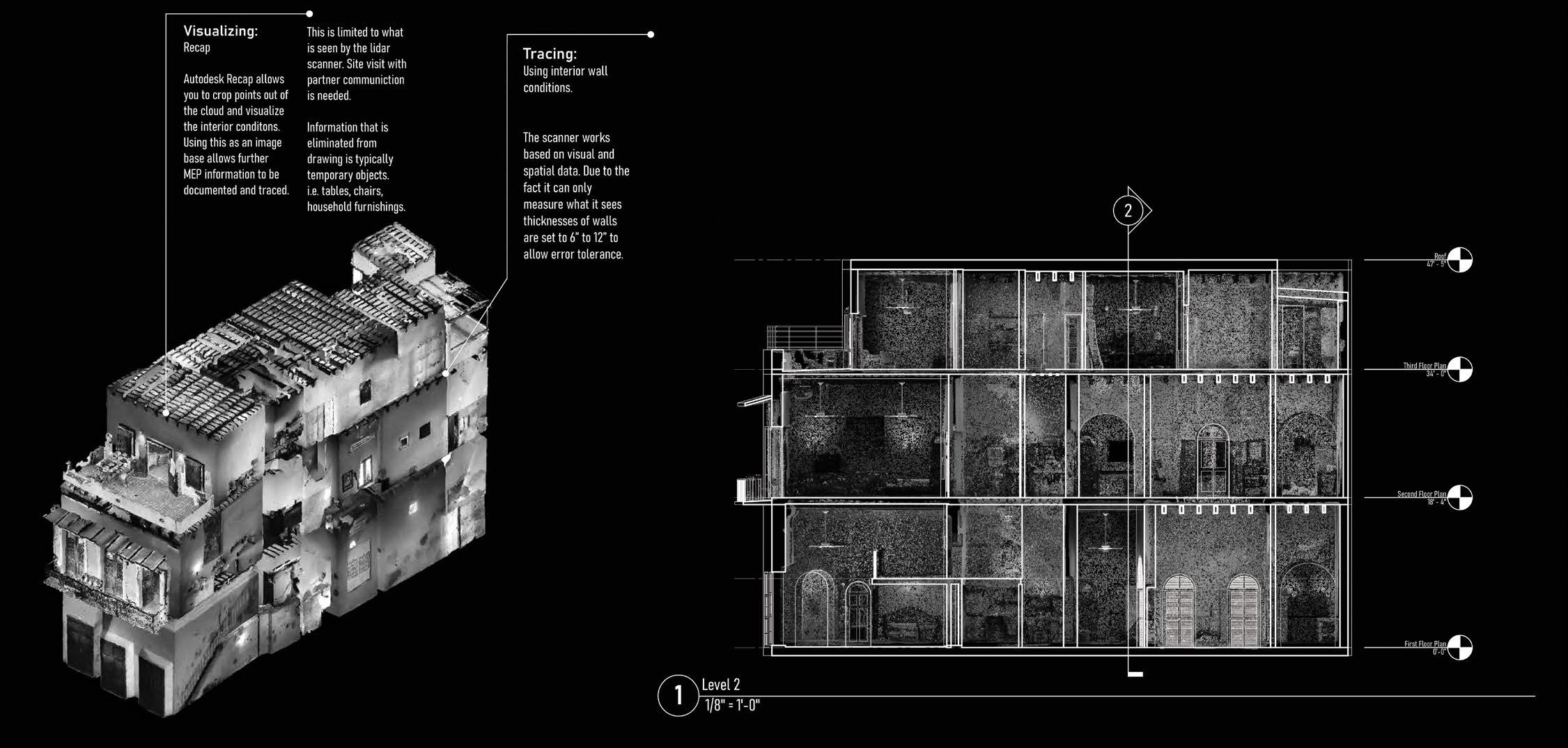

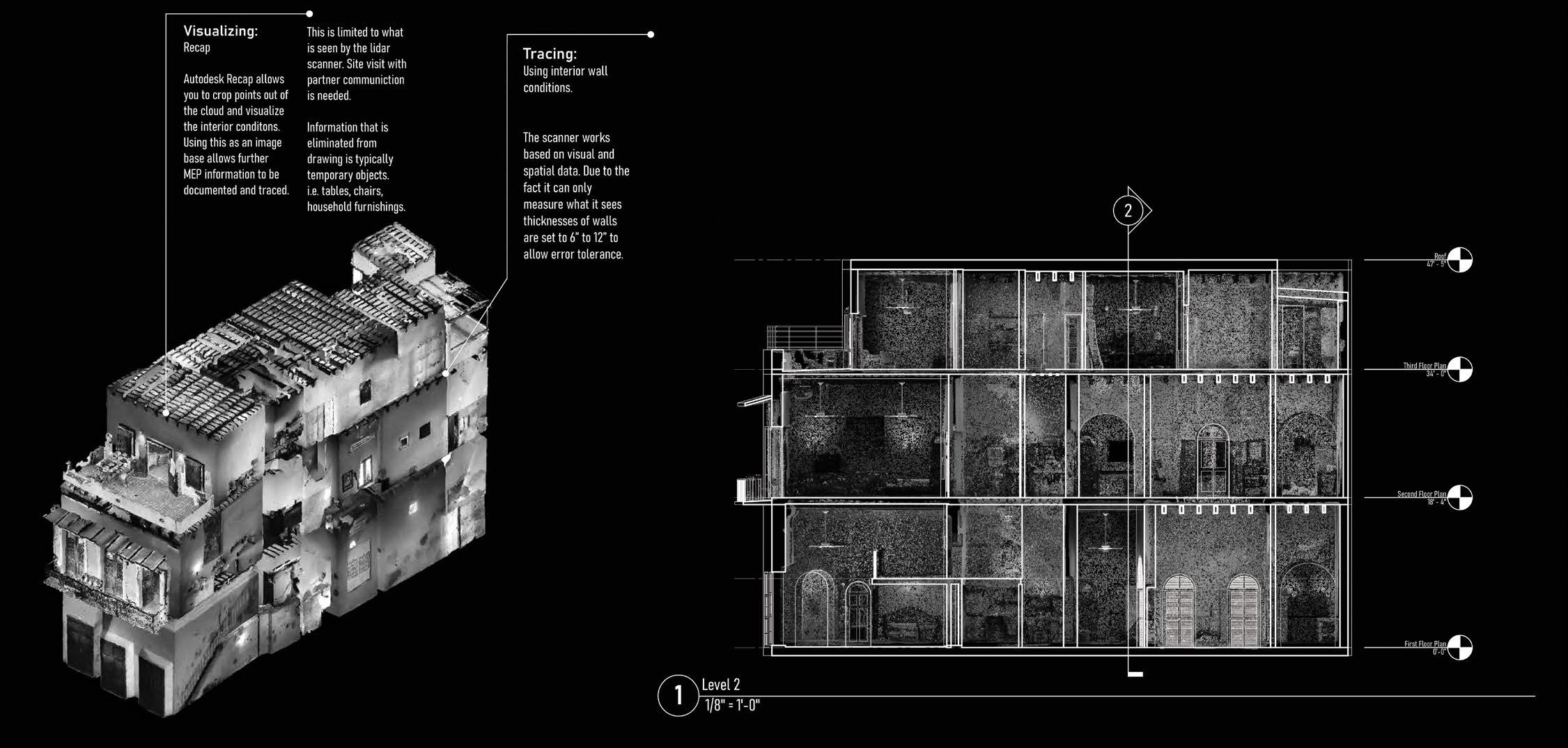

SITUATED TECHNOLOGIES

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Adrian Cruz, John Mark Nachbar

Nicholas Bruscia

Spring & Fall 2022

ARC605 & ARC606, Situated Technologies Graduate Research Group

MArch

How will immersive technologies transform human experience and spatial practice? The Situated Technologies Graduate Research Group—concerned with exploring the intersection of emerging technologies, space, tectonics, and culture—reflected on this question with two complementary studios in Spring 2022 and Fall 2022, focusing on the use of extended reality (XR) technologies, an umbrella term for virtual, augmented, and mixed-reality technologies.

The first studio concentrated on digitally augmented hand-crafting techniques. Partnering remotely with professionals in the rural village of Hida, Japan, students learned about the fabrication histories and technical innovations associated with the region. This work resulted in largescale chainsaw cutting of local logs, or ‘nemagari’ (bent root), using augmented reality (AR) headsets. AR processes allow for a new use of this material, as these trees grow curved due to snow load on the mountainside, making them unusable in standardized industrial

milling operations. After this phase, students experimented with hybrid digital/material workflows using XR tools. Their projects demonstrated how to use digital technologies to foster local engagement, bridging design and production.

Many students from the first studio stayed on for the Fall 2022 iteration of the studio, building on more advanced AR systems. The studio speculated on the representation of the “invisible” through augmented reality imaging in real-time, employing data-driven holograms mediating existing and proposed architectural spaces. The outcome consisted of a series of curated design installations to reveal atmospheric and/or historical specters.

PAST AS PRESENT

Nachbar’s project aimed to bring awareness and memorial to the former Erie County Almshouse and cemetery, located on the grounds of UB’s South Campus. During the transitional period of ownership between the county and university, the collective memory of this period had faded. To reflect on this history, Nachbar created a hybrid physical and AR experience that used differences in color and height to present population data related to the almshouse records.

As the user explores the model and space of the cemetery in AR space, they may draw close to a physical marker. Based on the user's proximity to the marker, a digital plaque will appear, revealing the age, nativity, sex, and occupation of an individual that would be representative of the almshouse population at large.

26

OUR WORK OUR WORLD

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR

27 Digital representation memorializing those who passed away, Nachbar

28

Collage of the Salton Sea’s last surviving community, Cruz

Sequence of hologram captures, Cruz

CONVEYING TWO REALITIES

Cruz’s concept conveyed past and future realities using collage drawings and occluded “found” objects. The occluded objects acted as portals that distorted the studio space and the drawings. Cruz’s research was sited at the Salton Sea in California – an artificial lake that came into existence through an engineering fiasco at the beginning of the last century.

Using the Light and Space Movement, an art movement from the 1960s

spearheaded by artists like Robert Irwin and Helen Pashgian, geometric shapes and abstraction affect how the viewer perceives the project. The resulting installation pulled the context of the studio space into an AR demonstration.

Nachbar and Cruz’s work serves as a testament to how architectural thinking constantly evolves. These piloting studios are focused on developing new curricula focused on extended reality, which the Department of Architecture has supported via the Formworks

funding initiative, a grant program that supports transformative research.

“The studio developed a sense of mutual respect for each other, evident in peer-to-peer technical support and feedback, empathy and emotional support, as well as a studio culture of good humor."

29

Perspective collage, Cruz

Demonstrating how occlusion distorts the studio space and drawings, Cruz

- John Mark Nachbar

Students:

Faculty:

TAs

Term:

Course:

Program:

Students of ARC101

Korydon Smith (coordinator), Seth Amman, Adam Thibodeaux

Ana Alarcon, Rocco Battista, Briana Egan, Andrew Gunther, Alec Harrigan, Matthew Kinnally, Serena Minix, Michael Napier, Ainish Sheth Fall 2022

ARC101

BS Arch

How can a single design move determine lighting, entry, circulation, and still create a powerful space?

ARC101, the first design studio in the undergraduate curriculum, introduces students to a world of iterative design processes, methods of making, and intellectually stimulating conversations. It is also where students meet the people they will travel the gamut of their architectural education with, whom they will learn to care for and support. Forming these connections is perhaps the most critical part of ARC101.

Emerging from a high school environment, the first semester of college has a steep learning curve as students adjust to a new style of instruction. Students travel from class to class as a collective rather than in small cohorts. Lecture-driven learning takes a back seat and is replaced by vibrant, collaborative work sessions.

Architectural Design Studio 1 set up a datum for students to begin thinking logically and creatively about their

ideas and craft. Through an iterative process of making, analyzing, and discussing, learning through making mistakes and creating a mess was encouraged. Beginning from day one with peer learning and hands-on explorations, ideas of space-making were explored through the creation of physical objects.

In tune with the theme of spacemaking over shape- or form-making, Project 1 asked students to use one operation to create a clearly bounded

space of repose with an entry/exit, views out, and indirect light. These explorations were initially explored through chipboard boxes. As ideas developed, boxes became unique volumes and an ordering system that kept the ideas within one operation.

Project 2 took the logic identified earlier and introduced a differentiation between interior and exterior spaces of repose and the circulation among these spaces. Using paper as a means to define space became a new

30

ARC101

Final Review, Hannah Ikawa RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

31

Final Review, Christian Rafferty

Final Review, Max Avrutsky

method of making. Folding, cutting, and bending gave rise to new forms previously unachievable by chipboard. As spatial sequences arose, so did the architectural proposals. Project 3 brought the chosen operations from previous work into a programmatic realm, aggregating a singular unit to create interior and exterior spaces. The semester culminated in Project 4, adding model materials wood and plaster. The semester finished with students integrating their chosen operation and aggregate system into a proposed site design and program through well-crafted models and drawings.

Throughout the ideation and product development, there is an element of ambiguity felt across the firstyear studio. While primary learning objectives and expectations are clearly stated, the journey through projectbased learning hinders can often be student-led. This process lets students find their own way of thinking, doing, and representing their work.

"Architecture is hard, and I feel like we can all struggle together while helping each other become our best selves."

- Grace Perritt

The final review for ARC101 celebrated the journey students, teaching assistants, and faculty went on together. Inviting internal faculty and external professionals to comment and converse with students on their work unearthed true passions and interests.

32

Final Review, Olly Montgomery

Final Review, Ofir Ben-Shimon

33 Final Review, Ester Rafailova

ARC101 STUDENTS & TAs A CONVERSATION

Students:

TAs:

Moderator:

Ryan Mellen, Alec Pitillo

Alec Harrigan, Serena Minix

Charlie Stevens

STUDENTS TEACHING STUDENTS

Freshmen students enter their first semester with little knowledge of architecture. Fostering a place to support critical learning is part of the reason teaching assistants (TAs) are as ingrained into the course curriculum of ARC101. First-semester students experience a rigorous freshman year program designed to help students transition from high school to advanced architectural education.

TAs work closely with younger students giving them a support system, and can make a difference in how freshmen feel valued. The intention behind organizing this conversation was to uncover how a culture of care and support infrastructure develops over a semester. Hearing from a pair of TAs and two of their first-year students illustrates how their studio was able to thrive through the “mess” of ARC101.

LEARNING THROUGH THE MESS

Charlie Stevens: Where have you seen themes of care progress during your time at UB?

Serena Minix: I would say our culture has become a lot more active and about communication, and I think that shows in our work. My generation was very shy and timid for quite a while, but then in this post-Covid world, we’re determined to come back with a force. We’re always trying to use our skills as designers to use the thought process and problem solving we were taught and given to make the world what we see it should be, and to correct some of the injustices that we used to be silent about.

Alec Harrigan: What I found, and hopefully what students are starting to see, is that in the studio some of the best advice and comments you get are actually from your classmates.

Alex Pitillo: One thing I have noticed is that now that we are designing projects people actually inhabit, the

way I think about solving problems has changed. We are starting to think about how people use space, how they interact with it, and what it can provide long after its use is done.

"It was terrifying to look at eleven, 17-19 year olds, and them look at me for the answers. I have to tell them that I do not have one, because there is not one, and that we have to find it together."

CS: How did you value the day-to-day design process, the constant back and forth discussion with TAs and your peers?

AP: I think a lot of the time I felt held back by the limitations the faculty or the project brief set. And when they said, ‘you can add stairs,’ it was kind of letting the leash off. You could get ahead but still not too far.

34

- Serena Minix

“Design is a never ending task. It is ultimately 'complete' when the time frame is up for design."

- Alec Harrigan

CS: How were you all able to form your own version of “studio culture?” Given how our regular studio space, Crosby Hall, is under construction, was it hard to get acquainted with one another when the entire class is split up into much smaller rooms?

AP: Being in a small group kind of forces you to get to know each other, share ideas, and take a look at other people’s work to see what they’re doing.

Ryan Mellen: Shoving other people’s papers out of my space or sweeping

around other people’s desks forced us to not only to look at each other’s work, but also to form relationships like, ‘Hey, I need you to get your garbage out of my space.’

CS: How did you all, as a studio, navigate through all the challenges (adapting to a new lifestyle, the workload, learning a new practice) that come with ARC101?

AH: Right away there were no really big challenges. It was more of making sure there was consistent understanding of the prompt. One

way I got through these challenges was looking to Serena (studio TA partner) for help. Working with the students and going through those design iterations was difficult at times, but worth it in the end to see their growth.

RM: The studio started to get really tough around final review time because it was then that I realized there really is no end to the design process. That was kind of a horrifying and existential realization for me.

35

TAs

for final review

and students gathered

CS: What was it like to learn as firstyear students, as well as teach as first semester studio TAs?

AH: Definitely equal parts terrifying, but also way more rewarding than anything else. It was rewarding seeing students work through and seeing the love for architecture blossom.

SM: For me, teaching comes weirdly easy. In this situation, I got to look back on my years of experience at UB and correct what I felt was wrong. Making sure not to give students graduatelevel knowledge when they’re only on year one. I think the hardest thing for me was trying to keep the good stuff for the good times. There are better lessons we learn through doing rather than being told.

AP: The fact that you two were so great at two different things was great. Those one-on-one desk crits where you would talk to each of us about totally different things was indispensable. I would not have been as successful without those.

36

“The challenge of teaching for me is how to show someone who has a design, while it might work really well and be functional, it doesn’t necessarily mean the process is over.”

- Alec Harrigan, MArch

"While I did enjoy the design process and making constant improvements on an idea, I do wish in retrospect that I had been messier in the beginning."

- Ryan Mellen

37

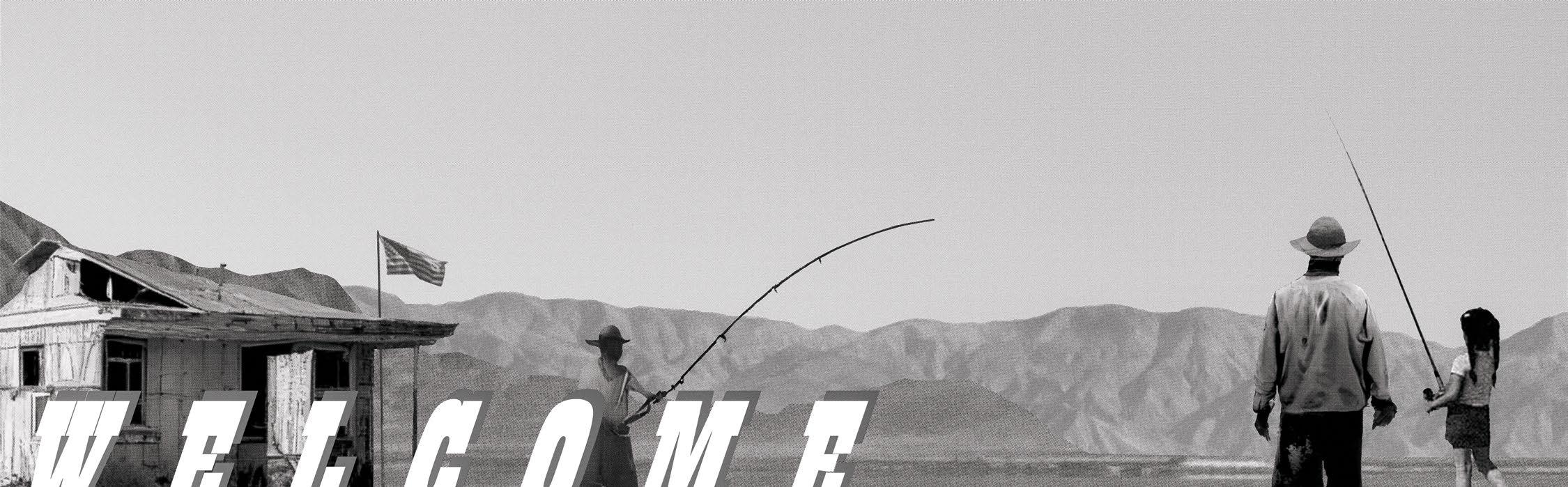

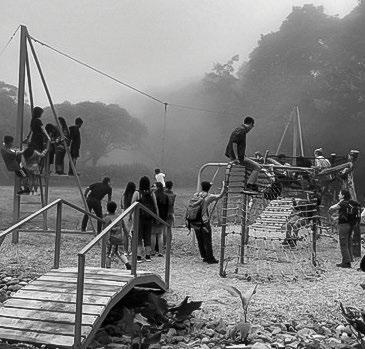

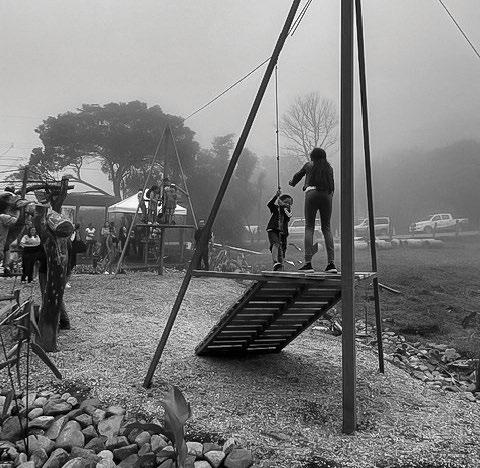

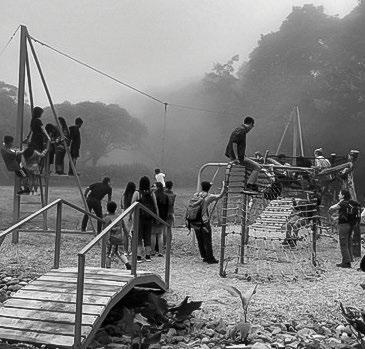

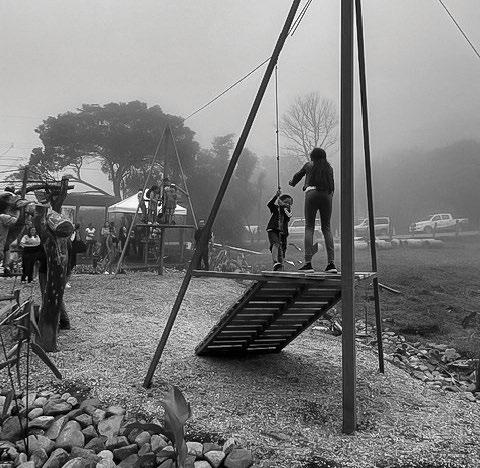

Annual freshmen boat tour of Silo City

SKATEBOARDING AND THE CITY

Students:

Farhan Alam, Kelsey Cirincione, Alex Demott, Rosangely Guzman, Daniel Ibalio, Min Hyoung Kang, Jae Beom Lee, Nick Lividini, Irene Mallano, Nick O’Leary, Jessica Pawelek, Julia Rodgers, Nick Sidles, Taylor Smith, Danny Truong

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Annie Schentag

Fall 2022

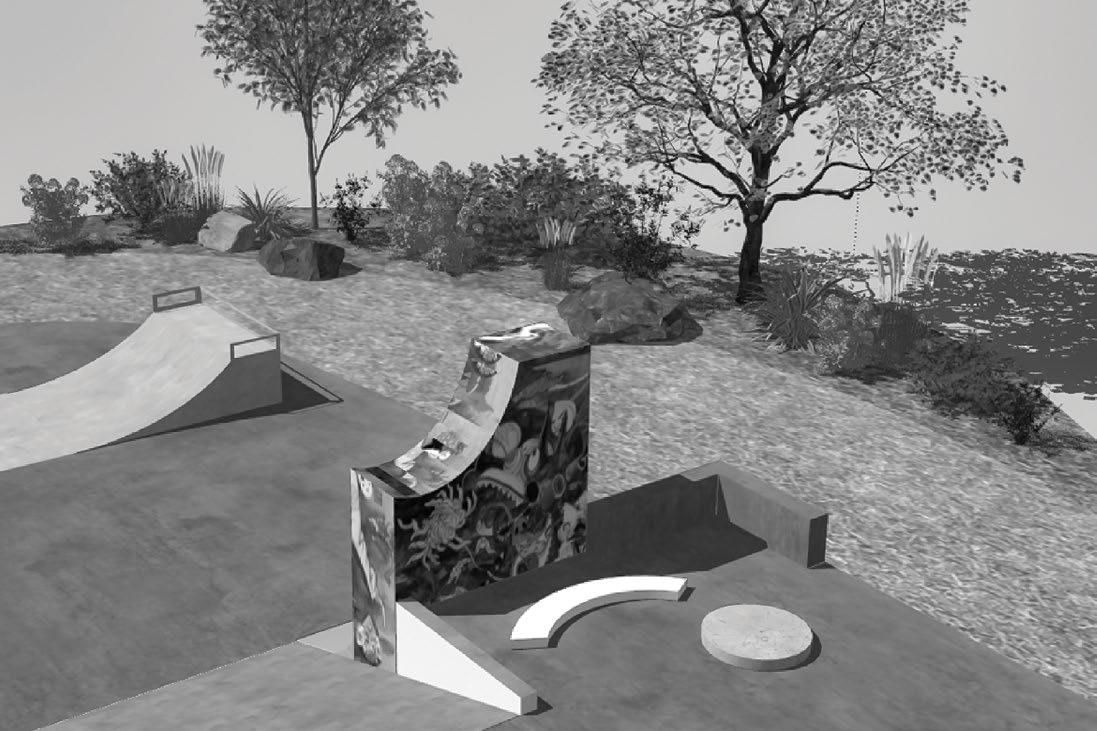

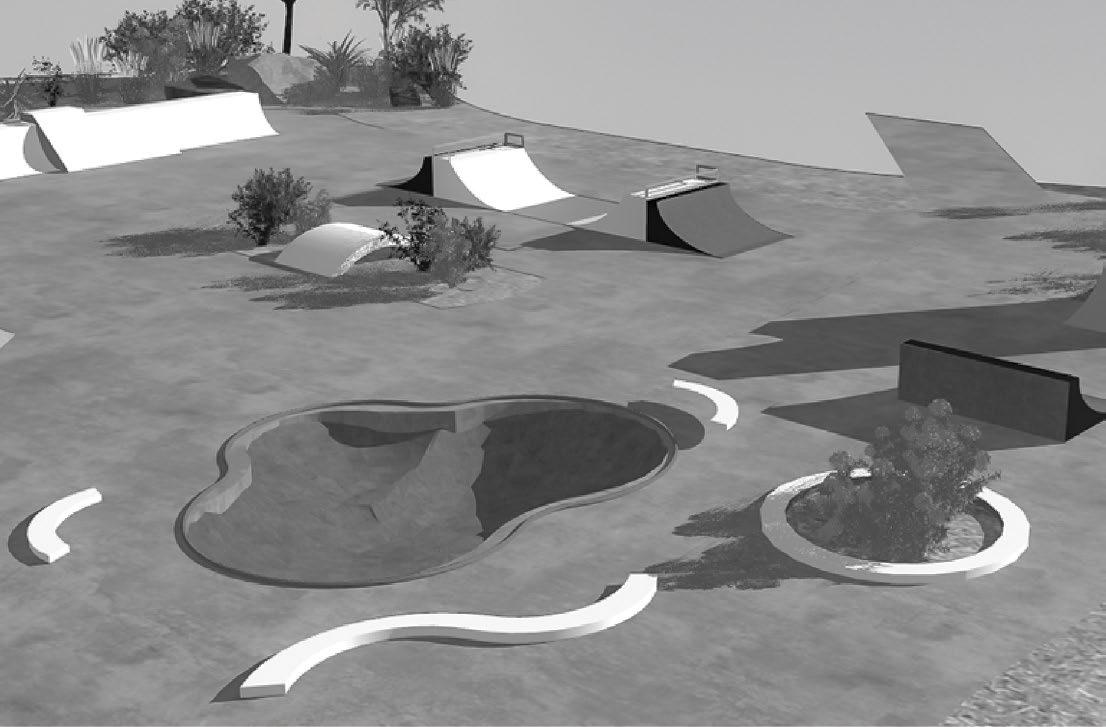

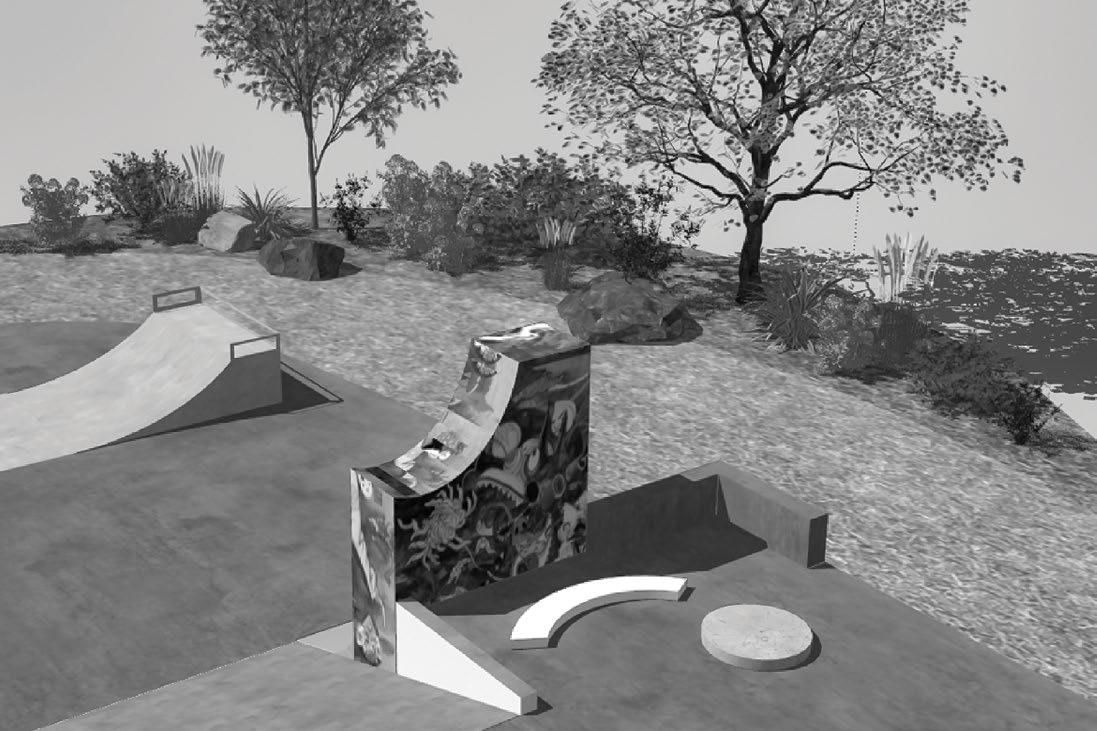

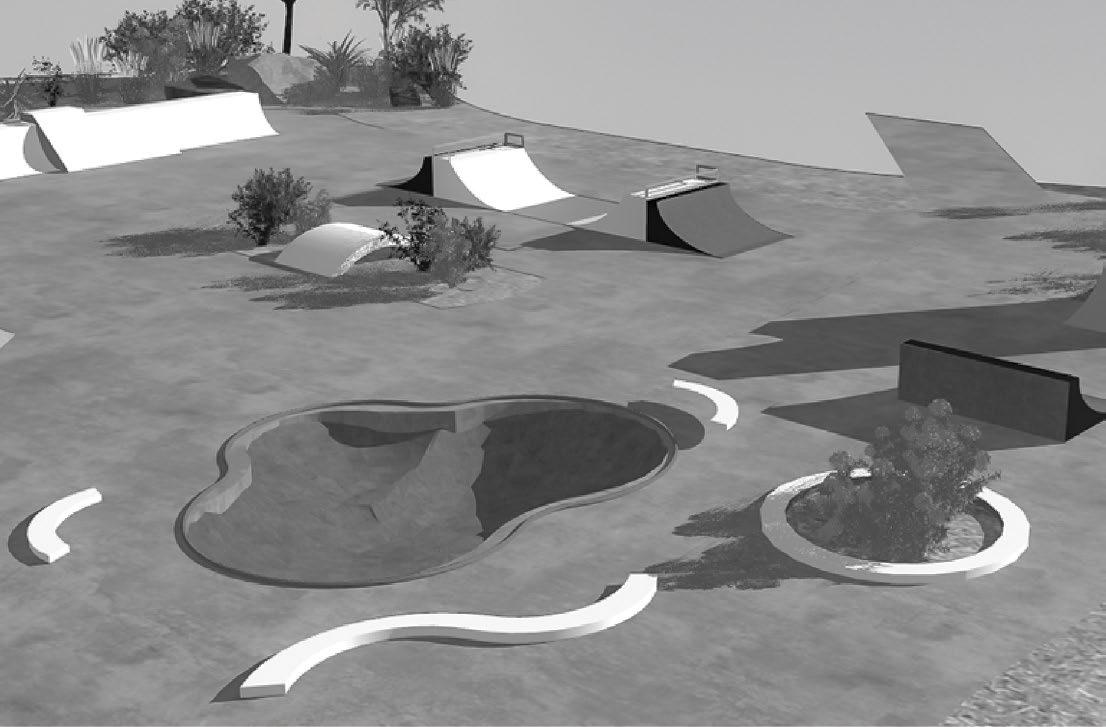

Cities offer playgrounds for children and parks for adults; yet rarely do they feature spaces designed specifically for teenagers and their physical activities. This Environmental Design studio asks, “why?,” tackling “designing for teenagers” by activating once “dead” spaces in West Seneca, NY. By repurposing post-industrial spaces into skateparks, students examined how skatepark culture impacts urban populations. Working with professional planners and local stakeholders, students set their sights on bringing a new form of civic engagement to an underserved population in West Seneca.

Skateparks and skate culture have a long lineage in US history, often used as a way to blend art and culture with an industrial landscape. They can provide youth with safe spaces for exercise and places for building relationships with like-minded individuals.

In conjunction with their client, West Seneca Bikes, undergraduate

environmental design students gathered data and developed proposals to bring to the Town Board of West Seneca. Student work included fieldwork, social and racial studies, interviews, and more. In order to establish a wider following for their work, the class created a social media presence to further introduce skate culture to West Seneca.

“We asked the West Seneca residents what they wanted to see in the skate park and then picked out eight elements that we wanted to include."

- Irene Mallano

The final report includes original design renderings of potential skateparks. While skateparks are primarily seen as concrete-dominated areas, the students illustrated how they could offer valuable environmental considerations. Bowl and pool elements allow water or snow to exit and flow into the surrounding green scape. Other park features brought design elements

for local youth or artists to graffiti to highlight community art. The renderings were ultimately handed off to the West Seneca Town Board, who will decide whether or not to move forward with implementing a skatepark.

Writing grant proposals, surveying, and continuing to keep community members actively involved is a tall task for anyone. This studio got the project off the ground; however, a project of this magnitude takes a collective community effort in urban placemaking.

38

BAED RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

END450

39

Skatepark design proposal, Mallano

Half-pipes, vert ramps, pools, and more

Incorporating local art into the park

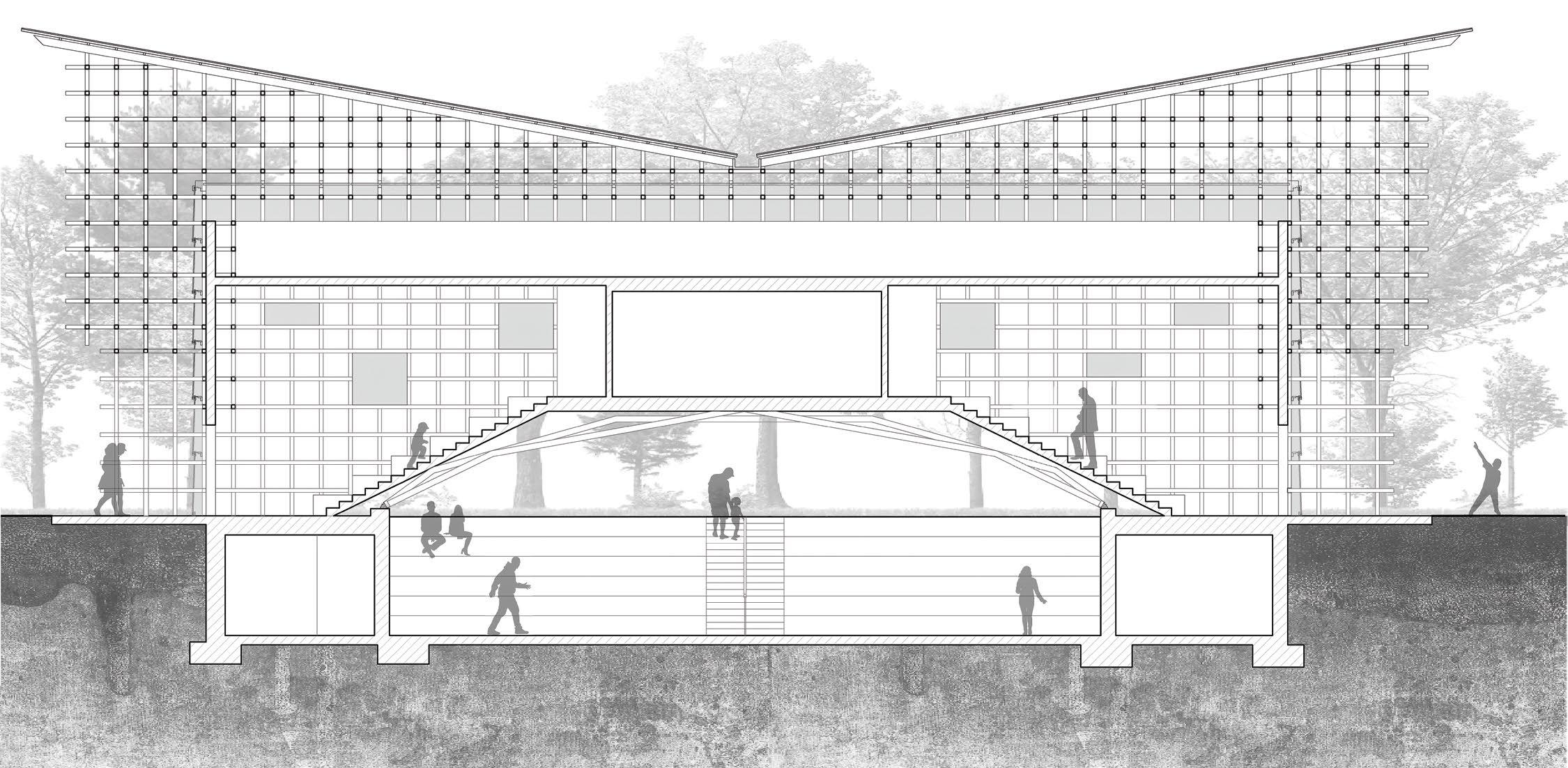

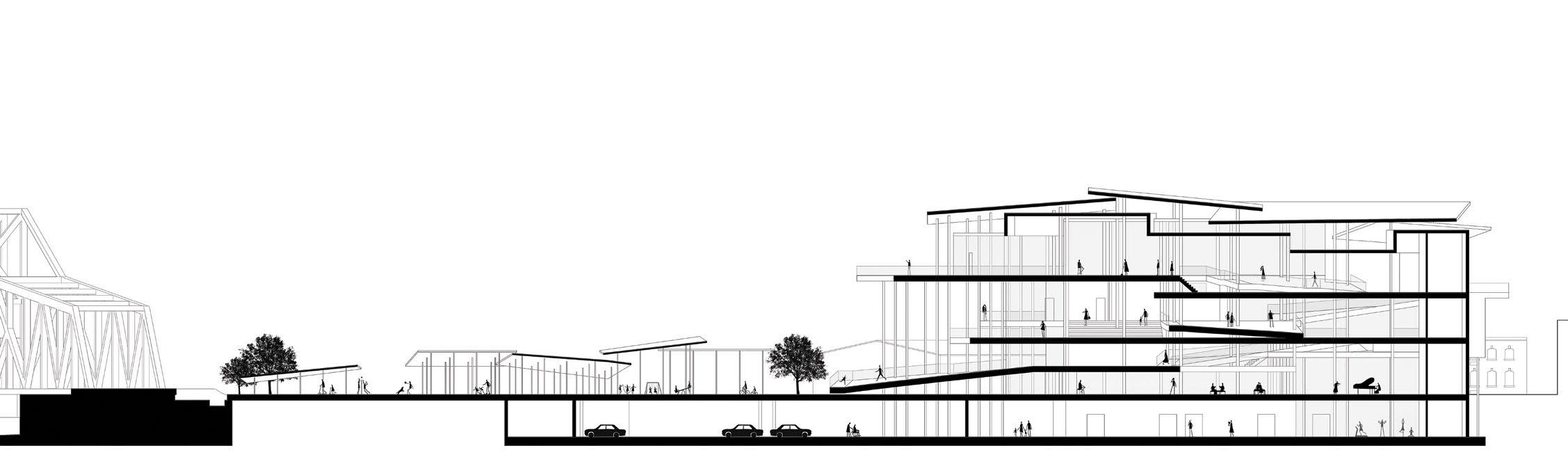

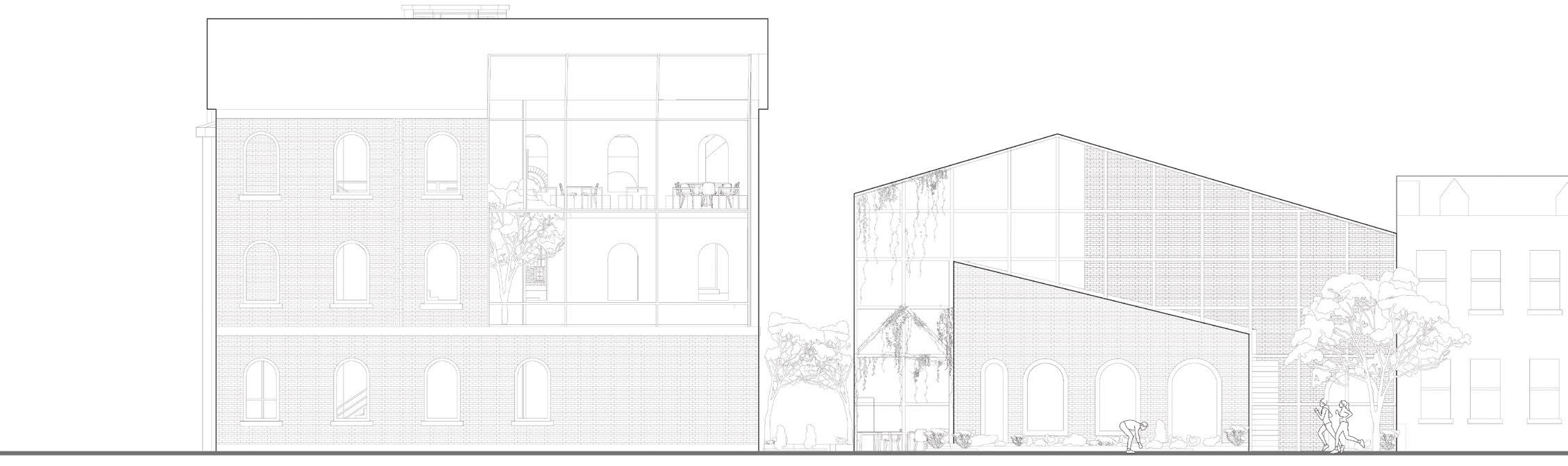

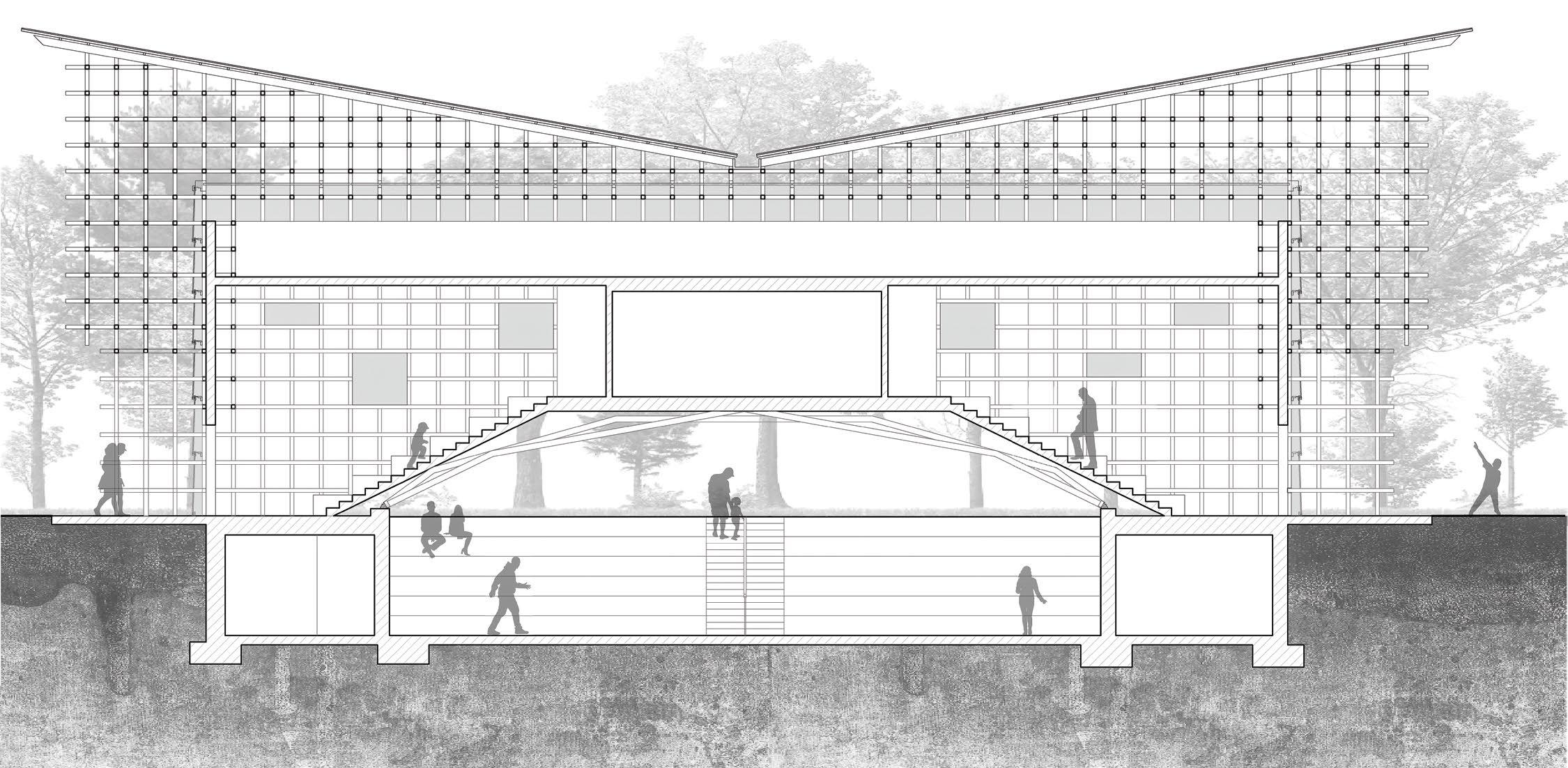

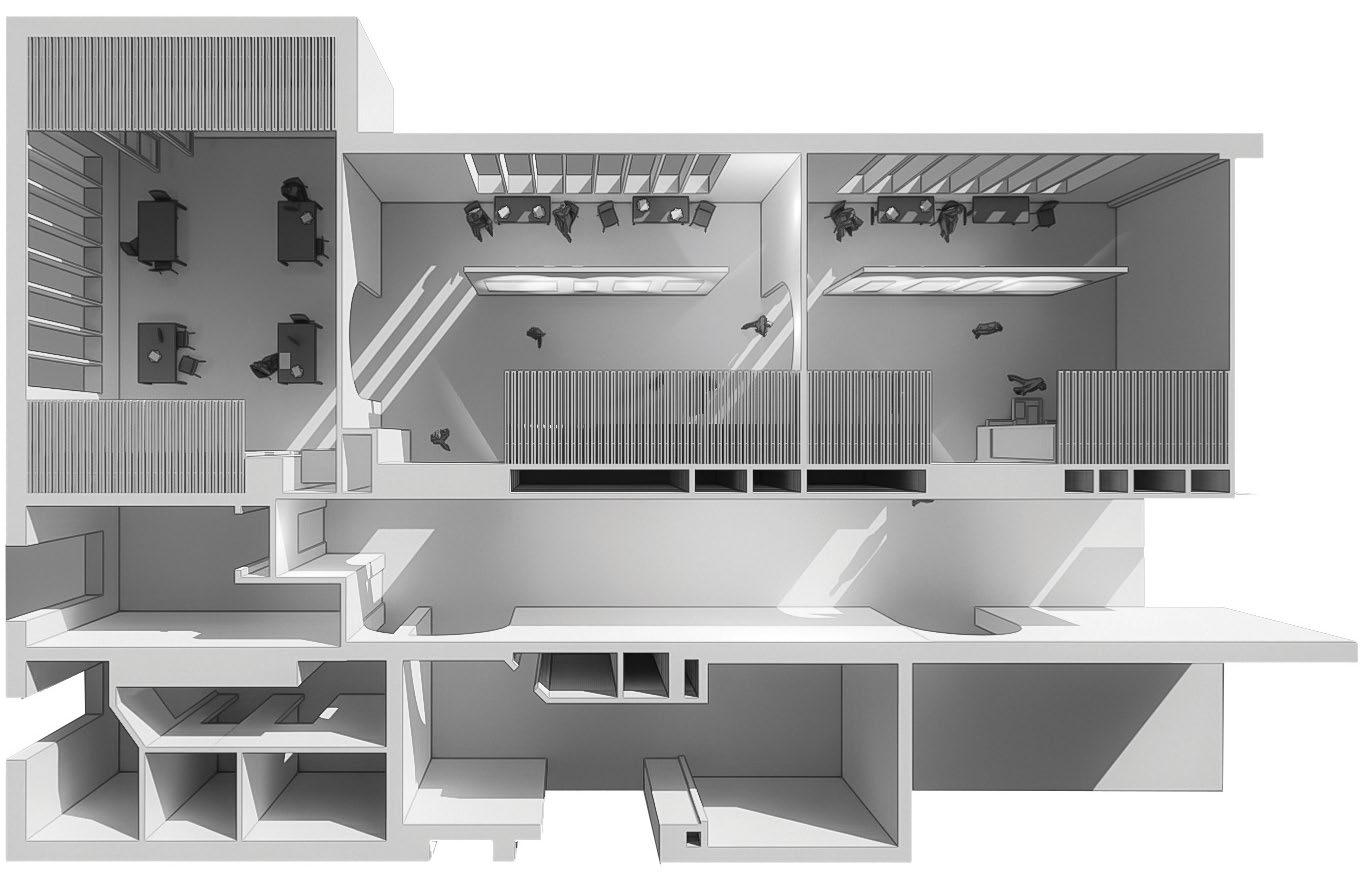

BUILDING SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Song Eun Han

Elaine Chow, Seth Amman, Brian Carter, Kenneth MacKay (coordinator), Jin Young Song, Bradley Wales Spring 2022

ARC302

BS Arch

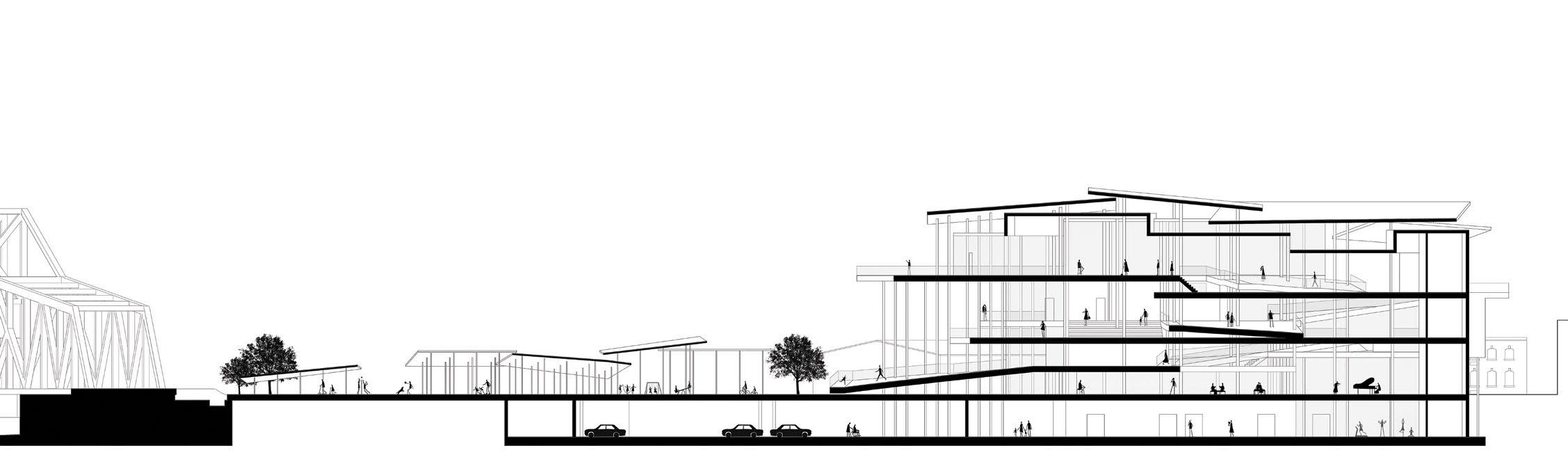

What is “social infrastructure?”

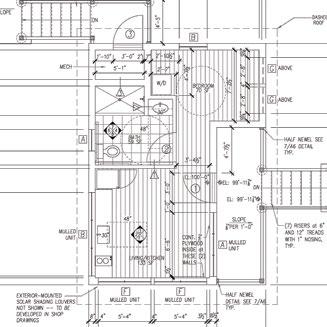

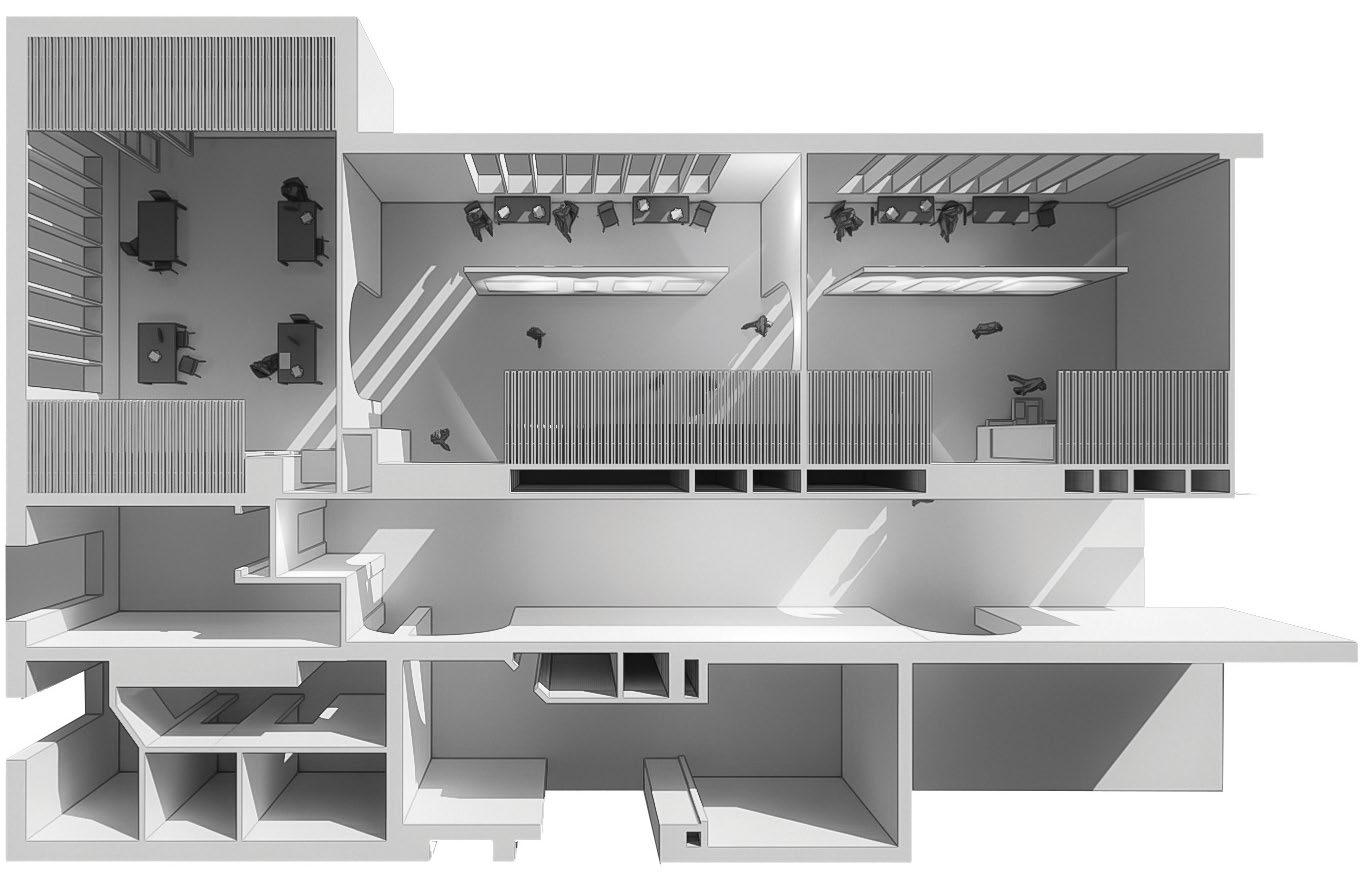

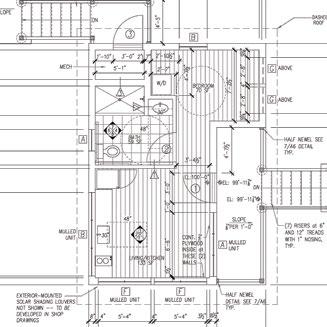

This third-year studio defines it as structures that house foundational services to support the quality of life of a nation, region, city, or neighborhood. Education, healthcare, public safety, and cultural aspects are some of the themes students tackled. Following the fall studio, where students designed a low-density, primarily single-story project, this project challenged students to grow their knowledge of structure and the integration of building systems through a multistory design project. As the “integrated” undergraduate studio, building systems such as structure, ventilation, and egress were primary objectives.

The site, Black Rock, NY, is a relatively isolated neighborhood and disconnected from the rest of the city. This forced students to think deeply about how to integrate forms of social infrastructure into their community center proposals, to increase social connectivity, community appeal, and civic participation.

Song Eun Han, whose scheme is featured here, built on themes of connectivity and designed her program to provide opportunities for Black Rock residents to engage in social activities. Her proposal included a library, classrooms, lecture halls, exhibition spaces, and more. The addition of a cafe promotes civic participation and serves as a source of economic growth for the neighborhood. It also provided a space where people are welcome to congregate and linger regardless of making a purchase.

The spatial needs of each program drove the form-making strategies for the project. Paper models and sketching were integral to the design process and final idea generation. Weaving programs together through a series of slanted, stacked planes integrated spatial functions with one another, furthering visitor socialization.

40

"Well-designed social infrastructure provides people opportunities to engage in society and build deeper relationships."

- Song Eun Han

Conceptual paper model integrating shifting planes

RELATIONS

RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

CULTURE EXPLORATION

41 Exterior render

Building section

Experimental form-finding through plan and section

BUILDING BOATS/ BOAT BUILDINGS

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Students of ARC302

Kenneth MacKay (coordinator), Elaine Chow, Randy Fernando, Anahita Khodadadi, Gregory Serweta

Fall 2022

ARC301

BS Arch

How can architects translate hands-on knowledge of building tectonic objects into the design of complex structures? The regatta—an annual tradition— serves as a milestone event for the junior studio that seeks to address this question. Racing hand-crafted vessels along Buffalo’s Gallagher Beach is a core memory for many students. The fast-paced construction process takes place over the first month of the studio and involves translating digital geometries into a full-scale construction project. The relationship between a structural frame and a watertight envelope is used as an analogy and reference for the design of building projects later in the semester.

Each year the fall studio takes a slightly different tackle than years prior. This semester focused on the use of wood as the primary building material with a focus on sustainability. Students began their research individually, analyzing particular geometries utilizing either linear pieces of wood or sheets of plywood wrapped around structural frames. Using this work as a

foundation, students combined into teams of six to build two boats per studio, each accommodating two skippers. Teams worked together on regatta day to compete against the other studios in hopes of capturing the Keelson Award, a trophy passed down year after year, with the winning boat’s name engraved into the side of the acrylic block.

The vessels built by students all followed the same set of guidelines; to accommodate two students at a time, each boat followed maximum dimensions of 12’-0” long x 3’-6” wide x 2’-6” deep. Powered by paddles, the seaworthiness of each vessel was judged on its ability to displace the weight of the skippers and how well they were able to maneuver it through the water as well as their innovation, craft, and elegance.

These lightweight buoyant objects with complex spatial geometry built at full scale tested students’ ability to combat water density, gravity, and wind. Structure and skin, which in the

boat project work in harmony to keep water out, have a direct relationship to the needs of a building. Following the boat building process, students spent the remaining portion of the semester designing a boathouse and exhibition space. These proposals provided direct access to the Erie Canal and prioritized the land and water threshold. Translating the experimental boats to buildings is central to this integrated studio’s themes of structure and enclosure.

"As a team, we opted to move away from the traditional methods of boat construction, but rather used entirely CNC-cut pieces that would fit together through a complex system of joinery."

- Ian Simmons, The Vulture

42

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

43

Annual Regatta at Gallagher Beach

Capturing every moment

The Vulture, mid-race

THE VULTURE

Focused primarily on modularity and interlocking mechanisms, The Vulture team designed a prefabricated canoe focused on joinery. With tailor-made joints, the team avoided using screws, nails, or other standard fasteners. Its dacron skin worked alongside the joinery to hold everything in place through a stretched inward force. The thin, watertight material highlighted the frame to create a drum-like effect.

44

Exploded axonometric, The Vulture

EXPLODED AXONOMETRIC 1 2 3 4

Skin to frame construction, The Vulture

THE CURLY BRACKET

The Curly Bracket comes from studying traditional canoe and kayak forms and focusing on sustainable design. This team chose to use natural materials even if the resultant processes were more difficult or time consuming.

Material sourcing became a driver for this group, using White Ash trees for the boat’s structural members. Many of the ash trees in Buffalo are dying due to beetles feeding on the wood, cutting off all nutrient transport and killing

the tree. Before the trees became unusable, the team repurposed the wood for their boat, producing wood chips with any extra material. Cutting logs into slabs, the waterjet cut out the slightly “V” shaped ribs to cut and displace water in a way that reduces drag.

45

Frame and rope construction, The Curly Bracket

Laying out ribs to be milled with the waterjet

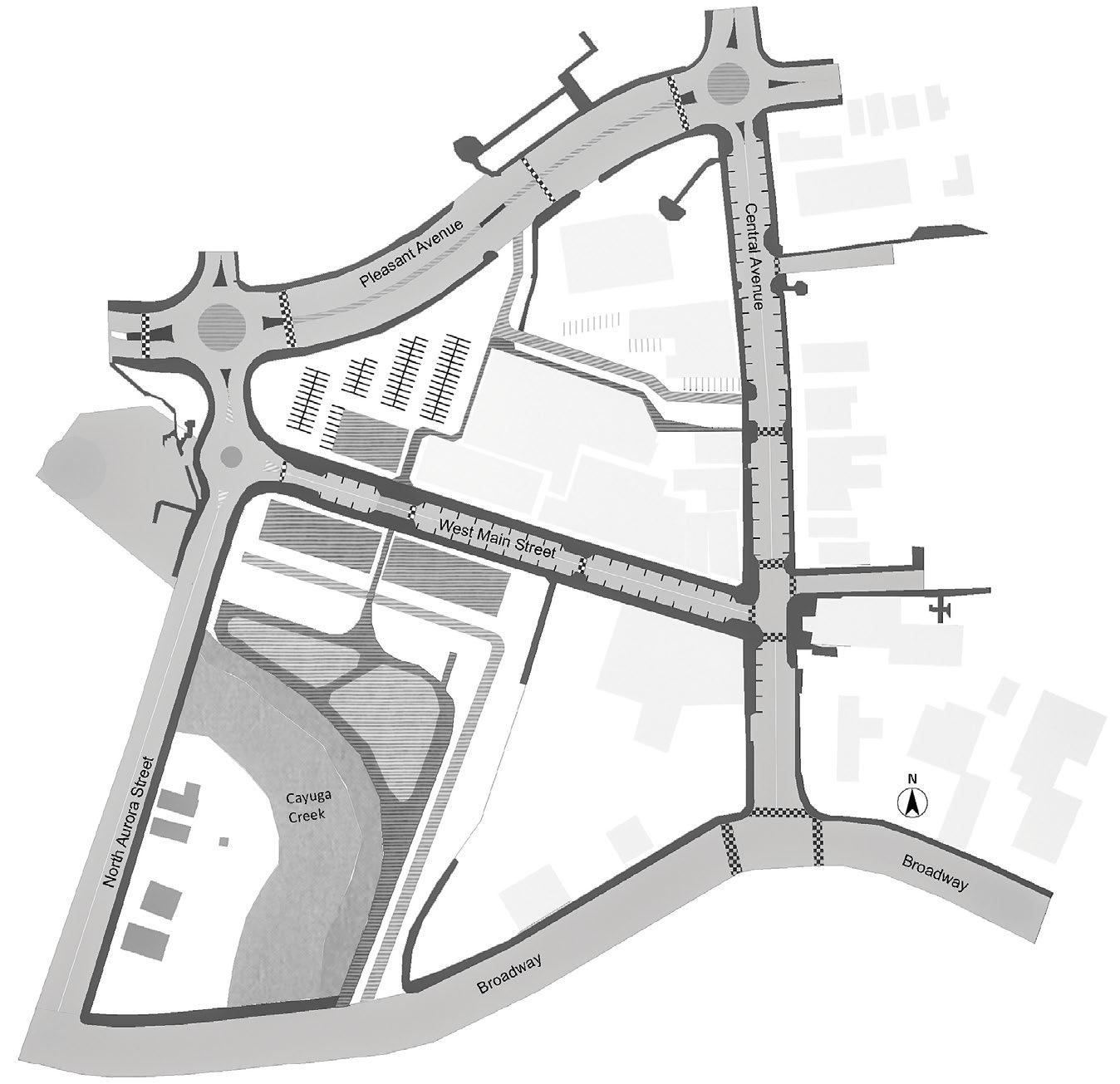

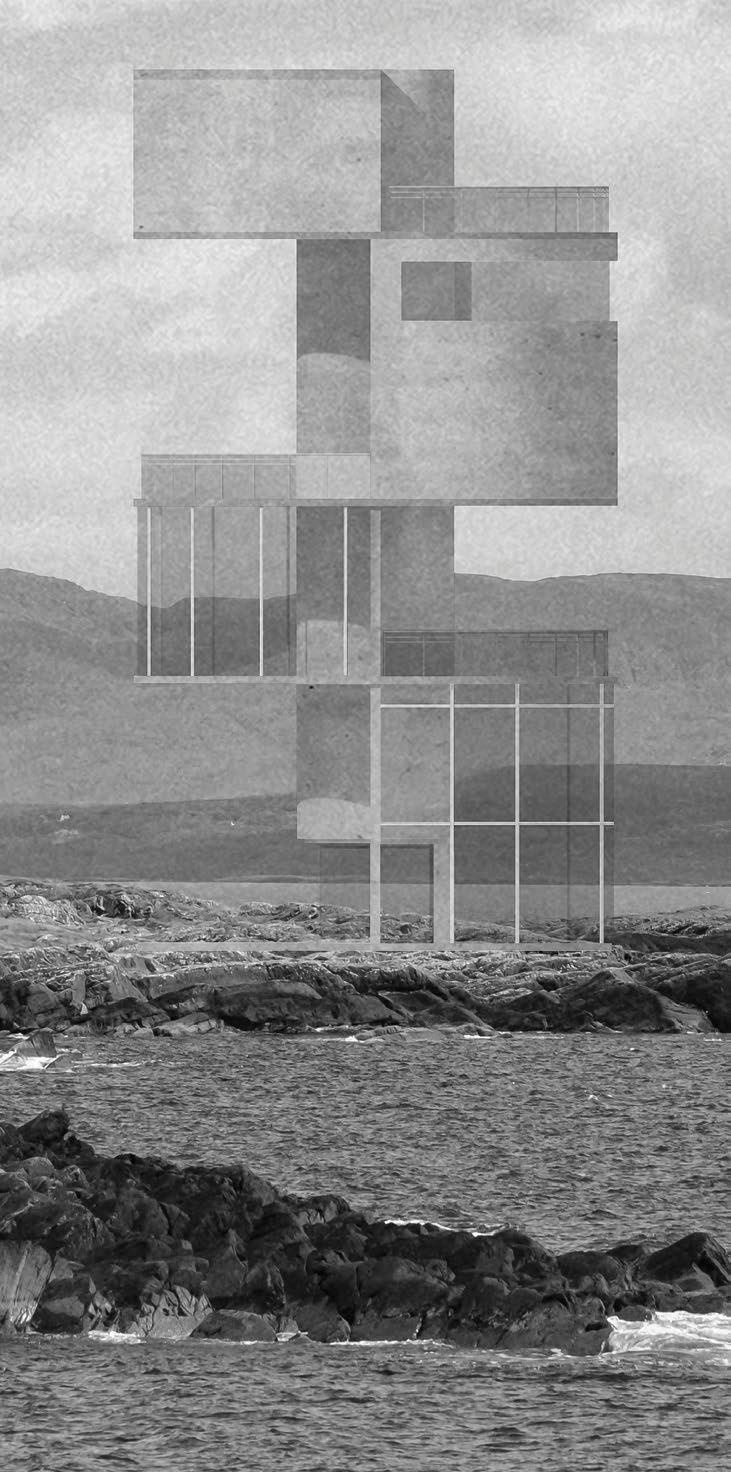

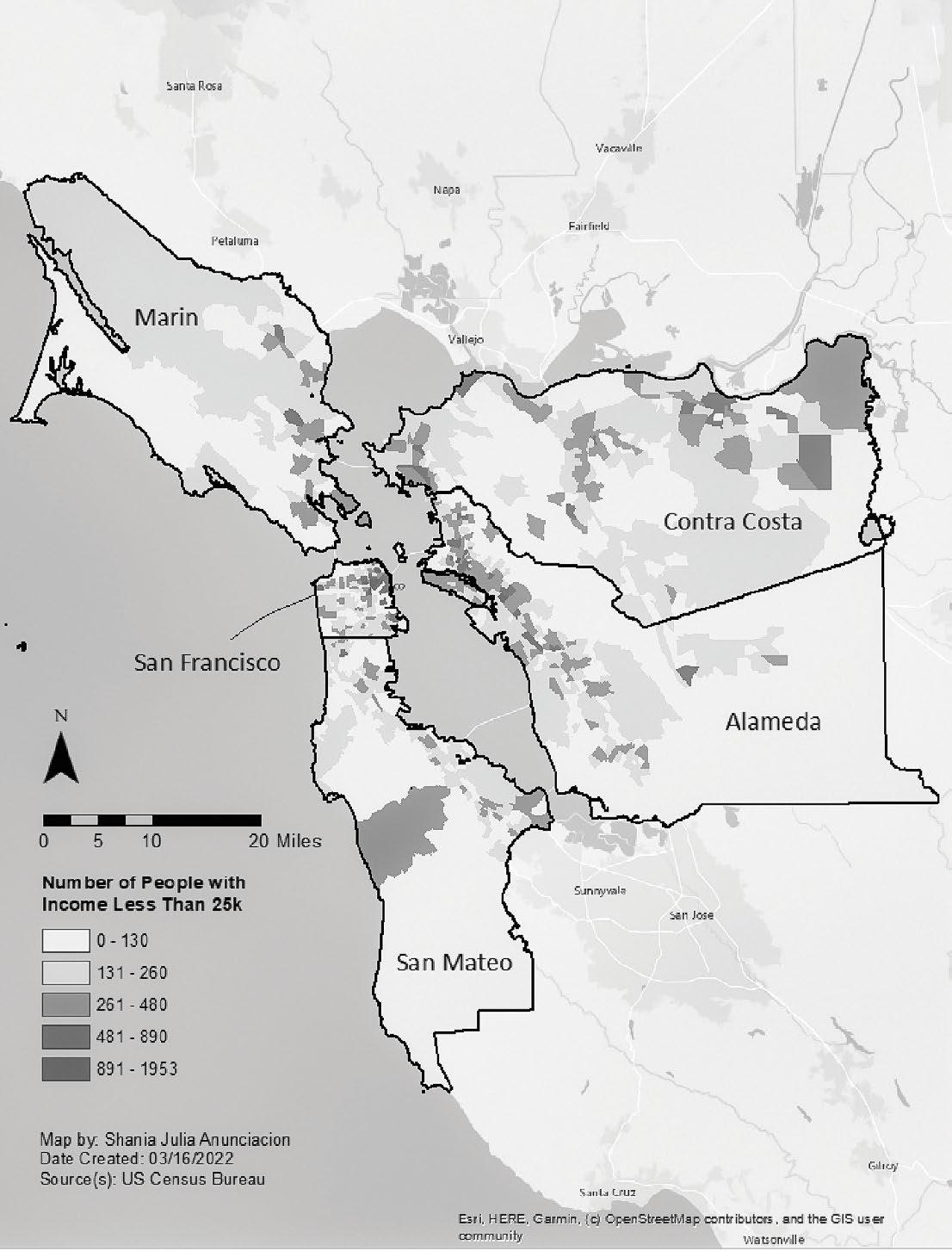

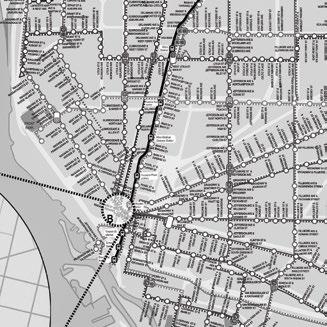

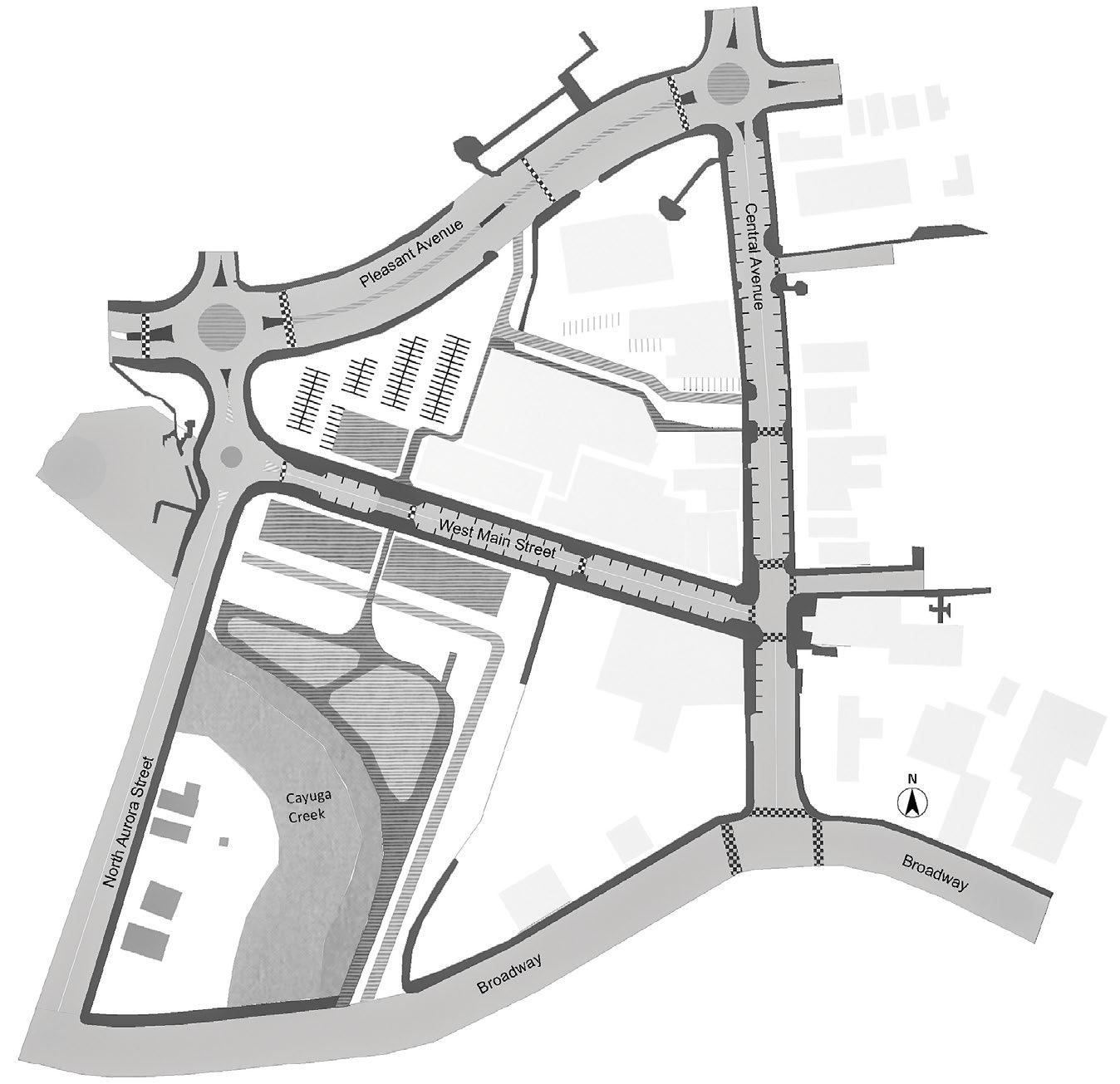

PLANNING INITIATIVES FOR LANCASTER

Students:

Christina Brooks, Jack Draksic, Dalton Fries, Bethany Greenaway, Andrea Harder, Nathaniel Miller, Tyson Morton, Deeksha Nagaraj, Annapurna Nayak, Silvi Patel, Michael Pesarchick, Cristian Toellner, Kyli Tripoli, Devyn Walker, Parker Webb

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Ernest Sternberg

Spring 2022

URP582

Can a coordinated plan for housing, greenways, and downtown vitality help restore once lively town centers? Students from this urban and regional planning studio worked in close collaboration with city leaders in the Village of Lancaster to analyze and prioritize upcoming community initiatives. A list of researched projects included affordable housing, intensification of the downtown district, bike and greenway connections, food access, accessibility routes, and real estate development opportunities on village-owned properties.

“This studio was kind of like the intersection of students’ passion and care and bureaucratic policies… It was a real life experience”

- Bethany Greenaway

Students began their research by looking into the demographics of Lancaster, a population that has seen a slow decline since 1980. Despite this, the village remains a small suburban municipality with close-knit

relationships. Compared to adjacent municipalities, the larger town of Lancaster boasts a median household income of just over $70,000, higher than the village center of Lancaster, Depew, and Erie County.

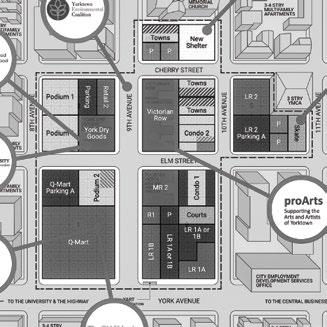

Students justified the need for change using the data and information gathered from past Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) reports. They recommended expanding the DRI boundary, which included seven additional sites around the village, all with opportunities for redevelopment. Repurposing these parking lots, existing buildings, and waterfront properties into affordable housing sectors or grocery stores help align with stakeholders’ visions for village expansion.

Pedestrian-friendly circulation, public green space, and bike/trail connectivity are a few examples of how students sought to develop underutilized land. Students also identified the need for infill housing, following the principle

of “gentle density.” This principle prioritizes duplexes and courtyardstyle apartments over large housing projects or single-family homes. New development often comes at the cost of new circulation patterns; therefore, it was imperative to know how changes to existing conditions would impact multi-modal forms of access.

All of the recommended initiatives are efforts to help the Village of Lancaster solve current challenges by leveraging its current assets. Working directly with city officials allowed students to present comprehensive arguments on potential strategies for implementation.

46

MUP

RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION

47 Large apartment housing

properties

homes

Mixed-used

Single-family

6 Person 7 Person or More

Mapping the public realm of Downtown Lancaster 2019 2010

Data charting size of household within the Village of Lancaster, source: American Community Survey (ACS) Household Size 5 Person 4 Person 3 Person 2 Person 1 Person 0 500 1,000 Number of Households 1,500 2,000

Source: American Community Survery (ACS) years 2010 and 2019

IRELAND AS IMAGE

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Mariella Hirschoff, Naiara Mares, Bianca Wilson

Kenneth MacKay

Summer 2022

Study Abroad, Ireland

BS Arch, MArch

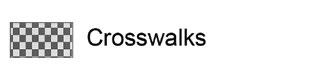

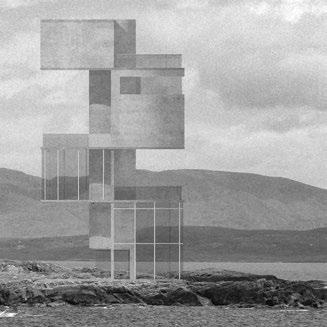

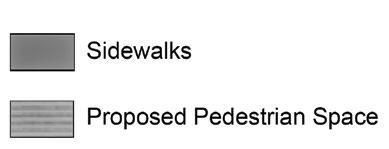

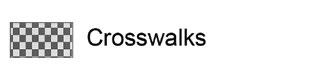

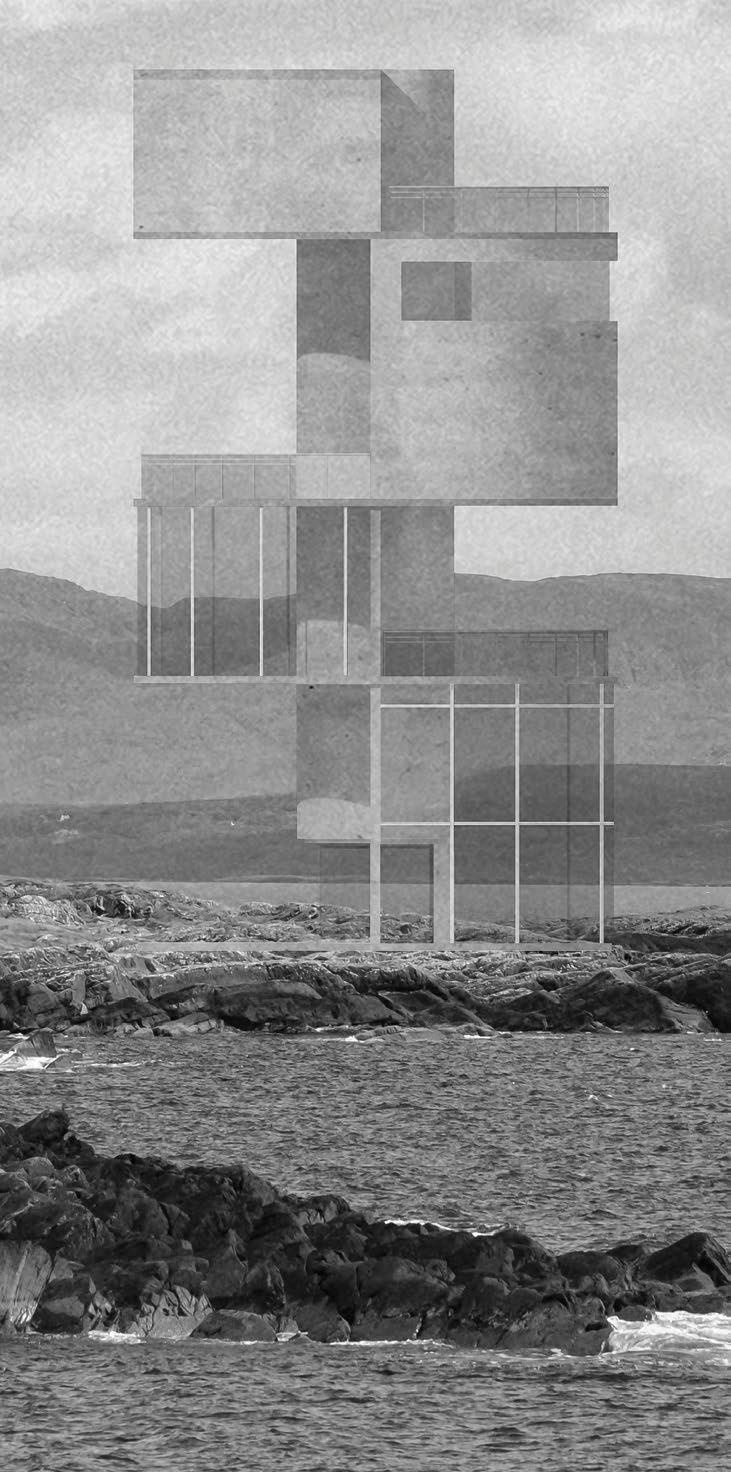

How can we translate visual observations into tangible representations of our experiences? The Ireland Study Abroad program invited students to reflect on how Ireland is perceived as both landscape and urban form. Each day students explored rolling landscapes, seaside towns, and bustling cities daily. They observed the lighting conditions, urban forms, and landscape environments unique to each context. Through the design studio and parallel seminars, students cataloged their observations through carefully composed photographs, fast and loose sketches, and digital and analog collages.

DIGITAL COLLAGES

The students worked on design proposals for a series of three small art galleries. These galleries would be a new location to house the Book of Kells, a preserved illuminated manuscript and an essential piece of Irish history. The program brief required students to design according to a four-square grid; a space for viewing the manuscript, a library space, living

48

Digital collage, Hirschoff

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

quarters, and a space for viewing the surrounding landscape. An emphasis was placed on developing a hierarchy of public and private spaces and designing a space that could adhere to the strict lighting conditions required for viewing an ancient manuscript. Students used photographs from various day trips as their selected site locations for the manuscript galleries. The site photographs formed the base for the digital collages, where students “placed” their gallery proposals into the landscapes.

“Collaging is a collaborative way to capture personalities, diversities, and complexities among the design process. It is also a means of accepting and celebrating mistakes.”

- Bianca Wilson

PHYSICAL COLLAGES

Students collected postcards to study the spatial relationships seen in the built environments of both Ireland and Scotland. Students collected the

postcards from various shops, galleries, and museums they visited to use in their physical collages. This assignment aimed to generate new architectural spaces and landscapes from the familiar and cliche postcards that were widely available. Analog collages also allowed students to remove themselves from the digital realm and bond with each other over daily trips to craft stores.

49

Digital collage, Hirschoff

Physical collage, Mares

Physical collage, Wilson

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Sean Brunstein, Allison Gomez, Kaleeka Mittal, Mayank Sharma, Lindsey Bruso Brian Carter, Adam Thibodeaux, Justina Zifchock

Fall 2022

ARC503/603

3.5-YR MArch

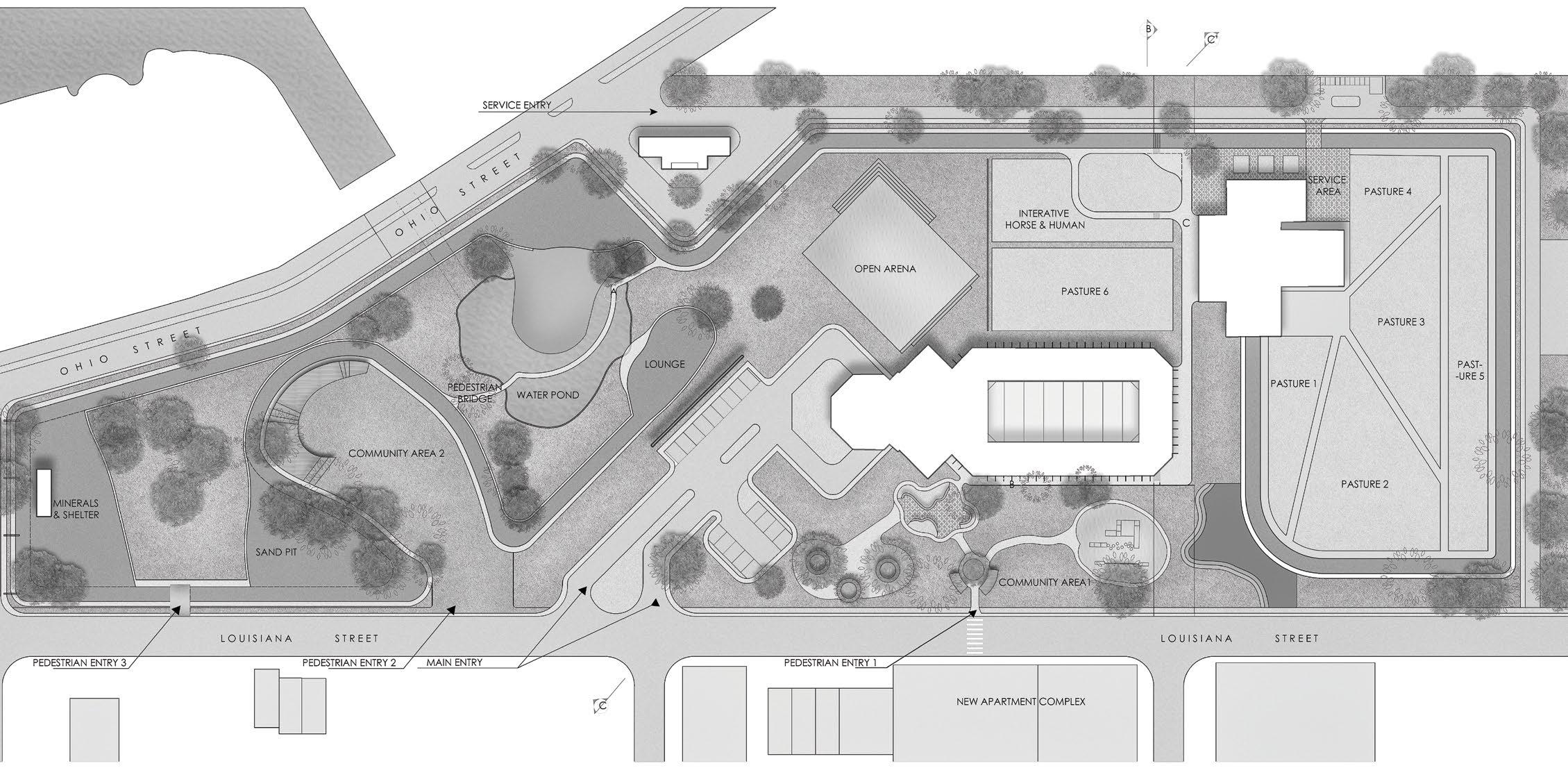

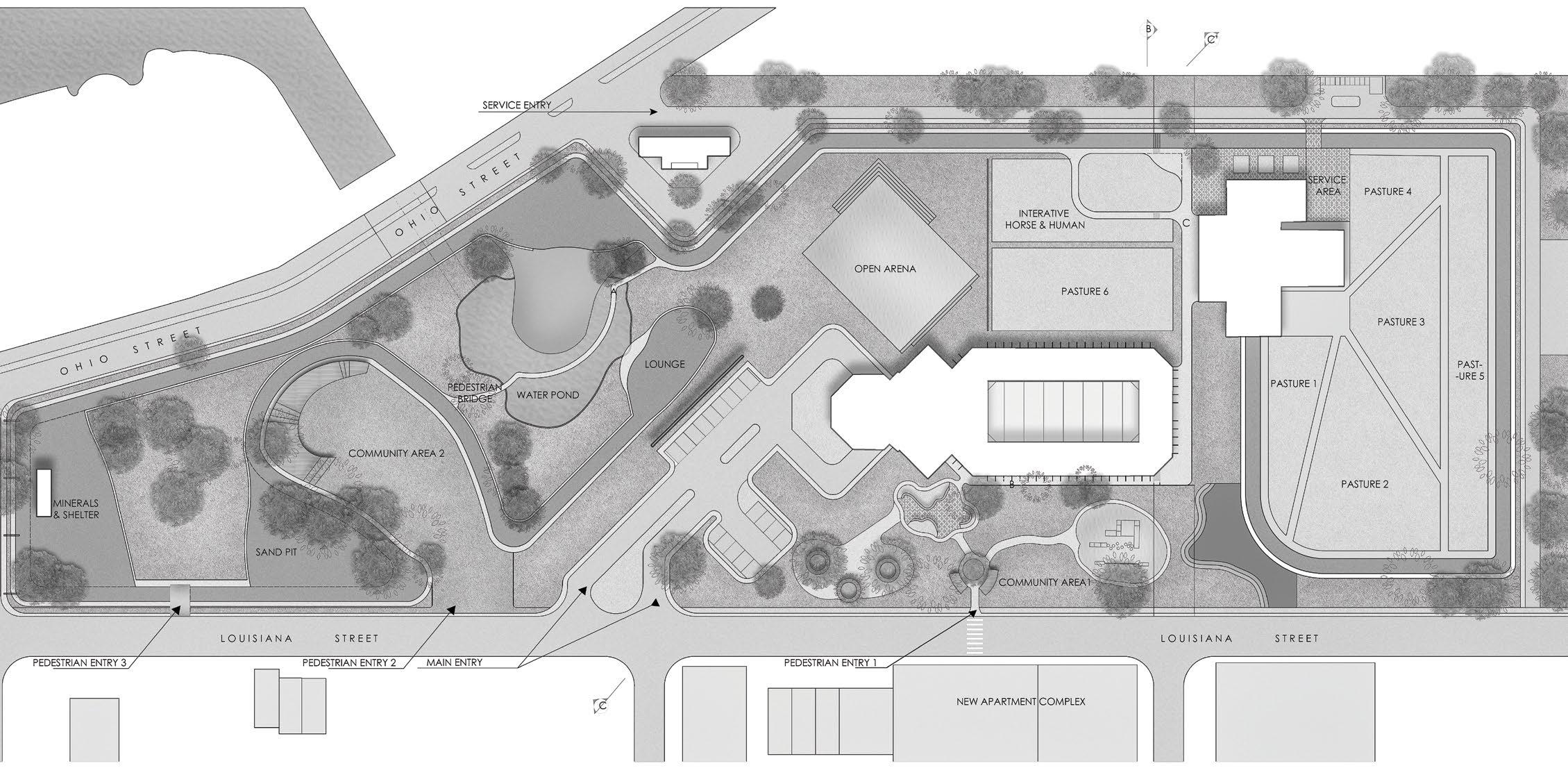

How could we alter our design process to imagine spaces that promote the wellbeing of nonhuman species? The second studio in the 3.5-year master program, addressed this question through the design of a riding school in Buffalo. Horse riding in many cultures has a direct link to human settlement, agriculture, conquest, and settlement. The therapeutic benefits of horse care and riding are well documented and continue to attract the research interests of many different professions.

To introduce students to this rich territory of investigation, they were first asked to make full-size models and drawings of horses to develop a better sense of their bodies. They also conducted site visits to several barns in the area to learn about the challenges of caring for horses and the spaces they require.

These trips to Gasport, NY, and the Buffalo Riding Center gave students an understanding of the potential effects riding centers have on communities: physical activity and increased mental

health. The studio also consulted with local landscape architects and structural engineers, enabling students to network with industry professionals and develop their designs throughout the semester.

Drawing a life-size horse positioned students to fully understand the scale and stature of whom they were designing for. Next, they split into teams to create three physical models of a horse using any materials they could find. The collection of drawings

and models served as inspiration for the students to carry forward.

The project site was Father Conway Park, within Buffalo’s First Ward, home to several existing revitalization efforts. Sandwiched between a residential neighborhood and popular restaurants, the park acts as a threshold to the Buffalo River and Outer Harbor beyond.

50

HORSE

Students working amidst horses.

OUR WORK OUR WORLD

Photo: Meredith Forrest Kulwicki

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR

51

Group model made from cardboard and yarn. Photo: Meredith Forrest Kulwicki

Site visit to the Buffalo Riding Center

Full-scale horse drawings adorn the studio walls.

52

Exterior perspective, Brunstein

Interior riding hall, Gomez

Interior riding hall, Sharma

Horse barn, Bruso

“We always have this horse in the studio alongside us, and can develop our designs with horses in mind... A constant reminder of who we are designing for.”

- Sean Brunstein

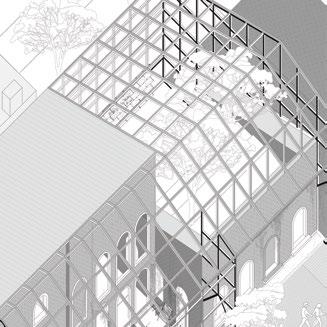

Positioning horses as primary clients, the studio investigated the formal and conceptual potentials of building materials and construction systems that could support the needs of humans and horses. For MArch student Allison Gomez, the indoor riding hall was the heart of her scheme; a 220’ by 100’ open structure with moment framing, bracing, and clerestory windows. Stables lined the southern end while the northern end transitioned directly into the outdoor riding space. She also integrated an interactive and

cooperative gallery on the site to add to the required programs.

Her vision was to create a place where Buffalo residents could visit and take ownership of the exhibition space based on their needs and wants. Proposed seven feet beneath ground level, with a series of carefully laid out exterior spaces leading to it, this gallery spans the length of the indoor riding hall. Within the gallery is a café, lounge, and art exhibition space. Careful circulation design allows horses to be brought in and interact with artists.

The landscaping, designed to complement adjacent streets, leads the users, both horse and human alike, to the gallery and the riding hall. Sinking the outdoor riding area

allows space for spectators above the action with seating elements designed to encourage social interaction.

Keeping the comfort and privacy of the horses in mind as they designed, students learned how horses, just like humans, are each unique in their own way. Each student proposal created new and interactive experiences not typically seen in an urban environment. Riding centers like those proposed by these students give people (and horses) of all ages a chance to build skills, confidence, and improve physical and mental health in metropolitan areas. This is yet another example of how our design thinking can demonstrate care for others, this time across species.

53 Site plan, Mittal

3.5YR & INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS A CONVERSATION

Students: Moderator: Lindsey Bruso, Ehler Htoo, Behnoush Nikparvar, Mayank Sharma

Madeleine Sophie Sutton

ADJUSTING TO NEW ENVIRONMENTS

Diverse backgrounds in planning, environmental design, liberal arts, social sciences, mathematics, history, and even music collide in this program to form a group of students with no architectural background. Some are familiar with the City of Buffalo and UB through previous degrees. This cohort of students takes a sequence of four studios, from ARC501 (Good Neighbors) to integrated design studio ARC504 (City Arts). After this sequence, students enroll in the Graduate Research Groups, or option studios, or decide to go into the thesis track.

Design studios provide a platform to develop an open dialogue between professors and students. Responses from the students illustrate how they adjust to life in Buffalo, while discovering new design ambitions in architecture school. Care is important in the context of this program, particularly as students transition from other degrees, cities, and cultures, and adapt to Buffalo and UB.

LEARNING FROM EACH OTHER

Madeleine Sophie Sutton: Care seems particularly important in the MArch program. Where have you seen themes of care progress during your time at UB?

Lindsey Bruso: The professors really care about the projects we’re given and are enthusiastic about them, which makes students care more and become excited to work on them.

Mayank Sharma: When we are working on a project, they make sure that we do think of inclusivity and equity. We care about the people living near our site and the context.

Ehler Htoo: This semester, when reading through one of my course syllabi, I noticed the professor stated she has a lot of respect for others who have to care for other people. Throughout the semester, the professor consistently accommodated those ideas. In studio this semester, the professors stated from the beginning that they don’t condone all-nighters,

and insisted that we not implement that into our life. They reminded us to eat, exercise, and stay healthy.

MSS: The schoolwork we do here is really rigorous, particularly in studio. It comes down to that relationship between the students and their own studio environments, but also to the communication with the professor.

"Working with other people gives you a different set of views and values you would not normally have. It brings people's ideas together and allows me to open up my mind more."

- Lindsey Bruso

LB: I don’t feel that the stigma of the studio is competitive between students. I don’t feel that with anyone. I see everyone willing to help each other.

Behnoush Nikparvar: At first, it was very helpful to work in groups because I didn’t know anyone or anything about studio work at UB. Teamwork has

54

"Through this question and answer process with peers, it can generate your design process."

- Ehler Htoo

helped me get to know people and get support from them. The professors are very kind; the problem I have is with English. Working with the International professors has been very helpful to ease me into everything.

MSS: Given the range of previous university experience that many of the 3.5-year and international students have, how has the transition been into the UB community?

MS: Coming from India, the biggest culture shock was not American culture, as we are quite exposed to it from movies and TV, but actually how teaching takes place. In India, criticisms are much more pronounced when you present your work or discuss something. Coming to the United States, I had to get used to the teachers being very gentle with me, even when they’re pointing out something negative.

MSS: In a studio setting, we tend to form tight-knit relationships. Can you recall any moments where these bonds have influenced your creative process?

EH: Being comfortable with everyone in the studio is specifically important. Sometimes you have a question and you may feel afraid or nervous to ask it. When you form these relationships first, you can ask questions without thinking about it. This peer question-and-answer dynamic can help to generate your design process.

55

Students work on their accordion-like horse

MS: When you have an idea in architecture, you become possessive over it. Whether someone gives you a positive or negative opinion on it, that doesn’t matter. That comment helps you chisel away at that idea. It’s important to discuss ideas and show work to each other because it helps you get out of your comfort zone and open up your mind. An incremental flow of opinions coming from all around the studio is really important along the way.

BN: The process is so fast; it can cause some imitation seeing others’ work. Our studio last semester was divided into three sections separate from the others. Being part of the conversation between students and professors from other sections in the studio was most valuable.

LB: I think the connections even go past school work and architecture. I’m from Buffalo, so I get a lot of questions about Buffalo. The other day, Mayank asked me where a good place to get

sushi was. It is simple things like these that push the relationships we’ve formed even further.

56

"All the different building types and outdoor spaces have to interact with one another. Students design sitespecific buildings and landscapes that also improve the neighborhood and environment.”

- Justina Zifchock, Professor

57

3.5-year MArch fashion show, "Archi-Texture"

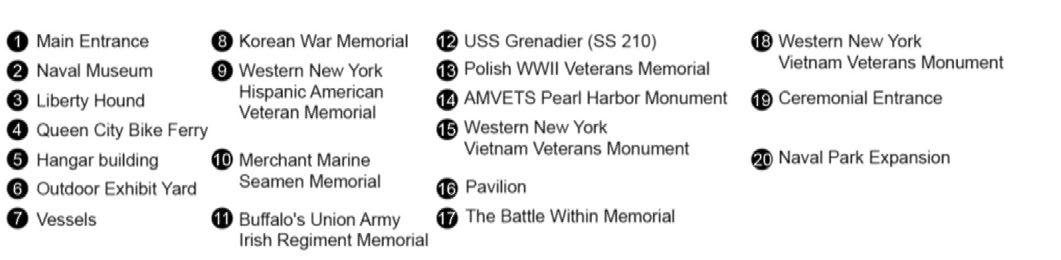

BUFFALO & ERIE COUNTY NAVAL & MILITARY PARK

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Jennifer Baldwin, Allison Carroll, Jacob Madia, Annupura Nayak, Michael Pesarchick, Aaron Vivian, Yan Zhang

Kerry Traynor

Fall 2022

END593/581, URP581/582 MUP, MSRED

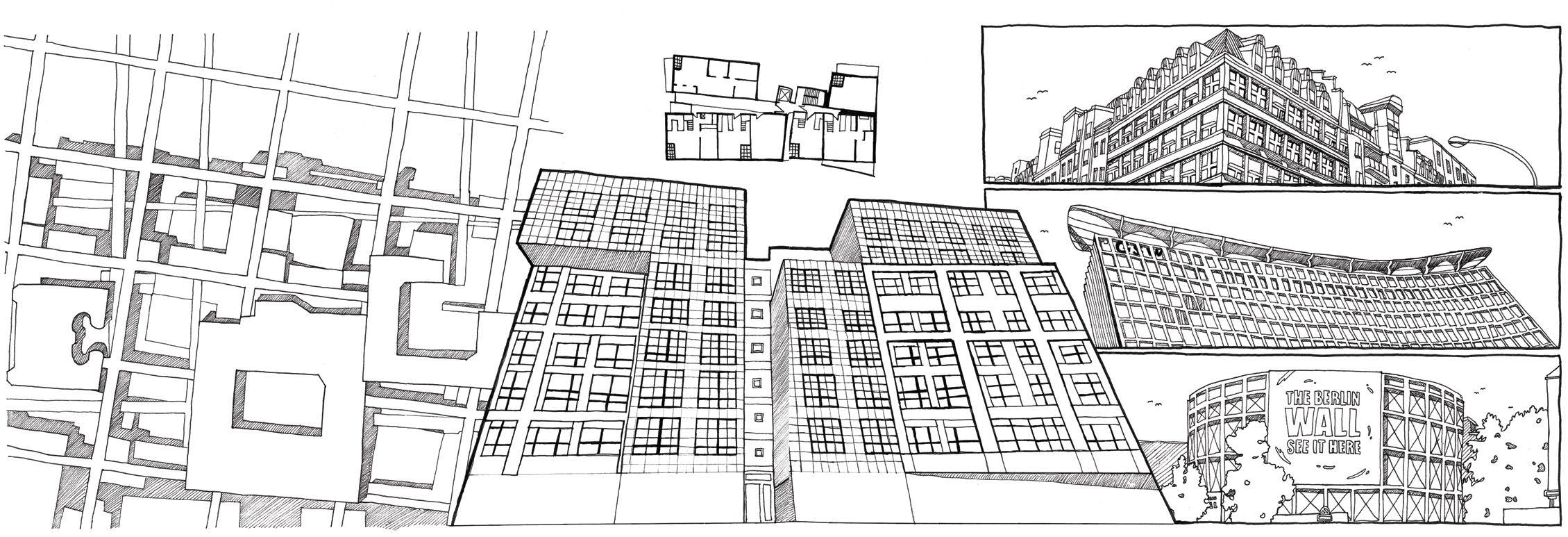

Can historic naval artifacts support waterfront revitalization and future development? The Buffalo and Erie County Naval and Military Park sits at the heart of Buffalo’s waterfront district, targeted for successive revitalization efforts. Graduate students in planning sought to produce a master plan of the park, reimagining it as a premier national and international inland Naval and Military Park.

Currently, three former US Navy ships are docked along the shoreline, the USS Little Rock, Croaker, and The Sullivans. While the ships have no immediate connection to Buffalo, they have become a familiar local attraction with untapped potential.

The capstone studio began by analyzing previous master plans put forth to develop the harbor. Using these plans as a framework, students examined how incorporating existing siting and infrastructure can set the Naval Park on a financially-stable path.

Students in the fields of Historic Preservation, Urban Planning, and Real Estate Development took on this project as practitioners would in a professional setting. Simulating projects like this in an educational setting allows students to enter post-graduate careers with some experience working across disciplines. The challenge in a studio setting like this one was balance, as it required leveraging perspectives of financial feasibility, urban planning, and historic preservation while granting the needs of a client or park visitor in a real-world environment.

The studio’s final master plan lays out a series of strategies and actions through a phased roll-out. Together, the students concluded that one of the first obstacles to tackle is addressing any damage or repairs to the docked ships. Upgrading the materials and layout of the grounds was also a pressing issue in the hope of spurring more significant foot traffic. For longterm project recommendations,

58

USS Little Rock

RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION

students suggested demolition and site preparation for a new museum building. Finally, creating an educational STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, math) activity space will help increase youth awareness.

“This was a fantastic opportunity to create a cultural destination in downtown Buffalo that will benefit the community for generations.”

- Allison Carroll

The Naval Park is an excellent place with market demand for a museum or cultural experience. By refining the historical archive, enhancing programming, and planning for future investment, the park has the potential to become a Buffalo attraction once again.

59

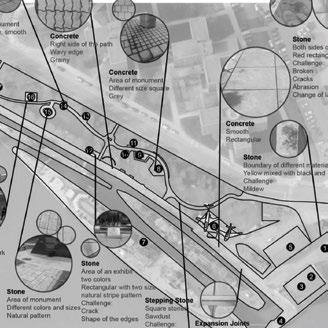

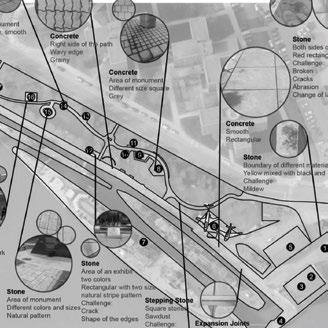

Material mapping the Naval and Military park, Zhang

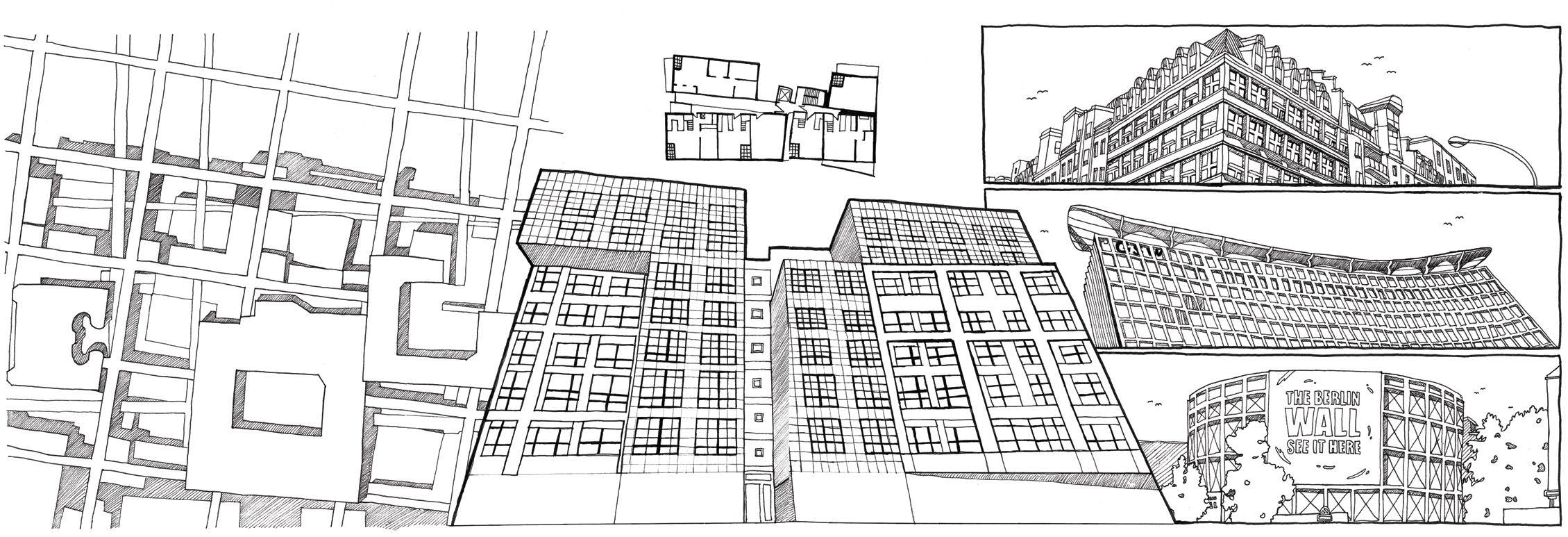

BUILDING BERLIN

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Claire Birkemeier, Ciera Chamberlain, Warren Chen

Gregory Delaney

Summer 2022

Study Abroad, Berlin

BS Arch, MArch

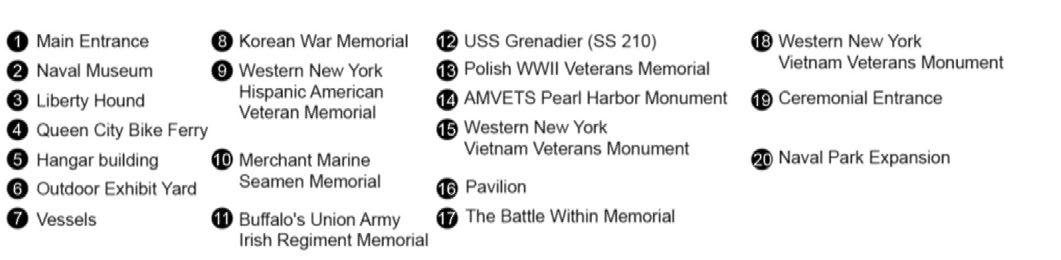

How can one drawing represent a city’s culture, programmatic complexity, and architecture? The summer study abroad experience titled, "Building Berlin," placed students in a context characterized by radical political and urban transformation. As a city once ravaged by war, Berlin offers a rich setting few other European cities could match, immersing students in the layered histories of landscape, urbanism, and architecture. Embedded in another culture, both through lifestyle and architecturally, students developed a deep familiarity with key works of historic and contemporary architecture in Berlin.

“We were complete strangers in the beginning but through the tours and completely new learning environment, we all became close friends.”

- Ciera Chamberlain

Group site visits and urban exploration allowed students to construct thematic and conceptual linkages through discussions and presentations.

Developing an architectural vocabulary alongside a critical analysis of some of Berlin’s most famous sites aided students in translating these conversations into analytical drawings.

Additionally, students revisited sites they connected with and spent the day drawing the atmosphere, neighborhoods, landscapes, and of course, the built environment. Each student then assembled a portfolio of drawings in their own representation style, developed through iterative processes. These composite drawings took on a unique, collagelike character by stitching together plans, sections, and perspectives. The drawings later served as entry points to student-led discussions on urban intensity, transformation, and form, among other topics.

Alongside their adventures throughout Berlin, students enhanced their abilities to identify and interpret the architectural influences around them. Berlin’s past and contemporary

architectural and urban assemblages gave them a greater understanding of our global metropolis.

60

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

61

Culture and housing in a divided Berlin, Chen

Modernism and The Weimar Republic, Chamberlain

Metropolis of science, knowledge and industry, Birkemeier

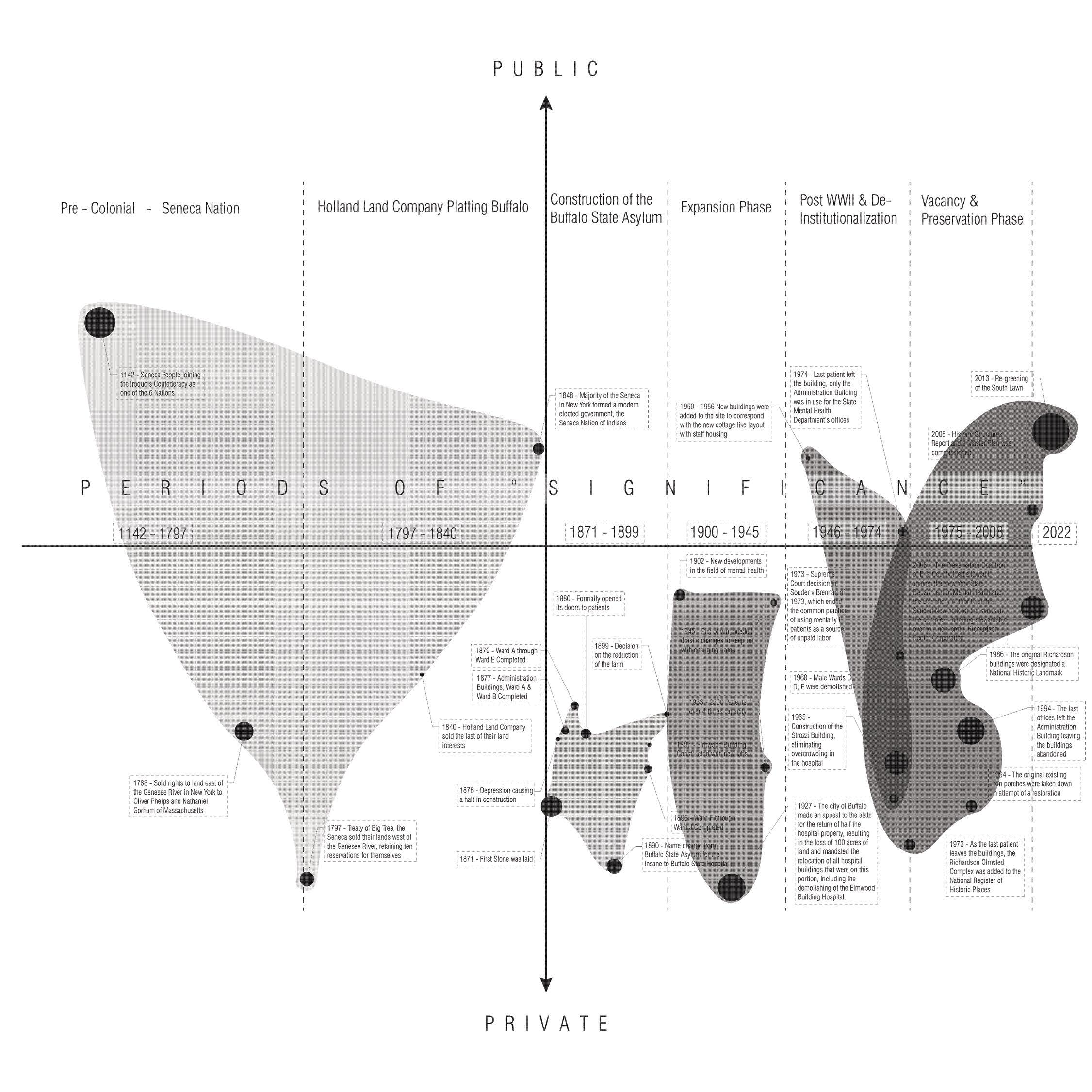

PERILS OF SIGNIFICANCE

Students:

Faculty:

Term:

Course:

Program:

Adara Zullo

Erkin Özay (chair), Nicholas Rajkovich

Spring 2022

Graduate Thesis, Architecture

MArch

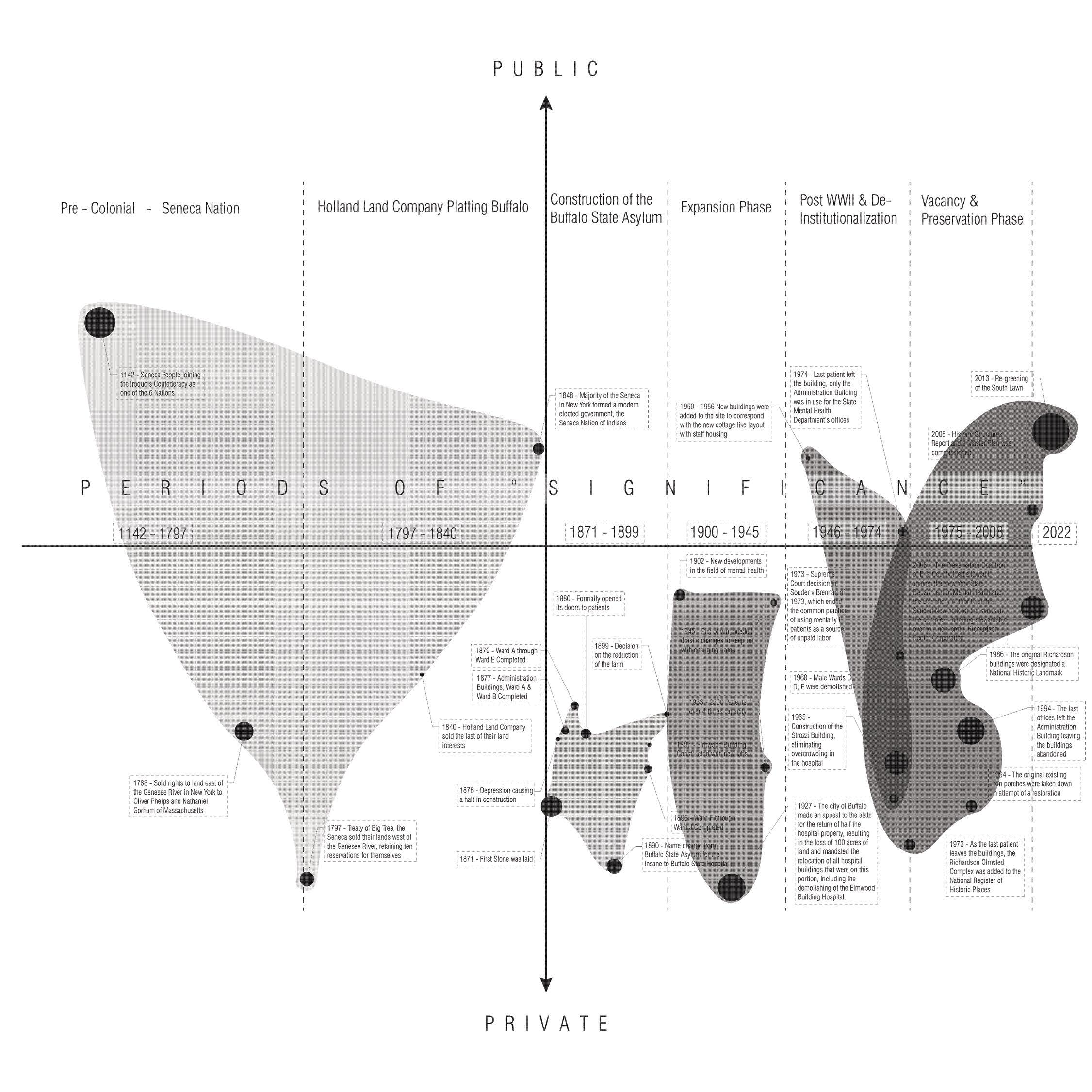

Can we think of historic preservation interventions as design constructs?

Perils of Significance focuses on the case of Richardson Olmsted Campus; a prominent Buffalo landmark with over 500,000 square feet of historic mental asylum site designed by Henry Hobson Richardson and Frederick Law Olmsted. The site was intended to be a therapeutic landscape. Each successive building was added according to the Thomas Kirkbride plan, based on a staggered corridor layout to increase access to sunlight and natural ventilation.

Through the work, Zullo unpacks the complexities behind reuse projects, providing insights into the historic preservation in the Rust Belt cities. Deliberate mapping and timeline techniques chronicle the site's layered history and probe the concept of historical significance and its operative role in shaping preservation strategies. Zullo’s thesis concludes by imagining three speculative scenarios of what the site could have looked like, if other narratives of significance had been mobilized.

Working under the advice of longtime mentors Erkin Özay and Nicholas Rajkovich, Zullo was able to feed off their passions in urban housing and climate resiliency. Their collaboration led Zullo to construct her own research methods and approach to preservation, as a stepping stone for her practice after graduating.

The research exploration first addresses the history of the Olmstedian site, dating the campus from its inception in 1872 to its state as of 2008, analyzing each successive phase of construction, expansion, post-industrialization, and preservation. Zullo argues that economic development and historic preservation initiatives must not lose sight of these complex histories and vulnerable communities that neighbor the site.

Building on a story of preservation, the thesis evaluates the site's level of significance. While the complex is slated in the national registry of historic places as a historic

building, its evolution of demolition and reconfigured site programming signifies an imminent demise of the ideals behind institutional care for the mentally ill. The Significance Matrix maps noteworthy events associated with or on the property based on what mainstream preservation narratives deem significant. The timeline begins with the transition from Seneca Nation land ownership to United States ownership in 1797 to recent interventions initiated by a private developer with inadequate oversight. This 2D matrix is paired with a 3D diagram of what has been deemed significant during the preservation process.

62

RELATIONS CULTURE EXPLORATION RIGOR OUR WORK OUR WORLD

63 Significance matrix