35 minute read

Existing Conditions

from The Greater University District Plan

by University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning, University at Buffalo

Regional Plans

A majority of the issues and opportunities within the Greater University District can be generalized into three main categories: environmental issues, transportation, and economic development. Below are plans, initiatives and organizations working on improvements and development throughout the region that deal with each of the main categories.

Advertisement

Environmental Issues and Opportunities

Between extreme industrial development and intense urban sprawl, environmental features of the Buffalo area have seen substantial lack of maintenance and pollution within the past century. However, plans, programs, and organizations are working to remediate polluted land, improve the quality of outdoor spaces, and clean contaminated water.

1. Erie County Parks, Recreation and Forestry Department

- New county-wide master plan to replace their original 2003 plan - Heightened park maintenance, improving operations and improving aesthetic and functional aspects of the parks in an economically efficient way

Improvements to park maintenance and aesthetic quality within our study area would: • Drive more people to the parks of the area which in effect would drive more people to our study area with the presence of parks such as McCarthy Park and Shoshone Park • Also allows the parks to feel like a cohesive system and would allow for the increased economic vitality of surrounding areas which would not only benefit the surrounding neighborhoods but these three municipalities as well.

2. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Buffalo, Amherst, and Tonawanda are located within the EPA’s Region 2 which services New York, New Jersey, as well as some of the US territories. The Niagara River, which borders both Tonawanda and the City of Buffalo, was designated an Area of Concern under the 1987 Great Lakes Water Quality Act with the intention of cleaning and dredging the contamination from the river basin.

3. Western New York Stormwater Coalition (WNYSC)

- EPA developed regulations to diminish the impact of CSO’s on surrounding water systems - Communities in Erie and Niagara counties joined together to develop a stormwater management program to better comply with the EPA regulations. • Established a Stormwater Management Plan to allow them to cohesively work together to comply with the regulations and allows each individual one to more efficiently comply, especially with the help of surrounding municipalities. - With the WNYSC, municipalities like Buffalo, Amherst and Tonawanda already work in conjunction with each other to manage stormwater and thus, perhaps the structure and example of the WNYSC can be applied on a broader scale to foster connections across various economic, social and political factors.

Regional Plans

Transportation Issues and Opportunities

Transportation systems connect all three municipalities and facilitate interaction between them. Looking at regional transportation plans, several existing initiatives provide possible opportunities for connection in the future.

1. New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT)

• Currently working on road improvements, safety improvements, repairs, and maintenance across Erie County • Skyway Rehabilitation/Redesign, Niagara Falls Boulevard pedestrian safety improvements, and the Scajaquada

Expressway conversion into an urban boulevard. • Traffic overhaul for major roadways which will impact the way people traverse throughout the area

2. Greater Buffalo Niagara Regional Transportation Council (GBNRTC)

- Planning organization focused on improving transportation for all modes of transportation within Erie and Niagara counties Currently developing plans the region including the Regional Bicycle Master Plan

Worked to develop plans such as: • Comprehensive Transit Oriented Development Plan • Moving Forward 2050 • Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) • Bridge NY • Pave NY • Pedestrian Safety Action Plan (PSAP) • NYSDOT Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP) and the

Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ)

- Proposal for a metro rail extension through Amherst along Niagara Falls Boulevard, Sweet Home, and Maple Road

The goal of this project is to connect downtown areas to certain parts of Amherst to promote connectivity not only between University at Buffalo’s North and South Campuses, but also throughout the Buffalo region as a whole. Financing this project by applying for federal funds through the Federal Transit Administration. The final scoping document for this project was published in May of 2019, following a series of public meetings where citizens had the chance to provide input in the design process.

Economic Development

Agencies and plans throughout the region with an emphasis on economic influx are key to the economic, social and cultural development of the area.

1. One Region Forward

• Federally recognized collaboration of many entities and institutions in Buffalo who share a common goal of promoting sustainability in the region • Addresses current issues within the Buffalo Niagara region including: population decreases, lack of growth in the city center, and lack of economic growth • The goals of the plan include promoting efficient land use, improving transportation, supporting existing housing, preparing for climate change, and making food more accessible. • Main institutions guiding this effort are the GBNRTC, the

NFTA, the School of Architecture and Planning at the

University at Buffalo, and the Buffalo Niagara Partnership.

Existing Plans in the Town of Amherst

Over the past two centuries, the Town of Amherst has evolved from small settlements surrounded by farmland to a premier residential community and activity/employment center in Western New York. The following is a summary of plans in Amherst that are relevant to the Greater University District.

1. Recreation and Parks Master Plan

- Aims to help local government meet the current and future recreation needs of the community - Developed as a tool to guide staff, advisory committees, and the Town Board in their work to maintain and enhance Amherst’s system of parks, open spaces, and recreation facilities over the next ten years.

Establishes five main goals • Improve municipal organizational structure that supports the provision and stewardship of Amherst’s parks, recreation, facilities, programs, and affiliated services. • Implement programs and service delivery through increasing awareness of Amherst’s existing recreation opportunities and enhancing programs to meet existing and future community needs. • Upgrade existing park amenities and recreation facilities to create more and better user experience, increase the utility of parks, and elevate levels of satisfaction. • Enhance the level of service provided to residents by the

Town’s parks and recreation system. • Develop new and innovative means to expand recreation opportunities.

- Adopted by the Town Board in January 2007 - Recent amendments to the plan reflect new information, ideas, and concepts encouraging mixed use following the development of new mixed-use zoning districts.

Important objectives of this plan include.. • Promoting the development and revitalization of walkable higher density, mixed-use centers surrounded by lower density development. • Encouraging revitalization and reinvestment in older neighborhoods and commercial corridors in Amherst. • Establishing a town-wide network of parks, open spaces, and greenway corridors. • Ensuring that economic development and redevelopment respect the character and quality of life of Amherst’s residential communities. • Establishing standards or performance criteria to determine community facility and service needs.

3. Eggertsville Action Plan

- Short-term actions to revitalize the major commercial areas in Eggertsville - Refocused on multi-modal transportation and decreases in automobile dependency

Five key strategies associated with this plan • Eliminating barriers to redevelopment presented in zoning codes. • Identifying the budget that the Town can undertake to support the development. • Identifying actions the Town or other public entities can undertake as partners in the redevelopment process. • Creating design guidelines to increase the quality of development and make public spaces more attractive, safe, and green.

Existing Plans in the Town of Tonawanda

Tonawanda, named by local indians, means “swift waters” referencing the powerful Niagara River. Tonawanda is home to the historic Erie Canal and just south of a natural wonder of the world, Niagara Falls, making the town a center point for activity throughout the region.

1. 2014 Comprehensive Plan Update

Focused on adapting to current trends, adding smaller plans/studies/projects made after 2005, and evolving based on the community for the next decade Steering Committee was formed in 2013 to help public planners work on the 2014 version of the Comprehensive plan through the lens of residents living in Tonawanda Community was against major changes to the comprehensive plan in order to maintain the small town appeal of the community Planners held a presentation on the comprehensive plan to the public to discuss specific details on the expected changes to the plan and methods of implementation This allowed the public to become accustomed to the changes while still keeping the small town appeal

2. Weatherization Program

Provides low income homeowners with a home audit to help residents evaluate what weatherization improvements can and should be made Residents are eligible for up to $6,000 in repairs for unsafe boilers/furnaces, insulating exterior walls, and replacing broken windows, amongst other repairs. Provides incentive for homeowners to become more energy efficient, which improves the energy efficiency of the whole region.

3. Zombie Home Program

Implemented in 2017, and requires lending institutions to maintain vacant properties that were the subject of a foreclosure action in accordance with NYS property maintenance codes. Under the new law, the “housing lenders are subject to a $500 fine for each day the property remains in violation” (Zombie Home Law) The goal of the Zombie Home Program is to eliminate the decrease in property value due to vacant homes in Tonawanda

Existing Plans in the City of Buffalo

The City of Buffalo, while in severe decline in the late 20th century, has been experiencing recent and significant revitalization and investment to make the city more livable for residents and an enjoyable destination for visitors. The city’s plans and initiatives aim to continue revitalizing the region, especially in historically underinvested neighborhoods.

1. Brownfield Opportunity Area (BOA)

Funded from NYS to the City of Buffalo in 2011 to plan for the revitalization of underutilized, vacant, and brownfield sites by establishing a vision of redevelopment Aimed at revitalizing areas afflicted with economic distress and blight from industry, transforming them from forgotten or hidden communities into thriving ones within New York State Identifies 46 potential brownfields that are unique opportunities for community transformation and development Establishes strategies to bring life to the region, both environmentally and economically, including zoning updates according to the Green Code

2. East Buffalo Good Neighbors Planning Alliance (GNPA)

- Vision for a renewal of the East Side of Buffalo, NY

- Examines in-depth neighborhood analysis and demographic data for five unique neighborhoods in East Buffalo: Broadway-Filmore, Kaisertown, Lovejoy, Babcock, and Emerson

Goals include: • Incorporating diverse individuals and groups in community improvement process • Establishing new partnerships within the community • Improving conditions of the built environment such as housing, education, and recreation • Improving public policies and services that impact the community

3. Lower East Side Weed & Seed Program

Program designed to reduce gun violence and prevent other violent crimes in targeted and high-risk neighborhoods in the city. Helped push for the saving of local elementary school that was near closing Utilizes a Prioritization Tool: Helps members label which goals and strategies were the most important, and provide a timeline for implementation, and sources of funding from different organizations Used an evaluation process for each goal and strategy through meetings in each of the five GNPA communities each year to evaluate their neighborhood plan’s current status

The G.U.D. represents a center of significant economic, social and cultural potential. There are a few existing plans, organizations and initiatives within the G.U.D. that align with this project’s four goals.

1. University Heights Tool Library

• Volunteer run, and member driven non profit tool-lending library located off Main Street • For a small annual fee, members can borrow from the 3,000+ tools in the library • Open to individuals, organizations and businesses • CoLab next door offers workshops to teach residents how to utilize the tools in the library • Library creates a sense of community while encouraging local individuals to repair their homes and/or businesses, which can improve community aesthetics.

2. Northeast Greenway Initiative

Established by the University District Community Development Association (UDCDA) Spearheading development of the Tonawanda Rail Trail extension into Buffalo’s east side. Goals include increasing the quality of life within the area in addition to inter-municipal connectivity

(Left) University Heights Tool Library

(Right) Concept map from the UDCDA for the Northeast Greenway Initiatative (From the UDCDA)

Demographics

Understanding the existing neighborhoods, and building off of previous knowledge of the planning goals in the area establishes what issues and opportunities lie within each municipality as well as across municipal borders. Information including, demographic characteristics, businesses in the area, housing characteristics, and neighborhood crime rates, aid in determining best actions for inter-municipal cooperation. Land Use and Zoning regulations highlight how a site functions not only for the residents of the area but also in the context of the municipality it exists in. These regulations also have impacts on the cultural and political nature of a municipality, as evident in the University Heights area. From roads to greenspaces, a neighborhood’s ability to move, utilize and succeed in the space depends on this infrastructure. Looking at the three municipalities one can establish three categories to classify infrastructure throughout the region including natural features, architectural character, and physical infrastructure.

Town of Amherst

Population: 125,659 Gender ratio: 48% Male vs 52% Female Average Household Income: $92,153 Housing characteristics in study area: Amherst has the most homeowners and Family households as well as the highest home value. Housing Characteristics: Amherst has the most homeowners and family households compared to the other municipalities The city violent crime rate for Amherst in 2016 was lower than the national violent crime rate average by 79% The city property crime rate in Amherst was lower than the national property crime rate average by 30% within the analyzed sections

Town of Tonawanda

Population: 71,939 Gender ratio: 47% Male vs 53% Female Average Household Income: $68,351 Housing characteristics in study area: A majority of people are homeowners with small households that have values of around $116,50 The crime rate in Tonawanda is 24 crimes per 1,000 residents. Chance of becoming a victim of violent or property crime in Tonawanda is 1 in 41. Based on FBI crime data, Tonawanda has a crime rate that is higher than 90% of the state’s cities and towns of all sizes. The chance that a person will become a victim of a violent

City of Buffalo

Population: 256,304. Gender ratio: 48% Male vs 52% Female • Average Household Income: $51,605 Housing characteristics in study area: A majority is rental • property with the least amount of families occupying its homes compared to the other locations. The majority of the households are only 1 person with home values the lowest • • crime in Tonawanda is 1 in 331. Crime: Buffalo has one of the highest crime rates in America compared to all communities of all sizes. Chance of becoming a victim of violent or property crime is 1 in 20 Buffalo is one of the top 100 most dangerous cities in the USA. According to NeighborhoodScout’s analysis of FBI reported crime data, the chances of becoming a victim Buffalo is 1 in 98.

80.01

80.03

46.01 93.01

93.02 94.01

95.01

46.02

45 43

Demographics

These two graphics represent the extreme racial disparity within the project area. A majority of the African American population resides below UB’s South Campus while most of the white population resides above the campus. Moving forward in the design, it is crucial to implement strategies that reduce gentrification and encourage movement across census tracts.

80.01 80.03 93.01 93.02

Graphics go here

46.01 46.02

45 43 94.01

95.01

46.01 46.02

45 43

(Left) This graphic represents the median household income for the region. A majority of the tracts within the region make more than ~$40,000 USD. However, it is important to note the economic 80.01 93.01 93.02 Graphics go hereGraphics go here disparity between Buffalo and Tonawanda/Amherst. (Right) This 80.03 graphic represents the median age for the area with a majority of the 46.01 people in Tonawanda and Amherst 46.02 being above the age of ~40 and the median age of the Buffalo 45 43 areas being much younger.

94.01

95.01

Study Area Land Use & Zoning

AMHERST LAND USE

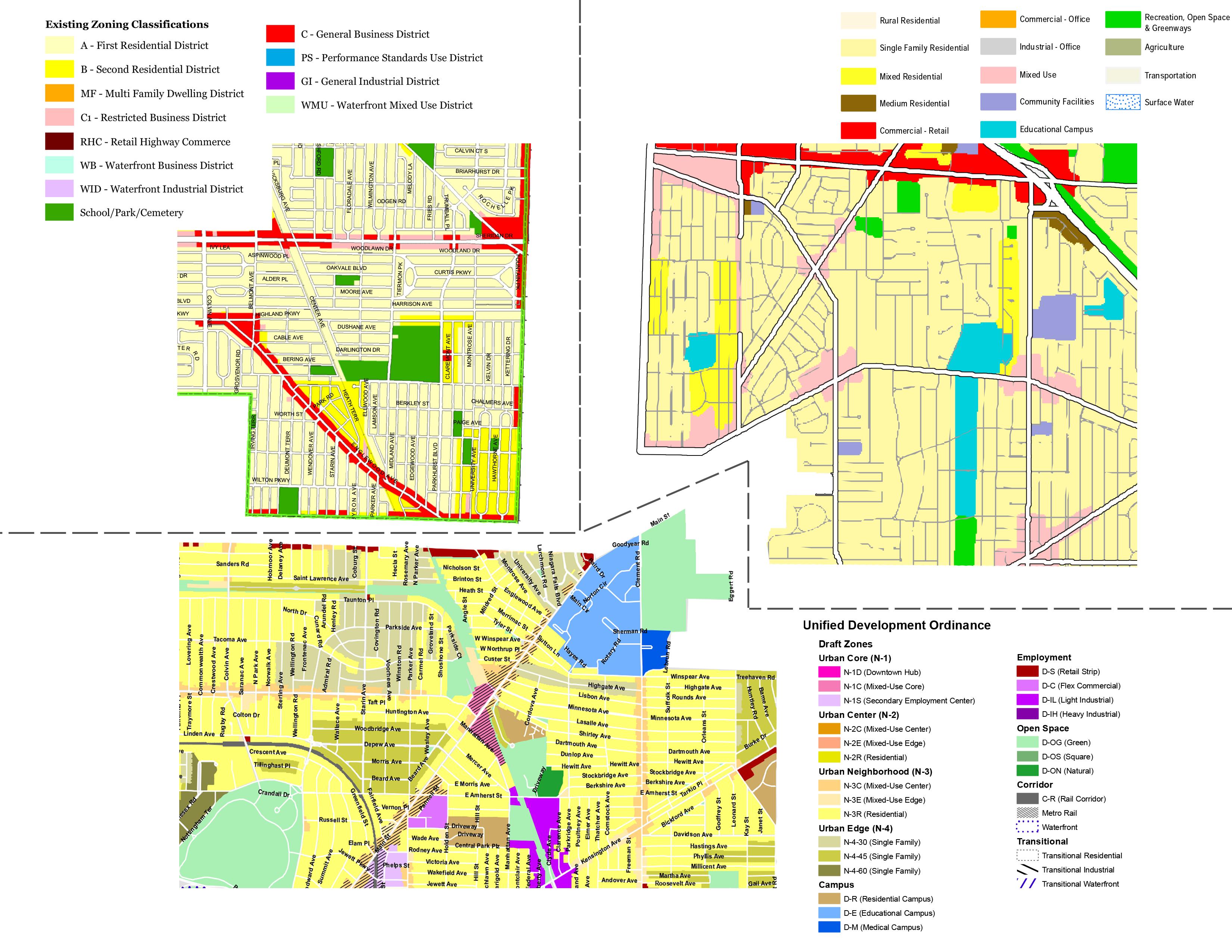

TONAWANDA ZONING

BUFFALO ZONING

The Infill Frontages are established as an overlay

Amherst Land Use and Zoning

mechanism to supplement the standards in the underlying district. These frontages are applied to all street-facing block faces where designated on the Zoning General Official Zoning Map. Where no frontage is mapped on the Official Zoning Map, the General Frontage applies. Town of Amherst zoning includes several categories including The frontage introduces additional dimensional residential, commercial and industrial. Unlike the zoning in Buffalo, standards to Infill Districts including building setbacks, Amherst’s categories account for density along with usage. What is parking setbacks, story height, transparency, most unique about Amherst’s zoning is their new Mixed Use Zoning pedestrian access, and streetscape. Districts. These districts introduce mixed-use centers that encourage a mix of land uses from shopping, working, recreation and residential. rontages However, these districts are not mapped as part of the overall town zoning map, which presents opportunities when applying for zoning The following Infill Frontages are established. Village changes. This new zoning includes infill districts and building frontages to enhance the pedestrian experience. It also conceptualizes retrofit districts and frontages that introduce larger parcels to create a blockAGEs The General Frontage provides for a walkable like structure, which would enhance movement and usage of the mixed-use street, moving the building up near site. There are several opportunities to assimilate mixed-use buildings the back of the sidewalk, and providing for a into the Greater University District, especially with University Plaza. moderate build-to percentage.

The Village Frontage provides for a walkable General retail street, moving the building up to the back of the sidewalk, and providing for a high build-to percentage, ensuring a "main street" environment.

Green

Land Use

Single family homes remain the most dominant uses of land acres, compromising of about 36.4% of the overall land space. Next to that category is the vacant land, which represents almost 18.9% of the Town’s land. Industrial Developments and Commercial offices joined together accounts for approximately 7.4% of the total land. Back in 1975, Amherst was mostly known as a residential community, but over the past 2 decades, it has risen to be known as the center of most regional activities that vastly complements the City of Buffalo. The UB North Campus has also proven to be a very beneficial and major institutional land form present in the town.

Traditional character: corridors located within higher intensity centers and older neighborhoods. Suburban character: corridors serving newer residential subdivisions, nonlocal traffic and automobile oriented development. Commercial character: corridors with an established linear commercial development pattern. Rural character: corridors possessing unique visual character due to their rural and/or scenic qualities.

The Green Frontage provides for a deeper setback, moving the building back from the street, Village but not allowing parking between the building and Picture goes here esidential

The Residential Frontage provide a low buildto percentage and modest transparency requirements, allowing for buildings that are closer in mass and scale to large traditional

residential

Picture goes here

Tonawanda Land Use and Zoning

Zoning

The Zoning ordinance establishes separate geographic districts for residential, business, industrial and waterfront districts. In addition, there are certain lands, occupied by schools, parks or cemeteries, which while having a geographic designation, do not have corresponding zoning regulations and essentially are un-zoned. This map depicts the current zoning districts.

Districts Include: • Residential Districts: First Residential District (A), Second

Residential District (B), M-F Multifamily Dwelling District (M-F) • Commercial Districts: C-1 Restricted Business District (C-1),

General Business District (C), Neighborhood Business District (NB)

In 2014, two new commercial districts were proposed by the Planning Board. The proposed C-2 Commercial District District is intended to encourage the establishment of land uses compatible with both the surrounding uses primarily along Military Road. Allowed uses in the C-2 District are similar to those in the C District, plus Automotive uses, Gasoline Stations, Stand-alone Used Vehicle Sales, light manufacturing/industry, and wholesale and warehousing businesses. The proposed TND-Traditional Neighborhood Design District is intended to encourage a mix of commercial establishments and consumer services that serve the immediate residential neighborhood; fitting into the context of the existing neighborhood in terms of scale, architectural style, and size of lots and structures. The allowed uses in the TND District are similar to those in the C District, however a larger number are only allowed with a Special Use Permit enabling the Town to better consider how a specific proposed use “fits” in a specific location. All the business districts include regulations governing yards, maximum lot coverage, and landscaping.

Land Use

The Town of Tonawanda’s current 2014 Comprehensive Plan takes a deeper look into its predecessor plan (2005) in to adapt changes in reaction to developing trends in community and urban planning.

Various recommendations, strategic plans and projects were also updated such as, The Old Town Plan, The Local Waterfront Revitalization Area and The Tonawanda Brownfield Opportunity Area. The overall aim of this update was to achieve some of the goals listed below:

Maintaining the safety, enhanced quality of life, public health and the overall sustainability of the town of Tonawanda as a whole. Supporting the preservation of the town’s environmental resources and the continuous remediation of former waste sites in order to preserve the soil Maintaining and enhancing the vitality of neighborhoods and neighborhood centers, in order to retain a diverse stock of residential properties and facilities that meets the basic needs of all residents Promoting a smart, well organized and constant economic development opportunities Promoting a safe and efficient multi-modal transportation system for the residents Ensuring coordinated, high quality, well-maintained and cost effective facilities and services that are required by the general residential population and businesses properties in a sustainable community environment. Enhancing the efficiency and efficacy of Town government and planning and strive to improve interaction with other communities and agencies in order to understand and better the community as a whole.

Buffalo Land Use and Zoning

Zoning

The Buffalo Green Code is widely known as a place-based economic development strategy which was designed in order to implement the city’s Comprehensive Plan. It consists widely of the first citywide land use plan which dated back to 1977, and the first zoning rewrite since 1953. It included the Brownfield Opportunity Area Plans, city’s Homestead Urban Renewal Plan and local waterfront Revitalization into a singular vision that will help guide and promote the Buffalo’s physical development over the next 2 decades.

Goals of the Green Code:

Encouraging investments by implementing rules for development predictable, placing aside land for job creation and establishments in particularly key districts and corridors, which is supported by efficient and cost-effective infrastructures, allowing for the productive, adequate and timely reuse of vacant lands. Promoting land use while promoting a full array of transportation choices to help us conserve energy and transportation patterns that encourage transportation and compact development. Creating the necessary and appropriate conditions for Buffalo to grow again, aiming at making the city attractive to visitors and newcomers by meeting the expectations and aspirations of those who currently reside in the city’s frame at the moment, while sharing the benefits of city life equitably, with this current generation and those to come in the later future.

Picture goes here

Land Use

These zones make up the land use districts within the City of Buffalo: Neighborhood Zones: Downtown/Regional Hub, Mixed-Use Core, Secondary Employment Center, Mixed-Use Center, Mixed-Use Edge, Residential, Mixed-Use Center, Mixed-Use Edge, Residential, SingleFamily, Downtown Entertainment Review Overlay Neighborhood zones address the various mixed use, walkable places found throughout the City of Buffalo which range in character, function, and intensity from the most diverse and intensely developed places to the least.

District Zones: Residential Campus, Medical Campus, Educational Campus, Strip Retail, Flex Commercial, Light Industrial, Heavy Industrial, Square, Green, Natural District zones correspond to specialized places serving a predominant use, such as retail centers, college campuses, or industrial sites.

Corridor Zones: Metro Rail, Rail, Waterfront Corridor zones are linear systems that form the borders of, or connect, neighborhoods and districts. They are composed of natural and manmade components, ranging from waterfront to railways and transit lines.

Picture goes here

Municipal Transportation

Town of Amherst

The Town of Amherst’s Comprehensive Plan (2015) provides existing conditions for transportation and compares them to the proposed streetscape redesigns. The town’s goals are to enhance the streetscape atmosphere through:

Adding left turn lanes at major intersections Incorporating signal timing to improve traffic flow Raising the landscaping median Widen planting strips to provide visual buffer Providing planting pits within sidewalks Consolidating signage to avoid clutter

The report also calls for street narrowing to dissuade speeding, and more bicycle and pedestrian friendly atmosphere. More crosswalks, tree lined streets, and median greenery are examples of what the public would like to see built into their towns streets.

City of Buffalo

The City of Buffalo’s Transportation Demand Management Plan (2017) provides an overview of the transportation roadway network. This plan is built to include strategies in improving traffic volumes and efficiency.

Some strategies include: • Parking cash-out programs or unbundled parking/market rate pricing. • Shared parking arrangements. • Enhanced bicycle parking and services beyond minimum requirements. • Support for rideshare and bike sharing services and facilities. • Carpooling or vanpooling programs or benefits. • Free or subsidized transit passes, transit-to-work shuttles, or enhanced transit facilities, such as bus shelters. • Guaranteed ride home programs

Town of Tonawanda

The Town of Tonawanda’s Comprehensive Plan (2014) provides goals to improve transportation that emphasize pedestrian and bicycling connectivity throughout the town. In particular, they discuss proposals to better connect off-road multiuse paths with current and proposed bike lanes. With relatively dense, centrally located residential neighborhoods and streets in grid layout, the plan seeks to connect the peripheries of the town to the center. Their transportation plan focuses primarily on preserving the existing roadway network, improving mobility and accessibility, and supporting economic development.

Picture goes here

= State/County Roads = Arterial Roads = Local Roads

Regional Tranportation

The Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority (NFTA) offers public transportation in Erie and Niagara Counties in the form of light rail and bus. The light rail, also known as the Metro Rail, was built in 1979 was intended to link Amherst and Buffalo but was never completed due to the region’s economic decline. Within the last year the NFTA has begun planning initiatives to extend the light rail through UB’s North Campus in Amherst and to the I-990. The bus serves Amherst, Buffalo and Tonawanda, but more comprehensively serves the Buffalo area. Other transportation options in these regions include bike sharing, private taxi services, and ridesharing such as Lyft and Uber. Zipcar offers a car sharing program and can be accessed in many locations in the city. Overall, Tonawanda and Amherst are more car dependent than Buffalo and do not have continuous alternative transportation networks. Walking in the area is manageable; biking infrastructure in traverses the LaSalle station downtown Tonawanda. The

Pedestrian & Bicycle Infrastructure

Pedestrian and bicycling infrastructure in the Greater University District is used by a relatively large percentage of the residential population. However, there are many gaps in the walking and biking network.

• Amherst walk score: 56

- The Town of Amherst has a basic Sidewalk Snow Relief program. It has snow removal assistance along Niagara Falls boulevard, none Parking is a major topic in the community because of how amount of parking, the location, parking violations, etc. Due our group decided to focus on looking in ecodes. Ecodes are

on Main street (which is within study area) - No bicycling and pedestrian plan in place.

• Tonawanda walk score: 69

- Tonawanda rails to trails connect Buffalo to Tonawanda through old rail corridor. - Complete streets policy adopted

Buffalo walk score: 72

In the Summer of 2017, UBRI (University at Buffalo Regional Institute) performed a neighborhood overview plan for University Heights, outlining many of the existing conditions. The report shows that 10% University Heights residents walk to work, while 1% bike. Similar to Walkscore, the plan highlights the variety of community services and historic spaces in the area, such as community gardens, block clubs, schools, churches, etc, demonstrating that there are many destinations within close proximity to residences. Violent crimes declined 17% very lacking. Notably, there are only 2 bike share stations that are both on the UB South Campus, which may feel inaccessible to the general public. There are two bike routes in the area. The first is the Tonawanda Rails to Trails that second is a designated route that eventually turns into a bike lane from Bailey through Rosedale to UB North Campus.

Parking Conditions

reliant people are on automobiles, especially in places that are more suburban or rural. While parking conditions composed of how the pavement wears over the years is important there are other equally important elements such as to the amount of variables that come with parking conditions from 2009-2016, suggesting that it is safer to walk around outside.

the zoning codes kept on an online website. Amherst, Buffalo, and Tonawanda all have their own codes based on what is deemed necessary for the betterment of the town/city.

Amherst Existing Assets

Parks and Recreation

The Town of Amherst, with its nearly 53.58 square mile area, has a multitude of parks and public spaces.. To better align to the University Heights area, the parks analyzed were within a few miles of the study area, which include Garnet Playground, Eco-Park, Sattler Field, Dellwood Park, and Campus Drive Park. Garnet Playground, the largest park in the area, is roughly 13.5 acres in size featuring 2 baseball diamonds and 2 public buildings. Eco Park is approximately 0.7 acres in size and features an open circular greenspace with a playground. Sattler Field is roughly 1.55 acres in size with two baseball diamonds. Dellwood Park is 4.2 acres with 2 baseball diamonds and a playground. Finally, Campus Drive Park is around 2.1 acres in size with one baseball field and a large public greenspace.

Picture goes here

Picture goes here

Garnet Playground Housing along Hemlock Rd.

Architectural Character

Amherst has a majority post World War I housing throughout its 53 square miles, with most of the housing built around the late 1940s to early 1950s. Average square footage of houses range from 1,000 sq ft to 2,000 sq ft with most houses being single-story single-family bungalows. Businesses throughout the town are mostly single-story buildings with a few repurposed former homes.

Public Infrastructure

In terms of physical infrastructure, the lighting throughout Amherst presents a huge issue toward safety and walkability for which most of the lighting is unevenly distributed. A majority of the lighting lies on major thoroughfares with lights located every .02 miles. Moving onto local streets and arterials, the lighting gets further dispersed. This same issue with lighting can be applied to various street signs throughout the town, specifically the connection between bicycle signage and on-street paint signage. While there are signs on the road indiciating bicycle movement throughout the area, some parts of Amherst do not have the associated paint on the road for designated bicycle lanes. The sanitary sewer system and stormwater system are separate from one another unlike Buffalo’s system. The sanitary sewer system still takes a bit of the stormwater runoff, but a more manageable amount due to a separate stormwater system. These two systems most often run parallel with one another for most of Amherst. The University Heights area lies within Amherst’s Sewer District 1, which covers the south-western corner of Amherst boundaries.

Picture goes here

Sheridan Drive recieves heavy amounts of traffic with little emphasis on pedestrians

Tonawanda Existing Assets

Parks and Recreation

One of the most opportunistic aspects of connecting Tonawanda to Amherst and Buffalo lies within its Rails-to-Trails. The Rails-to-Trails currently runs 4.5 miles directly from Shoshone Park in Buffalo all the way to North Tonawanda. Therefore, this path presents an extreme opportunity to increase connectivity for not only the residents of the region but also foster inter-municipal connectivity as well. Other Tonawanda parks within proximity to our site include Lincoln Park, Curtis Park and Ellwood Park. Lincoln Park, the largest of the three at 48 acres, features a wide array of amenities including a large forested area, seven baseball diamonds, a recently updated pavillion, an arena with an ice skating rink and two pools. In 2016, there was a “Lincoln Park Green Initiative” which restructured the dynamic of the land and helped turn old railroad area into public green space. The entire project received just under a million dollars in funds from NYS Environmental Facilities Corporation, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, and a Community Block Grant. Slightly north of Lincoln Park lies Curtiss Park, a 3 acre playground park with a large greenspace. Finally, west across the Rails-to-Trails lies Ellwood park which is a small 2 acre park with a small playground and small recreation building. These parks represent an opportunity to connect greenspaces throughout the GUD and promote traversing throughout the area.

Architectural Character

In terms of architectural character, Tonawanda has a majority of post World War 1 housing in the area. Most of the housing was built around the late 1940s to early 1950s. Houses are approximately 1,000 square feet to 2,000 square feet in this area. Most homes are single-story singlefamily bungalows in the neighborhood while businesses are typically single-story buildings with a few repurposed former homes. There are very few houses that are over 2,500 square feet in area. The Historical Society Museum is the oldest building in Tonawanda and was first used as a german evangelical church but was reopened as a museum in Tonawanda in 1970. The building was made of clay bricks from Ives Pond Area and the Bell on the top of the building was presented to Saint Peter in 1934 in anticipation of 105th anniversary of congress.

Public Infrastructure

Tonawanda’s existing physical infrastructure places heavy emphasis on wastewater management, especially given its proximity to the Niagara River. According to the Water/Sewer Maintenance Department, the Town of Tonawanda has “300 miles of sanitary sewer and 270 miles of storm sewer.” Much like the other two municipalities, Tonawanda deals heavily with the impact of Combined Sewer Outflows and works to abide by regulations set forth by federal agencies to regulate it. As of the 2014 update to the Town’s comprehensive plan, in cooperation with the NYSDEC the Town has implemented the first 3 of the 4 phases of work to address 92 locations where CSOs occur.

Picture goes here

(Above) Tonawanda Historical Society Picture goes here (Below) The entrance to the Tonawanda Rails-to-Trails

Buffalo Existing Assets

Parks and Recreation

Beginning with Buffalo’s natural features, the history of the city’s parks and green spaces is extensive and extremely influential. With Olmsted’s park system and endless improvements, the City of Buffalo presents a unique opportunity to bring this history to the other two municipalities. Green spaces in Buffalo range from large and populous spaces (Delaware Park, McCarthy Park, Grover Cleveland, etc) to small, neighborhood spaces (Tyler Street Garden, Burke’s Green, etc). Delaware Park is the most prominent and well-known of these greenspaces, with pedestrian paths and a large water feature called Hoyt Lake. There is also a restaurant overlooking the park called The Terrace where there has been a variety of programs including live music, wedding receptions, and private parties. McCarthy Park has a playground and accommodates sports such as tennis & baseball. Grover Cleveland is a well-maintained golf course and the largest green parcel within the study area. Smaller pocket parks include Tyler Street Community Garden (University Heights Collaborative) and Burke’s Green. From a connective point-ofview, one necessity for the greenspaces in Buffalo, is for the already existing park system in South Buffalo to connect to North Buffalo and thus the rest of the region. By connecting a park like Delaware that already has connections to the park system to other larger greenspaces like McCarthy and Grover Cleveland, while utilizing the small greenspaces as connection points, it would open up Buffalo’s park system throughout the region rather than its current secluded state.

Map showing Shoshone/Minnesota Linear Park in the North and McCarthy Park in the South

Architectural Character

Many of Buffalo’s buildings are on the National Registry of Historic places including the Albright Knox Art Gallery, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Darwin Martin House, and the Buffalo History Museum. The Albright Knox Art Gallery was designed by Edward Green in the Greek Revival style . Over the years, there have been renovations and additional buildings added to accommodate different types of exhibits. The most recent renovation plan has raised $131 million and will start later in 2019 (ARTnews Buffalo). Another significant Buffalo structure is the Buffalo Court Building downtown. This was designed by Roswell E Pfol and is an excellent example of Brutalist architecture in the city. City Hall is one of Buffalo’s most well-known architectural gems. Designed by John J. Wade, this Art Deco building has been preserved and it is still used for its original purpose (buffaloah. com). Aside from being a beautiful example of art deco architecture, it also features an observation deck to view the city from the top floor. The brick portion of Niagara Falls Boulevard is a historically protected street and serves as significant connection between Buffalo and Tonawanda.

Tyler Street Community Garden

Buffalo Existing Assets

A tributary of the Buffalo River, Cazenovia Creek forms in southern Erie County, traveling through various towns before entering the City of Buffalo. It flows through South Buffalo neighborhoods and forms the prime water feature of Cazenovia Park, part of the City’s Olmsted Park system. The creek can overflow and create flooding issues for nearby residents during significant wet weather events. (Above) Darwin Martin House by Frank Lloyd Wright Buffalo has already taken a number of steps to address (Below) City of Buffalo City HAll water quality concerns in the region. The Buffalo River Ecological Restoration Master Plan provides a framework for addressing habitat related impairments in the lower Buffalo River watershed. The Great Lakes Legacy Act Sediment Action Plan addresses many concerns around the Buffalo River Area of Concern. The draft Local Waterfront Revitalization Program proposes waterfront improvement projects, and establishes a program for managing, revitalizing and protecting resources along Lake Erie, the Niagara River, the Buffalo Public Infrastructure River, Scajaquada Creek, and Cazenovia Creek. Buffalo Sewer’s Long-Term Control Plan is part of this region-wide Physical infrastructure emphasis and improvements, much like the natural features, exist effort to improve water quality and habitat. mostly in South Buffalo. This leaves a large gap between downtown Buffalo and other places Tree Canopy Cover like Tonawanda and Amherst. Buffalo’s current water management plan, visualized in the Raincheck plan by the Buffalo Sewer Authority, only emphasizes a need for increased green Trees intercept, absorb and filter stormwater. Increasing the tree canopy in Buffalo can help to reduce the amount infrastructure in the downtown area. The only improvements made in North Buffalo revolve of stormwater reaching the combined sewer and improve around the inclusion of rain barrels throughout the University Heights area. Other improvements the quality of local waterways. like green parking lots and green streets, exist mainly in southern Buffalo. Looking at the impervity In addition to stormwater benefits, trees provide other of surfaces in North Buffalo, more than half of the surfaces are impervious and thus lead all benefits relating to equity goals and quality of life, the water toward the Niagara River which presents huge environmental issues given the CSO system. By including more green infrastructure in northern Buffalo, it allows the water to be better managed during storm events and prevent sewer-stormwater outflow (Raincheck Buffalo). including reducing urban heat island effect, improving walkability, increasing access to green space, and traffic calming. These many benefits of trees were also considered in the analysis of green infrastructure opportunities in Buffalo. Buffalo’s existing tree canopy in each priority CSO basin was analyzed to determine the amount of canopy within the public right of way and the amount of canopy on private land. The overall canopy cover for Buffalo is 14.6% or 3,836 acres of canopy. Most of the priority CSO basins have canopy cover on par with the city average. CSO Basins 27 & 33 are well below the city average. The city overall has more than 45,000 vacant acceptable street tree spaces. Increasing the canopy cover within the City and particularly within the priority CSO Basins would assist in meeting Buffalo Sewers stormwater goals.

Impervious surfaces depend on a city’s density, topography, & land use.

BUFFALO, NY

Syracuse, NY

Pittsburgh, PA

41%

34%

56%

Indianpolis, IN

28%

Scranton, PA

23%

Picture goes here City-Wide Impervious Area GIS Data

A city’s urban tree canopy assists with stormwater control and makes neighborhoods more livable.

Scranton, PA

Pittsburgh, PA

42% 55%

Indianapolis, IN

33 %

Syracuse, NY

28%

BUFFALO, NY

14.6%

Canopy Cover of Benchmark Cities

Urban Tree Canopy Assessment University of Vermont & US Forest Service Taken from the Buffalo Raincheck Plan