COV.May09.v.1d:cover.june.pp.corr 06/04/2009 16:02 Page 1

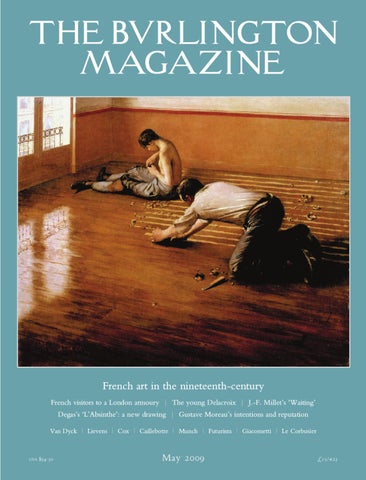

French art in the nineteenth-century French visitors to a London armoury | The young Delacroix | J.-F. Millet’s ‘Waiting’ Degas’s ‘L’Absinthe’: a new drawing | Gustave Moreau’s intentions and reputation Van Dyck | Lievens | Cox | Caillebotte | Munch | Futurism | Giacometti | Le Corbusier

USA

$34·50

May 2009

£15/€ 23