9 minute read

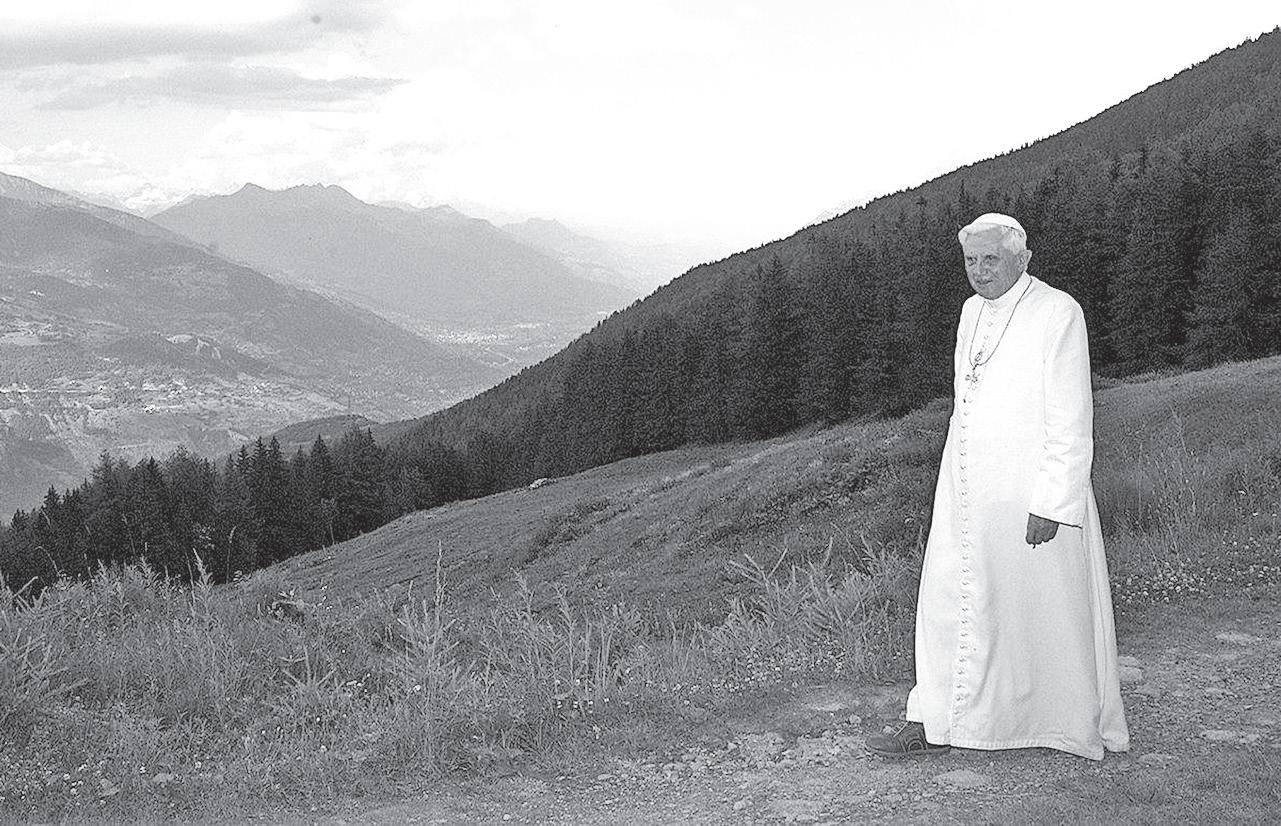

Calls for Pope Benedict’s sainthood make canonizing popes seem the norm

LIKE many others around the world, I watched the funeral of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI live on the Internet. Before the service began, an unexpected announcement came over the loudspeakers requesting that members of the assembled crowd refrain from raising any banners or flags.

Nevertheless, toward the end of the liturgy, at least one large banner was displayed, reading “Santo Subito,” an Italian phrase that means “sainthood now.”

Identical signs were raised at the 2005 funeral of Pope John Paul II, who was officially canonized nine years later. The connection between these events has not gone unnoticed, leading some to raise questions about expectations that every future pope will be acclaimed as a saint.

As a specialist in Catholic liturgy and ritual, I know that in the contemporary church, no one, from popes to laypeople, is ever officially proclaimed a saint immediately after death. The way that saints are chosen has changed over the centuries, and that has affected the “wait time” between death and canonization.

Antiquity and early Middle Ages

IN the early church, Christianity was illegal in the Roman Empire. Those who were executed after refusing to renounce their faith were venerated immediately after their deaths; individuals or small groups would pray at martyrs’ graves, believed to be places of special holiness, where heaven and earth meet.

Those who were imprisoned for their faith but released—called confessors—were venerated by their communities in the same way.

After the legalization of Christianity in the early fourth century, other men and women who had lived lives of exceptional virtue were also recognized as holy ones and called saints.

For the next several centuries, most saints were venerated at the local level.

Bishops often approved many of these saints for wider regional veneration. Just before the year 1000, Ulrich of Augsburg, an ascetic German bishop, became the first saint to be officially canonized by a pope.

By the early 12th century, it was left to the the popes to officially proclaim most saints. In later years, popes insisted on this exclusive prerogative.

The later Middle Ages

ALTHOUGH the cases—called causes—of those already locally revered for their holiness were brought to Rome for examination and approval, there was no set timeline for the process.

However, no highly regarded Christian was canonized immediately after death. Instead, the investigation of their cases could take years to reach a conclusion.

The proclamation of St. Anthony of Padua in the 13th century was the fastest canonization during this period. A member of the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor—meaning Little or Lesser Brothers—this young priest was acclaimed for his simple, eloquent preaching.

Anthony died in 1231 and, because of his reputation, was canonized less than a year later, even faster than St. Francis of Assisi, the renowned founder of the Franciscans.

Only two years after Francis’s death in 1226, Pope Urban IX proclaimed him a saint because of his “many brilliant miracles.”

Other causes could take longer. For example, the canonization of St. Joan of Arc took almost 500 years.

During the Hundred Years’ War between England and France in the 14th and 15th centuries, this French teenager experienced visions of saints directing her to liberate France. She helped win an important battle but was later captured and convicted by the English of heresy.

In 1431, Joan was executed by being burned at the stake. In 1456, Pope Callixtus III declared Joan of Arc innocent of heresy, and she continued to be venerated by the French for centuries afterward.

Increasing French nationalism played a role in advancing her cause, and Pope Benedict XV proclaimed her a saint in 1920, praising her long-standing reputation for holiness and her life of “heroic virtues.”

JARO’S FEAST OF OUR LADY OF CANDLES

Iloilo devotees attend the Mass at Jaro Cathedral, the National Shrine of Our Lady of the Candles in Jaro, Iloilo City, on February 2. The day celebrates the annual feast of the district of Jaro in Iloilo City. Ilonggos from all over Iloilo province would visit the Jaro Cathedral to honor Nuestra Senora de la Candelaria (Our Lady of Candles), the patron saint of Jaro. The title commemorates Mary’s ritual purification during the Presentation of Jesus. It’s origin was when Halakha (Jewish law) ordered that firstborn sons be redeemed at the Temple in Jerusalem when they were 40 days old. The feast day is also known in the Catholic Church as the “Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ” because it commemorates the first time His mother, Mary, brought Him to the temple.

Modern changes

IN the 16th century, the canonization process became more standardized. The process of canonizing saints was handled in one specific office, the Sacred Congregation of Rites, part of the overall papal bureaucracy, the Curia.

Later, in the 17th century, Pope Urban VIII set a 50-year waiting period between the death of a potential candidate and the submission of a case for canonization, to ensure that only worthy candidates would be nominated.

However, the process was reformed during the 20th century. In 1983, Pope John Paul II set a new fiveyear waiting period for the Vatican office, now known as the Dicastery for the Causes of the Saints.

This waiting period before a cause may be submitted can be, and has been, waived at the discretion of the pope.

In 1999, Pope John Paul II waived it for the cause of Mother Teresa. The process began then, only two years after her death in 1997, and she was proclaimed St. Teresa of Calcutta by Pope Francis in 2016.

After the death of John Paul II himself in 2005, his successor, Pope Benedict XVI, again waived the waiting period for his case to proceed. Only nine years later, in 2014, Pope Francis proclaimed John Paul II a saint.

However, in the intervening years, questions were raised about what some considered to be a hasty or premature advancement of John Paul II’s cause.

Criticisms of the process

ELEVEN popes have served the Catholic Church since 1900. Three—Leo XIII, Benedict XV and Pius XI—have not been nominated. Pope Pius X, who died in 1914, was canonized 40 years later in 1954.

So far in the 21st century, several more popes have entered or completed the process.

Pius XII, who died in 1958, has been named “Venerable”—the second step of the canonization process—despite ongoing controversy over his actions during World War II.

But over the past 10 years, four popes—John XXIII, Paul VI, John Paul I and John Paul II—have been proclaimed saints, an unusual situation in modern Catholic history.

It can seem that canonizing popes has become routine in the 21st century. Some even suggest that this trend marks a new era of personal holiness in those elected to the papacy.

However, not everyone cheers this trend.

Critics cite the rapid canonization of Pope John Paul II as an example of potential problems. His lengthy reign and widespread popularity led to a special pressure on Pope Francis to move quickly on his cause.

Afterward, however, more evidence was uncovered raising questions about the pope’s handling of the clergy abuse crisis.

Politics within the church can also come into play.

For example, conservatives could push strongly to canonize a more traditionally minded pope, while progressives might support a candidate with a broader point of view.

This seems to be why two popes— John XXIII, who called the Second Vatican Council in 1962 to reform and renew the church, and John Paul II, who strove to curb some of the more progressive elements—were both canonized at the same ceremony.

The papal power to waive even the brief five-year waiting period makes these problems even more acute. Some have even suggested imposing a moratorium on papal canonizations, or at least lengthening the waiting period before a pope’s cause could be considered.

The Catholic Church teaches that saints are proclaimed so that others might be inspired by their lives and examples of “heroic virtue.”

But it takes time to thoroughly examine each cause individually, and hidden flaws may not be uncovered until much later after the candidate’s death.

This was true for St. John Paul II, and might be the case for Pope Benedict XVI. But no one is recognized a saint simply because he served as pope.

Joanne M. Pierce, College of the Holy Cross/The Conversations (CC) via AP

CBCP HEAD: ‘CANCEL CULTURE’ IS CONTRARY TO SYNODALITY

THE head of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines issued a warning against so-called “cancel culture” during his address to the CBCP three-day plenary assembly that started on January 28.

Speaking on the first day of the assembly, Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, CBCP president, said cancel culture has become a negative trend in society through the influence of social media.

“Nowadays, with a click of a finger, it is so easy to simply unfollow, unfriend, or cancel out the social media account of anyone who represents a contrary opinion,” David said.

“It is the exact opposite of synodality in the sense that it stops any further dialogue or conversation,” he said.

The CBCP head then reminded the bishops that being “supreme bridge-builder” is a role not only exclusive to the pope.

“We are ourselves called to participate in his role as a supreme bridge-builder, a facilitator of dialogue, reconciliation and communion in the local Churches entrusted to our care,” he added.

In January 2022, Pope Francis had made the same warning on cancel culture, which is “invading many circles and public institutions”.

“As a result, agendas are increasingly dictated by a mindset that rejects the natural foundations of humanity and the cultural roots that constitute the identity of many people,” he said in his annual address to the Vatican diplomatic corps.

Around 80 bishops gathered at the Pope Pius XII Catholic Center in Manila for their 125th plenary assembly.

The gathering marks their second faceto-face meeting since the Covid-19 pandemic erupted in March 2020.

Among those present in the meeting are Cardinal Jose Advincula of Manila and Cardinal Orlando Quevedo, the archbishop emeritus of Cotabato.

Archbishop Charles Brown, Apostolic Nuncio to the Philippines, also delivered his address to the assembly at the start of the day’s session. CBCP News

POPE IN CONGO: ‘HANDS OFF AFRICA!’

ROME—In his first speech in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pope Francis urged the international community to give the central African country its autonomy while not turning a blind eye to exploitation and violence.

“This country and this continent deserve to be respected and listened to; they deserve to find space and receive attention,” the pope said on January 31 in the garden of the Palais de la Nation in Kinshasa.

“Hands off the Democratic Republic of the Congo!” he continued, as spectators cheered and applauded. “Hands off Africa! Stop choking Africa: Africa is not a mine to be stripped or a terrain to be plundered.”

Pope Francis landed in Kinshasa, the capital city of the DRC, in the afternoon on January 31; the visit is the first leg of a sixday trip that will also include South Sudan.

The streets of the pope’s five-mile drive from the N’Dolo Airport to the presidential residence were lined with thousands of locals who cheered and waved flags.

Francis met privately with President Felix Tshisekedi before an audience with the country’s authorities, diplomats and representatives of civil society.

“May Africa be the protagonist of its own destiny!” the pope said. “May the world acknowledge the catastrophic things that were done over the centuries to the detriment of the local peoples, and not forget this country and this continent.”

The pope continued, “We cannot grow accustomed to the bloodshed that has marked this country for decades, causing millions of deaths that remain mostly unknown elsewhere.”

Pope Francis’ speech noted the DRC’s endurance of political exploitation, what he called “economic colonialism,” child labor, and violence.

“This country, so immense and full of life, this diaphragm of Africa, struck by violence like a blow to the stomach, has seemed for some time to be gasping for breath,” he said.

“As you, the Congolese people, fight to preserve your dignity and your territorial integrity against deplorable attempts to fragment the country, I come to you, in the name of Jesus, as a pilgrim of reconciliation and of peace,” the pope said.

“I have greatly desired to be here and now at last I have come to bring you the closeness, the affection, and the consolation of the entire Catholic Church,” he pointed out.

Violence in eastern DRC has created a severe humanitarian crisis with more than 5.5 million people displaced from their homes, the third-highest number of internally displaced people in the world.

Pope Francis was scheduled to meet with victims of violence from the eastern part of the country on February 1 in Kinshasa following a Mass that is expected to draw 2 million people. Roughly half of the 90 million people in the DRC are Catholic.

“I am here to embrace you and to remind you that you yourselves are of inestimable worth, that the Church and the pope have confidence in you, and that they believe in your future, the future that is in your hands, your hands,” Francis emphasized, “and for which you deserve to devote all your gifts of intelligence, wisdom, and industry.”

The pope added: “The heavenly Father wants us to accept one another as brothers and sisters of a single family and to work for a future together with others, and not against others.”

God, he said, “is always on the side of those who hunger and thirst for justice. One must never tire of promoting law and equity everywhere, combating impunity and the manipulation of laws and information.”

Hannah Brockhaus/Catholic News Agency via CBCP News

Asean Champions of Biodiversity

Media Category 2014