5 minute read

Ghana water polo grows looking for more diversity

BACK at the very beginning, right when the idea of water polo in Ghana started swimming into reality, Prince Asante got out a couple of balls and caps in front of a handful of curious kids.

He decided to try a scrimmage, but he had no nets. So they put a soccer bench on each side of the pool.

It was “enthusiastic confusion,” he said. And the caps—which have protective cups that go over a player’s ears—well, they were particularly amusing.

“Somebody said, ‘Oh, water brassiere, thank you very much,’ a water bra,” a chuckling Asante said.

That was one of the first meetings of the Awutu Winton Water Polo Club, a budding league in a tough part of the world for the Olympics’ oldest team sport—and a true passion project for the energetic Asante.

Growing up in Coronado, California, he was often the only Black face in the pool or his classes. He went in search of a water polo that looked more like him, and found it in the waters of his father’s homeland.

“This is like my baby, and it’s cute because, you know, it cries and it’s growing up, but it needs all of your attention, 24-7,” the 31-year-old Asante said.

“Whenever I talk about it, it’s great, because it’s something that I would have loved to see as a kid.”

In Ghana, dangerous rip tides off the country’s coast have caused countless drownings over the years. That’s led to trepidation about deep waters in a nation where low- and middleincome families already have limited access to swimming pools.

When Asante first started swimming in African communities, he saw looks of fear and panic on faces because “they all have stories of someone going out and not coming back,” he said.

The Awutu Winton club has seven teams representing three regions of Ghana. Players range in age from 7 to 25, and the league includes a group of about 20 women. It had 85 athletes and 10 coaches when it opened its new season last month in Ghana’s capital, Accra.

Asante said most of his Ghana players had some knowledge of swimming when they joined the program, but not in deep water, where the sport is played.

“Treading water and how to handle the water polo ball was very difficult when I started playing,” said Ishmael Adjei, 20. “But as time goes on, I could see I am improving personally.”

Adjei’s club is part of San Diegobased Black Star Polo, an organization founded by Asante that also works on creating aquatic opportunities for African and AfricanAmerican communities in the United States.

“When I started playing, [my family] thought it was just a waste of time,” Adjei said, “because you had to help them do the family chores and you would take a timeout to go and have training...but as time goes on, they are getting interested.”

Any significant growth in Africa would be a welcome development for a sport that has wrestled with a lack of diversity for decades, much like aquatics in general. Even in the places where water polo is most popular—such as California, and parts of southern Europe— there are very few players of color.

Egypt and South Africa are the only African countries that have played men’s water polo at the Olympics. South Africa became the first women’s team from the continent to make it to the Games when it finished 10th in Tokyo in 2021. World Aquatics said it doesn’t have player participation figures broken down by ethnicity.

“I think it’s vital for the growth of our sport to break out of the normalcy that it’s been the last century, of traditional water polo nations,” said former US player Genai Kerr, who serves on the board of the Alliance for Diversity in Water Polo.

The second of three brothers, Asante got into swimming and water polo after his family became good friends with the family of fivetime US Olympian Jesse Smith. Asante played college water polo at

He finished with 48 points—Cleveland closed out the series with a Game 6 win and sent James to the NBA Finals for the first time.

“We threw everything we had at him,” said Detroit guard Chauncey Billups, now the Portland Trail Blazers coach. “We just couldn’t stop him.”

THE PROMISE

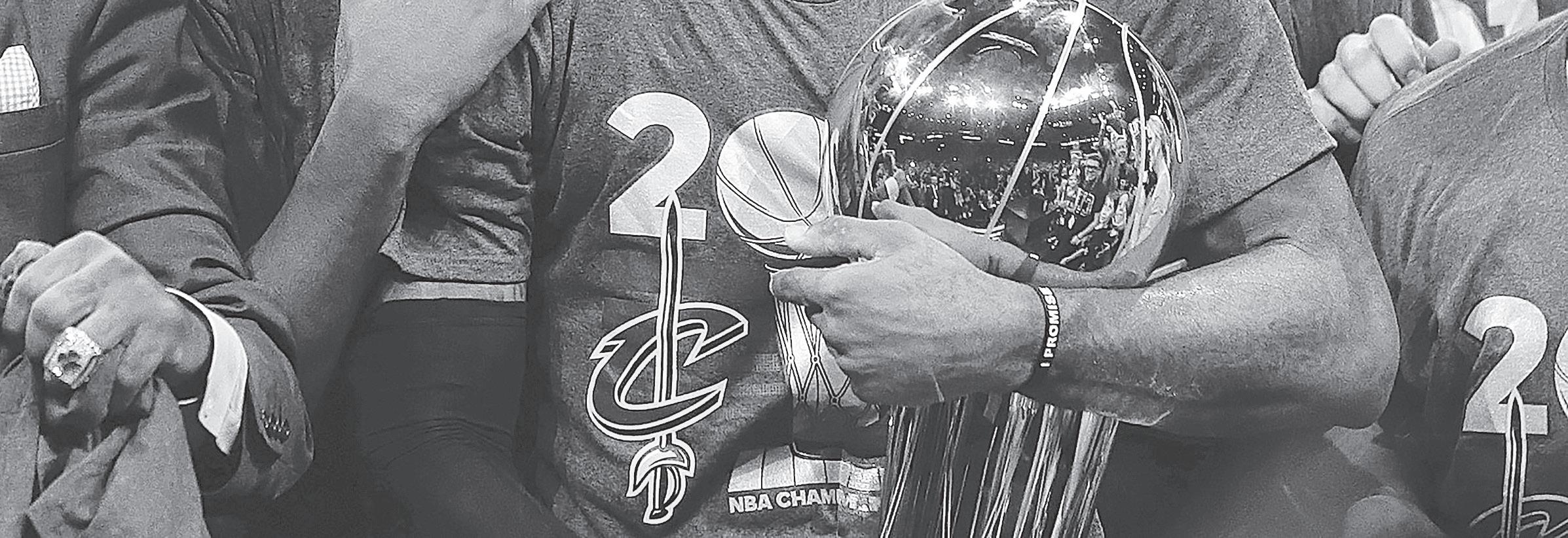

LEBRON JAMES had promised Cleveland a championship. And then he left in 2010 for Miami, a move that left Cavs fans jilted for years—especially when he won two titles there. But when he returned in 2014, all was forgiven. Two years later—June 19, 2016—he finally delivered what Cleveland had waited generations for.

He had 27 points, 11 rebounds and 11 assists, plus a chase-down block of Golden State’s Andre Iguodala to keep the game tied with just under two minutes to go. The Cavs went on the Warriors’ floor and dethroned the champions, winning 93-89 and capping a comeback from a 3-1 series deficit.

It was the first major championship for the city of Cleveland since the Browns in 1964.

THE FOURTH LEBRON JAMES’S fourth title came with almost no fans there. A handful of team employees and a very select group of invitees were the only ones inside the bubble at Walt Disney World in Lake Buena Vista, Florida when the Los Angeles Lakers beat the Miami Heat in the 2020 NBA Finals.

It capped a season delayed by the pandemic and one where the Lakers had to grieve the death of Kobe Bryant earlier that year.

James once again had a triple-double in the title-clincher, this time 28 points, 14 rebounds and 10 assists. The Lakers won 106-93, taking the series 4-2.

“Our organization wants their respect. Laker Nation wants their respect,” James said that night. “And I want my damn respect, too.”

California Lutheran University and got his degree in psychology. He competed professionally in Brazil and trained in Europe.

He often felt he stood out as a Black man.

“Just being used to everybody being able to see me and standing out,” he said, “and I’m the one everybody notices first, on every class, every team.”

It was different in Ghana, the birthplace of his father, Dr. Kofi Sefa-Boakye. Asante’s mother, Elizabeth, is from Los Angeles, and she met Kofi when they were students at the University of Southern California.

Asante started going to Ghana with his father after he graduated from high school. He often brought balls and caps on trips to visit family. In 2018, he reached out to the country’s swimming federation, and it held an event at Awutu Winton Senior High School—one of the only schools in the country with a pool—where it made a donation and promoted the program.

“What he’s doing is awesome, because it’s so difficult to start something from scratch,” Smith said.

A relatively small geographic footprint can put a sport at risk of losing its place at the Olympics, according to Victoria Jackson, a sports historian and clinical assistant professor of history at Arizona State University. But, Jackson said, decisions about what sports to include are hard to predict and reflect politics, relationships and subjectivity.

Jackson said an all-Black water polo team at the Olympics could have a profound effect on the sport.

“I mean, it’s that quote, right? ‘You can’t be what you can’t see,’” she said. “It’s immediately horizon expanding.” AP