Leiden 1959 | Gaza 2023 - 2025

for my dear friends in dire straits in Gaza the journalist Rita Baroud the artist Maisara Baroud who were forced to 'move' fourteen times without taking anything but themselves with them

content the art work deleted identity

DISTANT SUFFERING | the project acknowledgment page 04 page 10 page 14 paga 17

Sometimes, while writing, I feel like I'm trying to cross an infinite ocean. The world is far away, busy with its regular daily routines, while I am writing from a city facing genocide.

Rita Baroud | December 21, 2024 in NRC Handelsblad

DISTANT SUFFERING LIV i.d.

artwork

of a burned future the

12 black and white photoprints

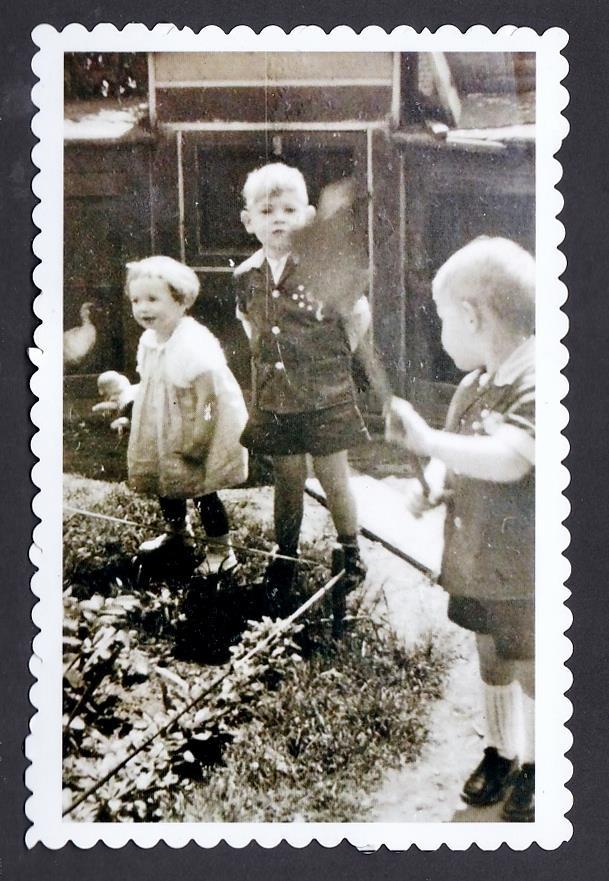

9 x14 cm | 300 grs Plano from our family archive

folding mattress BASIC F15 | JYSK plexiglas cube 30 x 30 x 30 cm

wooden console

30 x 30 x 20 cm

painted matte white

Photo

Leiden, 1959 | Wil Freeke Pieter de la Courtstraat 67

grandparents back garden

Left to right: our niece Annemieke Freeke, me and my brother Marten

deleted identity

In the modern, civilized West, we spend a lot of time and attention on our identity. InwhichIshouldimmediatelyrestorethat singular to plural: Facebooks' algorithm now distinguishes more than 50 different identities of its users. Some 20 types of identity are recognized in international law and protected by human rights. One experiences identity as the result of origins, gender, sexual orientation, as well as experiences, achievements and social ties, among others. An identity may be innate (such as by skin color), or created later in life (as in survivors of serious illness or trauma), or chosen (such as a political viewpoint). But in many cases, the line between what is self-chosen and what is given is quite fluid.

Ones own identity is always intertwined with your cultural, economic and social position. Again, a position that can be fluid. Where culture is not just a collection of visable elements such as art, music or cuisine, but is completed by a complex system of norms, values, beliefs and practices that surround us from birth.

When your living environment, your society with all its identitarian signs – architecture, libraries, universities, religious buildings, governmental buildings, historical heritage, etc. is destroyed and/or rendered unusable, the physical frame of reference of your past, your present and thus your future simultaneously disappears. The past, not only as memory or idea, but as material. The vibrant Gazan cuk

The vibrant Gazan culture with its long history is in immediate danger of being erased. Moreover, many artists have been killed: writers, musicians, poets, calligraphers, singers and dancers photographers, painters, theater makers, etc. Or they are no longer able to work due to hardship and lack of resources. We become dependent on peoples’ testimonies about life in Gaza, as it was, as it is and as it may never be again. We need witnesses who paint a picture of daily life in streets, squares and markets. Who tell what the landscape looked like, what trees were there, where the city was and where the countryside was. Who give an insight into people's moods, their dreams and questions, their plans and and questions, their plans and disappointments. Which tell of meals, grandmothers’coffee, feasts, music, song and dance, and which explain how Palestinians relate to religion, family, politics and culture. We need stories through which we can understand life in Gaza from the inside and empathize with the big and small events, the dilemmas, conflicts and contradictions and the struggle of every Gazan to live in impossible circumstances.

The most tragic thing - because irreplacable - I tried to put off, but comes ruthlessly and inevitably: more than 45,000 ordinary people have been erased and silenced by the colonizing apartheid state of Israel. What does it mean to erase a people - a nation, a culture, an identity? This is beginGaza.

nation, a culture, an identity? This is beginning to become quietly clear in Gaza and eventually leads to the horrifying observation of Rita Baroud, a journalist friend in Gaza: “My apartment in al-Jalaa, in a fivestory building, was a witness of the small, simple details of our daily life. I lived there with my uncle and grandmother under a roof that gave us security and warmth. On the third day of the war, this safe haven, without any warning, turned into a mess.

From one one moment to the next, everything was gone, everything buried – the walls that embraced our dreams, the corners that held our laughter, even the smell of the coffee my grandmother made in the morning.”

“I write. I write about widows lining up for food at a food distribution point, the last resort for families fighting against hun-

resort for families fighting against hunger. I write about children playing among the rubble, still trying to have a little fun in this tragedy.

Today, everyone is talking about winter. There is fear in the air - fear of what the cold will bring with it . . .”

I definitely don't want to put myself on the same page as Rita. After all: I’m writing in a warm, safe house; in short, in paradise conditions.

I am 72 years old at the time made this piece of art. In 1959 my uncle Wil Freeke took the picture I use in this piece. It shows his daughter - my niece –Annemieke, my brother Marten and me in the backyard of my paternal grandfather at the Pieter de la Courstraat 67 in Leiden.

A verifiable part of my indendity.

A verifiable part of my indendity. Because we still have the photo, because my grandfather's house is beautifully updated into this era, because the small neighbouring square and park with the modest pond adorned with the merry figurine of a dolphin and a mermaid still exsists. It’s a place I visit always whenever I am in my place of birth – Leiden. Materialised past, present and humble future.

Today Annemieke, Marten and I are still alive and share these memories each in our own way. Shared with their children, my nieces and nephews. From which this piece of art is another modest kind of witness.

About which, in terms of political, concrete effect, I am extremely uncertain. question

To paraphrase Rita Baroud’s principal question: ‘Is art enough? Maybe not. But it is all I have.' Which makes us both very proud and simultaneously very sad brother&sister in arms.

Middelburg, December 29, 2024

Martha Jager, curator Vleeshal in MiddelburgNL about the oeuvre (2023) after a studio visit: The dedication to art as a relational verb is central to Overvliet's work. On the one hand, the balance between poetry and criticism is special, in that the work never becomes bitter or pedantic, while at the same time the dialogue with the viewer is actively maintained. It is a tender form of activism that moves and urges action and also continuously questions the role of art.

Since 2013, by means of the ongoing art-series distant suffering, the Dutch artist Hans Overvliet (Leiden, 1952) investigates the role of the media in their representation of (military) violence. This, in the context of themes as perception, memory and identity formation.

Overvliet uses a various range of media, symbols and codes, bringing together dichotomies like beauty and violence, refinement and brutality, the sublime and the vulgar.

Aspects of power, politics, exclusion, censorship and the connection between artist, artwork and viewer infiltrate his multifaceted conceptual oeuvre.

As a reporter, Overvliet was an eyewitness to the events in the Middle East during the 1980s. Of course these experiences resonate in distant suffering.

Elements of distant suffering were exhibited in the Netherlands, Belgium, Pakistan, England, France, Italy, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Albania, Germany, Lebanon, the U.S.A., Brasil, Greece, Argentina and Sweden. In 2023, his whole body of paper collages ( 1999 – 2012 ) joined Geert Verbeke’s renowned collection of collages and assemblages. In 2024 - 2025 the whole oeuvre of was exhibited in the museum part of the Verbeke Foundation. All the work will then be included in the permanent collection.

Next to his art-work Hans is, together with his wife Willy van Houtum, the founder and every day guardian of ruimteCAESUUR, the 30-year old space for contemporary art in Middelburg in the province of Zeeland.

Acknowledgment

Marten Overvliet, who found the photo by Wil Freeke and sent it to me; Loek en Perry Overvliet took the photo of the photo of Wil Freeke in Café l'Espérance, Kaiserstraat 1, Leiden.

Willy van Houtum who helped guard and preserve the clarity of the work. Wil Freeke 2 2/01/192220/08/1994