DANIEL BOYD BITTER SWEET

EXHIBITION DATES 24 June - 10 September 2017

EXHIBITION DATES 24 June - 10 September 2017

Daniel Boyd is recognised as one of Australia’s most innovative and exciting contemporary artists. For Boyd, his exhibition Bitter Sweet at the Cairns Art Gallery has a particular significance, as it is his first solo exhibition in Cairns, Far North Queensland, where he was born and grew up.

Presented in partnership with the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, Bitter Sweet brings together major works that draw on the hidden history of slavery in Far North Queensland that resulted in 60,000 South Sea Islander people being taken to work in sugarcane plantations from the mid1800s and early 1900s.

Boyd’s work questions the romantic notions that surround the birth of Australia and the ways in which our history continues to be dominated by Eurocentric views. For him it is very important that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to create dialogues from their own perspective, to challenge the dominant history that has been created.

Bitter Sweet explores narratives of the Pacific Islands as a ‘paradise’, and the life of Pacific Islanders in relation to slavery and the sugarcane industry, and their effect on descendants’ lives in Far North Queensland, including on the artist’s own ancestors.

Works selected for the exhibition, and reproduced in this publication, are informed by the collective memory and journeys of the

artist’s family of Pentecost Island (Vanuatu), and other South Sea Islander people to Far North Queensland.

I would like to acknowledge Senior Curator, Julietta Park, for curating the exhibition which makes a significant contribution to presenting alternative cultural narratives relating to Far North Queensland.

We are delighted that respected art historian and curator, Djon Mundine OAM, has provided an insightful essay that offers divergent interpretations of the artist’s work and his fascination with ‘the space between’ and ‘the folding of time’.

The exhibition would not have been made possible without the generosity of public and private lenders, including the artist and his family, the National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South wales, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and Station Gallery, Melbourne

Finally, I would like to thank Daniel Boyd for collaborating with us on this important project, and congratulate him on a remarkable body of work that has particular relevance to Cairns and our particular place in the world’s tropic zone.

Andrea May Churcher Director Cairns Art Gallery

BITTER SWEET

DANIEL BOYD’S RETURN TO NORTH TROPICAL QUEENSLAND

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe…

All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.

Replicant Roy Batty, Blade Runner, 1982

From our first meeting, I was impressed with Daniel Boyd. As it unfolds his art has exhibited the poetic, the political, the subversive, the rhythmic, the transformative, the imaginative, the musical, the spatial, the mythic, the energetic, and the luminous.

In 1982, when Daniel Boyd was born in Cairns, two films were released that, I think, obliquely speak to his history, influences, and creative path. Werner Herzog’s manic and surreal Fitzcarraldo told of the mad, perverted obsession of western colonial hegemony to bring civilisation to the savage ‘other’, through building an opera house in the Amazon jungle and teaching a dominant western view of history. The other film, Ridley Scott’s dark Blade Runner , talks of identity, reality, personal consciousness, and a form of cosmology. In Blade Runner , replicants are artificially created short-lived forms of human life and are used as slaves in off-Earth colonies, but banned from living on Earth among humans. The central questions raised

in the film are - who is a human and who is a ‘replicant’; who is civilised and who is a ‘savage’; what is real and what is a dream?

Daniel Boyd was the youngest of three children. His painting career would go through two major movements after he chose painting as his form of expression. Around the time of graduating from the Canberra School of Art he created a series of history paintings, re-writing a set of classic colonial portraits and history paintings of significant events that were turning points of criminality in the colonising of Australia. Daniel then broadened this truthful, historical view to include the curious African slavery case of Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, on the African west coast.

Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, ‘Province of Freedom’. The premise for its establishment: a location for emancipated slaves following the abolition of slavery. The process of British liberation resulted in the relocation of Africans to an idealised and constructed freedom, often far from the life before. One that is imposed rather than chosen. Imposition is a common theme across the works in Freetown (exhibition). They are about the idea of freedom. A freedom that is complex, constructed and idealist. A lion painting shows the return of the animal to its natural environment after captivity. The titles are love songs to illustrate a romantic idea of freedom.

Using images of lions, symbols of colonial rule and European royalty, he talks through the return of freed African American slaves to a place set aside for them. The exuberance of their freedom is expressed in the lions’ lively, powerful personas and the movement of the zebra herd.

It appears Daniel then discovered particle theory – a theory that all matter in the universe is made up of small separated particles that are vibrating at varying speeds and spacing. There was also the existence of ‘dark matter’ in the universe that doesn’t reflect light but the particles of which are four times the number of the reflecting stars. There is, of course, the historical-social metaphor extension of ‘dark matter’. Daniel delved into his Pacific Islander background, history, and influence in western art history. It moved him to think of and express a cosmology; of what is the unknown and what do we know.

At the opening of Queensland artist Tracey Moffatt’s 2017 Venice Biennale exhibition My Horizon, award winning filmmaker George Miller,

in congratulating Moffatt, said something to the effect that art is just not an image that it is allegorical, that is accessible. It is ambiguous, just out of reach. And the measure of art is possibly how long it follows you out into the world afterwards.

Bitterness is an emotional state as well as a taste. While pungent, the qualities of salt (and sugar) are pervasive through contemporary life, and their addictive nature has left a bitter after-affect for Indigenous communities. The term ‘bitter sweet’ describes the taste of a food or drink, or a human social interaction that is pleasurable, but tinged with an aftertaste of bitterness, pain, or sadness that lingers, a form of saudade - a longing for a person or place or pleasurable experience.

Well, we can’t seem to cure them of the idea that our everyday life is only an illusion, behind which lies the reality of dreams.

Old missionary, Fitzcarraldo , 1982

This year (2017) Daniel explained to me the idea of ‘folding space and time’ - to think of two sites in time and place, and to think of them

as two separate spots on a page, and that the quickest way to bring them together is to just fold the page. Daniel certainly folds space and time in his art images and in his very social and historical existence. Daniel is of mixed race descent - Pentecost Islander (now part of Vanuatu), and Kudjila/Gangalu Aboriginal peoples, from Clermont South to the Dawson River region of mid Queensland. Daniel was born in Cairns, still an extremely cosmopolitan multicultural city and region. In the late 1800s and until 1901 ‘white’ Europeans were out numbered by Aboriginals, Islanders, Japanese and Chinese.1

Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it? That’s what it is to be a slave…

Replicant Roy Batty, BladeRunner,1982 On both sides of Daniel’s heritage are bitter sweet stories of dispossession, disempowerment, and forms of slavery. Two stories of hidden histories of galling colonial crimes. Between 1863 and 1904 some 62,000 South Sea Islanders were recruited, ‘black birded’ (kidnapped or deceived into leaving their homes), coerced or enslaved, and brought

to Australia to toil in the tropics of north Queensland, from the Tweed River up, clearing land and developing sugar plantations. Other plantations grew bananas or pineapples. [See Untitled (LP) p.8 & Untitled (SL) pp.21-22]

As sugar in the Caribbean, and later in Queensland, brought science and agriculture together in the plantation system, it allowed a ‘new aristocracy’ to grow rich; even some of those who had been brought in grew rich in this environment. Some eight hundred ships were engaged in this practice. [See Untitled(LSSC) pp.17-18] There were men, women and children. [See Untitled(BNH) pp.25-26] They came mainly from Vanuatu (as did Daniel’s antecedents), but also from New Caledonia, Fiji, Gilbert Islands, New Ireland, and Milne Bay Provinces of Papua New Guinea. [See Untitled(NHC4) p.12 & Untitled(SIC) p.9]

They were called Kanaks, after the Hawaiian name for a human being that is now seen as a derogatory term. [See Untitled (HL) p.10] They were off-loaded in Brisbane, Maryborough, Bundaberg, Rockhampton, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville, Innisfail and Cairns. Daniel’s family worked in many places – he thinks his greatgreat-grandfather, Samuel Pentecost, was buried at Maryborough.

Two Acts, ThePolynesianLabourersAct 1886, and the Pacific Island Labourers Act

1880 (Queensland), were enacted to curb kidnapping and enslavement, but the latter was also introduced to monitor and control numbers and where they could work, live, and interact with Australian society. Exploitation was still widespread - many Kanaks were paid only in rations. Eventually, after 1901, it was the White Australia policy of the new Australian nation, rather than humanitarian feelings, that led to calls for their repatriation. By the 1890s, it could be said that most of the hard work of clearing the land had been done and ‘white’ labourers now were employed more as labourers on the plantations. However, many Kanaks had married local Aboriginal people and for this and other reasons wanted to stay. In Blade Runner there are one hundred and seventy-four questions asked in the interrogation of a replicant, to determine its identity - human or not. In 1898 the selfgoverning colony of Queensland passed The AboriginalsProtectionandRestrictionofthe SaleofOpiumAct 1897. There were thirtythree clauses in the legislation that defined who was an Aboriginal. Defined where they could live. Defined who they could marry. Defined where they could work and what they were paid.

My great-grandfather Harry Mossman (whose father came from Pentecost Island), was taken from Mossman to Yarabah, where he was photographed by ethnologist Norman Tindale (1900-1993).

Daniel Boyd 2017 commenting on Untitled(HM) (see p.24)

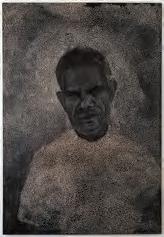

Boyd’s immediate Aboriginal predecessors lived at the Anglican Yarrabah ‘mission’ just outside Cairns. Yarrabah was set up in 1983 by Ernest Gribble (1868-1957). Much is now made of ‘traditional’ Aboriginal arranged marriages, but the mission church, in an effort to breakup the power of elders, arranged western style marriages in the Christian church [See Untitled(YC) pp.19-20]. The coloured, black and white image of Untitled(GB) (see p.23) is of Daniel’s mother’s mother, Gertrude Brown (dec.), taken in Yarrabah when she was in a bridal party. The original little, blue, version of this portrait was bought by Malcolm and Lucy Turnbull.

In 1957, the Yarrabah residents staged a strike to protest against poor working conditions, inadequate food, health problems and harsh administration. The church expelled the ringleaders. Many others, including Boyd’s relatives, left voluntarily to escape living under ‘the Act’ (TheAborigines’andTorres Strait Islanders’ Affairs Act 1965-1972, through which government powers could control every aspect of people’s lives), never to return. Boyd’s relatives set up Bessie Point community, now Giangurra, later affectionately called ‘beach dogs’. While at school Boyd had made small tourist paintings of the reef to sell locally. He said he had several uncles who were talented painters who mentored him.

I always had a passion for art and when I had the chance to leave Cairns I jumped at it! Cairns is a beautiful place but not so stimulating, also I knew I wasn’t going to play in the League. I was too short for my position.

Daniel Boyd, interview with Vissukamma Ratsaphong,The Blackmail , May 2017

I think the Greeks said you can achieve immortality through heroic actions in battle (or sport), through athletic records or creations in the arts, and the intellect. From an early age Daniel would draw copies of classic western masters, and these caught the eye of teachers and family who encouraged him to go on and attend art school. At the same time, during his teenage years, he enjoyed and excelled at rugby league and played semi-professional basketball with the Cairns Marlins. In 2001 he decided to attend the Canberra School of Art, where he made use of all their facilities and studios, moving to painting and to seriously studying Aboriginal and Islander art history - the things he hadn’t been taught at school. Implants. Those aren’t your memories, they’re somebody else’s…

Deckard, BladeRunner, 1982

I was always taught at school the fiction that Captain Cook ‘discovered’ Australia. On my first work trip with a colleague to Cairns in the 1970s, without any sense of irony, the Aboriginal art company I worked for booked us into the Captain Cook motel - noted for its tall, ten meter-high, cement statue of the said captain. Viewing the map, the history of this region in a way clings to the memory of Cook. Cook named the future site Trinity Bay, being forced to land there on Trinity Day, the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Christian calendar and the celebration of the Holy Trinity of Father,

Son, and Holy Ghost. In fact Cook would only land intentionally two times (at Botany Bay and Possession Island) on his ‘discovery’ of the nearly 36,000 km long east coastline, yet still he claimed the whole of Australia for the King of England while on the uninhabited Possession Island. On the way he missed the openings to Sydney Harbour, the Hawkesbury River, and the Brisbane River.

The settler makes history and is conscious of making it. And because he constantly refers to the history of his mother-country, he indicates that he himself is the extension of that mother-country. Thus, the history that he writes is not the history of the country that he plunders… Franz Fanon, TheWretchedoftheEarth, 1961 When Daniel moved to painting in Canberra, he would also focus on Cook, but strived to correct the official so-called heroic record of these voyages and British colonial histories with CaptainNoBeard (2005), GovernorNoBeard, KingNoBeard , and Sir No Beard , presenting the regal and heroic paintings of the players of the British empire and the ‘discovery’ of Australia, with pirate eye patches and parrots on their shoulders, as untrustworthy criminal characters. The No Beard paintings refer to Aboriginal people’s puzzlement about the gender of the colonisers, since they had no beards and their genitals were hidden by clothing.

Daniel’s painting We Call Them Pirates Out Here (2006), further explored this theme by re-interpreting E. Phillips Fox’s painting The LandingofCaptainCookatBotanyBay (1902) that was painted at the time of Federation. In this painting, Boyd in essence points out how one culture’s hero is another culture’s criminal. In 2005 Daniel would have his first sell-out solo exhibition, before even finishing his arts

degree, with a series of paintings that play on historical portraits of colonial figures, Cook, Philip, and King George. The National Gallery of Australia acquired work from this exhibition, making Daniel, at the age of twenty-three, most probably the youngest artist to have a work acquired for their collection. The work went on to be included in the inaugural Cultural Warriors: NationalIndigenousArtTriennial at the National Gallery of Australia in 2007, and Daniel would state:

Questioning the romantic notions that surround the birth of Australia is primarily what influenced me to create this body of work. With our history being dominated by Eurocentric views it’s very important that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to create dialogue from their own perspective to challenge the subjective history that has been created. For some people, the happiest time of their lives is when they are in their mother’s womb - floating, playing and imaging in the warm amniotic fluid, fed at will, and observing/sensing an unstructured, wonder, light and sound show through their mother’s skin. I have often thought of the Pacific as a womb-like body of water

that people play in and sailed across, using star frames to read the stars to guide them. [See Untitled (MINCC) p.15] We should also remember that James Cook originally came to the Pacific to view the transit of Venus from Tahiti. I think it is no accident that surfing originated and existed in the Pacific.

Pentecost Island (also referred to as Raga or Araga) is one of eighty-three islands making up the nation of Vanuatu. It was named by Louis Antoine de Bougainville on Pentecost Sunday, 1768. [See Untitled (P13) pp.5-6] Pentecost Island, where Daniel’s great-great-grandfather came from, is the place where bungy jumping or land diving came from. It is a moist, plush, green land with torrents of running water, as it appears in Untitled(PIW)(seep.9). The age-old ritual called Gol (nangol in Bislama language), happens between April and June every year, where men from the southern part of the island, in a display of manhood, jump from tall towers at least thirty metres high, with vines tied to their ankles. Walter Lini, who led the Vanuatu independence movement in 1980, also came from this island.

All he’d wanted were the same answers the rest of us want. Where did I come from? Where am I going? How long have I got? Decker, BladeRunner, 1982

It could be said that one of the triggers or forerunners and beginnings of the Age of Enlightenment was Galileo’s (1564-1642) challenge to the ‘flat earth’ notion, and the notion that the sun, not the earth, was the centre of the universe. Art is an enquiry into the creative process, an interplay with the intellect and intuition. Art is felt with the whole human being, not just in the sensesemotionally, socially, and intellectually. In 2015, a non-Aboriginal moving image artist, on seeing Boyd’s landscape moving image work Middle , in the exhibition Bungaree’sFarm , exclaimed “… ofcourse,that’sit,Aboriginaldotpaintingisa reflectionofthestarsinthenightsky!” After the Age of Enlightenment, when everything could be named, quantified, and measured, in a European eye, came the Age of Colonialism and the Age of Slavery, both along race lines. A number of Papal enquiries were held in this period to discover whether these ‘dark’ people from the new lands were really, actually, human, did they have souls or not?

Human sight has evolved in the form of binocular vision that we have today. Stenopaeic lens glasses, or pinhole glasses, are eyeglasses for people with myopia. They consist of opaque lenses with many tiny perforations that each admit only a narrow beam of light, reducing the circle of confusion on the retina and assisting it to focus on the image and lengthen the depth of field. Daniel Boyd works with this focus metaphor in both his walls of light and black space, in viewing the actual world and the historic images that bombard us in our everyday lives. I was once told by an art historian how a particular artist suffered from a synesthesia condition response – a neurological phenomenon defined as a ‘union of the senses’. In Ang Lee’s 2012 visual and philosophical masterpiece, Life of Pi (based on the novel Life of Pi by Yann Martel, 2001), there is a scene where a glass-still ocean mirrors the clear night sky to create the beautiful image of the lifeboat floating in a three hundred and sixty degree, dense, amniotic fluid of bright and dark particles. A reviewer described it as an image of deep sense of place and events. While people may come to north Queensland and Cairns for the Casino, I think more come to play in the warm womb of the Pacific, or to lose themselves in the immense open night skies.

When the British came to what is now Sydney, they saw light dance across the physical landscape, but failed to see the dark matter – the cultural, social, and spiritual Aboriginal space. To see the truth one must focus on and be conscious of things beyond the obvious. Look at the dark and not the stars, not the light. Scientists now tell us of the ‘dark matter’ of the universe and that there is in fact three or four times more ‘dark matter’

than light in this limitless space. The space could be the miniature of the inner atomic world, or the infinite manifold stars of the universe. Physicists now talk of an energy field, the Higgs field that joins everything in the universe. Daniel Boyd’s work references landscape, not just the physical but also the social, cultural, and experiential landscape, surrounding art objects.

Images of people are more important socially to the family and not as an art world market commodity. I took twelve paintings up to Cairns to give to my mother and family.

Daniel Boyd 2017 commenting on Untitled(GB) (see p.23)

Possibly we live in a time where we know the minute cost of everything, but the value of nothing. Exhibitions should be about context, not merely economics. A practice of Ngakku Aboriginal artist Robert Campbell Jnr (19441993) from Kempsey, when his career took off, was that, for every painting created for his commercial exhibitions, he would also paint one for his family. Many artists in history have worked this way. It’s a special moment in an artist’s life when they come to this realisation. For this, the return of the native for his first solo exhibition in Cairns, Daniel said he wanted to make special gifts to his relatives who were most important to him:

[As] previous works were dealing with icons of colonisation, having a child has made me want to be more engaged with family history, although it hasn’t altered my output, there is a shifting to something closer.

DanielBoyd:ADarkerShadeofDark , exhibition essay by Ian McLean, Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, University of South Australia, 2015.

Daniel Boyd - A poem for my daughters

Balbay and Yamani for our ancestors

Whoosh goes the cane cutters inside, seldom outside the abyss deliverance comes in waves – balbay - flickering while stickiness clings to the walls she gives life to rhizomatic silhouettes, blackbirds seek shelter here while infinite ripples in a sacred blue pool tremble for my daughters and their daughters.

Barriers create the creator raindrops collectively give way to torrents shifting ancients through billions of moons yamani dark like matter bright like rainbow coloured truths beautiful harmonious truths.

I first met Daniel Boyd when he was a student at the Canberra School of Art and I ran a History of Aboriginal Art course that he wasn’t enrolled in. He was well on the way to his degree by then and was carrying out his own intensive research into the ‘official colonial image’. We had long conversations about art, life, and football. Later, when we both lived in Sydney, he came to teach in Goulburn Correctional Centre as part of an art program I was running in 2011 – PeopleWeKnow–PlacesWe’veBeen . His quiet but confident manner really impressed his students - they felt close to him and told me so. Silence worries many people, but in this ‘male space’, his inmate students took his silence as a mark of maturity, knowledge, masculinity, and as humility – not stupidity or arrogance. They empathised with him.

I then invited Daniel into the BungareetheFirstAustralian workshop project at Mosman Art Gallery for which he created the dark sky-moving image piece Middle (2013). This was later part of the second phase of the project Bungaree’sFarm , a projection performance exhibition that won the Australian Museum and Galleries Association Exhibition of the Year Award (2015).

In 2014 Daniel installed a large stenoptic window screen at Tarrawarra Museum of Art at Healesville for the multi-art form, multi artist exhibition, WhisperinmyMask. He also contributed three paintings inspired by historical images of the nearby Coranderrk Aboriginal mission. In 2016 Daniel repeated the stunning window screen on a smaller scale as part of the Sixth Sense exhibition, focusing on forms of sensory reception with a similar number of artists at the National Art School in Sydney. As the school was, in a former life a gaol, and site of the execution of the Aboriginal bush ranger-murderer Jimmy Governor, Daniel also contributed two small ‘mug shot’ portraits of Jimmy for the exhibition. Daniel continually impresses me with his knowledge of art history and his creative ideas.

Djon Mundine OAM Independent curator, writer, activist, and sometimes artist June 2017

1 NorthofCapricorn:theuntoldstoryofAustralia’snorth , Henry Reynolds, Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, 2004.

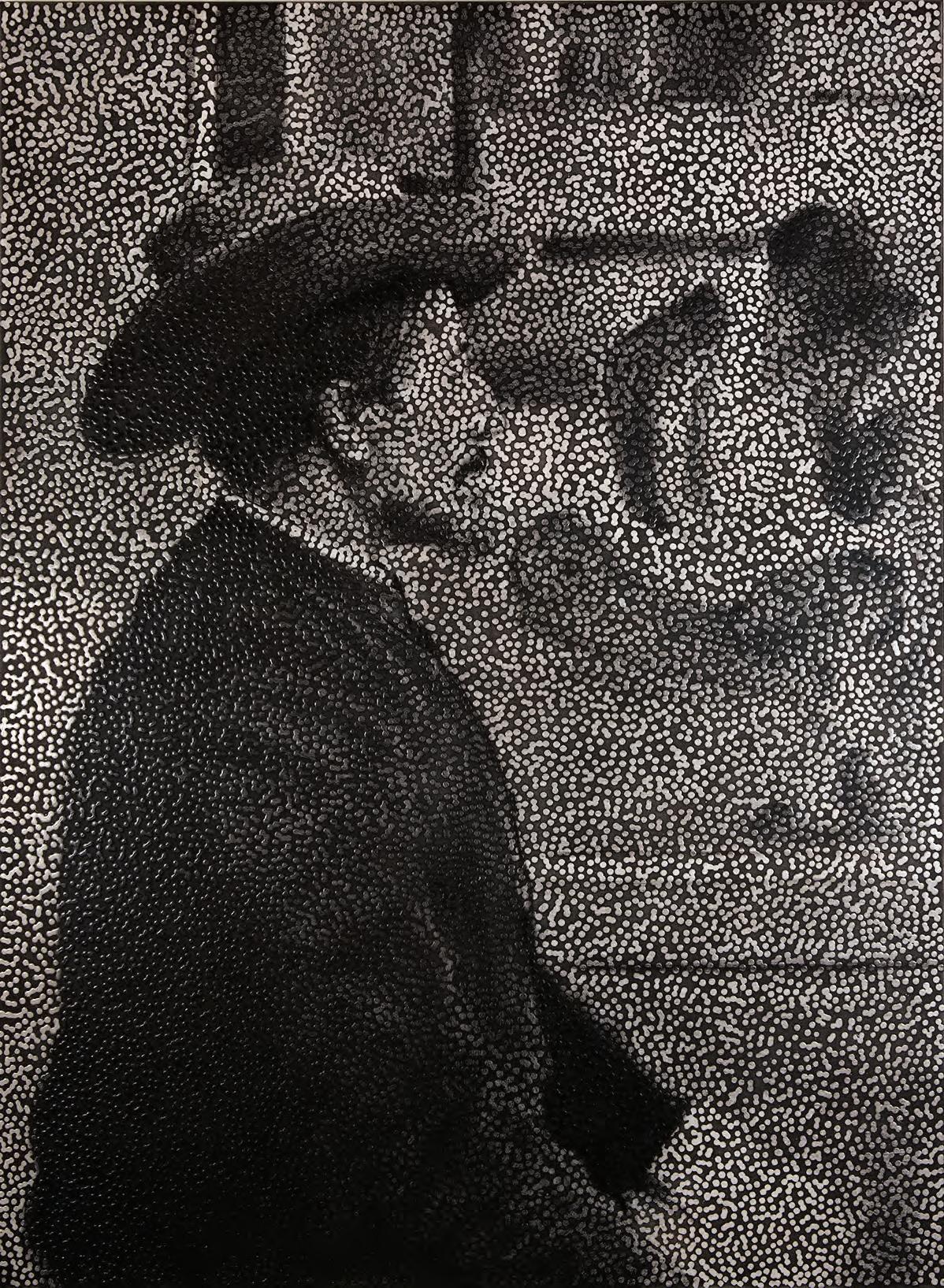

Cover, p. 1-4

History is Made at Night, 2013

two-channel video installation, sound, 16:9 mins.

Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley 9 Gallery, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurery

p.9

Untitled (SIC) , 2014 oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas

81.5 x 71.0 cm

Collection of Michael Schwartz and David Clouston, Melbourne

photo: Courtesy the artist and STATION, Melbourne

Untitled (V) , 2013 oil and archival glue on linen

87.0 × 92.0 cm

Collection of Leslie Boyd

Jessica Maurer

p. 5-6

Untitled (P13) , 2013 oil and archival glue on linen

214.0 × 300.0 cm

Collection of Gwen and Stewart Wallis AO, Bowral photo: Jessica Maurer

p.10

Untitled (HL) , 2014 oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas

81.5 x 71.0 cm

Private collection, Melbourne photo: Courtesy the artist and STATION, Melbourne

Untitled (V2) , 2014 oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas

183.0 x 183.0 cm

Private Collection, Melbourne photo: Jessica Maurer

p. 7

Untitled (PIW) 2014 oil, pastel, archival glue on canvas

315.0 x 224.0 cm

Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Bulgari Art Award 2014 photo: Jessica Maurer

p.11

Untitled (GSP) , 2013 oil, charcoal and archival glue on linen 168 × 122 cm

Collection of David Cowling, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurer

p.15

Untitled (MINCC) , 2014 oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas

181.0 x 131.0 cm

Private collection, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurer

p. 8

Untitled (LP) , 2013 oil and archival glue on canvas board and wood

30.5 × 25.5 cm

Private collection, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurer

p.12

Untitled (NHC4) , 2014 oil, charcoal and archival glue on linen

167.0 x 137.0 cm

Collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne photo: Jessica Maurer

p.17-18

Untitled (LSSC) , 2017 oil, archival glue, watercolour and archival print on paper

38.5.0 x 61.0 cm

Collection of the artist, Sydney photo: Courtesy the artist

p.19-20

Untitled (YC) , 2013 oil and archival glue on polyester

196.0 × 300.0 cm

Collection of Cairns Art Gallery, Cairns Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Daniel Boyd for the people of Yarrabah, 2015 photo: Jessica Maurer

p.23

Untitled (GB) , 2013 oil and archival glue on linen

183.0 x 137.5 cm

Collection of Karel and Ivan Wheen, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurer

p.25-26

Untitled (BNH) , 2013 oil and archival glue on canvas

122.0 × 168.0 cm

Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 2013 photo: Jessica Maurer

p.21-22

Untitled (SL) , 2014 oil, acrylic and archival glue on canvas 183.5 × 228.5 cm

Collection of the artist, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurer

p.24

Untitled (HM) , 2013 oil and archival glue on linen

245.0 × 167.5 cm

Private collection, Sydney photo: Jessica Maurer

p.27

Untitled, 2016

oil charcoal and archival glue on canvas

81.5 x 66.5 cm

Collection of Shirlene Boyd photo: Courtesy the artist and STATION, Melbourne

WRITER

Djon Mundine OAM

LENDERS

Art Gallery of New South Wales

National Gallery of Australia

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

STATION Gallery, Melbourne

Daniel Boyd

Leslie Boyd

Shirlene Boyd

Michael Schwartz and David Clouston

David Cowling

Gwen and Stewart Wallis AO

Karel and Ivan Wheen

Terry Wu

Anonymous collectors

Photography

Jessica Maurer, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

STATION, Melbourne

The artist wishes to thank family members

The Cairns Art Gallery gratefully acknowledges the support of the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, John Villiers Trust, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and STATION, Melbourne

ISBN: 978-0-9757635-8-2

© Cairns Art Gallery

Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in nay form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non commercial uses permitted by copyright law.