23 minute read

THE POWER OF MYTH

Paul Robertson

Senior Lecturer in Classics, Humanities, and Italian Studies University of New Hampshire

Advertisement

UNH students played a crucial role in the exhibit you ’ re seeing today. Most prominently, they wrote the labels next to each piece of art. Those brief little descriptions that tell you what you ’ re looking at they take a lot of work. The label writer not only must master both painting and the myth behind the painting, but they also distill a vast amount of knowledge, ancient texts, and modern theories into a mere seventy words.

Students also wrote the longer entries for each painting in this very catalogue. Here, instead of merely describing the painting, they must use their own expertise to guide the viewer. They become storyteller of myth, interpreter of paint, and historian of context. They explain the myth behind the painting, which in some cases is found in a huge variety of sources across hundreds of years, in Greek and Latin. They show the viewer how Beck follows a particular ancient account, or departs from it, and what this might mean. And they point to important features in the painting to invite the viewer to a deeper view: Beck’s brushstrokes around a particular figure, or her choice of color, or the placement of characters and their body language.

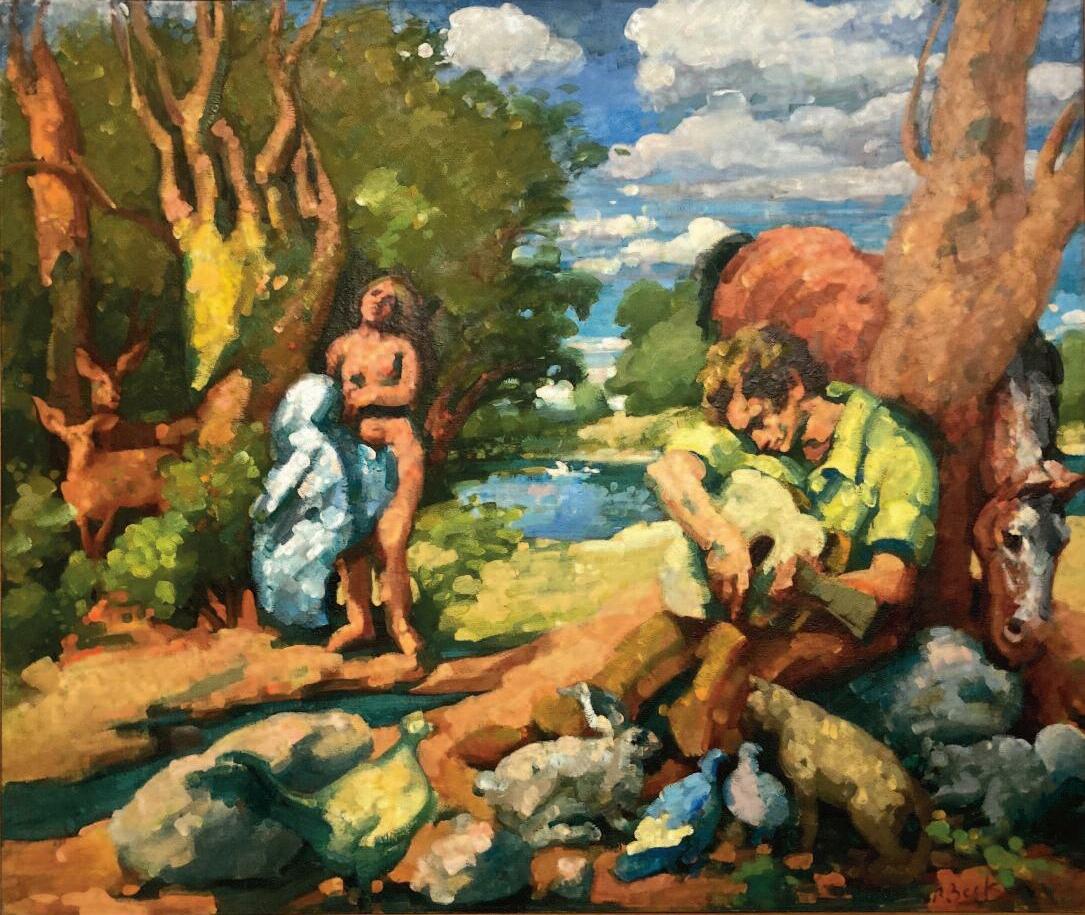

Both the labels and the longer descriptions in this catalogue were part of a course I teach, “ The Power of Myth.” Offered in the Department of Classics, Humanities and Italian Studies, this is an advanced course that builds on students’ prior work with Greek and Roman mythology. Whereas our “Introduction to the story of orpheus and eurydice is one of love and loss the son of Apollo, a renowned lyre player, orpheus falls in love with a nymph named eurydice the two consummate their love with marriage, but their euphoria is soon overtaken by heartbreak and tragedy as eurydice is bitten by a serpent while on a walk by a river, sending her to her death in the underworld orpheus appears in the foreground, the center of attention, a place where he found himself often when playing his music He is surrounded by animals infatuated with his artistry. Contrary to the title of the piece, he is not surrounded by forest beasts but rather more common and domestic animals, such as a horse, chicken, rabbits, birds, deer, squirrels, and possibly a cat. this may be an attempt to shift our perspective of what nature really is, toward a more bucolic and picturesque environment rather than one full of danger and ferocity.

Classical Mythology ” teaches the foundational stories of ancient Greek and Roman gods and heroes to several hundred students a year in a large lecture hall, “ The Power of Myth” is taught to just twenty students at a time in a seminar-style discussion class. I teach the course differently every time, creating a syllabus where the students work with me as co-researchers on projects. In past years, students in this class helped me write a book on the Cyclops. This year, the UNH Museum of Art’s reception of the Rosemarie Beck paintings was a stroke of great fortune, giving each student the opportunity to research a single work of art in great depth, joining their knowledge of ancient mythology to an important painter of the 20th century.

An undergraduate professor my own once told me that, if you ’ re lucky, your students become your teachers. This has never been more true than with this course and these students for this exhibition . They have spent weeks reading ancient Greek plays and Roman novels, and analyzed them alongside essays about Beck ’ s own life, work , and style. They have pored over dozens of Beck ’ s other works to make sense of ambiguous shapes, learned often from scratch how to write museum labels, and condensed a vast body of research into the highly readable, informative, and insightful information you see here. I’m extremely proud of the work they ’ ve done, and I trust you’ll learn a great deal from it too.

Beck dresses orpheus as a modest farmer, his humble earthy-colored outfit reflects the environment suggesting calmness and togetherness, charming the viewer just as he charms the world with his music while enchanted by the music, the nymph eurydice can be seen calmly walking through the forest the sun illuminates not only her unconcealed body, but the entire scene around her. this natural light is contrasted with the ominous shadow at her feet, perhaps prefiguring the serpent she later steps on Just as eurydice did not know what was to come, the viewer is also kept in the dark.

By depicting orpheus in contemporary clothing and eurydice nude, Beck introduces more depth into the two lovers’ relationship; based on their mutual attraction to music and beauty she seems to show the contrasting, yet complementary characteristics between nature and civility.

Chase Corliss

Beck’s love of finding one’s way around form in a painting is shown in this retelling of vergil’s tragic myth Orpheus and Eurydice eurydice’s two deaths are expressed in this scene through locations, objects, and positioning the artist sets the central scene on a staircase to represent orpheus’ decent to Hades and the dark plain of the underworld stopped midway, orpheus can see at the top of the stairs the lush, bright expanse of the world of the living and below him, at the foot of the staircase, lies his violin and accompanying bow, reminders that his immense musical talent was not enough to bring his wife back to life Beck exchanges a modern violin for the usual lyre (an ancient stringed instrument) However, the use of the instrument was purposeful: Beck was an accomplished violinist who studied music at oberlin before turning her studies to art and painting the painting shown in the top right corner, while unclear, may depict eurydice being carried on orpheus’ back over the river styx during their journey out of Hades Another point of uncertainty in this piece is the green object slumped against the staircase, perched open by eurydice’s left hand potentially a bag or satchel, the dark blue contents of the unidentified object spill on the ground orpheus is positioned rigidly, feet planted firmly on the floor, his neck curled down toward her; he casts a somber gaze at his dead lover eurydice is positioned loosely, dead in orpheus’ arms her feet narrowly dangling at the midway point of the staircase, so close to leaving the underworld! Her position may be a representation of orpheus’ broken pact with Hades, a reminder that if he had not turned around, her feet would have carried her up the staircase, to salvation and back to him

Megan Sorette

orpheus is a tragic hero with a heart-wrenching story of lost love He wed his love, eurydice, who died right after their wedding day Driven by grief, orpheus tried to retrieve her from the underworld, but failed because he broke a pact with Hades, god of the underworld Beck chose not to highlight these events, instead she focused on orpheus’ life after these tragedies

After the loss of his wife and his failed attempt to rescue her, orpheus found comfort in singing to and about nature He was the musically gifted son of Apollo, who himself had exquisite musical talent orpheus’ harmonious connection with nature was famous, for he was said to move the trees and stones with the power of his voice this is most likely the reason orpheus is a stark green color, to visually depict his connection to nature’s fertility and renewal

After his wife’s passing orpheus swore off the love of women in favor of idealized love found in the youth and beauty of boys Many women yearned for the gifted musician but were unable to obtain his affections no matter how hard they tried A few women, frenzied by their attraction to him and angered by his rejection, called for his murder perhaps the women mourners, surrounding orpheus in Beck’s work, are the women who ordered him torn him to pieces, who now feel remorse for killing him or they may be the woodland and river nymphs who mourned his death Beck depicts orpheus’ body intact, making his death less gruesome, and reinforcing his importance for the greek people, who commemorated him in their art and hymns in this painting based on shakespeare’s play The Tempest, Caliban attempts to force himself upon Miranda, the daughter of his master, the wizard prospero Caliban is shown much more human-like than he is described in the play, save for a tail running down his leg, the only indication of his monstrous qualities However, his nudity and his lunging posture, like that of a pouncing animal, creates more visual ties to the beastly aspect of his character

By contrast, Miranda wears a white dress, symbolic of the innocence and purity she seeks to protect Her wide-eyed expression registers her surprise Her arms are raised in defense, an upended teacup rests on the ground nearby, likely dropped in reaction to Caliban’s attack this scene is an interesting subject for a painting, as it is one of the few scenes in the play that happens off stage, being merely stated as an incident that happened before the events of the play even begin this fact is potentially hinted at by the gathering clouds in the background of the painting, showing that the titular “tempest” has not yet begun, but will soon

By depicting a scene that is overlooked by the play, Beck raises the issue of Miranda’s assault, bringing attention to Caliban’s violent aggression Caliban and Miranda both play minor roles in the play itself, Miranda serving as a love interest and Caliban serving as comic relief, roles Beck critiques Meanwhile, prospero, the main character of the play, is shoved into the position of a literal background character with her choice of scene and position of the characters, Beck intends for this painting to shift the focus to defining elements overlooked in the original source material: the aggressor and victim and male and female agency

Thomas Stewart

Beck engages with shakespeare’s The Tempest in Caliban and Miranda, depicting Caliban’s attempted sexual assault of Miranda the daughter of prospero, a wizard, exiled by his brother while the scene in this painting is relatively minor compared to the play’s complete narrative, the larger themes Beck explores the contrast between civilization and nature, purity, and unchecked desire are central to The Tempest

Miranda, the archetype of virtue and chastity, is pictured wearing a white dress and sandals Caliban, prospero’s servant, is depicted naked, representative of his uncultivated, barbaric nature Miranda’s modest dress in comparison to Caliban’s complete lack of coverage conveys the stark contrast between the two: civil chastity in opposition to savage coarseness

Caliban stands firmly behind Miranda, pulling at the ties of her dress He tries to literally undress her and metaphorically disrobe her of her pure maiden virtue in his left hand, Caliban holds an ambiguous green object the domestic items in the background and Caliban’s flushed appearance suggest this could be a vessel containing alcohol that catalyzed Caliban’s action on the other hand, the green color of the item may represent Caliban as a symbol of uncivilized nature invading Miranda’s civilized space Namely, this item could be a fish in reference to Caliban being described as “a strange fish!” in shakespeare’s play

Beck’s placement of these two figures in a domestic setting may be another way to contrast Miranda’s civility with Caliban’s savagery: his nudity reveals his true nature and shows he does not belong Beck seems to be saying his violent intentions are out of place in a civilized world

Gabrielle Jarrett

through vivid color and composition, Beck updates icarus’ fall with a modern-day perspective in the original myth, Daedalus and his son, icarus, had been imprisoned in a tower on the island of Crete by king Minos Daedalus, a brilliant inventor, devised a plan: he fashioned feathers and wax to create wings in order to fly safely, Daedalus warned icarus to travel between the extremes, warning him of the dangers of the sea and sun Despite Daedalus’ warning, icarus became lost in the joy of flight and flew too high, causing the wax to melt, leading to his fall and demise Beck has adjusted elements of the myth to emphasize the larger story Daedalus does not make an appearance, instead Beck focuses on icarus, who ignored his father ’s guidance and gave into his youthful spirit Beck also increases the number of people present for icarus’ fall, emphasizing their role within the myth in the original version (ovid, Metamorphoses Book 8), only a few men working on land and sea see them; in Beck’s depiction, the beachgoers are too preoccupied to notice only one figure looks up and points as icarus plummets the moral of his fall, Beck seems to suggest, is that life will continue with or without us, and time stops for no one Despite the tragedy of icarus and its caution, generations of humanity will face the same trials

Jillian Jezior

the original texts of the story of icarus and Daedalus tell of a son and father escaping the island of Crete using the father ’s invention of wings made of wax and feathers Daedalus warns his son to not fly too high, as the sun may melt the wax successfully flying from the island, icarus becomes drawn to the heavens and leaves his father to fly higher icarus flies too close to the sun, the wax melts, shedding the feathers as he falls into the blue sea, yelling to his father until the water drowns his cries this story represents a cautionary tale about overambition and hubris while neglecting dangers and consequences

Beck’s embroidery contrasts the dreadfulness of icarus’ death against the beauty of his youth and the scenery the needlepoint shows icarus plummeting, the red feathers of his wings aflame, moments from certain death, His father Daedalus is safe on the ground watching in fear as his son nears the unforgiving sea the background of the piece shows their ultimate goal, either setting their sights on reaching the faraway lands, or showing how far they escaped the island of Crete Daedalus, and his inventions, are what end up getting icarus killed, by breaking the order of nature and achieving the impossible; nature is hostile to divine overachievers the sky of the artwork mirrors the arc of the tale: Beck changes the sky from bright colorful rays to the setting sun, showing the descent of the sun and son icarus’ fall depicts the end of a short, bright life and the dark sorrow that follows Daedalus, mourning the death of his only child icarus and his father Daedalus, an ancient greek inventor famous for creating the labyrinth that housed the Minotaur, escaped from the island of Crete using wings that Daedalus fashioned from wax and feathers. Before the two set off on their flight, Daedalus relays a warning to his son: Do not fly too high or the sun will scorch the feathers. icarus’ recklessness in ignoring this warning is a metaphor for the consequences of overambition and pride Beck, however, chooses to focus our attention on Daedalus by painting events that take place after icarus’ death. in this scene, most likely based on the story of icarus told by ovid in his Metamorphoses, where Daedalus has "caught sight of the feathers on the waves, and cursed his inventions,” icarus has already fallen into the sea and drowned Daedalus, having recovered his son’s body, struggles to hold him up, collapsing under his son’s weight and the unbearable grief of the loss of a child

Beck incorporates spectators who watch the drama unfold, a detail that appears first in ovid’s writing in ovid’s telling of the icarus myth, a shepherd, a fisherman, and a ploughman watch the flight. Beck places bystanders in this scene who witness icarus’ death serving as a cautionary tale for all of us

Liam Gaffney

Beck depicts a moving passage from sophocles’ Antigone: Antigone’s dreaded walk to her confinement which amounts to a death sentence for breaking Creon's mandate that no one bury polynices, Antigone’s brother the leadup to this moment in the play is important: in the play’s opening, Antigone approaches ismene, her sister, with a burial plan and asks her to help ismene bemoans what happened to polynices’ body but refuses to break Creon’s law As women, she says, they cannot challenge a king Antigone then acts alone

Later, Antigone challenges Creon when she is brought before him, claiming that he is overstepping his authority as the city’s ruler and is undermining moral principles by barring polynices’ burial and deciding his fate the absence of funeral rites, she contends, would be a sacrilegious act against the gods themselves polynices’ spirit would be unable to find peace in the hereafter if the body was not buried ismene hoping to save her sister claims to have helped bury their brother, but Antigone rejects her defense; Creon, unbending, sends his niece to die in a cave, the dramatic moment depicted here in the painting, Antigone can be seen wearing a rose-pink dress with her head tilted towards the ground, experiencing intense grief, which will only worsen as she waits to pass away alone Beck depicts her crossing a river, possibly the river styx, which in greek mythology one needed to cross to enter the underworld, perhaps symbolizing the transition from life to death there is another figure to the left, who already stands on the river ’s other side, hugging themselves and appearing distressed Could this be ismene? or is it polynices, who, having received a proper burial, reached the underworld and waits for Antigone to join him?

Beck’s Antigone cycle coincided with the loss of her husband, robert phelps, in 1989 and may have been a way for Beck to contend with the grief she was experiencing

Anna Robinson

the fate of the rebellious heroine of sophocles’ play, Antigone, begins with her two brothers clashing swords on the battlefield of thebes, each fatally wounding the other eteocles is given funeral rites while the other, polynices, is left to rot in the dust Antigone rebels against the authority of her uncle, king Creon, by ensuring polynices’ body is given the funeral rites required for his entrance into Hades’ realm

Antigone stands unapologetically proud, glaring at her approaching sister ismene who refused to assist Antigone with the burial of their brother the ultimate family betrayal Antigone’s arm ensnared in Creon’s punishing grasp likely represents their recent argument, as described in sophocles’ play Antigone ismene, the only figure in motion, is coming to the defense of Antigone this contrasts with the opening scene of sophocles’ play, which shows her refusing to assist her sister in burying polynices the obedient ismene chooses to do nothing, siding with her uncle out of duty Beck may have made her veil white as a sign of her virtue in this disruptive family conflict Antigone is not wearing a veil which could represent her rebellious behavior ismene’s dynamic position in the painting reveals her emotional instability, placed in the corner of the painting with her back turned to the audience the only figure who seems conflicted is the guard who turned Antigone in to save himself sophocles describes him stirred to pity by the plight of his prisoner the guard appears to be strong in stature but is weak-willed with his head bowed he seems to express regret in his betrayal of Antigone and his role in ensuring her death the guard’s decision sets in motion the tragic events that follow, and the onlookers may reflect the citizens’ concerns about the harsh unyielding rule of Creon

Beck presents the tragic consequences of disobedience tragedy, death, and different forms of grief are all present within her painting depicting the gruesome demise of a beloved couple

Antigone was the daughter of oedipus, the former king of thebes Her two brothers, eteocles and polynices, died in battle at each other ’s hands, fighting for the throne that Creon now occupies Because of polynices’ treasonous march on thebes, Creon commands that he be denied a proper burial Angered and confused, Antigone disobeys the orders of the king and is caught burying her brother As punishment, Creon despite being Antigone’s uncle sentences her to death by starvation once again, she defies him by committing suicide in despair, her lover Haemon, likewise takes his own life

Beck depicts tiresias, a blind seer, without a face, representing not only his blindness but perhaps also his lack of personality outside of his prophetic role Antigone’s intended and the son of Creon, Haemon, lies on top of his lover ’s deceased body the fabric she used to hang herself coils around her body, draping down from her resting spot Blood runs from Haemon’s self-inflicted stab wounds staining the surface of the slab red, reinforcing the goriness of the scene in the background, Creon’s castle bears down on the scene, representing his overbearing power the beauty of nature contrasts with the violence of human nature ismene, Antigone’s sister, points to the sky in disbelief, expressing her anguish at the unexpected tragedy (and that she refused to help her sister bury polynices) Beck contrasts ismene’s grief with Creon, who hangs his head with shame because of his son's actions and the consequences of his unbending decree Beck depicts Creon in modern funeral attire, referencing the universality of grief the moribund eurydice wears red, mourning with Creon who is unaware his wife will soon die

Rithvick Ganash & Frankie Castagno

Depicted here is a scene missing from sophocles’ Antigone, one of his famous theban plays set after the suicides of the titular heroine and her fiancé Haemon, Beck depicts a funeral procession, where their bodies are escorted from the cave where they died and returned to the city of thebes this scene draws on another literary work, william Butler yeats’ poem From The “Antigone,” that focuses on the young woman’s descent “into the loveless dust ” yeats’ poem and Beck’s painting together make an apt coda to sophocles’ play for while it cannot undo the lovers’s deaths, the funeral cortege allows the thebans to grant Antigone and Haemon the proper burial previously denied to her and her family to the procession’s far right, Creon is depicted in modern clothes, removed from the rest of the funeral cortege He looks on in mourning and regret at the bodies of his son and future daughter-in-law, the sword that Haemon fell upon clutched in his hands Antigone’s cave dominates the background, appearing to subjugate the surrounding lush, bucolic landscape thick, short brushstrokes give an almost frenetic, breathless air that simultaneously compliments the vivid brightness of the color scheme and belies the peaceful pastoralism of the theban countryside

Beck’s pastoral world is at odds with the somber nature of the painting’s subject At the center right of the foreground, clothed theban citizens carry a body shrouded in white, while to their left, unclothed enslaved people carry the other body, rendered in green the theban citizens are dressed in modern pants and button-down shirts, accompanied by a small black dog this places the story not in a farremoved time and place, but contemporary America Beck thus ensures that the tragedy and play’s themes of obedience, free will, and familial duty remain relevant

Ella Truesdale

Phaedra, 2002, oil on linen, 58” x 50” in the last years of Beck’s life, she became enthralled by the story of phaedra as told in euripides’ Hippolytus the story expresses love, rivalry, regret, despair, loss, and unintended consequences set in motion by its female protagonist phaedra is cursed by Aphrodite, causing her to fall in love with her stepson, Hippolytus she reveals her secret infatuation to her nurse who begged to know why phaedra was so ill the nurse betrays phaedra’s trust and tells Hippolytus about the forbidden love phaedra hangs herself in both shame and heartbreak she leaves for her husband to find an inscribed tablet the ancient version of a suicide note containing the lie that Hippolytus raped her, keeping the real reason secret Hippolytus, exiled from Athens by his father, meets his end after his father curses him poseidon sends a monstrous bull that causes Hippolytus to be dragged to death by his horses He is found dead by the sea Artemis, having cared for the wild man, tells theseus the truth about his son and what really happened Aphrodite, in the end, is the only one to blame in this painting, a contemporary version of phaedra sits upon her throne, staring out, above it all with the air of a noble woman removed, seemingly regretful of her love and the subsequent actions of her decisions Her despair is clear as her attendants bustle around her Hippolytus stands with his back to the beach where he eventually meets his death, while his father, theseus, points away as if telling him to leave Beck remarked that she felt similar to this in the last months of her life As she was in bed, sick with an inoperable brain tumor, her friends and art students were lively around her, never quite leaving her alone, though she may have felt, like phaedra, distant the short strokes used in Beck’s technique are arranged to form the vague shapes of her subjects when observed from a distance, the brush strokes come together to show a particular scene, depicting its overall essence rather than the details Her technique well captures phaedra’s inability to see the devastating results of her actions

Liberty Laarman & Hannah Brigham

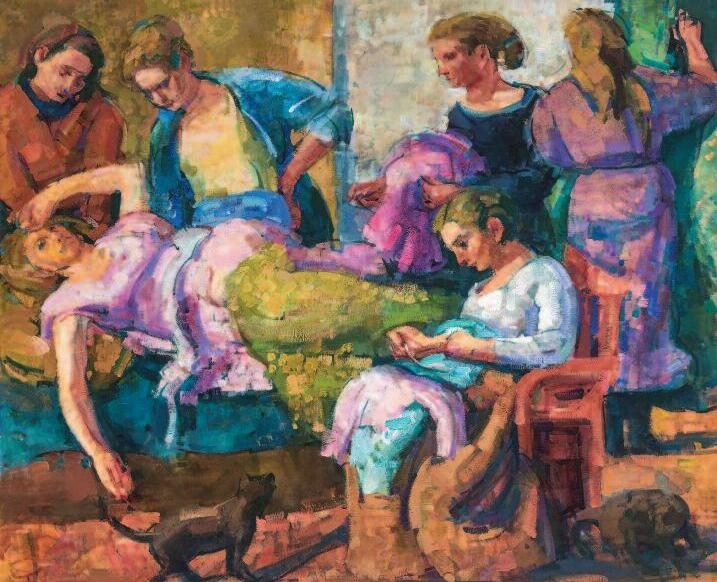

in a scene from euripides’ play Hippolytus, phaedra lies in bed, conflicted and distraught, cursed by Aphrodite she feels unfaithful toward her husband theseus because of the illicit love for her stepson Hippolytus Hippolytus, for his part, took a vow of chastity, devoting himself to Artemis, the virginal hunting goddess Aphrodite, feeling scorned and spiteful, cursed Hippolytus, but used innocent phaedra to punish him five women, probably nurses, dote tirelessly on phaedra as she lies sick, trying to help her overcome these feelings

Beck’s short and thick brush strokes add to the vagueness to the scene for example, we do not know if phaedra is dead or alive, because her face is not clearly painted phaedra’s arm is lifted to her forehead, which could indicate that she is still alive and suffering these mixed signals could be a manifestation of Beck’s fascination with ambiguous emotions, leaving it up to the viewer to interpret phaedra’s state of mind

Beck, interestingly, chooses to include cats in the scene; they are not represented in the original play the cats, shown as domestic pets, strangely lighten the heavy mood, and may minimize phaedra’s severe emotional dilemma insinuated as a choice between desire and abstinence Cats in art are traditionally signs of trouble and promiscuity, perhaps foreshadowing the harrowing events to come

Madeline Doyle

this painting draws heavily on euripides’ play Hippolytus, which focuses on the male characters, king theseus, phaedra’s husband, and his son Hippolytus in the play, phaedra is but a pawn, cursed by Aphrodite to love Hippolytus, her stepson, which leads to his destruction she eventually informs her nurse of this incestuous attraction; the nurse attempts to help by informing Hippolytus, but he is horrified and angered by this revelation rejected and embarrassed, phaedra hangs herself after writing a letter falsely accusing Hippolytus of attempted rape Her corpse is discovered first by the nurse, then by her husband theseus this discovery, mildly stylized, is the subject of Beck’s work. she alters the scene by including Hippolytus and phaedra’s young son at the moment of her death and discovery. By doing so, Beck calls attention to the masculine-focused nature of Hippolytus and hints at Hippolytus’ demise the facial expressions, unusually clear for Beck’s work, emphasize the male-centric world of the play through their clear lack of emotion Hippolytus turns his back on his stepmother with an uncaring countenance And despite expressions of mourning, theseus, and the nurses all seem oddly distant, showing that perhaps phaedra’s wellbeing was never their actual concern even phaedra’s son, whose honor she claimed to die to protect, seems unconcerned as he pets one of Hippolytus’ hunting hounds

Despite this, the color and positioning ensure that phaedra is the focus of the painting she is literally centered, her body positioned between all other characters in the scene. the turquoise and white sheets of her deathbed and noose, along with her green dress, make up a bright combination of colors that naturally draws the eye away from the gloomier, dark outskirts of the frame. Not all is good, however, as the painting also reveals that this moment is her last; just out of her reach, we can see her final letter on the floor. this letter, falsely accusing Hippolytus of sexual assault, will cause events to spiral out of control as theseus curses Hippolytus with death in retribution.

Jim Kertis

Atalanta, knowing that she is expected to take a husband, agrees to marry if her future husband can beat her in a footrace to deter men from racing, suitors who lose to her in the race are punished with death Atalanta races and defeats all suitors until Hippomenes arrives knowing that he will not be able to outrun her, Hippomenes prays to the goddess of love, Aphrodite, for help Aphrodite takes pity on the man and gifts him with three golden apples, which he can use to distract Atalanta during the race

Atalanta, determined to win, is shown with her head bowed and muscles taut Hippomenes seems to linger behind her, perhaps relying on his cleverness to win the race instead of physical strength Beck depicts the scene just prior to Hippomenes’ win one apple has landed on the path, the second aloft in mid-air, and the last golden apple, the key to victory, he holds in his hand, ready to launch Atalanta’s white flowing tunic may symbolize her last moments of freedom and innocence and serve as an ode to Artemis, the matron goddess of the hunt and virgins and Aphrodite’s rival who is frequently depicted wearing similar clothing the natural setting of the woods and the hunting dog that runs beside Atalanta honor Artemis’ domain Although Atalanta succumbs to Hippomene’s and Aphrodite’s scheme, in Beck’s drama she remains untamable and free

Molly Gearhart

As told in ovid’s Metamorphoses, Actaeon, completing his hunt, chanced upon the divine grove of Diana where she and her nymphs are bathing when the nymphs lock eyes with Actaeon, they quickly run to Diana draping the goddess as well as their own bodies when Diana realizes that a mortal man has come into her haven with unjust cause she feels infuriated and embarrassed in her fit of fury, she splashes the waters of the grove onto Actaeon, turning him into a stag and transforming the predator into prey escaping on nimble feet and realizing he is no longer human, Actaeon finds he cannot speak with strained options of accepting this new life or going home and risking an arrow to the heart, he turns back towards the woods with his hounds quickly approaching, he realizes that they no longer recognize him exhausted from the chase, Actaeon is overwhelmed as his dogs sink their teeth into his body, unaware it is their master crying out (in the form of bellowing) for them to stop

Beck’s vibrant take on this myth, which was first established in the writings of Callimachus’ Hymn to Artemis (Hymn 5) and later popularized through ovid’s Metamorphoses, is given a modern twist Diana wears a white bathing suit to express her virginal status and modesty Beck takes a synoptic view of the myth: rather than depicting a single moment of the story she shows two: Diana bathing; and Actaeon’s transformation into a stag this gives the impression that Diana has meted out her punishment and returned to bathing with little care for Actaeon’s violent death

Henry Huot

Beck creates the story of Apollo and Daphne with unfulfilled strokes of paint splattered across the canvas Beck’s interrupted brush marks leaves the viewer longing for completion and gives space for desire, allowing room for the viewer to process the ambiguity of the tale in the story, most famously told by ovid (Metamorphoses Book 1), Apollo comes across Cupid and taunts him about being unworthy of his bow Cupid, with his vengeful spirit, proves why he is also the master of the bow by crafting two arrows: one makes the person it pierces filled with love and the other makes the person it pierces repel love Cupid shoots the love-arrow at Apollo and the love-repellant arrow at the nymph, Daphne (her name means “Laurel-tree”) Apollo pursues Daphne, but Daphne does not reciprocate his love and runs away from him Daphne, pursued by Apollo calls out to her father, the river god peneus, to help her escape He answers her prayer and turns her into a laurel tree Apollo, saddened that he cannot have her, still loves her and vows to crown himself with her laurel leaves the omission of Cupid in this painting shows Beck focusing on a different aspect of the story: a grown man preying on a little girl showing Apollo as an adult, Beck asserts he has more agency over his actions than that of a girl who is frightened by him and rejects his advances ovid mentions in the text that after transforming into a tree Daphne bends to Apollo in reciprocation of his feelings, but Beck depicts Daphne turned away from the god, suggesting she interprets the story differently presumably, Beck wanted to show the struggle women deal with when faced with unwanted affection from men Brendon Le