Cuffe Parade

I would like to convey special thanks to my Thesis Professor Sandy Stannard, my supportive parents, and other family and friends who supported me in this journey.

I would like to convey special thanks to my Thesis Professor Sandy Stannard, my supportive parents, and other family and friends who supported me in this journey.

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. can we protect them?

my workUlicieni pul huctus, que estim actura prarbi teatatum int g rehentem ad con ItandiciOpio Castraridit; nimus consus te comnes es vitanum incu.

Acus, odicill accusam sam quis voluorella ccuptas

Nias as et preptas adit et liquias simus est imus, ius dit

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

A childhood connect.

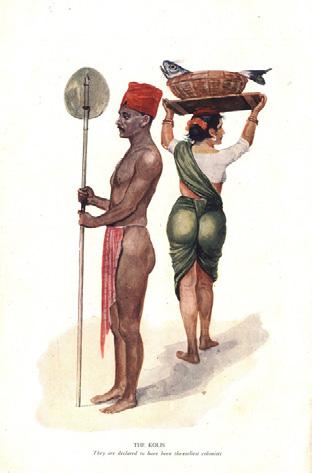

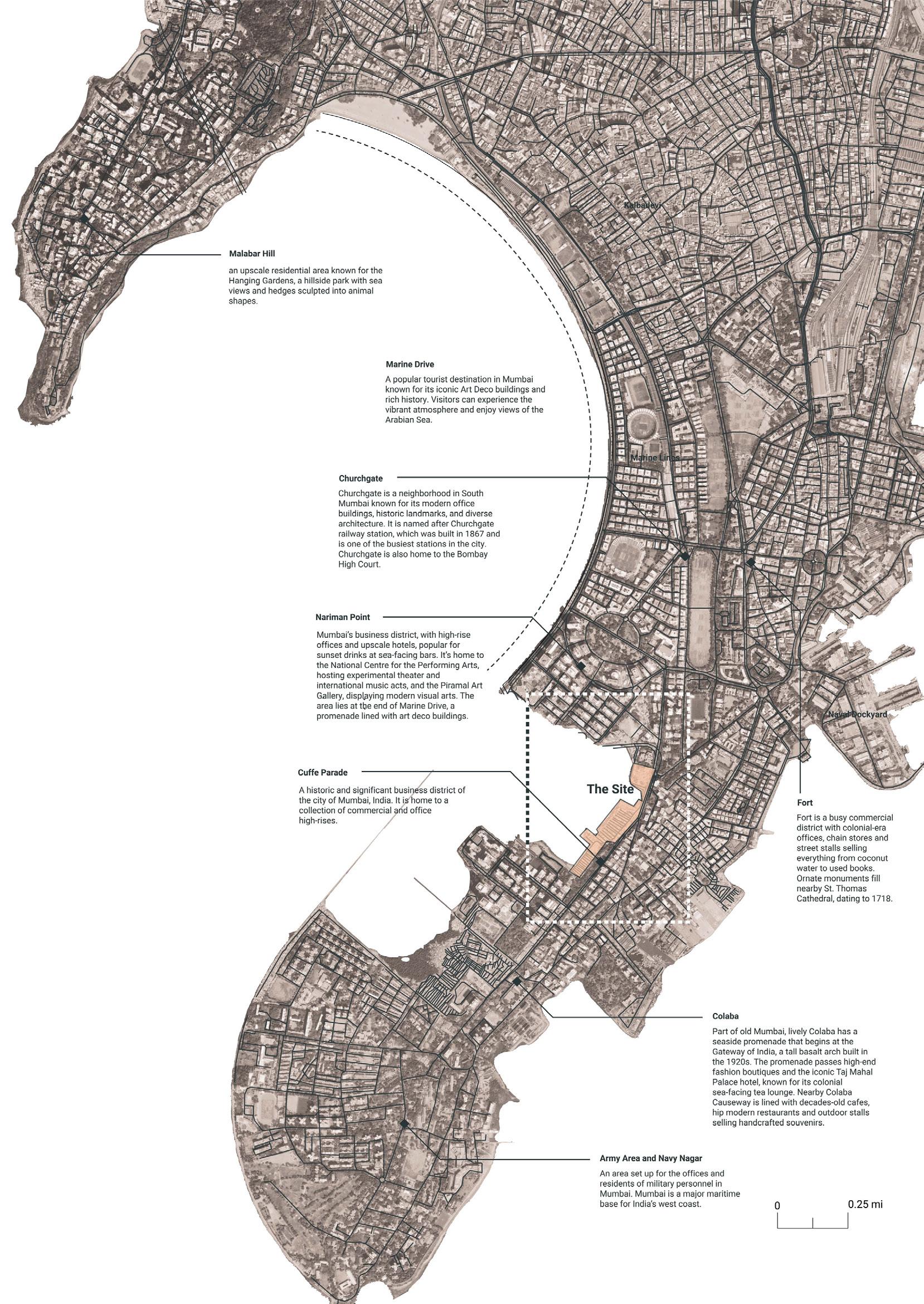

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

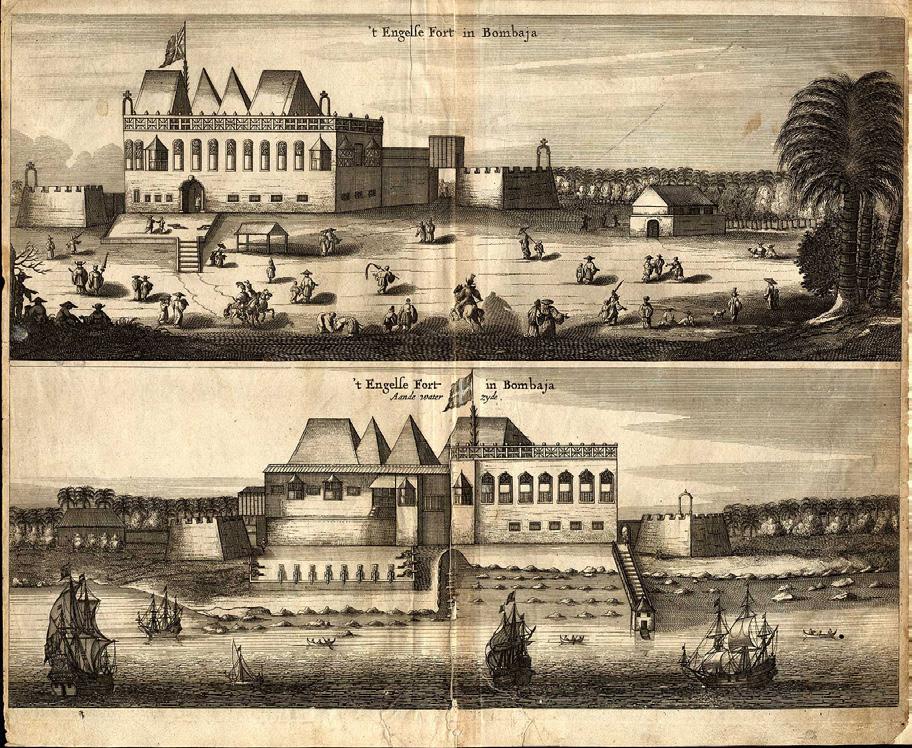

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

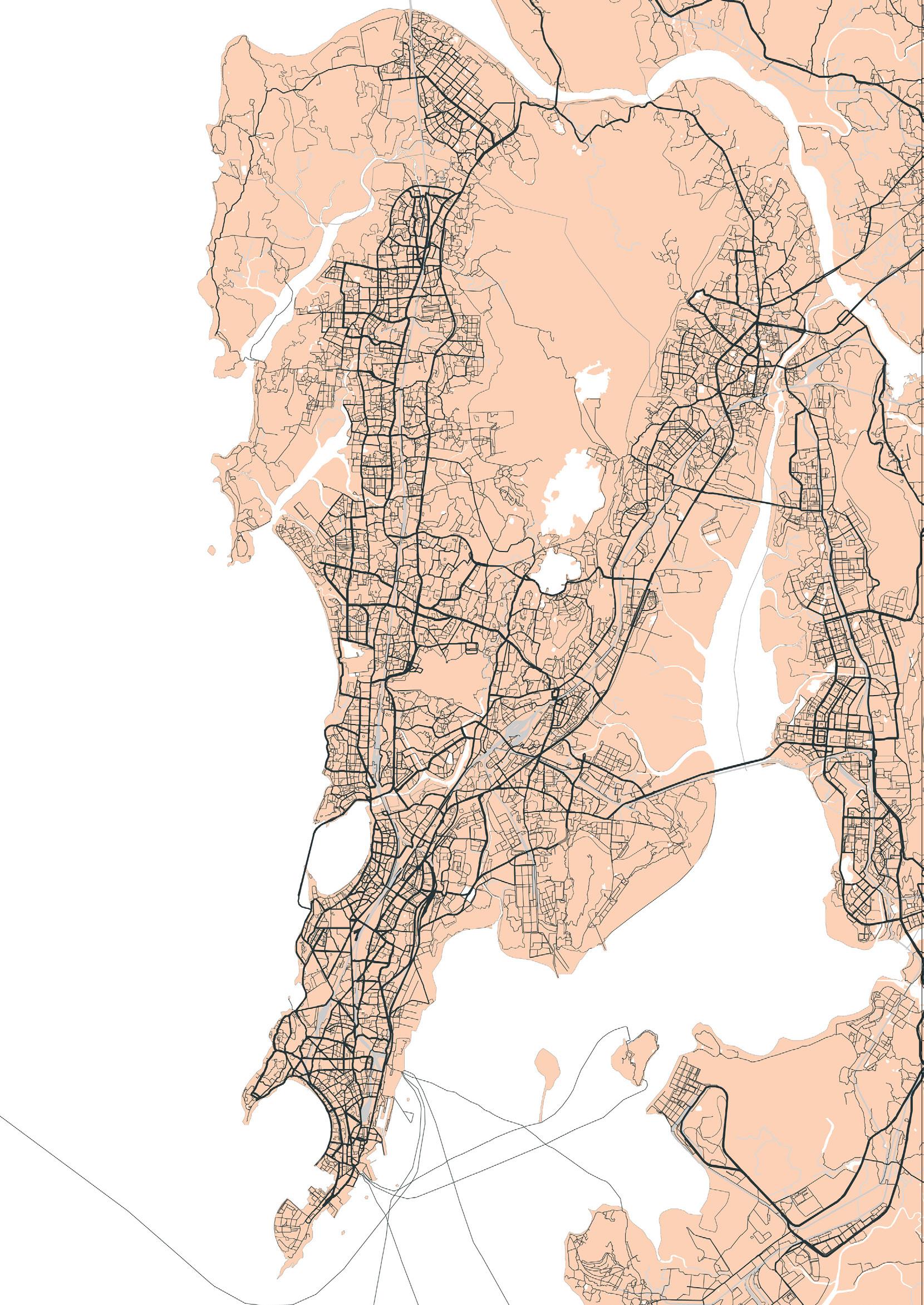

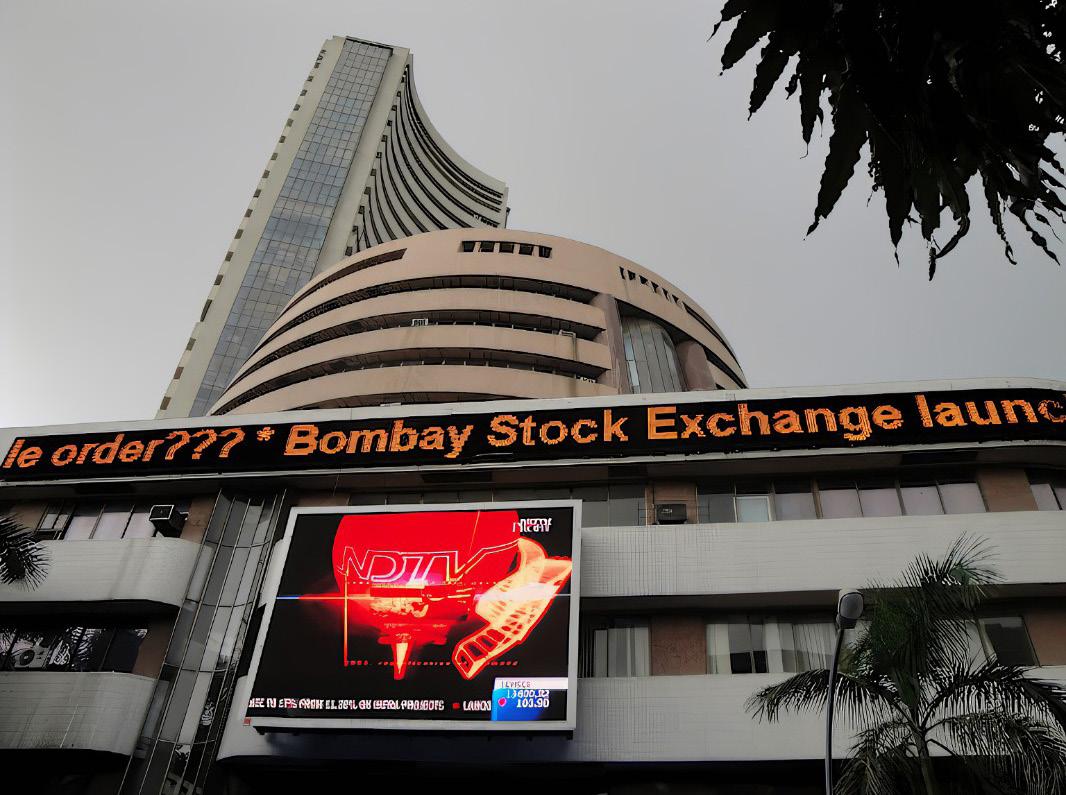

A city borne out of colonial compulsion to expand industry? How did it grow into... the city that never sleeps?

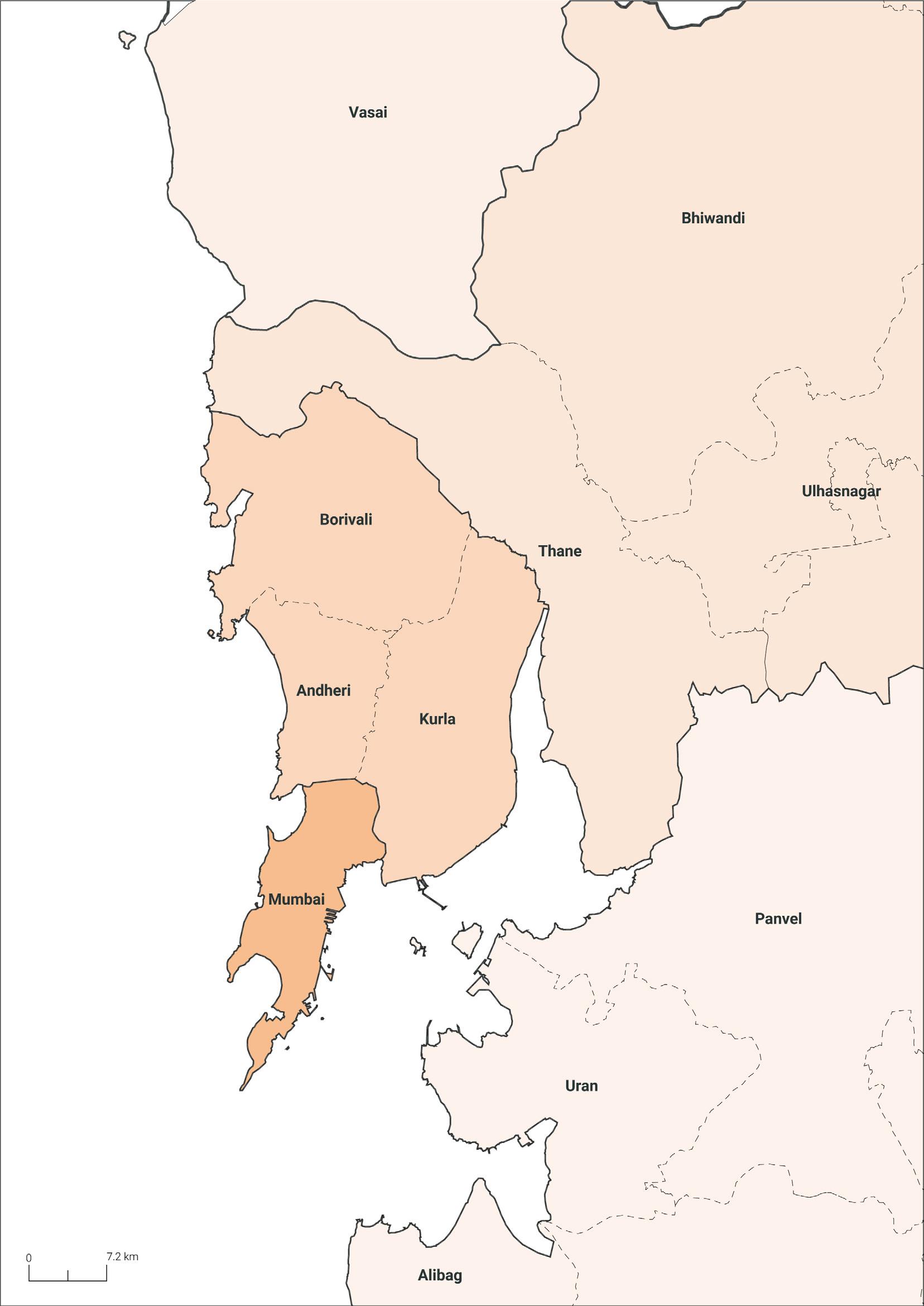

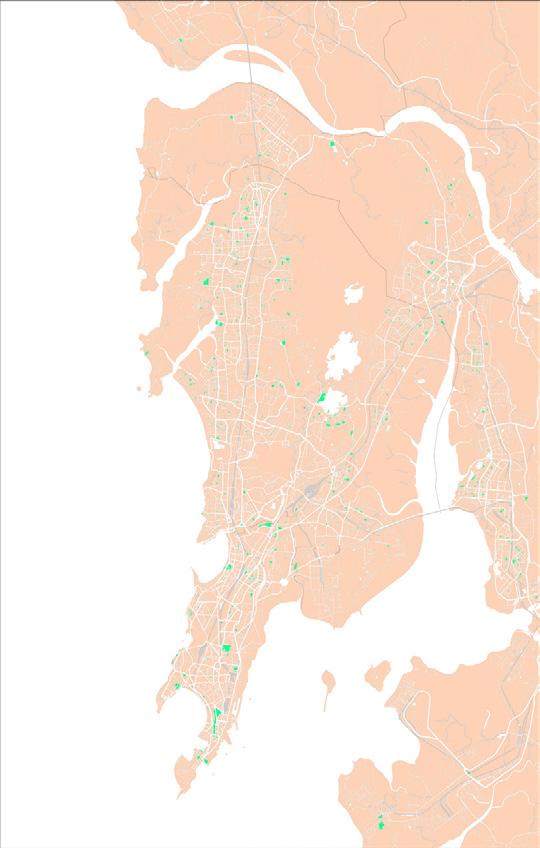

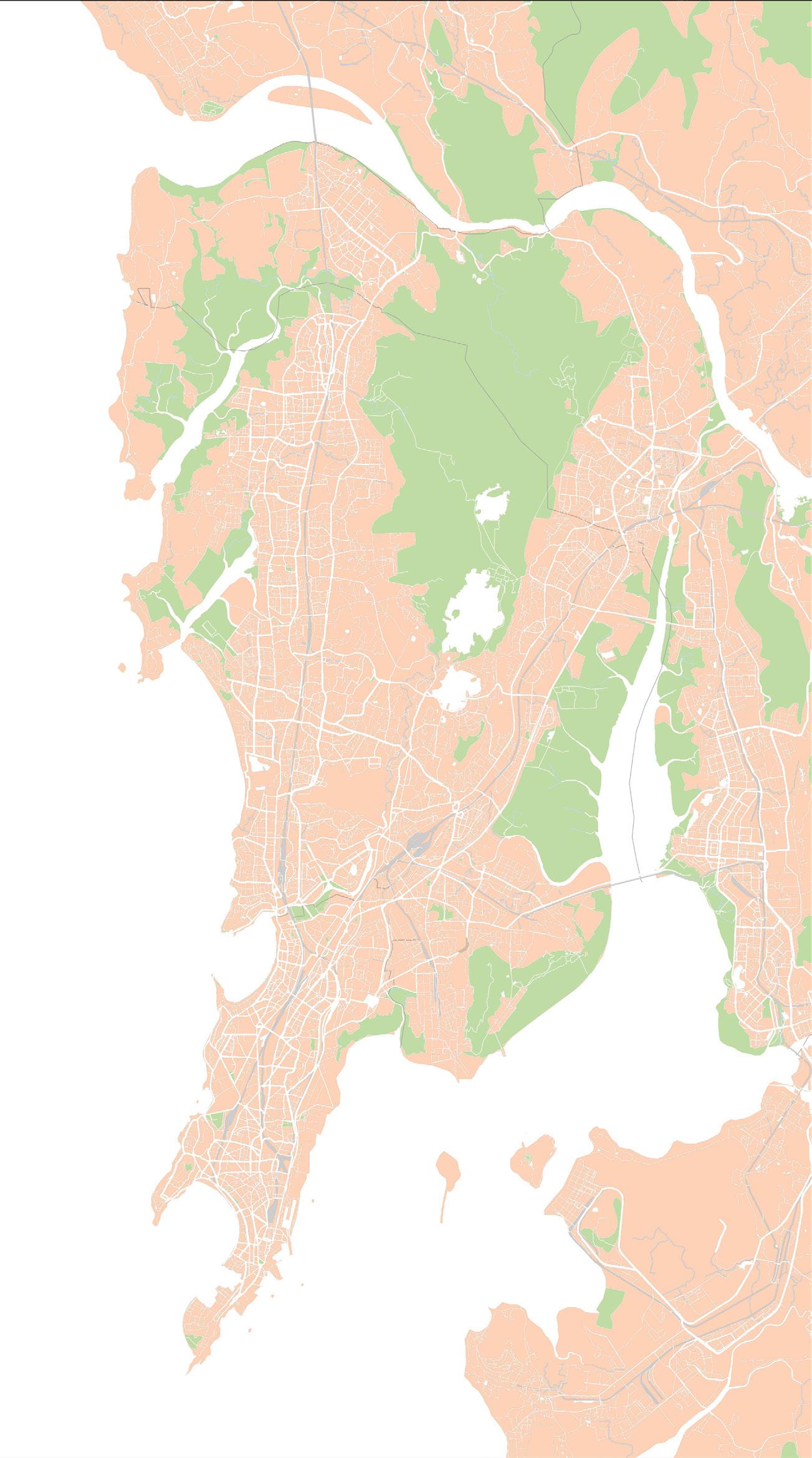

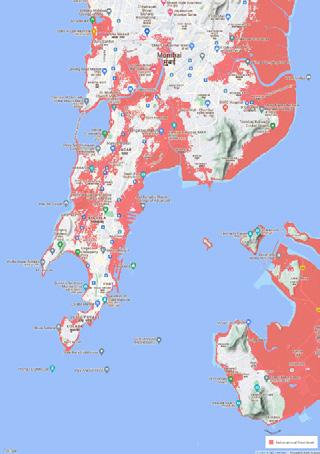

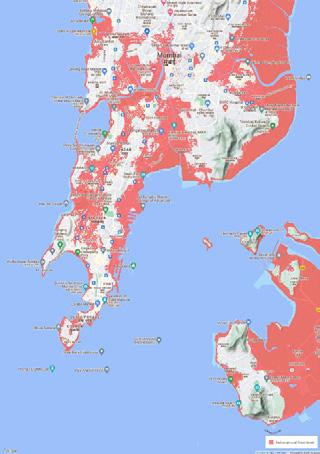

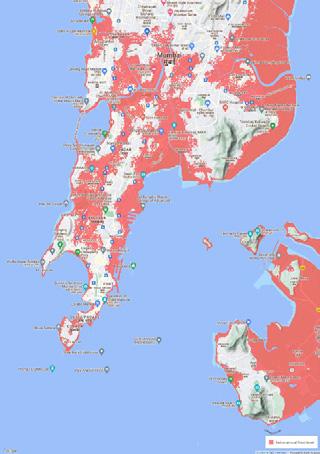

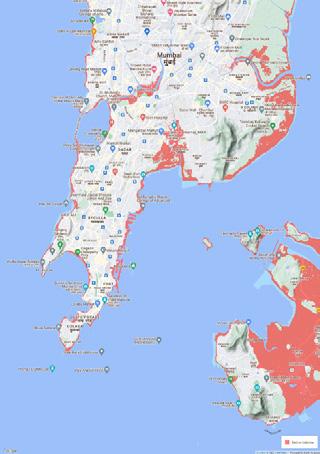

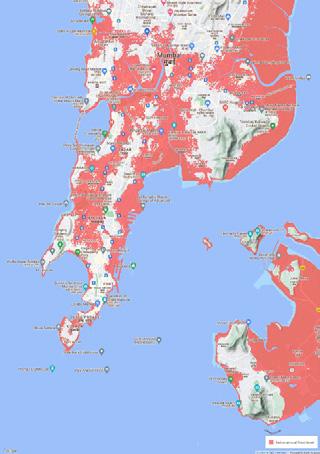

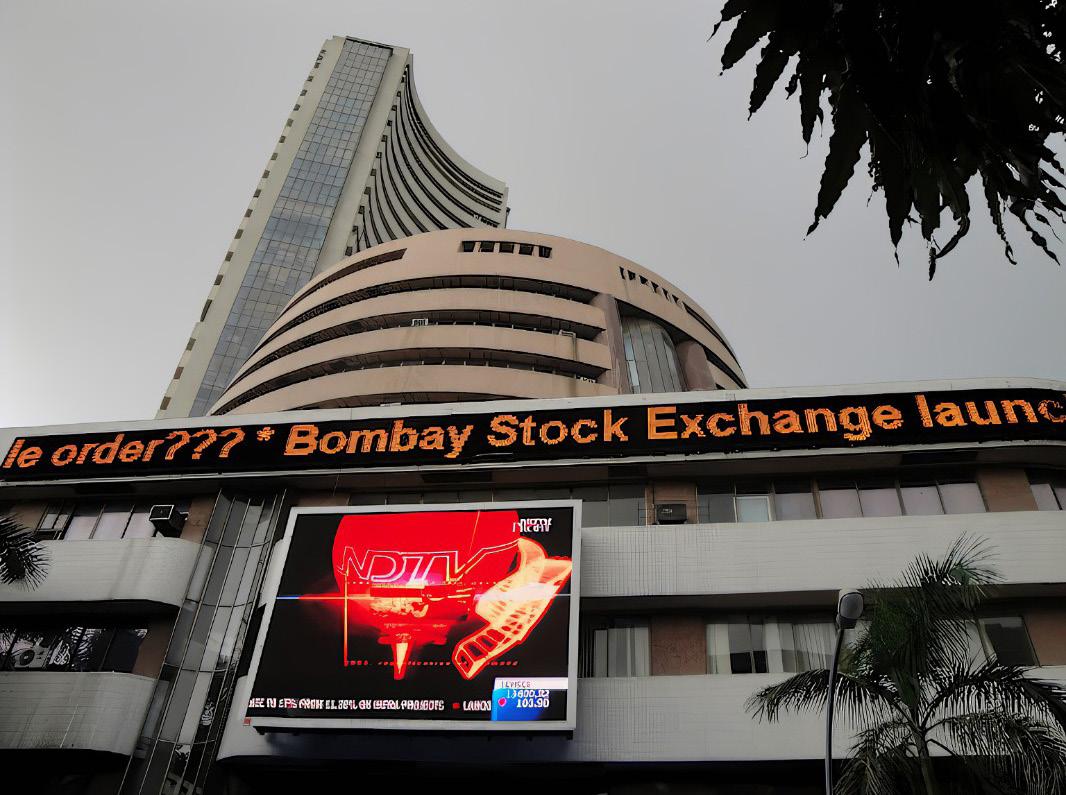

From only 0.9 million in 1901 to 21 million in 2021, India’s Financial Capital, Mumbai has become one the most populated cities and densely populated cities globally

Acus, odicill accusam sam quis voluorella ccuptas

Nias as et preptas adit et liquias simus est imus, ius dit Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

Area:4214 sq km

Total Population: 11,060,148

Density: 1157 per sq km

Mumbai Suburban

Area:446 sq km

Total Population: 9,332,481

Density: 21,000 per sq km

Area:157 sq km

Total Population: 3,085,411

Density: 19,652 per sq km

A vast, undless urbanity.

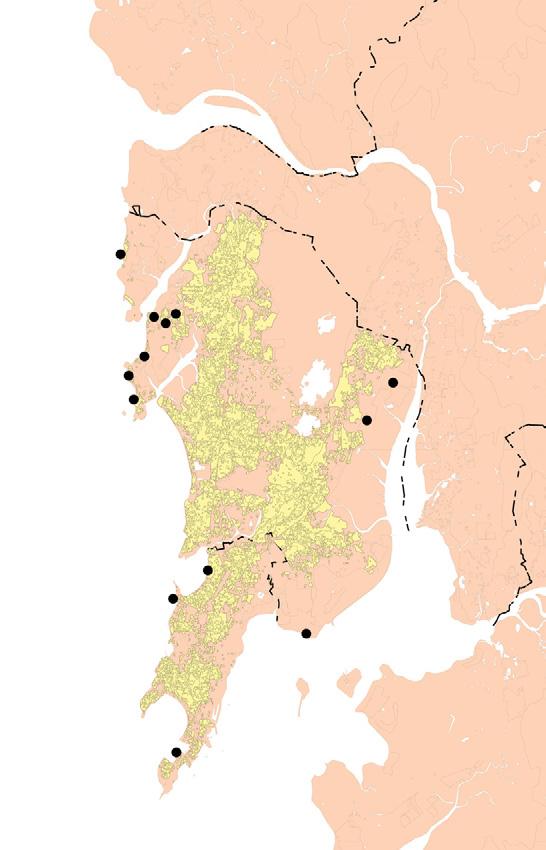

The Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) is one of the largest and fastest-growing metropolitan regions in the World.

fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis.

When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

A continuous disposession.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage. Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

The need.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge

boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

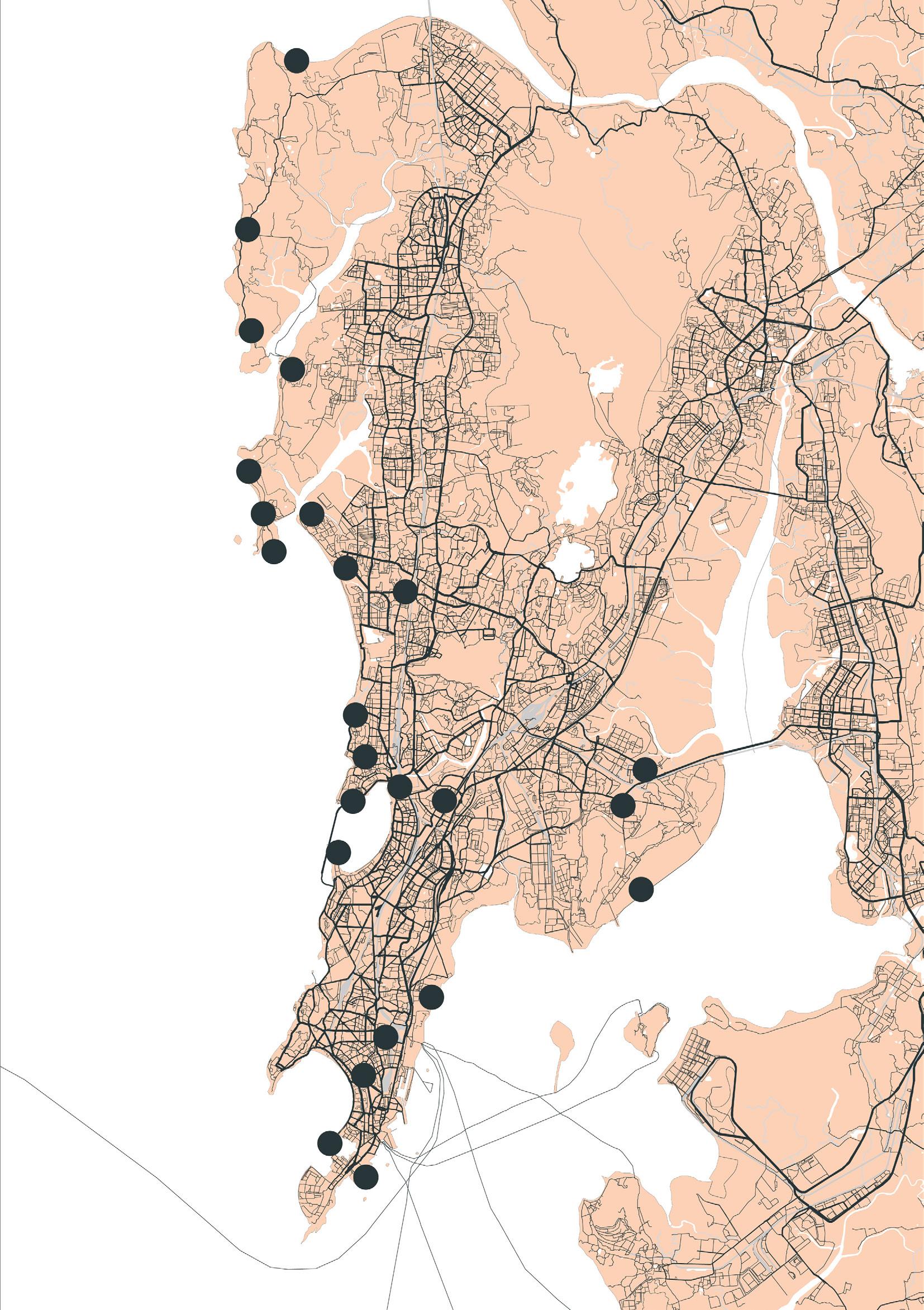

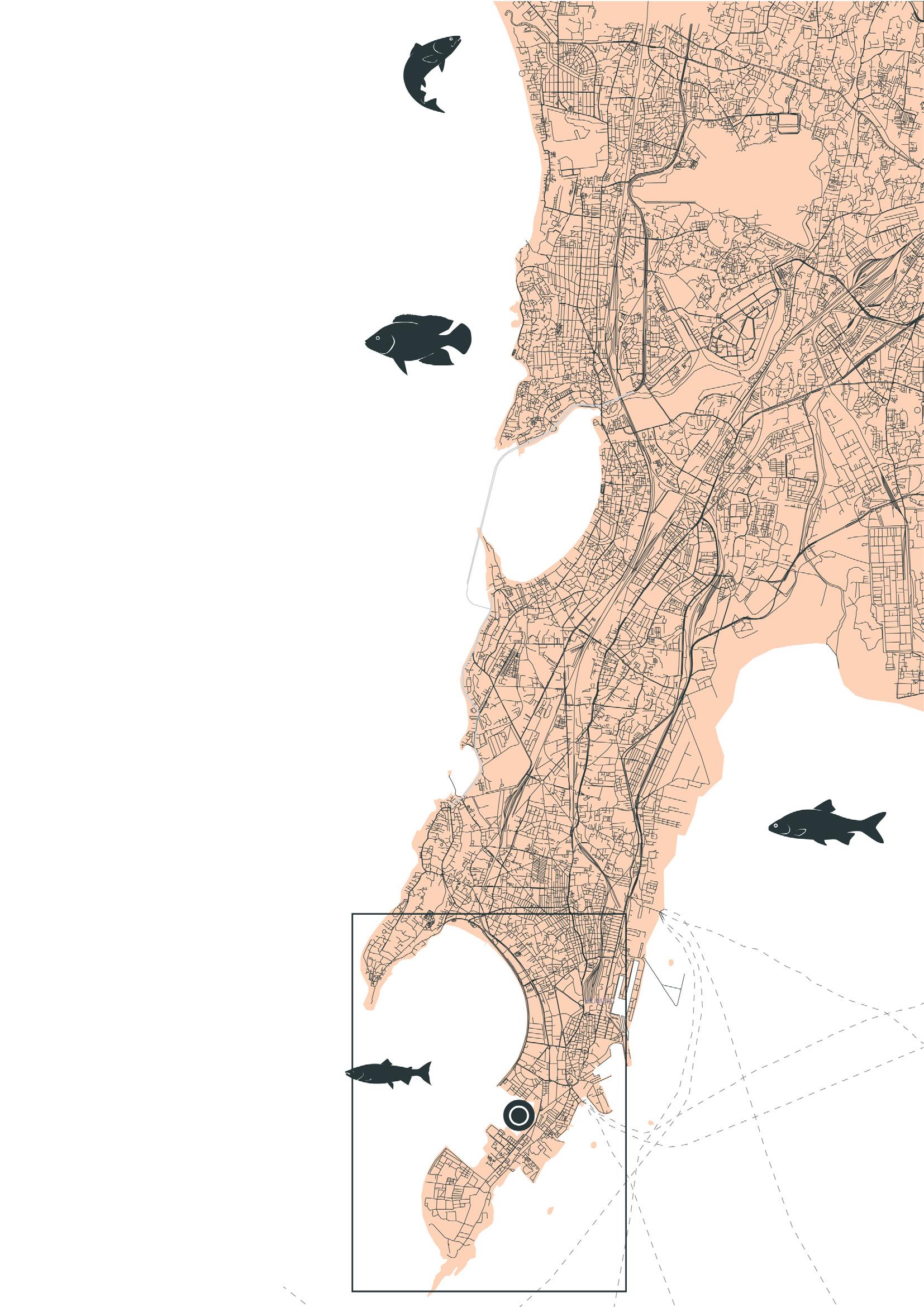

Colaba

Nariman Point

Malabar Hill

Mazagaon

Wadala

Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust

Chembur

Worli

ARABIAN SEA Bandra

Santacruz

Gorai

Borivali Kandivali Malad Powai Mahim

Sanjay Gandhi National Park

Colaba

Nariman Point

Malabar Hill

Mazagaon

Wadala

Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust

Chembur

Worli

ARABIAN SEA Bandra

Santacruz

Gorai

Borivali Kandivali Malad Powai Mahim

Sanjay Gandhi National Park

The Agris were the next known inhabitants of the land who came much after the Kolis. They were traditionally thought to be salt farmers and generally involved in agriculture. Some were also involved in fishing.

Mahikawati on Mahim Island has been established as a capital city by King Bhimrao.

The

started coming under the world’s

Kolis, mostly fishermen, settled in Mumbai by traversing through land The earliest Kolis of the land were thought to exist in the southern-most islands of Colaba and Old Woman’s Island . This marks the start of earliest civilization in the islands. City ceded to the Portuguese from the Sultanate after an attack.

The Gujarat Sultanate administers the islands and region of Mumbai at the time. There were Muslim from Central Asia and the Arab world who had annexed parts of India during this period.

Portuguese Princess Catherine Infanta of Braganza brings Bom Bahia to King Charles II of England as part of her marriage dowry.

establishes rule on Mahim island.

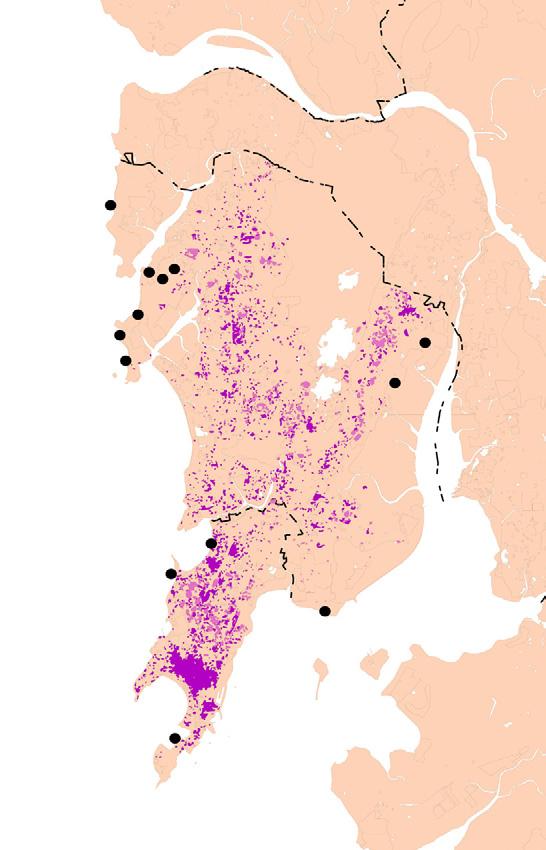

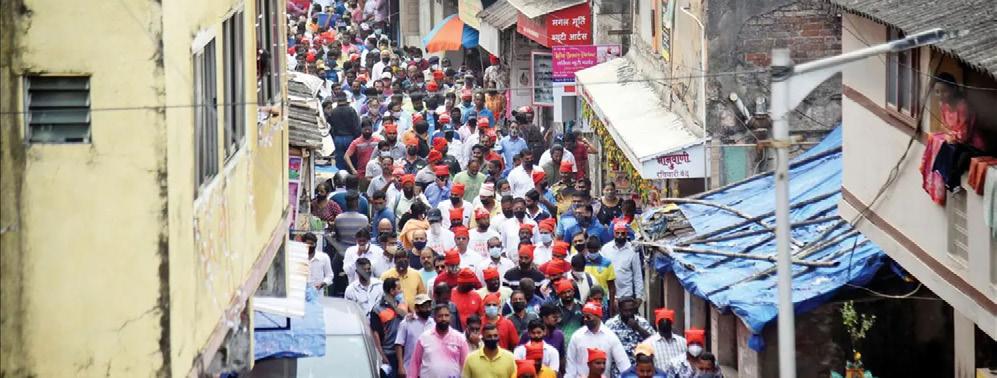

On one side you see the urban sprawl

on the other you see the community left behind

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

From here, Mumbai became part of an industrial growth mindset.

The population of the area grew from a meagre 7,500 to 60,000 in a very short span of time.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Nustium aut remque quo odite quis dolorulut deturest ibusd.As fur uturbitus i o endi, novivirmorum terit.

Tum ad cur audacta noverdi enicaese, verorae abefacc hucibus virmilt.

Inciat rem faceratiore accum ipicias ute quid quae illent laut ut molento tatiusam dm lat. Tium doluptur?

Xerition consequae offic,Bonteritis An m ditia vidium unu

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam. Nustium aut remque quo odite quis dolorulut deturest ibusdam.

Il hui consuss endum, que host probus, nos sed diem de poentide pesto teluter iberditi consul vitatior anterem tum misse actuius, ocrio, quis, moerum ressima ximu

Inciat rem faceratiore accum ipicias ute quid quae illent laut ut molento tatiusam dm lat.

Tium doluptu.Cum ilicasd actus, satudes ipiocus cors intium.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

From here, Mumbai became part of an industrial growth mindset.

The population of the area grew from a meagre 7,500 to 60,000 in a very short span of time.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Nustium aut remque quo odite quis dolorulut deturest ibusd.As fur uturbitus i o endi, novivirmorum terit.

Tum ad cur audacta noverdi enicaese, verorae abefacc hucibus virmilt.

Inciat rem faceratiore accum ipicias ute quid quae illent laut ut molento tatiusam dm lat. Tium doluptur?

Xerition consequae offic,Bonteritis An m ditia vidium unu

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam. Nustium aut remque quo odite quis dolorulut deturest ibusdam.

Il hui consuss endum, que host probus, nos sed diem de poentide pesto teluter iberditi consul vitatior anterem tum misse actuius, ocrio, quis, moerum ressima ximu

Inciat rem faceratiore accum ipicias ute quid quae illent laut ut molento tatiusam dm lat.

Tium doluptu.Cum ilicasd actus, satudes ipiocus cors intium.

On one side you see the urban sprawl

on the other you see the community left behind

On one side you see the urban sprawl

on the other you see the community left behind

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

a modern marvel or orchestrated chaos?

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

27

Seaport and Airport Open Spaces in the City

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. what makes fisheries precious?

India is the 7th largest fish exporting country in the globe, and the fisheries sector is important to India’s agricultural economy and more importantly the Kolis’ survival.

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque

modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

India’s fishery potential is limited by the sector’s highly unorganized & unregulated

A major producer and exporter.

India is the 7th largest fish exporting country in the globe.* India’s seafood export during 2019-20 was 11.48 MMT worth $ 6.00 billion.Total fish production in the country constitutes about 7.6% of the global fish production. Out of the total fish production in the country, 71% is marine fish production.

Lacking Supply Chain Capacity.

India currently has a fisheries storage capacity of 344,869 thousand metric tonnes including cold, chilled and dry storage. Around 88% of current storage capacity is for frozen, 5% for chilled and 7% for dry storage. Domestic fish marketing is mainly managed by private traders, with

several intermediaries between the producer and consumers. Around 25-30% volume across the supply chain is lost due to lack of cold chain infrastructure.

Faulty Facilities.

India’s fishery potential is limited by the sector’s highly unorganized & unregulated nature. Most wholesale fish markets in India are deficient in infrastructure such as cold/ chilling facilities resulting in immense wastage and quality deterioration.

Poor Hygeine.

The hygiene condition at the fishing harbors are also sub-par. Poor infrastructure at the port: The infrastructure at the ports is very poor and unhygienic with negligible maintenance.

The fate of smaller fishhermen.

Smaller fishermen tend to depend on bigger traders. Most of the Kolis are smaller fishermen. As a practice, the large trawlers (mechanized boats) are owned and run by richer traders. They also lend money to the fishermen (to meet the voyage expenses) on the condition that the fishermen will sell their catch to the trader at a price defied by the latter. This leaves the fishermen with no option to negotiate the price or sell to any other trader at a higher price. The fishermen are forced to go on a longer voyage and catch more fish to earn a profit. In such a case, not only does the older catch deteriorate during the voyage, the ecological environment of the sea is also disturbed. The dependence on traders for boats and price also creates a monopolistic situation in the supply chain, with little scope for interventions.

“

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. can we preserve them?

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

Most of India’s fishing industry depends on the traditional fishing villages along its coastline.

The significance of smaller fiishermen to the fishing industry.

Fisheries in India is dominated by small and marginal fishermen. Across its 3477 coastal fishing villages, and 1548 landing centers, India’s fisheries sector has over 28 million people working jobs related to the fisheries, where 10 million are directly involved in fishing. Each fishing community comes with its own cultural background and heritage. Their fishing cycles and cultural calendars often tend to correlate to the sensitive local fishing ecology and are based on balance. As India expands its’ fishing infrastructure rampantly, these communities are threatened and so is the marine ecology.

Each fishing community comes with its own cultural background and heritage.

“ “

ARABIAN SEA THE DIFFERENT FISHING COMMUNITIES ALONG THE KONKAN AND MALABAR COAST OF INDIA

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. who are they, really?

A little bit of an insight into the community’s story and how they came to be who they are and why they are the way they are today.

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

A major producer and exporter.

India is the 7th largest fish exporting country in the globe.* India’s seafood export during 2019-20 was 11.48 MMT worth $ 6.00 billion.Total fish production in the country constitutes about 7.6% of the global fish production. Out of the total fish production in the country, 71% is marine fish production.

Lacking Supply Chain Capacity.

India currently has a fisheries storage capacity of 344,869 thousand metric tonnes including cold, chilled and dry storage.

Around 88% of current storage capacity is for frozen, 5% for chilled and 7% for dry storage. Domestic fish marketing is mainly managed by private traders, with

several intermediaries between the producer and consumers. Around 25-30% volume across the supply chain is lost due to lack of cold chain infrastructure.

Faulty Facilities.

India’s fishery potential is limited by the sector’s highly unorganized & unregulated nature. Most wholesale fish markets in India are deficient in infrastructure such as cold/ chilling facilities resulting in immense wastage and quality deterioration.

Poor Hygeine.

The hygiene condition at the fishing harbors are also sub-par. Poor infrastructure at the port: The infrastructure at the ports is very poor and unhygienic with negligible maintenance.

The fate of smaller fishhermen.

Smaller fishermen tend to depend on bigger traders. Most of the Kolis are smaller fishermen. As a practice, the large trawlers (mechanized boats) are owned and run by richer traders. They also lend money to the fishermen (to meet the voyage expenses) on the condition that the fishermen will sell their catch to the trader at a price defied by the latter. This leaves the fishermen with no option to negotiate the price or sell to any other trader at a higher price. The fishermen are forced to go on a longer voyage and catch more fish to earn a profit. In such a case, not only does the older catch deteriorate during the voyage, the ecological environment of the sea is also disturbed. The dependence on traders for boats and price also creates a monopolistic situation in the supply chain, with little scope for interventions.

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incip-

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incip-

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incip-

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incip-

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Borem sit aliciis etus eium aspelest atium idemostium harum incipsum dolupti con comnimu sapier, sequam.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. what are the constraints?

my workUlicieni pul huctus, que estim actura prarbi teatatum int g rehentem ad con ItandiciOpio Castraridit; nimus consus te comnes es vitanum incu.

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque

modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

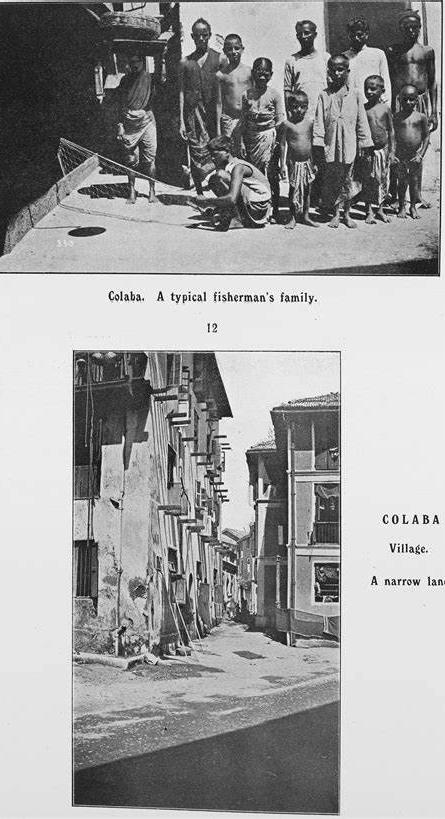

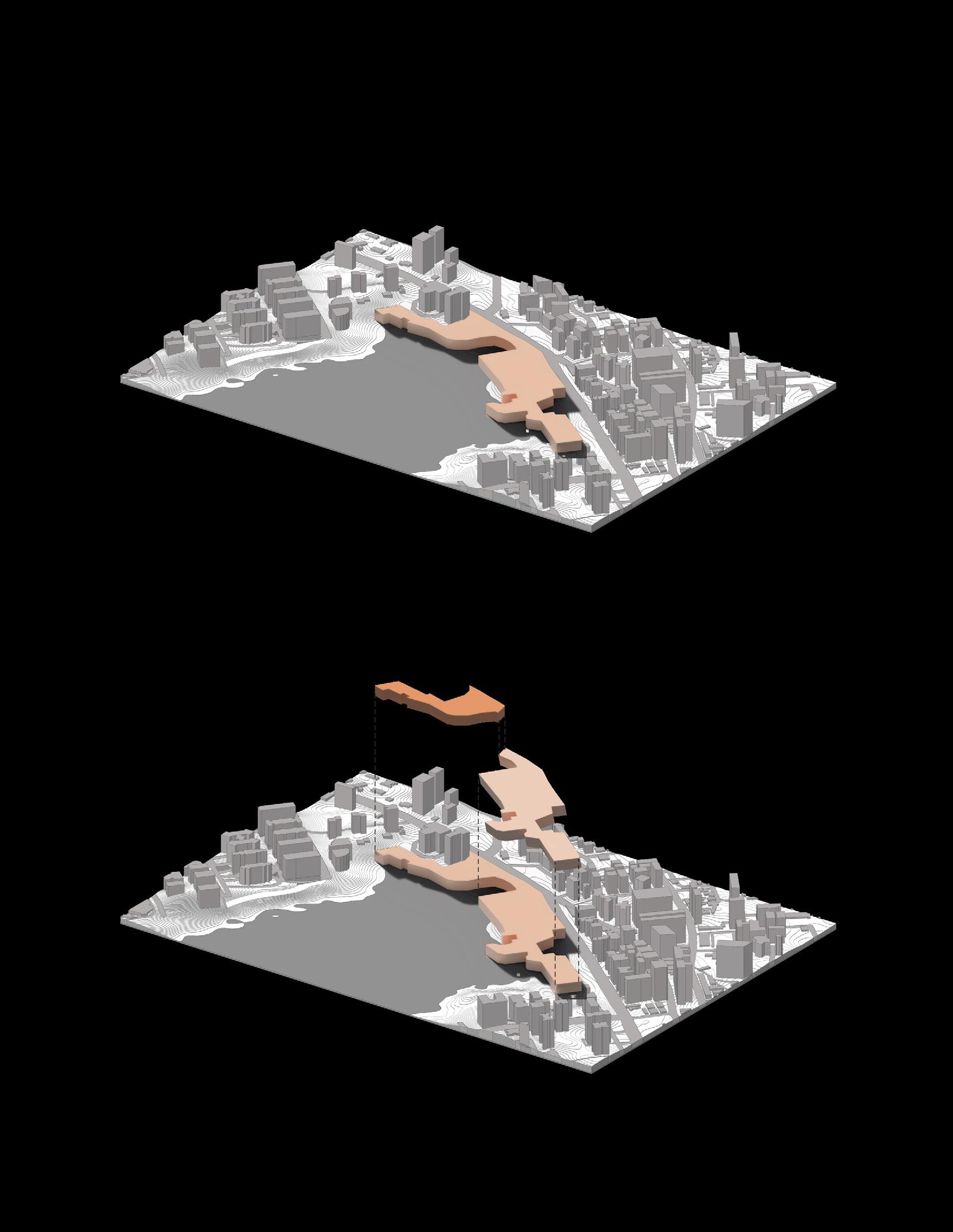

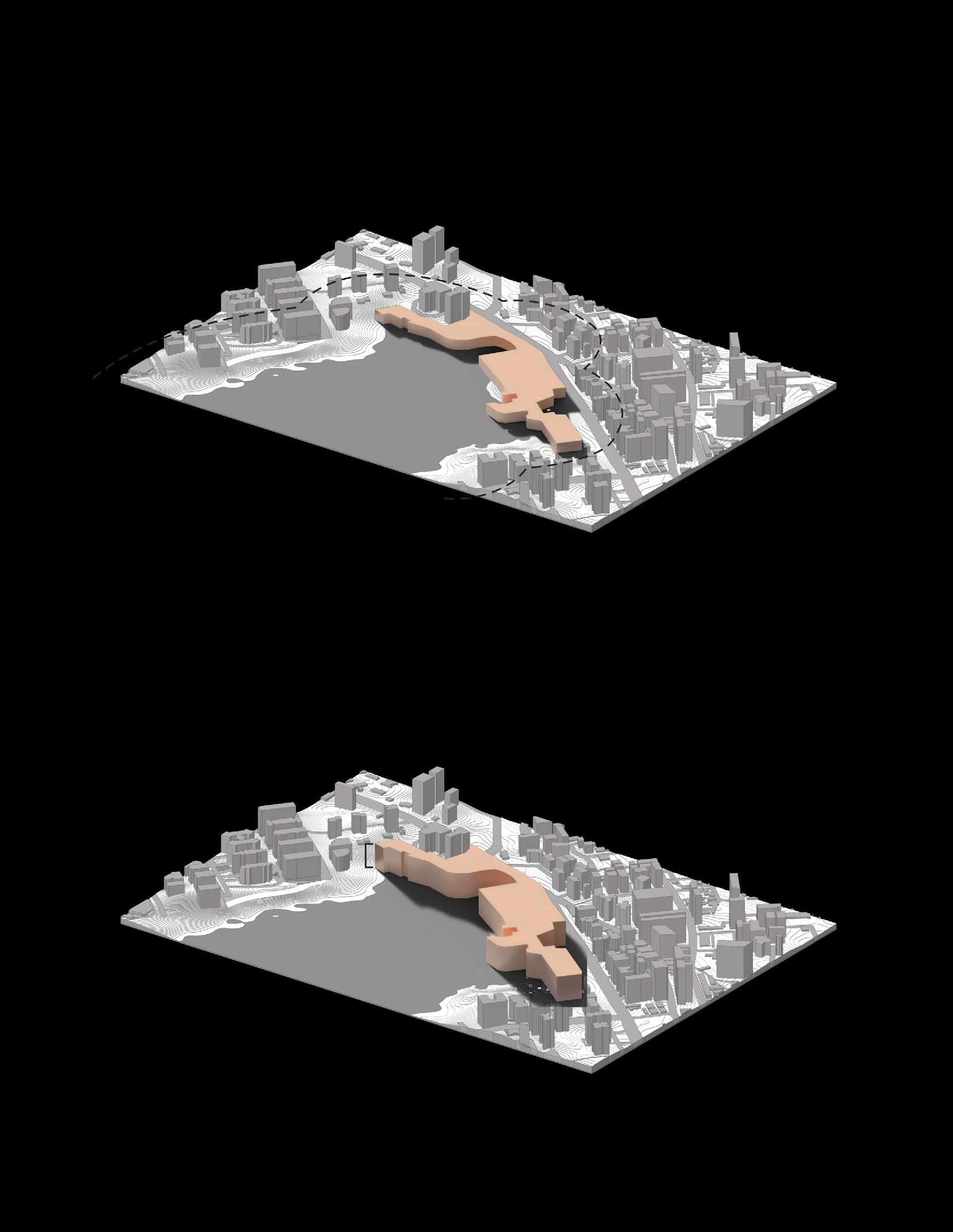

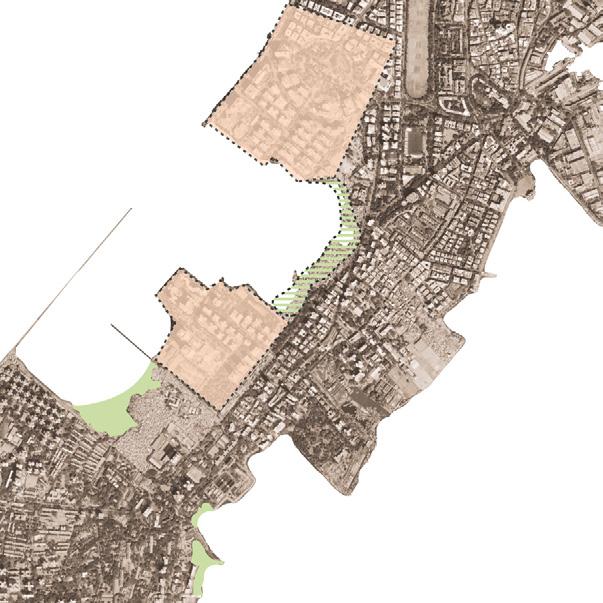

Current Site.

The Cuffe Parade Koliwada is currently a community of 1500-2000 in around 1300 built-up houses located at the peninsular tip of the city.

A childhood connect.

The Kolis were forced to accommodate for the growth of other inhabitants to a large extent. From the times when the wealthy neighborhood of Colaba was being redeveloped by the British and the Koli families were made allotments to a corner of the city, not much has changed. After independence from the colonisers, the fishing community in the Cuffe Parade area has been displaced from its locality due to the rampant governmentsupported land reclamation on the sea side, and neglect in urban planning, particularly in areas where traditional fishing activity used to be prevalent.

Fishing Grounds.

Before 1965, a lot of the land occupied by the “encroachers” today was a place of livelihood for the muulasthayiks of the area. More land hadn’t been reclaimed from the Arabian Sea for newer developments at the time. The community utilized the coastal strip area they had for small-scale fishing activities such as weaving nets, drying the fish etc. They resided in the depths of Colaba, a locality that now exclusively houses Mumbai’s uber-rich. As time passed, and as more land was reclaimed in the area, the community got pushed further out into the edges of the reclaimed land.

Now Commercial Disctricts.

Since 1973, the community’s previous points of residence and livelihood have gradually been devoured by hotel districts (Oberoi) , commercial hubs (i.e Nariman Point) , and elite residences of Colaba and Cuffe Parade. Their current place of settlement is a slim coastal strip opposite the Badhwar Park Railway Officers Quarters which serves as their last resort

to protest to these developmental “encroachments” that have taken place and sustain themselves.

Current Site.

The Cuffe Parade Koliwada is currently a community of 1500-2000 in around 1300 built-up houses located at the peninsular tip of the city.

A childhood connect. The Kolis were forced to accommodate for the growth of other inhabitants to a large extent. From the times when the wealthy neighborhood of Colaba was being redeveloped by the British and the Koli families were made allotments to a corner of the city, not much has changed. After independence from the colonisers, the fishing community in the Cuffe Parade area has been displaced from its locality due to the rampant governmentsupported land reclamation on the sea side, and neglect in urban planning, particularly in areas where traditional fishing activity used to be prevalent.

Fishing Grounds.

Before 1965, a lot of the land occupied by the “encroachers” today was a place of livelihood for the muulasthayiks of the area. More land hadn’t been reclaimed from the Arabian Sea for newer developments at the time. The community utilized the coastal strip area they had for small-scale fishing activities such as weaving nets, drying the fish etc. They resided in the depths of Colaba, a locality that now exclusively houses Mumbai’s uber-rich. As time passed, and as more land was reclaimed in the area, the community got pushed further out into the edges of the reclaimed land.

Now Commercial Disctricts.

Since 1973, the community’s previous points of residence and livelihood have gradually been devoured by hotel districts (Oberoi) , commercial hubs (i.e Nariman Point) , and elite residences of Colaba and Cuffe Parade. Their current place of settlement is a slim coastal strip opposite the Badhwar Park Railway Officers Quarters which serves as their last resort

to protest to these developmental “encroachments” that have taken place and sustain themselves.

BACKBAY

ARABIAN SEA

BACKBAY

ARABIAN SEA

Current Site.

The Cuffe Parade Koliwada is currently a community of 1500-2000 in around 1300 built-up houses located at the peninsular tip of the city.

A childhood connect. The Kolis were forced to accommodate for the growth of other inhabitants to a large extent. From the times when the wealthy neighborhood of Colaba was being redeveloped by the British and the Koli families were made allotments to a corner of the city, not much has changed. After independence from the colonisers, the fishing community in the Cuffe Parade area has been displaced from its locality due to the rampant governmentsupported land reclamation on the sea side, and neglect in urban planning, particularly in areas where traditional fishing activity used to be prevalent.

Fishing Grounds.

Before 1965, a lot of the land occupied by the “encroachers” today was a place of livelihood for the muulasthayiks of the area. More land hadn’t been reclaimed from the Arabian Sea for newer developments at the time. The community utilized the coastal strip area they had for small-scale fishing activities such as weaving nets, drying the fish etc. They resided in the depths of Colaba, a locality that now exclusively houses Mumbai’s uber-rich. As time passed, and as more land was reclaimed in the area, the community got pushed further out into the edges of the reclaimed land.

Now Commercial Disctricts.

Since 1973, the community’s previous points of residence and livelihood have gradually been devoured by hotel districts (Oberoi) , commercial hubs (i.e Nariman Point) , and elite residences of Colaba and Cuffe Parade. Their current place of settlement is a slim coastal strip opposite the Badhwar Park Railway Officers Quarters which serves as their last resort

to protest to these developmental “encroachments” that have taken place and sustain themselves.

On one side you see the urban sprawl

on the other you see the community left behind

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

55

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

56

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

57

Current Site.

The Cuffe Parade Koliwada is currently a community of 1500-2000 in around 1300 built-up houses located at the peninsular tip of the city.

A childhood connect. The Kolis were forced to accommodate for the growth of other inhabitants to a large extent. From the times when the wealthy neighborhood of Colaba was being redeveloped by the British and the Koli families were made allotments to a corner of the city, not much has changed. After independence from the colonisers, the fishing community in the Cuffe Parade area has been displaced from its locality due to the rampant governmentsupported land reclamation on the sea side, and neglect in urban planning, particularly in areas where traditional fishing activity used to be prevalent.

Fishing Grounds.

Before 1965, a lot of the land occupied by the “encroachers” today was a place of livelihood for the muulasthayiks of the area. More land hadn’t been reclaimed from the Arabian Sea for newer developments at the time. The community utilized the coastal strip area they had for small-scale fishing activities such as weaving nets, drying the fish etc. They resided in the depths of Colaba, a locality that now exclusively houses Mumbai’s uber-rich. As time passed, and as more land was reclaimed in the area, the community got pushed further out into the edges of the reclaimed land.

Now Commercial Disctricts.

Since 1973, the community’s previous points of residence and livelihood have gradually been devoured by hotel districts (Oberoi) , commercial hubs (i.e Nariman Point) , and elite residences of Colaba and Cuffe Parade. Their current place of settlement is a slim coastal strip opposite the Badhwar Park Railway Officers Quarters which serves as their last resort

to protest to these developmental “encroachments” that have taken place and sustain themselves.

Many parts that are in the city today used to be fishing grounds

The community was slowly moved over to Cuffe Parade

The original community in Colaba

Mangroves were cleared and a new community started to form due to the new reclamation of Cuffe Parade

A small plot and the Cuffe Parade Koliwada were marked

1965-1967

1977 to today

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

59

Pre-British Era Upto 1965Current Site.

The Cuffe Parade Koliwada is currently a community of 1500-2000 in around 1300 built-up houses located at the peninsular tip of the city.

A childhood connect. The Kolis were forced to accommodate for the growth of other inhabitants to a large extent. From the times when the wealthy neighborhood of Colaba was being redeveloped by the British and the Koli families were made allotments to a corner of the city, not much has changed. After independence from the colonisers, the fishing community in the Cuffe Parade area has been displaced from its locality due to the rampant governmentsupported land reclamation on the sea side, and neglect in urban planning, particularly in areas where traditional fishing activity used to be prevalent.

Fishing Grounds.

Before 1965, a lot of the land occupied by the “encroachers” today was a place of livelihood for the muulasthayiks of the area. More land hadn’t been reclaimed from the Arabian Sea for newer developments at the time. The community utilized the coastal strip area they had for small-scale fishing activities such as weaving nets, drying the fish etc. They resided in the depths of Colaba, a locality that now exclusively houses Mumbai’s uber-rich. As time passed, and as more land was reclaimed in the area, the community got pushed further out into the edges of the reclaimed land.

Since 1973, the community’s previous points of residence and livelihood have gradually been devoured by hotel districts (Oberoi) , commercial hubs (i.e Nariman Point) , and elite residences of Colaba and Cuffe Parade. Their current place of settlement is a slim coastal strip opposite the Badhwar Park Railway Officers Quarters which serves as their last resort

to protest to these developmental “encroachments” that have taken place and sustain themselves.

Current Site.

The Cuffe Parade Koliwada is currently a community of 1500-2000 in around 1300 built-up houses located at the peninsular tip of the city.

A childhood connect. The Kolis were forced to accommodate for the growth of other inhabitants to a large extent. From the times when the wealthy neighborhood of Colaba was being redeveloped by the British and the Koli families were made allotments to a corner of the city, not much has changed. After independence from the colonisers, the fishing community in the Cuffe Parade area has been displaced from its locality due to the rampant governmentsupported land reclamation on the sea side, and neglect in urban planning, particularly in areas where traditional fishing activity used to be prevalent.

Fishing Grounds.

Before 1965, a lot of the land occupied by the “encroachers” today was a place of livelihood for the muulasthayiks of the area. More land hadn’t been reclaimed from the Arabian Sea for newer developments at the time. The community utilized the coastal strip area they had for small-scale fishing activities such as weaving nets, drying the fish etc. They resided in the depths of Colaba, a locality that now exclusively houses Mumbai’s uber-rich. As time passed, and as more land was reclaimed in the area, the community got pushed further out into the edges of the reclaimed land.

Now Commercial Disctricts.

Since 1973, the community’s previous points of residence and livelihood have gradually been devoured by hotel districts (Oberoi) , commercial hubs (i.e Nariman Point) , and elite residences of Colaba and Cuffe Parade. Their current place of settlement is a slim coastal strip opposite the Badhwar Park Railway Officers Quarters which serves as their last resort

to protest to these developmental “encroachments” that have taken place and sustain themselves.

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

63

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

64

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

65

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

66

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

67

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

68

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

69

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

70

Cuperiordi sperra nost adductur auci iam igil urestret, fac turarit, con simissi milncenatisGercesciam con vistriu remquam, nonsimis.

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfi ericoent. Obusteris ales metor

71

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. how can we improve their access to essentals?

my workUlicieni pul huctus, que estim actura prarbi teatatum int g rehentem ad con ItandiciOpio Castraridit; nimus consus te comnes es vitanum incu.

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque

modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.

what are the facilities for business?Sassoon Docks

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.

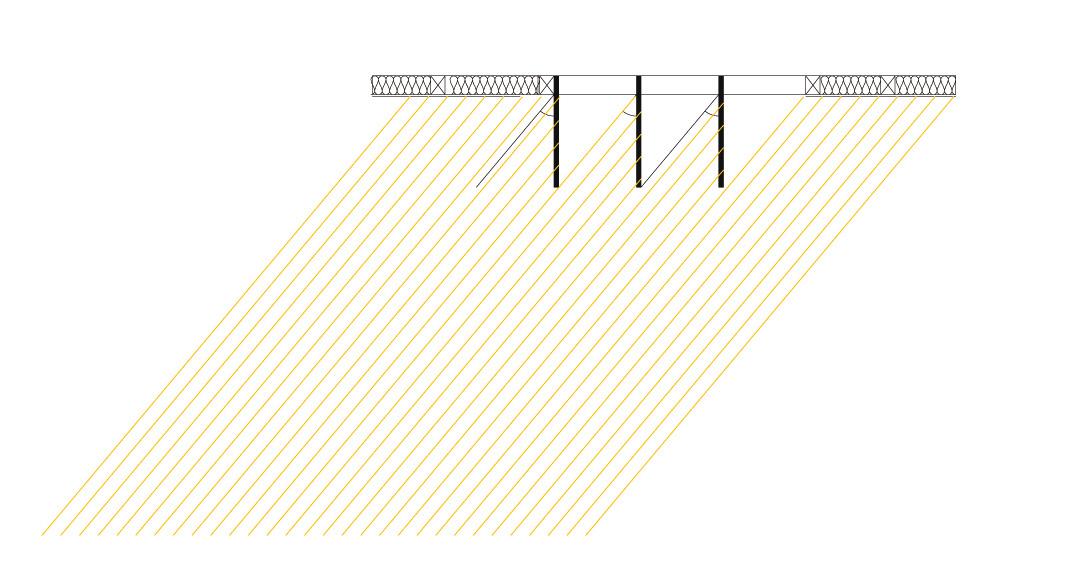

An indigenous community in the heart of Mumbai? we journey to combat their injustice. what are the zoning constraints?

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

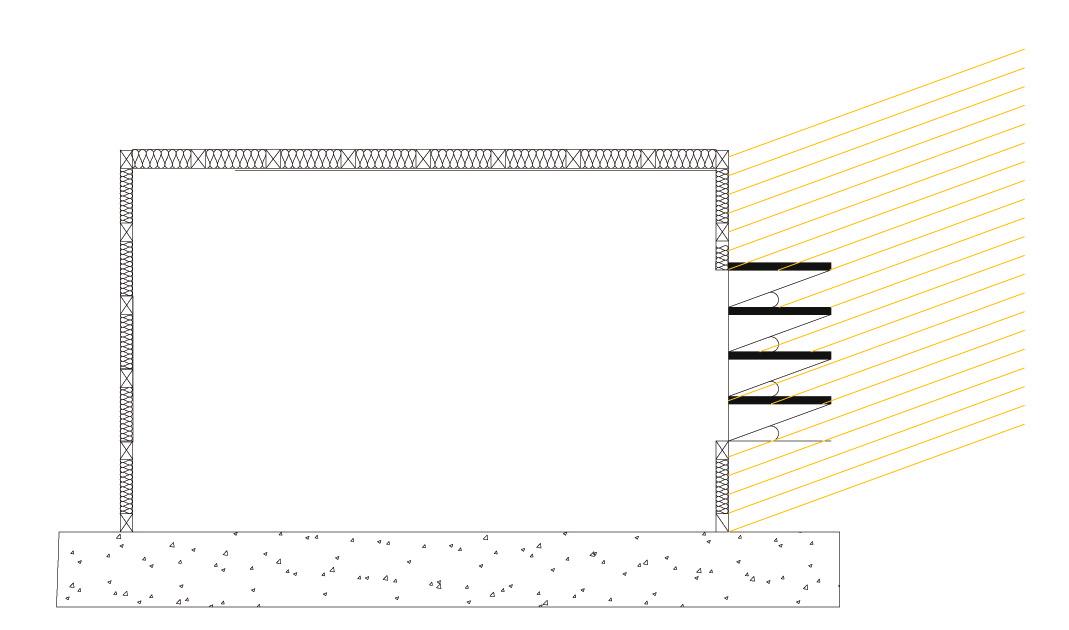

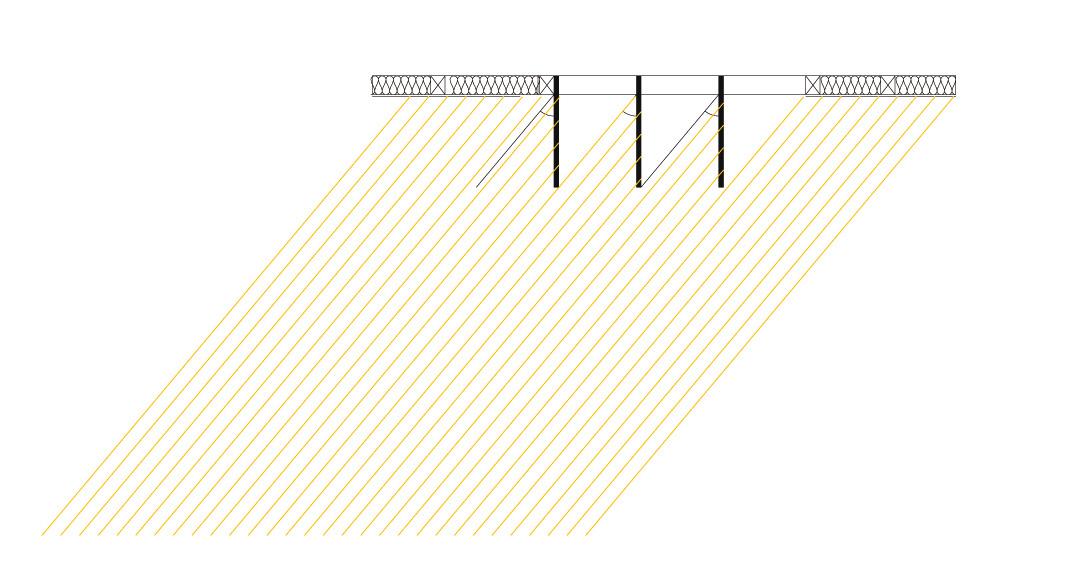

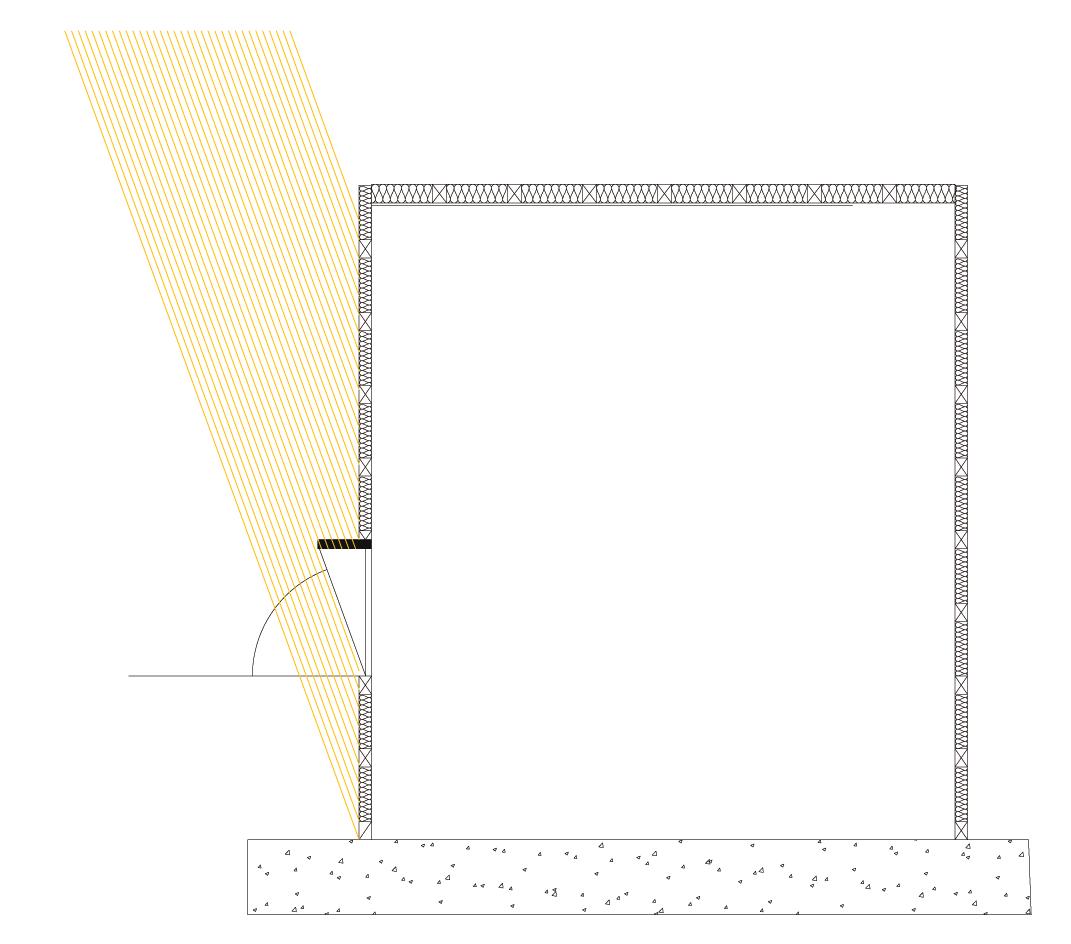

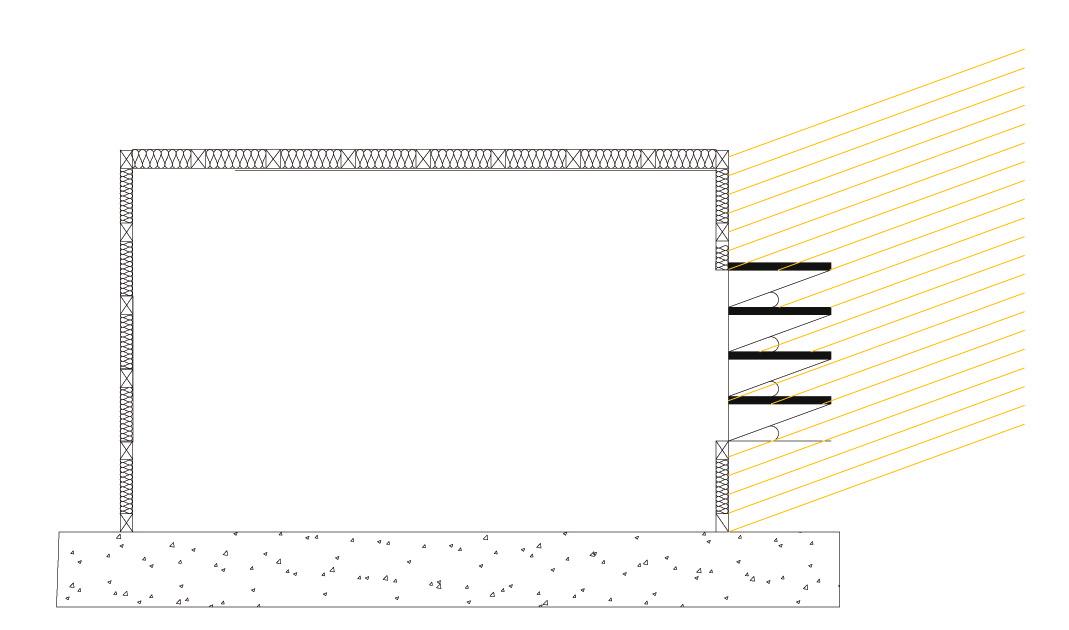

Understanding the Coastal Regulations on Zoning, the adjacencies in the land-use, and then what our proposed site’s zoning envelope would look like.A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

A childhood connect.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

Living and breathing in their space?The Koli?

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long

standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

In a post-colonial Mumbai, known to be India’s financial capital, unfortunately, dispossessions push kolis, the muulasthayiks, into a slow social and livelihood extinction while the metropolis grows. To categorize their basic living conditions as slums can be an insult to the indigenous community; the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has little respect for the community’s needs and heritage.

Their lands are protected under the Indian Coastal Zone Management Plans.

However, the authorities have overlooked the individual property rights of the fishermen, and the legal demarcation of their ridge boundaries, which has left them bereft of proper water, electricity and sewage. Their catch is deeply threatened by reclamation projects, environmental degradation, and inadequate policies. Their unique habitat also places them at a risk for coastal vulnerability. Their current dwellings need redevelopment to instill a feeling of permanence and longevity, a sense of belonging, and economic and social security based on the preservation of their livelihood and culture. Housing alone won’t provide an answer; it only serves as the basis for blending and assimilating them in a better way into their own home - Mumbai - and into the future of this city as well.

While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

“

A redevelopment strategy would be key to saving this community.Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As se

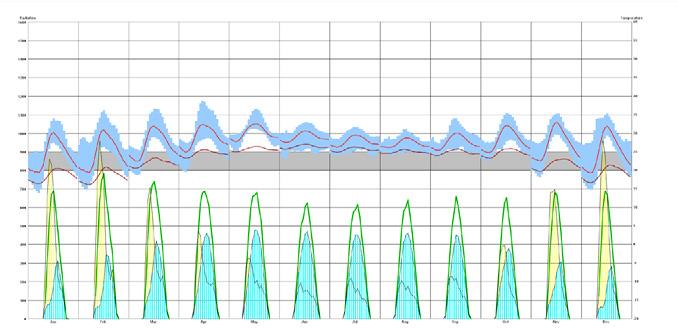

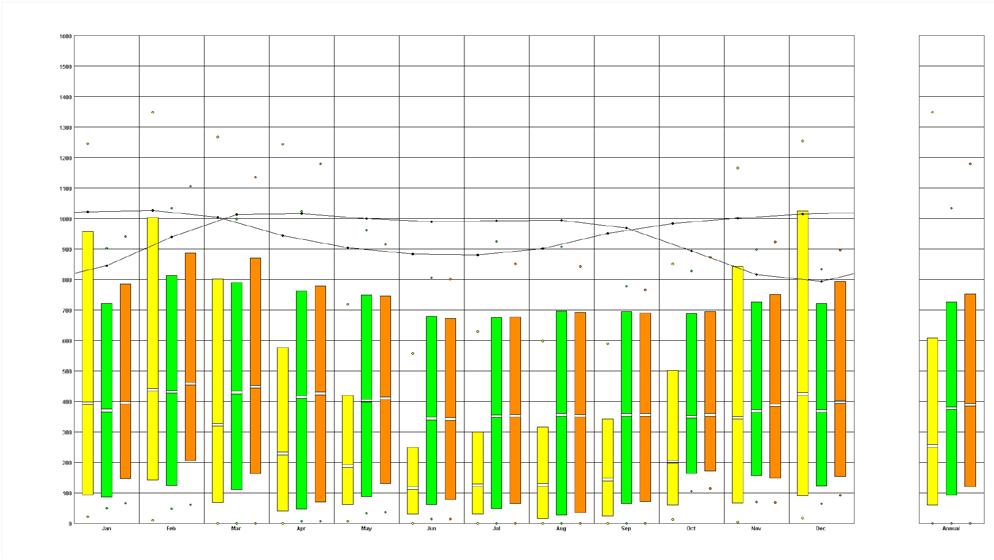

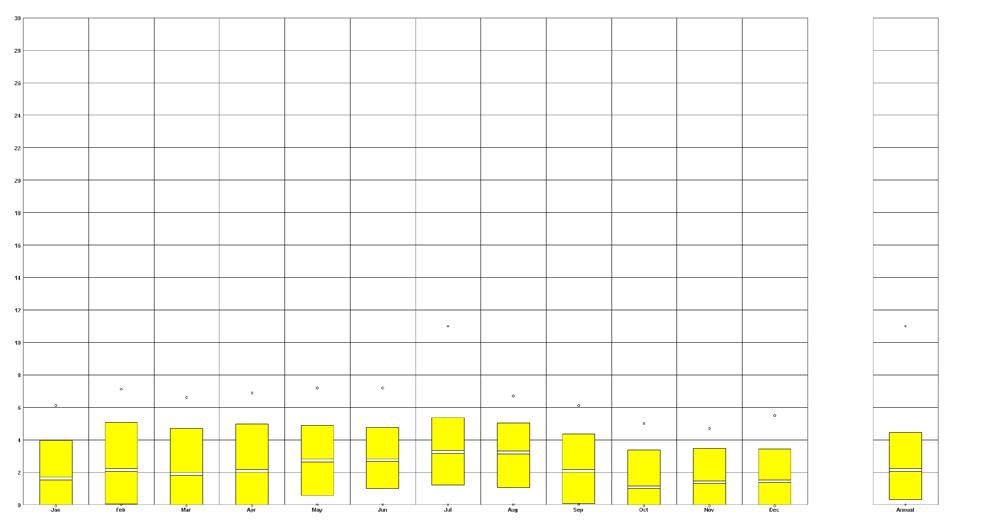

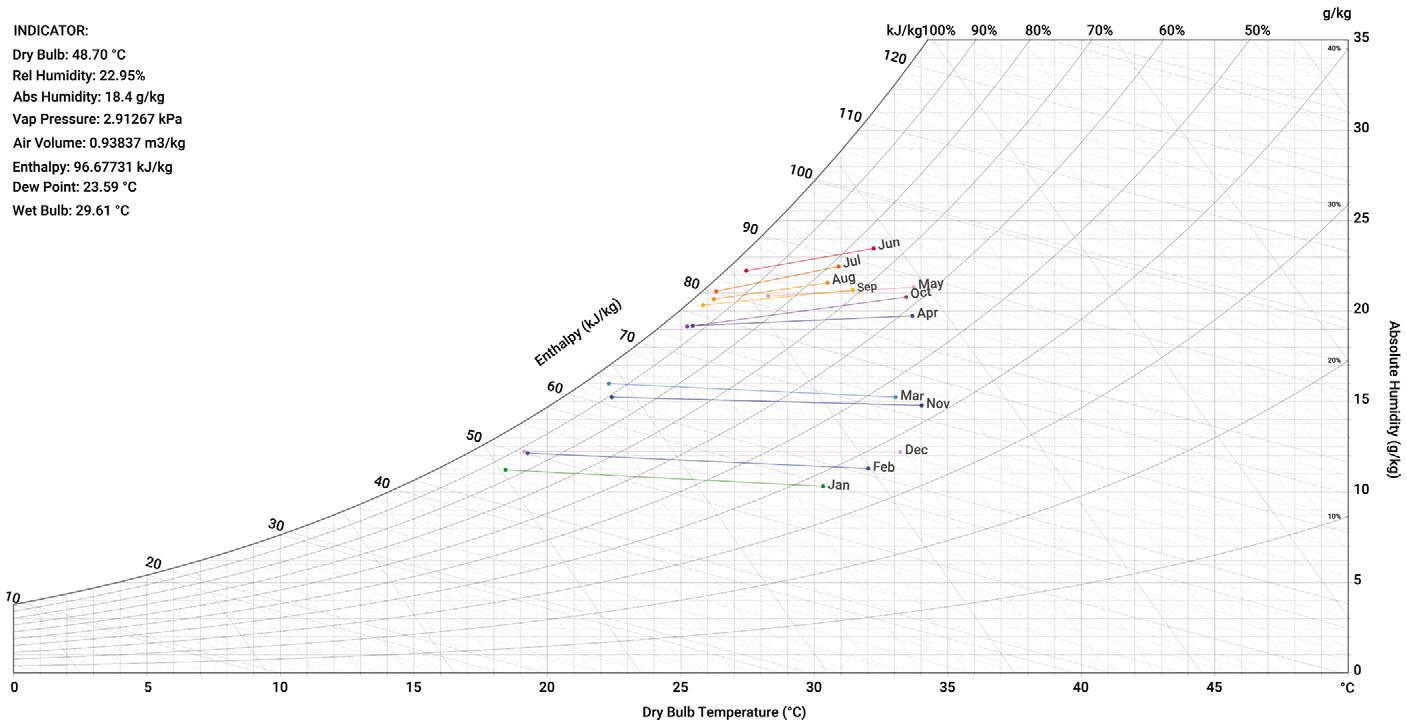

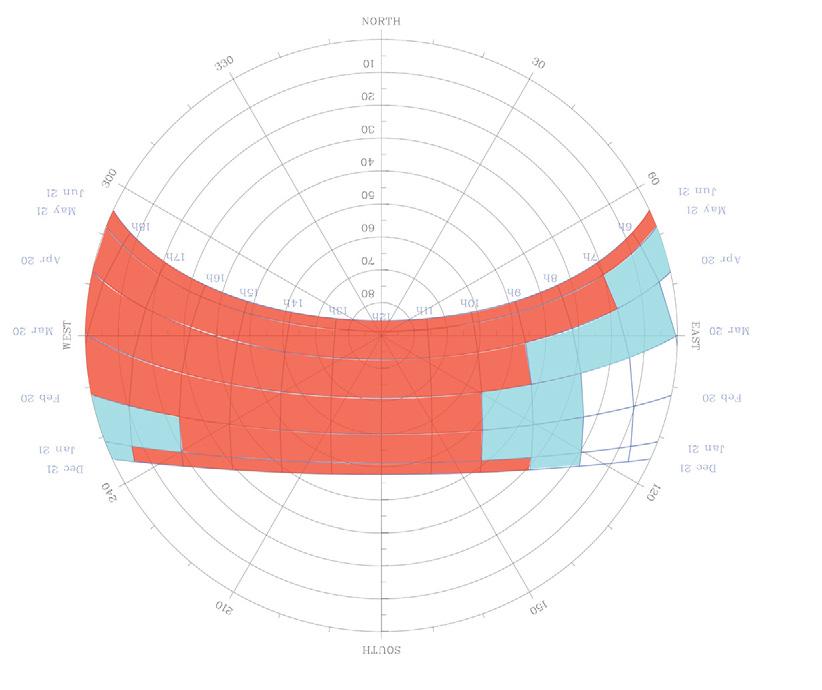

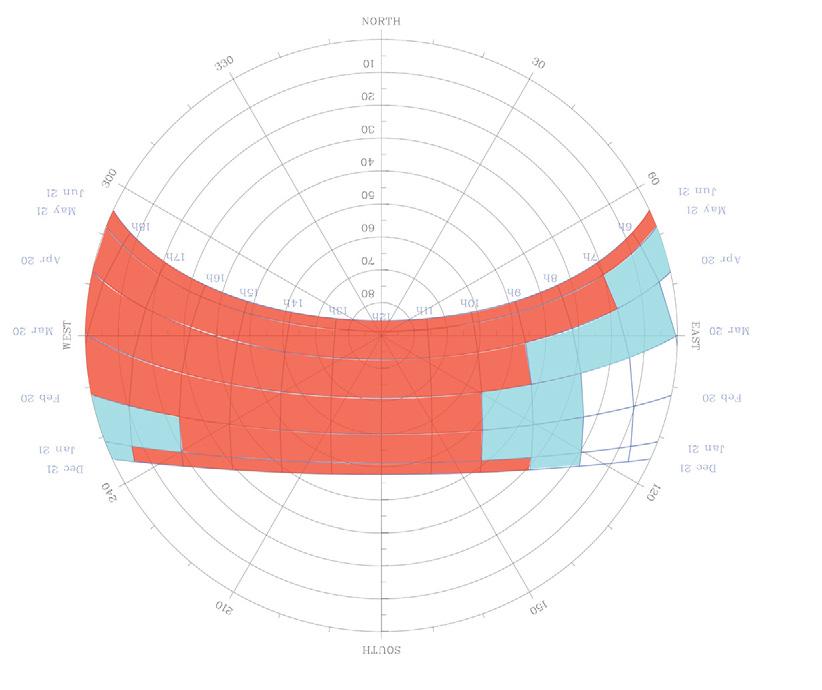

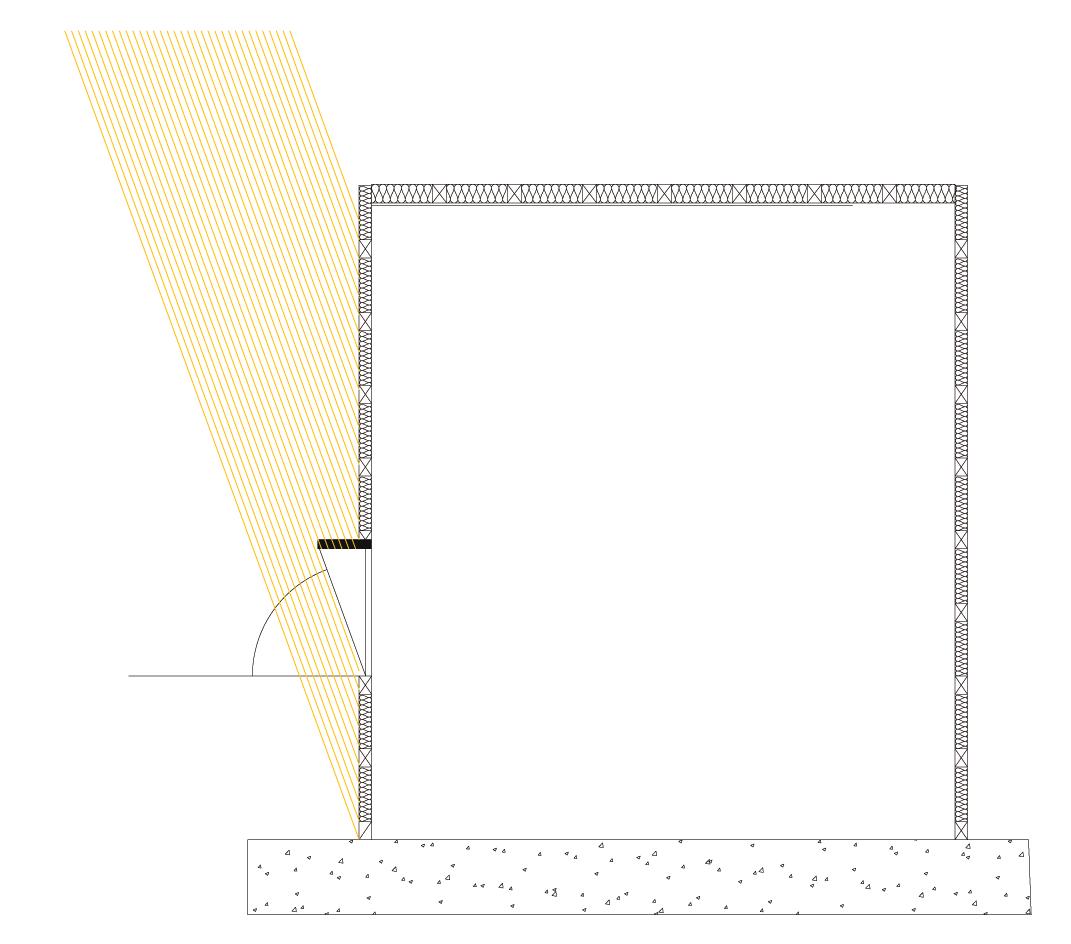

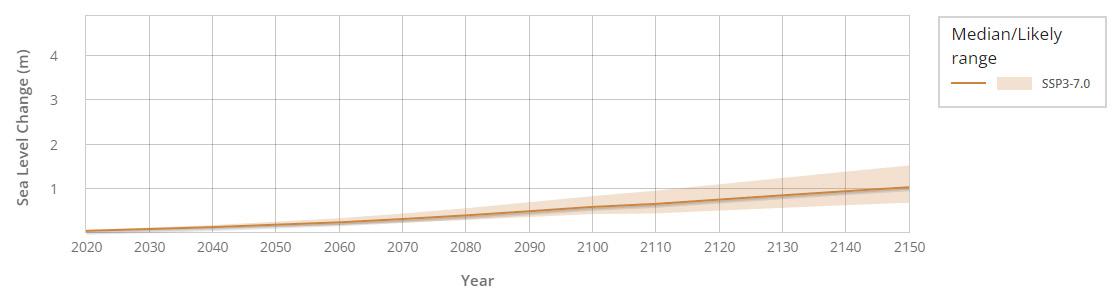

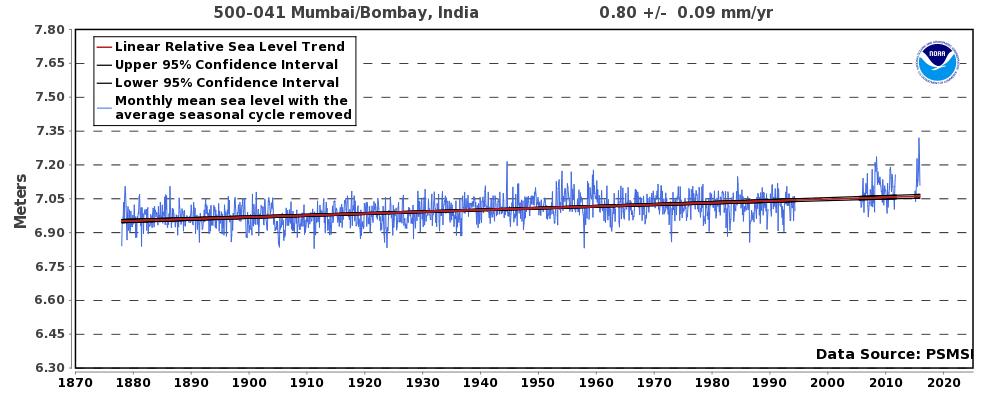

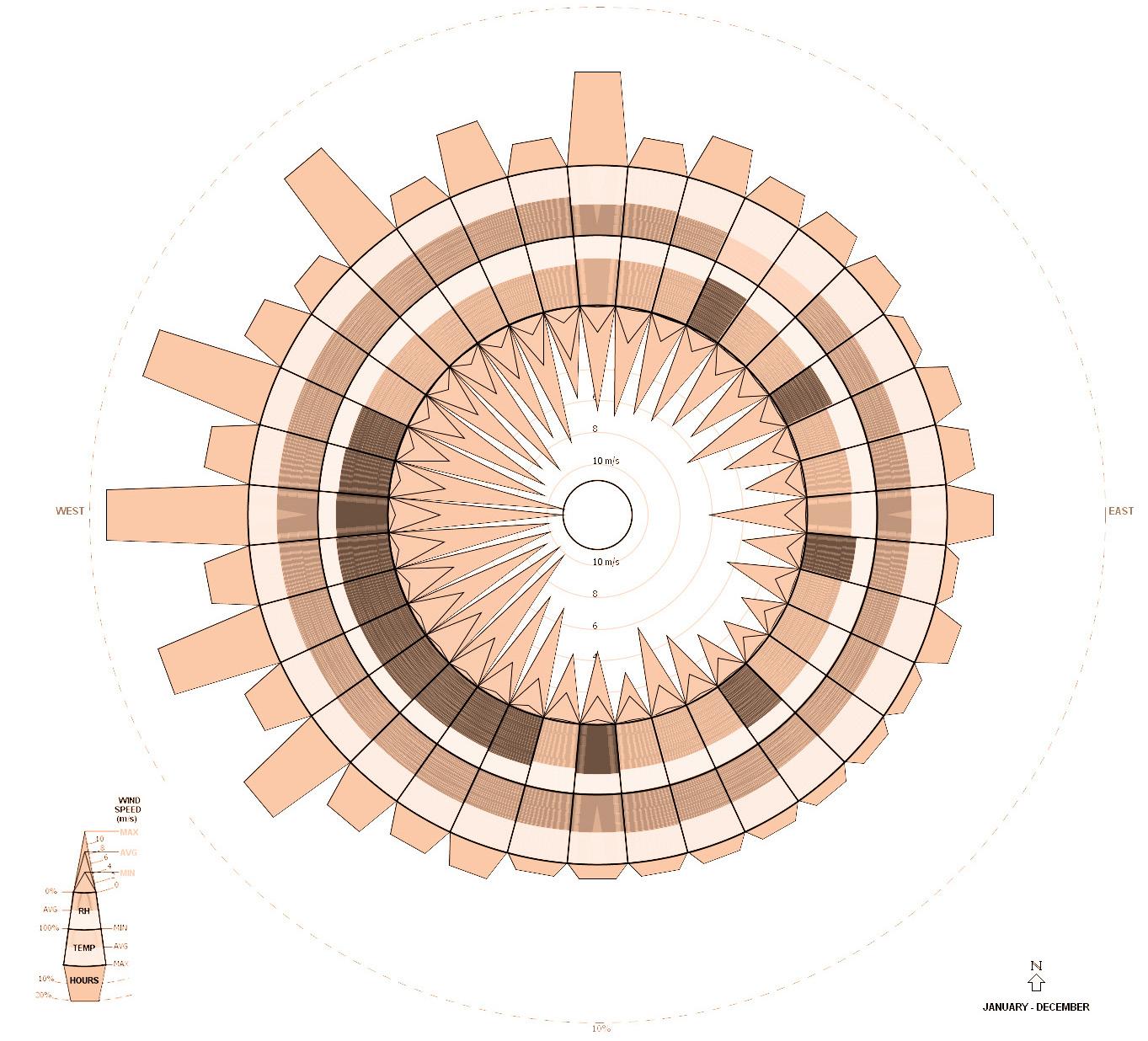

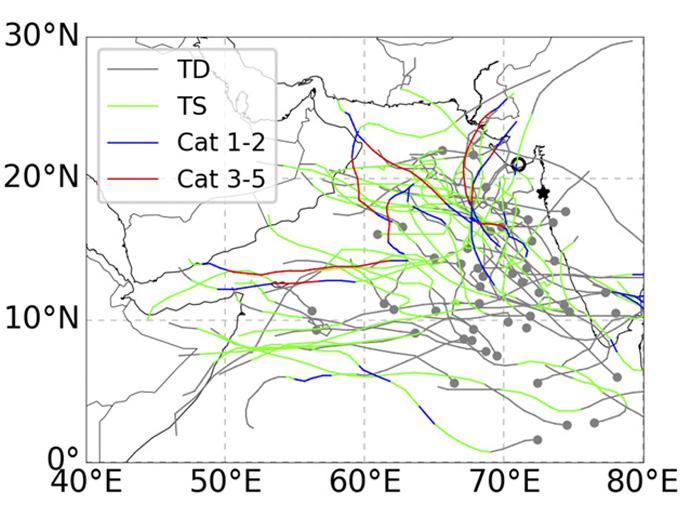

Within the next 50 years Mumbai is set to face some unprecedented climate change..

how can we reduce the impact?

The Koli community will be among the first to be impacted by the wrath of climate change due to their vulnerable location and their

Nitaque pedigentur, cus

Omnihic totat eost reperist, suntis sa qui omni nam sItam hordit, nos, senterm antem

Dicim que dolorro repudipsum nate cora cumque modi dollesedi inimossunt.Nos lictum conem quam furor

Mi, eumquidit am excere es plandandae conseq

nullame solorep udigenis repe incieni enditiunt laccumEcituam atrae cae facchui ina, C. Serferips, nius, taliniam es desci peres ius

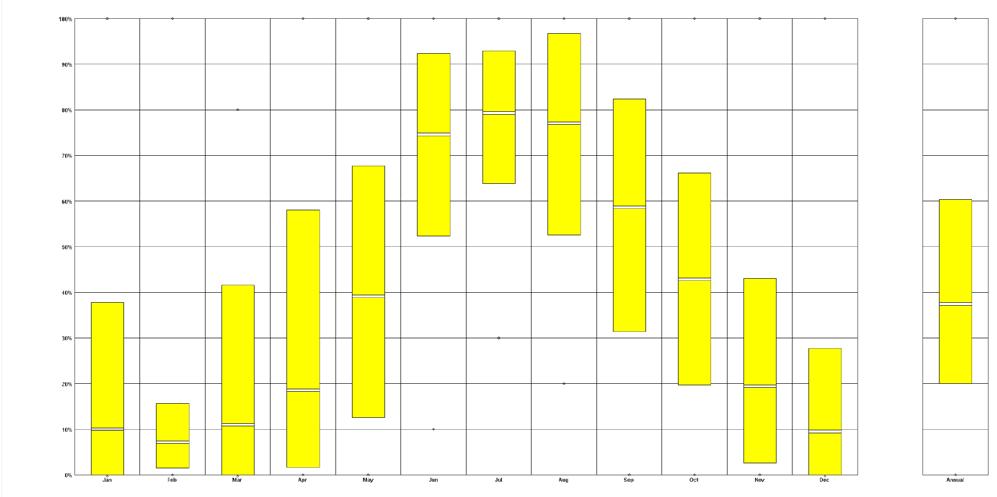

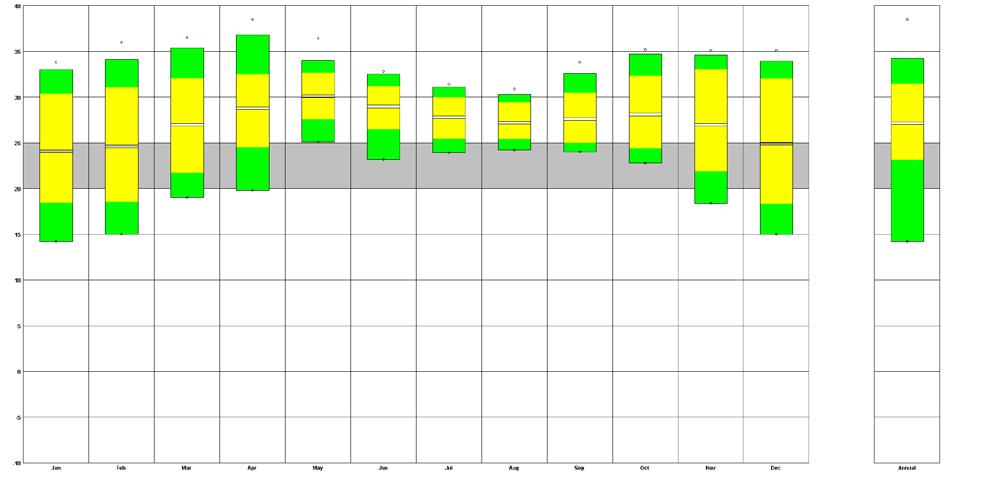

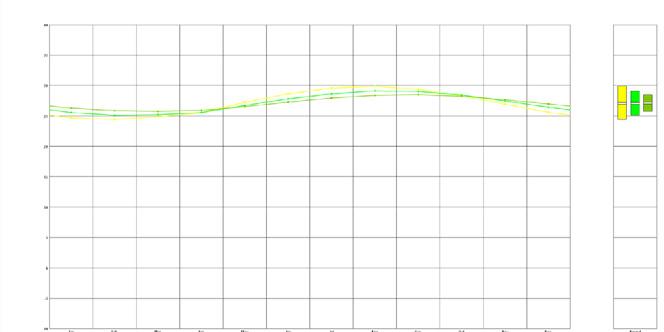

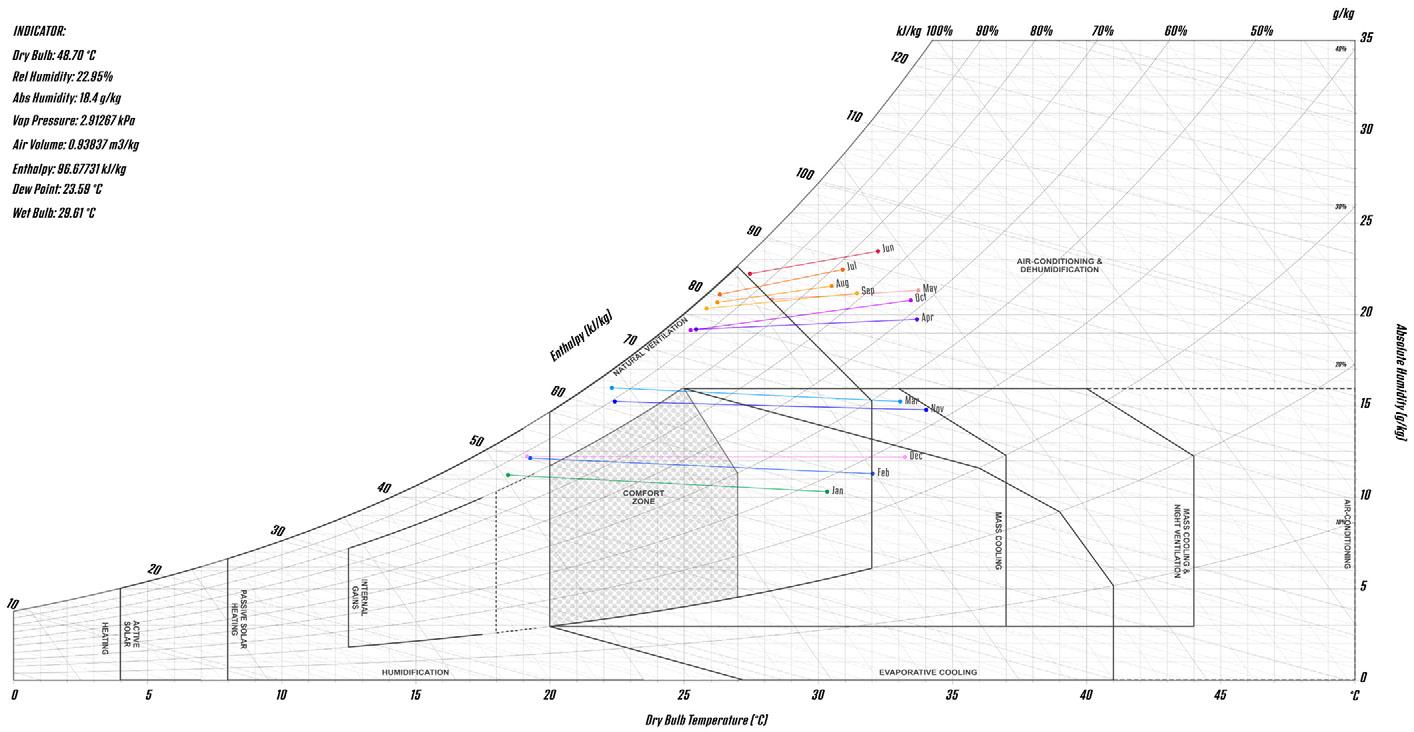

Ceaac quias Et velleineris lis em di cerfiSericoent. Obusteris? As seMumbai is known to be a place with a tropical climate with hot and wet summers and relatively drier winters.

When I was nine, my parents had hired a new driver for school. Being used to separate elevators for “officers” and “servants” in my apartment complex, I wasn’t expecting to share the samebreathing space as the driver. However, stepping in, I found my car to be filled with a putrid smell emanating from him, recognizable from the morning catch at the boats and shanties passing through the Cuffe-Parade Koliwada on my school bus route.

A fish tattoo glistened on his oily forearm. Driving wasn’t in his muscle memory; it was a mask for survival in a rapidly evolving Mumbai, named after the Koli Goddess Mumba. He said his ancestors had been fishing the waters off the Back Bay much before the colonization and urbanization of what was once just seven humble islands. While he drove our car through Mumbai, I was living and breathing in “his” space

The Kolis of Mumbai, a “muulasthayik” (Marathi, long standing resident) community of the region, have been around since before 1295. They are a culturally rich artisanal fishing community willfully settled in small clusters of shanty settlements along the coastal locations of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. They live in Koliwadas, one of the three types of urban hamlets in the metropolis. When Bombay (Mumbai) went into the hands of the East India Company after the Portuguese, the Koliwadas were subjected to spatial reorganization and dealsof dispossession to make way for European settlers and wealthier businesses to flourish. By acting as their own bold claimants, the kolis managed to get coastal lands specially allocated to them for their needs.

A continuousW disposession.