3 minute read

corrosion research fuels growing club

by Emily Slater

One club in the College of Engineering is all about corrosion, and industry professionals couldn’t be happier.

Advertisement

“There are a lot of jobs in corrosion, and companies have a vested interest in making sure materials engineering students at Cal Poly graduate with a knowledge of corrosion,” said Kiran Lochun, president of the college’s Association for Materials Protection and Performance.

Cal Poly’s student chapter is one of the oldest in the worldwide organization, formerly known as the National Association of Corrosion Engineers. Members gather weekly, host experts in the field and undertake research projects, with a healthy budget that’s been bolstered by companies eager for data on corrosion control.

“Nearly all metals and some composites — including reinforced concrete, one of the most widely used materials in the world — undergo corrosion,” said Lochun, a fourth-year materials engineering major, noting companies spend colossal sums on maintenance and repair due to corrosion.

For the club, resources or faculty expertise is not the issue but, rather, the need for more students to pitch — and join — research projects.

“If you have a passion project having to do with corrosion or coatings, come see us,” Lochun said. “We are happy to have you.”

Turning the Ship Around

When Lochun took over as club president, the club had three members including him.

He said most members graduated last year and recruiting was complicated by the fact that the NACE chapter became AMPP after NACE International merged with the Society for Protective Coatings.

Once word started spreading in the MATE Department — and word travels fast in a department where everyone knows your name — students started showing up and pitching their research projects. AMPP now has about two dozen members.

“We were definitely drifting toward the shore, but we are turning the ship around,” Lochun said.

The projects serve as an intermediate step between a MATE lab class and senior project, he added, and they offer students a chance to ask and explore open-ended questions.

“We start with a problem we need to investigate or solve, then research the literature and set up an experiment using MATE knowledge,” Lochun said. “We may not get the results we want on the first try, but as long as we learn from the process, it’s totally fine.

“Then we repeat, repeat, repeat … and hopefully we make a discovery in the end.”

Filling Research Gaps

The club’s three main projects focus on the impact of corrosion on stainless steel, aluminum and titanium, and nickel.

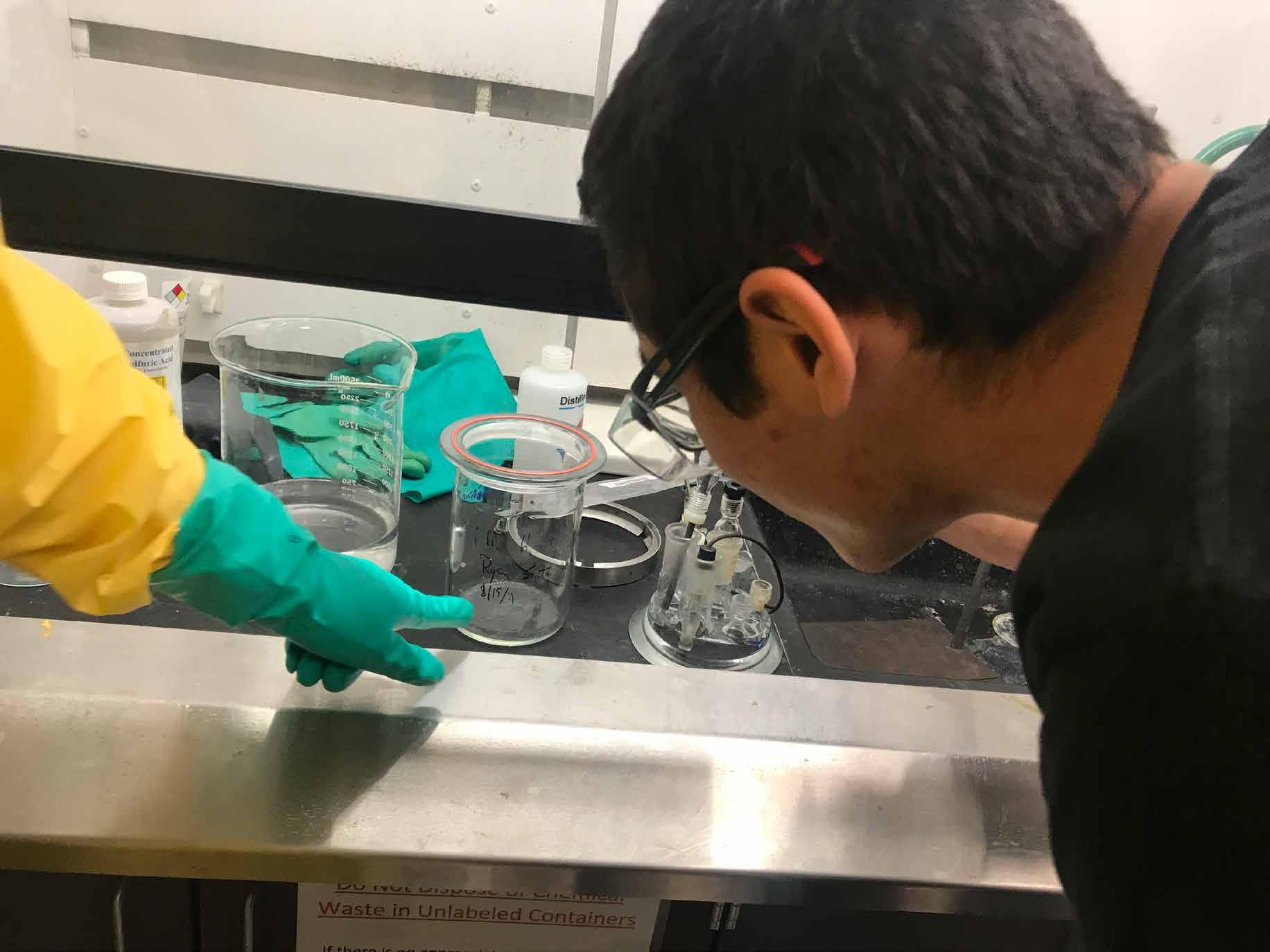

The first project, led by Joshua Venz, a fourth-year teaching assistant, looks at the long-term stress corrosion cracking of stainless steel.

The group of mainly first-year students is immersing the material in acid to watch the interaction.

“Stainless steel is a common material, and we want to see how long it will last without cracking,” said Lochun, who noted corroded steel pipes abound across the country, including one transporting hydrofluoric acid at a Philadelphia refinery that led to an explosion and fire in 2019.

Lochun hopes the team will publish a paper based on their findings as he believes the subject is insufficiently researched.

“There are not a lot of opportunities for MATE students to perform research, and I wanted this club to give space for people to do that work,” he added. “Regardless of what you do in materials engineering, you should have a basic understanding of corrosion.”

The second project, led by third-year student Jacob Reed, is supported by a California-based robotics company that specializes in building remotely operated underwater vehicles. The team of mainly second- and third-year students will test aluminum and titanium — metals used in the robots — in seawater to analyze the long-term effects.

Members hope to run the project over the summer at the Cal Poly Pier after machining a tank for the metals, but data won’t be available until at least six months.

The third endeavor — a passion project of third-year student Marcus Hawley — studies the corrosion of nickel-plated contacts in batteries. Lochun believes the team’s research will fill another gap that could come into play as batteries improve and last longer.

“I was surprised to learn during my education that there are large holes in knowledge that you would expect to be filled but aren’t,” said Lochun, who added AMPP aims to supply just those opportunities.

As Lochun prepares to leave Cal Poly and head for graduate school at Georgia Tech, he’s hopeful for the future of the club. He noted there are plenty of third-year students to keep the projects and momentum going, and he said the addition of Chemistry Professor Erik Sapper as a club adviser could pave the way for more chemistry majors to join.

“It’s been great to see the club grow this year,” said Lochun, adding he’ll check in on the club’s group chat from Georgia. n