Volume 66.1 Fall 2016

tangles of memory the world exhales and superheroes make us feel inadequate

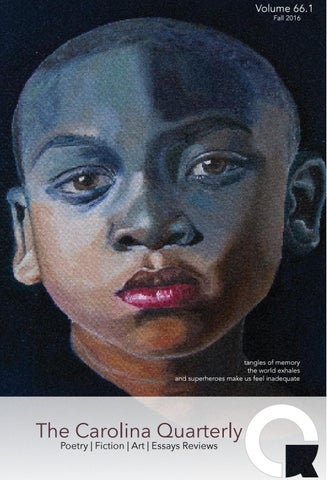

The Carolina Quarterly Poetry | Fiction | Art | Essays Reviews

Volume 66.1 Fall 2016

tangles of memory the world exhales and superheroes make us feel inadequate

The Carolina Quarterly Poetry | Fiction | Art | Essays Reviews