Companion Quarterly

OFFICIAL NewsLetter OF the COmpANION A NIm AL veter INA r IAN s br ANC h OF the NzvA

Volume 34, No. 3 | September 2023

The importance of physical rehabilitation

Giardia infection in dogs and cats

POCUS: ultrasoundguided procedures in cats

Neurological examination and neurolocalisation

Anaesthetic considerations for cardiac patients

E XECut IVE Comm I tt EE 2023 cav@vets.org.nz

President

Natalie Lloyd

Vice President

Becky Murphy

Secretary

Sally Aitken

treasurer

Kevanne McGlade

Committee members

Toni Anns

Shanaka Sarathchandra

Maddie Jardine

Nathan Wong

Head of Veterinary Services

Sally Cory

EDI to RIAL Comm I tt EE

Sarah Fowler (Editor)

Ian Millward

Juliet Matthews

Aurore Scordino

Shanaka Sarathchandra

Liz Foo

Address for submitting copy/ correspondence

Sarah Fowler

66 Callum Brae Drive, Rototuna, Hamilton 3210

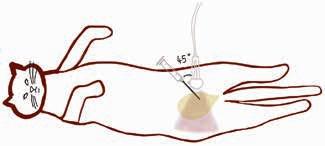

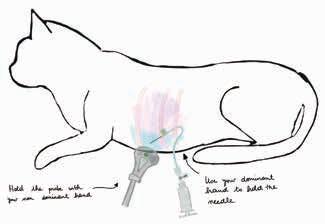

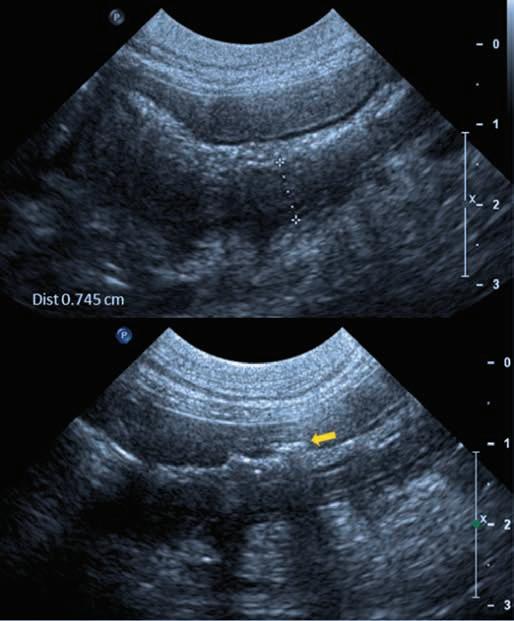

T (H) 07 845 7455 | M 027 358 4674

E sarah.fowler@gmail.com

Advertising manager

Tony Leggett

NZ Farmlife m edia Ltd

Agribusiness Centre

8 Weld St, Feilding

T 027 4746 093

E tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

NZVA website

www.nzva.org.nz

CAV website

www.nzva.org.nz/cav

Copyright

t he whole of the content of the Companion Quarterly is copyright, t he Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA (CAV) and t he New Zealand Veterinary Association (NZVA) Inc.

Cover credit

Genna Ackroyd's Cocker Spaniel t hompson enjoys a day out at the beach

Newsletter design and setting

Penny May

T 021-255-1140

E penfriend1163@gmail.com

Disclaimer

t he Companion Quarterly is a non peer reviewed publication. It is published by the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA (CAV), a branch of the New Zealand Veterinary Association Incorporated (NZVA). t he views expressed in the articles and letters do not necessarily represent those of the editorial committee of the Companion Quarterly, the CAV executive, the NZVA, and neither CAV nor the editor endorses any products or services advertised. CAV is not the source of the information reproduced in this publication and has not independently verified the truth of the information. It does not accept legal responsibility for the truth or accuracy of the information contained herein. Neither CAV nor the editor accepts any liability whatsoever for the contents of this publication or for any consequences that may result from the use of any information contained herein or advice given herein. t he provision is intended to exclude CAV, NZVA, the editor and the staff from all liability whatsoever, including liability for negligence in the publication or reproduction of the materials set out herein.

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 1 CON teN t S 2 Editorial 6 Updates from CAV Executive Committee and NZVA Head of Veterinary Services (CA) 8 CAV Noticeboard 10 News in brief 14 What is your diagnosis? Connor Heap 16 WSAVA Regional Members Meeting Natalie Lloyd 18 Evolution of treatment of FIP in cats – an update Ryan Cattin 20 The importance of physical rehabilitation Nina Field 26 Giardia infection in cats and dogs Natalie Lloyd 34 Point-of-care ultrasound for cats: ultrasound-guided procedures Søren Boysen, Serge Chalhoub, Julie Menard 40 Neurological examination and neurolocalisation in cats and dogs Wen-Jie Yang 44 Cardio Corner: Anaesthetic considerations for the cardiac patient Megan Yeung, Keaton Morgan, Joana Chagas 48 Institute of Health Care Communications Train the Trainer Workshop Meg Irvine 49 Snippets from the NZVA 2023 Centenary Conference 50 ISFM Research Roundup 52 What is your diagnosis? The answers 56 Companion Animals NZ update 58 Healthy Pets NZ update 60 Committee biographies Companion Quarterly Helps you solve personal and work problems, including: Relationship problems Drug and alcohol issues Work issues Change Stress Grief 0508 664 981 24-Hour Freephone Confidential Counselling Service Vets in Stress Programme Volume 34 | No. 3 | September 2023 ISSN No. 2463-753X

20 34 26

Menopause – It’s everyone’s business

This month the NZVA hosted a webinar by Dr linda Dear on menopause. This is a condition that affects at least 50% of veterinarians. There is no doubt that my husband and kids will tell you it directly affected them, so it is likely a much greater number than 50% of us are impacted by this condition. CAV have talked about writing an article on this topic for a while, but with the excellent content provided by linda at her webinar in July, we thought it was a great opportunity to take some notes and share them here with those of you who missed it. Thank you to toni Anns for putting this together.

Natalie lloyd, CAV President

Natalie lloyd, CAV President

Dr Linda Dear, mBBS BA(Hons) RNZCGP mNCP DRCoG, GP, certified menopause practitioner (NAmS) personal fitness trainer, Asthanga yoga teacher and psychology graduate/AC t therapist is highly qualified to inform on menopause! We were very grateful to have her agree to speak at an NZVA Zoom meeting on the 26 July 2023, a talk very well attended by close to 200 attendees. Her talk was engaging, easy to understand, practical and generated multiple questions. Here I share some notes and insights from listening on the night.

menopause in general is neglected. menopause is not just about women; it impacts everyone in some way and by 2030 it is estimated there will be 1.2 billion women experiencing menopause. menopause is inevitable, it affects us both physically and psychologically, and every woman experiences it at some point. It is not always a natural process and can happen with brutality overnight such as during cancer treatment. Whether it occurs naturally or is induced, it is not the same experience for everyone. It happens at different ages, and importantly it is often missed. t he changes associated with menopause can be blamed on other things and the impact that hormones may be having are often not considered. t his can be a

blind spot for GP doctors. At least 75% of women notice symptoms and in 25% of women the symptoms negatively impact their lives.

Definitions

t he formal definition of menopause is the point at which a woman has her final ever period. It is the ending of the fertile years, the loss of ovarian function including both eggs and hormones. Even though ovaries are tiny organs, they have big important jobs, but in menopause they decide to quit.

Perimenopause occurs when the ovaries are starting to shut down. Perimenopause can start in the late 30s and last for 4–8 years. In this stage, periods are still happening, hormones are fluctuating, and pregnancy is still possible. Egg production starts to change from age 35.

menopause is the day when the ovaries officially retire, however this time-point is only defined one whole year after the last period. t he average age of menopause is 51. If early menopause (under 45) occurs, treatment is recommended. For some women, menopausal symptoms can last for 10 years. Everything after menopause is post-menopause.

Signs of menopause

Determining when menopause is occurring is a challenge and GP doctors often find it difficult to diagnose. Perimenopausal periods can be regular or irregular, longer or shorter, heavier or lighter or less or more painful which may add to the confusion. Fatigue, mood changes, insomnia, body pains and headaches are common symptoms. Hot flushes can be particularly troubling and are thought to be due to changes in the hypothalamus. t hey can be embarrassing and distracting and really debilitating. However, 20% of women never have a single hot flush or night sweat.

o varies are more than fertility organs as they make both eggs and hormones (oestrogen, progesterone, and testosterone). o varian hormones conduct a lot of processes in the brain, heart, liver, bones, skin, joints and muscles, nerves, bladder, and vagina. With menopause, women lose the function of their gonads. t his is a huge physiological change and differs from men who don’t generally experience their gonads just falling off one day.

testosterone doesn’t get enough attention in women; it is often considered a male hormone, but in fact women make more testosterone than

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 2 eDI tOR IA l

oestrogen over their reproductive life. testosterone has many roles in the body with the main role being libido. It can affect mood, sleep, cognitive function, cardiovascular health, bone and muscle health and metabolism.

Progesterone prepares the body for pregnancy and supports bone function. Falling levels can affect fertility, menstruation, sleep, anxiety, bone density and headaches. taking micronised progesterone can help keep the uterine lining healthy, improve sleep, improve anxiety, lessen migraine attacks, reduce hot flushes, and may improve blood pressure. However, response may vary: either there is no effect, or you feel amazing, or you hate it.

t here are a multitude of symptoms associated with menopause and it’s often difficult to know if it’s due to hormonal changes or other disease/s, for example heart palpitations can occur due to changing hormone levels. menopause can mimic diseases such as fibromyalgia, depression/anxiety, stress, chronic fatigue, IBS, arthritis, thyroid issues, long CoVID, oSA, ADHD or lymphoma.

Hormone tests

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a simple test to know where you are at? unfortunately, there is no test for perimenopause because you can’t measure ‘a mess’ and we are ‘too complicated to be just a number in our spit!’ Hormone tests are just a snapshot in time and with a wide ‘normal’ range, there is no ‘perfect’ hormone level to measure. t he receptors are where the action is, and we can’t measure at a receptor level.

t he concentration of FSH in blood may be checked in some circumstances, for example in women under 40 whose periods stop, women without a uterus, women not responding to hormone patches, or to rule out causes of other symptoms.

Health risks associated with menopause

After menopause women’s risk of heart attack goes up and there is an increased risk of high blood pressure. ‘Bad’ cholesterol goes up and ‘good’ cholesterol goes down. t he risk of cardiovascular disease is the same as men’s once women reach menopause, and then it increases after menopause.

It is thought that women with more severe flushes may be more at risk of cardiovascular disease. oestrogen helps coordinate the actions of insulin. With menopause comes increased body fat mostly around the abdomen. Cholesterol levels in blood and blood pressure may both increase. menopause increases the risk of osteoporosis and therefore bone fractures.

to counteract these changes in metabolism it is highly advised that women reduce stress levels, get a good sleep, eat well and regularly exercise, particularly strength-building exercise as strength and increased muscle mass increase metabolism.

Managing menopause

t here are lots of treatment choices: hormone replacement therapy (HRt ), supplements, non-HRt medications and herbal remedies. t hey all may have some benefits depending on what is right for each individual woman.

t he aim of HRt (more recently named ‘mHt ’, menopause hormone therapy) is to replace what your ovaries used to do with bio identical hormones. t here are more benefits than risks. Dermal patches are preferred over oral oestrogen supplementation because they have less risk of blood clots. t here is no time limit when taking HRt. HRt will probably not be prescribed for health benefits only; you must have some symptoms to deal with before it will be prescribed.

A study 20 years ago linked HRt and breast cancer. t his was the WHI Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and was a study in older women with older treatments. t he study found an increase of six cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women over the age of 60 taking combined (oestrogen+progesterone) HRt. However, life expectancy was improved overall in women on HRt – in fact there was a reduction in death from any cause. t here is some research on HRt and dementia – it probably helps and it’s good for weak bones.

HRt (mHt ) should be a choice for all women. Don’t compare yourself to other women, everyone is different. Don’t suffer in silence, there is no prize for pushing through. Don’t fear HRt Learn about this life stage – read books, read websites, listen to podcasts.

Diet: menopausal bodies won’t put up with nonsense anymore, so eat a low sugar diet and avoid processed foods that your body doesn’t know what to do with. t he mediterranean diet is very good.

What about brain fog? Lifestyle changes: reduce stress and simplify life, don’t try and do too many things. Find time to meditate – this is powerful, it’s almost as good as sleep. Also, get a good sleep.

What can employers do? Employers can encourage learning and talking. t his is a concept for everyone to understand. Reduce stigmatisation.

Please seek medical advice if you have any questions regarding menopause or treatments, these notes are not intended as medical advice.

Useful websites

https://linkpop.com/menodoctor https://www.menopause.org/ https://www.menopause.org.au/ BVA menopause hub: https://www.bva. co.uk/take-action/good-veterinaryworkplaces/menopause-hub/menopausehub-support-for-you/

Toni Anns, CAV Executive Committee

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 4

WOR k INg tO PROMO te AND SUPPOR t COMPANION ANIMA l PRAC t ICe IN N e W Z e A l AND Activities of the CAV e xecutive Committee

Meeting highlights

t he CAV Committee met on 27 June at the NZVA offices in Wellington. t he Annual General meeting was conducted by Zoom following this meeting at 4.30pm. members of the committee then attended the NZVA Centenary Conference in Wellington 28–30 June and hosted the CAV Dinner on the evening of the 28th where Dr Nicholas Cave was presented with the CAV Service Award for his huge contribution to the profession (see page 10).

t he CAV Committee were also thrilled to see Dr Craig Irving awarded Honorary Life m embership of the NZVA, to a standing ovation, at the NZVA Gala Dinner. t his follows the nomination CAV submitted on behalf of the membership (see page 10). It has been a busy time preparing for these events and awards, with the committee putting in many volunteer hours of work to ensure companion animal veterinarians were recognised and well catered for during the 3 days.

Changes to the e xecutive Committee

At the AGm, the committee welcomed two enthusiastic new members: maddie Jardine and Nathan Wong (for profiles page 11), with Simon Clark and Nina Field stepping down. on behalf of the CAV membership we thank Nina and Simon for their many years of service to the CAV Executive Committee and we wish them well.

Continuing in their roles are: Kevanne mcGlade as treasurer, Sally Aitken as Secretary, and Simon Clark as CAV mAG representative, mAG Chair, and mAG representative on the NZVA Board. Simon Clark has stepped down officially from the committee but will continue to liaise with us as CAV mAG representative until his term as mAG Chair ends January 2024.

Recent activities

topics discussed most recently at CAV Executive Committee level include financial planning and consulting with an independent financial advisor on the best type of investment for the CAV Specified Fund, which has a balance of approximately $600,000. t he NZVA have been investing the specified funds of other SIBs into a Forsyth Barr managed fund, and CAV are investigating the best option for their fund, balancing returns with use promoting members’ interests. t he latter requires availability of at least some of the funds which affects how we invest. For example, a portion of this fund will be needed for the revamp of the Vet Refresher Scheme in the near future.

Sally Cory, NZVA Head of Veterinary Services-Companion Animals, has been introducing the committee to the NZVA’s Policy, Position Statement and technical Notes review system. t he plan is to systematically review these documents over the coming years. t his will require committee members to review and update the documents that members have access to via the NZVA website.

Hans Anderson and trish t horpe have reviewed NZVA’s Best Practice Guidelines, and this was discussed at a recent WSAVA regional meeting (South East Asia) on hospital standards in Bangkok, t hailand in June by CAV President Natalie Lloyd (see page 16).

Vet Refresher Scheme update

t he Vet Refresher Scheme revamp continues, with the NZVA Education team coordinating the work alongside a working group from the CAV committee. Course co-ordinators have been set for some of the courses and meetings with an instructional designer and a platform provider have taken place. t he refresher scheme is essential for supporting veterinarians who have been away from

practice and are looking to enter the workforce again, or those looking to change their area of practice. It is also important for overseas veterinarians to set context for the New Zealand work environment.

Sub-gingival dental procedure update

Following our presentation to the Regulations Review Committee (RRC; https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/ scl/regulations-review/) in June 2022, representatives of CAV, NZVA, and other stakeholders (VCNZ, New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association, Allied Veterinary Professional Council) met with the Animal Welfare team at mPI to draft the new regulation. t he regulation was sent out for public consultation and shared with members via a Survey monkey survey in February– march 2023. t he draft regulation was strongly supported by our membership; feedback that was given to mPI. t he regulation has been passed on to the Associate minister of Agriculture (Animal Welfare), Jo Luxton, and at the time of writing we were waiting on an update as to whether this proposal will be passed on to cabinet prior to Parliament rising on 31 August 2023. CAV have been in touch with both mPI and the RRC (12 July) asking for an update and reiterating the need for urgency on progressing this regulation on behalf of our members.

The CAV Committee

l World Small Animal Veterinary Association

l World Small Animal Veterinary Association – Congress Steering Committee

l World Small Animal Veterinary Association – Hereditary Disease Committee

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 6

continue to represent vets on the following organisations

l Federation of Asian Small Animal Veterinary Association

l New Zealand Companion Animal trust

l Healthy Pets New Zealand

l Companion Animals New Zealand

l National Cat management Strategy Group

l Veterinary Council of New Zealand – Professional Standards Committee

l NZVA Policy Advisory Committee

Health-Focused Breeding Project

During 2023 the committee are working on a Health-Focused Breeding Project providing education for members in areas such as genetic diseases, testing and counselling, the university of Cambridge/Kennel Club Respiratory

Function Grading Scheme and general advice on decision-making when faced with breeding, whelping and neonatal care. Work on this project will start to become available to members later this year and include a dedicated issue of CQ.

Hill’s/CAV educating the educators grant

t he Educating the Educators

Award (sponsored by Hill’s Pet Nutrition and CAV) received four applications for the 2023 award, and at our June committee meeting $8,500 was awarded to the applicants. Further details will be announced once they have formally accepted their awards. CAV thanks Hill’s for their ongoing support of this award.

t he CAV Committee thank members for your continuing support of our special interest branch. We welcome your ideas

and feedback, so please feel free to contact us by email at any stage (cav@ vets.org.nz). NZVA and CAV are asked to represent veterinarians’ views to various stakeholder groups, which provides opportunities to members who may want to participate at a greater level. We welcome your interest and would also encourage you to participate through connecting with your Regional Networks and SIBs. l

NZVA Head of Veterinary Services (Companion Animals) update

Work over the last few months has involved progressing some key projects. Following great survey responses on both after-hours and parents returning to work, data obtained was collated and analysed to identify and prioritise the areas in which the NZVA can focus on in providing resources and guidance for both employers and employees. Data collected was also integral in preparing for sessions delivered on both these topics at last month’s conference. t hese sessions were well received, and some great discussions were generated. t his has provided further direction for this work.

t he NZVA and CAV have provided representation on a rewriting group for the Code of Welfare for Dogs. t his is the first step in the process prior to the code being submitted to NAWAC for review this year.

Another valuable piece of work has been the creation of a canine leptospirosis factsheet which is available to members (https://nzva.org.nz/resource/general/specific/). We are grateful to those who contributed to this document and hope that it provides a clear summary regarding what we currently know about canine leptospirosis in New Zealand.

Sally Cory, HoVS-CA

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 7

The CAV Noticeboard

Companion Quarterly – a call for contributions

Do you have a clinical case to share, need to tick off a task on your CPD plan or want to earn some pocket money?

CQ publishes case studies, clinical updates, reviews etc. on topics that are of interest to companion animal veterinarians. An award of $300 is paid for all published articles, with the chance to win the Best Article of the Issue and Best Article of the Year (thanks to tCI Glenbred).

Please send your contributions to the Editor at sarah.fowler@gmail.com

microsoft Word format is preferred and photographs/images are welcome, preferably 2 megapixels or higher, and sent as a separate attachment (rather than embedded within the Word document).

Healthy Pets NZ Project Grant 2023

Healthy Pets NZ is a charitable trust that acts as the research funding arm for CAV. Funding applications are invited in march and September for research projects that will enhance companion animal health and welfare.

See the Healthy Pets NZ website (www. healthypets.org.nz) to find out how we are

WINNER

Article of the Issue

supporting projects on analgesia for ovariohysterectomy, treatment of squamous cell carcinoma and FIV prevalence. Any queries on how to make an application or donate please email healthypetsnz@gmail.com.

June 2023 | Volume 34(2) | Pp 30–34

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 8

"Rat bait is not always an anticoagulant! Cholecalciferol rat bait poisoning in a dog."

Neil Stuttle

Craig Irving awarded Honorary life Membership of the NZVA

Craig Irving’s career started in 1969 after graduating with a Bachelor of Veterinary Science (BVSc) with Distinction. After graduation, Craig worked in a large animal practice before spending a year as a small animal intern at the university of melbourne animal hospital in Werribee. Craig gained credentials for the Royal Veterinary College Certificate in ophthalmology before travelling to Australia, the uK and the uS to gain experience. After this, he successfully took his Royal Veterinary College examinations. Craig proceeded to develop his ophthalmology practice with the purchase of necessary specialist equipment. t his allowed him to provide an essential and up-to-date service. Inherited eye disease was common, and Craig worked with breed clubs to help eradicate particular conditions by having successful eye clinics around New Zealand. His contribution was immeasurable for the effort and

knowledge he provided at the time, and he had a significant effect on improving canine welfare in New Zealand. Being based in Palmerston North, it was not long before Craig was asked to deliver ophthalmology lectures to students. He was an excellent lecturer who provided extensive notes and had a comprehensive library of slides to illustrate his lectures. most massey university

veterinary graduates have Craig to thank for their knowledge and skills with eye examinations.

A man with a unique style and charm, despite his infamous sense of humour, most veterinarians in New Zealand probably have a Craig story to tell. Craig’s generous sharing of his professional expertise is legendary.

t hroughout Craig’s 54 years of service, he has been a stalwart for the veterinary profession, providing exceptional service to the New Zealand Veterinary Association (NZVA) through dedication to his work, to ophthalmology, to teaching, and to raising the bar with professional standards.

Craig has dedicated his life to veterinary science and has been an active and respected member of the profession, which makes him a worthy recipient of an NZVA Life membership. l

Winner of CAV Service Award for 2023: Nick Cave

t he CAV Service Award is granted to someone who has gone above and beyond in their support of companion animal veterinarians in NZ. t his year’s recipient has worked tirelessly in his role helping to nurture and develop many of New Zealand’s veterinarians. He is internationally well respected and has earned New Zealand recognition on the global stage of companion animal health research. He has been a huge part of the fabric of massey university’s veterinary school where he is incredibly well liked by veterinary students and teaches with a passion.

Nick Cave graduated from massey university in 1991 as part of the class that spawned many academics (Wendi Roe, Janet Paterson-Kane, Susan tomlin, Stefan Smith and Andrew Worth) and private specialists (Andrea Ritmeester, Jenny Donald, Angus Fechney, Alexander macLachlan, Richard mcKee). After graduation Nick left massey for private mixed practice which was followed by a stint in small animal practice working alongside the late Frazer Allan and

todd Halsey in Hamilton. He joined the medicine team at massey’s Veterinary teaching Hospital as a resident under ex-Head-of-Institute Grant Guilford during a very productive period of gastroenterology-based clinical research. He then headed to the university of

California, Davis and completed a second residency and PhD in small animal nutrition before being invited in 2005 to come back to massey to join the medicine department as a Lecturer. on his return to massey Nick established a research programme in small animal immunology and nutrition, and created residency positions which have led to two further specialists in this field. During this time he has been intimately involved with the Feline Nutrition unit and Canine Research Colony at massey. He has been a huge part of the academic life of the BVSc degree at massey and supervised masters and doctoral students. many former students with be able to attest to how Nick enlivened their learning with his passion for teaching. Students always found him to be an entertaining and engaging teacher. A question was never answered with a simple yes/no but became a leap onto the ladder of further understanding of the complexities of veterinary medicine. He is always at his best with an audience, captivating and witty, and a favourite on the CPD circuit as well as with undergraduates.

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 10

Ne WS IN BRI eF

[Photo credit: Mark Coote for the NZVA]

[Photo credit: Nick Cave]

Nick gives his time to support the academic and veterinary community. He is always willing to spend time discussing cases with colleagues and offering valuable advice. During the first Covid lockdown he was on call every evening and weekend for veterinary medicine emergencies. He did this without complaint as a service to the wider companion animal community and to his other colleagues at massey university Veterinary teaching Hospital. He also likes a bit of fun and hosted daily hospital staff zoom meetings during lockdown, instigating the Formal Fridays dress up zoom meetings for staff morale during this time.

Nick has recently resigned from his role as an Associate Professor at massey university and so we are looking forward to hearing

where life will take him next; hopefully he will continue to remain an active part of the veterinary community in New Zealand. to finish, here are some wise words that Nick shared with the graduating class of 2020 in Ihenga, that esteemed record of veterinary life, which we hope will provide an insight into how he has helped to shape the veterinarians of New Zealand in his capacity as a teacher……

“In the painfully stupid film, t he Phantom menace, Senator Palpatine says to Darth maul, ‘You have been well prepared, my young apprentice, they will be no match for you.’ Do you feel well prepared? or do you fear that, like Darth maul, you are about to be cleft in twain by obi Wan Kenobi's light sabre named ‘Lack of Experience’? If our

experiences with you in the clinic since lockdown are anything to go by, you are still pretty extraordinary. Perhaps it is testament to the work you put in during lockdown, or to what is still fundamentally a really good curriculum taught by people that care, or it is due to the value of the condensed experiences concocted for you at the end of the year, where lymph node aspirates on a dog become an exercise the whole family can enjoy. or perhaps, just perhaps, it is that old chestnut, that ultimately, you are all rather special human beings, whom many of us feel privileged to teach.”

(with thanks to Natalie Lloyd, Susan tomlin and Andrew Worth) l

Welcome to the new members of the CAV executive committee

Simon Clark and Nina Field have recently resigned from their positions on the CAV Executive Committee and we thank them for their efforts and input. Following the AGm in June, their places were taken up by two fresh faces, Nathan Wong and maddie Jardine. Below Nathan and maddie introduce themselves:

Auckland with my fiancé and three cats; Jeffrey, Jellybean and Juniper.

Maddie Jardine

Expressing feline anal gland contents into my face on a Friday evening during my first year of work was a life-changing experience. t he caustic sensation on my mucous membranes was unforgettable, and the indifference expressed by the owner of said felid left me yearning to understand how clients perceive us, our efforts, and our advice.

Nathan Wong

I am a 2014 massey university graduate and started out working in general practice for the first 6 years of my career. I've since transitioned to working at the SPCA (plus the occasional moonlight shift at afterhours clinics) and loving the different and rewarding nature of shelter medicine. I'm passionate about animal welfare and making the veterinary profession more sustainable for us all. I currently reside in

After almost nine years of clinical practise, I craved that thrill. Enter: CAV AGm 2022. I gently accosted the attendees about my frustrations surrounding the remuneration of support staff in our industry, and found a strong sense of shared frustration, and empathy. my hope is that by being a part of this committee, I can be a part of the growth this industry needs to embrace, and lend my voice and enthusiasm to such causes. I have a passion for communication, and I think it’s vital that we strive for better communication with ourselves, between ourselves, and between our industry and the public. I graduated from massey and have worked in various places around NZ and uK, including a stint as a teaching associate at Bristol Veterinary School. I work at Aldwins Road Vet Clinic in Christchurch and relish our team. I advocate for diversity, equity and environmental sustainability in our profession and am also a member of the NZVA Climate Champions crew. In semester two of 2023 I will be studying with te Wānanga o Raukawa towards Poupou Huia te Reo 2. l

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 11

[Photo courtesy N. Wong]

[Photo courtesy M. Jardine]

WSAVA news: launch of Certificate in Pain Management

t he World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) is to launch a Certificate in Pain management, supported by Zoetis. t he WSAVA Certificate in Pain management is based on the updated Global Guidelines for the Recognition, Assessment and treatment of Pain, unveiled by the WSAVA Global Pain Council (GPC) at the end of 2022. Despite rapid advances in pain management, the GPC is concerned that pain in companion animals is underdiagnosed and under-treated.

In offering this new certificate in conjunction with its Global Pain management Guidelines, the GPC aims to raise awareness of the importance of pain management for patient health and welfare and provide practical help

to veterinary professionals who wish to refresh or deepen their knowledge in this area.

Globally relevant and available online for ease of access, the WSAVA Certificate course comprises three modules, with tailored content for veterinarians and veterinary nurses/technicians, covering:

l understanding and assessing pain

l Preventing and treating pain

l Pain management in practice

Each module contains recorded lectures from members of the GPC and other global experts, together with links to mandatory and suggested reading materials. Quizzes are included at the end of each lecture. t he course is available free of charge to all companion

animal veterinarians and veterinary nurses/technicians.

t he WSAVA Certificate in Pain management is available in English and is being submitted for RACE accreditation. Interest in the Certificate can be registered here: https://wsava.org/pain-certificate/

t he WSAVA’s Global Guidelines for the Recognition, Assessment and treatment of Pain are available for free download from the WSAVA website in a range of languages. t he work of the Global Pain Council is generously supported by Zoetis. l

Would you like to see your pet on the cover of Companion Quarterly?

We now have a new cover photo for each issue of Companion Quarterly. This means we are always on the lookout for suitable photos. Photos selected for the cover must be landscape orientation (or able to be cropped to this), crisp and well focused, and of high resolution (at least 300 DPI). They must also be well composed and interesting.

Please send any suitable images to the Editor (sarah.fowler@gmail.com). If however you have a favourite snap of your furfamily that’s not quite up to cover standards, please send that in too: photos that are not selected for the cover may be used elsewhere within the magazine..

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 12

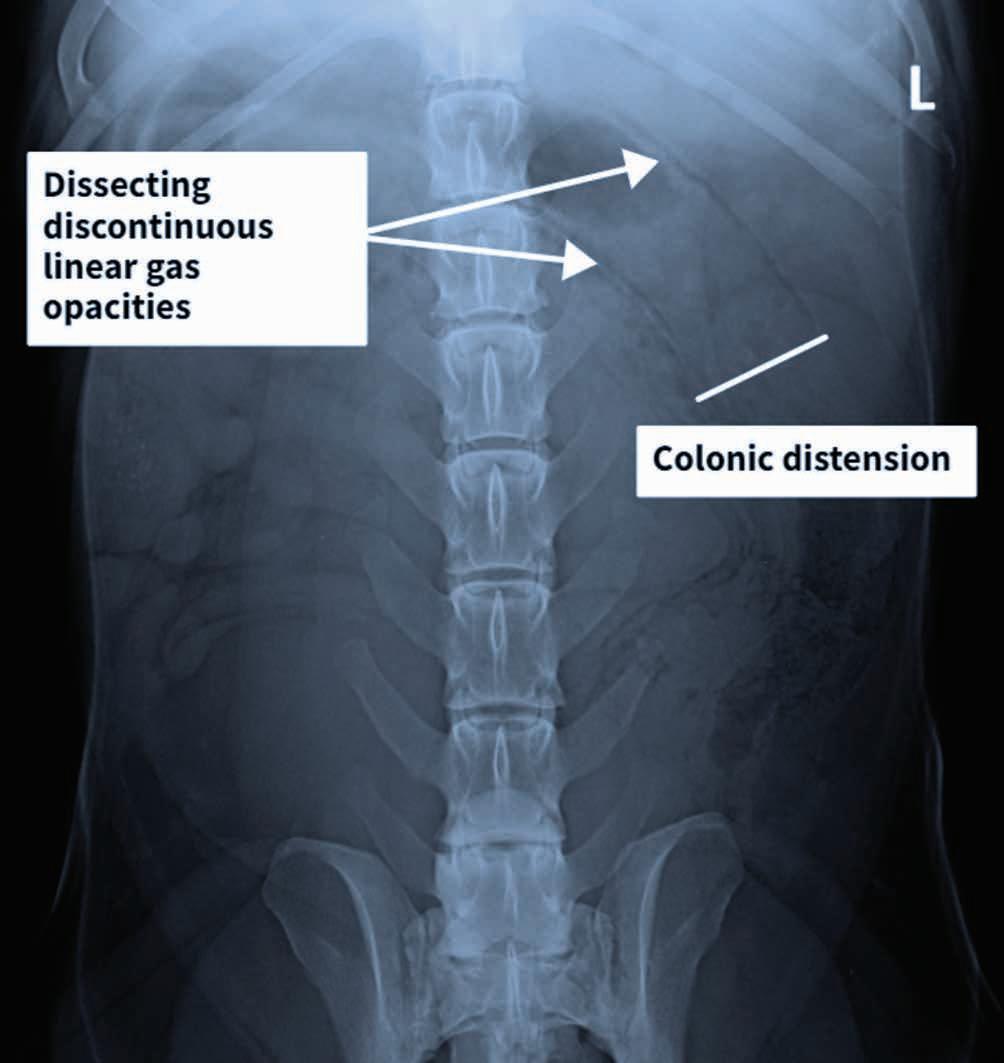

What is your diagnosis?

t He QU eSt IONS…

CONNOR He AP, BVSc, 2023 Zoetis Intern, Veterinary Specialists Auckland

Case history:

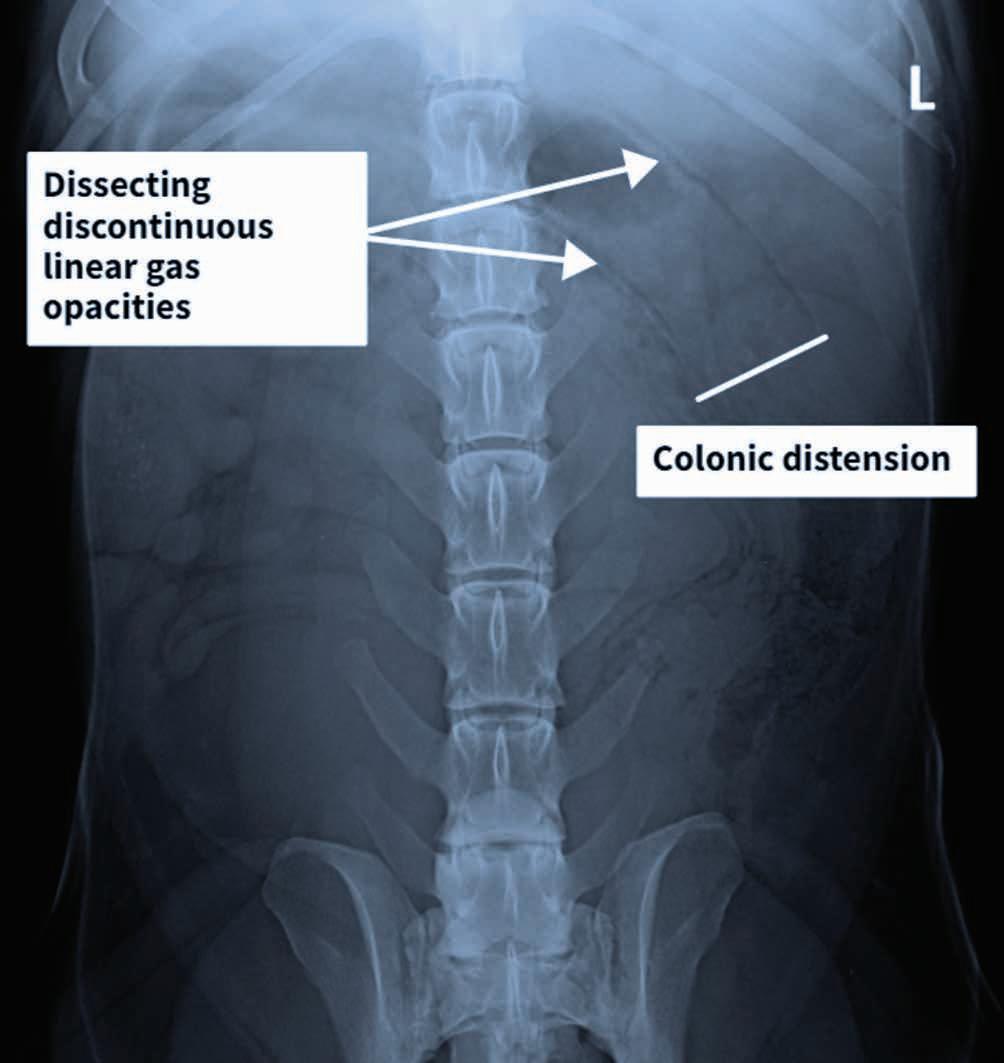

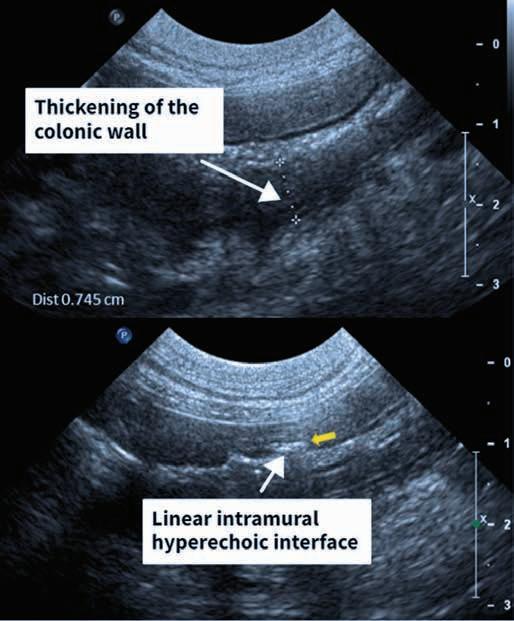

A 3-year-old, male neutered Labrador Retriever presented for chronic diarrhoea. t he patient had a history of inflammatory bowel disease and had undergone multiple previous surgeries for foreign body removal. A colopexy had also been previously performed. t he patient had completed a course of metronidazole on the day of presentation and was also receiving vitamin B12, psyllium husk (metamucil) and probiotics. He was up to date with de-worming treatment and core vaccinations. A three-view abdominal radiograph series was taken as part of the diagnostic workup, and two cropped projections are provided below (Figure 1).

Questions

1. What are your radiographic findings?

2. What are your radiographic differentials?

3. What would be your next steps?

Answers on page 52

Contact: connor.heap@vsnz.co.nz

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 14

Figure 1. l eft lateral (a) and ventrodorsal (b) abdonimal radiographics of a dog with chronic diarrhoea.

a b

CAV UPDAte

WSAVA Regional Members Meeting

NAtA l I e l l Oy D, CAV president

Background

t he WSAVA represents a global veterinary community of over 125 countries. During a guided interview on Needs and Capacity Assessment carried out in 2019, the top guidelines project determined from our membership worldwide was Animal Hospital Standards/Veterinary Practice Management to create guidelines that can be relevant to our global community a more in-depth discussion to understand challenges, obstacles and opportunities and input needed to be collated from our membership. It was therefore the proposed topic for the Asia Regional members’ Forum that I attended earlier this year in Bangkok. t his event was hosted by the Veterinary Practitioners Association of t hailand (VPAt ) Regional Veterinary Congress.

Purpose

l to identify needs and obstacles/challenges for animal hospital/veterinary practice standards

l to find out the vision that WSAVA membership has for a guidelines framework

l Exchange information on standards and accreditation process currently used worldwide and within each country

June 12–14 2023 Bangkok, Thailand Programme

l Collate information and resources for a potential guidelines working group

Attendees

l WSAVA Executive Board representatives including the current WSAVA President, Vice President, Immediate Past President and Executive Board members.

l Representatives from countries with a scheme for animal hospital standards already in place (New Zealand, Australia, united States, t hailand)

l Representatives from WSAVA member associations and or local organisations (including but not limited to Singapore, Philippines, China, India, malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia).

Contact: CAV@vets.org.nz

Morning session – All member representatives were asked to invite members who were present at the VPAt Regional Veterinary Congress to attend this session and contribute to the discussions. t he session started with presentations from organisations currently running animal hospital standards schemes (i.e. AAHA (united States), ASAV (Australia) and tAHSA ( t hailand)) followed by sharing from other countries. t he ensuing discussion part was a very vibrant and open session that allowed concepts and concerns to be included in the afternoon members’ forum.

Afternoon session – member’s Forum was open only to WSAVA member representatives. t he session was facilitated by Dr. t hitirat Chaimee (Zoetis t hailand)

Discussion

t he afternoon session was a workshop style session covering a range of topics which have been summarised into the main points below.

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 16

[Photo courtesty of the author]

Benefits of developing guidelines:

l Establishing benchmarks for high quality practice

l Better animal welfare

l Improve standards of care

l Improve working environment

l Enhancement of workplace health and safety conditions

l motivates and empowers the entire veterinary team

l Financial benefit

Identification of groups or individuals who benefit from the development of guidelines

l Veterinarians

l Pets and pet caregivers

l Associations

l Government

l Improves social status of vets

l General public

Obstacles to the development of guidelines were identified as being

l money, financial investment

l Awareness, acceptance, opinion, mindset

l Human resource and time

l Assessor objectivity, transparency, governance

l Government, though this factor was determined to not be within the scope of our influence

t he session concluded with a discussion of what members felt was WSAVA’s role in the development of these guidelines or standards.

Broadly, it was decided that WSAVA should look to initiate the development of a set of minimum clinical standards. It may be that many of these standards already exist in the form of current WSAVA guidelines. WSAVA may also be able to provide a central repository for storage of this information for member associations.

t he broad and variable range of requirements identified across different organisations means that WSAVA are more likely to develop a set of minimal clinical standards rather than guidelines as such. t hese standards may well then serve as a platform for each country to base their own scheme upon.

The New Zealand perspective

I found this a very valuable conversation to be part of. New Zealand is ahead of many countries with respects to having a well-established set of hospital guidelines (Best Practice) in place. Recently the Best Practice team have completed a thorough review of the guidelines, and a personal review of these was part of my preparation for this meeting. I was interested to note that New Zealand and Australia have a similar number of practices accredited (approximately 80–90) despite a marked difference in number of clinics in each country.

t here are some notable differences in the structure and verification component of the schemes between the countries. For example, New Zealand has quite a unique approach

to verification and assessment of practices, and Australia has a unique case based assessment component. As far as I am aware, from the countries that were present at the meeting, New Zealand is the only country to have a wellbeing component built into their scheme.

these differences provide learning opportunities for those who currently have schemes to refine and improve, as well as providing insight to those countries looking to set something up.

t here does seem to be a trend that in countries where the standard of practice is reasonably high, uptake for the schemes has plateaued. on the other hand, in countries where the service being provided by veterinarians is markedly variable, there was a strong demand for standards or guidelines. t he activity of the local regulator (and indeed whether there even is a regulator in a country) plays a significant role in this.

However, the immense benefits of hospital or clinical standards for the whole veterinary team were widely agreed upon, and ongoing development and support of some type of standards in any country was something that the group wholly supported.

Where to from here?

A taskforce was put together which New Zealand will be part of to further discuss the outcomes of the workshop. t his group will meet again in Lisbon at the WSAVA Annual Congress in September 2023. one of the first topics that the taskforce will look to develop will be to understand if the need for these standards is limited to members in South East Asia, or whether this is something required by the wider WSAVA membership.

I look forward to updating members on my return from this meeting. l

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 17

[Photo courtesty of the author]

Cl INICA l UPDAte evolution of treatment of FIP in cats – an update

RyAN CAtt IN, BVSc (dist) MANZCVS FANZCVS

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a common infectious disease of cats. t his disease occurs when the feline enteric coronavirus acquires a mutation which allows multiplication within macrophages. Historically the marked inflammatory response that ensues was a life-ending disease.

Fortunately, there are now two nucleoside analogues available for cats in New Zealand that appear highly effective, Remdesivir and molnupiravir. Nucleoside analogues are similar molecules to the ‘true’ nucleosides that are the building blocks of DNA and RNA. Because of their structural similarities, they interfere with key enzymes in DNA or RNA replication, or are integrated into DNA or RNA strands, leading to chain termination or non-functional nucleic acids. one of the limiting factors is these analogues are not only used by viral enzymes, but also by mammalian enzymes, which largely accounts for their potential toxicity.

t he treatment of FIP has evolved significantly from the initial reports of success by Peterson et al. in 2019. t his initial study investigated the use of GS-441524 in 31 cats with FIP. o verall, 80% of these cats survived long term. Four of the nonsurviving cats were initially severely affected, and were either euthanised, or passed away in the initial days of the treatment regime. t he treatment regime in this study involved daily subcutaneous injections for 12 weeks. A small proportion of cats required repeat protocols following relapse. Considering this disease was almost universally fatal, long-term survival in 80% of cats is remarkable.

GS-441524 has never been available as a legal treatment option in cats. t he publication from Peterson et al. (2019) resulted in the establishment of a black market for GS-441524 around the world. t his medication became surprisingly easy to order online, getting through the border disguised as cosmetics. As a result of this widespread use, there are some large studies emerging on treatment outcomes. Jones et al. (2021) published the results of an online survey of outcomes of almost 400 cats. t here are some obvious limitations of an online survey, however the results still provide some useful insights. only 8.7% of owners reported receiving significant help from their veterinarian – no doubt due the legalities of this. Almost 90% of the owners reported noticing improvement after 1 week. 12.7% of cats experienced a relapse, with only 3.3% of cats dying despite treatment.

As GS-441524 is not able to be obtained legally in New Zealand, its use cannot be supported. t his is especially the case now

Contact: Ryan.Cattin@arcvets.co.nz

legal options are available that are substantially cheaper than the black-market options. Remdesivir is a prodrug of GS441524, that we now know is rapidly metabolised into GS441542 in cats, so other than different dose rates they are very similar medications.

As noted above, there are large numbers of cats that have been treated without veterinary support. t his, and the everchanging research provides opportunities for vets to help cats in the future. Veterinarians in New Zealand need to re-take a central role in treating FIP as our knowledge and skills will help to ensure more cats are treated and survive long term. I think the main way we can do this as a profession is to keep up with the current literature and treatment protocols. As a result of these past events, there are large social media groups where owners are proving advice of variable accuracy. t here are frequent comments by owners that their vet did not know about FIP treatment, which of course drives the owners to seek information elsewhere. While these groups are a great source of support, the treatment information provided by other

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 18

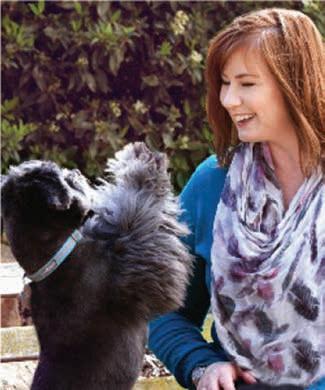

Ollie, one of the adorable cats treated at the Animal Referral Centre [Photo courtesy of the author]

owners is often out of date or incorrect. I hope that some of the insights below will help to start some more conversations.

the severity of the cat at presentation seems to be the biggest factor influencing survival with treatment. overall, around 85% of treated cats will survive. If the cat survives the first week of treatment, this survival rate increases to over 95%. In a rapidly progressive disease, clearly early diagnosis and prompt treatment are key. there are some very useful recent guidelines on how to reach a clinical diagnosis of FIP ( thayer et al. 2022). unfortunately, there is inevitably a delay in reaching a clinical diagnosis while awaiting histology, or a PCR (of effusion for wet FIP, or CSF for dry FIP). We routinely start treatment when we have a very strong index of suspicion of FIP while awaiting the results of the diagnostic tests. treatment trials without diagnostic tests should be discouraged if possible as the development of resistance of these vital medications is a big concern. there has not yet been much investigation into the mechanisms of resistance development, but we do see it already. A small proportion of cats appear to be resistant to medications from the onset. more often we suspect resistance develops during treatment which can be partial requiring a higher dose, or complete. We have anecdotally observed a cluster of resistant cats from one location with dubious use of remdesivir which has raised some alarm bells.

treatment protocols have changed significantly with time. Initially we started parenteral remdesivir in every cat as the oral absorption was presumed to be poor. Subcutaneous injections at home for 12 weeks were a big challenge for most owners, especially as the solution is acidic, so stings when administered. t he recommended starting dose has crept up with time as remdesivir was shown to be safe. A study from uC Davis recently investigated the absorption of oral remdesivir, and it was found to be around 40–50% (Cook et al. 2022). So, the transition to oral doses has necessitated a doubling of the administered dose. unfortunately, under-dosing remains a very big problem with both out of date doses administered, and parenteral doses given orally. t here is concern this may lead to resistance to treatment.

t he Animal Referral Centre is currently offering two main treatment options for cats with FIP; starting with 2 weeks of injections, followed by 10 weeks of oral capsules, or oral capsules alone. It is unknown whether any parenteral treatment is needed. t he pharmacokinetics of remdesivir has only been studied in healthy cats. We strongly suspect that sick cats, especially with effusive disease, will have altered absorption of oral medications. We are currently evaluating the pharmacokinetics and treatment outcomes of these two groups. molnupiravir closely resembles GS- 441524, but is an analog of cytidine rather than adenine. t here are no published comparative studies comparing the efficacy of remdesivir compared to molnupiravir. t he optimal dose of molnupiraivir remains unknown. t his medication has a narrower safety margin compared to remdesivir with higher doses seem more likely to result in a severe leukopenia and other adverse effects. t here is currently one study evaluating the use of molnupiravir in cats that noted broadly similar success rates and relapse rates to those published with remdesivir in 30 cats that had failed remdesivir (Roy et al. 2022). Remdesivir/ GS-441542 has been in use for a longer period of time resulting in substantially more published literature, so this remains our current initial treatment of course. Fortunately, the costs of treatment have fallen dramatically recently, especially with the use of oral capsules. Per capsule, the cost of remdesivir is currently very similar to molnupiravir. As molnupiravir is usually a twice-daily medication, a treatment protocol is typically more expensive at the current prices. more information will come in the future, with comparative studies underway. However, with the current information available molnupiravir is probably best reserved for treating cats that have failed remdesivir.

monitoring during treatment is vital to help determine which cats need an increased dose, or duration of treatment. t his is one of the areas veterinarians can help most. one of the secondary aims of our research is to evaluate “milestones” that should be met during the treatment, so these can be used to help predict the response to treatment and make early adjustments. We routinely monitor for

resolution of the clinical signs, effusions, and biochemical markers at roughly monthly intervals during and after treatment.

Cats with dry/neurologic/ocular FIP remain a challenge, both for reaching a diagnosis, and for monitoring treatment. Dry cases tend to have much less dramatic (and often no) biochemical changes and will often retain some mild-moderate neurologic deficits even when cured which presents a challenge. We need a high index of suspicion for these cases to ensure they are promptly diagnosed. Fortunately, there is a relatively limited list of common differential diagnosis for neurologic signs in this signalment (i.e. young often purebred cats), with FIP being by far the most common diagnosis.

It is very difficult to keep up with the rapidly changing literature, but we are here to help! t he Animal Referral Centre is offering free phone consultation to veterinarians in New Zealand to help provide the most up to date treatment advice as part of our studies, so please do not hesitate to get in touch.

References

Cook S, Wittenburg L, Yan VC, Theil JH, Castillo D, Reagan KL, Williams S, Pham CD, Li C, Muller FL, Murphy BG. An optimized bioassay for screening combined anticoronaviral compounds for efficacy against feline infectious peritonitis virus with pharmacokinetic analyses of gS-441524, remdesivir, and molnupiravir in Cats. Viruses 14, 2429, 2022

Jones S, Novicoff W, Nadeau J, Evans S. Unlicensed gS-441524-like antiviral therapy can be effective for at-home treatment of feline infectious peritonitis. Animals 11, 2257, 2021

Pedersen NC, Perron M, Bannasch M, Montgomery E, Murakami E, Liepnieks M, Liu H. efficacy and safety of the nucleoside analog gS-441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 21, 271–81, 2019

Roy M, Jacque N, Novicoff W, Li E, Negash R, Evans SJ. Unlicensed Molnupiravir is an effective rescue treatment following failure of unlicensed gS-441524-like therapy for cats with suspected feline infectious peritonitis. Pathogens 11, 1209, 2022

Thayer V, Gogolski S, Felten S, Hartmann K, Kennedy M, Olah GA. 2022 AAFP/ everyCat feline infectious peritonitis diagnosis guidelines. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 24, 905–33, 2022 l

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 19

The importance of physical rehabilitation

N INA F I el D BVSc CCRt

We all want to live our best lives, physically and mentally, and most pet guardians want the same for their animals even if they are unaware of how to provide it! Whether the pet is a lieon-the-couch companion, an essential assistant dog or a “vital” staff member, their owners generally want the best for them or the best financial outcome after a surgery to promptly restore a dog back to work.

Because of human nature, motivation will differ and the ability to complete an entire physical rehabilitation programme to regain 100% function is rare, as human physiotherapists will attest to! However, this shouldn’t stop veterinarians from recommending a rehabilitation programme because even a halfcompleted rehab programme is better than nothing.

A rehabilitation programme aims to restore the patient to normal function, or as near to normal function as possible, after a health issue. t hese health issues could be an injury, surgery, illness, or just general aging. It is a physiotherapy programme but the reason I refer to this as rehabilitation is because only people trained through a human physiotherapy programme can call themselves physiotherapists. Veterinarians providing these services should have completed a post-graduate training course and will refer to themselves as Veterinary Rehabilitation t herapists. most veterinary surgical specialist centres in New Zealand will offer rehab programmes from their premises and there are other private providers dotted about the country.

Reasons to recommend a rehabilitation programme t he most common reasons that an animal is referred to me by another veterinarian are: post-surgical recover, an injury for which surgery is not an option, or lame/sore/unbalanced without a clear diagnosis. Some owners whose dogs perform agility will bring these dogs to me for maintenance therapy or because they themselves are unhappy with the way their dog is moving. o thers are looking to help their arthritic dogs be more comfortable.

The first visit on the first visit I’ll get a verbal history from the owner and watch the animal moving. You can assess how physically comfortable a dog is by their posture, whether they continue to stand in a consult room or lie down. How they sit and how quickly they move from sit to stand will give you an indication of pain or weakness. It is amazing how few dogs will walk or trot next to their owners in a straight line but usually after a few attempts with some circling and changes of direction, an assessment can be made on their gait.

t hen I perform a physical examination including orthopaedic and neurological examination depending on the issue. treatment begins with the examination as I’m usually massaging as I go. my idea is the dog relaxes and gets used to my touch. What I love about these cases is the ‘incidental’ things that can be found especially in older animals. If you are a 7-year-old, active dog that has ruptured a cranial cruciate ligament, chances are you also have some stiffness in your spine and maybe a front leg. t his is especially true if you have been lame for a while before receiving surgery or visiting the vet in the first place. t his is also a good time to discuss weight control, pain relief, diet supplements, home modifications and other health issues. t his holistic approach is a great way to educate owners on providing their pets with management they may need for the rest of their lives.

Alongside the examination with the massage comes other manual therapies such as joint manipulation and muscle stretching and modalities to help with inflammation and healing (see Box 1).

Box 1. Manual therapies and treatment modalities used for rehabilitation

Manual therapies and treatment modalities

Notes

Joint manipulation t his encourages the joint through a normal range of motion. t his is often restricted by joint injury or surgery, muscle shortening or tightness. Joint mobilisation helps to stretches the joint capsule or ligament, allowing a good range of motion.

Stretching

Increases the flexibility of the muscles, allowing the fibres to realign for better healing and allowing the joints to have a good range of motion.

Laser Helps with inflammation and healing. uses light energy to stimulate tissues. Red light is absorbed by mitochondria and this increases At P production. Physiologically this results in a decrease in inflammation, oedema and pain and an increase in wound healing. t herapeutic ultrasound Sound waves that cause microscopic air bubbles that stimulate cell membranes and promote healing.

Contact: ninathevet@gmail.com

Believed to stimulate the central nervous system to release chemicals into the muscles, spinal cord and brain. t hese biochemical changes stimulate the body's natural healing abilities. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation. (NmES, E-Stim) used to preserve or recover muscle mass, particularly in totally immobilised patients.

Acupuncture

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 20

Cl INICA l UPDAte

Therapeutic exercise

t hen it’s time for some therapeutic exercise. A limb either needs strengthening, or to maintain its strength whilst the injured area heals. t he animal still needs to move to toilet etc., so this needs to be in a controlled fashion so the injury is not exacerbated, or the surgical site compromised. t he mental health of the patient (and the owner) also needs consideration – crate resting a 12-year-old dog is much easier than a dog of 12 months!

Exercises suggested will depend on the time since surgery, the age and overall mobility of the animal and also what the owner wants to achieve. I usually send my clients home with three exercises to be performed daily or 2–3 times per day. Following surgery the animal is usually standing, or being supported to do so and the exercise might be just putting a small amount of weight on a limb for a few seconds. t his will be repeated 2–3 times and maybe again later in the day. Small and often is usually the key. I will see the patient again in 1–2 weeks and normally increase the difficulty or the duration of the exercises. Increasing difficulty might be adding a different surface (that is less stable) or more weight by, for example taking two legs off the ground (see Figure 1).

So a home exercise programme might look something like this; massage spine and both hind limbs. Perform range of motion of all hindlimb joints, starting with toes up to the hip. t hen the three exercises: e.g. front legs raised (this increases the weight taken by the rear end), 3-leg stance (one limb is taken off the ground to make the other three hold more weight) and proper sit (Figure 2a). For a proper sit the stifles should be over the feet – nice and straight rather than slouched to the side (Figure 2b). t his is often due to a stifle issue: the dog doesn’t want to flex the straight stifle as it’s uncomfortable – watch for this with cruciate disease. t his is often something you may notice initially in the consult room whilst the dog is moseying about whilst you talk to the owner.

It always amazes me how everyone adapts to the new regime. o wners that are invested in their animal’s future and are fully engaged get good results. I guess those that aren’t I don’t see again and maybe the pet does well enough. Pets have been recovering from surgery and injury for many decades without specific rehabilitation but with it the results are better and/or faster. Gone are the days when the dog is confined to a kennel for 6 weeks……arrgggg! t his is not necessary and can, in fact, be deleterious as the owner will often let the dog out to toilet and let it run about madly for a few moments undoing days of healing, if not causing damage to implants or healing tissues.

A home exercise programme can require a fair amount of commitment from the owner but I will try and make life for all as easy as possible by finding ways to make it work with the facilities and environment available. Where there’s a will, there is a way. o ften floors need to be made less slippery with, for example, carpet mats over lino or tiles for post operative patients or geriatric dogs. Ramps may need to put over steps and harnesses required to help the owner support a large dog down steps or into a vehicle. A crate so the dog is restricted when not supervised makes life a lot easier for everyone. A harness is a much easier way to control the dog on a lead so it walks slowly using all four limbs.

My rehabilitation practice

At present I offer rehabilitation services from the veterinary practice I do GP work at. I have some equipment which is brought out as necessary but it is also a good idea to be creative with what you have around you: for example, I have the street outside with its curbs, plus a set of six concrete steps across the road. Perfect! Hills are not plentiful in Ashburton but there are a few slopes that count for ‘hill’ work, especially in the initial stages and many irrigation ponds for later hydrotherapy! Garden stakes on squashed coke cans can be used for caveletti work and inflatable camping mattresses for ‘wobbly’ surfaces.

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 22

a

Figure 1. e xamples of therapeutic exercises. [Image courtesy of the author]

b

Dogs may be a bit anxious initially, but I get a real buzz from the waggy tails that great me on the second or third visit, and of course seeing the progress that is made from visit to visit. With acute injury or post-surgery cases, I may see them 2–3 times in the first 2 weeks to get the ball rolling so to speak, but then it’s generally every 2 weeks. t his is mainly due to my availability (vetting is busy – anyone else noticed!) and also the client’s time and finances. Geriatric/maintenance treatments are 4–8 weeks apart.

I encourage you to find your closest rehab provider and refer patients to them. Your clients will thank you and this will increase their bond with you and everyone will see improvement in outcomes. Even with one visit the client will be given tools and strategies to help their pet.

Recommended reading

WI Baltzer. Rehabilitation of companion animals following orthopaedic surgery. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 68, 157–67, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2020.1722271 l

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 24

Figure 2. good sit (a) and bad sit (b) [Image courtesy of the author]

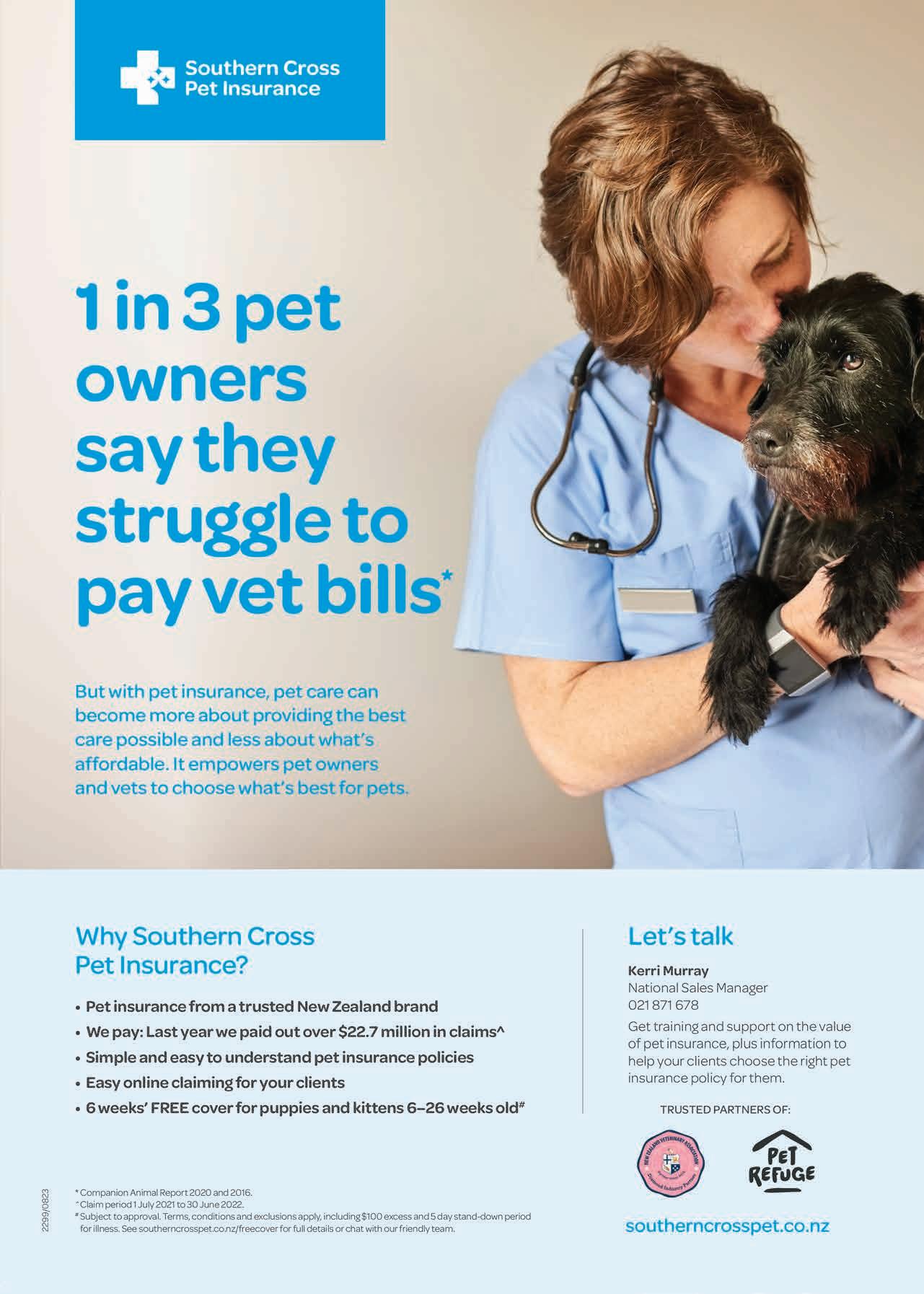

Cl INICA l UPDAte Giardia infection in cats and dogs

NAtA l I e l l Oy D, BVSc, MANZCVS (Medicine of Cats), Companion Animal Veterinary Adviser, Zoetis New Zealand

Introduction

Giardia duodenalis (syn G.lamblia, G.intestinalis; (henceforth called Giardia) is a gastrointestinal parasite of mammals found worldwide (uiterwijk et al. 2019). Global prevalence rates of Giardia are between 5 and 15% for dogs and cats (Carlin et al. 2006). However, there is high heterogeneity between populations. Young animals were more likely to be infected than older animals and symptomatic cats and dogs are more likely to be infected than those that are asymptomatic.

t he average annual incidence of Giardia in people living in New Zealand is one of the highest among the industrialised countries (Canterbury DHB 2022). t here is a dearth of published information however, regarding prevalence of infection in dogs and cats in New Zealand. A study from 1991 reported prevalence rates of 3–25% among asymptomatic dogs and cats from Palmerston North and Hamilton (Brown et al. 1991). In addition to this data, a New Zealand reference laboratory has published figures of 25% (canine) and 13% (feline) positive Giardia tests among faecal samples submitted to the lab for diarrhoea panels (Idexx 2019).

u p-to-date published data for cats and dogs is needed to provide New Zealand practitioners with accurate prevalence information on Giardia to help inform their approach to symptomatic animals. t he purpose of this article is to provide practitioners with a summary of the current recommendations on zoonotic potential, diagnosis and treatment of this parasite in New Zealand dogs and cats.

Zoonotic potential

Giardia duodenalis comprises eight molecularly identified genotype strains or “assemblages” designated A through H. While the specific assemblages that cats and dogs are infected with (C,D and F) are often different from that which infects human (A and B), assemblage A and B have been seen in both cats and dogs hence there is a small potential for zoonotic transmission between humans and dogs and cats (Ballweber et al. 2010).

An infected human can be a source of infection to a cat and dog which then, in turn, may represent a zoonotic risk. While

the zoonotic risk is low, people in contact with infected pets should consult their doctor if they have relevant clinical signs.

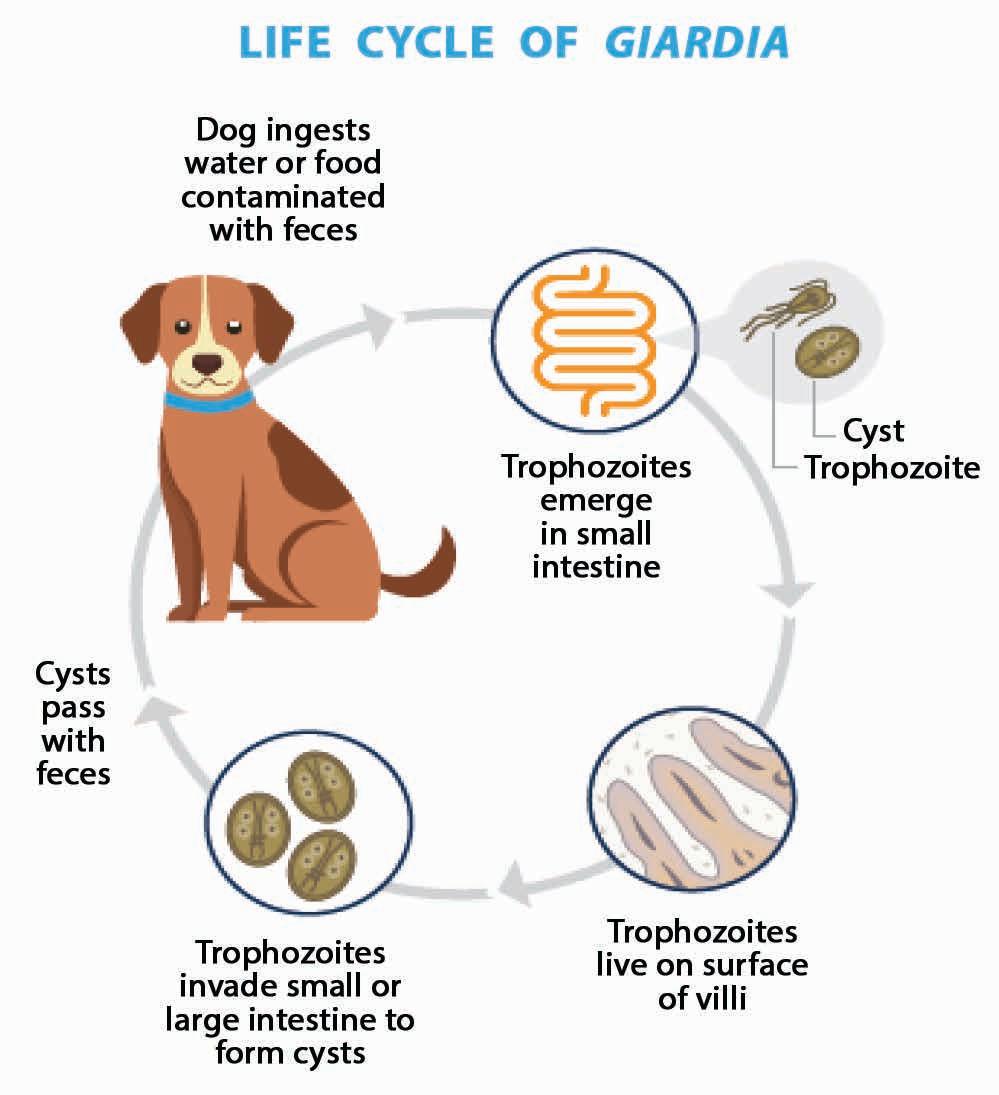

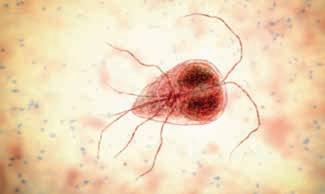

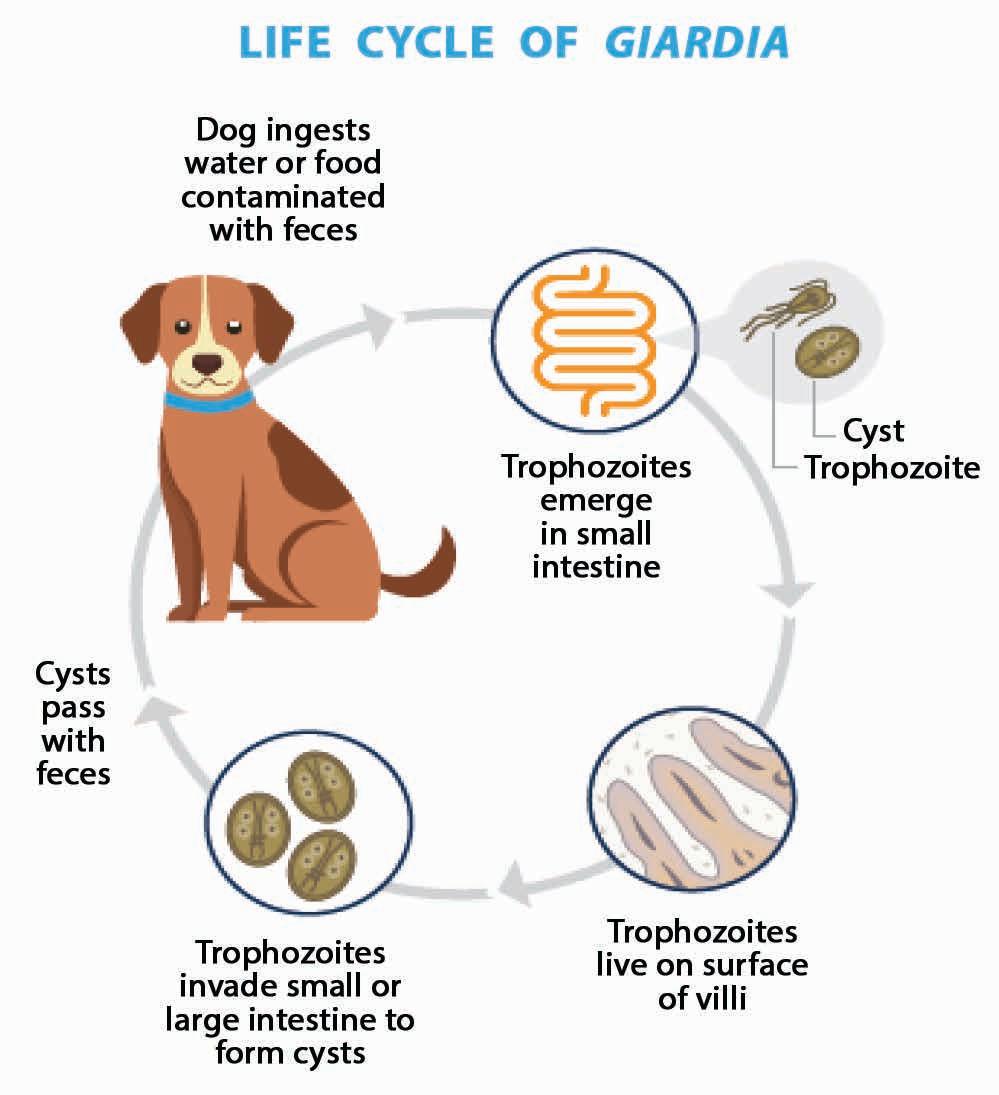

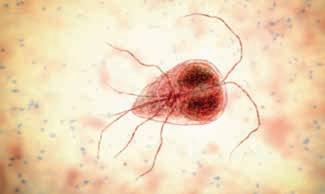

life cycle

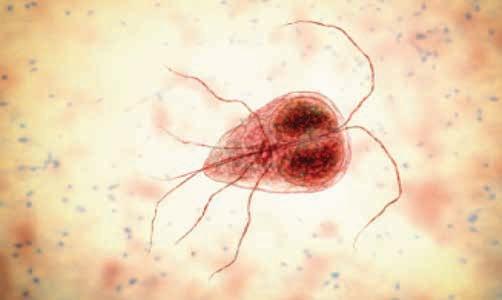

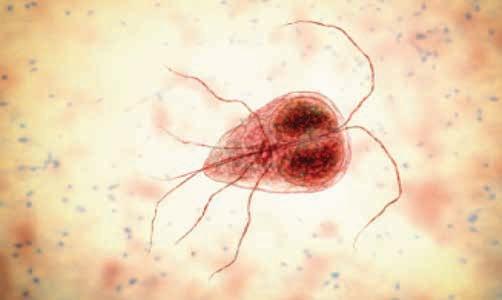

Giardia exists in two stages described below (Nagamori and Penn 2021). See Figure 1 for an illustration of the lifecycle. Trophozoite: t his is the motile stage in the small intestine. trophozoites are usually 12–17 μm x 7–10 μm in size. t hey are motile, flagellated organisms that originate from cysts and appear teardrop or pearshaped. trophozoites are bilaterally symmetrical and have two nuclei, each

Contact: natalie.lloyd@zoetis.com

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 26

Figure 1. life cycle of Giardia (Nagamori and Penn 2021) [Image courtesy of Dr. yoko Nagamori]

with a large endosome. t hey also have a pair of transverse, dark-staining median bodies. trophozoites inhabit the mucosal surfaces of the small intestine where they attach to the brush border, absorb nutrients and multiply by binary fission. t hey usually live in the proximal portion of the small intestine.

Giardia can also be underdiagnosed, as cysts may be shed intermittently and can deteriorate in faecal solutions very quickly, making detection and identification more difficult. Given these complexities, there is no easy, quick test with 100% accuracy when it comes to diagnosing a Giardia infection, but there are many tests that can be used in conjunction to detect its presence (Saleh et al 2019; CAPC 2019).

Veterinary patients may be asymptomatic and infected with Giardia. Interpretation of a positive test in an animal with diarrhoea requires careful assessment of the animal’s history, signalment and physical exam in order to understand the significance of the test result and avoid interpreting a positive result incorrectly.

When should we be testing for Giardia?

Veterinarians should test cats or dogs for Giardia when they show symptoms such as chronic or intermittent diarrhoea (CAPC 2019). Patients at higher risk for Giardia infection, such as in contact, young animals or those at higher risk of contracting Giardiasis due to lifestyle, may benefit from Giardia screening at routine wellness examinations (Calvin et al. 2006; uiterwijk et al. 2019).

testing methods for Giardia

Cyst: t his is the infective stage responsible for environmental contamination trophozoites invade the small or large intestine to form cysts. Cysts are ellipsoidal, nonmotile and contain 2–4 nuclei with long- and short-curved rods. t hey are 9–13 μm x 7–9 μm in size and possess a thick refractile wall (see Figure 3 above). Newly formed cysts pass in the faeces. Cyst shedding may be continual over several days and weeks but is often intermittent, especially in the chronic phase of infection. Cysts can survive for several weeks to months in the environment, whereas trophozoites cannot.

Clinical signs

upon infection, dogs and cats may be asymptomatic or present with symptoms such as weight loss and diarrhoea. Diarrhoea may be continuous or intermittent and is seen more commonly in puppies and kittens. Where the pet is symptomatic, faeces are usually soft, poorly formed, pale, malodorous, contain mucous and appear “fatty”. Watery diarrhoea is unusual in uncomplicated cases and blood is usually not present in faeces. occasionally vomiting occurs. minimum database clinical laboratory findings are usually normal (Calvin et al. 2006).

Diagnosis testing for Giardia presents challenges

It can be challenging to correctly diagnose a Giardia infection, and in fact, Giardia can be both over and under diagnosed. Giardia can easily be mistaken for many other objects (pseudoparasites) within the faeces such as yeast, that can lead to potential overdiagnosis.

t here are a number of different testing methods available to diagnose Giardiasis in symptomatic animals based on direct observation of the organism in faeces, or detection by ELISA or PCR. testing methods can be used alone, or in combination.

In one study, combination of faecal floatation with a commercially available Giardia spp. antigen assay had a combined sensitivity of 97.8% (mekaru et al. 2007)

multiple tests performed over several (usually alternating) days may be necessary to identify infection because of the possibility of intermittent shedding of cysts (Calvin et al. 2006; CAPC 2019; ESCCAP 2019; Guffydd-Jones et al. 2013).

testing for a broader range of parasites by faecal floatation with centrifugation using both 33% zinc sulfate solution and sugar solutions may also be warranted at wellness visits in patients who are asymptomatic but have high-risk factors for giardiasis (Zajac et al. 2012; CAPC 2019). See table 1 and Figure 3 below for comparison between floatation methods.

1. Faecal examination

Faecal examination is simple, quick and inexpensive. It remains one of the most important procedures to perform when evaluating gastrointestinal disorders in pets (matz and Guilford 2003). Despite this, routine faecal testing is not widely practiced amongst companion animal practitioners in New Zealand. Barriers cited to performing in-house faecal examinations are time constraints (for sample preparation and evaluation), reluctance to handle patient’s faeces, and concerns around accuracy in technical interpretation of samples. For this reason, Giardia infections in New Zealand are most often diagnosed at external

Companion Quarterly: Official Newsletter of the Companion Animal Veterinarians Branch of the NZVA | Volume 34 No 3 | September 2023 28

Figure 2. 3-D illustration of trophozoite (Nagamori and Penn 2021) [Image courtesy of Dr. yoko Nagamori]

Figure 3. Use of 33% ZnSO4 for faecal floatation improves detection of Giardia compared to sugar solution [Image courtesy of Dr. yoko Nagamori]

Giardia cysts in sugar solution

Giardia cysts in 33% ZnSO4 solution

reference laboratories. Diagnosis at the point-of-care can provide a quick, reliable and inexpensive option but is often overlooked.

a. Detection of Giardia by a direct faecal smear (Gruffydd-Jones et al. 2013)

l mix a small amount of fresh (<30 minutes old) faeces with a drop of saline (not water) on a slide to make a suspension, place coverslip and examine under a microscope at a magnification of 100x and 400x.

l motile trophozoites can be seen showing a “falling leaf” motion

b. Detection of Giardia using zinc sulfate centrifugal floatation (CAPC 2019; Gruffydd-Jones et al. 2013; t RoCAP n.d.)

l test of choice for the visualisation of Giardia cysts in solid/semisolid faeces.

l Solutions concentrate and separate intestinal parasite eggs and cysts from faecal debris.

l 33% ZnSo4 solution (SG =1.018) is recommended for examination for Giardia cysts.

l Avoid use of saturated salt or sucrose solutions as they may cause distortion of the cysts.

l Cysts are oval, 10–12 µm long and surrounded by a thin wall (Figure 3).

c. Artificial Intelligence at the point of care

In clinic diagnostic platforms (such as Vetscan Imagyst; Zoetis, Auckland, NZ) are now available to practitioners in New Zealand. t hese platforms can help to overcome some of the recognised barriers to in house faecal testing through their clean and userfriendly sample preparation processes and accurate interpretation of results (Nagamori et al. 2020, 2021).

Vetscan Imagyst uses an automatic scanner and cloud-based, deep learning algorithms to locate, classify and identify parasite eggs and cysts including Giardia found on faecal microscope slides. Vetscan Imagyst sample preparation is comparable to reference methods and showed good sensitivity and specificity across different parasites tested when compared to experts (parasitologist) review (Nagamori et al. 2021). Both sugar and ZnSo4 solutions are available to clinicians to provide a complete diagnostic evaluation of most common internal parasites of cats and dogs (i.e. Toxocara, Toxascaris, Trichuris,

33% ZnSo4 1.18 Floats common helminth and protozoa eggs and cysts

Preferred for Giardia

Sheather’s sugar solution 1.25 Floats common helminth and protozoa eggs and cysts

Causes less damage to parasite eggs and cysts than salt solutions

table

Less effective for floatation of tapeworm eggs than others

Does not float some fluke and unusual tapeworm and nematode eggs

Less sensitive than 33% Zn So4 for Giardia

Creates sticky surfaces

Drug Route Dosage Fenbendazole oral 50 mg/kg once daily for 3–5 days

Pyrantel+praziquantel+febantel oral 56 mg/kg (based on febantel component) once daily for 3 days metronidazole benzoatea oral 10–25 mg/kg once or twice daily for 7 days

Furazolidoneb (cats only) oral 4 mg/kg twice daily for 7–10 days

a Neurological toxicity may develop following either chronic therapy or acute high doses b Furazolidone causes inappetence and vomiting

Ancylostoma, Taenia, Cystoisospora and Giardia spp.) (Nagamori et al. 2020, 2021).

2. Faecal ELISA Test (Giardia antigen)

Identification of Giardia in faeces using an ELISA may be performed in-house or at an external reference laboratory.

l Giardia ELISA assays are approved and commercially available for patientside testing in dogs and cats (e.g. SNAP Giardia test, IDEXX Laboratories, Hamilton, NZ; Witness Giardia Antigen testkit, Zoetis; Vetscan Giardia Rapid test (canine only), Zoetis).

l ELISA techniques do not appear to be more sensitive than careful faecal screening (Gruffydd-Jones et al. 2013).

l t hese tests are helpful to use alongside faecal floatation to eliminate false negatives due to shedding of low numbers of cysts ( t RoCCAP 2019).

l Positive faecal ELISA results should be interpreted in relation to clinical presentation as many clinically healthy dogs and cats will test positive but do not require treatment (ESCCAP 2019).

l ELISA tests may remain positive even after treatment for variable periods of time and should not be used as a guide to determine reinfection or failure of treatment (CAPC 2019).

3. PCR testing for Giardia

PCR testing is performed on faeces at an external reference laboratory. PCR testing is available in New Zealand at IDEXX laboratories.

l t hese tests amplify Giardia DNA in faecal material.

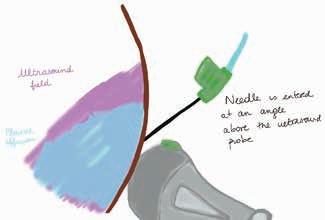

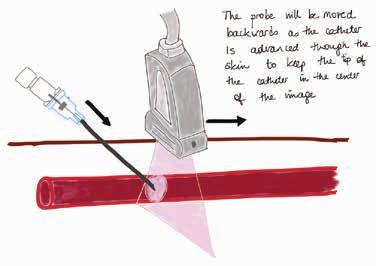

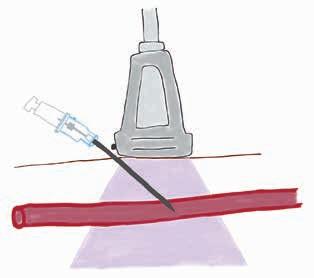

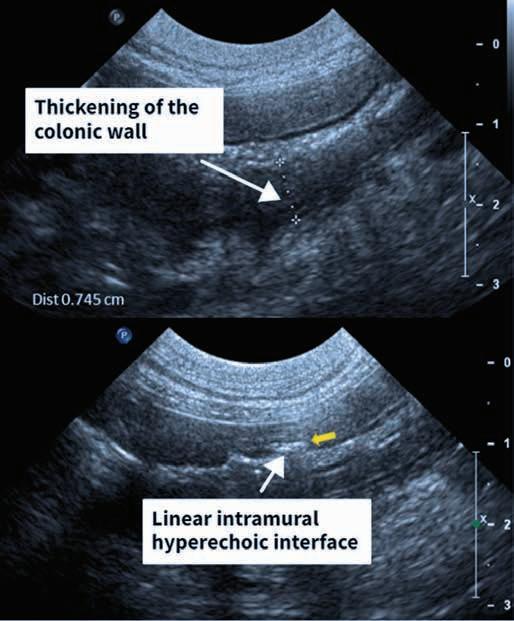

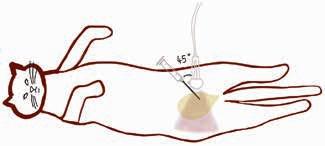

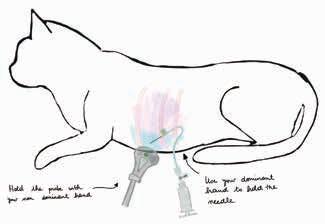

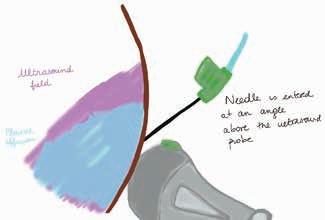

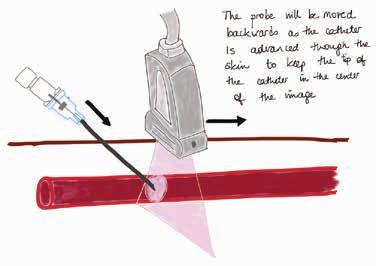

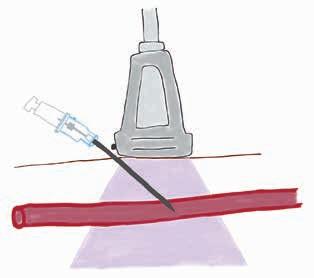

l DNA sequencing can allow determination of Giardia assemblages.