2023 ISSUE

Welcome to the 6th annual edition of Cat Among the Pigeons. It has been a pleasure to work on this edition. From working with younger pupils to designing the end result, I have learnt so much.

‘Cat Among the Pigeons’ was launched when I was in the First Year, and so it has been inspiring to watch it grow throughout my time at Caterham: I am extremely proud to have edited this edition of the magazine. Whilst Geoffrey Pidgeon is sadly no longer with us, I can remember interviewing him in my Fourth Year and his open-mindedness and optimism has stayed with me, an ethos which I hope has been maintained in this edition.

The magazine has always acted as a mouthpiece for the issues that students are exploring, but this year feels especially prolific, with essays exploring the controversy of AI and social media to poems depicting Ancient Greek romance. It is a testament to the Caterham community how well these pieces fit into our chosen theme of ‘Visibility’, and it has been a joy to see all the creativity and love for the arts ranging from students in First Year to Upper Sixth.

Special thanks must go to Ms. Stedman and Ms. Veldtman for all their advice and guidance throughout the process, as well as Jo Ogilvie, our designer, for her help in editing the magazine. I would also like to thank the whole editorial team who have helped so much throughout the last 12 months – hopefully all those meetings paid off! Lastly, huge congratulations to Holly Gordon Clark for winning the Pidgeon Prize for Literature for her poetry that can be found at the start of the magazine.

We hope you enjoy this year’s edition of ‘Cat Among the Pigeons’!

DEPUTY EDITORS

Naomi Bacchus SHE/HER Photography Editor

Tristan Evans HE/HIM Modern Foreign Languages

Estella Yip SHE/HER Diversity

Tia Singh SHE/HER Classics

James Stuart HE/HIM Humanities

Bella Beadle SHE/HER Music & Film

Ammara Khan SHE/HER Philosophy & Ethics

Amelia Burns SHE/HER Digital Culture

Kayla Prashad SHE/HER Junior Editor

Mathilda O'Malley

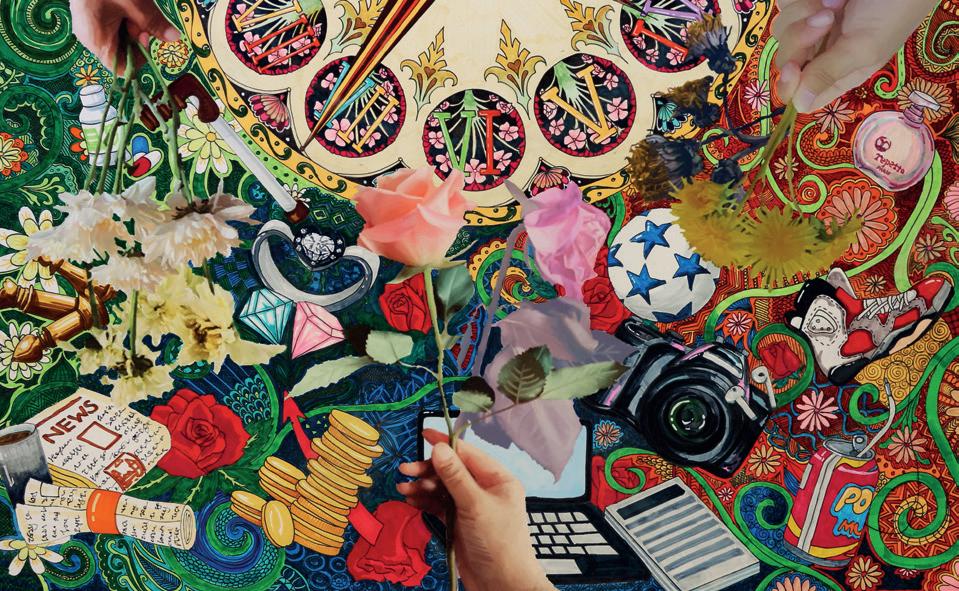

The theme of visibility is incredibly broad; it encompasses a vast range of thoughts and perception. As text editors, it has been our absolute honour to acknowledge these ideas from a vast age range of submissions. The theme of visibility means so much to people which allows it to be so beautifully portrayed through arts and literature: which is why this edition is so special to us – it is a celebration. From poems to essays, we have been able to understand what visibility actually means to people and what effect this has had in their lives. It has been immensely rewarding to work alongside the different year groups and gain further depth into what inspires them to write such extraordinary pieces of work, whilst developing our own ideas too. Reading over these texts has been a pleasure to us; to see such talent within the younger years has been extremely encouraging and we are glad to help stimulate this. We hope the depth of talent at Caterham and the students’ ability to connect with matters close to them is evident in this issue. We give our gratitude to Ria Manvatkar, Ms Stedman and the rest of the team, as without them this would not have been possible.

VISUAL EDITOR

In an environment filled with diverse perspectives, experiences, and artistic brilliance it is essential to acknowledge the significance of visibility to young adults. Visibility transcends the surface-level notion of merely being seen as it encompasses the profound impact of being recognised. Sharing the responsibility of Visual Editor this year has allowed us to broaden our use of artistic practices in this issue as we delve into art, fashion, and photography with an equal focus on visibility, emphasising the importance of embracing authenticity, fostering inclusivity, and empowering every individual within our school. Visibility is not limited to recognition; it empowers individuals to achieve their full potential. By shining a light on student talent and accomplishments we hope to encourage more transparency amongst our community at Caterham.

The time spent on this issue has been a been a brilliant opportunity and a pleasure to do so alongside such a hardworking team. We also extend our thanks to Jo Ogilvie (Designer) who has been instrumental in ensuring the vision has become a reality.

Narayan Minhas HE/HIM Deputy Junior Editor Lynus Lam HE/HIM Assistant Junior Editor COVER Shadows by Emma Tagliarini Flora Hannay

SHE/HER TEXT EDITOR TEXT EDITOR Anoushka

i Zz Y Ha S sA n SHE/HER SHE/HER EDITOR IN CHIEF

Gadkar

SHE/HER

Ria Manvatkar

Candice Bortey SHE/HER Architecture & Design Editor

VISUAL EDITOR

2

James Walker HE/HIM

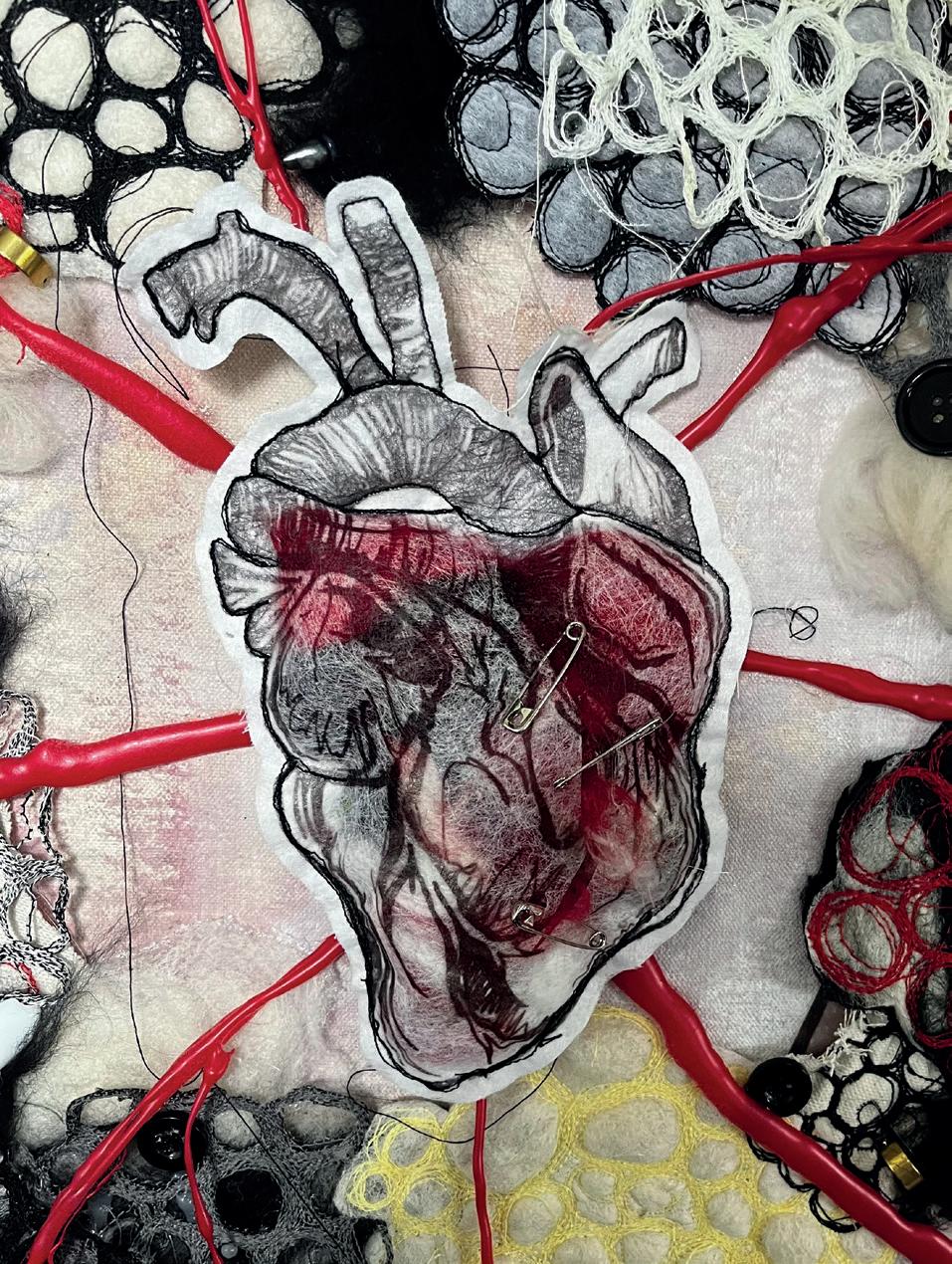

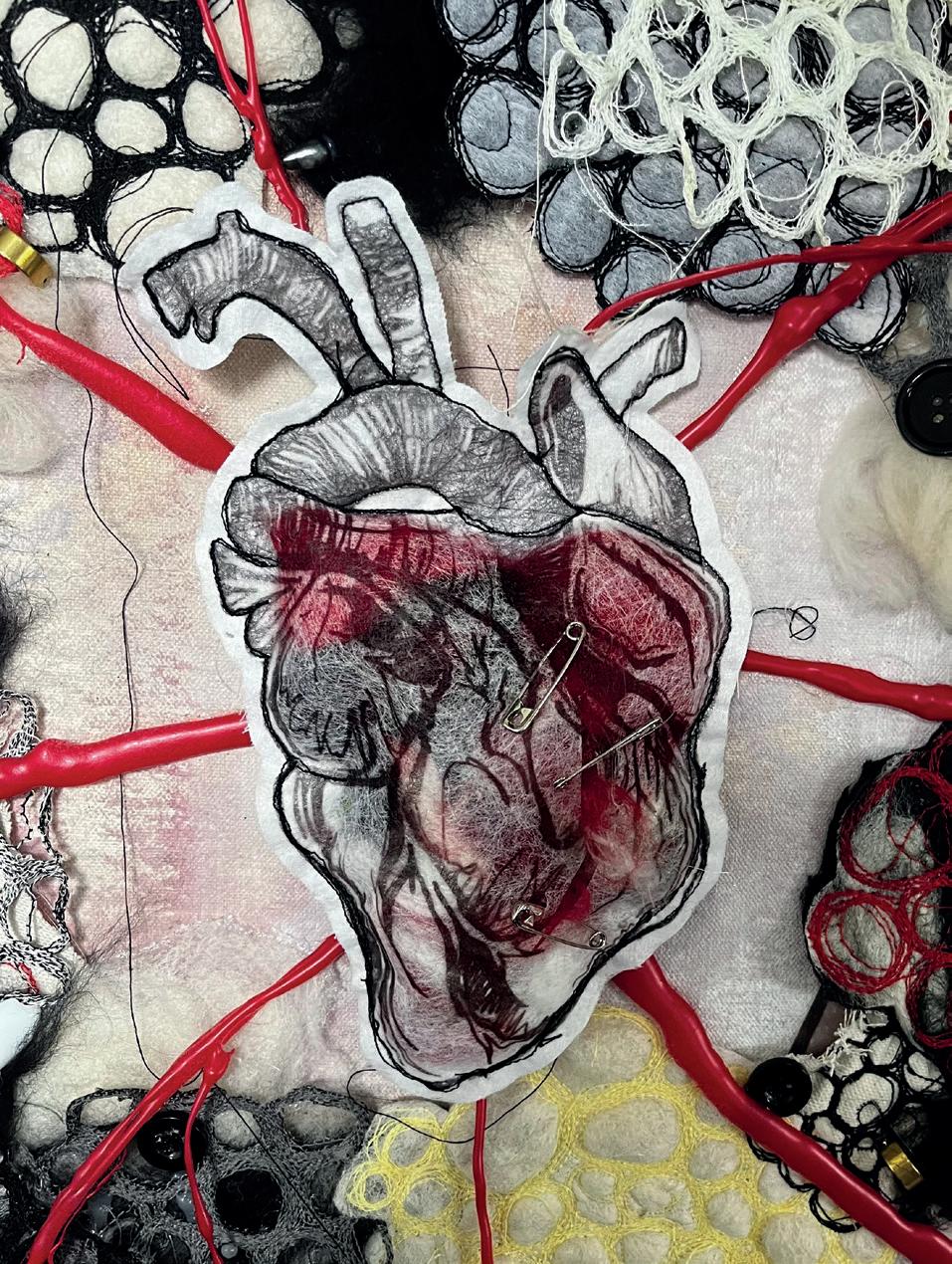

Seagull 4 Holly Gordon Clark Flo Black Hotels are Figments of Our Imagination 5 Holly Gordon Clark Simi Akingbade Is AI the Death of the Artist? 6 Xavier Parker My Star’s Light 8 Izzy Gooding Joel Veldtman Ode to Lost Time 9 Abbie Wynn Valerie Pang John Brown, Hero or Lunatic? 10 James Stuart Scarlett Sanderson-Marsh Third Year Historical Portraits 11 Precariously 12 Kate Fan Gabby Toone Sight 13 Liam Kitavujja Ava Floyd ‘Spray Paint Dress’ 14 James Walker GCSE Fine Art 16 The Classics Revisited: Exploring Greek and Roman Art at the Louvre 18 Kayla Prashad My Companion 19 Bailey Carpente Izzy Hassan Limerence 19 Ammara Khan Izzy Hassan Come Die with Me: Iphigenia at Aulis 20 Bella Beadle The Miracle at Aulis 21 Hettie Nolan Harry Evans Verses of Migration 22 Anoushka Gadkar Mili Greener Dysphoria 24 nax Olivia Stone Prediction I 25 nax Sophie Chung Doctor… Who Exactly? 26 Ollie Rose Mikako Shiomi 2 + 2 = 5 28 Amelia Burns Sydney Mei Ten 29 Estella Yip Mark Wolstenholme Nectar 30 Oliver Khiara Sienna Algar Eye of the Storm ........................... 30 Clemmie Fagan Andrew Or Mordeton, Cheshire 31 Narayan Minhas Alice Keyworth Visibility in Nope 32 Dante Butler A Level Art .................................. 34 Shadows 36 Emma Tagliarini Harry Evans This Woman’s Work… ..................... 37 Pia Shah Now it Has a Name 38 Erin Wearing Flora Hannay invisibility ................................... 39 Dillon Prashad Olivia Stone People 40 Matilda Park Mili Greener Fire/Home Alone 42 Emily Hallet Phoebe Parker-Swift/Katrina Davis The Bayeaux Tapestry .................... 43 Millie Carmona Chronically Online 44 Amelia Burns Joel Veldtman Baby, She’s the New Romantic 46 Ria Manvatkar James Walker House Art Competition ................... 48 Being Seen .................................. 50 Vivienne Christofides Scarlett Sanderson-Marsh My Glasses 52 Lexie Beck Robert Thomas The Invisible Man 53 Eva Green The Watcher ............................... 54 Arjan Singh Anna Howgego Visible 55 Tristan Evans Mark Wolstenholme Ivan the Terrible 56 Izzy Hassan A Level Photography ...................... 57 GCSE Textiles .............................. 58 A Level Textiles 59 3

The very understanding that they still live, elements of teeny wintry time, there she is in a runny penthouse. growing the grass green beneath the solid time. That she is here in air, mist and worrying wrinkles, makes it all okay.

Their funny hands, and misshapen eyebrows, so beautiful to me then, when I stopped to admire their presence.

Two characters in a book, ruffling our whitey wings, gods of softness that don’t dare wake staring at each other in a sort of wonder, do we know each other? Are we just specks of golddust to the other. Life bimbled in her care, nothing, the wings of a fly were there, something elegant in the haze of those longing days. we sat in eagerness as if there was no wake, no parent to redden our soul.

A youth that was in some ways more mature than any day I have come across since. discussing novels, green, squirrels and owls, Russian seagulls floating above our merry skin, howling to the sanguine sea.

Opening books, reading lines in soapy, endearing fashion to one another. with light pouring in goth-like abstractness upon rainy days. Loving is not a thing, should I forget her ways.

Holly Gordon Clark

Holly Gordon Clark

2 0 2 3 HT E P I D G EON PR I Z E FOR LIT E R A T U ER WINNER

Flo Black

SEAGULL 4

Holly Gordon Clark

HOTELS ARE FIGMENTS OF OUR IMAGINATION

Hotels are figments of our imagination

Lost people standing in bufoonishness, on a hill

Bunched up in a pool of suffocation

Swimming softly to the sequin salsa.

Hill salsa, salsa girls.

And fellow in room 58 shouldered down

The stairs in waking glory the other day

He wore his crown like a hill

Walking, utterly in a raspy beetroot-filled voice.

Menacing in verdant awe.

The lawn was green and ripe

The sun felt the ageing wilderness below

Said hello, down there.

Stamp stamping on hay bales.

Gasp at the newborn in room 23, Circle around in communal activity

Right upon the roof we climb to our night

Knights roll down the hill. Equestrians, animate soldiers. White exterior, red centre.

I am ashamed of the light I walk through

5

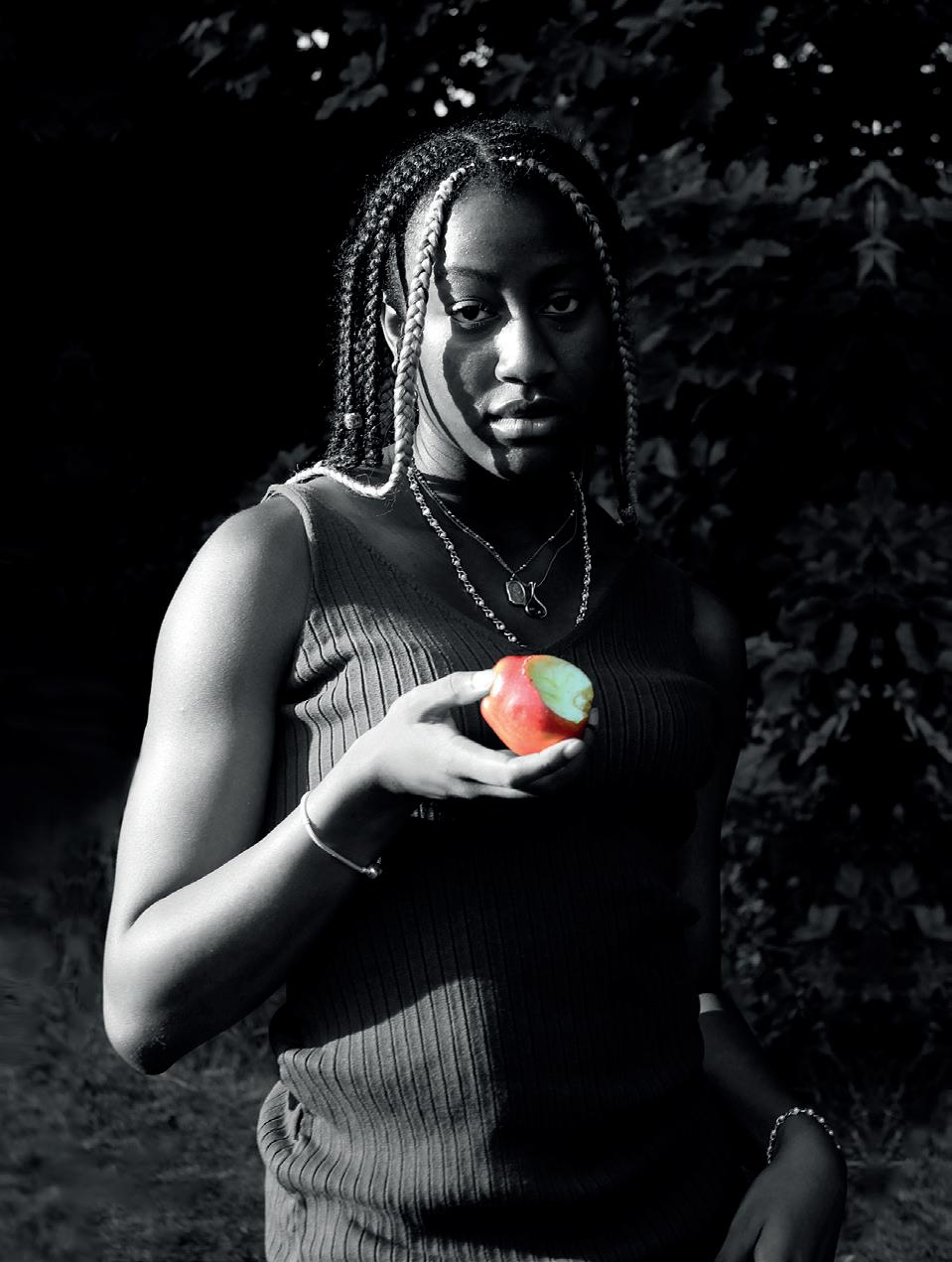

Holly Gordon Clark Simi Akingbade

I s AIthe Deat h trAehtfo i s t

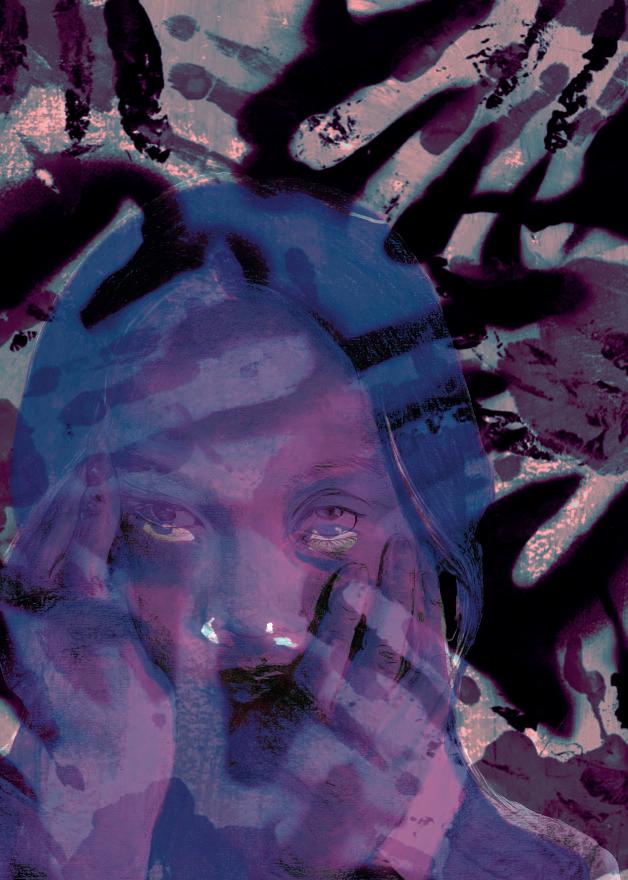

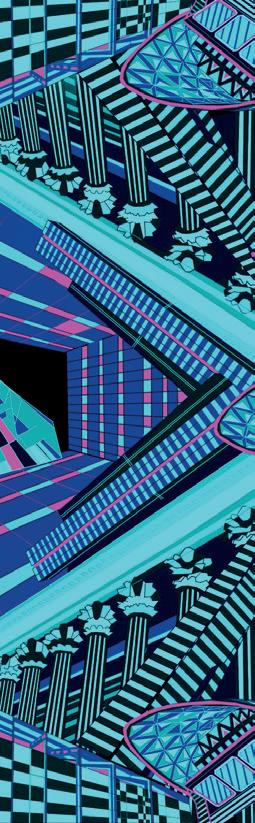

Looking at the picture opposite you would probably assume, like I did, that it was made by a human? In fact, it was completely generated by artificial intelligence on a computer.

I believe art has reached another crossroads, similar to the revolution of the camera.

I am not an art student, but I am fascinated by AI, so when I heard this story about an AI generated piece winning an art competition, I wanted to find out more.

In August 2022, businessman Jason Allen used a piece of software called MidJourney to create his piece grandly entitled, Theatre D’Opera Spatial. MidJourney is an AI algorithm trained using millions of pieces of art and figuring out how to interpret the prompts it has been given in and present it in an artistic form. MidJourney takes in a prompt, which could be a sentence or word, and produces pictures based on that input. Allen used MidJourney, then he edited the results slightly in photoshop, submitted it for a Colorado digital art competition and won. Allen is not the creator of MidJourney, he used it like you and I can, but he strongly considers himself the artist and did this as an experiment to see how well AI art can do compared to human art.

What intrigued me was the positive reception as well as the overwhelming backlash that Jason Allen received from artists and newspapers: “This is gross”; “It’s not art because it’s not made by a human”; “AI art can 100% be its own art form”. These made me think, “Is this art?” and “Is Allen the artist?”

I do not come from an artistic background, so my definition of art is probably different to yours. Before I started my research, I considered art to be something that looked nice, but I never really looked past the initial image. So, at first, I thought that without a doubt this was art because it looks visually appealing and, as I will show you, you will no doubt also see the ability that MidJourney has for creating stunning images to look at. But as I started to look at more art and do my research, I came across many more definitions of art with which to compare AI art.

For me personally, there is beauty and art in the code and algorithms that run MidJourney, and I still struggle to believe, even after studying how it works, that lines of code can produce these from just a given sentence I think of. I marvel at the creativity of the technical teams that can create such algorithms.

One recurring theme over the debate of what was allowed to be called art was that it had to be made by a human. If that is your view then AI art cannot be art - but I will ask you these two questions in response: “Is that your view because that is all that has been possible up to this point in history?” and “If say for example, Leonardo Da Vinci had access to MidJourney, would he have ignored it?”

Let me take you back about 150/200 years ago, when the camera was invented. Artists originally rejected cameras as a form of art because they thought it did not capture the “soul” of art. Over time they came to realise that photography could capture different aspects compared to a canvas, and now would you even think twice about seeing photography as a form of art?

2 0 2 3 S C H O O L A RTICU L A T I ON ES S A Y P R I Z E WINNER

Parker IS AI THE DEATH OF THE ARTIST?

Xavier Parker Regional semi-finalist, Articulation

Xavier

6

The response of artists was to paint what cameras could not capture, for example, Picasso invented and embraced the Cubism genre of art. Cubism revolves around breaking the subject down into looking at it from different perspectives but on a 2D canvas. Cameras at the time obviously could not capture objects in this form, so artists thrived as the unquestioned creators of this genre.

One possible example of something that AI generators will not be able to make is Ofili’s “No Woman, No Cry”, which was inspired by the dignity of Dooreen Lawrence, whose teenage son was murdered in a racist attack in 1993. It is painted in a naive African art aesthetic, and named after the Bob Marley song. Currently it is unknown whether AI will have the capacity going forward to laterally connect those ideas together by itself, and if it turns out that AI cannot connect those dots, then human artists will have a limitless field to explore with their art. There will also be artists who integrate AI processes into their own work and combine them to form something neither could create alone.

After asking some teachers and doing my own research, I came across the Pre-Raphaelites, a secret society of artists in the late 1800s, who believed in an art of serious subjects, treated with maximum realism and focused on mythical and religious themes which is also reflected in their literature and poetry. When I saw

‘The Lady of Shalott’ by William Holman Hunt in Tate Britain, I realized that along with other Pre-Raphaelite works it must have been used in the training of the AI. Furthermore, when Allen gave MidJourney his prompt, without a doubt, the program would have looked at and studied Pre Raphaelite artwork as inspiration to create Theatre D’Opera Spatial, and that must be considered art, because that is the same process a human goes through - finding inspiration and then creating something from it. Additionally, the more I researched the Pre-Raphaelites, the more parallels with the present day I found. The PreRaphaelites were against mass-produced art and furniture. But contrary to what they thought would happen, there is still a strong market for handcrafted furniture today. It is almost inevitable that AI art will take this same route and human made art will still be highly valued and sought-after but maybe not to the extent that it once was, and artists will have to find their place in the AI world.

Art is not safe from the impending AI revolution and will become a larger and more mainstream issue than it is now, forcing artists to adapt or lose out. I hope that after reading this, you will agree with me that this is art and deserves to be thought of in the same way as what is classically considered art and you will embrace the new technologies and all the capabilities that come with it.

Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial is a painting created by Jason M. Allen

7

No Woman, No Cry, Chris Ofili

My Star’s Light

Every day, when I fly in the sky, Staring at the comical comet zoom by, The crusty red surface,

The magenta eyes

Of the planet Mars with its crimson orbs, Round curving spheres that continue to morph, This terrible world that I continue to explore, Into a whimsical world – this is my space. I closed my eyes from the grasping stare, They blur as I visually grasp the cold air, Of living up here in this terrible place, In the whimsical world - this is my space.

As I blink, the lenient tears start to give back my vision, Every day when I grow I make more decisions, I think back to my first day in chase of this whimsical world. That is my space.

UJ N I O R C R EATIVE W R I TING CO M P E T I T I NO 2 0 2 3 WINNER Izzy Gooding MY STAR’S LIGHT

8

Izzy Gooding Joel Veldtman

I remember when we first fought together, Our scars in different places but they still meant the same thing: We were both fighting to become who we were meant to be.

This is what we both know to be true. It was our gods-given right to be men, To walk together unguarded in the sand. After triumph in battle that spring, The summer after was spent in blissful festivity. While the other boys would jeer and mess around,

We’d stand together on the balcony, Talking alone in the dusk while the moths, in all colours of the spectrum, circled around us.

On nights where I lay awake, clutching myself as if my body were a heavy-weighted burden, he spoke to me in gentle tones, the sound of his voice sweet, like medicine. He took the arrow out my side.

I’d bury my face in his silky hair, He smelt of lavender and something like love.

Friends, lovers, brothers in arms – it didn’t matter what we were called, as long as it was the two of us, Bound together by some blessed force. We go onwards together, leaving old names and rumours behind, in the dust.

9

Abbie Wynn Valerie Pang

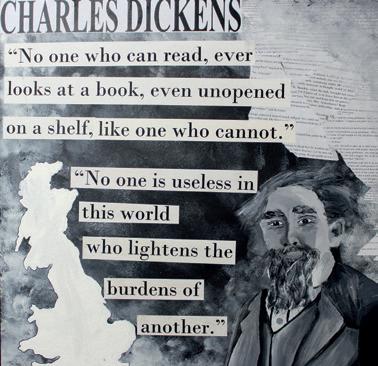

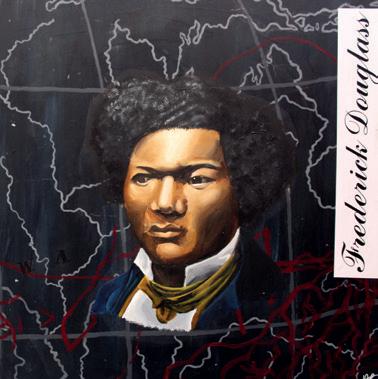

John Brown, Hero or Lunatic?

How can a man be simultaneously described as a ‘bumbling, and homicidal madman’ (Villard) and the best ‘illustration of pure, disinterested benevolence’ (Frederick Douglass)? You would think it impossible. But that is the case with John Brown, famed Abolitionist: a man who has retained the controversy around his character, centuries after his death. He is condemned for his violent methods while also being praised for his unrelenting campaign against slavery. His life poses the question of how far we, as people, are willing to go to stop evil, reiterating the ageold question: do the ends justify the means?

To understand Brown, we must understand his early life. Brown was born in Connecticut, USA in the year 1800. The USA was still young, with Brown’s own grandfather having died in the Revolutionary War for Independence. The nation had promise and Brown, like many Americans, believed that the US had the potential to stand as a beacon of freedom. But he would soon become aware of the sins of the young country. He found himself often confronted with people near him who actively participated in driving Native Americans off land, something he became increasingly disgusted by. This was not the only action of the young country he would find unappealing: when he moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, Brown was confronted with slavery – for him, the greatest sin of his nation. During his time there, he hardened his staunch anti-slavery stance, becoming increasingly belligerent that the only method of ending slavery would be through violence, in a way that seemed to contradict the Puritan faith that so influenced his anti-slavery beliefs. His staunch viewpoint made him invaluable to the abolitionist cause in the city, helping mould it into the centre of the underground railroad.

It was only during the events of Bleeding Kansas that Brown became known on a national level. Bleeding Kansas was a state level civil war that lasted until 1860 between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces, both vying for control so that the state would enter the union as either a slave state or a free state. Brown’s own prominence in the conflict came when he became the leader of anti-slavery forces in the region where his brutal methods came under criticism in the aftermath of events, such the Pottawatomie massacre, where Brown and his men killed five professional slave hunters in the night. But the nation also noted Brown’s bravery in the conflict, with him quickly becoming a hero in the eyes of the northern free states, having guided his men to safety in multiple instances when he was outnumbered by anti-slavery forces.

If Brown’s legacy ended here, he would likely be viewed in a universally positive light, only slightly tainted by the violence he stood by in the name of freedom. But Brown was determined his work would not be finished until he was either dead or

Stuart

Stuart

slavery had been abolished. He started to travel around the northern states to rally support for what would be his boldest action yet; he asked for money and volunteers, both of which he got, although not as many as he may have liked. He made his plans known to other prominent abolitionist leaders of the time and these were met with mixed reactions: Harriet Tubman helped him gain volunteers, while Frederick Douglass tried to dissuade Brown from his plans, calling it suicidal. But Brown continued undeterred and in late 1859, Brown led 21 men in a raid, attacking Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The raid met initial success, with Brown’s forces successfully gaining access to the Harpers Ferry Armoury and rounding up hostages while spreading the news of liberation to slaves. This success was short lived as the people of the town soon started to fight against Brown’s anti-slavery crusade; they shot at the group from rooftops, pinning Brown and his supporters into the local fire engine house. Brown realised that they would not be able to escape and that a company of US Marines would soon be arriving, so he tried to send his son and another of his supporters to safety, but those who went out waving a white flag were shot by the enraged locals, resulting in the death of his son. The next morning they found themselves surrounded by, not the locals, but a company of US Marines. They offered Brown the chance for surrender, telling him their lives would be spared if they did. But Brown was unrelenting, stoically answering, “No, I prefer to die here.” The Marines then stormed the building that Brown’s forces had used as a safe haven, capturing Brown and his supporters.

Tried in Charles Town, Virginia, he was charged with the murder of four white men, inciting a slave insurrection, and treason. The trial was a week long and gained national attention, increasing tension between the south and north as the South saw this as proof of the hostility of northern states. The Jury found Brown guilty on all accounts after a 45 minute deliberation. He was sentenced to be publicly hanged. While walking to the gallows he passed a note to his jailor; written inside were his last words, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

Brown’s actions and death were one of the main causes of the American Civil War, where slave states seceded from the union in fear of the north withdrawing their right to keep slaves. It resulted in the death of over a million people. It is impossible to know whether, without Brown, slavery would have ended peacefully, or would it have lasted centuries more? All we can say for certain is that Brown, disgusted by the sins of his nation, took to arms, risking everything he held dear, in his belief that the freedom of men should take precedent over all.

Brown, disgusted by the sins of his nation, took to arms

10

James

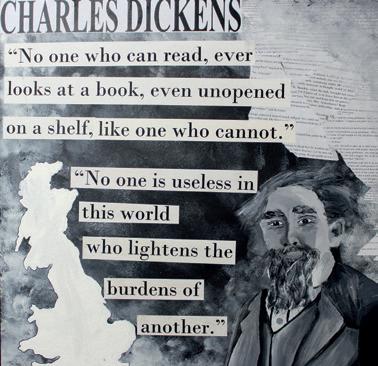

Scarlett Sanderson-Marsh

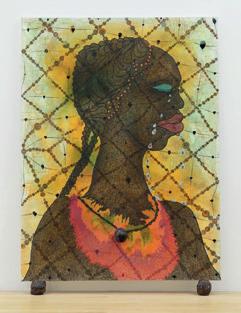

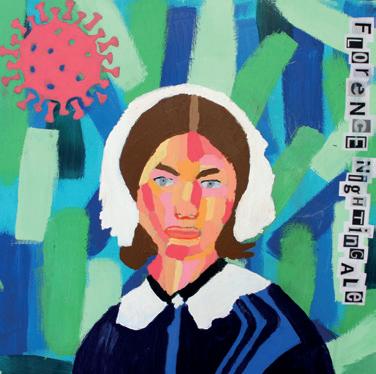

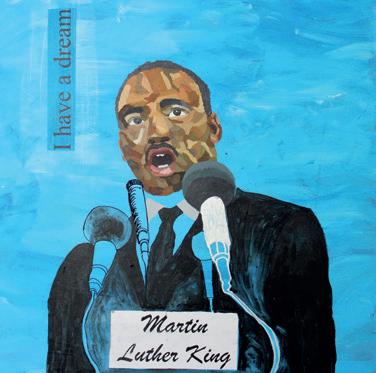

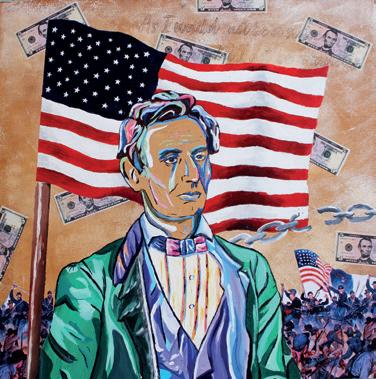

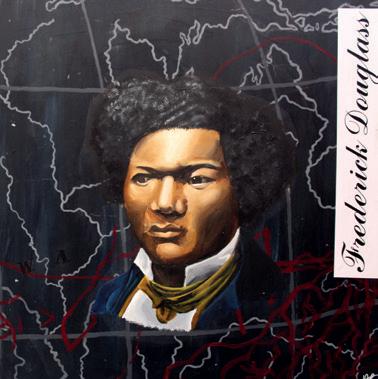

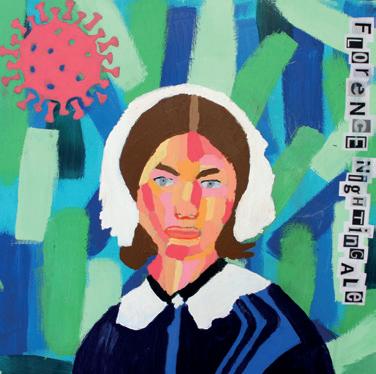

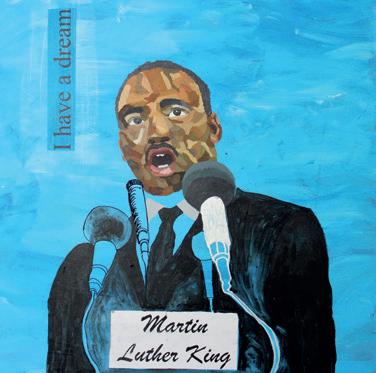

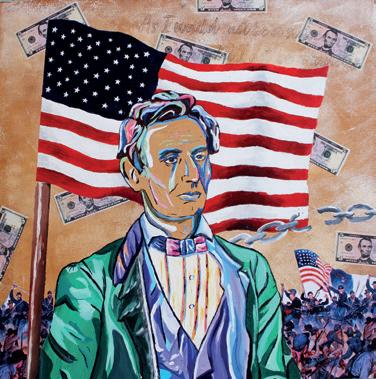

Third Year Historical Portraits

TIFFANY CHOW

KANGSATHIEN

POSH

AKELE

LYLA BEUKES HONOR

JOJO ALTEIRAC

REBECCA BONNIFACE

Flash a polite smile as you enter the ballroom

The ceiling is high: untouchable masterpieces

Frozen, unmoving between overarching pillars

Holding up the hefty burden Of society’s demands.

The grand occasion is attended by just as many debutantes

As there are ‘eligible bachelors’

Unsurprisingly, one approaches

He speaks presumptuously, his manner amiable

He is – albeit charming – an undesirable suitor, Or so your mother whispers as she passes by And so, you graciously dip your head

In erroneous apology.

Tell him your dance card is full

Helplessly wave excessively decorated material

Dangling from your satin shielded wrist

Even though you know all too well

The quadrille and the waltz – supposedly his favourite –Are occupied by vacant spaces.

The rest of your night is the same as the many others

You have wasted this season

Mingling with the numerous onlookers

Courteously turn down dances your mother disapproves of And cordially – or rather, dutifully – take to the dance floor

Embossed with the family crest of whoever’s residence you are in. (it seems, the copious balls you have attended in the past weeks have not eased your weary memory)

You engage in polite conversation

As your dance partner spins you gracefully; He tells you of his days in Eton (or was it Oxford?)

Your mother says he will make a wonderful – heaven forbid – husband-to-be.

You are told of the wondrous experience

That married life will be.

A genteel household; you will bear children

And live in undisturbed harmony

With a man you may meet here.

Never mind the plentiful dowry that make

Your prospective nuptials all the more enticing Or the unfathomable fame

Your family name could bring him.

Look up once more at the painted canopy

Cracks form between the angels, the gods

Breaking apart the billowing ribbons and astral clouds

You long for a day where you are more than a fanciful doll

A future where your voice rings clear, where all are equal

But just for now, sit pretty in your luminous dress

Be alluring, play dumb and do as you are told.

This way of life is so fragile, so exclusive

This society, so elegant yet undoubtedly doomed to fail

Is hanging by a thread, ever so Precariously.

Kate Fan Gabby Toone

12

Sight

Sight

One of the fundamental aspects of our lives

Without it, we’re lost

Lost in eternal darkness

With no way out

But what if you couldn’t be seen?

No one would notice you

You’d be all alone

As you’re still lost Lost in eternal darkness

With no way out.

Liam Kitavujja

Ava Floyd

13

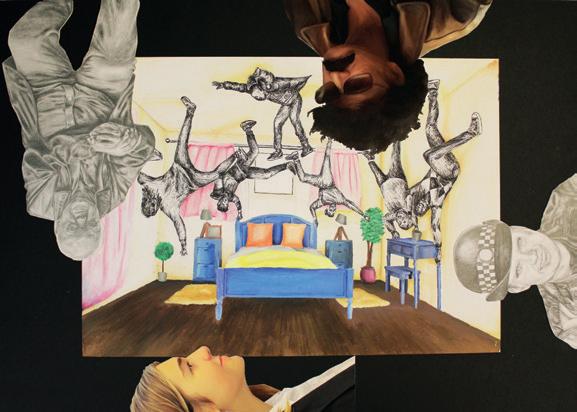

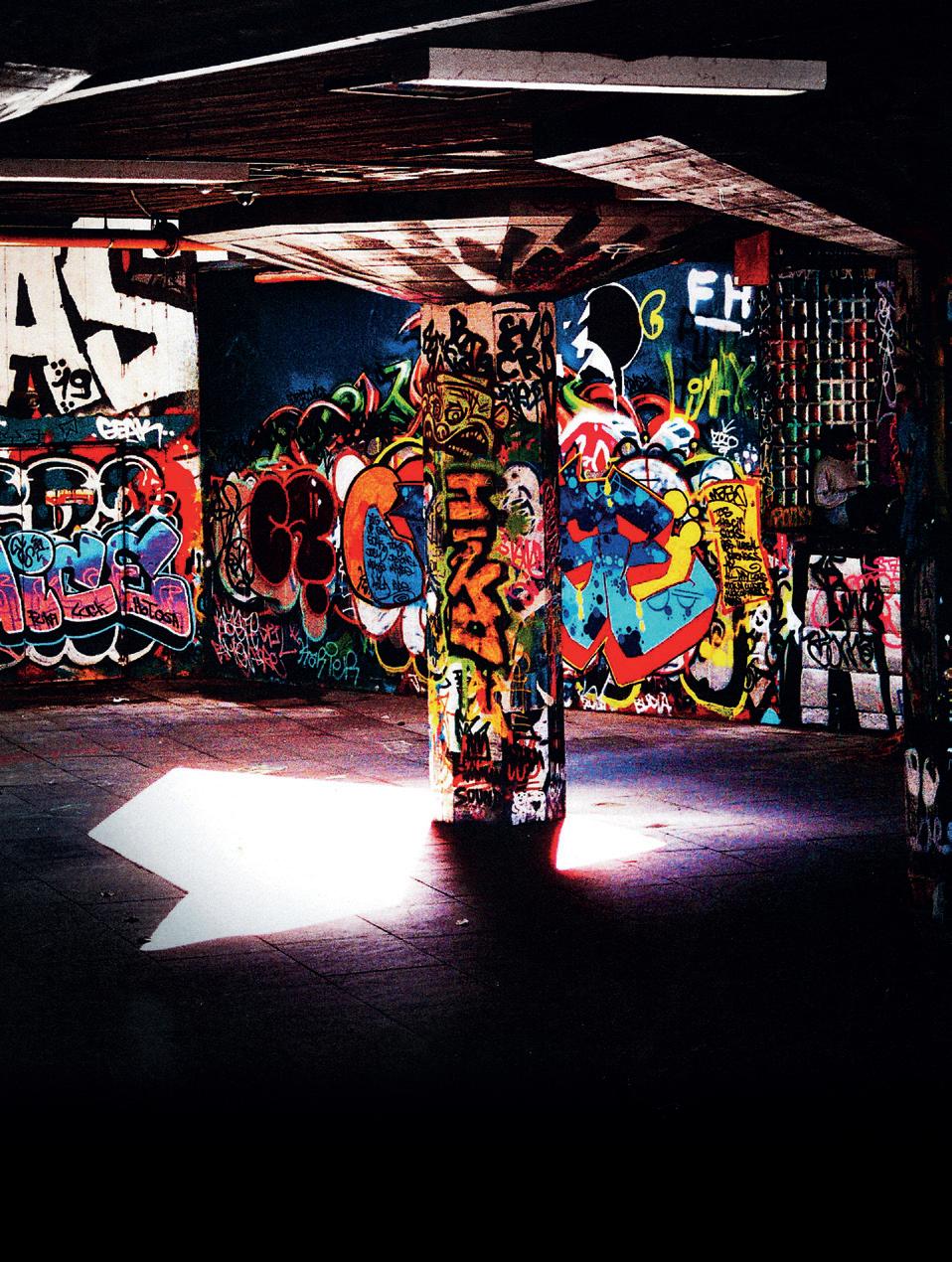

‘Spray Paint Dress’

The

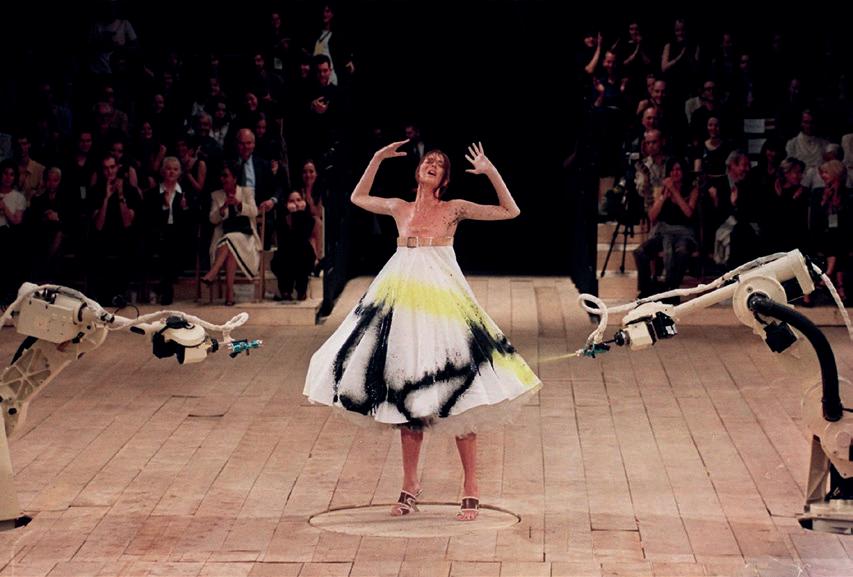

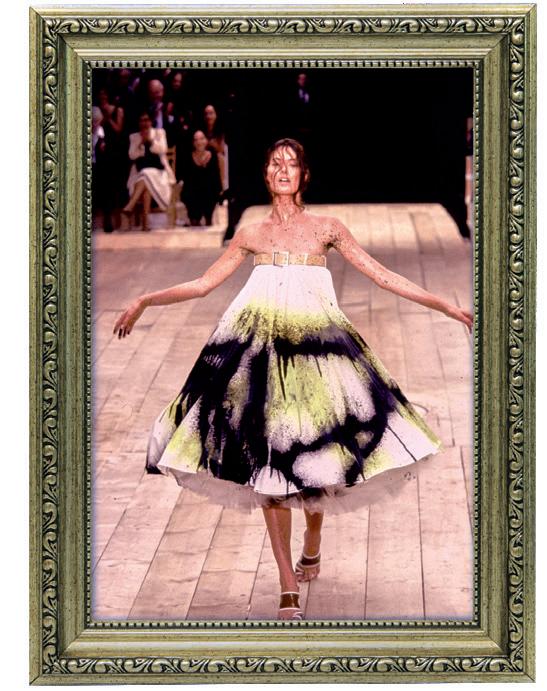

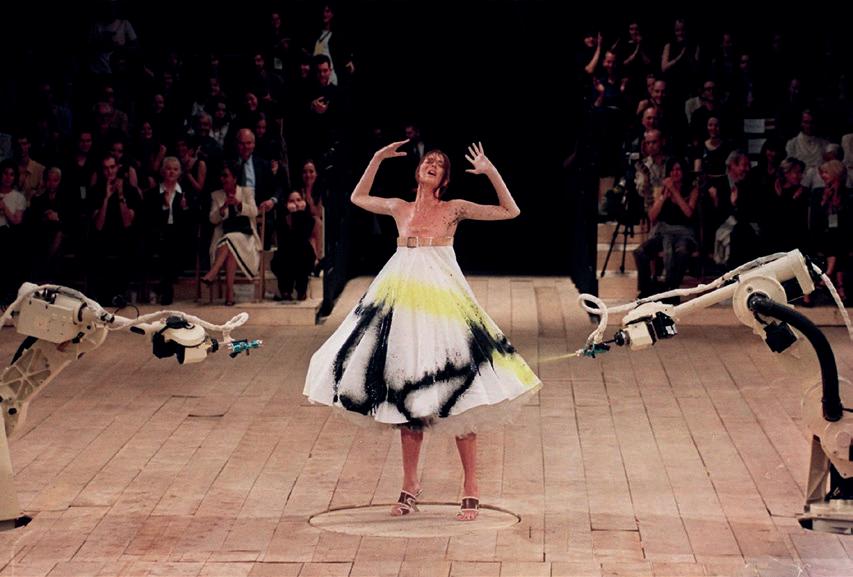

no.13 show was Alexander McQueen’s 13th show created for Spring/Summer 1999.

It rewrote fashion history.

The collection was an homage to the arts and crafts movement which was one of the most prominent fuels for McQueen’s designs. Lots of the looks were inspired by the workshops at Queen Mary’s hospital in Roehampton which created prosthetics for soldiers in WW1. This was seen in the show through asymmetric belts, corsets and harnesses. The accessories and, predominantly, shoes bear a slightly orthopaedic resemblance which stems from the work McQueen did with amputees. Just a few days prior

to the show, McQueen guest edited the magazine ‘Dazed and confused’ in which he put Paralympian Aimee Mullins on the cover wearing metal sprinting legs. Mullins opened the show wearing a hand carved wooden leg which was shaped to match the boot she was wearing.

However, this show is so infamous because of the spray-painted dress finale. At the end of the show the supermodel Shalom Harlow emerged onto the centre of the stage where she halted on top of

a turn table surrounded by two spray paint robots which are typically used for painting cars. McQueen and his team had programmed the two robots to manoeuvre around Harlow whilst painting her with black and yellow paint. Harlow is a trained ballerina and used her dance background to centre herself on the turn table as she tries to protect herself from the robots and to prevent herself from falling off the rotating table. Her actions were unplanned, and she used her intuition to respond to the violation of the Robots.

James Walker

14

Once Harlow was painted and the robots had retreated to their starting position, she stepped off the turn table and walked forward to the audience and cameras in a disoriented manner, presenting herself as a piece of meat that was violated. Harlow described the moment to a journalist that she “staggered, up to the audience and splayed myself in front of them with complete abandon and surrender”.

The spray paint dress is compiled from a white tulle underskirt topped with white cotton muslin along with a belted neckline. When I viewed the piece, I was wowed by the power and emotions it could evoke from such a simple design. The paint is so expressive and violent which seems almost impossible as they were made by machines. The movement and shape of the dress also presents an air of elegance as it flows off the model highlighting her neckline. The nude-coloured belt however contrasts the graceful feel and, once partnered with the spray paint, conveys a more industrious mood.

In this piece the robotic arms embody the idea that technology is threatening especially once it bears human like characteristics and expression. The humanisation of the robotic arms has been likened to Edmund Burke’s idea of the Sublime. This concept is that an audience can be transformed from their reality to a psychological world of the knowable and unknowable. This follows the concept that a thing can be unsettling and uncanny. In this collection and piece McQueen creates a path for his audience through unsettlement to the sublime. However, this sublime is not one of nature but rather the sublime in the uncanny force of the machine age. The robotic arms convey both the magnificent and the abnormal by moving in a human and intellectual way. The machines can be seen to sense Harlow on the turntable which lures the viewer in with an ignorant curiosity before attacking Harlow which launches the audience into a state of shock and discomfort as the arms appear to maliciously attack the model. The duality of the numb presence and intelligence of the robotic arms create a fog of anxiety which descends onto the onlookers.

The overarching theme of unsettlement was even presented in the shoes which

had the heel located in the middle of the shoe as according to model Emily Gold, McQueen “placed it there to give the illusion of a woman who could fall at any moment”. On the contrary to this, Shalom Harlow personally felt that the act was symbolic of quite a sexual experience. She felt that it told the story of exploitation from vulnerability and this sense of forced surrender. Harlow may be on to something as the piece can be likened to a sexual climax as the robots fling themselves back in relief.

integrate technology into art and fashion in a non-threatening way. Designers like McQueen have used technology to create artworks. This poses the question whether their example can be followed and whether more artists should be using machines or digital resources to make extraordinary pieces. In an increasingly advanced society, we are seeing art stem from more untraditional backgrounds. Quite recently the growth of NFT’s1 has made us question what we consider art. In this fast-moving world

For the wider world this piece should be remembered and respected as it stands as a warning for the slippery slope we tread when we develop technology. It states the cautious nature we should adopt when making robots and nonliving things which act like humans. Despite this it could also be said that this piece is a symbol of how we can

it is important we do not get hung up on old concepts and that we also move with change. Therefore, I feel that McQueen’s ‘spray paint dress’ is also a message telling us and challenging modern artists to keep up and not get caught up on what is comfortable but rather push ourselves into the unexplored and new.

1 NFT – Non-fungible token 15

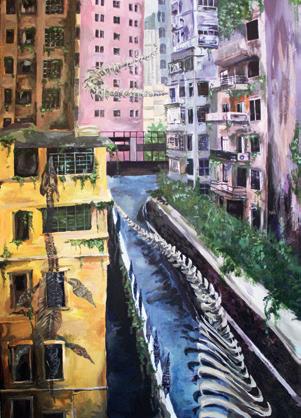

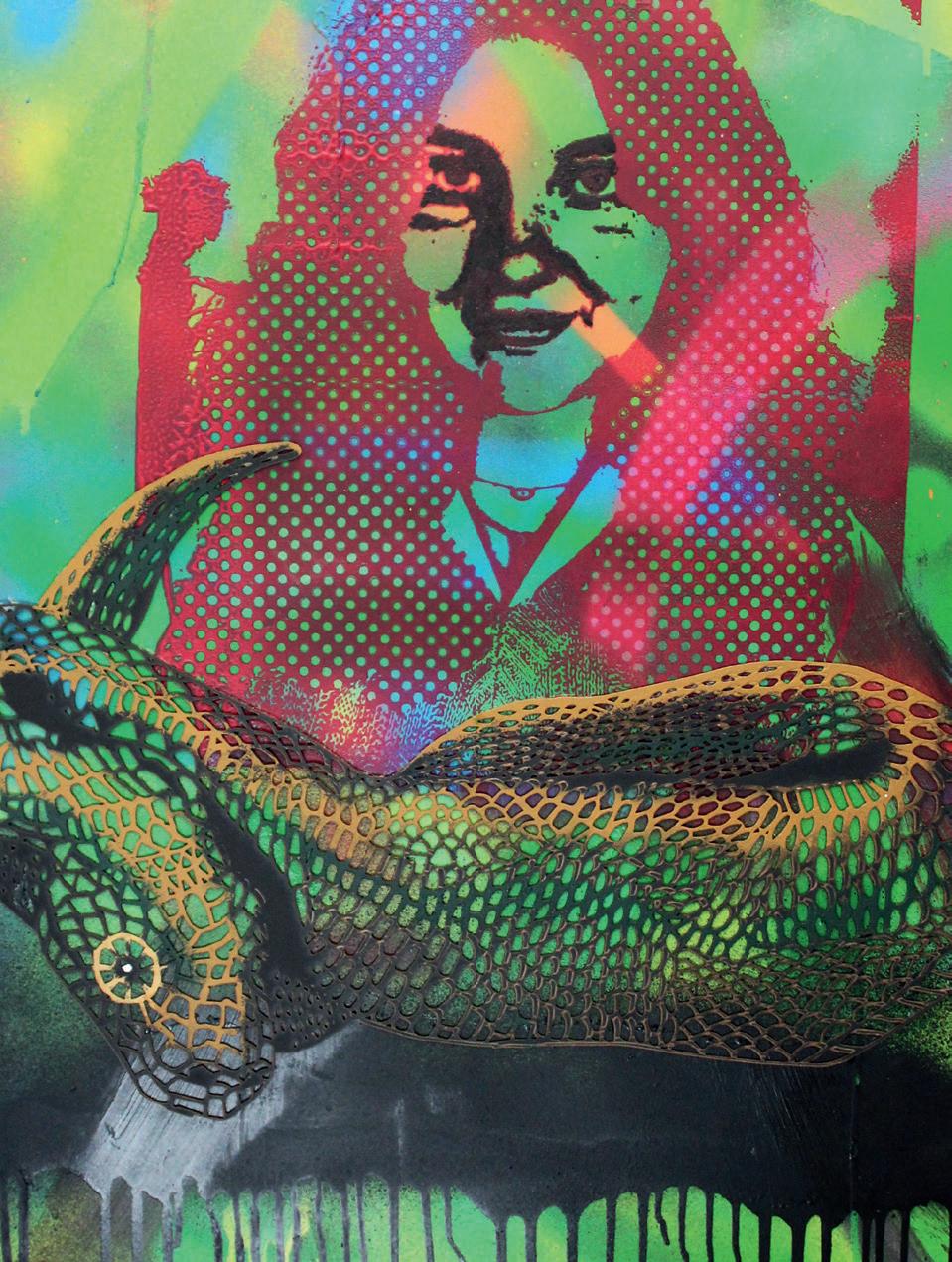

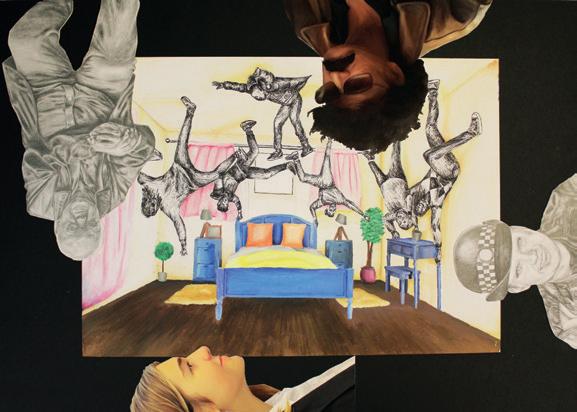

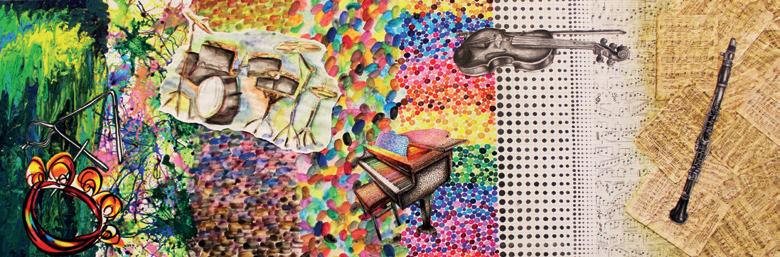

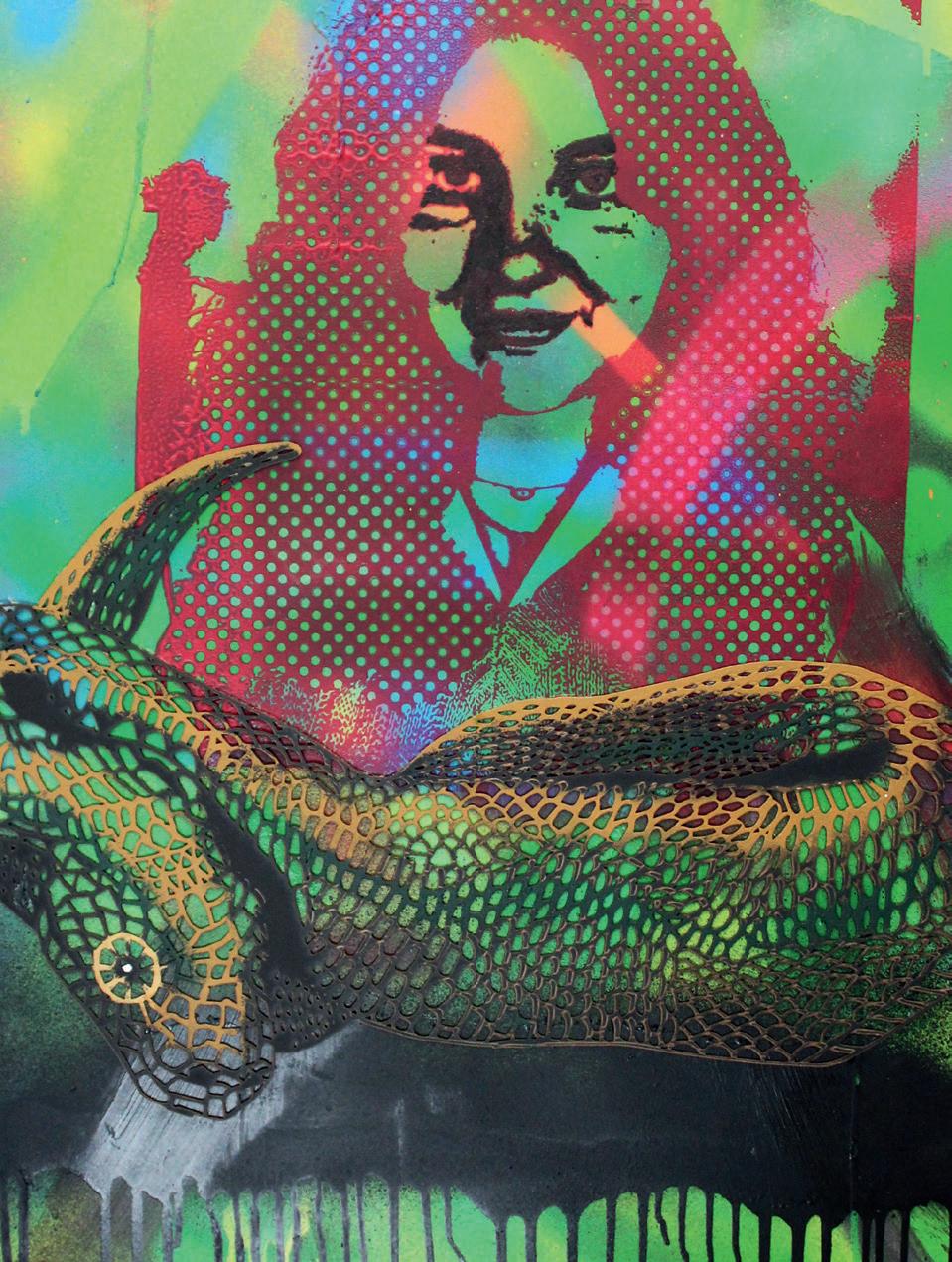

GCSE Fine Art

IZZY YOUNG

IZZY YOUNG

ALICE KEYWORTH LEANE BEUKES 16

LILY WOODWARD

SYDNEY MEI

SIMI AKINGBADE

SYDNEY MEI

SIMI AKINGBADE

ANNA HOWGEGO 17

RIANNA PATEL

THE CLASSICS REVISITED: Exploring Greek and Roman Art at the Louvre

We recently visited the Louvre on a school trip to Paris. While I was in the cité merveilleux, I (as a classics student) was particularly fascinated by the artworks from Ancient Greece and the Renaissance Period and how classical art has changed over time periods.

Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices by Paolo Veronese resides majestically in the Louvre. Jupiter, (the Roman God of the sky) was seen as the King of the Gods by the citizens of Greece and Rome, where he was known as Zeus. The artist was born in 1528, Venice, Italy – here he gained his nickname of “Veronse”. The artwork, in the Mannerist style, depicts Jupiter throwing thunderbolts at the five vices banished from the heavens. The Vices are pictured falling after Jupiter strikes them. The Five Vices are: Wrath, Lust, Greed, Gluttony and Pride. Jupiter is said to have thrown thunderbolts at other gods if they posed a threat to Mount Olympus. He threw a thunderbolt at Phaethon (a demigod) because he had lost control of his father’s chariot (which brought the sun in the morning and retrieved it at night). When I see this painting, I feel as though I am witnessing a battle take place – I am in awe of the contrasting colours of the pastel blue sky and the browns. Jupiter’s angel wings are juxtaposed with the raven on the darker side of the painting, symbolising good against evil.

Many of Veronese’s paintings include vibrant colours as we see demonstrated in The Wedding at Cana (painted between 1562-1563 and also displayed at the Louvre) – this is a religious artwork which depicts the biblical story of the Wedding at Cana and is also painted in a Mannerist style. Both paintings are from the High Renaissance period, in which human figures were emphasised alongside ideal proportions – the optimal colour and luminescence are seen to be unnaturally elegant; artwork from this time was not seen to be a realistic representation of people. I found

Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices exceptionally inspirational for my own writing and art.

Winding back more than a millennium from Jupiter, comes a prestigious Venus. I had been wanting to see this sculpture for some time and, as one would imagine, it was worth the wait! The Venus de Milo is carved from Parian marble, and represents the Goddess of beauty, Aphrodite. It was sculpted between 150 and 50 BC by Alexandros of Antioch during the Hellenistic period. The statue was found in pieces on the island Melos then brought to Louis XVIII (who donated the reconstructed version to the Louvre in 1821) – although the statue was in a standing posture, the arm was never found. I believe that this makes the statue even more valuable as a it emphasises how important it is to preserve our works and how dignified the sculpture is, after enduring years of being broken.

Another piece made during the Hellenistic period is the Winged Nike of Samothrace. The sculpture shows a winged Goddess, Nike – the goddess of victory – wearing a delicate fabric draped across her lower torso. The Winged Nike of Samothrace is seen by millions of visitors a year as it graces the top of the Daru staircase in the Louvre. The sculpture is named after the island where it was found in the 1860s by Charles Champoiseau. Champoiseau uncovered the statue of a female body with white feathers draped in a robe and transported the fragments to the Louvre. In 1891, Champoiseau came to Samothrace again to try and retrieve the Nike’s head; this was unsuccessful and today she still stands headless and magnificent.

Overall, my visit to the Louvre helped me appreciate how artworks have developed through different time periods and I was able to develop my understanding of mythological stories of Venus and Jupiter. Above all, I learned how the treasures of the art world can be perfectly imperfect.

Kayla Prashad

Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices, Paulo Veronese

Venus de Milo, Alexandros of Antioch

Kayla Prashad

Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices, Paulo Veronese

Venus de Milo, Alexandros of Antioch

18

The Winged Nike of Samothrace

Note on text: Limerence is the psychological state of being obsessively infatuated with someone, usually accompanied by delusions or a desire for an intense romantic relationship with that person and to have one’s feelings reciprocated.

My love for you, so tender, so pure, To be with you, everything I will endure. But now I look at you, yet you don’t look back, The love in your eyes that was there, you now lack. Don’t break my heart like this, it is you I crave, If you leave me, I’ll lay in my grave. I must be with you, feel you, smell you, breathe you, I’ll do anything to be with you, through and through.

But I see you look at him with such desire, such lust,

You are mine. You are what keeps me going. You look after me and pledge to do so until the day I die.

I listen to you. Sometimes I doubt you. But your deafening message draws me on like a magnet to metal. Your influence is irresistible.

When you hurt, I hurt. We are one. I want to block out the ache, but it lingers long and pulls me into darkness. The warmth you give is like a welcoming hug. It keeps me warm in the coldest of times and lifts me up into light.

I owe you everything, my heart; My love, my joy, my pain, my life. Don’t fail me, heart. I will always be with you.

When I close my eyes at night, i feel crushed. I see you holding him, passion burning in your eyes, And I watch from a distance, begging the sun to rise. My heart aches for you my dear, anything I’ll sacrifice, And I hate to think that I alone will not suffice. And my dear darling, this is not a threat, But next time you look at him, I’m sure you won’t forget. Blood will pour from his eyes so he will look at you no more, And you and I will be in love just like before, And if there is any other man that catches your eye, I’ll get the impression that something is awry, My darling angel, look at me, just me, Love me, love me, Love. Me.

Izzy Hassan Bailey Carpenter

19

Ammara Khan

Bella Beadle IPHIGENIA AT AULIS REVIEW

Euripides may be a long dead poet but he came to life this term in Caterham as the tragic story of a Father’s betrayal of his daughter took the audience on a classic journey of pity and terror.

When walking into the auditorium, the first thing you noticed was the incredible set of an airport. The simple use of black contrasting with white, created the stark, industrial setting against which the tragedy would play out. The audience were immediately met with a

motion fighting, created a great dramatic moment.

The costumes were creatively designed and chosen for this play; instead of going with traditional clothing, many of the ensemble costumes were up to date, helping make the characters more relatable to the audience. The monochromatic colours of the tourists, the air stewardess outfits and the combat uniform of the army, created unity in each of these ensembles, which then helped to contrast with the lead characters. The officer uniforms worn by Agamemnon and Menelaus, elevated their importance; the long red coat and

was at a professional level and her use of emotion was incredible, especially when showing a mother’s love for her baby; her confrontation towards the end of the play was extremely powerful. Sophie’s Iphigenia was so pure and well executed, and her last monologue was heartbreaking when emoting her willingness to die. Sam’s portrayal of Achilles was excellent, his comic timing getting him many laughs from the audience. It must be said that this show could not have been done without the ensemble, who worked together effectively to create outstanding parts of the play. The ensemble girls also added great comedy to parts of the play – such as their swooning, their hands on their chins, over Achilles.

Achilles was excellent drumsticks that lit up brightlycolouredjumper elevated their importance

movement sequence to a contemporary piece of music. The use of modern music was used during the whole show and helped breathe a new life into the play. The opening set a very a high standard for the rest of the play, which was most definitely met from every aspect of the cast and creatives:

The tech team must be credited with their amazing ideas and execution of the whole show. Imaginative lighting was used for every key moment such as when Agamemnon and Menelaus were talking about a secret, the lighting directly reflected this by becoming slightly dimmer and warmer. One of my favourite moments of the whole play was the fight scene with red lighting followed by white flashes of light. This, combined with slow

blue dress worn by Clytemnestra, created a mature and motherly character; and the dungarees and brightly coloured jumper worn by Iphigenia brought in a sense of innocence not seen in any of the other characters. Her white wedding dress further added to this idea of purity, something seen all the way through to her death.

The whole cast was incredible and brought different aspects to the show, with Tristan (Agamemnon) and Max (Menelaus) having great chemistry and using clever and concise acting choices to portray their characters. A great moment in the play, was the use of the ramp to highlight the power dynamic between them. Anna’s (Clytemnestra) performance throughout

Another brilliant moment was the use of drumsticks that lit up from the ensemble to make a huge militaristic ensemble moment with the sticks being struck in time with the well-chosen song ‘Run Boy Run’.

At the end of the play, we see the characters leave one by one as the music swells. Clytemnestra is left alone on stage and we see her find a bloody veil as the lights go down. The last thing heard is a baby’s cry as the lights cut out and the audience are left with a sense of poignancy. This, for me, was a nearprofessional play and everyone should be extremely proud of their contributions to it; it highlighted the talent there is throughout Caterham – roll on the Lightening Thief!

Sam’s portrayal of Achilles Come Die with Me: we see her find a bloody veil the lights go down

20

jumper The Miracle at Aulis The Miracle at Aulis

The sun glistens on the sacrifice’s neck –And what a sacrifice she is.

She is just a child, and in the harsh light of the temple it’s hard not to notice

The way her fingers tremble as she fiddles with her wedding veil.

The determination in her eyes

Is a size too big

was excellent veil as

And it shows –

She’s wearing second-hand courage, Borrowed from the echo of the bluster of some long-dead king. A blossom drops from her flower crown onto the floor and her resolve falters

As her mother stoops to pick it up and tuck it tenderly behind her ear.

Her father looks away. She is a hero, a soldier reassures him. But she is just a child.

Her mother reaches for her but finds only empty air: It is her father who takes her hand, Is is her father who leads her to the altar, Is is her father who raises the knife To the sky.

The temple pales against her blood.

The general stands strong. Some soldiers mutter, restless, Impatient for the disorienting cool of a breeze on the face. Others lift hopeful faces to the sky. A few avert their eyes

From the mother staggering backwards, hand clamped over her mouth.

Rows upon rows of jagged spears rear aimlessly as the men file out of the temple.

Artemis, goddess, is this what you wanted?

Artemis, goddess, have we done what is right?

Artemis, goddess, where is our sign?

Goddess? Are you there?

The army reaches for a miracle but finds only silence –And then, in the distance, the reeling wolfhound-howl of an eastward wind.

What have we done?

Steel-toothed war shall be their miracle, Two cities falling perpetually Upon nameless blades

In the name of that mangled whisperer Glory. And at the end of it all, they dig their graves as one, To share a silent tomb.

Was it worth it?

A burning nation shall be her legacy. They say she sups with the gods, But where is her altar? They worship on the battlefield, Sprawled out, noses pressed close to the dirt, And the libations they offer there are bitter – battle cries and a hollow triumph Spilling out onto the dust.

Each martyred soldier her pious devotee: Their sanctity lies alone in decay, in the vultures taking holy communion

From the arid rot of their skin. No graves for them; instead a counterfeit peace

Spreadeagled on the sand. No respite, never again the happiness they once knew –Not when their resting-place still blisters and quakes Under the pounding of feet long-gone. They reach for a promise but find only the merciless ground. Now forward – their ghosts march future-wards, to watch how blood once more turns the sand to mud, And as the battlefields of Troy thrust their greedy hands through time

A small girl reaches for a rifle.

21

Hettie Nolan Harry Evans

Verses of Migration

In 2022, it was estimated that 1.1 million people immigrated to the United Kingdom. To say this is a large number is an understatement; with this number comes the overwhelming feelings and questions of identity, ostracism and isolation. I wanted to explore this more – specifically how individuals with first hand experience of these emotions expressed them through their writing, particularly their poems. I wanted to obtain a broader understanding of how racism and xenophobia can affect a person’s identity, and how it later shapes them. To do this, I will be looking at three poets: Ali Alizadeh, Muna Abdulahi and Daljit Nagra.

Ali Alizadeh is a first generation immigrant, who was forced to migrate from Iran to Australia, where he was met with an extensive amount of racism, and felt quite isolated among his peers. He had a passion of literature when residing in Iran and continued to pursue it in Australia, where he would often use his personal experiences and trauma as inspiration for his poetry. One of his most famous poems, Immigration, highlights the positives and negatives from immigrating to another country. Alizadeh starts off the poem by touching on the advantages of immigration – essentially to escape war and the “onslaught of religion.” He emphasises the idea that immigration is vital for some, especially for those at risk of death – “I’ll tell you why. To survive…”. From this, we can infer that Alizadeh is drawing upon his own experiences of living in a war-torn country and abiding oppressive laws. The speaker seems to be relieved by escaping and having the ability to “discover the basic joys of being.”. In contrast, the subsequent stanza sheds light on the disadvantages of immigration. He discusses the ostracism and alienation that immigrants feel regularly, and how they are “marginalised to the point of disappearance.” The speaker feels they are being denoted purely by their appearance, rather than their achievements and aspirations in life. As before,

Anoushka Gadkar Mili Greener

Alizadeh draws from his own experiences from immigrating to Queensland, as he said that he has experienced a vast amount of racism and seclusion growing up there. In the final stanza the speaker concludes that the positives weigh more than the negatives. In the last line, he summarises his fickle mind stating that he would recommend it to both his “dearest friends and loathsome enemies,”. His dilemma is this: escape from war and grief versus the emotional trauma that they face. He concludes that whilst he escapes brutality, he is met with brutality, which is reality for numerous immigrants.

Muna Abdulahi is a Somali-American writer, who is the daughter to refugees. Her main works are regarding the hopes and aspirations that immigrants are forced to dismiss, when migrating from one country to another. She explores themes of belonging and identity, but more importantly, how their stories have been devalued and burned away. The Unwritten Letter from my Immigrant Parent, explores the perspective of one of her parents. Throughout the poem the parent heavily criticises the American Dream, particularly the lack of support and embrace they received when arriving to America. When Abdulahi states she wants to be like them, their “heart dropped to the floor.” The parent does not want their daughter to experience what they did: the extreme isolation, alienation and racism that they faced when immigrating to a country which doesn’t respect them, or “doesn’t even know how to pronounce you properly.” The parent tirelessly works to try and fit into the social norms of this country, however, there is a huge lack of reciprocity from America’s side, as it refuses to even try and accept or understand their culture and belonging. Still, the parents remain optimistic; they want their daughter to experience what they never could, and take advantage of it – “speak, learn, jump, fail, fall…”, as “the best of me lives in you / So speak.”

22

The speaker feels they are being denoted purely by their appearance, rather than their achievements and aspirations in life.

speak,learn, jump,fail, fall…

Finally, I wanted to look at Daljit Nagra, a second generation immigrant. His parents were born in Punjab, and migrated to London in the 1950s. Nagra was born in 1966, in West London, and grew up in Sheffield. In 1988, he went to study English at Royal Holloway. His most notable work is Look We Have Coming to Dover, a collection of poems which shed light on the immigrant experience, from the perspective of the first generation, their children and grandchildren. The titular poem won the Forward Poetry prize for the best single poem in 2004. The title is grammatically incorrect, which is done on purpose to lightly tease his own people. It would be interesting to compare this poem to Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold, which Nagra alludes to. The original poem uses nature to reflect his melancholic feelings about the future. It talks about universal love on a more spiritual level, and is very lyrical; the speaker describes Dover Beach to be mesmerising. In contrast, Nagra subverts this idea, to depict the coast of Dover to be unpleasant. While Arnold describes the beach as “Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay. / Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!”, Nagra describes it as “diesel breeze ratcheting speed into the tide,” and “brunt with gobfuls of surf phlegmed by cushy come-and-go tourists.” The grotesque imagery used in the latter poem demonstrates the hostility that immigrants and foreigners are met with from locals. To support this, the language he uses is very bitter - “swarms of us, grafting in,” “Stowed in the sea to invade…”. The use of the derogatory verbs ‘swarms’ and ‘invade’ are presumably what racists feel towards immigrants or people of colour. The poem itself, at first glance, seems to be quite positive, however, on closer analysis, it really displays the contempt that people feel towards them.

Reading and analysing these poems has been so insightful to me; it allowed me to gain further knowledge into the identity of these first generation immigrants, whilst also relating it to my own experiences too. It is fascinating and inspirational how so many of them would have to adjust their perspectives to the new country they migrated to, whilst feeling a vast amount of isolation.

23

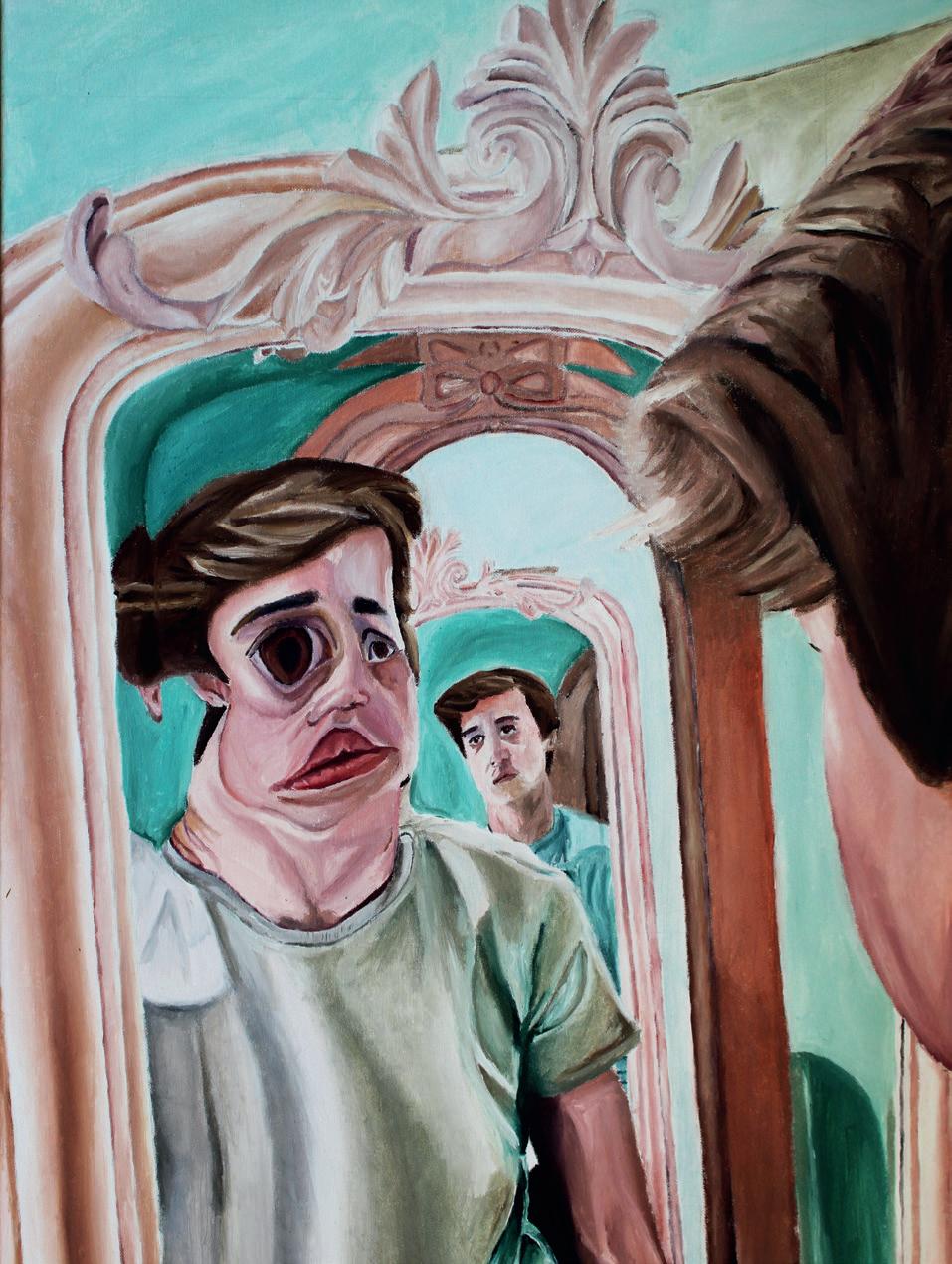

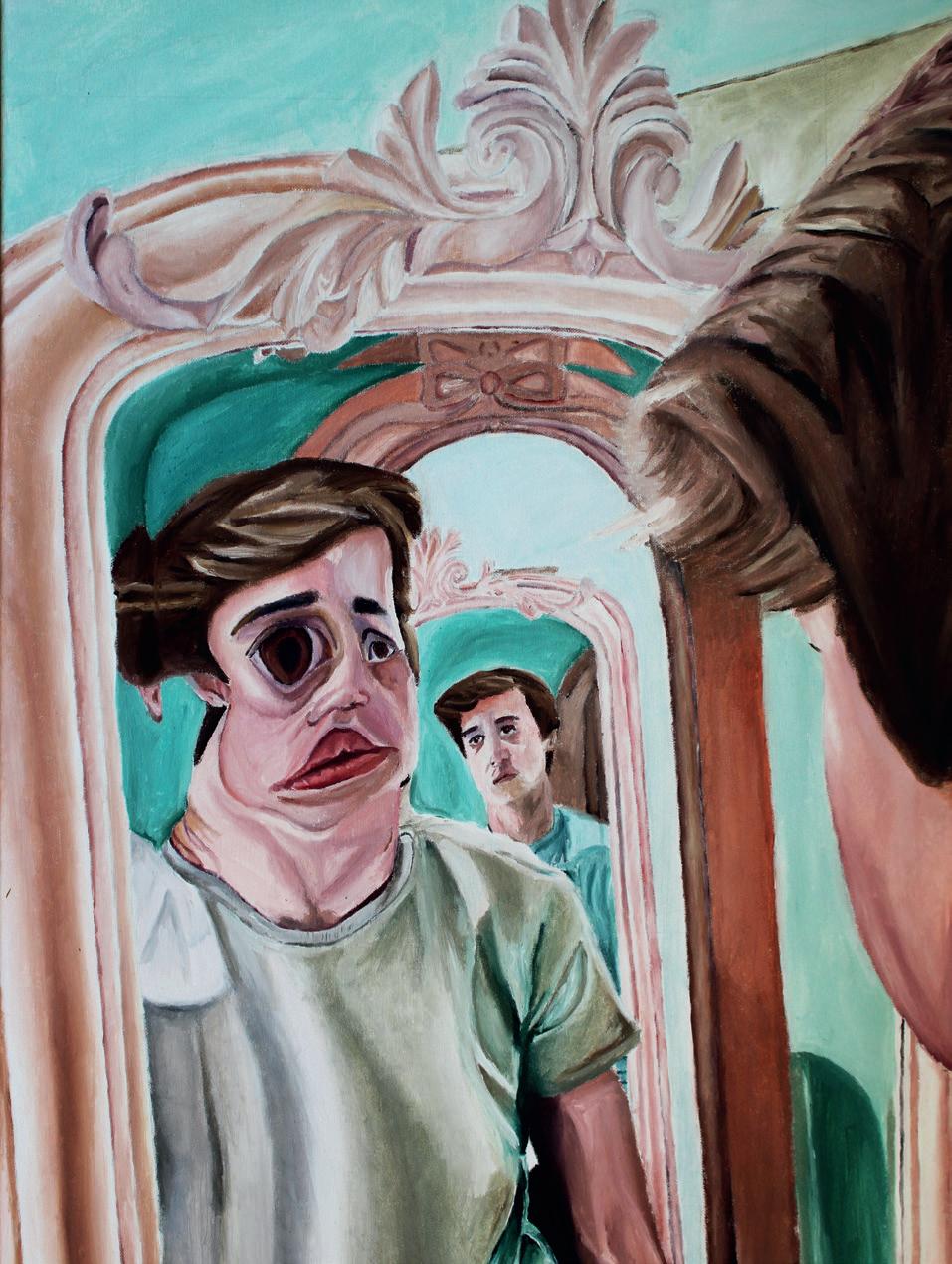

surprise! you’re wrong. the face you wear doesn’t belong to you, but let it fester there for a little longer. you’re not here.

‘i am,’ you mumble, but you’re wrong. watch the blindness smother you. you just hang there, crooked.

i tell you that you’re doing it wrong, i tell you to get rid of it all. it’s not supposed to be there. wash your smile down the plughole; elastic fingers knotted tightly together, scraping a framed skeleton. you’re trying not to fall off. a foreign name tore itself away from you. now you’re nothing but a shell, rotted into a grey unidentifiable paste, a carcass, the empty skin of yesterday. ‘pathetic,’ you murmur. you’re right.

24

nax Olivia Stone

Sophie Chung

come home at the end. blood lingers rigid in my veins, listening as i go out to the garden and set my body down, plunge my arm into the coarse leather ground and tear out clump after clump of heated flesh. dull anticipation smeared across my creased face, waiting for tiredness to bleach my thoughts. glance up from my aching hands; my fingers are somewhere over there. smiling warmly at my own corpse as i bury it. it watches me. drenched in silence. i say, ‘hold my hand before i go.’ but it’s already scattered too far. a groan and a wrinkle and a frown, thrown about. my breath doesn’t fit me anymore. i take it off. and then i am still for a long while.

PREDICTION I

nax

25

Doctor... who exactly?

Doctor Who is a long running staple of British Television which began in 1963, but when the lead actor who played ‘The Doctor’, William Hartnell, fell ill, a miraculous idea occurred which ensured the longevity of the show. The writers implemented the concept of Regeneration: when a Time Lord (The Doctor is one of these species) is fatally injured, their body completely transforms itself, giving them a new look as they physically change their entire bodies and in some cases drastically change their personalities, yet they still identify as the same person.

Ollie Rose Mikako Shiomi

Ollie Rose Mikako Shiomi

Doctor... who exactly? 26

So here’s the question, when The Doctor regenerates, who actually wakes up?

You may just say, ‘Well The Doctor wakes up, they’ve changed bodies but they’re still the Doctor’. Well, what conditions allow us to say that the person who wakes up is still The Doctor?

Since John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, the puzzle of personal identity has baffled philosophers. Before Locke, the default assumption was that the soul was the bearer of identity. With Descartes calling it the res cogitans, meaning: “the thinking substance that I find myself to be.” Locke however, claimed that the identity of the self was separate from the identity of the soul. He argued that one person could have multiple successive souls and yet still be the same person. Although if I somehow had Socrates’s soul that alone wouldn’t make me Socrates. To be the same self, he believed, you did not need the same soul. He also claimed that the body was not the required instrument to determine the self, as he argued that if a cobbler and a prince were to somehow swap minds in their sleep, we’d say the prince wakes up in the cobbler’s body and vice versa, not that the prince wakes up with the mind of a cobbler. What Locke saw, is that when confronted with imaginary situations where mind and body come apart like this, our intuition is that personal identity follows the psychological facts rather than the physical ones.

To be the same self across time is to have some sort of psychological relatedness between persons. The difficulty here is that the Doctor’s personality varies vastly between incarnations, with some even having contempt for the others. And so, if this is the case, then how is that psychological link still present? You could make the argument that a reformed criminal may look back on their previous actions with shame and disgust, but they are still the same person regardless of how their mind has changed. So, a further explanation is required but Locke isn’t very helpful here, as he just speaks of “sameness of consciousness” with not a great explanation for what that actually entails. So in response, one could utilize the “Memory Criterion” viewpoint which, simply put, states that if I can remember the events in a person’s life, I am that person and

so as The Doctor remembers being all his previous selves, he is that person. Simple enough, right?

However, this idea once again has issues as raised by the 18th century philosopher, Thomas Reid who asks us to imagine a boy who receives a punishment for stealing some fruit from an orchard. Then he later becomes a brave soldier who is honoured for his commitment to the battle and much later on, as an old man, he is promoted to general. This man can remember being the young man but cannot remember being the boy, yet he is still the same person who stole the fruit regardless of the memory loss. Here the normal Principle of Transivity (where if a=b and b=c then a must =c) is not correct.

The show raises even more questions about identity when occasionally, multiple Doctors meet which is an elaborate version of what Parfit (another philosopher) christened ‘A Branch Line Case’. His idea is this: let us say we have a process for teleporting you from Earth to Mars, it records every single bit of information about you. Then it disintegrates you. At exactly that moment, the information is beamed to Mars where another machine uses it to create a perfect replica of you out of organic materials. Because your brain has been perfectly recreated, the person who steps out onto the surface of Mars will have all the Earth person’s memories including the memory of stepping into the teleporter. How do we describe this case? Have you survived? Would this be as good as survival? Well then it gets even more complicated, suppose the machine on Earth gives you a few minutes before it disintegrates you, while on Mars “you” have already been assembled. On earth you even get to talk to your replica on Mars via space Zoom call. They look exactly like you, have all your memories, loves, hates, dreams yet you can talk to them as if they are another person. In this case, the soon to be disintegrated person on Earth constitutes a “Branch Line” of the self.

Unlike this example, The Doctors share the same memories and some of the same personality traits but not all the same loves and hates and so is that alone enough to consider them the same person? For Parfit, facts like this are all there really is to it: If I know these people have the same memories and roughly the same character then they are the same person.

Robert Nozick posed the idea of the Closest Continuer theory, which outlines that to be identical with some former person is just to be the closest continuer of that former person. This has a certain plausibility to it: the pre- and postregeneration Doctors are the same if and only if the properties of the post regeneration Doctor “stem from, grow out of, are causally dependent on” the pre-regeneration Doctor’s properties and there is no other person that stands in a closer relationship to the pre-regeneration Doctor.

Whilst I have provided a multitude of different theories and ideas on personal identity throughout this article, perhaps this case is not a matter of psychological or physiological continuity but of some form of subjective continuity whereby the Doctor’s past and future selves are them because they somehow acknowledge them as such. Suffice to conclude, regardless of what shape or personality they take up, the timeless character known only as ‘The Doctor’ will always continue in some form or another.

27

Like idle trees fainting in vacant woods; Unseen, We’re no more than two bone-washed faces, reflecting billboards And pharmacy signs in our cheeks’ intrinsic girl gleam. As we walk, our noses’ white, blunted into plum

From thick night wind; and hot, soupy dinners.

And so full-bellied we plip our way through the inky potholes, Rain slick hair like hiyashi soba, we ate with our phones in a pile

We ate for friendship, like a tradition

We ate, as if it were for peace, nobly. With the same languid leisure as if we were popping blush-colour grapes, We ate like we have for millennia

Our lightheartedness, we choose naïvety, The rudiments: a clover, a tea, a sign for Fresh Mangoes 90p— our luminaries. When someone crosses you, you put them upon your crown as your Teacher, Not as a pardon, rather, to seize.

When we’re alone like this, No way to prove our presence, We’re merely mimics of industrial, superfluous taglines, Phosphorescent slogans projected onto our young skin: Radiant, as if by mutation, copyrighted and trademarked.

It can be overwhelming, but we live our lives in the interim; We wish and we make promises

With the best part being their futility, I stand for the endangered solenodon! We reject and deny our genes

To make an exoskeleton—synthesise—a paletteable identity.

Beneath, we recognised the true things, what you can hold on to; While swathed in temporality, And clogged with tautology. While looking at your eyes, A projection of O—P—E—N—2–4–H—R—S rolls out like credits, We’re bathed in bliss By sagacious ignorance.

2

28

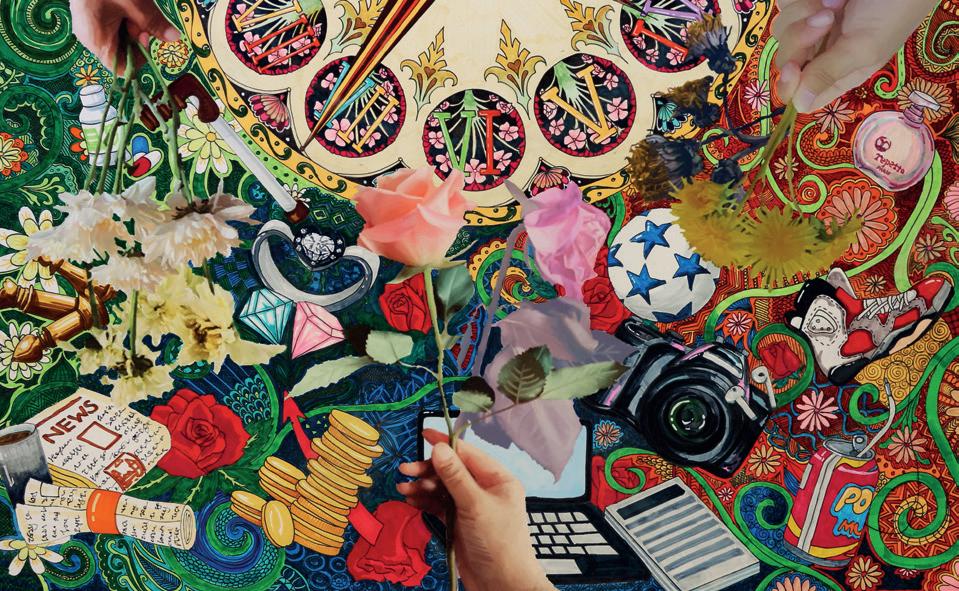

Amelia Burns Sydney Mei

+ 2 = 5

TEN

TEN

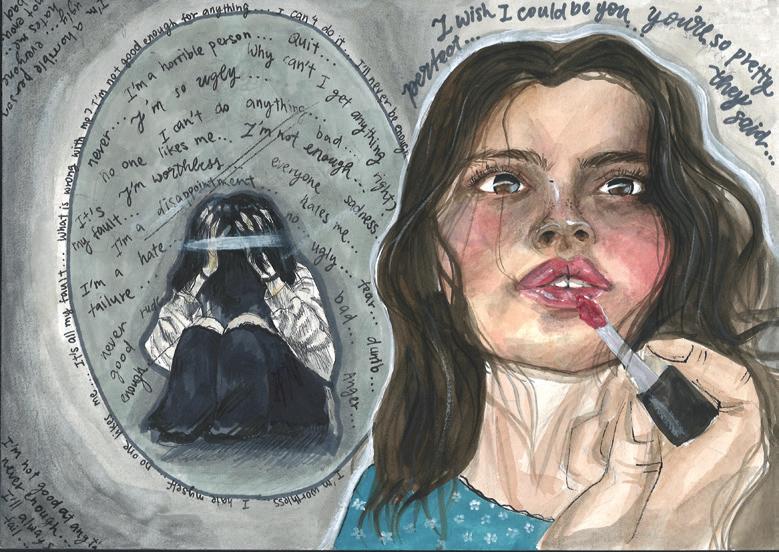

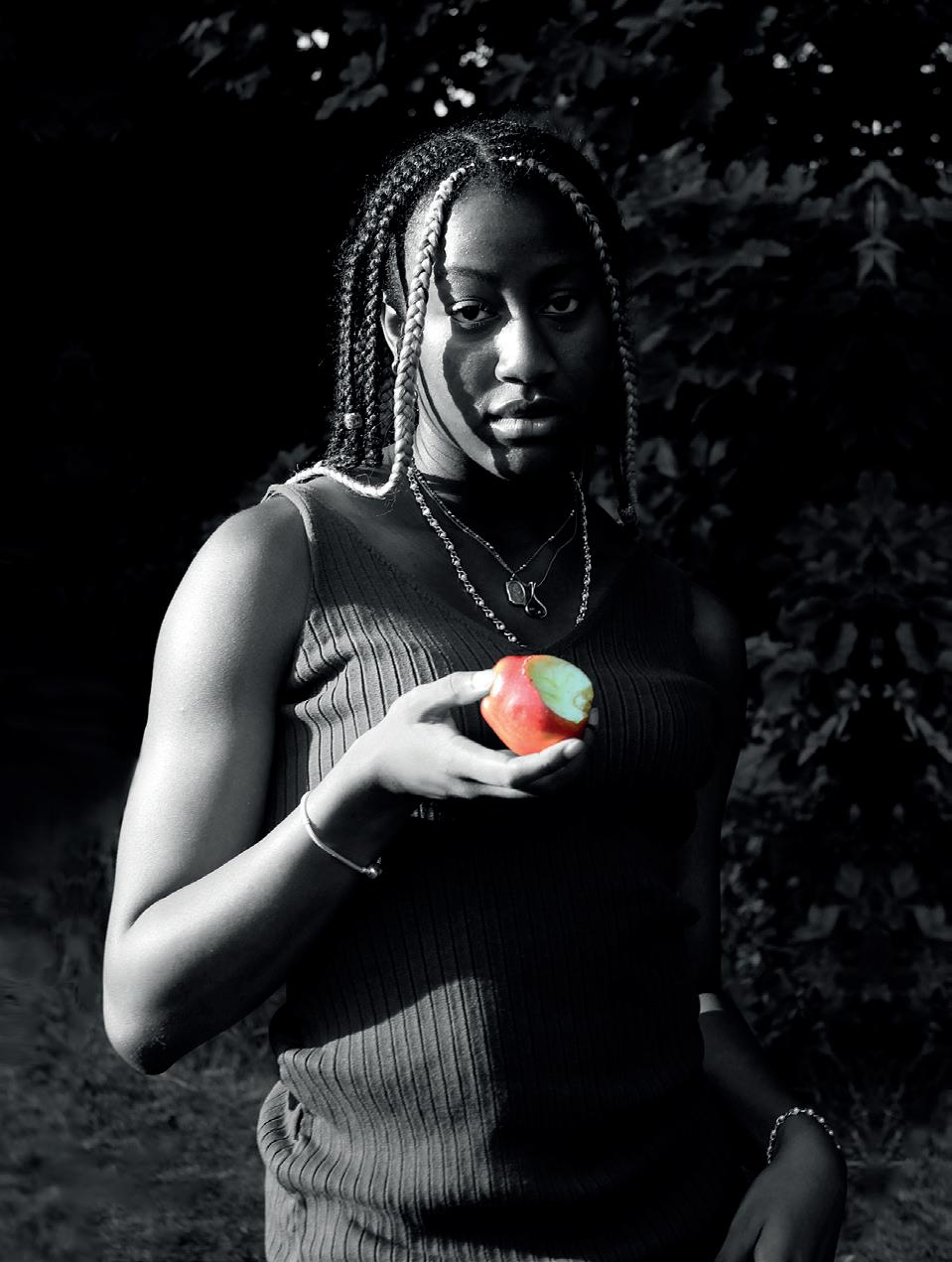

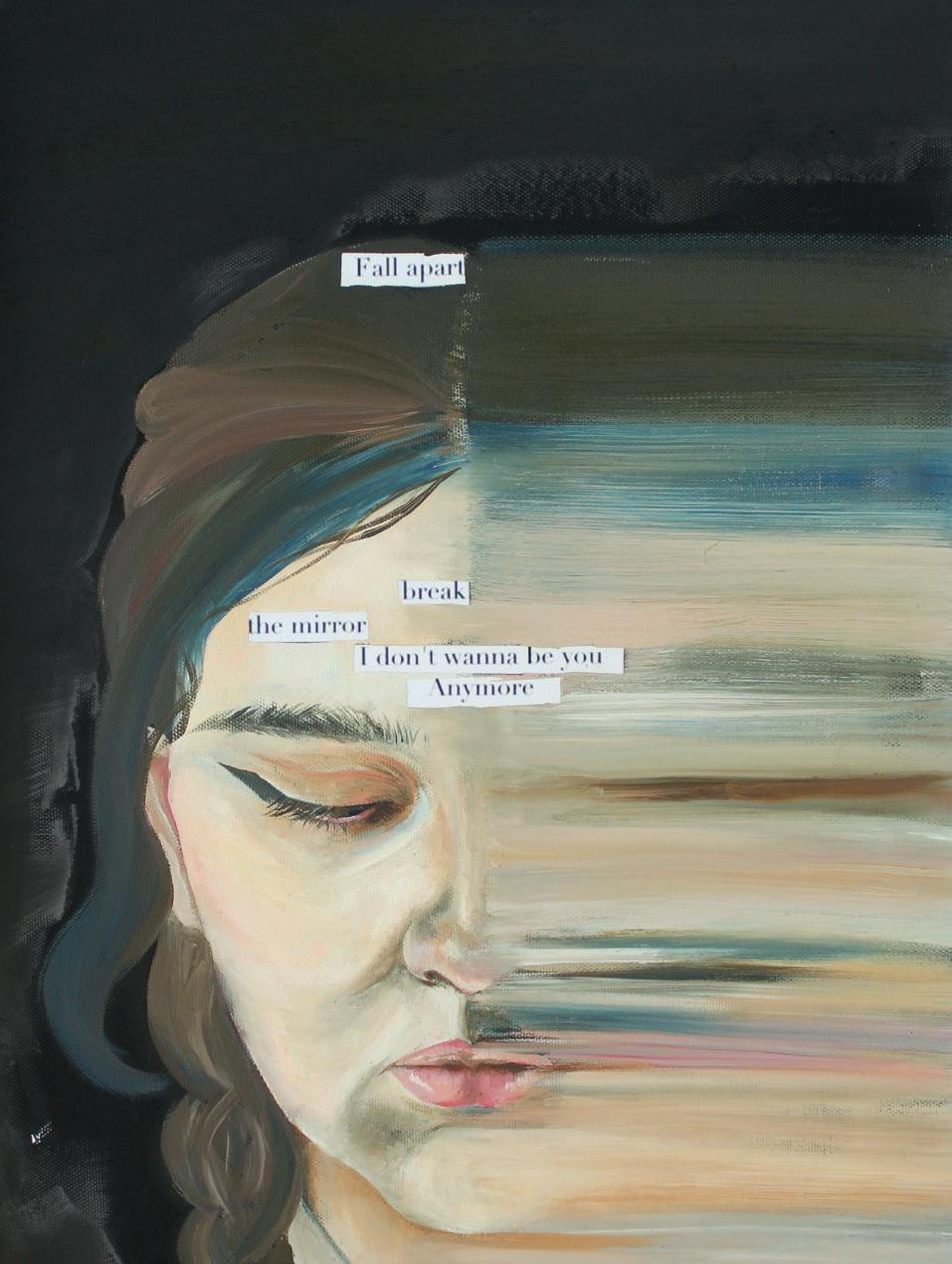

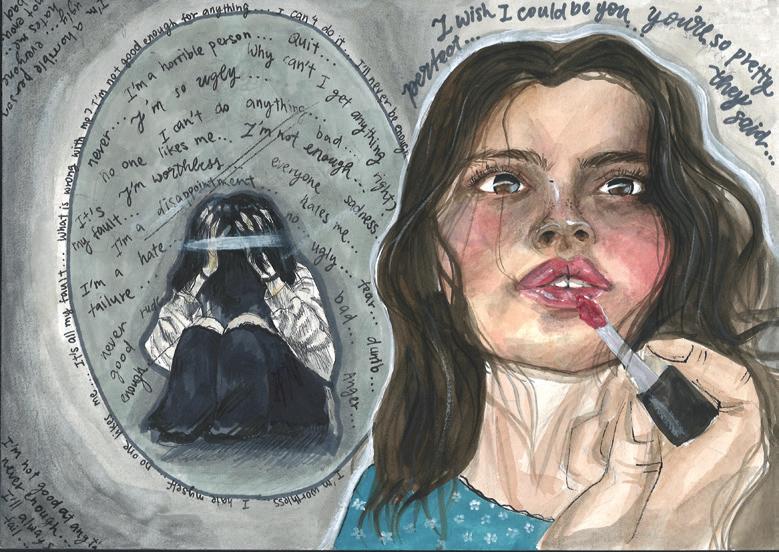

I wanted to begin this poem with the idea of the string of fate in mind, a belief originating from Chinese mythology that describes how everyone destined to meet is connected to each other by an invisible red string that cannot break regardless of time, distance or circumstance. This concept (along with the idea of past lifetimes) has always fascinated me and in this poem, I wanted to convey them in a slightly more tragic light. I spent a long time romanticising unrequited love and not seeing the damage and the hurt it caused, and so this poem is about that realisation that some things only come into your life in order to teach you a lesson – you need to learn when holding on hurts more than letting go.

The theme of this edition of Cat Among the Pigeons is ‘visibility’, and so I also wanted my poem to explore the inverse – invisibility – and the deep yearning to be seen by those who won’t see you. I wanted this poem to say, ‘I see you in everything insignificant, yet you don’t see me at all’.

I tie the noose of our fated red string

Around my neck, The universe hates me.

I love you- I think

I’ve known you a couple lifetimes, Did you break my heart in each one?

I whistle a tune

And I think of you, I can’t remember its name.

Tarot cards, aligned stars, faded white scars

They all tell me what my heart wants to hear

He’ll be yours someday

They say, He’ll love you, just wait They say, Be patient.

You’re my favourite word

And I look for you in every book I read, Every song I hear, Every painting I see

Don’t you see?

How could you love someone

As naïve as me. Let me go.

TEN TEN

TEN

29

Estella Yip Mark Wolstenholme

Oliver Khiara Sienna Algar

Nectar

Bundles of bumblebees borrow gloops of nectar drooling from a flower’s tongue

To keep us alive.

Willows hug the ground only to sway so we don’t choke, Nothing else. They forgive and forget, A rhythmic ritual, Till rigor mortis claims

But teeth bite on blistered wood

Through silent weeping, By the virtue of “wise man”

In untold pools of drowning and foam

They’re strangled in greasy puddles, Our sweet nectar so she cracks and writhes and we cry, To dig your own grave is one thing But to dig one of a miracle is another.

EyeStorm of the

When the wind is tumbling round, And the lighting is forking down, Can’t barely see in front of you, You cannot stop, we have to move.

The sheet of vast dark rain Can make you feel small or drained. But, in times of fear and fright, Remember that water brings life.

The pathway may seem bumpy, The gravel could be cracked, The ground might be slippery, But it will all pass, just like that.

So it may seem dark at first, But soon the light will reveal, Remember behind every storm, You’ll change the way you feel.

Clemmie Fagan Andrew Or

30

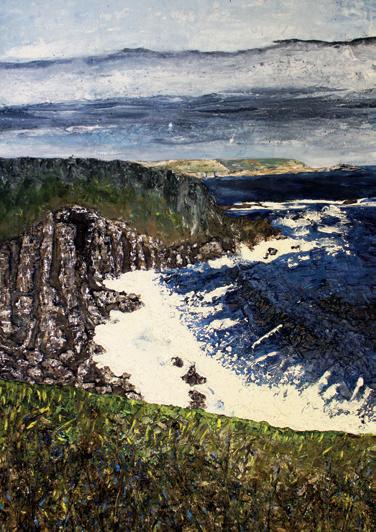

Foreword:

I wrote this poem following a conversation that I had with a volunteer at a National Trust property, as an attempt to address the often overlooked and forgotten impact of slavery in our past, and the millions of lives that were brutally exploited for monetary gain.

Narayan Minhas

Alice Keyworth

Mordeton, Cheshire

The water-lilies are early to flower this year, But be not deceived by their impressionist pulchritude Which extracts your attention from where they sleep On the liquid silver. And though it is beyond your sight, Something is concealed beneath it, so unfathomably deep. In the pond, there is reflected a house, Whose old red bricks blush in the closing twilight With the lilac wisteria that deluges over its sash-windows. Now enter beneath the ionic portico, Through the hall, And into the drawing-room, Where the walls are clad in a florid damask of carmine; A dye forged from the crushed bodies of cochineal insects… Like slaves?

Who were crushed day and night, under a horsewhip. To keep them in line.

But through a window, you notice a walled garden, Beyond a wrought iron gate. Where the lavender sighs, the foxglove exhales, And the rose murmurs drowsily.

As they distil their enticing musk into the evening air, You go to unlatch the gate, But find its hinges having rusted tightly. Like gyves fixed at the wrists and ankles, Corroding into the bone. Then a sound that you stop to listen to: An ecclesiastical crescendo, Of bells from the parish church down the lane. If only, you think, as the toll nears its demise, St. Margaret peals the bells in her tower, Not for those buried in the cold earth, But as an elegy for those Buried in time, And forgotten long ago.

31

Visibility Visibility Visibility

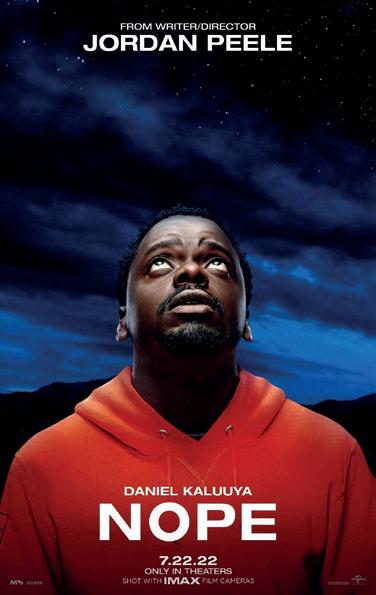

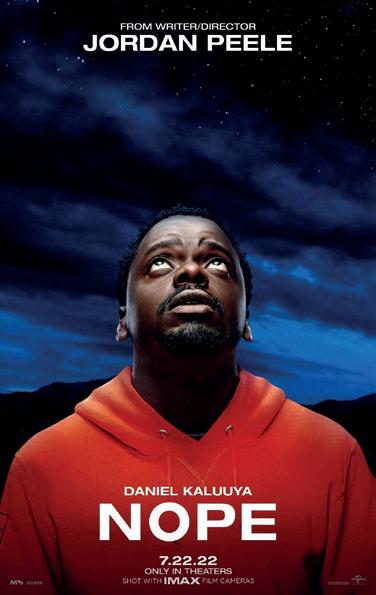

Writer-director Peele’s third feature film, Nope was released in the summer of 2022 to widespread acclaim; its exploration of diverse themes such as the internet, spectacle and institutionalised racism in Hollywood makes it an engrossing film to rewatch, analyse and write about. Nope centres around Emerald and OJ Haywood, horse ranching siblings, living in a lonely gulch of California, who bear witness to an uncanny and chilling discovery. They spot an unidentified flying object, which has made the sky above the Haywood Ranch its home and the surrounding area its number one hunting ground.

SPECTACLE

The idea of spectacle in Nope is outlined before the movie even starts. After the iconic Universal Production Studio’s logo disappears, the screen turns black and a bible quote in white lettering appears, “I will cast abominable filth at you. Make you

vile. And make you a spectacle.” Keen theologists among you may recognise the quote from Nahum 3:6 in the Old Testament. When I first read this, I was immediately drawn to the last line, particularly the last word. A spectacle is something that we see, something we are pulled towards as humans and it seems that in the modern world of the internet, phones and globalised communications, the ‘spectacle’ is becoming more disturbing and ubiquitous. When being interviewed for Today America, Peele said that Nope is an, “Adventure and a horror spectacle about human nature.” As human beings we are attracted to visually striking things, places, and events, whether they be beautiful, disgusting, life affirming, brutal or horrifying. It seems that more and more often, we are watching more disgusting things, recording more brutal videos, and taking more horrifying photos. With this biblical epigraph, Peele underlines that the audience are going to be exposed to violence and destruction during their viewing.

Visibility can be defined as the state of being able to see or be seen, whether that is symbolically or physically and Jordan Peele’s Nope has it all.

Dante Butler

32

We all know those people, on the internet and in real life, who will do anything for attention, views and likes. For example, Logan Paul, a YouTuber, who in 2017 filmed a suicide victim in a Japanese forest. This is not an uncommon occurrence and Peele knows this - people are constantly trying to film the spectacle and they will do anything to get the best shot and make the most profit. The entire movie is almost a parody of this human trope and particular brand of person. The satire of human nature and internet culture is particularly clear when examining the character of Ricky ‘Jupe’ Park, played by former Walking Dead star, Steven Yeun. Ricky is an actor who rose to stardom as a child, playing roles in films, TV shows and in particular the fictional sitcom, Gordy’s Home We first meet Ricky when OJ and Emerald visit his home and theme park (which happens to be the Haywood Ranch’s closest neighbour, despite being several miles away), known as Jupiter’s Claim, a neo-western attraction for kids and teenagers. Whilst OJ attempts to negotiate business terms and the sale of some of his horses, Emerald distracts Ricky by talking about his past fame and fortunes. Ricky then presses a button and a secret room in his office opens, displaying several artefacts from his acting days on the set of Gordy’s Home, a sitcom about a family with a pet chimpanzee. Fortunately, Gordy’s Home is not a real sitcom but the events that cause its downfall are all too chillingly realistic: during the filming of ‘Gordy’s Birthday’, one of the chimpanzees went crazy and started attacking the cast, leaving two dead and one with life changing injuries. Despite watching several people die at the hands of a wild animal in his early life, Ricky is not traumatised by it; he enjoys it and has curated a room full of objects from the set on that fateful day. Ricky utilises his past traumatic events for money and fame. He enjoys showing people bloody clothes from his fellow cast members (for a price) and he even lets people stay in the room, (for a price), “A Dutch couple paid me 50k to spend a night in here.” This underlines Peele’s belief that this idea is so engrained in our culture as humans - that we will do anything for money, we will show anything for money, even artefacts of our past traumas. Ricky sums it up perfectly, “It was a spectacle. People are just obsessed.”

VISIBLE (AND INVISIBLE) HORROR

The main drive of the two main characters in Nope is to capture video evidence of the alien spaceship so that they can sell it to the news (for a price). In order to make the story thrilling, exciting and scary, Peele pays special attention to what is visible on screen. Peele plays with visibility throughout Nope in order to create a tense and horrific atmosphere. As it is technically a horror movie, what is shown on screen is doctored to make it scarier and Peele does this masterfully, with help from Academy Award nominated cinematographer, Hoyte van Hoytema. As Hoytema masterfully puts it, in an interview with Vulture magazine, “The horror is very often in what you can’t see.” This is done particularly effectively in the middle of the film when the UFO has just devoured a fresh set of victims and is digesting them. The alien situates itself above the Haywood house mid digestion and lets out all of the blood, keys and money that it cannot consume. This creates a deeply disturbing shot with the house dripping with blood as OJ watches on from outside, the alien not in view due to the night’s darkness. This is visual horror at its best; the audience is unable to see the alien but can see a truly gruesome display, increasing tension as the alien could come for the main characters at any moment. Terror in a movie scene does not always come from what is visible, but what is invisible

On the whole, Nope creates an intensely disturbing atmosphere through the crew’s different use of camera angles as well as lighting, playing with what is visible to the audience at all times, for maximum horror. Additionally, Nope brings up many important issues that underlie our society today, particularly that of the spectacle, where people are obsessed with the terrible things that they can see and the awful things that they can film through the internet, social media and the news in order to gain fame and popularity. Peele weaves these extrinsic themes into a brilliantly crafted horror film that will leave your adrenaline levels high but also leave you with a few important messages to think about.

33

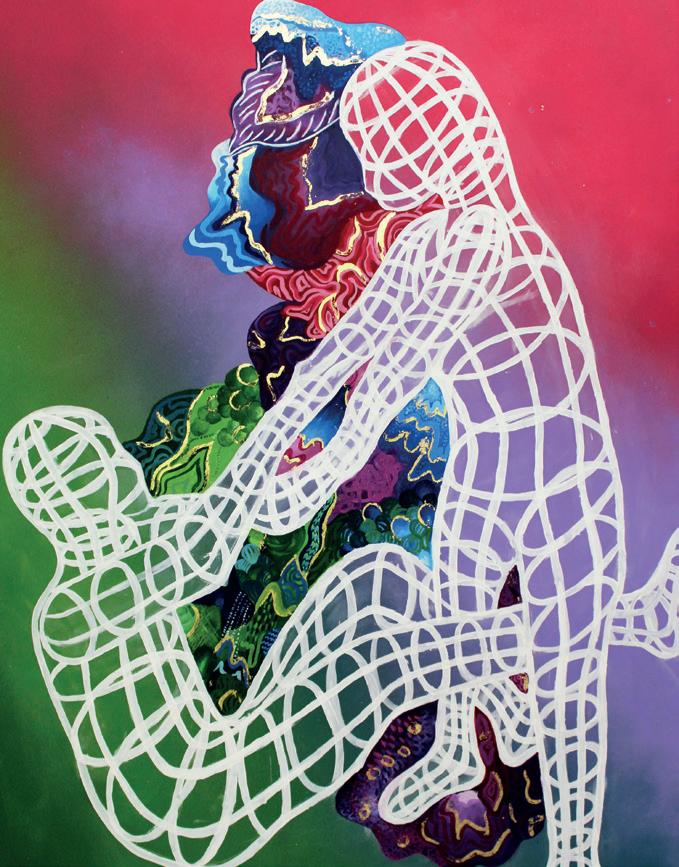

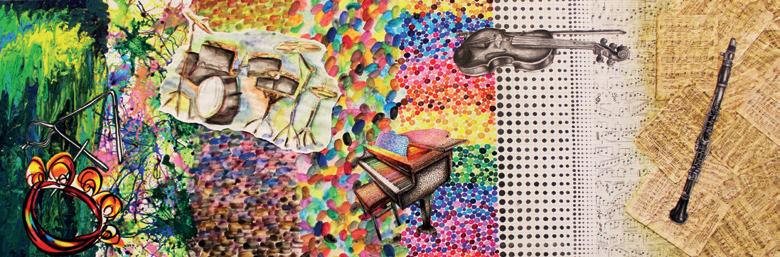

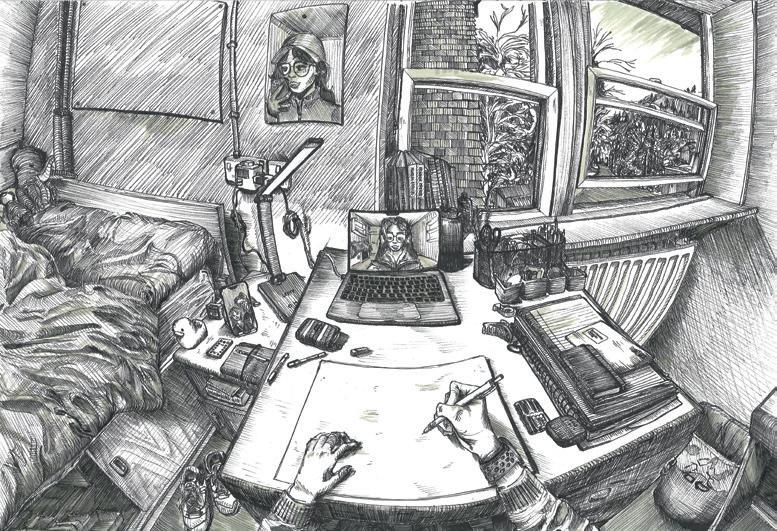

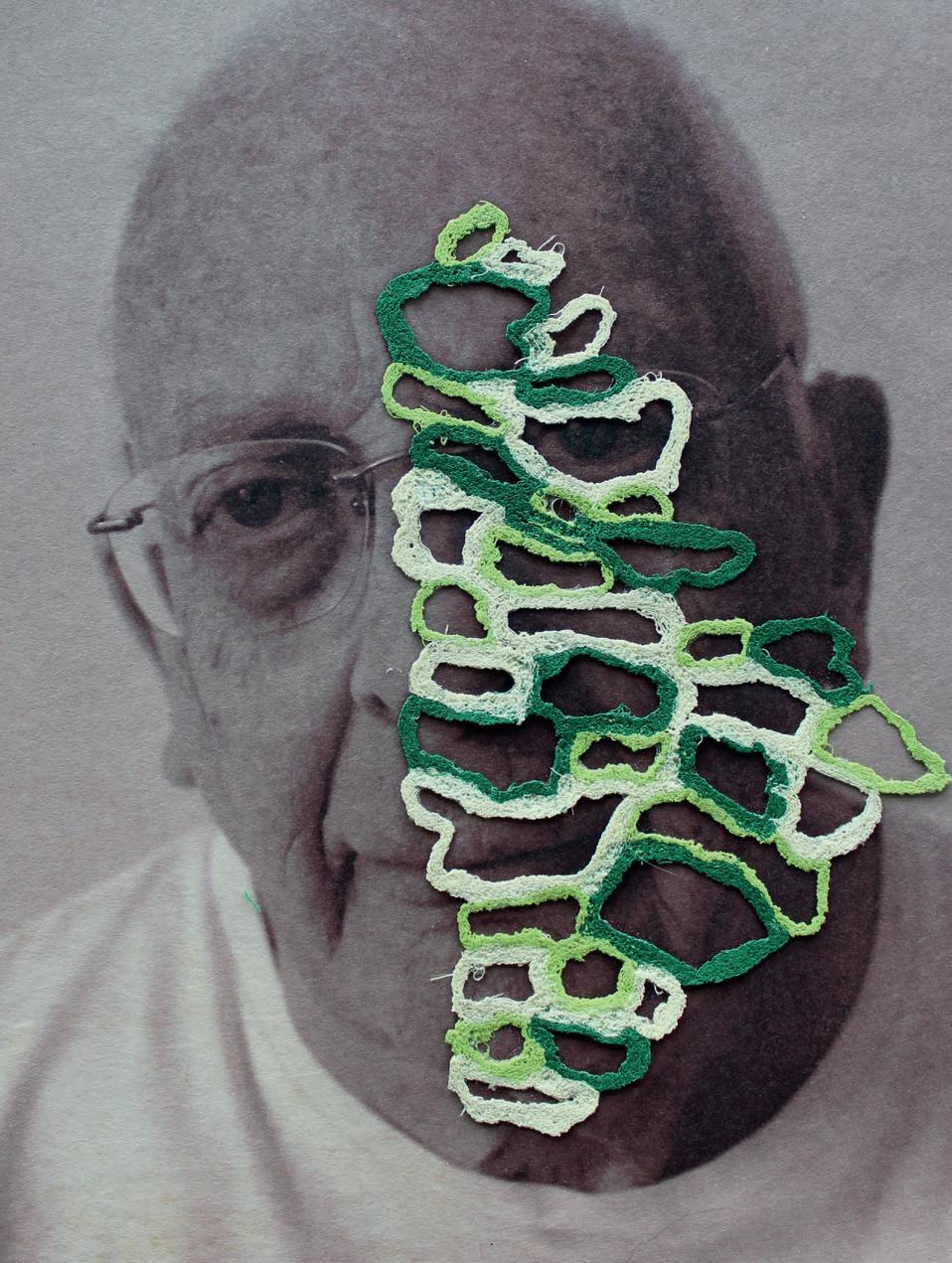

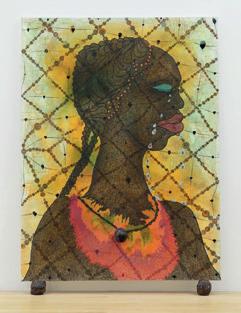

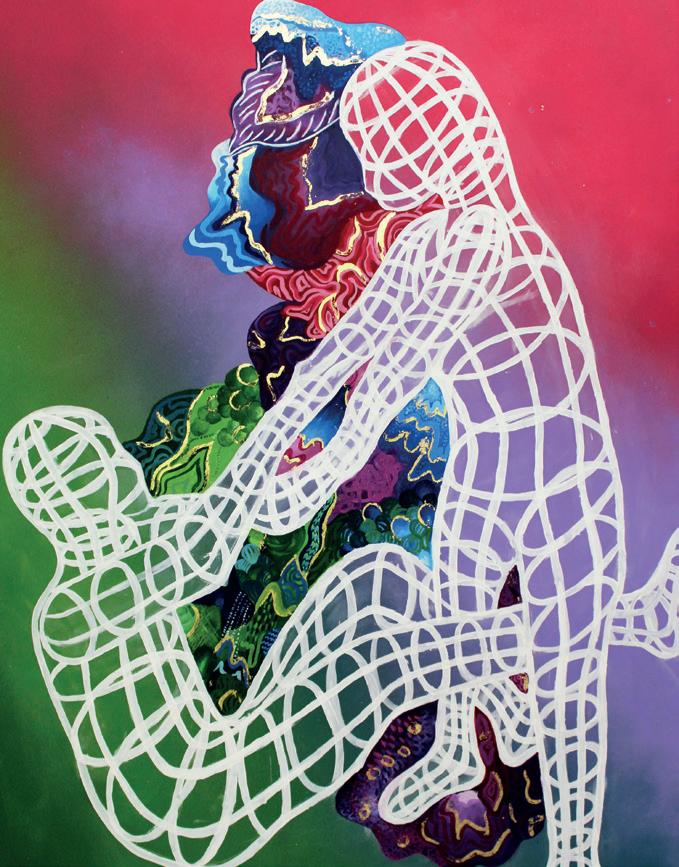

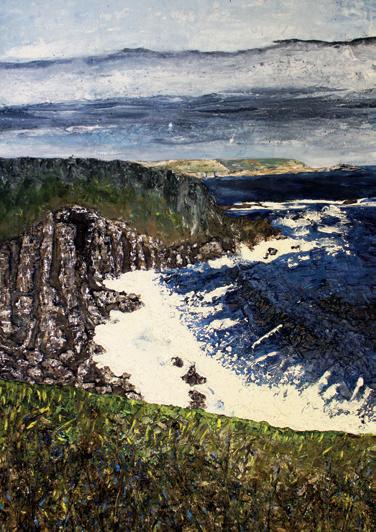

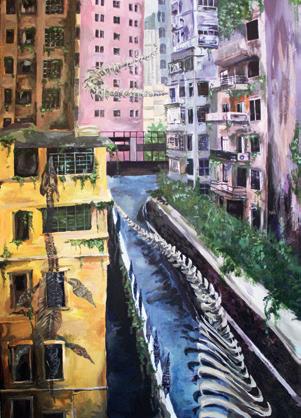

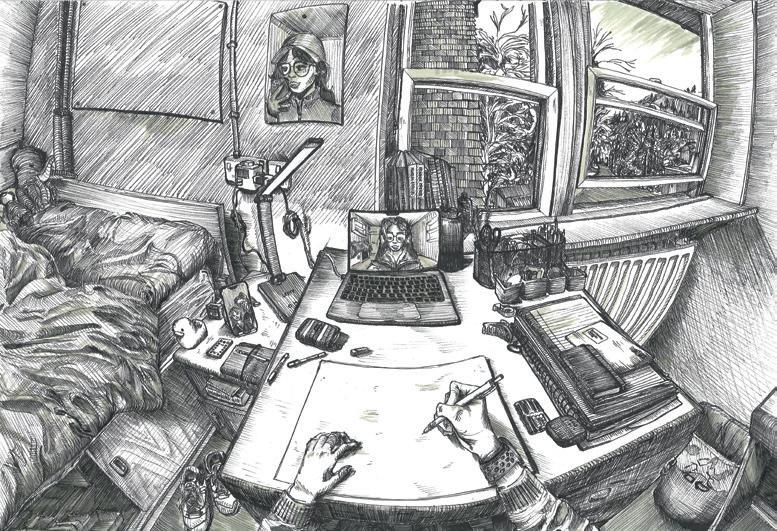

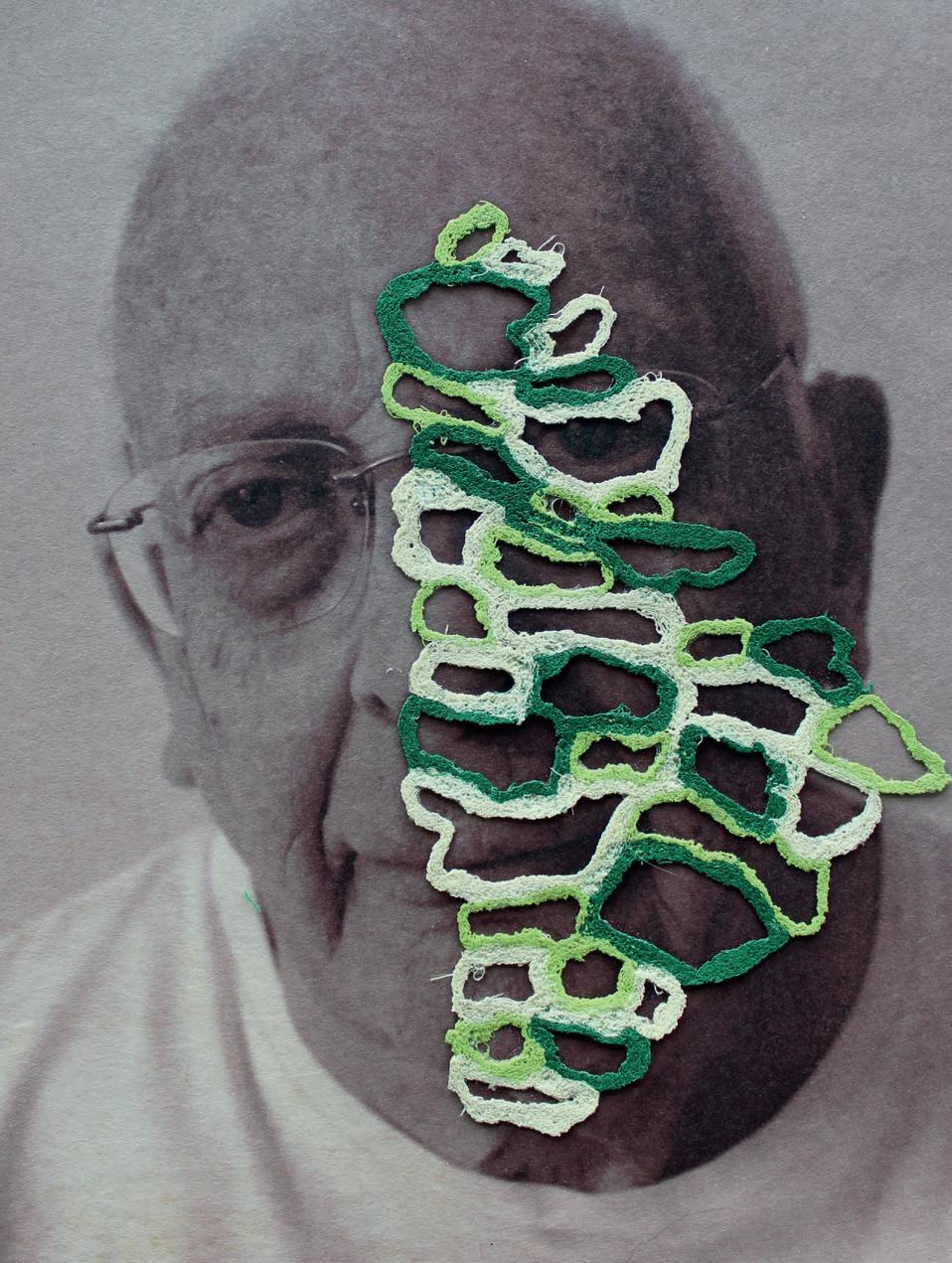

A Level Fine Art

VALERIE PANG

SOPHIE CHUNG

VALERIE PANG

SOPHIE CHUNG

34

ZARA PITTS

ISABEL

35

HARRY EVANS

SAMPSON

Emma Tagliarini Harry Evans

There are many shades of shadows. Their beauty is deep and profound. But we only think them in black and white, When, in fact, their darkness flows. It pours into every vein, Every beat of the stricken heart And curse! For those who disbelieve Are only further shadowed in their pain. Every single colour that tinges our skin, Every single tone and shade, Is really an illusion to hide the voice That hisses poison in the din.

36

This Woman’s Work…

Pia Shah

The idea of “a Roman woman” implies there is one reality for the millions of women who lived in the Roman world over centuries. The lives of Roman women, of course, varied drastically depending on their wealth and social status, their place, their time. Some factors remain broadly the case, however, Roman society imposed laws and restrictions on what women were able to do such as restricting their right to vote, to participate in political life and often to own their own property. Their place in society was, for the most part, dependent on men. And yet they are not entirely silent across the millennia. In literature, historiography, art and epigraphy, we can hear the voice of women or gain some insight into how womanhood was viewed in the Roman world.

Neat Elegance and Blushes

This idea of a ‘traditional’ woman comes through in Virgil’s character of Lavinia in his Aeneid. Lavinia is a girl for whom most of the battle is fought in the second half of the poem yet she stays silent for the entirety of the epic. She remains in the background and blushes in the manner that was expected of a Roman woman: “when Lavinia heard these words of her mother, her burning cheeks were bathed in tears and the deep flush glowed and spread over her face”. Through his characterisation of Lavinia, Virgil is presenting what the ideal of a woman might be. High standards were always expected of women throughout the empire and this is evidenced in Ovid’s poetry where he says “we men are attracted by neat elegance. Don’t let you hair be unruly –hands carefully applied create beauty”. Ovid’s writing is witty and naughty and the reason that his joke here works is because of what women were expected to be like at that time. While we cannot take his poetry at face value, it still contains an element of truth.

Women were under the authority of a man for the duration of their life; from her birth where a woman became the property of her father until marriage at which point she became the property of her husband. The average Roman woman would not have had much control over her own life. Some sources give damning pictures of various women who transgress and held power. In Tacitus’ Annals. Livia, the ambitious wife of Augustus, is demonised: “Tiberius was driven away by his mother’s domineering manner. He refused to have her sharing his rule but he could not remove her because he had received that rule as a gift from her.” Tacitus conveys the idea that the empire of Rome was given as a gift by a woman here. When we read of powerful women, we see that they are referred to with loaded, moralised language hinting to the idea that Romans could not deal with women who wielded too much power.

To Have and to Hold

Marriage was mainly, but not merely, a bond between the Fathers-of-the-Bride to gain social status. However, epigraphical evidence reveals more about the brides themselves: A snippet from the epitaph of a freedwoman Allia Potestas which says “she would speak so briefly and so was never reproached… her yarn never left her hands without good reason” shows how well she fitted the Roman ideal of a woman who stayed at home concealed within

shadows busying herself on the loom. However, the epitaph was written in different sections. The first mirrors the Roman idealised image of a woman who is hardworking at home, the second puts emphasis on her beauty, but most shockingly, it mentions that “while she lived she so managed two youthful lovers that they were like Pylades and Orestes”. This epitaph in particular highlights polyandry which was an aspect of some women’s lives that is not mentioned in many literary sources since it contradicts the idea of women having to remain ‘univira’. Finally, the third section of Allia’s epitaph stresses the loss her husband will feel without her. Women were seen as the property of their husbands but epitaphs, unlike many literary sources, are able to give glimpse of many women in loving, affectionate relationships.

Working the Streets

Women were not just confined to their domestic sphere, as some sources would have us believe; the terracotta relief from Ostia shows women working in the market place selling vegetables and chickens. This relief along with the epitaph for a lady that says “her husband built this tomb for the well-deserving dealer in grains and vegetables” highlights that in reality, although there is little suggestion in literary sources, women had occupations and were pivotal in providing income for their families – particularly those of the lower class. Trading in markets was not the only job available for women either, there were many women who were forced into or sold themselves into prostitution. There was evidence all over Rome showing this prostitution and two graffiti about the same woman was found over Rome: “…in the district of Venus, ask for Novellia Primigenia” and “Health to Primigenia of Nuceria. For just one hour I’d like to be the stone of this ring, to give to you who moisten it with your mouth, the kisses I have impressed on it.” The volume of evidence found regarding the sex market and prostitution show us the reality of women’s life outside the traditional domestic sphere.

In conclusion, I think that the realities of women’s lives are visible from the various pieces of available evidence. It is worth remembering that almost all the literary evidence that remains now was written by men and therefore the views of women will be through the idealised eyes of a man. Non-literary evidence is the best way of seeing the daily lives of women since they are stripped of those elite idealised biases of writers such as Tacitus and Virgil. Through a combination of literary works, artefacts, archaeological sites, and inscriptions we can begin to gain a more nuanced understanding of the reality of the lives of Roman women and the complexities of their experiences.

Are the realities of a Roman woman’s life visible from the evidence we have from the ancient world?

Are the realities of a Roman woman’s life visible from the evidence we have from the ancient world?

37