A CONFERENCE OF BIRDS: ART BRUT AND MORE FROM IRAN

SARVENAZ FARSIAN

JAMSHID AMINFAR

NAZANIN TAYEBEH ALI AZIZI

MOHAMMAD BANISSI

ALIREZA ASBAHI (CC)

KIYAVASH DANESH

MAHMOOD KHAN

ABBAS ARVAJEH

ZABIHOLLAH MOHAMMADI

ALIREZA MALEKI

KAZEEM EZI

LIMOO AHMADI

A CONFERENCE OF BIRDS: ART BRUT AND MORE FROM IRAN 2024

CAVIN-MORRIS GALLERY

NEW YORK, NY

The Conference of the Birds , from which we borrowed the title of our exhibition, is a Persian poem by Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar, commonly known as Attar of Nishapur. The poem depicts a mythical quest of divine selfknowledge, each bird representing a human fault that prevents the embrace of Enlightenment. The birds go on a quest to find the visionary bird called Samargh, who would teach them to transcend those human foibles and eventually become timeless, with past, present and future becoming simultaneous.

We saw this timelessness as a great metaphor for the commonalties Jean Dubuffet was discovering in his idealizations of the nonmainstream artists he was collecting under his banner of art Brut. This inspired us several years ago to begin planning this exhibition with Morteza Zaahedi and Sarvenaz Farsian, Iranian artists, collectors, dealers and documentarians of a vast cross-section of the indigenous artists of Iran.

We had seen the works of Davood Koochaki in the abcd Collection in Paris and we never forgot their energetic, poetic worldliness, wild and secretive at the same time. Koochaki was our first introduction to a vast world of art from a deep and complicated history. It is only now just being explored with a massive backlog of discoveries and research by Morteza and Sarvenaz who have been our patient and tireless mentors through this rich chapter of global art history.

The people who make this art are not making it for any pre-existing art world canon. Art Brut is not a ‘thing’ in Iran. These works were made by cultural means for subjective reasons ranging from personal grief, pain, joy, anger to elaborate ways of making time pass in difficult times, engaging it sometimes deliberately and sometimes not, as a form of cultural resistance.

It is very rare that we get to experience a body of work that is more often than not in its original context, accumulated with its own forms respected, moving freely along its own timeless path. Dubuffet must have felt this thrill when he explored and collected initially in Switzerland. Others felt similar magic moments with the artists of Kenya, Haiti and in the Arctic. I felt it when Wayne Cox drove me through Jamaica to meet three generations of artists, year after year. There are similar chapters in India, Italy, Brazil, and other countries. We also include many of our experiences in the African American southern reaches of the United States. These are similarities not in subject matter but in the presentation of universal human concerns.

What made Morteza’s and Sarvenaz’s collecting so important to us was its high level of artistic quality only natural, given their own artmaking — and their passionately keen eyes. They are the eyes of curators and collectors, open to the improvisatory and

wondrous, all the more powerful because they are from the same culture from which they are collecting. We were at once drawn in aesthetically and intellectually to their ongoing project. We understood immediately that for them it was an extension of their own involvement with artmaking.

Art itself for some people becomes a form of self-definition in difficult circumstances. Art says “I AM”. The art becomes a form of work or career or calling; it supplies a respected role in the community. Even in the times it becomes marketed, the title of maker or artist or artisan carries a different weight or valence to the makers and the communities around them. It becomes a social role. It gives them some agency on their own lives. We see this in craft cultures more frequently but even idiosyncratic artists, spiritualists and visionary painters and sculptors are still fulfilling a cultural mandate. From the struggles of inner city and rural Black Americans, to the lakous of Haiti and the yards of Jamaica, this efflorescence of magic, spirituality and ancestral memory, as well as the complexities of mundane survival becomes a universal form of cultural resistance.

In presenting the Iranian oeuvre it is impossible to ignore the textilelike detail and patterning in some of the work. It reminds us of the power and function of trance in many non-Western cultures. Trance has been documented as a form of Cultural Resistance. This resistance

is not violent or lawbreaking but rather a creation of solitary or group modes of alternative survival, most often by women. The filling in of thousands of marks in a horror-vacui composition serves to make time pass in a constructive way.

We are showing work that ranges from narrative and rural work to urban artists and neurologically divergent artists with conditions like Down’s Syndrome and Asperger’s. Culture is the mantle that warms the creativity.

It is important that always we ask the questions: Who was this art made for and why? The mainstream art world and canon is never part of the answer. The work is primarily made for the artist, and secondarily the immediate community of family and neighbors. In desperate times the work becomes the artists’ confrontation with the passing of time in a life, with filling that time and abstracting the details.

At the end of the Conference of the Birds the birds find out that instead of an ultimate Master each bird is a reflection of the Spirit itself. To us this is what the artists in this exhibition are. Ultimately, they, and we (because they are us) become mirrors of the Universe.

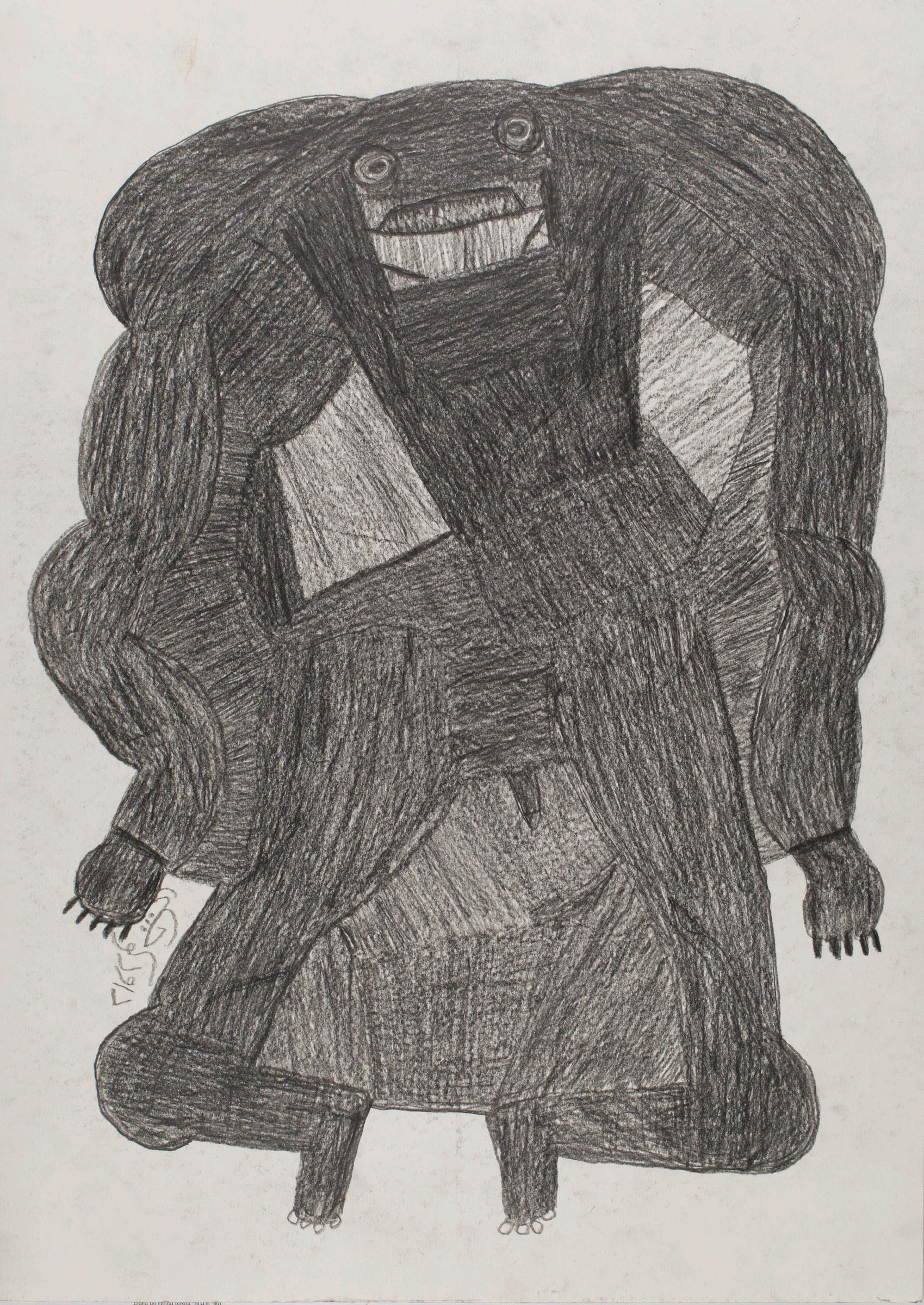

Davood Koochaki was born in 1939 in the province of Gilan in Northern Iran. He was born in Jambez near Rasht. He died in Tehran in 2022. His family were poor ricegrowers. In order to help support them, he dropped out of school at six to work in the rice paddies. Although he remained basically illiterate he took pleasure in philosophical discussions with artists and creative people he met later in life. He moved to Tehran when he was 13 and eventually became an auto mechanic, marrying and raising a family. He opened his own garage. He began to draw in his 40s but did not pursue it seriously till he was in his sixties.

He grew up surrounded by the rich folklore of Persia which animated the daily war between Good and Evil, often using animals to symbolize moral forces; for example snakes as symbols of evil and birds as signs of good omens. Nature was the stage for playing out eternal stories of struggle.

We can see this movement of forces in most Koochaki drawings. Like other Art Brut artists he allowed his memories, anxieties, dreams fears, and joys as well to come to the bidding of his drawing hand. He didn’t talk much about the precise meanings and symbols in the drawings but his process was time-consuming and was a way of conquering time and letting it pass.

Much Art Brut comes from the expression of repression, inner and outer repression. We have the histories, we see the results off World War 1’s unprecedented brutality on the inmates of post war

mental institutions for example Carlo Zinelli, we know of Anna Zemankova and Miroslav Tichy’s avoidance of the Russian occupation in what is now Czech Republic. We know the reactions in the United States and Caribbean to the forces of slavery and colonization. These were the artists Dubuffet championed….his preference seeming to be often artists who appeared from working class roots.

Art Brut, of course, appeared in all classes but some of the most powerful work came from blue-collar and poor workers who could no longer cope with the system. In case of political repression art becomes a way of proclaiming the self and/or making difficult time go by.

What makes Koochaki so great is his ability to voice nightmares and the good points of humanity at the same time. We are beings of contrasts and inconsistencies; we contain multitudes. We suffer and triumph, often simultaneously. Koochaki was a visual storyteller. He laughed and talked whether he drew dark or light subjects. He would often regard his finished drawings with bemused surprise, as if he were surprised by his own intensity.

Davood Koochaki has put his literal demons and angels into a personal visual language that is unique in our field, as if they were painted on the cave walls of his haunted memories. Like all of our anxieties they loom and move in a dance that alternates between the dark and the light, called down for us by the heart and hand of a truly great artist.

, 2017-2018

39 x 27.5 inches

99.1 x 69.9 cm DKoo 23

, 2010-2019

3.25 x 16.5 inches

59.1 x 41.9 cm

39.25 x 27.5 inches 99.7 x 69.9 cm

, 2010-2019

5 x 7.5 inches

12.7 x 19.1 cm

, 2019

39.25 x 27.5 inches 99.7 x 69.9 cm

, 2017-2018

27.5 x 19.5 inches

69.9 x 49.5 cm

23.25 x 16.5 inches

x 41.9 cm

13.75 x 9.75 inches 34.9 x 24.8 cm

27.5 x 19.5 inches

69.9 x 49.5 cm DKoo 44

27.5 x 19.25 inches

69.9 x 48.9 cm DKoo 92

As Jamshid Aminfar was being born the oxygen flow to his brain was interrupted for a few seconds and the effects lasted all his life. He seemed to move and react in slow motion. He took a long time to complete his sparse drawings. He took a long time to speak, to walk, or to respond to people. He needed to paint but it drained his physical energy. His family was not poor. He studied in England and Morteza Zahedi relates that he visited Henry Moore. He loved the work of Edvard Munch, Frances Bacon and Van Gogh. He returned to England during the Islamic Revolution and experienced the changes to familiar life in the next eight years, and he was devastated by the loss of his supportive father. He fell into an opium addiction.

His family forced him to marry a disabled woman whom he lived with for twenty years. In those two decades he never touched a brush. He worked in a printing house those twenty years where instead of being the proofreader and printing supervisor he was hired to be, his coworkers taunted him for his physical disabilities and consigned him to being basically a janitor. He was fired and worked in a sawmill till a fellow worker’s hand was cut off by a chainsaw and he could not bear to be there any longer. He began to paint graffiti on the city walls. There really was no other graffiti in Iran. The police shook him down for drugs and kept him locked up several days till his family agreed to take responsibility. demanding a promise he would fight his addiction. He stopped opium and switched to codeine syrup, to which he remained addicted the rest of his life.

One day he took his money and bought some boxes of syrup. He was depressed and lost but kept painting. A few months later he passed on from cardiac arrest. This last drug binge was a slow suicide in the face of his depression, hallucinating, anti-social and bitterness. Inexpressibly alone except when he took time to visit Morteza and his wife Sarvaenez and use their space to work.

Despite all his problems his friends said he was gentle and kind. It was heartbreaking for them when their friend died. Jamshid Aminfar was a great artist whose work can be seen if one even uses labels anymore as art Singulier.

One could not be more figuratively minimal than the paintings of Jamshid Aminfar and at the same time be saying so much about so many things, from the daily tribulations of his addictive personality to the feeling that the world around him was in the process of imploding and with himself included, was coming to an end. Yet his urge to create never paused. He never lost his aesthetic embrace of color as a personal language nor the actual delicacy of his thick lines. There is a hidden sense of great anger and sorrow in depictions of clerics, or families. There is a foreboding sense. But there is also a love of life in his families and women giving gifts of flowers. Aminfar’s work was about him but his mastery was such that the work rises transcendentally above pain to find beauty in its own core. 1

1 Biographical facts from on line communication with Morteza Zahedi.

27.5

69.9 x 50.8 cm

JAM 5

27.5

69.9 x 49.5 cm JAM 6

27.75 x 19.75 inches

70.5 x 50.2 cm

JAM 10

27.75 x 19.75 inches

70.5 x 50.2 cm

JAM 13

27.75

JAM 15

69.9 x 50.2 cm

JAM 9

Kiyavash Danesh was born in Tehran in 1966. He dropped out of school early due to his poor academic functioning due to the worsening of his illness.

Kiyavash suffers from intense intellectual and practical obsessions or O.C.D., a common, chronic and long-term disorder. Every time he is under pressure, he feels that he must constantly repeat thoughts and behaviors

He was repeatedly hospitalized in different psychiatric hospitals and under the care of doctors, and with their prescriptions he used strong sedatives that had inhibitory properties and led to immobility and unconsciousness. Because his condition did not improve with drug treatment, in order to erase his memoryof everything - He was given an electroshock, which had no effect.

After the death of his mother and father his older sister took care of him for a while and then with the decision of the family he was temporarily transferred to mental asylums for treatment.

More recently, because it became difficult for Kiyash to adapt to the nursing home environment and he had lost too much weight due to his disobedience to the regulations and the way of feeding in the nursing home, he was discharged from there by his nephew who decided to take care of his uncle’s affairs.

Kiavash is now under his supervision and protection.

Kiyavash Danesh started drawing in childhood and this process accelerated after leaving school. Since then most of his time is spent drawing mental paintings. According to those

around him, when he engages in this act, he obsesses less. But this seems to go against the opinion of his treating doctors who believe that by doing this, he provokes and aggravates his mental obsessions. Because of this, he was not allowed to draw during some of the times he was hospitalized.

In addition to painting, he has always been very interested in history and geography and has detailed information about many historical events and developments by mentioning the names, times, why and how of those events in his memory. His drawings are a reaction to his inner dialogues. He conveys the words and messages he wants to express but also hide but is unable to do so except by the medium of drawing and often in this situation he takes refuge in writing. His artworks are full of manuscripts that are created with a kind of inventive handwriting (rather than images dominating the paintings and showing a narrative, they are line drawings of the subjects that occupy his mind.) He is afraid that his subjects and messages will be too revealing in the images he creates, so he distorts them with compressed and intermingled forms, and as long as he does not point out the purpose he had in the image, the viewer will not be able to understand and read it easily.

Kiyavash has an imaginary and invisible character named “Maziar” who is constantly talking to him. He has only recently mentioned this and revealed that even those close to him were not aware of this companion.

Kivayesh is a new and exciting addition to Iranian Art Brut.

21 x 29.8 cm

8.25 x 11.75 inches

21 x 29.8 cm

Kazem Ezi was born in 1933 in the village Ezi, in the central district of Sabzevar county.

He had primary schooling up till the fourth grade. He was always praised for his paintings by the school teachers, but he had to give up studying due to family necessities and his own epilepsy. He worked with his father and uncle helping in their profession follow their profession to repair oil heaters and lights. He traveled with his father everywhere for these jobs. Many of these trips were by bicycle and he loved to absorb the landscapes and architecture.

In 1954 and 1957 he went to on pilgrimages to alA'tabat al-Aliyat (cities such as Karbala, Najaf.. considered holy places by Shia Muslims) and began to illustrate what he had seen.

The establishment of the national railway line in Iran started when Kazem was only six years old (97 years ago) and ended after 11 years. But the implementation of this national project was faced with many obstacles, especially in the hometown of Kazem. It faced much opposition and demonstrations because Iran's nationwide railway was actually a military railway for the British Empire and not a commercial, transit or travel railway for Iranians. The British Empire built such railways in all its colonies, including India and African colonies.

We often see trains and train stations in Kazem Ezi's paintings in reference to these issues.

In 1989, while clearing snow from the roof of a school where he worked as a cleaner, he fell off by a strike to his head when he fell off and lost the use of an eye. But, perhaps coincidentally, his seizures stopped.

He has worked part time in the primary school of the village from 1972 to 2010. He got married and has two daughters and huis work has begin to be shown internationally.

For him drawing is a way of life review. He absorbs and remembers Place through his work. The drawings are imbued with his quiet daily spiritual meditations.

34.3 x 23.5 cm

KEz 1

Limoo Ahmadi was born in 1953 in Kermanshah, Iran. She learned kilim and carpet weaving at a very young age continuing with the art into her adulthood. She dropped out of school in the third grade. Her son was an art graduate but at the age of thirty he passed with a heart attack which affected her profoundly.

She fell into an existential crisis of doubt and depression. His painting supplies were still in their home and she began to use them as a way of distracting herself from the pain of his loss.

Color was a way of transcendance. She activates the surfaces by dotting and spotting them as if they were glittering in the sun but some of the forms hold a mystery with the slightest sense of foreboding. Often a smiling face shows her resilient resistance.

Her work can be seen as a way of touching joy with a color sense inspired by her experience with textiles. Through the process of artmaking she survives.

Based on information from Morteza Zahedi.

Mohammad Bannissi was born on January 3, 1992. He was a surviving twin. His early childhood years prior to primary school made Mohammad’s disabilities apparent and he began speech and behavior therapy under the supervision of specialists. At the age of 6 he was miraculously saved by doctors from severe meningitis.

He was forced to enter the special children’s program as experts did not deem him fit to study at the regular program. Later that year, he was had a heart operation and was kept at the special care unit due to obstruction in his lungs. At 14, his extensive stays at the hospital continued as he was operated on due to issues caused by the twist in his spine. Middle school was his last educational year, after which he began his artistic activities with the support of his parents.

It is interesting that so many of his drawings are about the structure of physical reality abstracted into color and lines. Banissi sometimes works from printed images but he diverts the subjects into abstracted complex compositions way more intricate than the originals. It is as if he has a way of reproducing our mundane dimensions and a more fantastic but impersonal dimension at the same time with his amazing control of color and negative spaces.

27.5 x 19.75 inches

x 50.2

27.5 x 19.75 inches

69.9 x 50.2 cm

Mahmood Zahedi (MahmoodKhan) was born in 1947. He graduated from school in 1968 and performed his military service in the village of Kelaveshk until 1970. He was employed by the National Bank for a while, but after a few months, he left the bank and joined the Ministry of Labor on a contract basis for six months. He went to Kerman to seek employment, but life and work in Kerman were not compatible with his spirit. He resigned his job and returned to Rasht where he participated in the recruitment exam for educators and after passing, he was sent to one of the villages around Rasht (Lashte Nesha) as a primary school teacher. He taught there for five years and finished the rest of his service in Khommam region. He got married in 1974, fathering four children. He retired from the Department of Education in October 2000 when he stayed home after an injury in the upper part of the spinal cord. Due to unsuccessful surgeries, which ultimately led to motor and sensory complications he became paralyzed till the end of his life.

MahmoodKhan started painting seriously on 20 December 2016. Painting slowly became a daily activity as it allowed him a solitary space to regard the world and pass time constructively in his difficult condition. He was a keen observer of the animal world and often used them as metaphors for aspects of the human condition, especially donkeys. He saw them as aspects of victimized humans, trapped and unhappy, constantly exploited and devoid of pleasures. He felt even sheep had some practical uses because they could be eaten and their wool was invaluable. The donkeys have no such uses and being treated cruelly was a natural facet of their lives. In a way MahmoudKhan’s rich colors and deceptively simple compositions give these animals a new dignity. By doing this he seduces us into being immediately sympathetic to them. We understand the stories this artist is telling and somewhere inside us and in our lives we know exactly what he means. By portraying them in

beautiful and striking colors he could hide the story of their harsh lives. Donkeys struggle till they are abandoned when no longer of use to their masters. Philosophically he saw them as representing our existential crisis. What is the purpose of a life like this. It is not difficult to see how he used these beasts to speak about himself and his predicament without having to verbalize it. He wrote this about the drawings: «Donkey is the head of the class of four-legged animals. In obeying and obeying the creatures at any time, place and position. It is believed that this animal has not learned to say «no» since birth and always says «yes» on its lips. This animal is a symbol of patience and resistance against oppression and injustice and never has any objection or claim. I think, for this reason, we Iranians use the name donkey in many proverbs to humiliate and mock each other. For example; you’re an idiot! Don’t understand the donkey! You brag like a donkey! You kick like a donkey! You are stuck in the mud like a donkey! The situation is dire! And... The only thing that a donkey is proud of and happy to have is having large testicles and a thick and sharp penis. That’s it and that’s it.» Knowing this, if we look at many of his other drawings we become aware of a tension and forboding in many of the beautiful settings. Survival is about fear and exploitation. Living beings constantly hunt and eat each other. A superficial glance may show happiness but the deeper need to overcome cruelty is part of human nature and often kept deeply hidden. Because of this MahmoudKhan is a Master storyteller whose work always reveals eternal truths. Over the span of his work he developed these animal metaphors. The act of painting and telling these stories allowed him to cope with his disabilities and produce meaningful and fulfilling work.

On November 15, 2023, he left us forever and his soul flew away and his body was buried on top of a hill in Gilan.

19.5

19.5

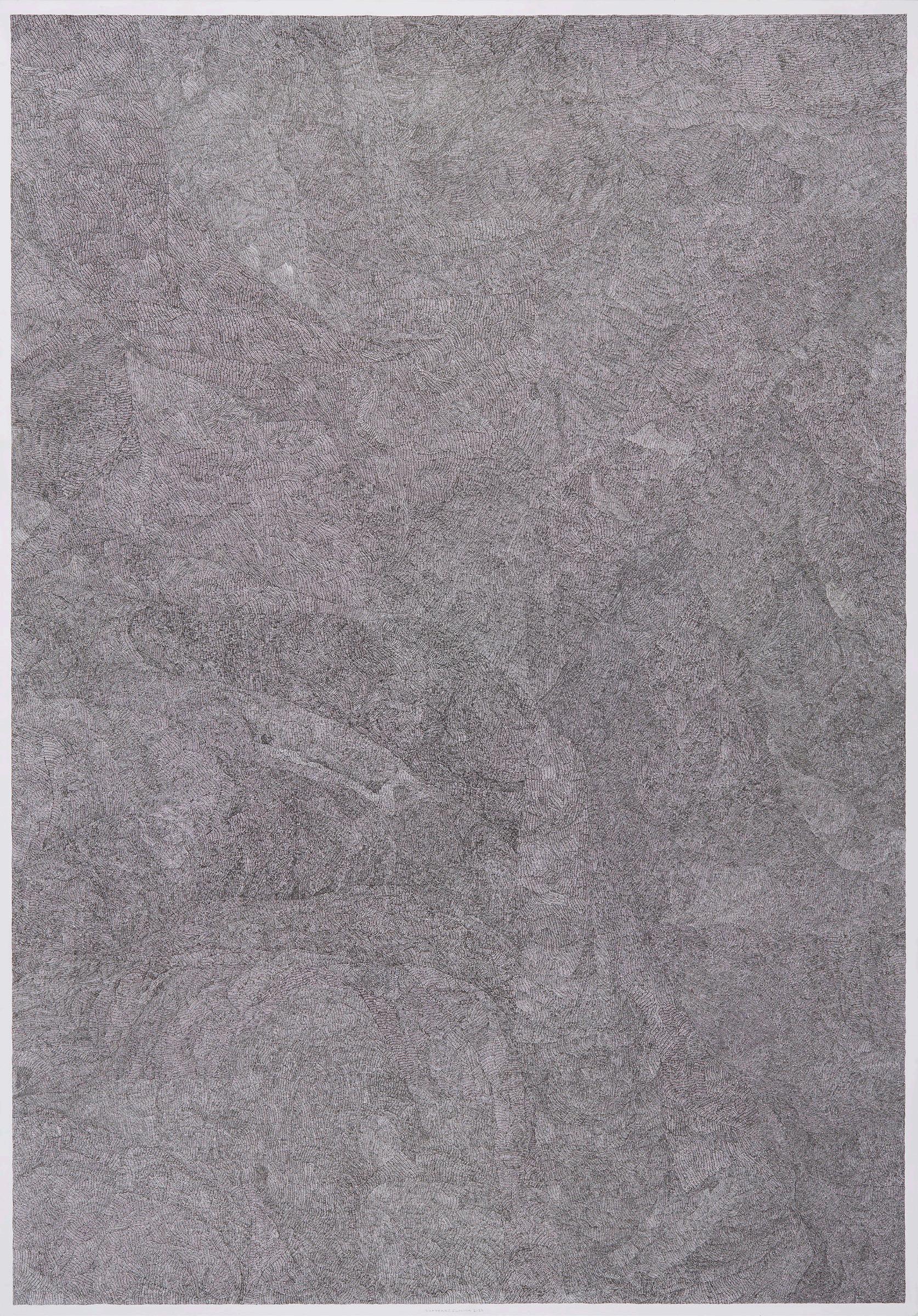

49.5 x 69.9 cm

Born with Downs Syndrome, Nazanin Tayebeh uses her drawings to expand her communication not only with others around her but also with an inner companion for whom the drawings become a dialog. It might even be herself she is writing and responding to. The relationship is often tranquil but there are times when the drawings explode into emotional tension. Films of her making art show these communications running through her expressions. She has created a personal, perhaps solipsistic language.....she does not verbally communicate. Like Joseph Lambert in Belgium she builds layers of selfinvented letters that move through a charged atmosphere. His drawings create topographies, hers create movement in light, but both artists use their marks to create a visual language that moves outward to communicate.

49.5 x 69.9 cm

19.5 x 27 inches

x 68.6 cm

19.75 x 27.75 inches

50.2 x 70.5 cm

19.75 x 27.75 inches

x 70.5

19.5 x 27.5 inches 49.5 x 69.9 cm

Sarvenaz Farsian was born in 1984. She came from jewelry making family and learned early onto see worlds in miniature, macrocosms caught and reproduced in microcosms. Jewelry is a time consuming, painstaking art and from this she learned to sharpen her focus.

Sarvenaz is obsessive about making work and often sits making her marks for ten hours at a time. She works with a black pen and has honed her detailed methodology over twenty years. Like the Czech artist Anna Zemánková, she immerses herself in the work which becomes a way of self-therapy and self-healing in drastic times. In her drawings she attempts to encompass nebulous spaces without the conceptual confines of narration. For her this is a demonstration of personal freedom in an environment where artmaking of any kind becomes a statement of cultural resistance.

In her own words she writes: My paintings begin from an unknown starting point, without any sketches or predictions. At the end of the work when I look at my painting from a distance, it is just like the end of one’s life in which the light and the darkness of each part are symbols of pain and joy.

The beginning and the ending

When I start drawing on a plain white surface of a canvas or paper is the moment of birth, and the moment I finish drawing is the loss of life. On this journey of life there are joyful moments and of course severities that are slowly formed in my paintings.

On the sad and happy times, I follow my instincts and just continue weaving the lines together. Each drawing take hours, and during this time I am not always the same. I review different periods of my life. Since I do not like to talk about my past and my childhood, doing so gives me a kind of peace of mind and I feel safe while painting. To me it’s Just like meditating.

I’ve always been attracted to the details. Tiny little things attract me. That’s why I choose the thinnest pen tip to draw. As the surface gets bigger and wider, my painting will be accompanied by more details. And with that, my patience will increase too. In fact, I’m happier to work on a larger scale. They are like a long life where more events happen. The forms that one might see in my work are all coincidental. Those forms sometimes even surprise me.

x 18.2

7.25 inches 25.4 x 18.4 cm

Alireza Maleki was born in 2003 in the village of Kolbar, Lorestan, Iran to a one cow owning family . He was a single child. He was very fond of cows and of bullfighting, he told Morteza Zahedi. He had looked at information about bullfighting in Spain as he worked in a traditional and semi-industrial slaughterhouse until he was recently kicked by a cow and stopped going. He is quiet and not very verbal.

His drawings are shocking with their rough power. His gaze is non-judgmental but he does not romanticize the place he spends so much time. There is a rhythm to the compositions even to the dots of red coming from the bodies of the cows and the variations of the colors of their skins. The people he places in the compositions are dwarfed by the hanging beef. They are ambiguous, is he portraying hell or taking a zen-like vision of something that happens everyday? They are vaguely threatening and yet in a sense the violence has already happened. Maliki’s work can be seen as classic Art Brut.

Biographical information informed by Morteza Zahedi

7.5 x 10.75 inches

19.1 x 27.3 cm

8 x 11.75 inches

20.3 x 29.8 cm

8.25 x 11.75 inches 21 x 29.8 cm

8.25 x 11.75 inches

21 x 29.8 cm

Zabihollah Mohammadi was born in 1941 in Malashir village of Lorestan. His father was an elder of the village with a poetic nature. He sent Zabihollah to a Mullah to be taught the Quran and the Sha’ahnameh. Zabihollah says: «My father wanted me to recite for him anything I had learnt from the Sha’ahnameh. And his persuasion made me more eager in learning.»

He studied the Sha’ahnameh over fifty years, and this immense book had much influence on his speech and manner, and also made his words rhythmic. When he read the Sha’ahnameh, the veins of his neck and the muscles of his face tensed up in his passion. This intensity showed up also in the poems he has composed. With the aid of this book he depicted the stories he heard of the Quran and the prophets purely, not knowing why he was drawing them and whether anybody would see or like his drawings.

Although his hands don’t let him work much, he held his paper and pens, his favored means, as tightly as a fearless child. He exchanged the sickle with colorful pens, and the farm with his corner of the house. He spent most of his time reading. Zabihollah was a storyteller with his own ways of composition and drawing and a personal script.

He loved the richness of storytelling, embellishing details in ornamental objects and clothing and figures almost woven together in their interactions. He made art because it needed to be made. His freedom came in the process of relaying the narratives for himself and for the stories of the prohets. His works were personal acts of spiritual reverence.

He passed on in 2021.

10 x 13.75 inches

25.4 x 34.9 cm ZM 6

16.5 x 11.25 inches

41.9 x 28.6 cm ZM 7

Abbas Mohammadi Arvajeh was born in 1942 in isfahan, Iran.

At a young age he became part of the carpet weaving community and tried to run his own business but he was unable to make it lucrative. When it closed he remained home mostly.

He took this failure very hard and personally.

From 2016 on he began to devote himself to painting on board and paper. In a sense painting gave him a comfort zone, a launching pad for his unrepressed imagination freed from the orthodox traditions of weaving. While expressing a fantasy world based on the colors and stories around him it also gave him a center of calm.

There is a mythos to his work fueled by light and graceful airborne human forms floating amidst sweeping atmospheres and plant life. Animistically they morph between male and female mythological beings, human, plant, and animal forms. There is no sense of self-defeat in his paintings. Art is his way of making magical possibilities external. For him as for so many others of these artists, the process of making this art defines the life of the painting in his eyes. Other than the making he has no other expectations for them in his reclusive life. They are his physical manifestations of time passing productively.

Information based on communication with Morteza Zahedi.

Mixed media on paper

27.5 x 19.75 inches

x 50.2 cm

Mixed media on paper

27.5 x 19.75 inches

69.9 x 50.2 cm

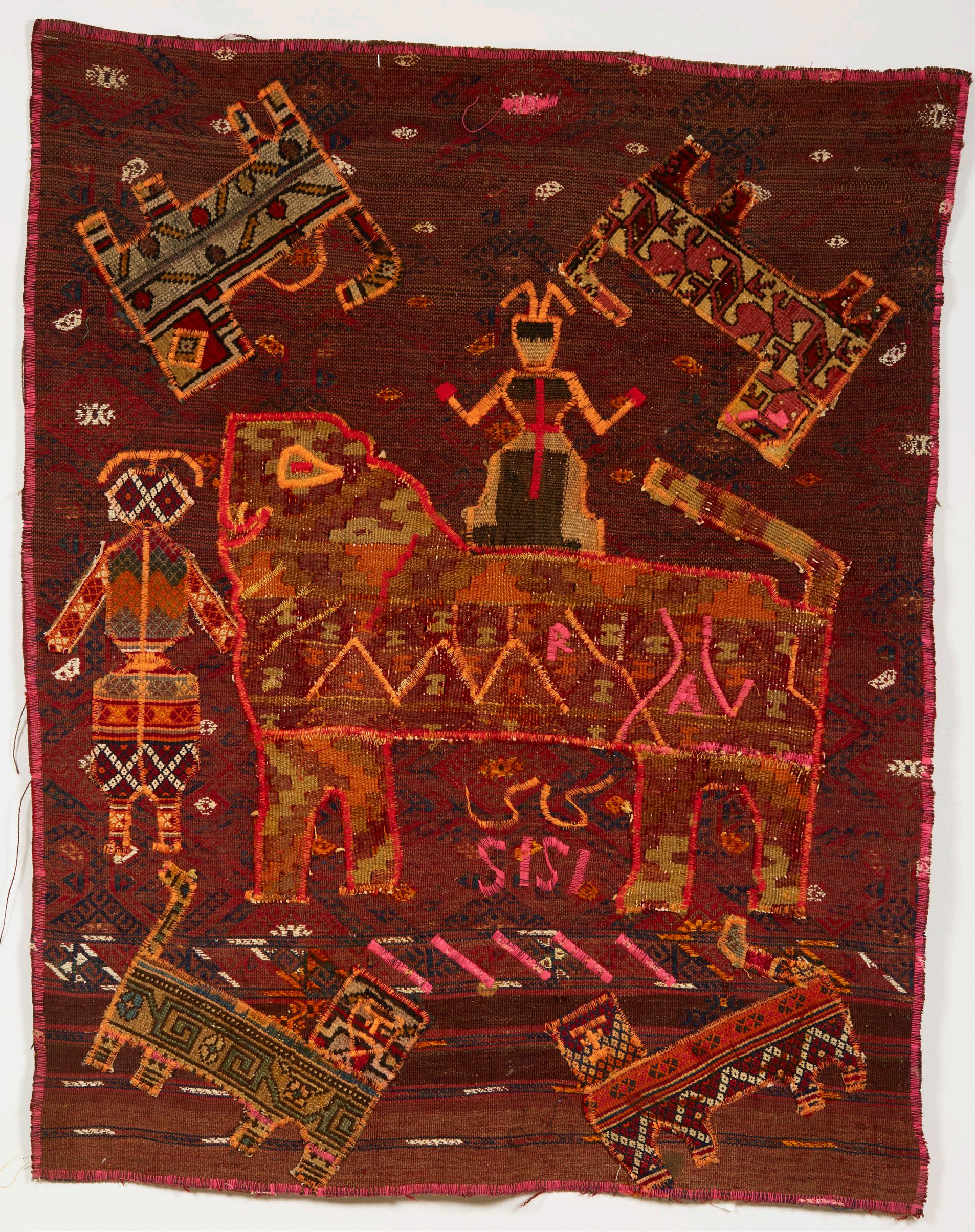

CC is the nickname of the artist Alireza Asbahi who was born in 1969 in the district of Emamzadeh Hassan, Tehran, into a rather large family. He attended school until the fifth grade, when his father died leaving him the responsibility of head of the family. He found work in a in a clothing manufacturing company in the Salsabil / Jumhori district. His father had been a tailor and it was in his blood. He collected kilims and crafts and sold them in the Jomeh Bazaar. In 2019 the Bazaar closed down and he could not sell there anymore.

He bought a used sewing machine to repair old frayed and torn rugs. His first pieces were experiments with collaging and layering the work as he learned to master his machine, For subject matter he used the traditional iconography of the Lion and the Sun, exploring its aesthetics and symbolism intertwined with Iranian history since the preIslamic era. His works are never decorative… they are rough and wild with the feeling of drawings as he never lost his respect for the process of the weavings themselves, expressionistically mixing patterns and subtle colors.

CC. has created a medium. He has internalized and personalized an ancient form and completely brought it forward in time without losing its grace and power. His style is immediately recognizable. It is exciting to present a form that is new to the art world.

Biographical information from notes by Morteza Zahedi

, 2019-2023 Fabric, marker on found rug

37 x 22 inches

94 x 55.9 cm

Fabric, marker on found rug

23.25 x 22.5 inches

59.1 x 57.2 cm

Fabric, marker on found rug

19.5 x 15 inches

49.5 x 38.1 cm

Fabric, marker on found rug

46 x 35.5 inches

116.8 x 90.2 cm

Ali Azizi was born in 1947 in Golpayegan, Iran.

Azizi owned a small fruit juice shop in the south of Tehran where he lived with his wife until he came down with cancer and could work any more. He was in much pain and being confined to home he began to paint to divert his mind from depression and physical discomfort. He began to create albums of found imagery: photographs, magazines, and cartoons. He refers to them when he paints but as can be seen in his vibrant, active works there is little relationship to any literal images.

He is a translator, an interpreter of twodimensional images into a crowded intense version of the world where all is ambiguous and unpredictable. His sense of color and composition have an almost textile-like patchwork feel to them. Despite the brightness and the anmated surfaces there is still a sense of unanswered mystery in the drawings. The process of making the work is more important than the results...the art is his savior.

Untitled, 2019-2022

Tempera on paper

19.75 x 14 inches

50.2 x 35.6 cm

5

Untitled, 2019-2022

Tempera on paper

27.5 x 19.75 inches

69.9 x 50.2 cm

60

27.5 x 19.75 inches

x 50.2 cm

19.25 x 13.75 inches

48.9 x 34.9 cm

19.6 x 13.75 inches

x 34.9

19.6 x 13.75 inches

x 34.9 cm

Approaching or introducing a body of what has been largely unseen work from a country always provides challenges. I mean this especially when the work is not made for or part of the Western artworld canon and demands of mainstream art. The work is often loosely or even poorly categorized, sometimes solipsistically relegated to its place of origin as its category, such as Haitian Art or Jamaican Art. Often the terms are outdated as in the case of the words; naïve, primitive or more recently; outsider. These are words that do not come from the intentionalities of the artists, nor do they succeed in any way at describing the art itself. Rather they clumsily attempt to pinpoint the artists. This is really an impossible thing to do as we shall see in presenting the tip of a vast iceberg of culture, geography, and individuals from Iran.

I learned this when I began to reappraise what I had seen and explored in Jamaica, Haiti, and my own country, the United States. I saw that as soon as one began to see one, two or three artists together there really was no universal way of putting it together. I did not want to trap them in inadequate academic cages. I could see that some painted narratives of time and place, some saw themselves as instruments of the spirits, some were travelers in their own minds, some were animistic, some were giving voice to social circumstances they could not express publically and those differences led me to try and find ways of approaching artists and works new to me with two questions. The answers to these questions satisfied most if not almost all of my needs as a traveler in these various human ecologies, to recognize the authenticities of different kinds of art

and artists I was interested in . If any of the answers to this questions were “the artworld or “mainstream art” then it was part of an entirely invalid system with its own histories and authenticities but it was not the art world I wished to be concerned with.

The questions are simply: Who was it made for? Why was it made.”

The universal part of these questions was that almost all the time it was made for self or for community; most often not an art community but a cultural community. Exceptions to the art community aspect do exist as in some Indian communities, or the artists who were supplied under the auspices of the Centre d’art in Haiti, or many of the communities of the First Nation Artists of Australia, or the Inuit and Eskimo North Americas.

The answer to why it was made is different but dovetails into the first question. It was made for self-healing or healing others, or to open channels for spirit communications. It was made as a proclamation of self, veneration of ancestors, animist communication with Nature and Place, as a form of prayer, as a way to exist as time passes, as a self-confirming way to endure, in some cases it was made as a personal way of having a means of living in a craft or market tradition.

But never was it made as part of a dialog with art history; never was it made as part of an ‘artworld’ movement, never was it part of an art world marketing trend.

The wide range of the artists of Iran is a perfect example of this.

Randall

Morris

COPYRIGHT © CAVIN-MORRIS GALLERY

PHOTOGRAPHY ... JURATE VERACITE

TEXT ... RANDALL MORRIS