CURATOR’S ESSAY

Before the rise of widespread craftivism in the early 2000’s, textiles and craft had been relegated to being forms of ‘low art’ due to craft being seen as women’s work, or domestic art. Now, textiles and fibre artists are using this often dismissed medium to examine feminism, environmentalism, inequality, anti-capitalism and more. Texture features both local and interstate, emerging and established, female textile and fibre artists that push their materials past their boundaries, with artworks that invite us to question, examine and explore all that textiles can do and be.

An installation of large crocheted artworks sprawl across the gallery floor and walls in the front gallery of Canberra

Contemporary Art Space, drawing visitors in with twinkling lights, soft tones and tactile nature. These playful textiles by Brisbane-based Chrys Zantis represent neurons, and are part of a larger body of work titled Internal Landscapes (2018), investigating the inner workings of the body.

Contrary to most gallery guidelines, these works are meant to be touched and interacted with, bringing much delight to gallery visitors. Three ‘Cuddle Neurons’, in tones of grey, blue, cream and mustard, were created specifically to embrace. Their long dendrite ‘arms’ designed to cuddle you back, eliciting the love hormone oxytocin. The ‘Mother Neuron’ and her three ‘neuron babies’ dominate a gallery wall, their heavy wool dendrites reaching out to one another while subtle, small lights within each structure glow and fade, mimicking the electrical impulses being transmitted through the brain and body.

Thematically Zantis’ works sit in good company alongside Multispecies Patchwork (2023), by Canberra artist Alia Parker Parker’s wall piece is unassuming with its muted colours and domestic quality, but it hangs quietly and confidently as the perfect interweaving of biology and design. Parker has used mushroom mycelium to create her patchwork panels (comparable to large fabric petri dishes), in a careful exercise of guiding the mycelium growth across textile offcuts to create a unique and expressive pattern, and then sealing the design with agar bioplastic.

Following page:

Chrys Zantis

Cuddle Neurons as part of Internal Landscapes, 2018 (Texture installation photograph)

Acrylic yarns, pillow, battery operated fairy lights, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Exploring environmentalism and sustainability, an important idea in this work is of the polysemous ‘patch’. A patch mends or strengthens damaged clothing; it can also be used to treat and protect injuries. When investigated in a more worldly context, this work according to the aritst “considers the possibilities of textile and more-than-human patchwork as a methodology to contemplate ways of caring for a damaged planet.” Parker’s experimental practice signifies an important shift in how we expand the so-called ‘boundaries’ of textiles and sustainable design through science-based investigation.

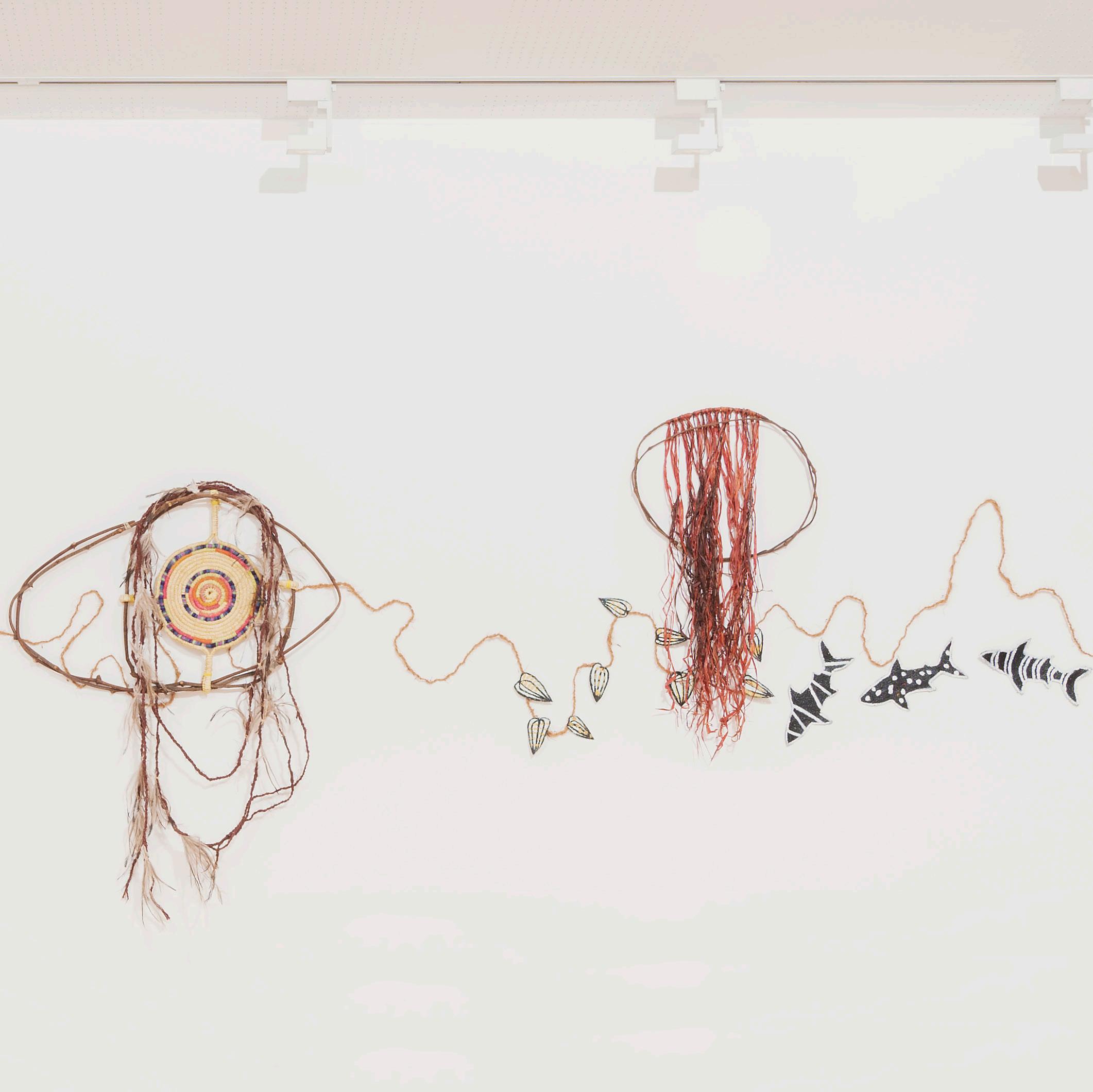

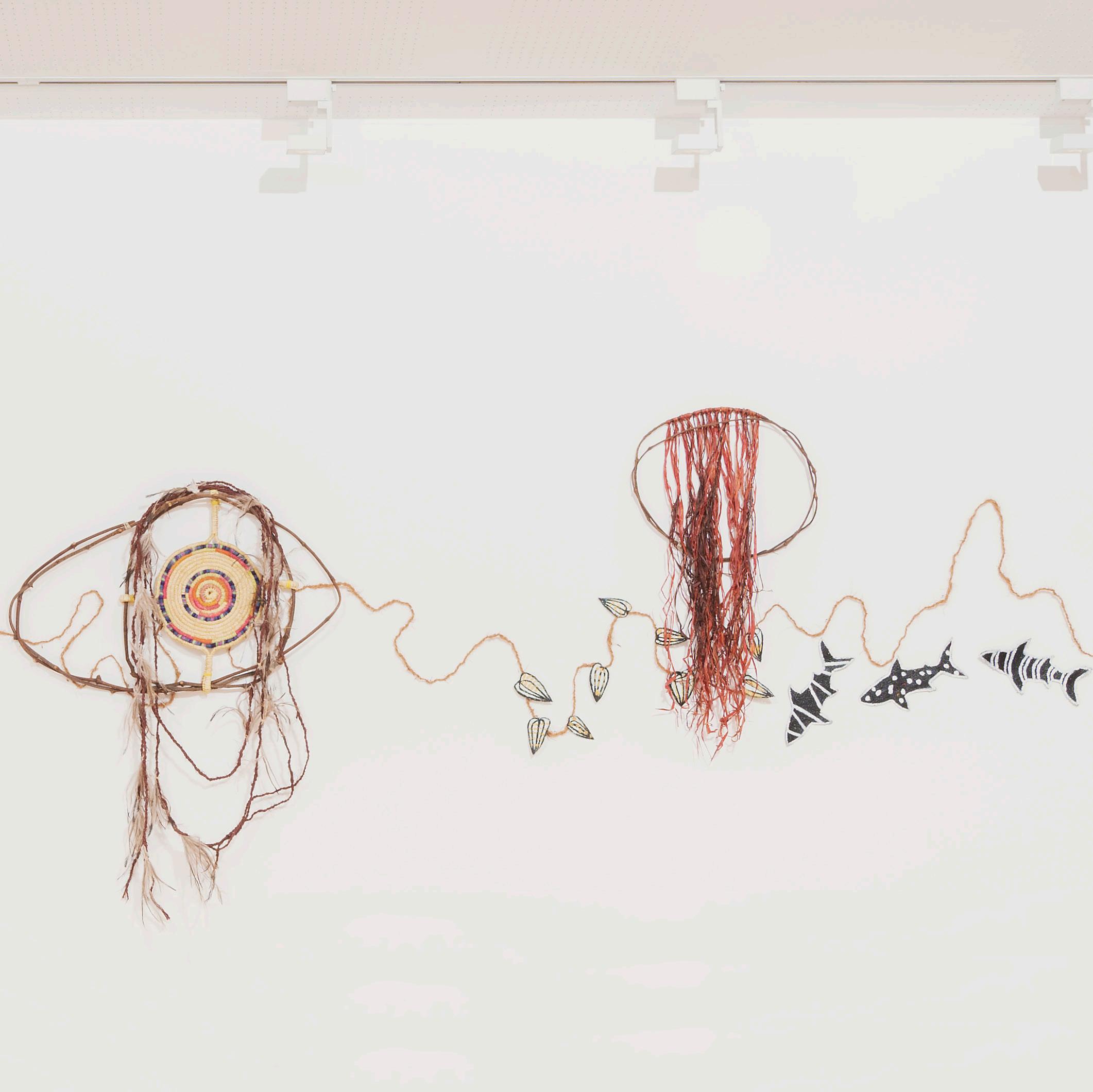

In contrast to Zantis and Parker’s scientific approach, Nadeena Dixon’s earthy, fibrous, found object installation speaks directly to her culture as a Wiradjuri, Yuin and Gadigal (Dharug -Boorongberigal clan) woman. Dixon’s work Untitled (2023), comprises of a single line of coconut fibre that traverses the gallery wall like a flowing river, with hand crafted pippies, fish and sharks dotted along it. Two dilly bags flank the work, which also features thick vines and Emu feathers. Recognised as a master weaver within First Nations Australian textile traditions, Dixon is a multi-disciplinary artist who has a strong focus on creating fibre sculpture works, and incorporating and imparting Indigenous knowledge.

When installing her work, Dixon approached the empty wall with self-assured enthusiasm: she said as she nailed the lengths of coconut fibre into its meandering design, “it tells me where it needs to be.” Dixon’s intuitive process also includes culturally significant totems in this work: a vine wrapped in a colourful weaving, representing the eye of the Rainbow Serpent, commanding the centre of the work. This installation is exemplary of how Dixon weaves Indigenous symbolism throughout her work, an important part of her practice that she then shares with her audiences.

Jane Bodnaruk’s Portraits of Care (2023) shares stories of care and nurture through six vignettes of skeleton clothes, manipulated muslin, and cloths. Bodnaruk’s interrogation of ‘care’ started with exploring the role textiles play in the home. Bodnaruk began by acquiring and utilising second-hand women’s shirts; the careful selection of each one was guided by colour and the hand of the fabric, after which the fabric was stripped from the structural seams and used as a raw material.

With each of her vignettes, Bodnaruk illustrates how care can be given, taken; provided by many or by one; how some care is hidden, and how sometimes we may try to mend things, but the damage is irreparable. Bodnaruk’s investigation into care and nurture is a timely one, as so many of us struggle out of the Covid-19 stupor and reassess how we care for one another, while caring for ourselves.

Chrys Zantis

Internal Landscapes, 2018 (Texture installation photograph)

Acrylic, wool and cotton yarns, armature wire, bias binding, cable ties, electric fairy lights, bean bag filling, pillow, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

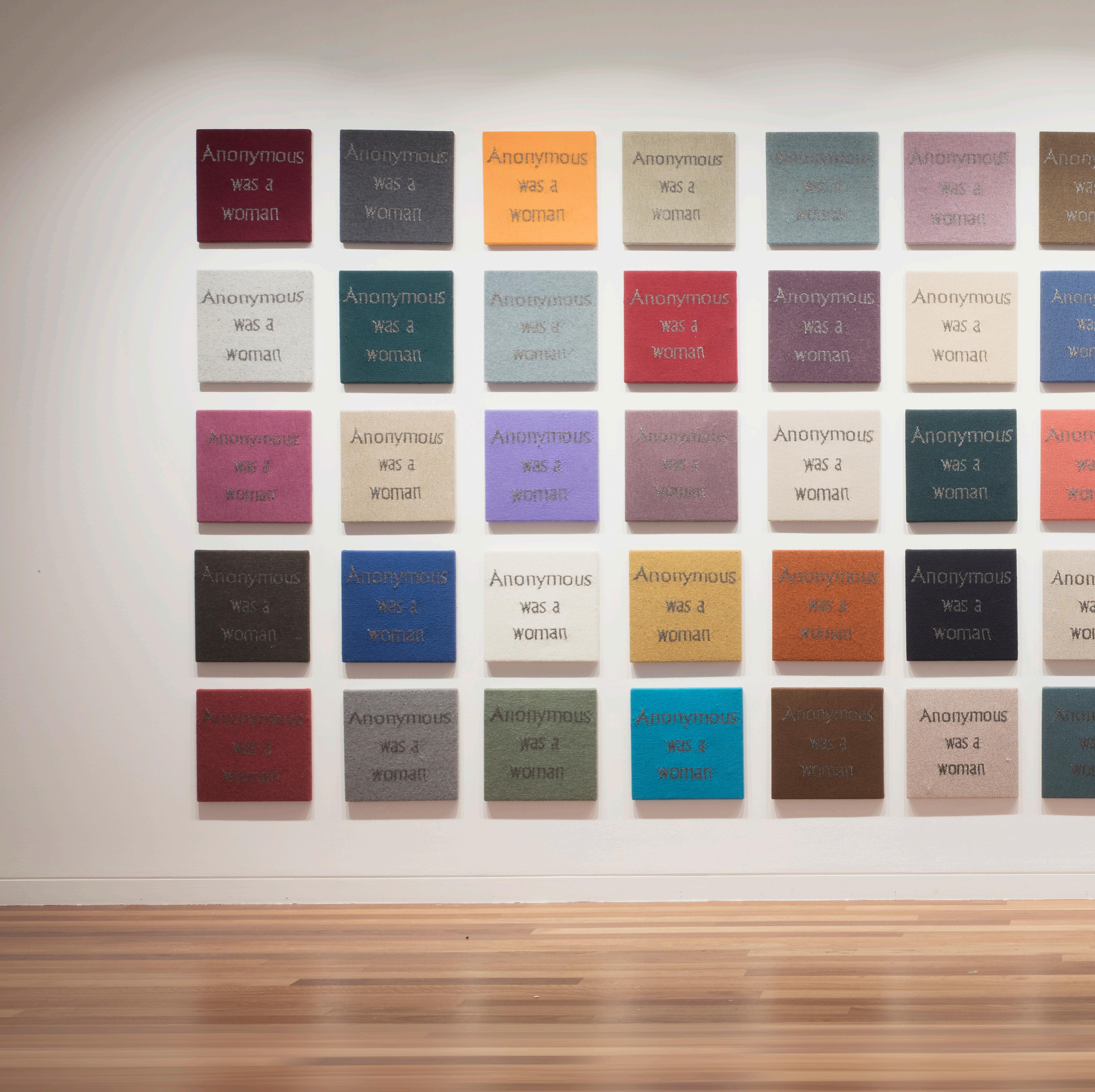

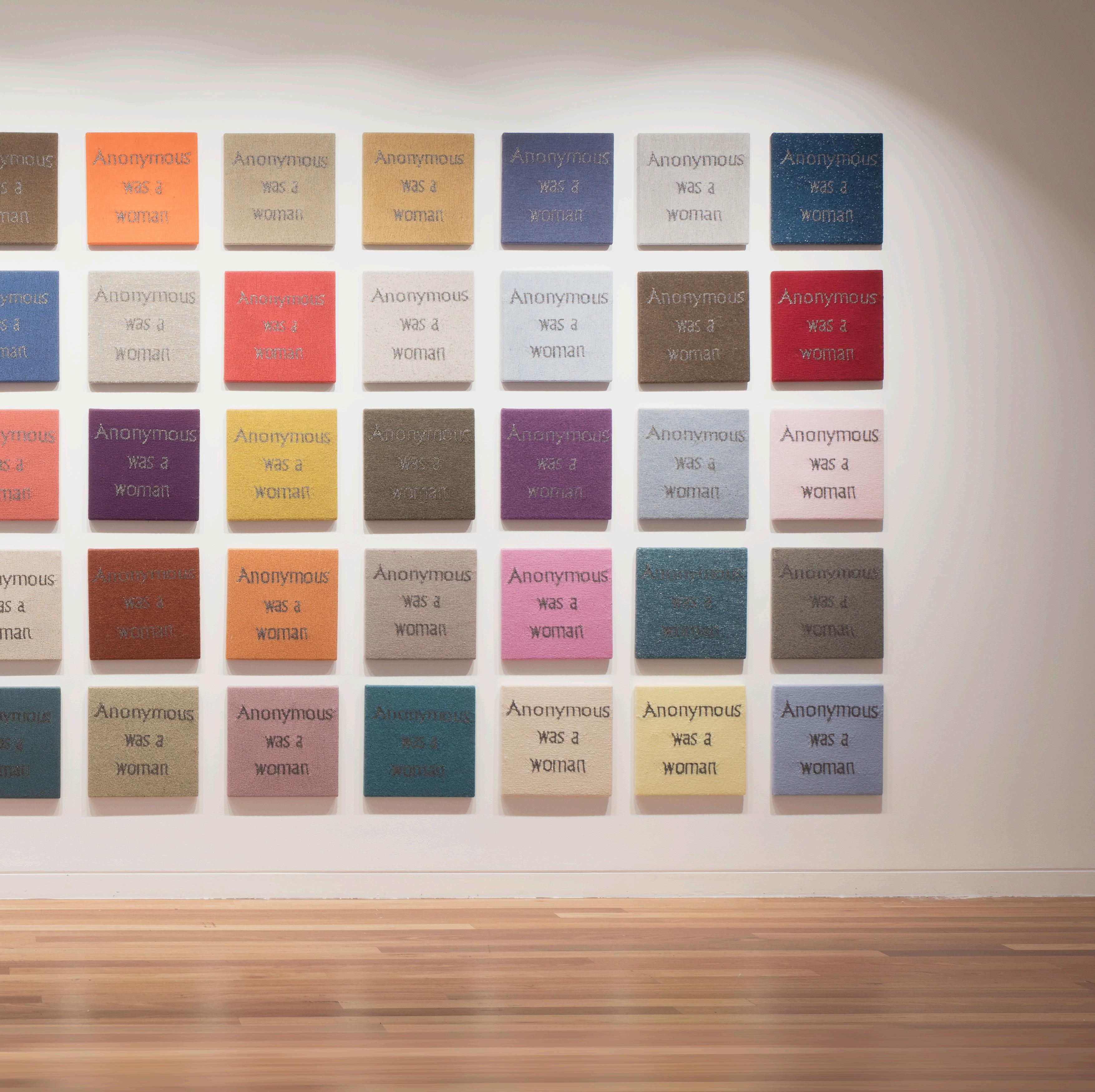

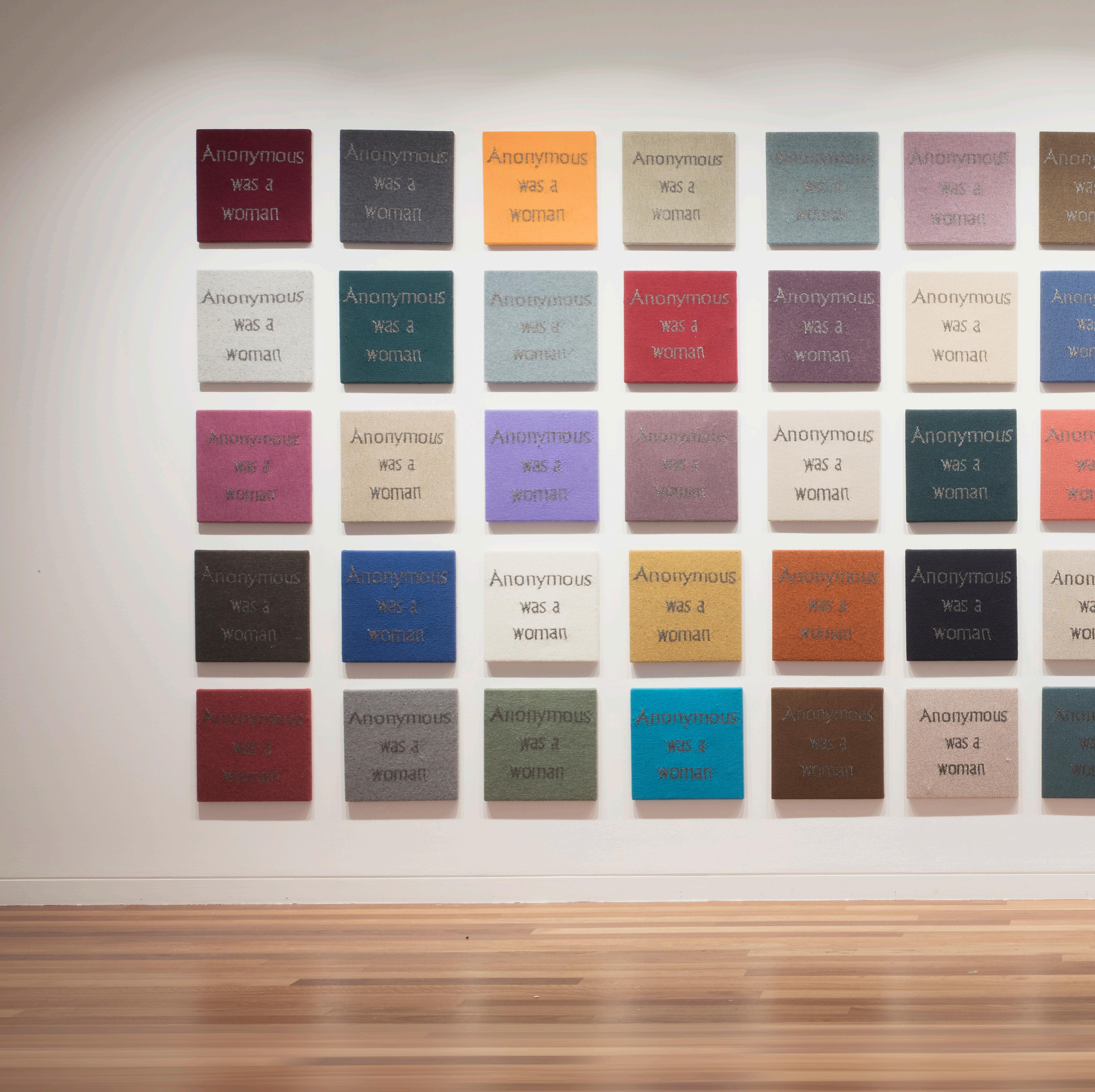

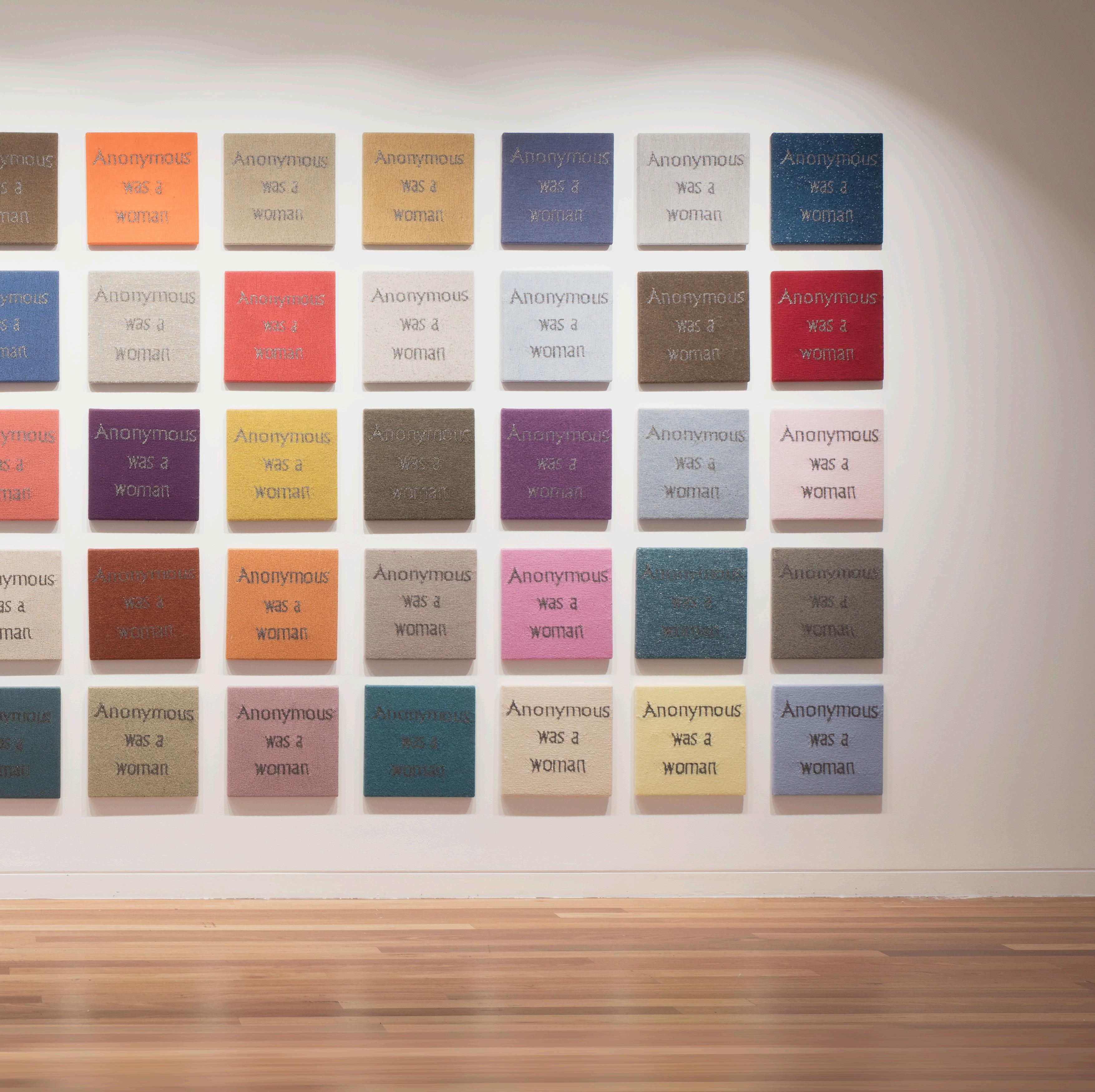

Care, traditionally, is seen as a feminine undertaking, and its importance is often dismissed. This is echoed in the work placed directly opposite Bodnaruk in the back half of the gallery. Kate Just’s imposing wall of 65 hand knitted panels which each proclaim ‘Anonymous was a woman’ stands like a columbarium, as a monument to countless overwritten and lost female voices. This is only a portion of the Anonymous was a woman project that started in 2019, and in total comprises 140 panels and two million stitches. Renowned for her feminist artworks, this is a prime example of Just’s practice, which investigates female and queer representation using knitting as a political tool.

Anonymous was a woman is inspired by a quotation in Virginia Woolf’s book A Room of One’s Own (1928). In this feminist polemic, Woolf questions the ways women’s authorship has been judged as inferior to that of men, and systematically made invisible. Woolf says, “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.”1 Over time this quote has been rephrased as “throughout most of history, Anonymous was a woman.” Through the making of the work, Just meditates upon the immeasurable contributions that women have made to culture and society, and mourns the losses sustained by the erasure or exclusion of many of these gifts from the canon of art history.

Another monument to women in this exhibition is Nautical Map (2017) by Haji Oh. Oh is a third-generation Zainichi Korean artist who now lives in Wollongong, and draws on her multicultural background to inform her practice. The delicate yet vast installation uses the gallery’s high ceiling and columns to create an all-enveloping display of contemporary textile art. This work of weaving and threads is Chapter 1 of Oh’s Grandmother Island Project, which the artist describes as “an imaginary and multisensory space that reveals the interconnectedness of untold stories.” The series follows the trajectories of people who have crossed the seas between Australia, Japan and South Korea, and are connected through space and place.

With Nautical Map, Oh utilises a traditional Guatemalan technique on a backstrap weaving loom, as well as dying the warp threads to create the shape of the mountains and islands. Nautical Map consists of three textiles, representing Jeju Island in Korea, Thursday Island in Queensland, and Mt. Kiera in Wollongong. Conceptually the textiles and threads in the installation work as anchors and signposts in Oh’s imaginary space, guiding individual narratives through this temporarily manifested realm. This work explores the narratives of women and of those forgotten and investigates the untold stories of those who are intrinsically connected to the artist through memory and time. Using the weavings as a map to traverse space and place, Oh invites visitors to walk amongst the installation on their own exploratory journey.

Alia Parker

Multispecies Patchwork, 2023

Agar Bioplastic, textile fragments and mushroom mycelium, 156 x 156cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Above:

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture showcases how textiles are an important part of our social fabric, as a vehicle that communicates personal stories and political ideologies through art. Its broad range of mediums, techniques and processes make textile art a genuinely democratic form of material language, and one that provides a model for inclusivity, while exemplifying methods of crosspollination. Often sidelined as ‘hobbyist’ or ‘amatuer’ due to its traditional gendered origins, textile and fibre art is now buoyed by institutional attention, and thankfully will remain a quiet, constant force in contemporary art.

Dan Toua

Curator

February 2023

Left: Jane Bodnaruk

Portraits of Care, (detail) 2023

Second-hand clothes, muslin, tulle, wool roving, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Following Page: Jane Bodnaruk

Portraits of Care, (detail) 2023 (Texture installation photograph)

Second-hand clothes, muslin, tulle, wool roving, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

1. Woolf, Virginia. 2004. A Room of One’s Own. London: Penguin, 2004.

Jane Bodnaruk

Portraits of Care, 2023 (Texture installation photograph)

Second-hand clothes, muslin, tulle, wool roving, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Haji Oh

Nautical Map, 2017 (Texture installation photograph)

Linen, lead, hooks, plain-woven, four-selvaged cloth, warp-faced pick-up pattern, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Haji Oh

Nautical Map, 2017 (Texture installation photograph)

Linen, lead, hooks, plain-woven, four-selvaged cloth, warp-faced pick-up pattern, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Kate Just

Anonymous was a woman, 2019-21 (Texture installation photograph)

65 panels, (41 x 41cm each), hand knitted wool and acrylic yarns, timber, canvas, dimensions variable

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Untitled, 2023 (Texture installation photograph)

Coconut fibre, emu feathers, vine, plastic, cotton thread, acrylic paint, dimensions variable

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Untitled (detail), 2023 (Texture installation photograph)

Coconut fibre, emu feathers, vine, plastic, cotton thread, acrylic paint, dimensions variable

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Untitled (detail), 2023 (Texture installation photograph)

Coconut fibre, emu feathers, vine, plastic, cotton thread, acrylic paint, dimensions variable

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

CURATED BY DAN TOUA

CURATED BY DAN TOUA

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Texture installation photograph

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Nadeena Dickson

Photo by Brenton McGeachie