Cryotherapy in Endodontics Chronic Disease Management

DECEMBER 2022 Vol 50 n Nº 12 Persistence and Commitment: Unparalleled Advocacy in 2022 — A Game Changer for Vulnerable Californians

Journa CALIFORNIA DENTAL ASSOCIATION December 2022

coverages

agent or broker

agreements with our partner insurance carriers. Eligibility, available coverage limits and discounts vary

carrier

carrier underwriting.

provided

overview of the referenced product and is not intended to be a complete description of all

states.

Street, 17th Floor, Sacramento, CA 95814 | TDIC IS CA Lic. #0652783 Insurance coverage

issued by Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, 200 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10166. Like most group benefits programs, benefit programs offered by

contain certain exclusions, exceptions, waiting periods, reductions, limitations and terms for keeping them in force. Ask your plan administrator for costs and complete details. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company |

Avenue

York, NY 10166 | L0522022773[exp0524][All States][DC,GU,MP,PR,VI] © 2022 MetLife Services and Solutions, LLC. Protection for every stage of life and practice. The coverage you need at affordable MetLife group rates. DISABILITY COVERAGE Protect your investment in your profession by preparing for unexpected injuries or illnesses. Plus coverage from leading carriers. HEALTH COVERAGE Keep yourself, your family and your whole team well. Find affordable Individual & Family and Small Group plans from trusted carriers. LIFE INSURANCE Easily add extra protection or change coverage levels to secure your loved ones’ peace of mind and future financial well-being. Benefits paid even if you can work but can’t practice dentistry Great rates for CDA members through a MetLife group plan INSURANCE SOLUTIONS Learn more online at tdicinsurance.com/solutions Call your local TDIC Insurance Solutions advisor at 800.733.0633 Scan here to get started: Flexible choice of benefit periods and maximum benefits Financial security with up to 60% of your income covered

TDIC Insurance Solutions offers other

as an

by

by

and are subject to

The information

here is an

terms, conditions and exclusions. Not available in all

TDIC Insurance Solutions | 1201 K

is

MetLife

200 Park

| New

departments

The Editor/Student Debt: American Dream or American Nightmare

Thank You to 2022 Journal Reviewers

Impressions

RM Matters/Digital Accessibility Lawsuits Are on the Rise: Is Your Website AwDA Compliant?

Regulatory Compliance/What Prescribers Should Know

Tech Trends

Index to 2022 Articles

Persistence and Commitment: Unparalleled Advocacy in 2022 — A Game Changer for Vulnerable Californians, a Commentary

CDA advocated tirelessly for targeted investments to improve dental pipeline opportunities and expand apprenticeship programs to address the dental staff shortages being experienced across the state.

Jared I. Fine, DDS, MPH

Cryotherapy in Endodontics: A Critical Review

This paper reviews the applications of cryotherapy in endodontics including its effects on post-endodontic pain, effectiveness against endodontic infections, hazardous effects on dentin and efficacy on cutting efficiency of Ni-Ti rotary instruments.

Zahed Mohammadi, DDS, MSc; Sousan Shalavi, DDS; and Hamid Jafarzadeh, DDS, MSc

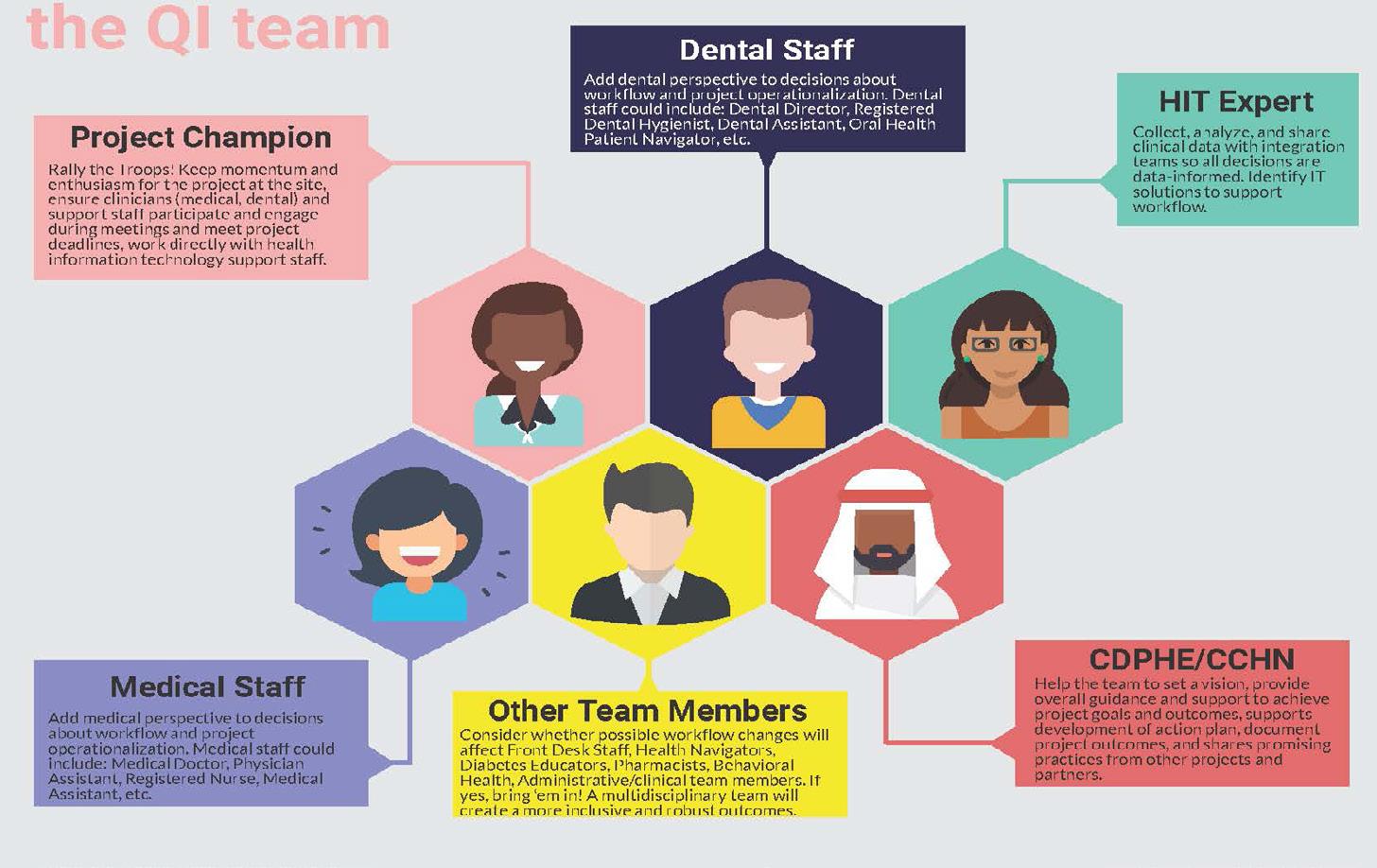

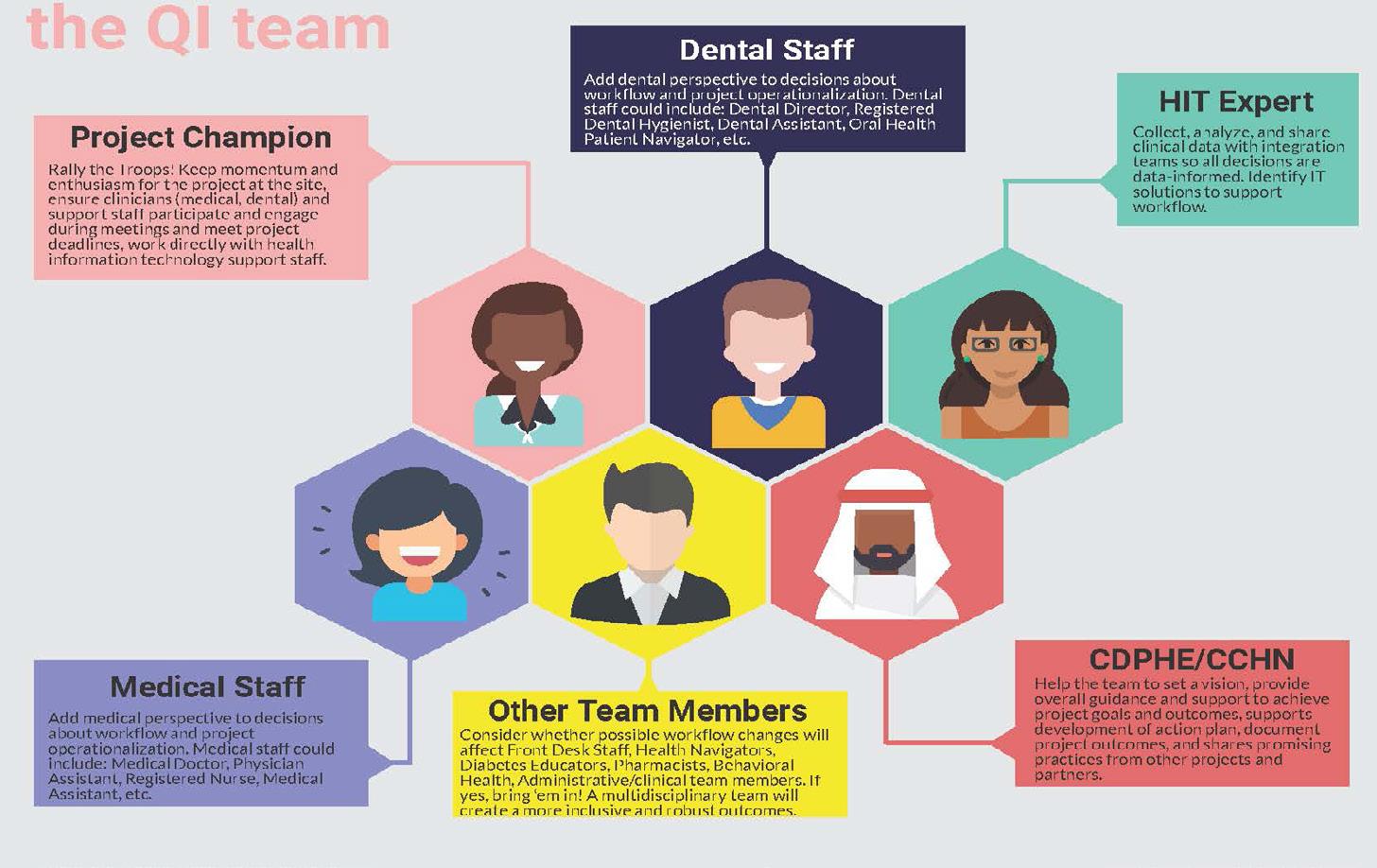

Integrated Approaches to Preventing and Managing Chronic Diseases: Colorado’s Diabetes Cardiovascular Disease Oral Health Integration Program

This paper describes Colorado’s integration strategies for leveraging clinical safety net and public health workforces to address the most pressing health care needs of underserved communities, with a focus on preventing and managing (pre)diabetes, (pre)hypertension and oral diseases.

Katya Mauritson, DMD, MPH(c); Sara Grassemeyer, MPH; Ian Danielson, MPA; and Abby Laib, MS

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 DECEMBER 2022 711

DEC. 2022

719

features 717

715 727 733 C.E. Credit 745 719 753 755

749 723

published by the California Dental Association

1201 K St., 14th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 800.232.7645 cda.org

CDA Officers

Ariane R. Terlet, DDS President president@cda.org

John L. Blake, DDS President-Elect presidentelect@cda.org Carliza Marcos, DDS Vice President vicepresident@cda.org

Max Martinez, DDS Secretary secretary@cda.org

Steven J. Kend, DDS Treasurer treasurer@cda.org

Debra S. Finney, MS, DDS Speaker of the House speaker@cda.org

Judee Tippett-Whyte, DDS Immediate Past President pastpresident@cda.org

Journa

CALIFORNIA DENTAL ASSOCIATION

Management

Peter A. DuBois Executive Director

Carrie E. Gordon Chief Strategy Officer

Alicia Malaby Communications Director

Editorial

Kerry K. Carney, DDS, CDE Editor-in-Chief Kerry.Carney@cda.org

Ruchi K. Sahota, DDS, CDE Associate Editor

Marisa Kawata Watanabe, DDS, MS Associate Editor

Gayle Mathe, RDH Senior Editor

Andrea LaMattina, CDE Publications Manager

Kristi Parker Johnson Communications Manager Blake Ellington Tech Trends Editor

Jack F. Conley, DDS Editor Emeritus

Robert E. Horseman, DDS Humorist Emeritus

Production Danielle Foster Production Designer

Upcoming Topics

January/Public Health Initiatives

February/General Topics March/Oral Appliances

Advertising Sue Gardner Advertising Sales Sue.Gardner@cda.org 916.554.4952

Volume 50 Number 12 December 2022

Permission and Reprints

Andrea LaMattina, CDE Publications Manager Andrea.LaMattina@cda.org 916.554.5950

Manuscript Submissions

www.editorialmanager. com/jcaldentassoc

Letters to the Editor www.editorialmanager. com/jcaldentassoc

Journal of the California Dental Association Editorial Board

Charles N. Bertolami, DDS, DMedSc, Herman Robert Fox dean, NYU College of Dentistry, New York

Steven W. Friedrichsen, DDS, professor and dean emeritus, Western University of Health Sciences College of Dental Medicine, Pomona, Calif.

Mina Habibian, DMD, MSc, PhD, associate professor of clinical dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles

Robert Handysides, DDS, dean and associate professor, department of endodontics, Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, Loma Linda, Calif.

Bradley Henson, DDS, PhD, interim vice president research & biotechnology, associate dean for research and biomedical sciences and associate professor, Western University of Health Sciences College of Dental Medicine, Pomona, Calif.

Paul Krebsbach, DDS, PhD, dean and professor, section of periodontics, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Dentistry

Jayanth Kumar, DDS, MPH, state dental director, Sacramento, Calif.

Lucinda J. Lyon, BSDH, DDS, EdD, associate dean, oral health education, University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, San Francisco

Nader A. Nadershahi, DDS, MBA, EdD, dean, University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, San Francisco

The Journal of the California Dental Association (ISSN 1942-4396) is published monthly by the California Dental Association, 1201 K St., 14th Floor, Sacramento, CA 95814, 916.554.5950. The California Dental Association holds the copyright for all articles and artwork published herein.

The Journal of the California Dental Association is published under the supervision of CDA’s editorial staff. Neither the editorial staff, the editor, nor the association are responsible for any expression of opinion or statement of fact, all of which are published solely on the authority of the author whose name is indicated. The association reserves the right to illustrate, reduce, revise or reject any manuscript submitted. Articles are considered for publication on condition that they are contributed solely to the Journal of the California Dental Association. The association does not assume liability for the content of advertisements, nor do advertisements constitute endorsement or approval of advertised products or services.

Copyright 2022 by the California Dental Association. All rights reserved.

Visit cda.org/journal for the Journal of the California Dental Association’s policies and procedures, author instructions and aims and scope statement.

Connect to the CDA community by following and sharing on social channels

@cdadentists

Francisco Ramos-Gomez, DDS, MS, MPH, professor, section of pediatric dentistry and director, UCLA Center for Children’s Oral Health, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Dentistry

Michael Reddy, DMD, DMSc, dean, University of California, San Francisco, School of Dentistry

Avishai Sadan, DMD, dean, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles

Harold Slavkin, DDS, dean and professor emeritus, division of biomedical sciences, Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles

Brian J. Swann, DDS, MPH, chief, oral health services, Cambridge Health Alliance; assistant professor, oral health policy and epidemiology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston

Richard W. Valachovic, DMD, MPH, president emeritus, American Dental Education Association, Washington, D.C.

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 712 DECEMBER 2022

Renew today at cda.org/renew renew EDUCATION RESOURCES RESEARCH ADVOCACY PROTECTION SUPPORT SAVINGS EXPERTISE CONNECTION EDUCATION RESOURCES RESEARCH ADVOCACY PROTECTION SUPPORT SAVINGS EXPERTISE Is your membership set for 2023? Don’t wait to lock in benefits built just for California dentists. Access one-on-one expert guidance, engaging C.E. across learning formats, tools that save time and money, and constant connection to trusted news and resources. It’s easy to pay dues online or choose convenient monthly payments. YOUR MEMBERSHIP ®

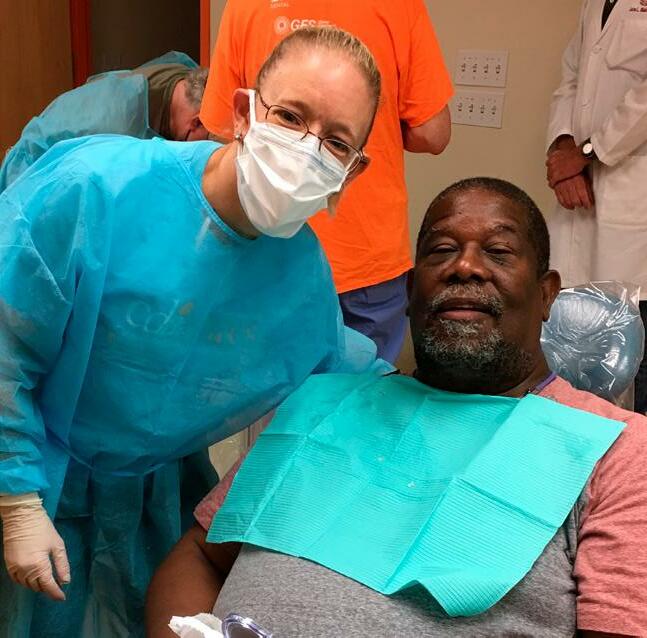

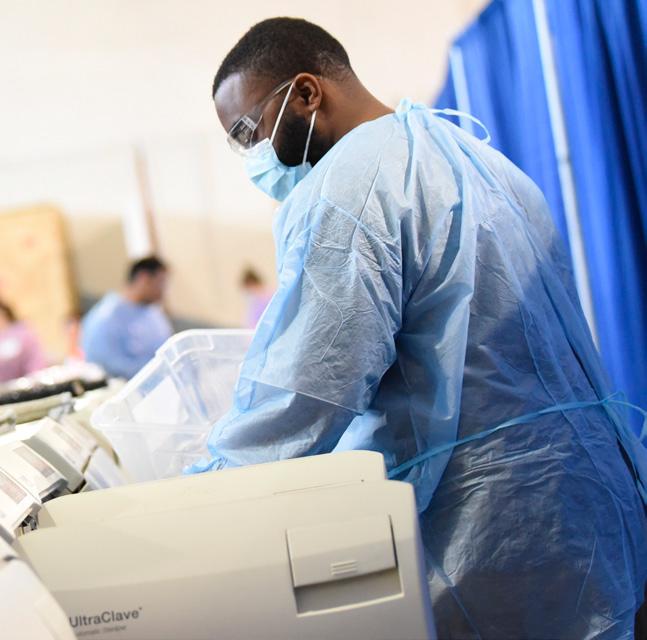

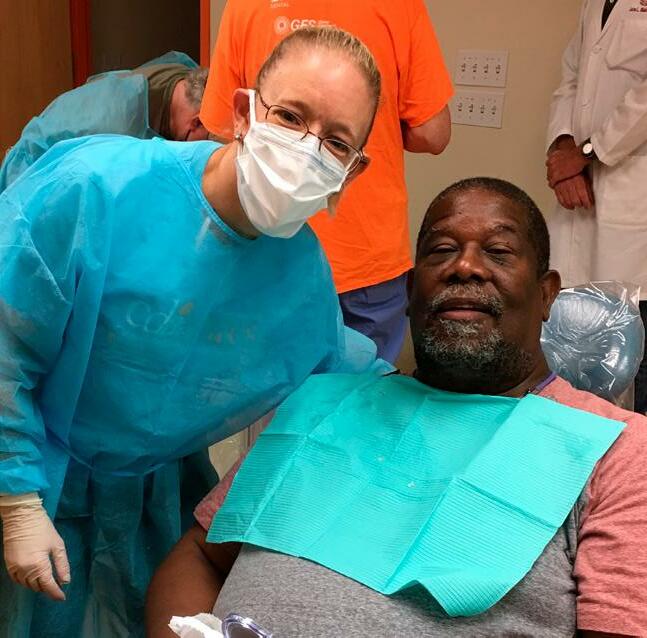

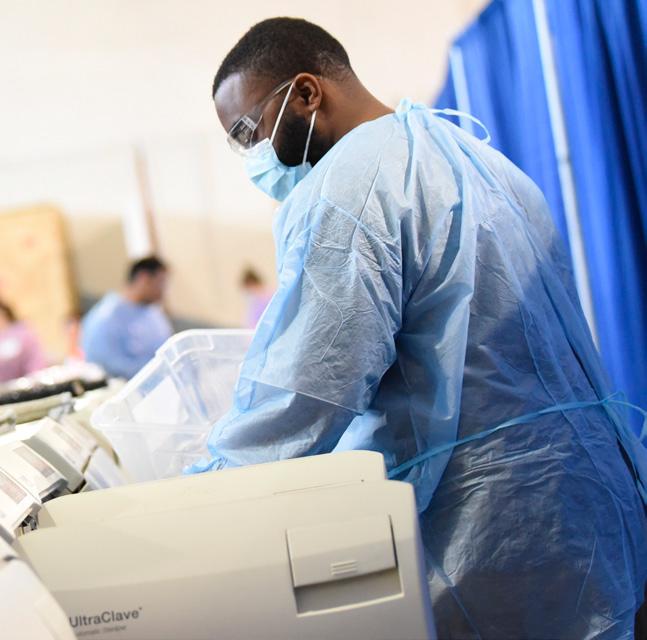

Create smiles. Change lives.

CDA Foundation volunteers and donors truly change the lives of others. Through your generosity, Californians in underserved communities gain access to dental treatment that relieves pain, restores dignity, creates smiles and opens more opportunities.

.

See ways to give at cdafoundation.org

Student Debt: American Dream or American Nightmare

Kerry K. Carney, DDS, CDE

Sometimes you can stew about something for a long time and never quite put your finger on the problem. That happened to me this weekend when I read an article by Ron Lieber about student loans and why they are so complicated.1 It made me wonder how paying for a dental education could have spiraled so completely out of control like a top that’s lost its momentum. It made me look at the world a generation ago and compare it with the world that new dentists graduate into now.

I remember chatting with a new dentist at a meeting more than 10 years ago. He told me his debt was over $250,000 and that he would be paying it off over 20 years. He was making payments of about $4,000 a month. That seemed like a mortgage payment to me, but after the loan was repaid, there would be no house, nothing tangible. Funds directed toward the repayment of student loans over 20-25 years diverts money that could have (should have) been invested or saved for retirement. (Where is that reverse mortgage for your dental education?)

It made me think about my motivations to pursue a degree in dentistry all those years ago. A degree in dentistry would require an investment of my time and my efforts in exchange for a profession that helped me to help others. Also, it would provide more financial stability than many other careers I had considered. Though the training was difficult, it was well worth my investment.

Committing to a huge debt that would take decades to pay off was not part of the decision-making then. If I were considering it today, it would give me pause. Many of us were brought up to avoid going into debt on

pain of death. Grants, scholarships, work/ study and side jobs were how some of us made it through school. The indebtedness hurdle can turn away good applicants who haven’t sufficient assets or access to assets or who just do not have the support system or confidence to overcome that barrier.

According to reports, the tremendous debt burden of new dentists influences many life decisions they may weigh: where they choose to practice, what kind of practice to join, whether to specialize, enter into public health or academia. Student loan debt even influences decisions about whether or when to begin a family. Buying a practice or starting a practice from scratch may not be possible for a new dentist already laboring to repay student debts.

There is so much money tied up with educational loans it should be a national embarrassment.

“Average educational debt for all indebted dental school graduates in the class of 2021 was $301,583, with the average for public and private schools at $261,226 and $354,901 respectively.”2 There are 70 accredited dental schools in the United States.3

In 2021, 6,665 students graduated from dental schools in the U.S. An American Dental Education Association (ADEA) report states that a little over 17% of the graduating students reported no debt. That seems to indicate the class of 2021 owed a

total of $1,668 million or $1.7 billion dollars. Does anyone else think something is wrong here?

New dentists in the ‘80s were beneficiaries of government programs that gave financial support to dental schools. We were seeking higher education in a time when there was a “general good” social contract. The idea was that those who improved themselves through higher education would eventually more than make up for the subsidies the country had provided for that education.

It was expected that we would provide increased services and pay higher taxes based on our higher incomes. We were encouraged and supported monetarily so that when we became contributing members of society, we would be part of the improvement of conditions for everyone. Later, these government subsidies were phased out as the burden of the cost of the education was shifted to the education consumer, the student.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, we started operating under a new set of questions: What is the cost of a dental education? What is the monetary return on the cost of one’s education? Who (or what entity) should be paying the cost of that education? How much can the consumer student invest based on the return on investment (ROI) model?

In order to help students finance their

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 DECEMBER 2022 715 Editor

The idea of 'return on investment' has become the measuring stick and deciding metric for life choices and educational investment.

education, loans were designed to allow parents to take on more debt. These “PLUS loans” have become predatory in the sense that the amount borrowed is not aligned with the family’s income and ability to repay.4 Not only were new graduates mired in debt but families could be ensnared into unrepayable debts to help defray the debt burden on the student. The ROI was the rationale for indebtedness.

The idea of ROI has become the measuring stick and deciding metric for life choices and educational investment. So where did this ROI metric come from?

Frank Donaldson Brown was a brilliant electrical engineer who became an executive at DuPont and General Motors. He was the originator of the DuPont model of analysis. That model has become known as ROI analysis today. It was used to evaluate products, decide on new product investment and set the price for car models. It is now used in many environments as a basis for decisions. In dentistry, it is not only used when pitching the purchase of expensive equipment to dentists (“Your ROI on this $150,000 piece of equipment is less than 15 months. You would be foolish not to finance the purchase.”), but also as the basis for life decisions, like going to dental school.

In 2022, eight pieces of legislation that target dental school debt are being considered in Congress. All except one have to do with calculating or accumulating interest. Dental education cost reform is not addressed.

It made me think of my favorite quote from Thomas Pynchon, the author of “Gravity’s Rainbow:” “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.”

It feels like we keep asking the wrong questions when it comes to student debt. Instead of asking how can we make

borrowing easier? How can we make huge debts repayable over a lifetime? How can we provide more money in the form of loans to students and their families?

Why aren’t we asking:

■ How can we reduce the cost of education for the dental student?

■ How can we remove the financial restrictions on where and how new dentists practice?

■ How can we shift more financial support to the schools that provide dental education and thereby shift the education costs off the backs of students?

■ How can we provide more service commitment opportunities to allow all students who want to defray the cost of their education the chance to contract for their postgraduate service within areas or populations in need?

■ How can we remove the specter of decades of debt that discourage underrepresented categories of dental school applicants?

■ How do we keep from ensnaring the parents of students into committing to impossible-to-repay debt burdens?

■ Are we misappropriating Donaldson Brown’s ROI metric?

■ Exactly what is being invested and what are the returns?

Student debt is a complicated issue, but surely it deserves our utmost effort to ask the right questions. ■

REFERENCES

1. Lieber R. Why Aren’t Student Loans Simple? Because This Is America. The New York Times Sept. 3, 2022.

2. American Dental Education Association. Educational debt

3. Hanson M. Average Dental School Debt. EducationData.org Oct. 11, 2021.

4. Lieber R. The Subprime Loans for College Hiding in Plain Sight The New York Times Sept. 17, 2022.

The Journal welcomes letters

We reserve the right to edit all communications. Letters should discuss an item published in the Journal within the last two months or matters of general interest to our readership. Letters must be no more than 500 words and cite no more than five references. No illustrations will be accepted. Letters should be submitted at editorialmanager.com/ jcaldentassoc. By sending the letter, the author certifies that neither the letter nor one with substantially similar content under the writer’s authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere, and the author acknowledges and agrees that the letter and all rights with regard to the letter become the property of CDA.

716 DECEMBER 2022 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12

DEC. 2022 EDITOR

Reviewers

Thank You to the 2022 Reviewers

The Journal of the California Dental Association is grateful for the many professionals who formally reviewed manuscripts in 2022 and offered their recommendations. We extend our thanks to those who are instrumental in helping us produce this award-winning scientific publication.

Maha Ahmad, PhD

Tamer Alpagot, DDS, PhD

Pamela Arbuckle Alston, DDS, MPP

Baharak Amanzadeh, DDS, MPH

Clarisa Amarillas Gastelum, DDS, MS

Craig W. Amundson, DDS

Homayon Asadi, DDS

Phimon Atsawasuwan, DDS, MSc, MSc, MS, PhD

David M. Avenetti, DDS, MPH, MSD

Leif K. Bakland, DDS

Sepideh Banava, DDS, MSc, MBA, MPH, DABDPH

Nicole Barkhordar, DDS, MEd

Steven Bender, DDS

Beatriz Bezerra, DDS, PhD

Patrick Blahut, DDS, MPH

John L. Blake, DDS

Robert L. Boyd, DDS

Donald L. Branam, BS, PharmD

Carolyn Brown, DDS

Michael E. Cadra, DMD, MD

Paulo Camargo, DDS, MS, MBA

Tom Campbell, DDS

Hsun-Liang Chan, DDS, MS

Hubert Chan, DDS

Jennifer Chang, DDS, MSD

Kai Chiao Joe Chang, DDS, MS

Daniel Chavarria, DDS, PhD

Yo-wei Chen, DDS, MSc

Russell Christensen, DDS

Paul K. Chu, DDS

Stephen Cohen, DDS

Fadie T. Coleman, PhD

James J. Crall, DDS, ScD

Gerald E. Davis, DDS, MA, MS

Nancy Dewhirst, RDH

Evelyn Donate-Bartfield, PhD

Bruce Donoff, DMD, MD

Gary L. Dougan, DDS, MPH

Chad Edwards, DDS

Alec Eidelman, DMD, MPH

Jared Ira Fine, DDS ,MPH

Dana Fischer, MPH, CHES

Jason Flores, DDS, MHA, BSN-RN

David F. Fray, DDS, MBA

Steven Friedrichsen, DDS

Lawrence Gettleman, DMD, MSD

Alan H. Gluskin, DDS

Jay Golinveaux, DDS, MS

Anupama Grandhi, DDS

Richard J. Gray, DDS

Rishi Jay Gupta, DDS, MD, MBA

Mina Habibian, DMD, MS, PhD

Colin Haley, DDS, MEd

Yusuke Hamada, DDS, MSD

Lisa Anne Harpenau, DDS, MS, MBA, MA

Bradley Henson, DDS, PhD

Edmond Hewlett, DDS

Nicole Holland, DDS, MS

Katrina Holt, MPH, MS, RD

Nicola P.T. Innes, PhD, BDS, BSc, BMSc

Lisa Itaya, DDS

Parvati Iyer, DDS

Douglass Jackson, DMD, MS, PhD

Poonam Jain, BDS, MS, MPH

David E. Jaramillo, DDS

Dwight Jennings, DDS

Judith Ann Jones, DDS, MPH, DScD

Cristin E. Kearns, DDS, MBA

Reuben Kim, DDS, PhD

Gary D. Klasser, DMD

Jens Kreth, PhD

Max Kubitz, DDS Jayanth Kumar, DDS, MPH Satish Kumar, DMD, MDSc, MS Wey-Wey Kwok, JD Huong Le, DDS

Irving Lebovics, DDS Alexander Lee, DMD

Felix Lee, DMD

Stuart E. Lieblich, DMD Oariona Lowe, DDS

Cindy Lyon, RDH, DDS, EdD

Mark D. Macek, DDS, DrPH

Ilay Maden, BDS, MSc, PhD

Taraneh Maghsoodi, DDS, MS

Kristen Marchi, MPH

Malay Mathur, DDS

Melanie E. Mayberry, DDS, MS

Keith A. Mays, DDS, MS, PhD

Kevin McNeil, DDS

Diana Messadi, DDS, MMSc, DMSc

Peter Milgrom, DDS

Shelley Miyasaki, DDS, PhD

Mauricio Montero-Aguilar, DDS, MSc

Jean Moore, DrPH, MSN

Richard P. Mungo, DDS, MSD, MeD

Carol Anne Murdoch-Kinch, DDS, PhD

Theodore A. Murray Jr., DDS

Asma Muzaffar, DDS, MS, MPH

Richard J. Nagy, DDS

Mahvash Navazesh, DMD

Man Wai Ng, DDS, MPH

Carol Niforatos, DDS

Nooshin Noghreian, DDS

Enihomo Obadan-Udoh, DDS, MPH, DrMedSc

Heesoo Oh, DDS

David Ojeda, DDS

Joan Otomo-Corgel, DDS, MPH

Mariela Padilla, DDS, MEd

Robert J. Palmer Jr., PhD

Seena Patel, DMD, MPH

Kimberlie Payne, RDH, BA

Shakalpi Pendurkar, DDS, MPH

Steven Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL

Patricia Podolak, DDS, MPH

Howard F. Pollick, BDS, MPH

Kiddee Poomprakobsri, DDS, MSD, MBA

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 DECEMBER 2022 717

CONTINUED ON PAGE 718

Lori Rainchuso, DHSc, MS, RDH

Karen Raju, BDS, MPH

Diana E. Ramos, MD, MPH, MBA

Rajesh Raveendranathan, BDS,

Lindsay Rosenfeld, ScD, ScM

David Lawrence Rothman, DDS

Danielle Rulli, RDH, MS, DHSC

Mark Ryder, DMD

Elise Sarvas, DDS, MSD, MPH

Carlos S. Smith, DDS, MDiv

Hugo Sousa Dias, DDS

Leah Stein Duker, PhD

Charles Stewart, DMD

Piedad Suárez Durall, DDS

Tamanna Tiwari, MPH, MDS, BDS

Richard D. Trushkowsky, DDS

Philip Vassilopoulos, DDS, DMD

Timothy F. Walker, BS, MS, DDS

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 CONTINUED FROM PAGE 717 DEC. 2022 REVIEWERS

*Take 15% off Premium and 5% off Basic Job Post or Resume Search. Scan QR code to apply savings. Offer expires 12/31/22 Trouble Hiring? We can help. Find more dental professionals with the #1 dental job board. SAVE 15% * Redeem Offer

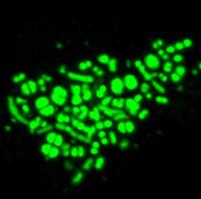

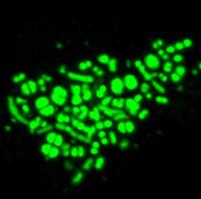

Microbes Form Superorganisms That Spread on Teeth

A cross-kingdom partnership between bacteria and fungi can result in the two joining to form a “superorganism” with unusual strength and resilience. These microbial groupings, found in the saliva of toddlers with severe childhood tooth decay, can effectively colonize teeth, according to a study by University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine scientists. The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research team discovered the assemblages were stickier, more resistant to antimicrobials and more difficult to remove from teeth than either the bacteria or the fungi alone. What’s more, the assemblages unexpectedly sprout “limbs” that propel them to “walk” and “leap” to quickly spread on the tooth surface, despite each microbe on its own being nonmotile.

“This started with a very simple, almost accidental discovery, while looking at saliva samples from toddlers who develop aggressive tooth decay,” said Hyun (Michel) Koo, DDS, MS, PhD, a professor at Penn Dental Medicine and co-corresponding author of the paper.

In the past, Dr. Koo’s lab has focused on the dental biofilm present in children with severe tooth decay, discovering that both bacteria – Streptococcus mutans – and fungi – Candida albicans – contribute to the disease. The discoveries came about when Zhi Ren, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow, was using microscopy that allows scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time.

After seeing the bacterial-fungal clusters present in the saliva samples, the researchers were curious how the groupings might behave once attached to the surface of a tooth. They created a laboratory system to recreate the formation of these assemblages, using the bacteria, fungi and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva. The platform enabled the researchers to watch the groupings come together and to analyze the structure of the resulting assemblages. The team found a highly organized structure with bacterial clusters attached in a complex network of fungal yeast and filament-like projections called hyphae, all enmeshed in an extracellular polymer, a glue-like material.

Next, the researchers tested the properties of the assemblages once they had colonized the tooth surface and found surprising behaviors and emergent properties, including enhanced surface adhesion, making them very sticky, and increased mechanical and antimicrobial tolerance, making them tough to remove or kill.

Although the exact mechanisms are unknown, the assemblages’ ability to “move as they grow” enables them to quickly colonize and spread to new surfaces. When the research team allowed the assemblages to attach to and grow on real human teeth in a laboratory model, they found more extensive tooth decay as a result of a rapidly spreading biofilm.

Because these assemblages are found in saliva, targeting them early on could be a therapeutic strategy to prevent childhood tooth decay, said Dr. Koo. ■

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 DECEMBER 2022 719 Impressions

Study Finds No Adverse Effects of Early Fluoride Exposure on Childhood Development

An Australian nationwide, populationbased, follow-up study published in the Journal of Dental Research has provided evidence that exposure to fluoridated water by young children was not negatively associated with child emotional, behavioral development and executive functioning in their adolescent years.

The study by Prof. Loc Do, PhD, of the University of Queensland Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences, School of Dentistry and colleagues examined the effect of early childhood exposures to water fluoridation on measures of schoolage executive functioning and emotional and behavioral development in a population-based sample. This longitudinal follow-up study used information from Australia’s National Child Oral Health Study of 2012-14. Children aged 5-10 years at the baseline were contacted again after seven to eight years, before they had turned 18.

Percent lifetime exposed to fluoridated water (% LEFW) from birth to the age of 5 years was estimated from residential history and postcode-level fluoride levels in public tap water. Measures of children’s emotional and behavioral development were assessed by the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), and executive functioning was measured by the Behavior Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF). Multivariable regression models were generated to

Genetic Defects Lead to Enamel Malformations

A team of researchers from the Center of Dental Medicine at the University of Zurich has identified a key gene network that is responsible for severe tooth enamel defects. The study was published in the journal iScience

Using various genetically modified mouse models, the scientists analyzed the effects of the Adam10 molecule, which is closely linked to the Notch signaling pathway. This signaling pathway enables communication between adjacent cells, is essential for embryonic development and plays a crucial role in the development of severe human pathologies such as stroke and cancer. To study the role of the Adam10/Notch signaling in the formation and pathology of tooth enamel in detail and to analyze cellular and enamel structure modifications in teeth upon gene mutation, the researchers used state-of-the-art genetic, molecular and imaging tools.

The scientists were able to demonstrate that a close link between impaired Adam10/ Notch function and enamel defects. “Mice carrying mutations of Adam10 have teeth with severe enamel defects,” said Thimios Mitsiadis, DDS, PhD, professor of oral biology at the Center of Dental Medicine and leader of this study. “Adam10 deletion causes disorganization of the ameloblasts, which then leads to severe defects in both the structure and mineral composition of the enamel.” Adam10-dependent Notch signaling is thus not only involved in severe pathological conditions, but also in the organization and structure of the developing tissues, such as teeth.

Understanding the genetic code that controls tooth development, the knowledge of the molecular connections during enamel formation and the impact of mutations leading to enamel malformations opens new horizons in the field of prevention and treatment, said Dr. Mitsiadis. “The requirements for enamel repair and de novo formation are extremely complex, but new genetic and pharmaceutical tools targeting impaired tooth enamel formation will enable us to considerably improve dental care in the future.”

compare the associations between the exposure and the primary outcomes, controlled for covariates. An equivalence test was also conducted to compare the primary outcomes of those who had 100% LEFW against those with 0% LEFW. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted. A total of 2,682 children completed SDQ and BRIEF, with mean scores of 7.0 (95% CI: 6.6, 7.4) and 45.3 (44.7, 45.8), respectively. Those with lower % LEFW tended to have poorer scores on the SDQ

and BRIEF. Multivariable regression models reported no association between exposure to fluoridated water and the SDQ and BRIEF scores. Low household income, identifying as Indigenous and having a neurodevelopmental diagnosis were associated with poorer SDQ/BRIEF scores.

The study concluded that exposure to fluoridated water during the first five years of life was not associated with altered measures of child emotional and behavioral development and executive functioning.

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 720 DECEMBER 2022 DEC. 2022 IMPRESSIONS

Gel Treats Gum Disease by Fighting Inflammation

A topical gel that blocks the receptor for a metabolic byproduct called succinate treats gum disease by suppressing inflammation and changing the makeup of bacteria in the mouth, according to a new study led by researchers at NYU College of Dentistry. The research, conducted in mice and using human cells and plaque

Periodontal Care May Lead to Better Outcomes

After Heart Attack

samples, lays the groundwork for a noninvasive treatment for gum disease that people could apply to the gums at home to prevent or treat gum disease. The study was published in the journal Cell Reports.

The researchers started by examining dental plaque samples from humans and blood samples from mice. Using

University of Michigan researchers who studied patients receiving periodontal care, dental cleanings or no dental care during 2016-2018 and who had acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) in 2017 found that patients who had heart attacks and received periodontal maintenance care had the shortest hospital stays and more follow-up visits, while the longest hospital stays were experienced by the no-dental-care group. The study was published in the Journal of the American Dental Association

There was no statistically significant difference between the other groups (active periodontal care and regular care) compared to the no-care group.

“After controlling for several factors, the periodontal care group had higher odds of having post-hospital visits,” said study co-author Romesh Nalliah, DDS, associate dean for patient services at the U-M School of Dentistry.

The research team wanted to examine the association between periodontal care and heart attack hospitalization and follow-up visits in the 30 days after acute care. Using the MarketScan database, they found 2,370 patients who fit the study criteria. Of those, 47% percent received regular or other oral health care, 7% received active periodontal care (root planing and periodontal scaling) and 10% received controlled periodontal care (maintenance). More than 36% did not have oral health care before they were hospitalized after a heart attack.

“Dentistry is often practiced in isolation from overall health care,” Dr. Nalliah said. “Our results add weight to the evidence that medical and dental health are closely interrelated. More studies like ours are showing that it is a mistake to practice medicine without the thoughtful consideration of the patient’s oral health.”

Improved communication between medical and dental teams could help with early intervention to ensure stable periodontal health in patients who have risk factors for heart disease, Dr. Nalliah said.

metabolomic analyses, they found higher succinate levels in people and mice with gum disease compared to those with healthy gums, confirming what previous studies have found.

They also saw that the succinate receptor was expressed in human and mouse gums. To test the connection between the succinate receptor and the components of gum disease, they genetically altered mice to inactivate, or “knock out,” the succinate receptor.

In “knockout” mice with gum disease, the researchers measured lower levels of inflammation in both the gum tissue and blood, as well as less bone loss. They also found different bacteria in their mouths: Mice with gum disease had a greater imbalance of bacteria than did “knockout” mice.

This held true when the researchers administered extra succinate to both types of mice, which worsened gum disease in normal mice; however, “knockout” mice were protected against inflammation, increases in unhealthy bacteria and bone loss.

To see if blocking the succinate receptor could ameliorate gum disease, the researchers developed a gel formulation of a small compound that targets the succinate receptor and prevents it from being activated. In laboratory studies of human gum cells, the compound reduced inflammation and processes that lead to bone loss.

The compound was then applied as a topical gel to the gums of mice with gum disease, which reduced local and systemic inflammation and bone loss in a matter of days.

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 DECEMBER 2022 721

AUTHOR Jared I. Fine, DDS, MPH, is the former director of Dental Public Health for Alameda County. He continues as a dental public health consultant to Alameda County.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Persistence and Commitment: Unparalleled Advocacy in 2022 — A Game Changer for Vulnerable Californians

Jared I. Fine, DDS, MPH

Jared I. Fine, DDS, MPH

The 2021-2022 California budget cycle might get little notice from the casual observer except for the record budget surplus. This surplus fueled significant financial commitment to address the seemingly unending needs of the nation’s most populous state, including battling COVID-19, destructive wildfires, homelessness and housing shortages, inflation, sky-rocking gasoline prices, the multiyear drought and more. Any of these important priorities could have eaten up the state’s additional resources, so it may seem surprising that, under the radar, dentistry achieved some big wins in the state budget, making significant gains and building on previous successes in new and unprecedented ways. This was not just another day at the office. Witnessing the extraordinary legislative successes is cause for celebration for the millions of Californians who will be the beneficiaries. Yes, a sizable budget surplus had a role, but that is far from the whole story. When I was studying the piano as a young adult, my teacher instructed me to repeat any measure in which I struck the wrong note. Striking the wrong note, he

explained, is not the issue. It’s learning the dance between the notes that accounts for a successful melody. When I think about CDA’s amazing successes this year, I think my teacher’s instructions apply. What were those successful notes? And what were the dance steps that achieved such success?

$1.7

Billion for Health Care Workforce, Staff Recruitment and Training

CDA has been advocating tirelessly for targeted investments to improve dental pipeline opportunities and expand apprenticeship programs to address the dental staff shortages being experienced across the state. Expanding and diversifying the health care workforce is in this budget with hundreds of millions invested in a wide range of health care provider scholarships and loan and grant programs for which many dentists and dental team members are eligible to apply. Among other things, funding will support the work of the Health Workforce Education and Training Council, which aims to build a diverse, culturally competent health care workforce as well as multilingual health initiatives to expand scholarship

DECEMBER 2022 723 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 commentary

repayment for multilingual applicants.

CDA is particularly supportive of two new investments:

■ $45 million to develop and expand High Road Training Partnerships for Health and Human Services.

■ $175 million over three years to the Apprenticeship Innovation Program with a focus on nontraditional apprenticeships, including in health care.

The High Road Training Partnerships (HRTP) is a public-private partnership initiative of the California Workforce Development Board to provide training and career ladder opportunities, including in dental assisting. The new budget investment builds on the HRTP funding of $75 million in last year’s budget, and CDA is in the process of applying for some of those funds to expand the association’s own dental assisting pilot program Smile Crew California.

Expanding this training throughout the state would not only help alleviate dental staffing shortages exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, but also create new job opportunities for workers who were displaced.

The Apprenticeship Innovation Program, which provides grants, reimbursements and other types of funding support to programs that train apprentices, is another opportunity for CDA to help address dental workforce shortages. Funds can be used, for example, for course development and classroom instruction. CDA is already working with the Newsom administration to explore opportunities to establish dental apprenticeships. A three-year investment of an additional $60 million in fiscal years 2023-24 and 2025 is part of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s stated goal of creating 500,000 new apprenticeships across the state by 2029.

$50 Million Investment Will Expedite Care for Patients With Special Health Care Needs

Even though California has made progress to increase access to dental care in the Medi-Cal Dental Program, lack of access to care for patients with special health care needs persists as a decades-long crisis. Only a few settings are equipped to provide care for this patient population, and most settings, including dental schools, have exceptionally long wait times. These delays, which have historically been up to a year or more, have been exacerbated

These additional dental care settings will significantly expand access to care for individuals who are otherwise unable to undergo dental procedures in traditional dental offices due to special health care needs or the complexity of the care needed, including people who need special accommodations for issues of mobility, stabilization or deep sedation. According to Allen Wong, DDS, EdD, American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry president and a professor at the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in the department of diagnostic sciences, “The growing attention on inequities in health care brought on by the pandemic has shined a light on dental care, a huge unmet need for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Advocacy is giving a voice to the voiceless, and they need to be heard.

by the pandemic, often requiring families to travel for hours to find a location that can provide just routine care.

The 2022-23 state budget now includes an investment of $50 million to help alleviate the long wait times and the scarcity of settings throughout the state. The $50 million investment advocated by CDA and a coalition of special needs advocates, provider groups and dental schools will fund grants to build a network of new specialty dental clinics or expand existing settings that serve patients with physical, developmental or cognitive disabilities. Successful applicants will receive up to $5 million in grant funding, need to be Medi-Cal providers and agree to serve the special needs population for at least 10 years upon completion of construction.

“This funding will not solve all the problems,” he added, “but will help to lessen some of the barriers to care while we work on improving the knowledge and comfort level of all oral health providers for this population. Advocacy is giving a voice to the voiceless, and they need to be heard. I am thankful that California has listened and is responding.

$10 Million for Grants To Develop Dental Student Clinical Rotations

CDA successfully made a budget ask of a one-time $10 million allocation to create new and enhanced communitybased clinical education rotations for dental students to improve the health of California’s underserved populations. A newly developed consortia of California dental schools will be responsible for creating these rotations with the goals of improving access to quality health care and to foster a health care workforce that is able to address current and emerging needs. Nader Nadershahi, DDS, MBA, EdD, dean and vice provost of the University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School

724 DECEMBER 2022 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 commentary

of Dentistry and member of the consortia noted, “Hygiene students, dental students and residents come to our programs with a purpose to help members of their communities live healthy lives. Thanks to the CDA, we will now have the resources that allow our schools to collaborate and create sustainable rotations that do not put an additional cost burden on students, enabling them to achieve their purpose.”

CDA’s advocacy was spurred on by the findings of the 2018-2028 California Oral Health Plan advisory committee, which indicated “insufficient infrastructure to promote culturally sensitive communitybased oral health programs” was a key reason for the high prevalence of dental caries and untreated caries among California’s third grade children. The committee also recommended increased collaboration between various health care, academic and public health organizations to provide care to underserved Californians. These new, self-sustaining clinical rotations will give trainees real-world experience in various dental practice models, including federally qualified health centers, private offices and mobile dentistry programs, and enhance learning in patient engagement, practice management and team-based care delivery.

Expanded Medi-Cal Benefits and Backfilled Provider Payments

CDA’s successful advocacy efforts were rewarded by substantial improvements in dental benefits, rates and initiatives in the California Medi-Cal Dental Program. These efforts built on advocacy of past years that witnessed the installment of California’s first dental director and passage of the Proposition 56 tobacco tax, which helps fund medical and oral health care programs.

The 2022-23 budget support includes:

■ A caries risk assessment bundle that includes an examination,

nutrition counseling, prophy, topical fluoride application and SDF for children ages 0 to 6 years old.

■ Expanded coverage of the adult crown benefit to include laboratoryprocessed crowns for posterior teeth. Consistent with American Dental Association evidence-based practice, lab-processed crowns provide better protection for molars than prefabricated crowns and help avoid the need for costly root canal therapy later on.

■ Extension of the CalHealthCares

These new, self-sustaining clinical rotations will give trainees real-world experience in various dental practice models.

student loan repayment program indefinitely. This program has already funded 120 dentists and will serve to encourage more dentists to provide care to the Medi-Cal population.

■ Backfilling a $31.7 million deficit in the Dental Transformation Initiative (DTI) for preventive services for children. Dentists who provided preventive services under the DTI in 2021 will receive full incentive payments for services already rendered.

■ Backfilling Proposition 56 revenues that have dropped due to reduced tobacco sales, as intended by the tax. The 2022-2023 budget supports continuation of enhanced provider

reimbursement rates with general fund dollars, a policy that has contributed to a 25% increase in Medi-Cal provider enrollment since the inception of the tax and one CDA strongly supports for the longterm stability of the program.

How Did CDA Arrive at This Momentous Advocacy Success?

To understand how CDA’s advocacy was so profoundly rewarded in 2022 is to reflect on years, actually decades, of persistence and commitment to its mission of serving the success of its members in service to their patients and the public.

CDA’s investment in care for disenfranchised populations and all Californians goes back decades. Here are a few examples:

■ Advocating for the statewide school-based dental disease prevention program.

■ Advocating for statewide community water fluoridation.

■ Incentivizing local geriatric dental care initiatives.

■ Assisting with the development and adoption of bloodborne pathogen standards in California.

■ Supporting the Californiawide First Smiles educational initiative to slow the epidemic of early childhood caries.

■ Adopting a three-phase, sevenyear strategic plan to address the barriers in access to care for one-third of Californians.

■ Advocating for a state dental director.

■ Reinstating adult Medi-Cal dental benefits after their near total elimination in the Great Recession.

■ Providing leadership in the Proposition 56 tobacco tax funding campaign and for its funding for

DECEMBER 2022 725 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12

the State Office of Oral Health and a local oral health plan in every California county.

To address the persistent and complex challenge of barriers in access to care for literally millions of Californians, the CDA House of Delegates adopted resolutions in 2002 and 2008 recognizing and committing to understanding the problem of access. The 2008 House authorized workgroups that diligently researched the issues for two years and, in 2010, proposed evidenced-based recommendations. In 2011, the formulated recommendations were presented to the house. Key recommendations focused on building a statewide dental public health infrastructure including:

■ Hiring a director with dental public health experience.

■ Developing an oral health plan, building on what exists.

■ Working with existing

stakeholders and programs.

■ Seeking federal and private funding.

■ Developing new childhood prevention programs.

The three-phase, seven-year strategic plan to address barriers in access to care that resulted from this work was adopted nearly unanimously by the 2011 CDA House of Delegates. The plan laid the foundation for CDA’s leadership in the successful 2016 Proposition 56 tobacco tax coalition and resulted in unprecedented funding in the 2017-18 state budget for health care in California. This included $140 million for supplemental Medi-Cal provider payments, full restoration of Medi-Cal adult dental benefits and $30 million of protected, firsttime funding annually for the State Office of Oral Health and local oral health programs.

This recent history has unmistakably demonstrated the importance of long-term engagement, proactive leadership, building

relations for coalitions with those of shared goals and ultimately sustained commitment. And though there is still much work to do to maximize these opportunities, now is a perfect time to pause and celebrate.

CDA’s advocacy would not have hit all the right notes if not for years of dedication to mastering the pathways. The CDA plan to address barriers in access to care states that “ … it was conceived in the context of an association whose members are part of a healing profession and bound by a public covenant and as a collective association tasked with advancing the oral health of the public as well as the profession of dentistry.” The successful CDA advocacy we have witnessed in 2022 is nothing less than historic testimony to the highest ideals of our profession. ■

THE AUTHOR, Jared I. Fine, DDS, MPH, can be reached at jaredfine@comcast.net.

726 DECEMBER 2022 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12

commentary

C.E. Credit

Cryotherapy in Endodontics: A Critical Review

Zahed Mohammadi, DDS, MSc; Sousan Shalavi, DDS; and Hamid Jafarzadeh, DDS, MSc

abstract

In medicine, cryotherapy is used to destroy tissue of both benign and malignant lesions by the freezing and rethawing process. In dentistry, cold application has been frequently employed for postoperative pain control following intraoral surgical procedures. The purpose of this paper is to review the applications of cryotherapy in endodontics including its effects on post-endodontic pain, effectiveness against endodontic infections, hazardous effects on dentin and efficacy on cutting efficiency of Ni-Ti rotary instruments, etc.

Keywords: Root canal therapy, Enterococcus faecalis, cryotherapy, endodontic pain, successful local anesthesia, fracture resistance, dentin, root surface temperature

Zahed Mohammadi, DDS, MSc, is an adjunct distinguished clinical professor at the Iranian Center for Endodontic Research (ICER), Research Institute of Dental Sciences at the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran.

Sousan Shalavi, DDS, is an endodontic researcher in Hamedan, Iran.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported for all authors.

The term cryotherapy is derived from the Greek word cryos, meaning “cold.” Although it refers to the local or general use of low temperatures in medical therapy, cryotherapy actually does not imply implementing cold but rather extracting heat. The magnitude of the change in temperature and biophysical alterations in the tissues depends upon the differences in the temperature of the object and the heat or cold application, exposure time, thermal conductivity of the tissues and type of heat or cold agents employed. The clinical implication of this type of therapy in human tissues causes changes in the host’s local temperature.1,2

Mechanism of Action of Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is the use of extreme cold to freeze and remove abnormal

tissue. It works by reducing the blood flow to a particular area, which can significantly decrease the inflammation degree and swelling that causes pain, especially around a tendon or a joint. It can temporarily reduce the activity of sensory nerve fibers that can also relieve the pain. When the body is vulnerable to extreme cooling, the blood vessels are narrowed and flow less to swelling areas.3–5 Once outside the cryogenic chamber, the vessels expand and an increased presence of Interleukin-10 is established in the blood. The cryotherapy chamber involves exposing individuals to freezing dry air (below −100 C) for two to four minutes.4,6

The intense cold used in cryotherapy can be produced using different substances such as liquid nitrogen, liquid nitrous oxide and argon gas. During cryotherapy, liquid nitrogen

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 DECEMBER 2022 727 cryotherapy

AUTHORS

Hamid Jafarzadeh, DDS, MSc, is on the faculty of dentistry at the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and the Dental Research Center at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences in Mashhad, Iran.

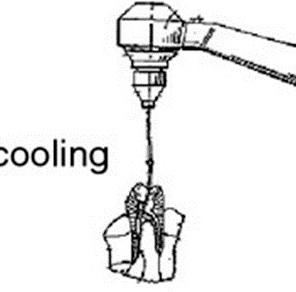

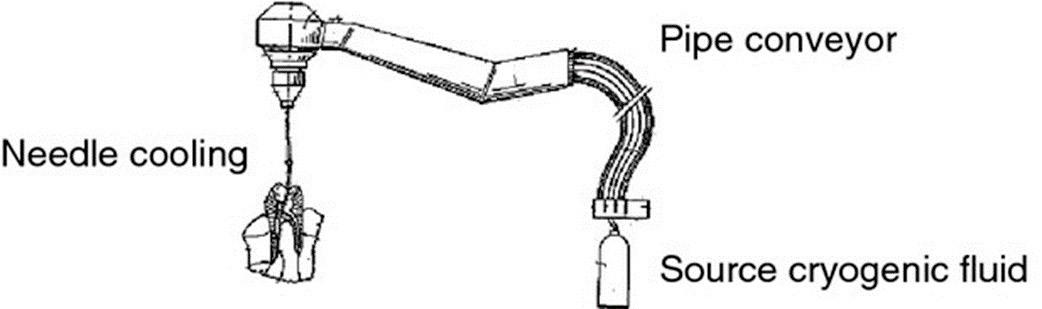

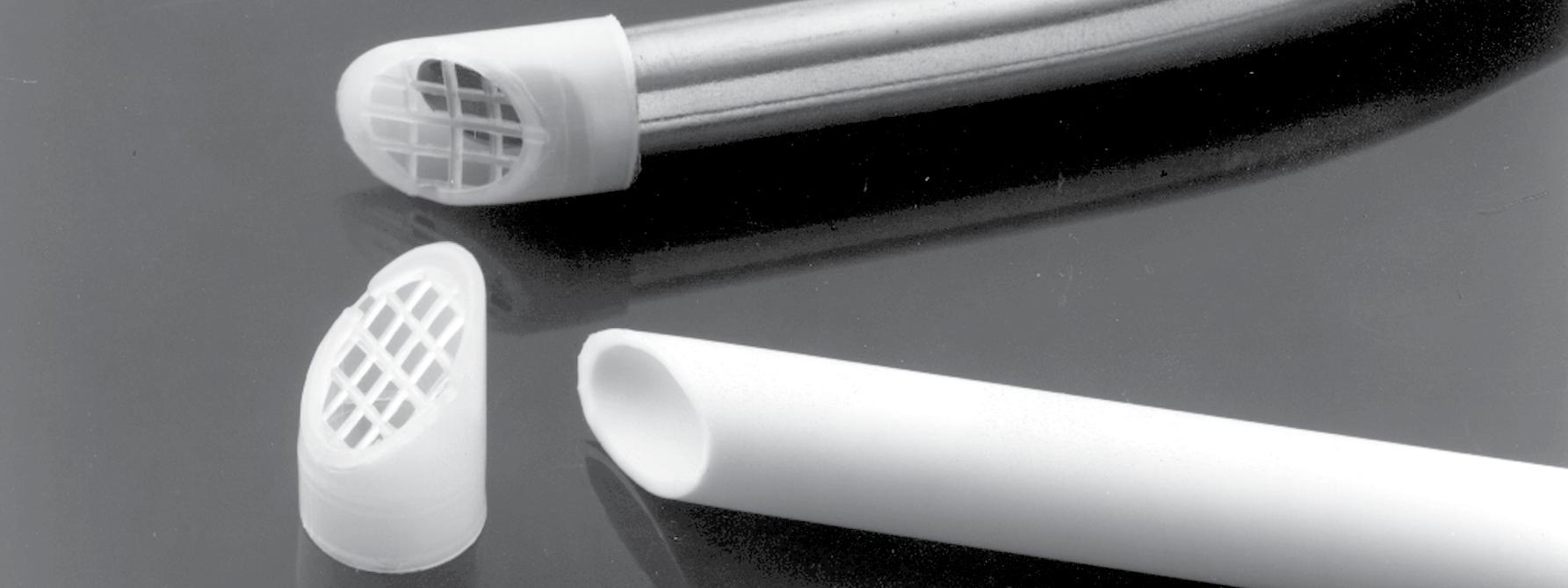

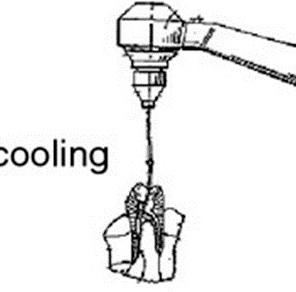

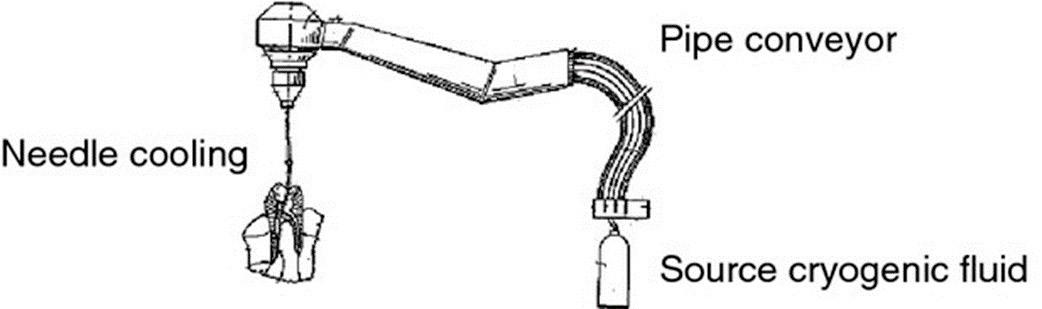

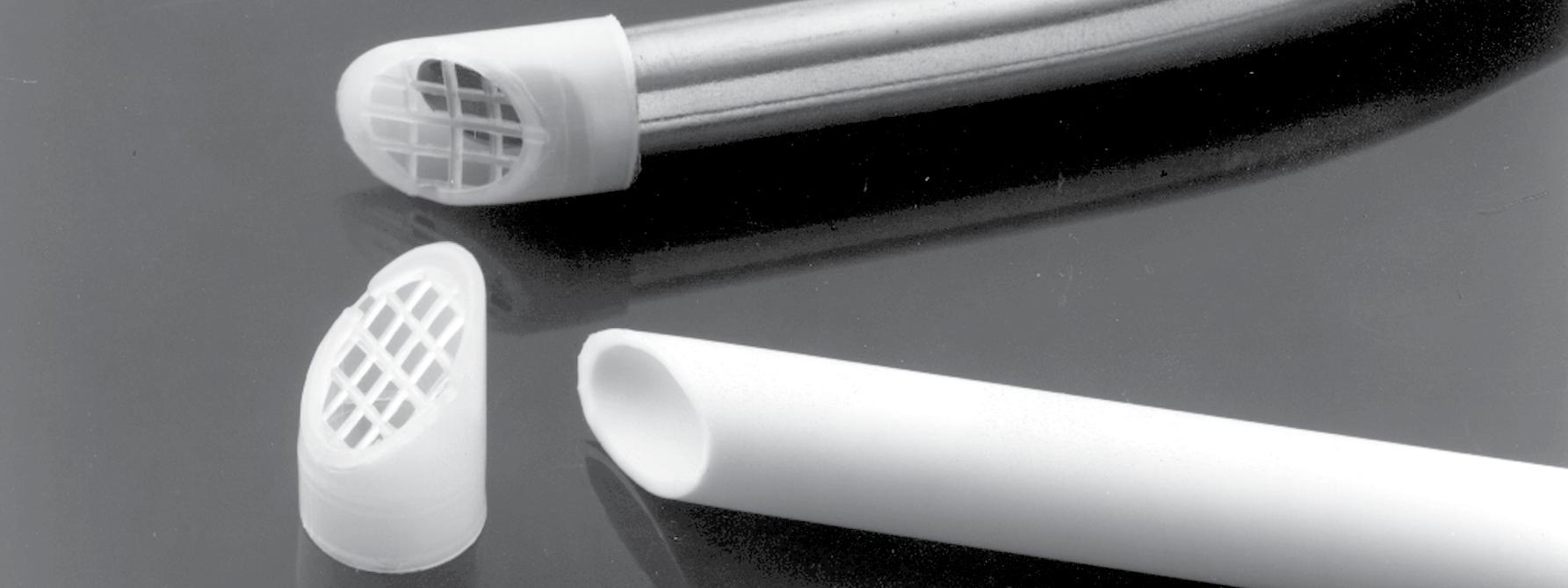

FIGURE. A dental instrument for treating teeth, provided with a needle cryogenic cooling, which receives the fluid from the refrigeration pipe conveyor. (Drawing courtesy of Giuliana Banche, PhD.)23

TABLE 1

Effect of Cryotherapy on Postoperative Pain

Authors

Vera et al.

Keskin et al.

Alharthi et al.

Gundogdu and Arslan

Nandakumar and Nasim

Al-Nahlawi et al.

Sadaf et al.

Monteiro et al.

or high-pressure argon gas flows into a needle-like applicator or cryoprobe.6

Cryotherapy in Medicine and Dentistry

In medicine, cryotherapy, sometimes referred to as cryosurgery, is a procedure used to destroy tissue of both benign and malignant lesions by the freezing and rethawing process. Examples of the uses of cryotherapy in medicine are the removal of various types of skin lesions, the treatment of dysplastic tissue of the uterine cervix and the treatment of some prostate cancers. Cryotherapy can also refer to the use of ice or cold packs applied to a part of the body after an injury to reduce inflammation.7

In dentistry, cold application has been frequently employed for postoperative pain control following intraoral surgical procedures.8 Although the mechanism of action and effectiveness of cryotherapy are well addressed in the literature, strong evidence to support its conclusions is lacking, except for the

Type of study

Randomized multicenter clinical trial

Effect on postoperative pain Year

Reduced the incidence of pain 2018

Reduced pain 2017 Clinical trial

Randomized controlled trial

Randomized prospective clinical trial

Randomized controlled clinical trial

Effect was not significant 2019

Reduced pain 2018

Reduced pain 2020

Reduced pain 2016 Clinical trial

Systematic review

Systematic review

Reduced pain at six and 24 hours after the procedure 2020

Reduced pain after six and 24 hours 2021

standardization of crucial factors such as the time period, duration, application mode and cold agent used. However, in recent years, a few studies were attempted and reported the intracanal use of cryotherapy in endodontics to reduce post-endodontic pain.9–12

Method Used To Apply Cryotherapy in the Root Canal

The dental instrument used for cryotherapy is equipped with a conduit of a conveyor capable of being connected to a source of fluid and a needle cryogenic cooling, which receives the fluid from the refrigeration pipe conveyor. The needle is made of a flexible material and has a smaller outer diameter (0.25 mm) than the size of the entrance inside a tooth canal so that it can be inserted into the canal tooth itself, where the cryogenic fluid is blown (FIGURE)

Cryotherapy in Endodontics Effect on Post-Endodontic Pain

In a randomized, multicenter clinical trial, Vera et al.12 showed that cryotherapy reduced the incidence of postoperative pain and the need for medication in patients presenting with a diagnosis of necrotic pulp and symptomatic apical periodontitis.

Keskin et al.11 revealed a significant reduction in postoperative pain in the cryotherapy group compared with the control group. Teeth with vital inflamed pulp were included in their study; however, they did not differentiate between asymptomatic and symptomatic pulpitis nor did they differentiate between cases with and without apical periodontitis.

In a randomized controlled trial, Alharthi et al.13 found that the roomtemperature saline as final irrigation showed comparable results to intracanal cryotherapy in previously asymptomatic cases without periapical pathosis.

CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 728 DECEMBER 2022 cryotherapy

Studies on Cryogenic Treatment of Ni-Ti Rotary Instruments Results Year Authors

2005 Kim et al.

Cryogenically treated specimens had a significantly higher microhardness than the controls.

2007 Vinothkumar et al.

Deep-dry cryogenic treatment increased the cutting efficiency of Ni-Ti instruments significantly.

2011 George et al.

A randomized prospective clinical trial showed that all the cryotherapy applications (intracanal, intraoral and extraoral) resulted in lower postoperative pain levels and lower visual analogue scale (VAS) scores of pain on percussion versus those of the control group.14 Another clinical trial compared the effect of intracanal cryotreated sodium hypochlorite and room-temperature sodium hypochlorite on postoperative pain after root canal treatment. Results demonstrated that the cryotherapy group showed a statistically significant reduction in postoperative pain levels at all tested time intervals and reduced analgesic intake at six hours postoperatively.15 In another study, Al-Nahlawi et al.6 indicated that the use of intracanal cryotherapy technique with negative pressure irrigation eliminates post-endodontic pain after single-visit root canal treatment (RCT).

In a systematic review, Sadaf et al.16 evaluated the effect of intracanal cryotherapy on postoperative pain after root canal therapy in patients with pulpal or periradicular pathosis. Findings showed that, compared with controls, intracanal cryotherapy significantly reduced postoperative pain at six and 24 hours after the procedure. However, there was no significant effect on pain at 48 and 72 hours and seven days after the procedure. In a recent systematic review, Monteiro et al.17 showed that intracanal cryotherapy application reduced postoperative endodontic pain after six and 24 hours (TABLE 1 ).

Deep cryogenic treatment improved the cyclic fatigue resistance of Ni-Ti rotary files significantly.

Effect on the Success of Local Anesthesia

Despite the fact that inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) is the standardized injection technique used for achieving regional anesthesia for mandibular molar teeth, it does not always result in successful pulpal anesthesia, especially in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (SIP).18 Preoperative intraoral cryotherapy application after an IANB did not provide profound pulpal anesthesia for about 45% of mandibular molars with SIP. However, intraoral cryotherapy might be preferred as a simple and cheap auxiliary application to increase the success rate of IANBs in patients with SIP.19

Effect on Fracture Resistance of Endodontically Treated Teeth

Keskin et al.20 evaluated the effect of intracanal cryotherapy on the fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth. Findings showed that application of intracanal cryotherapy as a final irrigant reduced the vertical fracture resistance of prepared roots when compared to the control group.

Effect on Reducing Root Surface Temperature

Vera et al.21 assessed a new methodology to reduce and maintain external root surface temperature for at least four minutes. Findings showed that although significant differences were found between the initial and lowest temperatures in both the control and experimental irrigation procedures, the experimental intervention reduced it almost 10 times that of the control.

When maintaining a −10 C temperature reduction over four minutes, the teeth in the experimental group also sustained significantly better results.

Effect on Enterococcus faecalis

Enterococcus faecalis is the species most often implicated in persistent root canal infections because of its several virulence factors that make it difficult to eradicate from the canals.22

Mandras et al.23 indicated that cryo-instrumentation after NaOCl irrigation significantly reduced the number of bacteria in the root canal compared to NaOCl alone, without the total elimination of Enterococcus faecalis. The cryogenic fluid (liquid nitrogen), by suitably varying the duration of the treatment, can reach the desired depth and provide immediate freezing of bacterial cells and their subsequent cryodestruction.

The process of freezing and thawing induces injury in microorganisms, in part, through membrane or cell wall disruption, leakage of intracellular constituents and changes in protein conformation.24 Yamamoto and Harris20 showed that in a test executed applying the freezing and thawing technique (30 s ‘ON’, 30 s ‘OFF’ and 30 s ‘ON’) using liquid nitrogen, the bacteria in vitro are significantly reduced with respect to the situation before the treatment.

Effect on Cutting Efficacy of Ni-Ti Rotary Instruments

Historically, the cold treatment of metals during manufacture had been advocated as a means of improving the surface hardness and thermal stability of the metal.25 The optimum cold treatment temperature range lies between −60 C and −80 C for tool steels depending upon the material and on the quenching parameters involved.25 For the past

DECEMBER 2022 729 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12

TABLE

2

30 years, researchers have reported substantial benefits from subjecting metals for industrial applications to a cryogenic process.25–27 Cryogenic treatment involves submersing metal in a super-cooled bath containing liquid nitrogen (−196 C/ −320 F)25,26 and then allowing the metal to slowly warm to room temperature. This cryogenic treatment is used to treat a wide range of metal components, including high-speed steel and hot-work tool steel.27,28 The cryogenic treatment was shown to have more beneficial effects than the traditional higher temperature cold treatment.29 The benefits include increasing cutting efficiency as well as the overall strength of the metal.25,27 Cryogenic treatment is an inexpensive treatment that affects the entire crosssection of the metal rather than just the surface in contrast to surface treatment techniques,26 such as ion implantation and vapor deposition. Currently, two mechanisms are believed to account for the change in the properties from cryogenic treatment for steel. The first is a more complete martensite transformation from the austenite phase following cryogenic treatment.28 The second is the precipitation of finer carbide particles within the crystalline structure.27 Controversy exists as to which mechanism is responsible.

There are few studies on the cryogenic treatment of Ni-Ti rotary files. Kim et al.30 evaluated the effects of cryogenic treatment on the composition, microhardness or cutting efficiency of Ni-Ti rotary instruments. According to their findings cryogenically treated specimens had a significantly higher microhardness than the controls. Furthermore, both cryogenically treated and control specimens were composed of 56% Ni, 44% Ti, 0% N (by weight) with a majority in the austenite phase. In another study, Vinothkumar et al.31 showed that deep

dry cryogenic treatment increased the cutting efficiency of Ni-Ti instruments significantly but not the wear resistance. George et al.32 found that deep cryogenic treatment improved the cyclic fatigue resistance of Ni-Ti rotary files significantly (TABLE 2 ).

Conclusion

In endodontics, cold has been used for multiple purposes including controlling postoperative endodontic pain, increasing the success rate of local anesthesia, enhancing the fracture resistance of the endodontically treated teeth, decreasing the temperature of the root surface, acting against specific bacteria like Enterococcus faecalis and enhancing the cutting efficiency of Ni-Ti rotary instruments. ■

REFERENCES

1. Chanliongo PM. Cold (cryo) therapy. In: Lennard TA, Walkowski S, Singla AK, Vivian DG, eds. Pain procedures in clinical practice. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011:555–558.

2. Newman R, Clebak KT, Croad J, Wile K, Cathcart E. Assorted skin procedures: Foreign body removal, cryotherapy, electrosurgery and treatment of keloids. Prim Care 2022 Mar;49(1):47–62 doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2021.10.003. Epub 2022 Jan 5.

3. Lombardi G, Ziemann E, Banfi G. Whole-body cryotherapy in athletes: From therapy to stimulation. An updated review of the literature. Front Physiol 2017 May 2;8:258 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00258. eCollection 2017. PMCID: PMC5411446

4. Klimenko T, Ahvenainen S, Karvonen SL. Whole-body cryotherapy in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 2008 Jun;144(6):806–8 doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.6.806

5. Swenson C, Swärd L, Karlsson J. Cryotherapy in sports medicine. Scand J Med Sci Sport 1996 Aug;6(4):193–200 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00090.x

6. Luethy D. Cryotherapy techniques: Best protocols to support the foot in health and disease. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 2021 Dec;37(3):685–693 doi: 10.1016/j. cveq.2021.07.005

7. Bouzigon R, Grappe F, Ravier G, Dugue B. Whole- and partial-body cryostimulation/cryotherapy: Current technologies and practical applications. J Therm Biol 2016 Oct;61:67–81 doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2016.08.009. Epub 2016 Aug 27.

8. Whittaker DK. History of cryosurgery. In: Bradley PF ed. Cryosurgery of the maxillofacial region. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; vol. 1 1986:2–13.

9. Pogrel MA. The use of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy in the management of locally aggressive bone lesions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993 Mar;51(3):269–73; discussion 274 doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80172-7

10. Al-Nahlawi T, Hatab TA, Alrazak MA, Al-Abdullah

A. Effect of intracanal cryotherapy and negative irrigation technique on postendodontic pain. J Contemp Dent Pract 2016 Dec 1;17(12):990–996

11. Keskin C, Özdemir Ö, Uzun İ, Güler B. Effect of intracanal cryotherapy on pain after single-visit root canal treatment. Aust Endod J 2017 Aug;43(2):83–88 doi: 10.1111/aej.12175 Epub 2016 Oct 4.

12. Vera J, Ochoa J, Romero M, et al. Intracanal cryotherapy reduces postoperative pain in teeth with symptomatic apical periodontitis: A randomized multicenter clinical trial. J Endod 2018 Jan;44(1):4–8 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.08.038 Epub 2017 Nov 1.

13. Alharthi AA, Aljoudi MH, Almaliki MN, Almalki MA, Sunbul MA. Effect of intra-canal cryotherapy on postendodontic pain in single-visit RCT: A randomized controlled trial. Saudi Dent J 2019 Jul;31(3):330–335 doi: 10.1016/j. sdentj.2019.03.004. Epub 2019 Mar 14. PMCID: PMC6626252

14. Gundogdu EC, Arslan H. Effects of various cryotherapy applications on postoperative pain in molar teeth with symptomatic apical periodontitis: A preliminary randomized prospective clinical trial. J Endod 2018 Mar;44(3):349–354 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.11.002. Epub 2018 Feb 3.

15. Nandakumar M, Nasim I. Effect of intracanal cryotreated sodium hypochlorite on postoperative pain after root canal treatment - a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Conserv Dent 2020 Mar–Apr;23(2):131–136 doi: 10.4103/JCD. JCD_65_20. Epub 2020 Nov 5. PMCID: PMC7720754

16. Sadaf D, Ahmad MZ, Onakpoya IJ. Effectiveness of intracanal cryotherapy in root canal therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Endod 2020 Dec;46(12):1811–1823.e1 doi: 10.1016/j. joen.2020.08.022. Epub 2020 Sep 8.

17. Monteiro LPB, Guerreiro MYR, de Castro Valino R, Magno MB, Maia LC, da Silva Brandão JM. Effect of intracanal cryotherapy application on postoperative endodontic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2021 Jan;25(1):23–35 doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03693-8. Epub 2020 Nov 21.

18. Mohammadi Z, Chavoshi M. Effect of needle bevel direction on the success rate of intra-ligament injection technique: A single-blinded clinical trial. Int J Clin Dent 2013;6:349–353

19. Topçuoglu HS, Arslan H, Topçuoglu G, Demirbuga S. The effect of cryotherapy application on the success rate of inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. J Endod 2021 Jan;25(1):23–35 doi: 10.1007/ s00784-020-03693-8. Epub 2020 Nov 21.

20. Keskin C, Sariyilmaz E, Keleş A, Güler DH. Effect of intracanal cryotherapy on the fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth. Acta Odontol Scand 2019 Mar;77(2):164–167 doi: 10.1080/00016357.2018.1549748. Epub 2019 Jan 9.

21. Vera J, Ochoa-Rivera J, Vazquez-Carcaño M, Romero M, Arias A, Sleiman P. Effect of intracanal cryotherapy on reducing root surface temperature. J Endod 2015 Nov;41(11):1884–7 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.009. Epub 2015 Oct 1.

22. Mohammadi Z, Dummer PM. Properties and applications of calcium hydroxide in endodontics and dental traumatology. Int Endod J 2011 Aug;44(8):697–730 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01886.x. Epub 2011 May 2.

730 DECEMBER 2022 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 cryotherapy

23. Mandras N, Allizond V, Bianco A, et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of cryotreatment against Enterococcus faecalis in root canals. Lett Appl Microbiol 2013 Feb;56(2):95–8 doi: 10.1111/lam.12017. Epub 2012 Dec 27.

24. Yamamoto SA, Harris LJ. The effects of freezing and thawing on the survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in apple juice. Int J Food Microbiol 2001 Jul 20;67(1–2):89–96 doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00438-x

25. Huang HH, Hsu CH, Pan SJ, He JL, Chen CC, Lee TL. Corrosion and cell adhesion behavior of TiN-coated and ion nitrided titanium for dental applications. Appl Surf Sci 2005;244(1–4):252–256 doi.org/10.1016/j. apsusc.2004.10.144

26. Li UM, Chiang YC, Chang WH, et al. Study of the effects of thermal nitriding surface modification of nickel titanium rotary instruments on the wear resistance and cutting efficiency. J Dent

Sci 2006;1(1):53–58 doi:10.30086/JDS.200606.0001

27. Mohammadi Z, Soltani MK, Shalavi S, Asgary S. A review of the various surface treatments of Ni-Ti instruments. Iran Endod J 2014 Fall;9(4):235–240. Epub 2014 Oct 7. PMCID: PMC4224758

28. Shevchenko N, Pham MT, Maitz M. Studies of surface modified Ni-Ti alloy. Appl Surf Sci 2004;235(1–2):126–131 doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2004.05.273

29. Conrad J, Dodd R, Worzala F, Qiu X. Plasma source ion implantation: A new, cost-effective, non-line-of-sight technique for ion implantation of materials. Surf Coat Technol 1988;36(3-4):927–937 doi.org/10.1016/02578972(88)90033-3

30. Kim JW, Griggs JA, Regan JD, Ellis RA, Cai Z. Effect of cryogenic treatment on nickel-titanium endodontic instruments. Int Endod J 2005 Jun;38(6):364–71 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-

2591.2005.00945.x PMCID: PMC1266290

31. Vinothkumar TS, Miglani R, Lakshminarayananan L. Influence of deep dry cryogenic treatment on cutting efficiency and wear resistance of nickel-titanium rotary endodontic instruments. J Endod 2007 Nov;33(11):1355–8 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.07.017. Epub 2007 Aug 23.

32. George GK, Sanjeev K, Sekar M. An in vitro evaluation of the effect of deep dry cryotreatment on the cutting efficiency of three rotary nickel titanium instruments. J Conserv Dent 2011 Apr;14(2):169–72 doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.82627 PMCID: PMC3146111

THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR, Hamid Jafarzadeh, DDS, MSc, can be reached at hamid_j365@yahoo.com.

DECEMBER 2022 731 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12

• Inexpensive • Disposable • Non-Toxic Package of 100 E-VAC INC.© CALL: (509) 448-2602 EMAIL: kenevac@hotmail.com Made in USA The Original E-VAC Tip PREVENT PAINFUL TISSUE PLUGS PROTECT YOUR EQUIPMENT FROM COSTLY REPAIRS FDA Registered Contact Your Local Dental Supply Company

December 2022 CDA Continuing Education Worksheet

This worksheet provides readers an opportunity to review C.E. questions for the article “Cryotherapy in Endodontics: A Critical Review” before taking the C.E. test online. You must first be registered at cdapresents360.com. To take the test online, click here. This activity counts as 0.5 of Core C.E.

1. True or False: Cryotherapy is the use of extreme cold to freeze and remove abnormal tissue.

2. The magnitude of tissue alteration during cryotherapy depends on all but which one of the following?

a. Thermal conductivity of the tissues.

b. Exposure time.

c. Type of heat or cold agents employed. d. Final temperature of the agent employed.

3. Which of the following describe cryotherapy? (mark all that apply)

a. Cryotherapy chamber exposes individuals to freezing dry air (below –100 C) for two to four minutes.

b. Blood vessels are narrowed by the extreme cooling.

c. Narrowed vessels reduce blood flow, which reduces inflammation and swelling.

d. Once outside the chamber, vessels expand and an increased presence of Interleukin-10 is established in the blood.

e. Sensory nerve fibers are stimulated, which may cause temporary painful sensations during and/or immediately following treatment.

4. Which one of the following substances is not commonly used during medical or dental cryotherapy?

a. Dry ice.

b. Liquid nitrogen.

c. Liquid nitrous oxide. d. Argon gas.

5. Which one of the following statements does not apply to the dental instrument used for cryotherapy?

a. It is equipped with a conduit of a conveyor capable of being connected to a needle and a source of cryogenic fluid.

b. The needle has a smaller outer diameter (0.25 mm) than the size of the entrance inside a tooth canal so that it can be inserted into the canal.

c. The needle is made of a rigid material to keep it from bending or breaking in the canal.

d. The cryogenic fluid is blown into the canal via the needle.

The authors cite the results of several studies that used cryotherapy for endodontic care. Which of the following are true and which are false?

6. True or False: A randomized prospective clinical trial showed that of all the cryotherapy applications (intracanal, intraoral and extraoral), only the intracanal application resulted in lower postoperative pain levels than those of the control group.

7. True or False: A clinical trial comparing the effect of intracanal cryotreated sodium hypochlorite and room-temperature sodium hypochlorite on postoperative pain after root canal treatment failed to demonstrate a difference in pain reduction between the cryotherapy group and the control group.

8. True or False: The authors posit that because inferior alveolar nerve blocks (IANBS) do not always result in successful pulpal anesthesia, especially in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, intraoral cryotherapy might be a useful auxiliary application to increase the success rate of IANBs in these patients.

9. True or False: A study evaluating the effect of intracanal cryotherapy on the fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth showed that application of intracanal cryotherapy as a final irrigant reduced the vertical fracture resistance of prepared roots when compared to the control group.

10. True or False: A study on the effect of cryotherapy on Enterococcus faecalis, the bacterial species most often implicated in persistent root canal infections, indicated that cryo-instrumentation after NaOCl irrigation significantly reduced the number of bacteria in the root canal compared to NaOCl alone.

732 DECEMBER 2022 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12 C.E. CREDIT QUESTIONS

Integrated Approaches to Preventing and Managing Chronic Diseases: Colorado’s

Diabetes Cardiovascular Disease Oral Health Integration Program

Katya Mauritson, DMD, MPH(c); Sara Grassemeyer, MPH; Ian Danielson, MPA; and Abby Laib, MS

abstract

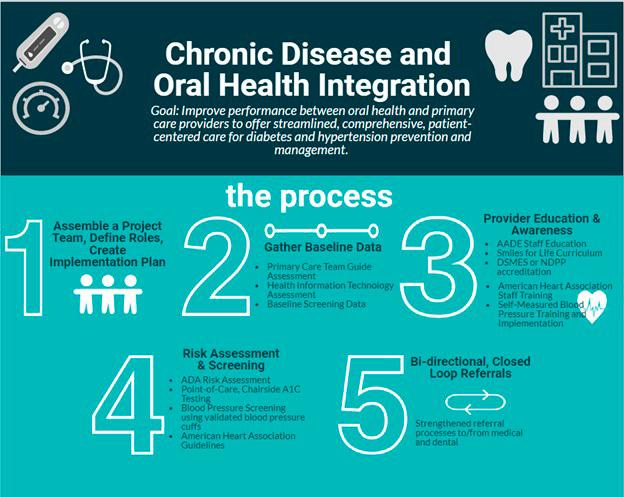

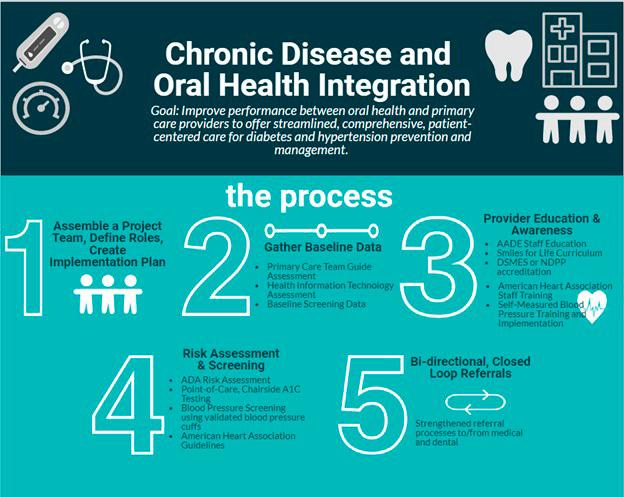

Research indicates that diabetes and hypertension are linked to worsening periodontal disease and uncontrolled oral diseases can make it difficult to prevent or manage other chronic diseases, creating deleterious cycles that can undermine overall health. Colorado continues to test integration strategies to leverage clinical safety net and public health workforces to address the most pressing health care needs of underserved communities, with a focus on preventing and managing (pre)diabetes, (pre)hypertension and oral diseases.

Keywords: Medical-dental integration, oral public health, diabetes, hypertension, oral health, dental, oral health equity, Colorado, Models of Collaboration

DECEMBER 2022 733 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 50 , Nº 12

chronic diseases

AUTHORS

Katya Mauritson, DMD, MPH(c), was Colorado’s state dental director and manager of the oral health unit at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for 10 years. The oral health unit works to decrease oral health inequities across Colorado by integrating oral health strategies into public health and clinical systems across the state.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Sara Grassmeyer, MPH, is the clinical quality improvement program manager for the Health Promotion Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Prevention Services Division in the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for five years. In this role, she promotes effective use of health information technology and clinic quality improvement for oral and chronic disease prevention and management and more.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Ian Danielson, MPA, is a chronic disease evaluator at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. He led several evaluations for programs in the state of Colorado that focused on reducing the prevalence of and inequities in hypertension and diabetes.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Abby Laib, MS, is a program evaluator at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. She has experience planning, implementing and managing public health evaluations as well as working with diverse stakeholders to effectively utilize their data to inform program decisions and improvements.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.