NEW TDIC SEMINAR

Through an engaging, self-guided course, learn how to sharpen your critical communication and documentation skills to lessen potential complaints, claims or lawsuits.

Take all the course modules at once or study them as time allows at your own pace from the comfort of your home or office. Upon course completion, earn 3.0 units ADA CERP C.E. and a 5% Professional Liability premium discount.*

Learn more and register online at tdicinsurance.com/seminars.

The Associate Editor/MultiGen at Work

RM Matters/Facing Reality: Communicating and Managing Achievable Aesthetic Outcomes Regulatory Compliance/How To Manage Patient Information Breach Assessment and Notification

Dental Student Research

An introduction to the issue.

Zohra Tumur, MD, PHD

Management of Hypertensive Crisis in a Dental School: 10-year Retrospective Review of Medical Emergency Incidents With Recommendations

This 10-year retrospective study analyzes the past medical emergency in-house calls at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Soh Yeun Kim, DDS; Sarah Lim, BA; Chanmee Esther Kim, BS; Lauren Barlow, BS; Adlene Chang, BA; Holli Riter, DDS; Iris Nam, DDS; Heidi Christensen, DDS; and Udochukwu Oyoyo, MPH

The objective of this study was to compare the time taken for second-year dental students to collect periodontal data and to assess their confidence level in preclinical activities.

Amelia David, BDS, MS; Soh Yeun Kim, DDS; Barnabas Kim, BS; and Hyan Il Kim, BS; and Udochukwu Oyoyo, MPH

Rollout of the Oral Health Literacy Toolkit in California: A Mixed-Methods Analysis

This study was intended to obtain user feedback and suggestions for improvement of the toolkit.

Christine Y.W. Hao, DMD, MPH; Karen Sokal-Gutierrez, MD, MPH; Susan L. Ivey, MD, MHSA; and Kristin S. Hoeft, PhD, MPH

published by the California Dental Association 1201 K St., 14th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 800.232.7645 cda.org

CDA Officers

Ariane R. Terlet, DDS President president@cda.org

John L. Blake, DDS President-Elect presidentelect@cda.org Carliza Marcos, DDS Vice President vicepresident@cda.org

Max Martinez, DDS Secretary secretary@cda.org

Steven J. Kend, DDS Treasurer treasurer@cda.org

Debra S. Finney, MS, DDS Speaker of the House speaker@cda.org

Judee Tippett-Whyte, DDS Immediate Past President pastpresident@cda.org

CALIFORNIA DENTAL ASSOCIATION

Peter A. DuBois Executive Director

Carrie E. Gordon Chief Strategy Officer

Alicia Malaby Communications Director

Editorial

Kerry K. Carney, DDS, CDE Editor-in-Chief Kerry.Carney@cda.org

Ruchi K. Sahota, DDS, CDE Associate Editor

Marisa Kawata Watanabe, DDS, MS Associate Editor

Gayle Mathe, RDH Senior Editor

Zohra Tumur, MD, PhD Guest Editor

Andrea LaMattina, CDE Publications Manager

Kristi Parker Johnson Communications Manager

Blake Ellington Tech Trends Editor

Jack F. Conley, DDS Editor Emeritus

Robert E. Horseman, DDS Humorist Emeritus

Production

Danielle Foster Production Designer

Upcoming Topics December/General Topics January/Public Health Initiatives February/General Topics

Advertising

Sue Gardner Advertising Sales Sue.Gardner@cda.org 916.554.4952

Volume 50 Number 11 November 2022

Andrea LaMattina, CDE Publications Manager Andrea.LaMattina@cda.org 916.554.5950

www.editorialmanager. com/jcaldentassoc

Letters to the Editor www.editorialmanager. com/jcaldentassoc

Journal of the California Dental Association Editorial Board

Charles N. Bertolami, DDS, DMedSc, Herman Robert Fox dean, NYU College of Dentistry, New York

Steven W. Friedrichsen, DDS, professor and dean emeritus, Western University of Health Sciences College of Dental Medicine, Pomona, Calif.

Mina Habibian, DMD, MSc, PhD, associate professor of clinical dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles

Robert Handysides, DDS, dean and associate professor, department of endodontics, Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, Loma Linda, Calif.

Bradley Henson, DDS, PhD, interim vice president research & biotechnology, associate dean for research and biomedical sciences and associate professor, Western University of Health Sciences College of Dental Medicine, Pomona, Calif.

Paul Krebsbach, DDS, PhD, dean and professor, section of periodontics, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Dentistry

Jayanth Kumar, DDS, MPH, state dental director, Sacramento, Calif.

Lucinda J. Lyon, BSDH, DDS, EdD, associate dean, oral health education, University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, San Francisco

Nader A. Nadershahi, DDS, MBA, EdD, dean, University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, San Francisco

The Journal of the California Dental Association (ISSN 1942-4396) is published monthly by the California Dental Association, 1201 K St., 14th Floor, Sacramento, CA 95814, 916.554.5950. The California Dental Association holds the copyright for all articles and artwork published herein.

The Journal of the California Dental Association is published under the supervision of CDA’s editorial staff. Neither the editorial staff, the editor, nor the association are responsible for any expression of opinion or statement of fact, all of which are published solely on the authority of the author whose name is indicated. The association reserves the right to illustrate, reduce, revise or reject any manuscript submitted. Articles are considered for publication on condition that they are contributed solely to the Journal of the California Dental Association. The association does not assume liability for the content of advertisements, nor do advertisements constitute endorsement or approval of advertised products or services.

Copyright 2022 by the California Dental Association. All rights reserved.

Visit cda.org/journal for the Journal of the California Dental Association’s policies and procedures, author instructions and aims and scope statement.

Connect to the CDA community by following and sharing on social channels

Francisco Ramos-Gomez, DDS, MS, MPH, professor, section of pediatric dentistry and director, UCLA Center for Children’s Oral Health, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Dentistry

Michael Reddy, DMD, DMSc, dean, University of California, San Francisco, School of Dentistry

Avishai Sadan, DMD, dean, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles

Harold Slavkin, DDS, dean and professor emeritus, division of biomedical sciences, Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles

Brian J. Swann, DDS, MPH, chief, oral health services, Cambridge Health Alliance; assistant professor, oral health policy and epidemiology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston

Richard W. Valachovic, DMD, MPH, president emeritus, American Dental Education Association, Washington, D.C.

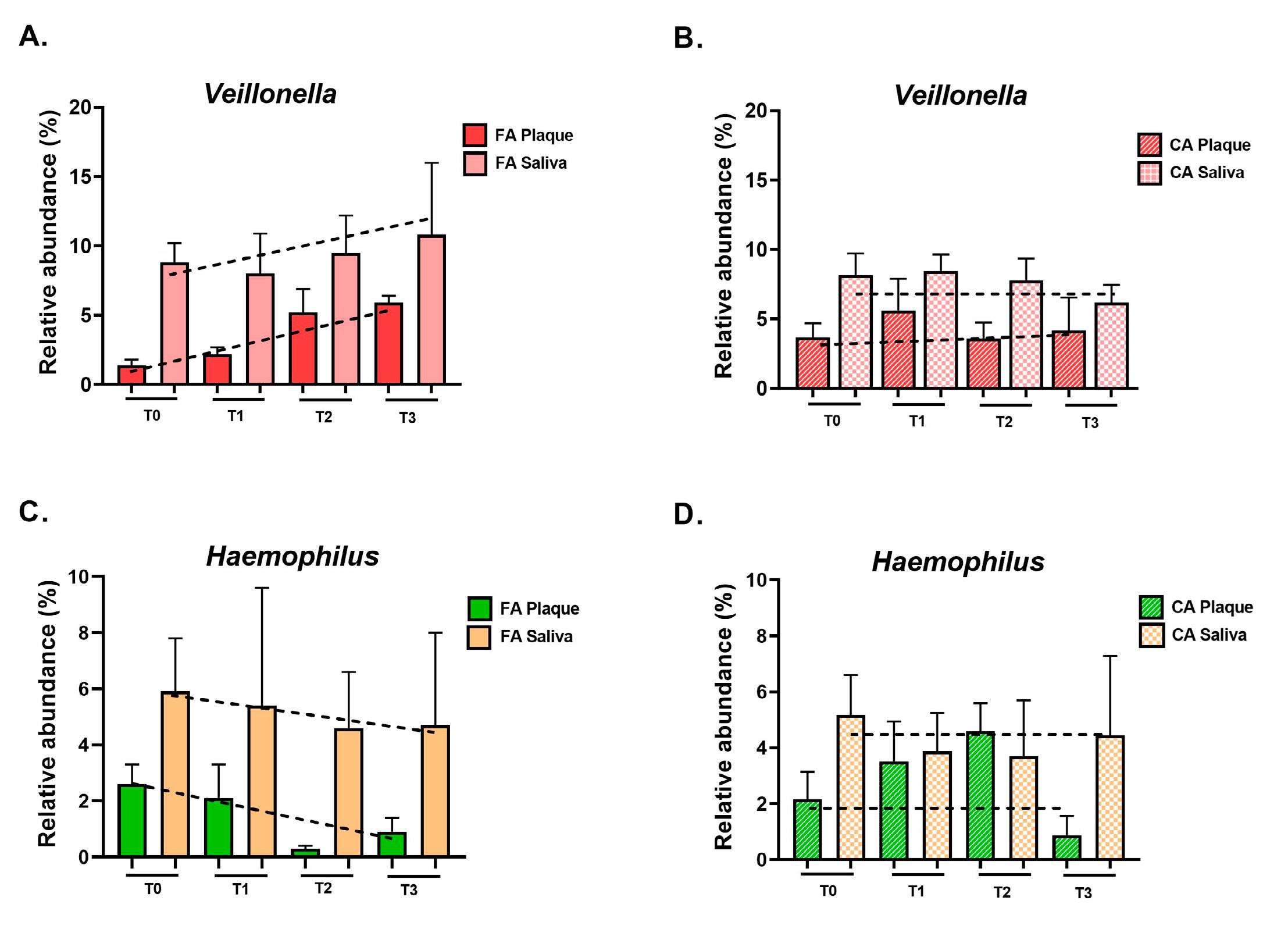

This study investigated the microbial changes during treatment with clear aligners (CA) and fixed appliances (FA) and evaluated the utility of saliva as a diagnostic marker in orthodontic patients.

Emily Duong, BS; Elaine Pham, BS; Julia Esfandi, BS; Kim-Sa Kelly, BS; Arvin Pal, DDS; Masooma Rizvi, DDS; Nini Tran, DDS, PhD; Tingxi Wu, DDS, PhD; Bhumika Shokeen, PhD; and Renate Lux, PhD

The purpose of this study was to determine if childhood exposure to adverse experiences in a Los Angeles dental population was related to current young adult tobacco, alcohol and drug behaviors.

Kenneth J Glenn, BS; Christina Light, BS; Todd Franke, MSW, PhD; and Shane N. White, BDentSc, MS, MA, PhD

CDA Foundation volunteers and donors truly change the lives of others. Through your generosity, Californians in underserved communities gain access to dental treatment that relieves pain, restores dignity, creates smiles and opens more opportunities.

As I glanced at my bookshelf that houses some of my favorite childhood titles, it was quite nostalgic to reread “Mary Alice Operator Number 9, Miss Nelson is Missing” and the unforgettable “The Berenstain Bears Visit the Dentist.” My name is printed proudly in just-learnedto-write letters in the upper left corner, and I sat imagining when I first turned the crisp new pages to now gently turning the weathered pages — both giving me such satisfaction. Fast forward multiple decades later and with a quick search on the web, the very same book is at my fingertips as an e-book or an audio book to listen to during my drive to work. Growing up split between generations certainly created a blend of culture — playing vinyl records and LPs on my record player, using a Compaq computer to play Frogger on the green screen, listening to cassettes and CDs on a boombox, to the big introduction of AOL (“you’ve got mail!”), mini-disc and mp3 players and social media platforms no longer in existence. Technological advancements, social trends and generational gaps continue to bare their teeth and shape our present and future times.

With the Merriam-Webster Dictionary constantly adding new words I have yet to encounter, understanding the ever-changing slang has been a humorous and now annual ritual at our family gatherings. Previously proud to use slang abbreviations like YOLO (you only live once), IMHO (in my humble/honest opinion) and SMH (shaking my head), I realized each year that I have become so cheugy (out of date and no longer trendy) that I might end up tripping over these generational gaps. Instead, I rely on my next generation of cousins to “educate” me on the latest craze, social media

platforms and new ways for easy and instant gratifications. Whether or not I choose to follow the next trend, clear communication between providers and patients, among health care team members and between family members has always been, and remains, imperative in building trust, strong rapport and a successful practice.

Recently, Fortune Magazine published an article by Lambeth Hochwald regarding the growing generation gaps in the workplace and what changes are to come. According to Hochwald, 40% of Americans currently have a supervisor who is younger than they are and millennials will be the dominant demographic population by 2025.1 Companies and organizations comprised of Gen Z (1997-2012), millennials (1981-1996), Gen X (19651980), baby boomers (1946-1964) and the Silent Generation (1928-1945) working together are demonstrating the demographic shift of workforce composition.2 Noting the higher percentage of younger supervisors, the traditional hierarchical mindset of “older age equals higher position” has begun to wane.

With dental student indebtedness on the rise, a 2022 survey study regarding general perspectives of orthodontists in the United States and Canada found significant variability among different generations in practice.3 The results of the study described that more technologically advanced and

costly equipment were utilized more often by the younger generation (notably with higher student debt) of orthodontists versus the Silent Generation.3 In addition, another significant difference was noted in practice marketing, with the younger generation relying heavily on social media platforms and the older generation limiting the budget to more traditional marketing.3 In a multigenerational team, collaborating and marrying the strengths of digital media with personal word-of-mouth supports the success of the health care team and practice.

In “Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce; Living, Learning and Earning Longer,” the authors explored the rapid changes in population demographics, highlighting the strengths of generational diversity in the workforce. The authors noted that a “key advantage of a multigenerational workforce is that it enables effective synergies between experienced and less experienced staff to the benefit of employers and employees.”4 But to accomplish this synergistic multigenerational workforce, support is needed for the dental team to bridge communication and behavior gaps; this may start with building a practice or health care team whose goal is to eliminate stereotypical references to each generation.4 Other examples include incorporation and development of training geared toward team or practice goals rather than

Technological advancements, social trends and generational gaps continue to bare their teeth and shape our present and future times.

segregated or siloed groupings of experience as well as practicing incentivization of overall production to showcase the collective impact that involves the multigenerational workforce rather than individual incentivization.4

FWIW (for what it’s worth), maybe it’s about time we catch up with MerriamWebster — IYKYK (if you know, you know). Take courses on implicit bias, communication and ways to diversify your team. The times of using pager code such as 424 (call me back) and 43770 (hello) have passed, and sooner than we think, Gen Alpha (2013-2025) will join the workforce. Now, if someone tells you, “These dentures are snatched!” — celebrate — that means you are on fleek aka on point! n

1. Hochwald L. Generation gaps are a growing workplace headache. Brian Chesky’s mentor is on a mission to bridge them Fortune September 2022.

2. Dimock M. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End

and Generation Z Begins. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; Jan. 17, 2019. Accessed Oct. 11, 2022.

3. Hussain SR, Jiang SS, Bosio JA. Generational perspectives of orthodontists in the U.S. and Canada: A survey study.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2022 Aug 30;S0889–5406(22)00476-0 doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.07.020 Online ahead of print.

4. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) . Good for business: Age diversity in the workplace and productivity. In: Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021.

Marisa K. Watanabe, DDS, MS, is a professor and associate dean for community partnerships and access to care at the Western University of Health Sciences, College of Dental Medicine. She currently serves on the board of the Medicaid|Medicare|CHIP Services Dental Association as the academic director and is the chair of the Los Angeles County Department, Oral Health Program Community Oral Health Improvement Plan, Workforce Development and Capacity Workgroup.

We reserve the right to edit all communications. Letters should discuss an item published in the Journal within the last two months or matters of general interest to our readership. Letters must be no more than 500 words and cite no more than five references. No illustrations will be accepted. Letters should be submitted at editorialmanager.com/ jcaldentassoc. By sending the letter, the author certifies that neither the letter nor one with substantially similar content under the writer’s authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere, and the author acknowledges and agrees that the letter and all rights with regard to the letter become the property of CDA.

Editor’s note: The following tributes to Dr. Dennis Kalebjian were written by CDA past president Dr. Debra Finney, who followed him as president in 2004, and by CDA past president Dr. Steve Chan, who preceded him as president in 2002.

March 1, 1954 - July 23, 2022

Most of you reading this will relate to Dr. Dennis Kalebjian through his professional career in dentistry. However, Dennis was so much more and that is what made him a truly great man. Let me offer some insight . . .

Dennis had a highly successful dental practice for 43 years in his home town of Fresno. In addition to providing general dentistry services in his office, he also treated special needs and medically compromised patients at a local hospital. He was involved in his community, through his children’s activities in sports and music, through his church and by his charitable treatment of the underserved. He was appreciated and respected in a community that saw him as a dedicated family man and a generous provider for those in need.

Along with his dental practice and

community and family activities, Dennis had some talents not as well known by his dental colleagues. He was a musician from an early age and played the piano for many family and community events throughout his life. He was also a farmer. His parents had a raisin farm that had been started by his grandparents and later maintained by Dennis and his son.

He had quite a repertoire of skills — from dentistry to music to driving a tractor. But there’s more! Somehow, he found time to devote to leadership in his profession. First in his local Fresno-Madera Dental Society where he served as president. Continuing on with his involvement, he served in positions with the CDA and ADA. He was CDA president in 2003.

Dennis was a quiet leader, thoughtful and pensive. He studied and considered all aspects of an issue before making a decision. And yet, in that patient demeanor, there

was a mischievous side lurking behind an impish smile that would spurt out amusing comments and observations catching those around him off guard. Although he could appear serious and indifferent, he was anything but. He had a warm and kind heart and was gentle and caring. He was an educator and mentor in his community and with his family. He imparted his love of music and dentistry to his children. We lost a treasured friend and colleague, but his family lost much more. We all lost a great man.

Dennis Kalebjian’s Opus Dennis had a lifelong passion for music. We honor his life with a symphonic metaphor.

Dennis Kalebjian, son of a Fresno raisin farmer, rose to become president of the California Dental Association (2003). He could hear melodies from afar. He could hear the possible.

Hypnotic melodies drew him from the vineyards to the auditoriums of the University of Pacific to the halls of the ADA and beyond.

This is his symphony of life.

To aspire

Ever hear a melody that’s so compelling, you stop.

You turn your head. You listen.

Dennis was that rising star, the voice of clarity.

He was the youngest, at the time, to chair a CDA Council, to chair the multimillion-dollar ADA Business Enterprise Inc. to lead the search for: an ADA Executive Director a TDIC CEO a CDA Executive Director

He was listening. Those around him were listening to him.

Concert Performance

Community Medical Center (Fresno)

His audience. Postgrad residents thought they would only hear how to do hospital dentistry. He would teach a long line of neophytes the melodies he could hear.

“Be the Best.” “Practice, Practice. Practice.”

His vocal chorus tolled about character, about community and about relationships.

For over 40 years, postgrad-program alumni sought him out.

“You once told me the melodies. I hear your songs in my head.

Now I sing the melodies that Dennis shared with me.”

The Captain’s Chair Dennis was the youngest up to that time to ascend to the CDA President.

9-11 was still fresh. Changing the CDA management was fresh.

Anti-amalgamists and denturists were attacking. U.S. Supreme Court FTC vs. CDA meant we had to adjust. The CDA Foundation was realized.

It’s said that the test of leadership is when you are tested.

Raising a Family

Juggling debt from school, starting a practice with wife Paulette during a recession and raising a family with three babies. The profession’s clarion call summoned. Yet Family always came first.

His legacy is family. Daughter Bridgit is a dentist. Son Brad is a fourthgeneration farmer. Daughter Jamie is an attorney. Grandbabies’ hugs from Penelope, Presley, Piper, Glen, Eileen, Andre and Lucy are priceless.

On July 23, 2022, Dennis raised his baton one last time. Sforzando!

Pancreatic cancer silenced the music.

Members of St. Gregory Armenian Apostolic Church sang his praises.

Compadres from Chicago, North Carolina and distant California borders came.

The Processional brought residents, patients and special patients from 43 years ago.

They came to say Good Bye to the man who touched their lives

The man who taught them to hear the music that he heard.

Many studies have indicated that the health of teeth and gums can influence the body elsewhere, including the brain. But other studies have been less conclusive, and much uncertainty remains about the strength and direction of this relationship. It’s possible, for instance, that the link can be explained by people developing poor dental health as a result of their early dementia, instead of the other way around — an example of something scientists call reverse causality. However, a recent study from the University of Eastern Finland that reviewed existing evidence found that poor dental health was linked to a later higher risk of cognitive decline and dementia. This increased risk was especially apparent for those missing some or all of their teeth. The study was published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

The research team sought to conduct an updated meta-analysis of the evidence so far, one that would try to account for these gaps in knowledge. They collected and analyzed 47 longitudinal studies that tracked people’s oral and brain health over time, looking specifically at those who hadn’t been diagnosed with dementia at the start of the study. Ultimately, they found that people with poor oral health were 23% more likely to eventually develop some amount of cognitive decline and 21% more likely to develop dementia. And of the various measures of oral health studied, they also found that tooth loss in particular was independently associated with cognitive decline and dementia.

The researchers caution that the evidence they examined is still limited and has many caveats, so it’s hard to draw firm conclusions. Many of the studies reviewed looked at different groups of people (some only included people over 65) or tracked them for different time periods, while others may have had methodological problems in their design. But the authors say theirs is the largest review of its kind to date. They also tried to account for reverse causality in a separate analysis and found that it could explain some but not all of the connection seen here.

In other words, while there might be a real cause-and-effect link between poor oral health and dementia, it will take more well-done research to better understand the specifics of this relationship, including the exact mechanisms behind it. Some scientists theorize, for instance, that the bacteria found in people with gum disease can help trigger or accelerate the complex chain of events that leads to dementia. The team behind this paper also notes that losing teeth could harm the aging brain by depriving people of familiar sensations. And other factors likely can negatively affect both the mouth and brain at the same time, such as nutritional deficiencies. n

The percentage of smokers who attempted to quit cigarettes dropped for the first time in a decade, according to a study published in the JAMA Network Open. Researchers attributed the phenomenon to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study is one of the first to offer insight into how smoking cessation changed during the pandemic. Some prior studies have suggested that the pandemic led to an increase in cigarette use among smokers as a stress-related coping mechanism. For other smokers, fears about the health risks of COVID-19 may have prompted a decision to reduce or quit tobacco products.

In the new cross-sectional study, researchers analyzed changes in smoking cessation-related behaviors throughout the COVID-19 pandemic using data from approximately 790,000 U.S. adult smokers. Researchers also gathered data from the nationally representative Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey and representative retail scanner sales data for nicotine replacement therapy universal product codes.

Researchers evaluated changes in the annual self-reported prevalence of past-year quit attempts and recent successful cessation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sales volumes of nicotine gum, lozenges and patches before and during the pandemic were calculated.

The annual number of past-year

A recent study in the Pediatric Dental Journal provides evidence of strong relationships between acidic drinks and dental erosion. Researchers from Misr International University in Egypt analyzed the effects of common beverages on deciduous teeth enamel and got results that were perhaps not shocking — carbonated soft drinks and acidic juices resulted in drastic softening and a serious reduction in enamel surface hardness and loss of surface structure of deciduous teeth at two- and four-weeks erosive challenge.

For the study, the researchers subjected a total of 52 human extracted deciduous molars to erosive challenge by cyclic immersion in four liquids — artificial saliva, strawberry-flavored milk, orange juice and the carbonated soft drink Pepsi — for a 28-day pH cycling protocol. The enamel surface microhardness and surface topography using a scanning electron microscope were assessed at baseline after two- and four-weeks of the erosive challenge.

Analysis found that Pepsi and orange juice showed high erosive potentiality affecting the enamel surface of the teeth while the milk-based beverage showed no difference from the artificial saliva.

Citing a “drastic burst” of consumption of carbonated soft drinks and juice among children during the COVID-19 pandemic, the study authors noted that if dental erosion is not controlled or stabilized, affected children may suffer from severe tooth surface loss, tooth sensitivity, poor esthetics and eventually the risk of dental abscesses of the affected teeth.

cessation attempts decreased for the first time since 2011 from 65.2% to 63.2%. The largest decreases were among individuals between the ages of 45 and 64, those with two or more comorbidities and Black individuals. The rate of recent successful cessation remained unchanged. Simultaneously, sales of nicotine replacement therapy brands decreased across the U.S. Compared with expected sales, observed sales during the pandemic were lower by 13% for lozenges, 6.4% for patches and 1.2% for gum. Smoking cessation activity decreased amid the COVID-19 pandemic and remained

depressed for more than a year.

These findings suggest a decrease in smoking cessation activity during the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to reengage smokers in evidence-based quitting strategies, according to the researchers.

The Black Death was a bubonic plague in the 14th century and is known as the most fatal pandemic in history, killing millions across Europe, Africa and Asia. The cause of the bubonic plague comes from the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which is commonly spread by fleas.

Researchers for years have been

looking for where the pandemic originated and recently found DNA evidence of the bacteria inside of ancient teeth from the bodies of people buried in modern-day Kyrgyzstan. The ancient teeth DNA dates all the way back to 1338 when the plague was beginning to grow.

Johannes Krause, PhD, a professor at

the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and several other researchers co-authored the study that was published in the journal Nature.

A San Diego State University study found that more generous Medicaid payment policies were associated with significant but modest increases in children’s preventive dental visits and excellent oral health. The study was published in the JAMA Health Forum

In the cross-sectional study, researchers set out to evaluate the association between the ratio of Medicaid payment rates to dentist charges for an index of services (fee ratio) and children’s preventive dental visits, oral health and school absences. Relative to previous studies of children’s dental visits, the research team examined a more recent period after the major U.S. health care reform that included the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and the inclusion of dental as an essential health benefit for children.

A difference-in-differences analysis was conducted between September 2021 and April 2022 of 15,738 Medicaid-enrolled children and a control group of 16,867 privately insured children aged 6 to 17 years who participated in the 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health. Exploratory subgroup analyses by sex and race and ethnicity were also performed.

The study found that more generous Medicaid payment policies were associated with significant but modest increases in children’s preventive dental visits and excellent oral health. To the authors’ knowledge, their study is among the first to assess whether Medicaid dental payment rates are associated with improvements in children’s oral health and school absences and to document whether associations differ by sex and race and ethnicity. The authors noted that further research is needed to understand the potential association between policies that improve access to dental care and children’s academic success.

“What we found in this burial ground … was the ancestor of four of five of those lineages — so it’s really like the big bang of plague,” Dr. Krause said at a news conference. “So we have basically located this origin in time and space, which is really remarkable.”

Researchers believed for a long time that burial sites in Kyrgyzstan, which have 467 tombstones spanning nearly 900 years, could possibly have the remains of people who died from the plague. There are 118 graves dated between 1338 and 1339, and the high number in just two years caught researchers’ attention.

Researchers then examined seven teeth from seven different people buried and found evidence of the bacteria inside of dried blood vessels in the teeth. They then determined that the bacteria strain in the teeth “was an ancestor of genomes from victims of the Black Death about eight years later.”

Zohra Tumur, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor in the College of Dental Medicine at Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

If at first, you don’t succeed, search, search again. That’s why they call it research. – Unknown

“How is research going?” I asked, and my friend replied, “research is research.” We both laughed. However, this conversation resonated with me for years.

The Oxford Dictionary defines research as “the systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources to establish facts and reach new conclusions.” Research takes years of hard work and dedication before it reaches its conclusion. Nevertheless, the new information and knowledge acquired contributes to the advancement of science and technology. In health care, research plays a crucial role in discovering new therapeutic approaches, making evidence-based decisions and establishing better health policies.

Albert Szent-Gyorgyi (winner of the Noble Prize in Medicine in 1937) said, “Research is to see what everybody else has seen, and to think what nobody else has thought.” Research is a process that starts with careful observation, critical analysis of the situation and developing research questions and hypotheses. Next comes the process of research design, data collection, analysis and interpretation. Finally, research ends disseminating findings to a greater audience. Actually, research does not end there; it opens doors for future research questions and opportunities, and it continues.1

Science and research played a crucial role in the development of the dental profession and dental education and have

become a core of modern dentistry. Dental research scientists and clinical scholars contributed tremendously to understanding complex human diseases and disorders beyond the diseases of the oral cavity during the last half of the 20th century.2

The January 2020 issue of the Journal highlighted the importance of research in dental education. Dr. Paul Krebsbach, dean of the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Dentistry, started his introduction by emphasizing the importance of generating new knowledge to build a vibrant dental professional future. The authors in that issue emphasized the crucial role of research in dental education by stating that research helps dental students to deeply understand the biosocial foundation of the dental profession and acquire critical thinking abilities. They also emphasized the importance of exposing students to advanced science and technology to create a competent dentistscientist workforce necessary to compete in today’s precision health care environment.3

To support student research, the Journal highlights students’ research work in special issues. Students from dental schools in California are encouraged to submit their research and share it with a greater audience.

Even with restricted access to research during the COVID-19 pandemic, dental schools adapted to the new changes and exhibited resilience and creativity to continue all parts of dental education, including research programs. In the January 2022 issue of the Journal, dental students shared their research on how

dental schools adapted to the pandemic. This Journal issue presents diverse research topics in dentistry. Students from the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry contributed “Management of Hypertensive Crisis in a Dental School: 10-year Retrospective Review of Medical Emergency Incidents With Recommendations,” which includes the opportunity to earn continuing education credit, and “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Periodontal Data Collection Practices in Second-Year Dental Students.” Students from the University of California, San

Francisco, analyzed user feedback in their article “Rollout of the Oral Health Literacy Toolkit in California: A Mixed-Method Analysis.” The articles “Salivary and Plaque Microbiomes During Treatment With Different Orthodontic Appliances” and “Childhood Adversity Correlates With Young Adult Health Dental Patient Behaviors” were submitted from the University of California, Los Angeles.

I am very pleased to work with the CDA team to support student research publications. We truly appreciate all the authors who submitted articles to CDA.

It shows their resilience, determination, commitment and dedication to scientific discovery and to creating safe and effective dental health services. We applaud all the students, mentors and CDA administration who brought this Journal issue to life. We hope readers enjoy it. n

1. Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research: Applications to evidence-based practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2020.

2. Slavkin HC. The Impact of Research on the Future of Dental Education: How Research and Innovation Shape Dental Education and the Dental Profession. J Dent Educ 2017 Sep;81(9):eS108–eS127 doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.041

3. Krebsbach P. Ensuring a Vibrant Future for Dentistry Through Research and Discovery. J Calif Dent Assoc 2020 Jan;48(1)

Soh Yeun Kim, DDS; Sarah Lim, BA; Lauren Barlow, BS; Chanmee Esther Kim, BS; Adlene Chang, BA; Holli Riter, DDS; Iris Nam, DDS; Heidi Christensen, DDS; and Udochukwu Oyoyo, MPH

Background: The objective of this study was to analyze the type and frequency of medical emergency calls made at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry (LLUSD) and to reinforce the guideline for the most frequent incident.

Methods: Emergency call data from the past 10 years at LLUSD were collected and categorized according to the type and frequency of medical emergencies. The most frequent emergency data was identified, and additional information was gathered using the patients’ electronic health records in the axiUm database.

Results: Emergency calls related to hypertension (HTN) were the most common emergency calls encountered at LLUSD and comprised 32.9% of the calls (95% confidence interval (CI): 29.1, 36.9). HTN-related calls peak at age groups 50 to 80 (P < 0.05). Seventy-seven percent of patients who had emergency calls had an existing HTN. Out of the total HTN incidences, 11% were transported to the emergency room (ER) (95% CI: 7.86, 12.2).

Conclusions: The most frequent medical emergency call at LLUSD was related to hypertension. A revised HTN guideline is recommended to guide dental providers to determine when to call emergency medical service (EMS) or when to consider a medical consultation with a patient’s physicians to minimize reports that do not require immediate management. Providers must also consider the patient’s individual health history, background and comorbidity.

Practical implications: The proposed updated HTN treatment guideline will guide dentists or staff on whether to call EMS for immediate treatment or refer to a patient’s physician for HTN care.

Keywords: Medical emergency, hypertension, hypertensive emergency, hypertensive urgency, guideline

Soh Yeun Kim, DDS, is an assistant professor and course director of patientcentered care II at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Sarah Lim, BA, is a fourthyear dental student at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Lauren Barlow, BS, is a fourth-year dental student at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Chanmee Esther Kim, BS, is a fourth-year dental student at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Adlene Chang, BA, is a fourth-year dental student at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Holli Riter, DDS, is an associate professor and a director for the special care dentistry department at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Iris Nam, DDS, is an assistant professor and clinician in the special care dentistry department at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Heidi Christensen, DDS, is a professor and patient care manager at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Udochukwu Oyoyo, MPH, is an assistant professor and statistician at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported for all authors.

Medical emergencies in a dental office setting are not unexpected. As the human lifespan increases, so does the incidence of chronic disease.1,2 This in turn means that the likelihood of having a serious medical emergency in the dental environment also increases.3 While there is limited data available as to the frequency of medical emergencies in dental settings, survey data showed that 3 in 4 dentists report having some kind of medical emergency in their office.4 Recent trends in the health care environment require that dental health professionals become more involved in the management of the general health of patients and address related emergencies when they arise.

Although the majority of the emergencies in a dental setting are not life threatening,5 the dental practitioner needs to be prepared for all types of emergencies. Proper training for medical emergencies is part of the dental school curriculum, but dentists and dental students often report that they feel underprepared to handle the emergencies in their practices.6 The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) provides accreditation standards for dental education programs. CODA Standard 2-23 states that students “must be competent in providing oral health care within the scope of general dentistry, as defined by the school” including “dental emergencies,”7 which we define to include medical emergencies. Despite the preparation and education on emergencies taught in dental school, dealing with

medical emergencies often causes high anxiety among dental students and practicing dentists. In order to better educate students on ways to reduce potential risks and to improve the quality of care delivered, it is important that we identify the adverse events seen most commonly in the dental education setting. It is vital to improve the management process of medical emergencies, dental professionals’ awareness and education and reduction of the frequency of medical emergencies.8

Identifying ways to reduce dentalsetting emergencies and training dental students to look for prevention strategies is of high importance. A recent investigation found that 35% of dental patients who had an emergency in the dental office had a history of systemic disease, with about a third of those patients having a history of cardiovascular disease.9 The ability to collect and interpret a thorough health history as well as to correlate the health history with potential medical emergencies are vital to the improvement of the level of preparedness of the dental team and the reduction of anxiety related to managing emergencies during dental treatment.

This 10-year retrospective study analyzes the past medical emergency inhouse calls at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry (LLUSD). The objective of this study was to analyze the type and frequency of emergency call reports made in LLUSD and to reinforce the guideline for the most frequent incident to aid in decision-making of the

Medical emergency is identified and x8333 is called.

Emergency response team shows up at the specified area.

Emergency response team evaluates the subject and scene.

If transportation to hospital (ER) is indicated

If transportation to hospital (ER) is NOT indicated

911 or EMS is called. Basic medical assistance or treatment will be provided in the meantime. Upon EMS arrival, subject will be transported to hospital (ER).

Emergency response team includes an RN, dental anesthesiologist, staff from clinic supply, dental maintenance and clinic manager’s office

FIGURE 1. LLUSD in-house emergency call (8333) flow chart.

students, staff, faculty and other dental professionals. This study is unique in that the most common emergency call in a dental school setting is analyzed and the trend of the most common emergency is further investigated.

This retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board (IRB #5210442). In order to manage medical emergencies at LLUSD, an immediate response protocol is in place for any medical emergencies that occur within the dental school building during regular business hours (f IG ure 1 ). All predoctoral and most postdoctoral dental clinics are located in this building. The emergency team responds to all emergencies called through an in-house emergency call number, 8333, whether the subject is a dental school patient, student, faculty member, staff or visitor. The response team includes a registered nurse and dentist anesthesiologist from the dental anesthesia department, a clinic

Basic medical assistance or treatment will be provided. It will be determined if the dental treatment will be continued or discontinued.

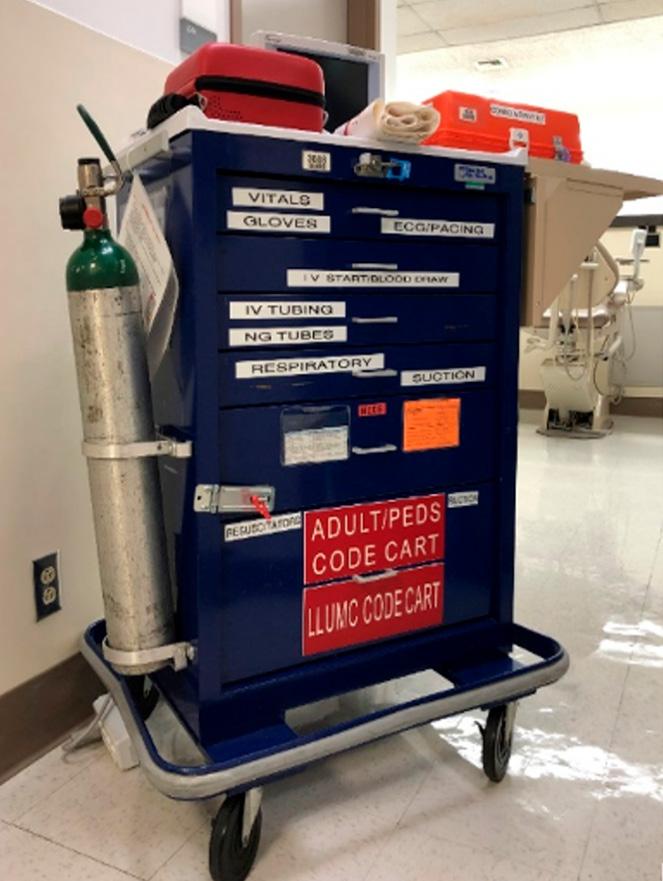

supply staff member who is responsible for the emergency code cart (f IG ure 2 ), a dental maintenance staff member for crowd control and a staff member from the dental clinic manager’s office. The latter is responsible for completion of the incident report of the emergency, using a medical emergency report and submitting an unusual occurrence report (UOR) form. These reports are compiled and stored in the dental clinic manager’s office and are reviewed at the request of the clinical quality assurance committee. Recommendations for changes, updates or other process improvements will then be given to the appropriate stakeholders.

Medical emergency incident data from January 2012 to October 2021 in which an internal or in-house medical emergency call was dialed was collected from the medical emergency reports compiled from the LLUSD clinic manager’s office. The data were analyzed after being summarized by type and frequency of medical emergency calls. The most frequent emergency data was identified, and additional information was gathered using

Incident report will be filled out in the dental manager’s office.

FIGURE 2. LLUSD emergency code cart.

the patients’ electronic health record in the axiUm database. This information included the subject’s age, gender and history of hypertension. The information regarding the necessity of transportation to an ER of the hospital was obtained from the compiled report stored in the LLUSD

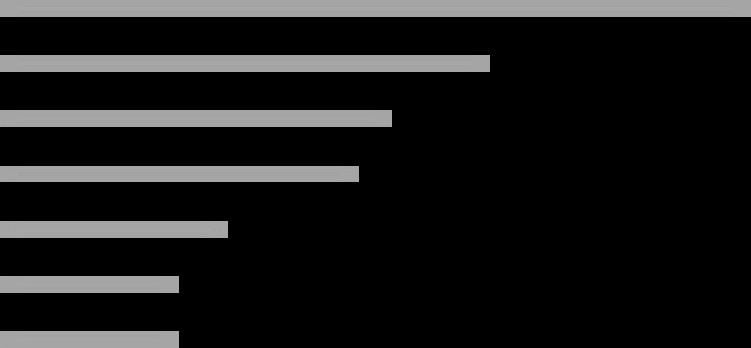

Frequency 193 83 56 52 50 33 24 9 7 4 75 586

Groups 20-30 30 20 10 0 5 8 23 26 27

clinic manager’s office. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and proportions were used to characterize the cohort data; jamovi software was utilized for analysis, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported where appropriate.

Overall, 586 in-house medical emergency calls were recorded during the duration of this study from January 2012 to October 2021. f IG ure 3 presents the types and frequency of emergency incidents in descending order. Emergency calls related to hypertension (HTN) were the most common emergency calls encountered at LLUSD. A total of 193 calls were made for HTN, which comprised 32.9% of the

calls (95% CI: 29.1, 36.9). The second most common type of medical emergency calls was dizziness, of which 83 incidents were recorded (95% CI: 11.4, 17.3). The frequency of falling was 56, syncope was 52 and swallowing objects such as crowns, burs or instruments was 50. Anxiety followed with a frequency of 33, allergy was 24, low blood glucose was nine, low blood pressure was seven and seizure was four. The category of “other” includes nausea, chest pain, nosebleed, throat irritation, high blood sugar, shortness of breath, stroke symptoms, presyncope (a feeling that you may faint but you do not), stomach pain, wheezing, swelling of ankles, knee pain, cold and shaking, pain, weakness, unresponsive, extensive

age

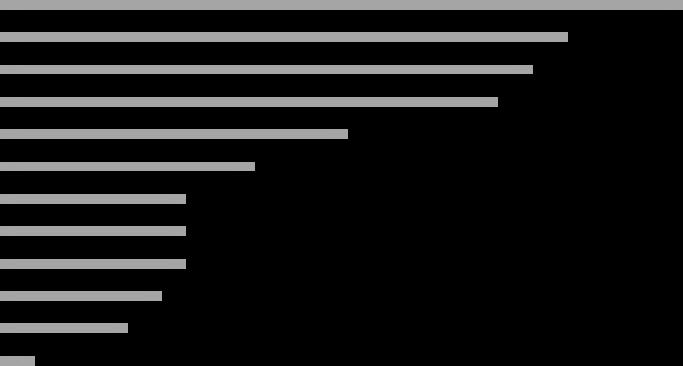

20–30 31–40 41–50 51–60 61–70 71–80 < 81 Totals (3 unknown) Female 2 1 5 23 27 26 10 94 Male 0 5 8 26 26 22 9 96 10 26 22 Female Male FIGURE 4. Frequencies of LLUSD in-house medical emergency calls (8333 calls) by age group. 2 1 5 26 9

bleeding, palpitations, headache and uncategorized. f IG ure 4 breaks down HTN incidences by age group and gender. Age was categorized into seven categories ranging from 20 to 81 and older and divided into 10-year intervals. Each age group contains a male and female bar, and female data is indicated by light blue color while male data is indicated by dark blue. There was no difference between incidences by gender, but the data indicated higher incidences with increasing age (p < 0.05). The difference of frequency between the genders varies no more than four, and the overall data creates a bell curve leaning to the right. The bell curve peaks at age groups 50-80 and the overall data

Prior diagnosis Undx+Unknown total

indicates higher incidences with age.

f IG ure 5 represents the percent of calls made for patients who lacked or had prior diagnosis of HTN. Seventyseven percent of patients who had emergency calls made reported that they have existing HTN conditions.

f IG ure 6 describes the frequency of yearly HTN calls and those that were transported to the ER upon evaluation from the in-house medical team. HTNrelated emergency calls were made the most in 2013 and 2019; 31 and 30 calls were made respectively. Out of the total HTN incidences from 2012 to 2021, 11% were transported to the ER, which shows 95% confidence intervals (95% CI: 7.86, 12.2).

In this retrospective study, we gathered data on the types and frequency of medical emergencies at LLUSD over a 10-year period. The most common type of medical emergency call at LLUSD in the past 10 years was high blood pressure-related calls comprising 32.9% of all calls. This finding was significant to focus on hypertensionrelated emergency calls. The second most common calls were dizziness, having been observed in 14.2% of emergency calls. HTN-related calls were observed more than twice as frequently as dizziness.

In May 2020, according to the American Heart Association (AHA), nearly half of U.S. adults — an estimated 116 million — have high blood pressure.10 High blood pressure is defined as a systolic reading of 130 or higher or diastolic of 80 or higher. AHA news also stated that the percentage of people who have hypertension in the U.S. increases as they age,10 and this trend was also found in HTN-related calls at LLUSD (P < 0.05). More calls were made for the 50-80 age groups.

The HTN treatment guidelines

23% 77%

Hypertension total 10 years Prior diagnosis Undx+Unknown total % diagnosed

FIGURE 5. HTN-related calls and existing HTN history.

developed at LLUSD in 2009 (TABLE 1 ) assert that any blood pressure (BP) over 180/110 mmHg is a contraindication for any dental treatment. According to the American College of Cardiology and AHA, the 2017 guidelines for hypertensive crisis is 180/120 mmHg or greater.11 HTN crisis can be defined as a hypertensive emergency or urgency depending on the involvement of organ damage. Hypertensive emergency is a rapid increase in blood pressure that can result in end-organ damage.12 Hypertensive urgency is characterized by an increase in blood pressure without showing signs or symptoms of acute organ damage and does not involve immediate risk; therefore, the treatment for hypertensive urgency can be done after the patient is dismissed within 24 to 48 hours, and oral antihypertensive therapy or medication is usually sufficient.13–16 Whelton et al. stated that these hypertensive urgency patients are not having a hypertensive emergency and therefore do not require immediate BP reduction in the emergency department.11 However, recognizing or identifying

193 149 46 77.20207254

hypertensive emergencies is very critical because end-organ damage can cause fatal medical situations12 that need hospital assistance.13 When organs are affected, immediate intervention in a hospital or intensive care setting is required to lower the blood pressure.12,14,17 Associated symptoms can include chest pain, headache, vision changes, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, confusion, etc. With these symptoms present, a patient should be referred to EMS to be transported to a high level of care in order to prevent further organ damage or other adverse sequelae.12 Associated examples of organ damage include acute ischemic stroke, acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris, acute renal failure and dissecting aortic aneurysm.11

A systematic review done by Astarita et al. regarding hypertensive emergencies and urgencies in the emergency department showed that both hypertensive emergencies and urgencies are frequent reasons of emergency room visits, and hypertensive urgencies were significantly more common than hypertensive emergencies.18 Hypertensive

Current LLUSD Hypertension Treatment Guideline

Systolic BP Diastolic BP

Medical risk factors present Recommendations 120–139 80–89 Yes or no (see examples in the caption below)

Routine dental care OK; discuss BP guidelines with patient 140–160 90–99 Yes/no

Routine dental care OK; consider stress reduction protocol; recommend medical consult 161–179 100–109 No

Routine dental care OK; consider stress reduction protocol; recommend medical consult 161–179 100–109 Yes

Urgent dental care only; consider stress reduction protocol; medical consult required before further treatment 180–209 110–119 No

No dental treatment without a medical consult; refer for prompt medical consult 180–209 110–119 Yes No dental treatment; refer for emergency medical treatment > 209 > 109 Yes/no No dental treatment; refer for emergency medical treatment

Examples of medical risk factors: medical history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, high coronary artery disease risk, recurrent stroke history, diabetes, chronic renal disease, pregnancy, patient age factor, etc.

120-129/ and /<80

130-160/ or /80-99

Yes/No

Yes/No

161-180/ or /100-120 No

161-180/ or /100-120 Yes

>180/ and/or />120 Yes/No

>209/ and/or />120

No contraindications to routine dental care. Discuss BP guidelines with patient.

Minimal risk to routine dental care. Stress reduction protocol; recommend medical consult.

Routine dental care with precautions. Stress reduction protocol, refer for medical consult.

Urgent dental care only. Stress reduction protocol; medical consult required for further treatment.

No dental treatment without a medical consult. Refer for medical consult. No dental treatment.

Refer immediately to patient’s primary care provider or urgent care.

If any symptoms of hypertensive crisis are present, call in-house medical emergency number (or call EMS if it is private practice setting).

HTN crisis signs or symptoms: Headache, altered mental status, blurred vision, numbness or weakness, pressure or tightness in the chest, chest discomfort or pain, difficulty breathing, diaphoresis, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, etc.

Risk factors or comorbidities: Medical history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, high coronary artery disease, recurrent stroke history, diabetes, chronic renal disease, patient age factor, seizure, anxiety, etc.

Pregnant patients: Any pregnant patient with a systolic blood pressure >160 or diastolic >110 should not receive routine care and should be referred to the patient’s prenatal care provider immediately.25

urgency was also the more common trend found in LLUSD. After analyzing the emergency call data at LLUSD, it was determined that the asymptomatic or nonemergent HTN calls were more prevalent than symptomatic calls. Among the HTN-related calls, 11% were transported to the emergency department, and these can be considered hypertensive emergencies (f IG ure 6 ). Many BP reading levels that prompted in-house medical emergency calls did not have to be considered a true emergency, as the patients could have been referred to a physician or urgent care facility with a medical consultation. In practice, this lack of distinction could result in an unnecessary call to EMS. Based on this study, additional education or proposed updated institutional guidelines (TABLE 2 ) regarding management of HTN patients would be beneficial to

students, faculty and staff to help make better decisions regarding emergency calls and disposition of patients with high blood pressure in a dental setting.

Hypertension is commonly seen in dental settings. One study done by Kellog and Gabetti showed that nearly one-third of the sample patients in their dental school clinic had high blood pressure and emphasized the importance of monitoring hypertensive patients and providing appropriate dental care.19 Seventy-seven percent of patients who had HTN-related emergency calls at LLUSD had a history of existing hypertension (f IG ure 5 ), and their HTN measurement at the time of their LLUSD dental appointment was high enough to make the calls. The prevalence study of hypertension at a dental school shows that HTN is often undiagnosed or uncontrolled;20 therefore, the role of

dental professionals is vital in that dental clinicians can help patients receive more managed treatment for their hypertension by sending a medical consultation or referring patients to physicians. Twentythree percent of patients who had HTNrelated emergency calls at LLUSD did not report a history of diagnosed hypertension (f IG ure 5 ), and they may have benefited from referral to a medical provider to evaluate their high blood pressure and possibly diagnose hypertension.

When hypertension is noted, several factors must be considered. Several measurements of blood pressure need to be done to confirm the finding, and potential high blood pressure triggers should be looked into.13 Errors in measurement of blood pressure are common; therefore, appropriate patient preparation and use of accurate measurement technique are vital parts of proper blood pressure evaluation.11

Clinicians must consider if a patient has dental anxiety as a trigger because anxiety is associated with blood pressure elevation.21 The possibility of white coat hypertension also needs to be screened at dental offices. The prevalence is higher with older patients, and 1% to 5% of white coat hypertension may convert to sustained hypertension, which shows elevated blood pressure both in-office and out-of-office settings.11 Clinicians must check if the patient took their scheduled blood pressure medications as well.

Comorbidity is also significantly important. Certain risk factors or comorbidities may limit the treatment guidelines and affect the decisionmaking process.11 When a patient has other medical risk factors, a patient’s cardiovascular disease can result in a very serious emergency situation. One case report done by Thoms et al. showed the case of a patient with a history of hypertension, angina, end-stage renal disease and other conditions who had a cardiovascular collapse during a routine dental procedure.22 This life-threatening situation can happen in any dental clinic. This case study also suggested that the emergency response plan needs to be developed to minimize serious events during the dental procedure. According to the study by Southerland et al., risk factors for hypertension include age, obesity, family history, race, diabetes, dyslipidemia, tobacco use, stress, high-sodium diet and depression.23

Providing dental students with appropriate education regarding how to manage hypertension patients in a dental setting is crucial. First-year dental students at LLUSD are introduced to the HTN treatment guideline with a lecture. Second-year dental students learn HTN in depth in the pathology class and are further trained with casebased scenarios regarding HTN patients.

They are also tested on how to measure blood pressure accurately and on the management of HTN patients with different scenarios during objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). Third- and fourth-year students apply the knowledge to their actual patient care setting. The students may need additional calibrations or training updates to make sure they are up to date with the guideline, as repeating simulation or scenario-based training has been shown to be beneficial. A study by Manton et al. showed the resident groups who received

utilized in any dental school settings to educate students, faculty and staff and aid the decision of providing patients with dental treatment or disposition of patients with HTN when the patients do not present emergent symptoms. It will also be useful in private-practice settings as it will guide dentists or staff on whether to call EMS or refer to a patient’s physician for HTN treatment. Patients with nonemergent hypertension can be seen safely in the clinic12 when clinicians follow the HTN management guidelines.

The possibility of white coat hypertension also needs to be screened at dental offices.

The limitation of this study is that only HTN-related calls and trends were the focus of this project. Because nearly one-third of the total emergency calls were HTN related, this was considered significant enough to investigate and make the project’s sole focus. However, addressing other common emergency calls (dizziness, falling, swallowing objects, etc.) in more detail could be future research projects.

simulation-based medical emergency curriculum performed significantly better than the residents in a control group.24

The significance of this study is that it identified the most common emergency calls in a dental school setting in the last 10 years with 95% confidence interval, and the trend emphasized the importance of following HTN guidelines to make decisions on HTN patient management. Members of LLUSD and readers in other dental-profession settings will gain knowledge from this project for the trend of hypertensive crisis and when it is appropriate to call EMS during hypertensive crisis. The proposed updated LLUSD HTN treatment guideline, which includes HTN emergency symptoms and updated HTN measurement readings (TABLE 2 ), can be

The most frequent medical emergency call at LLUSD was hypertension (HTN). A revised HTN treatment guideline is recommended to guide dental providers to determine when to call EMS or when to consider medical consultation of HTN patients. Providers must also consider the patient’s individual health history, background and comorbidity. n

1. Anders P, Comeau R, Hatton M, Neiders M. The nature and frequency of medical emergencies among patients in a dental school setting. J Dent Educ 2010;74(4):392–6

2. Niessen LC, Fedele DJ. Aging successfully: Oral health for the prime of life. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2002 Oct;23 Suppl 10:4–11

3. Dym H. Preparing the dental office for medical emergencies. Dent Clin North Am 2008 Jul;52(3):605–8, x doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.02.010

4. Collange O, Bildstein A, Samin J, et al. Letter to editor: Prevalence of medical emergencies in dental practice. Resuscitation 2010 Jul;81(7):915–6 doi: 10.1016/j. resuscitation.2010.03.039

5. Haas D. Management of medical emergencies in the dental

office: Conditions in each country, the extent of treatment by the dentist. Anesth Prog 2006 Spring;53(1):20–4 doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2006)53[20:MOMEIT]2.0.CO;2 PMCID: PMC1586863

6. Clark M, Wall B, Tholström TC, et al. A 20-year follow-up survey of medical emergency education in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ 2006 Dec;70(12):1316–9

7. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental education programs. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2017.

8. Sorenson AD, Marusko RM, Kennedy KS. Medical emergencies in the dental school setting. J Dent Educ 2021 Jul;85(7):1223–1227 doi: 10.1002/jdd.12590. Epub 2021 Mar 22. PMID: 33754336.

9. Alhamad M, Alnahwi T, Alshayeb H, et al. Medical emergencies encountered in dental clinics: A study from the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. J Fam Community Med 2015 Sep–Dec;22(3):175–9 doi: 10.4103/22308229.163038

10. American Heart Association. Is high blood pressure inevitable? Here’s how to keep it in check. 2020, May 18.

11. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ ASPC/NMA/PCNA. Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018 Jun;71(6):e13–e115. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. Epub 2017 Nov 13. Erratum in: Hypertension 2018 Jun;71(6):e140–e144. PMID: 29133356.

12. Suneja M, Sanders ML. Hypertensive emergency. Med Clin North Am 2017 May;101(3):465–478 doi: 10.1016/j. mcna.2016.12.007. Epub 2017 Mar 2. PMID: 28372707.

13. Sobrino Martínez J, Doménech Feria-Carot M, Morales Salinas A, Coca Payeras A. Crisis hipertensivas: Urgencia y emergencia hipertensiva [Hypertensive crisis: Urgency and hypertensive emergency]. Medwave 2016 Nov 18;16(Suppl4):e6612. Spanish. doi: 10.5867/ medwave.2016.6612. PMID: 28055998.

14. Henny-Fullin K, Buess D, Handschin A, Leuppi J, Dieterle T. Hypertensive Krise [Hypertensive urgency and emergency]. Ther Umsch 2015 Jun;72(6):405–11. German. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930/a000693. PMID: 26098191.

15. Maloberti A, Cassano G, Capsoni N, Gheda S, Magni G, Azin GM, Zacchino M, Rossi A, Campanella C, Beretta ALR, Bellone A, Giannattasio C. Therapeutic approach to hypertension urgencies and emergencies in the emergency room. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2018 Jun;25(2):177–189 doi: 10.1007/s40292-018-0261-4 Epub 2018 May 18. PMID: 29777395.

16. Bales A. Hypertensive crisis. How to tell if it’s an emergency or an urgency. Postgrad Med 1999 May 1;105(5):119–26, 130 doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.05.1.735 PMID: 10335324.

17. Adebayo O, Rogers RL. Hypertensive emergencies in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015 Aug;33(3):539–51 doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2015.04.005. Epub 2015 May 30. PMID: 26226865.

18. Astarita A, Covella M, Vallelonga F, Cesareo M, Totaro S, Ventre L, Aprà F, Veglio F, Milan A. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies in emergency departments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 2020 Jul;38(7):1203–1210 doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002372. PMID: 32510905.

19. Kellogg SD, Gobetti JP. Hypertension in a dental school patient population. J Dent Educ 2004 Sep;68(9):956–64 PMID: 15342656.

20. Gordy FM, Le Jeune RC, Copeland LB. The prevalence of hypertension in a dental school patient population. Quintessence Int 2001 Oct;32(9):691–5. PMID: 11695137.

21. Ifeagwazi CM, Egberi HE, Chukwuorji JC. Emotional reactivity and blood pressure elevations: Anxiety as a mediator. Psychol Health Med 2018 Jun;23(5):585–592 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1400670. Epub 2017 Nov 6. PMID: 29105504.

22. Thoms S, Cooke M, Crawford J. Cardiovascular collapse associated with irreversible cardiomyopathy, chronic renal failure and hypertension during routine dental care. Anesth Prog 2016 Spring;63(1):34–41. doi: 10.2344/0003-300663.1.34. PMID: 26866410; PMCID: PMC4751519.

23. Southerland JH, Gill DG, Gangula PR, et al. Dental management in patients with hypertension: Challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2016 Oct 17;8:111–120 doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S99446. eCollection 2016. PMCID: PMC5074706

24. Manton JW, Kennedy KS, Lipps JA, Pfeil SA, Cornelius BW. Medical emergency management in the dental office (MEMDO): A pilot study assessing a simulation-based training curriculum for dentists. Anesth Prog 2021 Jun 1;68(2):76–84 doi: 10.2344/anpr-67-04-04 PMID: 34185862; PMCID: PMC8258755

25. Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, Karumanchi SA, McCarthy FP, Saito S, Hall DR, Warren CE, Adoyi G, Ishaku S. International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis and management recommendations for international practice. Hypertension 2018 Jul;13:291–310 doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.05.004 Epub 2018 May 24. PMID: 29803330.

THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR, Soh Yeun Kim, DDS, can be reached at sokim@llu.edu.

This worksheet provides readers an opportunity to review C.E. questions for the article “Management of Hypertensive Crisis in a Dental School: 10-year Retrospective Review of Medical Emergency Incidents With Recommendations” before taking the C.E. test online. You must first be registered at cdapresents360.com. To take the test online, click here. This activity counts as 0.5 of Core C.E..

1. Which of the following statements apply to this study? (mark all that apply)

a. It analyzed medical emergency calls made at Loma Linda University School of Dentistry over a 10-year period.

b. It identified hypertension (HTN) as the most common reason for an emergency call.

c. It proposed updated patient management guidelines for HTN.

d. It recommended that the revised HTN treatment guideline could assist dental providers to determine when to call EMS or when to consider medical consultation of HTN patients.

2. The authors used which of the following methods for their study? (mark all that apply)

a. Medical emergency incident data from January 2012 to October 2021 in which an internal or in-house medical emergency call was made.

b. Data was summarized by type and frequency of medical emergency calls and then analyzed.

c. Additional information was collected from patients’ electronic health records and analyzed, including age, gender, history of hypertension and whether they were transported to the ER.

d. All of the above.

3. True or False: Hypertension (HTN) was identified as the most common medical emergency at a rate of more than twice the next most common emergency complaint.

4. Which of the following emergencies was the second most frequent reason for an emergency call from the LLUSD clinic?

a. Anxiety.

b. Fainting.

c. Low blood sugar.

d. Dizziness.

e. Swallowing a foreign object.

5. What was the percentage of people who had an HTN-related emergency call at LLUSD but had not reported a history of HTN?

a. 12%

b. 17%

c. 23% d. 27%

e. 30%

6. The authors state that errors in measurement of blood pressure (BP) are common and note that which of the following should be evaluated for possible influence on BP readings (mark all that apply):

a. Poor measurement technique. b. Dental anxiety. c. White coat hypertension. d. Failure to take prescribed medication. e. All of the above.

7. True or False: Analysis of emergency call data determined that asymptomatic or nonemergent HTN calls were more prevalent than symptomatic calls.

8. Which of the following are risk factors for HTN? (mark all that apply):

a. Age. b. Gender. c. Obesity. d. Race. e. Diabetes. f. Tobacco use. g. Dyslipidemia.

9. True or False: A 2021 study evaluating the effectiveness of emergency training showed that there was no difference between the resident group who received simulation-based medical emergency curriculum and the resident group in a control.

10. True or False: The condition under which the authors’ proposed guidelines recommend that only emergency dental care be provided and a medical consult be obtained before proceeding with dental treatment is when a patient’s systolic BP is 161-180 or their diastolic BP is 100-120 and medical risk factors are present.

Amelia David, BDS, MS; Soh Yeun Kim, DDS; Barnabas Kim, BS; and Hyan Il Kim, BS; and Udochukwu Oyoyo, MPH

abstract

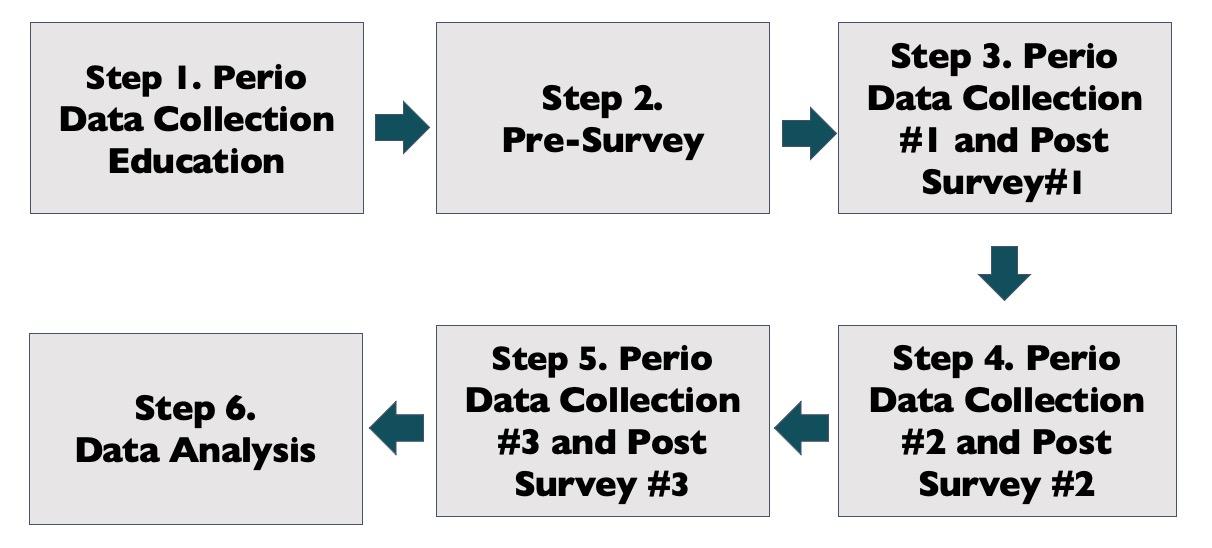

Background: The objective of this study was to compare the time taken for second-year dental students to collect periodontal data and to assess their confidence level in preclinical activities.

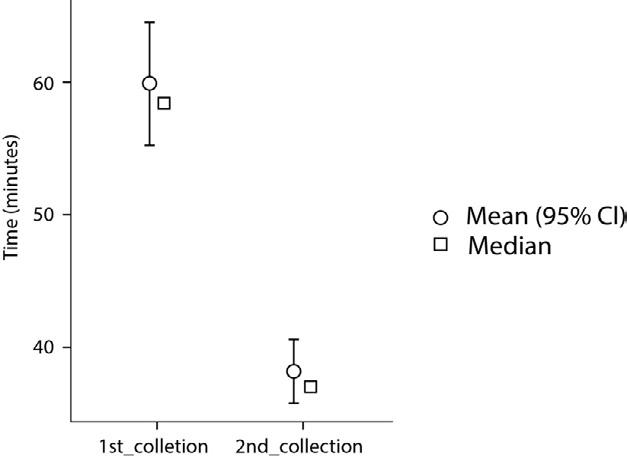

Methods: Second-year dental students at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry (LLUSD) paired up as clinician and patient and participated in three periodontal data collection preclinical activities. A total of 91 sample data were included. The time that students spent on periodontal data collection was recorded. A presurvey and three postsurveys were conducted to evaluate students’ confidence. One sample t-test, the Freidman test, Pairwise comparisons and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for statistical analysis.

Results: One sample t-test result showed that there was statistically significant time improvement between first and second data collection and between second and third data collection (p-values < 0.001). Results for postsurvey 2 with the Kruskal-Wallis test showed collection times were significantly lower among students who reported confidence in collecting data [H(1) = 5.60, p = .018)].

Conclusions: Statistically significant time improvement through periodontal data collection activities were seen. Students’ confidence level and improved data collection time were especially related during the second data collection.

Practical implications: This study signifies that multiple practice sessions in training can be a valuable learning tool to reduce the amount of time that students need to complete the task and increase students’ confidence level.

Keywords: Periodontal data collection, preclinical activity, time improvement, students’ confidence

Amelia David, BDS, MS, is an assistant professor and clinical instructor in the department of periodontics at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Soh Yeun Kim, DDS, is an assistant professor and course director of PatientCentered Care II in the division of general dentistry at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Barnabas Kim, BS, is a fourth-year dental student at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Hyun Il Kim, BS, is a fourth-year dental student at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

Udochukwu Oyoyo, MPH, is an assistant professor and statistician at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported.

The goal of the preclinical dental curriculum at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry (LLUSD) is to ensure students are well-prepared with dental knowledge and skills that will enable them to be competent to practice dentistry effectively and independently in providing patient care. Second-year dental students are trained in preclinical activities that guide their transition from didactic and preclinical settings into direct patient care. Dental students at LLUSD are introduced to periodontics in their first year in a classroom setting and didactic teaching continues in their second year. Preclinical periodontal hands-on practices are emphasized during their second year of dental school along with other preclinical hands-on activities such as patient examination and local anesthesia practice.

Students are paired up and take turns as providers and patients under faculty supervision. Students start actual patient care in the spring quarter of their second year. They perform comprehensive oral evaluations (COEs) and periodic oral evaluations (POEs) under faculty supervision.

In addition to evaluating and assessing their patients for caries and restorative needs, students must be able to evaluate periodontal health by collecting periodontal data during COEs and POEs. Periodontal health is the foundation of overall dental health and also has an impact on patients’ general health.1 Periodontal disease is associated with several medical conditions such as Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pregnancy, chronic renal disease, etc.1 A study showed that treating periodontal disease can increase oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL).1 Therefore, it is imperative to understand a patient’s periodontal condition, determine accurate periodontal diagnoses and provide appropriate

periodontal treatment for patients. It is important to collect accurate periodontal data to make a correct diagnosis. Dental students must master measuring periodontal pocket depths (PD), bleeding on probing (BOP), clinical attachment level (CAL), gingival recession (GR), mobility and furcation involvement.

There is a need for confirmation on whether repetition of preclinical practice can improve students’ confidence and performance in providing patient care. When predoctoral students are introduced to skills they have never encountered before, they are expected to underperform in terms of time management compared to experts. However, the speed and accuracy of data collection is expected to increase after repetition. Wang et al.2 conducted research on the surgical skill and confidence level of medical residents by providing repetitive practice during boot camp.2 At least five hours of skills training was assigned to the residents, and they were required to train at least 30 hours per month.2 They found that repetitive practice is imperative to learning new skills and behavior, and they concluded that repetition improved their confidence levels.2

An integrated review done by Gharibi and Arulappan showed that repeated simulation enhanced self-confidence, critical thinking, knowledge, competence and satisfaction of nursing students.3 Recipients of repetitive simulation reported that their ability to execute certain clinical skills was improved. In addition, they became more active in learning, which was directly linked to increased self-confidence, clinical competence and problem-solving.3 A study from Haleem et al. also showed the importance of repetition in education. Their study recruited a total of 935 adolescents and provided oral health education led by dentists, teachers and peer-leaders.

Regardless of the position of educators, they were able to conclude that repetition and reinforcement can play a vital role in school-based oral health education.4

Patients’ comfort during a dental procedure is also an important part of patient-centered care.5 Research shows that the “level of comfort” a patient perceives during dental care has an impact on the judgment of a dentist’s skill and quality of care.6 A patient’s comfort reflects their trust in the knowledge and experience of the provider. The study also showed that more experienced dentists have higher patient satisfaction levels compared to recent dental graduates, which is associated with their greater skill and speed.6 Another study showed that patients appreciate speed, experience and a feeling of ease and comfort when procedures are performed in a timely manner.7 Therefore, through repetitive practices, perceived patient comfort is expected to improve as the provider’s confidence level and speed in performing periodontal data collection increases.

There were few studies in the literature regarding students’ performance and measuring time on periodontal data collection. One study in Japan assessed the time needed to measure periodontal probing on a typodont among dental professionals and dental students.8 The study showed that probing time was much longer in the students’ group when it was compared to the dental professional group,

but the probing time decreased as they repeated the practice on the model.8

The objective of this study was to compare the time taken for novice second-year dental students to collect periodontal data and to assess their self-confidence levels through repeated practice of periodontal data collection during preclinical hands-on sessions. In a survey, student clinicians were also asked which component of the periodontal data collection was the most difficult or challenging to measure.

We hypothesized that repetitive practice of preclinical data collection will lead to second-year dental students being more efficient with periodontal examinations, thus leading to decreased time and increased confidence.

The study protocol was reviewed by the Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the study is exempt from IRB (IRB# 5210456).

A total of 91 dental students from the DDS class of 2024 participated in three periodontal data collection activities (eight dental hygiene graduate dental students were excluded). These 91 students did not have prior periodontal data collection experience.

All students received didactic training on periodontal data collection that included lectures and instructional videos on measuring or determining