20232024

1

UNC-Chapel

CELLAR DOOR 2023-2024 |

Hill

MISSION

Cellar Door is the oldest undergraduate literary journal at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The magazine has continually published the best poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and art of the undergraduate student body since 1973. It welcomes submissions from all currently enrolled undergraduate students at UNC.

THANK YOU

To the Creative Writing Program and Department of English and Comparative Literature, for their ongoing support of student writers, editors, and readers.

To Bland Simpson, for his benevolent support of Cellar Door and other undergraduate literary causes.

To Michael McFee for his decades of dedication to Cellar Door, including distribution of copies to the campus racks, and storage of boxes in his office.

To the artists and writers who create every day, for letting us share their work with the rest of campus, and beyond.

v

©

Cover

Calli Westra

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Reader,

This year we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Cellar Door and the retirement of our long-time adviser, Professor Michael McFee. As we approach these milestones, I offer my thanks—to Professor McFee for his support in all my creative and academic endeavors since that first day of Honors Intro to Poetry Writing over Zoom my freshman year; and to Cellar Door’s editors and staff, for helping my vision of what the magazine could be come to fruition over the last two years. Boatemaa, Lucy, Jane, Anistyn, Fiona, Isabella, Carly, Luna, Meredith, Hope, and Georgia—Cellar Door would not be what it is without your advice, ideas, leadership, creative excellence, and hardwork. I’m grateful.

As I think of these achievements and my own graduation in May, I’m drawn to the art contained in these pages, the co-existence of simple experience and intense emotion in the everyday. We love and grieve and go to class and get coffee with friends and apply for jobs, and the mundane and the momentous both become part of our stories.

The visual art, poetry, nonfiction, and fiction in this edition of Cellar Door draw out the viscerality of these stories—the emotional tension layered over the passing of time—and show that nothing is inconsequential, that humanity is built on daily experiences pushing and pulling against each other in the volatile current of existence.

Even though we can only accept a select number of pieces each year for the magazine, I’m grateful to all the artists who submitted for being part of my experience this year, for helping me recognize the beauty of time’s liminality, and the changes and growth it brings.

And finally, to our contributors: Thank you for reminding us that life makes up art, and that everything matters to our stories, no matter what medium we tell it in.

Best,

Abigail Welch

Editor-in-Chief

Abigail Welch

Editor-in-Chief

3

ART

FIRST PLACE

SECOND PLACE

AWARDS

Untitled

TIMOTHY ANDERSON

Mr. Versailles (part 1 and 2)

QIAOAN “JOSEPH” GU

THIRD PLACE Under the Skin

MARIELA SOLORZANO

FICTION

FIRST PLACE

Nothing is Burning

ZOE WYNNS

SECOND PLACE 10 Acres

SYDNEY BRAINARD

THIRD PLACE

Intertwined with Mourning

CAMPBELL WARREN

NONFICTION

FIRST PLACE

SECOND PLACE

THIRD PLACE

POETRY

FIRST PLACE

SECOND PLACE

THIRD PLACE

We Don’t Know if There Were Three Wise Men

KATHRYN BRAGG

Hold Your Head Up

EMERALD IZUAKOR

When the Ocean Seeks Us Out

ALEXIS CLIFTON

Roadside Pieta

BENI KROLL

There was a sketch of two men holding hands,

KIERAN MURPHY

I Only Manifest Things When Chappell Roan Comes on the Radio

NAOMI OVRUTSKY

4

JUDGES

ART

Jason Lord is an interdisciplinary artist and educator working in assemblage, installation, video, drawing, sound, and anything else that can be used to tell a story or illuminate an idea. After over two decades of making art and teaching middle school in Durham, he graduated with a BFA from UNC-CH in 2022 and is in the last semester of the MFA program at UNC-Greensboro. His work can be found around the Triangle, including at Peel Gallery nearby.

FICTION

Travis Mulhauser was born and raised in Northern Michigan. He has two novels forthcoming from Grand Central/Hatchette beginning in Winter ‘25. His novel, Sweetgirl (Ecco/Harper Collins), was long-listed for The Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, was a Michigan Notable Book Award winner, an Indie Next Pick, and named one of Ploughshares Best Books of the New Year.

Travis is also the author of Greetings from Cutler County: A Novella and Stories, and received his MFA in Fiction from UNC-Greensboro. He lives currently in Durham, North Carolina with his wife, two kids, and dog.

NONFICTION

Allyn Aglaïa is a writer, curator, and artist in Paris. Publications include The New Yorker, The New York Times, Guernica, The Atlantic, Longreads, The Atavists, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and others. https://www.allynaglaia.com/.

POETRY

Fred L. Joiner is a poet and curator based in Carrboro, NC, where he served as Poet Laureate from 2019-2022. Joiner has presented his work nationally and internationally. He was a recipient of a 2019 Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellowship. His new collection, Mirror in Our Music, is forthcoming in 2024 by Birds LLC.

5

iii

STAFF

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

ABIGAIL WELCH

ASSISTANT EDITOR

BOATEMAA AGYEMAN-MENSAH

ART EDITOR

HOPE MUTTER

FICTION EDITOR

GEORGIA CHAPMAN

PUBLICITY EDITORS

FIONA HUANG

ANISTYN GRANT

NONFICTION EDITOR

MEREDITH WHITLEY

POETRY EDITOR

LUNA HOU

TREASURER

CARLY BARELLO

WEBSITE EDITOR

ISABELLA REILLY

DESIGN EDITORS

JANE DURDEN

LUCY SMITHWICK

STAFF

ART STAFF FICTION STAFF

MADI SPEYER

GEORGIA PHILLIPS

ISA GAMEZ

ALI HUFFSTETLER

JAQUELINE ARI

CHARLOTTE BRECKENRIDGE

LIZZIE HERRING

LILY TOTHEROW

DANEEN KHAN

LAUREN GUILLEMETTE

NONFICTION STAFF

CIARA RENAUD

JESSICA HOFFMAN

ANNA MARIE SWITZER

MACON PORTERFIELD

ASHLEY MCGUIRE

DONNIE WILKIE

HANNAH BERHANE

ISABEL KAKACEK

LIZ WOLFE

AMIE COOKE

NEHA JONNALAGEDDA

DELANEY PHELPS

RYAN PHILLIPS

RIO JANISCH

XENIA WEAKLY

NA’DAYAH PUGH

SHERIDAN BARRY

BROOKE XU

LIZ VAUGHAN

CADE RODRIGUEZ

POETRY STAFF

EMMA KAPLON

AMELIA LOEFFLER

VIVIAN WORKMAN

BRADLEY SADOWSKY

ALEXANDRA DIRKS

ALEXANDER GAST

OLIVIA THOMAS

ODDESCIEY RONE

AYDEN MASSEY

PUBLICITY STAFF ADVISERS

ASHLEY DANIEL

MARY MCKEE

ELIZABETH JORDAN

MICHAEL MCFEE

MELISSA FALIVENO

7

8 TABLE OF CONTENTS vi Untie, unwind, my filthy spine 15 Jane Pierce Untitled 18 Timothy Anderson Shattered Accolades 22 Rachel Landi Womanhood 26 Calli Westra Mr. Versailles 1 33 Qiaoan “Joseph” Gu Mr. Versailles 2 34 Qiaoan “Joseph” Gu Under the Skin 35 Mariela Solorzano Starry Eyed 36 Mariela Solorzano Jude 40 Marcella Kingman CMY Collab 47 Jesse Patete Emaciated 51 MB Connolley Untitled 54 Qiaoan “Joseph” Gu Thomas 55 Marcella Kingman ART FICTION Intertwined with Mourning 25 Campbell Warren Nothing is Burning 27 Zoe Wynns Chicken and Dumplings 49 Caroline Parker 10 Acres 56 Sydney Brainard

9

When the Ocean Seeks Us Out 10 Alexis Clifton Hold Your Head Up 19 Emerald Izuakor We Don’t Know if There Were Three Wise Men 37 Kathryn Bragg On Gluttony 43 Patrick Hunter POETRY Bad Date 16 Kieran Murphy There was a sketch of two men holding hands, 17 Kieran Murphy Love Poem with a Pegasus 21 Luisa Peñaflor I Only Manifest Things When Chappel Roan Comes on the Radio 23 Naomi Ovrutsky Unrequited Love as Special Topics Seminar 41 Naomi Ovrutsky On Boobs 42 Alice McCracken Knight Top Down Processing 48 Sophia Vona Spokes 52 Brooke Elliott Roadside Pieta 58 Beni Kroll After the crash I dreamt you were innocent 59 Beni Kroll

NONFICTION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

WHEN THE OCEAN SEEKS US OUT

Yesterday a cop stopped me in a grocery store.

“Eres demasiado joven para estar aquí,” she quipped.

I probably could’ve passed for an adult if I had tried, but even I knew that minors couldn’t be in grocery stores in Mexico. Too much wine, too much of everything. Thank God she didn’t take my bag; if she had it would’ve been a waste of pesos, and money was scarce for me. I had only a few left in my pocket, which I’d planned to spend on a new book to read since I’d read all the books in the house. I hadn’t worked in months—my past fervor that had once burned so viciously had abandoned me, leaving behind a body that felt like death warmed up.

Leaving the tienda, the world turned into bright colors and people yelling, providing no relief for the achy feeling that singed my chest. There was an advent or a mural on every wall, each piece of landscape alive with living bodies and sounds and smells. I snaked my way through busy crowds of street vendors, children, and stray dogs, holding my cargo close to my chest. A man stopped me, taking hold of one of my wrists with a single strong hand. I turned, and he was shouting something—something about the end times, the rising heat of the Earth and ocean swallowing humanity whole like a snake. I broke myself free of him, saying over and over again “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” taking the weight of these words like I had caused the ocean to rise, the days to be scorching, and God’s rejection. He was one of those Evangelists who wasn’t sure what they wanted, claiming we must seek forgiveness! Only to remind you that forgiveness gained you nothing, and that on your own there was no hope, and that judgment would seek you out like a hound. What a way to live, I thought. So much passion, and for a God who allowed the Earth to die? The people to suffer? I had found my life easier with rejection to those righteous ideas.

After a short struggle, I hopped into our rental car where the adults, Manuel and Ana, were waiting for me. Ana was my eldest sister, Manuel being her longtime boyfriend. To me, he was the older brother I never had. Despite the holdup, I still carried two bottles of rum, and knowing the ride would be rough I stuck them between my legs on the car floor. Marc Anthony was on the radio; “♪A veces llega la lluvia, Para limpiar las heridas ♪.” The windows of the car were cracked open and the

10 ALEXIS CLIFTON

smell of the summer seaweed seeped through; once you live in this part of Mexico long enough you begin to smell the same way, and it sticks to your hair, your skin, and hardly washes out of clothes. The smell lingers no matter where you go. The same way death has a scent. Or blood, like melted copper on irritated gums.

My mind snapped when we hit a pothole in the road, there was a honk and someone yelling vamos in the next lane over. We were at an intersection, and it seemed that no one on the road was very happy about being there. It was a Monday evening around 5 p.m., so everyone was in a rush to go home and do just as much work as they did for the last eight hours. The two up front bickered in half-Spanish about what was happening for dinner that night while I fidgeted with Manuel’s hand, which he’d stretched behind the seat to me. He knew I was anxious, and so did Ana. They’d tagged me along to a club the other night in Tulum after I’d begged them not to leave me at home, and in short words, I didn’t enjoy myself. The noise that shook every bone, the lingering smells that made my head ache. These days I was having a harder time than others. I thought about the Evangelist—if the world was ending, I wondered, would I be okay with it? I remembered the Sunday school lessons of what felt like another life; I remembered being baptized. Does God remember those who have forgotten?

I thought about the Evangelist—if the world was ending, I wondered, would I be okay with it? ”

“

I watched the world from the comfort of my leather car seat, spotting a girl on the trash-covered median. Her face was painted and she wore traditional Mexican clothing. In her hands was a bucket that looked like it was meant to make sand castles. Something in her face was melancholic, I could feel it. The hopelessness.

She was just like me.

“Give her something, won’t you?” Ana suggested from the passenger seat.

I was already ahead of her. I reached my small sum of cash through the window and dropped it in her bucket; it was only a few pesos. It was all I had on me. Her eyes moved up to mine, and she seemed to force her face to smile. The ache that I’d

11 ALEXIS CLIFTON

festered dissipated for a moment.

“Gracias, linda.”

I only nodded, and before I knew it we were moving again.

The sky that evening looked like rain as the clouds sat like a blanket over the streets of Cozumel. I’d always loved the rain, but at that moment I almost dreaded the depressed feeling that would seep out from the street grates. After a half hour, we’d reached the house we were staying at. Ana’s father, a Nicaraguan businessman, knew a guy. Said guy managed to give us a house on the water for cheaper than he would a non-Spanish speaking group. We would only be there for around a month. The rest of my family was staying in Tulum; I couldn’t bear to be with them. Not after what had happened. I would’ve preferred to be swallowed by the vast sea, as the man had said.

Admittedly it was a fairly nice home considering the area. The tiled floor of the house was slightly misted by the humid breeze that came through the blinds. AC was too expensive where we lived, so we opted for the salty wind. The living room was filled with rattan furniture and Moroccan-style pillows. Along the stucco walls were paintings depicting a lot of differently-styled images. I could tell most of them were counterfeit. I carried the rum to la cocina, placing them with a clink onto the pseudo granite countertop beside the coconut I’d saved for myself. I was starving. Taking the coconut, I reached for the knife block, Manuel’s hand stopping me halfway there.

“No. I’ll get the coconut for you,” He spoke sternly, taking the coconut from my arm simultaneously. I tried to seem annoyed the best I could, but I wasn’t good at showing emotion. He still didn’t trust me.

“Manuel. Te dije que podías confiar en mí,” I whined, watching him cut a hole from the skin of the coconut. He only shook his head.

“You know I do this to protect you. Your sister agrees with me, and you know that.” He made himself clear as he drained the water from the shell, remembering my distaste for the liquid. I glanced with a sense of defeat over at the knife block. I didn’t want to acknowledge that he was right. Ana hadn’t heard the conversation, but I knew that if she’d been there she would’ve taken Manuel’s side.

“You Dominican men are always stubborn,” I scoffed as I tried to make light. Manuel, being the usually lighthearted person he was, chuckled just slightly as he handed me the plate of coconut meat. I knew he was worried about me, and I hated it. Still, I thanked him as he scruffed the top of my head. He was someone that was easier for me to exist around.

12 ALEXIS CLIFTON

With the flimsy white plate in both hands, I carried myself out the screen doors and onto the porch, seating myself on the ground with my legs crossed.

The ocean was the same pale color as above it, the orange seaweed washing up in wadded, smelly clumps, the scent combining with the earthy tone of the greenery. The air hung calmer here; I could take a full breath. At any minute the rain would fall, I could see it in the sway of the palm trees. Through the upstairs window, I could hear Ana getting ready for a night out to the sound of Bad Bunny, and Manuel speaking in rapid Spanish to someone on the phone. Then there was the sound of the ocean. So consistent, so predictable. The palms sang their own song and the wind in my ears had its own voice. There was the occasional pop of what sounded like gunfire. It was a solid, full noise, almost too much. The heavy chorus was filling up every corner, every atom, every thought. I could hardly think as my mind was cleaned out, leaving only the shell of my skull. There was a phantom pain along every inch of my skin as what was left of my inner turmoil melted down and pooled at my feet, making me shiver. In the salty heat of the summer, I suddenly felt cool.

“De verdad quieres morir?” The question echoed in my mind.

Do you really want to die?

It was a familiar question, a scary one. I could solve any question and yet this one always troubled me. But maybe, just maybe, this time I had an answer. The waves crashed again, claiming the beach as their own. None of what was around me was mine, but for whatever reason, I felt connected. Something had clicked. For the first time in seventeen years, I could feel my soul inside of my body. I was a vessel in the ocean and the storm was calming, leaving only the small touch of the rain. In the back of my head, there was the sharp clang of a knife dropping, someone crying, maybe even screaming. I think it was my own voice and to this day I’m still not sure, but it didn’t phase me. The scars—the memories. They were still there, but now they felt different.

I felt the first drop of rain on my cheek.

The second was my own.

Rising back up to my feet, I made my way down to the shoreline, where the seaweed piled in clumps that seemed never ending. The water felt cool as it rushed by, the floating debris of shells and rocks pushed and shoved, back and forth, in a waltz that remained in spite of everything. If God was out there, I thought, then God is the ocean. I remembered hearing somewhere that the water has heard everything, seen everything—that the water carries history the way it lifts surfers

13 ALEXIS CLIFTON

up with ease. The rage of the rising levels, the churning waters, the salt that finds every paper-cut—that is our judgment. I waddled out further, until the water hit my knees and soaked the edges of my shorts. I began to shiver, wrapping my arms tightly around myself as the seaweed wrapped around my ankles like clammy hands, wanting to yank me forward, pull me in, as if to enter Dante’s Inferno. To be swallowed by the ocean would be fine, I thought. Allow the waves their revenge, their revelations, and their anger.

The Sunday school teachers would always reference Hell and point down, like it is a place just beneath the tile floors. They forget the dark expanse that comes before, the place we fear the way a priest fears God. With reverence, with love, with a constant unease. When the ocean will seek her judgment, and we will be pulled in, finally, by the hands she sends creeping forward, taking over everything as she rises. The ocean could take me between her cool arms, see all that is rotted and undone, and with her salted tears, cleanse me and take me under.

Beyond the blue surface, where there is all that is unknown.

14 ALEXIS CLIFTON

Untie, unwind, my filthy spine

Drypoint with Monotyping, 1000x1294px, individual pieces are 12x18 in

15 JANE PIERCE

BAD DATE

the too-small swingset barely manages to lift either of us up into the night air. somehow you glimmer, pale pink parka and itchy green mittens, smell of winter’s snot speckled throughout, slow-motion flipbook against the thin white ground and frigid sky-darkness. and me, I try to spin around, yank the packed ice chains to do some trick or little game, but I’ve lost my touch.

we try to slow down to kiss, chew the dreary scenery, but your hair gets stuck in your mouth and nearly freezes and my nose is about to fall off. so we sit, frozen in place, and lock hands, staring into the silhouetted treeline. nothing comes forth—or ever will—but for one long moment we’re stuck together, the snowy silence a question, our stillness an answer.

16 KIERAN MURPHY

THERE WAS A SKETCH OF TWO MEN HOLDING HANDS,

hardly more than stick figures on the fresh-dried mud by the Haw’s beds of leaves, reeds and sedge, fast-faded strands of lightning hair on one and none on the other. their faces were gone, their limbs reduced to murk, but a message endured, “Johnny + Caleb,” with half a lingering heart around it. what compelled them to etch their names on soft ground—with, presumably, a branch from one of the many eligible trees— in the path of near-certain ruin? it’s as if they said,

“bring it on,” as if their love was that sure, unafraid of mindless steps, the inevitable erasure by nature’s hand.

I hope it’s still there today, despite the rain, the litter, the cigarette butts and runoff dog piss. I hope their invisible smiles are wide as a river, hands firm as bedrock.

17 KIERAN MURPHY

18 TIMOTHY ANDERSON

Untitled Inkjet print, 8.5” x 11”

HOLD YOUR HEAD UP

She washes your worries and cares away, the air redolent of peppermint, tea tree and sorbet. A medley of shampoos dance on the scalp, invigorated by her scratching fingernails. When cool water washes the foam away, a fizzing tingle stimulates the senses. It’s not too bad, yet.

Under that steaming contraption, you try to read a novel without wetting the pages, but rogue droplets find a way. Feeling uncomfortably drowsy, you shift slightly to maintain consciousness when suddenly, a hot drop of water slips off a strand like a firebrand and scalds your neck, reminding you that beauty, or at least decency, requires pain.

¡El que quiere moño lindo aguanta jalones! You’ve aguantado jalones virtually everywhere. Between your mother’s firm thighs, those Dominican blowout shops, the natural Black hair salons, na obodo gi, your village. Including by your own hand, when you’ve vainly struggled to tame the palaver. They’ve advised you “Why carry on with this dis your hair? It would just be bettah if you did your hair mallam. Mallam? Low cut. The voice in your head contemptuously replies, “Eh, dis your fada, he does not ondastand. You know, he’s a man, so automatically, he no fit get am.” You’re criticized for having your hair in its organic state, even na obodo gi, where your hair was born.“See dis one who wants to do guy with weave on!” an unsupervised boy declares in passing like a seasoned town crier. There is an element of impatience in his voice as he charges his wheelbarrow down the dusty red earth, scoffing at your audacity for engaging in what he sees as frivolity. Sitting in that sweltering shop, you might say, “He’s a man, so automatically, he does not ondastand,” but how fair is that? Nigeria has largely abandoned the traditional “bush” styles of her past.

“It feels like my head’s on fire!” The potency of camphor and menthol spiked shea blinds you, as you twist and turn with the blow drier. Why, you’re not even ill, but Vicks Vapor Rub seems to think differently. It fixes everything. You little girl, want to give up hope. You, little girl, are letting yourself be manipulated any which way. Hold your head up. You hope there’ll be a sense of mutual understanding and that she’ll yield, if only for a moment.

“Your head’s on fire?” she repeats absentmindedly, continuing to run a lion’s roar

19 EMERALD IZUAKOR

through your hair. Girlll… Not quite the understanding you were looking for.

During a brief repose, she sweeps up your hair’s scruffy, shedded bits from the linoleum while you run fingers through your cascading waves. “Oh, couldn’t I just leave it like this,” you think longingly, admiring the length and the flounce of your tresses. On the rare occasions when your coiffure was straight, the girls on the playground would say “I like it better like that.” Why don’t you leave it out more?” But you knew better than them and your desires. “Well, I can’t do that because it’s not good for my hair,” you declared proudly. You eye your somewhat confused and homogenous friends, who arch their eyebrows dubiously. That’s right, your hair is special.

When you were younger, you would shriek incessantly, bordering on hysteria. Albeit your current age, you still flinch when the merciless comb snags and wince when her knuckles maneuver your noggin. Proudly tender-headed for evermore. You do a double take when she says “Hold your head down” or “Hold your head over” as you’re so habituated to the usual “Hold your head up.” Still you can’t help but marvel at her deft hands, nimbly weaving your now pressed mane. You can hear the flicking and swishing of the individual strands. They whisper in your ear for a fleeting moment before joining their sister plaits. She showers you with a sweetsmelling spritz of almonds and angels. Hold your head up, baby. There is an element of artistry in this, an artistry that humbly and diligently beautifies others. It hurts, but you’ll endure it. How does she manage to manipulate classified unruliness into such tamed beauty? It must be a secret. Hair holds secrets.

20 EMERALD IZUAKOR

LOVE POEM WITH A PEGASUS

I think of kissing her the way those monkeys slip into hot springs in the winter. I think of kissing her in a bright room, I think of kissing her without pauses, I think of kissing her with gloves on, I think of her taking them off, I think of her long fingernails the same way I think of feathers on the hooves of pegasi. In hot rooms of dancers I think of kissing her, sitting the toilet, washing my ears, which I almost never do, but when I do

I think of kissing her. I’ve tried to hibernate it. I’ve tried to eat it up, the urge. I’ve tried to stuff it with honey and figs, make it write, I’ve tried to skin it, I’ve tried to wash its feet, let it complain, I’ve tried to waterlog it so the pages swell and fold together, I’ve tried to bore it to sleep, read it tax manuals, massage it, make it tea, pick the leaves, I’ve tried to peel it, choke it with cinnamon, tease it, make it race against horses, whip its flank, get on a pegasus with it, fly into a glitter cloud together—from here I can see all the trees without leaves, I think of kissing her over a fire, in this winter that could freeze our organs into polar guts, I mean a real cold, glacial, the type that bears blue icebergs, I think of kissing her on the ice, slipping into one another, laughing, of course, kissing each other on the back of a pegasus not in awe of the kissing but of the way the wings sound like whistles, the kissing so familiar I do not think of kissing her at all.

21 LUISA PEÑAFLOR

8.5” by 11”

22

LANDI

RACHEL

Shattered Accolades

I ONLY MANIFEST THINGS WHEN CHAPPELL ROAN COMES ON THE RADIO

But what is manifestation, if you really think about it?

Is it not just praying to a vast, nonexistent god, something lurking in the ether?

Am I just godliness in the form of a girl, with cheekbones waning like a November crescent?

Godliness coming from a girl who has never believed in a god to begin with.

There are two or three things I do believe in:

1) Your hands on my face

2) Pop music as reincarnation

3) The joy of being alive on a Monday night, dancing through a sea of screaming girls holding onto one another.

I return exhausted, tumbling in like a great wave all the way to your front door, with a milkshake from the corner drive thru and glitter on my face. I am simply passing through, your drunken savior in the night. Like a comet on my twenty-year return, all I really want is to be admired, to inspire awe for half a second. I leave a footprint on the front porch. I steal a grape or two from the fruit bowl. I scrawl my social security number in lipstick across your bathroom mirror.

Even though I will always have my mother’s freckles and her sharp collarbone, I am not as talented in the art of regret or indecision. When I want something, I become terrifying. Like a black hole of a girl, everything around me turns to spaghetti upon contact.

Some will say I birthed myself from stellar dust and gas and body glitter and acrylic nails and gummy vitamins. But no one really knows for sure. There is no easy answer, and to start in one place means to end in multiple.

23 NAOMI OVRUTSKY

Is there a god? One could say so. I linger on in the drunk conversations through the bathroom stall, the party lights across the ceiling, a little happy and a little sedated. They are chanting words I cannot make out. I am shaking ass and taking names where it really matters.

My mother asks me about boys, and I tell her I am too busy creating solar systems. I say, Saturn’s a little wobbly, she needs some adjustment or a really good pep talk. Pluto needs a better head start (our local lesbian, exiled from the popular universe). Uranus is just Uranus.

My mother does not understand. I tell her to send her inquiries my way, and in the next lifetime I will get to them. Somewhere along the way, one of us will get it right. In the meantime, I am singing off-key and driving badly. I am fixing my reflection, reapplying my lipstick in the rearview. I am tweaking all the edges and filling in the lines. I am wide awake at dusk and asleep in the afternoon. I am inhaling salt water and breathing out pure crystal. I am walking for miles, the moon at my back. The universe is shifting. The bar is still alive, and it waits for me. The beat is seductive. The beat is infectious. The girls are in love. The speakers are shaking. The heartbeats are loud as motor engines. My friends are here. My friends are on stage. My friends are in drag. My friends are in love. My friends and I are alive. And there is a god.

24

OVRUTSKY

NAOMI

INTERTWINED WITH MOURNING

Crafted four centuries ago by a madman artist, with the marble now stained and the fingernails chipped, the statue remains intact—a man and a woman, entangled, in love, with faces carved in grief. Under the perfect silence of the sleeping city, the bodies untangle. The man stands tall, stretching his arms into the air, cracking his back. He appears almost blue under the pale moonlight. He reaches out and touches the face of his lover. She closes her eyes and leans her head against his palm. They stand there quietly for a long time. They cannot speak but there isn’t anything to say anyways.

The lovers walk the alleys, touching the walls to reaffirm that they are alive and that this is real, not one of their many daydreams. They pet the flowers who coo beneath their touch. The cobblestone dances under their steps, sending ripples across the square. A string of lights turns on as they pass beneath it, and, inside a cafe, a piano plays its own rhythm. The man reaches out his hand for the woman to take. They dance in the street as the chairs rearrange themselves and the spiders build webs to be taken down in the morning. Knick knacks jingle in shop windows, creating a symphony for the statues to dance to. The fountain sprays water into the air and the woman leans her head back, letting it run over her stone hair.

In return for the show, the man and the woman clean the streets—picking up trash, wiping graffiti from the sides of the buildings. The woman runs her hand across the flower boxes and store fronts, who feel the love of a mother in her touch. The first rays of sun glisten off the top of the buildings, illuminating the laundry which watched the couple dance, moments ago. The man pulls on the arm of the woman. She looks at him with pain in her eyes. A plea to stay out just a moment longer, though she knows it is not possible. The people will rise with the sun.

The statues climb back on the podium. The man grabs his lover and the face of grief she assumes is not a performance. She takes one last look at the city square and a tear rolls down her cheek as they become entranced again, not able to move until the next night, when the last of the town slips into a dream.

25 CAMPBELL WARREN

26 CALLI WESTRA

Womanhood Film Photography, 1200px/393KB

NOTHING IS BURNING

You’re watching a thriller with Avi when the smoke alarm goes off. She’s pissed, grabs the remote, squints up at the thing ringing like it’ll point her to the culprit. “If she’s letting Adam smoke inside again, I swear to god,” she says, and you’re good at reading lips so you catch it all, but you probably wouldn’t have otherwise because this shit is loud. Someone comes thumping down the stairs, probably Mia, you don’t think any of the others’ footfall is this heavy. You don’t get a chance to look over and check, though, because that’s when you see the fire.

-

Avi’s paused the movie three times in the last thirty minutes. The first time was to dump all the information she’d learned in film class about it. “Did you know,” she says, then pauses, gets distracted with a cold drink someone has left on the coffee table. A small, shining ring of water. She grimaces, maybe involuntarily, tries to wipe it off with her hoodie sleeve. Doesn’t work. “Did you know,” she tries again, “that Psycho is widely regarded to be the first movie where the protagonist dies before the end?” She laughs a little. “Can you imagine all those poor people, back in the ‘60’s, thinking at least she’s safe. Then, out of nowhere. The shower scene.” Shakes her head. “God, I wish I could see it again for the first time.”

-

Jen’s already asleep when the fire alarm goes off, and she sleeps like a rock. You love her, but you’ve forgotten she exists. Avi follows your line of sight, sees what’s burning. Jumps up. The flames are small right now, just like children, giggling, seeing what they can get away with. “Fuck,” Avi says, still standing in place. “Where’s our– do we– do we have a fire extinguisher?” Of course you don’t. You’re four college kids shoved into a rental house half a mile from campus, who barely remembered to bring their own shoes. You remember reading something about fires, how fast things burn. A house can be engulfed in as little as five minutes, you’d read. It had maybe been sixty seconds, you do the math in your head, what is that? Four more to go? Sounds right. The floor has begun to burn.

-

The second time she pauses the movie, she doesn’t explain why, just hops up and heads into the kitchen. You think about asking what she’s doing, but think better of it. “So,” she calls from the kitchen, “did you talk to Jen yet?” You hadn’t, but you didn’t want to tell her that, let her down. You tell her yes. “What did she say?” You

27 ZOE WYNNS

think about what you expect she’ll say, when you tell her. She’ll look at you with those green eyes and mouth slightly open. She’ll stammer, try to land on the right words. She’ll tell you that she has to think about it, but then she’ll come back two days later and tell you that you’re better off as friends, and you should stay that way. How else would it go? You smile at Avi, a little. What do you think, you ask her. Avi says she thinks you’re a liar. You grin. Unpause the movie without her. She comes running in with her mug of tea, flipping you off, laughing.

-

The curtains burn next, even though they’re all the way across the room. That’s funny, you think. You remember how happy Mia was when she bought those. Spruce up the house, she said. Little dainty lace things, with flowers. You didn’t know what light they were blocking, really, but she was happy, so you were happy. Fuck. Was Mia here? Who was coming down the stairs before? Avi is taking a massive watering can and trying to fill it up and toss water on the stove, but it’s just not enough. “Go get the others,” she says, panting. Smoke is filling the room. Will there be a room to return to when you come back down the stairs? Does it matter? You race up.

-

When you met Jen, it was like something out of a rom-com, slamming into each other in front of the library. “Oh my– fuck, I’m sorry,” you say, awkwardly, what could you say to save it? She’d dropped her paper cup full of some indiscernible brown carbonated liquid. You look at it. Know it’s Diet Dr. Pepper, because that’s your favorite too, and maybe you saw in her a little bit of rage, a little bit of sleep, a little bit of everything that would make you need caffeine and fake sugar at 9 a.m. on a Tuesday. “Oh my god, your hair is so pretty,” she says, reaching down for the now-useless cup trying to roll away. You thank her, not stammering because that’s cliche and she’s waiting for you to say something back. You want to compliment her eyes but that’s weird so you tell her that her outfit is cute. That’s what girls do. Can’t leave it open ended. The other day you’d had a girl tell you she liked your shoes and as your eyes passed over her you couldn’t think of a single thing to compliment back so you thanked her and went on with your day but both of you were missing something. “Hey, aren’t you in that massive World History class with me? I think I saw you sitting at the back,” Jen says.

-

You take the stairs two at a time. You think about going for three, but you know you’ll just fall. The smoke is thick now, white and milky, as it rises. “Stop,

28 ZOE WYNNS

drop and roll” hurls itself into your mind, and you can only do just about one of those right now, so you drop and start crawling. The carpet is cool, and you want to grab handfuls of it and pull it out like summer grass and rub it against your face so maybe it will slow the burn. It’s bad up here, and inhalation is more of a chore. You think about how long you could go without breathing. As a child, you always won in breath-holding contests. All you’d need to do was sink down below the surface and think of something horrible. Something so grotesque, so sad, so terrifying, that you couldn’t rip your mind away. That the fear was worse than the itching in your throat, the tightness in your chest. You think maybe if you can get Jen and get out in five more breaths, you might be okay.

-

It’s mid-November when you realize you love her. You’d sat together in that history class for the last two months, and instead of paying attention you’d watch her play 2048 in her web browser. Jen plays faster than anyone you’d ever seen, at the speed of light, getting up to 1024 within thirty seconds of starting. She asks if you want to try, towards the end of every class, and you cross your arms in fake anger while she shoves you and insists she was being sincere. Even though both of you knew you’d fail before the 200 mark. After class, you sit at the same table, overlooking the campus garden, and neither of you smoke, not really, but somehow at least one of you always seems to have a spare cigarette, a light. And the other one holds out their hand.

-

The third time she pauses the movie, she stands up quickly, pacing around the coffee table Mia found for $15 at Goodwill, almost running into the corner as she makes her sharp turns. “Okay, you’re going to say no. I would say no.” She jostles the repurposed barstool that now works as a holder for a giant plant. Jen likes to think she’s a good plant owner– has them placed strategically around the house to make it look as much as possible like a jungle. Which you don’t see the appeal of, but you’ve never said a word. Even when each plant slowly started dying, one by one, during the fourth week of classes, you never caught on that you knew Jen was replacing them as they died, stealthily, slipping in the back door with dirty hands and a brand-new Philodendron. “But listen,” Avi says. “I don’t see you this happy around anyone else.” You tell her that doesn’t mean anything. Avi glares at you a little. Then her face dissolves into laughter. “I guess. I would just want her to know, if I were you.” -

29 ZOE WYNNS

Avi realizes you love Jen before you do. It’s a couple weeks before Halloween, and you and your roommates are at Dollar Tree, picking out decor and talking shit. Mia peers out from the end of the next aisle, only her head and shoulders visible as she looks at the three of you. “It’s not that I don’t love him. It’s just…” “...that you don’t love him,” finishes Jen. She looks over her shoulder, grinning at you from in front of the white porcelain ghosts. Avi’s hunched over staring at fabric bats with legs that look like they’re made of pipe cleaners. Silent, which is unusual. “I think the way you know,” Jen says, grabbing one of the ghosts and inspecting its little feet, the chip on its head, “REALLY know you’re in love, is—” But you don’t hear her. You’ll never know what she said, because Avi meets your gaze, horribly-manufactured bat in her left hand and her right hand half-open, raised, as if reaching out to catch something only visible to her wide, dark eyes. Trapped, for a moment. Then, “Yeah, I don’t think I feel all that about Adam. But that’s a little excessive, don’t you think?” Mia calls, returning to the candy aisle, rustling through what you’re sure is their various candy corn selections, of which she once ate a whole bag while high.

“I don’t think I could feel that way about anyone,” Jen says, putting the ghost down with a slight clink. You look anywhere but at her, while Avi searches your face for something she already knows.

Fire is swimming through the threads of carpet, on the stairs now, not here yet, not here.

“

Breath one. Through blurred eyes you see that white door that’s caught your knocking hands almost every day, except the ones where you need her the most, and go straight to the doorknob and push through. Think of the horrible things. Think of Psycho. Think of the blood, think of the water. Breath two. Think of never seeing her again. Think of your hands right now, on the pitchfork, on the summer grass, on her fingertips, on the flames. Crawl another inch forward, like Jen had to do one night when she was so drunk she’d forgotten how to walk, and none of you could breathe for laughing so hard. The air was so free, so easy to capture back then,

30 ZOE WYNNS

-

”

and yet it was never enough. Breath three. Shit, something to open the doorknob with, it’ll be hot. Fire is swimming through the threads of carpet, on the stairs now, not here yet, not here. You pull your shirt off over your head, yank down your bra a little, and wrap your hand in the black cloth, reaching up as far as you can while still keeping your eyes pointed down. You feel the jutting metal– still hot, but you can turn it. Breath four. Jen’s on the floor. Fuck. Jen’s on the floor, smoke’s on the bed and the ceiling and the carpet and the floor beside her, wrapping her up in a cocoon, you’re too damn slow, is she alive? Short red hair cascading in little sparks, eyes closed, you crawl to her, her freckled arm is warm but not hot, so she must be alive, she must be alive, she must be alive, breath five. You kept telling everyone you were going to start going to the gym, and you really wish you’d followed through because you do not have the superhuman strength of the gods that everyone claims to discover in their time of greatest need. You’re just on the floor, tugging at her arm, with the exact strength that you really have. Your eyes begin to burn but you can’t squint, you peel them open and lock them on her face, you have to see every single inch of her, right now. You get her head and shoulders picked up. Glance at the window. You see two person-shaped blurs outside, below, and you know it’s Avi and Mia, waving frantically at you, and your chest suddenly aches with the words you never said to everyone you’ve ever met, especially the girl in your arms. You carefully, painstakingly, drag the two of you towards the window. Grope around in your half-blindness until you find God, or maybe just a desk chair. Roll it forward, towards the window, get to your knees. Let Jen down, just for a second. Slam it through the window in a rainbow of shards, thank you cheap-ass landlord for getting the thinnest pane of glass possible. Pick Jen back up. Smile at Avi and Mia below. Tell Jen you love her. Realize you still don’t know if you’ll say it again if you make it to tomorrow. -

Avi doesn’t pause the movie this time, she just lets them keep talking, words turning to a blur of something that could be English, to look right at you, so long that you have to break the stare by the end. “Are you okay?” You say yes, fine, of course you’re okay. You just get emotional easily, you tell her. You must be one of those poor suckers from the ‘60s, because you guess you thought she was safe, too. You know we’re not supposed to care. You know we don’t learn a lot about the protagonist, about her life. Just a slice, and then blood on the shower curtain. It’s so fucking stupid to be crying. -

Sometimes you sit back and wonder what the story would be about, if she

31 ZOE WYNNS

wasn’t here. Sometimes you wonder why anyone would need to watch to the end. Sometimes you imagine a life where the fire alarm goes off, Avi’s pissed, grabs the remote, squints up at the thing ringing like it’ll point her to the culprit. “If she’s letting Adam smoke inside again, I swear to god,” she says, and you’re good at reading lips so you catch it all, but you probably wouldn’t have otherwise because this shit is loud. Someone comes thumping down the stairs, it’s Mia, she’s covering her mouth, laughing. “I am SO sorry,” she says, and there’s another set of footsteps behind her, her boyfriend, Adam, sheepishly peeking over the railing. “I opened all the windows!” he says, half-defensively, half-pathetically. One more set of footsteps, and you know it’ll be Jen, and you already smile thinking about it, how you can’t wait to look at her, to tell her that it’s okay, that nothing bad is going to happen. That nothing is burning.There’s ten minutes left in Psycho now. Avi’s getting bored, peeling a long, thin piece of her fingernail off. Old movies like to recap everything, towards the end. Make sure you walk away completely understanding how every little part of the movie works. There’s no cliff-hangers, no ambiguous endings, no slowly turning to look at each other when it’s over and saying, in unison, “What. The fuck?” No looking up an explanation video on YouTube. No debating if you saw what you think you saw. No rewinding. No need to go back. You know what happened.Jump.

32 ZOE WYNNS

33 33 QIAOAN “JOSEPH” GU

Mr. Versailles 1

Photo overlay with digital artifacts

34 QIAOAN “JOSEPH” GU 34

Mr. Versailles 2

Photo overlay with digital artifacts

Under the Skin

Gelli plate print 6x6

35 HANNAH HANKINS MARIELA SOLORZANO 35

36 BROOKE ELLIOTT MARIELA SOLORZANO 36

Starry Eyed

Gelli plate print 6x6

WE DON’T KNOW IF THERE WERE THREE WISE MEN

Maybe it was ninety degrees at night but the breeze stirred us from our air-conditioned rooms. Maybe this time we all went together, parking on the far side and traipsing through the ankle-deep grass. Probably it smelled of dirt, or dog hair; exhaust, or chlorophyll. Probably we scouted a spot sufficiently far from any people who would snitch on us for smoking (unlikely) or overhear our conversation (likely, and worse).

Perhaps we selected a trio of Adirondack chairs, not too far from the big live oak tree, but not right where the spotlights at its roots would shine into our eyes. Perhaps we unloaded our belongings, hanging purses over the backs of chairs and pulling out various implements. Perhaps one girl perched on the arm of her chair, looking in her black t-shirt and with her spindly limbs like a spider or crow. Perhaps another manspreaded unselfconsciously, leaning forward on her elbows and clasping her hands in front like she was about to make you an offer you couldn’t refuse. And perhaps another lounged with her feet slung over the armrest, brandishing the Juul she still held onto even though its glory days were long past.

It’s likely we settled in, talking about nothing and everyone, passing whatever we had, speaking, inhaling, handing to the next with the muscle memory of a ritual whose meaning we had forgotten. It’s likely we volleyed references and jokes with a fluency that approached dialect. And it’s likely we said the phrases: “Oh my God...” “Dude that was insane,” and “Take me back!!!!” in succession.

It’s likely we joked about people from our high school: who we would be in an arranged marriage with (because none of them were good choices, and this city is going to be underwater in twenty years anyway—no point building a life here). It’s likely we spat laughing at our answers: She would marry the guy no one could stand who wore a Rolex and thought he knew more about Virginia Woolf than Vita Sackville-West.

37 KATHRYN BRAGG

Certainly we took a picture, leaning into each other and smiling with no teeth, or tilting our heads ironically. Where else would we be? Where else but here?

We thought of that circle of chairs, that public park, as our personal sanctuary, our sacred place, interrupted only when someone’s unleashed dog wandered over to sniff us and poke around our scraps.

We joked at everyone’s expense—elbowing each other when the woman who had named her corgi Barbara Bush called, “BAARB, BAA-AARB,” fabricating lives for the young urban professionals whose parents were definitely paying their rent, or else they were probably into crypto or something; and playfully accepting our fair share of punch lines, too.

It’s likely, at some point, that our jokes took on a serious timbre. We still laughed, we still made light, but instead of people from our high school, we talked about God and being gay and our families and cancer and what we thought life would be like, if there would be life at all fifty years from now.

I don’t remember the first time we went to the park. I don’t remember when or how it came to be a part of our routine. But I know we were there almost every night that strange summer after senior year. I know we hugged each other, promised to keep in touch, confided our fears that things wouldn’t be the same “when we left.” If one of us got emotional, we all did. Leaving each other then seemed like the worst thing that could happen in the world.

I wonder sometimes how it is we got so close in such a short time, and I don’t really know the answer. But I do know that we did not really leave at all. On a map, our schools formed a scalene triangle with a hypotenuse a thousand miles long, but we knew everything. We talked every day. We had nothing to catch up on when we saw each other again.

We knew when her mom’s cancer returned, more serious this time. We didn’t know how quickly it would progress until the night she found out Jane was going to die, and soon. We cried on the phone in our dorms a thousand miles apart, but we did not cry when we saw each other, home for Christmas break the next week.

38 KATHRYN BRAGG

I don’t remember if we went to the park then. Somehow, I doubt it. But we were at her house that week with her cousins sleeping on the floor and her aunts in the kitchen and her father so, so thin asking us how we were doing.

We took a strange mango peel edible, but I don’t remember being high. We drank at sympathy gatherings where the hands of people scared of sadness poured her glass after glass, overflowing our cups by association. I was probably unsure what was appropriate. But her reaction was more: no one can f#cking blame me. And they couldn’t. So we followed suit.

We didn’t say “I’m sorry” because we could never be sorry enough. Or maybe I just don’t remember because of how many times I said it.

She hadn’t cried to us. She told us she was fine, she was numb, she felt like her mom would be back soon. Everyone was asking if she was okay. How could she possibly answer that?

We spent many of those days together, talking about everyone and nothing, like always. Joking with a desperation that concealed an urgent sense of need—to distract, to help her forget, but ready to turn serious and emotionally responsive at the tiniest change in her face. Sometimes she would make a joke about it. It was fine for her to joke about. But we couldn’t possibly join in.

It was sixty degrees at night in January. We sat together, in our trio of Adirondack chairs. It wasn’t new for us to ask how she was, but somehow, in our sanctuary, a wall broke down. She cried in front of us for the first time. Perhaps it was cathartic, perhaps it allowed us to share in her grief, but nothing really changed. Even if she had not shown this sadness, we had sensed it, could reach out and touch it in the air still, and it would not go away now.

But we are all still here, in our trio of chairs. Maybe forever. Where else? Where else but here?

39 KATHRYN BRAGG

40

KINGMAN

MARCELLA

Jude 35mm Film Photograph

UNREQUITED LOVE AS SPECIAL TOPICS SEMINAR

As the guest speaker, I’d like to start by introducing a pressing matter, a subtopic, Otherwise known as “Why Doesn’t She Love Me Back?”

Let’s discuss the main issue that we’re dealing with,

Namely the way that I can cycle back through an entire semester

Of little moments in which her and I appear like specks in the cosmos

Where I am orbiting round and round like a pathetic little planet,

And each of these instances have led to inevitable rejection, the probability of which We have not exactly calculated, quite yet.

And we have also not determined why she appears in every single Essay that I write,

Why she is the underlying subject of my thesis, The monster living in my subconscious,

The accidental star of my coming-of-age film.

These are all fair questions to ask.

But we need statistics.

We need to learn an entirely new type of math

In order to get precise answers.

The best we can do is wait for an apple to fall on our heads, Knocking us senseless, so we forget how badly we want this in the first place.

The best we can do is sit back and wait

For the little voice in our head to subside.

The voice which reminds us that it hurt

When she chose the boy over us.

41 NAOMI OVRUTSKY

ON BOOBS

I unbound myself with a boy in Budapest. He toyed with my chest, I’d say breasts, but between you and me, it’s a chest. Stop, these are holy jewels. He just snickered and meeked out an apology. I still sucked him off after, on my period so no fucking, but a favor he didn’t need to ask for, he pushed my head and I grinned when his sigh became a punching grunt. This is what girls want. And where do I begin? I’m happier dreaming of myself without breasts, baring a clean chest. But would I still turn heads without them? What shame is bubbling from the flatness between them, saying you’ll never succeed in hiding from yourself? I sink deeper in the tub to erase their weight, but they don’t stop floating.

42 ALICE MCCRACKEN KNIGHT

ON GLUTTONY

I love to make out with men. Feeling their mouths open against mine—tongues slipped past my parted lips.

I want to be consumed—swallowed, whole.

Andrew and Sarah, my gidu and situ, move to Utica, New York from Dekwaneh, Lebanon shortly after their arranged marriage in 1950. Andrew is twenty-two, Sarah is seventeen.

In 2013, the mayor of Dekwaneh orders Lebanese police forces to shut down and raid a queer nightclub called Ghost. Several Syrian gay men and a Lebanese transgender woman are arrested and forced by the police to undress in front of them. Photos are taken of their nude bodies.

There is no other premodern literature in which homoerotic texts are as numerous and as central as they are in classical Arabic.

Abu Nuwas, an Arab poet born in the eighth century in the Khuzestan Province of Iran, is best known for his erotic lyric poetry, often homoerotic.

As a child, I find myself entranced when my mother takes me to the gym. I stare at the men walking around on the floor, clutching water bottles in their massive fists. I imagine them clutching me in the same way. I love the men’s locker room and come up with excuses to go in there as often as possible. I try to sneak peeks at exposed cocks as I make my way to the showers.

Abu Nuwas - In the Bath-House: In the bath-house, the mysteries hidden by trousers Are revealed to you.

All becomes radiantly manifest. Feast your eyes without restraint!

My experience with adolescence is marked by lost time. Seconds, minutes, hours lost. Phased through.

A blink of my eye, a click of a pen. Gone.

43 PATRICK HUNTER

PATRICK HUNTER

My cousin and I sit on her unmade bed, feet pressed into her shag carpet. A large sheet pan of brownies connects our laps and we have placed a kitchen trash can on the floor in front of us.

We each take turns cutting ourselves a brownie, biting it, and spitting it into the trash.

My mother, prior to meeting my stepfather, has a series of boyfriends—all white, all older, all ex-military. One such boyfriend, a tall, gravelly-looking man with wide-set eyes and a permanent five o’clock shadow, is named Bob.

At seven, I watch television, a bag of Doritos resting in between my thighs. A fine layer of nacho cheese dust coats my lips. Bob walks past the living room, looks at me, and says, “Disgusting.”

There is no universally accepted word for “gay” in the Arabic language. Words that have been used in the past include sadj, meaning “peculiar,” and luti, meaning “sodomite.” The most common word used to mean gay in a modern context is mithli, meaning “homo.”

I spend the summer after my freshman year of high school in Peru doing missionary work.

Fueled by a burst of competitive energy, I pass out the most free bible tracts on an outing to the streets of Lima. My uncle tells me that my passion for Jesus reminds him of a younger version of himself.

I hope that this will convince a college aged missionary boy that I have a crush on to finally kiss me.

I am told by a cousin that my gidu had a series of male lovers before his death. All young, probably teenagers. Possibly underage.

I send a text- I’m here.

A man forty years my senior opens the door in front of me. He’s short, probably 5’4 or 5’5, with a bald head and broad shoulders. He’s not wearing a shirt.

He leads me to his room before getting me naked and laying me down on his bed. His bed frame is constructed entirely from loose cinder blocks.

He tells me to hold my arms above my head. He licks his lips before feasting on my armpits.

44

At thirteen, I spend every night praying that Jesus will forgive me for my lust before masturbating furiously to a picture of his shirtless body hanging from a cross.

When I think of my situ, I think of her fridge.

I think of telling her that I’m hungry—her holding my hand as she leads me towards it. I think of her taking out containers of kibbeh, tabouleh, warak enab. I think of her making me a plate, placing a paper towel over it, and heating it up in the microwave. She kisses my forehead before she hands it to me.

Following the death of his father, at the age of ten, Abu Nuwas moved to the town of Basra in southern Iran. In Basra, Nuwas’s boyish good looks, charisma, and ability to recite the Qur’an from memory caught the attention of Kufan poet, Waliba, who took him on as an apprentice.

It is rumored that Waliba had a sexual relationship with Nuwas. Following his apprenticeship with Waliba, Nuwas was also known to have sex with adolescent boys.

In the summer after I turn eighteen, I regularly have sex with a man named Jason who is a few years older than my father. One time, while laying naked in his bed with my arms wrapped around him, he shows me pictures of his children. They’re young—four or five—with heads full of blonde hair and wide smiles on their faces. He tells me that his son likes race cars before sticking his tongue in my ear.

Joe Orton, English author and playwright, had a predisposition for cruising, particularly in public restrooms, even more particularly with teenage boys. In 1967, Orton and his lover, Kenneth Halliwell, traveled to Tangiers, Morocco where they had easy access to young male prostitutes. By that time, homosexuality had been decriminalized in Morocco, Orton’s comments on it including, “It’s only legal over twenty-one… I like boys of fifteen.”

In August, Halliwell bludgeoned Orton to death with a hammer.

From the entry for Ghumaliyya in the Homosexual Encyclopedia: This rare Arabic term alludes to a girl whose appearance is as boyish as possible, and who therefore possesses a kind of boyish sensuality.

These girls were adept in two varieties of sexual intercourse, and therefore potentially attractive to both men who loved girls and those who loved boys.

45 PATRICK HUNTER

Abu Nuwas is predicted to have died between 814 and 816. There are four commonly circulated versions of his death. Two of these include Nuwas being framed and murdered for a transgressive poem. One includes him drinking himself to death. One includes him dying in prison.

Andrew dies peacefully in his home at the age of 89 surrounded by family, one year after the passing of his wife. In his last moments, he prays for his children and asks God to guide them. He then recites the Lord’s prayer and says that, if it is his time to go, he is ready to hold his wife’s hand again.

The Last Poem of Abu Nuwas:

O Allah, if my sins become abundant

Then indeed I know Your Forgiveness is greater than my sins

And I supplicated in humility

And if You turn my hands away

Then who will be merciful to me?

Every time I walk past a bush, I tear off a leaf. Sometimes I feel bad about this— imagining the bush yelping in pain, like I’m tearing off one of its fingers. I enjoy ripping the leaf apart at the spine, bending it in half and feeling it snap.

46 PATRICK HUNTER

47 JESSE PATETE

CMY Collab Printmaking-Multiblock - 8x10 in

TOP DOWN PROCESSING

white tee, ruddy face, worn jeans, poverty, overweight, trailer, garbage-dump porch, Gestalt: “fill in the gaps” his whisper hangs in the air, wrecked lawn beer cans, …use disorder? dirt road, rural,

What do you see?

A life in shambles

Unspoken blame lingers close behind, but wait—

Caption: Coalwood, WV. Trailer Provided Free of Charge Post-Flood. Revelation.

48 SOPHIA VONA

CHICKEN AND DUMPLINGS

I was going to kill him.

I didn’t care if he was my younger brother and I was supposed to be watching over him—I was going to kill him. I had been hulling Dixie Lee Peas on the front porch when he skipped up the stairs, his grubby fingers clutched around my poor chicken’s neck. John Alcy thought it was funny how the chicken’s head lulled from side to side. He thought the little bones in Charlie’s throat made a funny sound when they snapped.

But that was my chicken. My beautiful, little chicken. I had gotten him the summer before and went through Heaven and Hell to save him from the slaughter. I had promised Granny an extra hour of hulling and shucking every day if she let me keep him. I even told her that I wouldn’t complain about having to watch John Alcy anymore and would go to bed exactly when she told me to.

So when I realized what John Alcy had done to Charlie, I shot out of the rocking chair—peas flying everywhere—and started running. I saw his blue eyes widen as I grabbed the pocketknife from my overall pocket. He dropped Charlie onto the porch and ran, too. I chased him around the house and through the barn, over the electric fence and into the fields.

“I didn’t mean to!” He yelped as he hopped onto and then off of a hay bale.

I didn’t care what he meant to do. He had killed my chicken.

I only stopped chasing him when Granny came out of the house, wooden spoon in hand, and asked what the ruckus was all about.

Tears in my eyes, I pointed to Charlie’s mutilated body. His head was twisted at an unholy angle and a few feathers framed his head like a halo. We both got into trouble when John Alcy followed that by telling her I had chased him around with a knife. I thought it had been a fair reaction, but Granny disagreed.

“You’re both going to help me cook him,” she said, stomping back into the house.

I trudged along behind her, cradling Charlie’s body in my trembling arms. I ran a finger along his beak before handing him over. When Granny plucked fistfulls of his feathers out and cut a slit down his belly, I closed my eyes. She pulled out his organs handful by bloody handful. First, the gallbladder. Then, then intestines. And, finally, the heart. When I heard John Alcy gag, I hit him upside the head. It was his fault, anyway. He didn’t deserve to be disgusted.

49 CAROLINE PARKER

CAROLINE PARKER

Granny made me fill the biggest pot in the kitchen with water. When it reached a boil, I lowered Charlie’s body in. We let him simmer for a few hours. In the meantime, she had John Alcy and me make dumplings. The flour got all over my overalls, so I made sure to throw a little pinch at him to make up for it. Our arms were sore from kneading by the time Charlie was done cooking.

Granny took him out of the pot and added the dumplings into the leftover chicken water. She made us cut Charlie up and remove all his bones. But when she wasn’t looking, I stole his femur and slipped it into my pocket. At dinner that night, I clutched his little bone with every bite of Charlie I ate, and I ate a lot of him, all I could bear.

50

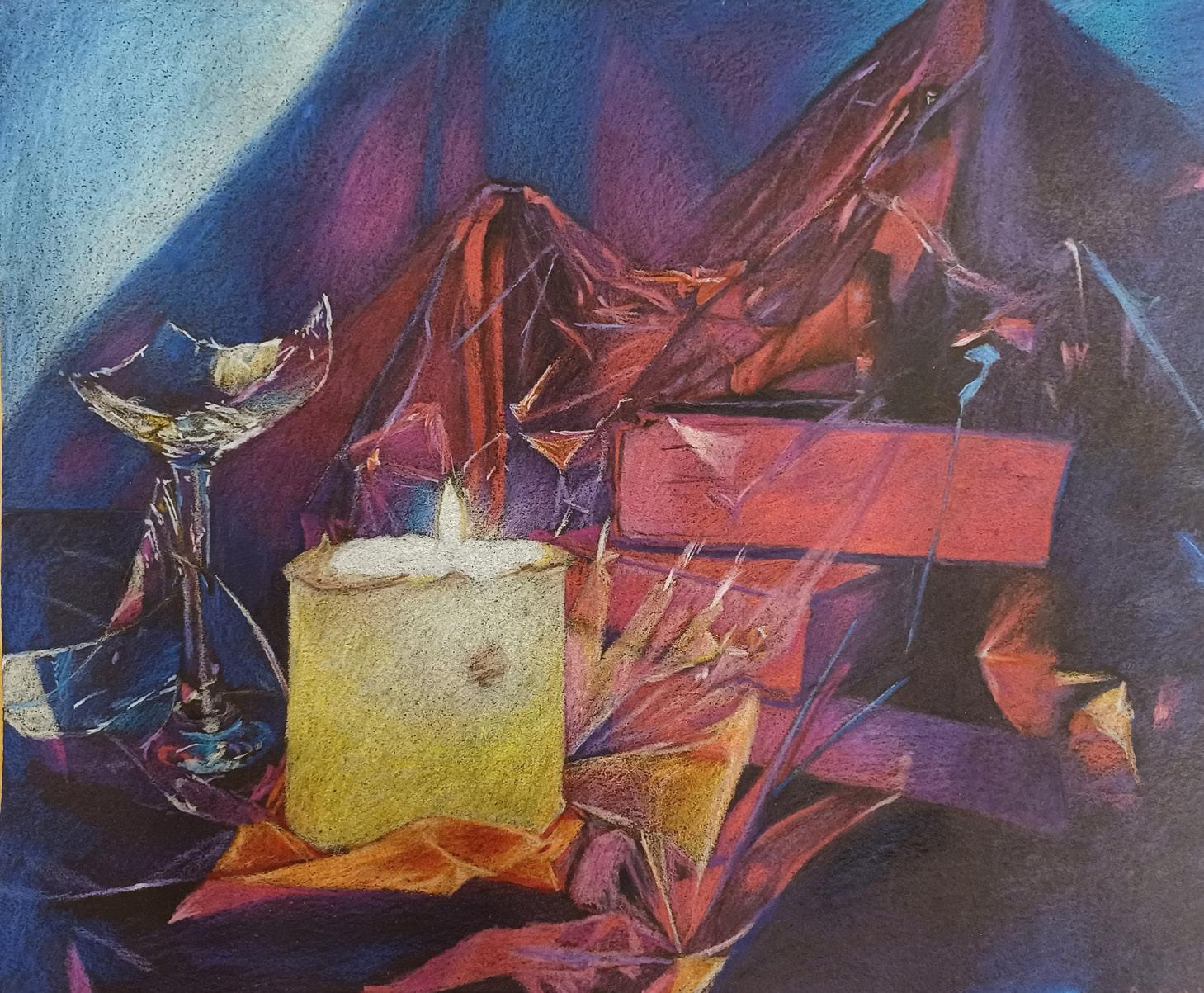

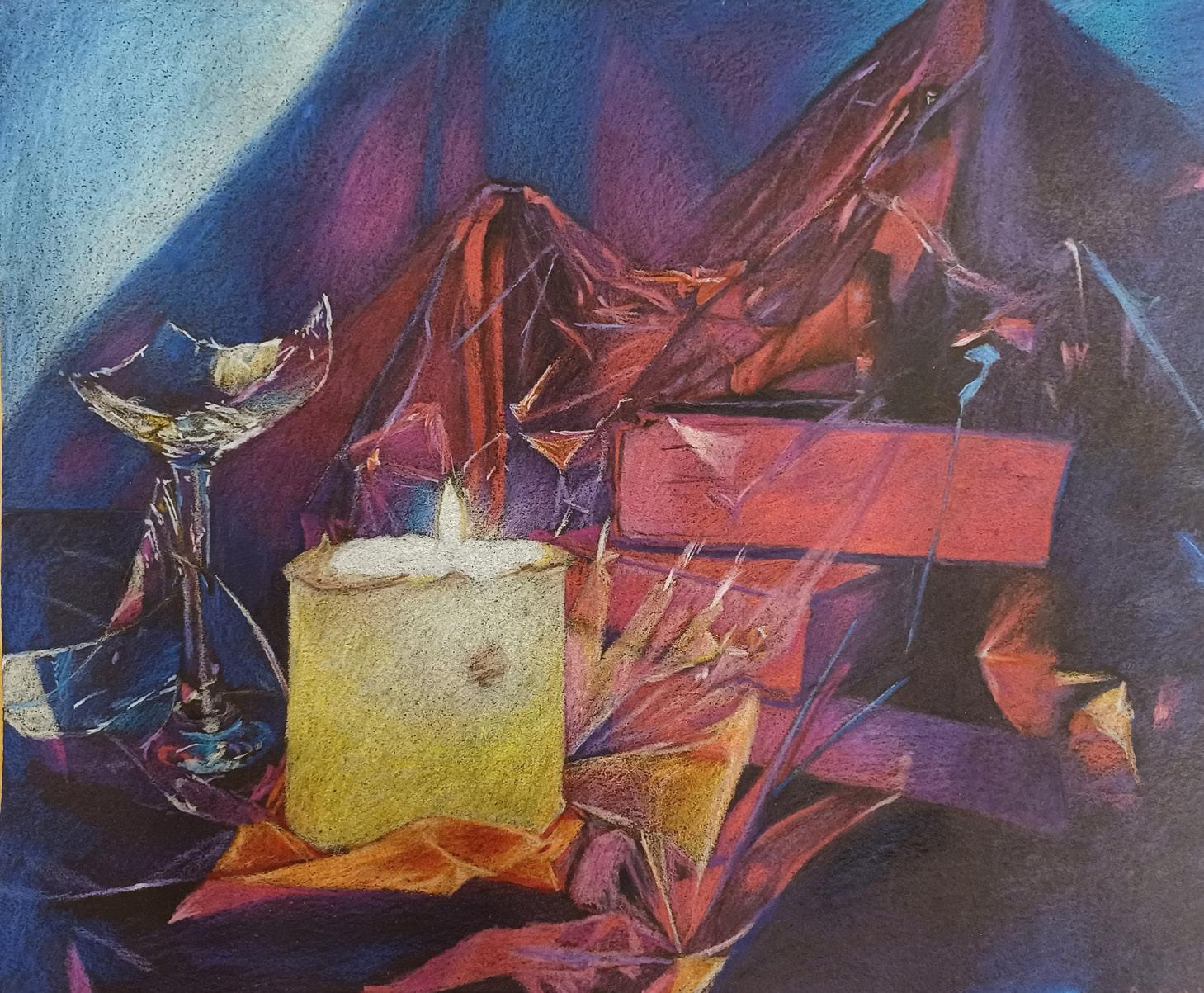

Emaciated

51 MB CONNOLLEY

Mixed media (oil pastel, digital) - 1087x1200 pixels

SPOKES

The wheel turns.

Spring yields to the gagging mist-thick Start of summer.

The world’s throat is gummed with heat In its long sleep.

I am not old—

My life spreads out ahead of me like the glass Surface of a wetland.

Not sure what I can step on Without falling through.

Sackett. Water. Quotes around important things.

Not sure how to read this

Without chewing the skin on the Back of my hand.

Something’s got to give.

She says it to me with a shrug

And puts her lips back to the straw.

And who’s going to bell the cat?

We came into a world covered in glitter. It’s in the air and in our brains

And in our blood.

No amount of leeches will pull it out.

Twitchy, scattershot. Whispering to each other

In the black, temperate underbelly

Of the world. We know

We’re being watched. Some care.

Something’s got to give.

The Cradle Will Rock. The seats

In the cinema will grow cold

While we talk.

And already while we mutter and murmur

52 BROOKE ELLIOTT

Coiling our bodies around each other in the dark Half-lidded,

The wheel is turning and

There are young ones to meet.

Feral. Blind with hunger.

Ungovernable, en caul, Wrapped in their fine mesh of battery wire.

The dog that watches us

Already worries them in its teeth.

We in the anthill can’t see what those teeth

Are doing to them. Can’t be good, but then,

Maybe the something that gives Will be them

And not us.

Whatever stands over us, Whatever owns the dog, I hope it moves out Of the way of my sunlight.

53 BROOKE ELLIOTT

Untitled

Archival Inkjet of large-format paper negatives - 11x14 inches

54 QIAOAN “JOSEPH” GU

55 MARCELLA KINGMAN

Thomas 35mm Film Photograph

10 ACRES

Any time Dad showed me the photos—the ones with the polka-dotted fawn nestled in her mother’s soft neck, or the ones with the bobcat licking her fleecy kitten clean, or the ones with the throng of ducklings trailing after their mother—I ached. Dad was obsessive with his trail cameras, crafting a robust system of surveillance that collapsed our entire 10 acres of forest into one massive eye of Dad-sight.

When Dad was home, I lingered in the back room of our cabin so he wouldn’t remember I was there, and couldn’t sit me in front of the computer and click through pictures of the doe and the bobcat and the mother duck, laughing and sighing with awe in my ear. When he was gone, then I’d flip through the photos, making my own conclusions about Dad’s creatures.

Still, I could tell he ached too. He appeared in the trail photos often, when he was out tweaking and shifting the cameras. At dusk, I would see him lying on his back on the forest floor, tears running from the sides of his eyes into the earth. It was only when he dusted his corduroy jacket off and headed back to the cabin that the deer would come out and the owls would fly low again. Humans were the loneliest beings, he’d said to me once.

And then there was one day, when the light had slipped beneath the trees and the crickets had begun to hum the rhythm of the night, and Dad was still not home. In the green, wobbly nightvision of the trail cams I could see him wandering. He probably hoped the dark would obscure his form to the animals. Maybe a blind doe would let him curl up against her neck.

In the morning, the cameras snapped him sleeping. His body was sprawled across the thick branch of an oak, limbs dangling over the sides. The light danced across his face as the trees swayed overhead. When he woke, he fell to the ground on all fours and scuttled off into the brush like an oversized crab. I shook my head and scoffed.

He stayed out there for the rest of the week, scrounging in the dirt for roots and fallen nuts and drinking the dirty, stagnant water of the duck pond. He looked unwell. I watched his skin gray and fall off in long sheaths as if he were a snake. Each morning when I turned on the computer, photos of his night activities were uploaded in great clusters. He slept in the trees, a mass of wrinkled gray flesh and bone. His clothes had been abandoned long ago and I could see the deep ridges of his spine undulating in his back as he moved.

56 SYDNEY BRAINARD

What could be done about this? I wasn’t exactly sure. Should I have corralled this pale beast back into the cabin? Hoped he would grow a warm, red layer of skin and fatten back into the man who once promised an 11-year-old me that he would try to notice when I spoke?

Maybe it was purposeful. He’d made himself very lonely in this world. If a gleaming angel floated down from above and offered to turn him into a wild creature for the rest of his days, he would have shaken the golden man’s hand without a second thought.

Night and day, I laid in front of the computer, watching the photos from the trail cams sync up and chart Dad’s path through the woods. I saw that the deer scattered in his presence, that the bobcats cowered in their dens as he passed. No one else would have him, but neither would I. The cabin’s front door was double-bolted, the back door locked and blocked off with my dresser. But the pantry was becoming hollow; I would need food in a few days.

And then just like that, Dad was gone. I watched him run like a leopard through the woods on that last day, leaping over saplings and rocks until he reached the border of our 10 acres and disappeared completely.

I waited a day just in case, and then I went down the path to the neighbor’s, printed photos of Dad in hand. Mr. and Mrs. Michaels nodded along as I spoke, agreeing it was best to shoot the creature on site. They were scared for their chickens, they said. I told them they should be more scared for their daughters.

57 SYDNEY BRAINARD

ROADSIDE PIETA

I think God was jealous of our closeness, of my bare hand prodding the hit dog, coaxing quivers of life from the blood-matted fur. Jealous of the way I made myself small to be beside the wounded, of the things I confessed with the dog’s head in my lap. God could only dream of hands so ordinary, so clumsy in their attempt to be good. He would never understand the way I pulled the dog close, or our twin desperation for comfort slicing through corpse breath and the exhaust of my still-running car.

58 BENI KROLL

AFTER THE CRASH I DREAMT YOU WERE INNOCENT

In this dream, my father is the one kneeling for once, dragging his knuckles against pavement, like the chain rattle of a prisoner. His wedding band scuffed, the struck ground spit back sparks, his grimace bore teeth like bullets, how did he shape his breath like that, gasping like a newborn’s private language? A mile back, I am swinging open the passenger door of his wrecked car. I cannot yet hear the bloodying of his knuckles, but the wind smacks sobs against my face and I am running towards an echo of cells, my mouth hung open, hooked onto a syllable until it gummies with sweat.

59 BENI KROLL

CONTRIBUTORS

Timothy Anderson is a North Carolina-based conceptual artist primarily working in video, photography, and sculpture. His work explores screens, image circulation, and digital culture.

Kathryn Bragg is a normalgirl from Houston, Texas. She likes trees, facts, and grilled cheeses and has been occasionally (increasingly) writing about the things that live in her head.

Sydney Brainard is junior at UNC, studying journalism and creative writing. She spends her time refining her Mario-Kart skills and reading Joan Didion.

Alexis Clifton is a Native American writer currently living in NC. She enjoys writing of the mundane, the extraordinary, and all that lies between. She is heavily inspired by contemporary works and ideas of nature, culture, and philosophy.

MB Connolley is a sophomore studying art history and film studies. Outside of art, they enjoy participating in student theatre (backstage of course) and watching horror movies.

Brooke Elliott is a journalism and data science student with a passion for short fiction, cinema, comedy, and her cat. She can often be found writing or reading at Epilogue, her favorite coffee shop on Franklin Street. Say her name five times in front of a mirror for a fun surprise.

Qiaoan “Joseph” Gu 顾荞安 is an artist based in Chapel Hill, N.C., USA and his hometown Jiangyin, Jiangsu, P.R.C. He usually works with analog/digital and printmaking. Intersectionality and alternatives could be used to describe his practice.

Patrick Hunter is a creative writing student. He is very scared of horses!

Emerald Izuakor is a junior studying nutrition (health and society) and Hispanic linguistics. An aspiring academic, she loves to explore new ideas, places, and books; (reading them all is another thing!) learn languages; and frequent gardens. Currently, Emerald is interested in travel and food writing and draws inspiration from all the happenings around her.

Marcella Kingman is a senior from Cary, North Carolina. She is majoring in neuroscience and minoring in studio art and chemistry. She loves photography for its ability to capture the people she loves.

Beni Kroll is a senior English major at UNC, minoring in Chinese. He loves to learn languages and write all sorts of silly little poems.

Rachel Landi is a largely self-taught artist. She specializes in portraits, both human and animal. A lover of all types of art, she is also a percussionist in the University Wind Ensemble.

Alice McCracken Knight is a senior studying dramatic art and creative writing. They are from Boone, NC. Alice loves opossums, stepping on the crunchiest leaf, and picking up their friends when they hug.

Kieran Murphy is a current senior, poet, actor and video game environment artist from Mebane, North Carolina. Much of his writing explores the little things people leave behind and construct themselves out of, and how weird it is to exist.

Naomi Ovrutsky is a senior astrophysics major and creative writing minor from Charlotte, NC. She loves haunted house stories, the garden section of Lowe’s, and buying a six dollar latte anytime there’s a minor inconvenience. Her poems have appeared in Peregrine Magazine and Idiosyncrazy.

Caroline Parker is a sophomore studying English, American studies, and creative writing. When she’s not writing, she can be found hanging out with her cow, Noel, or sorting through her ever-growing bookshelves.

Jesse Patete is an up and coming printmaker from Asheville, NC who enjoys many media and a special interest in natural form. He is a freshman at UNC-Chapel Hill and hopes to one day be an art teacher.

Luisa Peñaflor is a junior at UNC. She has a cat named Eggs.

Jane Pierce is a journalism major and studio art minor at UNC. She mostly works with printmaking, specifically drypoint and linocut, and believes visual art is crucial in journalistic story telling. Her work is process focused: taking time to understand how the process, rather than the final product, best serves her.

Mariela Solorzano is a chemistry BA student with a double minor in neuroscience and studio art planning to graduate in December 2023. She was born and raised in Miami, FL and is of Nicaraguan and Cuban descent. She is a self-motivated artist in pursuit of furthering her artistic technique and mastering multiple types of media.

Sophia Vona is a sophomore who hopes to combine her interests in science and the health humanities, and apply them to a career in healthcare. On the side, she likes to write silly little poems such as these.

Campbell Warren devotes her studies at UNC-CH to comparative literature and Italian. After graduation, she hopes to move abroad to write poetry and prose, and teach it.

Calli Westra is a documentary photographer from Morganton, NC. Much of her work features her close friends and family, covering topics related to girlhood, youth, and femininity.

Zoe Wynns is a writer of fiction and poetry from Cary, North Carolina. She has selfpublished eight novels and appeared as a writer in the Short Story machines at UNC. She’s interested in exploring the space between genres to create plot-driven, emotional narratives.

INFORMATION

SUBMISSIONS

Guidelines for submission can be found online at www.unccellardoor.com. Please note that staff members are not permitted to submit to any section of Cellar Door while they work for the magazine.

All undergraduate students may apply to join the staff of Cellar Door. Any openings for positions on the poetry, fiction, nonfiction, or art selection staffs will be advertised online.

SUPPORTING CELLAR DOOR

Your gift will contribute to publicity, production, and staff development costs not covered by our regular funding. Contributors will receive copies of the magazine through the mail for at least one year.

Please make all checks payable to “Cellar Door” and be sure to include your preferred mailing address.

Cellar Door

c/o Melissa Faliveno and Michael McFee Department of English UNC-CH Greenlaw Hall, CB 3520 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3520